Submitted:

05 August 2025

Posted:

05 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- (1)

- Examine the methods and models used to generate synthetic data in healthcare contexts.

- (2)

- Explore the range of applications across domains such as medical imaging, clinical records, and research simulation.

- (3)

- Identify key limitations, ethical concerns, and risks including privacy, bias, and validation challenges.

- (4)

- Assess the broader implications of synthetic data for the future development and deployment of AI in healthcare.

Methods

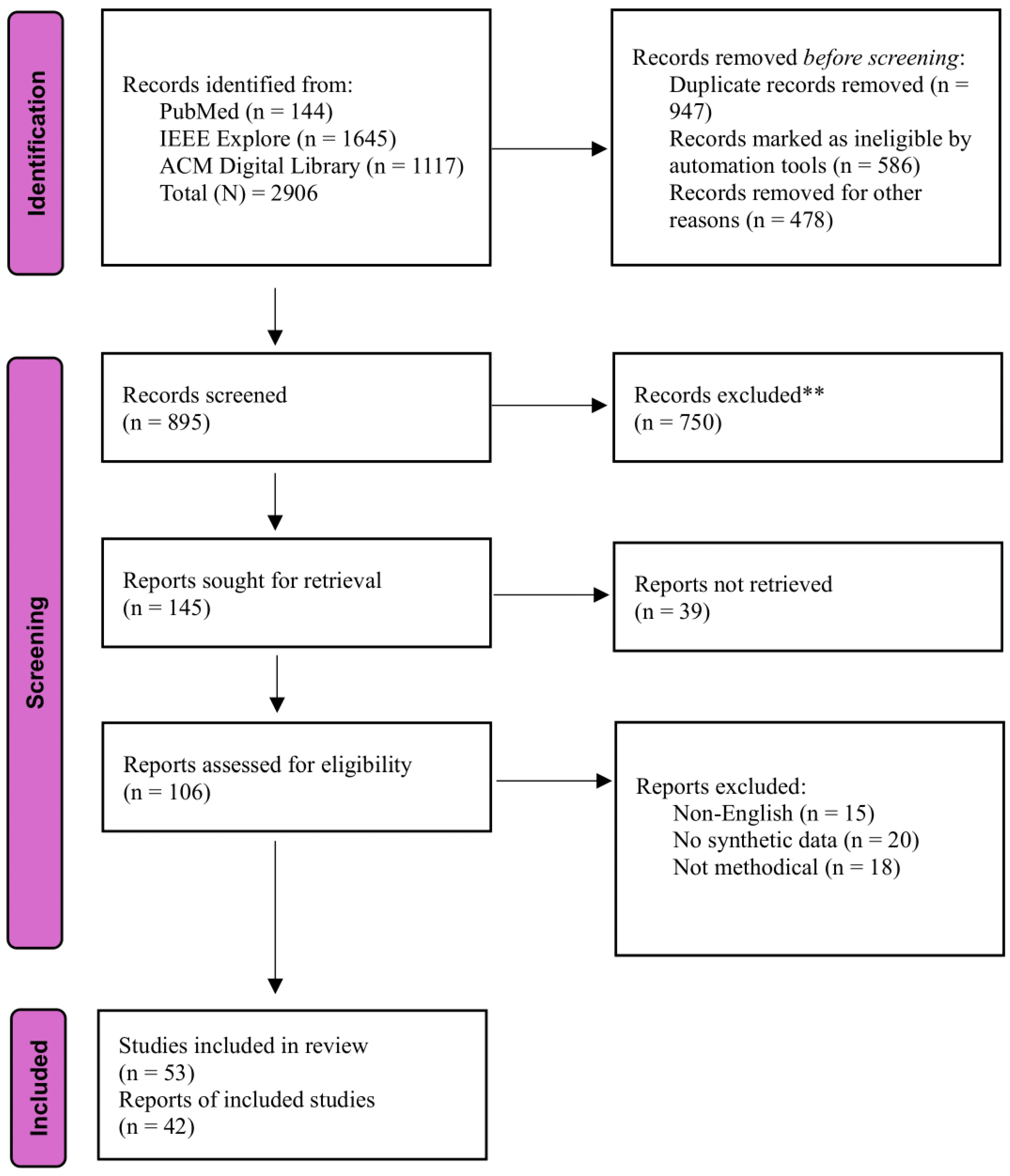

Search Strategy

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Study Selection Process

Data Extraction

Synthesis of Results

Results

Characteristics of Included Studies

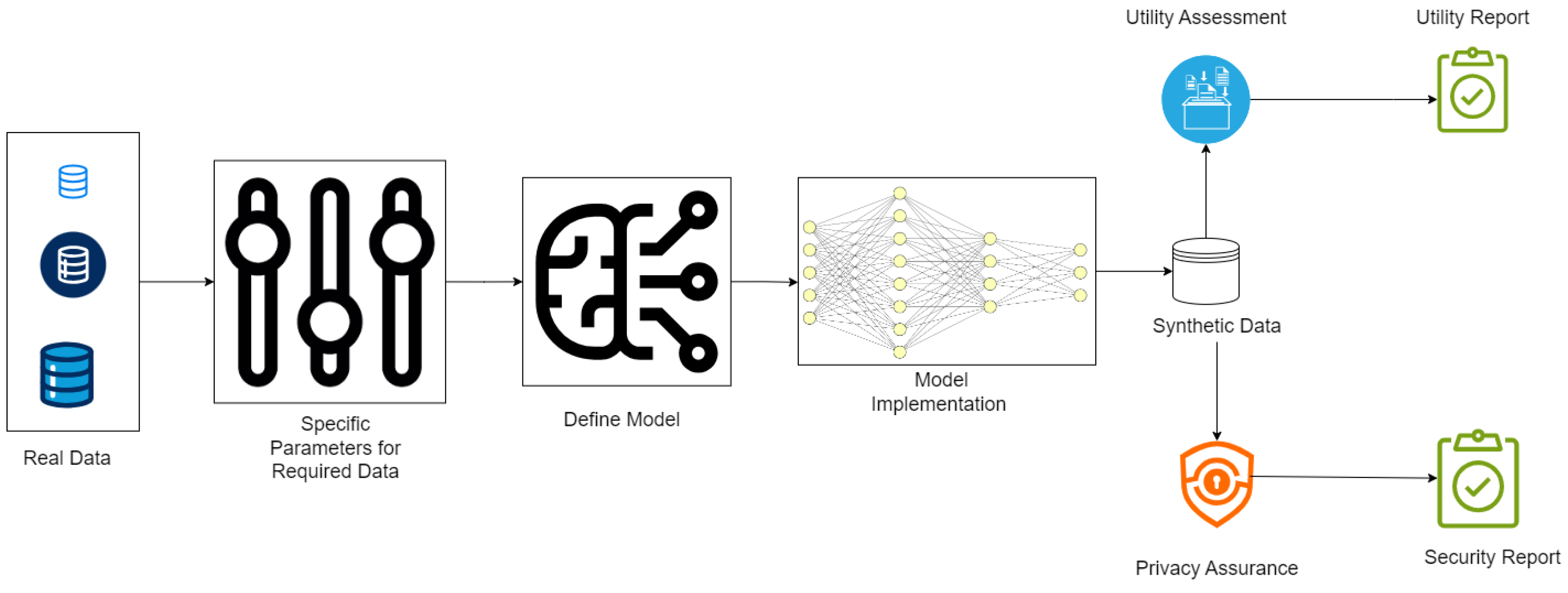

How Do Synthetic Data Generation in Healthcare Works?

- Fidelity: How well the synthetic data matches the statistical properties of real data.[35]

- Utility: Whether the data performs effectively in tasks like training machine learning models.[36]

- Privacy: Confirmation that no sensitive information from the original dataset can be inferred, often tested using privacy-preserving techniques like differential privacy.[30]

Current Synthetic Healthcare Data Generation Techniques

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs)

Differential Privacy-Based Methods

Graph-Based Synthetic Data Generation: GraphGAN and NetGAN

Multimodal Synthetic Data Generation

Bayesian Networks for Synthetic Data Generation

Diffusion Models for Synthetic Data Generation

Federated Learning for Synthetic Data Generation

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)

Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique (SMOTE)

Agent-Based Modeling (ABM)

Large Language Models for Synthetic Text Generation

Current Applications for Synthetic Data

AI Training and Model Development

Privacy-Preserving Data Sharing

Bias Mitigation

Education and Training

Operational Optimization

Challenges and Potential Risks

No Established Data Standards

Realism vs. Privacy Trade-Off

Bias Amplification

Computational Complexity

Overconfidence in Data Utility

Security Vulnerabilities

Ethical Concerns

Heterogeneity Problems and Lack of Clinical Quality

The Future of Healthcare AI and the Impact of Synthetic Data

Risk of Model Overfitting to Synthetic Patterns

Amplification of Bias and Inequity

Erosion of Trust in AI Systems

Challenges in Validation and Benchmarking

Ethical Concerns About Data Ownership and Consent

Security Risks and Privacy Paradox

Overreliance and Misplaced Confidence

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Use of AI

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giuffrè, M.; Shung, D.L. Harnessing the power of synthetic data in healthcare: innovation, application, and privacy. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, A.; Wang, Z.; Rotalinti, Y.; Myles, P. Generating high-fidelity synthetic patient data for assessing machine learning healthcare software. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rujas, M.; Herranz, R.M.G. del M.; Fico, G., Ed.; Merino-Barbancho, B. Synthetic Data Generation in Healthcare: A Scoping Review of reviews on domains, motivations, and future applications 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner Identifies Top Trends Shaping the Future of Data Science and Machine Learning Available online:. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2023-08-01-gartner-identifies-top-trends-shaping-future-of-data-science-and-machine-learning (accessed on Jan 2, 2025).

- Fortune Business Synthetic Data Generation Market | Forecast Analysis [2030] Available online:. Available online: https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/synthetic-data-generation-market-108433 (accessed on Jan 2, 2025).

- Madden, B. Synthetic Data in Healthcare: the Great Data Unlock Available online:. Available online: https://hospitalogy.com/articles/2023-11-02/synthetic-data-in-healthcare-great-data-unlock/ (accessed on Jan 2, 2025).

- Little, C.; Elliot, M.; Allmendinger, R. Federated learning for generating synthetic data: a scoping review. Int J Popul Data Sci 2023, 8, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Callender, T.; Cebere, B.; Janes, S.M.; Navani, N.; van der Schaar, M. Synthetic data for privacy-preserving clinical risk prediction. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 25676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanley, D.; Hogenboom, J.; Lysen, F.; Wee, L.; Lobo Gomes, A.; Dekker, A.; Meacham, D. Getting real about synthetic data ethics. EMBO Rep 2024, 25, 2152–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales, A.; Guruswamy, G.; Smith, S.R. Synthetic data in health care: A narrative review. PLOS Digit Health 2023, 2, e0000082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amico, S.; Dall’Olio, D.; Sala, C.; Dall’Olio, L.; Sauta, E.; Zampini, M.; Asti, G.; Lanino, L.; Maggioni, G.; Campagna, A.; et al. Synthetic Data Generation by Artificial Intelligence to Accelerate Research and Precision Medicine in Hematology. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 2023, 7, e2300021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, M.H.; Sengur, A.; Salvi, M.; Seoni, S.; Faust, O.; Mir, H.; Molinari, F.; Acharya, U.R. Synthetic Data Generation via Generative Adversarial Networks in Healthcare: A Systematic Review of Image- and Signal-Based Studies. IEEE Open Journal of Engineering in Medicine and Biology 2025, 6, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravinth, S.S.; Srithar, S.; Joseph, K.P.; Gopala Anil Varma, U.; Kiran, G.M.; Jonna, V. Comparative Analysis of Generative AI Techniques for Addressing the Tabular Data Generation Problem in Medical Records. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Recent Advances in Science and Engineering Technology (ICRASET); 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, A.; Li, J.; Pomykala, K.L.; Kleesiek, J.; Alves, V.; Egger, J. GAN-based generation of realistic 3D volumetric data: A systematic review and taxonomy. Med Image Anal 2024, 93, 103100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidian, S.; Wang, F.; Moffitt, R.; Garcia, V.; Dutt, A.; Chang, W.; Pandya, V.; Hajagos, J.; Saltz, M.; Saltz, J. SMOOTH-GAN: Towards Sharp and Smooth Synthetic EHR Data Generation. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence in Medicine: 18th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, AIME 2020, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2020, Proceedings, August 25–28; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2020; pp. 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolentzos, G.; Vazirgiannis, M.; Xypolopoulos, C.; Lingman, M.; Brandt, E.G. Synthetic electronic health records generated with variational graph autoencoders. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, R.; Aguilar, J. A synthetic data generation system based on the variational-autoencoder technique and the linked data paradigm | Progress in Artificial Intelligence Available online:. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13748-024-00328-x (accessed on Jan 2, 2025).

- Lenatti, M.; Paglialonga, A.; Orani, V.; Ferretti, M.; Mongelli, M. Characterization of Synthetic Health Data Using Rule-Based Artificial Intelligence Models. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 2023, 27, 3760–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Arora, A. Generative adversarial networks and synthetic patient data: current challenges and future perspectives. Future Healthc J 2022, 9, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, L.; El Emam, K.; Ding, L.; Sharma, V.; Zhang, X.H.; Kababji, S.E.; Carvalho, C.; Hamilton, B.; Palfrey, D.; Kong, L.; et al. A method for generating synthetic longitudinal health data. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2023, 23, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wang, F.; Rashidian, S.; Kurc, T.; Abell-Hart, K.; Hajagos, J.; Zhu, W.; Saltz, M.; Saltz, J. Generating Longitudinal Synthetic EHR Data with Recurrent Autoencoders and Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the Heterogeneous Data Management, Polystores, Poly 2021 and DMAH 2021, Virtual Event, August 20, 2021, Revised Selected Papers, and Analytics for Healthcare: VLDB Workshops; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2021; pp. 153–165. [Google Scholar]

- Kosolwattana, T.; Liu, C.; Hu, R.; Han, S.; Chen, H.; Lin, Y. A self-inspected adaptive SMOTE algorithm (SASMOTE) for highly imbalanced data classification in healthcare. BioData Mining 2023, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaie, M.A.; Füssenich, K.; Ameling, C.; Boshuizen, H.C. Constructing synthetic populations in the age of big data. Population Health Metrics 2023, 21, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumichev, G.; Blinov, P.; Kuzkina, Y.; Goncharov, V.; Zubkova, G.; Zenovkin, N.; Goncharov, A.; Savchenko, A. MedSyn: LLM-Based Synthetic Medical Text Generation Framework. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases. Applied Data Science Track; Bifet, A., Krilavičius, T., Miliou, I., Nowaczyk, S., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 215–230. [Google Scholar]

- Miletic, M.; Sariyar, M. Large Language Models for Synthetic Tabular Health Data: A Benchmark Study. In Digital Health and Informatics Innovations for Sustainable Health Care Systems; IOS Press, 2024; pp. 963–967.

- Juwara, L.; El-Hussuna, A.; El Emam, K. An evaluation of synthetic data augmentation for mitigating covariate bias in health data. Patterns 2024, 5, 100946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomotey, R.K.; Kumi, S.; Ray, M.; Deters, R. Synthetic Data Digital Twins and Data Trusts Control for Privacy in Health Data Sharing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Workshop on Secure and Trustworthy Cyber-Physical Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Osorio-Marulanda, P.A.; Epelde, G.; Hernandez, M.; Isasa, I.; Reyes, N.M.; Iraola, A.B. Privacy Mechanisms and Evaluation Metrics for Synthetic Data Generation: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 88048–88074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, K.I.-H.; Perez-Concha, O.; Hanly, M.; Mnatzaganian, E.; Hao, B.; Sipio, M.D.; Yu, G.; Vanjara, J.; Valerie, I.C.; Costa, J. de O.; et al. Enriching Data Science and Health Care Education: Application and Impact of Synthetic Data Sets Through the Health Gym Project. JMIR Medical Education 2024, 10, e51388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.J.; Naresh, R.; Jarial, R.K.; Malik, H. Optimized Synthetic Data Integration with Transformer’s DGA Data for Improved ML-based Fault Identification. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2024, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgon, A.; Zhang, Y.; Petrick, N.; Sahiner, B.; Cha, K.H.; Samala, R.K. Bias amplification to facilitate the systematic evaluation of bias mitigation methods. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koetzier, L.R.; Wu, J.; Mastrodicasa, D.; Lutz, A.; Chung, M.; Koszek, W.A.; Pratap, J.; Chaudhari, A.S.; Rajpurkar, P.; Lungren, M.P.; et al. Generating Synthetic Data for Medical Imaging. Radiology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M.; Epelde, G.; Alberdi, A.; Cilla, R.; Rankin, D. Synthetic data generation for tabular health records: A systematic review. Neurocomputing 2022, 493, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.J.; Lu, M.Y.; Chen, T.Y.; Williamson, D.F.K.; Mahmood, F. Synthetic data in machine learning for medicine and healthcare. Nat Biomed Eng 2021, 5, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Mahmoud, Q.H. A Systematic Review of Synthetic Data Generation Techniques Using Generative AI. Electronics 2024, 13, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, A.; Wang, Z.; Rotalinti, Y.; Myles, P. Generating high-fidelity synthetic patient data for assessing machine learning healthcare software. NPJ Digit Med 2020, 3, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hairani, H.; Widiyaningtyas, T.; Prasetya, D.D. Addressing Class Imbalance of Health Data: A Systematic Literature Review on Modified Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) Strategies. JOIV : International Journal on Informatics Visualization 2024, 8, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigi, F.; Rashidi, T.H.; Viti, F. Synthetic Population: A Reliable Framework for Analysis for Agent-Based Modeling in Mobility. Transportation Research Record 2024, 03611981241239656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhao, L. A Systematic Survey on Deep Generative Models for Graph Generation. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 2023, 45, 5370–5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannucci, S.; Kholidy, H.A.; Ghimire, A.D.; Jia, R.; Abdelwahed, S.; Banicescu, I. A Comparison of Graph-Based Synthetic Data Generators for Benchmarking Next-Generation Intrusion Detection Systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Cluster Computing (CLUSTER); 2017; pp. 278–289. [Google Scholar]

- Haleem, M.S.; Ekuban, A.; Antonini, A.; Pagliara, S.; Pecchia, L.; Allocca, C. Deep-Learning-Driven Techniques for Real-Time Multimodal Health and Physical Data Synthesis. Electronics 2023, 12, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowski, M.; Wróblewska, A.; Sysko-Romańczuk, S. Effective Techniques for Multimodal Data Fusion: A Comparative Analysis. Sensors 2023, 23, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoshin, G.; Branciamore, S.; Rodin, A.S. Synthetic data generation with probabilistic Bayesian Networks. Math Biosci Eng 2021, 18, 8603–8621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, D.; Sobiesk, M.; Patil, S.; Liu, J.; Bhagat, P.; Gupta, A.; Markuzon, N. Application of Bayesian networks to generate synthetic health data. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020, 28, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, A.; Serag, A. Self-Supervised Learning Powered by Synthetic Data From Diffusion Models: Application to X-Ray Images. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 59074–59084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, A.A.; Walker, B.; Landon, C.; Ambrosy, A.; Fudim, M.; Wysham, N.; Toro, B.; Swaminathan, S.; Lyons, T. ScoEHR: Generating Synthetic Electronic Health Records using Continuous-time Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 8th Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference.

- Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, F.; Xie, X.; Guo, M. GraphGAN: Graph Representation Learning With Generative Adversarial Nets. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2018, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generating Longitudinal Synthetic EHR Data with Recurrent Autoencoders and Generative Adversarial Networks | Heterogeneous Data Management, Polystores, and Analytics for Healthcare Available online:. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1007/978-3-030-93663-1_12 (accessed on Dec 28, 2024).

- Hussain, L.; Lone, K.J.; Awan, I.A.; Abbasi, A.A.; Pirzada, J.-R. Detecting congestive heart failure by extracting multimodal features with synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) for imbalanced data using robust machine learning techniques. Waves in Random and Complex Media 2022, 32, 1079–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emdad, F.B.; Ravuri, B.; Ayinde, L.; Rahman, M.I. “ChatGPT, a Friend or Foe for Education? In ” Analyzing the User’s Perspectives on The Latest AI Chatbot Via Reddit. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Interdisciplinary Approaches in Technology and Management for Social Innovation (IATMSI); 2024; Vol. 2; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Shahul Hameed, M.A.; Qureshi, A.M.; Kaushik, A. Bias Mitigation via Synthetic Data Generation: A Review. Electronics 2024, 13, 3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, L.K. Ethically Challenged: Private Equity Storms US Health Care; JHU Press, 2022; ISBN 978-1-4214-4286-0.

- Aysha, A. Evaluate synthetic data quality using downstream ML - MOSTLY AI 2023.

- Zewe, A. In machine learning, synthetic data can offer real performance improvements Available online:. Available online: https://news.mit.edu/2022/synthetic-data-ai-improvements-1103 (accessed on Feb 27, 2025).

- Draghi, B.; Wang, Z.; Myles, P.; Tucker, A. Identifying and handling data bias within primary healthcare data using synthetic data generators. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M.; Kaufman, B.G.; Pink, G.H. Average Beneficiary CMS Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) Risk Scores for Rural and Urban Providers; Cecil G. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pachouly, J.; Ahirrao, S.; Kotecha, K.; Selvachandran, G.; Abraham, A. A systematic literature review on software defect prediction using artificial intelligence: Datasets, Data Validation Methods, Approaches, and Tools. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2022, 111, 104773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M. Synthetic data is the future of Artificial Intelligence. Medium 2023.

- Shanley, D.; Hogenboom, J.; Lysen, F.; Wee, L.; Lobo Gomes, A.; Dekker, A.; Meacham, D. Getting real about synthetic data ethics. EMBO Rep 2024, 25, 2152–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocoń, J.; Cichecki, I.; Kaszyca, O.; Kochanek, M.; Szydło, D.; Baran, J.; Bielaniewicz, J.; Gruza, M.; Janz, A.; Kanclerz, K.; et al. ChatGPT: Jack of all trades, master of none. Information Fusion 2023, 99, 101861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushotham, S.; Meng, C.; Che, Z.; Liu, Y. Benchmarking deep learning models on large healthcare datasets. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2018, 83, 112–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Sendino, R.; Serrano, E.; Bajo, J. Mitigating bias in artificial intelligence: Fair data generation via causal models for transparent and explainable decision-making. Future Generation Computer Systems 2024, 155, 384–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji, I.D.; Smart, A.; White, R.N.; Mitchell, M.; Gebru, T.; Hutchinson, B.; Smith-Loud, J.; Theron, D.; Barnes, P. Closing the AI accountability gap: defining an end-to-end framework for internal algorithmic auditing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Holzinger, A.; Biemann, C.; Pattichis, C.S.; Kell, D.B. What do we need to build explainable AI systems for the medical domain? 2017. [CrossRef]

- GDPR What is GDPR, the EU’s new data protection law? eu 2018.

| No formal critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence was conducted, as the aim of this scoping review was to map the breadth and nature of existing research rather than to assess the methodological quality or risk of bias. This approach is consistent with the objectives and methodological guidance for scoping reviews, which prioritize comprehensive coverage over detailed quality evaluation. Study | Methodology | Application Focus | Challenges Identified | Implications |

| D'Amico et al. (2023)[13] | AI-based synthetic data generation | Precision medicine in hematology | Validation of synthetic data and integration with real datasets | Accelerates research and improves personalized treatment strategies |

| Akpinar et al. (2024)[14] | Systematic review of GAN-based techniques | Healthcare image and signal data generation | GAN stability and performance evaluation | Provides insights into potential applications and gaps in healthcare data synthesis |

| Aravinth et al. (2023)[15] | Comparative analysis of generative AI techniques | Tabular medical record data generation | Scalability and preservation of data utility | Facilitates better understanding of data generation approaches for EHRs |

| Ferreira et al. (2024)[16] | GAN-based systematic review | 3D volumetric data generation | Computational complexity and realism of generated data | Advances 3D data synthesis for medical imaging and diagnostics |

| Rashidian et al. (2020)[17] | SMOOTH-GAN architecture | Synthetic EHR data generation | Maintaining longitudinal consistency in synthetic data | Improves quality and usability of synthetic EHR datasets for research |

| Nikolentzos et al. (2023)[18] | Variational graph autoencoders | Synthetic electronic health records | Complexity in representing relational structures | Enhances data synthesis with relational and temporal context |

| Dos Santos et al. (2024)[19] | VAE and linked data paradigm | Synthetic data generation for medical research | Integration with linked datasets and scalability | Promotes interoperability and broader applications in health research |

| Lenatti et al. (2023)[20] | Rule-based AI models | Characterization of synthetic health data | Incorporating domain-specific rules effectively | Improves reliability and acceptance of synthetic datasets |

| Arora & Arora (2022)[21] | Generative adversarial networks (GANs) | Synthetic patient data generation | Ethical concerns and biases in GAN outputs | Guides to the ethical development of AI in healthcare |

| Little et al. (2023)[7] | Federated learning | Synthetic data generation for privacy-preservation | Balancing privacy and data utility | Enhance secure data sharing and collaborative research |

| Mosquera et al. (2023)[22] | Methodology for longitudinal data synthesis | Synthetic longitudinal health data | Maintaining temporal trends and relationships | Enables research requiring time-series health data |

| Sun et al. (2021)[23] | Recurrent autoencoders and GANs | Longitudinal synthetic EHR data generation | Complexity of modeling temporal dependencies | Advances the synthesis of realistic time-series health records |

| Kosolwattana et al. (2023)[24] | Self-inspected adaptive SMOTE (SASMOTE) | Imbalanced healthcare data classification | Over-sampling without overfitting minority classes | Improves model performance on rare medical conditions |

| Nicolaie et al. (2023)[25] | Synthetic population construction | Big data applications in public health | Balancing population diversity and representativeness | Supports public health simulations and policy planning |

| Kumichev et al. (2024)[26] | LLM-based synthetic text generation | Medical text generation for research | Preservation of medical context and coherence | Facilitates NLP research and healthcare applications |

| Miletic & Sariyar (2024)[27] | Benchmark study | Tabular health data generation | Performance and accuracy trade-offs | Guides to the selection of appropriate synthetic data models |

| Juwara et al. (2024)[28] | Synthetic data augmentation | Mitigation of covariate bias in health data | Overcoming model biases and variability | Improve equity in health data analyses |

| Lomotey et al. (2024)[29] | Digital twins and data trusts | Privacy in health data sharing | Balancing privacy with data usability | Facilitates secure and ethical health data sharing |

| Osorio-Marulanda et al. (2024)[30] | Systematic review | Privacy and evaluation metrics for synthetic data | Standardization of metrics and methods | Improves trust in synthetic data for sensitive domains |

| Nicholas et al. (2024)[31] | Health Gym project | Synthetic datasets in education | Engaging learners without overwhelming complexity | Enriches data science and healthcare education |

| Patil et al. (2024)[32] | Transformer-based DGA integration | Improved ML-based fault identification | Complexity in data integration and scalability | Enhance fault detection in healthcare systems using synthetic data |

| Gonzales et al. (2023)[10] | Narrative review | Synthetic data in healthcare applications | Lack of standardization and ethical considerations | Encourages unified guidelines for healthcare data synthesis |

| Giuffrà & Shung (2023)[1] | Review on synthetic data innovation | Healthcare privacy and innovation | Balancing innovation with ethical responsibilities | Guides responsible for the use of synthetic data in health technologies |

| Qian et al. (2024)[8] | Privacy-preserving clinical risk prediction | Synthetic data for clinical applications | Data fidelity and privacy trade-offs | Facilitates secure predictive modeling in clinical research |

| Burgon et al. (2024)[33] | Bias amplification evaluation framework | Bias mitigation in healthcare ML models | Challenges in systematic bias evaluation | Improves fairness and accountability in AI healthcare tools |

| Koetzier et al. (2024)[34] | Medical imaging synthetic data generation | Enhancing medical imaging datasets | Quality and utility of synthetic images | Advances imaging tools for better diagnostic accuracy |

| Rodriguez-Almeida et al. (2022)[35] | Disease prediction on small datasets | Synthetic patient data for imbalanced datasets | Balancing small sample sizes with realistic data generation | Improves disease prediction accuracy in rare conditions |

| Shanley et al. (2024)[9] | Ethics-focused review | Synthetic data ethics in healthcare | Adoption of AI ethics principles | Strengthens ethical frameworks for synthetic data usage |

| Chen et al. (2021)[36] | ML applications in synthetic data | Medicine and healthcare | Reproducibility and validation of synthetic data models | Encourages robustness in AI model development for healthcare |

| Goyal & Mahmoud (2024)[37] | Systematic review of generative AI | Synthetic data generation techniques | Scalability and generalizability | Broadens understanding of generative methods |

| Tucker et al. (2020)[38] | High-fidelity synthetic patient data | Machine learning in healthcare software testing | Achieving realism in synthetic datasets | Enhances model validation and reliability in healthcare AI |

| Hairani et al. (2024)[39] |

Review of modified SMOTE strategies | Addressing class imbalance in health data | Adapting SMOTE for healthcare-specific needs | Improves handling of imbalanced datasets |

| Bigi et al. (2024)[40] | Agent-based modeling | Synthetic population for mobility analysis | Accurate parameterization and assumptions | Supports public health and operational planning |

| Guo & Zhao (2023)[41] | Survey of deep generative models for graph generation | Graph learning and representation | Scalability, permutation invariance, evaluation standards | Guides future research on graph-based data generation |

| Iannucci et al. (2017)[42] | Benchmarking of graph-based synthetic data generators | Intrusion detection system benchmarking | Model robustness and generalizability across attacks | Informs IDS design with realistic benchmark datasets |

| Haleem et al. (2023)[43] | Deep learning for multimodal health data synthesis | Real-time multimodal health data generation | Cross-modal consistency and real-time generation | Enables richer datasets for health monitoring systems |

| Pawłowski et al. (2023)[44] | Comparative analysis of multimodal data fusion methods | Sensor fusion and integration strategies | Selecting appropriate fusion strategy for task needs | Supports development of task-specific fusion pipelines |

| Gogoshin et al. (2021)[45] | Bayesian networks for probabilistic data generation | Biological simulation and data reconstruction | High-dimensional sampling and structural accuracy | Validates BNs as interpretable simulation frameworks |

| Kaur et al. (2020)[46] | Bayesian network application to synthetic health data | Synthetic health data generation and evaluation | Preserving associations and rare events | Shows BNs outperform deep models in certain tasks |

| Hosseini & Serag (2025)[47] | Diffusion models for synthetic medical image generation | Synthetic chest X-ray generation and model pretraining | Maintaining clinical fidelity and training stability | Demonstrates strong performance without real data |

| Naseer et al. (2023)[48] | Continuous-time diffusion model using stochastic differential equations | Electronic health record synthesis | Modeling long-term temporal dependencies and clinical coherence | Advances EHR generation with high realism and improved utility for downstream tasks |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).