Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Defining the High-Risk Patient and the Limits of Standard of Care

2.1. A Heterogeneous Definition: Comparing International Guidelines

2.2. The Sobering Reality of Recurrence and Mortality

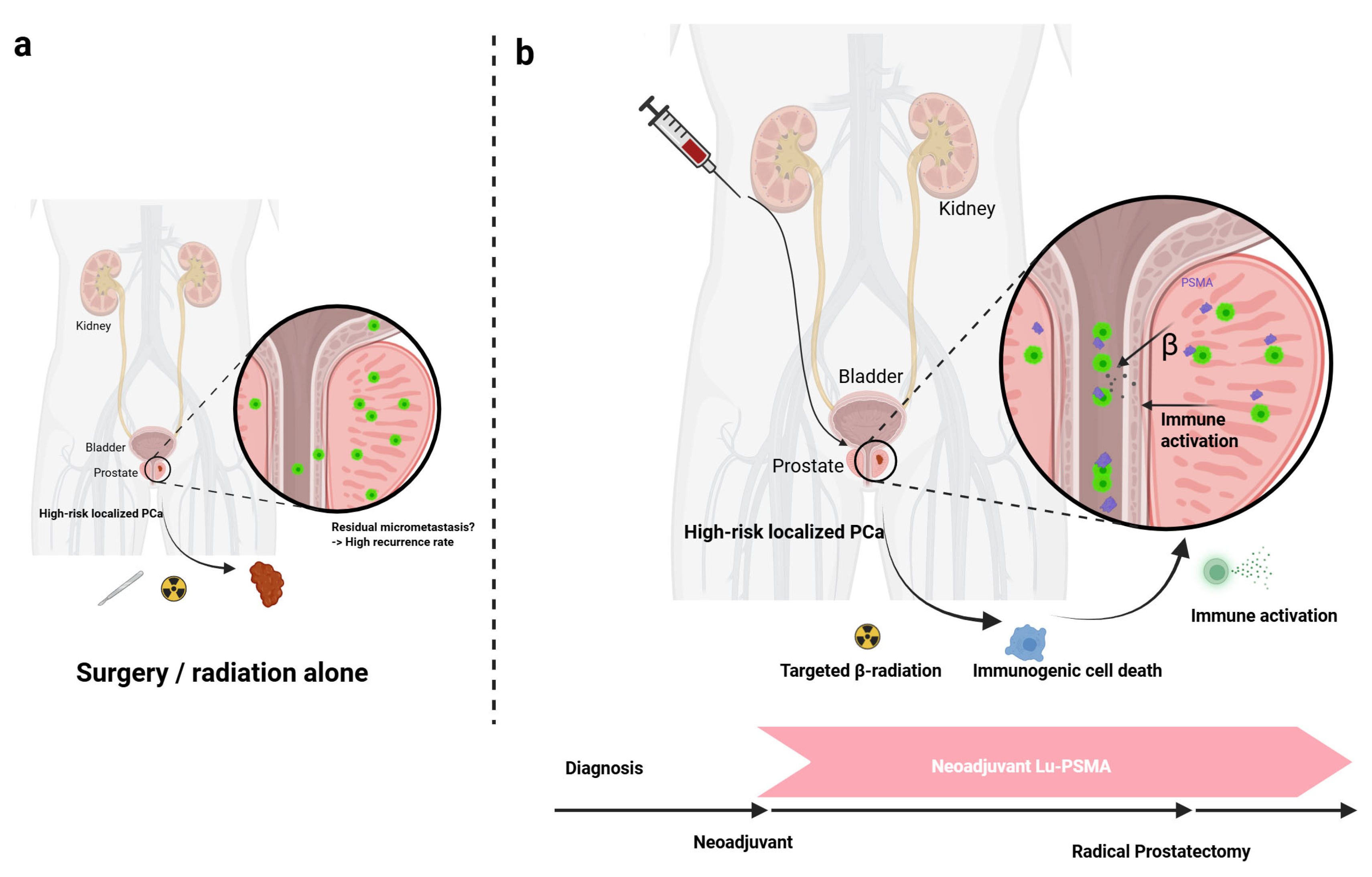

2.3. The Rationale for a Neoadjuvant Approach

3. The Theranostic Foundation: PSMA-Targeted Radioligand Therapy

3.1. Mechanism of Action of 177Lu-PSMA-617

3.2. Pivotal Evidence from the Metastatic Setting

3.3. The Radiobiological Imperative: Beta- versus Alpha-Emitters

4. Emerging Evidence for Neoadjuvant 177Lu-PSMA Radioligand Therapy

4.1. Preclinical Rationale and Early Human Experience

4.2. Initial Clinical Trial Data: The LuTectomy Study

4.3. The Next Frontier in Trial Design: An Overview of Ongoing Studies

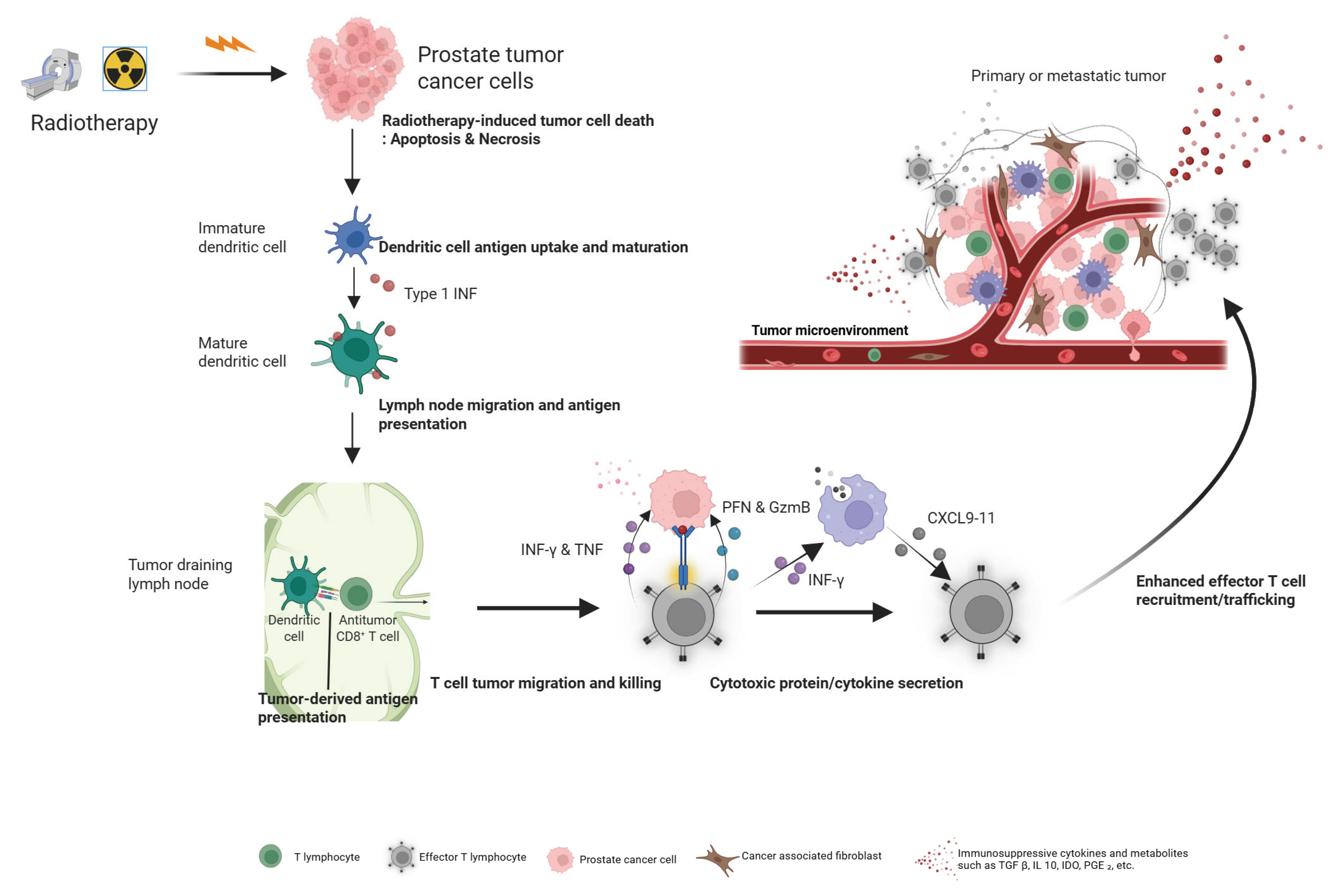

5. The Immunomodulatory Potential of Neoadjuvant Radioligand Therapy

5.1. Inducing an In Situ Vaccine Effect

5.2. A Hypothesis-Generating Biomarker: The PD-L2 Signature

6. Optimizing Efficacy: Combination Strategies and Sequencing

6.1. Synergy with Immunotherapy

6.2. Interplay with PARP Inhibitors: Evidence of Cross-Resistance

6.3. Modulating the Target: The "PSMA Flare" Phenomenon

7. Navigating the Path to Clinical Implementation

7.1. Validating Endpoints for Accelerated Approval: The Role of MFS

7.2. Detecting Minimal Residual Disease with Circulating Tumor DNA

7.3. Key Hurdles in Clinical Adoption

8. Conclusion and Future Directions

8.1. Summary of the Potential for Neoadjuvant RLT to Reshape the Treatment Paradigm

8.2. Key Unanswered Questions and the Roadmap for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schaeffer, E.M.; Srinivas, S.; Adra, N.; An, Y.; Bitting, R.; Chapin, B.; Cheng, H.H.; D’Amico, A.V.; Desai, N.; Dorff, T.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Prostate Cancer, Version 3.2024: Featured Updates to the NCCN Guidelines. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2024, 22, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, C.V.; Pereira, F.; Câmara, J.S.; Pereira, J.A.M. Underlying Features of Prostate Cancer-Statistics, Risk Factors, and Emerging Methods for Its Diagnosis. Curr Oncol 2023, 30, 2300–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez Rivas, J.; Ortega Polledo, L.E.; De La Parra Sánchez, I.; Gutiérrez Hidalgo, B.; Martín Monterrubio, J.; Marugán Álvarez, M.J.; Somani, B.K.; Enikeev, D.; Puente Vázquez, J.; Sanmamed Salgado, N. Current Status of Neoadjuvant Treatment Before Surgery in High-Risk Localized Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2024, 17, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagawa, Y.; Smith, J.J.; Fokas, E.; Watanabe, J.; Cercek, A.; Greten, F.R.; Bando, H.; Shi, Q.; Garcia-Aguilar, J.; Romesser, P.B. Future direction of total neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2024, 21, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Nguyen, N.T.; Sainsbury, F.; Kimizuka, N.; Muyldermans, S.; Benešová-Schäfer, M. PSMA-targeted radiotheranostics in modern nuclear medicine: then, now, and what of the future? Theranostics 2024, 14, 3043–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhoacha, M.; Riet, K.; Motloung, P.; Gumenku, L.; Adegoke, A.; Mashele, S. Prostate cancer review: genetics, diagnosis, treatment options, and alternative approaches. Molecules 2022, 27, 5730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Prostate Cancer Version 2.2025. Available online: https://www.nccn.org (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG Guidelines Panel on Prostate Cancer. EAU Guidelines on Prostate Cancer [Internet]. Arnhem, The Netherlands: EAU Guidelines Office; 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 26]. Available from: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer.

- Eastham, J.A.; Auffenberg, G.B.; Barocas, D.A.; Chou, R.; Crispino, T.; Davis, J.W.; Eggener, S.; Horwitz, E.M.; Kane, C.J.; Kirkby, E. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO guideline, part I: introduction, risk assessment, staging, and risk-based management. The Journal of urology 2022, 208, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetto, F.; Musone, M.; Chianese, S.; Conforti, P.; Digitale Selvaggio, G.; Caputo, V.F.; Falabella, R.; Del Giudice, F.; Giulioni, C.; Cafarelli, A.; et al. Blood and urine-based biomarkers in prostate cancer: Current advances, clinical applications, and future directions. J Liq Biopsy 2025, 9, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, P.; Ravizzini, G.; Chapin, B.F.; Kundra, V. Imaging Biochemical Recurrence After Prostatectomy: Where Are We Headed? American Journal of Roentgenology 2020, 214, 1248–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinshtein, D.; Teng, B.; Valencia, A.; Gibbons, R.; Porter, C.R. The long-term outcomes after radical prostatectomy of patients with pathologic Gleason 8–10 disease. Advances in urology 2012, 2012, 428098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, F.C.; Donovan, J.L.; Lane, J.A.; Mason, M.; Metcalfe, C.; Holding, P.; Davis, M.; Peters, T.J.; Turner, E.L.; Martin, R.M.; et al. 10-Year Outcomes after Monitoring, Surgery, or Radiotherapy for Localized Prostate Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2016, 375, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichman, L. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for disseminated colorectal cancer: changing the paradigm. 2006, 24, 3817-3818.

- Hirmas, N.; Holtschmidt, J.; Loibl, S. Shifting the paradigm: the transformative role of neoadjuvant therapy in early breast cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häberle, L.; Erber, R.; Gass, P.; Hein, A.; Niklos, M.; Volz, B.; Hack, C.C.; Schulz-Wendtland, R.; Huebner, H.; Goossens, C. Prediction of pathological complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for HER2-negative breast cancer patients with routine immunohistochemical markers. Breast Cancer Research 2025, 27, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, F.M.; He, G.; Peterson, J.R.; Pfeiffer, J.; Earnest, T.; Pearson, A.T.; Abe, H.; Cole, J.A.; Nanda, R. Highly accurate response prediction in high-risk early breast cancer patients using a biophysical simulation platform. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2022, 196, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Der Slot, M.A.; Remmers, S.; Kweldam, C.F.; den Bakker, M.A.; Nieboer, D.; Busstra, M.B.; Gan, M.; Klaver, S.; Rietbergen, J.B.; van Leenders, G.J. Biopsy prostate cancer perineural invasion and tumour load are associated with positive posterolateral margins at radical prostatectomy: implications for planning of nerve-sparing surgery. Histopathology 2023, 83, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aredo, J.V.; Jamali, A.; Zhu, J.; Heater, N.; Wakelee, H.A.; Vaklavas, C.; Anagnostou, V.; Lu, J. Liquid Biopsy Approaches for Cancer Characterization, Residual Disease Detection, and Therapy Monitoring. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 2025, 45, e481114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie SW, Soon-Sutton TL, Skelton WP. Prostate Cancer. [Updated 2024 Oct 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470550/.

- Wang, F.; Li, Z.; Feng, X.; Yang, D.; Lin, M. Advances in PSMA-targeted therapy for prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases 2022, 25, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Kadeerhan, G.; Zhang, J.; Guo, W.; Guo, H.; Wang, D. Advances in prostate-specific membrane antigen-targeted theranostics: from radionuclides to near-infrared fluorescence technology. Frontiers in Immunology 2025, 15, 1533532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corpetti, M.; Mueller, C.; Beltran, H.; de Bono, J.; Theurillat, J.-P. Prostate-specific membrane antigen–Targeted therapies for Prostate cancer: towards improving therapeutic outcomes. European urology 2024, 85, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennrich, U.; Eder, M. [177Lu] Lu-PSMA-617 (PluvictoTM): the first FDA-approved radiotherapeutical for treatment of prostate cancer. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, W.; Wong, P.; Freedman, N. Dose distributions for electrons and beta rays incident normally on water. Radiation protection dosimetry 1991, 35, 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Delbart, W.; Karabet, J.; Marin, G.; Penninckx, S.; Derrien, J.; Ghanem, G.E.; Flamen, P.; Wimana, Z. Understanding the radiobiological mechanisms induced by 177Lu-DOTATATE in comparison to external beam radiation therapy. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 12369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.; Hesterman, J.; Rahbar, K.; Kendi, A.T.; Wei, X.X.; Fang, B.; Adra, N.; Armstrong, A.J.; Garje, R.; Michalski, J.M. [68Ga] Ga-PSMA-11 PET baseline imaging as a prognostic tool for clinical outcomes to [177Lu] Lu-PSMA-617 in patients with mCRPC: A VISION substudy. 2022.

- Ling, S.W.; de Lussanet de la Sablonière, Q.; Ananta, M.; de Blois, E.; Koolen, S.L.W.; Drexhage, R.C.; Hofland, J.; Robbrecht, D.G.J.; van der Veldt, A.A.M.; Verburg, F.A.; et al. First real-world clinical experience with [(177)Lu]Lu-PSMA-I&T in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer beyond VISION and TheraP criteria. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2025, 52, 2034–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartor, O.; De Bono, J.; Chi, K.N.; Fizazi, K.; Herrmann, K.; Rahbar, K.; Tagawa, S.T.; Nordquist, L.T.; Vaishampayan, N.; El-Haddad, G. Lutetium-177–PSMA-617 for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 385, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, M.S.; Emmett, L.; Sandhu, S.; Iravani, A.; Buteau, J.P.; Joshua, A.M.; Goh, J.C.; Pattison, D.A.; Tan, T.H.; Kirkwood, I.D. Overall survival with [177Lu] Lu-PSMA-617 versus cabazitaxel in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (TheraP): secondary outcomes of a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Oncology 2024, 25, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuradova, E.; Seyyar, M.; Arak, H.; Tamer, F.; Kefeli, U.; Koca, S.; Sen, E.; Telli, T.A.; Karatas, F.; Gokmen, I.; et al. The real-world outcomes of Lutetium-177 PSMA-617 radioligand therapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: Turkish Oncology Group multicenter study. Int J Cancer 2024, 154, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofman, M.S.; Violet, J.; Hicks, R.J.; Ferdinandus, J.; Thang, S.P.; Akhurst, T.; Iravani, A.; Kong, G.; Ravi Kumar, A.; Murphy, D.G.; et al. [(177)Lu]-PSMA-617 radionuclide treatment in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (LuPSMA trial): a single-centre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2018, 19, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassis, A.I. Therapeutic radionuclides: biophysical and radiobiologic principles. Semin Nucl Med 2008, 38, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russ, E.; Davis, C.M.; Slaven, J.E.; Bradfield, D.T.; Selwyn, R.G.; Day, R.M. Comparison of the medical uses and cellular effects of high and low linear energy transfer radiation. Toxics 2022, 10, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertinetti, A.; Palmer, B.; Bradshaw, T.; Culberson, W. Investigation of a measurement-based dosimetry approach to beta particle-emitting radiopharmaceutical therapy nuclides across tissue interfaces. Physics in Medicine & Biology 2024, 69, 125008. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, M.; Jakobsson, V.; Greifenstein, L.; Khong, P.-L.; Chen, X.; Baum, R.P.; Zhang, J. Alpha-peptide receptor radionuclide therapy using actinium-225 labeled somatostatin receptor agonists and antagonists. Frontiers in medicine 2022, 9, 1034315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavragani, I.V.; Nikitaki, Z.; Kalospyros, S.A.; Georgakilas, A.G. Ionizing radiation and complex DNA damage: from prediction to detection challenges and biological significance. Cancers 2019, 11, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.P.; Lin, F.I.; Escorcia, F.E. Why bother with alpha particles? European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 2021, 49, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballisat, L.; De Sio, C.; Beck, L.; Guatelli, S.; Sakata, D.; Shi, Y.; Duan, J.; Velthuis, J.; Rosenfeld, A. Dose and DNA damage modelling of diffusing alpha-emitters radiation therapy using Geant4. Physica Medica 2024, 121, 103367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepareur, N.; Ramée, B.; Mougin-Degraef, M.; Bourgeois, M. Clinical Advances and Perspectives in Targeted Radionuclide Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagawa, S.T.; Fung, E.; Niaz, M.O.; Bissassar, M.; Singh, S.; Patel, A.; Tan, A.; Zuloaga, J.M.; Castellanos, S.H.; Nauseef, J.T. Abstract CT143: Results of combined targeting of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) with alpha-radiolabeled antibody 225Ac-J591 and beta-radiolabeled ligand 177Lu-PSMA I&T: preclinical and initial phase 1 clinical data in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Cancer Research 2022, 82, CT143–CT143. [Google Scholar]

- Bruchertseifer, F.; Kellerbauer, A.; Malmbeck, R.; Morgenstern, A. Targeted alpha therapy with bismuth-213 and actinium-225: meeting future demand. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals 2019, 62, 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, A.; Pillai, M.R.; Knapp, F.F., Jr. Production of (177)Lu for Targeted Radionuclide Therapy: Available Options. Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2015, 49, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouri, M.A.; Georgopoulos, A.; Manios, G.E.; Maratou, E.; Spathis, A.; Chatziioannou, S.; Platoni, K.; Efstathopoulos, E.P. Preliminary Study on Lutetium-177 and Gold Nanoparticles: Apoptosis and Radiation Enhancement in Hepatic Cancer Cell Line. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2024, 46, 12244–12259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brans, B.; Mottaghy, F.M.; Kessels, A. 90Y/177Lu-DOTATATE therapy: survival of the fittest? European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging 2011, 38, 1785–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, G.; Breistøl, K.; Bruland, Ø.S.; Fodstad, Ø.; Larsen, R.H. Significant antitumor effect from bone-seeking, α-particle-emitting 223Ra demonstrated in an experimental skeletal metastases model. Cancer research 2002, 62, 3120–3125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miederer, M.; Scheinberg, D.A.; McDevitt, M.R. Realizing the potential of the Actinium-225 radionuclide generator in targeted alpha particle therapy applications. Advanced drug delivery reviews 2008, 60, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheinberg, D.A.; McDevitt, M.R. Actinium-225 in targeted alpha-particle therapeutic applications. Curr Radiopharm 2011, 4, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, E.E.; Savir-Baruch, B.; Gayed, I.W.; Almaguel, F.; Chin, B.B.; Pantel, A.R.; Armstrong, E.; Morley, A.; Ippisch, R.C.; Flavell, R.R. 177Lu-PSMA therapy. Journal of nuclear medicine technology 2022, 50, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxton, C.; Waldron, B.; Grønlund, R.V.; Simón, J.J.; Cornelissen, B.; O’Neill, E.; Stevens, D. Preclinical Evaluation of 177Lu-rhPSMA-10.1, a Radiopharmaceutical for Prostate Cancer: Biodistribution and Therapeutic Efficacy. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2025, 66, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghazo, O.; Eapen, R.; Dhiantravan, N.; Violet, J.A.; Jackson, P.; Scalzo, M.; Keam, S.P.; Mitchell, C.; Neeson, P.J.; Sandhu, S.K.; et al. Study of the dosimetry, safety, and potential benefit of 177Lu-PSMA-617 radionuclide therapy prior to radical prostatectomy in men with high-risk localized prostate cancer (LuTectomy study). Journal of Clinical Oncology 2021, 39, TPS264–TPS264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eapen, R.S.; Buteau, J.P.; Jackson, P.; Mitchell, C.; Oon, S.F.; Alghazo, O.; McIntosh, L.; Dhiantravan, N.; Scalzo, M.J.; O'Brien, J.; et al. Administering [(177)Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 Prior to Radical Prostatectomy in Men with High-risk Localised Prostate Cancer (LuTectomy): A Single-centre, Single-arm, Phase 1/2 Study. Eur Urol 2024, 85, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.A.; Soydal, C.; Virgolini, I.; Tuncel, M.; Kairemo, K.; Kapp, D.S.; von Eyben, F.E. Management Based on Pretreatment PSMA PET of Patients with Localized High-Risk Prostate Cancer Part 2: Prediction of Recurrence—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2025, 17, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, U.; Grünwald, V.; Fendler, W.P.; Herrmann, K.; Reis, H.; Roghmann, F.; Rahbar, K.; Heidenreich, A.; Giesel, F.L.; Niegisch, G.; et al. A randomized phase I/II study of neoadjuvant treatment with 177-Lutetium-PSMA-617 with or without ipilimumab in patients with very high-risk prostate cancer who are candidates for radical prostatectomy (NEPI trial). Journal of Clinical Oncology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartor, A.O.; Kiess, A.P.; Feng, F.Y.; Hadaschik, B.A.; Herrmann, K.; Iagaru, A.; Matsubara, N.; Morris, M.J.; Nguyen, P.L.; Shore, N.D.; et al. PSMA-delay castration (DC): An open-label, multicenter, randomized phase 3 study of [<sup>177</sup>Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 versus observation in patients with metachronous PSMA-positive oligometastatic prostate cancer (OMPC). Journal of Clinical Oncology 2025, 43, TPS5127–TPS5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, D.; Yu, J. Radiotherapy combined with immunotherapy: the dawn of cancer treatment. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handke, A.; Kesch, C.; Fendler, W.P.; Telli, T.; Liu, Y.; Hakansson, A.; Davicioni, E.; Hughes, J.; Song, H.; Lueckerath, K.; et al. Analysing the tumor transcriptome of prostate cancer to predict efficacy of Lu-PSMA therapy. J Immunother Cancer 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fucikova, J.; Kepp, O.; Kasikova, L.; Petroni, G.; Yamazaki, T.; Liu, P.; Zhao, L.; Spisek, R.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. Detection of immunogenic cell death and its relevance for cancer therapy. Cell Death & Disease 2020, 11, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barjij, I.; Meliani, M. Immunogenic Cell Death as a Target for Combination Therapies in Solid Tumors: A Systematic Review Toward a New Paradigm in Immuno-Oncology. Cureus 2025, 17, e85776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, S.; Subramaniam, S.; Hofman, M.S.; Stockler, M.R.; Martin, A.J.; Pokorski, I.; Goh, J.C.; Pattison, D.A.; Dhiantravan, N.; Gedye, C. Evolution: Phase II study of radionuclide 177Lu-PSMA-617 therapy versus 177Lu-PSMA-617 in combination with ipilimumab and nivolumab for men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC; ANZUP 2001). 2023.

- Strati, A.; Adamopoulos, C.; Kotsantis, I.; Psyrri, A.; Lianidou, E.; Papavassiliou, A.G. Targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway for cancer therapy: focus on biomarkers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozali, E.N.; Hato, S.V.; Robinson, B.W.; Lake, R.A.; Lesterhuis, W.J. Programmed death ligand 2 in cancer-induced immune suppression. Clin Dev Immunol 2012, 2012, 656340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Qu, Y.; Yang, J.; Shao, T.; Kuang, J.; Liu, C.; Qi, Y.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; et al. PD-L2 act as an independent immune checkpoint in colorectal cancer beyond PD-L1. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1486888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Gu, R.; Chen, J.; Chen, Q.; Lin, T.; Wu, J.; Hu, Y.; Yuan, A. In Situ Vaccination with Mitochondria-Targeting Immunogenic Death Inducer Elicits CD8(+) T Cell-Dependent Antitumor Immunity to Boost Tumor Immunotherapy. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2023, 10, e2300286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J.d.; Mateo, J.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Shore, N.; Sandhu, S.; Chi, K.N.; Sartor, O.; Agarwal, N.; Olmos, D.; et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 382, 2091–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Chu, A.; Song, R.; Liu, S.; Chai, T.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z. PARP inhibitors combined with radiotherapy: are we ready? Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1234973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raychaudhuri, R.; Tuchayi, A.M.; Low, S.K.; Arafa, A.T.; Graham, L.S.; Gulati, R.; Pritchard, C.C.; Montgomery, R.B.; Haffner, M.C.; Nelson, P.S.; et al. Association of Prior PARP Inhibitor Exposure with Clinical Outcomes after (177)Lu-PSMA-617 in Men with Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer and Mutations in DNA Homologous Recombination Repair Genes. Eur Urol Oncol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berchuck, J.E.; Zhang, Z.; Silver, R.; Kwak, L.; Xie, W.; Lee, G.-S.M.; Freedman, M.L.; Kibel, A.S.; Van Allen, E.M.; McKay, R.R.; et al. Impact of Pathogenic Germline DNA Damage Repair alterations on Response to Intense Neoadjuvant Androgen Deprivation Therapy in High-risk Localized Prostate Cancer. European Urology 2021, 80, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Gaag, S.; Vis, A.N.; Bartelink, I.H.; Koppes, J.C.C.; Hodolic, M.; Hendrikse, H.; Oprea-Lager, D.E. Exploring the Flare Phenomenon in Patients with Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Enzalutamide-Induced PSMA Upregulation Observed on PSMA PET. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2025, jnumed.124.268340. [CrossRef]

- Mei, R.; Bracarda, S.; Emmett, L.; Farolfi, A.; Lambertini, A.; Fanti, S.; Castellucci, P. Androgen deprivation therapy and its modulation of PSMA expression in prostate cancer: mini review and case series of patients studied with sequential [68Ga]-Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT. Clinical and Translational Imaging 2021, 9, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacho, H.D.; Petersen, L.J. Bone flare to androgen deprivation therapy in metastatic, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer on 68Ga-prostate-specific membrane antigen PET/CT. Clinical Nuclear Medicine 2018, 43, e404–e406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, A.J.; Kattan, M.W.; Eastham, J.A.; Bianco, F.J., Jr.; Yossepowitch, O.; Vickers, A.J.; Klein, E.A.; Wood, D.P.; Scardino, P.T. Prostate cancer-specific mortality after radical prostatectomy for patients treated in the prostate-specific antigen era. J Clin Oncol 2009, 27, 4300–4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, W.; Regan, M.M.; Buyse, M.; Halabi, S.; Kantoff, P.W.; Sartor, O.; Soule, H.; Clarke, N.W.; Collette, L.; Dignam, J.J.; et al. Metastasis-Free Survival Is a Strong Surrogate of Overall Survival in Localized Prostate Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2017, 35, 3097–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Ravi, P.; Buyse, M.; Halabi, S.; Kantoff, P.; Sartor, O.; Soule, H.; Clarke, N.; Dignam, J.; James, N.; et al. Validation of metastasis-free survival as a surrogate endpoint for overall survival in localized prostate cancer in the era of docetaxel for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Ann Oncol 2024, 35, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Mei, W.; Ma, K.; Zeng, C. Circulating Tumor DNA and Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) in Solid Tumors: Current Horizons and Future Perspectives. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, Volume 11 - 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zang, P.D.; Lama, D.; Huang, Z.; Jaime-Casas, S.; Contente-Cuomo, T.; Stampar, M.; Marshall, A.; Dinwiddie, D.; Berens, M.E.; Pond, S.; et al. Feasibility of enriched amplicon circulating tumor DNA sequencing to detect minimal residual disease (MRD) after prostatectomy in localized prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2025, 43, 402–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrens, D.; Kramer, K.K.M.; Unterrainer, L.M.; Beyer, L.; Bartenstein, P.; Froelich, M.F.; Tollens, F.; Ricke, J.; Rübenthaler, J.; Schmidt-Hegemann, N.-S.; et al. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of 177Lu-PSMA-617 Radioligand Therapy in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2023, 21, 43–50.e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Guideline | High-Risk Criteria | Very High-Risk Criteria | Key Features & Differences |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCCN (2025) [7] | One or more of the following: • Clinical stage cT3-cT4 • Grade Group 4 or 5 • PSA > 20 ng/mL |

Designated as Very High-Risk. Two or more of the following: • cT3-cT4 • Grade Group 4-5 • PSA > 40 ng/mL |

• Clearly defines separate "High-Risk" and "Very High-Risk" categories. • Uses a higher PSA threshold (40 ng/mL) for the Very High-Risk definition. |

| EAU (2025) [8] | Two or more of the following: • cT3-cT4 • Gleason Score 8-10 (GG 4-5) • PSA ≥ 40 ng/mL |

Designated as Very High-Risk. • Node-positive (N1) disease • Or meeting the high-risk criteria above (if node-negative) |

• The definition of "High-Risk" is much stricter than NCCN's, requiring 2 factors and a higher PSA threshold. • Explicitly includes N1 disease in the Very High-Risk category. |

| AUA/ASTRO/SUO (2022) [9] | One or more of the following: • cT3a • Grade Group 4-5 • PSA > 20 ng/mL |

No separate "Very High-Risk" category. Instead, these are classified as "Locally Advanced Disease": • cT3b-T4 (seminal vesicle invasion or beyond) • Presence of multiple high-risk features • Pelvic node positivity |

• Maintains a three-tier risk system and does not use the "Very High-Risk" terminology. • The High-Risk T-stage definition is more specific (cT3a). • The most advanced cases are managed as "Locally Advanced," emphasizing a multimodal approach. |

| Radionuclide | Particle Emitted | Half-life | Max Energy (MeV) | Max Range in Tissue | Typical LET (keV/µm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 177Lu [43,44] | Beta (β) | 6.7 days | 0.497 | ~2 mm | ~0.2 |

| 90Y [45] | Beta (β) | 2.7 days | 2.3 | ~11 mm | ~0.2 |

| 223Ra [46] | Alpha (α) | 11.4 days | 5.0-7.5 | 40-100 µm | ~80 |

| 225Ac [47,48] | Alpha (α) | 9.9 days | 5.0-8.4 | 40-100 µm | ~100 |

| Trial Name (Identifier) | Phase | Patient Population | Intervention(s) | Primary Endpoint(s) | Key Secondary Endpoints |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LuTectomy (NCT04430192) [51] | I/II | High-risk localized/locoregional PCa (n=20) | Single cycle of 177Lu-PSMA-617 prior to RP | Absorbed radiation dose (dosimetry) | Safety, surgical feasibility, PSA response, imaging response, pathological response |

| NEPI (EudraCT 2021-004894-30) [54] | I/II | Very high-risk localized PCa (n=46) | ADT + 2 cycles 177Lu-PSMA-617 +/- 4 cycles ipilimumab prior to RP | Feasibility of RP, pCR | Safety, DFS |

| PSMA-DC [55] | III | Oligometastatic (≤5 lesions) recurrence post-local therapy (n=~450) | SBRT to all lesions, then 177Lu-PSMA-617 vs. Observation | MFS | Time to next hormonal therapy, OS, safety |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).