Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

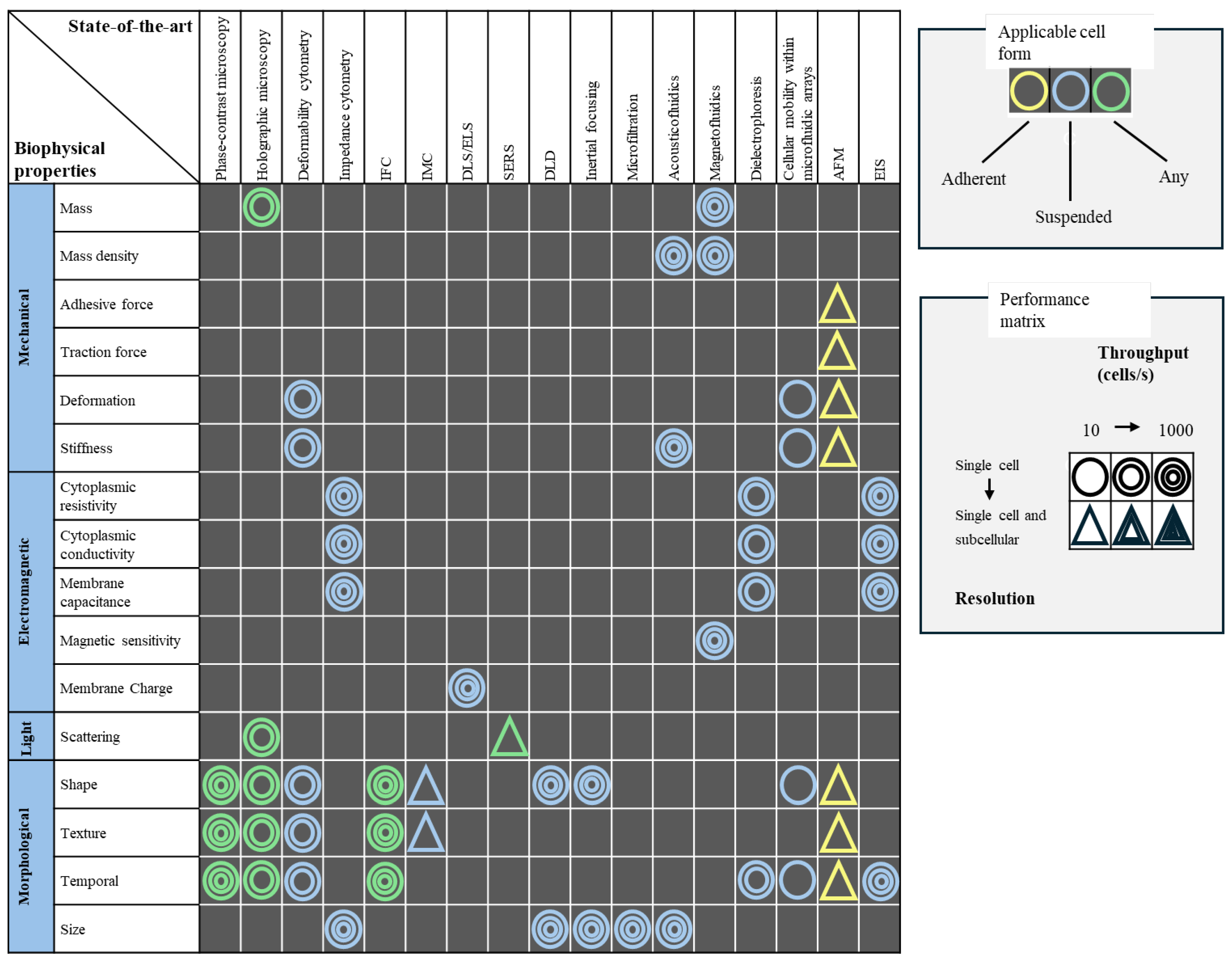

2. Label-Free Microscopy Techniques for Cellular Analysis

2.1. Phase-Contrast Microscopy–Morphological Profiling and Segmentation

2.2. Holographic Microscopy: Quantitative Phase Imaging for 3D Characterization

3. Cytometric Techniques

3.1. Deformability Cytometry: Mechanical Fingerprinting of Cells

3.2. Impedance Cytometry: Electrical Cell Characterization

3.3. Imaging Flow Cytometry: High-Throughput Morphological and Functional Analysis

3.3.1. Multimodal Integration and AI-Enhanced Applications in IFC

4. Cell and Particle Scattering Techniques

4.1. Dynamic Light Scattering and Zeta Potential

4.2. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy

5. Microfluidics Systems for Cellular Analysis

5.1. Passive Cell Separation Microfluidics

5.1.1. Deterministic Lateral Displacement

5.1.2. Inertial Focusing and Centrifugal Microfluidics

5.1.3. Microfiltration

5.2. Active Cell Separation Microfluidic

5.2.1. Acoustofluidics

5.2.2. Magnetofluidics

5.2.3. Dielectrophoresis Microfluidics

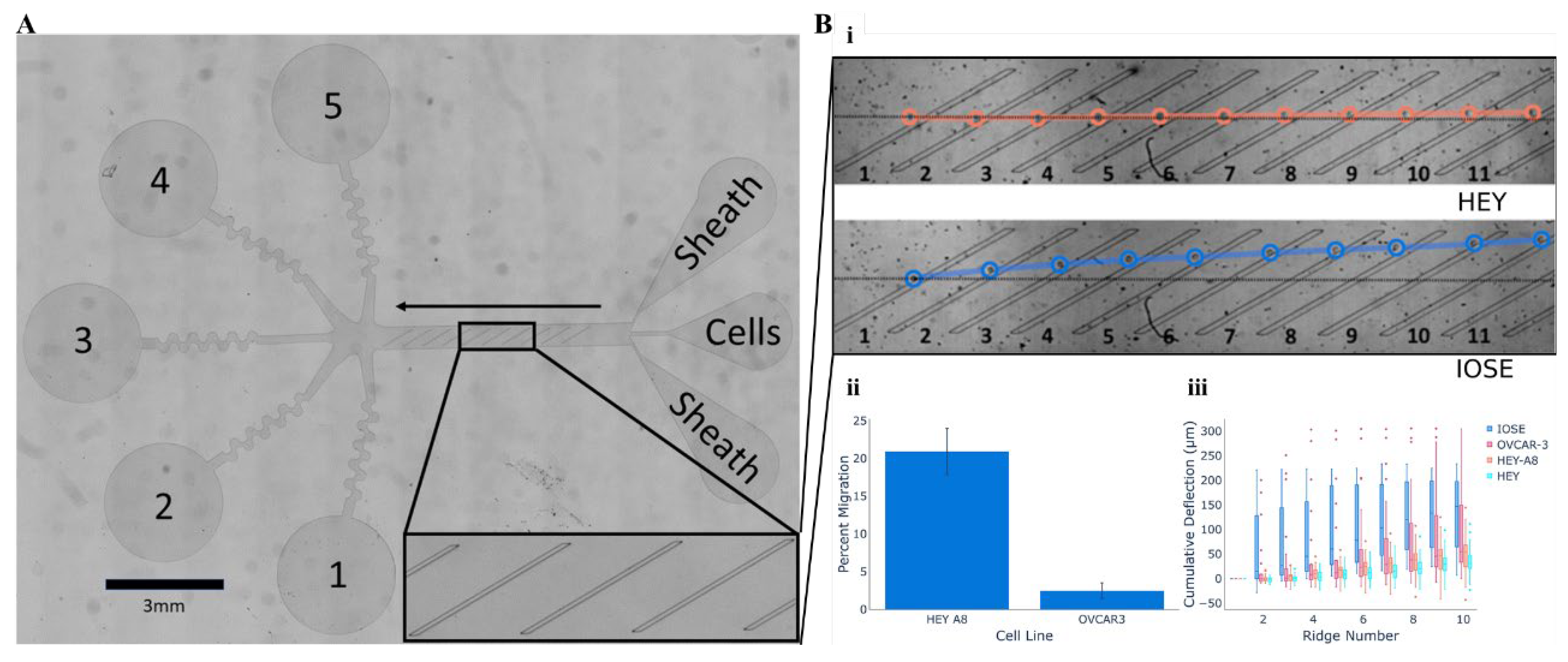

5.3. Cellular Mobility Within Microfluidic Arrays

6. Electro-mechanical and Surface Characterization

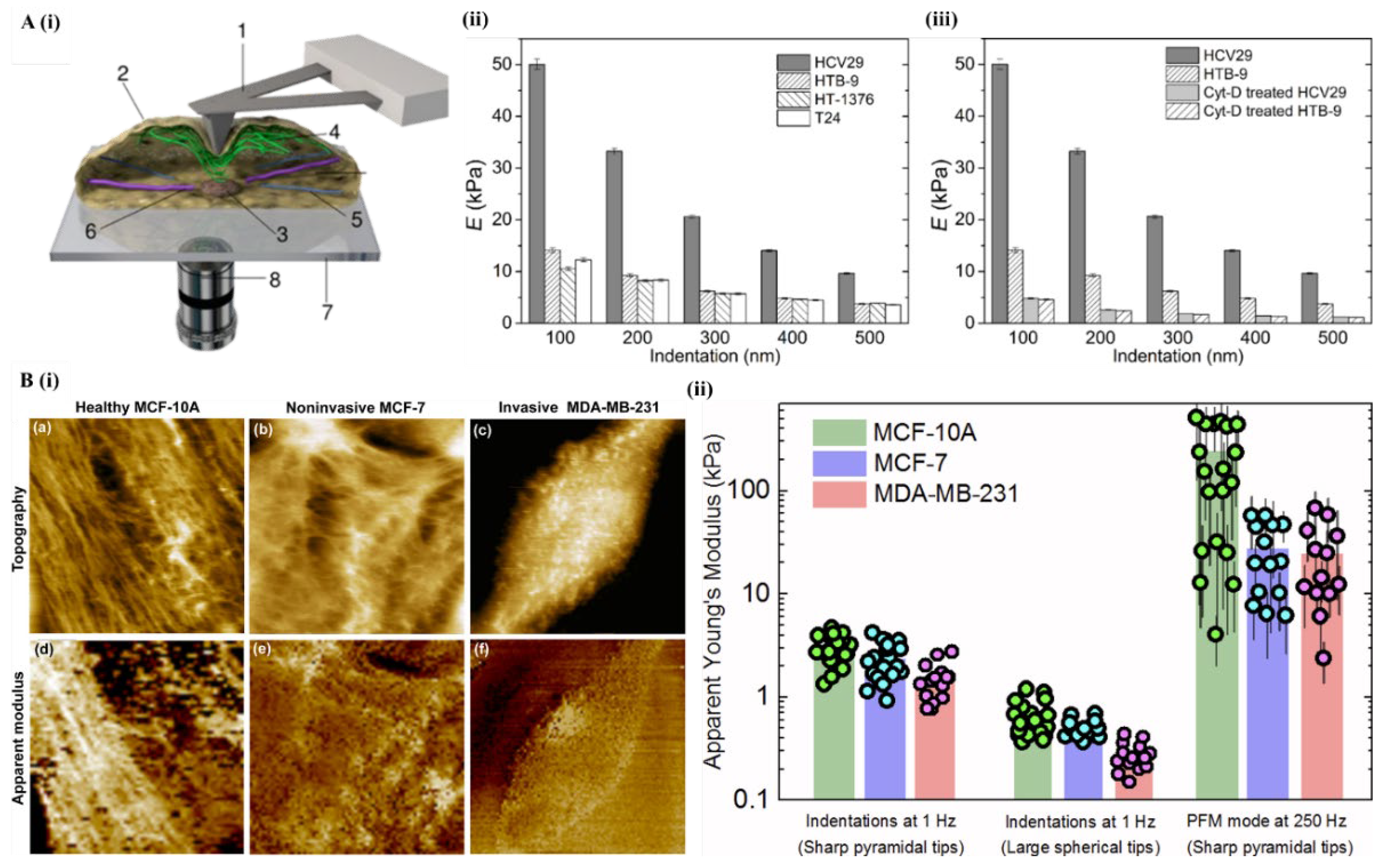

6.1. Atomic Force Microscopy

6.2. Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy

7. Clinical Translation

8. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/ (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Jayanthi, V.S.P.K.S.A.; Das, A.B.; Saxena, U. Recent Advances in Biosensor Development for the Detection of Cancer Biomarkers. Biosens Bioelectron 2017, 91, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/ (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Pulumati, A.; Pulumati, A.; Dwarakanath, B.S.; Verma, A.; Papineni, R.V.L. Technological Advancements in Cancer Diagnostics: Improvements and Limitations. Cancer Rep 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syedmoradi, L.; Norton, M.L.; Omidfar, K. Point-of-Care Cancer Diagnostic Devices: From Academic Research to Clinical Translation. Talanta 2021, 225, 122002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.C. de; Caires, H.R.; Oliveira, M.J.; Fraga, A.; Vasconcelos, M.H.; Ribeiro, R. Urinary Biomarkers in Bladder Cancer: Where Do We Stand and Potential Role of Extracellular Vesicles. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zou, L.; Guan, Y.; Jiang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Ren, H.; Li, Z.; Niu, H.; et al. Survivin as a Potential Biomarker in the Diagnosis of Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 2024, 42, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.X.; Liu, L.; Zhao, W. Targeting Biophysical Cues: A Niche Approach to Study, Diagnose, and Treat Cancer. Trends Cancer 2018, 4, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Barton, M.J.; Nguyen, N.-T. Biophysical Properties of Cells for Cancer Diagnosis. J Biomech 2019, 86, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Cao, L. Quantitative Phase Imaging Based on Holography: Trends and New Perspectives. Light Sci Appl 2024, 13, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangle, T.A.; Teitell, M.A. Live-Cell Mass Profiling: An Emerging Approach in Quantitative Biophysics. Nat Methods 2014, 11, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ker, D.F.E.; Eom, S.; Sanami, S.; Bise, R.; Pascale, C.; Yin, Z.; Huh, S.; Osuna-Highley, E.; Junkers, S.N.; Helfrich, C.J.; et al. Phase Contrast Time-Lapse Microscopy Datasets with Automated and Manual Cell Tracking Annotations. Sci Data 2018, 5, 180237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejna, M.; Jorapur, A.; Song, J.S.; Judson, R.L. High Accuracy Label-Free Classification of Single-Cell Kinetic States from Holographic Cytometry of Human Melanoma Cells. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 11943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boya, M.; Ozkaya-Ahmadov, T.; Swain, B.E.; Chu, C.-H.; Asmare, N.; Civelekoglu, O.; Liu, R.; Lee, D.; Tobia, S.; Biliya, S.; et al. High Throughput, Label-Free Isolation of Circulating Tumor Cell Clusters in Meshed Microwells. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetefeld, J.; McKenna, S.A.; Patel, T.R. Dynamic Light Scattering: A Practical Guide and Applications in Biomedical Sciences. Biophys Rev 2016, 8, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshchi, F.; Hasanzadeh, M. Microfluidic Biosensing of Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs): Recent Progress and Challenges in Efficient Diagnosis of Cancer. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 134, 111153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasseur, A.; Kiavue, N.; Bidard, F.; Pierga, J.; Cabel, L. Clinical Utility of Circulating Tumor Cells: An Update. Mol Oncol 2021, 15, 1647–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovitt, R.W.; Wright, C.J. MICROSCOPY | Light Microscopy. In Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology; Elsevier, 1999; pp. 1379–1388.

- Douglas, B. Murphy; Ron Oldfield; Stanley Schwartz; Michael W. Davidson MicroscopyU–The Source for Microscopy Education.

- Pastorek, L.; Venit, T.; Hozák, P. Holography Microscopy as an Artifact-Free Alternative to Phase-Contrast. Histochem Cell Biol 2018, 149, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, H.; Chen, S.; Huang, Y.; Guan, Q. Cancer Cells Detection in Phase-Contrast Microscopy Images Based on Faster R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2016 9th International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Design (ISCID); IEEE, December 2016; pp. 363–367. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, T.J.; Zhang, X.; Mak, M. Biophysical Informatics Reveals Distinctive Phenotypic Signatures and Functional Diversity of Single-Cell Lineages. Bioinformatics 2023, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edlund, C.; Jackson, T.R.; Khalid, N.; Bevan, N.; Dale, T.; Dengel, A.; Ahmed, S.; Trygg, J.; Sjögren, R. LIVECell—A Large-Scale Dataset for Label-Free Live Cell Segmentation. Nat Methods 2021, 18, 1038–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Han, J.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, Y.; Yang, S. A Novel Method for Effective Cell Segmentation and Tracking in Phase Contrast Microscopic Images. Sensors 2021, 21, 3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beres, B.; Kovacs, K.D.; Kanyo, N.; Peter, B.; Szekacs, I.; Horvath, R. Label-Free Single-Cell Cancer Classification from the Spatial Distribution of Adhesion Contact Kinetics. ACS Sens 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calin, V.L.; Mihailescu, M.; Petrescu, G.E.D.; Lisievici, M.G.; Tarba, N.; Calin, D.; Ungureanu, V.G.; Pasov, D.; Brehar, F.M.; Gorgan, R.M.; et al. Grading of Glioma Tumors Using Digital Holographic Microscopy. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Altman, L.E.; Rawat, S.; Wang, A.; Grier, D.G.; Manoharan, V.N. In-Line Holographic Microscopy with Model-Based Analysis. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2022, 2, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Schich, Z. Digital Holographic Microscopy: A Noninvasive Method to Analyze the Formation of Spheroids. Biotechniques 2021, 71, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirone, D.; Bianco, V.; Miccio, L.; Memmolo, P.; Psaltis, D.; Ferraro, P. Beyond Fluorescence: Advances in Computational Label-Free Full Specificity in 3D Quantitative Phase Microscopy. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2024, 85, 103054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, D.P. Resolution Limits in Practical Digital Holographic Systems. Optical Engineering 2009, 48, 095801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Schich, Z.; Leida Mölder, A.; Gjörloff Wingren, A. Quantitative Phase Imaging for Label-Free Analysis of Cancer Cells—Focus on Digital Holographic Microscopy. Applied Sciences 2018, 8, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, F.; Yourassowsky, C.; Monnom, O.; Legros, J.-C.; Debeir, O.; Van Ham, P.; Kiss, R.; Decaestecker, C. Digital Holographic Microscopy for the Three-Dimensional Dynamic Analysis of in Vitro Cancer Cell Migration. J Biomed Opt 2006, 11, 054032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Á.G.; Székács, I.; Bonyár, A.; Horvath, R. Simple and Automatic Monitoring of Cancer Cell Invasion into an Epithelial Monolayer Using Label-Free Holographic Microscopy. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 10111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Schich, Z.; Mölder, A.; Tassidis, H.; Härkönen, P.; Falck Miniotis, M.; Gjörloff Wingren, A. Induction of Morphological Changes in Death-Induced Cancer Cells Monitored by Holographic Microscopy. J Struct Biol 2015, 189, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roitshtain, D.; Wolbromsky, L.; Bal, E.; Greenspan, H.; Satterwhite, L.L.; Shaked, N.T. Quantitative Phase Microscopy Spatial Signatures of Cancer Cells. Cytometry Part A 2017, 91, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-K.; Lee, B.-W.; Fujii, F.; Kim, J.K.; Pack, C.-G. Physicochemical Properties of Nucleoli in Live Cells Analyzed by Label-Free Optical Diffraction Tomography. Cells 2019, 8, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-K.; Lee, B.-W.; Fujii, F.; Kim, J.K.; Pack, C.-G. Physicochemical Properties of Nucleoli in Live Cells Analyzed by Label-Free Optical Diffraction Tomography. Cells 2019, 8, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H. V.; Pantanowitz, L.; Liu, Y. Quantitative Phase Imaging to Improve the Diagnostic Accuracy of Urine Cytology. Cancer Cytopathol 2016, 124, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calin, V.L.; Mihailescu, M.; Scarlat, E.I.; Baluta, A. V.; Calin, D.; Kovacs, E.; Savopol, T.; Moisescu, M.G. Evaluation of the Metastatic Potential of Malignant Cells by Image Processing of Digital Holographic Microscopy Data. FEBS Open Bio 2017, 7, 1527–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, B.; Carl, D.; Schnekenburger, J.; Bredebusch, I.; Schäfer, M.; Domschke, W.; von Bally, G. Investigation of Living Pancreas Tumor Cells by Digital Holographic Microscopy. J Biomed Opt 2006, 11, 034005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; An, H.; Park, S.; Moon, I. Automated Classification of Elliptical Cancer Cells with Stain-Free Holographic Imaging and Self-Supervised Learning. Opt Laser Technol 2024, 174, 110646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raub, C.B.; Nehmetallah, G. Holography, Machine Learning, and Cancer Cells. Cytometry Part A 2017, 91, 754–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paidi, S.K.; Shah, V.; Raj, P.; Glunde, K.; Pandey, R.; Barman, I. Coarse Raman and Optical Diffraction Tomographic Imaging Enable Label-Free Phenotyping of Isogenic Breast Cancer Cells of Varying Metastatic Potential. Biosens Bioelectron 2021, 175, 112863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, D.; Bak, T.; Ahn, D.; Kang, H.; Oh, S.; Min, H.; Lee, S.; Lee, J. Deep Learning-Based Label-Free Hematology Analysis Framework Using Optical Diffraction Tomography. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierzchalski, A.; Mittag, A.; Tárnok, A. Introduction A: Recent Advances in Cytometry Instrumentation, Probes, and Methods. In; 2011; pp. 1–21.

- Vasdekis, A.E.; Stephanopoulos, G. Review of Methods to Probe Single Cell Metabolism and Bioenergetics. Metab Eng 2015, 27, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.C.M.; Guck, J.; Goda, K.; Tsia, K.K. Toward Deep Biophysical Cytometry: Prospects and Challenges. Trends Biotechnol 2021, 39, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanska, M.; Muñoz, H.E.; Shaw Bagnall, J.; Otto, O.; Manalis, S.R.; Di Carlo, D.; Guck, J. A Comparison of Microfluidic Methods for High-Throughput Cell Deformability Measurements. Nat Methods 2020, 17, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, M.; Ivetich, S.D.; Aslan, M.K.; Aramesh, M.; Melkonyan, O.; Meng, Y.; Xu, R.; Colombo, M.; Weiss, T.; Balabanov, S.; et al. Real-Time Viscoelastic Deformability Cytometry: High-Throughput Mechanical Phenotyping of Liquid and Solid Biopsies. Sci Adv 2024, 10, eabj1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, H.; Zou, S.; Ma, Z.; Guo, W.; Fong, C.Y.; Khoo, B.L. A Deformability-Based Biochip for Precise Label-Free Stratification of Metastatic Subtypes Using Deep Learning. Microsyst Nanoeng 2023, 9, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Julian, T.; Ma, D.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Hosokawa, Y.; Yalikun, Y. A Review on Intelligent Impedance Cytometry Systems: Development, Applications and Advances. Anal Chim Acta 2023, 1269, 341424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Wang, C.; Liang, X.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Wu, J.J.; Su, T.; Li, J. Label-Free Sensing of Cell Viability Using a Low-Cost Impedance Cytometry Device. Micromachines (Basel) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahi, A.; Honrado, C.; Moore, J.; Adair, S.; Bauer, T.W.; Swami, N.S. Supervised Learning on Impedance Cytometry Data for Label-Free Biophysical Distinction of Pancreatic Cancer Cells versus Their Associated Fibroblasts under Gemcitabine Treatment. Biosens Bioelectron 2023, 231, 115262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokabi, M.; Rather, G.M.; Javanmard, M. Ionic Cell Microscopy: A New Modality for Visualizing Cells Using Microfluidic Impedance Cytometry and Generative Artificial Intelligence. Biosens Bioelectron X 2025, 24, 100619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuba-Surma, E.K.; Kucia, M.; Abdel-Latif, A.; Lillard, J.W.; Ratajczak, M.Z. The ImageStream System: A Key Step to a New Era in Imaging. Folia Histochem Cytobiol 2007, 45, 279–290. [Google Scholar]

- Dudaie, M.; Dotan, E.; Barnea, I.; Haifler, M.; Shaked, N.T. Detection of Bladder Cancer Cells Using Quantitative Interferometric Label-free Imaging Flow Cytometry. Cytometry Part A 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barteneva, N.S.; Fasler-Kan, E.; Vorobjev, I.A. Imaging Flow Cytometry. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry 2012, 60, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Chu, R.; Song, K.; Su, X. Single-Detector Dual-Modality Imaging Flow Cytometry for Label-Free Cell Analysis with Machine Learning. Opt Lasers Eng 2023, 168, 107665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.C.M.; Wang, M.; Cheah, K.S.E.; Chan, G.C.F.; So, H.K.H.; Wong, K.K.Y.; Tsia, K.K. Quantitative Phase Imaging Flow Cytometry for Ultra-Large-Scale Single-Cell Biophysical Phenotyping. Cytometry Part A 2019, 95, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudaie, M.; Dotan, E.; Barnea, I.; Haifler, M.; Shaked, N.T. Detection of Bladder Cancer Cells Using Quantitative Interferometric Label-Free Imaging Flow Cytometry. Cytometry Part A 2024, 105, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Yoon, S.E.; Song, Y.; Tian, C.; Baek, C.; Cho, H.; Kim, W.S.; Kim, S.J.; Cho, S.-Y. A Simple Approach to Biophysical Profiling of Blood Cells in Extranodal NK/T Cell Lymphoma Patients Using Deep Learning-Integrated Image Cytometry. BMEMat n/a. [CrossRef]

- Blasi, T.; Hennig, H.; Summers, H.D.; Theis, F.J.; Cerveira, J.; Patterson, J.O.; Davies, D.; Filby, A.; Carpenter, A.E.; Rees, P. Label-Free Cell Cycle Analysis for High-Throughput Imaging Flow Cytometry. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 10256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross Hallett, F. Scattering and Particle Sizing Applications*. In Encyclopedia of Spectroscopy and Spectrometry; Elsevier, 1999; pp. 2488–2494.

- Lin, M.; Liu, T.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, X. Dynamic Light Scattering Microscopy Sensing Mitochondria Dynamics for Label-Free Detection of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Enhanced by Deep Learning. Biomed Opt Express 2023, 14, 5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Li, J.; Gao, L.; Yang, D.; Kanaev, A. Dynamic Light Scattering: A Powerful Tool for In Situ Nanoparticle Sizing. Colloids and Interfaces 2023, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moleón Baca, J.A.; Ontiveros Ortega, A.; Aránega Jiménez, A.; Granados Principal, S. Cells Electric Charge Analyses Define Specific Properties for Cancer Cells Activity. Bioelectrochemistry 2022, 144, 108028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanyo, N.; Kovacs, K.D.; Saftics, A.; Szekacs, I.; Peter, B.; Santa-Maria, A.R.; Walter, F.R.; Dér, A.; Deli, M.A.; Horvath, R. Glycocalyx Regulates the Strength and Kinetics of Cancer Cell Adhesion Revealed by Biophysical Models Based on High Resolution Label-Free Optical Data. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 22422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akagi, T.; Kato, K.; Hanamura, N.; Kobayashi, M.; Ichiki, T. Evaluation of Desialylation Effect on Zeta Potential of Extracellular Vesicles Secreted from Human Prostate Cancer Cells by On-Chip Microcapillary Electrophoresis. Jpn J Appl Phys 2014, 53, 06JL01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael Pycraft Hughes The Cellular Zeta Potential: Cell Electrophysiology beyond the Membrane. Integrative Biology 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Avci, E.; Yilmaz, H.; Sahiner, N.; Tuna, B.G.; Cicekdal, M.B.; Eser, M.; Basak, K.; Altıntoprak, F.; Zengin, I.; Dogan, S.; et al. Label-Free Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy for Cancer Detection. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qian, X.; Beitler, J.J.; Chen, Z.G.; Khuri, F.R.; Lewis, M.M.; Shin, H.J.C.; Nie, S.; Shin, D.M. Detection of Circulating Tumor Cells in Human Peripheral Blood Using Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Nanoparticles. Cancer Res 2011, 71, 1526–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrini, L.; Alvarez-Puebla, R.A. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy in Cancer Diagnosis, Prognosis and Monitoring. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Li, Y.; Li, Z. Early Cancer Detection by SERS Spectroscopy and Machine Learning. Light Sci Appl 2023, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitesides, G.M. The Origins and the Future of Microfluidics. Nature 2006, 442, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgönüllü, S.; Bakhshpour, M.; Pişkin, A.K.; Denizli, A. Microfluidic Systems for Cancer Diagnosis and Applications. Micromachines (Basel) 2021, 12, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurkan, U.A.; Wood, D.K.; Carranza, D.; Herbertson, L.H.; Diamond, S.L.; Du, E.; Guha, S.; Di Paola, J.; Hines, P.C.; Papautsky, I.; et al. Next Generation Microfluidics: Fulfilling the Promise of Lab-on-a-Chip Technologies. Lab Chip 2024, 24, 1867–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.-C.; Anne, R.; Chawla, P.; Shaw, R.M.; He, S.; Rock, E.C.; Zhou, M.; Cheng, J.; Gong, Y.-N.; Chen, Y.-C. Deep Learning Unlocks Label-Free Viability Assessment of Cancer Spheroids in Microfluidics. Lab Chip 2024, 24, 3169–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Niu, J.; Pan, X.; Jin, H.; Lin, S.; Cui, D. Topology Optimization Based Deterministic Lateral Displacement Array Design for Cell Separation. J Chromatogr A 2022, 1679, 463384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, R.; Kumar, R. Trajectory Analysis of Circulating Tumor Cells through Contorted Deterministic Lateral Displacement Array for Unruptured Trapping: A Simulation Study. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering 2024, 46, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Di Carlo, D.; Lim, C.T.; Zhou, T.; Tian, G.; Tang, T.; Shen, A.Q.; Li, W.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; et al. Passive Microfluidic Devices for Cell Separation. Biotechnol Adv 2024, 71, 108317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-J.; Chang, C.-M.; Lu, Y.-T.; Liu, C.-H. Microfluidic Biochip for Target Tumor Cell and Cell-Cluster Sorting. Sens Actuators B Chem 2023, 394, 134369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, R.; Kirby, D.; Glynn, M.; Nwankire, C.; O’Sullivan, M.; Siegrist, J.; Kinahan, D.; Aguirre, G.; Kijanka, G.; Gorkin, R.A.; et al. Centrifugal Microfluidics for Cell Analysis. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2012, 16, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzhevskiy, A.S.; Razavi Bazaz, S.; Ding, L.; Kapitannikova, A.; Sayyadi, N.; Campbell, D.; Walsh, B.; Gillatt, D.; Ebrahimi Warkiani, M.; Zvyagin, A. V. Rapid and Label-Free Isolation of Tumour Cells from the Urine of Patients with Localised Prostate Cancer Using Inertial Microfluidics. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-C.; Tsai, J.-C.; Liu, Y.-Z.; Kuo, J.-N. Label-Free Cancer Cell Separation from Whole Blood on Centrifugal Microfluidic Platform Using Hydrodynamic Technique. Microfluid Nanofluidics 2024, 28, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkumur, E.; Shah, A.M.; Ciciliano, J.C.; Emmink, B.L.; Miyamoto, D.T.; Brachtel, E.; Yu, M.; Chen, P.; Morgan, B.; Trautwein, J.; et al. Inertial Focusing for Tumor Antigen–Dependent and –Independent Sorting of Rare Circulating Tumor Cells. Sci Transl Med 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee-de León, J.F.; Soto-García, B.; Aráiz-Hernández, D.; Delgado-Balderas, J.R.; Esparza, M.; Aguilar-Avelar, C.; Wong-Campos, J.D.; Chacón, F.; López-Hernández, J.Y.; González-Treviño, A.M.; et al. Characterization of a Novel Automated Microfiltration Device for the Efficient Isolation and Analysis of Circulating Tumor Cells from Clinical Blood Samples. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 7543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.-H.; Liu, R.; Ozkaya-Ahmadov, T.; Swain, B.E.; Boya, M.; El-Rayes, B.; Akce, M.; Bilen, M.A.; Kucuk, O.; Sarioglu, A.F. Negative Enrichment of Circulating Tumor Cells from Unmanipulated Whole Blood with a 3D Printed Device. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 20583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansor, M.A.; Jamrus, M.A.; Lok, C.K.; Ahmad, M.R.; Petrů, M.; Koloor, S.S.R. Microfluidic Device for Both Active and Passive Cell Separation Techniques: A Review. Sensors and Actuators Reports 2025, 9, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Bachman, H.; Ozcelik, A.; Huang, T.J. Acoustic Microfluidics. Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry 2020, 13, 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Ozcelik, A.; Rufo, J.; Wang, Z.; Fang, R.; Jun Huang, T. Acoustofluidic Separation of Cells and Particles. Microsyst Nanoeng 2019, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Mao, Z.; Peng, Z.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Y.; Huang, P.-H.; Truica, C.I.; Drabick, J.J.; El-Deiry, W.S.; Dao, M.; et al. Acoustic Separation of Circulating Tumor Cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 4970–4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustsson, P.; Magnusson, C.; Nordin, M.; Lilja, H.; Laurell, T. Microfluidic, Label-Free Enrichment of Prostate Cancer Cells in Blood Based on Acoustophoresis. Anal Chem 2012, 84, 7954–7962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antfolk, M.; Kim, S.H.; Koizumi, S.; Fujii, T.; Laurell, T. Label-Free Single-Cell Separation and Imaging of Cancer Cells Using an Integrated Microfluidic System. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 46507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, A.; Chen, S.; Lum, G.Z.; Zhang, X. A Perspective on Magnetic Microfluidics: Towards an Intelligent Future. Biomicrofluidics 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durmus, N.G.; Tekin, H.C.; Guven, S.; Sridhar, K.; Arslan Yildiz, A.; Calibasi, G.; Ghiran, I.; Davis, R.W.; Steinmetz, L.M.; Demirci, U. Magnetic Levitation of Single Cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Cheng, R.; Lim, S.H.; Miller, J.R.; Zhang, W.; Tang, W.; Xie, J.; Mao, L. Biocompatible and Label-Free Separation of Cancer Cells from Cell Culture Lines from White Blood Cells in Ferrofluids. Lab Chip 2017, 17, 2243–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kecili, S.; Yilmaz, E.; Ozcelik, O.S.; Anil-Inevi, M.; Gunyuz, Z.E.; Yalcin-Ozuysal, O.; Ozcivici, E.; Tekin, H.C. ΜDACS Platform: A Hybrid Microfluidic Platform Using Magnetic Levitation Technique and Integrating Magnetic, Gravitational, and Drag Forces for Density-Based Rare Cancer Cell Sorting. Biosens Bioelectron X 2023, 15, 100392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Yaman, S.; Patel, R.K.; Parappilly, M.S.; Walker, B.S.; Wong, M.H.; Durmus, N.G. Magnetic Levitation and Sorting of Neoplastic Circulating Cell Hybrids. 2022.

- Chan, J.Y.; Ahmad Kayani, A. Bin; Md Ali, M.A.; Kok, C.K.; Majlis, B.Y.; Hoe, S.L.L.; Marzuki, M.; Khoo, A.S.-B.; Ostrikov, K. (Ken); Rahman, Md.A.; et al. Dielectrophoresis-Based Microfluidic Platforms for Cancer Diagnostics. Biomicrofluidics 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwizera, E.A.; Sun, M.; White, A.M.; Li, J.; He, X. Methods of Generating Dielectrophoretic Force for Microfluidic Manipulation of Bioparticles. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2021, 7, 2043–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varmazyari, V.; Habibiyan, H.; Ghafoorifard, H.; Ebrahimi, M.; Ghafouri-Fard, S. A Dielectrophoresis-Based Microfluidic System Having Double-Sided Optimized 3D Electrodes for Label-Free Cancer Cell Separation with Preserving Cell Viability. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 12100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, H.T.; Ngo, N.A.; Nguyen, M.C.; Bui Thu, H.; Ducrée, J.; Chu Duc, T.; Bui, T.T.; Do Quang, L. Numerical Study on a Facing Electrode Configuration Dielectrophoresis Microfluidic System for Efficient Biological Cell Separation. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 27627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, M.; Ren, Z.; Cheng, C.; Li, G.; Yang, F. Small Extracellular Vesicles Detection Using Dielectrophoresis-Based Microfluidic Chip for Diagnosis of Breast Cancer. Biosens Bioelectron 2024, 259, 116382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, N.E.; Raj, A.; Young, K.M.; DeLuca, A.P.; Chrit, F.E.; Tucker, B.A.; Alexeev, A.; McDonald, J.; Benigno, B.B.; Sulchek, T. Label-Free Microfluidic Enrichment of Cancer Cells from Non-Cancer Cells in Ascites. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 18032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, P.; Rahman, Z.; ten Dijke, P.; Boukany, P.E. Microfluidics Meets 3D Cancer Cell Migration. Trends Cancer 2022, 8, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.; Yin, T.-I.; Reyes, D.; Urban, G.A. Microfluidic Chip with Integrated Electrical Cell-Impedance Sensing for Monitoring Single Cancer Cell Migration in Three-Dimensional Matrixes. Anal Chem 2013, 85, 11068–11076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinisch, J.J.; Lipke, P.N.; Beaussart, A.; Chatel, S.E.K.; Dupres, V.; Alsteens, D.; Dufrêne, Y.F. Atomic Force Microscopy–Looking at Mechanosensors on the Cell Surface. J Cell Sci 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalwa, H. Singh.; Webster, T.J. Cancer Nanotechnology : Nanomaterials for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Payton, O.D.; Picco, L.; Scott, T.B. High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy for Materials Science. International Materials Reviews 2016, 61, 473–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemła, J.; Danilkiewicz, J.; Orzechowska, B.; Pabijan, J.; Seweryn, S.; Lekka, M. Atomic Force Microscopy as a Tool for Assessing the Cellular Elasticity and Adhesiveness to Identify Cancer Cells and Tissues. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2018, 73, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, L.; Xi, N.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Z.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, W. Atomic Force Microscopy Imaging and Mechanical Properties Measurement of Red Blood Cells and Aggressive Cancer Cells. Sci China Life Sci 2012, 55, 968–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Mezencev, R.; Kim, B.; Wang, L.; McDonald, J.; Sulchek, T. Cell Stiffness Is a Biomarker of the Metastatic Potential of Ovarian Cancer Cells. PLoS One 2012, 7, e46609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najera, J.; Rosenberger, M.R.; Datta, M. Atomic Force Microscopy Methods to Measure Tumor Mechanical Properties. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xi, N.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L. Atomic Force Microscopy for Revealing Micro/Nanoscale Mechanics in Tumor Metastasis: From Single Cells to Microenvironmental Cues. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2021, 42, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J.R.; Pabijan, J.; Garcia, R.; Lekka, M. The Softening of Human Bladder Cancer Cells Happens at an Early Stage of the Malignancy Process. Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology 2014, 5, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzado-Martín, A.; Encinar, M.; Tamayo, J.; Calleja, M.; San Paulo, A. Effect of Actin Organization on the Stiffness of Living Breast Cancer Cells Revealed by Peak-Force Modulation Atomic Force Microscopy. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 3365–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haeri, Z.; Shokoufi, M.; Jenab, M.; Janzen, R.; Golnaraghi, F. Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy for Breast Cancer Diagnosis: Clinical Study. Integr Cancer Sci Ther 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojarand, J.; Min, M.; Koel, A. Multichannel Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy Analyzer with Microfluidic Sensors. Sensors 2019, 19, 1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscaglia, L.A.; Oliveira, O.N.; Carmo, J.P. Roadmap for Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy for Sensing: A Tutorial. IEEE Sens J 2021, 21, 22246–22257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.; Yang, L.; Frazier, A.B. Quantification of the Heterogeneity in Breast Cancer Cell Lines Using Whole-Cell Impedance Spectroscopy. Clinical Cancer Research 2007, 13, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younghak Cho; Hyun Soo Kim; Frazier, A. B.; Chen, Z.G.; Dong Moon Shin; Han, A. Whole-Cell Impedance Analysis for Highly and Poorly Metastatic Cancer Cells. Journal of Microelectromechanical Systems 2009, 18, 808–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowell, L.; Yakisich, J.; Aufderheide, B.; Adams, T. Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy for Monitoring Chemoresistance of Cancer Cells. Micromachines (Basel) 2020, 11, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalina, T. Reproducibility of Flow Cytometry Through Standardization: Opportunities and Challenges. Cytometry Part A 2020, 97, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillay, T.S.; Topcu, D.İ.; Yenice, S. Harnessing AI for Enhanced Evidence-Based Laboratory Medicine (EBLM). Clinica Chimica Acta 2025, 569, 120181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Guo, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, C.; Bu, J.; Sun, T.; Wei, J. Liquid Biopsy in Cancer: Current Status, Challenges and Future Prospects. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).