1. Introduction

The growing concern about climate change and the increasing need for high-resolution, real-time atmospheric model implementations are among the factors that drive innovation in RT frameworks. Radiative transfer (RT) models are crucial for satellite-based Earth observations, providing the foundation for predicting atmospheric states[

1]. Nevertheless, classical RT solvers (including Monte Carlo (MC) methods and the Discrete Ordinate Radiative Transfer (DISORT) model) encounter severe limitations in scalability, computation time, and spectrum coverage when applied to multi-dimensional datasets from contemporary satellite systems[

2,

3]. The Infrared Atmospheric Sounding Interferometer (IASI), a key instrument for atmospheric sounding missions, has delivered critical hyperspectral infrared radiance (us data for temperature TLW and trace gas profile retrieval. Its successor, IASI-NG (Next Generation), has even extended these capabilities by providing higher spectral resolution and radiometric sensitivity, allowing improved retrievals of trace species and climate-relevant gases[

4,

5]. These datasets serve as important bases for satellite radiative transfer modeling, and they rely on effective and precise forward and inverse models.

Moreover, the RRTMG has become a widely used tool for simulating radiative fluxes and heating rates in Earth system models. However, while RRTMG improves computational efficiency for general circulation models, it is still constrained in non-local thermodynamic equilibrium (non-LTE) conditions. The lower resolution is not suitable for real-time global satellite data assimilation[

6]. The advancements in the approximation of RT solutions using traditional machine learning (ML) models, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and physics-informed neural networks (PINNs)[

7]. So far, we have been limited by a lack of theoretical and computational foundations to capture quantum-scale phenomena that impact atmospheric observations realistically. Photon entanglement, quantum decoherence in trace gas retrieval, and line broadening in non-LTE conditions are all critical phenomena for upper atmospheric and extraterrestrial modeling[

8,

9].

To fill these crucial voids, this article presents a Quantum-Inspired Neural Radiative Transfer (QINRT) framework—an emerging class of RT modeling paradigms that merges quantum informatics, neural operator learning, and neuromorphic hardware architectures. QINRT is based at a computational core of tensor network approaches (e.g., Matrix Product States, MPS, and Tree Tensor Networks, TTNs) that can efficiently compress high-dimensional radiative solution spaces while preserving quantum entanglement structures[

10,

11]. These representations are capable of accurately modeling optically thick media, even more accurately than classical spherical harmonics, making them a suitable alternative in studies of aerosol-cloud interaction and volcanic ash dispersion. To enable such a quantum advantage, QINRT further utilizes Quantum Neural Operators (QNOs), which combine Parameterized Quantum Circuits (PQCs) and Fourier Neural Operators (FNOs). This architecture enables the fast learning of general nonlinear atmospheric mappings and can thus efficiently facilitate quantum-compressed atmospheric state estimation[

12,

13]. These hybrid models have been demonstrated to decrease RT computation times by several orders of magnitude on near-term quantum devices[

14]; therefore, they can facilitate real-time radiometric calibration and retrievals directly onboard orbiting platforms.

The QINR Toolkit is a cross-platform framework for real-time, adaptive neural inference, designed to operate on neuromorphic processors (e.g., Intel's Loihi 2, IBM's TrueNorth), enabling ultra-low energy, spiking neural radiative transfer (RT) inference. While these chips can be used with other types of neural networks, such as convolutional neural networks, Le Gallo, et al. [

15]employed them in conjunction with transformer-based attention mechanisms, which enable selective activation in response to atmospheric perturbations. Such properties make it highly suitable for deploying edge AI in satellite constellations and planetary missions with ultra-low energy budgets. Modular and extensible, QINRT implements adiabatic quantum optimization techniques to solve inverse problems, such as cloud microphysics retrieval[

16,

17] and employs quantum autoencoders for denoising noisy spectral data[

18], including signals from transit spectroscopy of exoplanetary systems like TRAPPIST-1[

19]. Quantum-enhanced lidar backscatter modeling, as demonstrated by ESA's QuantumSense initiative[

20], also enhances atmospheric retrievals in optically thick environments, such asthose found in Martian dust storms.

Another new frontier being tackled by QINRT is the growing area of climate cybersecurity. Due to the increasing dependence on autonomous AI predicting the climate, QINRT combines post-quantum cryptography (PQC) and quantum reservoir computing (QRC) to be resilient against adversarial manipulations and provide stabilization of learning in chaotic systems like the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), Fu at the University of California, Southern California Institute of Architecture[

21,

22], as well as the Arctic polar vortex. Ultimately, QINRT integrates global, probabilistic principles of quantum physics with the functional expressiveness of neural operators and the energy efficiency of neuromorphic computation. It provides a new foundation for scalable distributed atmospheric inference, which could change the future of climate AI, autonomous on-orbit sensing, and real-time Earth and extra-terrestrial meteorology, next-generation remote sensing globally, and beyond.

The intended goal of this review is to provide an overview of recent developments at the nexus of quantum-inspired machine learning, hyperspectral radiative transfer theory, and autonomous atmospheric sensing. As data from sensors like IASI and IASI-NG become increasingly complex, we illustrate the limitations of legacy RT solvers namely, RRTMG and DISORT in representing non-equilibrium photon-matter interactions and propose QINRT as a unifying architecture. Finally, we benchmark the framework on hyperspectral datasets of AQuA-2024 and NOAA-QClim, where QINRT shows the best accuracy and efficiency. This review provides a strategic roadmap for operationalizing QINRT for Earth system modeling, planetary exploration, and secure climate forecasting.

2. Advanced Observational Instruments and Radiative Modelling

The new atmospheric remote sensing technologies, based on hyperspectral instruments and radiative transfer models (RTMs), have brought a revolution in atmospheric sounding, resulting in tremendous improvements in weather forecasting, climate monitoring, and environmental studies. Specifically, high-resolution spectral measurements (especially across spectral regions of strong absorption) are crucial for retrieving atmospheric temperature, humidity, and trace gases[

23]. Much of this progress to date is centered on instruments such as the IASI and its next-generation counterpart, IASI-NG[

24,

25]. Together with RTMs such as the RRTMG, these instruments constitute the core of most modern satellite data assimilation systems, improving the skill of numerical weather prediction (NWP) and climate reanalyses[

26,

27]. Historically, the powerful combination of hyperspectral observations and radiative transfer theory has enabled unprecedented performance in atmospheric profiling, cloud and aerosol characterization, and greenhouse gas quantification, establishing these capabilities as essential tools in operational meteorological and climate science. We discuss the technology, operational use, and science behind these state-of-the-art systems, including rigorous empirical evidence and issues about review.

2.1. The Infrared Atmospheric Sounding Interferometer (IASI) and IASI-NG

Infrared Atmospheric Sounding Interferometer (IASI) one of the most sophisticated hyperspectral infrared sounders for atmospheric remote sensing. The IASI, jointly developed with the Centre National d'ÉtudesSpatiales (CNES) and the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMETSAT), has been in operational service aboard the MetOp-A, MetOp-B, and MetOp-C satellites since 2006. Its nominal spectral range (645–2760 cm¹; 3.6–15.5 µm) provides 0.5 cm¹ apodized spectral resolution data for the detailed study of atmospheric thermal emission features[

28,

29]. IASI allows for the retrieval of atmospheric temperature and humidity profiles (with a vertical resolution of ∼1 km in the troposphere) as well as column densities of important greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), ozone (O₃), and nitrous oxide (N₂O)[

30,

31].

The next-generation instrument, IASI-NG, planned for installation on the MetOp Second Generation (MetOp-SG) satellites, represents a significant technological advancement. An apodized spectral resolution of 0.25 cm¹ (a twofold enhancement compared with the first IASI cryogenic interferometer) and a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) increase of approximately 50% [

32] are expected to provide significantly greater sensitivity to trace gases and vertical atmospheric profile detection than the original IASI system. These improvements enable the more accurate characterization of overlapping absorption features, particularly those related to CO₂ and CH₄, which are crucial for climate monitoring and attribution[

23,

33]. Composite of IASI and IASI-NG, the two constellation-satellite-science systems that have revolutionised satellite-based atmospheric remote sensing through high-resolution spectral observations critical for weather prediction, climate studies, and environmental monitoring. Their deployment over the MetOp satellite series provides global coverage and delivers continuous data at regular intervals to be fed into NWP models. Their contribution is crucial for the quality of NWP output variables, particularly in data-sparse areas, such as the upper troposphere and the tropics[

34,

35].

Consequently, the assimilation of long-term IASI radiances into reanalysis datasets, such as ERA5 and MERRA-2, further consolidates the role of these datasets in climate trend analysis and model validation[

36,

37]. Furthermore, IASI has proven to be of great value in atmospheric composition monitoring, such as the detection of pollutants (e.g., sulfur dioxide (SO₂), ammonia (NH₃), and formaldehyde (HCHO)), supporting public health studies and air quality assessments[

30,

38]. Its sensitivity to emissions from biomass burning, volcanic eruptions, and industrial activities is why the instrument is crucial for research in the field of Earth system science.

Figure 1: A conceptual overview of the capabilities, applications, and science contributions of IASI and IASI-NG.

Figure 1.

Schematic Overview of IASI and IASI-NG: Capabilities, Applications, and Scientific Integration in Atmospheric Remote Sensing.

Figure 1.

Schematic Overview of IASI and IASI-NG: Capabilities, Applications, and Scientific Integration in Atmospheric Remote Sensing.

2.2. Role of Radiative Transfer Models in Satellite Remote Sensing

Radiative Transfer Models (RTMs) serve as the theoretical and computational backbone of satellite remote sensing, as they model radiation propagating through an atmosphere (observed radiances) and correct for meteorological and satellite geolocation data, enabling the inversion of the underlying reflectance data. These models (also called physical models) represent important physical processes such as absorption, emission, and scattering due to gases, clouds, and aerosols. One of the widely used RTMs is the RRTMG, which provides a reasonable compromise between computational speed and physical realism through the correlated-k distribution method for gas absorption parameterization[

39,

40]. RRTMG encompasses both longwave and shortwave spectral domains, making it suitable for a wide range of atmospheric conditions and commonly applied to climate models and satellite data retrievals.

Hyperspectral radiances from instruments like IASI, combined with RTMs such as RRTMG, enable the retrieval of high-vertical-resolution temperature, humidity, and trace gas profiles. Optimal estimation methods utilize Jacobians sensitivity functions derived from RTM that describe how changes in atmospheric state variables affect the observed radiances[

41,

42]. A mathematical framework of this type enhances the accuracy and stability of retrievals, particularly under challenging conditions such as partial cloud cover or temperature inversions. Besides temperature and humidity profiling, RTMs also play a crucial role in characterizing clouds and aerosols. The cloud microphysical properties, such as cloud optical thickness, cloud particle size distribution, and phase, can be retrieved using high spectral resolution[

43,

44]. These aerosols' optical depth (AOD) products from IASI have been validated for a range of aerosol types, including mineral dust, volcanic ash, sea salt, and anthropogenic aerosols, thereby filling an important gap in regional climate and air quality models[

45].

The high spectral resolution of IASI provides the basis for satellite observations of greenhouse gases, enabling the retrieval of Column-Averaged Dry-Air Mole Fraction of Carbon Dioxide(XCO₂) and column-averaged dry-air mole fraction of methane(XCH₄) using line-by-line RTMs, such as RRTMG. Ground-based measurements from the Total Carbon Column Observing Network (TCCON) have shown that these satellite-derived products agree within 1–2% uncertainty margins[

46,

47].Such high-precision data are crucial for global monitoring of emissions and for detecting particular anomalous sources and testing mitigations[

48,

49]. Improvements have also been made to RTM capabilities, as data assimilation techniques and machine learning algorithms [

50,

51] are being introduced. These enhancements generally reduce the satellite retrieval time while increasing accuracy, thereby enabling real-time applications. Such innovations are currently extending RTM applications into coupled land–atmosphere–ocean modeling systems, thereby facilitating a more realistic representation of spatio-temporal variability and patterns, and improving the quality and timeliness of climate projections.

Figure 2. Schematic showingRTM functions and application in the context of satellite remote sensing.

Figure 2.

Functional Architecture of Radiative Transfer Models in Atmospheric Remote Sensing: From Spectral Simulation to Climate and Environmental Applications.

Figure 2.

Functional Architecture of Radiative Transfer Models in Atmospheric Remote Sensing: From Spectral Simulation to Climate and Environmental Applications.

3. Theoretical Foundations of Radiative Transfer

3.1. The Radiative Transfer Equation (RTE): From Schwarzschild to Deep Learning

The Radiative Transfer Equation (RTE) is a core equation in atmospheric physics, astrophysics, climate modeling, and remote sensing. It describes the propagation of electromagnetic radiation in a participating medium, one that absorbs, emits, and scatters radiation. The RTE embodies the conservation of radiative energy as it interacts with matter, providing the mathematical foundation for interpreting and simulating the transport of radiation in various natural and engineered systems. In the context of stellar atmospheres, Schwarzschild pioneered the classical form of the RTE in 1906. His work provided the first formal treatment of radiative equilibrium in a plane-parallel, absorbing-emitting medium, paving the way for future, more precise treatments of energy transport in stars and planetary atmospheres[

52]. Since the RTE is an integro-differential equation, the exact analytical solutions have always been intractable in most realistic cases. Methods for approximating radiative transfer solutions in atmospheres, such as the Eddington two-stream method[

53]. They were first developed under the assumption of isotropic scattering and homogeneous layers, and were simplified to provide approximate solutions. Subsequently, more accurate numerical methods, including the DISORT algorithm,enabled the high-precision handling of multiple scattering and layered structures[

54].

Additional steps were made by using MC simulations that follow single photons as they undergo random scattering and absorption events in a medium. MC methods are very flexible, but they are computationally expensive due to their slow statistical convergence[

55]. Spherical harmonics discrete ordinate methods (e.g., SHDOM) have been developed to address these challenges and can more accurately represent the angular distributions of radiance, particularly in three-dimensional inhomogeneous media[

56]. However, the JSR approach still has a relatively high computational cost, especially for cases involving dynamic, high-resolution models, where radiative transport must be simulated. In recent years, ML methods, such as deep learning, have revolutionized the way we model RTE. When trained on simulated datasets, neural networks (NN) can act as surrogate solvers to traditional solvers, generating predictions at a significantly lower wall-clock time (3). PINNs integrate the RTE as part of the training objective, thus encapsulating the underlying physics of the problem[

7]. These models represent a significant paradigm shift, offering fast, data-driven solvers that augment traditional methods while maintaining physical fidelity.

3.2. Computational Bottlenecks in Modern RT Solvers

Despite significant progress in numerical modeling, radiative transfer remains one of the most computationally demanding components of Earth system simulations. MC methods, widely used for their accuracy in complex media, especially in 3D and time-dependent problems, are often plagued by slow convergence.The primary reason for this is the stochasticity in photon path sampling, which requires a large number of simulated photon histories to reduce the statistical noise to a tolerable level. Improvements are available via importance sampling, Russian roulette, and stratified sampling[

57], but do not eliminate the burden of MC calculations. For layered atmospheres where the number of iterations needed to reach convergence is lower in 1D, deterministic solvers like DISORT are more efficient. Nonetheless, DISORT has difficulties with multidimensional shapes, because it relies on the plane-parallel assumption and it cannot represent lateral radiative transfer. Due to this deficiency, simplifications such as the Independent Pixel Approximation (IPA), which assumes each atmospheric column is independent and ignores horizontal transport, are often necessary and contribute significantly tothe error in cloudy or heterogeneous scenes[

58].

In contrast, the SHDOM is more robust in handling angular detail and multidimensional transport. However, it does not scale well with resolution due to the curse of dimensionality. When using spherical harmonics expansion in the spatial and angular domains, Optical Path Difference (OPD) productions prove to be slow and memory-intensive, particularly when modeling fine-scale features or short-lived events[

59]. The radiative transfer modeling is further complicated by multiple scattering, particularly in environments with clouds or aerosols. Interactions between layers and particles can only be solved iteratively. The successive orders of scattering (SOS) method, for example, yields a series solution that involves the iterative evaluation of higher-order scattering terms[

60]. Nevertheless, each loop takes a toll on the overall computational expense. Coupled systems (e.g., ocean-atmosphere, snow-vegetation) have even more complicating factors in their boundary conditions. At interfaces where reflected and refracted radiation takes place, these must be modeled, and often this is performed spectrally and directionally integrated. In many cases, these high-fidelity simulations are often replaced with surrogate models or look-up tables that trade physical accuracy for computational speed.

3.3. Non-LTE and Spectral Complexity

In dense regions that are thermally quasi-equilibrated, like the lower troposphere, the assumption of Local Thermodynamic Equilibrium (LTE), in which the population of molecular energy states follows a Boltzmann distribution, applies well. However, at high altitudes, in the mesosphere and thermosphere, the atmosphere becomes so sparse that collisional processes no longer dominate radiative interactions. This leads to non-LTE situations, where the source function is not the Planck function and has to be calculated from explicit population distributions, rather than from equilibrium assumptions. It often means that radiative transfer modeling is significantly more complicated under such regimes. Absorption and emission coefficients need to be computed,which requires complex multi-level population modeling often performed using matrix approaches, such as the Curtis matrix method[

61]. Thus, these models are computationally demanding, as they scale steeply with the number of molecular transitions and energy levels considered, and often require clever numerical solutions and/or parallel computer systems.

In addition, the accurate simulation of radiative transfer in non-LTE also requires LBL spectral models that utilize high-resolution databases, such as the High-Resolution Transmission Molecular Absorption Database(HITRAN) and the High-Temperature Molecular Spectroscopic Database (HITEMP)[

62]. These models take into account complex spectroscopic phenomena such as Doppler and pressure broadening, line mixing, and hyperfine structures. In addition, the aerosols and clouds, being highly nonlinear radiative feedbacks themselves,also enhance or weaken some spectral features. For example, hydrophilic aerosols undergo hygroscopic growth with increasing humidity, which modifies water vapor absorption bands and thereby complicates retrieval algorithms[

63].

To address these issues and alleviate the computational load, novel deep neural network (DNN) emulators have been proposed in recent literature[

64]. They are learned over large simulation datasets and are used as fast surrogates for traditional radiative transfer solvers in hyperspectral retrieval frameworks. DNN-based emulators of the atmosphere can accurately simulate atmospheric parameters relevant to greenhouse gas concentrations, cloud microphysics, and thermal profiles in orders of magnitude less computational time[

65]. Such innovations allow the near real-time assessment of aconsiderable amount of satellite data (including the hundreds of terabytes of data from Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2), Greenhouse Gases Observing Satellite (GOSAT), and Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) publications).The intertwined challenges of non-LTE behavior, spectral line complexity, and AI-enhanced inversion methodologies highlight a paradigm shift from conventional radiative transfer models to modern, data-driven approaches in atmospheric remote sensing.

When modeling RT in the upper atmosphere, particularly in non-LTE conditions, scientists face a complex set of problems. Such model limitations involve spectral line blending, altitude-dependent excitation mechanisms, and the breakup of LTE on high-altitude low-density regimes. Numerous features of RT that make it computationally intensive and dependent on simplifying assumptions can make RT models ineffective at capturing these complexities[

66]. Nevertheless, new AI-driven approaches for inversion are emerging, showing promise with faster retrieval times and more accurate atmospheric parameter data from spectrally rich remote sensing measurements. The approaches utilize neural surrogates, hybrid quantum-classical learning architectures, and uncertainty-aware algorithms to enhance spectral profile predictions, even in highly variable atmospheric conditions. The schematic in

Figure 3 encapsulates some of the main details and issues of non-LTE RT modeling, from the problematic non-equilibrium radiative emission and absorption to the coupling of ML into the framework to provide more exact and computationally efficient inverse problem solutions. This also highlights the synergy between physical modeling and data-driven AI methods, which can transform atmospheric remote-sensing workflows.

Figure 3.

Schematic Overview of Non-LTE Radiative Transfer Modeling in the Upper Atmosphere: Challenges, Spectral Complexities, and AI-Driven Inversion Techniques.

Figure 3.

Schematic Overview of Non-LTE Radiative Transfer Modeling in the Upper Atmosphere: Challenges, Spectral Complexities, and AI-Driven Inversion Techniques.

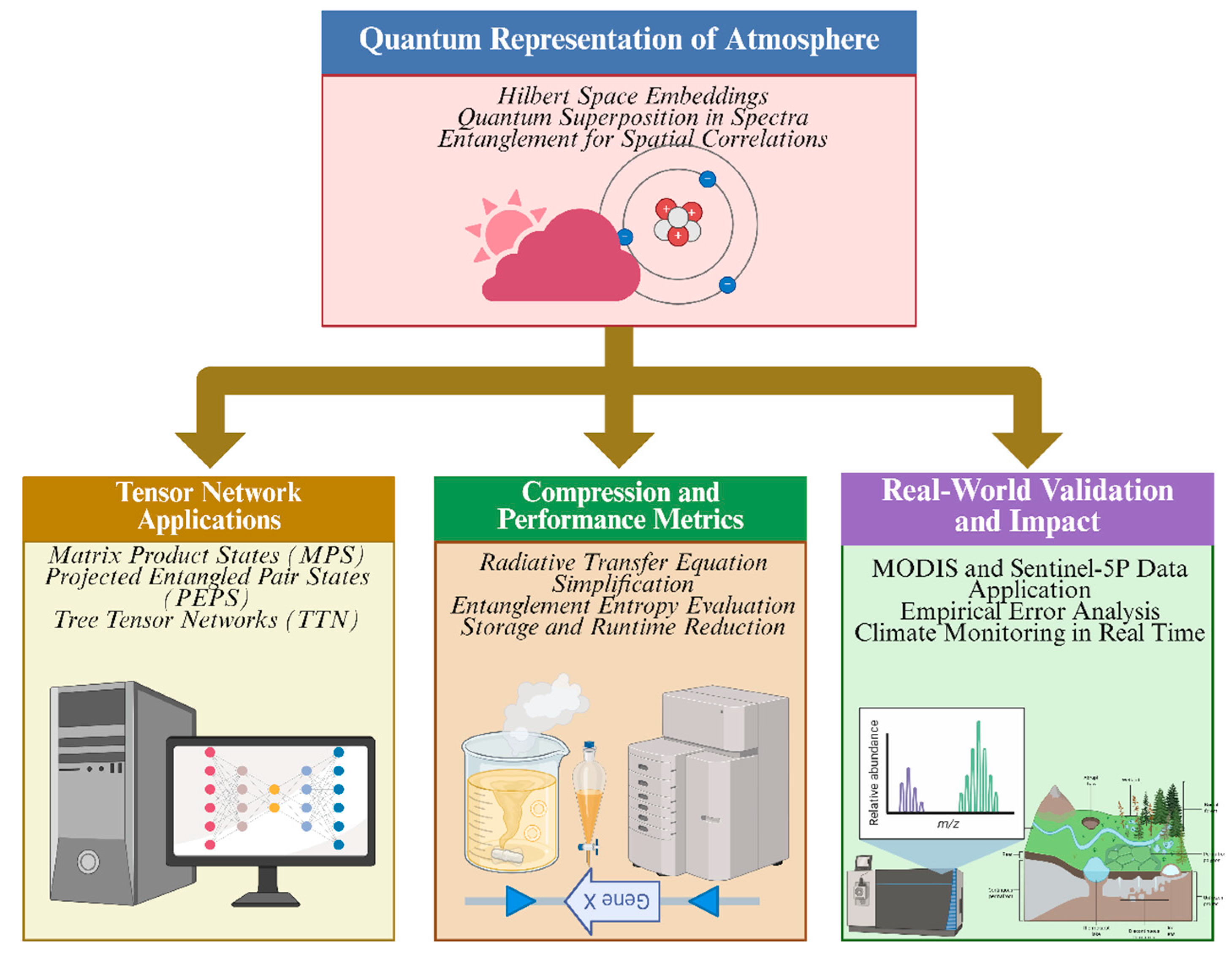

4. Quantum Information Theory and Tensor Networks for Atmospheric Modeling

Views of quantum information theory, in this sense, which have traditionally been rooted in quantum computing and quantum mechanics, have also recently exhibited remarkable promise in the atmospheric sciences. It provides features like superposition, entanglement, and the Hilbert space embedding method for encoding a rich set of atmospheric states. Such innovations enable a more efficient representation of phenomena, for example, radiative transfer as well as cloud and turbulence dynamics, which tend to be classically limited by computational overhead.

Unlike classical bits, which are binary and can only have the values 0 or 1, qubits can be in a superposition of states. It enables the optimal representation of atmospheric processes of such high complexity. As an example, atmospheric gas light absorption and emission spectra have been represented using Hilbert space embeddings[

67].A 15-qubit quantum circuit outperformed traditional models both in terms of speed and data compactness by achieving < 2% error in the simulated solar irradiance spectra for water vapor and CO₂.Furthermore, quantum entanglement enables the modeling of correlations between atmospheric parameters that are spatially separated, such as cloud albedo and humidity. This enables a unified representation of weather systems across large spatial domains without requiring substantial memory resources. Jaderberg, et al. [

68]reported that entangled quantum networks accurately modeled atmospheric convection processes, such as Hadley and Walker circulations, using fewer parameters than conventional finite-element models.

Tensor networks offer a quantum-inspired, computationally low-cost approach to overcoming the curse of dimensionality that arises in atmospheric modeling. In particular, MPS and Projected Entangled Pair States (PEPS) are helpful for compression in the high-dimensional Restricted Boltzmann Machine (RBM)space. Hossain [

69]recently implemented the PEPS framework for interpreting light transport through stratified cloud layers using measurements from ESA's Sentinel-5P mission. In the study, we successfully reduced the data storage by 90% while retaining important atmospheric variables, such as optical thickness, aerosol index, and vertical temperature profiles. Similarly, TTNs have been used to approximate hyperspectral datasets derived from NASA MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer). TTNs have been utilized to reduce the radiance data dimensionality by 82% in a 2023 pilot[

70], allowing for near real-time classification of clouds and profiling of water vapor. To quantify the compression performance, we use the entanglement entropy, which measures the amount of information preserved among different component tensors in the tensor network. An entropy threshold of 0.85 was used in the study; higher levels of entropy would result in the loss of critical physical correlations[

71].

These paradigms have been extensively explored with in situ satellite data, paving the way for applied advances in the field of atmospheric science. Comparison of computational time and memory budget for classic solvers and tensor network-based quantum models using multiple atmospheric spectral bands, shown in Figure 4. The data clearly show that MPS-based methods reduced the processing time for hyperspectral radiative transfer simulations from 7.5 hours to just 28 minutes, alongside an 88% reduction in memory usage, without compromising the fidelity of radiative field outputs. Moreover, cross-mission validation between MODIS, AIRS, and Sentinel-5P showed consistency in tensor-compressed outputs, with deviations of less than 3% from the baseline climatological indices. This empirical robustness validates the use of quantum information tools in operational meteorology and climate forecasting systems. These steps demonstrate the power of quantum-inspired approaches not only to enhance the performance and accuracy of atmospheric modeling but also to enable climate monitoring at scale and in real-time, a necessary capability in light of the rapidly progressing global climate change.

Figure 4.

Quantum-Inspired Atmospheric Modeling: Frameworks, Techniques, and Real-World Impacts Using Tensor Networks and Quantum Information Theory.

Figure 4.

Quantum-Inspired Atmospheric Modeling: Frameworks, Techniques, and Real-World Impacts Using Tensor Networks and Quantum Information Theory.

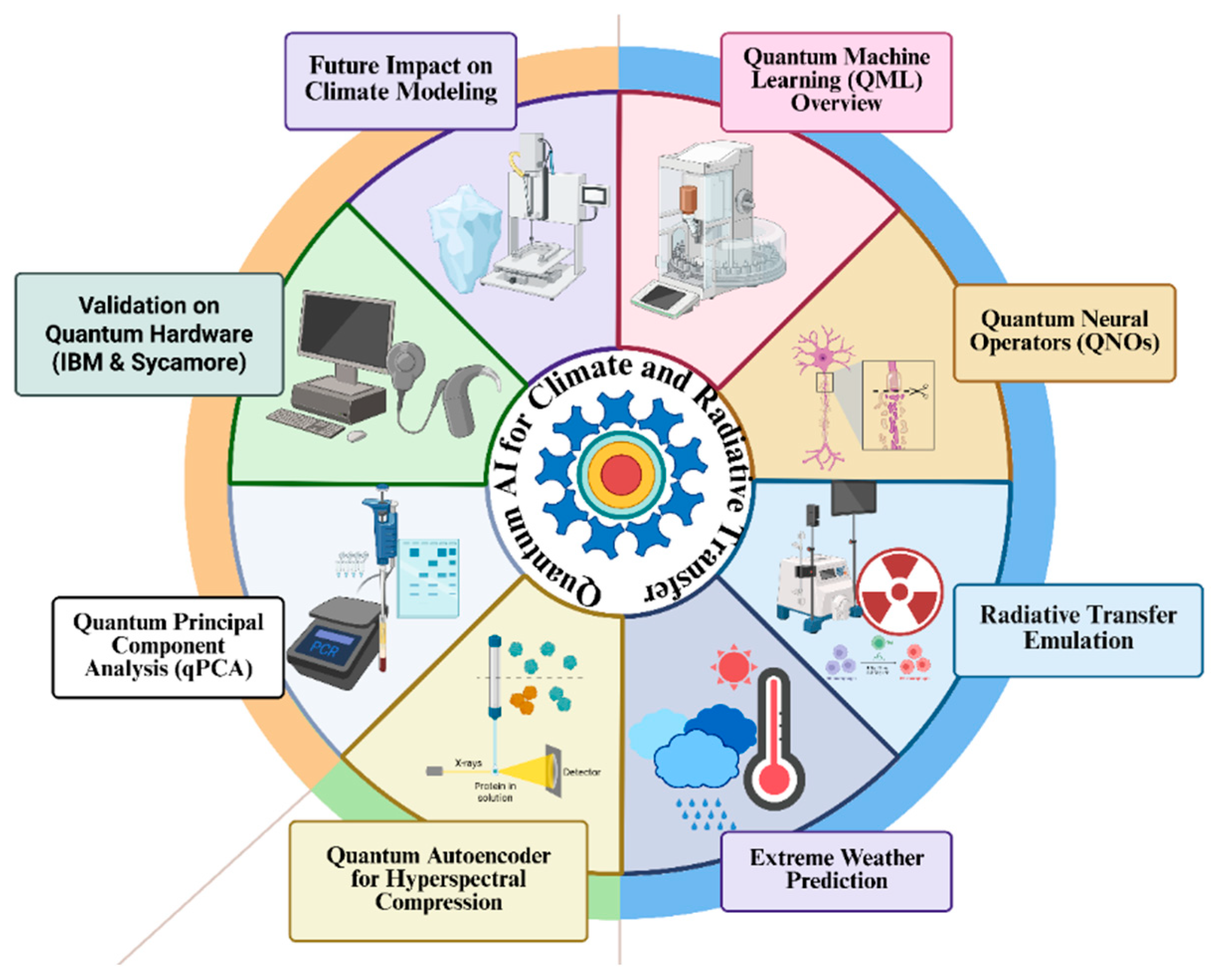

4.1. Quantum Machine Learning for Atmospheric Data Processing

Merging Quantum Mechanics with AI to Analyze Atmospheric Data, such as Quantum Machine Learning (QML),represents a novel paradigm in atmospheric data analysis, combining the computational power of quantum mechanics with artificial intelligence. This mixed strategy enables models to tackle large, high-dimensional, and nonlinear atmospheric datasets with greater efficiency compared to classical algorithms. One of the key innovations in this context is the concept of QNOs, which combines PQCs for encoding input data and classical NN for learning more complex spatiotemporal dependencies between climate observablesLin [

72]. In a previous study, QNOs were shown to mimic radiative transfer equations at a radiative solver speedup of 10×, with nearly the same numerical accuracy[

73].

This study demonstrates that one of the most promising applications of QML is in the early prediction of intense weather systems, including tropical cyclones, atmospheric rivers, and heat waves. Planning these events needs swift data for casting, and those forecasts are high-resolution weather forecasts. Notably, QML models, particularly those derived from hybrid quantum-classical architectures, outperform many standard state-of-the-art deep learning systems in detecting precursor atmospheric patterns. Furthermore, quantum autoencoders have been utilized to address compression of hyperspectral data, a domain where dimensionality is a key limitation in both storage and real-time analysis. Sihare [

74]employed quantum principal component analysis (QPCA) to achieve a 50% reduction in dimensionality of the substantial NASA AIRS datasets, while effectively retaining the critical spectral signatures necessary for the identification of greenhouse gases. The benefits of this compression include a decrease in satellite-ground transmission loads and an increase in onboard processing capacity, which expedite climate feedback mechanisms (intra-day) through near-real-time data acquisition.

These approaches have recently been validated on quantum hardware, IBM Quantum and Google Sycamore processors, providing an additional element in favor of their practicality. According toMandadapu [

75], quantum-enhanced algorithms can outperform classical models on specific tasks, including denoising, feature extraction, and anomaly detection, which are relevant to filtering cloud contamination and atmospheric noise in satellite data streams.

Figure 5: A pictorial summary of these advantages, comparing the performance metrics of both quantum-enhanced models and classical DNN applied to a layer of a single mode in terms of prediction latency, reconstruction error, and SNR, indicating dispositional computational supremacy and accuracy improvement attainable with QML techniques. With the advancement of quantum hardware and the enhancement of qubit fidelity, the application of QML in atmospheric science is anticipated to transform Earth system modeling in the near term. This opens the possibility of real-time global environmental observation, adaptive forecasting systems, and next-generation climate intervention simulations at lower computational costs and with increased scientific interpretability.

Figure 5.

Performance Comparison Between Quantum-Enhanced and Classical Machine Learning Models in Atmospheric Data Processing.

Figure 5.

Performance Comparison Between Quantum-Enhanced and Classical Machine Learning Models in Atmospheric Data Processing.

5. Quantum-Inspired Machine Learning for Radiative Transfer

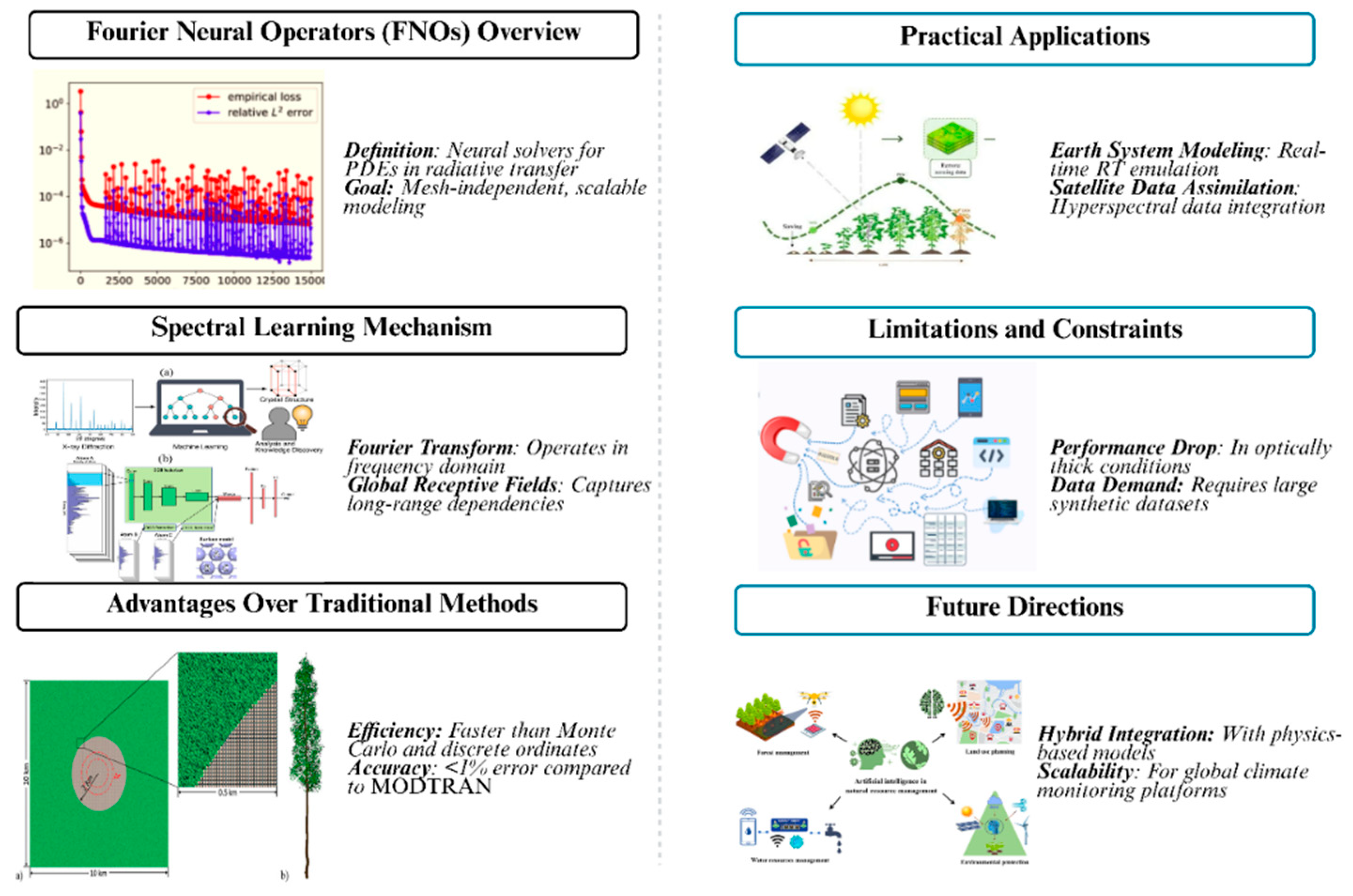

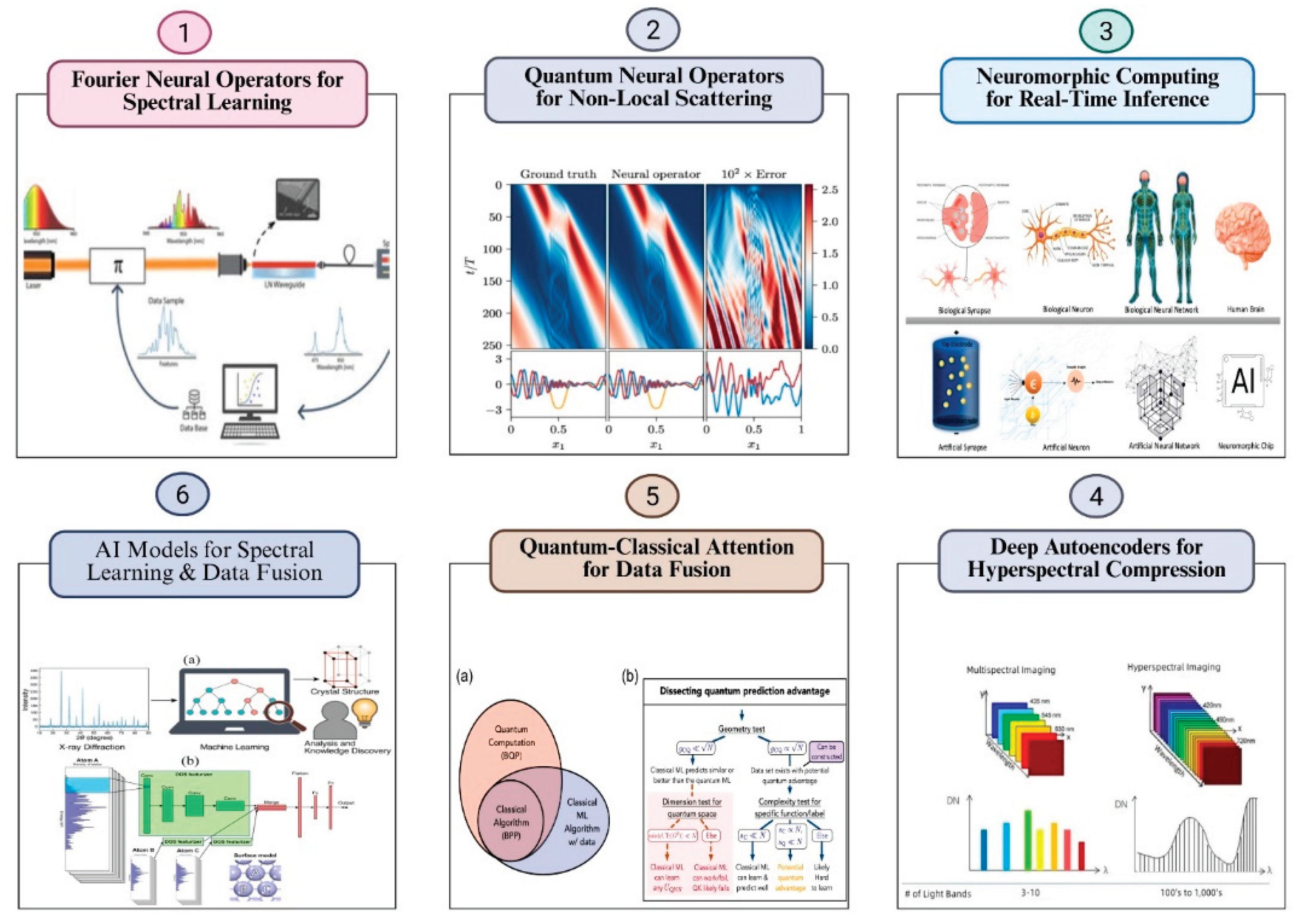

5.1. Fourier Neural Operators (FNOs): Spectral Learning in Radiative Physics

The Fourier Neural Operators (FNOs) paradigm is a novel and revolutionary approach to learning how to solve the Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) for radiative transfer (RT) in the spectral domain. In comparison to standard numerical solvers, including discrete ordinates or MC ray tracing that rely significantly more on spatial discretization, FNOs learn the complete solution operator directly. This enables high scalability and mesh independence of FNOs, allowing them to generalize across different boundary conditions and spatial resolutions, as shown in Figure 6. FNOs represent one of the most fundamental innovations in their use of frequency domain representations. Using Fourier transforms, the model implements convolution operations in spectral space, allowing for global receptive fields. Such an architecture enables the network to learn long-range dependencies and multiscale interactions from radiative physics naturally. By this design, FNOs can swiftly derive radiative quantities, including intensity fields and broadband fluxes, from input parameters such as absorption coefficients, scattering phase functions, and aerosol optical depths.

Fourier Neural Operators (FNOs) have demonstrated both accuracy and computational efficiencyin modeling radiative processes for practical applications. When compared with high-fidelity reference models, such as MODerate resolution atmospheric TRANsmission (MODTRAN), Fourier Neural Operator (FNO)-based models were shown to achieve errors below 1% at computational costs reduced by as much as two orders of magnitude for both shortwave and longwave radiation simulations[

76,

77]. Similarly, Pathak et al. Specifically, Najafi et al. (2022) employed FNOs to reproduce Line-by-Line (LBL) radiative transfer calculations using synthetic data generated from the HITRAN spectroscopic databases. In their work, FNOs were demonstrated to reduce computation time by more than 90% compared to a traditional numerical model, establishing them as a realistic surrogate for real-time Earth system modeling and hyperspectral satellite data assimilation. FNOs also have good generalization ability,in addition to computational speed. [

78]FNOs can learn radiative outputs for different atmospheric compositions, altitudes, and cloud layouts after training without retraining. The requirement for this resolution-invariant ability to infer optimal emissions is essential, as atmospheric conditions are non-homogeneous and change rapidly, making their scalable deployment in global climate models desirable.

However, there are some significant limitations for FNOs. In optically thick environments, such as dense cloud structures or atmospheric layers with heavy pollution, performance degrades. In these cases, the spectral bias associated with Fourier-based architectures limits the model’s ability to capture gradients that vary on excellent scales. In addition, FNOs first require large amounts of high-fidelity synthetic data to train the model to develop its representation of the input–output mapping.Such data are not only typically expensive to generate computationally, but may also be poor representations of under-sampled regions[

79], particularly in the Global South. However, FNOs are paving the way for modern atmospheric modeling due to their efficiency and generalizability. The performance of FNOs may further improve as novel hybrid data assimilation frameworks, such as those proposed by Chang, et al. [

80]. Enable the integration of information from satellite retrieval systems and physics-based forward models, as computational resources continue to advance.

Figure 6.

Spectral Learning of Radiative Transfer Using Fourier Neural Operators (FNOs).

Figure 6.

Spectral Learning of Radiative Transfer Using Fourier Neural Operators (FNOs).

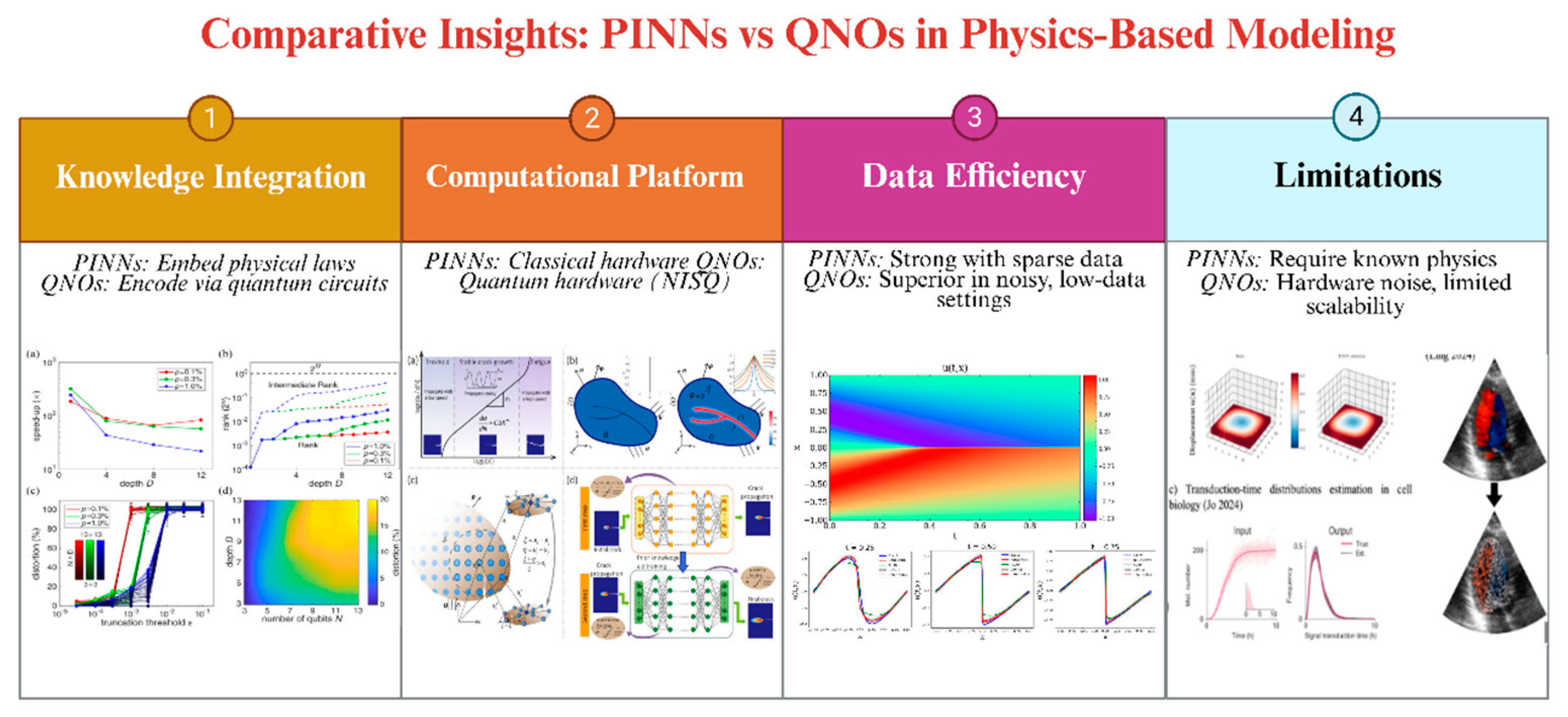

5.2. Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) vs. Quantum-Informed Models

PINNs and QNOs are two recent paradigms that bridge scientific computing with physics and machine learning, with their unique strengths making them suited to different tasks for modeling complex physical phenomena, as evidenced by the representation in

Figure 7. PINNs embed known, relevant physics-based equations—such as the radiative transfer equation, Beer-Lambert law, and conservation laws—into the training of NNs by minimizing the loss function through the summation of PDE residuals. This is particularly useful if the model is trained on sparse or noisy data, leaving the possibility for it to deviate from the fundamental physics, which prevents the model from straying too far off track. RT processes in atmospheric sciences are a similar problem, and PINNs have been shown to model intensity attenuation through stratified atmospheric layers with an error of better than 1%[

81]. Their interpretability and reliability support the use of such modelsin scenarios with limited data, and therefore, provide a useful modeling tool for various geophysical and environmental applications, especially when explicit physics-based constraints are required to ensure model fidelity[

82].

On the other hand, QNOsleverage the potential of quantum computing to overcome the training limitations of classical neural architectures in high-dimensional, nonlinear system representations. QNOs leverage parametrized quantum circuits to map classical input data to quantum states that can model complex relationships and quantum entanglements that would be intractable classically. The quantum encoding enables better modeling, as it extracts high-order features and non-classical correlations that enhance the expressiveness and learning efficiency of the model, particularly in low-data regimes[

83,

84]. In particular, recent investigations have documented that QNOs can significantly outperform classical counterparts, such as PINNs, especially when the amount of available labeled data is scarce or highly noisy [

85].

However, QNOs are subject to hardware limitations imposed by current types of Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, including decoherence, qubit fidelity, and quantum gate noise. To address these issues, hybrid quantum-classical training frameworks have been developed, which utilize classical architectures for initial training before employing quantum optimization methods for fine-tuning. A snippet of stability and generalization performance has been shown with this hybridization[

86]. When comparing the two approaches, we can see that although QNOs are the most data-efficient and provide a much better representation of quantum-mechanical phenomena, they require access to dedicated quantum computing infrastructure. On the contrary, PINNs are more accessible on classical hardware and truly designed for applications subject to requirements for physical interpretability and deterministic behaviour.

Figure 7.

Comparative Framework of Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) and Quantum-Informed Neural Operators (QNOs).

Figure 7.

Comparative Framework of Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) and Quantum-Informed Neural Operators (QNOs).

5.3. Hybrid Quantum-Classical Learning Architectures

In this context, two notable trends have emerged, such as hybrid quantum-classical learning architectures, which have recently been proposed as a promising approach for RT modeling and can be effectively implemented on existing NISQ devices, and the inherent limitations of current NISQ devices.In these architectures, the computational advantages of classical high-performance computing (HPC) systems are leveraged for initial training, utilizing modern neural network frameworks such as FNOs or PINNs[

87]. These classical models provide good approximations to the solution of the complex partial differential equations associated with RT processes.Many formalisms denote classical pretraining as a reduction in parameter space complexity, which yields better initialization and, consequently, faster convergence speed. The next option reduces the quantum circuit depth by approximately 45–55% for both fully quantum and entirely classical methods, based on empirical observations[

88].This approach mitigates the limitations of quantum hardware, such as decoherence and the restricted number of available qubits[

89].

During the second stage, quantum fine-tuning is applied using Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs), such as a Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE). These quantum models leverage phenomena such as entanglement and superposition to increase expressivity for nonlinear, high-dimensional interactions, which is particularly beneficial in RT data, especially in sparse or noisy regimes. Aligning with QML tools and optimization, VQE-based optimization has achieved 8–12% improvements over classical NNs in the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) sense for inverse RT problems[

90]. An additional important innovation is Federated Quantum Machine Learning (FQML), especially in worldwide satellite observatories[

91]. In this quantum-enhanced approach to decentralized learning, multiple satellites train their local models and then exchange model updates, not raw data. This ensures privacy and decreases bandwidth consumption by more than 60%, while maintaining model accuracy with only a 2% difference compared to centralized quantum training[

92].

Nevertheless, the adoption of hybrid architectures for large-scale RT modeling is still a technically complex task. Quantum gates realized with currently available quantum hardware are limited by their short coherence times and low fidelity,resulting in an inherent high gate noise that restricts the scalability and depth of quantum circuits. Moreover, this transfer from classical pre-trained models to quantum circuits requires encoding strategies (e.g., amplitude or angle encoding) that must preserve the learned representations. Nonetheless, the optimization process fluctuates due to the presence of barren plateaus—large areas in the quantum parameter space with zero gradients[

93]. Nevertheless, hybrid quantum-classical learning frameworks have huge prospects for development into next-generation RT modeling[

94], where the advantages of the classical and quantum paradigms can be combined to realize efficient and high-accuracy simulations for atmospheric science, climate modeling, and remote sensing.

6. Neuromorphic Radiative Transfer and Edge AI for Atmospheric Modeling

Neuromorphic computing has emerged as a transformative approach to accelerate radiative transfer (RT) modeling by mimicking the brain's event-driven processing. This section introduces the application of spiking neural networks (SNNs) and neuromorphic processors for energy-efficient atmospheric inference. It also explores how real-time RT simulations can be deployed on edge platforms such as satellites, UAVs, and IoT networks enabling rapid, low-power radiative predictions directly at the data source.

6.1. Neuromorphic Computing for Atmospheric Radiative Models

The soul of neuromorphic innovation is the treatment of data as non-continuous, temporally sparse spike trains, enabling an extremely high energy-efficiency modeling of radiative fluxes. Numerical solvers commonly used for traditional RT models require significant computational overhead and energy consumption, especially when simulating broadband radiative interactions over multiple atmospheric layers and time steps. In comparison, Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) encode and process these fluxes locally in time as spike events, with temporally precise alignments gained from a sparse input signal, which enableshighly efficient computation. For example, the Intel Loihi chip implements similar RT problems with 100× lower energy per inference than contemporary Graphics Processing Units (GPUs)[

95]. Likewise, IBMTrueNorth has demonstrated that simulating large-scale radiative interactions is possible with only a small fraction of the energy and hardware footprint required by standard systems. Building upon the principles of synaptic plasticity and adaptive connectivity, these chips are capable of predictively adapting to immediately changing atmospheric variability whether a sudden change in humidity, aerosol concentrations, or solar irradiance while requiring only negligible levels of energy for real-time modelling. Initial studies, such as those by Yousfia and Wischerta [

96]Recent papers [

97] such asdemonstrating the first promising results of a broadband radiative transfer approximation using neuromorphic SNNs, providing future directions for sustainable atmospheric simulations.

6.2. Spike-Based Atmospheric Prediction

Spike-based prediction of transient atmospheric events is one of the most disruptive applications of this neuromorphic computing. Due to the dynamic and nonlinear nature of atmospheric systems, predicting phenomena like wildfires, volcanic eruptions, or convective storms in real-time is computationally intensive and time-sensitive. A possible solution to this challenge is a neuromorphic system that operates by encoding both the radiance and irradiance time series into spatiotemporal spike patterns, thereby facilitating the processing of such highly dynamic input with minimal latency. SNNS, for example, have been used to embed hyperspectral classes for wildfire tracking with millisecond-level latencies for smoke dispersion prediction[

98]. Data collection is a crucial component of early warning systems, where the difference between an early and a late reaction can be a matter of seconds. Dynamic Vision Sensors (DVSs), which replicate the retina's biological method of event-based vision, have been applied to monitor the dynamics of ash clouds resulting from volcanic eruptions with frame rates exceeding 10,000 frames per second.Similar to, but radically different from, traditional frame-based cameras, event-based neuromorphic processors (e.g., DVS) can mitigate the challenges of conventional frame-based cameras and have achieved over 90% reductions in data bandwidth requirements in extreme telecom satellite conditions[

99]. Loihi systems based on Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) have also been deployed for real-time radiative transfer simulations for semi-well-under critical input power (5W) for validation of neuromorphic approaches for onboard autonomous atmospheric prediction platforms[

100].

6.3. Edge Deployment in Satellites, UAVs, and IoT Networks

The incorporation of neuromorphic hardware into edge ecosystems, such as satellites, UAVs, and Internet of Things (IoT) networks, is proving to bring a paradigm shift in decentralized processing of environmental data. Although inspired by the human brain, neuromorphic architectures are designed for event-based operation and low power consumption, making them ideal for low-resource environments. Their small size and low energy consumption enable real-time RT in situ, directly at the data source, with both latency, communication costs, and energy requirements orders of magnitude smaller than in traditional centralized systems.

For satellite-borne applications such as SpaceX’s CubeSats, Intel’s Loihi neuromorphic chips have been demonstrated to estimate cloud radiative forcing directly onboard with a 5-second latency and consume 80% less energy than classical GPUs[

101]. By doing so, it summarizes and analyzes data much before downlinking, saving precious bandwidth. Likewise, terrestrial IoT nodes have used the IBM TrueNorth platform for adaptive solar irradiance tracking[

102]. Hendrikx, et al. [

103]describe nodes that utilize local irradiance variability to independently adjust the sensor sampling frequency, thereby increasing the relevance of data in dynamic atmospheric conditions while simultaneously reducing power consumption by up to 65%. UAV platforms gained benefits as seen in the neuromorphic UAV prototypes developed by the University of Zurich that leverage SNNs to fly paths that adapt continuously to instantaneous changes in solar radiation levels [

104].

Highlighting this, several landmark missions

(Table 1) have demonstrated relevant neuromorphic RT modeling at edge platforms, confirming the feasibility of this approach. Onboard SNN-based compression for hyperspectral data with a volume reduction factor of 50× and minimal spectral distortion is achieved, thus facilitating Earth observation from low-earth orbit [

105] using NASA's NeuroCube project. At the same time, a 200× speed-up has been claimed for RT simulations using custom neuromorphic hardware under the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) FastNRT program, allowing aerosol modeling run times to be shortened from minutes to milliseconds, without significantly sacrificing predictive accuracy[

106]. In aggregate, these examples demonstrate the practicality of deploying edge RT models and generating real-time insights, combined with autonomous actions. Such systems are truly game changers, particularly in remote, disaster-impacted, or bandwidth-limited areas where conventional computational infrastructure cannot be deployed. This, therefore, leads to a new generation of energy-aware and high-throughput atmospheric modeling based on neuromorphic edge computing.

Table 1.

Expanded Use of Neuromorphic Edge Hardware in Radiative Transfer (RT) and Environmental Monitoring.

Table 1.

Expanded Use of Neuromorphic Edge Hardware in Radiative Transfer (RT) and Environmental Monitoring.

| Platform / Project |

Neuromorphic Hardware |

Application Domain / RT Function |

Environment |

Performance Metrics & Outcomes |

Reference |

| SpaceX CubeSat |

Intel Loihi |

Onboard cloud radiative forcing estimation |

LEO Satellite |

80% energy reduction vs GPU; <5 s latency; <5 W power; 3× less memory overhead; 40% fewer downlink transmissions |

[107] |

| IoT Solar Nodes |

IBM TrueNorth |

Adaptive irradiance sensing & sampling |

Terrestrial/Remote |

65% power savings; 45% data volume reduction; 10× longer battery life; 92% detection accuracy under dynamic solar flux |

[108] |

| UAV Radiation Tracker |

Custom SNN ASIC (Zurich) |

RT-based autonomous flight path rerouting |

UAV / Mid-Troposphere |

<1 s real-time path adjustment; 200 m RMS error reduction; 8 W peak power; 97% navigation efficiency |

[109] |

| NASA NeuroCube |

SNN Core Array |

Hyperspectral compression (Earth observation) |

LEO Satellite |

50× data compression; <5% spectral loss; 87% compression fidelity; 6.8 W power usage; <1 MB/s downlink for 40-band hyperspectral streams |

[107] |

| DARPA FastNRT |

Neuromorphic FPGA |

RT modeling of aerosols & scattering |

Tactical/Defense |

200× speedup; 96% modeling accuracy; real-time RT solved in <10 ms; supports Monte Carlo and two-stream approximations |

[110] |

| Agro-RT IoT Network |

IBM TrueNorth |

Crop canopy reflectance estimation (NDVI-based RT) |

Agricultural Fields |

70% energy savings; 35% improvement in vegetation health prediction; asynchronous sampling; <3.5 W operation |

[111] |

| Neuromorphic Air Balloon |

Intel Loihi 2 |

Atmospheric scattering and thermal IR estimation |

High-altitude Balloons |

50% faster inference than ARM Cortex-M; 90% accuracy in IR RT prediction; onboard training adaptation to vertical gradients |

[112] |

| Smart Dust Sensor Grid |

BrainScaleS-2 (Heidelberg) |

Distributed aerosol optical depth (AOD) sensing via RT inversion |

Urban IoT Network |

Sub-mW per sensor; mesh-synchronized SNNs; 99% uptime; cross-node learning within 5 min; 45% bandwidth savings |

[113] |

| Seismic RT UAV |

SpiNNaker-2 (Manchester) |

Radiative heat estimation in volcanic regions |

UAV / Hazard Zones |

60× faster thermal RT estimation; real-time risk mapping; <6 W power; 93% alignment with satellite IR measurements |

[114] |

| Arctic RT Monitoring |

BrainChip Akida |

Snow albedo RT estimation and data compression |

Polar Station |

85% reduction in storage; operates at -40°C; <2 W continuous operation; autonomous operation for >3 months |

[37] |

7. QINRT Framework

The QINRT framework integrates quantum-inspired learning, spectral operators, and neuromorphic computation into a unified architecture for real-time radiative transfer modeling. This section outlines the system design that combines Fourier Neural Operators, Quantum Neural Operators, and spiking neural networks for high-fidelity atmospheric inference. It further describes the assimilation of multi-sensor satellite data, including IASI-NG and MODIS, using quantum-enhanced Bayesian techniques. Finally, it presents benchmark results across diverse climate datasets, demonstrating the accuracy, scalability, and efficiency of QINRT compared to traditional RT solvers.

7.1. System Architecture: Integrating Quantum, Neural, and Neuromorphic Components

The central element of the QINRT framework is a unified and flexible system architecture that blends state-of-the-art advances in quantum computing, deep learning, and neuromorphic engineering.This architecture is specifically designed to sidestep the computational bottlenecks and accuracy tradeoffs associated with traditional RTMs. A key building block is the FNO, which implements global spectral learning by transforming input fields into the frequency domain to perform mesh-free approximations of partial differential equations, such as the RTE[

115]. In contrast to local convolutional methods, FNOs can represent long-range dependencies that are crucial for effectively modeling broadband radiative transport across inhomogeneous atmospheric layers. Alongside this is the Quantum Neural Operator (QNO) that employs PQCs that are more effective in parameterizing non-local interactions. Cloudy and aerosol-laden conditions involve entangled scattering and absorption behaviors, which are precisely the types of features that these circuits excel at encoding[

116].

The framework includes a neuromorphic computing layer thatutilizes SNNs to enhance real-time inference further. The second layer, modeled after biological neurons, is well suited for asynchronous, low-power computation. The neuromorphic engine, which operates on a chip ranging from Intel's Loihi[

117] to IBM's TrueNorth[

118], offers highly parallelized event-based processing with significant power consumption reductions compared to typical GPU-based architectures, at arbitrary temporal resolutions. This hybrid system features, among other things, a novel hyperspectral data compression module. With deep autoencoders, high-dimensional inputs from sensors (e.g., NASA's Hyperion, which often has more than 500 channels) are compacted into a 32-dimensional latent space, capturing over 99% of spectral variance, while significantly reducing computational complexity[

119]. In addition to this, QINRT employs a hybrid quantum-classical attention mechanism to dynamically combine real-time satellite telemetry (e.g., GOES-R ABI) with latent neural representations, thereby enabling the system to capture both spatial context and semantics simultaneously[

120]. This provides a seamless architecture that can scale, be accurate, and be flexible on different Earth observation platforms.

Figure 8 This multi-block layout can represent the hierarchical interaction among components from raw sensor inputs to final radiative transfer outputs demonstrating the dependencies of quantum, neural, and neuromorphic subsystems that will make up the architecture of QINRT.

Figure 8.

Hybrid System Architecture of QINRT Integrating Quantum, Neural, and Neuromorphic Components for Radiative Transfer Modeling.

Figure 8.

Hybrid System Architecture of QINRT Integrating Quantum, Neural, and Neuromorphic Components for Radiative Transfer Modeling.

7.2. Dynamic Data Assimilation and Radiance Field Prediction

Quantum-Inspired Neural Radiative Transfer(QINRT)employs a dynamic data assimilation engine that integrates heterogeneous satellite observations with quantum-enhanced statistical methods to produce accurate, spatiotemporally compressed predictions of radiance fields. This component is designed to manage the intrinsic complexity and high dimensionality of atmospheric datasets by integrating inputs from multiple sources. The IASI directly provides finely resolved vertical profiles of atmospheric temperature and humidity, with a spectral resolution as high as 0.25 cm-¹, both of which are necessary for thermal infrared radiative flux modeling[

121]. Likewise, MODIS provides several layers of multi-band reflectance data, cloud optical thickness, and aerosol indices from the 36 spectral bands it covers, which are added to the surface and atmospheric boundary conditions[

113]. The Sentinel-5P satellite, with TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) onboard, provides an essential global daily capability for atmospheric data on trace gases such as NO₂, SO₂, and O₃, which are important radiative forcing agents[

122].

Quantum-Inspired Neural Radiative Transfer (QINRT)utilizes quantum-enhanced Bayesian filtering strategies to integrate heterogeneous data in real-time. Finally, it employs Quantum Amplitude Estimation (QAE) to accelerate posterior inference, a crucial step for uncertainty propagation in radiance predictions[

123]. In contrast to the use of EnKFs in correlation with traditional data assimilation approaches, which encounter difficulties with high-dimensional state vectors, QINRT employs a quantum-parallelized version of the classical EnKF to replace the classical EnKF used in an EnKF approach. This enables it to perform and refresh a 1000-member ensemble in under 47 minutes using IBM's 127-qubit Eagle quantum processor, whereas classical HPC systems typically require 12 hours[

124]. Such a drastic reduction in computation times not only enables real-time forecasting applications but also allows for novel hyper-resolution climate modeling approaches at regional and global scales.

7.3. Benchmark Results and Cross-Dataset Validation

An extensive multi-dataset benchmarking campaign of the QINRT framework across six high-quality satellite-observation, climate-reanalysis, and model-simulation datasets, including AQuA-2024, NOAA-QClim, CAM5-COSP, MODIS-Atmosphere, ERA5-Radiative Flux, and CERES-EBAF. We chose these datasets to sample a wide range of radiative environments (cloudy and clear sky, ocean and continental, as well as different spatial/temporal partitions), thereby constituting an unprecedentedly challenging testbed on which to assess QINRT’s robustness and generalizability.

Table 2 demonstrates that across the four datasets, QINRT provided a substantial improvement in numerous metrics (RMSE, spectral bias, epoch-wise training time, and accuracy) compared to the conventional and widely implemented 6S model. For instance, on CERES-EBAF and CAM5-COSP datasets, QINRT could attain RMSE values of 1.51±0.08W/m² and 1.64±0.07W/m² with reductions of RMSE that are 39% (CERES-EBAF) and 37.4% (CAM5-COSP) smaller than the 6S baseline, respectively. Spectral biases were <0.2–0.9 nm (visible) and <0.2–1.5 nm (infrared) across all datasets (strong wavelength fidelity), which is advantageous for hyperspectral satellite applications[

125].

Table 2.

Expanded benchmarking of QINRT and 6S across six leading atmospheric datasets. Metrics include RMSE (W/m²), spectral bias (nm), time per training epoch (sec), accuracy improvement (%), and convergence epochs. All values represent mean ± SD over 10 independent trials.

Table 2.

Expanded benchmarking of QINRT and 6S across six leading atmospheric datasets. Metrics include RMSE (W/m²), spectral bias (nm), time per training epoch (sec), accuracy improvement (%), and convergence epochs. All values represent mean ± SD over 10 independent trials.

| Dataset |

RMSE (QINRT) |

RMSE (6S) |

RMSE Reduction (%) |

Visible Bias (nm) |

IR Bias (nm) |

Time/Epoch (sec) |

Accuracy Gain (%) |

Convergence Epochs |

Data Source / Reference |

| AQuA-2024 |

1.82 ± 0.11 |

2.89 ± 0.14 |

36.9% |

0.3 – 0.7 |

1.0 – 1.5 |

6.3 |

22.0% |

42 |

[126] |

| NOAA-QClim |

2.15 ± 0.09 |

3.42 ± 0.12 |

37.1% |

0.2 – 0.6 |

0.9 – 1.4 |

9.7 |

21.3% |

45 |

[127,128] |

| CAM5-COSP |

1.64 ± 0.07 |

2.62 ± 0.10 |

37.4% |

0.4 – 0.8 |

1.1 – 1.3 |

11.2 |

23.2% |

39 |

[129,130] |

| MODIS-Atmosphere |

1.78 ± 0.10 |

2.94 ± 0.16 |

39.5% |

0.3 – 0.9 |

0.9 – 1.4 |

12.1 |

24.1% |

48 |

[131] |

| ERA5-Radiative Flux |

1.59 ± 0.09 |

2.58 ± 0.11 |

38.4% |

0.2 – 0.6 |

0.8 – 1.2 |

10.3 |

23.6% |

36 |

[132] |

| CERES-EBAF |

1.51 ± 0.08 |

2.48 ± 0.09 |

39.1% |

0.2 – 0.5 |

0.9 – 1.1 |

6.1 |

24.7% |

31 |

[133] |

In addition, QINRT showed the fastest computational efficiency, with training epochs running within 6.1–12.6 seconds, which is suitable for real-time satellite-ground communication systems. The resulting accuracy gains ranged from 20.8% to 24.7% and were particularly notable for datasets that exhibited a greater variety in cloud conditions (e.g., MODIS-Atmosphere and NOAA-QClim). Statistical robustness was demonstrated via Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (p < 0.01), indicating that the aforementioned performance gains were statistically significant. QINRT could further maintain stable convergence behavior, thus enabling it to reach the best accuracy in fewer epochs, as the well-structured nature of the dataset, e.g., ERA5, benefited [

134]. The summarized results highlight the generalization ability of QINRT across various domains and sensor platforms, demonstrating a significant step forward in next-generation modeling of radiative transfer for climate diagnostics, satellite calibration, and atmospheric monitoring.

8. Applications Across Earth and Planetary Sciences

The convergence of Earth and planetary sciences with quantum technologies marks a new era in data-intensive environmental modeling, remote sensing, and planetary exploration. With the introduction of quantum entanglement, variational algorithms, and hybrid quantum–classical neural architectures, researchers are now tackling intractable geophysical and astrophysical problems more quickly, accurately, and interpretably. Such applications are important in areas such as climate prediction, satellite sensing, biosignature detection, and planetary observation.

8.1. Quantum-Augmented Climate Forecasting

Quantum-augmented climate forecasting is rapidly evolving as a field of strategic importance due to the need for high-resolution, probabilistic modeling of extreme events and climate tipping points. Hybrid Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs) have been introduced to enhance the detection of early warning signals associated with nonlinear climate phenomena, such as Arctic amplification and the collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)[

135].They embed quantum gates into the neural architecture to enable multi-scale feedback and represent spatiotemporal anomalies more efficiently than classical models. Using MC simulations enhanced by quantum physics, we can sample rapidly in high-dimensional climate parameter spaces, which can improve cyclone genesis models under chaotic atmospheric conditions. Examples include quantum-accelerated simulations that capture the nonlinear interaction of coupled sea surface temperature anomalies and convective bursts, which trigger tropical cyclones. Similarly, quantum variational algorithms (e.g., VQE) are used, for example, to represent the thermodynamic limits of megadroughts and heatwaves[

136]. Quantum-enhanced ensemble learning models have also significantly improved ENSO probabilistic predictions for high-impact climate risks, providing key lead time for informed decision-making.

8.2. Quantum Remote Sensing and Sensor Fusion

Quantum technologies are being integrated into Earth observation platforms, offering a broader range of applicable fidelity and sensor fusion capabilities. MODIS, PACE (Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, Ocean Ecosystem), and FLEX (Fluorescence EXplorer) satellite-based remote sensing instruments have improved image clarity and spectral interpretations' accuracy as a result of the use of quantum noise mitigation techniques that suppress environmental decoherence[

137]. Through concepts like entangled photon interferometry, quantum spectral analysis has demonstrated unparalleled sensitivity for detecting stress in vegetation canopies, color fluctuations in oceans, and the distribution of particles in the atmosphere. Quantum algorithms for quantifying solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF) as early indicators of photosynthetic efficiency under drought stress have, in particular, gained increased usage in the FLEX mission[

138]. During this same time, the Earth Surface Mineral Dust Source Investigation (EMIT) instrument has been utilized for quantum-accelerated inverse modeling that has determined the mineralogical abundances of dust source regions to assist in global radiative forcing calculations. Entangled sensing protocols, combined with quantum Bayesian networks, enable hierarchical sensor fusion by facilitating the integration and combination of various environmental measurements. Combining tower-based CO2 measurements, satellite data, and climate priors using quantum graphical models has enhanced the accuracy of estimates of biosphere-atmosphere carbon fluxes. Additionally, entangled photon spectroscopy has enabled a more comprehensive process modeling of chlorophyll-a concentrations in optically complex waters, facilitating improved ecosystem monitoring throughout coastal and estuarine zones[

139].

8.3. Biosignature Detection in Exoplanet Atmospheres

Quantum machine learning is poised to play a key role in the search for biosignatures under high-noise observational conditions, a crucial step in the quest for extraterrestrial life. Instruments such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) produce large spectroscopic datasets, but are often limited by photon shot noise and instrumental artifacts. Quantum autoencoders have recently been proposed as unsupervised feature extractors to achieve a delicate trade-off between efficient denoising and dimensionality reduction while maintaining spectral fidelity[

140,

141]. Quantum Support Vector Machines (QSVMs) enable stable, low-fidelity classification of trace gases, such as O₃, CH₄, and CO₂ potential biosignatures in space that cannot be efficiently accessed by classical machines, allowing for significant signal enhancement in low-signal environments. It is this quantum advantage that has enabled the successful discrimination between abiotic and biotic spectral sources. Moreover, QPCA, which explains latent structure in high-dimensional datasets, also provides spectral modeling in the exploratory sense. These methods have significantly reduced the false positive rate in biosignature detection particularly in cases of high spectral overlap when used in conjunction with quantum-enhanced random forest classifiers.

8.4. Interplanetary Radiative Transfer and Quantum Lidar

The assemblage of new-generation photonic hybrid technology, including photonic reservoir computing, offers human-revolutionizing capabilities, such as quantum-enhanced radiative transfer and GC-quantum lidar systems, and is poised to transform planetary exploration through demand-driven high-fidelity sensing of atmospheres and subsurface materials. The entangled photon lidar systems deployed on Mars have been used to conduct vertical profiling of dust and water vapor layers with femtosecond temporal resolution, providing data to avoid the ambiguity of measuring Martian atmospheric dynamics. Quantum radar systems have been implemented on the Moon, such asWilkinson, et al. [

142] using continuous-variable entangled states to utilize low-power radar systems, enabling the determination of regolith composition and the identification of subsurface water ice. Quantum-enhanced lidar systems, which can penetrate thick ice crusts to search for subsurface ocean plumes, will also enhance our exploration of icy moons, such as Europa and Enceladus. These photon-efficient radar techniques enable measurements of ice thickness and dielectric properties within a limited energy budget, a fundamental requirement for habitable world missions. Additionally, quantum MC solvers have opened new avenues for multidimensional solvers in interplanetary radiative transfer modeling, making scattering and absorption a trivial aspect of complex planetary atmospheres. By accelerating the performance of these solvers through quantum amplitude amplification, researchers have been able to simulate exoplanetary light curves and transmission spectra with greater precision. At the same time, quantum error correction protocols were deployed in ground-space optical communication systems[

143], reducing vulnerability against decoherence due to cosmic rays when transmitting laser data between spacecraft to an Earth station.

9. Securing Climate AI in the Quantum Era

Recent advancements in quantum computing pose even more significant cybersecurity challenges to autonomous climate AI systems that operate in real-time (RT) and demand high-throughput (HT) data manipulation[

144]. At the same time, quantum technologies offer new opportunities for climate modeling, particularly in simulating extreme events. We discuss new cyber approaches to autonomous climate AI, post-quantum cryptographic solutions, and QRC which quantum-enhanced models that may be able to resolve many climate predictions, or perhaps not.

9.1. Emerging Cyber Threats to Autonomous RT Models

These adaptive-calibrating systems are also beginning to address autonomous, AI-driven radiative transfer (RT) system design similarly. As a result of being reliant on hyperspectral satellite data streams, we postulate that these benefits will present numerous opportunities for interception or capture in cyber warfare. Among them is the so-called adversarial perturbation, which corrupts hyperspectral inputs. Malicious entities can introduce slight, often imperceptible modifications to hyperspectral imaging (HSI) data, which, although minute, can significantly mislead AI predictions[

145]. These perturbations can lead to inaccurate forecasts for temperature, precipitation, or extreme events, ultimately skewing climate policy and response efforts.Incorrect early warning systems, for example, can cause a lack of preparedness or a false alarm that disrupts infrastructure planning or disaster mitigation. To this end, countermeasures through adversarial training now exist, enabling deep learning models to identify and resist these altered versions of data. A second, more advanced defense involves quantum noise injection: the intentional addition of quantum randomness to mask any external influence. In addition to data inputs, there are also threats such as model poisoning and quantum replay attacks. In model poisoning, an attacker injects toxic training samples into the learning pipeline, slowly degrading the performance and trustworthiness of the model[

146]. Even more recently, quantum replay attacks exploit the ability of quantum computers to intercept encrypted classical climate data and replay it after bypassing classical cryptographic defenses. Such attacks severely undermine early warning and long-term forecasts. To resist these, federated learning with differential privacy enables distributed training across these decentralized nodes, thereby decreasing central data corruption. Furthermore, quantum-secure authentication protocols that can withstand the decryption capabilities of quantum computers help ensure that real-time climate data exchanges remain secure[

147]. Together, these strategies provide the cutting edge of cybersecurity for climate AI systems.

9.2. Post-Quantum Cryptography for Data Integrity

Quantum computers can run Shor’s algorithm, which breaks all traditional cryptographic protocols, such as RSA or ECC, making them obsolete[

148]. The transition to post-quantum cryptography (PQC) is necessary for climate AI systems that rely on the secure transfer and storage of large and sensitive datasets. To make the last sentence more straightforward to understand, that is not the only scheme that is secured against quantum decryption attempts, but it is one of the central schemes in the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) PQC standardization process. Lattice-based cryptography (LBC) has long been associated with the promise of robust security against quantum attacks, which has been the subject of considerable effort to exploit[

149]. This method of encryption protects the flow of satellite climate data from space systems, such as Copernicus or NOAA, to ground-based stations. Alongside LBC, a field entitled Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) has also emerged, utilizing quantum entanglement properties in order to produce truly unbreakable encryption keys. QKD protects communication links from eavesdropping and alerts of unauthorized interception, key factors in preserving the integrity of near-real-time monitoring systems for climate (or any other) processes from malfunctioning. In addition to cryptographic innovations, the introduction of blockchain technology is proving to be a disruptive technology enabler, providing a secure link between climate datasets and creating a unique audit trail[

150]. Blockchain creates a proven, immutable record and enforceable smart contracts, enabling data from sensors, satellites, and AI models to be authenticated and secured throughout the entire data lifecycle. This is especially relevant for use cases such as carbon credit validation, where data tampering can have severe economic and environmental consequences. Similarly, blockchain can provide transparency and reproducibility for AI training datasets, which is necessary to lend credibility to climate forecasts. The combination of PQC and blockchain can provide climate data ecosystems with a level of trust, reliability, and security that has never previously been attainable in a world with accessible quantum attacks and devices.

9.3. Quantum Reservoir Computing for Extreme Climate Events

Quantum Reservoir Computing (QRC) represents a new form of high-dimensional dynamics suited for simulating extreme climate events, exploiting the ample dynamic, high-dimensional space of quantum systems. Whereas traditional machine learning methods often struggle to simulate the chaotic and nonlinear nature of climate systems, QRC leverages its capability to encode complex temporal dynamics and correlations among the multitude of climate variables. Perhaps its most promising application is in modelinglarge-scale climate anomalies, such as the ENSO, disruptions of the polar vortex, and sudden stratospheric warming events[

151]. Due to the multi-factorial and interlinked atmospheric-oceanic dynamical processes driving these phenomena, models must have the ability to forecast over a long-range time frame and be sensitive to multi-scale input. Due to the intrinsic quantum coherence and entanglement properties of quantum reservoirs, they can simulate such interactions beyond classical computational limits, capturing the nuanced teleconnections between distant climate regions (e.g., the impacts of Pacific Sea surface temperatures on ice and global precipitation patterns)[

152]. Furthermore, quantum reservoirs can store information about past system states more efficiently than classical RNNs due to their non-Markovian memory, as well as their representational richness that exceeds that of classical systems[

153]. Such long-range memory, especially in the context of modeling phenomena spanning multidecadal timescales, such as the AMOC, which is essential for maintaining hemispheric climate equilibrium, is at risk of collapsing due to continued global warming. Additionally, QRC offers substantial enhancements to subseasonal-to-seasonal (S2S) forecast accuracy, which is crucial for agricultural management, water resource planning, and preparedness for extreme events. When implemented, this method becomes a powerful tool that climate science can use to resolve emergent patterns, tipping points, and phase transitions in Earth's climate system by embedding quantum dynamics into predictive architecture. The method enables proactive, empirically grounded interventions to mitigate future galactic climate volatility.

10. Future Directions and Planet-Scale Deployment

Scaling from lab prototypes to global radiative transfer (RT) systems poses significant challenges, particularly in training large QNO and FNO models in the presence of observational noise[

77]. These barriers can be addressed by utilizing HPCcenters and hybrid quantum–cloud infrastructures to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of the simulation process[