Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material, Essential Oil Extraction, and Chemical Characterization of Essential Oils

2.2. Antioxidant Activity

2.2.1. ABTS [2,2’-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid)] Assay

2.2.2. DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) Assay

2.3. In Vitro Antifungal Activity Assay

2.3.1. Fungal Isolation

2.3.2. Antifungal Activity

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Essential Oil Composition

3.2. Antioxidant Activity

3.3. In Vitro Antifungal Activity Assay

3.3.1. Fungal Isolation

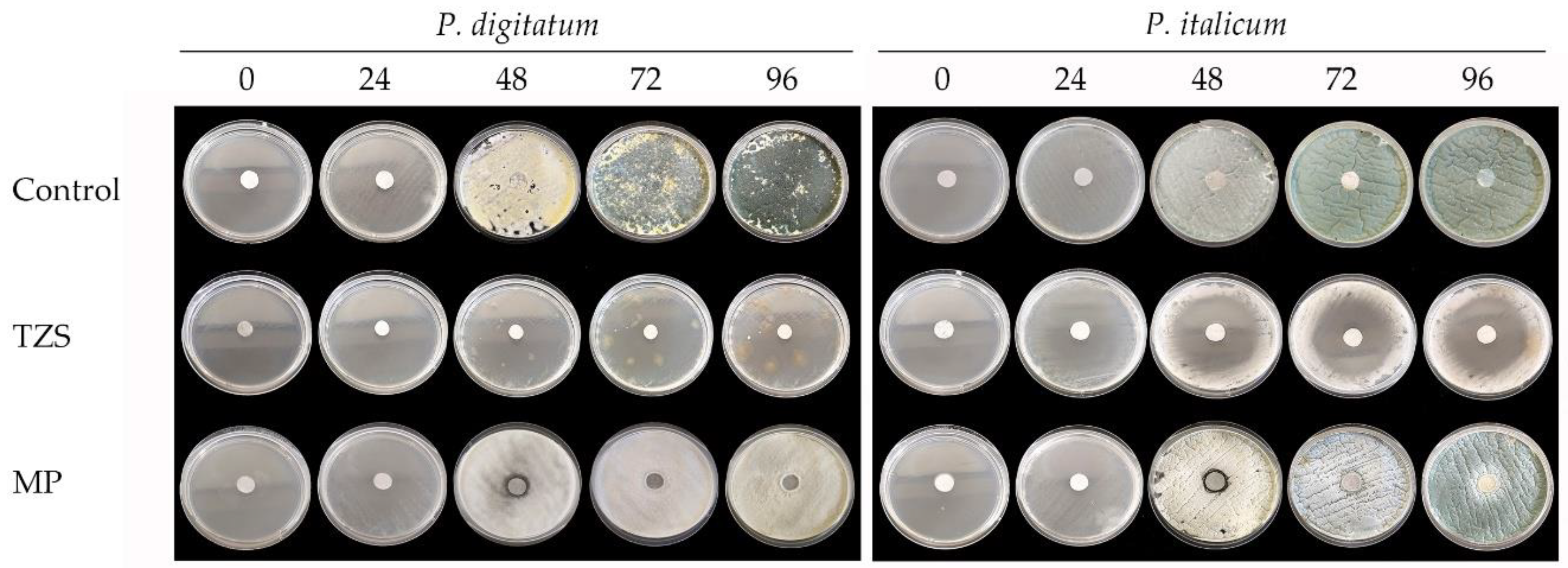

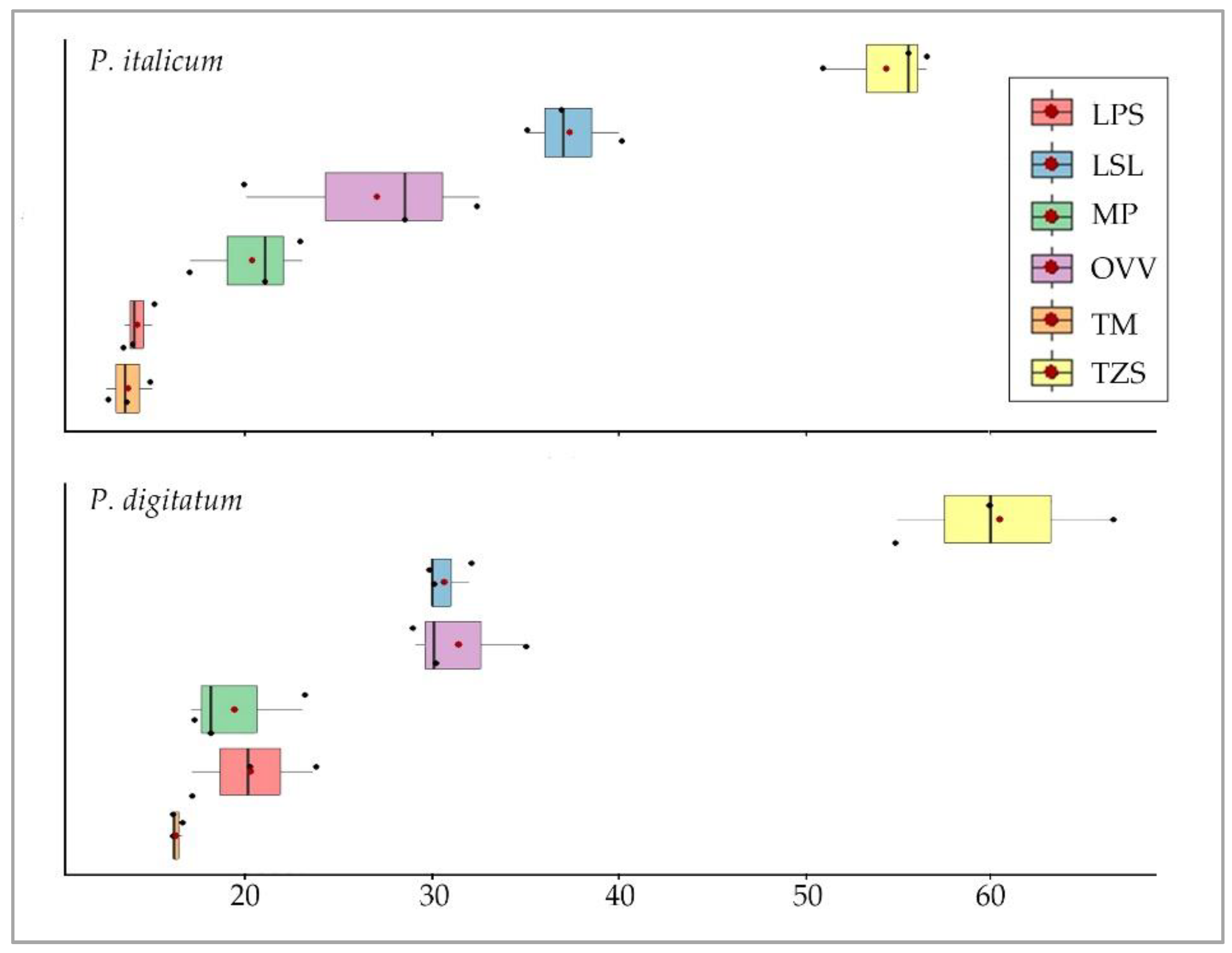

3.3.2. Antifungal Activity

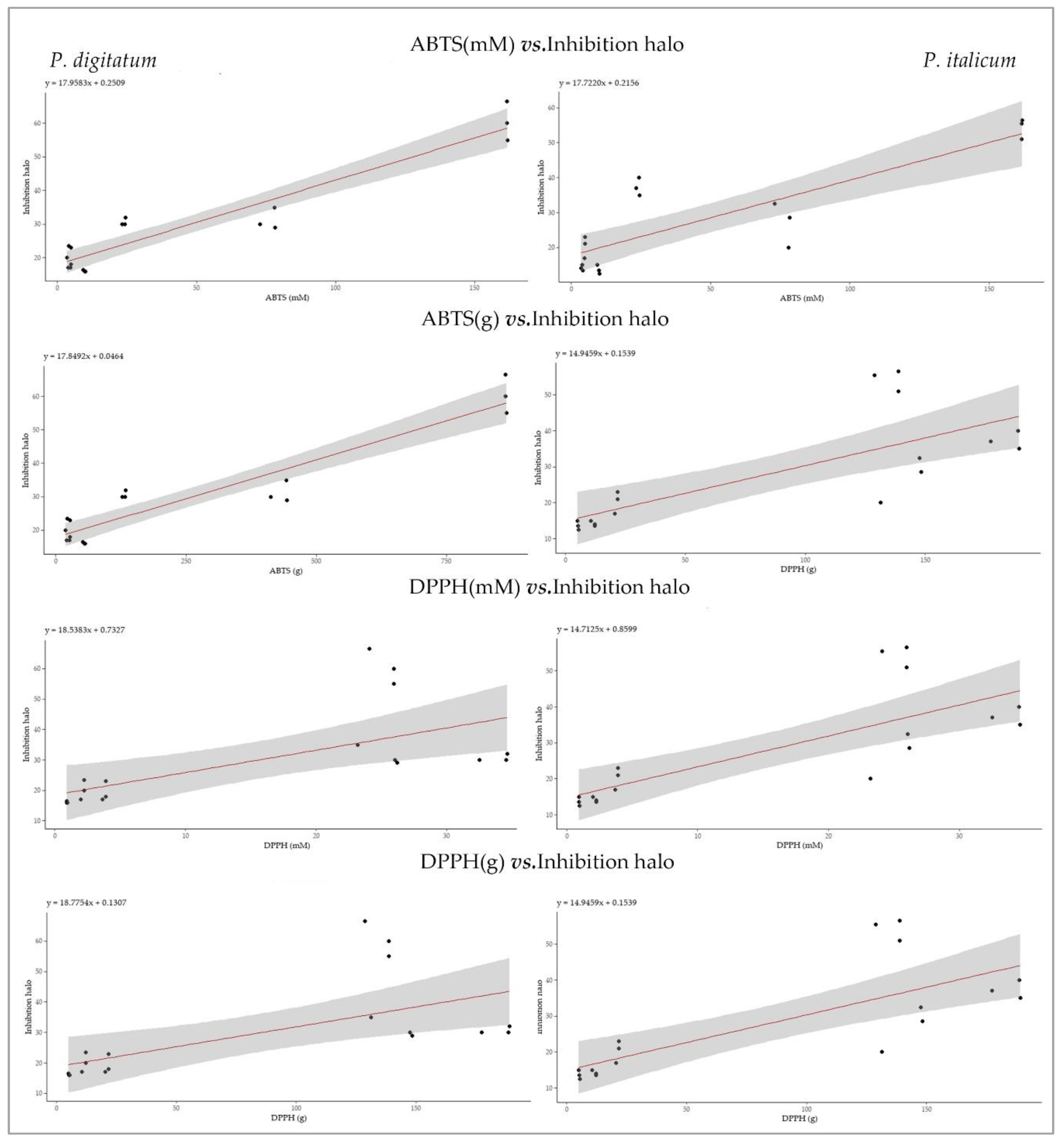

3.3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hodges, R.J.; Buzby, J.C.; Bennett, B. Postharvest losses and waste in developed and less developed countries: opportunities to improve resource use. J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 149(S1), 37–45. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, A.B.; Worobo, R.W. Fungal Spoilage in Food Processing, J. Food Prot. 2018, 81(6), 1035–1040. [CrossRef]

- Rizwana, H.; Bokahri, N.A.; Alsahli, S.A.; Al Showiman, A.S.; Alzahrani, R.M.; Aldehaish, H.A. Postharvest disease management of Alternaria spots on tomato fruit by Annona muricata fruit extracts. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28(4), 2236–2244. [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, Q.; Shaheen, M.R.; Ali, S.; Ahmad, A.; Raheel, M.; Bajwa, R.T. Chapter 1 - Postharvest management of fruits and vegetables. In Applications of Biosurfactant in Agriculture, Inamuddin, C.O.A. Ed., Academic Press, 2022, pp. 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, L. Fusarium Species Associated with Diseases of Major Tropical Fruit Crops. Horticulturae 2023, 9(3), 322. [CrossRef]

- Pouris, J.; Kolyva, F.; Bratakou, S.; Vogiatzi, C.A.; Chaniotis, D.; Beloukas, A. The Role of Fungi in Food Production and Processing. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14(12), 5046. [CrossRef]

- Dijksterhuis, J.; Houbraken, J. Fungal Spoilage of Crops and Food. In Agricultural and Industrial Applications. The Mycota, Grüttner, S., Kollath-Leiß, K., Kempken, F. Eds., Springer, Cham, 2025, 16, pp. 31–66. [CrossRef]

- Palou, Ll.; Valencia-Chamorro, S.A.; Pérez-Gago, M.B. Antifungal edible coatings for fresh citrus fruit: A review. Coatings 2015, 5(4), 962–986. [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.H.; Wassano, C.I.; Angolini C.F.F.; Scherlach, K.; Hertweek, C.; Fill, T.P. Antifungal potential of secondary metabolites involved in the interaction between citrus pathogens. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18647. [CrossRef]

- Papoutsis, K.; Mathioudakis, M.M.; Hasperué, J.H.; Ziogas, V. Non-chemical treatments for preventing the postharvest fungal rotting of citrus caused by Penicillium digitatum (green mold) and Penicillium italicum (blue mold). Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 86, 479–491. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Lin, Y.; Cao, H.; Li, Z. Citrus Postharvest Green Mold: Recent Advances in Fungal Pathogenicity and Fruit Resistance. Microorganisms 2020, 8(3), 449. [CrossRef]

- Hanif, Z.; Ashari, H. Post-harvest losses of citrus fruits and perceptions of farmers in marketing decisions. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 306, 02059. [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, Z.R.; Ali, S.H.; AL-Rubaye, S.A. The economic impacts of the post-harvest losses of tangerines and Seville oranges crops in Iraq (Baghdad Governorate: As a case study). Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2025, 31(2), 237–244.

- Hall, D.J. Comparative activity of selected food preservatives as citrus postharvest fungicides. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 1988, 101, 184–187.

- Holmes, G.J.; Eckert, J.W. Sensitivity of Penicillium digitatum and P. italicum to postharvest citrus fungicides in California. Phytopathology 1999, 89, 716–721. [CrossRef]

- Talibi, I.; Boubaker, H.; Boudyach, E.H.; Ait Ben Aoumar, A. Alternative methods for the control of postharvest citrus diseases. J Appl Microbiol. 2014, 117(1), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Zeng, Z.; Li, Z.-L.; Jiang, H. Synthesis of Oxylipin Mimics and Their Antifungal Activity against the Citrus Postharvest Pathogens. Molecules 2016, 21(2), 254. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Shen, Y.; Chen, C.; Wan, C. Inhibition of Key Citrus Postharvest Fungal Strains by Plant Extracts In Vitro and In Vivo: A Review. Plants 2019, 8(2), 26. [CrossRef]

- Kanashiro, A.M.; Akiyama, D.Y.; Kupper, K.C.; Fill, T.P. Penicillium italicum: An Underexplored Postharvest Pathogen. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 606852. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sui, Y.; Li, J.; Tian, X.; Wang, Q. Biological control of postharvest fungal decays in citrus: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020 62(4), 861–870. [CrossRef]

- Strano, M.C.; Altieri, G.; Allegra, M.; Di Renzo, G.C.; Paterna, G.; Matera, A.; Genovese, F. Postharvest Technologies of Fresh Citrus Fruit: Advances and Recent Developments for the Loss Reduction during Handling and Storage. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 612. [CrossRef]

- Tejeswini, M.G.; Sowmya, H.V.; Swarnalatha, S.P.; Negi, P.S. Antifungal activity of essential oils and their combinations in vitro and in vivo conditions. Arch. Phytopathol. Pflanzenschutz 2013, 47(5), 564–570. [CrossRef]

- Felšöciová, S.; Vukovic, N.; Jeżowski, P.; Kačániová, M. Antifungal activity of selected volatile essential oils against Penicillium sp. Open Life Sci. 2020, 15(1), 511-521. [CrossRef]

- Abd Rashed, A.; Rathi, D.-N.G.; Ahmad Nasir, N.A.H.; Abd Rahman, A.Z. Antifungal Properties of Essential Oils and Their Compounds for Application in Skin Fungal Infections: Conventional and Nonconventional Approaches. Molecules 2021, 26(4), 1093. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, E.S.; Rosalen, P. L.; Benso, B.; de Cássia Orlandi Sardi, J.; Denny, C.; Alves de Sousa, S.; Queiroga Sarmento Guerra, F.; de Oliveira Lima, E.; Almeida Freires, I.; Dias de Castro, R. The Use of Essential Oils and Their Isolated Compounds for the Treatment of Oral Candidiasis: A Literature Review. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2021, 1059274. [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.; Sana, S.S.; Li, H.; Xing, Y.; Nanda, A.; Netala, V.R.; Zhang, Z. Essential oils and its antibacterial, antifungal and anti-oxidant activity applications: A review. Food Biosci. 2022, 47, 101716. [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.M.; Le, D.H.; Nguyen, V.-A.T.; Vu, T.X.; Thanh, N.T.K.; Giang, D.H.; Dat, N.T.; Pham, H.T.; Muller, M.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Tran, V.-T. Penicillium digitatum as a Model Fungus for Detecting Antifungal Activity of Botanicals: An Evaluation on Vietnamese Medicinal Plant Extracts. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 956. [CrossRef]

- Daferera, D.J.; Ziogas, B.N.; Polissiou, M.G. GC-MS analysis of essential oils from some Greek aromatic plants and their fungitoxicity on Penicillium digitatum. J Agric Food Chem. 2000, 48(6), 2576–2581. [CrossRef]

- Plaza, P.; Torres, R.; Usall, J.; Lamarca, N.; Vinas, I. Evaluation of the potential of commercial postharvest application of essential oils to control citrus decayJ. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2004, 79(6), 935–940. [CrossRef]

- Yahyazadeh, M.; Omidbaigi, R.; Zare, R, Taheri, H. Effect of some essential oils on mycelial growth of Penicillium digitatum Sacc. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008, 24, 1445–1450. [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Lei, Z.; Li, L.; Xie, R.; Xi. W.; Guan, Y. Sumner, L.W.; Zhou, Z. Antifungal Activity of Citrus Essential Oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62(14), 3011–3033. [CrossRef]

- Tao, N.; Jia, L.; Zhou, H. Anti-fungal activity of Citrus reticulata Blanco essential oil against Penicillium italicum and Penicillium digitatum. Food Chem. 2014, 153, 265–271. [CrossRef]

- Boubaker, H.; Karim, H.; El Hamdaoui, A.; Msanda, F.; Leach, D.; Bombarda, I.; Vanloot, P.; Abbad, A.; Boudyach, E.H.; Ait Ben Aoumar, A. Chemical characterization and antifungal activities of four Thymus species essential oils against postharvest fungal pathogens of citrus. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016, 86, 95–101. [CrossRef]

- Moussa, H.; El Omari, B.; Chefchaou, H.; Tanghort, M.; Mzabi, A.; Chami, N.; Remmal, A. Action of thymol, carvacrol and eugenol on Penicillium and Geotrichum isolates resistant to commercial fungicides and causing postharvest citrus decay. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 43(1), 26–34. [CrossRef]

- Et-tazy, L.; Lamiri, A.; Satia, L.; Essahli, M.; Krimi Bencheqroun, S. In Vitro Antioxidant and Antifungal Activities of Four Essential Oils and Their Major Compounds against Post-Harvest Fungi Associated with Chickpea in Storage. Plants 2023, 12, 3587. [CrossRef]

- Martins, G.A.; Bicas, J. L. Antifungal activity of essential oils of tea tree, oregano, thyme, and cinnamon, and their components. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2024, 27, e2023071. [CrossRef]

- Arras, G.; Usai, M. Fungitoxic Activity of 12 Essential Oils against Four Postharvest Citrus Pathogens: Chemical Analysis of Thymus capitatus Oil and its Effect in Subatmospheric Pressure Conditions. J. Food Prot. 2001, 64(7), 1025–1029. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Wills, R.B.H.; Bowyer, M.C.; Golding, J.B.; Kirkman, T.; Pristijono, P. Efficacy of Orange Essential Oil and Citral after Exposure to UV-C Irradiation to Inhibit Penicillium digitatum in Navel Oranges. Horticulturae 2020, 6, 102. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.V.; Palou, L.; Taberner, V.; Fernández-Catalán, A.; Argente-Sanchis, M.; Pitta, E.; Pérez-Gago, M.B. Natural Pectin-Based Edible Composite Coatings with Antifungal Properties to Control Green Mold and Reduce Losses of ‘Valencia’ Oranges. Foods 2022, 11, 1083. [CrossRef]

- Wardana, A.A.; Kingwascharapong, P.; Wigati, L.P.; Tanaka, F.; Tanaka, F. The antifungal effect against Penicillium italicum and characterization of fruit coating from chitosan/ZnO nanoparticle/Indonesian sandalwood essential oil composites. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 32, 100849. [CrossRef]

- Olmedo, G.M.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, W.; Mattia, M.; Rosskopf, E.N.; Ritenour, M.; Plotto, A.; Bai, J. Application of Thymol Vapors to Control Postharvest Decay Caused by Penicillium digitatum and Lasiodiplodia theobromae in Grapefruit. Foods 2023, 12, 3637. [CrossRef]

- Gharzouli, M.; Aouf, A.; Mahmoud, E.; Ali, H.; Alsulami, T.; Badr, A.N.; Ban, Z.; Farouk, A. Antifungal effect of Algerian essential oil nanoemulsions to control Penicillium digitatum and Penicillium expansum in Thomson Navel oranges (Citrus sinensis L. Osbeck). Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1491491. [CrossRef]

- Maunpuii, C.V.L.; Maisnam, R.; Antuhu, Y.L.; Kumari, A.; López-Menchero, J.R.; González-Coloma, A.; Andrés, M.F.; Kaushik, N. Evaluating the efficiency of essential oils as fumigants in controlling Penicillium digitatum in citrus fruits. BIO Web Conf. 2024, 110, 02009. [CrossRef]

- Maswanganye, L.T.C.; Pillai, S.K.; Sivakumar, D. Chitosan Coating Loaded with Spearmint Essential Oil Nanoemulsion for Antifungal Protection in Soft Citrus (Citrus reticulata) Fruits. Coatings 2025, 15, 105. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Torres, P. Emerging alternatives to control fungal contamination. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2025, 61, 101255. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Alonso, C.O.; Martínez-Romero, D.; Zapata, P.J.; Serrano, M.; Valero, D.; Castillo, S. The effects of essential oils carvacrol and thymol on growth of Penicillium digitatum and P. italicum involved in lemon decay. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 158(2), 101–106. [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999, 26(9-10), 1231–1237. [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28(1), 25–30. [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.C.; Nicholls, P.J. An evaluation of optical density to estimate fungal spore concentrations in water suspensions. Phytopathology 1978, 68(8), 1240–1242. [CrossRef]

- Barnett, H.L.; Hunter, B.B. Illustrated genera of imperfect fungi, 4th ed. APS Press. 1998, 218 pp.

- Pitt, J.I. A Laboratory Guide to Common Penicillium Species, 2nd ed. CSIRO Division of Food Processing, North Ryde, New South Wales, Australia. 1988, 187 pp.

- Romero, C.S. Hongos Fitopatógenos. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Chapingo, Estado de México, México, 1988, 347 pp.

- Bauer, A.W.; Kirby, W.M.M.; Sherris, J.C.; Turck, M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1966, 45, 493–496. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, T.J. Methods for screening and evaluation of antimicrobial activity: A review of protocols, advantages, and limitations. Eur J Microbiol Immunol. 2024, 14(2), 97–115. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2024.

- El Hajli, F.; Chakir, S.; Annemer, S.; Assouguem, A.; Elaissaoui, F.; Ullah, R.; Ali, E.A.; Choudhary, R.; Hammani, K.; Lahlali, R.; Echchgadda, G. Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast.; Mentha pulegium L.; and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation. Open Chem. 2025, 23(1), 20250131. [CrossRef]

- Radi, F.z.; Bouhrim, M.; Mechchate, H.; Al-zahrani, M.; Qurtam, A.A.; Aleissa, A.M.; Drioiche, A.; Handaq, N.; Zair, T. Phytochemical Analysis, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Properties of Thymus zygis L. and Thymus willdenowii Boiss. Essential Oils. Plants 2022, 11, 15. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.J.; Cruz, M.T.; Cavaleiro, C.; Lopes, M.C.; Salgueiro, L. Chemical, antifungal and cytotoxic evaluation of the essential oil of Thymus zygis subsp. sylvestris. Ind. Crops Prod. 2010, 32(1), 70–75. [CrossRef]

- Pina-Vaz, C.; Gonçalves, A.; Pinto, E.; Costa-de-Oliveira, S.; Tavares, C.; Salgueiro, L.; Cavaleiro, C.; Gonçalves, M.J.; Martinez-de-Oliveira, J. Antifungal activity of Thymus oils and their major compounds. JEADV 2004, 18(1), 73–78. [CrossRef]

- Gourich, A.A.; Bencheikh, N.; Bouhrim, M.; Regragui, M.; Rhafouri, R.; Drioiche, A.; Asbabou, A.; Remok, F.; Mouradi, A.; Addi, M.; Hano, C.; Zair, T. Comparative Analysis of the Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of Four Moroccan North Middle Atlas Medicinal Plants’ Essential Oils: Rosmarinus officinalis L.; Mentha pulegium L.; Salvia officinalis L.; and Thymus zygis subsp. gracilis (Boiss.) R. Morales. Chemistry 2022, 4, 1775–1788. [CrossRef]

- Sáez, F. Essential oil variability of Thymus zygis growing wild in southeastern Spain. Phytochemistry 1995, 40(3), 819–825. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, V.; Cabral, C.; Évora, L.; Ferreira, I.; Cavaleiro, C.; Cruz, M.T.; Salgueiro, L. Chemical composition, anti-inflammatory activity and cytotoxicity of Thymus zygis L. subsp. sylvestris (Hoffmanns. & Link) Cout. essential oil and its main compounds. Arab. J. Chem. 2015, 12(8), 3236–3243. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sánchez, R.; Ubera, J.L.; Lafont, F.; Gálvez, C. Composition and Variability of the Essential Oil in Thymus zygis from Southern Spain. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2008, 20(3), 192–200. [CrossRef]

- Šegvić, M.; Kosalec, I.; Mastelić, J.; Piecková, E.; Pepeljnak, S. Antifungal activity of thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) essential oil and thymol against moulds from damp dwellings. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 44(1), 36–42. [CrossRef]

- Golparvar, A.R.; Hadipanah, A. A Review of the Chemical Composition of Essential Oils of Thymus Species in Iran. Research on Crop Ecophysiology 2023, 18(1), 25–51. [CrossRef]

- Etri, K.; Pluhár, Z. Exploring Chemical Variability in the Essential Oils of the Thymus Genus. Plants 2024, 13, 1375. [CrossRef]

- Delgado, T.; Marinero, P.; Asensio-S.-Manzanera, M.C.; Asensio, C.; Herrero, B.; Pereira, J.A.; Ramalhosa, E. Antioxidant activity of twenty wild Spanish Thymus mastichina L. populations and its relation with their chemical composition. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 57(1), 412–418. [CrossRef]

- Macedo, S.; Piçarra, A.; Guerreiro, M.; Salvador, C.; Candeias, F.; Caldeira, A.T.; Martins, M.R. Toxicological and pharmacological properties of essential oils of Calamintha nepeta, Origanum virens and Thymus mastichina of Alentejo (Portugal). Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 133, 110747. [CrossRef]

- Mateus, D.; Costa, F.; de Jesus, V.; Malaquias, L. Biocides Based on Essential Oils for Sustainable Conservation and Restoration of Mural Paintings in Built Cultural Heritage. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11223. [CrossRef]

- Fraternale, D.; Giamperi, L.; Ricci, D. Chemical Composition and Antifungal Activity of Essential Oil Obtained from In Vitro Plants of Thymus mastichina L. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2003, 15(4), 278–281. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Lopes, A.C.; Vaz, F.; Filipe, M.; Alves, G.; Ribeiro, M.P.; Coutinho, P.; Araujo, A.R.T.S. Thymus mastichina: Composition and Biological Properties with a Focus on Antimicrobial Activity. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 479. [CrossRef]

- Diánez, F.; Santos, M.; Parra, C.; Navarro, M.J.; Blanco, R.; Gea, F.J. Screening of antifungal activity of 12 essential oils against eight pathogenic fungi of vegetables and mushroom. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 67, 400–410. [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.M.; Lopes, V.; Barata, A.M.; Póvoa, O.; Farinha, N.; Figueiredo, A.C. Essential Oils from Origanum vulgare subsp. virens (Hoffmanns. & Link) Ietsw. Grown in Portugal: Chemical Diversity and Relevance of Chemical Descriptors. Plants 2023, 12, 621. [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Shakeri, A.; Iranshahi, M.; Boozari, M. A Review of the Phytochemistry and Antimicrobial Properties of Origanum vulgare L. and Subspecies. Iran J. Pharm. Res. 2001, 20(2), 268–285. [CrossRef]

- Arras, G.; Usai, M. Fungitoxic Activity of 12 Essential Oils against Four Postharvest Citrus Pathogens: Chemical Analysis of Thymus capitatus Oil and its Effect in Subatmospheric Pressure Conditions. J. Food Prot. 2001, 64(7), 1025–1029. [CrossRef]

- Kocić-Tanackov, S.D.; Dimić, G.R.; Tanackov, I.J.; Pejin, D.J.; Mojović, L.V.; Pejin, J.D. Antifungal activity of Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) extract on the growth of Fusarium and Penicillium species isolated from food. Hem. Ind. 2012, 66(1), 33–41. [CrossRef]

- Zulu, L.; Gao, H.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, H.; Xie, Y.; Liu, X.; Yao, H.; Rao, Q. Antifungal effects of seven plant essential oils against Penicillium digitatum. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 82. [CrossRef]

- Vitoratos, A.; Bilalis, D.; Karkanis, A.; Efthimiadou, A. Antifungal Activity of Plant Essential Oils Against Botrytis cinerea, Penicillium italicum and Penicillium digitatum. Not. Bot. Horti. Agrobo. 2013, 41(1), 86–92. [CrossRef]

- Domingues, J.; Goulão, M.; Delgado, F.; Gonçalves, J.C.; Gonçalves, J.; Pintado, C.S. Essential Oils of Two Portuguese Endemic Species of Lavandula as a Source of Antifungal and Antibacterial Agents. Processes 2023, 11, 1165. [CrossRef]

- Pombal, S.; Rodrigues, C.F.; Araújo, J.P.; Rocha, P.M.; Rodilla, J.M.; Diez, D.; Granja, Á.P.; Gomes, A.C.; Silva, L.A. Antibacterial and antioxidant activity of Portuguese Lavandula luisieri (Rozeira) Rivas-Martinez and its relation with their chemical composition. SpringerPlus. 2016, 5(1), 1711. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A.K.; Malik, A. Antimicrobial potential and chemical composition of Mentha piperita oil in liquid and vapour phase against food spoiling microorganisms. Food Control 2011, 22(11), 1707–1714. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, D.N.; Al-Rajab, A.J.; Sharma, M.; Moses, M.M.; Reddy, G.R.; Albratty, M. Chemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial and antifungal activity of Mentha × Piperita L. (peppermint) essential oils. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2019, 31(4), 528–533. [CrossRef]

- Zamanian, Z.; Bonyadian, M.; Moshtaghi, H.; Ebrahimi, A. Antifungal effects of essential oils of Zataria multiflora, Mentha pulegium, and Mentha piperita. J. Food Qual. Hazards Control. 2021, 8, 41–44. [CrossRef]

- Kgang, I.E.; Mathabe, P.M.K.; Klein, A.; Kalombo, L.; Belay, Z.A.; Caleb, O.J. Effects of lemon (Citrus Limon L.), lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) and peppermint (Mentha piperita L.) essential oils against of Botrytis cinerea and Penicillium expansum. JSFA Reports 2022, 2, 405–414. [CrossRef]

| Specie | Code | Yield (w/w) | % (w/w) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origanum vulgare subsp. virens | OVV | 4.09 | 0.41 |

| Lavandula pedunculata subsp. sampaioana | LPS | 12.80 | 1.28 |

| Lavandula stoechas subsp. luisieri | LSL | 4.22 | 0.42 |

| Thymus zygis subsp. sylvestris | TZS | 8.78 | 0.88 |

| Thymus mastichina | TM | 24.29 | 2.43 |

| Mentha × piperita | MP | 6.17 | 0.62 |

| RI-WAX | RI-HP5 | Compound | OVV | LPS | LSL | TM | TZS | MP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1025 | 933 | Alpha-Pinene | 0.67 | 6.35 | 1.83 | 3.44 | 0.51 | 0.74 |

| 1029 | 918 | Alpha-Thujene | 1.63 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 1.32 | 0.06 | |

| 1069 | 953 | Camphene | 0.29 | 2.29 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.02 |

| 1114 | 978 | Beta-Pinene | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 5.11 | 0.13 | 1.17 |

| 1126 | 972 | Sabinene | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 3.83 | 0.07 | 0.67 |

| 1133 | 940 | Cymene Isomer | 2.67 | |||||

| 1165 | 991 | Beta-Myrcene | 2.28 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 1.87 | 1.91 | 0.33 |

| 1186 | 1018 | Alpha-Terpinene | 3.76 | 0.03 | 1.33 | 0.26 | ||

| 1206 | 1021 | Limonene | 0.35 | 2.03 | 0.20 | 1.17 | 0.32 | 3.42 |

| 1222 | 1039 | 1,8-Cineole | 0.02 | 0.93 | 17.71 | 66.06 | 6.72 | |

| 1238 | 1035 | Cis-Beta-Ocimene | 2.15 | 0.15 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.27 |

| 1254 | 1058 | Gamma-Terpinene | 30.69 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 1.79 | 5.72 | 0.41 |

| 1278 | 1025 | Para-Cymene | 5.26 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 1.03 | 9.36 | 0.08 |

| 1418 | 1090 | Fenchone | 34.20 | 0.28 | ||||

| 1465 | 1074 | Trans-Sabinene Hydrate | 0.16 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.82 | ||

| 1484 | 1124 | Menthone | 29.12 | |||||

| 1500 | 1164 | Menthofuran | 4.94 | |||||

| 1510 | 1166 | Isomenthone | 4.31 | |||||

| 1541 | 1149 | Camphor | 36.51 | 1.00 | ||||

| 1553 | 1100 | Linalool | 0.16 | 2.00 | 2.29 | 4.14 | 0.86 | 0.26 |

| 1574 | 1294 | Menthyl Acetate | 2.36 | |||||

| 1592 | 1239 | Thymol Methyl Ether | 1.88 | 0.01 | ||||

| 1595 | 1119 | Fenchol<endo-> | 0.86 | |||||

| 1599 | 1288 | Bornyl Acetate | 0.98 | 0.06 | <0,01 | |||

| 1606 | 1280 | Trans-Alpha-Necrodyl Acetate | 20.46 | |||||

| 1607 | 1239 | Carvacrol Methyl Ether | 2.38 | 0.05 | ||||

| 1608 | 1165 | Neo-Menthol | 4.11 | |||||

| 1617 | 1450 | Trans-Beta Caryophyllene | 1.61 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 1.41 | 1.18 |

| 1619 | 1284 | Lavandulyl Acetate | 0.20 | 4.01 | ||||

| 1636 | 1296 | Arbozol | 2.24 | |||||

| 1653 | 1169 | L-Menthol | 27.56 | |||||

| 1662 | 1170 | Delta-Terpineol | 1.50 | 0.22 | ||||

| 1665 | 1244 | Pulegone | 3.98 | |||||

| 1668 | 1187 | 5-Methylene-2,3,4,4-tetrame-2-Cyclopentenone | 2.37 | |||||

| 1860 | Unknown Sesquiterpenol | 2.06 | ||||||

| 1679 | 1172 | Trans-Alpha-Necrodol | 6.56 | |||||

| 1696 | 1195 | Alpha-Terpineol | 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 4.86 | 0.13 | 0.44 |

| 1713 | 1167 | Borneol | 0.65 | 0.78 | 0.12 | 0.34 | 0.02 | |

| 2168 | 1293 | Thymol | 36.72 | 68.83 | 0.08 | |||

| 2192 | 1316 | Carvacrol | 0.28 | 0.17 | 2.54 |

| Code | ABTS | DPPH | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mM TROLOX eq. | g TROLOX eq. / g EO | mM TROLOX eq. | g TROLOX eq. / g EO | |

| OVV | 76.45 ± 3.02 | 433.01 ± 17.10 | 25.15 ± 1.69 | 142.45 ± 9.57 |

| LPS | 3.84 ± 0.26 | 20.79 ± 1.41 | 2.17 ± 0.16 | 11.73 ± 0.87 |

| LSL | 24.06 ± 0.64 | 131.33 ± 3.47 | 33.91 ± 1.21 | 184.99 ± 6.58 |

| TM | 9.76 ± 0.41 | 54.19 ± 2.30 | 0.96 ± 0.03 | 5.31 ± 0.16 |

| TZS | 161.70 ± 0.15 | 864.20 ± 0.81 | 25.34 ± 1.08 | 135.42 ± 5.78 |

| MP | 4.83 ± 0.09 | 26.94 ± 0.51 | 3.83 ± 0.13 | 21.34 ± 0.74 |

| EO | x̅ | s | Me | Max | Min | SEM | g₁ | g₂ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. digitatum | ||||||||

| OVV | 31.33 | 3.21 | 30.00 | 35.00 | 29.00 | 1.86 | 0.34 | -2.33 |

| LPS | 20.17 | 3.25 | 20.00 | 23.50 | 17.00 | 1.88 | 0.05 | -2.33 |

| LSL | 30.67 | 1.15 | 30.00 | 32.00 | 30.00 | 0.67 | 0.38 | -2.33 |

| TM | 16.17 | 0.29 | 16.00 | 16.50 | 16.00 | 0.17 | 0.38 | -2.33 |

| TZS | 60.50 | 5.77 | 60.00 | 66.50 | 55.00 | 3.33 | 0.09 | -2.33 |

| MP | 19.33 | 3.21 | 18.00 | 23.00 | 17.00 | 1.86 | 0.34 | -2.33 |

| P. italicum | ||||||||

| OVV | 27.00 | 6.38 | 28.50 | 32.50 | 20.00 | 3.69 | -0.22 | -2.33 |

| LPS | 14.17 | 0.76 | 14.00 | 15.00 | 13.50 | 0.44 | 0.21 | -2.33 |

| LSL | 37.33 | 2.52 | 37.00 | 40.00 | 35.00 | 1.45 | 0.13 | -2.33 |

| TM | 13.67 | 1.26 | 13.50 | 15.00 | 12.50 | 0.73 | 0.13 | -2.33 |

| TZS | 54.33 | 2.93 | 55.50 | 56.50 | 51.00 | 1.69 | -0.34 | -2.33 |

| MP | 20.33 | 3.06 | 21.00 | 23.00 | 17.00 | 1.76 | -0.21 | -2.33 |

| variables | W | p-value | W | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. digitatum | P. italicum | |||

| inhibition halo (mm) | 0.80130 | 0.00159 | 0.86399 | 0.01418 |

| ABTS (mM) | 0.72045 | 0.00014 | 0.72045 | 0.00014 |

| ABTS (g) | 0.72651 | 0.00017 | 0.72709 | 0.00017 |

| DPPH (mM) | 0.79313 | 0.00122 | 0.79468 | 0.00122 |

| DPPH (g) | 0.79468 | 0.00128 | 0.79468 | 0.00128 |

| variables | S | p-value | ρ | S | p-value | ρ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. digitatum | P. italicum | |||||

| ABTS (mM) | 245.38 | 3.70 · 10-4 | 0.75 | 247.88 | 3.98 · 10-4 | 0.74 |

| ABTS (g) | 235.35 | 2.75 · 10-4 | 0.76 | 247.88 | 3.98 · 10-4 | 0.74 |

| DPPH (Mm) | 232.34 | 2.51 · 10-4 | 0.76 | 176.77 | 3.42 · 10-5 | 0.82 |

| DPPH (g) | 238.36 | 3.01 · 10-4 | 0.75 | 194.80 | 6.98 · 10-5 | 0.80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).