Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ciliate Strain and Culture Conditions

2.2. Metal Salts (Chemicals)

2.3. Toxicity Tests with Single Metals (Cd, Cu, and Zn)

2.4. Cytotoxicity Bioassays with Bimetallic Mixtures (Cd + Zn, Cu + Zn, and Cd + Cu)

2.5. Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity Assays

2.6. Estimation of Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

2.7. DPPH Scavenging Assay

2.8. Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Assay (HRSA)

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

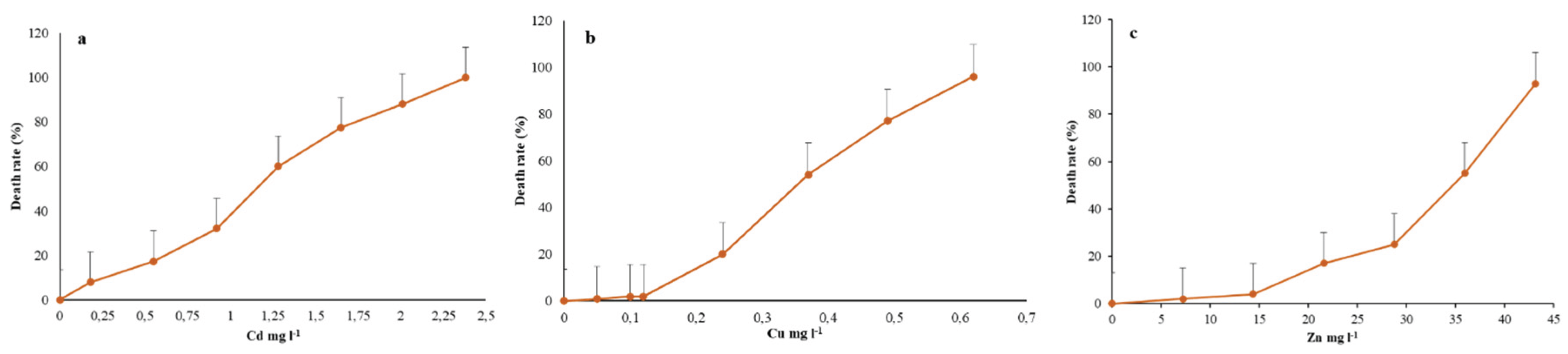

3.1. Cytotoxicity of Single Metals (Cd, Cu and Zn)

3.2. Cytotoxicity of Bimetallic Mixtures (Cd + Zn, Cu + Zn and Cd + Cu)

3.3. Antioxidants Properties of R. tetracirrata Extracts Treated with Cd, Cu, Zn, and Cd +Zn

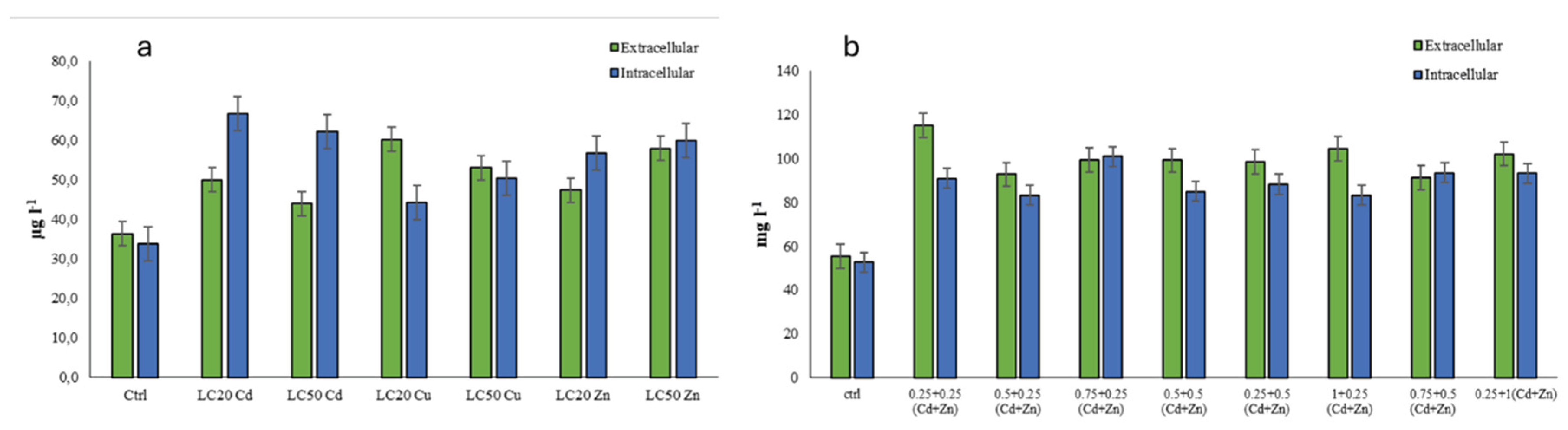

3.3.1. Total Phenolic Content (TPC) from Extracts of R. tetracirrata

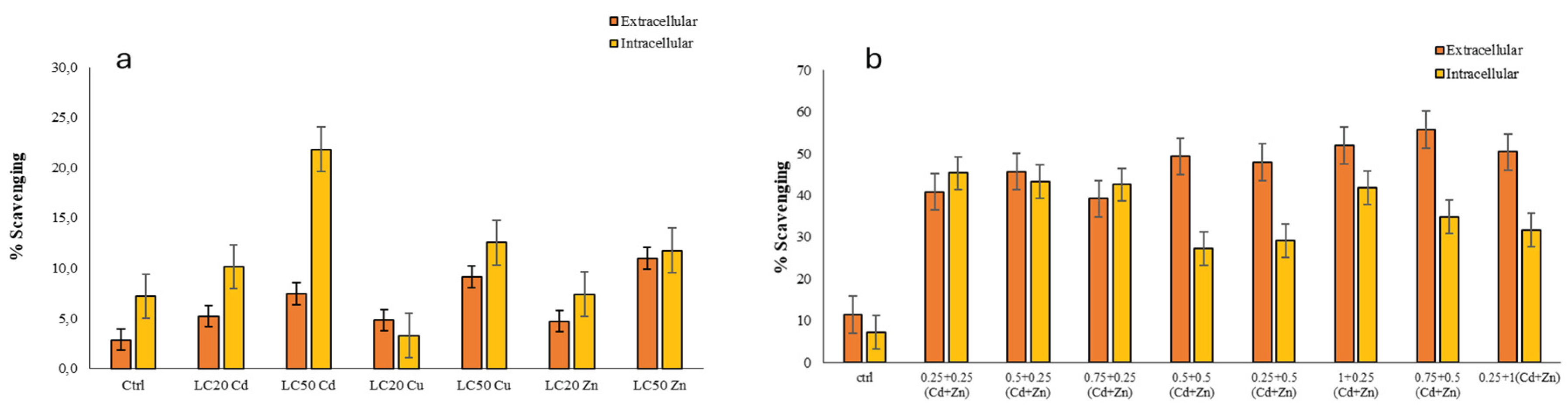

3.3.2. DPPH Scavenging Activity from Extracts of R. tetracirrata

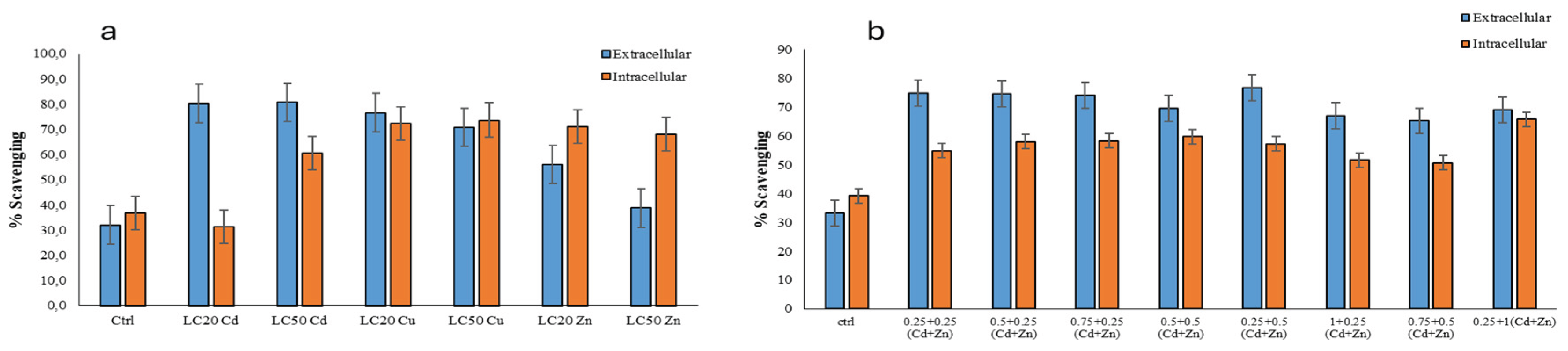

3.3.3. Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Activity of Extracts of R. tetracirrata

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Calisi, A., Cappello, T., Angelelli, M., Maisano, M., Rotondo, D., Gualandris, D., Semeraro, T., Dondero, F. (2024). Non-Destructive Biomarkers in Non-Target Species Earthworm Lumbricus terrestris for Assessment of Different Agrochemicals. Environments, 11, 276. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Hernandez, J.C. (2019). Bioremediation of Agricultural Soils, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; p. 296, ISBN 9780367780173.

- Järup, L. (2003) Hazards of heavy metal contamination. British medical bulletin, 68(61), 167-182.

- Wuana, R.A., and Felix E. Okieimen (2011). Heavy metals in contaminated soils: a review of sources, chemistry, risks and best available strategies for remediation. Isrn Ecology, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Calisi, A., Semeraro, T., Giordano, M.E., Dondero, F., Lionetto, M.G. (2025) Earthworms multi-biomarker approach for ecotoxicological assessment of soils irrigated with reused treated wastewater. Applied Soil Ecology, 206, 105866. [CrossRef]

- Michaela, F. (2010) The influence of heavy metals on soil biological and chemical properties. Soil Water Research, 5, no. 1: 21-27.

- Bååth, E. (1989) Effects of heavy metals in soil on microbial processes and populations (a review). Water, Air, and Soil Pollution, 47,43-44: 335-379. [CrossRef]

- Giller, K.E., Ernst Witter, and Steve P. Mcgrath (1998). Toxicity of heavy metals to microorganisms and microbial processes in agricultural soils: a review. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 30(10): 1389-1414. [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.W.; Magos, L.; Suzuki, T. (1996). Toxicology of metals; CRC Boca Raton, FL.

- Xin, Z.; Wenchao, Z.; Zhenguang, Y.; Yiguo, H.; Zhengtao, L.; Xianliang, Y.; Xiaonan, W.; Tingting, L.; Liming, Z. (2015) Species sensitivity analysis of heavy metals to freshwater organisms. Ecotoxicology, 24, 1621-1631. [CrossRef]

- Schuler, M.S.; Relyea, R.A. (2018). A review of the combined threats of road salts and heavy metals to freshwater systems. BioScience, 68, 327-335. [CrossRef]

- Vilas–Boas, J.A.; Cardoso, S.J.; Senra, M.V.X.; Rico, A.; Dias, R.J.P. (2020). Ciliates as model organisms for the ecotoxicological risk assessment of heavy metals: a meta-analysis. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety, 199, 110669. [CrossRef]

- Fountain, M.T.; Hopkin, S.P. (2005). Folsomia candida (Collembola): a “standard” soil arthropod. Annuals Review of Entomology, 50, 201-222.

- Filser, J.; Wiegmann, S.; Schröder, B. (2014). Collembola in ecotoxicology—Any news or just boring routine? Applied Soil Ecology, 83, 193-199.

- Kammenga, J.E.; Dallinger, R.; Donker, M.H.; Köhler, H.; Simonsen, V.; Triebskorn, R.; Weeks, J.M. (2000) Biomarkers in terrestrial invertebrates for ecotoxicological soil risk assessment. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 164, 93-147.

- Dallinger, R.; Berger, B.; Triebskorn-Köhler, R.; Köhler, H. (2001) Soil biology and ecotoxicology. In The biology of terrestrial molluscs; CABI Wallingford UK; pp. 489-525.

- Bharti, D.; Kumar, S.; La Terza, A. (2016) Rigidosticha italiensis (Ciliophora, Spirotricha), a novel large hypotrich ciliate from the soil of Lombardia, Italy. European Journal of Protistology, 56, 112-118. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kamra, K.; Bharti, D.; La Terza, A.; Sehgal, N.; Warren, A.; Sapra, G.R. (2015) Morphology, morphogenesis, and molecular phylogeny of Sterkiella tetracirrata (Ciliophora, Oxytrichidae), from the Silent Valley National Park, India. European Journal of Protistology, 51,86-97.

- Warren, A.; Patterson, D.J.; Dunthorn, M.; Clamp, J.C.; et al. (2017) Beyond the “Code”: A Guide to the Description and Documentation of Biodiversity in Ciliated Protists (Alveolata, Ciliophora). The journal of eukaryotic microbiology, 64, 539-554.

- Fenchel, T. (2013) Ecology of Protozoa: The biology of free-living phagotropic protists; Springer-Verlag.

- Jiang, J.-G.; Wu, S.-G.; Shen, Y.-F. (2007). Effects of seasonal succession and water pollution on the protozoan community structure in an eutrophic lake. Chemosphere, 66, 523-532. [CrossRef]

- Weisse, T. (2017). Functional diversity of aquatic ciliates. European Journal of Protistology, 61, 331-358. [CrossRef]

- Geisen, S.; Mitchell, E.A.D.; Wilkinson, D.M.; Adl, S.; et al., (2017). Soil protistology rebooted: 30 fundamental questions to start with, Soil Biology and Biochemistry,111, 94-103. [CrossRef]

- Bonkowski, M.; Clarholm, M. (2015). Stimulation of plant growth through interactions of bacteria and protozoa: testing the auxiliary microbial loop hypothesis. Acta Protozool., 51, 237-247.

- Gualandris, D.; Rotondo, D.; Lorusso, C.; La Terza, A.; Calisi, A.; Dondero, F. (2024) The Metallothionein System in Tetrahymena thermophila Is Iron-Inducible. Toxics, 12, 725. [CrossRef]

- Fulgentini, L.; Passini, V.; Colombetti, G.; Miceli, C.; La Terza, A.; Marangoni, R. (2015). UV-radiation and visible light induce hsp70 genes expression in the Antarctic psycrophilic ciliate Euplotes focardii. Microbial Ecology, 70, 372-379. [CrossRef]

- La Terza, A.; Barchetta, S.; Buonanno, F.; Ballarini, P.; Miceli, C. (2008). The protozoan ciliate Tetrahymena thermophila as biosensor of sublethal levels of toxicants in the soil. Fresenius Environmental Bulletin, 17, 1144-1150.

- Bharti, D.; Kumar, S.; Basuri, C.K.; La Terza, A. (2024). Ciliated Protist Communities in Soil: Contrasting Patterns in Natural Sites and Arable Lands across Italy. Soil System, 8, 64. [CrossRef]

- Delmonte Corrado, M.; Trielli, F.; Amaroli, A.; Ognibene, M.; Falugi, C. (2005). Protists as tools for environmental biomonitoring: im-portance of cholinesterase enzyme activities. Water Poll. New Res., 1, 181-200.

- Gilron, G.L.; Lynn, D.H. (2018). Ciliated protozoa as test organisms in toxicity assessments. In Microscale testing in aquatic toxicology; CRC Press; pp. 323-336.

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J.M. (1986). Oxygen free radicals and iron in relation to biology and medicine: some problems and concepts. Arch. Biochem. Biophys, 246, 501-514. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-b.; Qu, G.-b.; Cao, M.-x.; Liang, Y.; Hu, L.-g.; Shi, J.-b.; Cai, Y.; Jiang, G.-b. (2017). Distinct toxicological characteristics and mechanisms of Hg2+ and MeHg in Tetrahymena under low concentration exposure. Aquatic Toxicology, 193, 152-159. [CrossRef]

- Varatharajan, G.R.; Calisi, A.; Kumar, S.; Bharti, D.; Dondero, F.; La Terza, A. (2024) Cytotoxicity and Antioxidant Defences in Euplotes aediculatus Exposed to Single and Binary Mixtures of Heavy Metals and Nanoparticles. Appl. Sci., 14, 5058. [CrossRef]

- Bharti, D.; Kumar, S.; La Terza, A. (2017). Description and molecular phylogeny of a novel hypotrich ciliate from the soil of Marche Region, Italy; including notes on the MOSYSS Project. Journal of Eukariotic Microbiology, 64,678-690. [CrossRef]

- Chapman-Andresen, C. (1958). Pinocytosis of inorganic salts by Amoeba proteus (Chaos diffluens). Comptes rendus des travaux du Laboratoire Carlsberg. Serie chimique, 31, 77.

- Strober, W. (2001). Trypan blue exclusion test of cell viability. Current protocols in immunology, A3. B. 1-A3. B. 3.

- Gallego, A., Martín-González, A., Ortega, R., Gutiérrez, J. C. (2007). Flow cytometry assessment of cytotoxicity and reactive oxygen species generation by single and binary mixtures of cadmium, zinc and copper on populations of the ciliated protozoan Tetrahymena thermophila. Chemosphere 68(64), 647-661. [CrossRef]

- Sprague, J. (1970). Measurement of pollutant toxicity to fish. II. Utilizing and applying bioassay results. Water Research, 4, 3-32. [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, C.; Varatharajan, G.R.; Rajasabapathy, R.; Vijayakanth, S.; Kumar, A.H.; Meena, R.M. (2012). A role for antioxidants in acclimation of marine derived pathogenic fungus (NIOCC 1) to salt stress. Microbial pathogenesis, 53, 168-179. [CrossRef]

- Vattem, D.A.; Shetty, K. (2002). Solid-state production of phenolic antioxidants from cranberry pomace by Rhizopus oligosporus. Food Biotechnology, 16, 189-210. [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, A.; Mavi, A.; Kara, A.A. (2001). Determination of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Rumex crispus L. extracts. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 49, 4083-4089.

- Kunchandy, E.; Rao, M. (1990). Oxygen radical scavenging activity of curcumin. International journal of pharmaceutics, 58, 237-240. [CrossRef]

- Lorusso, C.; Calisi, A.; Sanchez-Hernandez, J.C.; Varodi, C.; Pogăcean, F.; Pruneanu, S.; Dondero, F. (2022). Carbon nanomaterial functionalization with pesticide-detoxifying carboxylesterase. Chemosphere, 309, 136594. [CrossRef]

- Kong, R.; Sun, Q.; Cheng, S.; Fu, J.; Liu, W.; Letcher, R.J.; Liu, C. (2021). Uptake, excretion and toxicity of titanate nanotubes in three stains of free-living ciliates of the genus Tetrahymena. Aquatic Toxicology, 233, 105790. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Martín-González, A.; Gutiérrez, J.C. (2006). Evaluation of heavy metal acute toxicity and bioaccumulation in soil ciliated protozoa. Environment international, 32, 711-717. [CrossRef]

- Luu, H.T.; Esteban, G.F.; Butt, A.A.; Green, I.D. (2022). Effects of Copper and the Insecticide Cypermethrin on a Soil Ciliate (Protozoa: Ciliophora) Community. Protist, 173, 125855. [CrossRef]

- Madoni, P.; Romeo, M.G. (2006). Acute toxicity of heavy metals towards freshwater ciliated protists. Environmental Pollution, 141(141), 141-147. [CrossRef]

- Martín-González, A., Díaz, S., Borniquel, S., Gallego, A., & Gutiérrez, J. C. (2006). Cytotoxicity and bioaccumulation of heavy metals by ciliated protozoa isolated from urban wastewater treatment plants. Research in microbiology, 157(152), 108-118. [CrossRef]

- Echavez, F.L.C.; Leal, J.C.M. (2021). Ecotoxicological effect of heavy metals in free-living ciliate protozoa of Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela. Journal of Water and Land Development, 102-116-102-116. [CrossRef]

- Marín-Leal, J.C.; Rincón-Miquilena, N.J.; Díaz-Borrego, L.C.; Pire-Sierra, M.C. (2022). Acute toxicity of potentially toxic elements on ciliated protozoa from Lake Maracaibo (Venezuela). Acta Limnologica Brasiliensia, 34, e21. [CrossRef]

- Fargašová, A. (2001). Winter third-to fourth-instar larvae of Chironomus plumosus as bioassay tools for assessment of acute toxicity of metals and their binary combinations. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 48, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Ince, N.; Dirilgen, N.; Apikyan, I.; Tezcanli, G.; Üstün, B. (1999) Assessment of toxic interactions of heavy metals in binary mixtures: a statistical approach. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 36, 365-372. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y. (1995) Reciprocal effect of Cu, Cd, Zn on a kind of marine alga. Water Research, 29, 209-214.

- Negilski, D.; Ahsanullah, M.; Mobley, M. (1981). Toxicity of zinc, cadmium and copper to the shrimp Callianassa australiensis. II. Effects of paired and triad combinations of metals. Marine Biology, 64, 305-309. [CrossRef]

- Otitoloju, A.A. (2002). Evaluation of the joint-action toxicity of binary mixtures of heavy metals against the mangrove periwinkle Tympanotonus fuscatus var radula (L.). Ecotoxicology and Environmental safety, 53, 404-415. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.; Templeton, D.M.; O’Brien, P.J. (2006). Mitochondrial involvement in genetically determined transition metal toxicity: II. Copper toxicity. Chemico-biological interactions, 163, 77-85. [CrossRef]

- Norwood, W.; Borgmann, U.; Dixon, D.; Wallace, A. (2003) Effects of metal mixtures on aquatic biota: a review of observations and methods. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment, 9, 795-811. [CrossRef]

- Hajdú, Z.; Hohmann, J.; Forgo, P.; Martinek, T.; Dervarics, M.; Zupkó, I.; Falkay, G.; Cossuta, D.; Máthé, I. (2007). Diterpenoids and flavonoids from the fruits of Vitex agnus-castus and antioxidant activity of the fruit extracts and their constituents. Phytotherapy Research, 21, 391-394. [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, A.; Mavi, A.; Oktay, M.; Kara, A.A.; Algur, Ö.F.; Bilaloǧlu, V. (2000). Comparison of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Tilia (Tilia argentea Desf ex DC), sage (Salvia triloba L.), and Black tea (Camellia sinensis) extracts. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 48, 5030-5034.

- Uddin, G.; Rauf, A.; Arfan, M.; Ali, M.; Qaisar, M.; Saadiq, M.; Atif, M. (2012). Preliminary phytochemical screening and antioxidant activity of Bergenia caliata. Middle-East J. Sci. Res, 11, 1140-1142.

- Horta, A.; Pinteus, S.; Alves, C.; Fino, N.; Silva, J.; Fernandez, S.; Rodrigues, A.; Pedrosa, R. (2014). Antioxidant and antimicrobial potential of the Bifurcaria bifurcata epiphytic bacteria. Marine drugs, 12, 1676-1689. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. (1991) Reactive oxygen species in living systems: source, biochemistry, and role in human disease. The American journal of medicine, 91, S14-S22.

- Sharma, P.; Ravikumar, G.; Kalaiselvi, M.; Gomathi, D.; Uma, C. (2013) In vitro antibacterial and free radical scavenging activity of green hull of Juglans regia. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis, 3, 298-302. [CrossRef]

- Boldrin, F.; Santovito, G.; Gaertig, J.; Wloga, D.; Cassidy-Hanley, D.; Clark, T.G.; Piccinni, E. (2006). Metallothionein gene from Tetrahymena thermophila with a copper-inducible-repressible promoter. Eukaryotic cell, 5, 422-425. [CrossRef]

- Santovito, G.; Formigari, A.; Boldrin, F.; Piccinni, E. (2007). Molecular and functional evolution of Tetrahymena metallothioneins: New insights into the gene family of Tetrahymena thermophila. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology, 144, 391-397. [CrossRef]

- Ferro, D.; Bakiu, R.; De Pittà, C.; Boldrin, F.; Cattalini, F.; Pucciarelli, S.; Miceli, C.; Santovito, G. (2015). Cu, Zn superoxide dismutases from Tetrahymena thermophila: molecular evolution and gene expression of the first line of antioxidant defenses. Protist, 166, 131-145. [CrossRef]

| S. No. | Heavy Metals | LC20 (mg l-1) | LC50 (mg l-1) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Cd | 0.53 | 1.16 | 0.978 |

| 2 | Cu | 0.22 | 0.37 | 0.990 |

| 3. | Zn | 23.0 | 32.7 | 0.919 |

| Cd + Zn Total TUa |

Concentrations (TU)a for each metal Cd Zn |

Obtained Cytotoxicityb | Expected Cytotoxicity | Interaction type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 12.77 | ± | 2.54 | 18 | Not significant different |

| 0.25 | 0.25 | 6.07 | ± | 2.54 | 13 | Antagonism | |

| 0 | 0.5 | 3.87 | ± | 0.98 | 4 | Not significant different | |

| 0.75 | 0.75 | 0 | 29.40 | ± | 3.48 | 30 | Not significant different |

| 0.5 | 0.25 | 4.97 | ± | 1.65 | 20 | Antagonism | |

| 0.25 | 0.5 | 18.83 | ± | 2.54 | 15 | Not significant different | |

| 0 | 0.75 | 16.63 | ± | 1.65 | 18 | Not significant different | |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 49.97 | ± | 1.65 | 50 | Not significant different |

| 0.75 | 0.25 | 22.20 | ± | 2.55 | 32 | Antagonism | |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 3.87 | ± | 0.98 | 22 | Antagonism | |

| 0.25 | 0.75 | 8.87 | ± | 0.98 | 29 | Antagonism | |

| 0 | 1 | 49.43 | ± | 0.98 | 50 | Not significant different | |

| 1.25 | 1.25 | 0 | 61.07 | ± | 2.54 | 68 | Not significant different |

| 1 | 0.25 | 33.30 | ± | 1.70 | 52 | Antagonism | |

| 0.75 | 0.5 | 45.53 | ± | 3.87 | 34 | Synergism | |

| 0.5 | 0.75 | 32.77 | ± | 2.54 | 36 | Not significant different | |

| 0.25 | 1 | 14.97 | ± | 1.65 | 61 | Antagonism | |

| 0 | 1.25 | 77.77 | ± | 2.54 | 82 | Not significant different | |

| Cu + Zn Total TUa |

Concentrations (TU)a for each metal Cu Zn |

Obtained Cytotoxicityb | Expected Cytotoxicity | Interaction type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 12.17 | ± | 0.98 | 11 | Not significant different |

| 0.25 | 0.25 | 4.43 | ± | 0.98 | 4 | Not significant different | |

| 0 | 0.5 | 6.07 | ± | 2.54 | 4 | Not significant different | |

| 0.75 | 0.75 | 0 | 28.30 | ± | 1.70 | 30 | Not significant different |

| 0.5 | 0.25 | 6.07 | ± | 2.54 | 13 | Antagonism | |

| 0.25 | 0.5 | 9.97 | ± | 1.65 | 6 | Synergism | |

| 0 | 0.75 | 20.50 | ± | 1.91 | 18 | Not significant different | |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 48.83 | ± | 2.54 | 50 | Not significant different |

| 0.75 | 0.25 | 34.93 | ± | 2.89 | 32 | Not significant different | |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 11.63 | ± | 3.35 | 15 | Not significant different | |

| 0.25 | 0.75 | 23.87 | ± | 0.98 | 20 | Synergism | |

| 0 | 1 | 52.20 | ± | 1.91 | 50 | Not significant different | |

| 1.25 | 1.25 | 0 | 69.40 | ± | 2.55 | 71 | Not significant different |

| 1 | 0.25 | 31.63 | ± | 1.65 | 52 | Antagonism | |

| 0.75 | 0.5 | 28.87 | ± | 4.18 | 34 | Not significant different | |

| 0.5 | 0.75 | 32.77 | ± | 2.54 | 29 | Not significant different | |

| 0.25 | 1 | 72.77 | ± | 2.54 | 52 | Synergism | |

| 0 | 1.25 | 80.53 | ± | 2.54 | 82 | Not significant different | |

| Cd + Cu Total TUa |

Concentrations (TU)a for each metal Cd Cu |

Obtained Cytotoxicityb | Expected Cytotoxicity | Interaction type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 16.10 | ± | 1.91 | 18 | Not significant different |

| 0.25 | 0.25 | 10.53 | ± | 2.54 | 13 | Not significant different | |

| 0 | 0.5 | 13.87 | ± | 0.98 | 11 | Not significant different | |

| 0.75 | 0.75 | 0 | 28.87 | ± | 3.44 | 30 | Not significant different |

| 0.5 | 0.25 | 13.87 | ± | 7.86 | 20 | Antagonism | |

| 0.25 | 0.5 | 20.53 | ± | 0.92 | 22 | Not significant different | |

| 0 | 0.75 | 32.77 | ± | 2.54 | 30 | Not significant different | |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 49.40 | ± | 3.48 | 50 | Not significant different |

| 0.75 | 0.25 | 34.97 | ± | 1.65 | 32 | Synergism | |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 38.83 | ± | 2.54 | 29 | Synergism | |

| 0.25 | 0.75 | 44.40 | ± | 2.55 | 41 | Synergism | |

| 0 | 1 | 48.83 | ± | 2.54 | 50 | Not significant different | |

| 1.25 | 1.25 | 0 | 72.20 | ± | 2.55 | 68 | Not significant different |

| 1 | 0.25 | 55.50 | ± | 3.48 | 52 | Not significant different | |

| 0.75 | 0.5 | 34.40 | ± | 3.81 | 41 | Antagonism | |

| 0.5 | 0.75 | 45.53 | ± | 2.54 | 48 | Not significant different | |

| 0.25 | 1 | 84.97 | ± | 1.65 | 61 | Synergism | |

| 0 | 1.25 | 73.87 | ± | 1.96 | 71 | Not significant different | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).