Submitted:

28 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Approval Number and Name of the Committee

2.2. Cell Lines and Reagents

2.3. Probiotic Bacteria AJ2 Sonication

2.4. Purification of Human NK Cells and Monocytes

2.5. Generation of Osteoclasts and Supercharging of NK Cells

2.6. Tumor Implantation, sNK Cells Infusions, and AJ2 Fed in hu-BLT Mice

2.7. Cell Isolation and Cultures of hu-BLT Mice Tissue Samples

2.8. Isolation of hu-BLT Mice Spleen NK Cells

2.9. Bone Analysis

2.10. Histology and Quantitative Histomorphometry

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

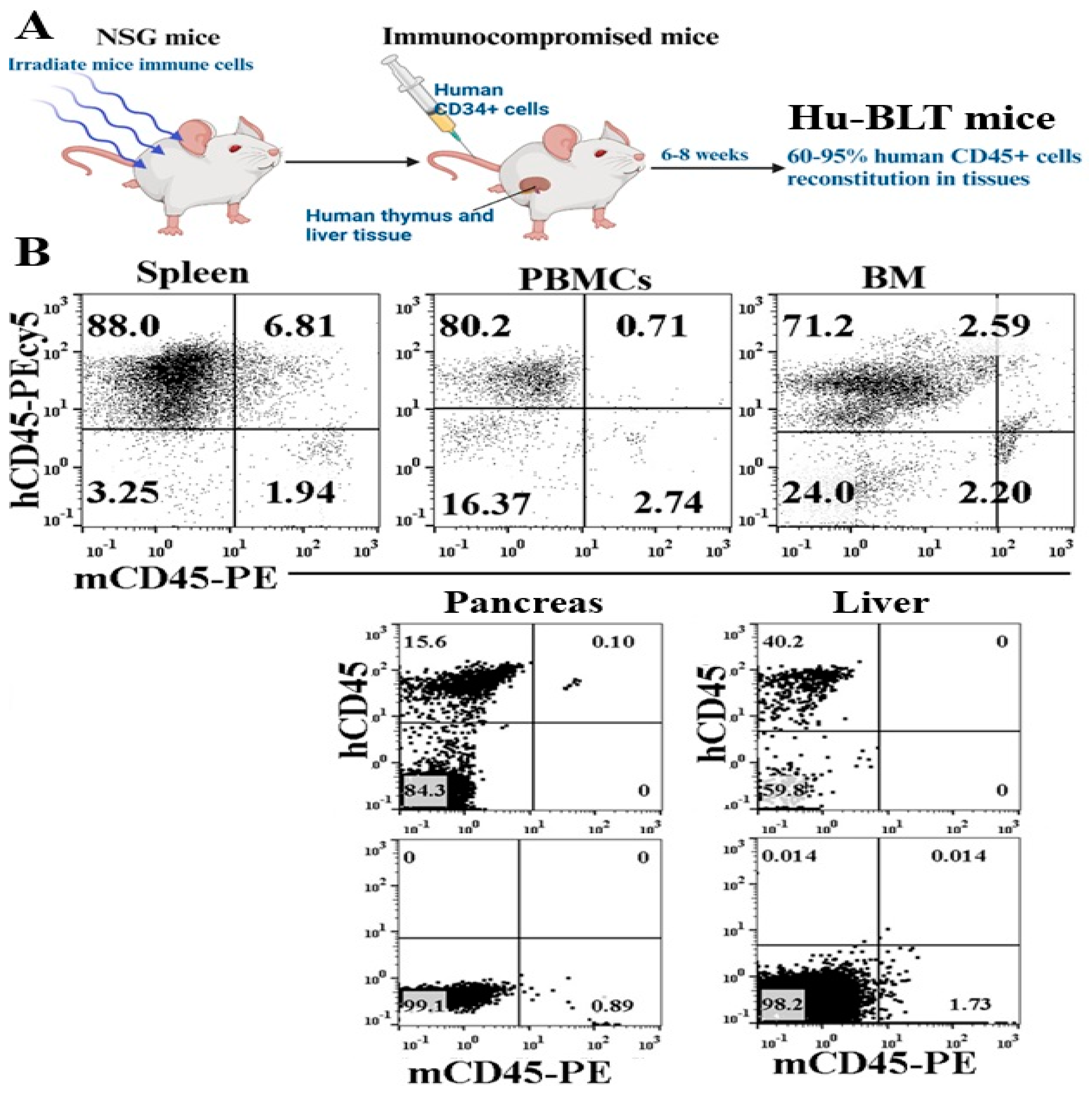

3.1. Successful Reconstitution of Human CD45+ Immune Cells of hu-BLT Mice Tissues

3.2. Increased Bone Formation Was Seen in Probiotic Bacteria-Fed hu-BLT Mice Compared to the Control Group

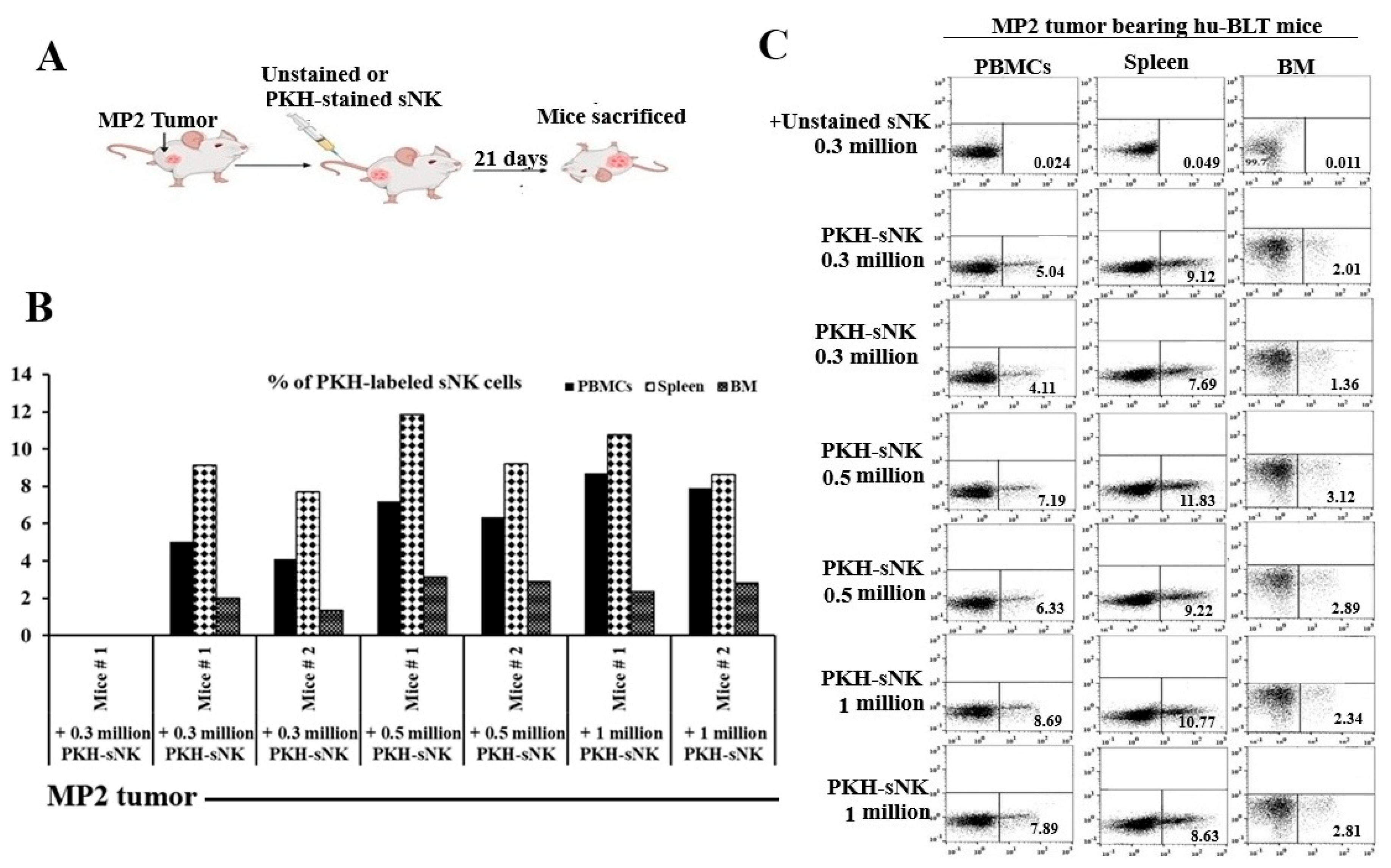

3.3. Adoptively Transferred sNK Cells Circulate to Tissue Compartments of Pancreatic Tumor-Bearing Hu-BLT Mice

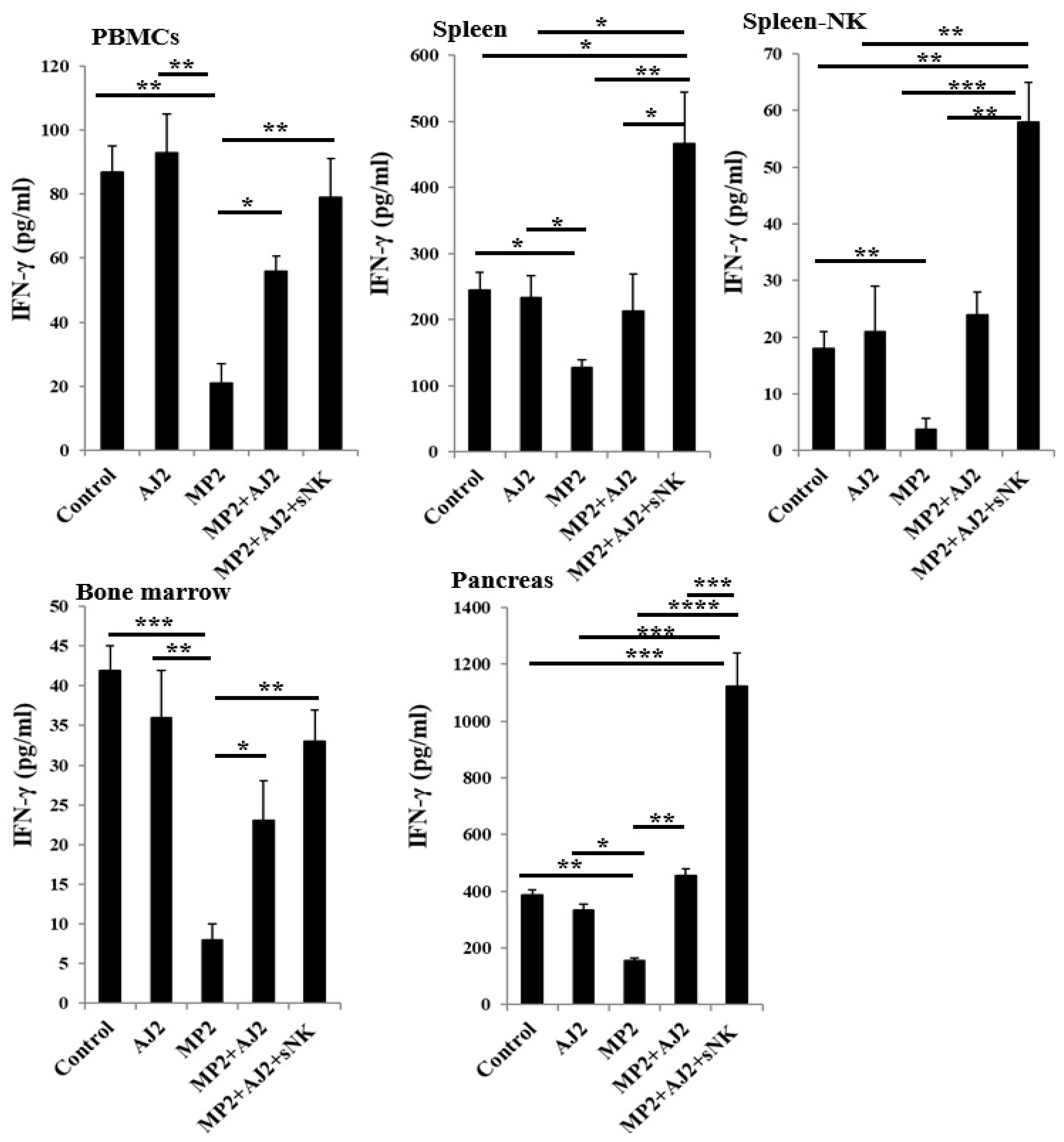

3.4. A Remarkable Increase in IFN-γ Secretion Was Seen in Mice Tissues When Mice Were Infused with sNK Cells and Fed with Probiotic Bacteria

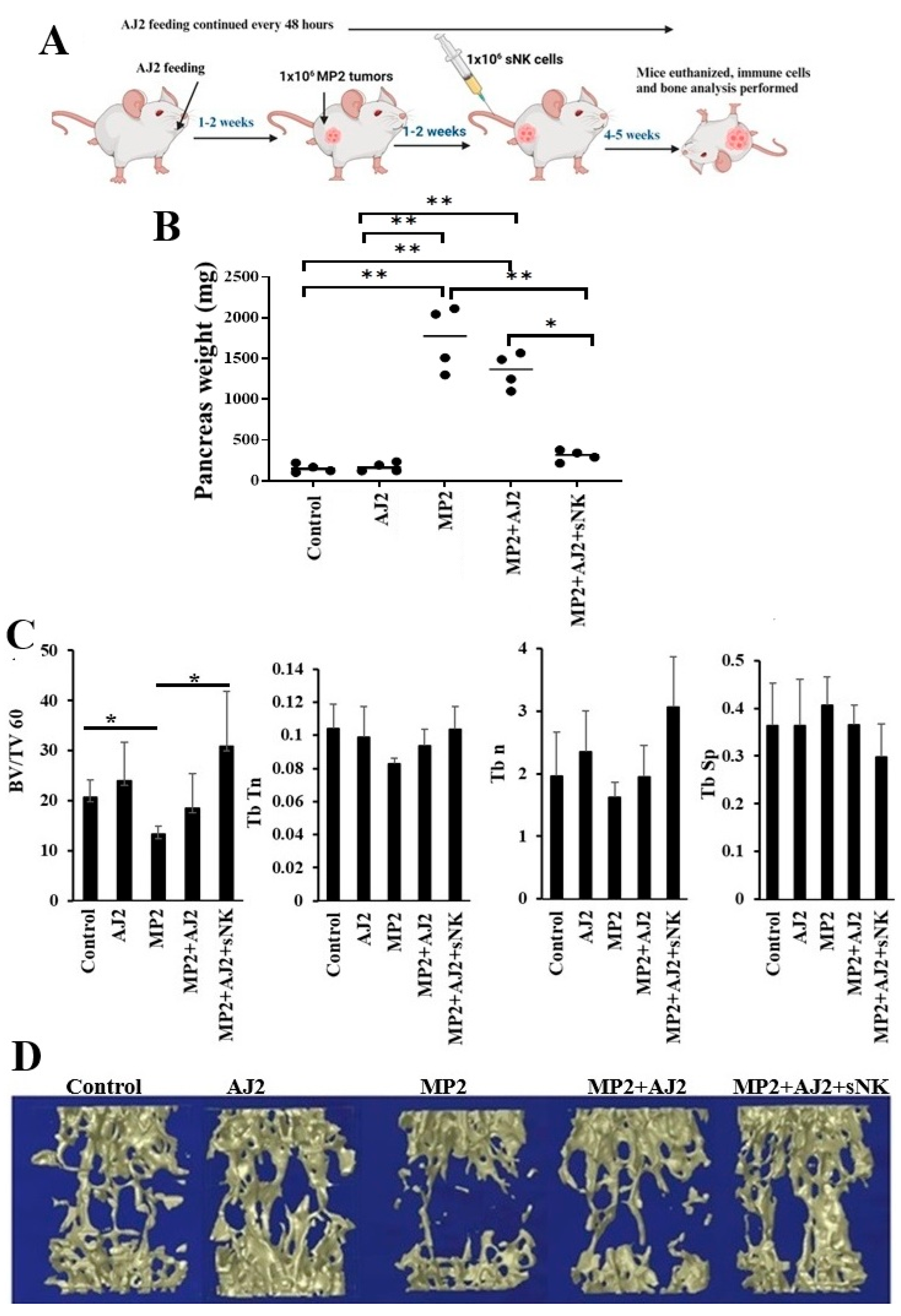

3.5. A Significant Reduction in Tumor Weight Was Seen When Pancreatic Tumor-Bearing hu-BLT Mice Were Infused with sNK Cells and Fed with Probiotic Bacteria

3.6. An Increase in Bone Formation Was Seen When Pancreatic Tumor-Bearing hu-BLT Mice Were Infused with sNK Cells and Fed with Probiotic Bacteria

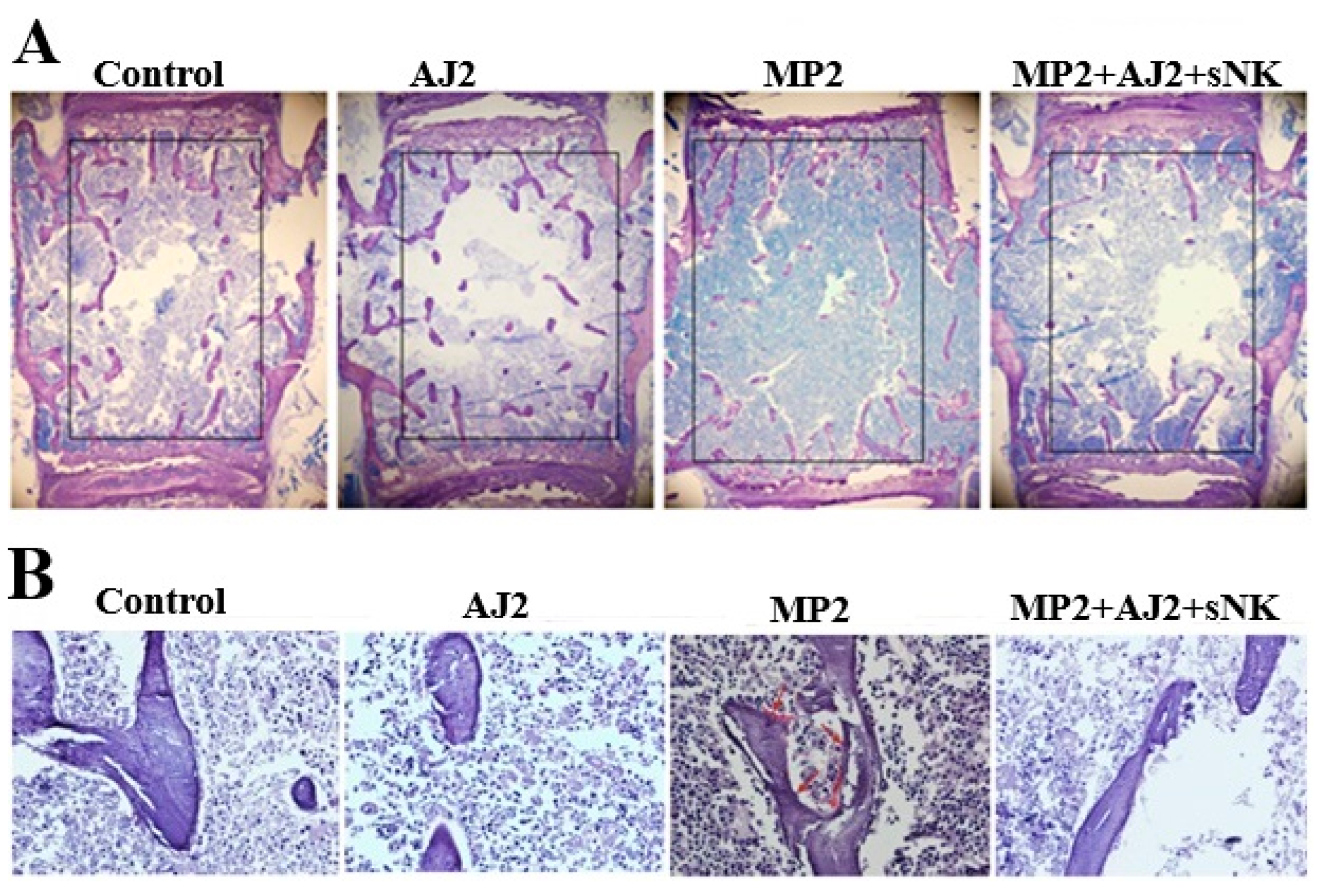

3.7. Increased Trabecular Bone Formation Was Observed When Pancreatic Tumor-Bearing Mice Were Fed Probiotic Bacteria Alone or Combined with sNK Cells Infusion

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest Statement

Abbreviations

| NK cells | Natural killer cells |

| sNK cells | Supercharged NK cells |

| CSCs | Cancer-stem-like-cells |

| Hu-BLT | Humanized-bone marrow/liver/thymus |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| IL-2 | Interleukin 2 |

| OCs | Osteoclasts |

| PBMCs | Peripheral blood-derived mononuclear cells |

| MP2 | MiaPaCa-2 |

| ELISAs | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays |

References

- Soderstrom K, et al. Natural killer cells trigger osteoclastogenesis and bone destruction in arthritis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America2010. p. 107(29): p. 13028-33.

- Tseng HC, Kanayama K, Kaur K, Park SH, Park S, Kozlowska A, et al. Bisphosphonate-induced differential modulation of immune cell function in gingiva and bone marrow in vivo: role in osteoclast-mediated NK cell activation. Oncotarget. 2015;6(24):20002-25.

- Ryschich EN, T.; Hinz, U.; Autschbach, F.; Ferguson, J.; Simon, I.; Weitz, J.; Fröhlich, B.; Klar, E.; Büchler, M.W.; et al. . Control of T-Cell-mediated immune response by HLA class I in human pancreatic carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 498–504.

- Pandha HR, A.; John, J.; Lemoine, N. . Loss of expression of antigen-presenting molecules in human pancreatic cancer and pancreatic cancer cell lines. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2007, 148, 127–135.

- Bui VTT, H.C.; Kozlowska, A.; Maung, P.O.; Kaur, K.; Topchyan, P.; Jewett, A. . Augmented IFNgamma and TNF-alpha Induced by Probiotic Bacteria in NK Cells Mediate Differentiation of Stem-Like Tumors Leading to Inhibition of Tumor Growth and Reduction in Inflammatory Cytokine Release; Regulation by IL-10. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 576.

- Kaur K, Cook J, Park SH, Topchyan P, Kozlowska A, Ohanian N, et al. Novel Strategy to Expand Super-Charged NK Cells with Significant Potential to Lyse and Differentiate Cancer Stem Cells: Differences in NK Expansion and Function between Healthy and Cancer Patients. Front Immunol. 2017;8:297. [CrossRef]

- Kaur K, Jewett A. Supercharged NK Cell-Based Immuotherapy in Humanized Bone Marrow Liver and Thymus (Hu-BLT) Mice Model of Oral, Pancreatic, Glioblastoma, Hepatic, Melanoma and Ovarian Cancers. Crit Rev Immunol. 2023;43(2):13-25. [CrossRef]

- Chiang J, Chen PC, Pham J, Nguyen CQ, Kaur K, Raman SS, et al. Characterizing hepatocellular carcinoma stem markers and their corresponding susceptibility to NK-cell based immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1284669. [CrossRef]

- Kaur K, Chen PC, Ko MW, Mei A, Senjor E, Malarkannan S, et al. Sequential therapy with supercharged NK cells with either chemotherapy drug cisplatin or anti-PD-1 antibody decreases the tumor size and significantly enhances the NK function in Hu-BLT mice. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1132807. [CrossRef]

- Kaur K, Kozlowska AK, Topchyan P, Ko MW, Ohanian N, Chiang J, et al. Probiotic-Treated Super-Charged NK Cells Efficiently Clear Poorly Differentiated Pancreatic Tumors in Hu-BLT Mice. Cancers (Basel). 2019;12(1). [CrossRef]

- Kaur K, Safaie T, Ko MW, Wang Y, Jewett A. ADCC against MICA/B Is Mediated against Differentiated Oral and Pancreatic and Not Stem-Like/Poorly Differentiated Tumors by the NK Cells; Loss in Cancer Patients due to Down-Modulation of CD16 Receptor. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(2). [CrossRef]

- Kaur KC, J.; Park, S.H.; Topchyan, P.; Kozlowska, A.; Ohanian, N.; Fang, C.; Nishimura, I.; Jewett, A. Novel Strategy to Expand Super-Charged NK Cells with Significant Potential to Lyse and Differentiate Cancer Stem Cells: Differences in NK Expansion and Function between Healthy and Cancer Patients. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 297.

- Li H, Hong S, Qian J, Zheng Y, Yang J, Yi Q. Cross talk between the bone and immune systems: osteoclasts function as antigen-presenting cells and activate CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2010;116(2):210-7. [CrossRef]

- Dong H, Rowland I, Yaqoob P. Comparative effects of six probiotic strains on immune function in vitro. Br J Nutr. 2012;108(3):459-70. [CrossRef]

- Ko MW, Mei A, Senjor E, Nanut MP, Gao LW, Wong P, et al. Osteoclast-expanded supercharged NK cells perform superior antitumour effector functions. BMJ Oncol. 2025;4(1):e000676. [CrossRef]

- Romee R, Rosario M, Berrien-Elliott MM, Wagner JA, Jewell BA, Schappe T, et al. Cytokine-induced memory-like natural killer cells exhibit enhanced responses against myeloid leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(357):357ra123. [CrossRef]

- Terrén I, Orrantia A, Astarloa-Pando G, Amarilla-Irusta A, Zenarruzabeitia O, Borrego F. Cytokine-Induced Memory-Like NK Cells: From the Basics to Clinical Applications. Front Immunol. 2022;13:884648. [CrossRef]

- Kaur K, Safaie T, Ko M-W, Wang Y, Jewett A. ADCC against MICA/B Is Mediated against Differentiated Oral and Pancreatic and Not Stem-Like/Poorly Differentiated Tumors by the NK Cells; Loss in Cancer Patients due to Down-Modulation of CD16 Receptor. Cancers. 2021;13(2):239. [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Yepez S, Chen PC, Kaur K, Jain Y, Singh T, Esedebe F, et al. Supercharged NK cells, unlike primary activated NK cells, effectively target ovarian cancer cells irrespective of MHC-class I expression. BMJ Oncol. 2025;4(1):e000618. [CrossRef]

- Ko M-W, Kaur K, Safaei T, Chen W, Sutanto C, Wong P, et al. Defective Patient NK Function Is Reversed by AJ2 Probiotic Bacteria or Addition of Allogeneic Healthy Monocytes. Cells. 2022;11(4):697. [CrossRef]

- Takayanagi H, et al. T-cell-mediated regulation of osteoclastogenesis by signalling cross-talk between RANKL and IFN-gamma. nature2000. p. 408(6812): p. 600-5. [CrossRef]

- Takayanagi H, J. Mechanistic insight into osteoclast differentiation in osteoimmunology. . Mol Med (Berl)2005. p. 83(3): p. 170-9. [CrossRef]

- Delves PJaIMR. The immune system. Second of two parts. . N Engl J Med; 2000. p. 343(2): p. 108-17.

- Gao Y, et al. IFN-gamma stimulates osteoclast formation and bone loss in vivo via antigen-driven T cell activation. The Journal of clinical investigation2007. p. 117(1): p. 22-32. [CrossRef]

- Cenci S, et al. Estrogen deficiency induces bone loss by increasing T cell proliferation and lifespan through IFN-gamma-induced class II transactivator. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America2003. p. 100(18): p. 10405-10. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu S, Hong P, Arumugam B, Pokomo L, Boyer J, Koizumi N, et al. A highly efficient short hairpin RNA potently down-regulates CCR5 expression in systemic lymphoid organs in the hu-BLT mouse model. Blood. 2010;115(8):1534-44. [CrossRef]

- Vatakis DN, Koya RC, Nixon CC, Wei L, Kim SG, Avancena P, et al. Antitumor activity from antigen-specific CD8 T cells generated in vivo from genetically engineered human hematopoietic stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(51):E1408-16. [CrossRef]

- Chennamadhavuni A, Iyengar V, Mukkamalla SKR, Shimanovsky A. Leukemia. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Varun Iyengar declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Shiva Kumar Mukkamalla declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Alex Shimanovsky declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.: StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2025.

- Kaur K, Chen P-C, Ko M-W, Mei A, Senjor E, Malarkannan S, et al. Sequential therapy with supercharged NK cells with either chemotherapy drug cisplatin or anti-PD-1 antibody decreases the tumor size and significantly enhances the NK function in Hu-BLT mice. Frontiers in Immunology. 2023;Volume 14 - 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kaur K, Jewett A. Supercharged NK Cell-Based Immuotherapy in Humanized Bone Marrow Liver and Thymus (Hu-BLT) Mice Model of Oral, Pancreatic, Glioblastoma, Hepatic, Melanoma and Ovarian Cancers. 2023;43(2):13-25. [CrossRef]

- Kaur K, Ko M-W, Ohanian N, Cook J, Jewett A. Osteoclast-expanded super-charged NK-cells preferentially select and expand CD8+ T cells. Scientific Reports. 2020;10(1):20363. [CrossRef]

- Kaur K, Paytsar T, Karolina KA, Nick O, Jessica C, Ou MP, et al. Super-charged NK cells inhibit growth and progression of stem-like/poorly differentiated oral tumors in vivo in humanized BLT mice; effect on tumor differentiation and response to chemotherapeutic drugs. OncoImmunology. 2018;7(5):e1426518.

- Kaur K, Kozlowska AK, Topchyan P, Ko M-W, Ohanian N, Chiang J, et al. Probiotic-Treated Super-Charged NK Cells Efficiently Clear Poorly Differentiated Pancreatic Tumors in Hu-BLT Mice. Cancers. 2020;12(1):63. [CrossRef]

- Bui VT, Tseng HC, Kozlowska A, Maung PO, Kaur K, Topchyan P, et al. Augmented IFN-γ and TNF-α Induced by Probiotic Bacteria in NK Cells Mediate Differentiation of Stem-Like Tumors Leading to Inhibition of Tumor Growth and Reduction in Inflammatory Cytokine Release; Regulation by IL-10. Front Immunol. 2015;6:576. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).