1. Introduction

Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) is a major microvascular complication of diabetes mellitus and a leading cause of preventable blindness among working-age adults worldwide. It results from chronic hyperglycemia, which impairs the function of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and damages the retinal vasculature. This dysfunction deprives the retina of oxygen and nutrients, promoting pathological angiogenesis—fragile new blood vessels that often leak or rupture, ultimately leading to retinal detachment and vision loss [

1,

2].

Panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) is a long-established and effective treatment for proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR). In PRP, a laser is used to destroy newly formed blood vessels and to create controlled thermal burns in the peripheral retina, thereby reducing the retina's metabolic demand and downregulating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production. This reduces neovascularization and halts disease progression [

3,

4].

The choice of laser wavelength is a critical factor in the efficacy and safety of PRP. Melanin, hemoglobin, and other ocular chromophores have distinct absorption characteristics that influence energy deposition. Traditionally, green lasers (532 nm) have been widely used due to their effective absorption by melanin and hemoglobin. However, green light exhibits significant intraocular scattering and is less selectively absorbed by hemoglobin compared to yellow (577nm) light [

5]. This reduces precision and increases the potential for collateral tissue damage.

Yellow lasers (577 nm), on the other hand, are emerging as a superior alternative for PRP. Yellow light is more selectively absorbed by oxyhemoglobin and melanin while exhibiting lower scatter, leading to more localized heating and less energy loss to surrounding tissues [

6,

7]. Moreover, the absorption peak of whole blood occurs closer to 577 nm, enabling more efficient targeting of neovascular tissue with potentially lower power requirements.

Despite these theoretical advantages, most prior studies comparing 532 nm and 577 nm lasers for PRP have been experimental or clinical in nature, with mixed results and often inconclusive outcomes [

8,

9]. Some studies found minimal differences in visual outcomes or lesion characteristics, while others suggested slightly improved coagulation thresholds and lesion control with yellow lasers [

10].

To address these uncertainties, we presented a comprehensive theoretical analysis using Monte Carlo Multi-Layer (MCML) simulations and finite element modelling (FEM) to evaluate the thermal and optical behaviour of green and yellow lasers during PRP [

11]. This research quantitatively demonstrated that yellow lasers provide more efficient energy deposition in the targeted blood vessels and RPE, achieving coagulation temperatures (60–80°C) with lower energy input compared to green lasers. The simulations showed that yellow lasers heat the blood layer to the optimal coagulation range with less risk of overheating the RPE and surrounding tissues. In contrast, green lasers require higher energy to achieve similar effects, increasing the likelihood of unintended tissue damage.

Additionally, the study confirmed that yellow lasers offer a more favourable balance between absorption and scattering coefficients in ocular tissues. For instance, yellow light showed higher absorption in hemoglobin (297.8 cm⁻¹ vs. 234.9 cm⁻¹ at 532 nm) and lower scatter coefficients, leading to better confinement of heat to the target zone. The temperature distribution analysis further supported the safety margin of yellow lasers, showing smaller temperature gradients and reduced collateral heating.

These findings align with earlier theoretical and clinical observations, suggesting that yellow lasers may enhance PRP precision, reduce required power, improve safety, and minimize patient discomfort. FEM simulations also demonstrated that yellow lasers reach coagulation thresholds faster than green lasers, which may shorten treatment times and improve patient experience [

12].

Although the use of yellow laser in PRP was compared experimentally in the past on animals and humans, it mainly compared the results for diabetic macular edema and not directly on blood vessels. This paper compares experimentally the use of yellow (577 nm) and green (525 nm) lasers for coagulating blood vessels and rich blood tissue in harvested porcine eyes.

2. Materials and Methods

To validate the theoretical findings and compare the tissue interaction characteristics of yellow and green lasers in a controlled environment, a series of laser irradiation experiments were performed on ex vivo porcine eyes. Porcine eyes are widely accepted as suitable models for human ocular studies due to their anatomical and histological similarity to human eyes, including similar retinal thickness, scleral rigidity, and overall ocular structure [

13,

14].

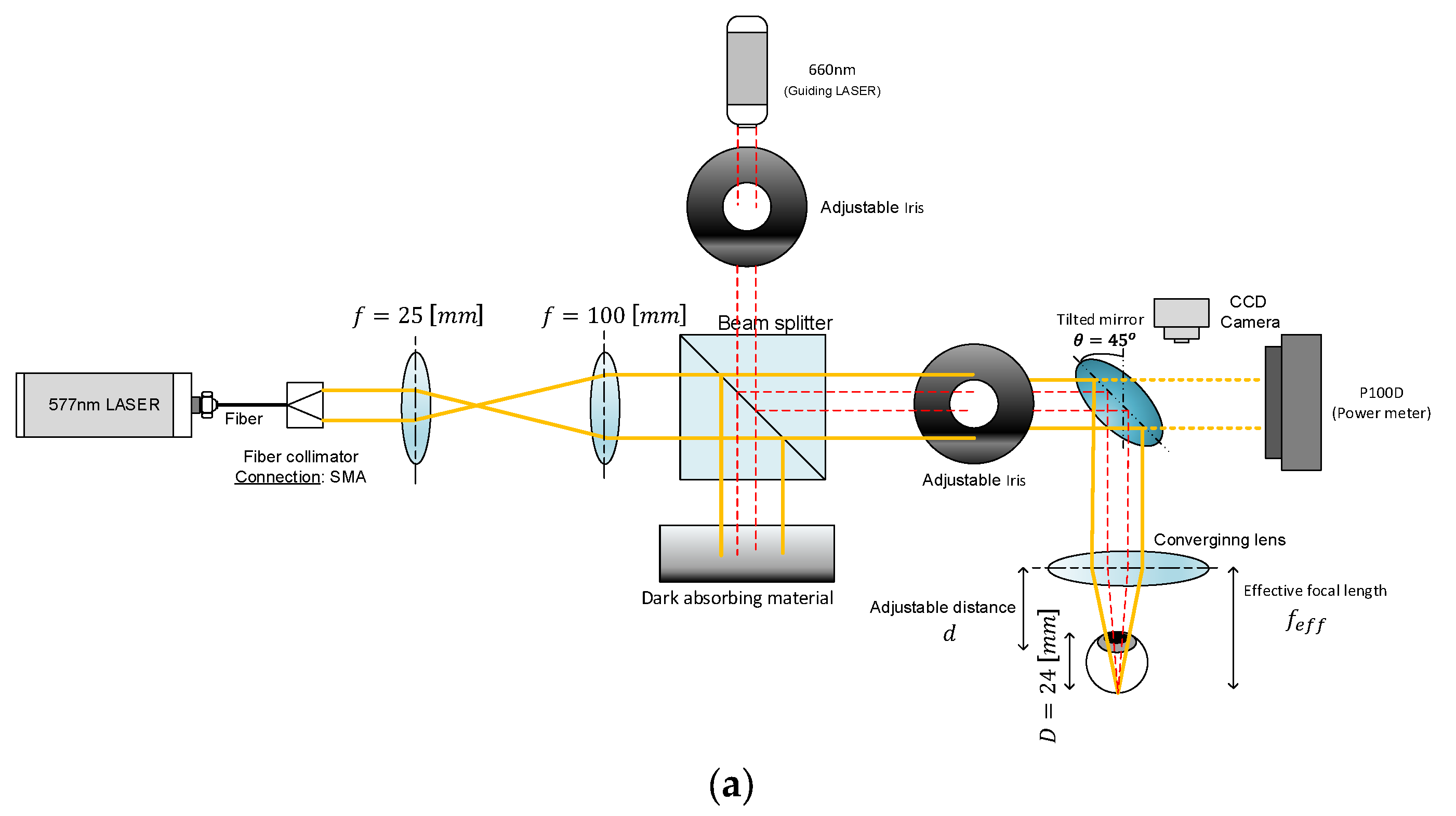

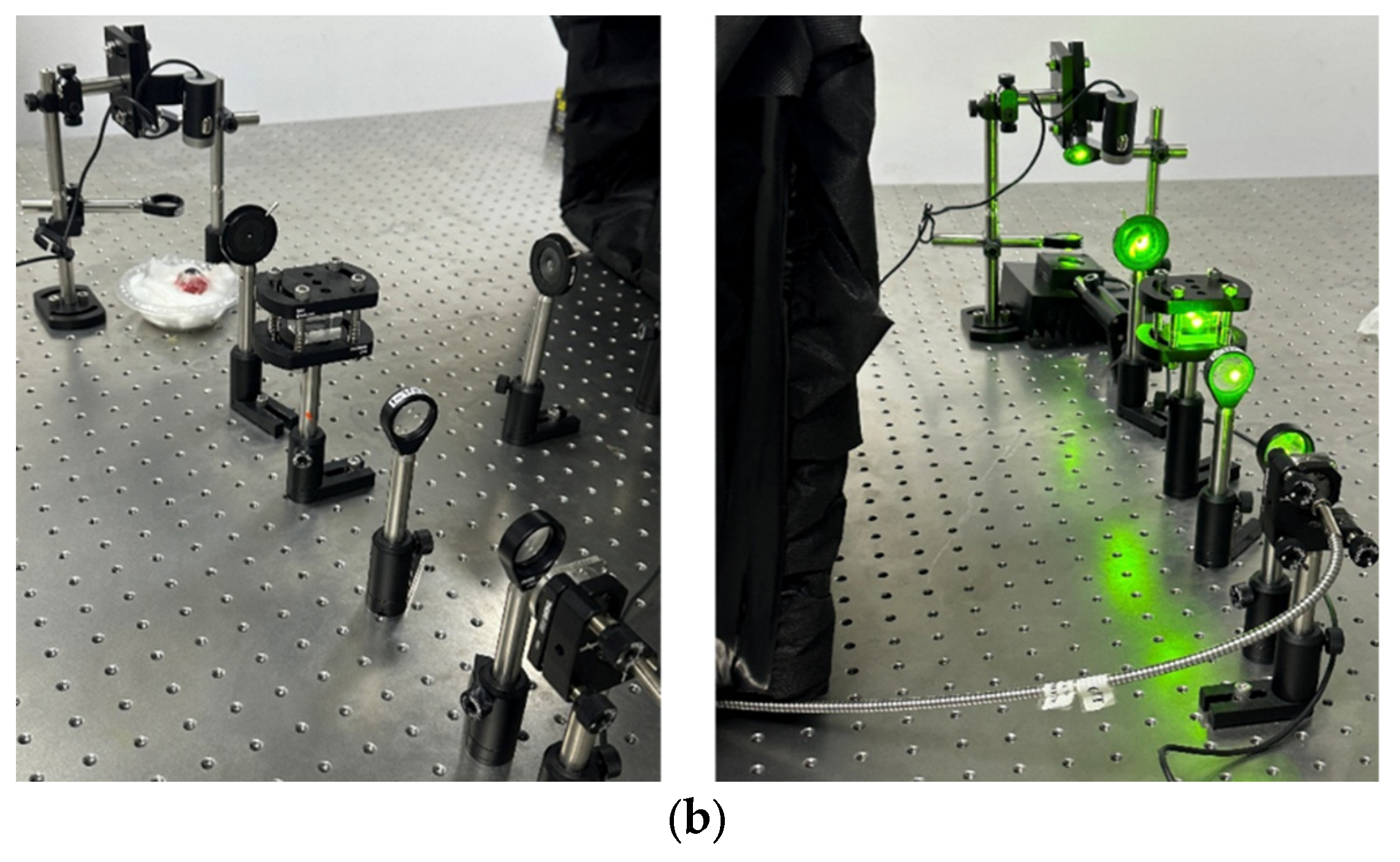

The laser systems used for the experiments were fiber-coupled diode lasers: a CNI 577 nm, 3 W yellow laser and a BWT 525 nm, 5 W green laser. The output from each laser was directed through a custom beam delivery system designed for optical expansion, collimation, and precise focusing on the retinal tissue, as shown in

Figure 1a,b.

First, the laser beams were collimated and expanded using a beam expander consisting of two biconvex lenses with focal lengths of 50 mm and 100 mm (Thorlabs). This configuration increased the beam diameter and ensured collimation of the output beam. Following the beam expander, the light was passed through a 50/50 beam splitter that enables monitoring of the laser power in real time. The transmitted beam passes through a variable iris diaphragm (Thorlabs) to control beam diameter and is then reflected downward using a metallic mirror (Thorlabs). Finally, the beam was focused onto the eye sample using a 50 mm focal length biconvex lens (Thorlabs), simulating the focusing action of a clinical PRP treatment system.

The iris diameter was set to 3.72mm for the yellow laser and 1.9mm and 2.5mm for the green one. The power of the laser at the surface of the retinal sample was measured and calibrated to approximately 90 mW for the 577 nm yellow laser and 100 mW (1.9mm iris) and 125 mW (2.5mm iris) for the 525 nm green laser. These values were selected to ensure consistent coagulation while minimizing tissue overexposure.

Freshly harvested porcine eyes were obtained and prepared for irradiation. A total of ten eyes were used in the study. Each eye was subjected to laser irradiation with both the green and yellow lasers, with each wavelength applied two to three times per eye, resulting in a total of 22 irradiation sites for each laser.

Following irradiation, the diameter of each coagulated lesion on the eye tissue was measured using a precision calliper to assess and compare the thermal impact of the two wavelengths. The measurement of lesion size served as a proxy for energy absorption efficiency and localization, allowing a direct comparison between the green and yellow laser effects on the tissue.

3. Results

The experimental evaluation compared the physical lesion diameters and calculated energy densities produced by the 577 nm yellow and 525 nm green lasers across 22 irradiation points each.

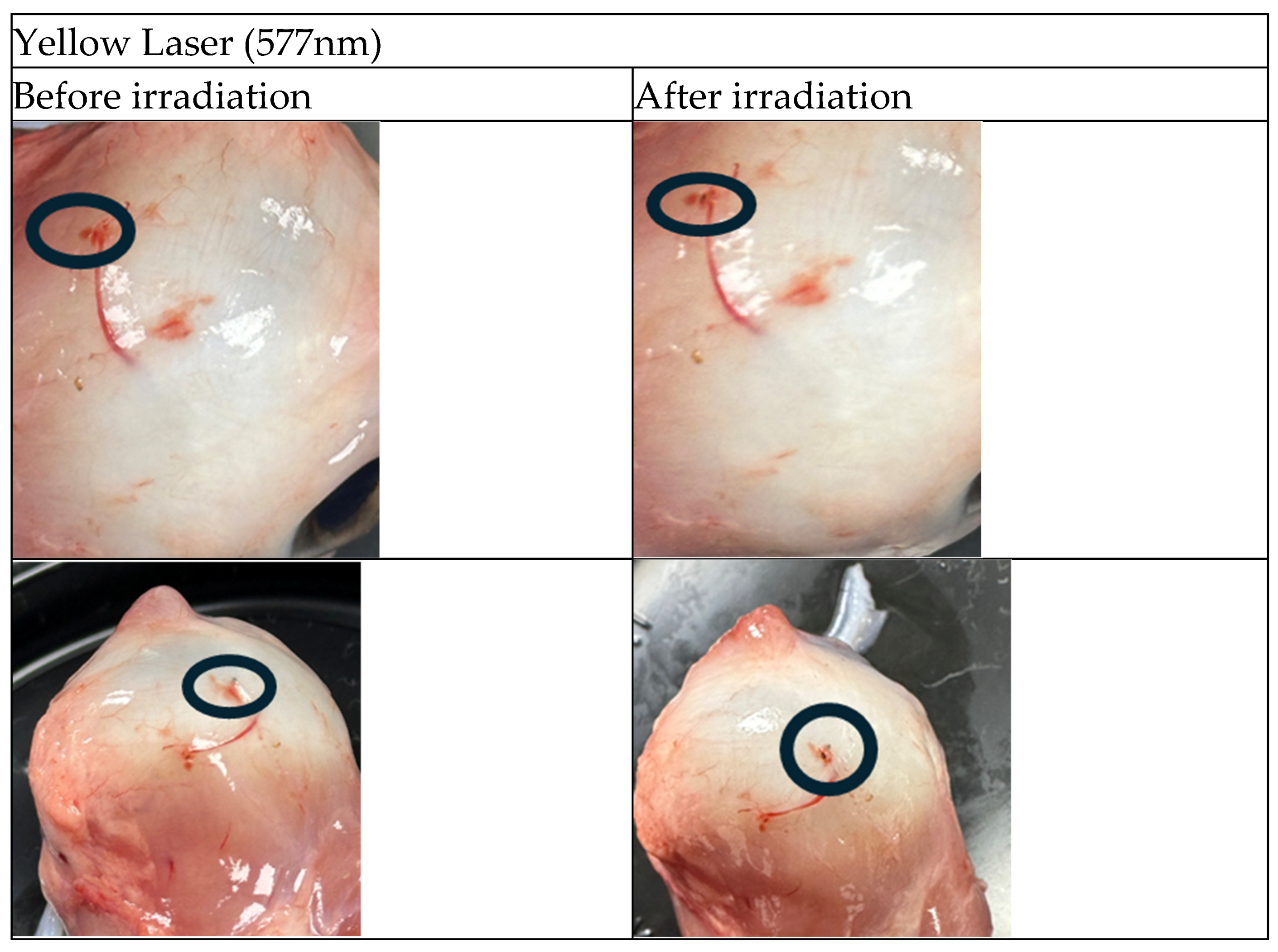

The following figures (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) present sample images of porcine eyes before and after laser irradiation with green and yellow lasers, respectively. The irradiated positions are circled in black.

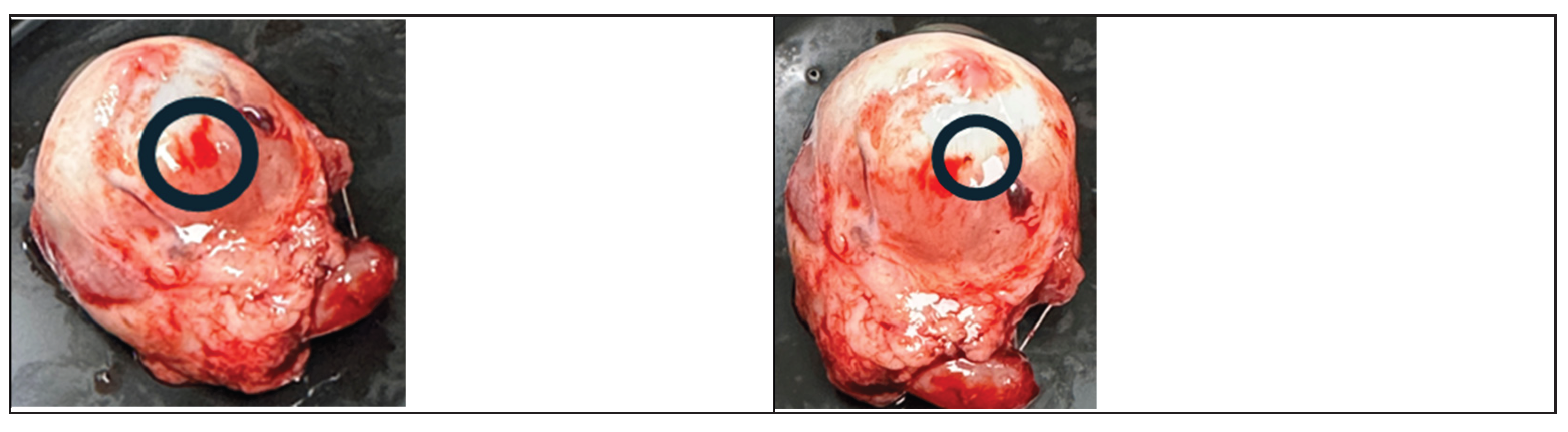

Figure 4 shows 2 irradiated spots, one with a yellow laser (

Figure 4a) and one with a green laser (

Figure 4b). It is clearly seen from the figures that the lesions created by the yellow laser are much smaller and with less residual thermal damage than the ones created by the green laser.

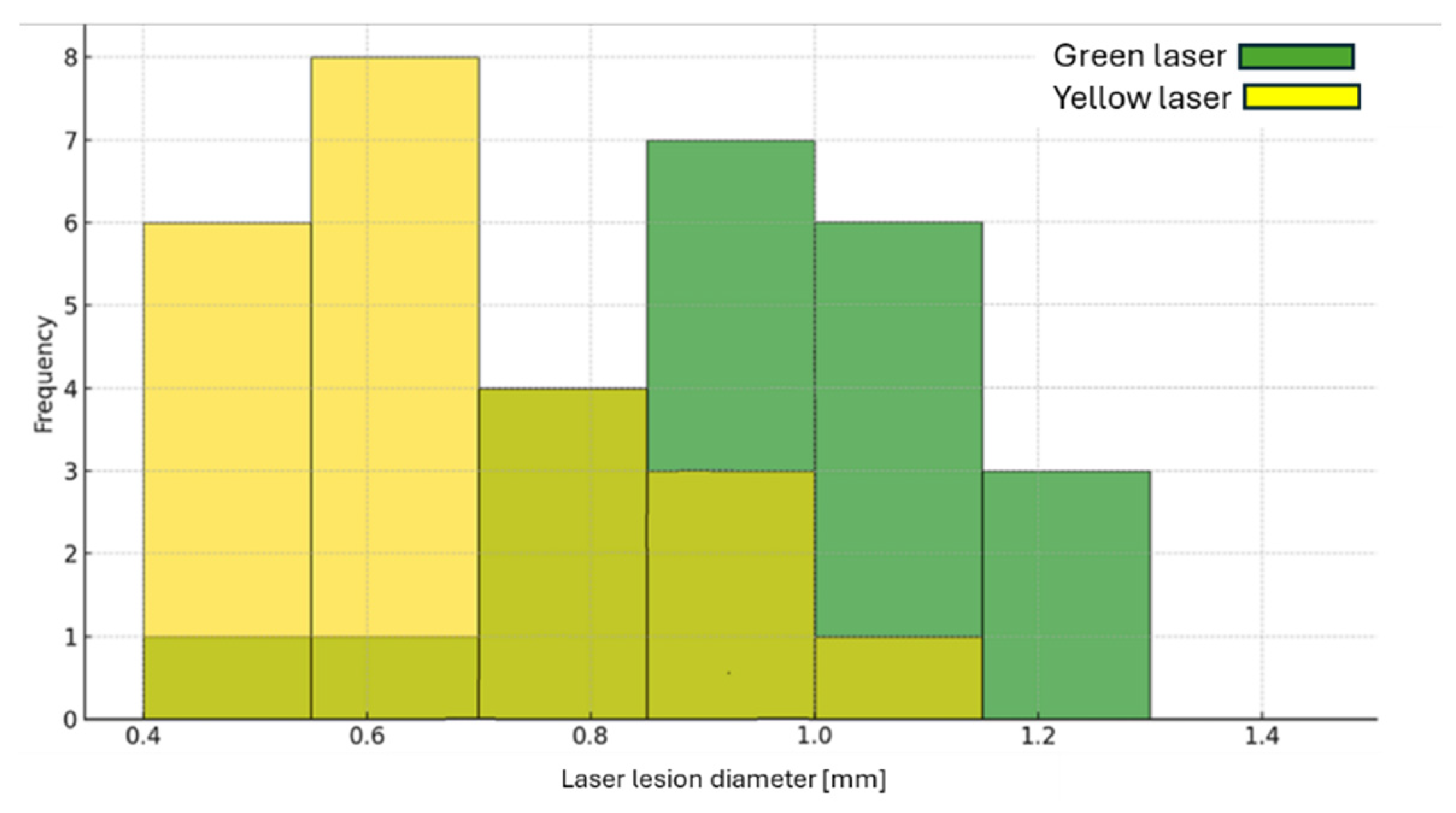

Figure 5 presents a histogram of the lesion diameter created by the yellow and green lasers' irradiation.

Table 1 lists the average, maximal and minimal lesion diameter as well as the values for the energy density for the yellow and green lasers. Although the power density of the yellow laser is higher than that of the green laser (a factor of 3.3), the resulting thermal lesion caused by the yellow laser is 50% smaller than the one caused by the green laser.

4. Discussion

The difference in the lesion size could be explained as follows. The energy density (I), on the tissue is determined by the laser energy (E), wavelength (λ), the focusing lens focal length (f), and the iris aperture diameter (D). Let us assume that the laser spot diameter on the tissue is d. The energy density is given by

where A is the laser spot cross-sectional area on the tissue, given by

Assuming a Gaussian laser beam

Now let us calculate the theoretical ratio of the energy density at two wavelengths (green [525nm] and yellow [577nm])

Table 2 lists the yellow and green lasers' experimental setup parameters.

Substituting the above value yields

The averaged measured energy density is 2969 mJ/mm

2 and 9776 mJ/mm

2 for the green and yellow lasers, respectively. The experimental ratio is 3.292. The ratio of the theoretical results to the experimental ones is 1.194 (3.933/3.292). The difference between the theoretical ratio and the experimental one is explained by the ratio of the total absorption coefficient at the two wavelengths, which is given by

where

is the absorption coefficient,

is the scattering coefficient, and g is the anisotropy of the tissue. Since the absorption occurs mostly in the blood, we will use the values of unsaturated whole blood. We use unsaturated blood and not saturated blood since the porcine eyes were harvested several hours prior to the experiment, and the Oxygen diffuses out of the blood and rich blood tissue at that time.

Table 3 shows the unsaturated whole blood optical parameters: absorption coefficient, scattering coefficient, and anisotropy [15] at two wavelengths. The ratio of the total attenuation coefficient at 577nm to 525nm is 1.2. Compensating the experimental energy density for the absorption coefficient, we get 3.9504 (1.2x3.292), which is 0.44% deviation from the theoretical value. As can be seen from the analysis, the experimental results are in agreement with the theoretical calculation.

5. Conclusions

This study explores the comparative effects of yellow (577 nm) and green (525 nm) lasers in treating diabetic retinopathy via panretinal photocoagulation. Through controlled experiments on ex vivo porcine eyes, we assessed lesion size and energy absorption characteristics for both wavelengths. The yellow laser demonstrated superior confinement of energy, producing smaller lesions despite higher energy density, in contrast to the green laser, which resulted in broader and more thermally damaging effects. The observed experimental data closely matched theoretical models accounting for the absorption and scattering coefficients of whole blood. These results reinforce the potential of yellow lasers for safer, more precise PRP treatment.

Author Contributions

Designing and building the experimental setup, S.B.-K. and E.M.; Analysing the experimental data, S.B.-K. and E.M.; Supervision and Theoretical Analysis, M.B.-D. and I.J.; Writing—original draft preparation, M.B.-D.; Writing—review and editing, I.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PRP |

PanRetinal Photocoagulation |

| DR |

Diabetic Retinopathy |

| RPE |

Retinal Pigment Epithelium |

| PDR |

Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy |

| VEGF |

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| MCML |

Monte Carlo Multi-Layer |

| FEM |

Finite Element Modelling |

References

- Antonetti, D.A.; Klein, R.; Gardner, T.W. Diabetic retinopathy. New England Journal of Medicine 2012, 366, 1227–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.-Z.; Song, Z.; Fu, S.; Zhu, M.; Le, Y.-Z. RPE barrier breakdown in diabetic retinopathy: seeing is believing. Journal of Ocular Biology, Diseases, and Informatics 2011, 4, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ETDRS Research Group. Photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema. Archives of Ophthalmology 1985, 103, 1796–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.; Husain, D. Panretinal Photocoagulation: A Review of Complications. Seminars in Ophthalmology 2018, 33, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosschaart, N.; Edelman, G.J.; Aalders, M.C.G.; Van Leeuwen, T.G.; Faber, D.J. A literature review and novel theoretical approach on the optical properties of whole blood. Lasers in Medical Science 2014, 29, 453–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainster, M.A. Decreasing retinal photocoagulation damage: principles and techniques. Seminars in Ophthalmology 1999, 14, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, M.K.; Weinstock, B.M.; Kasi, S.K.; Ehmann, D.S.; Hsu, J.; Garg, S.J.; Ho, A.C.; Chiang, A. Patient comfort with yellow (577nm) vs. green (532nm) laser panretinal photocoagulation for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology Retina 2018, 2, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bressler, S.B.; Almukhtar, T.; Aiello, L.P.; Bressler, N.M.; Ferris 3rd, F.L.; Glassman, A.R.; Greven, C.M. Green or yellow laser treatment for diabetic macular edema: exploratory assessment within diabetic retinopathy clinical research network. Retina 2013, 33, 2080–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, D.J.; Antoszyk, A.N. The effect of the surgeon and the laser wavelength on the response to focal photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 1999, 106, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sramek, C.K.; Leung, L.-S.B.; Paulus, Y.M.; Palanker, D.V. Therapeutic window of retinal photocoagulation with green (532-nm) and yellow (577-nm) lasers. Ophthalmic Surgery Lasers Imaging 2012, 43, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aflalo, K.; Ben-David, M.; Stern, A.; Juwiler, I. Theoretical Investigation of Using a Yellow (577nm) Laser for Diabetic Retinopathy. OSA Continuum 2020, 3, 3253–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hussainy, S.; Dodson, P.M.; Gibson, J.M. Pain response and follow-up of patients undergoing panretinal laser photocoagulation with reduced exposure times. Eye 2008, 22, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duma, S.M.; Power, E.D.; Stitzel, J.D.; Jernigan, M.V.; Herring, I.P.; Duncan, R.B.; Pickett, J.P.; Bass, C.R. The porcine eye as a surrogate model for the human eye: anatomical and mechanical relationships. In Twenty-Eighth International Workshop; Bandak, F. A., Ed.; National Transportation Biomechanics Research Center: Atlanta, Georgia, 2000; pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, I.; Martin, R.; Ussa, F.; Fernandez-Bueno, I. The parameters of the porcine eyeball. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 2011, 249, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).