Introduction

Anti-Müllerian hormone is a member of the TGF-β superfamily acting on tissue growth and differentiation. It is synthesized as a glycosylated pre-pro-protein of 560 amino acids that undergoes the removal of the first 24 amino acids forming the pro-peptide (pro-AMH) not able to activate AMH receptors. After an enzymatic cleavage of pro-AMH, a C-terminal portion of 25kDa (AMH

C) and a N-terminal portion of 120kDa (AMH

N) are obtained and remain associated to generate the bioactive complex AMH

N,C [

1,

2]. Recently, has been demonstrated that both pro-AMH and AMH

N,C circulate in the blood in approximately equal amounts, while there is no evidence of the two separate entities in the circulation [

1]

AMH was originally identified for its basilar role in male sex differentiation. In fact, the hormone produced by Sertoli cells of foetal testis induces the regression of Mullerian ducts and prevent their evolution in typical female sexual organs by acting in a paracrine/autocrine way [

3]. In male, AMH remains secreted at high level until puberty while in adults its level decreased dramatically but it continues to exert paracrine control of testicular function. In women, AMH is produced by ovary granulosa cells of growing pre-antral and antral follicles, but not from the primordial follicles, and the main physiological role seems to be limited to the inhibition of the early stages of follicular development [

4]. In both sexes AMH is secreted in serum and represents a specific marker of Sertoli cell function and spermatogenesis in men, and a clinical marker of ovarian reserve and response to gonadotrophins especially in women who undergo IVF treatments [

4,

5]. The levels of AMH diminish markedly in boys as they approach puberty, while ovarian production being initiated in young girls, after which it slowly rises as they mature, so young men and women have similar levels of AMH. In women, the levels of AMH decline as ovarian reserve diminishes reaching values close to zero at the time of menopause [

6]. Physiological variations in AMH levels are a function of both sex and age, do not exhibit circadian fluctuation and remain stable throughout the menstrual cycle [

7]. However, the measurement of AMH represents not only a marker of reproductive status in male and female, but abnormal levels can be found in a wide spectrum of diseases in both sexes [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Acknowledged the clinical importance of AMH evaluation in serum, in recent years a rapid development of AMH assays has occurred. The most commonly used methodology for AMH measurement in clinical laboratory is the Beckman Coulter AMH Gen II ELISA assay, an enzymatically amplified two-site manual microplate immunoassay using two antibodies directed against epitopes in mature AMH

N,C and in proAMH molecules [

15]; the latter two entities are measured in a similar but not identical manner, while the two separate entities AMH

C and AMH

N are not measured [

16]. The protocol was revised in 2013 due to falsely low readings [

15]. This immunoassay was widely used in clinical laboratories all over the world not only for diagnostic purposes but also for producing numerous publications in prestigious scientific reviews and made AMH one of the most significant new marker in reproductive endocrinology. Despite this, manual ELISA techniques are laborious and time consuming and results may be influenced by handling practices. For this reason, many efforts have been made to develop a fully automated assay supplying more reproducible and accurate results [

17]. In 2014 Beckman Coulter announced the release of a new automated assay for AMH measurement to be used on Access Immunoassay System (Access AMH assay) employing identical antibodies and calibrators to those of AMH Gen II ELISA assay. Analytical and technical performances of Access AMH assay were the subject of some recent scientific publications [

17,

18,

19,

20] in which intra- and inter-assay precision, sensitivity, linearity, repeatability and imprecision were evaluated.

In order to substitute our current assay to measure serum AMH with the new assay to make easier laboratory routine and providing more reproducible and accurate results, the evaluation of the fully automated CLIA assay was performed by using 154 serum samples covering the whole measurable interval and the range of clinically observable values. In the present study we reported our experience in the comparison of results obtained with AMH Gen II ELISA assay and Access AMH assay. Moreover, we checked LoQ manufacturer claim.

Materials and Methods

Serum Samples Collection

A total of 154 serum samples from randomized females to whom AMH test was prescribed and who referred to the hospital laboratory of endocrinology, were selected and AMH was routinely determined by AMH Gen II ELISA assay. Samples were preserved at -20°C until AMH evaluation was also performed by using Access AMH assay.

AMH Measurement by AMH Gen II ELISA Assay

AMH measurements in our lab are routinely performed by using AMH Gen II ELISA assay (Beckman Coulter Diagnostics, Brea, CA, USA) on Grifols Triturus ELISA instrument, according to the manufacturer’s instructions which also reported performances of the assay.

AMH Measurement by Access AMH Assay

AMH measurements were also performed by using Access AMH assay on Beckman Coulter UniCel DxI 600 automated platform (Beckman Coulter Diagnostics, Brea, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions which also reported performances of the assay.

Statistical Analysis and Method Comparison

Statistical analysis of results was carried out using the MedCalc statistical software for biomedical research version 13.3.0.0 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium,

https://www.medcalc.org) as previously described [

21].

Method comparison was performed by using Passing-Bablok regression non-parametric analysis with a Confidence Interval (CI) of 95% [

22,

23] and Bland-Altman analysis with a CI of 95% [

24].

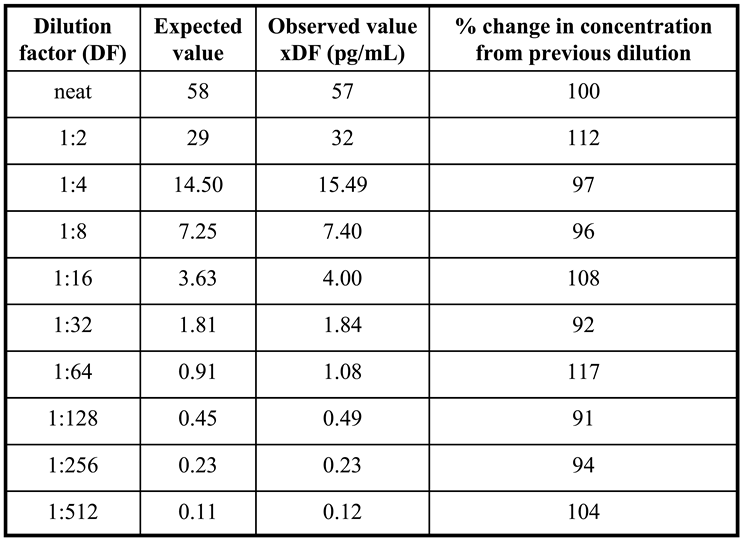

Scalar Dilution of Access AMH Assay

To validate Access AMH specificity and accuracy a serum sample with an AMH concentration of 58 ng/mL was selected to perform the scalar dilution test. The sample was analyzed neat and diluted 1:2, 1:4, 1:8, 1:16, 1:32, 1:64, 1:128, 1:256, 1:512 and the dilution curve was constructed. For each sample, the % change in concentration from the previous dilution was determined. Dilutional linearity was considered acceptable if the analyte concentration corrected for the dilution factor varied no more than 80-120% between doubling dilutions [

25]. Verification of calibrator dilution was also performed by diluting the highest calibrator in sample diluent provided by manufacturer.

Matrix and Calibration Comparison

Serum and lithium heparin plasma are the recommended samples in both Access AMH and AMH Gen II assays, and both assays use the same antibodies and calibrators. However, to asses a possible matrix effect, calibrators were assayed mutually as samples in both analytical systems and the recovery was evaluated. Based on intended use of the assay, a recovery set to ± 20% with respect to the nominal concentration is considered acceptable.

Limit of Quantitation (LoQ) of Access AMH Assay

The limit of quantification was determined according to the EP 17-A2 guidelines, using five serum samples with very low AMH concentration (0.01, 0.02, 0.03, 0.05, 0.07 ng/mL), 2 reagent lots with 10 replicates per sample [

26]. Considering pre-defined goals for bias and imprecision, the LoQ was defined as the concentration that results in a CV ≤20%.

Ethical Approval

Having performed the research on pre-existing serum samples referred for routine AMH determination, no institutional review board approval was necessary. However, the laboratory is in possession of a certificate of approval by the ethics committee for the use for scientific purposes of serum samples destined for disposal (CEAVNO, protocol n. 16726, 27/03/2018). Informed consent was obtained by all subjects enrolled in the study. The research has been carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans.

Results

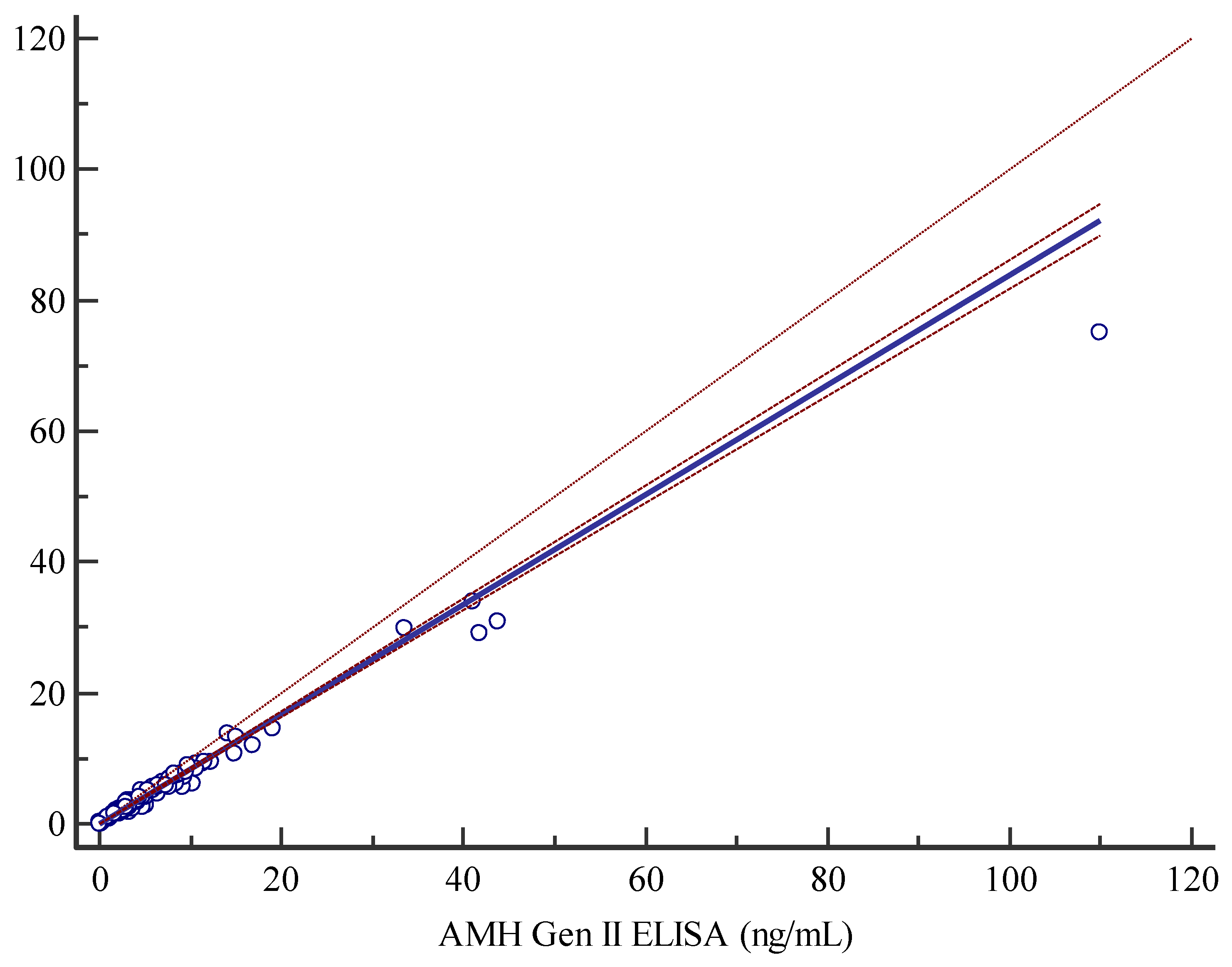

The Access AMH assay and the manual AMH Gen II assay displayed a good/strong correlation as shown by Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.988. The non-parametric Passing-Bablok regression analysis, y=0.0377619+0.838096x, highlighted a slight constant and proportional systematic error as documented by 95% CI for intercept and slope of 0.01838-0.05954 and 0.8165-0.8599 respectively (

Figure 1). The applicability of Passing-Bablok analysis was tested with Cusum testing, indicating no significant deviation from linearity (P=0.30), furthermore residual plots (graphs not shown) representing the distribution of differences around fitted regression line, showed that residuals are randomly distributed above and below regression line, with a dispersion that slightly increases with analyte rising concentrations measured with the AMH Gen II ELISA assay (data not shown).

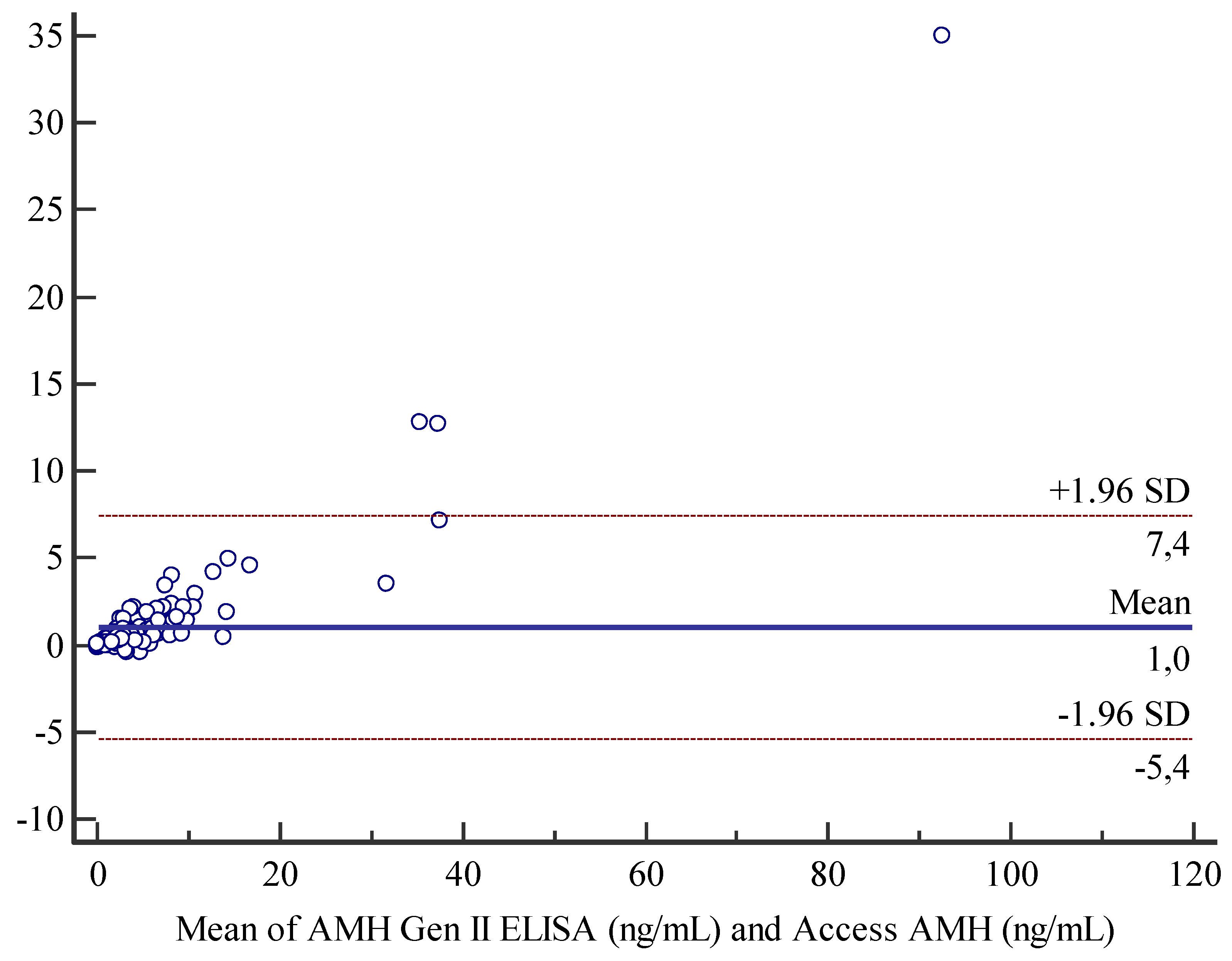

Bland-Altman analysis for comparison between Access AMH assay and AMH Gen II assay displayed a mean bias of 1 unit and an agreement range from -5.4 and 7.4 units (

Figure 2). Moreover, we also observed for the current method a general tendency to slightly overestimate results with respect to the new method, that is more evident at the higher concentrations of analyte (

Figure 3).

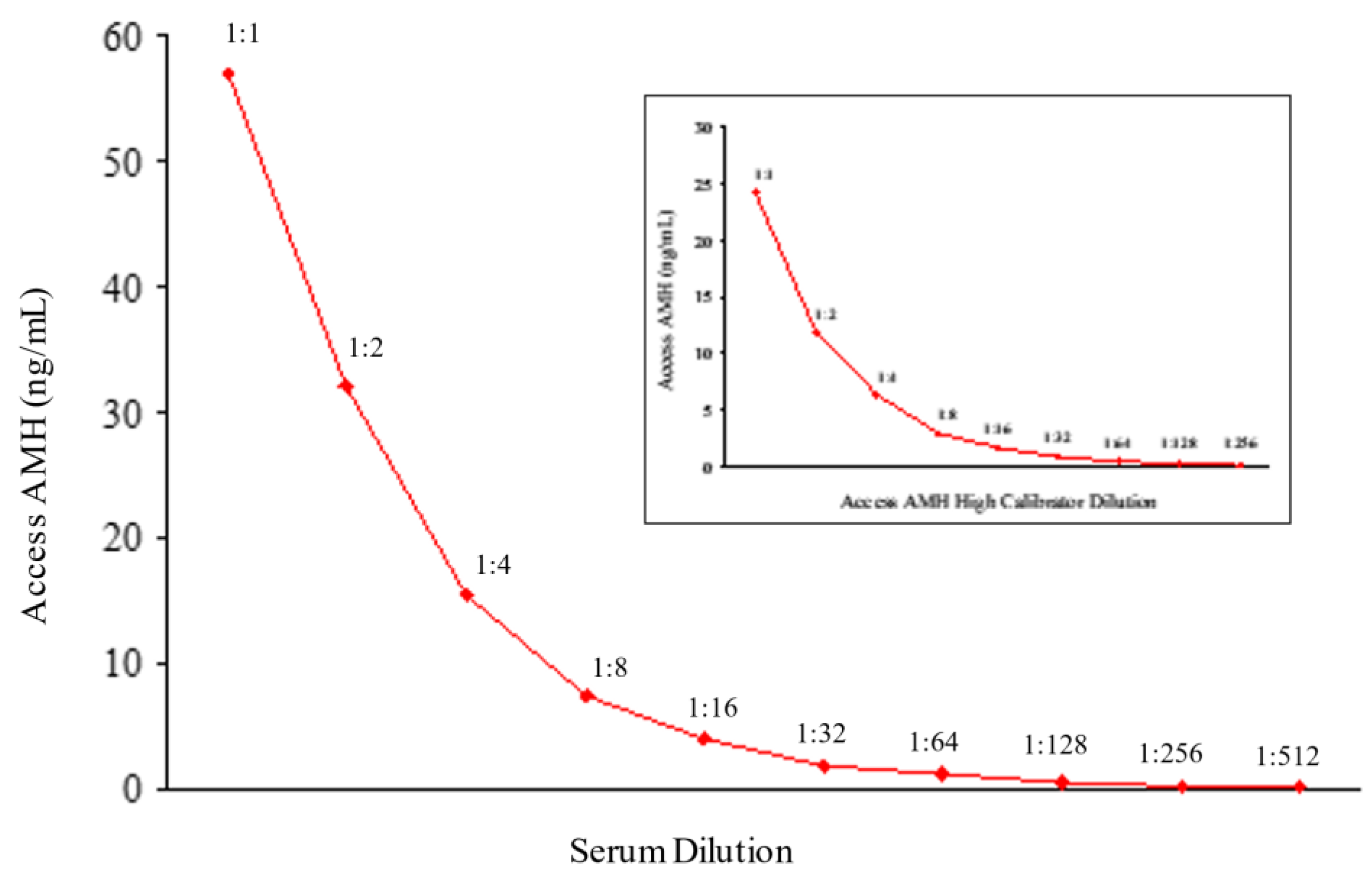

In

Figure 3 results of dilution linearity test are shown. Up to 1:512 dilution of a sample with starting concentration of 58 ng/mL AMH, the obtained values corrected for dilution factor were within 120% of the whole sample (

Table 1), and similar linearity characteristics after dilution were obtained for the highest calibrator (24 ng/mL) of Access AMH assay (

Figure 3). A good linearity over a wide range of dilutions was showed from the new method that resulted reliable to measure samples with very different concentrations of AMH. In other words, a strong dilution of samples with high levels of analyte can be made having the certainty that values obtained fall within the range of the standard curve, maintaining the accuracy and precision of the method.

A recovery of ±20% was observed for each calibrator mutually assayed as a sample in both analytical systems (data not shown) excluding a relevant matrix effect.

Access AMH assay’s manufacturer declared, on the basis of EP17-A2 guidelines [

26], a LoB value of 0.0024 ng/mL, a LoD value corresponding to analytical sensitivity of 0.0049 ng/mL and a LoQ value representing the functional sensitivity of 0.01 ng/mL. For all five samples with low AMH concentration CV% values were well below 20%, ranging from 3.0 to 4.2%. The LoQ value was set to 0.01 ng/mL in line with what stated by manufacturer.

Discussion

AMH is a dimeric glycoprotein hormone belonging to TGF-β family which owes the name to its function to determine the regression of Müllerian ducts during early male intrauterine life. On the contrary, in female the absence of AMH allows the Müllerian ducts to evolve in the typical sexual organs. Serum AMH concentrations in males are high until puberty and then decrease slowly to residual adult levels, while in females AMH levels increase gradually until puberty and remains relatively stable during the reproductive period becoming not determinable in menopause [

3,

4,

5,

6].

The primary utility of AMH serum evaluation was to diagnose pediatric disorders such as male testicular function, ambiguous genitalia and precocious or delayed puberty. Only over the last decade, AMH measurements were acknowledged essential to evaluate ovarian reserve to predict response to controlled ovarian stimulation in women with infertility problems. In fact, serum concentrations of AMH in adults represent a clinical marker of ovarian reserve and reproductive capacity in women and a specific marker of Sertoli cell function and spermatogenesis in men. In particular in women, AMH levels correlate very well with the number of ovarian follicles potentially capable of maturation, resulting very useful in assisted reproductive medicine practice. Moreover, AMH represents a marker in some pathological conditions such as PCOS in which its elevated levels are due to accumulation of small antral follicles, and an estimate of time of menopause onset [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Given the clinical importance of measuring AMH levels in serum, a large number of immunometric assays were developed in recent years. As mentioned above, AMH Gen II ELISA assay is one of the first manual and probably the most used assay in endocrinology laboratories. Despite critical issues of this dosage due mainly to specific storage and assay conditions [

27,

28,

29], it is recognized as the current clinical standard assay having made possible the large-scale AMH measurement, thus making it a reliable and easily measurable marker of ovarian function [

17]. No international standard recognized in agreement with the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry is currently available, and calibrators prepared with human recombinant total AMH supplied with this assay make patient results particularly accurate and reliable. However, the use of manual assays is restricted by low throughput and variability due to technician handling, so the use of an alternative fully automated system could be desirable.

Recently, Beckman Coulter released Access AMH assay, a new automated assay for AMH measurement to be used on Access Immunoassay System employing identical antibodies and calibrators to those of AMH Gen II ELISA assay. For Access AMH assay a LoB of 0.0024 ng/mL, a LoD of 0.0049 ng/mL and a LoQ of 0.010 ng/mL are reported. Total imprecision ranges from 2.4 and 5.2 % with an excellent linearity in the measuring range. Finally, Access AMH assay supplies consistent and standardized results with AMH Gen II assay with which strongly correlates as demonstrated by the Spearman’s correlation coefficient of 0.988 [

17]. The new method demonstrated excellent analytical performance and represents a robust, fast and precise alternative to manual assay.

In order to adopt the Access AMH assay for the routine purposes of our lab, results obtained with this assay were compared with those obtained with the current manual AMH Gen II assay. The two methods showed a strong relationship with Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.99 and Passing-Bablock regression and Bland-Altman analysis showed a nearly negligible systematic error.

Results from literature clearly demonstrate that Access AMH assay is superior to manual AMH assay and is suitable for implementation routine practices [

17,

18,

19,

20]. This fully automated assay showed, in method comparison studies, a high correlation with the manual assay in the presence of an excellent analytical sensitivity documented by a LoQ of 0.01 ng/mL [

17]. Despite some recent studies suggested that AMH may be prone to preanalytical instability [

29], highly stable AMH values were obtained under room temperature, refrigerated and frozen conditions by using Access AMH assay [

17]. For automated Access AMH assay an assay-specific reference interval was reported taking also into account male Tanner stages describing the onset and progression of pubertal changes [

17] This reference range was adopted by our lab after switching to the automated assay.

In conclusion, our data obtained in method comparison studies are in good agreement with what reported in the literature, making us to conclude that the automatic assay represents a robust, fast and precise alternative to manual AMH assay with improvement in evaluation of serum AMH levels in terms of analytical performances.

Author Contributions

M.R.S., P.A. and D.T. planned the experiments. L.B., C.N. and A.D.G. conducted all experiments. P.A. wrote the main manuscript test and prepared figures. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pankhurst, M.W.; McLennan, I.S. Human blood contains both the uncleaved precursor of anti-Müllerian hormone and a complex of the NH2- and COOH-terminal peptides. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2013, 305, E1241–E1247. [CrossRef]

- McLennan, I.S.; Pankhurst, M.W. Anti-Müllerian hormone is a gonadal cytokine with two circulating forms and cryptic actions. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 226, R45–R57. [CrossRef]

- Münsterberg, A.; Lovell-Badge, R. Expression of the mouse anti-Müllerian hormone gene suggests a role in both male and female sexual differentiation. Development 1991, 113, 613–624. [CrossRef]

- Hiedar, Z.; Bakhtiyari, M.; Foroozanfard, F.; Mirzamoradi, M. Age-specific reference values and cut-off points for anti-müllerian hormone in infertile women following a long agonist treatment protocol for IVF. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2017, 41, 773–780. [CrossRef]

- La Marca, A.; Sighinolfi, G.; Radi, D.; Argento, C.; Baraldi, E.; Artenisio, A.C.; Stabile, G.; Volpe, A. Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) as a predictive marker in assisted reproductive technology (ART). Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2009, 16, 113–130. [CrossRef]

- Aksglaede, L.; Sørensen, K.; Boas, M.; Mouritsen, A.; Hagen, C.P.; Jensen, R.B.; Petersen, J.H.; Linneberg, A.; Andersson, A.-M.; Main, K.M.; et al. Changes in Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH) throughout the Life Span: A Population-Based Study of 1027 Healthy Males from Birth (Cord Blood) to the Age of 69 Years. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 5357–5364. [CrossRef]

- La Marca, A.; Stabile, G.; Artenisio, A.; Volpe, A. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone throughout the human menstrual cycle. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 21, 3103–3107. [CrossRef]

- Depmann, M.; Eijkemans, M.J.C.; Broer, S.L.; Tehrani, F.R.; Solaymani-Dodaran, M.; Azizi, F.; Lambalk, C.B.; Randolph, J.F.; Harlow, S.D.; Freeman, E.W.; et al. Does AMH Relate to Timing of Menopause? Results of an Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 3593–3600. [CrossRef]

- Rey, R.A.; Belville, C.; Nihoul-Fékété, C.; Michel-Calemard, L.; Forest, M.G.; Lahlou, N.; Jaubert, F.; Mowszowicz, I.; David, M.; Saka, N.; et al. Evaluation of Gonadal Function in 107 Intersex Patients by Means of Serum Antimüllerian Hormone Measurement1. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999, 84, 627–631. [CrossRef]

- Grinspon, R.P.; Gottlieb, S.; Bedecarrás, P.; Rey, R.A. Anti-Müllerian Hormone and Testicular Function in Prepubertal Boys With Cryptorchidism. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 182. [CrossRef]

- Edelsztein, N.Y.; Grinspon, R.P.; Schteingart, H.F.; Rey, R.A. Anti-Müllerian hormone as a marker of steroid and gonadotropin action in the testis of children and adolescents with disorders of the gonadal axis. Int. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2016, 2016, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Bhide, P.; Homburg, R. Anti-Müllerian hormone and polycystic ovary syndrome. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 37, 38–45. [CrossRef]

- Karakas, S.E. New biomarkers for diagnosis and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin. Chim. Acta 2017, 471, 248–253. [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, A.; Eldar-Geva, T. Anti-Mullerian Hormone (AMH) Determinations in the Pediatric and Adolescent Endocrine Practice. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2017, 14, 364–370.

- Han, X.; McShane, M.; Sahertian, R.; White, C.; Ledger, W. Pre-mixing serum samples with assay buffer is a prerequisite for reproducible anti-Mullerian hormone measurement using the Beckman Coulter Gen II assay. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 1042–1048. [CrossRef]

- Pankhurst, M.W.; Chong, Y.H.; McLennan, I.S. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay measurements of antimüllerian hormone (AMH) in human blood are a composite of the uncleaved and bioactive cleaved forms of AMH. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 101, 846–850.e1. [CrossRef]

- Demirdjian, G.; Bord, S.; Lejeune, C.; Masica, R.; Rivière, D.; Nicouleau, L.; Denizot, P.; Marquet, P.-Y. Performance characteristics of the Access AMH assay for the quantitative determination of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels on the Access* family of automated immunoassay systems. Clin. Biochem. 2016, 49, 1267–1273. [CrossRef]

- van Helden, J.; Weiskirchen, R. Performance of the two new fully automated anti-Müllerian hormone immunoassays compared with the clinical standard assay. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 1918–1926. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K.; Long, M.; Prasad, J.; Wu, Y.Y.; Bonifacio, M. Assessment of the Access AMH assay as an automated, high-performance replacement for the AMH Generation II manual ELISA. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2016, 14, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, S.M.; Pastuszek, E.; Kloss, G.; Malinowska, I.; Liss, J.; Lukaszuk, A.; Plociennik, L.; Lukaszuk, K. Two new automated, compared with two enzyme-linked immunosorbent, antimüllerian hormone assays. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 104, 1016–1021.e6. [CrossRef]

- Nencetti, C.; Sessa, M.R.; Vitti, P.; Anelli, M.C.; Tonacchera, M.; Agretti, P. Estradiol Serum Levels are Crucial to Understand Physiological/Clinical Setting in Both Sexes: Limits of Measurement of Low Estradiol and Evaluation of a Sensitive Immunoassay. 2019, 05. [CrossRef]

- Passing, H.; Bablok, W. A New Biometrical Procedure for Testing the Equality of Measurements from Two Different Analytical Methods. Application of linear regression procedures for method comparison studies in Clinical Chemistry, Part I. J. Clin. Chem. Clin. Biochem. 1983, 21, 709–720. [CrossRef]

- Passing, H.; Bablok, W. Comparison of Several Regression Procedures for Method Comparison Studies and Determination of Sample Sizes Application of linear regression procedures for method comparison studies in Clinical Chemistry, Part II. cclm 1984, 22, 431–445. [CrossRef]

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986; 1: 307-310.

- Andreasson, U.; Perret-Liaudet, A.; van Waalwijk van Doorn, L.J.C.; Blennow, K.; Chiasserini, D.; Engelborghs, S.; Fladby, T.; Genc, S.; Kruse, N.; Kuiperij, H.B.; et al. A Practical Guide to Immunoassay Method Validation. Front. Neurol. 2015, 6, 179. [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute. Evaluation of detection capability for clinical laboratory measurement procedures; Approved guideline, CLSI document EP17-A2. P.A. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute, 2012.

- Rustamov, O.; Smith, A.; Roberts, S.A.; Yates, A.P.; Fitzgerald, C.; Krishnan, M.; Nardo, L.G.; Pemberton, P.W. Anti-Mullerian hormone: poor assay reproducibility in a large cohort of subjects suggests sample instability. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 3085–3091. [CrossRef]

- Fleming, R.; Fairbairn, C.; Blaney, C.; Lucas, D.; Gaudoin, M. Stability of AMH measurement in blood and avoidance of proteolytic changes. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2013, 26, 130–132. [CrossRef]

- Rustamov, O.; Smith, A.; Roberts, S.A.; Yates, A.P.; Fitzgerald, C.; Krishnan, M.; Nardo, L.G.; Pemberton, P.W. The Measurement of Anti-Müllerian Hormone: A Critical Appraisal. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 723–732. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).