Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Study Area and Datasets

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Datasets

| Parameter | DInSAR | SBAS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band | L | |||

| Wavelength (cm) | 23.8cm | |||

| Azimuth/Range pixel spacing | 4.65m/1.67m | |||

| Polarization | HH | |||

| Acquisition time | June 2023-Dec. 2024 | July 2023- Feb. 2025 | ||

| Orbit direction | Ascending | Descending | Ascending | Descending |

| Number of data | 1,428 | 1,372 | 540 | 1,176 |

3. Production Methods and Minimum Detectable Deformation Velocity Gradients

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Analysis of DInSAR and SBAS Results

| Hazards identified by DInSAR | Hazards identified by SBAS | Hazards identified only by SBAS |

|---|---|---|

| 1470 | 1620 | 150 |

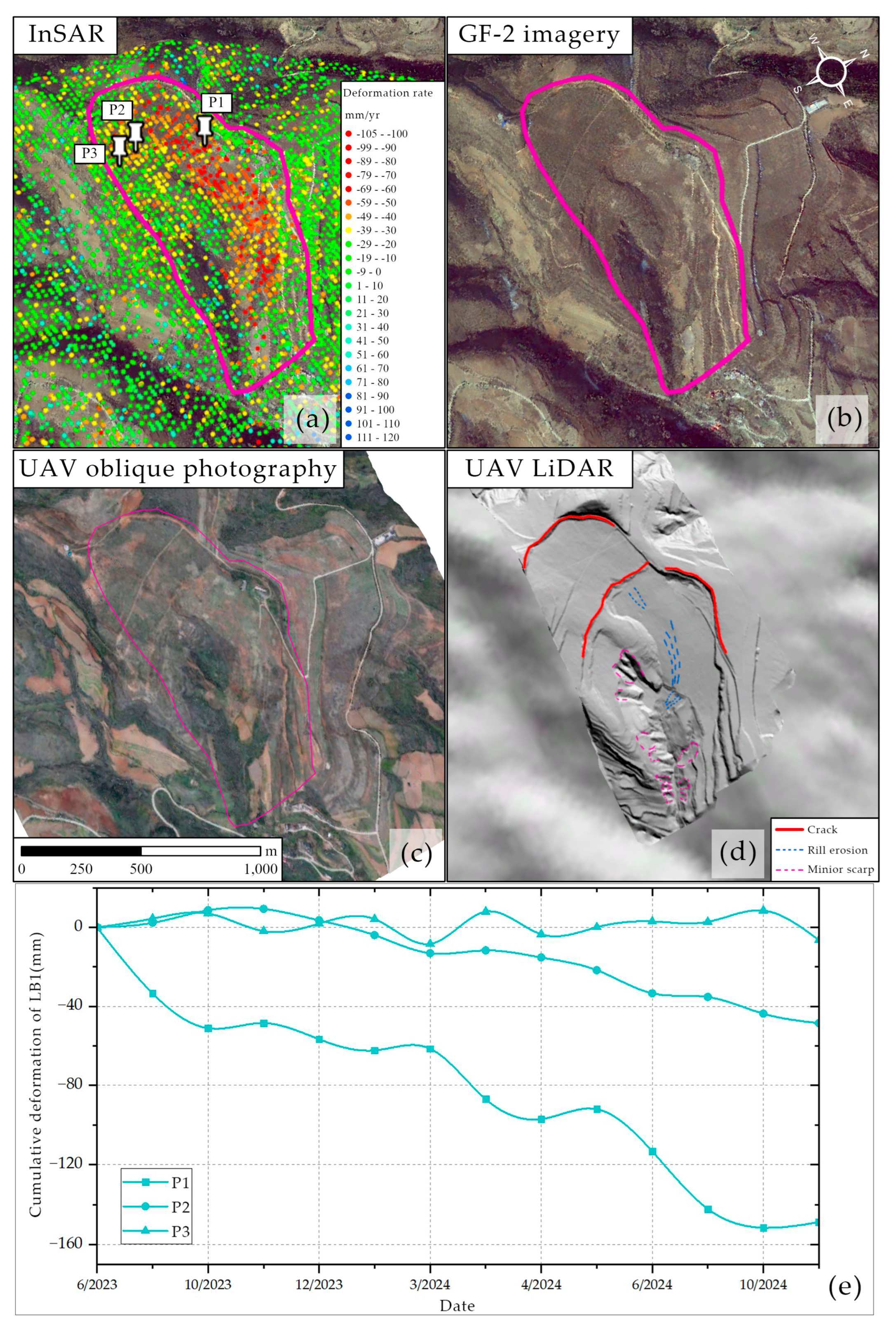

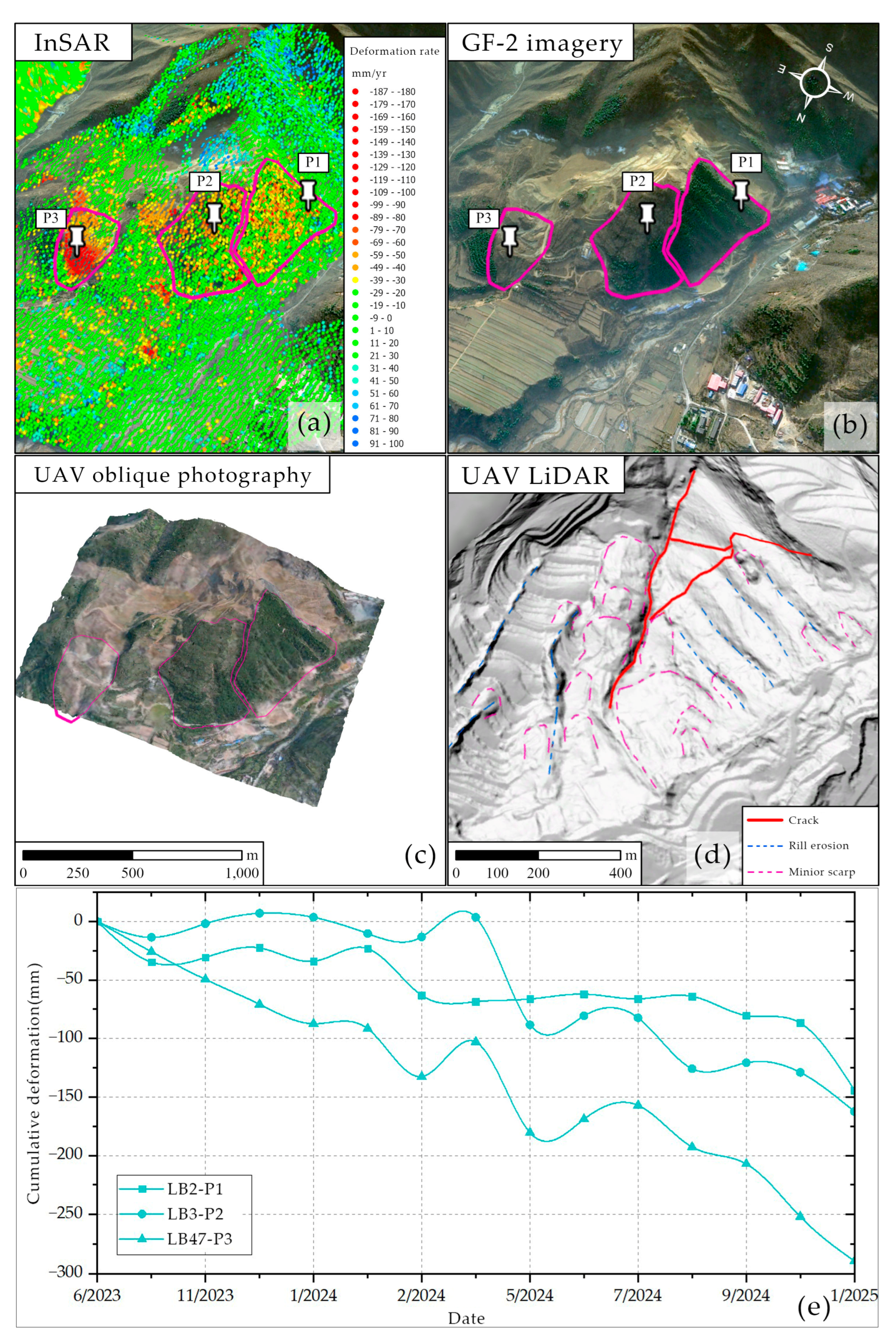

4.2. Detailed Investigation of Typical Geohazards

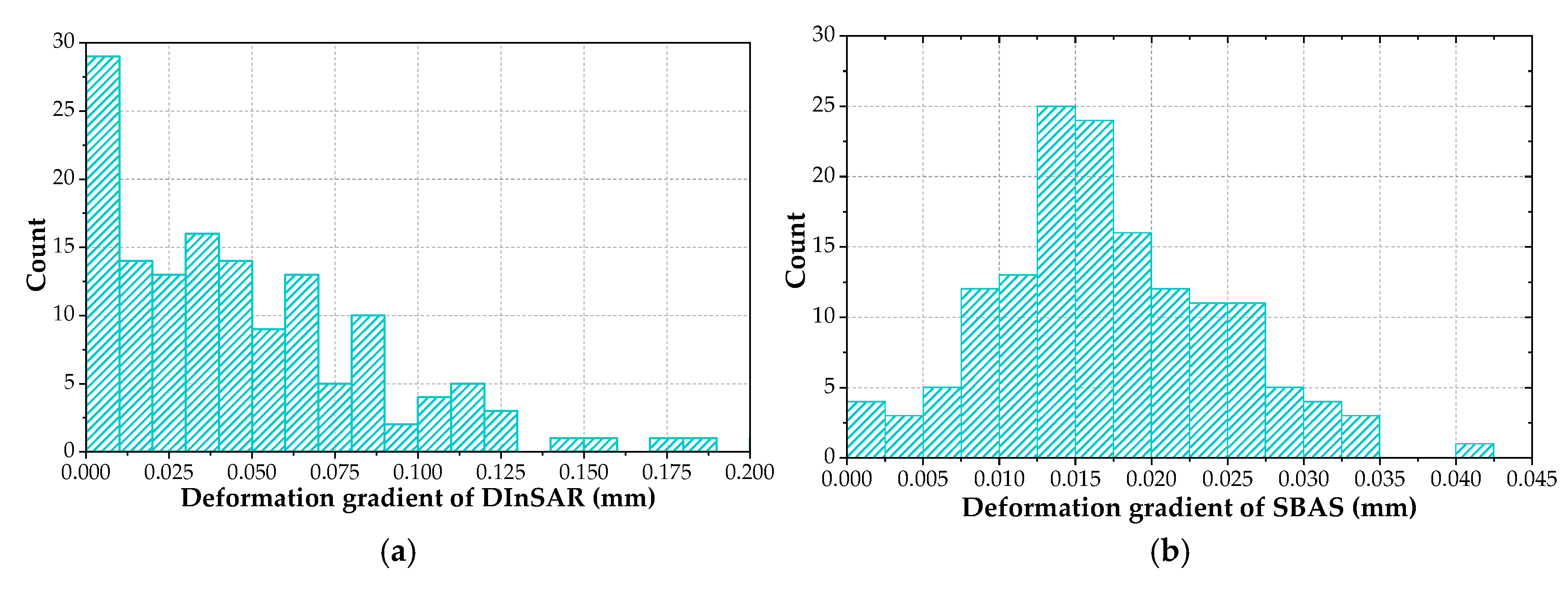

4.3. The Minimum Detectable Deformation Gradients of DInSAR and SBAS

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, X.; Li, T.; Chen, J.; Wei, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Lu, J.; et al. Twin-Satellite Constellation Design and Realization for Terrain Mapping and Deformation Monitoring: LuTan-1. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2025, vol. 63, pp. 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, K.; Liu, D.; Ou, N.; Yue, H.; Chen, Y.; Yu, W.; Liang, D.; Cai, Y. LuTan-1: An Innovative L-band Spaceborne Bistatic Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar Mission. IEEE Geoscience And Remote Sensing Magazine 2024. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Tang, X.; Li, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y. Classification of foundational deformation products for L - band differential interferometric SAR satellites[J]. Journal of Surveying and Mapping 2023, 52(5), 770 - 779.

- Tomás, R.; Li, Z. Earth Observations for Geohazards: Present and Future Challenges. Remote Sensing 2017, 9, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ci, H.; Yang, H.; Wang, R.; Yan, Z. Rainfall-Induced Geological Hazand Susceptibility Assessmentin the Henan Section ofthe Yellow River Basin: Multi-Model Approaches Supporting Disaster Mitigation and Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Liao, M.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Tang, M.; Gong, J. Detection and displacement characterization of landslides using multi-temporal satellite SAR interferometry: A case study of Danba County in the Dadu River Basin. Engineering Geology 2018, 240, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Niu, R.; Si, R.; Li, J. Geological Hazard Susceptibility Analysis and Developmental Characteristics Based on Slope Unit, Using the Xinxian County, Henan Province as an Example. Sensors 2024, 24, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Xie, H.; Wen, G. The susceptibility zoning of rainfall - type geological hazards in Henan Province based on erosion cycle theory[J]. Journal of North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power (Natural Science Edition) 2024, 45(4), 92-101. [CrossRef]

- Casu, F.; Manzo, M.; Lanari, R. A quantitative assessment of the SBAS algorithm performance for surface deformation retrieval from DInSAR data. Remote Sensing of Environment 2006, 102, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, A.; Darwish, N.; Koch, M. Minimizing the Residual Topography Effect on Interferograms to Improve DInSAR Results: Estimating Land Subsidence in Port-Said City, Egypt. Remote Sensing 2017, 9, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, I.; Stewart, M.; Claessens, S. A new functional model for determining minimum and maximum detectable deformation gradient resolved by satellite radar interferometry. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2005, 43, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Li, Z.W.; Ding, X.L.; Zhu, J.J.; Feng, G.C. Modeling minimum and maximum detectable deformation gradients of interferometric SAR measurements. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2011, 13, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, A.; Prati, C.; Rocca, F. Permanent scatterers in SAR interferometry. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2001, 39, 8−20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q. Understanding and Consideration of Related Issues in Early Identification of Potential Geohazards. Geomatics and Information Science of Wuhan University 2020, 45, 1651–1659. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, T.; Fan, H.; Xu, Y.; Li, P.; Tian, Z. Mining Deformation Monitoring Based on Lutan-1 Monostatic and Bistatic Data. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calò, F.; Ardizzone, F.; Castaldo, R.; Lollino, P.; Tizzani, P.; Guzzetti, F.; Lanari, R.; Angeli, M.-G.; Pontoni, F.; Manunta, M. Enhanced landslide investigations through advanced DInSAR techniques: The Ivancich case study, Assisi, Italy. Remote Sensing of Environment 2014, 142, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Zhang, L.; Tang, M.; Liao, M.; Xu, Q.; Gong, J.; Ao, M. Mapping landslide surface displacements with time series SAR interferometry by combining persistent and distributed scatterers: A case study of Jiaju landslide in Danba, China. Remote Sensing of Environment 2018, 205, 180–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhao, C.; Wang, B.; Peng, M.; Bai, L. Evolution of spatiotemporal ground deformation over 30 years in Xi’an, China, with multi-sensor SAR interferometry. Journal of Hydrology 2023, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, K.; Shen, Y.; Wu, M.; Feng, W.; Dong, X.; Zhuo, G.; Yi, X. ldentification of potential landslides in Baihetan Dam area before theimpoundment by combining InSAR and UAV survey. Acta Geodaetica et Cartographica Sinica 2022, 51, 2069–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, G. Study on the development characteristics and distribution law of geological hazards in Lingbao City. Chinese Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 2017, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Zhang, Y. Characteristics, distribution and prevention countermeasures of geological hazards in Lingbao City, Henan Province. Journal Of Henan Polytechnic University 2006, Vol.25 No. [CrossRef]

- Bureau., L.N.R.a.P. Bureau., L.N.R.a.P. Lingbao Natural Resources and Planning Bureau Announces Existing Geological Disaster Hazard Points. Available online: https://www.lingbao.gov.cn/21820/616970880/1883707.html.

- Zhou, B.; Xie, H.; Wen, G. The susceptibility zoning of rainfall type geological hazardsin henan province based on erosion cycle theory. Joumal of North China University of Water Resources and Eleetrie Power ( Natural Seience Edition) 2024, 45 (4), 92-101. [CrossRef]

- Zhenbo, N. Exploration of Mine Geological Environment Control Scheme in Xiaoqinling Mining Area of Henan Province. World nonferrous metals 2019, 1002-5065(2019)01-0170-2.

- Hu, L.; Tomás, R.; Tang, X.; Vinielles, J.L.; Herrera, G.; Li, T.; Liu, Z. Updating Active Deformation Inventory Maps in Mining Areas by Integrating InSAR and LiDAR Datasets. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Dong, X.; Li, W. Early identification and monitoring and early warning of major geological hazards based on space-air-ground integration. Geomatics and Information Science of Wuhan University 2019, Vol.44 No.7. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).