Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Research Importance and Objectives

- Synthesize two oxazolone derivatives and confirm their structures using IR and mass spectroscopy.

- Calculate the permanent dipole moment of the ground electronic state using a benzene solution in a capacitor.

- Determine the dipole moment of the excited electronic state using fluorescence and absorption spectra in solvents of varying polarity.

- Study Stokes shifts in solvents with different dielectric constants.

- Analyze electronic absorption spectra in hexane and methanol to investigate the electronic effects of substituents on energy levels and charge transfer mechanisms.

- Data deconvolution in hexane using Gaussian analysis.

- Compute geometric configurations and energetic constants using the PM3 wavefunction in MOPAC.

3. Instruments Used

- FS-2 fluorescence spectrophotometer (SCINCO).

- LCR meter for capacitance measurement.

- UV-VIS double-beam spectrophotometer (PG Instruments Ltd., Model T90).

- FT-IR spectrometer (JASCO, Model 4200).

4. Materials Used

- Hippuric acid (Alfa Aesar, 99% purity).

- Benzaldehyde (SCP, 97% purity).

- 4-Chlorobenzaldehyde (SIGMA-ALDRICH, 97% purity).

- 4-Methoxybenzaldehyde (Alfa Aesar, 98% purity).

- 4-Nitrobenzaldehyde (Alfa Aesar, 99% purity).

- Glacial acetic acid (99% purity).

- Acetic acid (95% purity).

- Acetonitrile (Lap-Scan, 99.8% purity).

- Ethanol (SIGMA-ALDRICH, 99.8% purity).

- Ethyl acetate (99% purity).

- Chloroform (95% purity).

- n-Hexane (Acros Organics, 99% purity).

- Methanol (Laboratory Rasayan, 99.5% purity).

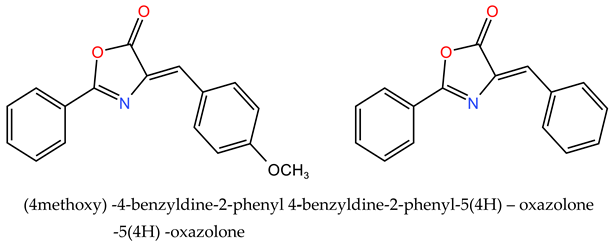

4-1-. Synthesis of Compounds

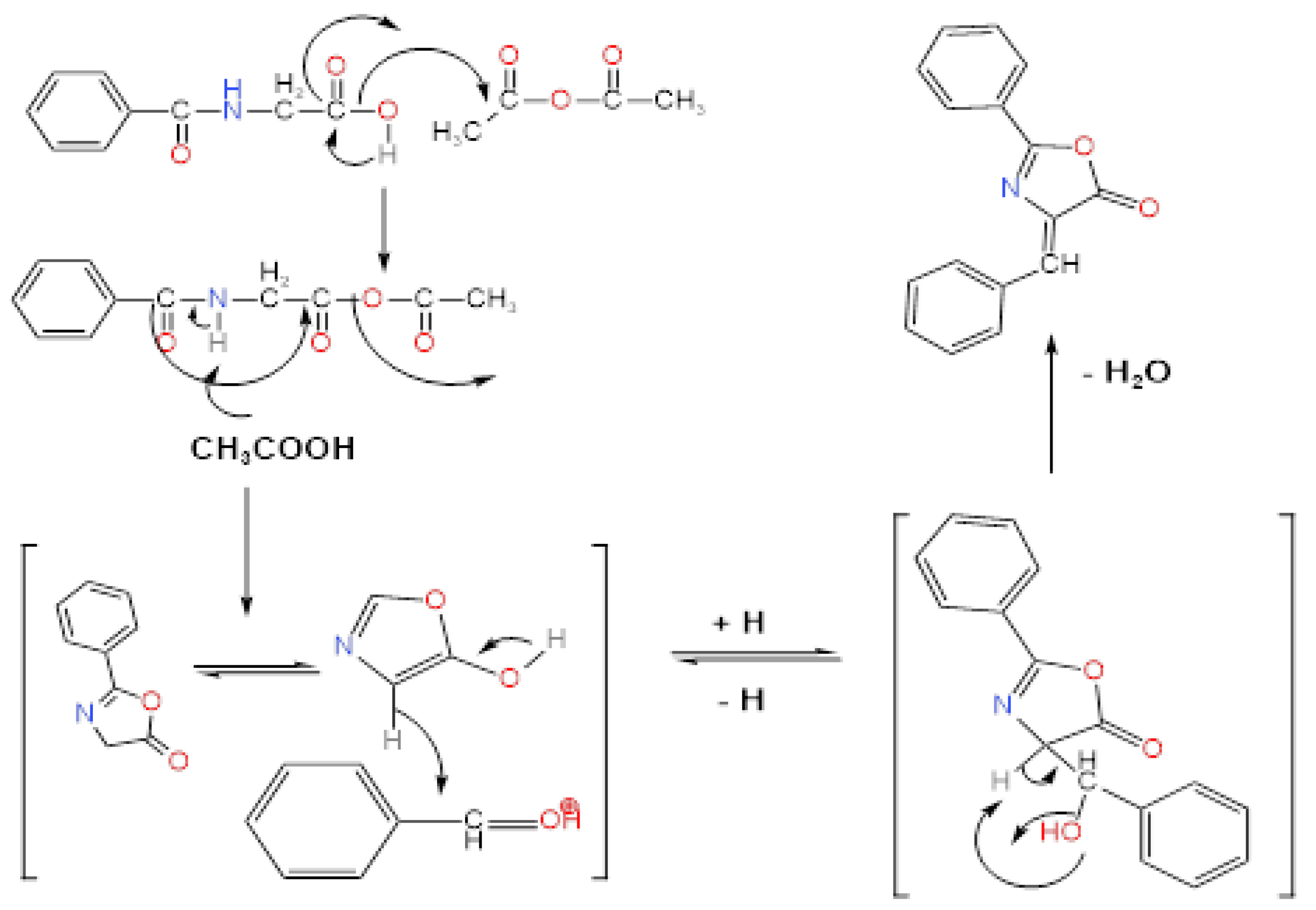

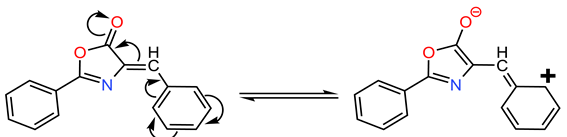

4-2-. Mechanism:

- Deprotonation: Hippuric acid reacts with acetic anhydride, undergoing deprotonation of the amide group (–NH–) to form a reactive carboxylate anion.

- Cyclization: The nucleophilic oxygen attacks the adjacent carbonyl carbon, leading to ring closure and formation of an unstable oxazolone intermediate.

- Benzaldehyde addition: The intermediate reacts with benzaldehyde in acetic acid medium, with subsequent proton abstraction to generate a new intermediate compound.

- Dehydration: Water elimination occurs via condensation, yielding the final stable oxazolone derivative product.

5-. Physical Properties of Synthesized Compounds:

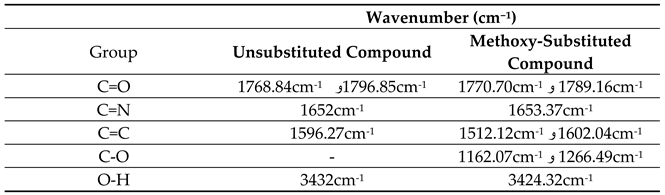

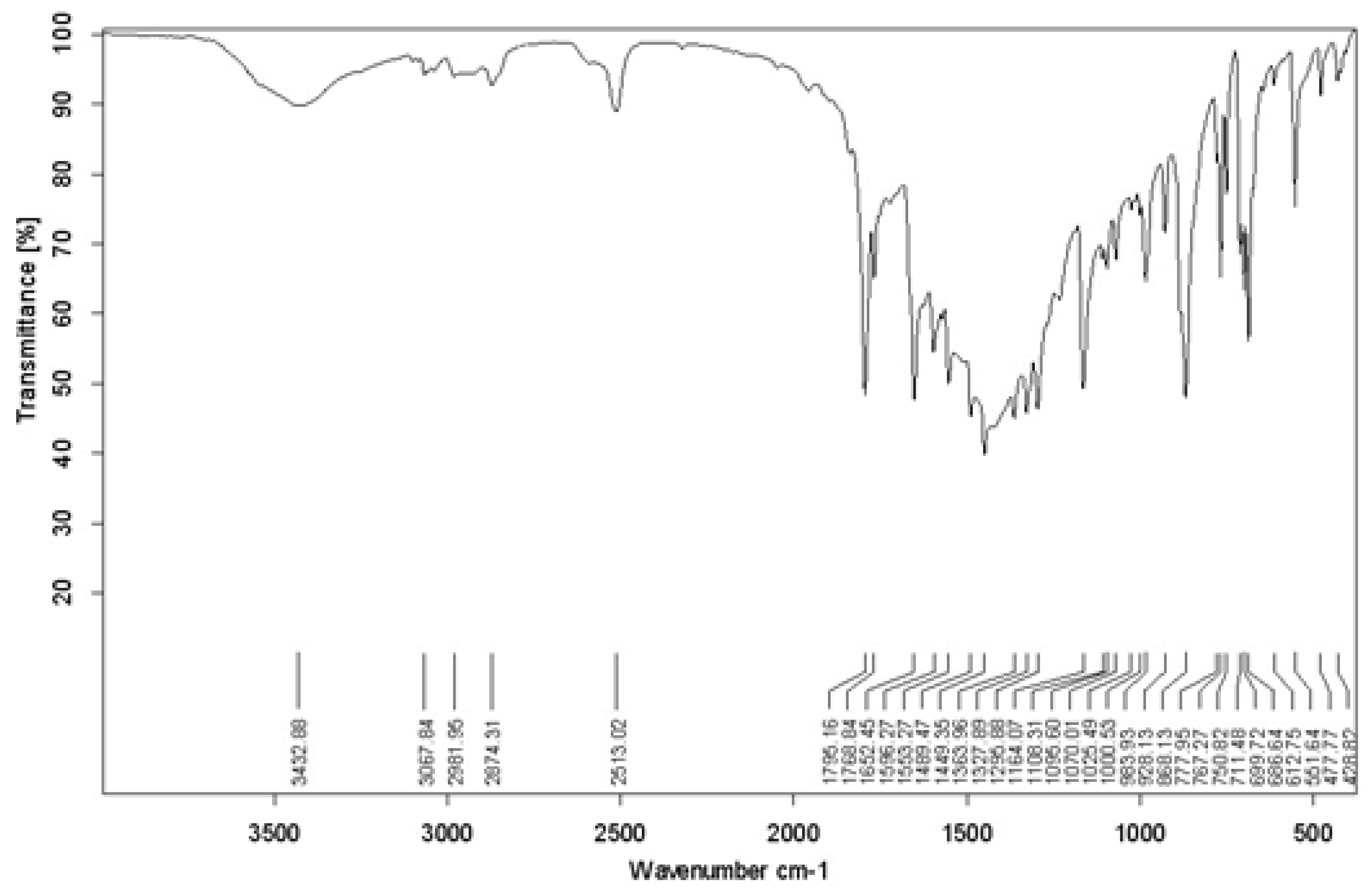

5. -1-IR Spectra

- A peak at 3432 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the O-H stretching vibration, indicating free or hydrogen-bonded hydroxyl groups.

- Peaks at 1796.85 cm⁻¹ and 1768.84 cm⁻¹ correspond to C=O stretching, characteristic of the oxazolone ring. The presence of two peaks suggests multiple tautomeric forms or interactions with the environment.

- A peak at 1652 cm⁻¹ corresponds to C=N stretching, part of the heterocyclic oxazolone ring.

- A peak at 1596.27 cm⁻¹ corresponds to C=C stretching in aromatic rings (benzene rings).

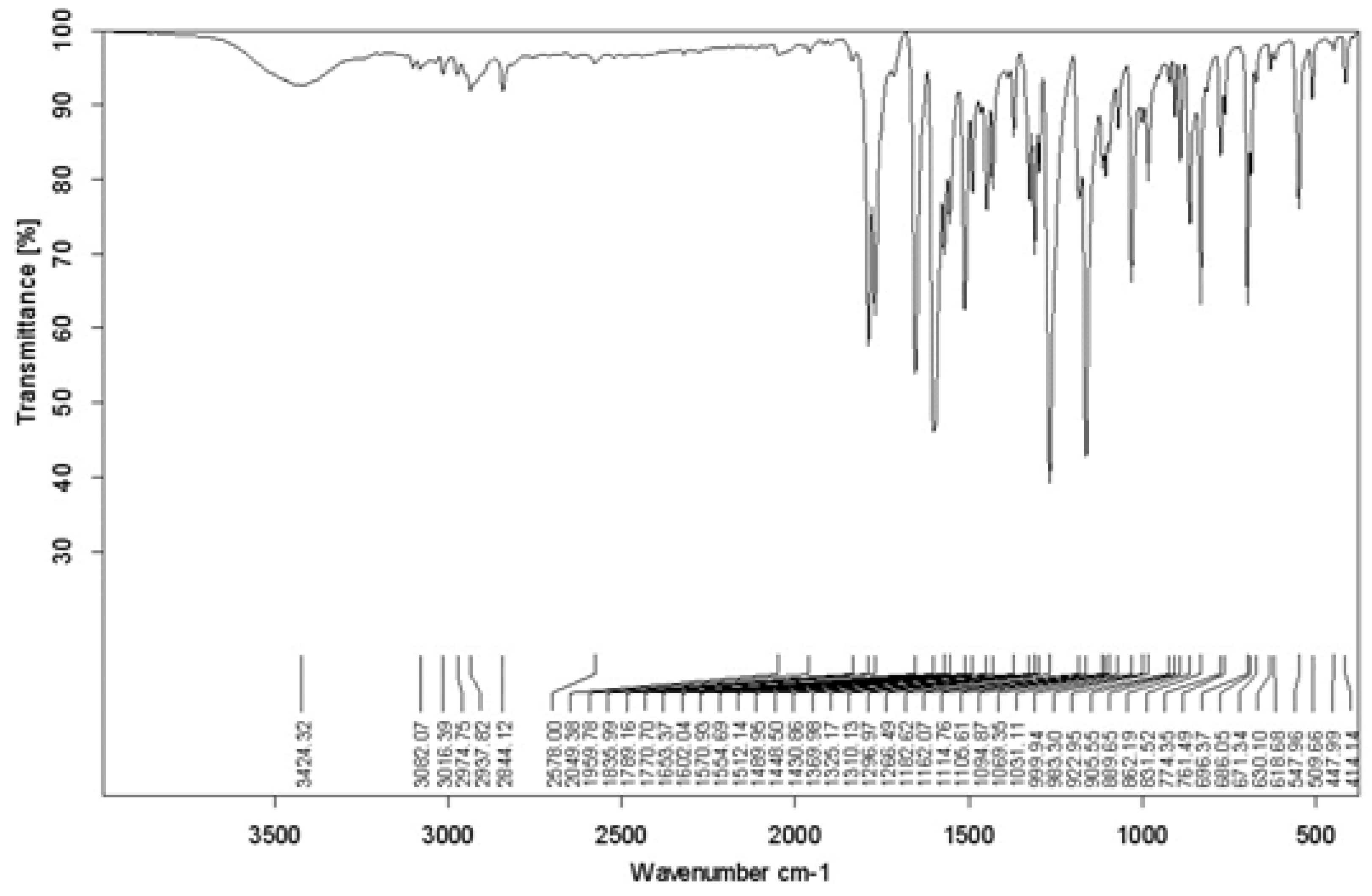

- A peak at 3424.32 cm⁻¹ corresponds to O-H stretching, with a slight shift compared to the unsubstituted compound due to the methoxy group's effect.

- Peaks at 1789.16 cm⁻¹ and 1770.7 cm⁻¹ correspond to C=O stretching, with slight shifts due to the methoxy group.

- A peak at 1653.37 cm⁻¹ corresponds to C=N stretching, with a small positional change compared to the unsubstituted compound.

- Peaks at 1602.04 cm⁻¹ and 1512.12 cm⁻¹ correspond to C=C stretching in aromatic rings, with shifts due to the methoxy group.

- Distinctive peaks at 1266.49 cm⁻¹ and 1162.07 cm⁻¹ correspond to C-O stretching in the methoxy group, a hallmark of this substituent [9].

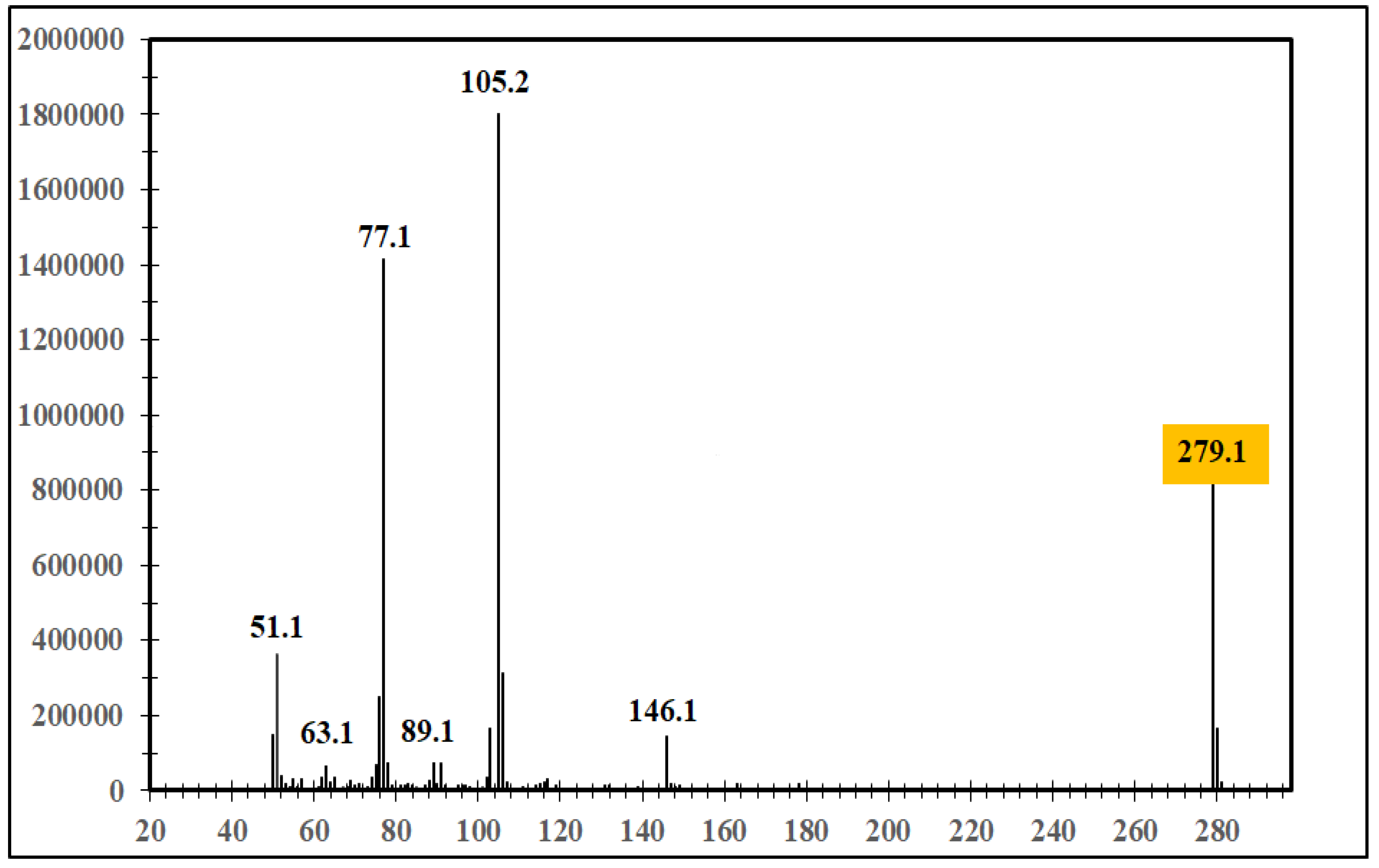

5. -2-Mass Spectra

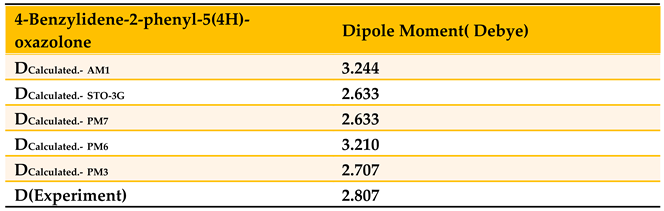

6-. Calculation of Dipole Moment for Ground Electronic State

- M: Molar mass

- ρ: Density

- k: Dielectric constant

- NA: Avogadro's number

- ε0: Vacuum permittivity

- K: Boltzmann constant

- T: Absolute temperature

| -H | -OCH3 | |

|---|---|---|

| CP (Pico. farad) | 6.2095 | 6.7 |

| PM.10-4 (m3.mol-1) | 1.61 | 1.887 |

| µ(Debye) | 2.807 | 3.039 |

7-. Calculation of Dipole Moment for Excited Electronic State Using Fluorescence

7-1-. Fluorescence Spectra of Unsubstituted Oxazolone

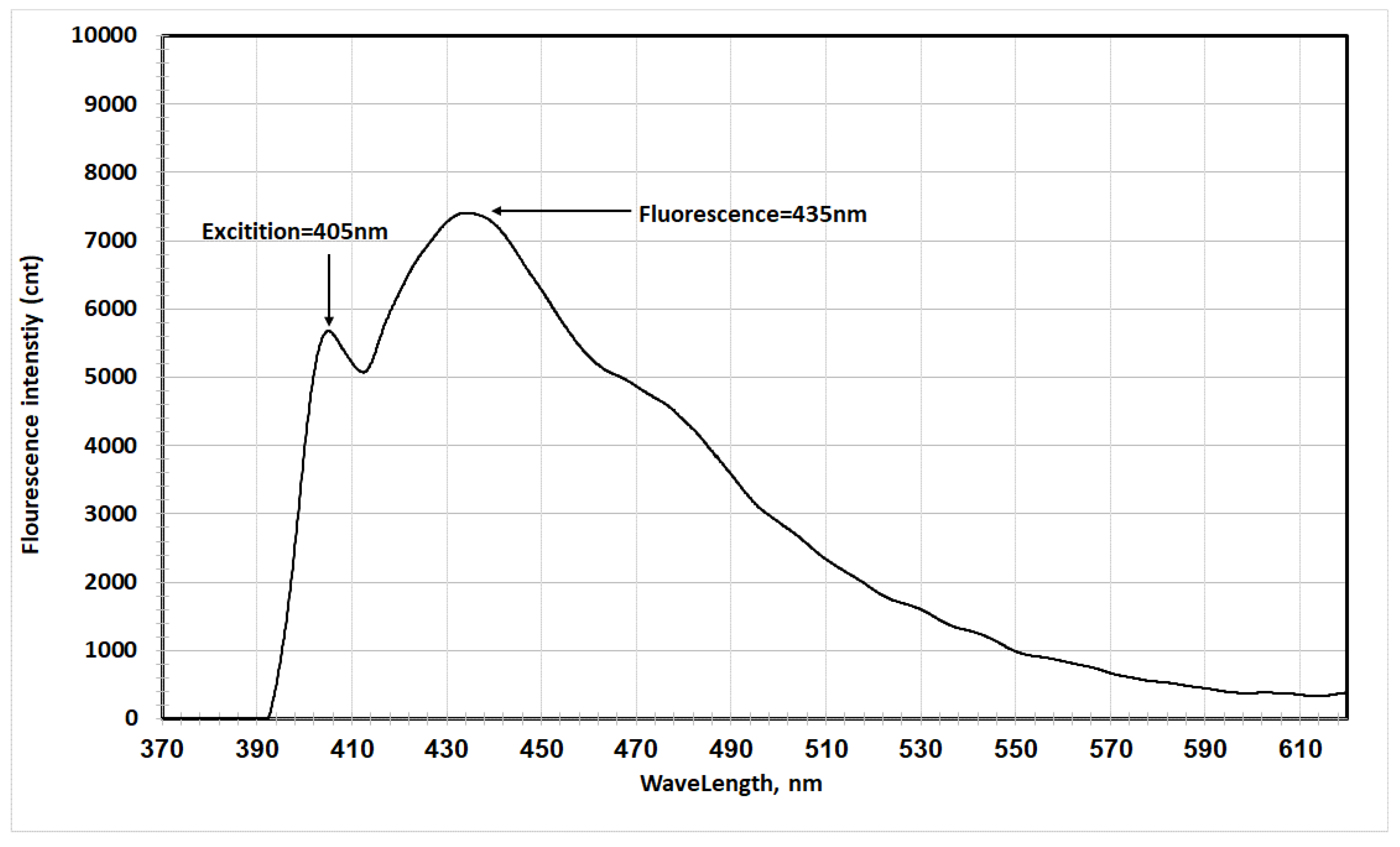

- In ethyl acetate: Excitation at 405 nm yielded a fluorescence peak at 435 nm, with a Stokes shift of 30 nm (Figure 7).

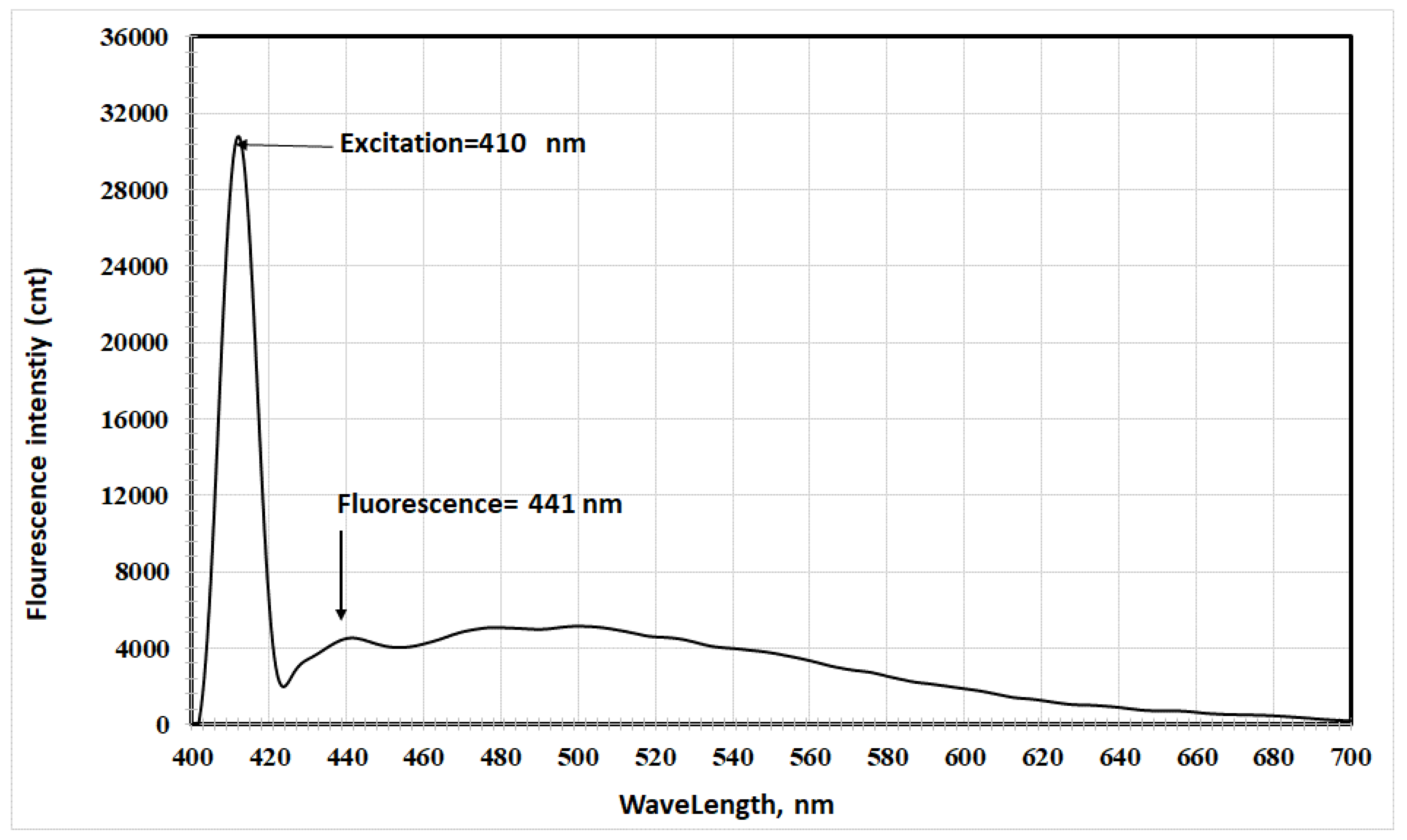

- In acetic acid: Excitation at 410 nm yielded a fluorescence peak at 441 nm, with a Stokes shift of 31 nm (Figure 8).

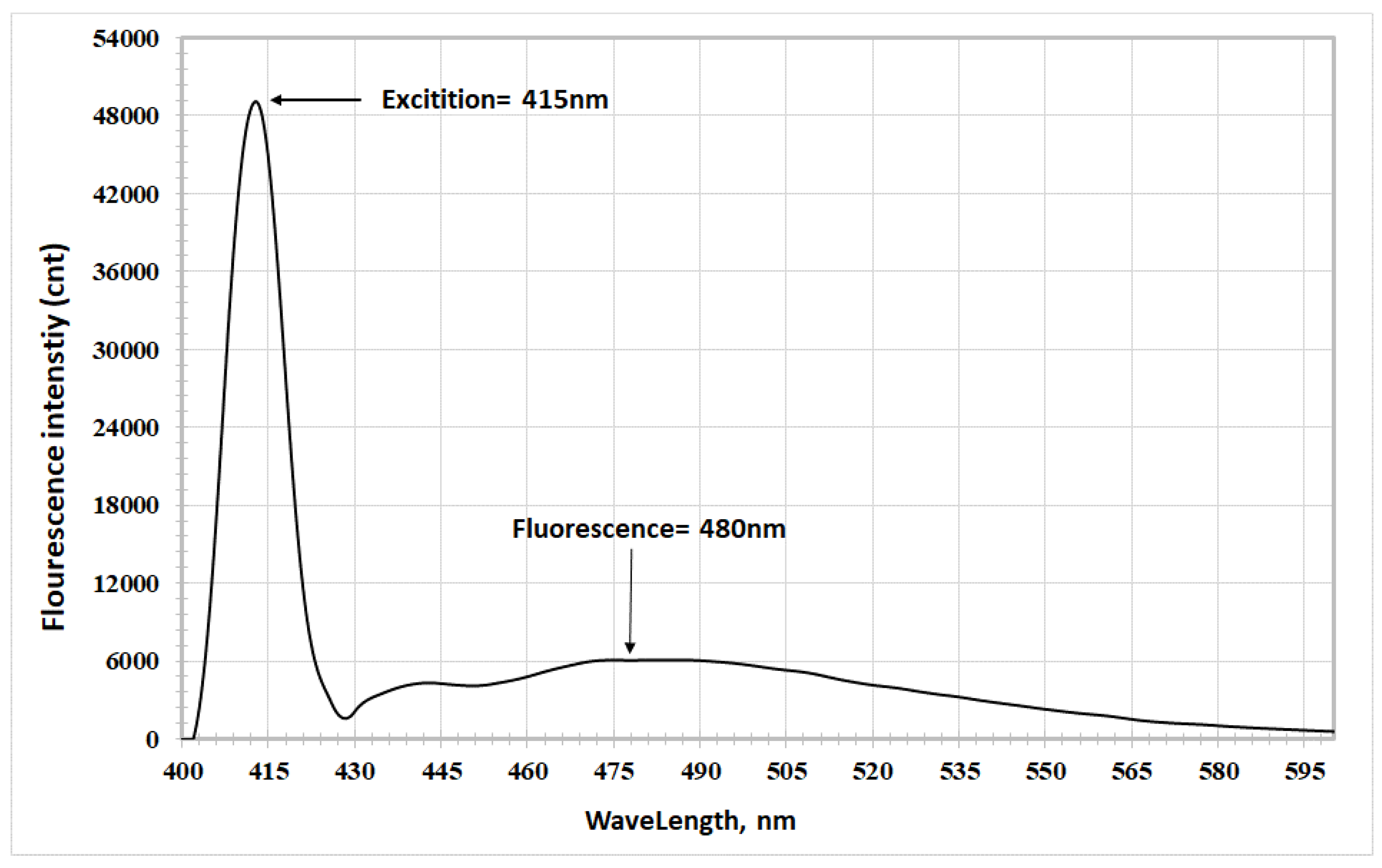

- In acetonitrile: Excitation at 415 nm yielded a fluorescence peak at 480 nm, with a Stokes shift of 65 nm (Figure 9).

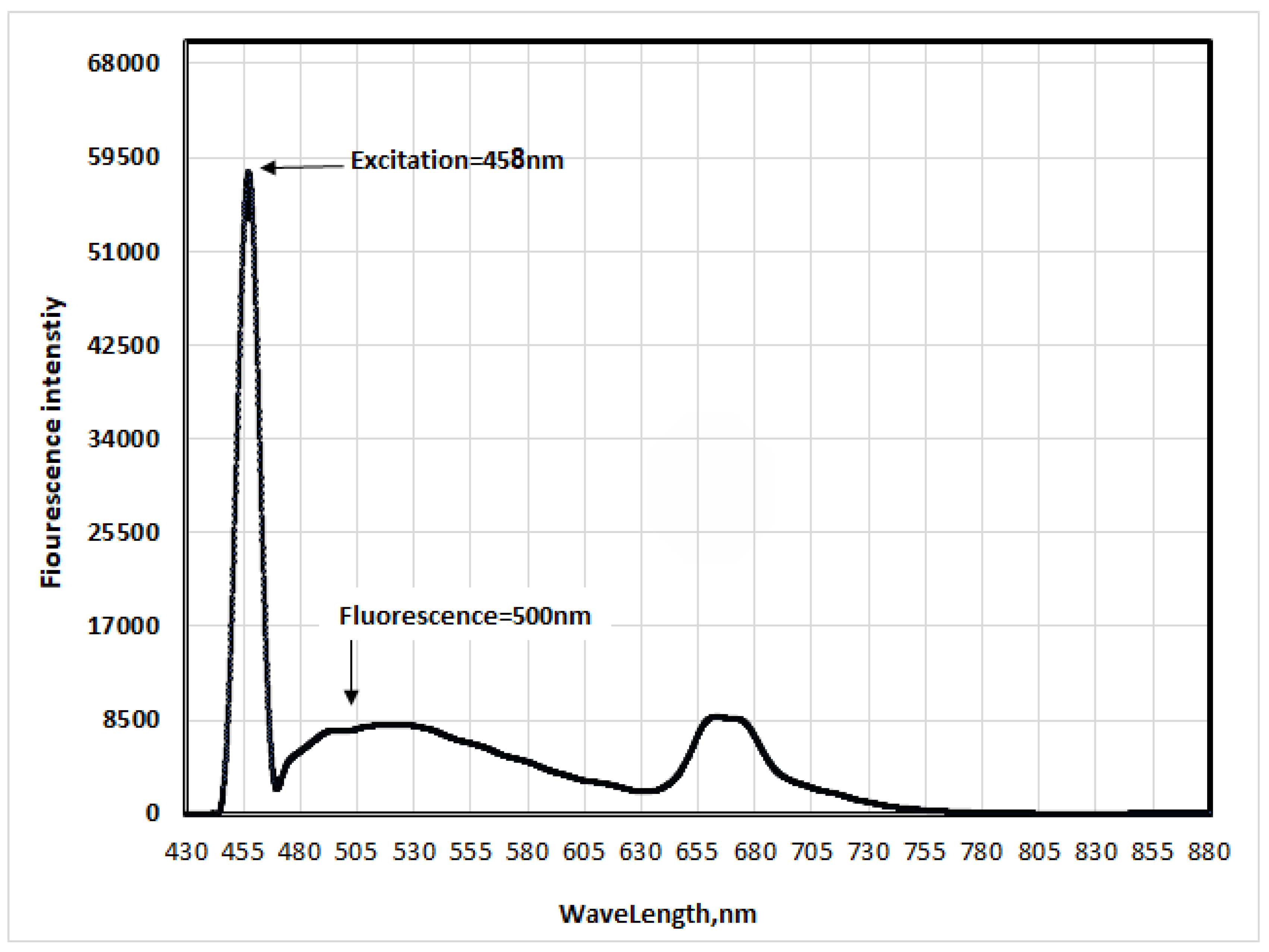

7-2-. Fluorescence Spectra of Methoxy-Substituted Oxazolone

|

Solvent |

unsubstituted | methoxy-substituted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

EXλ (nm) |

FLλ (nm) |

Stokes shift Δλ(nm) |

EXλ (nm) |

FLλ (nm) |

Stokes shift Δλ(nm) |

|

| ETHYL ACETATE | 405 | 435 | 30 | 457 | 450 | 25 |

| ACETIC ACID | 410 | 441 | 31 | 458 | 489 | 31 |

| ACETONITRIL | 415 | 480 | 65 | 461 | 496 | 35 |

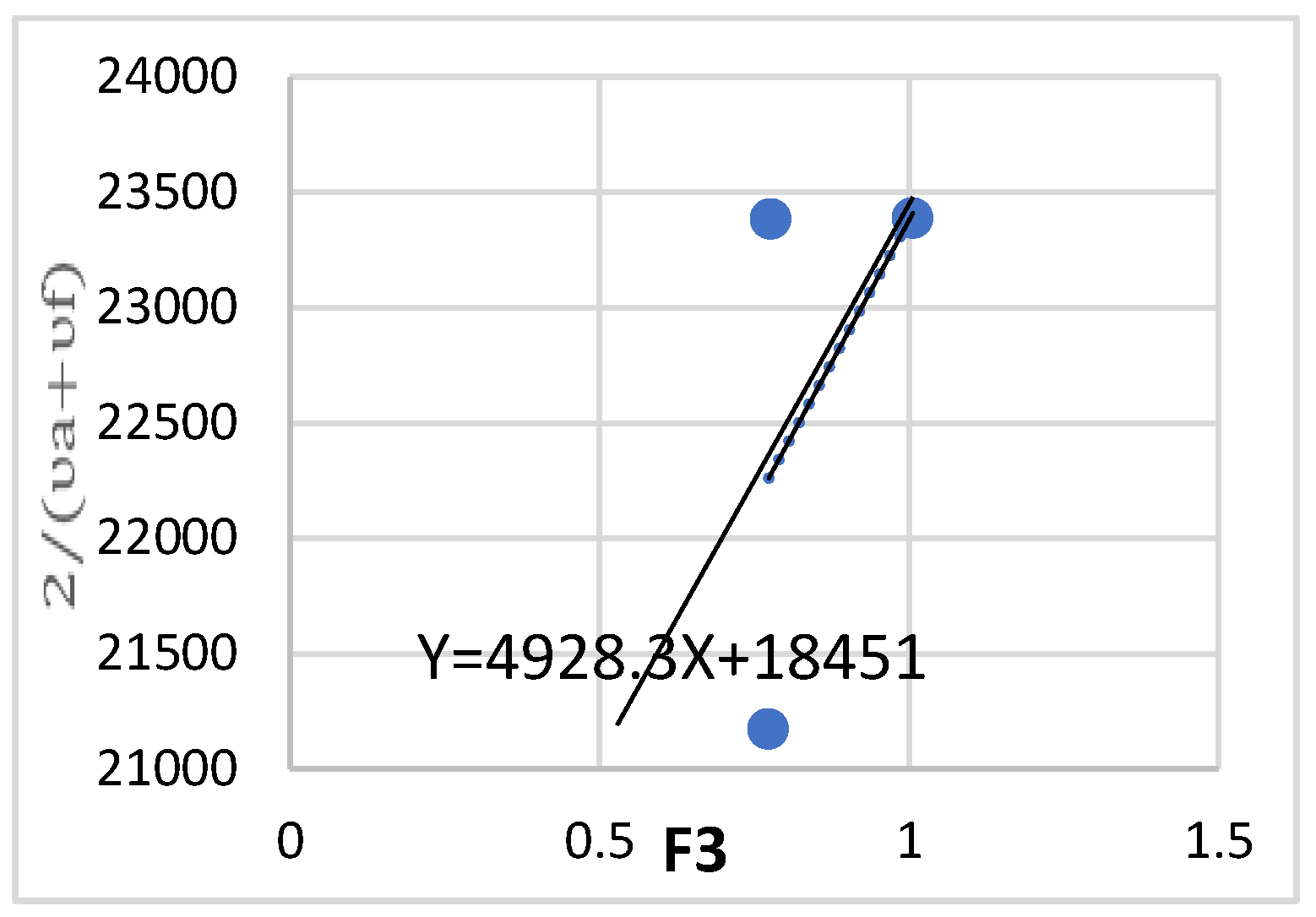

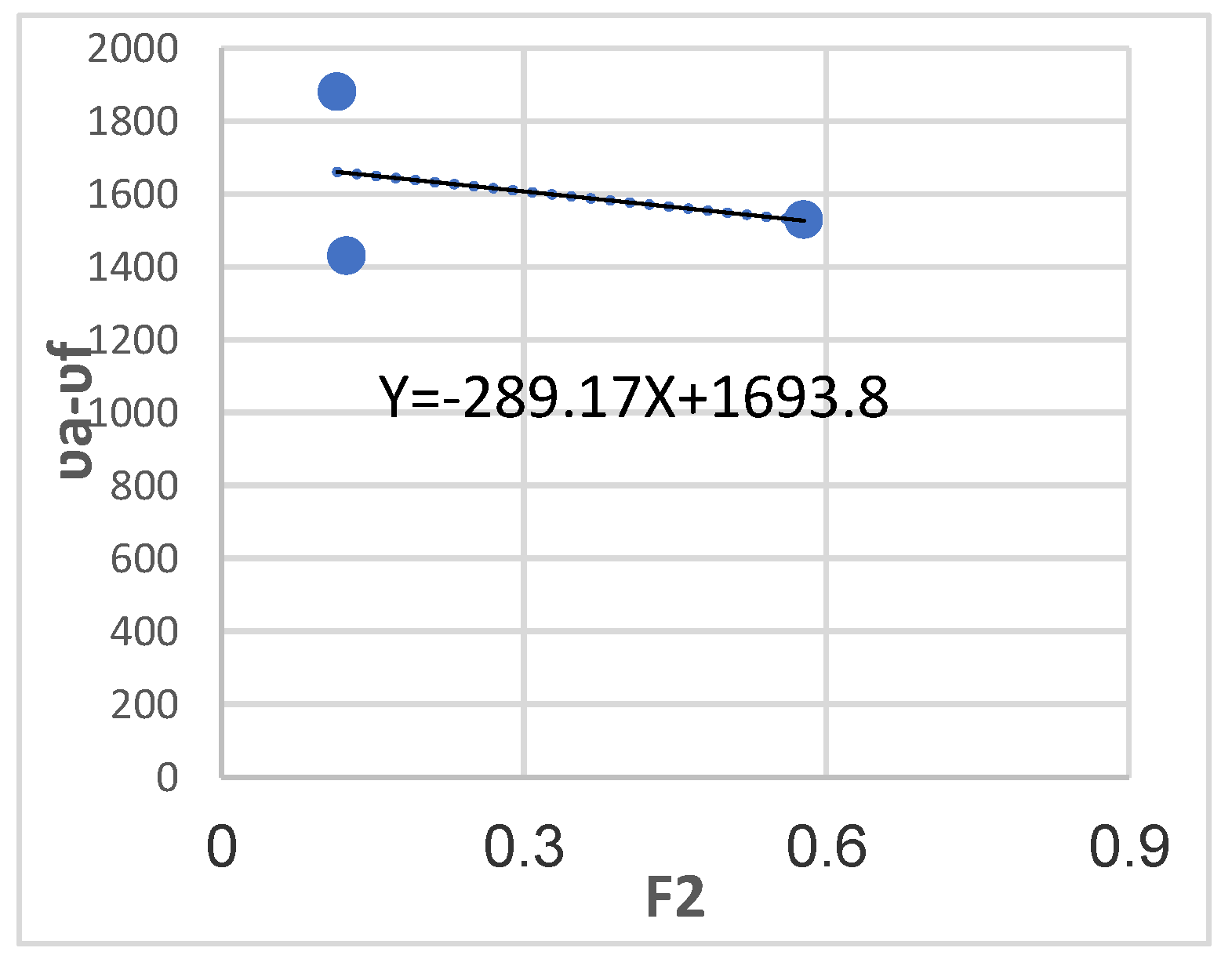

8-. Calculation of Dipole Moment for the Excited Electronic State:

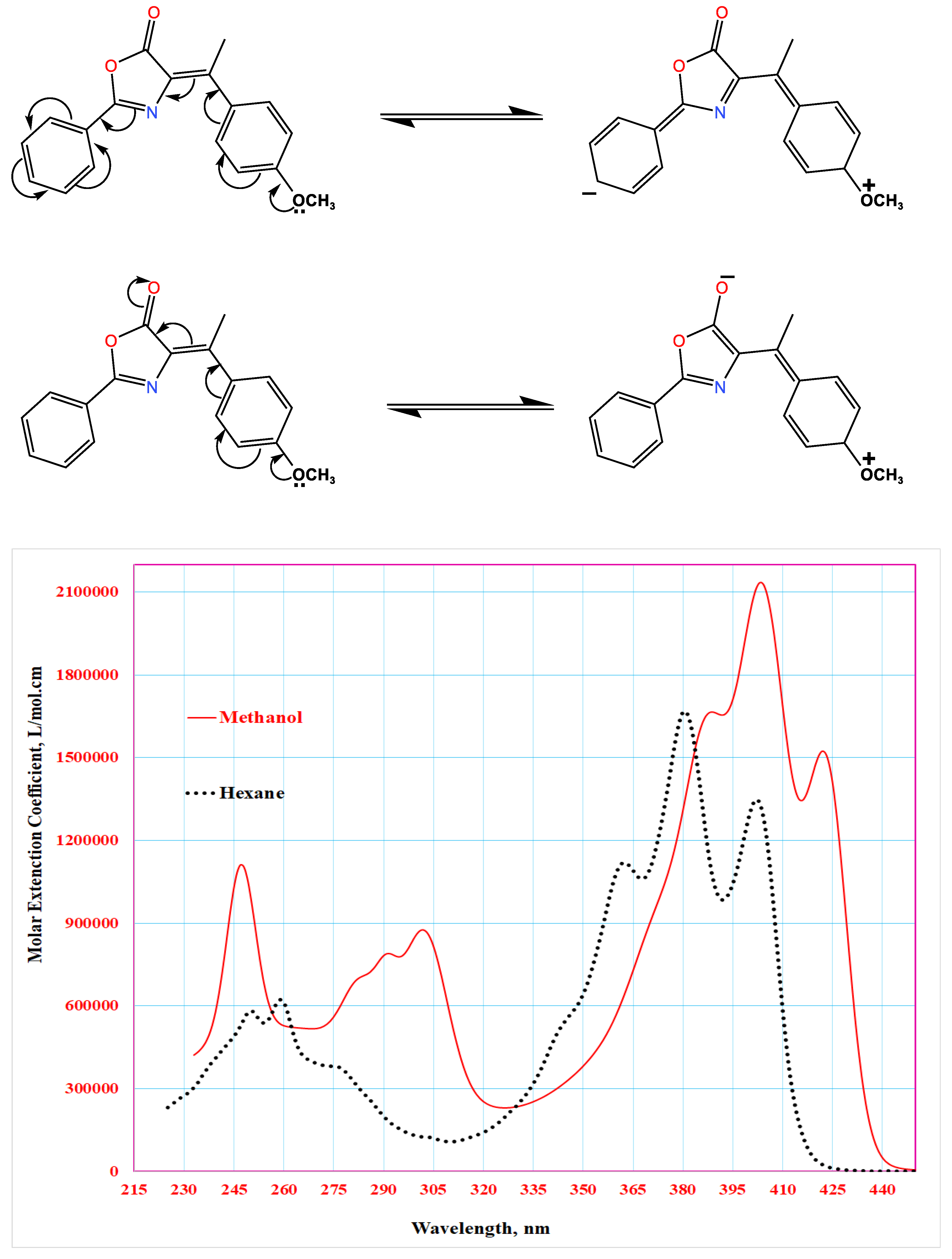

9. -Electronic Absorption Spectra Analysis:

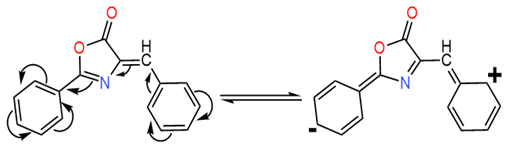

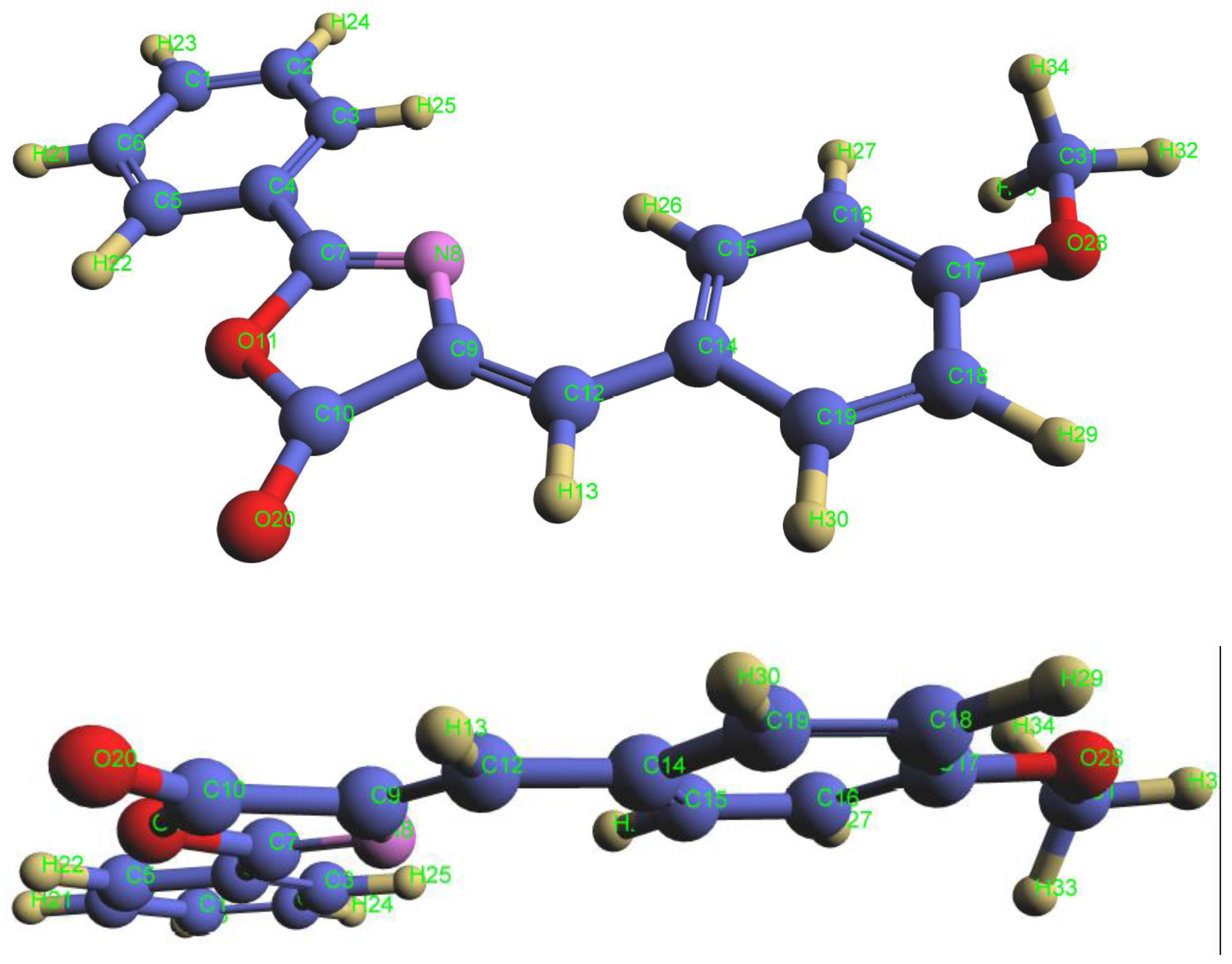

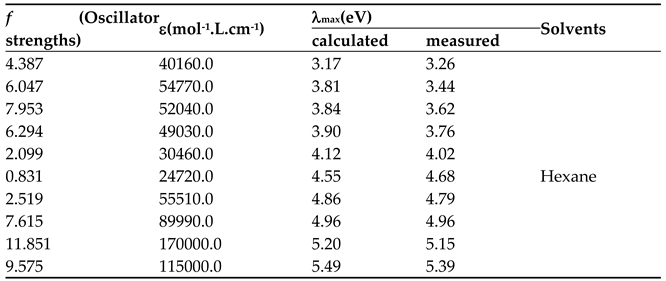

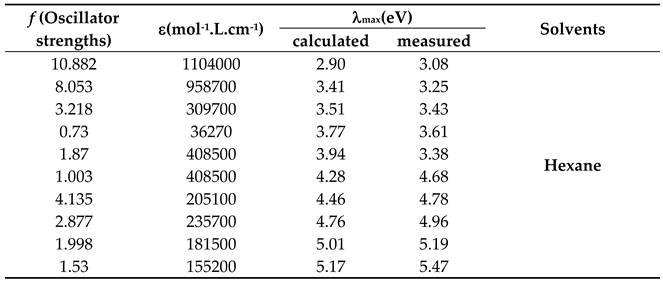

9-1-. For 4-Benzylidene-2-phenyl-5(4H)-oxazolone:

- A primary peak at 360 nm (attributed to the π→π* transition of the conjugated system)

- A secondary peak at 260 nm (likely due to localized aromatic transitions), as shown in Figure 17 for the n-hexane spectrum.

- −

- The primary resonance form (extended conjugation) corresponds to the main absorption band at 360 nm, exhibiting a redshift due to decreased energy transition.

- −

- The secondary resonance form (shorter conjugation) corresponds to the 260 nm band, showing a blueshift from reduced conjugation length.

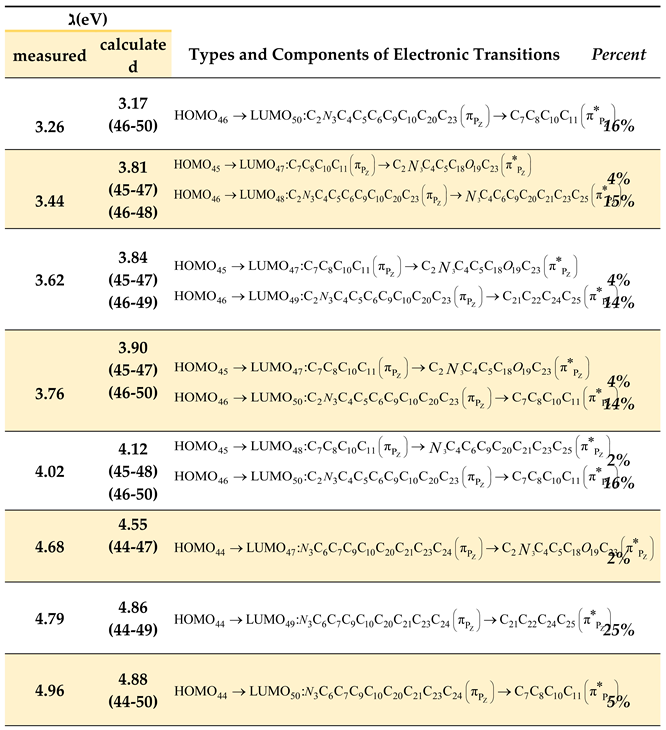

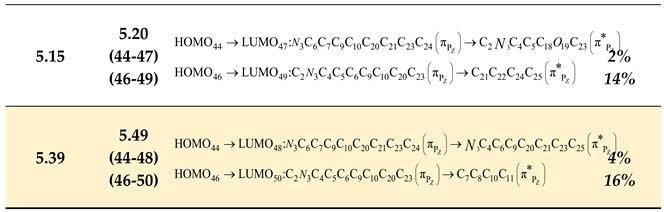

- The spectral band resulting from Gaussian deconvolution at 4.79 eV (theoretically calculated at 4.86 eV) shows a charge transfer percentage of approximately 25%. This represents the highest electronic charge transfer within the compound, occurring from the heterocyclic ring to the benzene ring on the right side of the heterocyclic ring. This transition results from the electronic excitation from bonding molecular orbital type number 44 (HOMO) to antibonding molecular orbital number 49 (LUMO).

- Another electronic transition with 15% contribution originates from the oxazolone ring which connected to the carbonyl group towards the benzene ring in the right section.

- Additionally, a relatively minor electronic transition of 5% occurs from the oxazolone ring connected to the carbonyl group towards the benzene ring. Notably, a 2% contribution indicates negligible electronic transition. This pattern explains the remaining electronic transitions, where most transitions occur from bonding orbitals 44, 45, and 46 to antibonding orbitals 47, 48, 49, and 50, representing the predominant contribution of these transitions.

- The table further demonstrates that most electronic transitions are not localized to specific functional groups but rather delocalized across the entire molecular framework. This observation aligns with the resonance structures interpreted through spectroscopic measurements of the compound, indicating significant electron delocalization throughout the molecular components.

- The theoretical computational results show excellent agreement with the measured spectra of the compound in solvents of varying polarity (methanol and n-hexane).

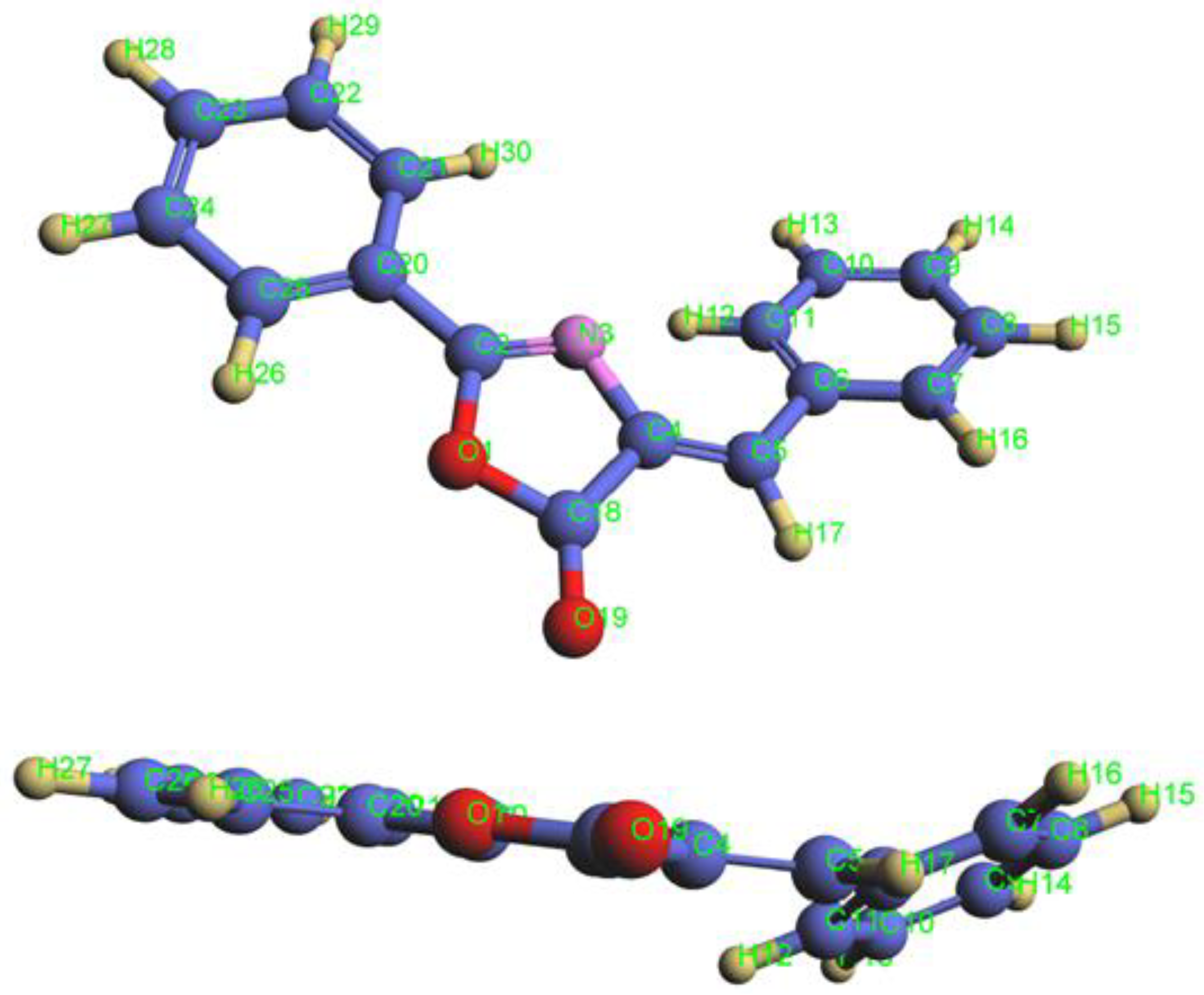

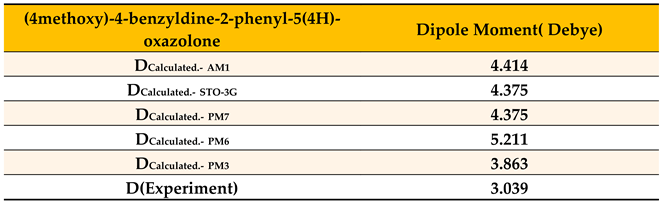

9. -2-The Absorption Spectrum and Electronic Structural Properties of the Compound (4-Methoxy)-4-benzylidene-2-phenyl-5(4H)-oxazolone:

- The spectral band obtained from Gaussian deconvolution at 3.08 eV (theoretically calculated at 2.90 eV) exhibits a charge transfer ratio of approximately 18%, directed toward the right side of the compound (bearing the methoxy group) from the oxazolone ring. This transition arises from the electronic excitation from bonding molecular orbital No. 52 (HOMO) to antibonding molecular orbital No. 55 (LUMO). Additionally, a 15% electronic transfer occurs from the oxazolone ring (linked to the carbonyl group) toward the benzene ring on the right side.

- The spectral band from Gaussian deconvolution at 4.66 eV (theoretically calculated at 4.28 eV) is localized by 27% on the left side of the compound, originating from the left benzene ring directly connected to the oxazolone ring and extending toward the benzene ring on the right terminus. This transition results from the excitation from bonding molecular orbital No. 50 (HOMO) to antibonding molecular orbital No. 54 (LUMO).

- A minor electronic transfer (5%) is observed from the left benzene ring (attached to the oxazolone) toward the benzene ring on the right terminus. Notably, a 1% contribution indicates negligible electronic transfer. Similar interpretations apply to other transitions, where most electronic excitations occur from bonding orbitals 50, 51, and 52 to antibonding orbitals 53, 54, 55, and 56, representing the dominant contributions.

- The table further reveals that most electronic transitions are not localized on specific functional groups but rather delocalized across the entire molecule, consistent with the resonance structures inferred from spectroscopic measurements. This suggests electron delocalization throughout the molecular framework.

- Experimental results demonstrate that the absorption spectra of the compound in solvents of different polarities (methanol and hexane) show no significant shift in spectral band positions (Figure 20). This behavior indicates that solvent polarity has no pronounced effect on the electronic properties of the compound, supporting the hypothesis that the oxazolone ring inhibits resonance effects.

Conclusions

- The methoxy-substituted oxazolone did not significantly alter dipole moments.

- Three primary spectral bands were observed at 380 nm, 360 nm, and 342 nm, indicating π→π* transitions.

- Three low-intensity bands at 260 nm, 247 nm, and 239 nm in methanol were attributed to n→π* transitions.

- A red shift was observed in methoxy-substituted oxazolone due to extended conjugation.

- No major geometric changes were observed, as confirmed by small Stokes shifts.

- calculations accurately predicted dipole moments and electronic transitions.

References

- Mehra, M.; Singh, R.; Kaker, S. Review on Chemistry of Oxazole Derivatives: Current to Future Therapeutic Prospective. Egypt. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2023, 10, 218–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szukalski, A.; Krawczyk, P.; Sahraoui, B.; Jędrzejewska, B. Multifunctional Oxazolone Derivative as an Optical Amplifier, Generator, and Modulator. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 1742–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowri, M.R.; Ranganathan, M.; Ramanathan, G. Solvent Polarity Induces Significant Bathochromic Shift on (4Z,4'Z)-4,4'-(((Phenylazanediyl)bis(4,1-phenylene))bis(methaneylylidene))bis(2-phenyloxazol-5(4H)-one). Res. Sq. 2023, 2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jędrzejewska, B.; Krawczyk, P.; Józefowicz, M. Experimental and Theoretical Studies of the Influence of Solvent Polarity on the Spectral Properties of Two Push-Pull Oxazol-5-(4H)-one Compounds. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2017, 171, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, A.; Wong, A.R.; Lamb, J.R. Chemically Recyclable, High Molar Mass Polyoxazolidinones via Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. ACS Macro Lett. 2024, 13, 1655–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siragusa, F.; Crane, L.; Stiernet, P. Continuous Flow Synthesis of Functional Isocyanate-Free Poly(oxazolidone)s by Step-Growth Polymerization. ACS Macro Lett. 2024, 13, 1785–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.C.T.; Zhou, M.-H.; Tseng, S.-F. Facile Fabrication of Oxygen-Enriched MXene-Based Sensor and Their Ammonia Gas-Sensing Enhancement. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 10, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, Z.Y.; Magtoof, M.S. Synthesis, Characterization of Novel 4-Arylidene-2-Phenyl-5(4H) Oxazolones. Eur. Chem. Bull. 2022, 8, 146–151. [Google Scholar]

- Fahmy, A.F.M.; El-Sayed, A.A.; Hemdan, M.M. Multicomponent Synthesis of 4-Arylidene-2-Phenyl-5(4H)-Oxazolones (Azlactones) Using a Mechanochemical Approach. BMC Chem. 2016, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, N.; Daub, C.D.; Åstrand, P.-O.; Unge, M. Local Field Factors and Dielectric Properties of Liquid Benzene. J. Phys. Chem. B 2023, 127, 11839–11845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Jiang, B. Learning Dipole Moments and Polarizabilities. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligorio, R.F.; Rodrigues, J.L.; Zuev, A.; Dos Santos, L.H.R.; Krawczuk, A. Benchmark of a Functional-Group Database for Distributed Polarizability and Dipole Moment in Biomolecules. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 29495–29504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędrzejewska, B.; Krawczyk, P.; Józefowicz, M. Experimental and Theoretical Studies of the Influence of Solvent Polarity on the Spectral Properties of Two Push-Pull Oxazol-5-(4H)-one Compounds. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2017, 171, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, L.X.; Flores, B.M.M.; Pérez, V.M.J. Microwave Assisted Organic Syntheses (MAOS): The Green Synthetic Method. Res. Gate 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Suresha, S.; Shilpa, G.M.; Vijayalakshmi, A.R.; et al. Photophysical Studies on Quinoline-Substituted Oxazole Analogues for Optoelectronic Application: An Experimental and DFT Approach. J. Electron. Mater. 2025, 78, 11993–12005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannopantar, S.R.; Patil, V.S.; Prabhala, P.; et al. Systematic Photophysical Interaction Studies Between Newly Synthesised Oxazole Derivatives and Silver Nanoparticles: Experimental and DFT Approach. J. Fluoresc. 2024, 34, 1655–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, M.; Takagi, Y.; Hioki, K.; Nagasaka, T.; Sotome, H.; Ito, S.; Miyasaka, H.; Irie, M. A Turn-on Mode Fluorescent Diarylethene: Solvatochromism of Fluorescence. Dyes Pigm. 2018, 153, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homocianu, M.; Airinei, A.; Matica, O.T.; Cristea, M.; Ungureanu, E.M. Solvent Effects and Metal Ion Recognition in Several Azulenyl-Vinyl-Oxazolones. Symmetry 2023, 15, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J. Localized Electronic Excitations in π-Conjugated Systems: Spectroscopic and Computational Insights. J. Phys. Chem. A 2023, 127, 3320–3335. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, T.; Schmidt, R.; Chen, L. Steric and Electronic Balancing in Methoxy-Substituted Fluorophores: A Molecular Dynamics Study. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 8255–8268. [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt, C.; Welton, T. Solvents and Solvent Effects in Organic Chemistry, 4th ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kupriyanov, G.A.; Isaev, I.V.; Plastinin, I.V.; Dolenko, T.A.; Dolenko, S.A. Decomposition of Spectral Band into Gaussian Contours Using an Improved Modification of the Gender Genetic Algorithm. Moscow Univ. Phys. Bull. 2024, 78, S236–S242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.; Mannaerts, C.M.; Lievens, C. Assessment of UV-VIS Spectra Analysis Methods for Quantifying the Absorption Properties of Chromophoric Dissolved Organic Matter (CDOM). Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Comparative Study of Semi-Empirical Methods (AM1, PM3, PM6, PM7) for Predicting Electronic Spectra of Conjugated Systems. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1205, 127591. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Solvent-Dependent Spectral Shifts in 5(4H)-Oxazolones: Experimental and Theoretical Insights. J. Phys. Chem. A 2021, 125, 2542–2551. [Google Scholar]

|

Substituent, X |

Overall formula | Molecular weight | Melting point | The color intensity | Reaction yield | Solvent |

| -H | C16H11NO2 | 249 | 165 | Bright yellow | 54 | Ethanol |

| -OCH3 | C17H13NO3 | 279 | 155 | Bright yellow | 80 | Ethanol |

| Parameters | unsubstituted | substitute methoxy |

|---|---|---|

| µ(Debye) Dipole moment of the ground state | 2.807 | 3.039 |

| µ*(Debye) Dipole moment of the excited State | 3.014 | 3.022 |

| Solvent | ethyl acetate | acetic acid | acetonitrile | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | unsubstituted | methoxy-substituted | unsubstituted | methoxy-substituted | unsubstituted | methoxy-substituted |

| ℷa⨯10-7 | 405 | 457 | 410 | 457 | 415 | 461 |

| ℷf⨯10-7 | 435 | 500 | 441 | 489 | 480 | 496 |

| va-vf | 1703 | 1882 | 1715 | 1432 | 3263 | 1531 |

| (va +vf)/2 | 23840 | 20940 | 23530 | 21170 | 22460 | 20930 |

| F2(D, n) | 0.095 | 0.115 | 0.104 | 0.124 | 0.562 | 0.578 |

| F3(D, n) | 0.773 | 0.761 | 0.777 | 0.766 | 1.006 | 0.993 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).