1. Sindbis Virus: From Discovery to Molecular Pathogenesis

Sindbis virus (SINV), first isolated in 1952 from

Culex univittatus mosquitoes near Sindbis, Egypt, represents the prototype species of the Alphavirus genus within the family

Togaviridae [

1]. Following its initial discovery, the first recognized human cases emerged in Uganda (1961), South Africa (1963), and Australia (1967), establishing SINV as a globally distributed arbovirus causing febrile rash and debilitating arthritis [

1]. As the prototype al-phavirus, SINV has served as the foundational model for elucidating alphavirus replication strategies, structural protein synthesis, and virion assembly mechanisms [

2].

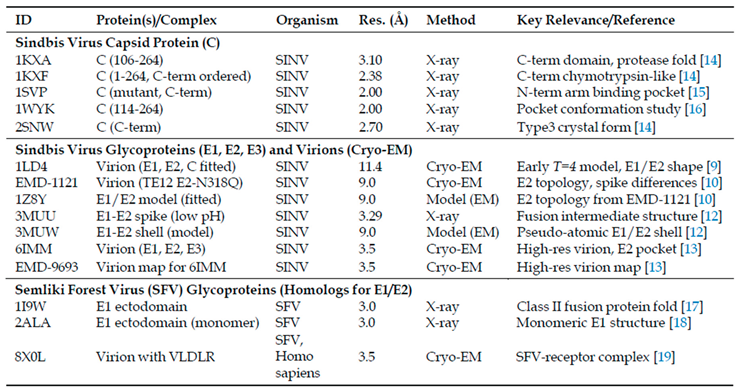

Phylogenetically, SINV belongs to the Western Equine Encephalitis (WEE) serocomplex and shares evolutionary relationships with Chikungunya virus and other arthritogenic alphaviruses [

1,

3,

4,

5]. As illustrated in

Figure 1A, SINV clusters among Old World alphaviruses within the broader phylogenetic landscape of medically relevant species. The virus exhibits considerable genetic diversity, with at least six distinct genotypes (SINV-I to SINV-VI) displaying up to 22.2% amino acid divergence in the E2 glycoprotein [

6]. These genotypes show distinct geographical clustering: SINV-I encompasses European and African strains associated with human disease outbreaks, SINV-II and SINV-III include Australian and East Asian isolates with 12-15% E2 divergence from SINV-I, SINV-IV comprises Azerbaijan and Chinese strains, SINV-V represents New Zealand isolates, and the recently proposed SINV-VI includes African-European variants [

6,

7,

8]. The pairwise identity analysis shown in

Figure 1C demonstrates the relative conservation of capsid proteins compared to overall genomic sequences across the alphavirus genus.

The SINV genome comprises approximately 11.7 kilobases of positive-sense, singlestranded RNA organized into two principal open reading frames, as depicted in

Figure 1B [

2]. The structural proteins—Capsid (C), E3, E2, 6K, and E1—are translated from a 26S subgenomic RNA and undergo precisely regulated proteolytic processing initiated by the capsid protein’s serine protease activity [

9]. Mature virions exhibit

T=4 icosahedral quasisymmetry with 240 copies each of C, E1, and E2 proteins forming distinct nucleocapsid and glycoprotein shells [

9].

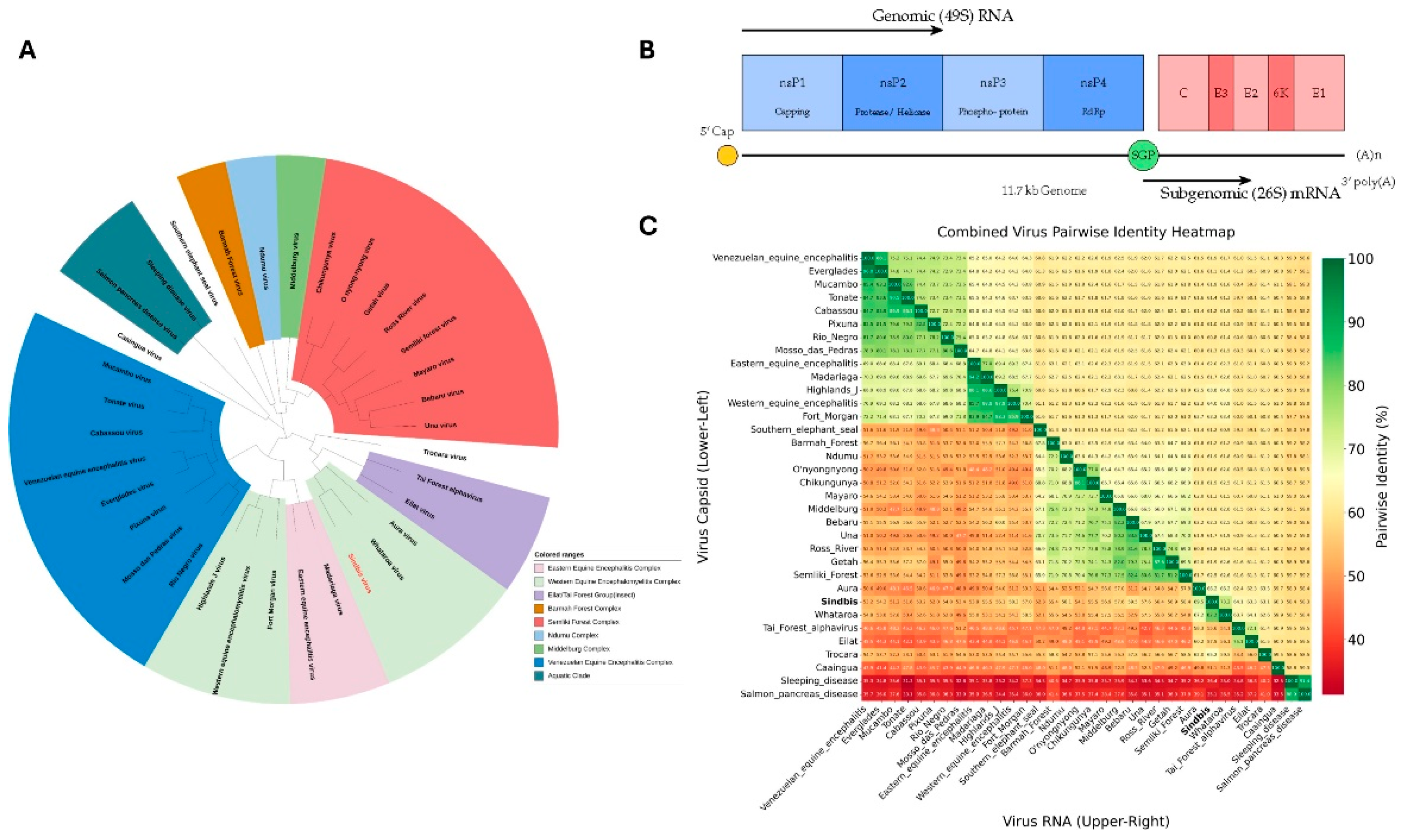

Structural understanding has evolved dramatically from early transmission electron microscopy to high-resolution techniques detailed in

Table 1. Landmark achievements include early cryo-electron microscopy reconstructions [

9], progressive resolution improvements to 9 Å and 7 Å [

10,

11], crystal structures of the E1-E2 spike complex [

12], and the recent 3.5 Å cryo-EM structure providing near-atomic detail [

13]. These structural advances, combined with capsid protein crystallography [

14], have revealed the molecular architecture underlying viral function.

Genotypic variations profoundly impact viral function and pathogenesis. E2 protein differences between strains directly influence mosquito infectivity, with specific motifs at positions 95-96 and 116-119 enhancing

Aedes aegypti infection efficiency [

20]. Mutations in untranslated regions affect host-specific replication and necessitate adaptive changes in structural proteins [

21,

22]. Specific E2 substitutions can confer heparan sulfate-dependent infection capabilities and alter neuroinvasiveness in animal models [

23,

24].

Clinically, SINV infection manifests as Pogosta disease, Ockelbo disease, or Karelian fever, characterized by maculopapular rash, arthralgia affecting wrists, hips, knees, and ankles, and potential progression to chronic arthritis lasting months to years [

1]. The structural proteins mediate pathogenic processes through tissue tropism determination, with E2 receptor-binding domains directing cellular specificity and viral replication in periosteum, tendons, and muscle tissues [

25,

26]. Immune evasion mechanisms include capsid-mediated interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1(IRAK1) inhibition, E1/E2 glycan shielding, and E2 epitope drift under antibody pressure [

27,

28,

29]. This integrated understanding of SINV structure, diversity, and pathogenesis provides the foundation for rational therapeutic development and represents a paradigm for comprehending alphavirus biology and designing targeted interventions against these important human pathogens.

2. Sindbis Virus Architecture and Structural Protein Organization

Sindbis virus virions are spherical, enveloped particles with a diameter of approximately 68 to 70 nm, exhibiting the characteristic

T=4 icosahedral quasisymmetry that defines alphavirus architecture [

3,

9]. This sophisticated structural organization dictates that 240 copies each of the capsid (C) protein, E1 glycoprotein, and E2 glycoprotein are incorporated into each virion, with E1 and E2 heterodimerizing to form 80 trimeric spikes that protrude from the virion surface [

9]. The maintenance of this precise symmetry across two structurally distinct protein layers—the outer glycoprotein shell and the inner nucleocapsid core—requires highly orchestrated interactions established primarily through the specific binding between the E2 cytoplasmic domain and a hydrophobic pocket on the capsid protein surface [

9].

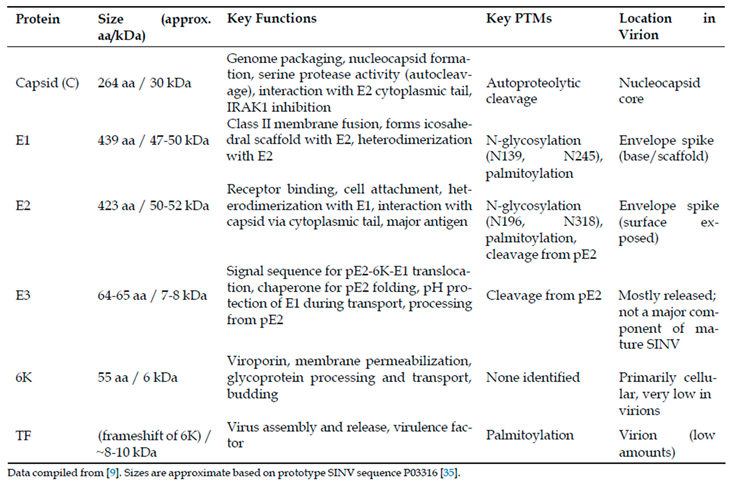

The SINV virion comprises a multi-layered architecture with two nested icosahedral protein shells separated by a host-derived lipid membrane, as illustrated in

Figure 2. The innermost nucleocapsid core consists of genomic RNA tightly packaged by 240 capsid proteins, surrounded by the viral envelope containing embedded E1 and E2 glycoproteins forming the surface spikes [

9,

30]. The host-derived nature of this lipid envelope significantly influences virion properties, with differences in lipid composition between mammalian and insect cell-derived virions affecting membrane fluidity and potentially modulating glycoprotein spike conformation and infectivity [

31,

32].

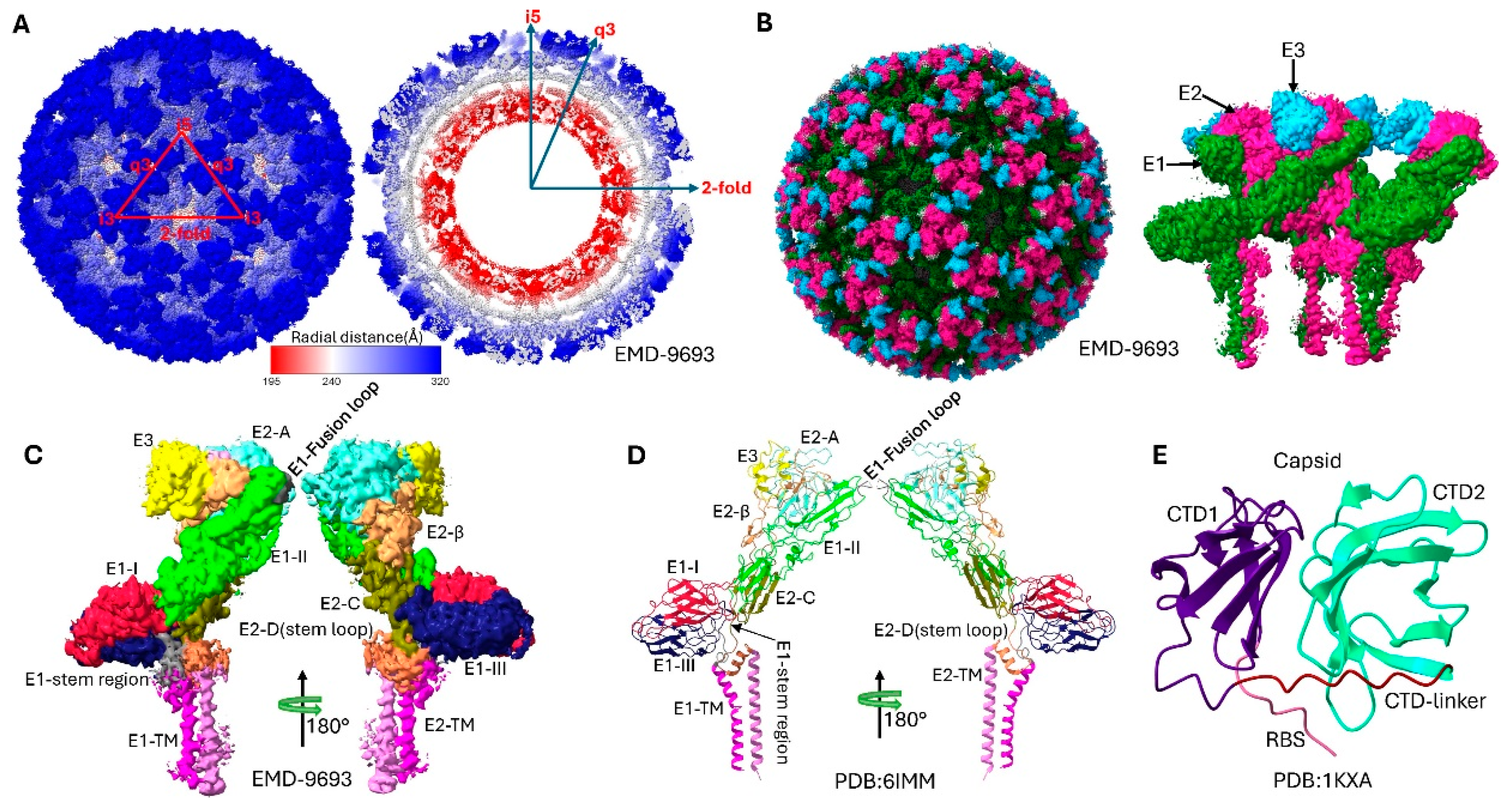

The structural proteins encoded by the 26S subgenomic mRNA undergo precise proteolytic processing to yield functionally distinct components with complementary roles in viral assembly, entry, and pathogenesis, as summarized in

Table 2. The capsid protein (264 amino acids, 30 kDa) exhibits a bipartite structure comprising an intrinsically disordered N-terminal RNA-binding domain (residues 1-113) rich in basic amino acids and a well-structured C-terminal domain (residues 114-264) adopting a chymotrypsin-like serine protease fold [

9,

14]. This dual architecture enables the capsid protein to perform multiple critical functions: serine protease activity mediating autocatalytic cleavage at the conserved Trp-Ser junction through a classical catalytic triad involving Ser215, specific recognition and binding of the genomic RNA packaging signal within the nsP1 coding region with nanomolar affinity, and nucleocapsid core assembly through oligomerization motifs [

14,

33,

34].

The E1 glycoprotein (439 amino acids, 47-50 kDa) functions as the class II viral fusion protein responsible for mediating pH-dependent membrane fusion during endosomal entry [

9,

17]. Its ectodomain exhibits the characteristic three-domain organization of class II fusion proteins: a central Domain I, an elongated Domain II containing the conserved fusion loop at its distal tip, and an immunoglobulin-like Domain III connecting to the transmembrane anchor [

9]. E1 molecules arrange tangentially to the viral surface, forming an icosahedral scaffold underneath the E2 glycoproteins, and undergo dramatic conformational changes upon low pH exposure, dissociating from E2, inserting the fusion loop into target membranes, and trimerizing into stable rod-like structures that drive membrane fusion through hairpin-like refolding [

9,

12].

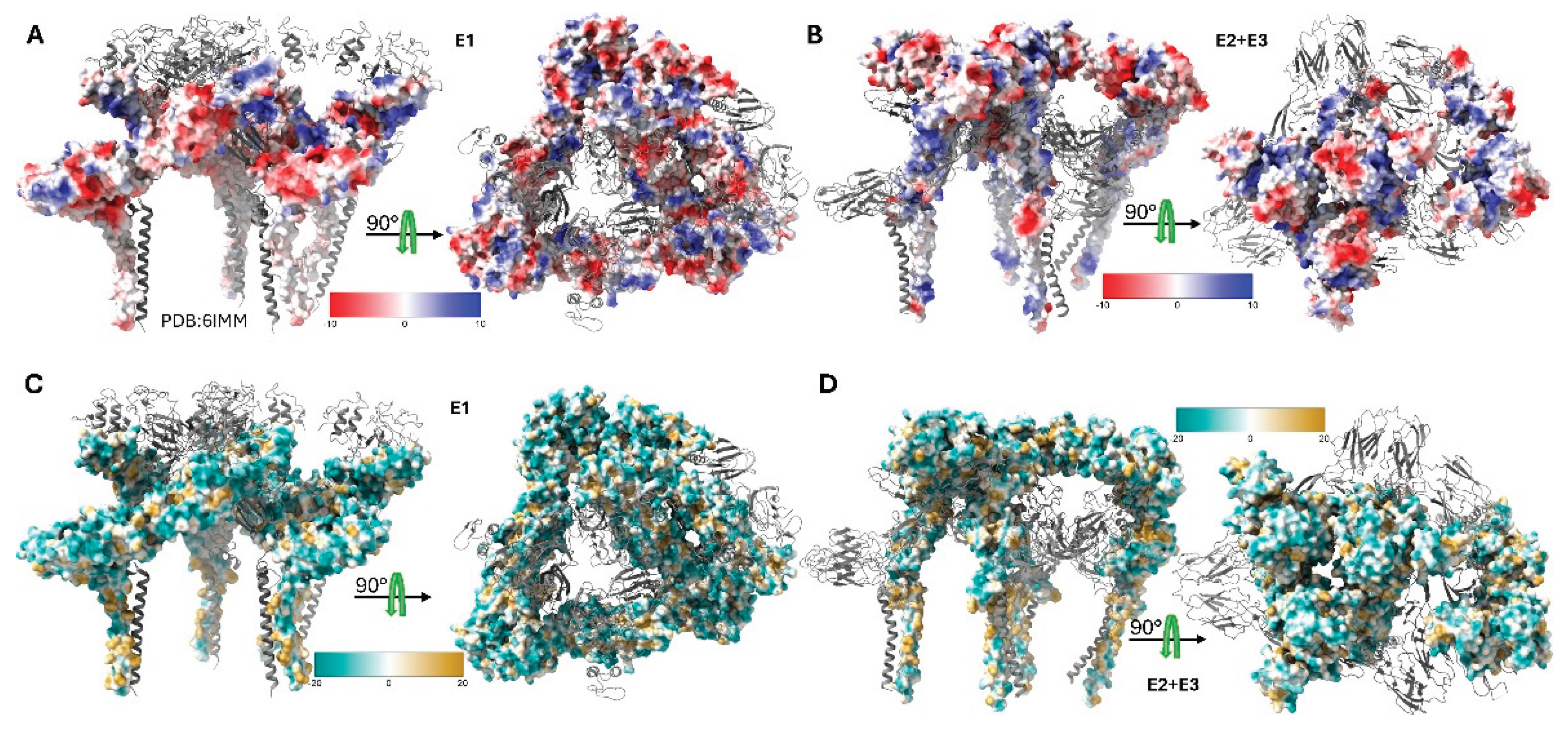

The E2 glycoprotein (423 amino acids, 50-52 kDa) serves as the primary determinant of cellular tropism and the principal target for neutralizing antibodies [

36,

37]. As demonstrated in

Figure 3, the E2 ectodomain exhibits distinct electrostatic and lipophilic properties across its functional domains A, B(missing in this map), C, and D, with domain A containing key receptor-binding determinants, domain B forming the spike apex and housing neutralizing epitopes, and domain C mediating extensive E1 interactions [

13,

19]. E2 recognizes multiple host cell attachment factors including heparan sulfate through posi tively charged residues and specific entry receptors such as natural resistance-associated macrophage protein(NRAMP) proteins, with the region spanning amino acids 170-220 serving as a critical receptor-binding domain [

23,

38,

39].

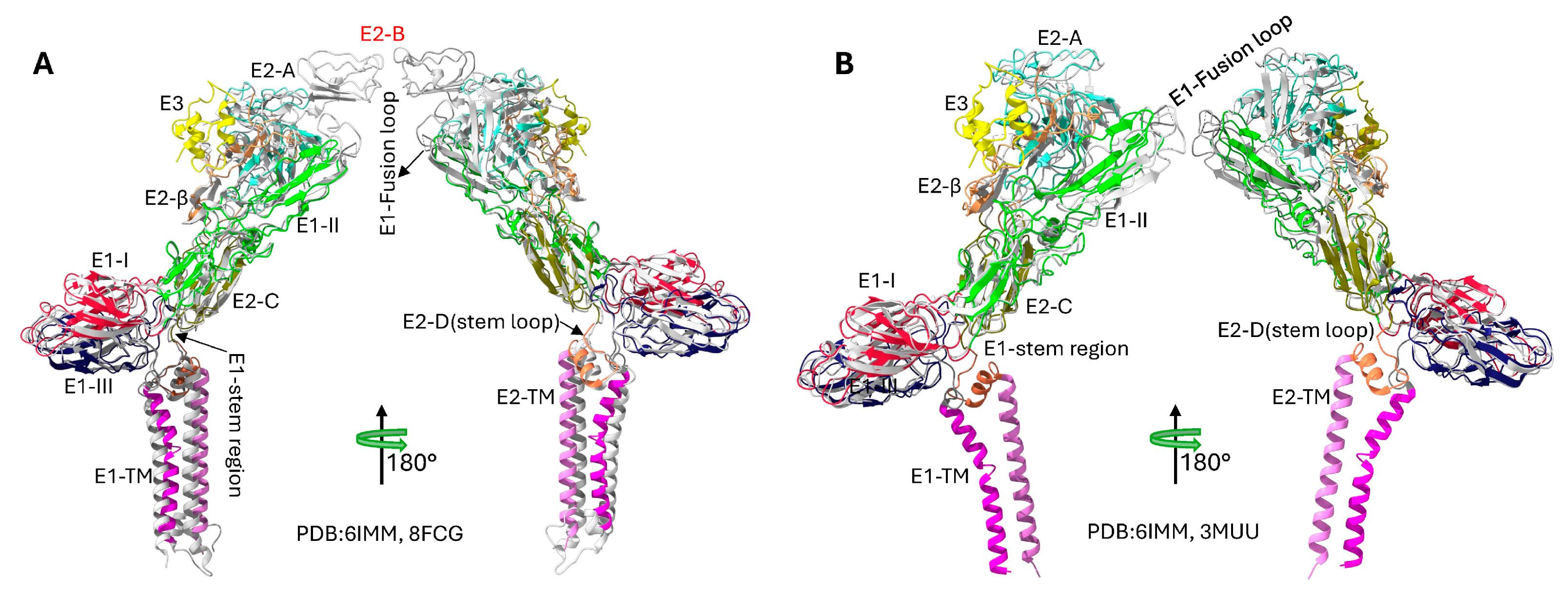

Structural comparisons reveal important architectural features and dynamic properties of SINV envelope proteins, as shown in

Figure 4. The absence of well-ordered E2 domain B density in SINV contrasts with other alphaviruses like Chikungunya virus[

40], potentially reflecting structural flexibility important for receptor binding and fusion regulation [

13]. pH-induced conformational changes between physiological (up to pH 8.0) and fusion-triggering conditions (pH 5.6) demonstrate the dramatic structural rearrangements occurring during viral entry, particularly the disordering of E2 domain B and exposure of the E1 fusion loop [

12].

E1 and E2 glycoproteins contain conserved N-linked glycosylation sites that critically influence viral function and immune evasion. E1 possesses glycans at Asn139 and Asn245, with differential accessibility leading to complex-type processing at N139 and high-mannose retention at N245, both essential for proper folding, transport, and virulence in vertebrate and invertebrate hosts [

28]. E2 glycosylation occurs at Asn196 and Asn318, with these modifications contributing to immune evasion through glycan shielding while paradoxically enhancing heparan sulfate binding and virulence when eliminated [

28,

41]. The E3 protein (64-65 amino acids, 7-8 kDa) functions as both a signal sequence directing pE2-6K-E1 translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum and a chaperone facilitating proper spike assembly and pH protection during transport [

42,

43]. Following furin-mediated cleavage from E2 in the trans-Golgi network, E3 is largely released from SINV virions, contrasting with its retention in other alphaviruses and enabling proper spike maturation essential for infectivity [

42,

43].

The small membrane proteins 6K and TF arise from overlapping genetic sequences through ribosomal frameshifting, with 6K (55 amino acids, 6 kDa) functioning as a viroporin that modulates cellular calcium homeostasis and membrane permeability to facilitate glycoprotein processing and budding [

30,

44]. In contrast, TF incorporates into virions at low levels and undergoes palmitoylation of N-terminal cysteine residues, directing its plasma membrane localization and distinguishing its fate from the largely excluded 6K protein [

30,

45].

Critical protein-protein interactions orchestrate virion assembly and function. The capsid protein’s hydrophobic pocket accommodates both intra-capsid N-terminal arm interactions during nucleocapsid assembly and E2 cytoplasmic tail binding through a conserved Tyr-X-Leu motif during budding, with residues Tyr180 and Trp247 mediating these specific interactions [

2,

14]. The E1-E2 heterodimer formation in the endoplasmic reticulum is essential for proper folding and transport, with E2 acting as a pH-sensitive regulator that prevents premature E1 activation until appropriate endosomal conditions trigger fusion cascade initiation [

9,

27].

Beyond structural roles, SINV proteins exhibit sophisticated immune modulation capabilities. The capsid protein inhibits IRAK1 signaling pathways upon cytoplasmic delivery, creating a permissive environment for infection establishment [

27]. E2 serves as the primary antigenic target with neutralizing epitopes concentrated in the receptorbinding domain, driving evolutionary pressure for epitope drift that facilitates immune evasion while maintaining receptor recognition capability [

6,

29].

The quasisymmetric architecture creates subtle conformational heterogeneity among chemically identical protein subunits, particularly affecting E2 molecules at different icosahedral positions, which may influence receptor binding avidity and spike cooperativity during membrane fusion [

13]. This sophisticated structural organization, combining precise symmetry with functional flexibility, exemplifies the evolutionary optimization of alphavirus architecture for effective host cell recognition, entry, and immune evasion across diverse biological environments.

3. Future Perspectives: Integrating Structural Knowledge for Therapeutic Advancement

The structural proteins of Sindbis virus—Capsid, E1, E2, E3, and 6K/TF—represent a remarkable example of molecular evolution, where 240 copies each of C, E1, and E2 are meticulously arranged with

T=4 icosahedral quasisymmetry to create a sophisticated macromolecular machine [

9]. Decades of research employing progressively advanced biochemical, genetic, and structural biology techniques have illuminated the intricate roles these proteins play throughout the viral life cycle, from genome packaging and virion assembly to host cell interaction, entry, and immune modulation. The capsid protein serves dual functions as both a serine protease and RNA-binding scaffold while facilitating budding through interaction with the E2 cytoplasmic tail and providing early immune evasion through IRAK1 inhibition [

27]. The E1 glycoprotein operates as a tightly regulated class II fusion protein whose activity is modulated by pH and E2 interaction, while E2 serves as the primary determinant of host cell recognition and a major antigenic target [

9]. The auxiliary proteins E3 and 6K/TF contribute essential functions in glycoprotein processing, transport, spike maturation, and membrane permeabilization [

30].

The structural variations observed across different SINV genotypes and strains, particularly within the E2 glycoprotein, fundamentally underpin the virus’s global distribution, host adaptation strategies, and diverse pathogenic manifestations ranging from asymptomatic infection to debilitating chronic arthralgia [

10]. These structural features, including receptor binding domains and glycosylation patterns, dictate tissue tropism and disease progression while positioning these proteins at the forefront of immune system interactions through mechanisms such as glycan shielding and epitope drift.

Despite remarkable progress, particularly the achievement of near-atomic resolution structures of intact SINV virions, significant knowledge gaps persist that limit our comprehensive understanding of alphavirus biology. The absence of high-resolution structural information for several critical components remains a fundamental challenge. While the 3.5 Å cryo-EM structure of the intact virion provides unprecedented detail [

13], atomicresolution structures of full-length E2 glycoprotein, including its transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains in native spike conformation, remain elusive. The dynamic conformational landscape of the E1/E2 spike complex during receptor binding, pH-triggered activation, and membrane fusion represents another critical gap, as current static structures provide only snapshots of what is inherently a dynamic process. The structural organization of small membrane proteins 6K and TF, their oligomerization mechanisms, and precise interactions with viral and host proteins are largely unknown at the atomic level, complicated by their small size and membrane association. Furthermore, while the capsid protein arrangement is well-characterized, the precise organization of genomic RNA within the nucleocapsid core and specific RNA-protein interactions beyond the primary packaging signal require higher-resolution definition.

The molecular mechanisms underlying SINV pathogenesis present another frontier requiring intensive investigation. The precise molecular basis by which structural proteins contribute to chronic arthralgia remains incompletely understood [

3], necessitating identification of specific E2 epitopes or E1/E2 conformations that interact with joint tissue cells and trigger persistent inflammation. The comprehensive mapping of interactions between SINV structural proteins and host factors in both vertebrate and invertebrate systems continues to develop, with recent discoveries such as the role of sorting nexin 5 (SNX5) in alphavirus replication highlighting the importance of host-directed research [

46]. The unexpected detection of non-structural protein nsP2 within purified SINV virions from multiple host cell types opens entirely new research avenues regarding potential early infection functions [

46]. Additionally, the structural determinants governing efficient infection and transmission by different mosquito vector species across all SINV genotypes require further elucidation to predict and control disease outbreaks effectively.

The therapeutic landscape for alphavirus diseases remains notably deficient, with no clinically approved antiviral therapies or vaccines specifically targeting Sindbis virus or most arthritogenic alphaviruses [

47]. However, the wealth of structural information now available presents unprecedented opportunities for rational therapeutic development. Entry inhibitors targeting E2 glycoprotein receptor binding or E1-mediated fusion mechanisms represent promising antiviral strategies, with the recently identified hydrophobic pocket in E2 serving as a potential novel target [

13]. Assembly and budding inhibitors that disrupt critical interactions between capsid proteins and E2 cytoplasmic tails, or interfere with capsid oligomerization and RNA packaging, offer additional therapeutic avenues [

10].

Vaccine development strategies leveraging structural protein knowledge encompass multiple promising approaches. Subunit vaccines utilizing recombinant E1 and E2 proteins or specific domains thereof capitalize on E2’s role as the primary target for neutralizing antibodies [

48]. Virus-like particles formed by expression of SINV structural proteins provide non-infectious platforms displaying native glycoprotein spikes as potent immunogens. SINV replicons are increasingly explored as vaccine vectors for expressing antigens from diverse pathogens, including SARS-CoV-2 and Dengue virus [

49], while chimeric SINV-based vaccines incorporating insect-specific alphavirus backbones like Eilat virus offer enhanced safety profiles [

50]. The identification of conserved epitopes across multiple arthritogenic alphaviruses, particularly within domain B of E2, represents a critical goal for developing broadly protective antibodies and pan-alphavirus vaccines [

51].

Future research directions will likely emphasize higher-resolution dynamics through advanced structural biology techniques such as time-resolved cryo-electron microscopy and single-molecule FRET to capture conformational transitions during cell entry. In situ structural biology approaches, including cryo-electron tomography and correlative light and electron microscopy, will enable visualization of viral protein interactions and assembly processes directly within infected cells. Systems virology methodologies integrating structural data with proteomics, transcriptomics, and functional genomics will build comprehensive understanding of SINV-host interactions mediated by structural proteins. Structure-guided antiviral and vaccine design will increasingly leverage growing structural databases to rationally engineer novel inhibitors and improved immunogens capable of eliciting broad, durable protective immunity.

The continued development of SINV-based therapeutic platforms, including gene therapy vectors, oncolytic virotherapy applications [

52], and vaccine delivery systems, will benefit substantially from deeper understanding of structural protein functions. Comparative structural pathogenesis studies examining high-resolution structures of different SINV genotypes and strains with varying pathogenic profiles will identify critical structural correlates of virulence and tissue tropism, informing both basic virology and clinical applications.

The foundational research on SINV structural proteins established over decades of investigation continues to provide essential insights into alphavirus biology while serving as a paradigm for understanding related pathogens. As we advance toward more sophisticated therapeutic interventions, the integration of structural knowledge with emerging technologies and interdisciplinary approaches will be paramount for addressing the ongoing global health threat posed by Sindbis virus and related pathogenic alphaviruses. The remarkable architectural precision of the SINV virion, combined with our evolving understanding of its functional complexities, positions this system as both a model for fundamental virology research and a platform for innovative therapeutic development in the continuing effort to combat arboviral diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.G., C.K.N. and W.Z.; methodology, Q.G.; software, Q.G.; validation, Q.G., C.K.N. and W.Z.; formal analysis, Q.G.; investigation, Q.G.; resources, Q.G., C.K.N. and W.Z.; data curation, Q.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.G.; writing—review and editing, Q.G., C.K.N. and W.Z.; visualization, Q.G.; supervision, C.K.N. and W.Z.; project administration, W.Z.; funding acquisition, C.K.N. and W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

(A) Phylogenetic relationship of Sindbis virus within the Alphavirus genus. The unrooted maximum likelihood tree, based on whole-genome alignments, positions Sindbis virus (highlighted in red) among other medically relevant alphaviruses. The tree was generated using the RaxML algorithm with a GTR model within the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC). Numbers at the nodes represent bootstrap support values, indicating the statistical confidence for each branching point. (B) Schematic of the Sindbis virus (SINV) genome organization. The positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome of approximately 11.7 kb contains two main open reading frames (ORFs). The 5’-proximal ORF is translated from the genomic RNA (49S) to produce the non-structural polyprotein (nsP1-nsP4). The 3’-proximal ORF is translated from a 26S subgenomic RNA (sgRNA), transcribed from the subgenomic promoter (SGP), to produce the structural polyprotein (C, E3, E2, 6K, and E1). (C) Pairwise Identity Heatmap. A heatmap displaying the percent identity between various alphaviruses. The lower-left triangle compares the amino acid sequences of the capsid proteins, while the upper-right triangle compares the nucleotide sequences of the full-length RNA genomes. The color scale indicates the percentage of identity, from low (red, ∼30%) to high (green, 100%), highlighting the relative conservation of the capsid protein compared to the overall genomic sequence across the genus.

Figure 1.

(A) Phylogenetic relationship of Sindbis virus within the Alphavirus genus. The unrooted maximum likelihood tree, based on whole-genome alignments, positions Sindbis virus (highlighted in red) among other medically relevant alphaviruses. The tree was generated using the RaxML algorithm with a GTR model within the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC). Numbers at the nodes represent bootstrap support values, indicating the statistical confidence for each branching point. (B) Schematic of the Sindbis virus (SINV) genome organization. The positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome of approximately 11.7 kb contains two main open reading frames (ORFs). The 5’-proximal ORF is translated from the genomic RNA (49S) to produce the non-structural polyprotein (nsP1-nsP4). The 3’-proximal ORF is translated from a 26S subgenomic RNA (sgRNA), transcribed from the subgenomic promoter (SGP), to produce the structural polyprotein (C, E3, E2, 6K, and E1). (C) Pairwise Identity Heatmap. A heatmap displaying the percent identity between various alphaviruses. The lower-left triangle compares the amino acid sequences of the capsid proteins, while the upper-right triangle compares the nucleotide sequences of the full-length RNA genomes. The color scale indicates the percentage of identity, from low (red, ∼30%) to high (green, 100%), highlighting the relative conservation of the capsid protein compared to the overall genomic sequence across the genus.

Figure 2.

Structural organization and domain architecture of Sindbis virus revealed by cryo-electron microscopy. (A) Radial distance coloring of the SINV virion, showing the layered architecture from the nucleocapsid core (inner, red) to the glycoprotein spikes (outer, blue). The color gradient represents increasing distance from the viral center. (B) Domain-based coloring of the complete SINV particle, highlighting the distinct glycoprotein shells: E3 (blue), E2 (magenta), and E1 (green). (C) Detailed subdomain organization of the E1 and E2 glycoproteins in the cryo-EM density map (EMD-9693), showing the three-dimensional arrangement of functional domains within the spike complex. Domain I (DI), Domain II (DII), Domain III (DIII), and transmembrane domain(TM) of E1 are color-coded, along with domains A, B(missing in this map), C, D and TM of E2. (D) Atomic model representation of the E1/E2 glycoprotein heterodimer (PDB 6IMM) with subdomain coloring corresponding to the cryo-EM density. The model shows the detailed molecular architecture of the spike proteins including transmembrane regions and their configurations. (E) Structural model of the capsid protein core (derived from PDB 1KXA). The C-terminal protease domain (structured) and N-terminal RNA-binding domain (flexible) are distinguished by coloring.

Figure 2.

Structural organization and domain architecture of Sindbis virus revealed by cryo-electron microscopy. (A) Radial distance coloring of the SINV virion, showing the layered architecture from the nucleocapsid core (inner, red) to the glycoprotein spikes (outer, blue). The color gradient represents increasing distance from the viral center. (B) Domain-based coloring of the complete SINV particle, highlighting the distinct glycoprotein shells: E3 (blue), E2 (magenta), and E1 (green). (C) Detailed subdomain organization of the E1 and E2 glycoproteins in the cryo-EM density map (EMD-9693), showing the three-dimensional arrangement of functional domains within the spike complex. Domain I (DI), Domain II (DII), Domain III (DIII), and transmembrane domain(TM) of E1 are color-coded, along with domains A, B(missing in this map), C, D and TM of E2. (D) Atomic model representation of the E1/E2 glycoprotein heterodimer (PDB 6IMM) with subdomain coloring corresponding to the cryo-EM density. The model shows the detailed molecular architecture of the spike proteins including transmembrane regions and their configurations. (E) Structural model of the capsid protein core (derived from PDB 1KXA). The C-terminal protease domain (structured) and N-terminal RNA-binding domain (flexible) are distinguished by coloring.

Figure 3.

Electrostatic and lipophilic properties of Sindbis virus envelope glycoproteins. Surface representations of the SINV structural proteins derived from the high-resolution cryo-EM structure (PDB 6IMM) showing distinct physicochemical properties. (A) Coulombic electrostatic potential (ESP) map of the E1 glycoprotein, colored from red (negative potential, −10 kcal/mol·e) through white (neutral) to blue (positive potential, +10 kcal/mol·e). The ESP calculation used a distance-dependent dielectric (ε = 4d) with an offset of 1.4 Å from the molecular surface. (B) Coulombic electrostatic potential map of the E2 and E3 glycoproteins showing the charge distribution across the receptor-binding and fusion-regulation domains. The same color scale and computational parameters as panel A were applied. (C) Molecular lipophilicity potential (MLP) map of the E1 glycoprotein, colored from dark cyan (hydrophilic, −20) through white (neutral) to dark goldenrod (lipophilic, +20). The MLP was calculated using the Fauchere method (e−d) with a 5.0 Å distance cutoff. (D) Molecular lipophilicity potential map of the E2 and E3 glycoproteins revealing hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions important for membrane interactions and protein folding.

Figure 3.

Electrostatic and lipophilic properties of Sindbis virus envelope glycoproteins. Surface representations of the SINV structural proteins derived from the high-resolution cryo-EM structure (PDB 6IMM) showing distinct physicochemical properties. (A) Coulombic electrostatic potential (ESP) map of the E1 glycoprotein, colored from red (negative potential, −10 kcal/mol·e) through white (neutral) to blue (positive potential, +10 kcal/mol·e). The ESP calculation used a distance-dependent dielectric (ε = 4d) with an offset of 1.4 Å from the molecular surface. (B) Coulombic electrostatic potential map of the E2 and E3 glycoproteins showing the charge distribution across the receptor-binding and fusion-regulation domains. The same color scale and computational parameters as panel A were applied. (C) Molecular lipophilicity potential (MLP) map of the E1 glycoprotein, colored from dark cyan (hydrophilic, −20) through white (neutral) to dark goldenrod (lipophilic, +20). The MLP was calculated using the Fauchere method (e−d) with a 5.0 Å distance cutoff. (D) Molecular lipophilicity potential map of the E2 and E3 glycoproteins revealing hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions important for membrane interactions and protein folding.

Figure 4.

Structural comparisons of Sindbis virus envelope glycoproteins revealing missing domain B and pH-induced conformational changes. (

A) Comparative analysis of SINV and CHIKV E1/E2 glycoprotein structures highlighting the missing E2 domain B in SINV. The SINV structure (PDB 6IMM) is shown with domain-based coloring consistent with

Figure 2, while the CHIKV structure (PDB 8FCG)[

40] is displayed in grey. The superposition reveals that SINV lacks the well-ordered E2 domain B structure present in CHIKV, which normally caps the E1 fusion loop. Domain A, C, and D of E2 are clearly resolved in both structures, demonstrating the conserved overall architecture despite the missing domain B density in SINV. The RMSD between the structures is 1.178 Å. (

B) pH-dependent structural comparison of SINV envelope glycoproteins showing conformational changes during the fusion process. The physiological pH structure (PDB 6IMM, pH 8.0, colored) is compared with the low pH fusion intermediate structure (PDB 3MUU, pH 5.6, grey). At low pH, significant conformational rearrangements occur, particularly in the E2 domain organization and the

β-ribbon connector region. The low pH structure represents an early fusion intermediate where E2 domain B becomes disordered and detaches from the E1 fusion loop, exposing it for membrane insertion. The RMSD between structures is 1.005 Å, and a 68 degrees rotation reflecting the conformational changes that occur below the fusion threshold (pH 6.0). These structural transitions are critical for alphavirus membrane fusion and viral entry into host cells.

Figure 4.

Structural comparisons of Sindbis virus envelope glycoproteins revealing missing domain B and pH-induced conformational changes. (

A) Comparative analysis of SINV and CHIKV E1/E2 glycoprotein structures highlighting the missing E2 domain B in SINV. The SINV structure (PDB 6IMM) is shown with domain-based coloring consistent with

Figure 2, while the CHIKV structure (PDB 8FCG)[

40] is displayed in grey. The superposition reveals that SINV lacks the well-ordered E2 domain B structure present in CHIKV, which normally caps the E1 fusion loop. Domain A, C, and D of E2 are clearly resolved in both structures, demonstrating the conserved overall architecture despite the missing domain B density in SINV. The RMSD between the structures is 1.178 Å. (

B) pH-dependent structural comparison of SINV envelope glycoproteins showing conformational changes during the fusion process. The physiological pH structure (PDB 6IMM, pH 8.0, colored) is compared with the low pH fusion intermediate structure (PDB 3MUU, pH 5.6, grey). At low pH, significant conformational rearrangements occur, particularly in the E2 domain organization and the

β-ribbon connector region. The low pH structure represents an early fusion intermediate where E2 domain B becomes disordered and detaches from the E1 fusion loop, exposing it for membrane insertion. The RMSD between structures is 1.005 Å, and a 68 degrees rotation reflecting the conformational changes that occur below the fusion threshold (pH 6.0). These structural transitions are critical for alphavirus membrane fusion and viral entry into host cells.

Table 1.

Selected PDB and EMDB Structures of Sindbis Virus and Related Alphavirus Structural Proteins/Virions.

Table 1.

Selected PDB and EMDB Structures of Sindbis Virus and Related Alphavirus Structural Proteins/Virions.

Table 2.

Overview of Sindbis Virus Structural Proteins.

Table 2.

Overview of Sindbis Virus Structural Proteins.