1. Introduction

Neurotransmitters (NTs) like dopamine (DA), serotonin (SE) and epinephrine (EP) are essential for transmitting signals in the nervous system and play key roles in regulating mood, cognition, and physiological processes [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Among them, DA is the most studied due to its critical role in motor control, motivation, and cognitive functions. Imbalances in DA signaling in the brain are associated with neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s, schizophrenia, and depression [

1,

2,

7,

8]. The accurate detection of DA dynamics in the brain remains challenging due to its low concentration levels, complex release dynamics, and the limitations of traditional sensing methods. Aging further complicates this, as degeneration in the substantia nigra, the primary site of DA release in the brain, disrupts signaling and contributes to cognitive and motor decline, increasing susceptibility to neurodegenerative conditions [

1,

2,

3]. While new imaging technologies like near-infrared catecholamine nanosensors have improved real-time monitoring of DA, they produce complex data that require advanced analytical tools for accurate analysis. Artificial intelligence, especially machine learning (ML) and pattern recognition (PR), is increasingly used to automate the estimation of DA release, enhancing the performance of the traditional electrochemical sensors used to detect NTs [

1,

2,

3,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. ML and PR are used to address the challenges of analyzing complex, high-dimensional data, including data generated by voltammetric techniques. ML and PR algorithms have the capacity to identify patterns and relationships in large, multidimensional datasets, offering a powerful approach to deciphering the complexities of DA signaling [

1,

2,

3]. However, their use for simultaneously detecting and localizing DA release in aging brains remains underexplored.

1.1. Related Studies

Studies have applied classical machine learning [

1,

2,

3,

9] or deep learning [

15,

17,

18,

19] frameworks to either detect or quantify DA release in the brain. They all addressed these tasks separately and did not predict the ages of DA release sites corresponding to the ages of the species used for data collected in their studies.

Table 1 summarizes these studies and the performances of their proposed models.

1.2. Novelty

Our study introduces a novel ML framework that uses high-resolution nIRCat dataset to simultaneously detect and quantify age-dependent DA in acute mice brains. This approach has the potential to advance understanding of age-related dopamine changes and could aid in developing treatments for disorders like Parkinson’s and depression using deep brain stimulation therapies.

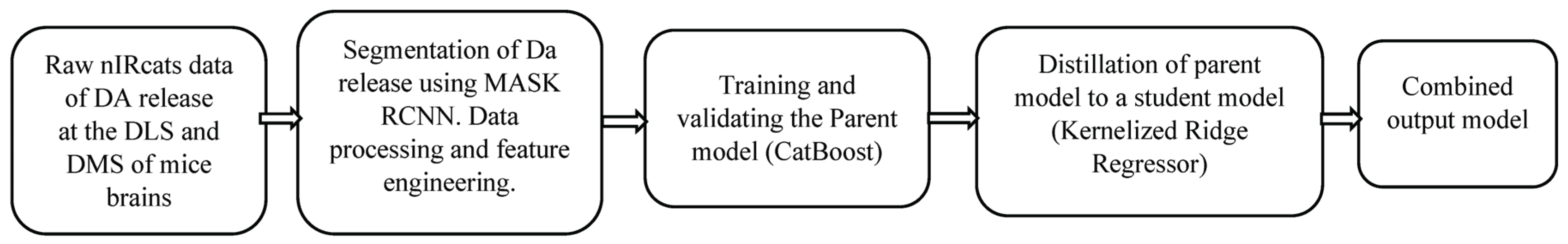

Figure 1 presents a flow diagram of this paper.

2. Materials

2.1. Equipment

4–12 weeks Male mice (BC6BA-Tg (HDexon1)62Gpb/3J) and female C57BL/6 mice from Jackson Labs were used for the study. Near-Infrared Catecholamine Nanosensors (nIRCat) manufactured as described in [

3] captured and labeled DA release dynamics, forming the experimental dataset. DA release was evoked in acute brain slices using tungsten bipolar stimulation electrodes (TBSE). Data processing and analysis were coded in Python, and the dataset was used to train and validate CatBoost and ridge regression models via GPU acceleration.

2.2. Data Collection

The mice were housed in cages under controlled conditions of twelve hours light/twelve hours dark cycles and regulated temperature. Our proposed ML framework aims to simultaneously predict DA release and the ages (4-12 weeks) of mice from two key brain regions, the DLS and DMS. 251 image frames were captured and labeled using the nIRCat system, as described elsewhere in [

3,

20]. These regions are the primary targets for DA release localization in this study. To induce DA release, electrical pulses with intensities of 0.1mA and 0.3 mA were generated by the TBSE and alternately applied to DMS and DLS in acute mouse brain slices. Alternating pulse strengths between these two brain regions enhanced dataset variability, mitigating model bias and overfitting. The 0.1–0.3 mA range was selected based on prior evidence demonstrating proportionate DA release in acute slices [

21]. Hence, the proposed model will predict stimulation intensities corresponding to DA release quantities. A summary of the frame proportions, pulse strengths, and stimulated brain regions is provided in

Table 2.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Processing

The initial step of the data processing was to detect and segment the DA release sites using MASK RCNN. These sites served as a baseline region of interest (ROI), computed by a moving average method. Each ROI was subtracted from the fluorescence trace to generate a time series of signal changes. Between the frames, the algorithm identified possible releases exceeding three standard deviations above the preset baseline noise and ROIs with such releases were marked significant, while inactive ROIs were excluded from further analysis. For each significant ROI, two exponential curves were fitted to determine onset and offset time constants. The features used to train the ML algorithm were then extracted from the ROI.

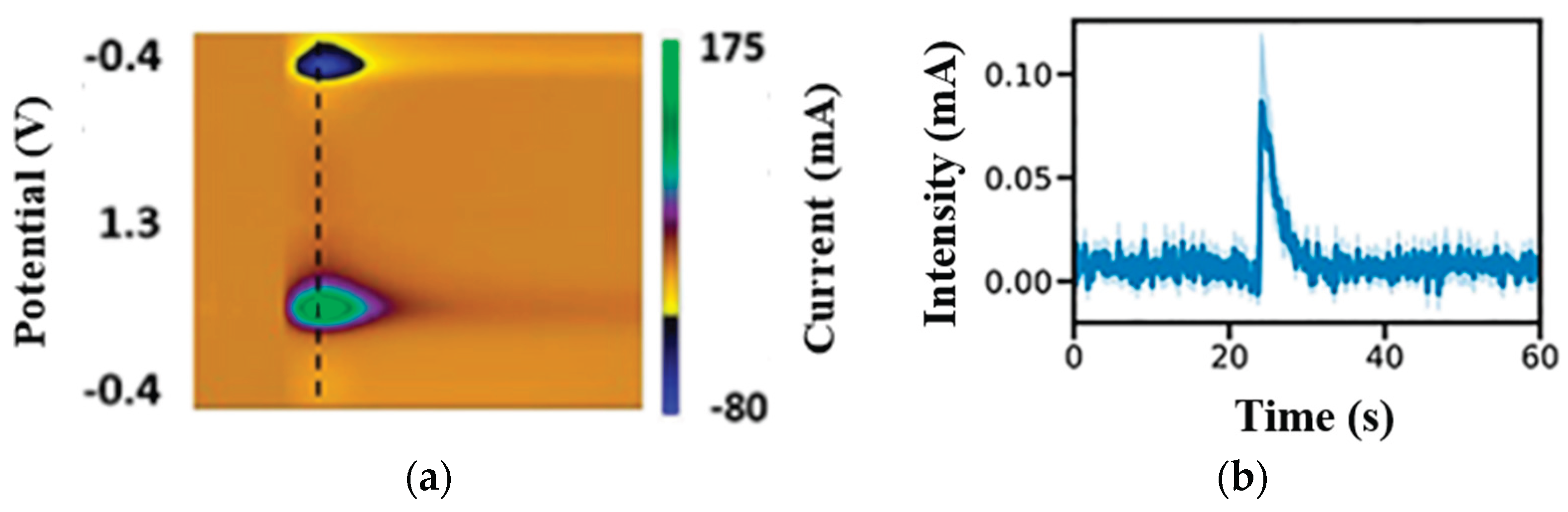

Figure 2 presents a sample patch of a DA release and a time series response of the segmented patch.

3.2. Feature Engineering

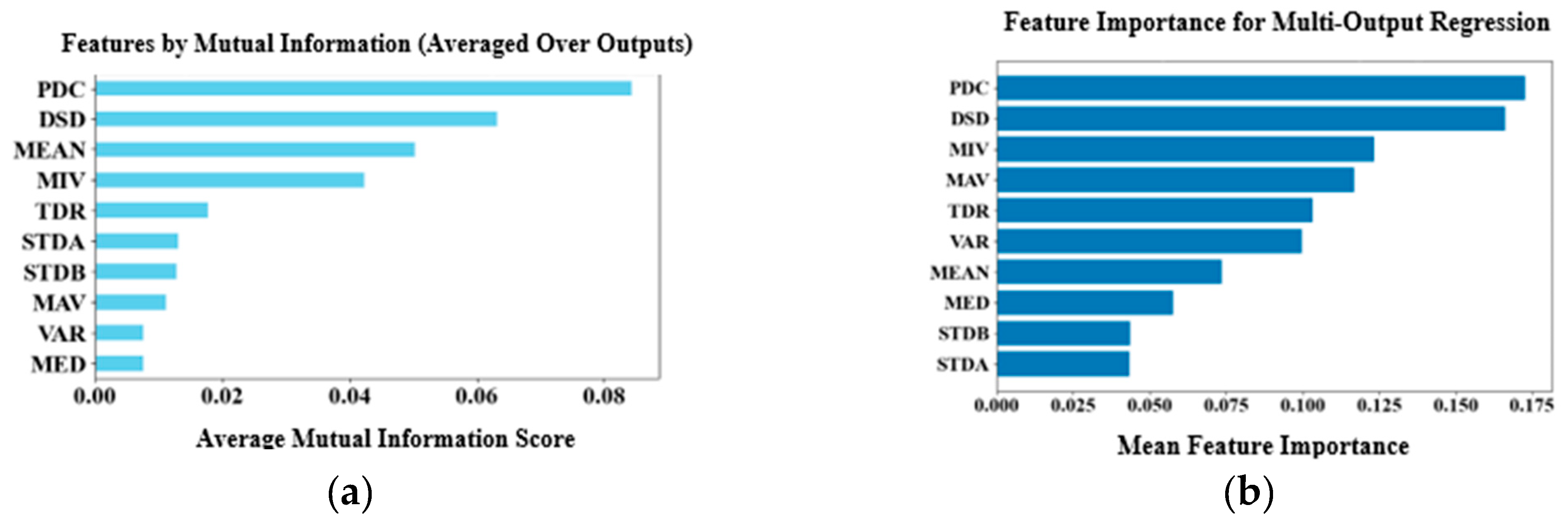

The process involved extracting, selecting, ranking, and normalizing time-domain features from time-series DA dynamics recorded in brain slices labeled with nIRCat, following electrical stimulation of the DLS and DMS. Ten features were extracted from each ROI, namely peak dopamine concentration (PDC), total dopamine release (TDR), dopamine signal decay or DA reuptake (DSD), mean (MEAN), variance (VAR), median (MED), maximum (MAV), minimum (MIV) and values representing two standard deviations above (STDA) and below (STDB) the mean. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was first applied to reduce dimensionality of the dataset, retaining five components that explained 95% of the dataset’s variance. Based on this, the top five features were selected using the mutual information method, which is effective at capturing nonlinear relationships in high-dimensional datasets and identifying features with the strongest mutual information across multiple target variables. The selected features were then ranked by importance through training a Random Forest regressor wrapped in a Multi-Output-Regression to handle the multi-output regression task. Finally, the selected features were normalized using z-score standardization to ensure consistent scaling, aiding faster model convergence during training.

Figure 3 shows the raw features ranked by importance. The proposed model was trained using both the selected feature set and the principal components. This is because principal components lack interpretability, as they do not reveal which original features contributed to each component, and they are computed without considering the target variables.

3.3. Experimental Implementation

In this work, we model the quantification of the DA release, and the prediction of the mice’s ages are regression problems. This is because the concentration or amount of dopamine release and the mice’s ages are continuous numerical values. Both regressions were incorporated in our proposed multivariate regression model.

3.3.1. Modeling the Multivariate Regression

We modeled the multiple linear dependencies between parameters as:

Where: Y represents the target variables corresponding to unknown DA release sites, which can be either the DLS or the DMS. For each sample Y

1 denotes the DA release quantities while Y

2 denotes the mice’s ages. These variables are recorded separately for DLS and DMS, such that Y

1(DLS) and Y

2(DLS) correspond to DA release and mouse age for the DLS site, while Y

1 (DMS) and Y

2 (DMS) correspond to the same at the DMS site. X

P (p

ϵ [

1,

10]) are the computed input features. β

i0 are the intercept term for the i-th output. β

ij are the weight coefficient for the j-th input variable in the i-th output equation. ϵ1, and ϵ2 are the sum of the error terms and noise for each output, assumed to be normally distributed. These materialized the multivariate dependencies as follows

Here, the columns of Y represent the detection targets i.e., individual release sites Y(DLS) and Y(DMS), and the rows correspond to the prediction targets i.e., DA release and mice ages.

3.3.2. The Model

This process involved model selection, training, and refinement through hyperparameter tuning. The models evaluated were either inherently capable of handling multi-output regression or were adapted using the Multi-Output-Regression wrapper from the Scikit-learn library in Python. Support Vector Regressor and Gradient Boosting models (XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost) required the wrapper, while the Gaussian Process Regressor could natively handle multivariate regression tasks. All models were initially trained on 80% of the full dataset, constituted of contributions from samples in each age group by stimulation strength and site, with exact numbers as described on

Table 1. Among the models, CatBoost demonstrated the best performance and was selected using the optuna optimization framework. The selected CatBoost model was trained using three variations of the input data: (1) all raw features, (2) the top five principal components capturing 95% of the dataset’s explained variance, and (3) the top five features identified through feature importance ranking. For all the input data types, five-fold cross-validation was employed to compute the average model performance followed by hyperparameter fine-tuning using grid search and finally validating the optimized model on the remaining 20% of the full data set, constituted of contributions from samples in each age group per stimulation strength (

Table 1).

Table 3 presents the results of the average for 5-folds cross-validation performances for the input data types.

4. Results

4.1. Results from the Parent Model

These results were obtained prior to distilling the CatBoost model. The performance metrics used were the mean squared error (MSE) loss function and R-squared values (R2). MSE was used in the regression tasks of quantification to measure the average squared difference between true and predicted values. MSE offers several advantages, including differentiability and smoothness, which are essential for optimization via gradient descent algorithms. Additionally, it is computationally efficient, disproportionately penalizes larger errors, and facilitates straightforward algebraic solutions in regression analysis. R2 is a widely used measure for the goodness of fit that indicates how well independent variables explain the variation in the dependent variables and has the advantage of being easily interpreted.

4.2. Results Improvement

The initial results in

Table 3 are consistently low for all the input data types. To improve these results, a thresholding technique and model distillation were applied to improve generalization. Here, a threshold of ±10% around the true values for stimulation strengths and mice ages was applied, thereby expanding the confidence interval for the predictions, as supported by Sazanova et al. [

2]. This was followed by model distillation, where knowledge distillation was applied to streamline the complex, nonlinear CatBoost (teacher model) into a kernelized ridge regression (student model) with Gaussian kernel to capture the nonlinear relationships in the multidimensional dataset with multi-output. This approach has the potential to not only reduce model complexity and improve interpretability but also results in a faster model that retains much of the predictive accuracy of the teacher model. Instead of training the student model directly on the true labels, the teacher model was pretrained and its hyperparameters froze. Knowledge was then transferred to the student model during training through the soft targets (the outputs of the teacher model) which provided richer information about class relationships. The student model was trained and tested using the 80:20 data split approach, using all raw data features, the top five principal component features and the top five selected features, consistent with the approach used for the teacher model as described in

Section 3.3.2. As summarized in equation 4, the student model was trained using a combined loss function, i.e., the distillation loss, which measures the difference between the teacher’s and student’s soft predictions, and the student loss, which is the traditional loss computed using the true labels. This dual-objective training allows the student model to learn both from the teacher’s nuanced behavior and the original ground truth. Training iteration was done for 50 epochs before convergence to the validation results on

Table 4. The results present the corresponding performance results for the input data types after thresholding and model distillation with frozen pretrained teacher’s hyperparameters.

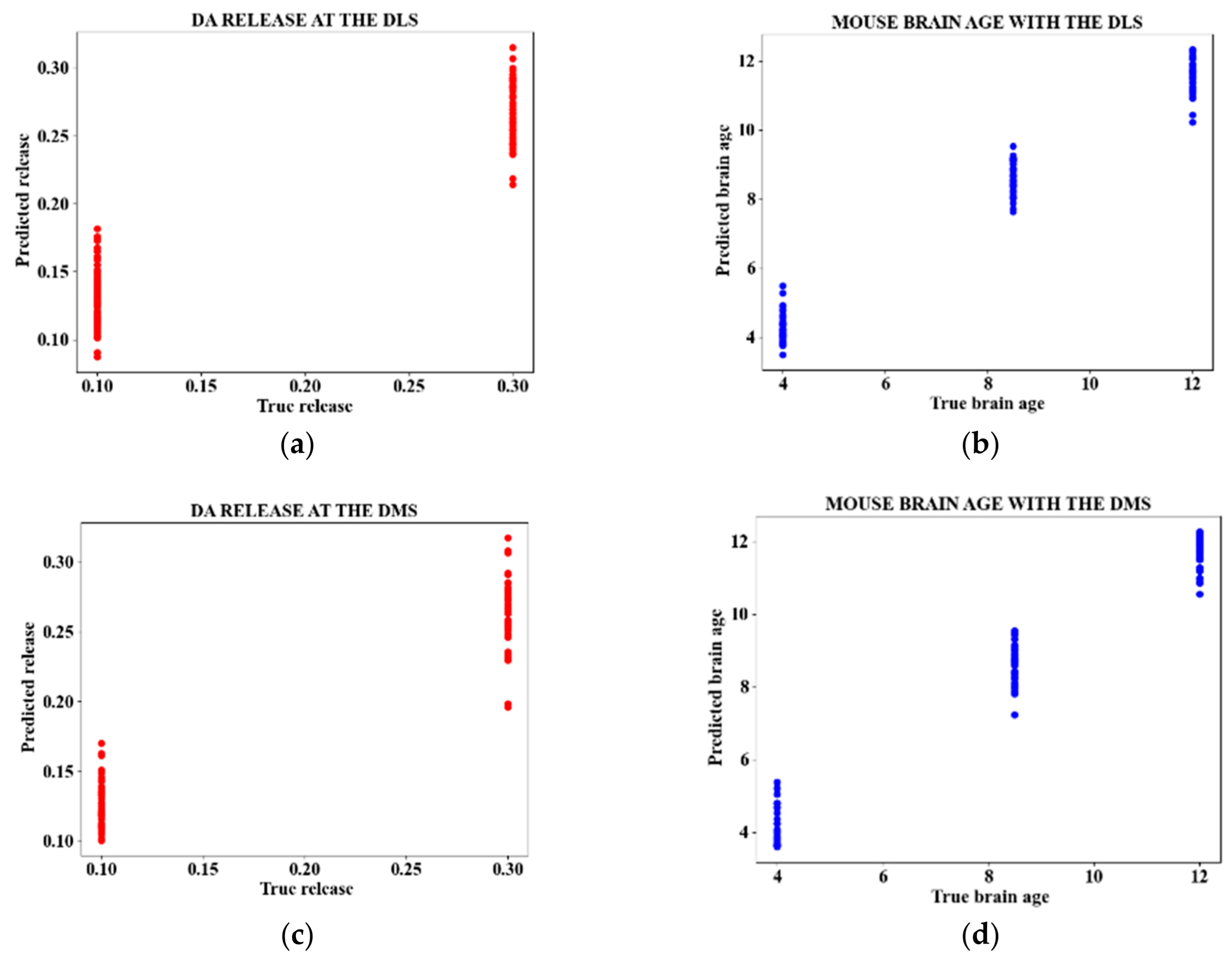

Figure 4 presents sample plots for the predictions of DA release and mouse age for the DLS and DMS.

Where, β ϵ [0,1] is a balancing parameter between the student loss and distillation loss.

5. Validation

We evaluated our approach using the private dataset provided by Siamak et al. [

3] and a publicly available dataset from Matsushita et al. [

19]. The dataset from Siamak et al. [

3] contained 600 nIRCats image frames, whereas the Matsushita et al. [

19] dataset consisted of 1005 images generated via FSCV. Each dataset was split into training and validation subsets in an 80:20 ratio. The proposed approach was subsequently evaluated on both datasets using the same performance metrics (MSE and R-squared values) as summarized in

Table 5. These results are similar with those presented in

Table 4, with minor discrepancies likely attributable to differences in the dataset types.

6. Discussion

In this study, we addressed a key challenge in real-time monitoring of DA dynamics: the simultaneous quantification of DA release and their correlation with brain tissue aging. We analyzed 251 image frames from two mouse brain regions (DLS and DMS) and extracted ten time-domain features to train a CatBoost regressor. This complex model was then distilled into a simpler ridge regressor for interpretability and efficiency. The model was trained using three data configurations: the complete set of raw features, a selected subset of features, and PCA components. The best performance was achieved using all raw features while the worst performance was obtained with PCA components. Model performance was equally superior for mouse age compared to DA release across the three input data types. To enhance the overall performance metrics, the acceptable prediction range was broadened to include values within ±10% of the actual DA release and mouse age giving an MSE of 0.001 and R2 value of 0.97. While this approach improved overall accuracy, it also widened the prediction confidence interval, which reduced precision and increased the risk of misinterpretation. The CatBoost model was then distilled to a gaussian-kernelized ridge regression because of its nonlinear nature and high computational cost, which potentially limit its practical application. Despite these constraints, the results obtained lay a strong foundation for future research focused on the simultaneous detection and quantification of NT concentrations; an essential step toward optimizing deep brain stimulation treatments for neurodegenerative conditions like Parkinson’s disease (PD) and depression. However, several limitations remain: a small and imbalanced dataset was used, only two stimulation intensities were tested, just three age groups were examined, and analysis was restricted to two brain regions. These necessitate further research to validate the results.

7. Conclusions

This study presents a promising approach to real-time monitoring of dopamine dynamics by integrating machine learning techniques for simultaneous quantification of DA release and correlation with brain aging. Despite relying on a limited and imbalanced dataset, the use of a CatBoost model, later distilled to a simpler ridge regression, demonstrated that raw time-domain features yield the most accurate predictions for dopamine release and mouse age at two different brain sites (DLS and DMS). Expanding prediction tolerance for correct predictions improved accuracy but introduced trade-offs in precision. While the current work is constrained by limited stimulation intensities, age groups, and brain regions, it lays a valuable groundwork for future studies. Further research on more comprehensive datasets is crucial for refining the proposed machine learning framework, to enable its practical application in advanced therapies such as deep brain stimulation for conditions like Parkinson’s disease and depression.

References

- I. M. N. Ndumgouo, E Devoe, S Andreescu, S Schuckers “Pattern Recognition of Neurotransmitters: Complexity Reduction for Serotonin and Dopamine”, Biosensors 2025, 15(4), 209. [CrossRef]

- N. Sazonova, J. Njagi, Z. Marchese, M. Ball, S. Andreescu, and S. Schuckers, “Detection and prediction of concentrations of neurotransmitters using voltammetry and pattern recognition,” Ann. Int. Conf. of the IEEE Eng in Med. And Biol. Soci., pp. 3493–3496, 2009. [CrossRef]

- K.S.Siamak, N. Ouassil, S. J. Yang, & M. P. Landry,” Identifying Neural Signatures of Dopamine Signaling with Machine Learning”, ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 2282−2293. [CrossRef]

- Bo Si and Edward Song “Recent Advances in the Detection of Neurotransmitters” MDPI, Chemosensors 4, Jan 2018. [CrossRef]

- Yi Su, S.Bian, and M.Sawan, “Real-time in vivo detection techniques for neurotransmitters: a review,” Royal Society of Chemistry, Analyst. 2020.145.6193. [CrossRef]

- Yifan Da, Shihua Luo &Yang Tian” Real-Time Monitoring of Neurotransmitters in the Brain of Living Animals”, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 138−157. [CrossRef]

- I.Nissar, M. I. Izharuddin, W. A.Mir & T.A.Shaikh, “Machine Learning Approaches for Detection and Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease—A Review” 7th Int. Conf on Ad. Comp& Com. Sys (ICACCS),2021. [CrossRef]

- R.Mathur, V. Pathak and D. Bandil, “Parkinson Disease Prediction Using Machine Learning Algorithm”, Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing 841. [CrossRef]

- Yuki Komoto et al. “Time-resolved neurotransmitter detection in mouse brain tissue using an artificial intelligence-nanogap” Scientific Reports (2020) 10:11244. [CrossRef]

- H. J. Apon, Md. S. Abid, K. A. Morshed, M. M. Nishat, F. Faisal &N.N. I. Moubarak,” Power System Harmonics Estimation using Hybrid Archimedes Optimization Algorithm-based Least Square method,” 13th ICTS, Oct 2021. [CrossRef]

- M.R Kabir, M.M Muhaimin, M.A Mahir, M.M Nishat, F. Faisal &N.N.I. Moubarak,” Procuring MFCCs from Crema-D Dataset for Sentiment Analysis using Deep Learning Models with Hyperparameter Tuning,” IEEE, RAAICON, Dec 2021. [CrossRef]

- A.A Rahman, M.I Siraji, L.I Khalid, F. Faisal, M.M Nishat, M.R Islam, N.N.I Moubarak, “Detection of Mental State from EEG Signal Data: An Investigation with Machine Learning Classifiers,” 14th Int, Conf, KST, Jan 2022. [CrossRef]

- N.N.I Moubarak, N.M.M Omar, VN Youssef, “Smartphone-sensor-based human activities classification for forensics: a machine learning approach” Journal of Electrical Systems and Information Technology 11 (1), 33. [CrossRef]

- C. Hoseok, H. Shin, H. U. Cho, C.D. Blaha, M. L. Heien, O.Yoonbae, K. H. Lee, and D. P. Jang,”Neurochemical Concentration Prediction Using Deep Learning vs Principal Component Regression in Fast Scan Cyclic Voltammetry: A Comparison Study” ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2022, 13, 2288−2297. [CrossRef]

- Doyun Kim et al. “An Automated Cell Detection Method for TH-positive Dopaminergic Neurons in a Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease Using Convolutional Neural Networks” Experimental Neurobiology 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Kammarchedu and A.Ebrahimi “Advancing Electrochemical Screening of Neurotransmitters Using a Customizable Machine Learning-Based Multimodal System” Chemical and biological sensors 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Zhang, S. Shailja, C. Borba, Y. Miao, M.Goebel, R.Ruschel, K. Ryan, W. Smith, and B. S. Manjunath, “Automatic classification and neurotransmitter prediction of synapses in electron microscopy”, Biological Imaging (2022), 2: e6. [CrossRef]

- G.H. G. Matsushita, C. da Cunha and A.Sugi, “Automatic Identification of Phasic Dopamine Release”, 25th International Conference on Systems, Signals and Image Processing (IWSSIP), 2018. [CrossRef]

- G.H.G. Matsushita, A.H. Sugi, Y. M.G. Costa, A. Gomez-A, C. Da Cunha, and L. S. Oliveira, “Phasic dopamine release identification using convolutional neural network” Computers in Biology and Medicine 114 (2019) 103466. [CrossRef]

- S. Yang et al., “Near-Infrared catecholamine nanosensors for high spatiotemporal dopamine imagine”, Nat. Protoc.2021,16,3026-3048. [CrossRef]

- Beyene, A.; Delevich, K.; et al. Imaging striatal dopamine release using a nongenetically encoded near infrared fluorescent catecholaminenanosensor. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, No. eaaw3108. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).