I. Introduction

Functional Neurological Disorder (FND) is a condition where symptoms cannot be explained by the current disease model [

1]. FND is one of the most common yet under-recognized conditions in modern neurology, with a substantial impact on patients and healthcare systems [

2]. Despite affecting an estimated 80–140 per 100,000 people (approximately 0.1% of the population), and with 10–22 new cases per 100,000 each year, FND accounts for a disproportionately high number of neurology referrals [

3]. Research shows that 9% of neurology inpatients and around 16% of outpatients are diagnosed with FND. About one third of new neurology clinic patients have partially unexplained symptoms; however, they have received relatively little development of rehabilitation technologies [

4].

This means that FND is not rare – it is, in fact, a frequent diagnosis in neurology clinics. Yet public awareness remains low. Symptoms such as non-epileptic seizures, limb weakness, and speech difficulties are often misunderstood, despite being very real, often disabling, and requiring complex, ongoing care [

2]. Diagnosis is frequently delayed, leading to repeated hospital visits, unnecessary investigations, and worsening outcomes.

Managing FND places a significant financial burden on healthcare systems and on society as a whole. These costs include both direct medical expenses (like tests, emergency admissions, and specialist care) and indirect costs (like lost productivity and disability claims). A recent economic review found the excess annual cost per FND patient ranges from

$5,000 to

$85,000 (in 2021 USD), depending on severity and healthcare use [

2]. In the U.S., hospital charges for FND-related admissions totalled

$1.2 billion in a single year [

4]. In Europe, the per-patient costs of FND are on par with or exceed those of chronic neurological diseases like epilepsy – especially when indirect costs are factored in. Many FND patients are unable to work, with disability levels similar to conditions such as multiple sclerosis [

4].

Clinical studies on motor FNDs have highlighted positive diagnostic criteria, e.g., Hoover’s sign and hip abductor sign [

5]. Hoover’s sign signifies voluntary hip extension weakness, which improves with opposite hip flexion against resistance, while the hip abductor sign involves involuntary abduction of the weak leg when the opposite leg is abducted against resistance. We hypothesize that these implicit motor processes [

6], which may not be under volitional control, can be leveraged in an operant approach [

7] to relearn crucial balance between pre-existing beliefs and sensory feedback of consequences [

8] to facilitate voluntary control.

Neuroimaging can provide mechanistic understanding of the balance between ‘bottom-up’ (sensory, autonomic, nociceptive) and ‘top-down’ (expectation, belief, emotion) sources [

9] where the weightings may be altered during biofeedback training with direction of attention [

8]. Here, hypoactive sensorimotor areas and/or a lack of sense of agency (temporo-parietal junction)[

10] can be monitored with portable neuroimaging. We have showed the feasibility of functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) to capture efference copy/corollary discharge mechanisms in healthy [

11]. Then, we have showed the feasibility of an implicit operant conditioning paradigm to address learned non-use post-stroke [

12] that needed to be feasibility tested in functional weaknesses. Therefore, we performed co-production of exploratory space in portable brain imaging and generative process [

13] to de-risk new technology development incorporating operant conditioning in FND rehabilitation [

14].

Treatment approaches vary, with recommendations for a multidisciplinary approach including cognitive behaviour therapy. Hypnosis and suggestion have been explored as a treatment option [

15]. In the absence of evidence-based therapy for acute functional stroke symptoms, the study by Sanyal et al. [

16] introduced hypnotherapy as an additional treatment option for functional symptoms mimicking acute stroke. The paper reported on the outcomes of the first 68 cases treated using hypnotherapy, following an approved clinical pathway, including an audit of response rates and complications. In the current study, we assessed portable brain imaging using an affordable low-channel fNIRS system to evaluate brain-based measures of one FND patient’s response to hypnotherapy classified with five neurotypical healthy subjects responses.

II. Methodology

A. Data Collection

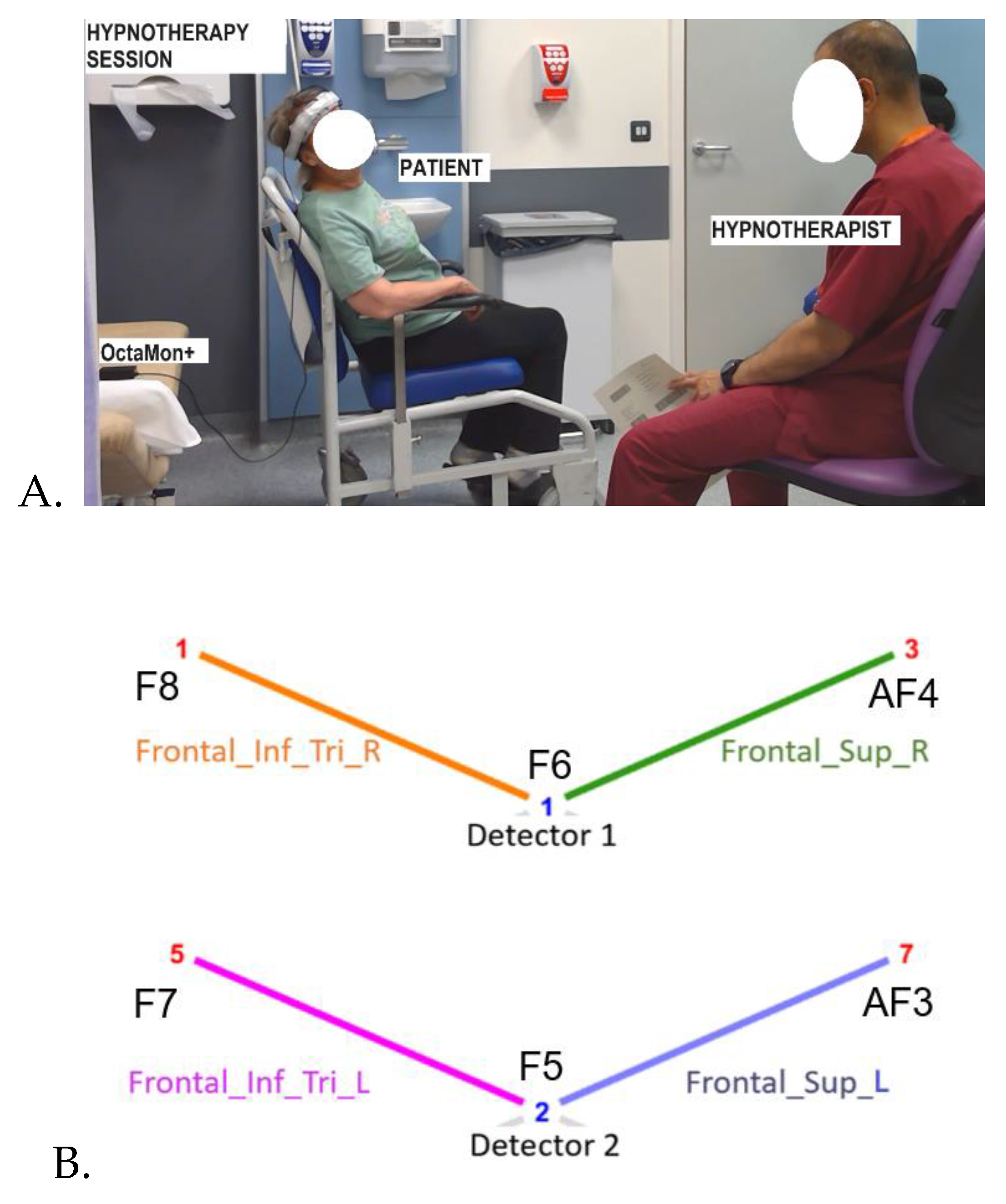

Participants: A total of 5 healthy volunteers were recruited from the staff of Royal Stoke University Hospital, Stoke-on Trent, UK for testing frontal fNIRS montage during hypnotherapy session. One FND patient feasibility tested the frontal fNIRS montage. Informed consent was obtained from all participants for the case study.

fNIRS Measurements: Portable 8-channel fNIRS device OctaMon+ (Artinis Medical Systems) was utilized to measure hemodynamic responses in two short-separation channels and four long-separation (~3.5cm) frontal cortical channels targeting Inferior frontal gyrus, triangular part (Frontal_Inf_Tri_L); Inferior frontal gyrus, triangular part (Frontal_Inf_Tri_R); Superior frontal gyrus, dorsolateral (Frontal_Sup_L); Superior frontal gyrus, dorsolateral (Frontal_Sup_R), as shown in

Figure 1. The measurements were conducted at wavelengths of 760 and 850 nm with a sampling frequency of 10 Hz synchronized with audio-video recording of the hypnotherapy session using Lab Streaming Layer (LSL). Cortical brain activity was measured approximately 1.5 cm beneath the scalp, with a spatial resolution of up to 1 cm [

17]. Trials were visually inspected for physiological quality including the presence of cardiac oscillations (~1 Hz).

B. Data Analysis

fNIRS Data Processing: Event triggers marking the start of the session, the onset of hypnotic induction, and the beginning of the hypnotic suggestion were identified from synchronized audio–video recordings to delineate the baseline period (pre- hypnotherapy induction) and the suggestion period (post- hypnotherapy induction). These triggers were used to process the fNIRS data using HOMER3 [

18]. Raw light intensity data were converted to optical density signals, and subsequently to concentration changes in oxyhemoglobin (HbO) and deoxyhemoglobin (HbR) using the modified Beer–Lambert law [

18]. A general linear model (GLM) was implemented in HOMER3 using the function hmrDeconvHRF_DriftSS, which supports Gaussian basis functions. To model continuous-state hemodynamic changes during the 60-second baseline and post-hypnotic induction, GLM yielded 61 Gaussian regressors, allowing estimation of beta values that represent temporally localized responses across the 60-second period.

Classification of post-hypnotic suggestion state: 61 beta values for baseline and 61 beta values at onset of hypnotherapy suggestion (post- hypnotherapy induction) for each of the 5 healthy subjects were used for training and 10-fold cross-validation. Classification was performed using MATLAB’s Classification Learner app. Beta values extracted from four HbO channels, specifically the inferior frontal gyrus (triangular part) and superior frontal gyrus (dorsolateral), bilaterally (see

Figure 1B), were used as predictor variables, and class labels representing experimental conditions (baseline, suggestion state) were assigned as the response variable. The dataset was imported into the app, and models were trained using 10-fold cross-validation to estimate generalization performance. Multiple classifiers (e.g., decision trees, support vector machines, and ensemble methods) were evaluated, and the top three performing model was selected based on classification accuracy. The trained model was then tested using FND patient dataset. To interpret model decisions and quantify the contribution of each predictor, Shapley (SHAP) values were computed, providing feature importance scores that reflect each region’s marginal impact on classification outcomes.

III. Results

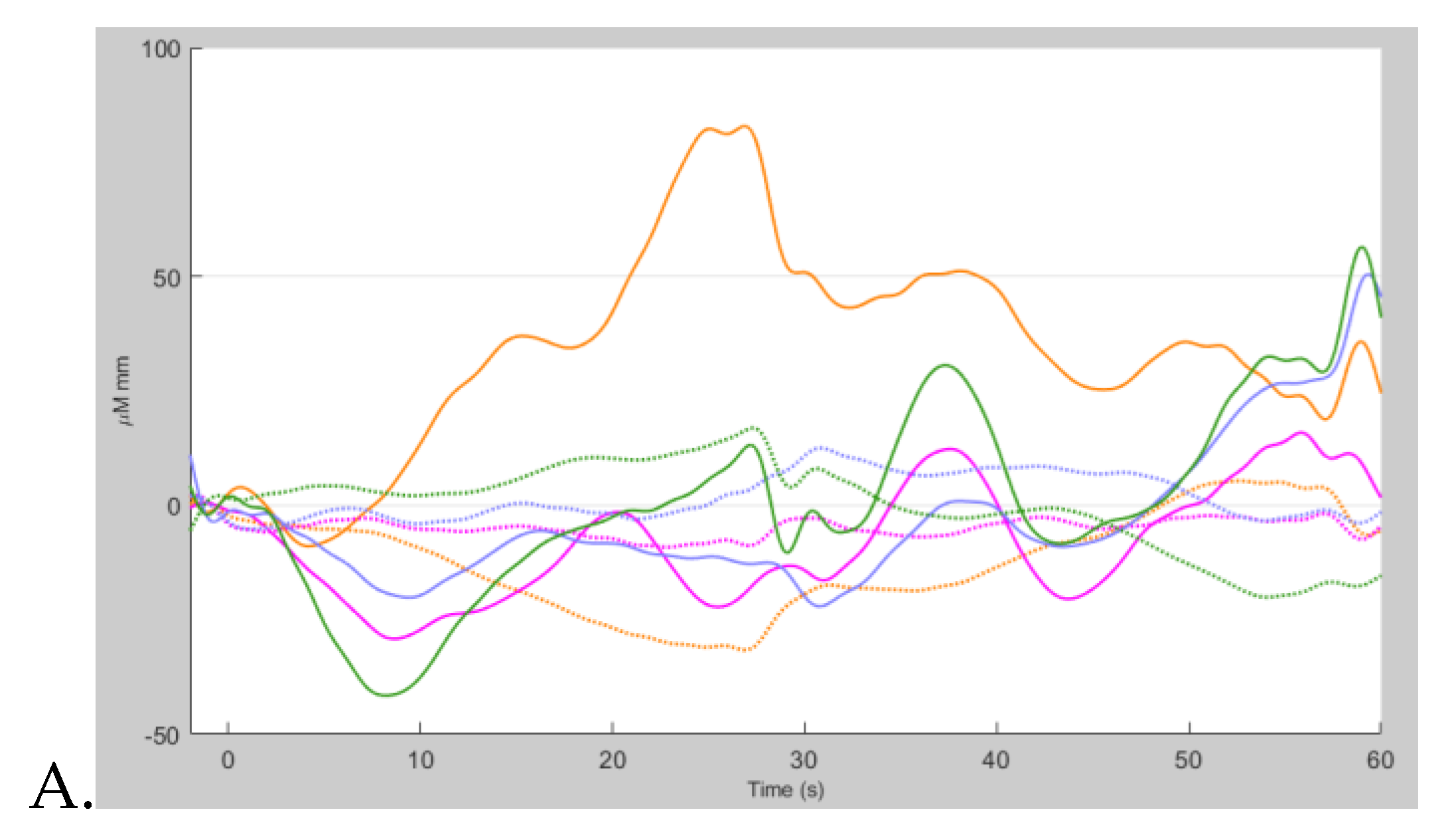

Group-averaged hemodynamic responses from 5 healthy volunteers over multiple hypnotherapy sessions revealed distinct changes in frontal cortical oxygenation during the suggestion period (post- hypnotherapy induction). At the start of the session (baseline), HbO and HbR levels remained stable across all regions of interest (

Figure 2A), reflecting a resting-state profile with minimal cognitive engagement. Immediately following the post-hypnotic induction period and the beginning of the hypnotic suggestion, an increase in HbO and a corresponding decrease in HbR were observed bilaterally in the inferior frontal gyrus (triangular part) and superior frontal gyrus (dorsolateral) –

Figure 2B. These changes are consistent with regional cerebral blood flow, suggesting engagement of frontal executive and attentional networks during the transition into the hypnotic suggestion phase. The observed pattern (see

Figure 2) was most pronounced in left hemisphere optodes, with HbO levels decreasing by an average of about -20 µM·mm and HbR peaking around 10 µM·mm, indicating cortical activation associated with onset of hypnotic suggestion.

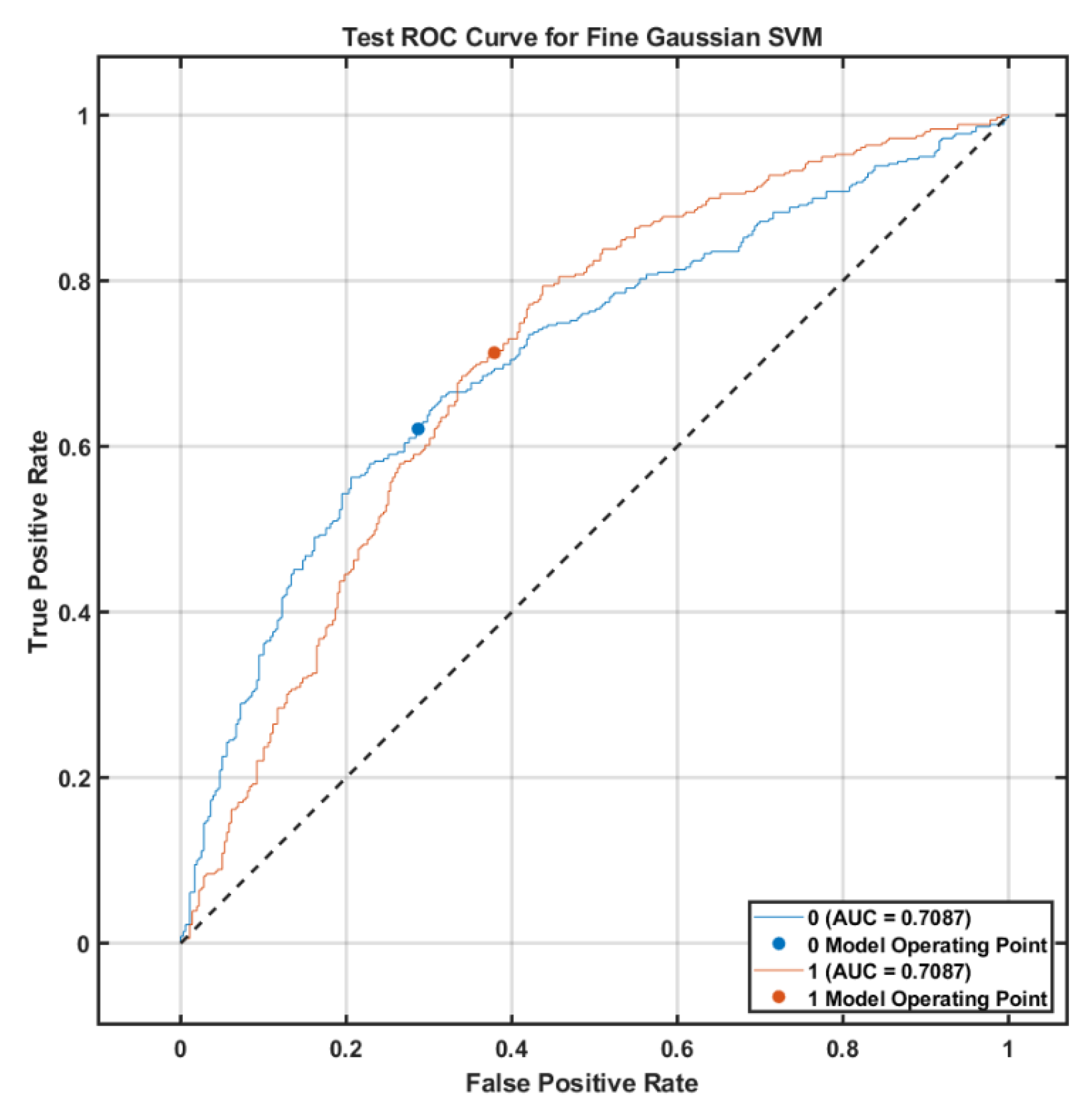

Machine learning models were trained using beta values from HbO channels. The top three models found using 10-fold cross-validation and tested on an independent FND dataset were support vector machine (SVM), k-nearest neighbors (KNN), and Bagged Trees as shown in

Table 1. The Fine Gaussian SVM model achieved the highest performance, with a validation accuracy of 62.83% and a test accuracy of 66.71%, compared to the KNN model, which yielded a validation accuracy of 62.33% and a test accuracy of 62.67%.

Figure 3 shows the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve for Fine Gaussian SVM Classifier with an area under the curve of 0.71 for each class indicating moderate classification accuracy on the FND test set.

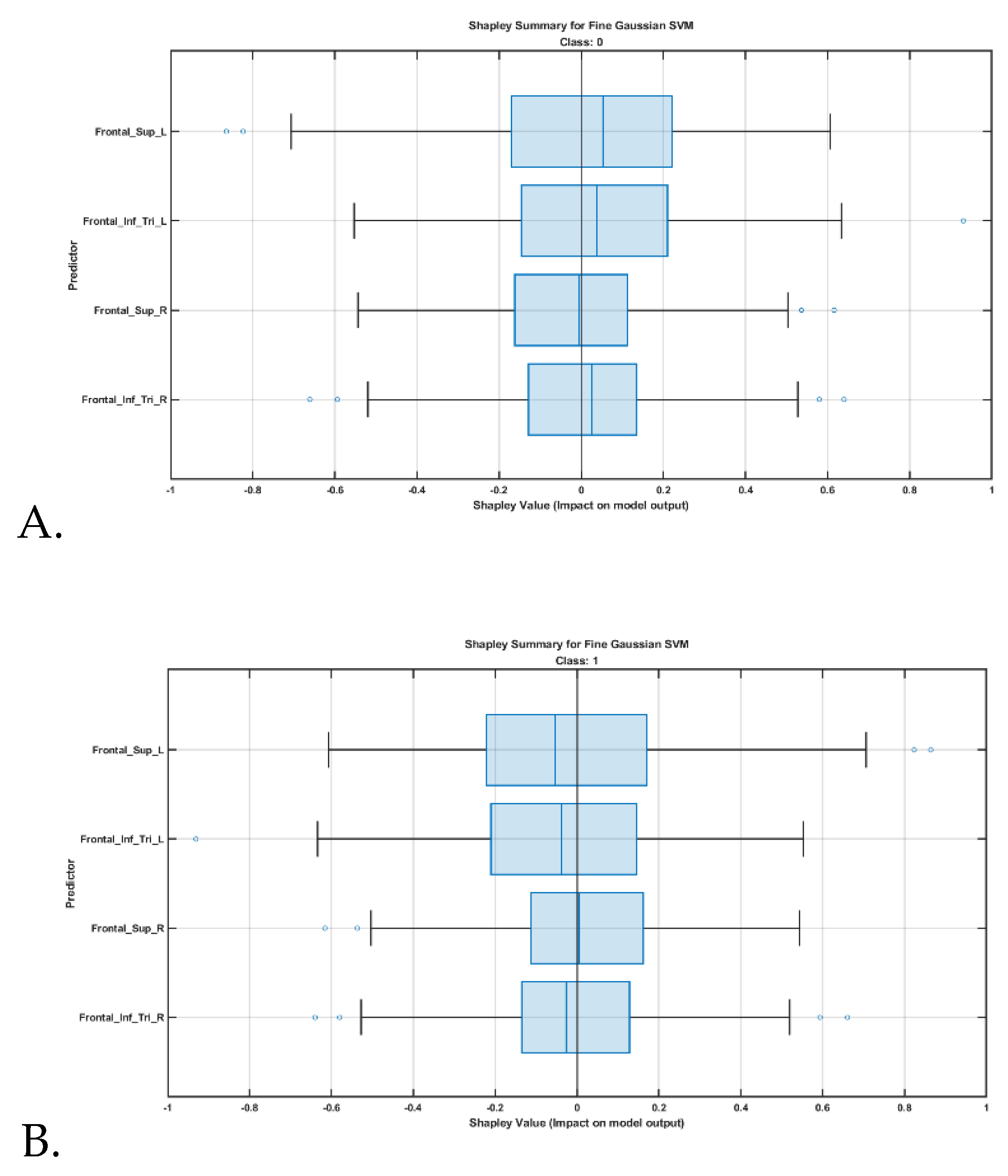

Feature contributions were further interpreted using Shapley value analysis, shown in

Figure 4, highlighting the relative influence of each cortical region on classification outcomes. SHAP (Shapley additive explanations) analysis revealed that beta values from the left superior frontal gyrus, dorsolateral was the most influential feature for predicting the post-hypnotic suggestion state.

IV. Discussion

In this proof-of-concept study, we demonstrate the feasibility of using functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) to assess cortical hemodynamic responses during a hypnotherapy session. Our findings support the use of portable neuroimaging to capture neurophysiological changes associated with hypnotic suggestion in real-world, ecologically valid settings. This work is built on prior fMRI studies in FND [

19] and hypnotizability [

20] that have identified functional connectivity patterns in individuals with high hypnotizability, a linked trait [

21].

Indeed, high hypnotizability has been increasingly recognized as a trait linked to FND, with both conditions involving altered agency, heightened suggestibility, and disrupted self-monitoring networks. Neuroimaging studies reveal overlapping abnormalities in the salience, executive control, and default mode networks, particularly involving increased functional connectivity between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex regions implicated in both hypnotic responsiveness and FND pathophysiology. This convergence suggests that individuals with high hypnotizability may have a neurocognitive predisposition to FND, offering insight into both diagnosis and treatment responsiveness. Hypnosis is thought to increase functional connectivity between dopamine-rich regions such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), enabling enhanced top-down modulation of sensory and affective processes. These mechanisms have been implicated in phenomena like hypnotic analgesia, where the DLPFC contributes to cognitive reinterpretation and the dACC to the modulation of negative affect.

In the current study, SHAP (Shapley additive explanations) analysis of machine learning model outputs revealed that beta values from the left hemisphere were more influential predictors of the post-hypnotic suggestion state. The predominance of left-hemisphere cortical predictors particularly the left superior frontal gyrus (partly dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) and the left inferior frontal gyrus (pars triangularis) in classifying the post-hypnotic suggestion state aligns with prior neuroimaging and neuromodulation studies [

22],[

23]. The left DLPFC has been repeatedly implicated in executive control, cognitive reframing, and the modulation of attentional focus which are the core processes engaged during hypnotic suggestion [24]. Moreover, functional imaging studies have shown that hypnotic states are associated with increased connectivity between the DLPFC and salience network regions, including the insula, particularly within the left hemisphere. The left inferior frontal gyrus, a region linked to semantic control and verbal integration, may further support the assimilation of verbal suggestions during hypnosis. These findings are also consistent with theories proposing that the “left-brain interpreter” plays a central role in constructing explanatory narratives, a mechanism that may underlie the acceptance and internalization of hypnotic suggestions. Collectively, our findings support the interpretation that left frontal regions are key contributors to the neural dynamics of hypnotic processing.

Our feasibility study lays the groundwork for future applications of fNIRS-guided hypnotherapy in FND. We envision a future direction involving operant conditioning using suggestion and imagery delivered through immersive virtual reality (VR) environments, using real-time fNIRS feedback to reinforce volitional control [

14]. In FND, symptoms are often linked to mismatches between internal predictions and sensory feedback; thus, VR-based operant conditioning may help recalibrate attention and agency by manipulating sensory precision. Importantly, the co-development of such platform with patients is crucial to ensure acceptability and usability, enabling home-based rehabilitation through immersive, game-like experiences [

7]. Although biofeedback is a promising mind–body technique, it remains underutilized relative to conventional physiotherapy. Our proposal seeks to bridge that gap by co-producing a VR-facilitated hypnotherapy system that is responsive using real-time portable brain imaging [

14].

This study has several limitations. First, the use of a low-density fNIRS system limited spatial coverage, restricting our ability to assess broader cortical dynamics. Second, small sample size limits generalizability, and larger, controlled studies are needed to validate these findings. Third, our analysis was based on beta values, and future work should incorporate dynamic functional connectivity methods to better capture the temporal evolution of brain states during hypnotic induction and suggestion. One major limitation of our study design is the lack of a comparison condition assessing brain responses to hypnotic suggestion both with and without formal hypnotherapy induction, preventing us from isolating the specific neural effects of being in a hypnotic state. In conclusion, fNIRS enabled the assessment of brain response to hypnotherapy, and simultaneous audio-video-fNIRS paradigm may provide a convenient and cost-effective method for evaluating hypnotherapy at the point of care with ecological validity.

V. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that fNIRS can be used to detect brain responses to hypnotherapy in a portable, cost-effective, and ecologically valid manner. The integration of real-time brain monitoring with immersive therapeutic interventions may open new avenues for personalized, home-based neurorehabilitation, particularly for individuals with functional motor symptoms.

Author Contributions

Pushpinder Walia: Methodology. Ranjan Sanyal, MD: Conceptualization, Clinical Supervision, Investigation, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing. Abhijit Das, MD: Conceptualization, Clinical Supervision, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing. Anirban Dutta, PhD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, Resources, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

References

- S. Aybek and D. L. Perez, ‘Diagnosis and management of functional neurological disorder’, bmj, vol. 376, 2022.

- S. A. Finkelstein, C. Diamond, A. Carson, and J. Stone, ‘Incidence and prevalence of functional neurological disorder: a systematic review’, J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, vol. 96, no. 4, pp. 383–395, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. O’Mahony, G. Nielsen, S. Baxendale, M. J. Edwards, and M. Yogarajah, ‘Economic Cost of Functional Neurologic Disorders: A Systematic Review’, Neurology, vol. 101, no. 2, pp. e202–e214, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. D. Stephen, V. Fung, C. I. Lungu, and A. J. Espay, ‘Assessment of Emergency Department and Inpatient Use and Costs in Adult and Pediatric Functional Neurological Disorders’, JAMA Neurol, vol. 78, no. 1, pp. 88–101, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. McWhirter, J. Stone, P. Sandercock, and W. Whiteley, ‘Hoover’s sign for the diagnosis of functional weakness: A prospective unblinded cohort study in patients with suspected stroke’, Journal of Psychosomatic Research, vol. 71, no. 6, pp. 384–386, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Tsay, A. M. Haith, R. B. Ivry, and H. E. Kim, ‘Interactions between sensory prediction error and task error during implicit motor learning’, PLOS Computational Biology, vol. 18, no. 3, p. e1010005, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Dutta et al., ‘Extended Reality Biofeedback for Functional Upper Limb Weakness: Mixed Methods Usability Evaluation’, JMIR XR and Spatial Computing (JMXR), vol. 2, no. 1, p. e68580, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, ‘Neurocomputational Mechanisms of Sense of Agency: Literature Review for Integrating Predictive Coding and Adaptive Control in Human–Machine Interfaces’, Brain Sci, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 396, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, ‘Bayesian predictive coding hypothesis: Brain as observer’s key role in insight’, Medical Hypotheses, vol. 195, p. 111546, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Bühler, S. Weber, S. Loukas, S. Walther, and S. Aybek, ‘Non-invasive neuromodulation of the right temporoparietal junction using theta-burst stimulation in functional neurological disorder’, BMJ Neurol Open, vol. 6, no. 1, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kamat et al., ‘Directed information flow during laparoscopic surgical skill acquisition dissociated skill level and medical simulation technology’, npj Sci. Learn., vol. 7, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Kumar, N. Sinha, A. Dutta, and U. Lahiri, ‘Virtual reality-based balance training system augmented with operant conditioning paradigm’, BioMedical Engineering OnLine, vol. 18, no. 1, p. 90, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Dutta et al., ‘Co-design and Usability Evaluation of an Extended Reality Biofeedback Platform for Functional Upper Limb Weakness’, JMIR XR and Spatial Computing (JMXR), Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- ‘Platform Technology for VR Biofeedback Training under Operant Conditioning for Functional Limb Weakness: A Proposal for Co-production of At-Home Solution (REACT2HOME)’, JMIR Preprints. Accessed: Mar. 02, 2025. M. H. Connors, L. Quinto, Q. Deeley, P. W. Halligan, D. A. Oakley, and R. A. Kanaan, ‘Hypnosis and suggestion as interventions for functional neurological disorder: A systematic review’, Gen Hosp Psychiatry, vol. 86, pp. 92–102, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Sanyal, M. Raseta, I. Natarajan, and C. Roffe, ‘The use of hypnotherapy as treatment for functional stroke: A case series from a single center in the UK’, Int J Stroke, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 59–66, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Ferrari and V. Quaresima, ‘A brief review on the history of human functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) development and fields of application’, NeuroImage, vol. 63, no. 2, pp. 921–935, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Huppert, S. G. Diamond, M. A. Franceschini, and D. A. Boas, ‘HomER: a review of time-series analysis methods for near-infrared spectroscopy of the brain’, Appl Opt, vol. 48, no. 10, pp. D280–D298, Apr. 2009.

- D. L. Perez et al., ‘Neuroimaging in Functional Neurological Disorder: State of the Field and Research Agenda’, Neuroimage Clin, vol. 30, p. 102623, 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Hoeft et al., ‘Functional brain basis of hypnotizability’, Arch Gen Psychiatry, vol. 69, no. 10, pp. 1064–1072, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- K. Roelofs, K. A. Hoogduin, G. P. Keijsers, G. W. Näring, F. C. Moene, and P. Sandijck, ‘Hypnotic susceptibility in patients with conversion disorder.’, Journal of abnormal psychology, vol. 111, no. 2, p. 390, 2002.

- B. A. Parris, ‘The role of frontal executive functions in hypnosis and hypnotic suggestibility’, Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 211–229, 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. A. Parris, ‘The Prefrontal Cortex and Suggestion: Hypnosis vs. Placebo Effects’, Front. Psychol., vol. 7, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Jiang, M. P. White, M. D. Greicius, L. C. Waelde, and D. Spiegel, ‘Brain Activity and Functional Connectivity Associated with Hypnosis’, Cereb Cortex, vol. 27, no. 8, pp. 4083–4093, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).