1. Introduction

The mental health of health care professionals has been widely investigated because of its importance in individual and collective well-being, in addition to its direct influence on the quality of services provided to the population. Among these professionals, veterinarians have been identified as particularly vulnerable to psychological distress owing to the specific challenges they face in their practice, animal care, and interactions with their clients [

1,

2,

3]. In the case of pets, the emotional demands include dealing with the animals and clients suffering in illness situations, their own mourning, that of the clients related to the animals’ death, and the ethical dilemmas involved in conducting euthanasia [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In this context, veterinarians’ mental health has emerged as a relevant concern in the profession, boosted by growing evidence of high levels of stress, fatigue, and impairment of well-being [

5,

6,

7]. Studies conducted in the United Kingdom[

8], the United States [

5,

9], Australia [

10], and Canada [

11] indicated that veterinarians deal with high emotional load and significant professional dissatisfaction, and emphasize the urgency of interventions directed towards the promotion of the psychological well-being of such professionals.

Although psychological distress is widely documented in several health areas, Brazil does not have national research specifically intended to investigate the mental health of veterinarians, revealing a significant gap in the understanding of the challenges faced by these professionals. This scenario is particularly concerning considering that Brazil has one of the largest per capita concentrations of veterinarians worldwide. By 2022, Brazil had an average of 77.4 veterinarians per every 100 thousand inhabitants, with approximately 9,250 new professionals entering the profession every year, which is lower than that of Latvia, a country with 1,934,379 inhabitants and 2,500 veterinarians, with a ratio of 129 professionals per 100,000 inhabitants [

12]. Brazil has more than 200,000 registered veterinarians, with a predominance of female veterinarians in clinical practice. Most professionals work in the private sector, particularly in companion animal clinics, and there is significant regional heterogeneity in working conditions owing to the country’s continental dimensions [

12]. The Brazilian veterinary sector is characterized by high professional demands, regional inequalities, and limited mental health infrastructure, making it particularly vulnerable to the challenges addressed in this study [

12].

The literature shows that sociodemographic factors such as age, gender, and education influence workers’ mental health in several fields. For example, young women and professionals starting their careers frequently report greater vulnerability to psychological distress [

13,

14]. In addition, the type of employment relationship, workload, and balance between personal and professional life also play essential roles in the well-being of such professionals [

15,

16]. However, the relationship between these variables and mental health has been poorly explored in the context of veterinary medicine, particularly in representative samples [

17,

18].

Another important aspect of understanding the factors involved in the mental health of veterinary professionals is the coping strategies adopted to deal with stressful situations in the work environment. This study is grounded in the stress-coping framework proposed by Lazarus and Folkman [

19], which distinguishes between adaptive and maladaptive strategies in response to occupational stress. Coping can be defined as a set of strategies used to face emotional and situational challenges and can be classified as adaptive or maladaptive depending on the efficacy of the response to stress [

19]. Adaptive coping strategies, such as the search for social support and positive reassessment, have been associated with better mental health indicators [

20,

21]. However, there is a lack of studies investigating the interaction between sociodemographic and occupational variables and coping strategies in the veterinary context.

Using a representative national sample, this study explored how sociodemographic and occupational factors, along with coping strategies, interact to predict the mental health of Brazilian veterinarians, focusing on their well-being and psychological distress. This research was inspired by a study conducted in the United States by Merck and replicated in Brazil with support from Merck Sharp and Dohme Brasil (MSD Brasil) [

22,

23]. While previous studies have consistently shown high levels of stress among veterinarians, findings on the protective role of coping strategies and the influence of demographic factors remain inconclusive. For instance, although physical activity is widely considered beneficial, some studies have reported mixed effects on the psychological outcomes in this population. [

24,

25]

This study sought to determine which factors exert the most significant influence on veterinarians’ mental health, and how these factors interact. Notably, the findings revealed that dissatisfaction with career choice, excessive workload, and lack of work-life balance were central to psychological distress, whereas adaptive behaviors and social support were linked to better well-being. These insights are critical for informing targeted interventions and institutional policies that foster sustainable and mentally healthy veterinary medicine careers.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate how sociodemographic characteristics, occupational conditions, and coping strategies contribute to the psychological distress and well-being of veterinarians in Brazil using a representative national sample.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted between June 29th and July 25, 2022, involving male and female veterinarians actively working in Brazil. This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Faculdade Inspirar (Opinion No. 31645220.4.0000.5594) and was registered with the National Research Ethics Commission (CONEP) of the Brazilian Ministry of Health.

Participants were recruited via email from registry data sourced from the databases of the National Association of Veterinary Clinicians for Small Animals (Anclivepa Brazil) and MSD Brazil, which collectively comprise approximately 20,000 registered professionals. The inclusion criterion required participants to be of legal age (≥18 years), corresponding to adulthood in Brazil. As veterinary medicine in Brazil is a post-secondary course that requires a high school diploma, all participants were expected to have completed at least one undergraduate level of education. Approximately 2,000 professionals completed the online questionnaire, and 1,992 responses were deemed valid for analysis. A convenience sampling strategy was used based on existing professional registries, which may have introduced selection bias.

Participation was secured following the presentation of the study objectives and the request for participants to read and agree to the Informed Consent Form, with the assurance of participant anonymity throughout all stages of the study. The participants were engaged in clinical veterinary practices in various regions of Brazil.

Although recruitment efforts aimed to ensure geographic and sectoral diversity, the use of convenience sampling may result in a sample that is not fully representative of the broader veterinary population. In particular, individuals who were more aware of or concerned with mental health topics may have been more inclined to participate. Therefore, caution is warranted when generalizing these findings to all Brazilian veterinarians.

2.2. Instruments

This study examined issues pertaining to participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, including age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, number of children, and type of residence. Additionally, it addressed aspects related to work and career such as income, position held, time since graduation, weekly workload, presence of a second job, and level of satisfaction with the profession. The selection of coping strategies was based on literature identifying common self-care behaviors among healthcare professionals and prior national wellness surveys in the veterinary field.

Coping strategies were assessed using ten questions on a four-point Likert scale (frequently, sometimes, seldom, and never). The analyzed activities included spending time with family, practicing physical exercise, sleeping at least eight hours a night, socializing with friends, dedicating time to hobbies, reading for pleasure, traveling for leisure, doing voluntary work, and attending yoga sessions. The total score showed evidence of internal consistency, with a coefficient alpha of 0.75, which is considered acceptable for exploratory research [

26].

The Kessler Screening Scale for Psychological Distress (K6) was used to evaluate symptoms of psychological distress [

27]. Evidence of the validity of the Brazilian version of the K6 has been established through correlations with clinical diagnoses and other psychological scales [

28]. This scale consists of six questions that gauge the frequency with which individuals have experienced symptoms of anxiety and depression over the past 30 days. Responses to each question were recorded on a five-point Likert scale: 0 (none of the time), 1 (a little of the time), 2 (part of the time), 3 (most of the time), and 4 (all the time), leading to a total score ranging from 0 to 24. A score of 13 or above (K6 ≥ 13) [

27] is indicative of mental distress. The scale showed evidence of internal consistency, with a coefficient alpha of 0.81, which is considered acceptable for exploratory research [

26].

The Physician Well-Being Index (PWBI) was used to assess the subjective well-being of veterinarians and identify professionals whose level of psychological distress could affect their professional performance [

29]. The scale covers symptoms, such as exhaustion, discouragement, negative perceptions of quality of life, stress, fatigue, and other indicators of emotional distress. The instrument was comprised of seven binary items (0 = No; 1 = Yes), and the total score was obtained by summing all affirmative answers, with higher scores indicating a higher risk of well-being. A score lower than four (<4) was adopted as the cutoff point, indicating the absence of subjective psychological difficulties. The total PWBI score showed evidence of internal consistency, with an alpha coefficient of 0.72. Evidence of validity includes associations with indicators of burnout, distress, and professional performance in previous studies [

29].

The K6 and PWBI were selected for their brevity, strong psychometric properties, and prior use in occupational mental health studies, making them appropriate for busy professionals, such as veterinarians [

27,

28,

29].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Sample characteristics and descriptions are presented as frequencies (n) and percentages, respectively. The results of the scale K6 and its scores are presented as mean, standard deviation, and 95% confidence interval. The frequency (n) and percentage of the total n were used to show the seven items related to PWBI. Answers “I prefer not to answer” were considered missing values. In this study, the proportion of missing values for variables ranged up to 10%; therefore, all missing values were entered using the Expected Maximization (EM) algorithm method. The EM algorithm was chosen due to its robust performance in handling datasets with up to 10% of missing data. Compared to simpler techniques such as listwise deletion or mean substitution, EM preserves statistical power and reduces bias in parameter estimates, which is particularly important in large-scale surveys where maintaining data completeness is essential for reliable multivariate analyses.

For the categories of instruments K6 (scores lower than 13 indicate absence of mental distress; scores equal to or higher than 13 indicate possible presence of mental distress) and the PWBI (less than four indicating the presence of subjective well-being; equal to or higher than four indicating possible absence of subjective well-being), multiple logistic regression was used to identify significant effects of sociodemographic factors and coping strategies. Binary logistic regression was chosen because of the dichotomous nature of the main outcomes (presence/absence of psychological distress and high/low well-being), enabling the estimation of adjusted odds ratios. The assumptions of multicollinearity were verified using tolerance and variance inflation factors, and the linearity of the continuous variables was verified using the Box-Tidwell transformation. The quality of the models was assessed using the Omnibus Test of Model, R2 Nagelkerke, and Hosmer-Lemeshow tests. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 27). The a priori probability of the type-I error was set at 5%.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic, Occupational and Mental Health Outcomes

Regarding sociodemographic data, women represented 78% (1,545/1,992) of the total participants, men constituted 22% (434/1,992) of the sample, and people who identified as others corresponded to 1% (13/1,992) of the participants. The average age of all participants was 37.1 ± 10.02 years (95% CI = 36.7–37.5). The data revealed that most participants identified themselves as white (74.6%), whereas 19% (374/1,992) identified themselves as brown, 3% as black (67/1,992), 2% as yellow (33/1,992), and 1% (13/1,992). The participants’ marital status ranged from 52% (1,026/1,992) to 41% (821/1,992). In addition, 60% (1,191/1,992) of participants did not have children. Geographically, the Southeast region of Brazil had the highest percentage of participants (59%), followed by the South (20%), Northeast (12%), and North (3%) regions.

Regarding employment data (

Table 1), 63% (1,261/1,992) of the respondents reported earning up to US

$ 1,165 monthly, while 26% (522/1,992) earned US

$ 1,166 or more. The most common positions were veterinary clinic employees (37%), owners of veterinary clinics (28%) and surrogate veterinarians (13%). Among them, 74% (1,472 of 1,992) indicated that they had clinical experience. The majority (58%) had been practicing the profession for up to ten years, whereas 42% (841/1,992) had practiced it for at least 11 years. Regarding workload, nearly half the participants reported working more hours than desired, whereas the remaining 50% expressed satisfaction with their workload or indicated that they worked fewer hours than they preferred. A minority (39%) of participants reported holding a second job. Regarding job satisfaction, 57% (1,126/1,992) of the respondents stated that they would not recommend a career in veterinary medicine and 27% (542/1,992) expressed regret regarding their professional choice.

Table 1.

Work characteristics of veterinary professionals (n = 1992).

Table 1.

Work characteristics of veterinary professionals (n = 1992).

| Variables |

n (%) |

| Monthly income (USD) a

|

|

| Up to 640 |

722 (36.2) |

| 641 – 1165 |

539 (27.1) |

| 1166 – 2330 |

354 (17.8) |

| 2331+ |

168 (8.4) |

| I prefer not to answer |

209 (10.5) |

| Current position |

|

| Employee at a veterinary clinic |

739 (37.1) |

| Owner or co-owner |

558 (28.0) |

| Surrogate veterinary |

252 (12.7) |

| Academic position (professor, researcher, etc.) |

157 (7.9) |

| Non-executive role in the industry |

100 (5.0) |

| Consultant |

93 (4.7) |

| Executive (CEO/Head Administrator) |

61 (3.1) |

| Other |

32 (1.6) |

| Time from graduation (years) |

|

| 0 - 5 |

748 (37.6) |

| 6 -10 |

403 (20.2) |

| 11 - 20 |

515 (25.9) |

| 21+ |

326 (16.4) |

| Current workload |

|

| I’m working more hours than I would like to |

1000 (50.2) |

| I’m working less hours than I would like to |

259 (13.0) |

| I’m satisfied with the number of hours I’m working |

637 (32.0) |

| I prefer not to answer |

96 (4.8) |

| In addition to your regular job, do you have a second job? |

|

| Yes |

772 (38.8) |

| No |

1172 (58.8) |

| I prefer not to answer |

48 (2.4) |

| Would you recommend a veterinary career? |

|

| Yes |

772 (38.8) |

| No |

1172 (58.8) |

| I prefer not to answer |

48 (2.4) |

| Do you regret becoming a veterinarian? |

|

| Yes |

542 (27.2) |

| No |

1368 (68.7) |

| I prefer not to answer |

82 (4.1) |

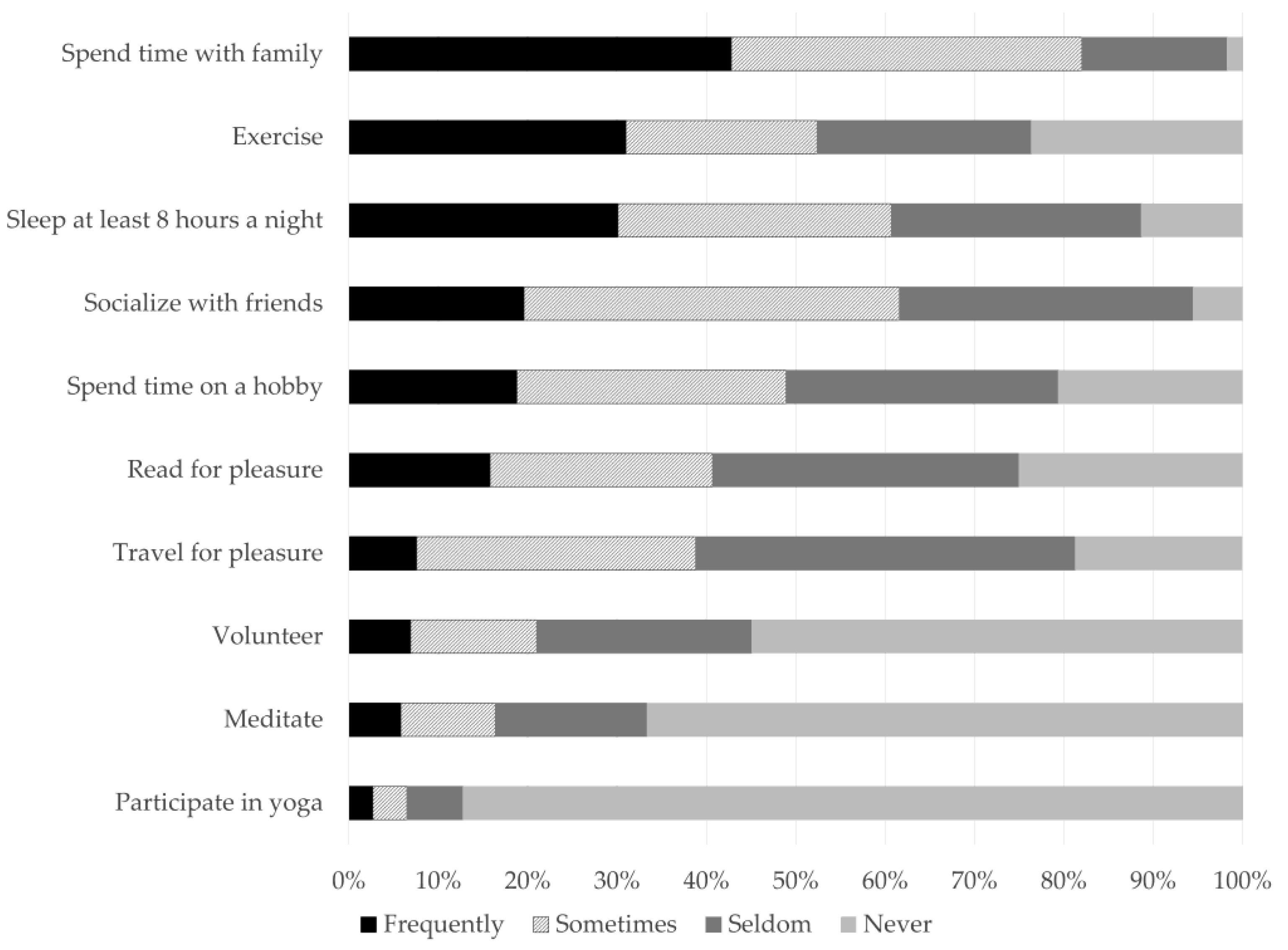

As shown in

Figure 1, participants reported their coping strategies. The most frequent practices were spending time with family (43%), exercising (31%), and sleeping for at least eight hours a night (30%).

Figure 1.

Coping strategies reported by participants (n = 1992).

Figure 1.

Coping strategies reported by participants (n = 1992).

The K6 scale showed an average score of psychological distress of 10.35 (SD = 5.019, 95% CI = 10.13-10.57), with 654 participants (33%) classified as experiencing psychological distress. Concerning PWBI, the average score was 4.23 (SD = 1.85; 95% CI = 4.15-4.31), with 29% (586/1,992) of the participants scoring up to three points, indicating the absence of problems in subjective well-being.

3.2. Sociodemographic and Occupational Factors as Predictors of Mental Health Outcomes

Table 2 presents the results of the multiple logistic regression analysis, which examined the relationship between psychological distress assessed using the K6, subjective well-being assessed using the PWBI, and sociodemographic factors. Ethnicity, macro-region, and profession were not considered in this analysis, as there is no evidence in the literature on the differentiation of well-being and psychological distress according to such variables.

Table 2.

Multiple logistic regression model predicting psychological distress (K6) and well-being (PWBI) using sociodemographic characteristics as independent variables (n = 1992).

Table 2.

Multiple logistic regression model predicting psychological distress (K6) and well-being (PWBI) using sociodemographic characteristics as independent variables (n = 1992).

| Sociodemographic variables |

Psychological distress (K6) |

|

Well-being (PWBI) |

| B |

SE |

OR |

95% CI |

|

B |

SE |

OR |

95% CI |

| Age |

0.01 |

0.01 |

1.00 |

0.98-1.03 |

|

0.03 |

0.01 |

1.03a |

1.01-1.05 |

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Female (ref.) |

- |

- |

1.00 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

| Male |

0.22 |

0.14 |

1.25 |

0.94-1.65 |

|

-0.74 |

0.13 |

0.48b |

0.37-0.62 |

| Marital status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Single (ref.) |

- |

- |

1.00 |

- |

|

- |

- |

1.00 |

- |

| Married |

-0.30 |

0.12 |

0.74a |

0.59-0.94 |

|

1.15 |

1.00 |

1.13 |

0.88-1.52 |

| Separated |

0.38 |

0.24 |

1.46 |

0.92-2.33 |

|

6.40 |

1.00 |

0.86a |

1.16-3.26 |

| Widower |

0.03 |

0.83 |

1.03 |

0.20-5.22 |

|

0.11 |

1.00 |

3.22 |

0.31-5.21 |

| Children |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No (ref.) |

- |

- |

1.00 |

- |

|

- |

- |

1.00 |

- |

| Yes |

0.04 |

0.13 |

1.04 |

0.81-1.33 |

|

-0.11 |

0.13 |

0.90 |

0.69-1.16 |

| Income |

-0.16 |

0.07 |

0.85a |

0.75-0.98 |

|

0.08 |

0.07 |

1.09 |

|

| Time since graduation |

-0.03 |

0.01 |

0.98a |

0.95-0.99 |

|

0.02 |

0.01 |

1.02 |

1-1.05 |

| Which statement better describes your satisfaction with your current workload? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I’m satisfied with the number of hours I work (ref.) |

- |

- |

1.00 |

- |

|

- |

- |

1.00 |

- |

| I’m working less hours than I would like to |

0.23 |

0.16 |

1.26 |

0.92-1.73 |

|

-0.22 |

0.16 |

0.80 |

0.59-1.10 |

| I’m working more hours than I would like to |

0.55 |

0.12 |

1.74b |

1.37-2.21 |

|

-1.17 |

0.13 |

0.31b |

0.24-0.40 |

| Second job? (ref. No) |

-0.02 |

0.11 |

0.98 |

0.80-1.21 |

|

0.26 |

0.12 |

1.30a |

1.03-1.64 |

| Would you recommend a veterinary career? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes (ref.) |

- |

- |

1.00 |

- |

|

- |

- |

1.00 |

- |

| No |

0.61 |

0.13 |

1.84b |

1.44-2.35 |

|

-0.88 |

0.13 |

0.42b |

0.32-0.53 |

| Do you regret becoming a veterinarian? |

- |

- |

1.00 |

- |

|

- |

- |

1.00 |

- |

| No (ref.) |

0.93 |

0.12 |

2.53b |

2.00-3.20 |

|

-0.62 |

0.17 |

0.54b |

0.39-0.74 |

| Yes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Coefficients of the model |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Omnibus Tests - χ2

|

302.97 |

|

|

|

|

468.21 |

|

|

|

| Omnibus Tests (p) |

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

|

| R2 Nagelkerke (p) |

0.196 |

|

|

|

|

0.300 |

|

|

|

| Hosmer and Lemeshow Test (p) |

0.962 |

|

|

|

|

0.386 |

|

|

|

The findings concerning the scale K6 indicate that people of legal age had 3% higher odds of experiencing psychological distress (OR = 1.03, 95% CI = 1.00-1.05), and that for single people, married individuals had 26% lower odds of experiencing psychological distress (OR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.592–0.918), suggesting that being married is a protective factor against psychological distress. This aligns with evidence suggesting that marital relationships often provide emotional support and share responsibilities, which may buffer the effects of occupational stress. Additionally, higher income levels were associated with lower odds of psychological distress rates (OR = 0.85; 95% CI = 0.75–0.98). The analysis also suggested that individuals with fewer years since graduation had 2% lower odds of experiencing psychological distress each additional year since graduation (OR = 0.98; 95% CI = 0.95–0.99).

Participants who reported working more hours presented 74% higher odds of experiencing psychological distress than those who were satisfied with their working hours (OR = 1.74, 95% CI = 1.37-2.21). In addition, professionals who did not recommend a veterinary medicine career (OR = 1.84, 95% CI = 1.42-2.35) and those who regretted having chosen such a profession (OR = 2.53, 95% CI = 2.00-3.20) presented significantly higher levels of psychological distress (84% and 153%, respectively).

As shown in

Table 2, the analysis examined the impact of sociodemographic factors on PWBI scores. Remarkably, participants who reported satisfaction with their current workload had 69% lower odds of reporting poor subjective well-being (OR = 0.31, 95% CI = 0.24-0.40). Other variables, including age, sex, marital status, and second job, also influenced the PWBI. For example, female professionals had more than twice the odds of reporting poor subjective well-being compared with males. This may reflect the cumulative impact of gender-based disparities, such as wage gaps, caregiving roles, and expectations for emotional labor in clinical settings. In addition, those who did not recommend a veterinary career had 58% lower odds of reporting good well-being (OR = 0.42; 95% CI = 0.32-0.53), whereas those who regretted becoming veterinarians had 46% lower odds of reporting good well-being (OR = 0.54; 95% CI = 0.39-0.74).

3.3. Coping Strategies as Predictors of Mental Health Outcomes

Table 3 shows the results of multiple binary logistic regression analysis, indicating how coping strategies are associated with psychological distress and well-being. In general, more frequent involvement in the activities investigated, such as coping strategies, was associated with lower psychological distress and higher overall wellbeing. Comparing the frequency of the activities with K6, the following practices had more influence in the absence of psychological distress, organized from the highest to the lowest influence: traveling for pleasure (OR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.58-0.78), spending time with family (OR = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.60-0.80), sleeping at least eight hours a night (OR = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.72-0.89), spending time with a hobby (OR = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.71-0.92), socializing with friends (OR = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.71-0.95), and practicing volunteer services (OR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.76-0.97).

Table 3.

Multiple logistic regression model predicting psychological distress (K6) and well-being (PWBI) using coping strategies as independent variables (n = 1992).

Table 3.

Multiple logistic regression model predicting psychological distress (K6) and well-being (PWBI) using coping strategies as independent variables (n = 1992).

| Coping strategy |

Psychological distress (K6) |

|

Well-being (PWBI) |

| B |

SE |

OR |

95% CI |

|

B |

SE |

OR |

95% CI |

| Physical exercise |

-0.08 |

0.05 |

0.92 |

0.83-1.02 |

|

0.06 |

0.06 |

1.06 |

0.95-1.19 |

| Yoga practice |

0.18 |

0.10 |

1.20 |

0.99-1.45 |

|

-0.24 |

0.09 |

0.79a

|

0.66-0.94 |

| Socializing with friends |

-0.20 |

0.07 |

0.82a

|

0.71-0.95 |

|

0.23 |

0.08 |

1.26a

|

1.08-1.47 |

| Meditating |

-0.12 |

0.07 |

0.89 |

0.77-1.03 |

|

0.10 |

0.07 |

1.11 |

0.97-1.26 |

| Reading for pleasure |

-0.06 |

0.06 |

0.94 |

0.84-1.06 |

|

0.16 |

0.06 |

1.17a

|

1.04-1.31 |

| Traveling for pleasure |

-0.40 |

0.08 |

0.67b

|

0.58-0.78 |

|

0.31 |

0.08 |

1.36b

|

1.17-1.57 |

| Volunteering in any activity |

-0.15 |

0.06 |

0.86a

|

0.76-0.97 |

|

0.07 |

0.06 |

1.07 |

0.95-1.21 |

| Practicing any hobby |

-0.21 |

0.06 |

0.81b

|

0.71-0.92 |

|

0.21 |

0.07 |

1.23a

|

1.08-1.41 |

| Spending time with family |

-0.37 |

0.07 |

0.69b

|

0.60-0.80 |

|

0.60 |

0.09 |

1.83b

|

1.54-2.18 |

| Sleeping at least 8 hours a night |

-0.22 |

0.06 |

0.80b

|

0.72-0.89 |

|

0.31 |

0.06 |

1.36b

|

1.21-1.53 |

| Coefficients of the model |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Omnibus Tests - χ2

|

|

334.35 |

|

|

|

|

366.20 |

|

| Omnibus Tests (p) |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

| R2 Nagelkerke (p) |

|

0.215 |

|

|

|

|

0.241 |

|

| Hosmer and Lemeshow Test (p) |

|

0.383 |

|

|

|

|

0.282 |

|

By examining the impact of coping strategies on PWBI using multiple logistic regression (

Table 3), seven of the 11 activities remained significant. Traveling for pleasure and sleeping for at least eight hours a day increased the changes in subjective perception of well-being by 136% (OR = 1.36, 95% CI = 1.17-1.57 and OR = -1.36, 95% CI = 1.21-1.53, respectively). Yoga classes negatively influenced well-being (OR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.66-0.94), which is in contrast to other studies [

30,

31].

Although several coping strategies demonstrated statistical significance, it is important to consider their practical implications. For instance, spending time with family (OR = 0.69) and traveling for pleasure (OR = 0.67) were associated with approximately 30–33% lower odds of psychological distress—effects that are not only statistically significant but potentially clinically meaningful. These insights may inform simple, low-cost interventions in wellness programs for veterinary professionals.

4. Discussion

The results of this study revealed a high prevalence of psychological distress among Brazilian veterinarians, with 32.8% of participants scoring high on the K6. These data are consistent with international findings that indicate high levels of psychological distress among veterinary medicine professionals [

23,

34,

35]. Veterinary medicine presents distinct challenges, including euthanasia, dealing with animal suffering, facing ethical and moral dilemmas, managing excessive workloads, and handling pet owners’ emotional demands. These factors can contribute significantly to psychological stress and ultimately affect mental health [

14].

Among the sociodemographic factors analyzed, the females were more vulnerable to psychological distress, presenting worse subjective well-being (PWBI) scores than males. This finding aligns with the existing literature, which identifies women as being more susceptible to psychological distress in veterinary medicine due to structural inequalities, double shifts, and higher exposure to emotionally demanding tasks [

36,

37]. In addition, married individuals presented lower odds of experiencing psychological distress than single individuals, which can be associated with higher social support, a factor already recognized as protective in several occupational contexts [

8,

19].

Lower income levels were related to higher psychological distress indices, indicating that financial stress has a significant impact on mental health in the profession, as also pointed out in previous studies [

22,

23]. Professionals with less time since graduation had higher levels of psychological distress and lower well-being, suggesting that veterinarians starting their careers were particularly more susceptible to emotional difficulties. This finding is in line with previous results [

23], which indicated worsening mental health among younger students and professionals (18-34 years) in veterinary medicine.

Although our findings echo international concerns, there are notable differences. For instance, in North America and Europe, financial debt and professional autonomy are frequently cited as primary stressors [

23]. In contrast, Brazilian veterinarians in this study highlighted work overload and career dissatisfaction as predominant concerns. These distinctions may reflect systemic and cultural differences in veterinary practices, healthcare infrastructure, and social expectations between countries.

One of the most significant findings of this study was the strong association between working hours and psychological distress. This relationship has been widely documented in international studies, which show a connection between excessive workload and high stress levels [

7,

10,

17,

35,

37]. In this study, adverse working conditions were found to be strongly associated with psychological distress.

The data of this study indicate a concerning level of dissatisfaction among veterinary medicine professionals in Brazil, with more than half of the participants (57%) stating that they would not recommend their career and 27% reporting that they regretted their professional choice. Such high indices of dissatisfaction and regret are in line with previous studies, indicating growing disappointment among professionals in this area [

38,

39]. In addition, they reflect similar trends noted in studies conducted in the United States, in which 52% of veterinarians stated that they would not recommend the profession [

14,

22]. These findings reinforce previous findings on dissatisfaction in veterinary careers, often related to work overload, low remuneration, and frustration with the initial expectations of the profession [

7,

10]. The imbalance between professional and personal lives also appears in several studies as one of the main predictors of psychological distress [

5,

40].

Coping strategies have been shown to be a significant protective factor against psychological distress. Activities such as traveling for pleasure, spending time with family (more commonly mentioned practice by the participants), sleeping at least eight hours a night, practicing hobbies, socializing with friends, and conducting volunteer services were significantly associated with reduced psychological distress and improved subjective well-being. These findings support classical theories on coping, and recent evidence indicates that the use of adaptive coping strategies is effective in preventing psychological distress among health professionals [

41,

42].

These results suggest that institutional policies should prioritize work-hour management, especially for early career professionals. Possible interventions include mentorship programs, mental health literacy training, and institutional protocols to ensure adequate rest. Promoting professional networks and peer support groups may be effective alternatives for self-employed professionals. These strategies should be adapted to the varying realities of employment in veterinary medicine.

However, it is worth emphasizing that, despite extensive evidence supporting the benefits of physical activity for reducing psychological distress [

43,

44], this study did not find a significant association between physical exercise and either K6 or PWBI scores. This result contrasts with prevailing findings and suggests that the relationship between physical activity and mental health may vary depending on contextual, occupational, or personal factors within the veterinary profession. These results highlight the importance of conducting studies with more rigorous methodologies—such as randomized clinical trials—not only to establish causal relationships but also to verify whether presumed benefits, such as those from physical activity or yoga, are consistently observed across different populations and contexts.

This study has certain limitations. As a cross-sectional study, this research design precludes the determination of causal relationships among the factors examined. Furthermore, the use of non-probabilistic sampling and reliance on volunteer participation may have introduced a selection bias, potentially favoring the inclusion of individuals with heightened awareness of or interest in mental health, thereby limiting the generalizability of the findings. Future research could benefit from employing mixed methods, including qualitative approaches and longitudinal analyses, to enhance the understanding of the interactions between sociodemographic and occupational factors, and coping strategies in the mental health of veterinary professionals. Additionally, reliance on self-reported data may introduce social desirability bias, potentially leading to the underreporting of negative mental health experiences. Furthermore, potential confounding variables such as personality traits or access to mental health services were not assessed and may have influenced the outcomes. Additionally, all measures were self-reported, which may have introduced recall and social desirability biases. The absence of clinical assessments or objective indicators (e.g., health records and workload metrics) limits the validation of reported symptoms and coping behaviors.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed a high prevalence of psychological distress among Brazilian veterinarians, which was strongly associated with work overload, career dissatisfaction, and low-income status. Protective factors such as adaptive coping behaviors, strong social support networks, and satisfaction with work-life balance were linked to improved well-being. Early-career professionals, women, and those with lower income levels were particularly vulnerable. These findings reinforce the need for mental health support strategies that are sensitive to the specific working conditions of veterinarians. Institutional wellness programs—when applicable—should promote coping strategies that directly address the stressors identified in this population. Based on the study results, actions such as flexible scheduling, planned rest periods, and encouragement of leisure and family time are important for reducing psychological distress. However, a significant portion of the veterinary workforce in Brazil is comprised of self-employed professionals and clinic owners, whose reality differs from institutional employment. For these individuals, relevant strategies may include setting clearer boundaries between personal and professional life, scheduling time off proactively, delegating administrative tasks when possible, and prioritizing restorative practices—such as consistent sleep, hobbies, and time with loved ones. Regardless of work context, coping strategies associated with reduced distress in this study—such as sleeping at least eight hours per night, engaging in leisure travel, and spending time with family—should be encouraged. Future studies should explore not only longitudinal trends but also the effectiveness of tailored interventions across different professional profiles within veterinary medicine. This includes evaluating programs such as structured wellness planning, cognitive-behavioral strategies, and peer-based initiatives. These recommendations must be interpreted in light of the limitations of this study, including the use of non-probabilistic sampling and a cross-sectional design, which restricts causal inference. Longitudinal and interventional designs are required to validate and refine the strategies proposed in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S.G., J.L.P. and A.R.S.S.; methodology, B.S.G., J.L.P. and A.R.S.S.; software, J.L.P.; validation, A.S.R.; formal analysis, B.S.G. and J.L.P.; investigation, B.S.G., H.C.L., S.M.V.U. and A.R.S.S; resources, B.S.G. and J.L.P.; data curation, B.S.G. and J.L.P.; writing—original draft preparation, B.S.G. and J.L.P.; writing—review and editing, A.S.R., H.C.L., S.M.V.U. and A.R.S.S.; visualization, A.S.R., H.C.L., S.M.V.U. and A.R.S.S.; supervision, B.S.G., J.L.P. and A.R.S.S.; project administration, B.S.G.; funding acquisition, B.S.G. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Brazil (MSD Brazil)

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Faculdade Inspirar, a committee accredited by the Brazilian National Research Ethics Commission (Comissão Nacional de Ética em Pesquisa – CONEP), under protocol number 31645220.4.0000.5594, approved on 29 June 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions of this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely appreciate the support of the MSD Brasil staff throughout various stages of article production, including data collection, translation, and funding. Special thanks go to Daniela Baccarin and Delair Angelo Bolis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Peixoto, M.M. Suicide risk in veterinary professionals in Portugal: Prevalence of psychological symptoms, burnout, and compassion fatigue. Arch. Suicide Res. 2024, 29, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, M.F.; Kho, M.; Thomas, E.F.; Decety, J.; Molenberghs, P.; Amiot, C.E.; Lizzio-Wilson, M.; Wibisono, S.; Allan, F.; Louis, W. The moderating role of different forms of empathy on the association between performing animal euthanasia and career sustainability. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 53, 1088–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira Bergamini, S.; Uccheddu, S.; Riggio, G.; de Jesus Vilela, M.R.; Mariti, C. The emotional impact of patient loss on brazilian veterinarians. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knesl, O.; Hart, B.L.; Fine, A.H.; Cooper, L.; Patterson-Kane, E.; Houlihan, K.E.; Anthony, R. Veterinarians and humane endings: When is it the right time to euthanize a companion animal? Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, J.O.; Schimmack, U.; Strand, E.B.; Reinhard, A.; Hahn, J.; Andrews, J.; Probyn-Smith, K.; Jones, R. Work-life balance is essential to reducing burnout, improving well-being. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volk, J.O.; Schimmack, U.; Strand, E.B.; Reinhard, A.; Vasconcelos, J.; Hahn, J.; Stiefelmeyer, K.; Probyn-Smith, K. Executive summary of the Merck animal health veterinarian wellbeing study III and veterinary support staff study. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, W.; Lockett, L.; Colville, T.; Uldahl, M.; De Briyne, N. Veterinarian—Chasing a dream job? A comparative survey on wellbeing and stress levels among European veterinarians between 2018 and 2023. Veterinary Sciences 2024, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, F.; Houdmont, J.; Hill, B.; Pickles, K. Mental wellbeing and psychosocial working conditions of autistic veterinary surgeons in the UK. Vet Rec 2023, 193, e3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, D.J.; Kerl, M.E.; Tsai, C.-L. Factors associated with job satisfaction and engagement among credentialed small animal veterinary technicians in the United States. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2020, 257, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, P.; Mills, P.; Doneley, B. Relieving veterinarians’ workloads and stress: leveraging Australia’s veterinary technologists and nurses. Aust. Vet. J. 2023, 101, 409–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, C.O.; Perret, J.L.; Hewson, J.; Khosa, D.K.; Conlon, P.D.; Jones-Bitton, A. A survey of veterinarian mental health and resilience in Ontario, Canada. The Canadian Veterinary Journal 2020, 61, 166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wouk, A.F.P.; Martins, C.M.; Mondadori, R.G.; Pacheco, M.H. de S.; Molina, T.G., Silveira, M.B.G. da, Eds.; Ferreira, F. Demographics of veterinary medicine in Brazil 2022; Editora Guará: Cotia, SP, 2023; ISBN 978-85-87925-04-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bilodeau, J.; Marchand, A.; Demers, A. Psychological distress inequality between employed men and women: A gendered exposure model. SSM - Population Health 2020, 11, 100626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffey, M.A.; Griffon, D.J.; Risselada, M.; Buote, N.J.; Scharf, V.F.; Zamprogno, H.; Winter, A.L. A narrative review of the physiology and health effects of burnout associated with veterinarian-pertinent occupational stressors. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedhammer, I.; Bertrais, S.; Witt, K. Psychosocial work exposures and health outcomes: a meta-review of 72 literature reviews with meta-analysis. Scand J Work Environ Health 2021, 47, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, J.; Pfeffer, J.; Zenios, S.A. The relationship between workplace stressors and mortality and health costs in the United States. Management Science 2016, 62, 608–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, R.; Botscharow, J.; Böckelmann, I.; Thielmann, B. Stress and strain among veterinarians: a scoping review. Ir Vet J 2022, 75, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, V.; Dale, R.; Probst, T.; Pieh, C.; Janowitz, K.; Brühl, D.; Humer, E. Prevalence of mental health symptoms in Austrian veterinarians and examination of influencing factors. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 13274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: New York, 1984; ISBN 978-0-8261-4192-7. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi, S.E.; Fechter-Leggett, E.D.; Edwards, N.T.; Reddish, A.D.; Crosby, A.E.; Nett, R.J. Suicide among veterinarians in the United States from 1979 through 2015. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2019, 254, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetina, B.U.; Krouzecky, C. Reviewing a decade of change for veterinarians: past, present and gaps in researching stress, coping and mental health risks. Animals 2022, 12, 3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, J.O.; Schimmack, U.; Strand, E.B.; Lord, L.K.; Siren, C.W. Executive summary of the Merck animal health veterinary wellbeing study. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018, 252, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, J.O.; Schimmack, U.; Strand, E.B.; Reinhard, A.; Vasconcelos, J.; Hahn, J.; Stiefelmeyer, K.; Probyn-Smith, K. Executive summary of the Merck animal health veterinarian wellbeing study III and veterinary support staff study. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2022, 260, 1547–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettle, V.E.; Madigan, C.D.; Coombe, A.; Graham, H.; Thomas, J.J.C.; Chalkley, A.E.; Daley, A.J. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions delivered or prompted by health professionals in primary care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2022, 376, e068465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.T.; Barcelos, A.M.; Mills, D.S. Links between pet ownership and exercise on the mental health of veterinary professionals. Vet Rec Open 2023, 10, e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc: Los Angeles, 2017; ISBN 978-1-5063-4156-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Barker, P.R.; Colpe, L.J.; Epstein, J.F.; Gfroerer, J.C.; Hiripi, E.; Howes, M.J.; Normand, S.-L.T.; Manderscheid, R.W.; Walters, E.E.; et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry 2003, 60, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzeguini, M.V.; Corassa, R.B.; Wang, Y.-P.; Andrade, L.H.; Sarti, T.D.; Viana, M.C. The performance of K6 as a screening tool for mood disorders: A population-based study of the São Paulo metropolitan area. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 2024, 18, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Szydlo, D.W.; Downing, S.M.; Sloan, J.A.; Shanafelt, T.D. Development and preliminary psychometric properties of a well-being index for medical students. BMC Med Educ 2010, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mocanu, E.; Mohr, C.; Pouyan, N.; Thuillard, S.; Dan-Glauser, E.S. Reasons, years and frequency of yoga practice: effect on emotion response reactivity. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohel, M.K.; Phatak, A.G.; Kharod, U.N.; Pandya, B.A.; Prajapati, B.L.; Shah, U.M. Effect of long-term regular yoga on physical health of yoga practitioners. Indian J Community Med 2021, 46, 508–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levante, A.; Quarta, S.; Massaro, M.; Calabriso, N.; Carluccio, M.A.; Damiano, F.; Pollice, F.; Siculella, L.; Lecciso, F. Physical activity habits prevent psychological distress in female academic students: The multiple mediating role of physical and psychosocial parameters. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bore, M.; Kelly, B.; Nair, B. Potential predictors of psychological distress and well-being in medical students: a cross-sectional pilot study. AMEP 2016, 7, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brscic, M.; Contiero, B.; Schianchi, A.; Marogna, C. Challenging suicide, burnout, and depression among veterinary practitioners and students: text mining and topics modelling analysis of the scientific literature. BMC Vet Res 2021, 17, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andela, M. Burnout, somatic complaints, and suicidal ideations among veterinarians: development and validation of the veterinarians stressors inventory. Journal of Veterinary Behavior 2020, 37, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, A. Burnout, compassion fatigue and moral distress in veterinary professionals. The Veterinary Nurse 2023, 14, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spendelow, J.; Cripwell, C.; Stott, R.; Francis, K.; Powell, J.; Cavanagh, K.; Corbett, R. Workplace stressor factors, profiles and the relationship to career stage in UK veterinarians, veterinary nurses and students. Veterinary Medicine and Science 2024, 10, e1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivian, S.R.; Holt, S.L.; Williams, J. What factors influence the perceptions of job satisfaction in registered veterinary nurses currently working in veterinary practice in the United Kingdom? J Am Vet Med Assoc 2022, 49, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbe Montoya, A.I.; Hazel, S.J.; Matthew, S.M.; McArthur, M.L. Why do veterinarians leave clinical practice? A qualitative study using thematic analysis. Vet Rec 2021, 188, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, K.; Burke, K.; Signal, T. Mental health in the veterinary profession: an individual or organisational focus? Aust. Vet. J. 2023, 101, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, C.E.; Norris, K.; Dawkins, S.; Martin, A. Barriers to mental health help-seeking in veterinary professionals working in Australia and New Zealand: A preliminary cross-sectional analysis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; Hagen, B.N.M.; Gohar, B.; Wichtel, J.; Jones-Bitton, A. A qualitative study exploring the perceived effects of veterinarians’ mental health on provision of care. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emikpe, B.O.; Asare, D.A.; Emikpe, A.O.; Botchway, L.A.N.; Bonney, R.A. Prevalence and associated risk factors of burnout amongst veterinary students in Ghana. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0271434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, F.; Van den Brink, A. Current insights in veterinarians’ psychological wellbeing. N. Z. Vet. J. 2020, 68, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).