Submitted:

28 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

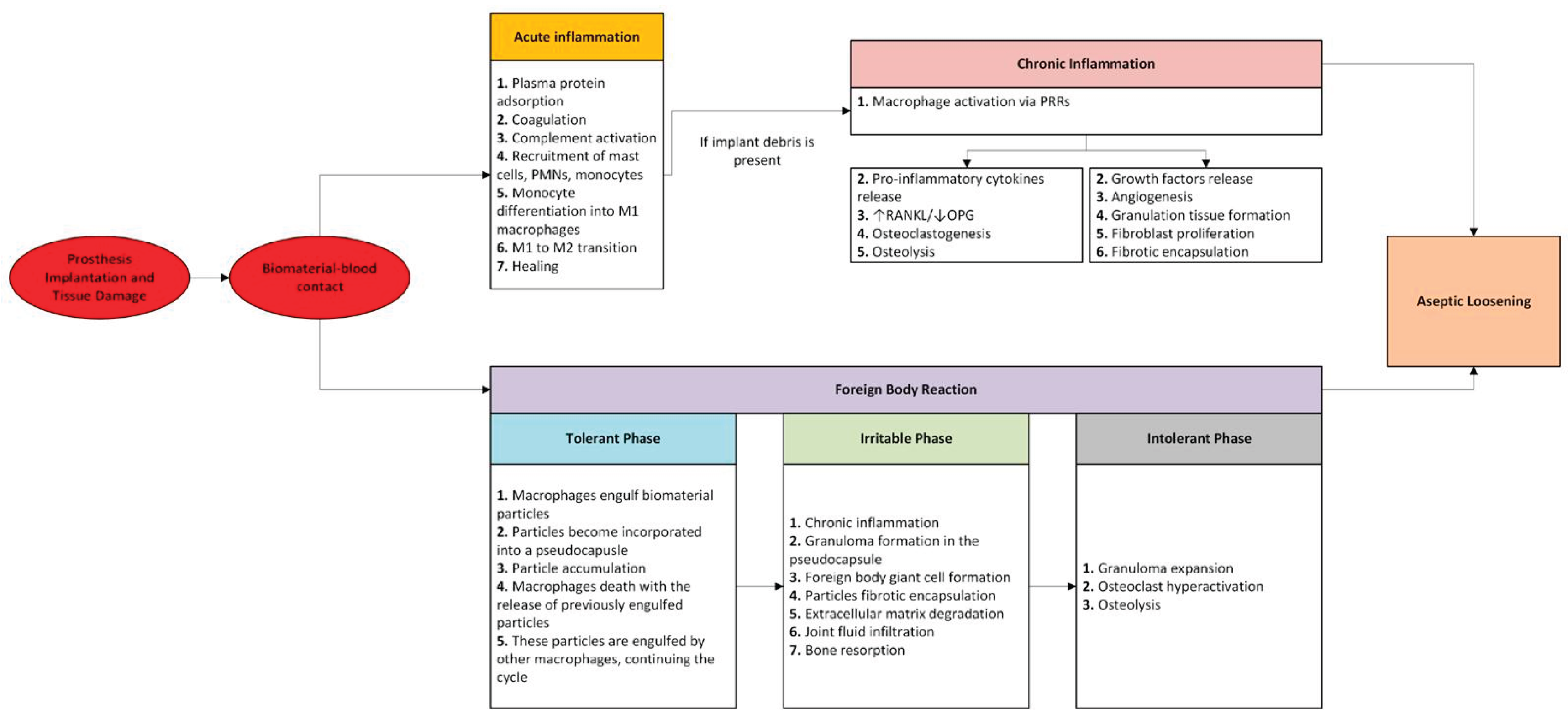

1. Biology of Aseptic Loosening

1.1. Immune Response to Biomaterials

1.1.1. Acute Inflammation

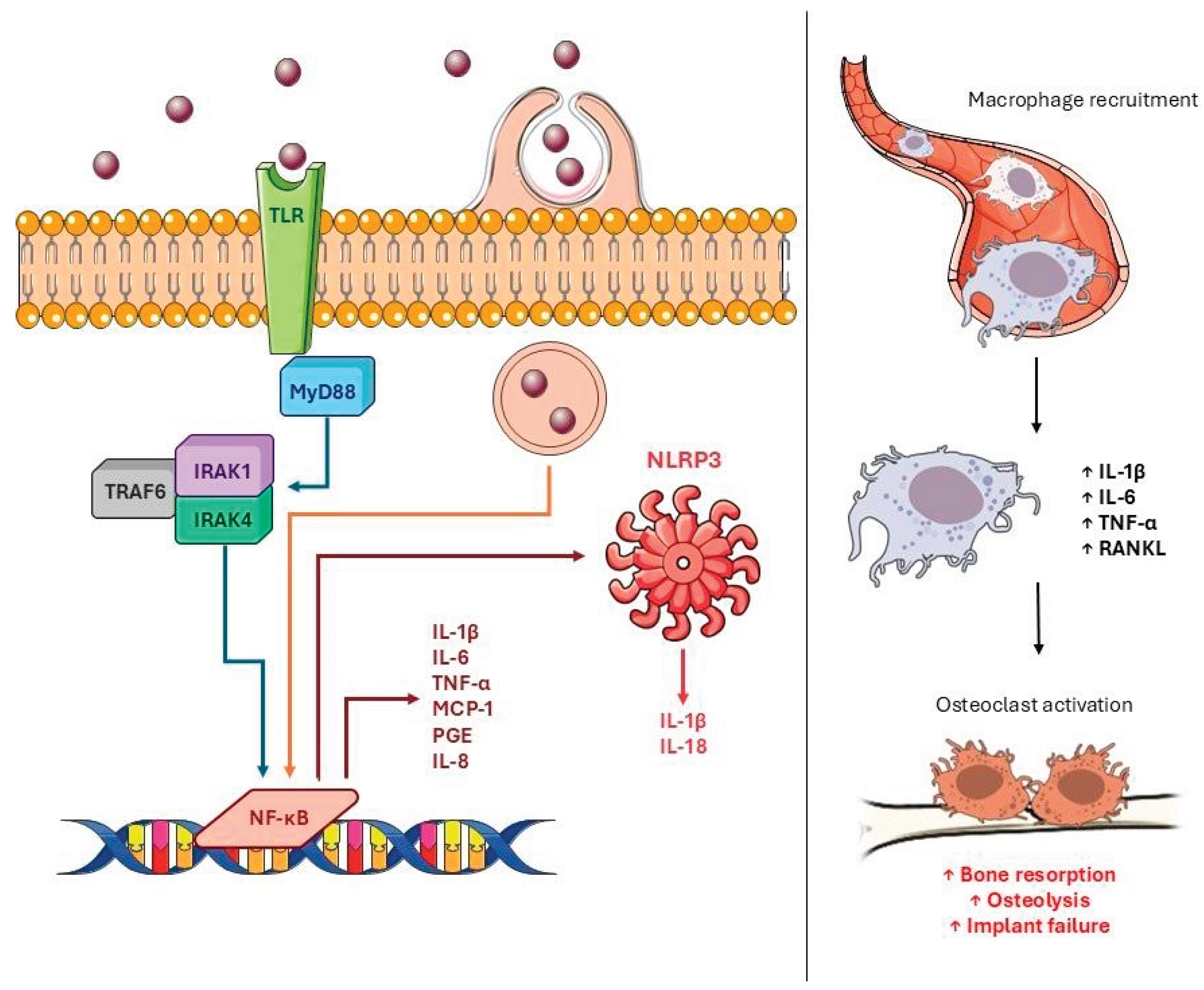

1.1.2. Chronic Inflammation

1.1.3. Granulation Tissue and Fibrosis

1.1.4. Foreign Body Reaction

1.2. Inflammatory Response to Different Implant Materials

1.2.1. Polyethylene Wear Particles

1.2.2. Polymethylmethacrylate Wear Particles

1.2.3. Metallic Wear Debris

1.2.3. Ceramic Wear Debris

2. Biomarkers

Prevention and Treatment of Aseptic Loosening

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AL | Aseptic loosening; |

| FXII | Factor XII; |

| TF | tissue factor; |

| IL | interleukin; |

| MCP-1/CCL2 | monocyte chemotactic protein-1/Chemokine CC motif ligand 2; |

| MIP-1 | macrophage inflammatory protein-1; |

| PMN | polymorphonuclear leukocyte; |

| FBR | foreign body reaction; |

| MSC | mesenchymal stem cell; |

| PPOL | periprosthetic osteolysis; |

| FBGC | foreign body giant cell; |

| PRR | pattern recognition receptor; |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor; |

| PGE | prostaglandin E; |

| RANKL | receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand; |

| MIP-1α | macrophage inflammatory protein-1α; |

| TLR | Toll-like receptors; |

| OPG | osteoprotegerin; |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase; |

| PDGF | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor; |

| FGF | Fibroblast Growth Factor; |

| TGF | Transforming Growth Factor; |

| EGF | Epidermal Growth Factor; |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species; |

| PE | polyethylene; |

| UHMWPE | ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene; |

| XLPE | cross-linked polyethylene; |

| PMMA | Polymethylmethacrylate; |

| ARMD | adverse reactions to metal debris; |

References

- C. Li, S. C. Li, S. Schmid, J. Mason, Effects of pre-cooling and pre-heating procedures on cement polymerization and thermal osteonecrosis in cemented hip replacements, Medical Engineering & Physics 25 (2003) 559–564. [CrossRef]

- P.F. Sharkey, P.M. P.F. Sharkey, P.M. Lichstein, C. Shen, A.T. Tokarski, J. Parvizi, Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today--has anything changed after 10 years?, J Arthroplasty 29 (2014) 1774–1778. [CrossRef]

- K. Thiele, C. K. Thiele, C. Perka, G. Matziolis, H.O. Mayr, M. Sostheim, R. Hube, Current failure mechanisms after knee arthroplasty have changed: polyethylene wear is less common in revision surgery, J Bone Joint Surg Am 97 (2015) 715–720. [CrossRef]

- T.J.M. van Otten, C.J.M. T.J.M. van Otten, C.J.M. van Loon, Early aseptic loosening of the tibial component at the cement-implant interface in total knee arthroplasty: a narrative overview of potentially associated factors, Acta Orthop Belg 88 (2022) 103–111. [CrossRef]

- Z. Yao, T.-H. Z. Yao, T.-H. Lin, J. Pajarinen, T. Sato, S. Goodman, Chapter 12 - Host Response to Orthopedic Implants (Metals and Plastics), in: S.F. Badylak (Ed.), Host Response to Biomaterials, Academic Press, Oxford, 2015: pp. 315–373. [CrossRef]

- E. Gibon, Y. E. Gibon, Y. Takakubo, S. Zwingenberger, J. Gallo, M. Takagi, S.B. Goodman, Friend or foe? Inflammation and the foreign body response to orthopedic biomaterials, J Biomed Mater Res A 112 (2024) 1172–1187. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cong, Y. Y. Cong, Y. Wang, T. Yuan, Z. Zhang, J. Ge, Q. Meng, Z. Li, S. Sun, Macrophages in aseptic loosening: Characteristics, functions, and mechanisms, Front Immunol 14 (2023) 1122057. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Anderson, A. J.M. Anderson, A. Rodriguez, D.T. Chang, FOREIGN BODY REACTION TO BIOMATERIALS, Semin Immunol 20 (2008) 86–100. [CrossRef]

- C.J. Wilson, R.E. C.J. Wilson, R.E. Clegg, D.I. Leavesley, M.J. Pearcy, Mediation of biomaterial-cell interactions by adsorbed proteins: a review, Tissue Eng 11 (2005) 1–18. [CrossRef]

- J. Andersson, K.N. J. Andersson, K.N. Ekdahl, R. Larsson, U.R. Nilsson, B. Nilsson, C3 adsorbed to a polymer surface can form an initiating alternative pathway convertase, J Immunol 168 (2002) 5786–5791. [CrossRef]

- C. Sperling, M. C. Sperling, M. Fischer, M.F. Maitz, C. Werner, Blood coagulation on biomaterials requires the combination of distinct activation processes, Biomaterials 30 (2009) 4447–4456. [CrossRef]

- M. Fischer, C. M. Fischer, C. Sperling, C. Werner, Synergistic effect of hydrophobic and anionic surface groups triggers blood coagulation in vitro, J Mater Sci Mater Med 21 (2010) 931–937. [CrossRef]

- W.J. Hu, J.W. W.J. Hu, J.W. Eaton, T.P. Ugarova, L. Tang, Molecular basis of biomaterial-mediated foreign body reactions, Blood 98 (2001) 1231–1238. [CrossRef]

- M. Fischer, C. M. Fischer, C. Sperling, P. Tengvall, C. Werner, The ability of surface characteristics of materials to trigger leukocyte tissue factor expression, Biomaterials 31 (2010) 2498–2507. [CrossRef]

- P.M. Henson, R.B. P.M. Henson, R.B. Johnston, Tissue injury in inflammation. Oxidants, proteinases, and cationic proteins, J Clin Invest 79 (1987) 669–674. [CrossRef]

- R.I. Lehrer, T. R.I. Lehrer, T. Ganz, M.E. Selsted, B.M. Babior, J.T. Curnutte, Neutrophils and host defense, Ann Intern Med 109 (1988) 127–142. [CrossRef]

- H.L. Malech, J.I. H.L. Malech, J.I. Gallin, Current concepts: immunology. Neutrophils in human diseases, N Engl J Med 317 (1987) 687–694. [CrossRef]

- R.O. Hynes, Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines, Cell 110 (2002) 673–687. [CrossRef]

- C.A. Lowell, G. C.A. Lowell, G. Berton, Integrin signal transduction in myeloid leukocytes, J Leukoc Biol 65 (1999) 313–320. [CrossRef]

- A.K. McNally, J.M. A.K. McNally, J.M. Anderson, Complement C3 participation in monocyte adhesion to different surfaces., Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91 (1994) 10119–10123.

- L. Tang, Mechanisms of fibrinogen domains: biomaterial interactions, J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 9 (1998) 1257–1266. [CrossRef]

- J. Zdolsek, J.W. J. Zdolsek, J.W. Eaton, L. Tang, Histamine release and fibrinogen adsorption mediate acute inflammatory responses to biomaterial implants in humans, J Transl Med 5 (2007) 31. [CrossRef]

- P. Scapini, J.A. P. Scapini, J.A. Lapinet-Vera, S. Gasperini, F. Calzetti, F. Bazzoni, M.A. Cassatella, The neutrophil as a cellular source of chemokines, Immunol Rev 177 (2000) 195–203. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hidaka, M. Y. Hidaka, M. Ito, K. Mori, H. Yagasaki, A.H. Kafrawy, Histopathological and immunohistochemical studies of membranes of deacetylated chitin derivatives implanted over rat calvaria, J Biomed Mater Res 46 (1999) 418–423. [CrossRef]

- P.J. VandeVord, H.W.T. P.J. VandeVord, H.W.T. Matthew, S.P. DeSilva, L. Mayton, B. Wu, P.H. Wooley, Evaluation of the biocompatibility of a chitosan scaffold in mice, J Biomed Mater Res 59 (2002) 585–590. [CrossRef]

- C.J. Park, N.P. C.J. Park, N.P. Gabrielson, D.W. Pack, R.D. Jamison, A.J. Wagoner Johnson, The effect of chitosan on the migration of neutrophil-like HL60 cells, mediated by IL-8, Biomaterials 30 (2009) 436–444. [CrossRef]

- S.D. Kobayashi, J.M. S.D. Kobayashi, J.M. Voyich, C. Burlak, F.R. DeLeo, Neutrophils in the innate immune response, Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 53 (2005) 505–517.

- S. Yamashiro, H. S. Yamashiro, H. Kamohara, J.M. Wang, D. Yang, W.H. Gong, T. Yoshimura, Phenotypic and functional change of cytokine-activated neutrophils: inflammatory neutrophils are heterogeneous and enhance adaptive immune responses, J Leukoc Biol 69 (2001) 698–704.

- D.W. Gilroy, T. D.W. Gilroy, T. Lawrence, M. Perretti, A.G. Rossi, Inflammatory resolution: new opportunities for drug discovery, Nat Rev Drug Discov 3 (2004) 401–416. [CrossRef]

- C. Schlundt, T. C. Schlundt, T. El Khassawna, A. Serra, A. Dienelt, S. Wendler, H. Schell, N. van Rooijen, A. Radbruch, R. Lucius, S. Hartmann, G.N. Duda, K. Schmidt-Bleek, Macrophages in bone fracture healing: Their essential role in endochondral ossification, Bone 106 (2018) 78–89. [CrossRef]

- S.B. Goodman, E. S.B. Goodman, E. Gibon, J. Gallo, M. Takagi, Macrophage Polarization and the Osteoimmunology of Periprosthetic Osteolysis, Curr Osteoporos Rep 20 (2022) 43–52. [CrossRef]

- P.J. Murray, Macrophage Polarization, Annu Rev Physiol 79 (2017) 541–566. [CrossRef]

- T. Kon, T.J. T. Kon, T.J. Cho, T. Aizawa, M. Yamazaki, N. Nooh, D. Graves, L.C. Gerstenfeld, T.A. Einhorn, Expression of osteoprotegerin, receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand (osteoprotegerin ligand) and related proinflammatory cytokines during fracture healing, J Bone Miner Res 16 (2001) 1004–1014. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xing, C. Z. Xing, C. Lu, D. Hu, Y. Yu, X. Wang, C. Colnot, M. Nakamura, Y. Wu, T. Miclau, R.S. Marcucio, Multiple roles for CCR2 during fracture healing, Dis Model Mech 3 (2010) 451–458. [CrossRef]

- L.C. Gerstenfeld, D.M. L.C. Gerstenfeld, D.M. Cullinane, G.L. Barnes, D.T. Graves, T.A. Einhorn, Fracture healing as a post-natal developmental process: molecular, spatial, and temporal aspects of its regulation, J Cell Biochem 88 (2003) 873–884. [CrossRef]

- P. Kolar, K. P. Kolar, K. Schmidt-Bleek, H. Schell, T. Gaber, D. Toben, G. Schmidmaier, C. Perka, F. Buttgereit, G.N. Duda, The early fracture hematoma and its potential role in fracture healing, Tissue Eng Part B Rev 16 (2010) 427–434. [CrossRef]

- E.-J. Lee, M. E.-J. Lee, M. Jain, S. Alimperti, Bone Microvasculature: Stimulus for Tissue Function and Regeneration, Tissue Eng Part B Rev 27 (2021) 313–329. [CrossRef]

- F. Loi, L.A. F. Loi, L.A. Córdova, J. Pajarinen, T. Lin, Z. Yao, S.B. Goodman, Inflammation, fracture and bone repair, Bone 86 (2016) 119–130. [CrossRef]

- M.E. Kotas, R. M.E. Kotas, R. Medzhitov, Homeostasis, inflammation, and disease susceptibility, Cell 160 (2015) 816–827. [CrossRef]

- C. Kasikara, A.C. C. Kasikara, A.C. Doran, B. Cai, I. Tabas, The role of non-resolving inflammation in atherosclerosis, J Clin Invest 128 (2018) 2713–2723. [CrossRef]

- C. Nathan, A. C. Nathan, A. Ding, Nonresolving inflammation, Cell 140 (2010) 871–882. [CrossRef]

- Pezone, F. Olivieri, M.V. Napoli, A. Procopio, E.V. Avvedimento, A. Gabrielli, Inflammation and DNA damage: cause, effect or both, Nat Rev Rheumatol 19 (2023) 200–211. [CrossRef]

- M. Couto, D.P. M. Couto, D.P. Vasconcelos, D.M. Sousa, B. Sousa, F. Conceição, E. Neto, M. Lamghari, C.J. Alves, The Mechanisms Underlying the Biological Response to Wear Debris in Periprosthetic Inflammation, Front. Mater. 7 (2020). [CrossRef]

- T.R. Green, J. T.R. Green, J. Fisher, M. Stone, B.M. Wroblewski, E. Ingham, Polyethylene particles of a ‘critical size’ are necessary for the induction of cytokines by macrophages in vitro, Biomaterials 19 (1998) 2297–2302. [CrossRef]

- T.R. Green, J. T.R. Green, J. Fisher, J.B. Matthews, M.H. Stone, E. Ingham, Effect of size and dose on bone resorption activity of macrophages by in vitro clinically relevant ultra high molecular weight polyethylene particles, J Biomed Mater Res 53 (2000) 490–497. [CrossRef]

- S.B. Goodman, J. S.B. Goodman, J. Gallo, Periprosthetic Osteolysis: Mechanisms, Prevention and Treatment, J Clin Med 8 (2019) 2091. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A. Essner, C. Stark, J.H. Dumbleton, Comparison of the size and morphology of UHMWPE wear debris produced by a hip joint simulator under serum and water lubricated conditions, Biomaterials 17 (1996) 865–871. [CrossRef]

- N.J. Hallab, K. N.J. Hallab, K. McAllister, M. Brady, M. Jarman-Smith, Macrophage reactivity to different polymers demonstrates particle size- and material-specific reactivity: PEEK-OPTIMA(®) particles versus UHMWPE particles in the submicron, micron, and 10 micron size ranges, J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 100 (2012) 480–492. [CrossRef]

- E. Ingham, J. E. Ingham, J. Fisher, The role of macrophages in osteolysis of total joint replacement, Biomaterials 26 (2005) 1271–1286. [CrossRef]

- R. Chiu, T. R. Chiu, T. Ma, R.L. Smith, S.B. Goodman, Ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene wear debris inhibits osteoprogenitor proliferation and differentiation in vitro, J Biomed Mater Res A 89 (2009) 242–247. [CrossRef]

- C. Nich, Y. C. Nich, Y. Takakubo, J. Pajarinen, M. Ainola, A. Salem, T. Sillat, A.J. Rao, M. Raska, Y. Tamaki, M. Takagi, Y.T. Konttinen, S.B. Goodman, J. Gallo, Macrophages-Key cells in the response to wear debris from joint replacements, J Biomed Mater Res A 101 (2013) 3033–3045. [CrossRef]

- N.A. Athanasou, The pathobiology and pathology of aseptic implant failure, Bone Joint Res 5 (2016) 162–168. [CrossRef]

- Q. Gu, Q. Q. Gu, Q. Shi, H. Yang, The role of TLR and chemokine in wear particle-induced aseptic loosening, J Biomed Biotechnol 2012 (2012) 596870. [CrossRef]

- S. Landgraeber, M. S. Landgraeber, M. Jäger, J.J. Jacobs, N.J. Hallab, The pathology of orthopedic implant failure is mediated by innate immune system cytokines, Mediators Inflamm 2014 (2014) 185150. [CrossRef]

- K. Schroder, J. K. Schroder, J. Tschopp, The inflammasomes, Cell 140 (2010) 821–832. [CrossRef]

- T. Shiratori, Y. T. Shiratori, Y. Kyumoto-Nakamura, A. Kukita, N. Uehara, J. Zhang, K. Koda, M. Kamiya, T. Badawy, E. Tomoda, X. Xu, T. Yamaza, Y. Urano, K. Koyano, T. Kukita, IL-1β Induces Pathologically Activated Osteoclasts Bearing Extremely High Levels of Resorbing Activity: A Possible Pathological Subpopulation of Osteoclasts, Accompanied by Suppressed Expression of Kindlin-3 and Talin-1, J Immunol 200 (2018) 218–228. [CrossRef]

- T. Lin, Y. T. Lin, Y. Tamaki, J. Pajarinen, H.A. Waters, D.K. Woo, Z. Yao, S.B. Goodman, Chronic inflammation in biomaterial induced periprosthetic osteolysis: NF-κB as a therapeutic target, Acta Biomater 10 (2014) 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.09.034. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Kandahari, X. A.M. Kandahari, X. Yang, K.A. Laroche, A.S. Dighe, D. Pan, Q. Cui, A review of UHMWPE wear-induced osteolysis: the role for early detection of the immune response, Bone Res 4 (2016) 1–13. [CrossRef]

- E. Sukur, Y.E. E. Sukur, Y.E. Akman, Y. Ozturkmen, F. Kucukdurmaz, Particle Disease: A Current Review of the Biological Mechanisms in Periprosthetic Osteolysis After Hip Arthroplasty, Open Orthop J 10 (2016) 241–251. [CrossRef]

- P.E. Purdue, P. P.E. Purdue, P. Koulouvaris, H.G. Potter, B.J. Nestor, T.P. Sculco, The cellular and molecular biology of periprosthetic osteolysis, Clin Orthop Relat Res 454 (2007) 251–261. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Anderson, Chapter II.2.2 - Inflammation, Wound Healing, and the Foreign-Body Response, in: B.D. Ratner, A.S. Hoffman, F.J. Schoen, J.E. Lemons (Eds.), Biomaterials Science (Third Edition), Academic Press, 2013: pp. 503–512. [CrossRef]

- M. Takagi, Neutral proteinases and their inhibitors in the loosening of total hip prostheses, Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 271 (1996) 3–29.

- F. Yang, W. F. Yang, W. Wu, L. Cao, Y. Huang, Z. Zhu, T. Tang, K. Dai, Pathways of macrophage apoptosis within the interface membrane in aseptic loosening of prostheses, Biomaterials 32 (2011) 9159–9167. [CrossRef]

- F. Renò, M. F. Renò, M. Sabbatini, A. Massè, M. Bosetti, M. Cannas, Fibroblast apoptosis and caspase-8 activation in aseptic loosening, Biomaterials 24 (2003) 3941–3946. [CrossRef]

- S. Santavirta, Y.T. S. Santavirta, Y.T. Konttinen, V. Bergroth, A. Eskola, K. Tallroth, T.S. Lindholm, Aggressive granulomatous lesions associated with hip arthroplasty. Immunopathological studies, J Bone Joint Surg Am 72 (1990) 252–258.

- S.A. Solovieva, A. S.A. Solovieva, A. Ceponis, Y.T. Konttinen, M. Takagi, A. Suda, K.K. Eklund, T. Sorsa, S. Santavirta, Mast cells in loosening of totally replaced hips, Clin Orthop Relat Res (1996) 158–165.

- Z. Sheikh, P.J. Z. Sheikh, P.J. Brooks, O. Barzilay, N. Fine, M. Glogauer, Macrophages, Foreign Body Giant Cells and Their Response to Implantable Biomaterials, Materials (Basel) 8 (2015) 5671–5701. [CrossRef]

- Y.-C. Lu, T.-K. Y.-C. Lu, T.-K. Chang, T.-C. Lin, S.-T. Yeh, H.-W. Fang, C.-H. Huang, C.-H. Huang, The potential role of herbal extract Wedelolactone for treating particle-induced osteolysis: an in vivo study, J Orthop Surg Res 17 (2022) 335. [CrossRef]

- P. Aspenberg, A. P. Aspenberg, A. Anttila, Y.T. Konttinen, R. Lappalainen, S.B. Goodman, L. Nordsletten, S. Santavirta, Benign response to particles of diamond and SiC: bone chamber studies of new joint replacement coating materials in rabbits, Biomaterials 17 (1996) 807–812. [CrossRef]

- T.P. Schmalzried, M. T.P. Schmalzried, M. Jasty, W.H. Harris, Periprosthetic bone loss in total hip arthroplasty. Polyethylene wear debris and the concept of the effective joint space, J Bone Joint Surg Am 74 (1992) 849–863.

- M.T. Manley, J.A. M.T. Manley, J.A. D’Antonio, W.N. Capello, A.A. Edidin, Osteolysis: a disease of access to fixation interfaces, Clin Orthop Relat Res (2002) 129–137. [CrossRef]

- G. Pap, A. G. Pap, A. Machner, T. Rinnert, D. Hörler, R.E. Gay, H. Schwarzberg, W. Neumann, B.A. Michel, S. Gay, T. Pap, Development and characteristics of a synovial-like interface membrane around cemented tibial hemiarthroplasties in a novel rat model of aseptic prosthesis loosening, Arthritis Rheum 44 (2001) 956–963. [CrossRef]

- S. Banerjee, R. S. Banerjee, R. Pivec, K. Issa, B.H. Kapadia, H.S. Khanuja, M.A. Mont, Large-diameter femoral heads in total hip arthroplasty: an evidence-based review, Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 43 (2014) 506–512.

- P.C. Oparaugo, I.C. P.C. Oparaugo, I.C. Clarke, H. Malchau, P. Herberts, Correlation of wear debris-induced osteolysis and revision with volumetric wear-rates of polyethylene: a survey of 8 reports in the literature, Acta Orthop Scand 72 (2001) 22–28. [CrossRef]

- J. Shi, W. J. Shi, W. Zhu, S. Liang, H. Li, S. Li, Cross-Linked Versus Conventional Polyethylene for Long-Term Clinical Outcomes After Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, J Invest Surg 34 (2021) 307–317. [CrossRef]

- B. Lambert, D. B. Lambert, D. Neut, H.C. van der Veen, S.K. Bulstra, Effects of vitamin E incorporation in polyethylene on oxidative degradation, wear rates, immune response, and infections in total joint arthroplasty: a review of the current literature, Int Orthop 43 (2019) 1549–1557. [CrossRef]

- H. McKellop, F.W. H. McKellop, F.W. Shen, B. Lu, P. Campbell, R. Salovey, Effect of sterilization method and other modifications on the wear resistance of acetabular cups made of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene. A hip-simulator study, J Bone Joint Surg Am 82 (2000) 1708–1725. [CrossRef]

- E. Gomez-Barrena, J.-A. E. Gomez-Barrena, J.-A. Puertolas, L. Munuera, Y.T. Konttinen, Update on UHMWPE research From the bench to the bedside, Acta Orthopaedica (2008) 832–840. [CrossRef]

- E. Oral, O.K. E. Oral, O.K. Muratoglu, Vitamin E diffused, highly crosslinked UHMWPE: a review, Int Orthop 35 (2011) 215–223. [CrossRef]

- E. Oral, S.L. E. Oral, S.L. Rowell, O.K. Muratoglu, The effect of α-tocopherol on the oxidation and free radical decay in irradiated UHMWPE, Biomaterials 27 (2006) 5580–5587. [CrossRef]

- R.D. Valladares, C. R.D. Valladares, C. Nich, S. Zwingenberger, C. Li, K.R. Swank, E. Gibon, A.J. Rao, Z. Yao, S.B. Goodman, Toll-like receptors-2 and 4 are overexpressed in an experimental model of particle-induced osteolysis, J Biomed Mater Res A 102 (2014) 3004–3011. [CrossRef]

- R. Maitra, C.C. R. Maitra, C.C. Clement, B. Scharf, G.M. Crisi, S. Chitta, D. Paget, P.E. Purdue, N. Cobelli, L. Santambrogio, Endosomal damage and TLR2 mediated inflammasome activation by alkane particles in the generation of aseptic osteolysis, Mol Immunol 47 (2009) 175–184. [CrossRef]

- C. Vermes, R. C. Vermes, R. Chandrasekaran, J.J. Jacobs, J.O. Galante, K.A. Roebuck, T.T. Glant, The effects of particulate wear debris, cytokines, and growth factors on the functions of MG-63 osteoblasts, J Bone Joint Surg Am 83 (2001) 201–211. [CrossRef]

- J.T. Hodrick, E.P. J.T. Hodrick, E.P. Severson, D.S. McAlister, B. Dahl, A.A. Hofmann, Highly crosslinked polyethylene is safe for use in total knee arthroplasty, Clin Orthop Relat Res 466 (2008) 2806–2812. [CrossRef]

- D.A. Bichara, E. D.A. Bichara, E. Malchau, N.H. Sillesen, S. Cakmak, G.P. Nielsen, O.K. Muratoglu, Vitamin E-diffused highly cross-linked UHMWPE particles induce less osteolysis compared to highly cross-linked virgin UHMWPE particles in vivo, J ARTHROPLASTY 29 (2014) 232–7. [CrossRef]

- W. Chen, D.A. W. Chen, D.A. Bichara, J. Suhardi, P. Sheng, O.K. Muratoglu, Effects of vitamin E-diffused highly cross-linked UHMWPE particles on inflammation, apoptosis and immune response against S. aureus, Biomaterials 143 (2017) 46–56. [CrossRef]

- F. Renò, P. F. Renò, P. Bracco, F. Lombardi, F. Boccafoschi, L. Costa, M. Cannas, The induction of MMP-9 release from granulocytes by vitamin E in UHMWPE, Biomaterials 25 (2004) 995–1001. [CrossRef]

- M.A. Terkawi, M. M.A. Terkawi, M. Hamasaki, D. Takahashi, M. Ota, K. Kadoya, T. Yutani, K. Uetsuki, T. Asano, T. Irie, R. Arai, T. Onodera, M. Takahata, N. Iwasaki, Transcriptional profile of human macrophages stimulated by ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene particulate debris of orthopedic implants uncovers a common gene expression signature of rheumatoid arthritis, Acta Biomater 65 (2018) 417–425. [CrossRef]

- J. Quinn, C. J. Quinn, C. Joyner, J.T. Triffitt, N.A. Athanasou, Polymethylmethacrylate-induced inflammatory macrophages resorb bone, The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery British Volume 74-B (1992) 652–658. [CrossRef]

- Sabokbar, R. Pandey, J.M. Quinn, N.A. Athanasou, Osteoclastic differentiation by mononuclear phagocytes containing biomaterial particles, Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 117 (1998) 136–140. [CrossRef]

- J.I. Pearl, T. J.I. Pearl, T. Ma, A.R. Irani, Z. Huang, W.H. Robinson, R.L. Smith, S.B. Goodman, Role of the Toll-like receptor pathway in the recognition of orthopedic implant wear-debris particles, Biomaterials 32 (2011) 5535–5542. [CrossRef]

- J.K. Antonios, Z. J.K. Antonios, Z. Yao, C. Li, A.J. Rao, S.B. Goodman, Macrophage polarization in response to wear particles in vitro, Cell Mol Immunol 10 (2013) 471–482. [CrossRef]

- Z. Huang, T. Z. Huang, T. Ma, P.-G. Ren, R.L. Smith, S.B. Goodman, Effects of orthopedic polymer particles on chemotaxis of macrophages and mesenchymal stem cells, J Biomed Mater Res A 94 (2010) 1264–1269. [CrossRef]

- L.A.J. O’Neill, D. L.A.J. O’Neill, D. Golenbock, A.G. Bowie, The history of Toll-like receptors — redefining innate immunity, Nat Rev Immunol 13 (2013) 453–460. [CrossRef]

- L. Burton, D. L. Burton, D. Paget, N.B. Binder, K. Bohnert, B.J. Nestor, T.P. Sculco, L. Santambrogio, F.P. Ross, S.R. Goldring, P.E. Purdue, Orthopedic wear debris mediated inflammatory osteolysis is mediated in part by NALP3 inflammasome activation, J Orthop Res 31 (2013) 73–80. [CrossRef]

- Y. Abu-Amer, I. Y. Abu-Amer, I. Darwech, J.C. Clohisy, Aseptic loosening of total joint replacements: mechanisms underlying osteolysis and potential therapies, Arthritis Res Ther 9 Suppl 1 (2007) S6. [CrossRef]

- M.S. Caicedo, L. M.S. Caicedo, L. Samelko, K. McAllister, J.J. Jacobs, N.J. Hallab, Increasing both CoCrMo-alloy Particle Size and Surface Irregularity Induces Increased Macrophage Inflammasome Activation In vitro Potentially through Lysosomal Destabilization Mechanisms, J Orthop Res 31 (2013) 1633–1642. [CrossRef]

- L. Samelko, S. L. Samelko, S. Landgraeber, K. McAllister, J. Jacobs, N.J. Hallab, Cobalt Alloy Implant Debris Induces Inflammation and Bone Loss Primarily through Danger Signaling, Not TLR4 Activation: Implications for DAMP-ening Implant Related Inflammation, PLoS One 11 (2016) e0160141. [CrossRef]

- Oblak, J. Pohar, R. Jerala, MD-2 Determinants of Nickel and Cobalt-Mediated Activation of Human TLR4, PLOS ONE 10 (2015) e0120583. [CrossRef]

- S.M. Kurtz, D.T. S.M. Kurtz, D.T. Holyoak, R. Trebše, T.M. Randau, A.A. Porporati, R.L. Siskey, Ceramic Wear Particles: Can They Be Retrieved In Vivo and Duplicated In Vitro?, J Arthroplasty 38 (2023) 1869–1876. [CrossRef]

- Catelas, A. Petit, D.J. Zukor, R. Marchand, L. Yahia, O.L. Huk, Induction of macrophage apoptosis by ceramic and polyethylene particles in vitro, Biomaterials 20 (1999) 625–630. [CrossRef]

- D. Bylski, C. D. Bylski, C. Wedemeyer, J. Xu, T. Sterner, F. Löer, M. von Knoch, Alumina ceramic particles, in comparison with titanium particles, hardly affect the expression of RANK-, TNF-α-, and OPG-mRNA in the THP-1 human monocytic cell line, Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 89A (2009) 707–716. [CrossRef]

- M. Lucarelli, A.M. M. Lucarelli, A.M. Gatti, G. Savarino, P. Quattroni, L. Martinelli, E. Monari, D. Boraschi, Innate defence functions of macrophages can be biased by nano-sized ceramic and metallic particles, Eur Cytokine Netw 15 (2004) 339–346.

- Y.-C. Ha, S.-Y. Y.-C. Ha, S.-Y. Kim, H.J. Kim, J.J. Yoo, K.-H. Koo, Ceramic liner fracture after cementless alumina-on-alumina total hip arthroplasty, Clin Orthop Relat Res 458 (2007) 106–110. [CrossRef]

- M.G. Zywiel, S.A. M.G. Zywiel, S.A. Sayeed, A.J. Johnson, T.P. Schmalzried, M.A. Mont, Survival of hard-on-hard bearings in total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review, Clin Orthop Relat Res 469 (2011) 1536–1546. [CrossRef]

- S. Hasan, P. S. Hasan, P. van Schie, B.L. Kaptein, J.W. Schoones, P.J. Marang-van de Mheen, R.G.H.H. Nelissen, Biomarkers to discriminate between aseptic loosened and stable total hip or knee arthroplasties: a systematic review, EFORT Open Rev 9 (2024) 25–39. [CrossRef]

- Biomarkers Definitions Working Group., Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework, Clin Pharmacol Ther 69 (2001) 89–95. [CrossRef]

- R.K. Chaganti, E. R.K. Chaganti, E. Purdue, T.P. Sculco, L.A. Mandl, Elevation of serum tumor necrosis factor α in patients with periprosthetic osteolysis: a case-control study, Clin Orthop Relat Res 472 (2014) 584–589. [CrossRef]

- Z. Hundrić-Haspl, M. Z. Hundrić-Haspl, M. Pecina, M. Haspl, M. Tomicic, I. Jukic, Plasma cytokines as markers of aseptic prosthesis loosening, Clin Orthop Relat Res 453 (2006) 299–304. [CrossRef]

- W. Wu, X. W. Wu, X. Zhang, C. Zhang, T. Tang, W. Ren, K. Dai, Expansion of CD14+CD16+ peripheral monocytes among patients with aseptic loosening, Inflamm Res 58 (2009) 561–570. [CrossRef]

- Moreschini, S. Fiorito, L. Magrini, F. Margheritini, L. Romanini, Markers of connective tissue activation in aseptic hip prosthetic loosening, J Arthroplasty 12 (1997) 695–703. [CrossRef]

- T. He, W. T. He, W. Wu, Y. Huang, X. Zhang, T. Tang, K. Dai, Multiple biomarkers analysis for the early detection of prosthetic aseptic loosening of hip arthroplasty, Int Orthop 37 (2013) 1025–1031. [CrossRef]

- E. López-Anglada, J. E. López-Anglada, J. Collazos, A.H. Montes, L. Pérez-Is, I. Pérez-Hevia, S. Jiménez-Tostado, T. Suárez-Zarracina, V. Alvarez, E. Valle-Garay, V. Asensi, IL-1 β gene (+3954 C/T, exon 5, rs1143634) and NOS2 (exon 22) polymorphisms associate with early aseptic loosening of arthroplasties, Sci Rep 12 (2022) 18382. [CrossRef]

- F. Tang, X. F. Tang, X. Liu, H. Jiang, H. Wu, S. Hu, J. Zheng, H. Guo, L. Yan, C. Xu, Y. Lin, J. Lin, J. Zhao, Biomarkers for early diagnosis of aseptic loosening after total hip replacement, (2016).

- S.K. Trehan, L. S.K. Trehan, L. Zambrana, J.E. Jo, E. Purdue, A. Karamitros, J.T. Nguyen, J.M. Lane, An Alternative Macrophage Activation Pathway Regulator, CHIT1, May Provide a Serum and Synovial Fluid Biomarker of Periprosthetic Osteolysis, HSS J 14 (2018) 148–152. [CrossRef]

- Morakis, S. Tournis, E. Papakitsou, I. Donta, G.P. Lyritis, Decreased tibial bone strength in postmenopausal women with aseptic loosening of cemented femoral implants measured by peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT), J Long Term Eff Med Implants 21 (2011) 291–297. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Wilkinson, A.J. J.M. Wilkinson, A.J. Hamer, A. Rogers, I. Stockley, R. Eastell, Bone mineral density and biochemical markers of bone turnover in aseptic loosening after total hip arthroplasty, J Orthop Res 21 (2003) 691–696. [CrossRef]

- J. Antoniou, O. J. Antoniou, O. Huk, D. Zukor, D. Eyre, M. Alini, Collagen crosslinked N-telopeptides as markers for evaluating particulate osteolysis: a preliminary study, J Orthop Res 18 (2000) 64–67. [CrossRef]

- L. Savarino, S. L. Savarino, S. Avnet, M. Greco, A. Giunti, N. Baldini, Potential role of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b (TRACP 5b) as a surrogate marker of late loosening in patients with total hip arthroplasty: a cohort study, J Orthop Res 28 (2010) 887–892. [CrossRef]

- N.R. Lawrence, R.L. N.R. Lawrence, R.L. Jayasuriya, F. Gossiel, J.M. Wilkinson, Diagnostic accuracy of bone turnover markers as a screening tool for aseptic loosening after total hip arthroplasty, Hip Int 25 (2015) 525–530. [CrossRef]

- M. Ovrenovits, E.E. M. Ovrenovits, E.E. Pakos, G. Vartholomatos, N.K. Paschos, T.A. Xenakis, G.I. Mitsionis, Flow cytometry as a diagnostic tool for identifying total hip arthroplasty loosening and differentiating between septic and aseptic cases, Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 25 (2015) 1153–1159. [CrossRef]

- S. Papagiannis, I. S. Papagiannis, I. Tatani, G. Kyriakopoulos, Z. Kokkalis, P. Megas, C. Stathopoulos, K. Grafanaki, J. Lakoumentas, Alterations in Small Non-coding MicroRNAs (miRNAs) and the Potential Role in the Development of Aseptic Loosening After Total Hip Replacement: Study Protocol for an Observational, Cross-Sectional Study, Cureus 16 (2024) e72179. [CrossRef]

- R. Minaei Noshahr, F. R. Minaei Noshahr, F. Amouzadeh Omrani, A. Yadollahzadeh Chari, M. Salehpour Roudsari, F. Madadi, S. Shakeri Jousheghan, A. Manafi-Rasi, MicroRNAs in Aseptic Loosening of Prosthesis: Pathophysiology and Potential Therapeutic Approaches, Arch Bone Jt Surg 12 (2024) 612–621. [CrossRef]

- M.H.A. Malik, F. M.H.A. Malik, F. Jury, A. Bayat, W.E.R. Ollier, P.R. Kay, Genetic susceptibility to total hip arthroplasty failure: a preliminary study on the influence of matrix metalloproteinase 1, interleukin 6 polymorphisms and vitamin D receptor, Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 66 (2007) 1116–1120. [CrossRef]

- H.F. Alotaibi, S. H.F. Alotaibi, S. Perni, P. Prokopovich, Nanoparticle-based model of anti-inflammatory drug releasing LbL coatings for uncemented prosthesis aseptic loosening prevention, Int J Nanomedicine 14 (2019) 7309–7322. [CrossRef]

- B.H. van Duren, A.M. B.H. van Duren, A.M. Firth, R. Berber, H.E. Matar, P.J. James, B.V. Bloch, Revision Rates for Aseptic Loosening in the Obese Patient: A Comparison Between Stemmed, Uncemented, and Unstemmed Tibial Total Knee Arthroplasty Components, Arthroplasty Today 32 (2025) 101621. [CrossRef]

- J.T. Layson, D. J.T. Layson, D. Hameed, J.A. Dubin, M.C. Moore, M. Mont, G.R. Scuderi, Patients with Osteoporosis Are at Higher Risk for Periprosthetic Femoral Fractures and Aseptic Loosening Following Total Hip Arthroplasty, Orthop Clin North Am 55 (2024) 311–321. [CrossRef]

- S.K. Patel, J.E. S.K. Patel, J.E. Dilley, A. Carlone, E.R. Deckard, R.M. Meneghini, K.A. Sonn, Effect of Tobacco Use on Radiolucent Lines in Modern Cementless Total Knee Arthroplasty Tibial Components, Arthroplasty Today 19 (2023). [CrossRef]

- S. Teng, C. S. Teng, C. Yi, C. Krettek, M. Jagodzinski, Smoking and Risk of Prosthesis-Related Complications after Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies, PLOS ONE 10 (2015) e0125294. [CrossRef]

- B.H. Kapadia, K. B.H. Kapadia, K. Issa, R. Pivec, P.M. Bonutti, M.A. Mont, Tobacco use may be associated with increased revision and complication rates following total hip arthroplasty, J Arthroplasty 29 (2014) 777–780. [CrossRef]

- M. Khatod, G. M. Khatod, G. Cafri, R.S. Namba, M.C.S. Inacio, E.W. Paxton, Risk Factors for Total Hip Arthroplasty Aseptic Revision, The Journal of Arthroplasty 29 (2014) 1412–1417. [CrossRef]

- D. Apostu, O. D. Apostu, O. Lucaciu, C. Berce, D. Lucaciu, D. Cosma, Current methods of preventing aseptic loosening and improving osseointegration of titanium implants in cementless total hip arthroplasty: a review, J Int Med Res 46 (2018) 2104–2119. [CrossRef]

- S. Safavi, Y. S. Safavi, Y. Yu, D.L. Robinson, H.A. Gray, D.C. Ackland, P.V.S. Lee, Additively manufactured controlled porous orthopedic joint replacement designs to reduce bone stress shielding: a systematic review, Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research 18 (2023) 42. [CrossRef]

- D. Apostu, O. D. Apostu, O. Lucaciu, C. Berce, D. Lucaciu, D. Cosma, Current methods of preventing aseptic loosening and improving osseointegration of titanium implants in cementless total hip arthroplasty: a review, J Int Med Res 46 (2018) 2104–2119. [CrossRef]

- F. De Meo, G. F. De Meo, G. Cacciola, V. Bellotti, A. Bruschetta, P. Cavaliere, Trabecular Titanium acetabular cups in hip revision surgery: mid-term clinical and radiological outcomes, Hip Int 28 (2018) 61–65. [CrossRef]

- G. Cacciola, F. G. Cacciola, F. Giustra, F. Bosco, F. De Meo, A. Bruschetta, I. De Martino, S. Risitano, L. Sabatini, A. Massè, P. Cavaliere, Trabecular titanium cups in hip revision surgery: a systematic review of the literature, Ann Jt 8 (2023) 36. [CrossRef]

- Y.-L. Chen, T. Y.-L. Chen, T. Lin, A. Liu, M.-M. Shi, B. Hu, Z. Shi, S.-G. Yan, Does hydroxyapatite coating have no advantage over porous coating in primary total hip arthroplasty? A meta-analysis, Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research 10 (2015) 21. [CrossRef]

- B.M. Isaacson, S. B.M. Isaacson, S. Jeyapalina, Osseointegration: a review of the fundamentals for assuring cementless skeletal fixation, ORR 6 (2014) 55–65. [CrossRef]

- K.L. McCormick, M.A. K.L. McCormick, M.A. Mastroianni, N.L. Kolodychuk, C.L. Herndon, R.P. Shah, H.J. Cooper, N.O. Sarpong, Complications and Survivorship After Aseptic Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty: Is There a Difference by Surgical Approach?, J Arthroplasty 40 (2025) 203–207. [CrossRef]

- V. Lindgren, G. V. Lindgren, G. Garellick, J. Kärrholm, P. Wretenberg, The type of surgical approach influences the risk of revision in total hip arthroplasty: a study from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register of 90,662 total hipreplacements with 3 different cemented prostheses, Acta Orthop 83 (2012) 559–565. [CrossRef]

- F. Birrell, S. F. Birrell, S. Lohmander, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs after hip replacement, BMJ 333 (2006) 507–508. [CrossRef]

- G. Friedl, R. G. Friedl, R. Radl, C. Stihsen, P. Rehak, R. Aigner, R. Windhager, The effect of a single infusion of zoledronic acid on early implant migration in total hip arthroplasty. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial, J Bone Joint Surg Am 91 (2009) 274–281. [CrossRef]

| Category | Biomarkers | Levels in AL Patients | Role | Sample | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory Biomarkers | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, CD14+CD16+ monocytes, MCP-1, CCL18 | High | Indicative of an active inflammatory response that promotes the recruitment and activation of immune cells, contributing to bone destruction. | Blood, synovial fluid | [109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116] |

| Bone Metabolism | RANKL, CTX, NTX, TRAP5b, ICTP, | High | Represent the altered balance between bone formation and resorption; increased resorption and reduced bone formation, typical of AL | Blood, urine | [113,115,116,117,118,119,120,121] |

| Osteocalcin, PiCP | Low | ||||

| Matrix Degradation | Hyaluronic acid, CHIT1, CD18, CD11b, CD11c | High | Signals of extracellular matrix degradation and cellular activation, indicative of tissue damage and local immune response. | Blood, synovial fluid | [112,116,122] |

| MicroRNA | miR-21, miR-92a, miR-106b, miR-130, miR-135, miR-155 | High | Involved in the regulation of inflammatory processes and bone remodeling, contributing to the altered balance between osteoresorption and formation. | Blood | [123,124] |

| miR-29 | Low | ||||

| Genetic Factors | SNPs in NOS2 (AA genotype), IL-1β (TT genotype), and MMP1 | Associated with increased risk | Genetically predispose to the establishment of an accentuated inflammatory response and aberrant bone remodeling, favoring the development of AL | Blood | [114,125] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).