1. Introduction

The need for sustainable energy solutions that address climate change and energy demand has increased in tandem with the rise in atmospheric CO₂ levels. One possible method for turning solar energy into chemical fuels is photocatalytic CO₂ reduction with visible light. However, because of its strong C=O bonds (750 kJ/mol), large band gap (13.7 eV) and high reduction potential, CO₂ has inherent thermodynamic and kinetic stability, which hinders the reduction process [

1]. Nonetheless, Ru complexes have garnered a lot of interest as both PS and Cat because of its advantageous photochemical and redox characteristics.

To overcome the drawbacks of traditional PS/Cat-mixed systems, integrated assemblies such as dyads, hybrids/supramolecular composites have been developed to enhance charge transfer and catalyst stability. Additionally, recent advancements, including self-photosensitizing complexes, pincer ligands, and transition metal (TM) cocatalysts have demonstrated improved selectivity and turnover (TON) under milder, more sustainable conditions. This review offers a critical analysis of recent progress in Ru(II)-catalyzed CO₂ photoreduction, with emphasis on molecular design fundamentals, mechanistic insights, and developing hybrid strategies. By exploring structure-functionality relationships and highlighting key advancements, the review aims to guide novel advances in next-generation Ru(II)-based photocatalytic systems for efficient and selective solar-to-chemical energy transformation.

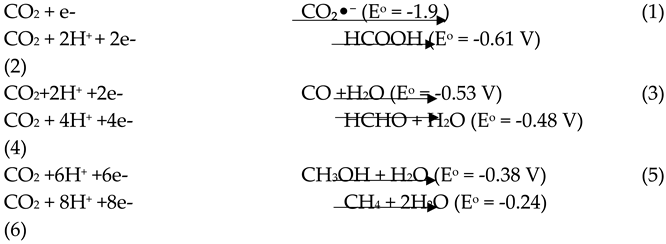

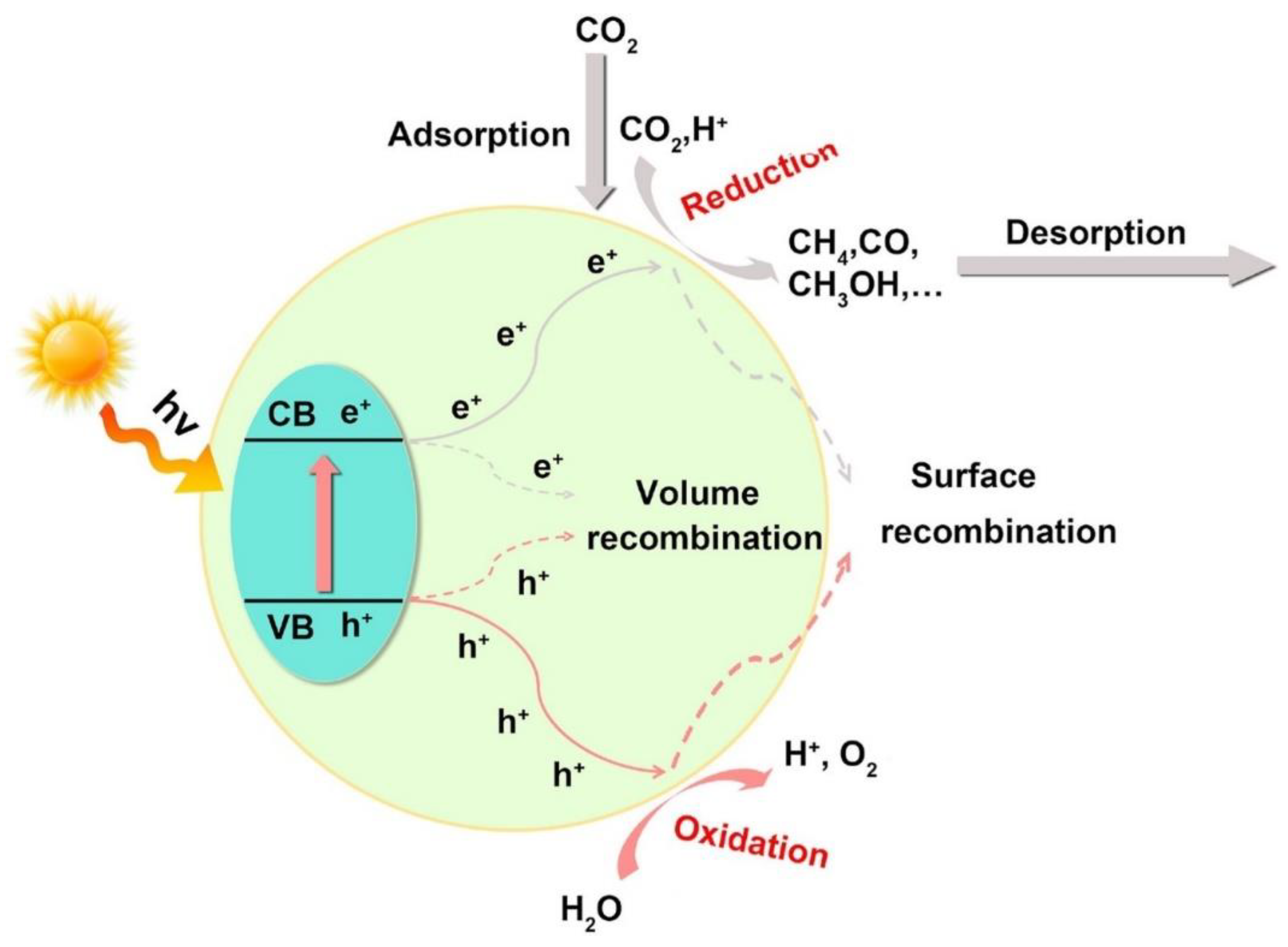

2. Mechanism of photocatalytic CO2 reduction

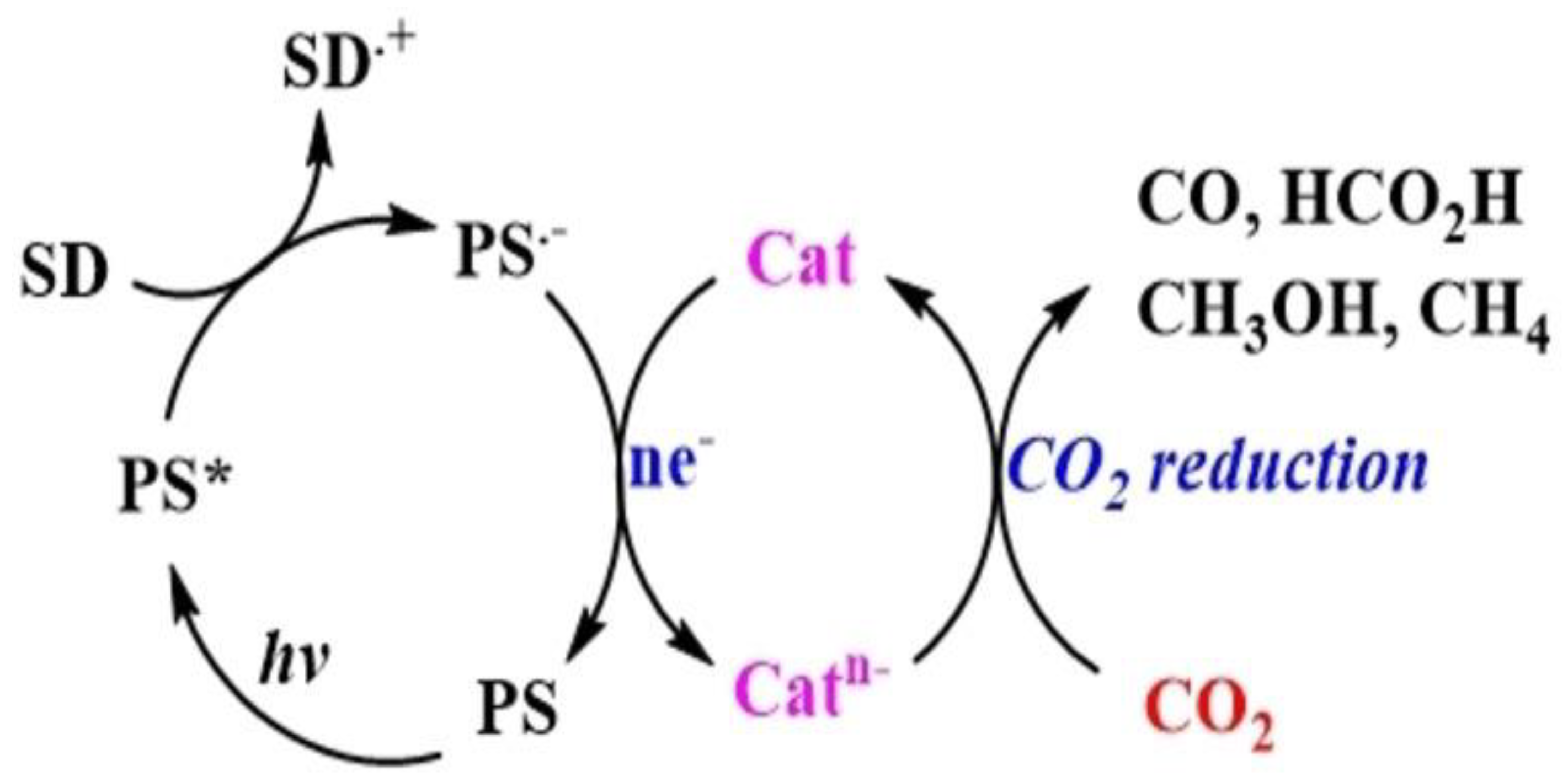

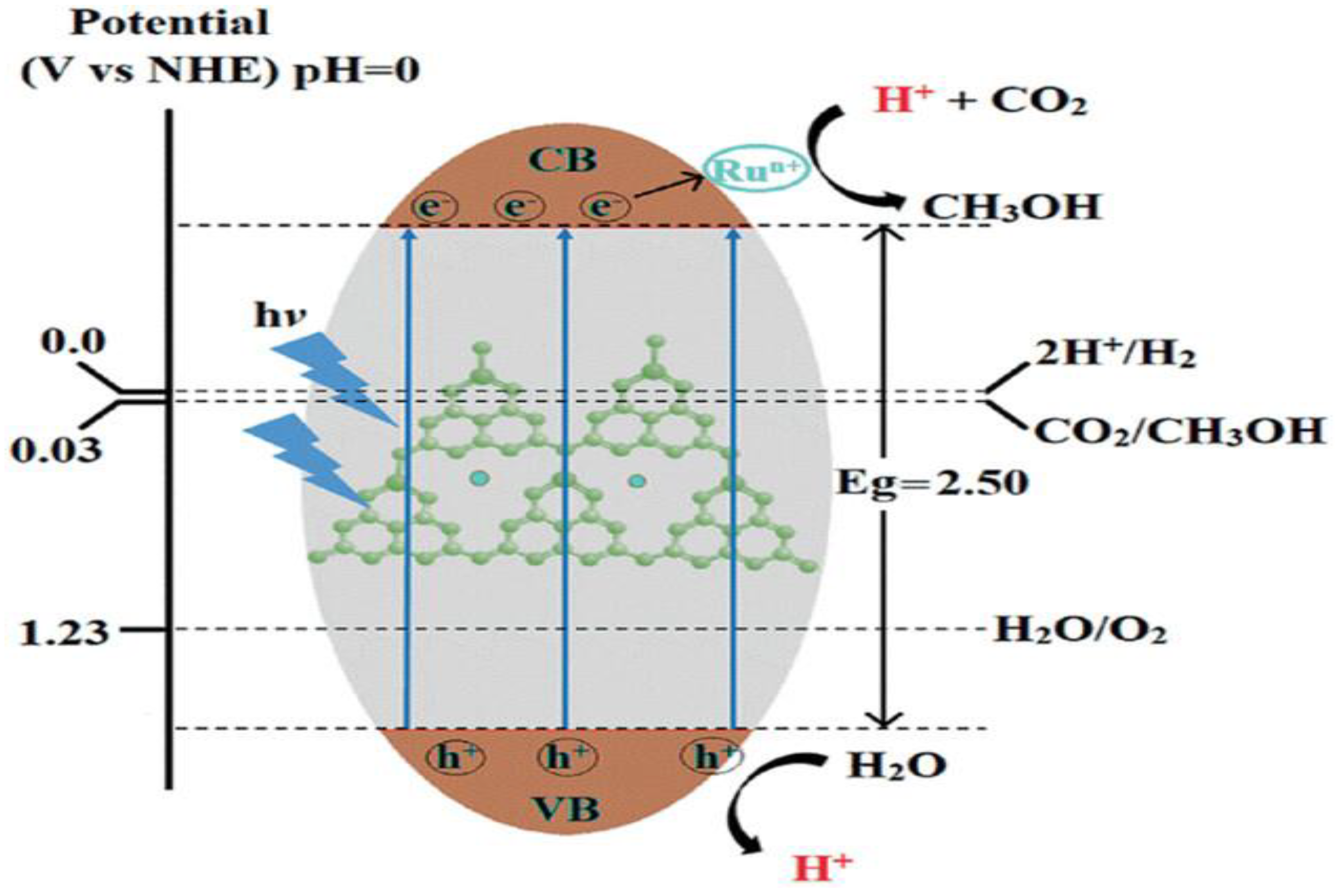

The photoreduction of CO

2 is predominantly a surface process that utilizes protons (H⁺) and photo-generated charge carriers (e⁻/h⁺) as shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows that the key stages in CO

2 photoreduction include light absorption, CO

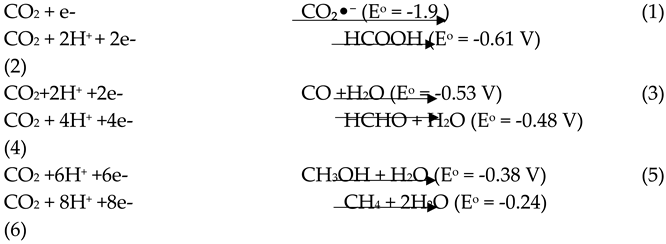

2 adsorption, surface-redox reactions, electron-hole (e-/h+) pair formation, and product desorption. Another essential process component is the separation and transfer of charge. However, the one-electron reduction of CO₂ generates a CO₂ radical anion (CO₂•⁻) (Eq. 1), which has a high reduction potential (-1.9 V vs. SHE in water at pH 7) [

3], making the process thermodynamically unfavorable. Alternatively, multi-electron reduction via proton-coupled electron transfer (Eq. 2–6) can yield stable, energy-dense products at relatively lower reduction potentials[

4,

5,

6].

However, the kinetic barrier generally increases with additional electrons and protons participating in the reaction[

3]. Furthermore, the multistep photocatalytic process frequently leads to low efficiency, particularly in the transport and separation of photoinduced charge carriers. Therefore, a catalyst capable of promoting multi-electron and multi-proton transfers is necessary to facilitate efficient turnovers. For example, the band gap energy of the photocatalyst must meet the thermodynamic requirements for CO₂ photoreduction to facilitate electron transfer to the CO₂ molecules adsorbed on its surface [

4]. Additionally, the valence band (VB) edge must be positioned at a more negative potential than the standard reduction potential (E°red) of CO₂ to ensure the thermodynamic feasibility of its conversion to other products[

5]. Importantly, the distribution of reduction products is influenced by the photocatalyst's band edge position, which controls the build-up of electrons [

7]

4. Photocatalytic CO2 reduction using metal molecular catalysts

As much as the highlighted limitations of CO

2 hinder the photocatalytic performance, significant progress has been realised in the development of more effective photocatalysts with superior qualities. Among them, visible light-active molecular catalysts have shown attractive results. The most common molecular catalysts include Re(I) (Re(bpy)(CO)₃Cl), Ru(II) (Ru(bpy)₃²⁺), Ir(III) ([Ir(ppy)₃]), Ni(II) (Ni(cyclam)), Co(II) (Co(bpy)₃²⁺), and Mn(I) (Mn(bpy)(CO)₃Br) complexes (bpy: 2,2'-bipyridine; ppy: 2-phenylpyridine). These systems absorb light and transition to an excited state capable of facilitating redox reactions [

8]. The advantages of molecular catalysts include their molecular-scale design and adjustable organic ligands, which allow precise control over functionality (e.g., photophysical, electrochemical, and catalytic properties), leading to enhanced light absorption, catalytic activity, and selectivity [

9]. However, like other systems, metal complexes have drawbacks such as solubility issues, catalyst deactivation, poor recyclability, scalability challenges, high costs of precious metals, and the need for multiple components in solution, which can result in inefficient and random interactions [

9]

A typical photocatalytic CO₂ reduction system involving molecular components consists of three parts: a redox PS for harvesting light energy, an SD that provides electrons for the reduction process, and a Cat that serves as the active site for CO₂ transformation. The photoreduction process can proceed via two main mechanisms: oxidative quenching and reductive quenching. In reductive quenching, the SD transfers an electron to the excited state of the PS (PS*), forming a reduced species (PS•⁻), commonly referred to as the one-electron-reduced species (OERS) [

8]. The PS•⁻ then donates an electron to the catalyst, facilitating CO₂ reduction . Through successive iterations of this process, depending on the number of electrons required for the desired product, CO₂ can be converted into chemical fuels. Notably, in some cases, PS* can directly transfer an electron to the catalyst, although this pathway is less common [

10,

11]

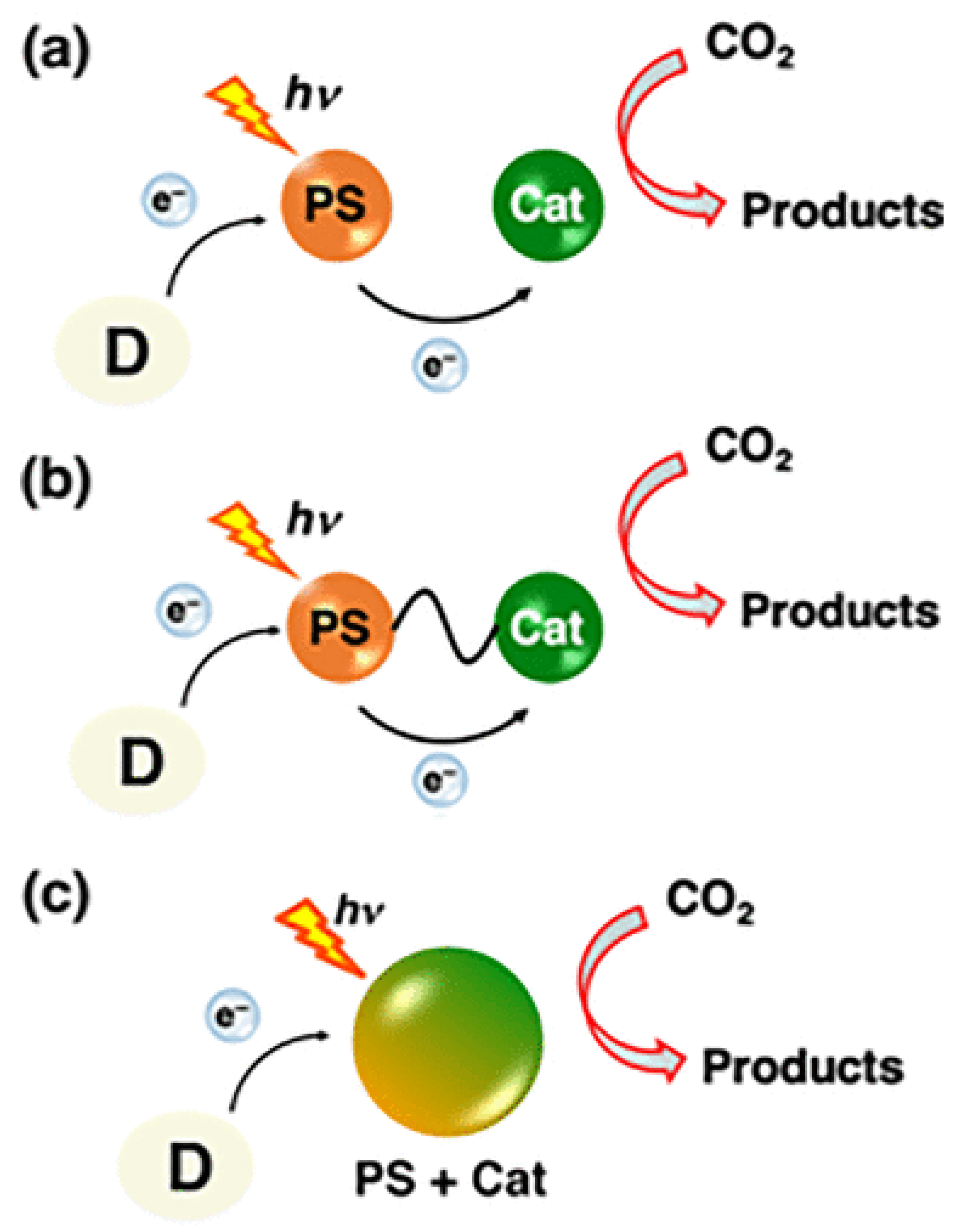

Figure 2 illustrates a typical reductive quenching system.

4. Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction Using Metal Molecular Catalysts

On the other hand, although feasible, the oxidative quenching mechanism, wherein PS* directly donates an electron to the Cat is less common. This may be due to the highly negative E

red required for CO₂ conversion, which necessitates that the OERS, possess a greater reducing power than the corresponding PS[

11]. The formation of strong and relatively stable oxidants, such as PS•⁺, in the reaction medium is unfavourable for CO₂ reduction, as these species can hinder efficient electron transfer to the catalyst [

12].

The initial electron transfer from SD to PS* (Figureure. 2) is thermodynamically favorable when the Eored of PS* is comparable to or more positive than the oxidation potential (Eoox) of SD. The Eored of PS* can be calculated using Eq. (1) [

11,

13]

The equation implies that the oxidation state of the catalyst is governed by the redox potential of the PS*/PS•⁻ couple. The efficiency of electron transfer can be evaluated using the quenching rate constant (kq) and quenching efficiency (ηq). The kq is determined from Stern–Volmer plots and the lifetime of PS*, while ηq, representing the fraction of PS* that forms PS•⁻, is calculated using Eq. (2)[

14]

A higher quenching fraction (ηq) leads to an increase in quantum efficiency, and vice versa. Other critical process parameters for measuring the performance of CO

2 photoreduction include turnover number (TON), Apparent Quantum Yield (AQY) and selectivity (S):

TON > 1 indicates the feasibility of the CO

2 reduction process, as well as high catalyst durability.

A higher AQY suggests a more effective use of light in driving the CO₂ photoreduction process.

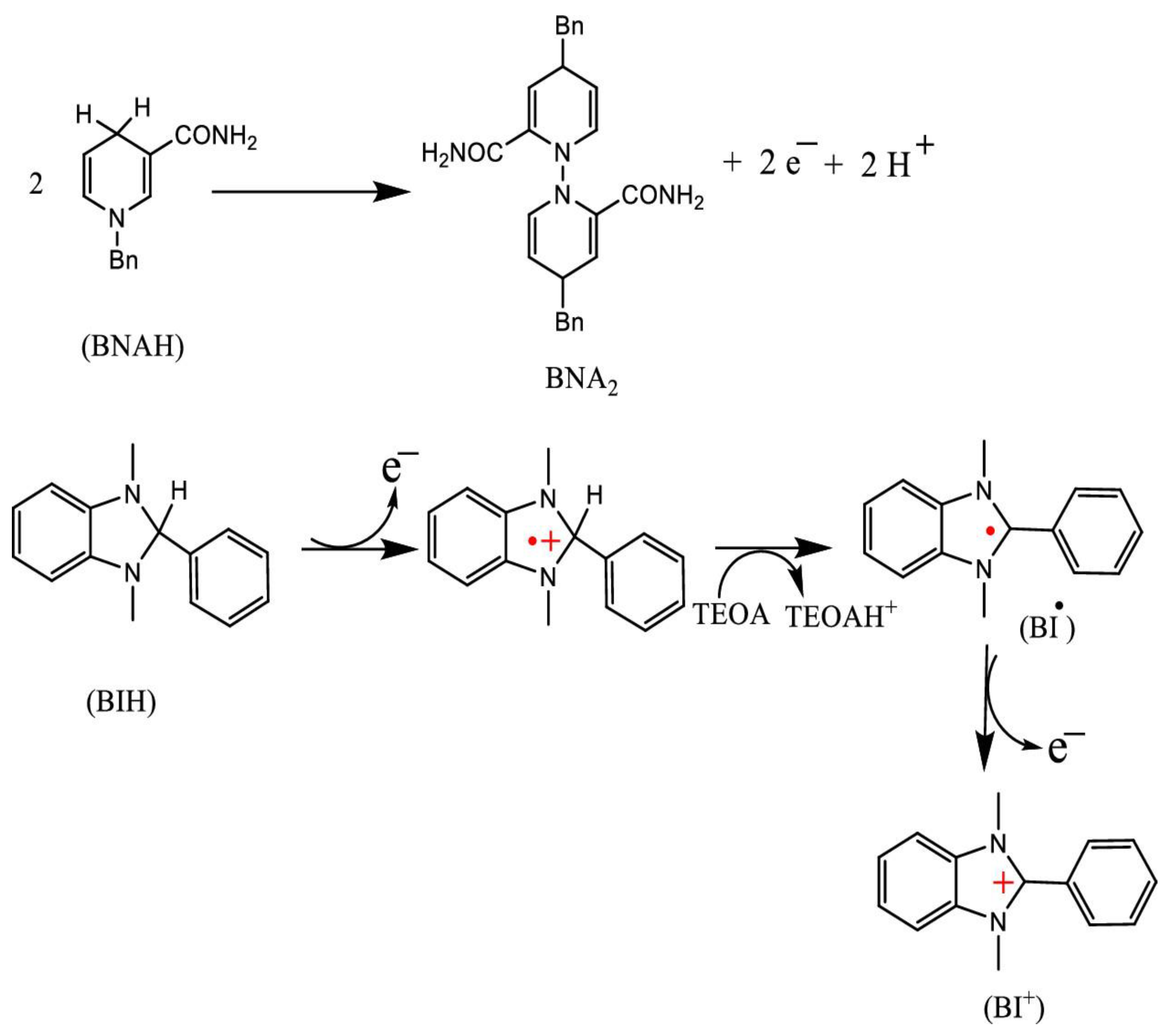

4.1. Electron Donors

Electron donors release a proton in the oxidized electron donor state (OEOS), which is crucial for suppressing back-electron transfer from the OERS of the PS to the OEOS of the SD [

12]. Commonly used SDs include aliphatic amines such as triethylamine (TEA) and triethanolamine (TEOA), ascorbate (AscH⁻), and NADH model compounds such as 1-benzyl-1,4-dihydronicotinamide (BNAH) and dihydro-1H-benzo[d]imidazole derivatives (BIH, BI(OH)H). These SDs have often been employed in photochemical CO₂ reduction reactions.

Figure 3 illustrates the mechanism of sacrificial reduction by BNAH and BIH in the presence of TEOA.

TEOA is a commonly used SD for reductive quenching of PS*, functioning as a Brønsted base in the presence of stronger electron donors such as BNAH and BIH. While TEOA does not directly quench PS*, it can abstract a proton from BNAH•⁺ or BIH•⁺ in the reaction medium [

15]. BNAH, with a stronger reducing potential E°(BNAH/BNAH⁺) = 0.57 V vs. SCE in acetonitrile (MeCN), is more effective than TEA (Eₚ = 0.96 V) and TEOA (Eₚ = 0.80 V) at reducing PS* [

11]. Furthermore, BNAH can efficiently undergo reductive quenching, and its reducing power is retained in aqueous media, unlike aliphatic amines, whose protonation diminishes their effectiveness [

9]

BIH and BI(OH)H show a stronger reducing tendency than BNAH with E₁/₂(ox) values of 0.33 V and 0.31 V vs. SCE, respectively [

9]. BIH follows a unique two-electron oxidation via first electron transfer, followed by deprotonation and a second electron transfer [

12]. The deprotonated intermediate (BI•) exhibits negative oxidation potential, facilitating efficient electron transfer in CO2 photoreduction. BIH also shows weak basicity, although its protonated form (BIH₂⁺) is inactive in reductive quenching and less effective without TEOA [

16]. On the other hand, BI(OH)H donates two electrons and two protons, forming BI(O⁻)⁺ and selectively converting CO₂ to formic acid (HCOOH). This dual electron–proton transfer increases its effectiveness over BIH. In contrast, BNAH donates only one electron and one proton. These mechanistic differences strongly affect the donors' reactivity and selectivity in CO₂ photo conversion . Importantly, an ideal SD enhances reductive quenching efficiency, thereby improving overall photocatalytic performance.

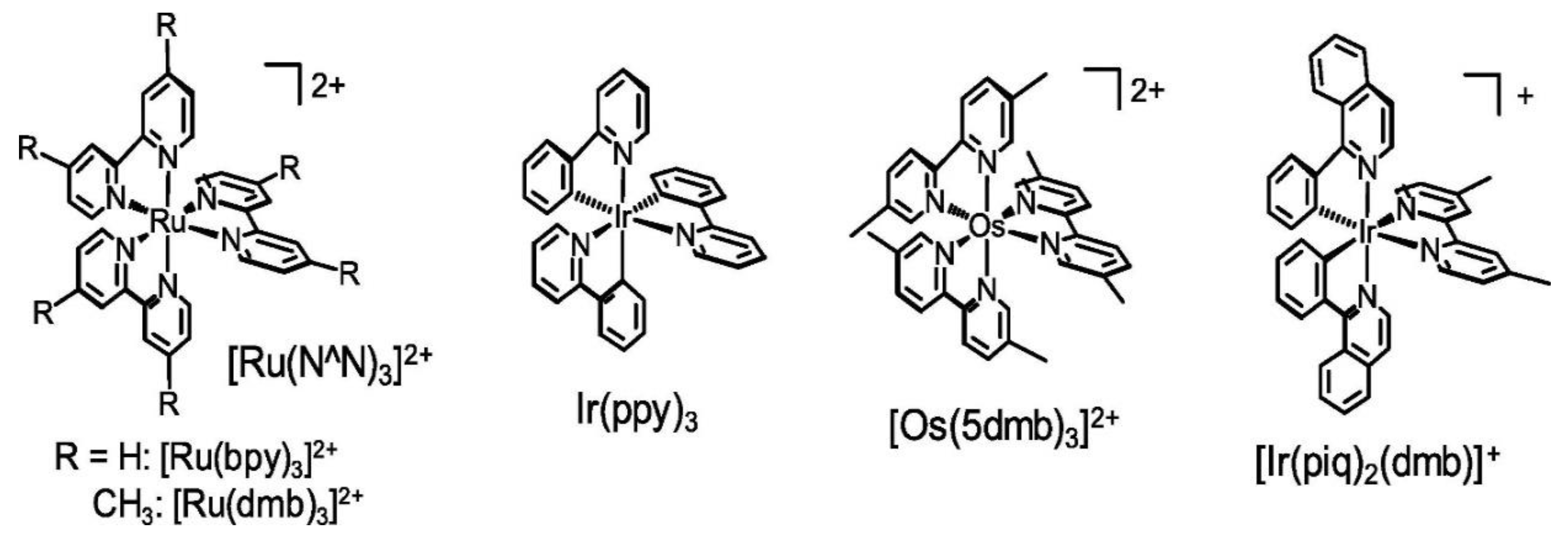

4.2. Photosensitizers

Generally, the PS should enable electron transfer from the SD to the Cat upon photoexcitation. Thus, key requirements for an effective PS include: (i) strong absorption at the excitation wavelength, particularly in the visible range, to efficiently harvest solar energy and suppress absorption by coexisting species such as the SD and Cat; (ii) a long-lived excited state to promote efficient reductive quenching; (iii) a high oxidative potential in the PS* to readily accept an electron from the donor; and (iv) high photochemical stability of the PS•⁻ along with efficient intersystem crossing [

17]. Phosphorescent metal complexes, particularly those based on Ru, iridium (Ir), and osmium (Os) (

Figure 4) are widely employed as photosensitizers in CO₂ reduction systems. The popularity of these compounds stems from favourable redox properties and excellent photosensitizing performance, attributed to their metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) excited states, which typically exhibit lifetimes in the nanosecond to microsecond range [

18].

Among these PSs, [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺ and its derivatives were among the first employed in CO₂ reduction systems [

13] While the OERS of most Ru(II)ⁿ⁺ complexes are generally stable in the dark, photoexcitation can occasionally induce their decomposition, leading to the formation of [Ru(bpy)₂X₂]ᵐ⁺-type complexes, where X may be a solvent molecule, CO, or Cl⁻ [

13]. These decomposition products can themselves act as photocatalysts for CO₂ reduction, enabling the reaction to proceed even in the absence of an added catalyst, which can affect product selectivity [

19]. In the presence of water, CO₂ can be converted to formate (HCOO-) [

20].

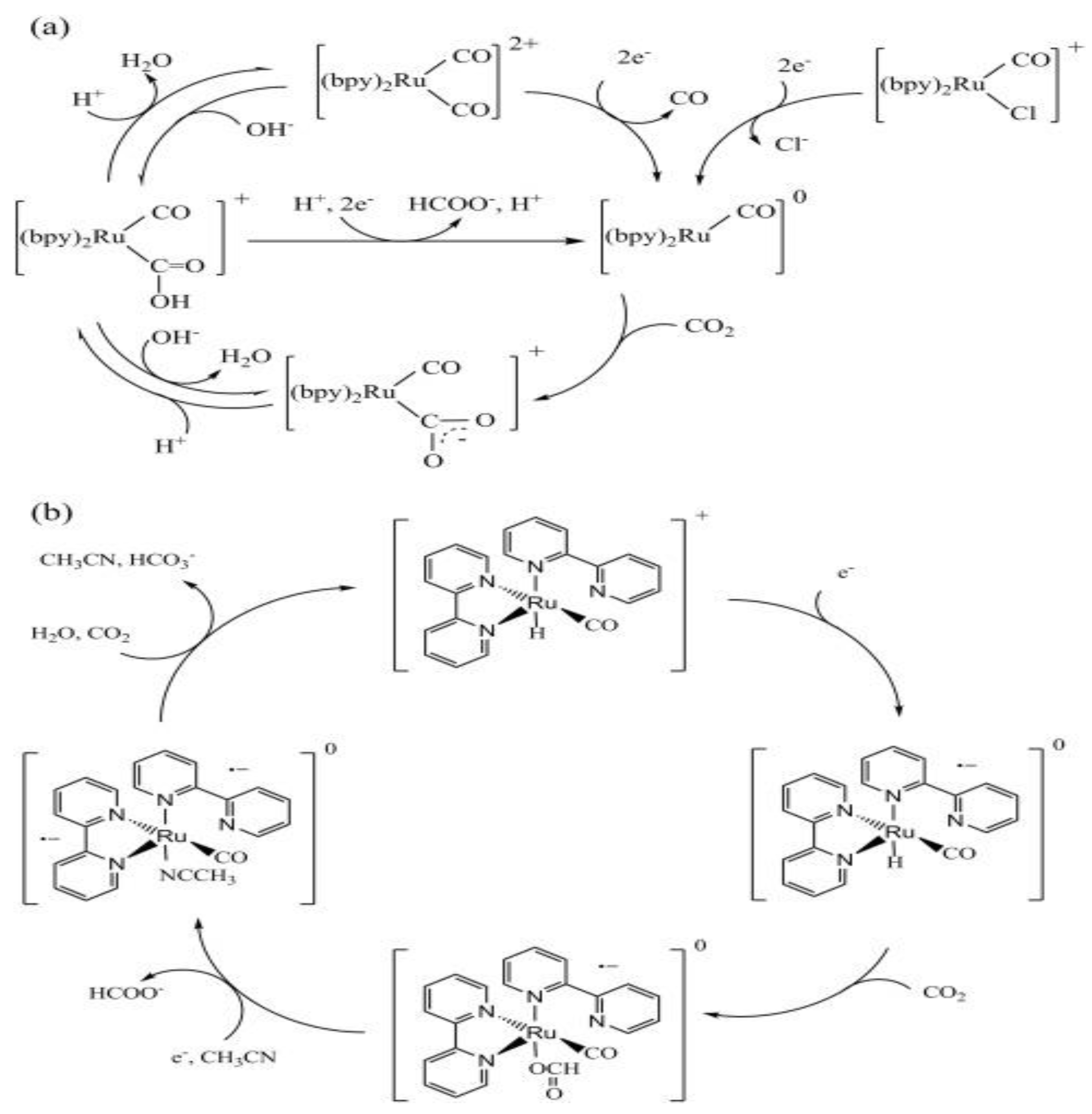

4.3. Catalytic roles of [Ru(bpy)₂(CO)₂]²⁺ Complexes

In recent years, [Ru(bpy)₂(CO)₂]²⁺ (Ru(CO))-type complexes and their derivatives have been frequently employed as catalysts in CO

2 photoreduction.

Table 1 displays some of the common Ru (II) complexes used as catalysts in CO

2 reduction.

Similarly to [Ru(bpy)₃] ²⁺, Ru(CO) complexes exhibit strong visible-light absorption, high CO₂-binding affinity, enhanced product selectivity, and multiple accessible redox states that support multielectron reduction processes [

9]. These Ru(II) complexes also demonstrate excellent durability and preferentially reduce CO₂ over protons, even in aqueous media [

19]. The presence of labile halide ligands enables CO₂ coordination via halogen replacement, forming M-C bonds that promote selective CO₂ binding to the metal center [

23]. Additionally, Ru(CO)-type complexes can serve dual roles, as both PSs and Cat in some systems. This was demonstrated by Tanaka et al. and the Meyer group in their pioneering work using Ru(CO) to convert CO₂ into carbon monoxide (CO) and formate in MeCN with TEOA as the SD under visible light [

22]. The authors went on to propose a possible mechanism for the photoreduction of CO

2 into CO and HCOO-, as shown in

Figure 5

The CO formation cycle (

Figure 5(a)) involves a two-electron reduction, where the Ru(II) complex, [Ru(CO)₂]²⁺ accepts two electrons, releases CO, and forms an unstable intermediate, [Ru(CO)]⁰. The [Ru(CO)]⁰ then undergoes electrophilic attack by CO₂, followed by protonation and dehydration, to regenerate the original Ru(II) complex. In contrast, the formate cycle (

Figure 5(b) begins with the one-electron reduction of [Ru(CO)H]⁺ to [Ru(CO)H]⁰, which reacts with CO₂ to form [Ru₂(CO)(OCHO)]⁰. Subsequent electron transfer and coordination with an MeCN molecule lead to the release of HCOO- and the formation of [Ru(CO)(NCCH₃)]⁰. Final protonation and solvent dissociation regenerate the initial hydride species [

19,

22]. While similar mechanisms have been proposed in recent studies [

1,

23,

24,

25], no universally accepted mechanism yet, fully explains the photocatalytic activity and product selectivity of Ru(II) complexes. Additionally, a common limitation of Ru(CO) is its tendency to polymerize into [Ru(CO)]ₙ precipitates, which poorly accept electrons from the PS [

4]. In such cases, the efficiency of CO₂ photoreduction can be improved by adding excess PS and SD [

3].

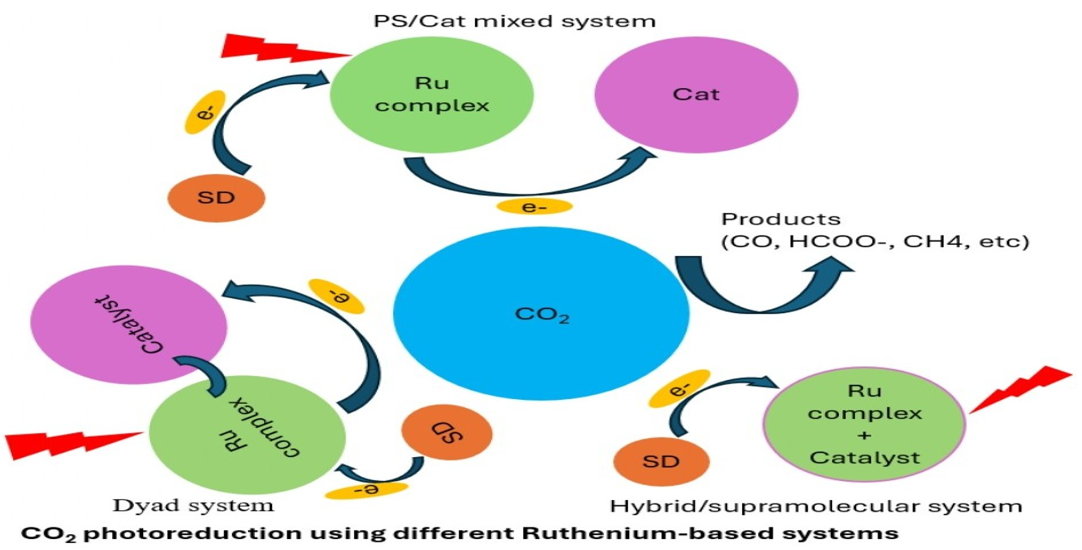

4.5. Systematic Approaches to Ru-Driven CO₂ Photoreduction

Ru-based photocatalytic systems for CO₂ conversion can be divided into three categories: (a) PS/Cat mixed systems, (b) dyad systems, and (c) hybrid or supramolecular catalyst systems, as illustrated in

Figure 6

In mixed PS/Cat systems, electron transfer (ET) from the PS* to the Cat is often rate-limiting, as it depends on physical contact. Performance can be hindered by PS instability in both PS* and PS•⁻, particularly in homogenous systems where interactions are limited by diffusion [

3]. Similar ET constraints can potentially appear in heterogeneous systems, depending on redox stability and interfacial charge transfer dynamics. Dyad systems, by contrast, constitute a covalently linked PS and Cat within a single molecule, for example, a binuclear Ru complex, [Ru(bpy)₂(bpm)Ru(CO)₂Cl₂] (RuRu), in which both Ru centers are bridged via a bpm ligand [

1]. Upon photoexcitation, an SD donates an electron to the PS, forming PS•⁻, which then transfers the electron intramolecularly to the Cat. According to Ishizuka et al. [

26], the overall efficiency of dyads depends on two successive ET steps: from the donor to the PS* and from PS•⁻ to the catalytic site. On the other hand, supramolecular photocatalysts integrate both PS and Cat units into multinuclear complexes (i.e., MOF-253-Ru(dcbpy)

2Ru-(dcbpy)

2Cl

2) (MOF: metal organic framework) [

13], promoting short intramolecular ET distances. This integration improves CO₂ photoreduction performance by reducing mass transfer limitations and enhancing ET efficiency, in contrast to systems with physically separated components.

4.6. Emerging Trends in Ru-Based CO₂ Photocatalysis

Recent developments in CO₂ photoreduction have focused on integrating multiple functional components into hybrid molecular catalysts to improve photocatalytic efficiency through synergistic effects [

17,

27]. The multicomponent systems provide a promising strategy for sustainable CO₂ conversion. Growing attention has also been given to earth-abundant transition metals such as Ni, Co, Mn, Fe, Cu, and Zn, which align with cost-effectiveness and environmental sustainability goals.. The strong Lewis acidity of transition metals can further boost catalytic activity when incorporated into nanocomposites. Moreover, Ru (II) complexes, known for their photochemical stability, have shown strong potential as PS ligands in complexes with low-valent metals, promoting effective and robust photocatalytic applications [

29,

30].

4.6.1. Photosensitizer/catalyst mixed systems

Table 2 summarizes recent research focused on mixed PS/Cat systems with Ru complexes as PSs for CO₂ photoreduction.

From

Table 2, CO

2 reduction can be performed using either homogeneous or heterogeneous systems and the product distribution appears to be independent of the process type. For example, CO and/or HCOO- were produced with high TON and selectivity in homogeneous (entries 1-8,

Table 2) and heterogeneous (entries 9-13,

Table 2) systems. The results suggest that the product selectivity is probably influenced by the reaction conditions (Cat, PS, SD, solvent).

In a typical breakaway from the conventional Ru (II) based PS, a heteroleptic osmium(II) complex (OS) with two different tridentate ligands was utilized as a PS in the presence of BI(OH)H, to reduce CO2 to CO and HCOO- at λ>700 nm (entry 8,

Table 2). Since the excited Os complex (Os*) can be reductively quenched by BI(OH)H, Os shows strong potential as a panchromatic photosensitizer, exhibiting an extended excited-state lifetime that enhances HCOO⁻ production [

17]. However, in photocatalytic systems, light absorption by co-existing components such as catalysts or substrates often results in side reactions and inner-filter effects, decreasing photocatalytic efficiency by inhibiting light absorption by the PS [

18]Therefore, developing panchromatic redox PS capable of absorbing longer-wavelength light is crucial.

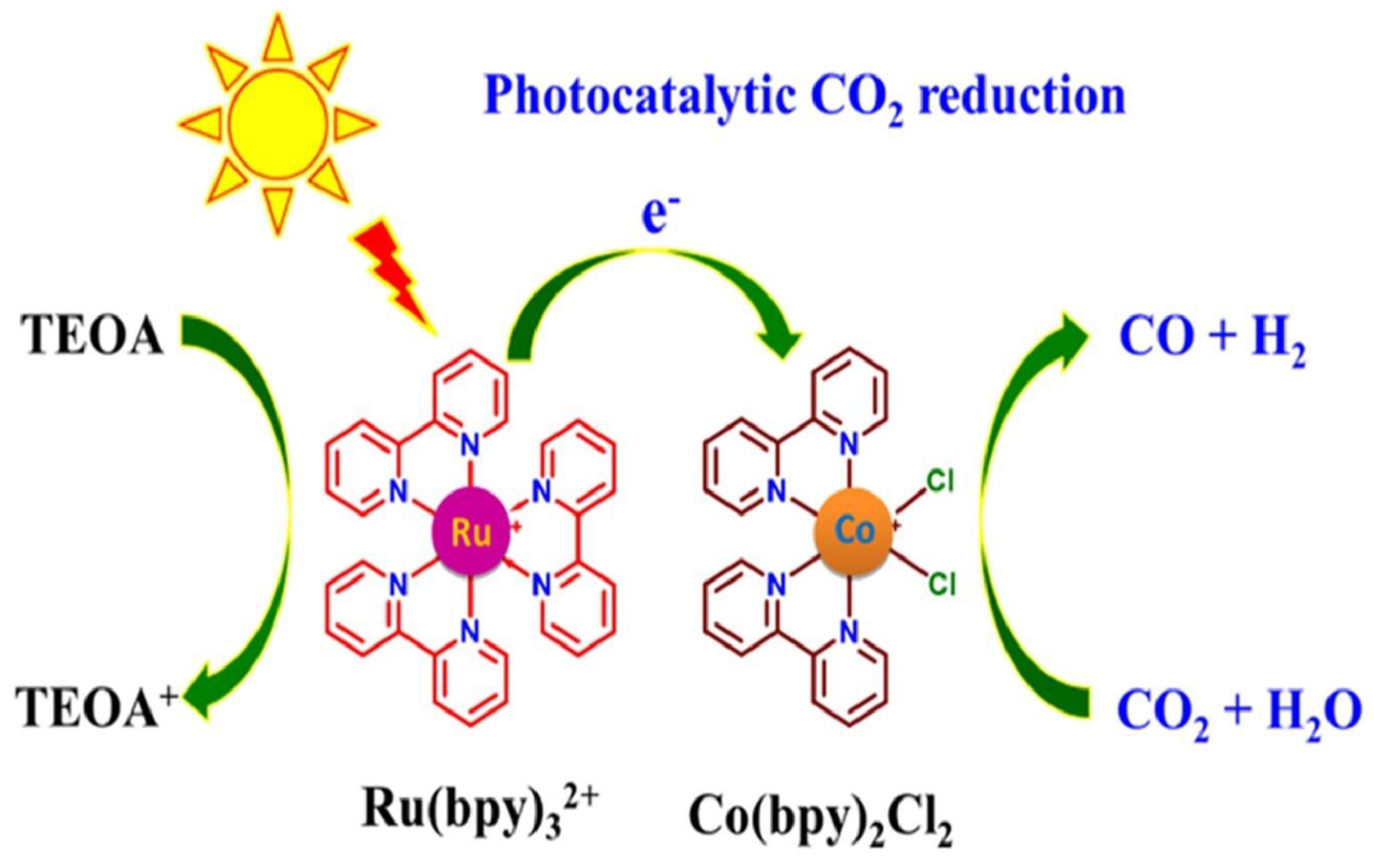

While CO and HCOO⁻ were the main CO₂ reduction products in most photocatalytic systems, syngas (CO/H₂) was produced in some cases with high TON (entries 3, 4,

Table 2). In the latter, syngas was produced from both pure and diluted CO₂ using mononuclear [Co(btz)

2(H

2O)

4]∙6H

2O

(1) and pentanuclear [Co

5(btz)

6(NO

3)

4(H

2O)

4]

(2) Co(II) complexes. Complex (2) exhibited higher reactivity and stability than complex (1), with a broad H₂/CO ratio tunability ranging from 16:1 to 2:1[

34]. The durable and efficient performance of complex (2) could be attributed to its multinuclear structure and the low energy barrier for the photocatalytic intermediate, while the gradual decline in catalytic activity was probably caused by the photodegradation of [Ru(bpy)₃]Cl₂. A high turnover frequency (TOF) of 103/h for CO and 32/h for H₂ was achieved, outperforming most metal–oxygen cluster-based complexes under similar conditions [

34]. The proposed mechanism of formation of syngas gas is illustrated in

Figure 7.

A single-state electron transfer quenching pathway was proposed whereby after photoexcitation PS forms PS*, which undergoes oxidative quenching by Co(bpy)₂Cl₂, generating a Co⁰ substrate. The Co⁰ then binds CO₂ forming a Co⁰–CO₂ adduct, which is protonated to produce CO and H₂O, regenerating Co(bpy)₂²⁺. The oxidized PS (PS⁺) is then reduced by TEOA, completing the catalytic cycle (

Figure 7). The mechanism correlates with the reported Cyclic Voltammetry data, where catalytic current showed only after the second reduction wave [

33,

34]. To overcome the limitations of PS/Cat-mixed systems, a more effective approach involves dyads or hybrid/ supramolecular complexes that integrate both functions of PS and Cat within a single framework. These self-photosensitizing catalysts have gained significant attention, particularly for eliminating the need for external electron transfer [

8].

4.6.2. Dyad CO2 reduction systems

In self-photosensitizing catalytic systems, performance of molecular complexes for CO

2 reduction has been shown to depend on the nature of the bridging ligand that connects the PS to the catalytic unit [

39]. Hence, it is not surprising that recent research focus on catalytic performance has shifted towards developing new and improving or modifying the ligand structure of photocatalysts. To that effect, several dyad systems have been investigated for photocatalytic CO

2 reduction under visible light as shown in

Table 3.

While dimers have been highly effective in CO₂ reduction (entries 5, 6, 7), a new class of dyad systems encompassing Ru-pincer complexes as effective reductive units for CO₂ conversion has emerged in recent years. The pincer-based photocatalysts have demonstrated high selectivity and TON under mild conditions (entries 2, 3, 4,

Table 3). Notably, incorporating phenyl groups and a bpy coligand into the NHC ligand of the CNC pincer framework (entry 3,

Table 3) enhanced CO₂ photoreduction efficiency [

42]. The increased TON at low concentrations is probably due to greater photon availability, while the decrease at higher concentrations may result from reduced light transmittance and photoactivity.

In a similar study, a shift from traditional α-diimine ligands such as cis-[Ru(bpy)₂(CO)₂]²⁺ to non-diimine complexes was demonstrated in entry 2 (

Table 3), where the Ru(II) catalyst was supported by N,N′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-2,6-diaminopyridine (PNP) ligands instead of the [Ru(bpy)₂(CO)₂]²⁺ complex, forming a PNP pincer. Paired with [Ru(bpy)₃]

2+as the PS, the pincer achieved 100% selectivity for HCOO⁻ using TEOA as the donor (entry 2,

Table 3). Pincer-supported Ru complexes have an electron-rich π-conjugated system (26e-) around the metal center, promoting excellent activity and selectivity for CO₂ reduction [

43]. However, photodecomposition of [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺ occurred in aqueous BNAH systems, whereby the byproducts promoted CO₂-to-HCOO⁻ conversion, as previously explained [

41]. This was mitigated by switching to anhydrous solvents (entry 2, 3, 4

Table 3).

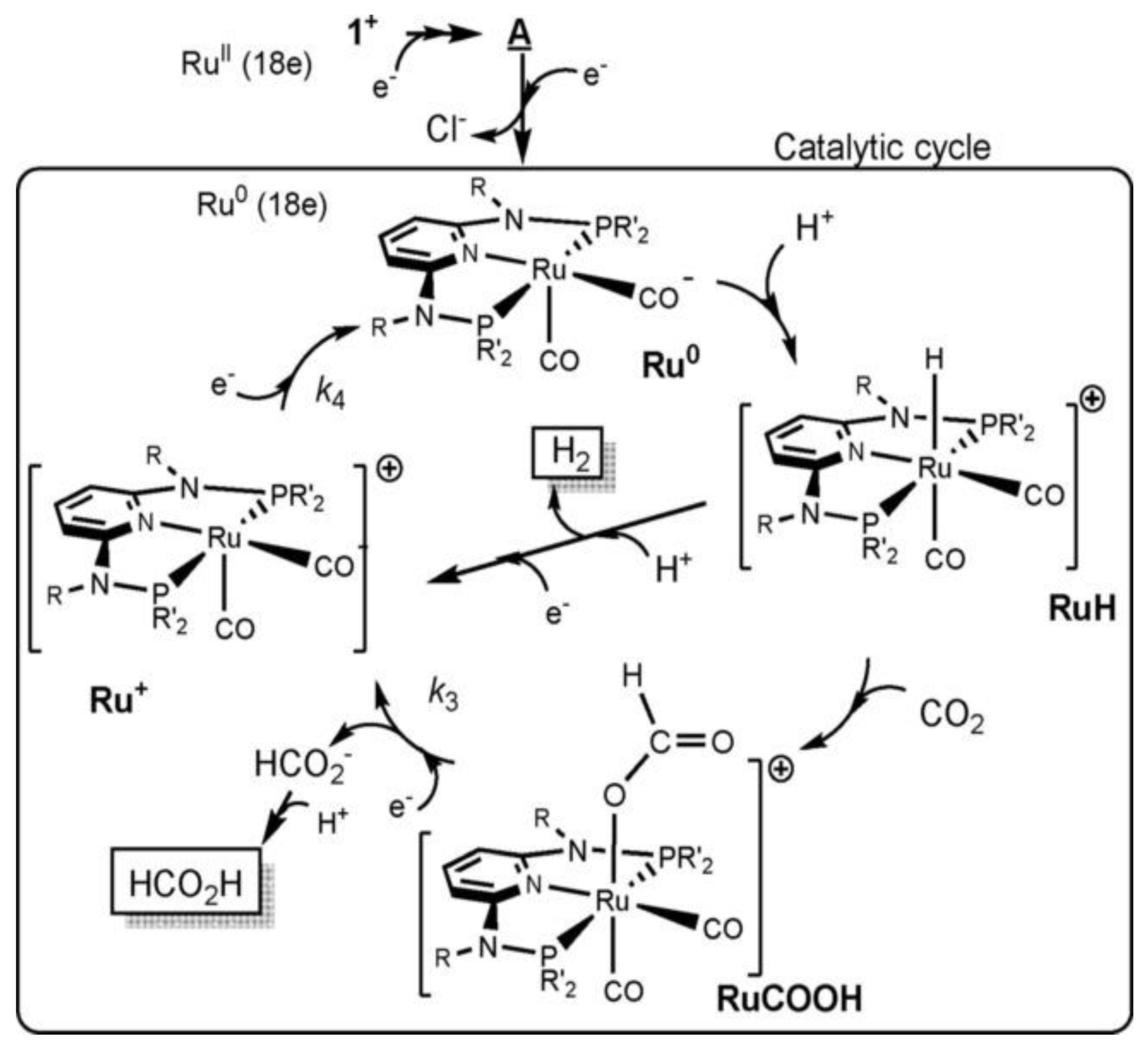

Figure 8 depicts a plausible mechanism for CO

2 photoreduction using a Ru-pincer complex.

The photocatalytic cycle starts with the reduction of the cationic complex A, which spontaneously loses a Cl⁻ to form a square-pyramidal Ru⁰ species (

Figure 8). The subsequent protonation of Ru⁰ generates the hydride complex Ru–H, which undergoes CO₂ insertion to produce a Ru–COOH intermediate. Upon reduction, the intermediate yields formate and forms Ru⁺, which is then reduced by the PS, regenerating Ru⁰ and completing the cycle. The liberation of H₂ may result from further protonation of Ru–H, dimerization of hydrides, or dehydration of HCOOH (

Figure 8). Noteworthy, protonation of Ru–H is difficult to suppress and provides a competing pathway to H₂ evolution, acting as a shortcut in the catalytic cycle [

41].

4.6.3. Hybrid/Supramolecular Catalyst Systems

Table 4 summarizes CO

2 reduction systems employing Ru (II) based hybrid/supramolecular photocatalysts.

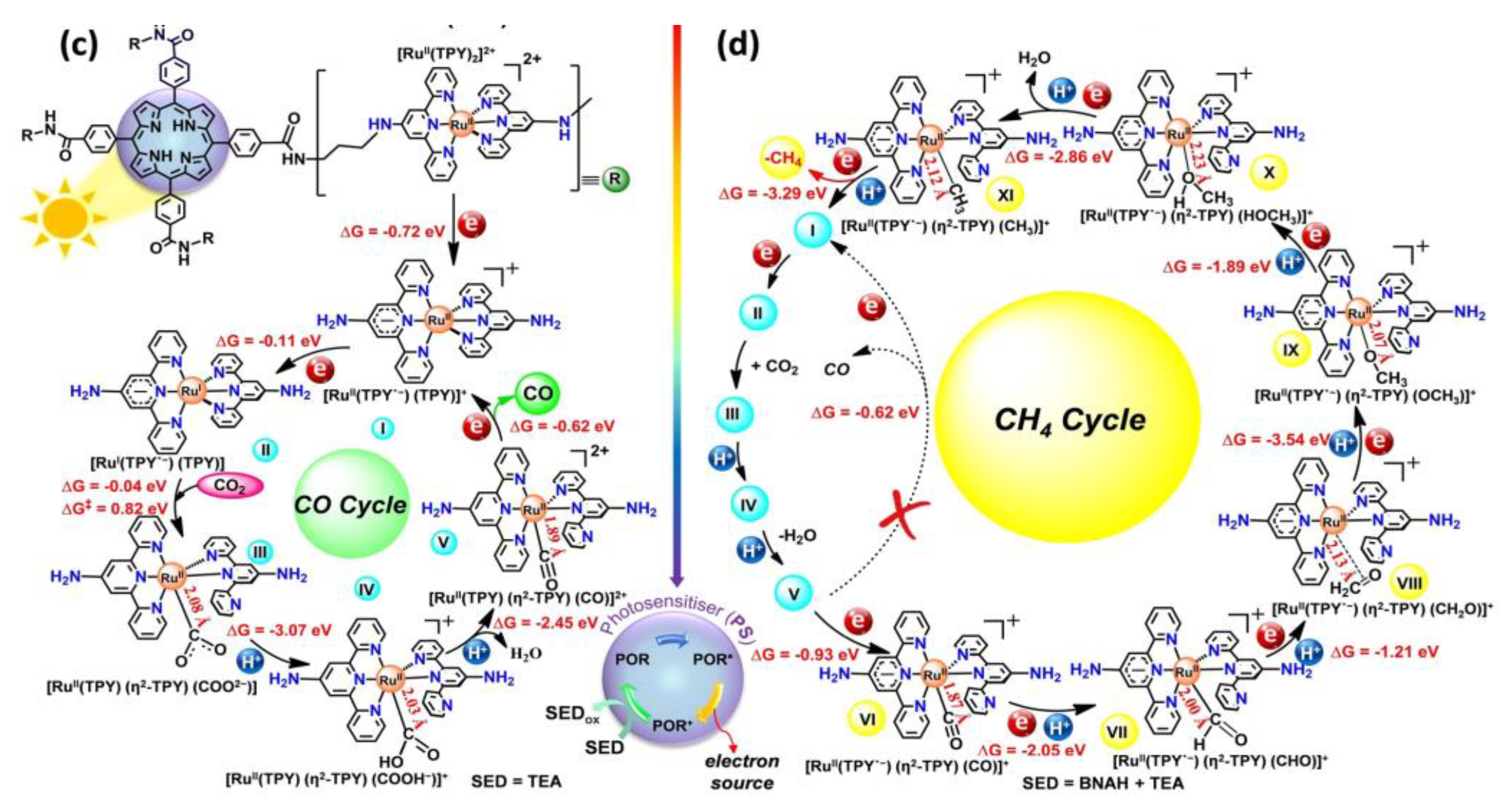

Table 4 shows that supramolecular systems are very effective in CO

2 photoreduction, with high TON and almost 100% product selectivity. For example, the supramolecular coordination polymer gel (CPG) with Ru(II), and porphyrin-based tetrapodal gelator (TPY-POR) units (Ru-TPY-POR-CPG ) achieved >99% selectivity for CO using TEA as a donor, while more than 95% selectivity for methane was obtained when TEA was replaced with BNAH. (entry 12,

Table 4). In this system, the POR acts as the PS, while covalently attached [Ru(TPY)₂]²⁺ serves as the Cat. The functionalization of POR core with four TPY moieties through the alkyl amide chain allows for additional metal-binding which acts as a catalytic site for CO

2 reduction. Additionally, BNAH’s lower oxidation potential (E°ₒₓ = 0.57 V vs. SCE) compared to TEA (0.69 V), may have supported the donor to be more readily oxidized, facilitating faster charge transfer during photoreduction [

61]. Verma and colleagues proposed a possible pathway for CO₂ conversion into methane using the supramolecular catalyst Ru-TPY-POR CPG, as shown in

Figure 9.

Noteworthy, only the CH

4 cycle will be discussed since CO production follows a similar pathway as already discussed for other systems. Thus, in the presence of BNAH the conversion of CO into CH

4 follows a series of proton-coupled electron transfer steps (VII to X) (

Figure 9). The steps result in the formation of key intermediates, including Ru–CH₂O, Ru–OCH₃, and Ru–CH₃, with progressively favorable free energy changes (ΔG = –1.21 to –3.54 eV). The final intermediate, Ru–CH₃, generates CH₄ via a highly exothermic step (ΔG = –3.29 eV), regenerating the active Ru catalyst and completing the cycle. The outlined pathway demonstrates the crucial role of BNAH in facilitating efficient methane formation under visible light [

54]

While typical CO

2 photoreduction conditions were employed in most studies, Zhang and colleagues, [

46] explored a different approach to synthesize CH

4. Using the hybrid catalyst, Ru−H bipyridine complexes-grafted TiO

2 nanohybrids, CH

4 was produced from CO

2 via CO

2 methanation with H

2 acting as a proton and electron donor in the absence of a photosensitizer (entry 1,

Table 4). Ligand exchange of surface Cp–RuH complexes with 4,4′-dimethyl-2,2′-bipyridine (4,4′-bpy) significantly enhanced CO₂ methanation, increasing selectivity and reaction rate to 93.4% and 241 μL·g⁻¹·h⁻¹, respectively. The CO₂•⁻ radicals, produced at TiO₂ oxygen vacancies, reacted with Ru–H to form Ru–OOCH intermediates, consequently producing CH₄ and H₂O in the presence of H₂. Selective CH₄ production relies on directional proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) to CO₂, stabilizing intermediates such as H₂COO*, HCOO*, and H₂CO*[

47].

MOFs have also been utilized in supramolecular catalyitic systems. In

Table 3, entry 10, MOF-253-Ru(dcbpy)₂ acts as a bifunctional photocatalyst, facilitating simultaneous CO₂ reduction to CO and HCOO-, and semidehydrogenation of THIQ to 3,4-dihydroisoquinoline (DHIQ) [

53]. The supramolecular catalyst exhibits superior performance than the Ru-doped MOF-253 (Ru-MOF-253), illustrating the benefits of using open coordination sites for fabricating surface-supported frameworks. The study highlights the potential of MOFs as building blocks for multifunctional heterogeneous photoreduction systems, enabling a green and cost-effective pathway for parallel CO₂ photoreduction and selective organic transformations.

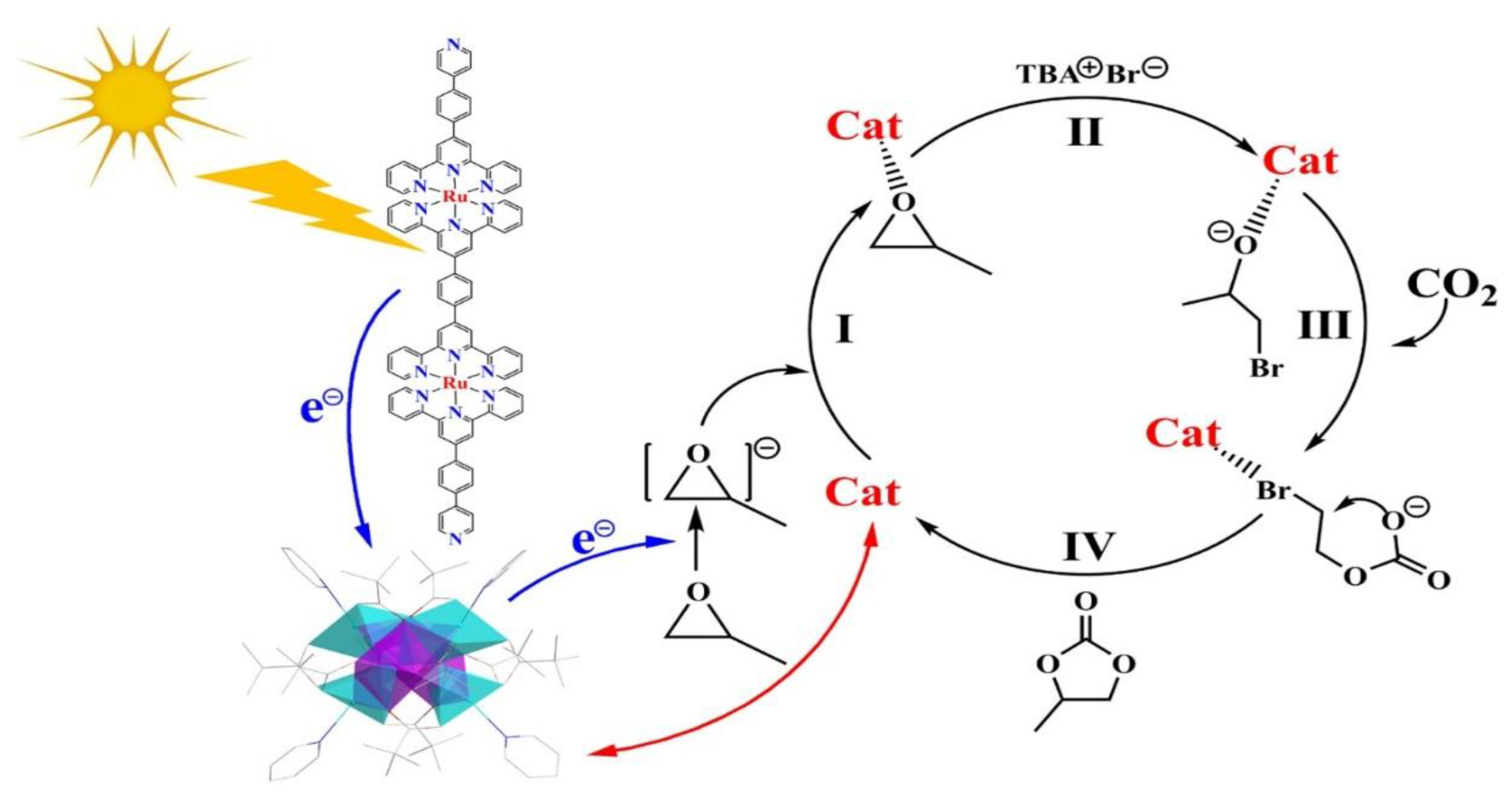

In a recent study, an alternative light-driven CO₂ conversion approach was presented using cycloaddition with an epoxide cocatalyst (entry 5,

Table 4) . The reaction produces cyclic carbonates instead of conventional organic fuels (entry 5,

Table 4), which is an intriguing deviation from typical CO

2 photoreduction methods. The RuPyL₂/Mn₂Ni₄ photocatalytic complex with coordination synergism, achieved very high catalytic activity under mild conditions, with a CO₂ cycloaddition conversion rate of ~99% and a TON of 1723 compared to single Mn₂Ni₄ catalyst (TON = 656) [

30]. Figure. 10 displays the proposed CO

2 cycloaddition pathway.

A possible reaction pathway with coordination synergism was suggested for the CO₂ cycloaddition reaction using RuPyL₂/Mn₂Ni₄ (

Figure 10). Upon light exposure, RuPyL₂/Mn₂Ni₄ promotes electron transfer to the epoxide, activating the molecule through coordination interactions. This is followed by a nucleophilic attack and opening of the epoxy ring. Subsequently, the oxygen anion from the ring-opening intermediate attacks CO₂, producing a bromocarbonate intermediate [

30]

4.6.4. Artificial Photosynthesis Systems

Mimicking natural photosynthesis using metal molecular complexes presents a promising strategy to overcome the high energy barrier of CO₂ reduction and advance next-generation renewable energy solutions. Artificial photosynthetic systems typically integrate a chromophore or PS for light absorption and charge separation with a catalytic center capable of facilitating multielectron CO₂ reduction [

5]. Analogous to natural photosynthesis in plants, CO₂ is reduced by electrons and protons, often derived from water, resulting in the generation of oxygen (O

2) and energy rich-chemical products, all under ambient temperature and pressure [

5,

57]. Some examples of artificial photosynthesis systems used for the photocatalytic conversion of CO

2 are given in

Table 5

While highly efficient and selective molecular systems have been reported in organic media [

62], achieving photocatalytic CO₂ reduction in aqueous media is more appealing for practical applications due to easier handling and coordination with artificial photosynthesis objectives. This perspective is reflected in

Table 5, where most of the studies focused on artificial photosynthetic systems in aqueous media. Entry 3, (

Table 5) demonstrates artificial photosynthetic conversion of CO

2 into methanol using water as the sacrificial electron donor. The proposed mechanism for this reaction is displayed in

Figure 11.

In the hybrid catalyst, RuSA–mC₃N₄, Ru atoms are anchored via Ru–C/N and possibly Ru–O bonds. During aqueous CO₂-to-HCOO- reduction with water as the electron donor, these coordination sites may bridge electron transfer and increase charge density on Ru, reducing the photocarrier transfer barrier and enhancing photocatalytic efficiency. Although the role of Ru–O moieties remain unclear, the atomic dispersion of Ru strengthens Ru–C/N interactions, promoting charge separation and suppressing electron–hole recombination. Consequently, RuSA–mC₃N₄ shows improved photocatalytic activity compared to pristine C₃N₄ [

60]

Noteworthy, in aqueous systems, water can act as the electron donor, enabling net energy production. However, the proton (H+)-rich environment poses a major setback, as it facilitates competitive H+ reduction, often resulting in H

2 generation instead of CO [

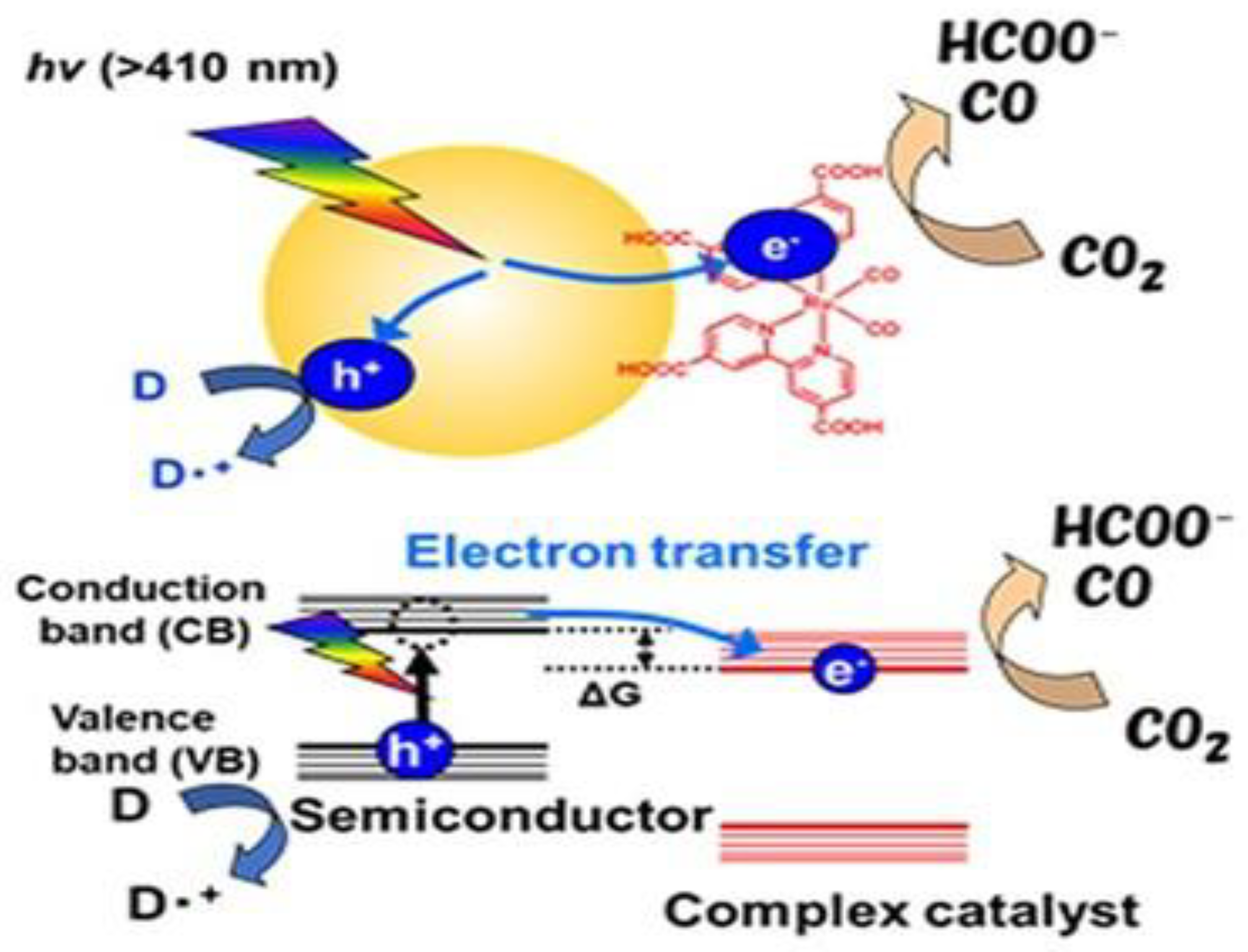

57]. To address this challenge, semiconductor-based molecular catalysts have been employed to promote CO₂ photoreduction, with their band gaps and energy levels adjustable through crystal structure, elemental composition, and ligand ratios. In particular, Ru complexes with bpy ligands have demonstrated promising CO₂ reduction efficiency when integrated into various semiconductors, including doped tantalum oxide (Ta₂O₅), paving the way for more efficient and selective aqueous-phase systems.

A recent innovative advancement in semiconductor-based molecular CO₂ photoreduction was reported by Morikawa et al. [

57], who developed a monolithic “artificial leaf” by integrating N-Ta₂O₅ with [Ru(dcbpy)₂(CO)₂]²⁺ (entry 4,

Table 5). Leveraging the low overpotential of CO₂ reduction at metal complexes, this single-device system efficiently produces formate from CO₂ and H₂O in a membrane-free, bias-free reactor, achieving a solar-to-chemical conversion efficiency of 4.6%, surpassing that of natural photosynthesis. The CO₂ reduction rate increased with the number of dicarboxylic acid anchors, attributed to enhanced electron transfer from the conduction band of N-Ta₂O₅ to the Ru complex. Due to stronger nonadiabatic coupling, the COOH anchoring groups facilitate faster electron transfer (7.5 ps) than PO₃H₂ groups (56.7 ps), highlighting the importance of anchoring group selection in optimizing the performance of CO₂ photoreduction systems [

57]. Figureure. 11 illustrates a typical energy level diagram of hybrid photocatalysis with a semiconductor and a metal-complex photocatalyst

Figure 11.

Ideal energy diagram of hybrid photocatalysis under visible light with a semiconductor and a metal-complex catalyst (adopted from [

57]).

Figure 11.

Ideal energy diagram of hybrid photocatalysis under visible light with a semiconductor and a metal-complex catalyst (adopted from [

57]).

Upon irradiation, the semiconductor generates charge carriers, electrons/holes (e⁻/h⁺). The photoexcited electrons migrate from the semiconductor CB to the metal complex for selective CO₂ reduction at the metal-complex catalyst (Figure. 11). The CB electrons drive the CO₂ reduction reaction, while the photogenerated holes are neutralized by an electron donor (ED) [

57]. Efficient electron transfer requires that the CB minimum of the semiconductor is more negative than the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the metal complex or its CO₂ reduction potential.

The problem of competing H₂ evolution in aqueous media has also been reported in conjugated polymer photocatalysts, where residual palladium from synthesis can further promote proton reduction. Thus, redirecting highly active polymer photocatalysts toward CO₂ reduction instead of proton reduction remains a key yet unresolved challenge. In their attempt to provide a solution, Sakakibara et al. [

61] developed a supramolecular photocatalyst (RuRu′/Ag/P10), comprising a Ag-loaded conjugated polymer and a binuclear Ru(II) complex. This system displayed high catalytic activity and durability for formate production (entry 7,

Table 5). While residual Pd in the polymer supported H₂ evolution in aqueous media, Ag nanoparticle loading enhanced CO₂ reduction selectivity by effectively suppressing H₂ generation. Functioning as a semiconductor, the RuRu′/Ag/P10 framework facilitates sequential visible-light photoexcitation, boosting oxidation power and enabling the use of mild reductants such as water. Mimicking a Z-scheme in natural photosynthesis, the system drives selective CO₂ reduction via an efficient electron cascade [

61].

5. Effect of Parameters

Ru(II) complexes can convert CO2 into CO, HCOO⁻, or CH₄, with product distribution and selectivity strongly influenced by the ligand environment and reaction conditions.

5.1. Effect of Donors

Recent reports demonstrated that selectivity and efficiency of the CO

2 photoreduction could be modulated with electron donors [

60]. Several authors have investigated the effect of sacrificial donors on CO

2 photoreduction with varying results [

41,

61,

63]. Most recently, Sakakibara et al. [

61] investigated the effect of MeCN and different electron donors on CO₂ reduction using the RuRu′/Ag/P10 system under 5 hours of visible light irradiation (entry 7,

Table 5). Among the tested SDs, TEA in H₂O/MeCN exhibited the highest formate yield, TON, and selectivity, implying optimal electron transfer and catalyst activity. In contrast, TEOA and ASc showed moderate to low formate yield, while no CO₂ reduction products were observed with EDTA·2Na in the absence of MeCN. TEA in MeCN/H

2O emerged as the most effective condition, which contradicts earlier findings by Hammed et al. [

41] using a PNP pincer system. In the latter, substituting DMF with MeCN reduced activity, while other donors such as ASc, NaASc, and TEA showed poor performance. Overall, the results suggest that the SD type and solvent environment have a significant effect on the efficiency and selectivity of CO₂ photoreduction, highlighting the importance of controlling these factors to suppress competitive H₂ evolution and enhance formate selectivity.

In another study, the homobimetallic Cu and Co bisquaterpyridine catalysts paired with Ru(phen)₃²⁺ showed that full catalytic performance was only achieved with a specific combination of BIH, TEOA, and H₂O. In contrast, monometallic systems were less effective, highlighting the importance of cooperative metal centers for multielectron transfer processes [

22]. Similarly, the Ru-TPY-POR-CPG system achieved variable selectivity, favoring CO in the presence of TEA and shifting to CH₄ with BNAH [

53]. The contrast in product distribution can be explained by the oxidation potentials of the donors, with BNAH enabling faster electron transfer and deeper reduction pathways. While the Co (II) complexes and the CPG frameworks benefit from well-designed ligand environments and sacrificial donors, the CPG system additionally leverages structural integration and supramolecular assembly for improved charge separation and metal site availability. These results align with the afore mentioned findings of [

60], demonstrating the pivotal role of catalyst structure, PS, and ED in determining the efficiency and product selectivity of CO₂ photoreduction.

5.2. Effect of solvent

The reaction medium critically influences the efficiency and product distribution in CO₂ photoreduction. Solvent properties can lower the activation energy for CO₂ reduction and affect selectivity by modulating the adsorption of the CO₂⁻ intermediate on catalyst surfaces [

65]. In low-polarity solvents, CO₂⁻ binds more strongly via the carbon atom, favoring CO and formate production [

65]. High-dielectric solvents, however, better stabilize CO₂⁻ through solvation, weakening its catalyst interaction and promoting formate production. In metal-based systems, solvent characteristics also govern the formation and stability of M-CO₂⁻ intermediates, further emphasizing their role in shaping catalytic pathways.

Table 6 summarizes findings by [

62] on solvent effects during 2 h of visible-light-driven CO₂ reduction.

As shown in

Table 6, photocatalytic CO₂ reduction is highly influenced by the reaction solvent. Aprotic solvents such as MeCN and DMF promote higher CO production, with yields correlating closely to CO₂ solubility rather than solvent viscosity. However, the MeCN results contradict the later findings of Sakakibara et al. [

61], where the removal of MeCN from the MeCN/TEOA/H₂O solution was found to enhance CO production, presumably due to improved dispersibility of the photosensitizer and increased stability of the Ru complex. On the other hand, DMSO and H

2O show poor performance due to low CO₂ solubility or unfavorable coordination environments. Notably, THF achieves the highest CO selectivity (90.5%) despite moderate CO yield, possibly due to its strong coordination ability with the Co-bpy complex. These results emphasize the important role of solvent viscosity and CO₂ solubility in boosting product yield and suppressing competing H₂ evolution. However, in a recent study, Das et al. [

65] cautioned that organic solvents such as ethyl acetate (EtOAc), CH₃CN, TEOA and TEA can undergo photolysis upon UV-Visible light exposure, producing CO, CH₄, C₂H₄, and H₂ even without a catalyst [

65]. This may result in overstated catalyst performance and product selectivity. Therefore, careful selection of solvents and SDs is crucial to avoid misinterpretation in photocatalytic CO₂ reduction studies.

5.3. Effect of Substituents Groups/Ligands

Catalytic activity in CO₂ photoreduction strongly depends on the catalyst’s structure, particularly the coordination environment of the metal center [

35] . Improving performance requires strategic selection and modification of metal centers and ligands, as structural changes to primary ligands affect the properties and efficiency of metal complexes. In their related studies, Kuramochi et al. [

10,

40] reported that TOFs were significantly affected by the type and position of amide groups and other substituents on the bipyridyl ligand in trans-(Cl)-[Ru(bpy)(CO)₂Cl₂]-type complexes. Despite differences in hydrophilicity and molecular size, reaction rates correlated consistently with the first reduction potential, offering a useful design strategy for Ru-based catalysts. Furthermore, the molecular ratio of Ru(PS) to Ru(Cat) influenced product selectivity between CO and HCOO⁻. Similar findings were reported in other studies [

26,

63].

Additionally, in metal-based CO₂ reduction systems, the adsorption strength of CO₂⁻ on the catalyst surface has a profound effect on product selectivity. For example, HCOO- is the major product in the RuC/mpg-C₃N₄ (mpg-C₃N₄: mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride; C: COOH) or RuP/mpg-C₃N₄ systems (P: PO₃H₂), regardless of Ru(II) complex loading or solvent. On the contrary, CO selectivity increased markedly (40–70%) when mpg-C₃N₄ loaded with higher amounts of RuCP (CP: CH₂CH₂PO₃H₂) was used in solvents with high donor numbers (i.e., DMA, DMF, DMSO) and TEOA as the electron donor [

63]. The latter indicates that substrate concentration affects process reactivity, which agrees with the earlier findings of Kuramochi et al. [

11]. The effect of ligand substituents was further demonstrated using dinuclear [

26] nickel(II)-bipyridine [

66], and cobalt (II) tripodal complexes [

35].

On the other hand, Hameed et al. [

20] showed that the choice of metal center has a significant influence on product distribution in CO₂ reduction. Bidentate N-(diphenylphosphino)-2-aminopyridine ligands ({Ph₂PNR}NC₅H₄; R = H, CH₃) were studied with Re(I) and Mn(I) complexes in DMF using [Ru(bpy)₃](PF₆)₂ PS and TEOA donor under visible light. The Mn complex ([Mn{κ²-(Ph₂P)NH-(NC₅H₄)}(CO)₃Br],

(1) produced CO with a TON of 55, >99% selectivity, and an AQY of 0.75. Replacing Mn with Re (complex (2)) shifted the product to HCOOH with a TON of 343, >96% selectivity, and an AQY of 4.7. This shift in reactivity demonstrates the critical role of CO₂ coordination: in complex (1), CO₂ probably binds via carbon, resulting in O-protonation and CO formation, whereas in complex (2), O-bound CO₂ undergoes C-protonation, favoring HCOOH production. Br- addition further increased TON, supporting the hypothesis that Br⁻ remains coordinated after the second electron transfer, facilitating CO or HCOOH generation [

20]

The effect of Lewis acids on visible-light-driven CO₂ reduction have also been investigated in a previous study using Ni(II) complexes with pyridine pendants [

32]. The enhanced selective CO generation was probably due to the formation of a Mg²⁺-bound Ni complex, which strengthened cooperative interactions between the Ni and Mg centers, with the Lewis acidic Mg²⁺ stabilizing the Ni-CO₂ intermediate [

32].

6. Limitations and Perspectives

Ru(II)-based molecular photocatalysts for CO₂ reduction have made great strides in recent years, but a number of drawbacks still prevent widespread use. The instability of essential components, such as the Cat and PS, is a major problem, particularly in mixed systems where diffusion limitations restrict electron transfer because of the physical separation of PS and Cat. Catalytic turnover and overall efficiency are also compromised by the PS's proneness to deterioration in both its excited and reduced states. Long-term stability and recyclability are further restricted by catalyst deactivation via photolysis, precipitation (such as the polymerization of Ru(CO) into inactive species), or ligand dissociation. For example, it has been demonstrated that [Ru(CO)]ₙ aggregates prevent effective electron transfer from the PS, requiring the use of SDs and extra PS.

The choice of solvent and SDs is another crucial factor. Even without a catalyst, organic solvents like MeCN and EtOAc and EDs like TEOA and TEA can undergo photo decomposition under UV-visible light to produce CO, CH₄, or H₂. This could lead to overstated product selectivity and catalyst efficiency. Furthermore, the production and stability of M-CO₂ intermediates are directly affected by the solvent's dielectric characteristics and CO₂ solubility, impacting both the reaction rate and product selectivity. The limited product selectivity of many systems, often requires subtle modifications to the ligand structure, SD type and metal coordination. While CO and HCOO- are major products, further reduction to other hydrocarbons such as CH₄ remains challenging and often necessitates careful reaction parameter control.

Although dyad and supramolecular catalysts provide enhanced electron transfer through intramolecular pathways, their development can be complex and expensive from a design standpoint. Additionally, high selectivity toward CO₂ reduction products is impeded by competitive side reactions such as H₂ evolution, which are more prevalent in aqueous conditions.

Developing more resilient and scalable systems in the future will necessitate: (i) designing Cat and PS units with improved photochemical and electrochemical stability; (ii) designing ligand assemblies that facilitate effective and selective multi-electron transfer; (iii) implementing SDs that are photostable and water-tolerant; and (iv) investigating earth-abundant metal alternatives to minimize costs and increase sustainability. New approaches that could speed up these initiatives and assist in overcoming present obstacles in photocatalytic CO₂ conversion include single-site hybrid photocatalysts, nanostructured supports, and machine learning-driven molecular designs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, Pauline Ncube; review and editing, Mokgaotsa Jonas Mochane.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the University of South Africa (UNISA). In particular, the Department of Chemistry.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, P.; Aathira, M.S.; Singh, D.P.; Behera, B.; Jain, S.L. A Bridged Ruthenium Dimer (Ru–Ru) for Photoreduction of CO2 under Visible Light Irradiation. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2018, 61, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Chen, W.; Shan, G.G.; Li, G.; Sun, C.; Wang, X.L.; Su, Z. The Roles of Polyoxometalates in Photocatalytic Reduction of Carbon Dioxide. Mater Today Energy 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriki, R.; Maeda, K. Development of Hybrid Photocatalysts Constructed with a Metal Complex and Graphitic Carbon Nitride for Visible-Light-Driven CO2 Reduction. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2017, 19, 4938–4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Fang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, D. High-Efficiency g-C3N4 Based Photocatalysts for CO2 Reduction: Modification Methods. Advanced Fiber Materials 2022, 4, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, S.; Takayama, T.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Iwase, A.; Kudo, A. CO2 Reduction Using Water as an Electron Donor over Heterogeneous Photocatalysts Aiming at Artificial Photosynthesis. Acc Chem Res 2022, 55, 966–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, M.; Basu, S.; Shetti, N.P.; Nadagouda, M.N.; Kwon, E.E.; Park, Y.K.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Photocatalytic Carbon Dioxide Reduction: Exploring the Role of Ultrathin 2D Graphitic Carbon Nitride (g-C3N4). Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S.; Srivastava, R. Catalytic Conversion of CO2 to Chemicals and Fuels: The Collective Thermocatalytic/Photocatalytic/Electrocatalytic Approach with Graphitic Carbon Nitride. Mater Adv 2020, 1, 1506–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K. Metal-Complex/Semiconductor Hybrid Photocatalysts and Photoelectrodes for CO2 Reduction Driven by Visible Light. Advanced Materials 2019, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirzada, B.M.; Dar, A.H.; Shaikh, M.N.; Qurashi, A. Reticular-Chemistry-Inspired Supramolecule Design as a Tool to Achieve Efficient Photocatalysts for CO2 Reduction. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 29291–29324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, L.; Chen, G.; Robert, M.; Lau, T.C. Electrocatalytic and Photocatalytic Reduction of Carbon Dioxide by Earth-Abundant Bimetallic Molecular Catalysts. ChemPhysChem 2021, 22, 1835–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuramochi, Y.; Itabashi, J.; Toyama, M.; Ishida, H. Photochemical CO2 Reduction Catalyzed by Trans(Cl)-[Ru(2,2′-Bipyridine)(CO)2Cl2] Bearing Two Methyl Groups at 4,4′-, 5,5′- or 6,6′-Positions in the Ligand. ChemPhotoChem 2018, 2, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancelliere, A.M.; Puntoriero, F.; Serroni, S.; Campagna, S.; Tamaki, Y.; Saito, D.; Ishitani, O. Efficient Trinuclear Ru(Ii)-Re(i) Supramolecular Photocatalysts for CO2 Reduction Based on a New Tris-Chelating Bridging Ligand Built around a Central Aromatic Ring. Chem Sci 2020, 11, 1556–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, Y.; Ishitani, O. Synthesis of Os(II)-Re(i)-Ru(II) Hetero-Trinuclear Complexes and Their Photophysical Properties and Photocatalytic Abilities. Chem Sci 2018, 9, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, E.; Grills, D.C.; Manbeck, G.F.; Polyansky, D.E. Understanding the Role of Inter- and Intramolecular Promoters in Electro- and Photochemical CO2 Reduction Using Mn, Re, and Ru Catalysts. Acc Chem Res 2022, 55, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampaio, R.N.; Grills, D.C.; Polyansky, D.E.; Szalda, D.J.; Fujita, E. Unexpected Roles of Triethanolamine in the Photochemical Reduction of CO2 to Formate by Ruthenium Complexes. J Am Chem Soc 2020, 142, 2413–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumagai, H.; Tamaki, Y.; Ishitani, O. Photocatalytic Systems for CO2 Reduction: Metal-Complex Photocatalysts and Their Hybrids with Photofunctional Solid Materials. Acc Chem Res 2022, 55, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irikura, M.; Tamaki, Y.; Ishitani, O. Development of a Panchromatic Photosensitizer and Its Application to Photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Chem Sci 2021, 12, 13888–13896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Qin, Y.; Hao, M.; Li, Z. MOF-253-Supported Ru Complex for Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction by Coupling with Semidehydrogenation of 1,2,3,4-Tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ). Inorg Chem 2019, 58, 16574–16580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuramochi, Y.; Ishitani, O.; Ishida, H. Reaction Mechanisms of Catalytic Photochemical CO2 Reduction Using Re(I) and Ru(II) Complexes. Coord Chem Rev 2018, 373, 333–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, Y.; Gabidullin, B.; Richeson, D. Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction with Manganese Complexes Bearing a Κ2-PN Ligand: Breaking the α-Diimine Hold on Group 7 Catalysts and Switching Selectivity. Inorg Chem 2018, 57, 13092–13096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.M.; Takayama, T.; Sato, S.; Iwase, A.; Kudo, A.; Morikawa, T. Enhancement of CO2 Reduction Activity under Visible Light Irradiation over Zn-Based Metal Sulfides by Combination with Ru-Complex Catalysts. Appl Catal B 2018, 224, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.M.; Zhang, J.H.; Hou, Y.J.; Wang, H.P.; Pan, M. Visible-Light-Driven CO2 Photo-Catalytic Reduction of Ru(II) and Ir(III) Coordination Complexes. Inorg Chem Commun 2016, 73, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, J.; Chen, L.; Guo, Z.; Cheng, L.; Wellauer, J.; Wenger, O.S.; von Wolff, N.; Lau, K.C.; Lau, T.C.; Chen, G.; et al. Visible-Light-Driven CO2 Reduction with Homobimetallic Complexes. Cooperativity between Metals and Activation of Different Pathways. J Am Chem Soc 2023, 145, 25195–25202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Chen, X.B.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Shi, Z.; Feng, S. Covalent Triazine Framework Featuring Single Electron Co2+ Centered in Intact Porphyrin Units for Efficient CO2 Photoreduction. Appl Surf Sci 2023, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Huang, L.; Peng, J.; Hou, Y.; Ding, Z.; Wang, S. Spinel-Type Mixed Metal Sulfide NiCo2S4 for Efficient Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 with Visible Light. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 5513–5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizuka, T.; Hosokawa, A.; Kawanishi, T.; Kotani, H.; Zhi, Y.; Kojima, T. Self-Photosensitizing Dinuclear Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Reduction to CO. J Am Chem Soc 2023, 145, 23196–23204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, C.; Bai, Y.; Jiang, G.; Li, Z.; Gaponik, N. Boosting Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction on CsPbBr3 Perovskite Nanocrystals by Immobilizing Metal Complexes. Chemistry of Materials 2020, 32, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhao, J.; Chen, H.; Weng, Y.X.; Tang, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, W.; She, Y.; Xia, J.; Li, H. Unique Z-Scheme Carbonized Polymer Dots/Bi4O5Br2 Hybrids for Efficiently Boosting Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Appl Catal B 2021, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Chen, L.; Chao, D. Water-Assisted Highly Efficient Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 to CO with Noble Metal-Free Bis(Terpyridine)Iron(II) Complexes and an Organic Photosensitizer. Inorg Chem 2021, 60, 5590–5597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Du, L.; Gao, H. Coordination Synergy between Metal Nanoclusters and Ruthenium Photosensitizers for Photocatalytic Cycloaddition of CO2 under Mild Conditions. Molecular Catalysis 2025, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Fu, Y.; You, S.; Yang, Y.; Qin, C.; Zhao, L.; Su, Z. Hexanuclear Nickel-Based [P4Mo11O50] with Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 Activity. Inorg Chem Commun 2021, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Kawanishi, T.; Tsukakoshi, Y.; Kotani, H.; Ishizuka, T.; Kojima, T. Efficient Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction by a Ni(II) Complex Having Pyridine Pendants through Capturing a Mg2+ Ion as a Lewis-Acid Cocatalyst. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141, 20309–20317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Ye, L.; Chen, H.; Sun, L. Highly Efficient Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 and H2O to CO and H2 with a Cobalt Bipyridyl Complex. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2018, 27, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Wang, C.; Sun, C.Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.L.; Su, Z.M. Ultra Stable Multinuclear Metal Complexes as Homogeneous Catalysts for Visible-Light Driven Syngas Production from Pure and Diluted CO2. J Catal 2020, 385, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Huang, H.H.; Sun, J.K.; Ouyang, T.; Zhong, D.C.; Lu, T.B. Electrocatalytic and Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 to CO by Cobalt(II) Tripodal Complexes: Low Overpotentials, High Efficiency and Selectivity. ChemSusChem 2018, 11, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, G.; Guo, Z.; Wang, L.; Fan, H.; Robert, M.; Lau, T.C. A Highly Active and Robust Iron Quinquepyridine Complex for Photocatalytic CO2 reduction in Aqueous Acetonitrile Solution. Chemical Communications 2020, 56, 6249–6252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.L.; Liu, H.R.; Wang, S.M.; Guan, G.W.; Yang, Q.Y. Immobilizing Isatin-Schiff Base Complexes in NH2-UiO-66 for Highly Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. ACS Catal 2023, 13, 2547–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Sa, R.; Li, L.; He, Y.; Li, L.; Bi, J.; Zhuang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zou, Z. A Covalent Organic Framework Bearing Single Ni Sites as a Synergistic Photocatalyst for Selective Photoreduction of CO2 to CO. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141, 7615–7621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkubo, K.; Yamazaki, Y.; Nakashima, T.; Tamaki, Y.; Koike, K.; Ishitani, O. Photocatalyses of Ru(II)–Re(I) Binuclear Complexes Connected through Two Ethylene Chains for CO2 Reduction. J Catal 2016, 343, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramochi, Y.; Fukaya, K.; Yoshida, M.; Ishida, H. Trans-(Cl)-[Ru(5,5′-Diamide-2,2′-Bipyridine)(CO)2Cl2]: Synthesis, Structure, and Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction Activity. Chemistry - A European Journal 2015, 21, 10049–10060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, Y.; Rao, G.K.; Ovens, J.S.; Gabidullin, B.; Richeson, D. Visible-Light Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 to Formic Acid with a Ru Catalyst Supported by N,N″-Bis(Diphenylphosphino)-2,6-Diaminopyridine Ligands. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 3453–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Lamb, R.W.; Qu, F.; Reinheimer, E.; Boudreaux, C.M.; Webster, C.E.; Delcamp, J.H.; Papish, E.T. Highly Active Ruthenium CNC Pincer Photocatalysts for Visible-Light-Driven Carbon Dioxide Reduction. Inorg Chem 2019, 58, 8012–8020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Kong, P.; Niu, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, R.; Guo, Y.; Peng, T. Co-Porphyrin/Ru-Pincer Complex Coupled Polymer with Z-Scheme Molecular Junctions and Dual Single-Atom Sites for Visible Light-Responsive CO2 Reduction. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramochi, Y.; Sekine, M.; Kitamura, K.; Maegawa, Y.; Goto, Y.; Shirai, S.; Inagaki, S.; Ishida, H. Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction by Periodic Mesoporous Organosilica (PMO) Containing Two Different Ruthenium Complexes as Photosensitizing and Catalytic Sites. Chemistry - A European Journal 2017, 23, 10301–10309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benseghir, Y.; Solé-Daura, A.; Mialane, P.; Marrot, J.; Dalecky, L.; Béchu, S.; Frégnaux, M.; Gomez-Mingot, M.; Fontecave, M.; Mellot-Draznieks, C.; et al. Understanding the Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 with Heterometallic Molybdenum(V) Phosphate Polyoxometalates in Aqueous Media. ACS Catal 2022, 12, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Sui, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wen, N.; Chen, H.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, R.; et al. Surface Ru-H Bipyridine Complexes-Grafted TiO2 Nanohybrids for Efficient Photocatalytic CO2 Methanation. J Am Chem Soc 2023, 145, 5769–5777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, K.; Zhu, X.; Peng, L.; Fu, Y.; Ma, R.; Lu, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, W.; Fan, M. Boosting Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction over a Covalent Organic Framework Decorated with Ruthenium Nanoparticles. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ananthakrishnan, R. Visible Light-Assisted Reduction of CO2 into Formaldehyde by Heteroleptic Ruthenium Metal Complex-TiO2 Hybrids in an Aqueous Medium. Green Chemistry 2020, 22, 1650–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K.; An, D.; Kuriki, R.; Lu, D.; Ishitani, O. Graphitic Carbon Nitride Prepared from Urea as a Photocatalyst for Visible-Light Carbon Dioxide Reduction with the Aid of a Mononuclear Ruthenium(II) Complex. Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry 2018, 14, 1806–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, D.; Tamaki, Y.; Ishitani, O. Photocatalysis of CO2 Reduction by a Ru(II)-Ru(II) Supramolecular Catalyst Adsorbed on Al2O3. ACS Catal 2023, 13, 4376–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraoka, K.; Uchiyama, T.; Lu, D.; Uchimoto, Y.; Ishitani, O.; Maeda, K. A Visible-Light-Driven Z-Scheme CO2 Reduction System Using Ta3N5 and a Ru(II) Binuclear Complex. Bull Chem Soc Jpn 2019, 92, 124–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, X.; Chang, C.H.; Zhang, T.; Guan, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wen, P.; Tang, I.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Engineering Single Ni Sites on 3D Cage-like Cucurbit[n]Uril Ligands for Efficient and Selective CO2 Photocatalytic Reduction. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elcheikh Mahmoud, M.; Audi, H.; Assoud, A.; Ghaddar, T.H.; Hmadeh, M. Metal-Organic Framework Photocatalyst Incorporating Bis(4′-(4-Carboxyphenyl)-Terpyridine)Ruthenium(II) for Visible-Light-Driven Carbon Dioxide Reduction. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141, 7115–7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, P.; Rahimi, F.A.; Samanta, D.; Kundu, A.; Dasgupta, J.; Maji, T.K. Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction to CO/CH4 Using a Metal–Organic “Soft” Coordination Polymer Gel. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 2022, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Ma, Y.; Xin, X.; Na, H.; Zhao, Y.; Tan, H.; Han, Z.; Li, Y.; Kang, Z. Reduced Polyoxometalates and Bipyridine Ruthenium Complex Forming a Tunable Photocatalytic System for High Efficient CO2 Reduction. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Kim, S.; Eom, Y.K.; Valandro, S.R.; Schanze, K.S. Polymer Chromophore-Catalyst Assembly for Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. ACS Appl Energy Mater 2021, 4, 7030–7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, T.; Sato, S.; Sekizawa, K.; Suzuki, T.M.; Arai, T. Solar-Driven CO2 Reduction Using a Semiconductor/Molecule Hybrid Photosystem: From Photocatalysts to a Monolithic Artificial Leaf. Acc Chem Res 2022, 55, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Li, R.; Yang, J.; Xu, S.; Zhang, C.; You, K.; Ma, B.; Guan, H.; Ding, Y. Hexanuclear Ring Cobalt Complex for Photochemical CO2 to CO Conversion. Chinese Journal of Catalysis 2022, 43, 2414–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Lin, L.; Wang, X. A Perovskite Oxide LaCoO3 Cocatalyst for Efficient Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 with Visible Light. Chemical Communications 2018, 54, 2272–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Kumar, S.; Tomanec, O.; Petr, M.; Zhu Chen, J.; Miller, J.T.; Varma, R.S.; Gawande, M.B.; Zbořil, R. Carbon Nitride-Based Ruthenium Single Atom Photocatalyst for CO2 Reduction to Methanol. Small 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, N.; McQueen, E.; Sprick, R.S.; Ishitani, O. Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction in Aqueous Media Using a Silver-Loaded Conjugated Polymer and a Ru(II)-Ru(II) Supramolecular Photocatalyst. Bull Chem Soc Jpn 2025, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Qin, B.; Zhao, G. Effect of Solvents on Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 Mediated by Cobalt Complex. J Photochem Photobiol A Chem 2018, 354, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriki, R.; Ishitani, O.; Maeda, K. Unique Solvent Effects on Visible-Light CO2 Reduction over Ruthenium(II)-Complex/Carbon Nitride Hybrid Photocatalysts. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2016, 8, 6011–6018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, W.A.; Sanchez Fernandez, E.; Maroto-Valer, M.M. Review and Analysis of CO2 Photoreduction Kinetics. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2020, 8, 4677–4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Chakraborty, S.; Peter, S.C. Systematic Assessment of Solvent Selection in Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. ACS Energy Lett 2021, 6, 3270–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.X.; Chen, Y.M.; Xu, Q.Q.; Mu, W.H. Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2to CO Using Nickel(II)-Bipyridine Complexes with Different Substituent Groups as Catalysts. Journal of CO2 Utilization 2023, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).