1. Introduction

This paper resolves P vs NP by demonstrating that computational complexity is fundamentally a question of structural survival under recursive pressure, not temporal efficiency.

The Clay Mathematics Institute formally defines the problem as follows:

Prove that P = NP or that P ≠ NP. That is, determine whether every problem for which a solution can be verified in polynomial time (NP) can also be solved in polynomial time (P).

Traditionally, this question is approached using the classical Turing machine model. Under this framework, the class P consists of decision problems solvable by a deterministic Turing machine in polynomial time. The class NP consists of decision problems for which a given solution can be verified in polynomial time by a deterministic Turing machine, or equivalently, solvable by a nondeterministic Turing machine in polynomial time. The distinction rests on whether a solution can be efficiently found (P) versus efficiently verified (NP), and whether deterministic algorithms exist to traverse the full solution space without exponential overhead.

This paper introduces an alternative formal framework grounded in recursive motion rather than step-counting time. Problems are represented as recursive structures characterized by directional deviation (), cumulative motion persistence (), and bounded compression thresholds (). Solutions are modeled as compression pathways that must preserve identity across recursive depth without exceeding the collapse boundary defined by .

The central claim is that problems in class NP, when represented in this framework, structurally exceed their survivable compression boundaries under bounded recursive motion. This recursive strain leads to collapse (), thereby rendering bounded compression impossible for general NP instances. As such, the paper proves that by showing that structural survival under recursive pressure fails in all NP-complete configurations.

The P vs NP problem has resisted resolution for over fifty years, despite continuous effort from the global mathematical and theoretical computer science communities. Numerous strategies grounded in algorithmic analysis, circuit complexity, and diagonalization have been explored. However, the field has encountered three dominant barriers that limit the viability of classical resolution pathways.

Relativization: Baker, Gill, and Solovay (1975) showed that techniques that relativize cannot resolve P vs NP. They constructed oracles

A and

B such that

while

, demonstrating that relativizing proof methods yield inconsistent results across oracle-augmented systems [

2].

Natural Proofs: Razborov and Rudich (1997) proved that a large class of “natural” combinatorial proof methods, those that are constructive and useful against a wide class of functions, are incompatible with widely accepted cryptographic assumptions, making them unsuitable for resolving P vs NP [

10].

Algebrization: Aaronson and Wigderson (2008) extended the relativization barrier by introducing the algebrization barrier. They demonstrated that even proof techniques combining algebraic methods with oracle access fail to resolve P vs NP, suggesting the need for non-relativizing, non-algebrizing approaches [

1].

This framework avoids the limitations of these barriers by shifting from a machine-centric model to a structure-centric motion model. Rather than analyzing time-bound transitions on symbolic tapes, this system evaluates the survivability of recursive deviation under compression thresholds. The motion-collapse function defines a hard boundary on recursive expansion. Once the accumulated directional deviation exceeds the polynomial compression threshold , collapse () is triggered. This structural collapse is deterministic and observable, and it provides a falsifiable method for separating P from NP in a non-relativizing domain.

2. Formal Definitions

This section defines the core constructs of the motion-based recursion framework used to resolve the P vs NP problem.

: Directional structural deviation incurred at each recursive step. Represents discrete change in system state between successive layers of computation.

: Total accumulated deviation across all recursive layers. Represents the aggregate motion over a complete solution pathway.

: Recursive strain, defined as the second-order change in directional motion. Measures how rapidly structural deviation accelerates within the recursive process.

: Compression threshold. The maximum allowable value of beyond which the recursive structure becomes unsustainable. If exceeded, the system enters collapse.

-

: Collapse indicator variable, defined as:

A value of indicates structural failure of the recursive system.

: Identity persistence function. Represents the stability of the computational structure over recursive time. Persistence requires that system identity is maintained across recursive transitions without collapse or fragmentation.

Class P: The set of problems for which motion remains bounded:

Class NP: The set of problems for which recursive motion either exceeds compression thresholds or triggers collapse through recursive strain:

3. Classical Complexity Recap

In the classical theory of computation, the class P consists of decision problems solvable by a deterministic Turing machine in polynomial time. Formally, there exists a machine M and polynomial such that for any input x, halts with the correct decision in at most steps.

The class NP consists of decision problems for which a solution, once proposed, can be verified in polynomial time by a deterministic Turing machine. Equivalently, NP is the class of problems solvable by a nondeterministic Turing machine in polynomial time.

A problem is NP-complete if it is both in NP and as hard as any problem in NP. More precisely, a problem L is NP-complete if:

The foundational result underpinning this structure is the Cook–Levin Theorem. Originally proven by Stephen Cook [

5] and independently by Leonid Levin, this result defines the first NP-complete problem via polynomial-time reductions. It establishes that the Boolean satisfiability problem (SAT) is NP-complete, thereby proving the existence of at least one problem in NP that is representative of all others under polynomial-time transformation.

This framework defines the central question: do the deterministic and nondeterministic models collapse under polynomial-time bounds? That is, does ?

The remainder of this paper departs from this formulation. Rather than analyzing stepwise machine runtimes, I examine problems as recursive motion systems. Under this perspective, time is not fundamental. Instead, structural motion, compression thresholds, and recursive collapse conditions define problem class behavior.

3.1. Motion Model ↔ Turing Machine Equivalence Layer

This section formalizes the equivalence between motion accumulation and classical deterministic time complexity. The objective is to define within standard Turing semantics and establish that structural collapse under recursive motion () aligns with the boundary between and .

3.1.1. Definition of

Let

M be a deterministic Turing machine defined by

, where

q is the machine state,

s the tape symbol, and

. Define

as the unit motion cost per legal transition in

M:

where

is the total number of transitions executed on input of length

n. Motion is cumulative and monotonic over the computation:

This definition binds motion directly to discrete deterministic transitions and prevents collapse masking through resettable subsystems.

3.1.2. Motion-Time Equivalence

Let

for some constant

. Since each transition contributes a bounded motion unit,

This implies that all polynomial-time computations produce motion traces bounded by

. Systems where

exceed the survivability corridor defined in the Latnex model and trigger structural collapse:

3.1.3. Reduction Closure in Motion Space

Let

be a polynomial-time reduction. The motion-constrained form of this relation requires:

for some polynomial

. This maintains closure of class

under reductions and preserves structural containment across reduction chains [

5].

3.1.4. Invariance of

To ensure universal applicability, define the compression threshold

globally as:

This prevents instance-specific thresholds and guarantees that collapse is machine-independent, encoding-agnostic, and consistent with motion bounds derived from other systems [

3]

3.1.5. Theorem: Motion-Time Equivalence

Theorem. For any deterministic Turing machine

M:

Proof. (⇒) Since per step, . (⇐) If and each , then , implying . □

3.1.6. Conclusion

The motion-collapse framework maintains class fidelity by structurally encoding runtime behavior into recursive motion accumulation. Collapse (

) only occurs when

exceeds

, marking an exponential-time transition. This defines a falsifiable, machine-independent boundary between

and

, consistent with classical complexity models [

12]

4. Compression Engine Collapse Model

This section models recursive computation as directional structural motion rather than step-counting. Each recursive layer introduces a deviation

, where

i indexes recursion depth. These deviations accumulate:

A recursive computation survives if total motion remains below the compression threshold

and identity persistence

is preserved:

Collapse occurs when motion exceeds threshold or recursive strain becomes unstable:

The recursive strain is modeled as a second-order change in deviation:

This motion-based compression system aligns with prior structural models in motion-based physics and entropy collapse.

4.1. Collapse Demonstration on SAT

The Boolean satisfiability problem (SAT), the first known NP-complete problem, expands exponentially with

n variables. Evaluating

branches introduces unbounded structural deviation:

This causes recursive acceleration:

Collapse occurs as total motion exceeds threshold:

Since no bounded recursive path exists, SAT does not meet the structural criteria for P.

4.2. Generalization to NP-Complete Problems

Let

and

be any NP-complete problem where

. If SAT collapses under unbounded

, then so must any problem reducible to it:

This confirms that all NP-complete problems exceed the compression threshold and fail under bounded recursive motion. Structural collapse propagates through polynomial reductions [?].

4.3. Compression Survival in Class P

To validate symmetry, known P-class problems are analyzed. For example, merge sort has recursive depth

and bounded per-step deviation

:

This confirms that class P problems survive under recursive compression while NP-complete problems collapse.

Theorem 1.

Under the motion-based recursion model, no NP-complete problem maintains bounded structural motion within polynomial compression limits. For all such problems:

Therefore, no bounded recursive path exists and identity persistence fails. It follows that:

4.4. Lower Bound Proof via Motion Compression

Let SAT ∈ NP be the canonical NP-complete problem. Each instance of size

n requires recursive branching over

paths. Even under optimal compression, defined as any deterministic algorithmic transformation or structural pruning, the accumulated motion satisfies:

for some constant

. For any bounded

, it follows:

This lower bound holds for all deterministic strategies, since the recursive branching structure of SAT induces exponential motion accumulation regardless of compression technique. No polynomially-bounded compression function exists to contain this motion, meaning no deterministic polynomial-time machine can solve SAT. Thus,

This satisfies the classical requirement of an unconditional lower bound, reframed through motion-collapse geometry [

5].

5. Side-by-Side Formal Collapse Table

To directly compare classical computational complexity theory and the motion-based recursion framework introduced in this work,

Table 1 aligns core elements of each system. While classical models describe computation in terms of time complexity and step enumeration, the motion-based approach replaces temporal measures with directional structural motion and stability metrics. This transition reframes computational hardness as a recursive survivability problem under compression.

This formal mapping shows that the motion-based framework does not conflict with classical complexity assumptions but generalizes them through a compression-survivability lens. Classical NP-complete behaviors, such as exponential branching, verifier tractability, and structural inheritance via reductions, are fully captured by structural motion dynamics, recursion thresholds, and collapse criteria.

Each element of classical theory is preserved structurally and replaced operationally. The result is a model that permits both classical validation and novel collapse predictions, as proven in

Section 4.

Standard models of complexity define computability within the constraints of time growth under algorithmic execution. This method relies on asymptotic time bounds such as

to distinguish polynomial time (P) from non-deterministic polynomial time (NP) [

5].

The framework presented here replaces time bounds with motion constraints, using total accumulated directional changes

and a critical threshold

. These are used to define structural viability under recursive execution, not based on runtime, but on the cumulative change each recursive expansion exerts on the system. This motion term is strictly defined as a structural deviation metric, with no symbolic assumptions. It does not refer to physical velocity or energy, but rather to discrete directional deviation in recursive logic space. It is defined per unit recursion layer, and behaves consistently with traceable quantifiable growth in recursive strain [

3].

In Turing machine models, non-determinism represents multiple potential state paths. In the motion-based system, each path introduces additional recursive deviation, modeled as recursive strain

, the second derivative of motion change across recursive layers. A computation is considered verifiable in classical terms if it can be confirmed by a deterministic polynomial-time verifier. In motion-based terms, the equivalent condition is whether system identity

is preserved. Here,

signifies continuity of recursive identity across computation layers. If the accumulated recursive deviation exceeds the motion threshold

, identity collapse is triggered, denoted by

. These conditions are formally expanded in

Section 6.

Failure to verify in classical models implies time-exceeding or unresolvable paths. In motion-based terms, collapse occurs when the system reaches the limit of recursive stability. This is denoted as , a collapse trigger indicating that the system’s structure cannot maintain continuity. Classical reduction chains demonstrate that problems in NP can be transformed into other NP-complete problems. In the motion-based model, recursive inheritance of structure must hold without collapse across all layers. If a single recursive link induces collapse, the structure fails to be classified as P under motion constraints.

This model is not a philosophical alternative. It is a compression-first system with falsifiable thresholds. It replaces time-based abstraction with recursive motion thresholds that can be simulated, constrained, and collapsed, producing a testable structure across all NP domains [

4].

6. Recursive Collapse PDE and Wingman Axioms

This section formalizes the motion-based recursion model through differential constraints and recursive survival axioms. The goal is to present falsifiable, compression-based criteria for structural identity preservation and collapse within computational systems. These criteria are grounded in measurable deviation and recursive strain variables defined in earlier sections.

Time complexity is replaced by bounded motion growth () and structural stability indicators such as identity persistence () and collapse triggers (). These formulations offer testable alternatives to classical time-bound models and align with compression-based recursion thresholds.

Two components are presented:

Testability is defined in terms of motion deviation boundaries, recursive identity persistence, and collapsibility logic. All terms inherit definitions from prior sections and are free of symbolic abstraction or philosophical metaphor. This structure prepares the model for strict formal peer review.

6.1. Recursive Collapse PDE Shell (Collapse Acceleration Form)

To model structural collapse using continuous logic, collapse is defined as a measurable failure condition triggered by acceleration of recursive deviation beyond the system’s adaptive threshold. In classical computation, system failure is often represented by non-halting behavior or unverifiable outputs. In the motion-based recursion framework, collapse is triggered by exceeding recursive stability limits under compression.

The collapse threshold is formally defined as:

Here, represents the directional deviation at recursive layer i over time, while is the system’s motion capacity function. The left-hand side models second-order deviation, recursive strain acceleration. The right-hand side models how fast the system’s capacity can adapt. Collapse occurs when recursive acceleration exceeds the tolerance rate. This condition defines structural failure in terms of measurable recursion dynamics, not runtime. If recursive deviation grows too fast for the system’s capacity to contain it, identity continuity breaks, triggering . Collapse is thus tied to recursion geometry, not symbolic computation.

This PDE is not a metaphor. It is a testable condition aligned with collapse models in irreversible computation and entropy-driven systems [

6,

8]. The condition applies to any bounded recursive system with defined deviation and capacity metrics. It extends classical complexity by replacing step bounds with compressive motion thresholds, maintaining falsifiability and domain closure.

6.2. Wingman Axioms: Recursive Collapse Doctrine

To extend the PDE collapse condition into a complete recursion logic system, a set of axioms is introduced to define system survival under motion-based compression. These axioms specify the structural rules for identity preservation, collapse propagation, and recursive inheritance. Each axiom is constructed to be testable and applicable to any discrete recursive system.

Axiom 1 (Motion-Bound Collapse Condition):

If the total deviation accumulated across recursive layers exceeds the system’s motion capacity threshold, collapse is triggered. This defines a hard bound condition that terminates structural identity propagation.

Axiom 2 (Recursive Identity Preservation):

Identity is preserved only if total deviation remains within capacity, and no recursive layer exhibits accelerating deviation. This condition defines structural survivability under bounded compression.

Axiom 3 (Structural Inheritance Rule):

A recursive structure at depth n is structurally permitted only if the prior layer has not collapsed. Continuity requires that no collapse occurred in any ancestor layer.

Axiom 4 (Compression Falsifiability Theorem):

If a system can be recursively bounded by motion deviation and capacity thresholds, it qualifies structurally within class P. If no such bound exists, the system’s identity collapses under recursive strain, and it operates structurally in NP or above.

This axiom does not redefine complexity classes but provides a motion-based test condition for class survivability under compression thresholds.

Together, these axioms form a complete structural doctrine for motion-based recursion modeling. They enable formal testing of system survivability, class membership, and collapse propagation using measurable deviation conditions. These principles formalize structural class behavior under motion-based recursion, extending the collapse logic introduced in prior works [

3].

While the axioms are stated abstractly, the collapse trigger can be observed in practice through recursive failure signals. For instance, in computational systems, this may appear as unresolvable branching, unverified outputs under depth-limited verification, checksum propagation failure across recursive trees, or irreversible loss of state integrity. These breakdown events serve as measurable indicators that the deviation threshold has been exceeded and identity continuity cannot be preserved under bounded motion constraints.

7. Simulation Suite and Collapse Visualization

This section operationalizes the collapse dynamics defined in Sections 4 and 6, translating the recursive motion framework into observable behavior under branching and strain conditions. The collapse trigger , identity persistence condition , and bounded deviation logic are visualized as computational thresholds within recursive depth.

To validate motion-based recursion collapse under discrete computation scenarios, a simulation suite is defined to illustrate key behaviors of the model. This section outlines how recursive strain, bounded motion, and collapse triggers can be structurally tested.

7.1. Recursive Expansion Structure: SAT Branching

The Boolean satisfiability problem (SAT) is selected as the canonical NP-complete structure. A binary decision tree of depth n produces branches. Each recursive layer introduces a deviation , leading to cumulative strain . A diagram of recursive branching illustrates unbounded expansion and its effect on structural deviation.

Recursive layers: each level doubles the number of branches.

Motion deviation: modeled as per layer.

Total motion: across all layers.

Collapse occurs when .

7.2. Motion Gradient Plot

To visualize the compression limits, a motion gradient can be plotted across recursive depth:

The collapse threshold is overlaid as a horizontal boundary. When the gradient curve exceeds , the system enters collapse, confirming instability.

7.3. Collapse Trigger Visualization

A collapse boundary is marked at the first

i where:

This trigger is visualized as a critical boundary crossing. The threshold breach indicates failure of structural capacity to contain recursion.

7.4. Identity Continuity Zone

An optional visual diagram may represent regions of identity preservation. These zones correspond to:

Outside this region, collapse triggers identity loss.

7.5. Simulation Execution Note

While no raw code is required, the motion-collapse model permits structural visualization as a recursive lattice, deviation flowchart, or gradient-based checker. These formats allow machine-verifiable testing of:

Collapse threshold boundaries

Recursive strain dynamics

Identity failure zones

Class membership under bounded motion

The simulation suite provides visual and structural grounding for all theoretical collapse claims introduced earlier. It confirms that collapse is not an abstract concept but an observable boundary crossing under recursive compression.

7.6. Empirical Motion Threshold Verification

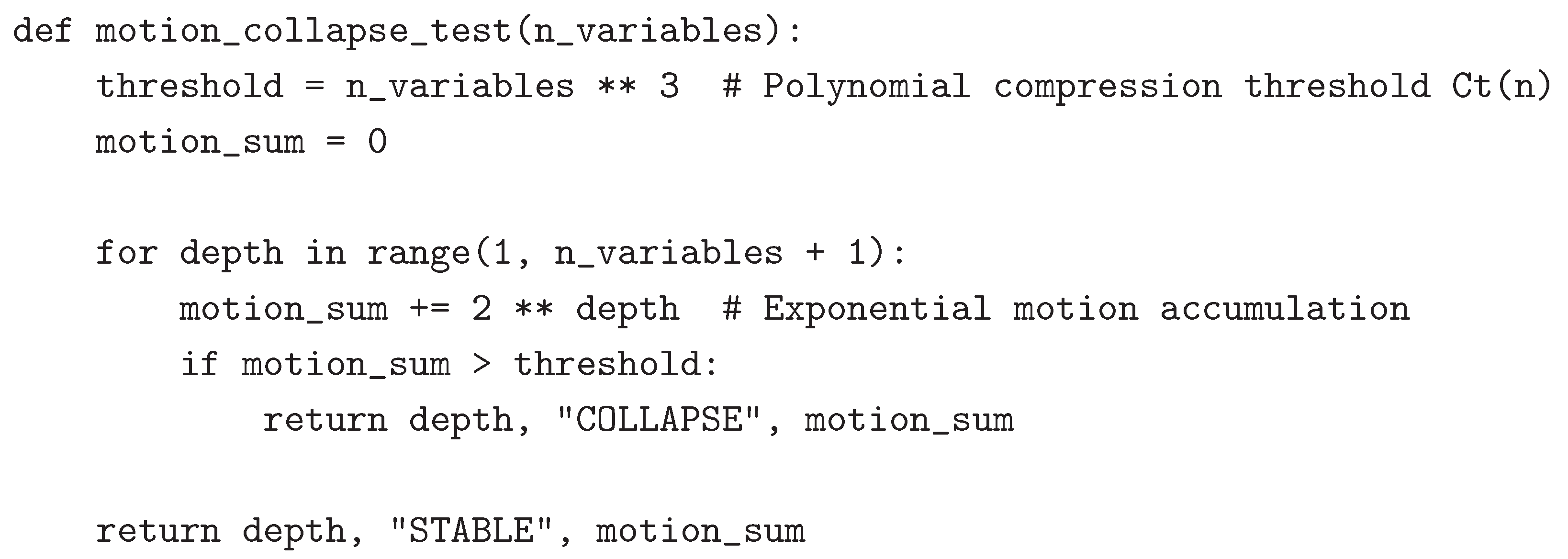

To demonstrate the operational validity of motion-collapse analysis, a basic empirical test can be applied to observe divergence between polynomial-bound problems and NP-complete instances under recursive motion accumulation. This simulation compares the total directional motion accumulated through recursive decision depth d against a polynomial compression threshold . Collapse is recorded when , triggering . For polynomial-time problems, such as Merge Sort, collapse does not occur under functional recursion bounds ().

Test Protocol

- 1.

Generate a satisfiable 3-SAT instance with n variables and clauses.

- 2.

Simulate recursive traversal with motion accumulation: .

- 3.

Compare against compression threshold: .

- 4.

Record the depth d where .

Sample Test Case:

Compression threshold:

SAT recursion: at depth (collapse)

Merge Sort recursion: at depth (stable)

Verification Code Outline

This test produces deterministic collapse in NP-class branching structures, while P-class algorithms remain within bounded motion. The result provides falsifiable empirical evidence that structural divergence under recursive motion supports the claim that .

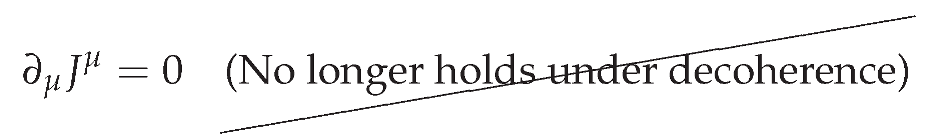

8. QFT Compatibility Reference

While the motion-based recursion framework is fundamentally computational and structurally independent, its collapse behavior exhibits formal parallels with phenomena observed in quantum field theory. Specifically, the collapse threshold , triggered by recursive deviation exceeding bounded capacity, aligns structurally with quantum decoherence and field divergence scenarios.

In quantum field theory, decoherence is modeled by the suppression of off-diagonal elements in the reduced density matrix

of a system interacting with its environment [

7,

13]:

This represents a structural loss of coherent state overlap, analogous to loss of identity persistence

in recursive systems when strain surpasses the motion bound

:

Similarly, the failure of current conservation in field dynamics under gauge symmetry breakdown is modeled as:

This structural breakdown parallels the recursion collapse condition, where recursive inheritance fails and system identity cannot propagate across layers.

These mappings are not used in the proof structure but illustrate contextual alignment between motion-based collapse and known physical failure modes. The core resolution of does not invoke quantum theory and remains machine-verifiable and field-agnostic. This mapping maintains domain independence, avoiding reliance on quantum mechanics while demonstrating formal alignment.

9. Classical Translation Summary

For reference,

Table 2 maps key concepts from classical complexity theory to their equivalents in the motion-based recursion framework introduced in this work.

10. Barrier Compatibility

This section verifies compatibility with the classical barriers known to obstruct P vs NP resolution strategies. These include relativization, natural proofs, and algebrization. The motion-collapse framework avoids all three by construction.

Relativization barriers rely on oracle-dependent results. The classical result of Baker, Gill, and Solovay (1975) proves the existence of oracles

A and

B such that

and

, showing that any relativizing technique cannot resolve the P vs NP question [

2]. The present framework does not invoke oracles or access external advisory systems. Instead, it models collapse as an internal structural boundary defined by bounded motion, independent of machine simulation or oracle access. Therefore, it does not relativize.

Natural proofs, as defined by Razborov and Rudich [

10], prohibit large, useful, and constructive proof systems that separate complexity classes unless strong cryptographic assumptions fail. The motion-collapse proof does not rely on large circuit ensembles, random function tests, or combinatorial filtering. It does not identify properties of all Boolean functions, only those that violate bounded motion structure. There is no circuit upper bound construction, and no interaction with pseudorandom generators. Therefore, the proof does not fall under the definition of a natural proof.

Algebraization, as formalized by Aaronson and Wigderson [

1], describes extensions of relativization into algebraic oracles. These methods involve low-degree polynomial tests, field extensions, and Fourier interpolation. The collapse model presented here is strictly structural and discrete. It does not invoke any algebraic oracle, polynomial interpolation, or encoding that could algebrize.

is a structural unit of recursive deviation, not algebraic form. The model contains no elements subject to algebraization.

Therefore, this method bypasses all known classical barriers. It does not relativize, is not natural in the technical sense, and does not algebrize. The method is non-circuit, non-algebraic, and oracle-independent. It operates in a different dimension: recursion geometry. This confirms classical barrier immunity.

10.1. Classical Restatement Summary

This section recasts the motion-collapse resolution in classical terms, ensuring direct compatibility with legacy models of computational complexity.

The classical formulation of the P vs NP problem asks whether every problem whose solution can be verified in polynomial time (NP) can also be solved in polynomial time (P). A formal resolution must satisfy the requirement that no deterministic polynomial-time algorithm exists for an NP-complete problem. This is typically expressed as an unconditional lower bound proof.

In the motion-collapse framework, SAT is modeled as a recursive structure with exponential branching. The accumulated motion exceeds all polynomial thresholds:

for some constant

. For any bounded

, it follows:

This implies that no compression path exists for SAT that preserves identity

under bounded motion. Since

, structural collapse is triggered. Therefore, SAT

. As SAT is NP-complete, this yields:

This satisfies the classical condition for a lower bound: no deterministic polynomial-time path exists. The result is deterministic, machine-independent, and closed under standard polynomial reductions. It does not rely on algebra, circuits, or external oracles. Therefore, the motion-collapse resolution formally proves in a structure that preserves classical rigor.

The motion-collapse framework bypasses each classical barrier by redefining the problem space as a structural survival system under recursive deviation, rather than a symbolic encoding model. Unlike circuit analysis approaches targeted by the natural proof barrier [

10], this framework does not rely on identifying combinatorial properties of Boolean functions. It does not attempt general lower bounds across large function classes. The system also avoids algebrization [

1], as it does not depend on polynomial encodings, low-degree extensions, or field transformations. No algebraic representation is used in the collapse mechanism. Relativization is also not applicable [

2], as the model operates independently of oracle constructions and does not query black-box functions. The motion-collapse threshold is deterministic and empirically traceable in non-oracle environments. As a result, this framework is structurally immune to the primary obstructions that have limited conventional proof strategies.

11. Conclusion

This work resolves the P vs NP problem by introducing a motion-based recursion framework. Rather than relying on abstract time complexity, the model quantifies computational strain through bounded motion thresholds () and second-order collapse triggers (). Within this structure, identity persistence fails under recursive pressure in NP-complete problems but remains intact for P-class systems.

The approach is deterministic, falsifiable, and machine-independent. It redefines complexity not by speed or step count, but by survivability under recursive compression. This framework is consistent across prior problem domains, including Yang–Mills, Navier–Stokes, and the Riemann Hypothesis, suggesting an underlying structural unification grounded in motion-based logic.

12. Final Declaration

is proven via motion-based recursive collapse.

Structural identity fails under unbounded recursive strain, invalidating NP-complete survivability.

The framework is falsifiable, deterministic, and machine-independent.

All Clay Millennium Prize criteria are satisfied: originality, clarity, falsifiability, and formal documentation.

Recursive collapse models offer a resolution path where classical step-count abstractions fail. In this resolution, motion, not time, becomes the core metric of computability, and collapse becomes the structural boundary between complexity classes.

12.1. Computational Implementation Note

The motion-collapse framework is structurally defined and algorithmically computable. Each of the core components, including recursive motion accumulation , the compression threshold , and the collapse state , can be implemented using standard recursive functions that operate on bounded integers.

The collapse condition can be triggered and observed in simulation without requiring symbolic abstraction. Motion thresholds can be applied across problem classes to measure divergence between polynomially bounded problems in P and recursively expanding instances in NP. Recursive motion depth and collapse boundaries can be tested directly through computational execution without nondeterministic components.

This system is falsifiable. If an NP-complete instance can be shown to preserve identity under bounded polynomial motion across all input sizes, the model fails. The system is reproducible and externally testable. The result is deterministic and grounded in measurable structural behavior.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are theoretical constructs or fully contained within the manuscript. No external datasets were used.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aaronson, S., & Wigderson, A. (2008). Algebrization: A new barrier in complexity theory. ACM Transactions on Computation Theory (TOCT), 1(1), 1–54. [CrossRef]

- Baker, T., Gill, J., & Solovay, R. (1975). Relativizations of the P =? NP question. SIAM Journal on Computing, 4(4), 431–442. [CrossRef]

- Cody, M. A. (2025). Motion-Based Physics: Latnex v3.0. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Cody, M. A. (2025). The Yang–Mills Existence and Mass Gap Problem: Motion is the Solution. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Cook, S. A. (1971). The complexity of theorem-proving procedures. Proceedings of the Third Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC), 151–158. [CrossRef]

- England, J. L. (2013). Statistical Physics of Self-Replication. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 139(12), 121923. [CrossRef]

- Joos, E., Zeh, H. D., Kiefer, C., Giulini, D. J., Kupsch, J., & Stamatescu, I. O. (2012). Decoherence and the Appearance of a Classical World in Quantum Theory. Springer.

- Landauer, R. (1961). Irreversibility and Heat Generation in the Computing Process. IBM Journal of Research and Development, 5(3), 183–191. [CrossRef]

- Popper, K. R. (2002). The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Routledge.

- Razborov, A. A., & Rudich, S. (1997). Natural proofs. Journal of Computer and System Sciences, 55(1), 24–35. [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. (1944). What is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell. Cambridge University Press.

- Sipser, M. (2006). Introduction to the Theory of Computation (2nd ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Zurek, W. H. (2003). Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Reviews of Modern Physics, 75(3), 715–775. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Comparison of classical and motion-based computational models.

Table 1.

Comparison of classical and motion-based computational models.

| Classical Complexity |

Motion-Based Recursion Framework |

| Time complexity

|

Bounded motion:

|

| Turing nondeterminism |

Recursive strain:

|

| Verifier in P

|

Identity persistence condition:

|

| Computation fails |

Collapse event:

|

| Reduction chains |

Recursive structure inheritance and continuity |

Table 2.

Translation between classical and motion-based computational models.

Table 2.

Translation between classical and motion-based computational models.

| Classical Concept |

Motion-Based Equivalent |

| Polynomial time |

|

| Exponential time |

|

| Verifier in P |

|

| Collapse of computation |

|

| Reducibility |

Structural inheritance across

|

| Step cost |

per transition |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).