Submitted:

29 February 2024

Posted:

01 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

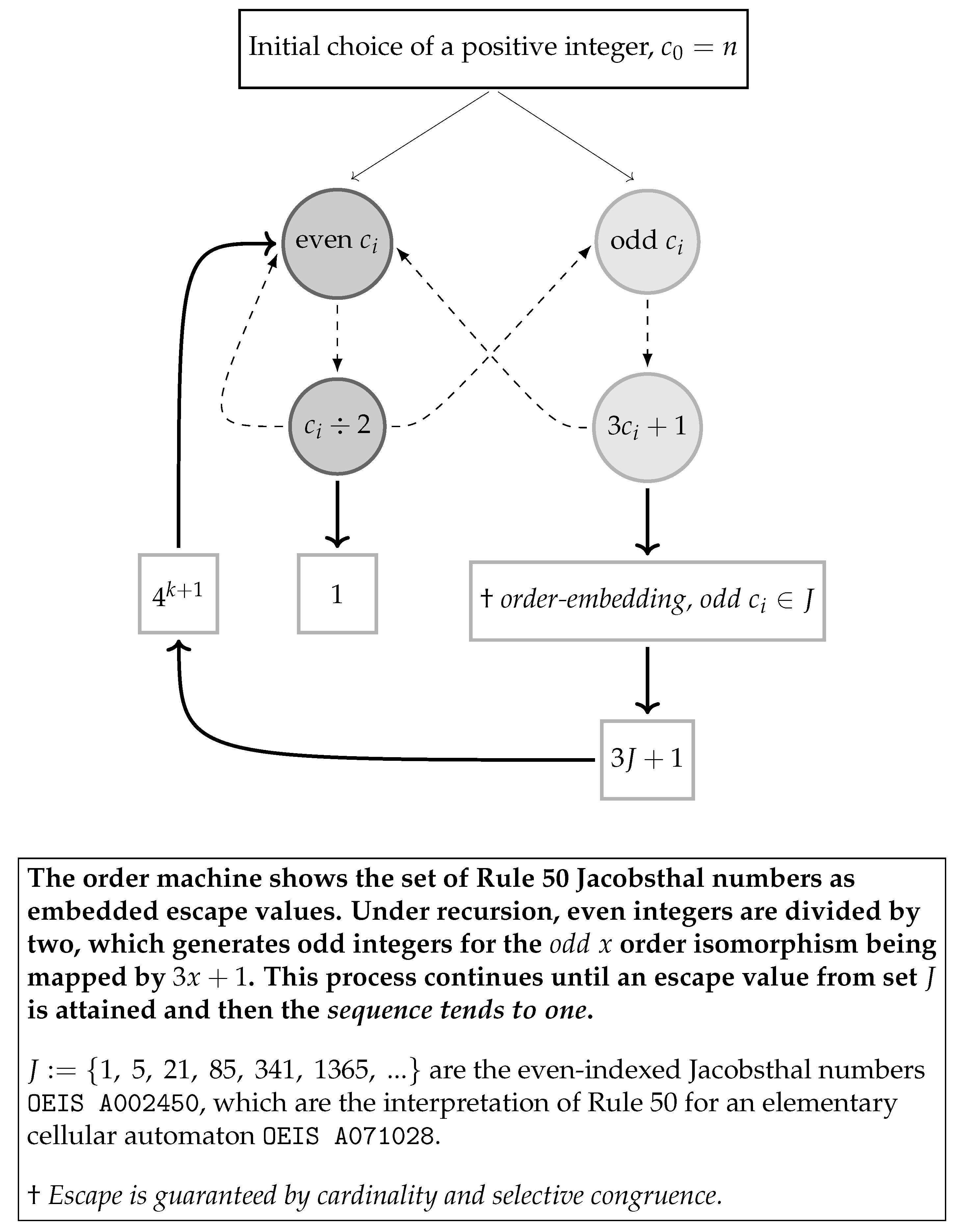

2.1. Define Collatz Conjecture

- Let . Three is odd, so . Ten is even, so . Five is odd and iteration continues until the following sequence is generated.

- Let , the sequence is . Let , the sequence is . Let , the sequence is .

- Collatz conjecture statement. For any initial choice of positive integer, , iteration using f will always generate a sequence that tends to one, that is .

2.2. Prior Research and Results

3. Methods and Results

3.1. Methodology

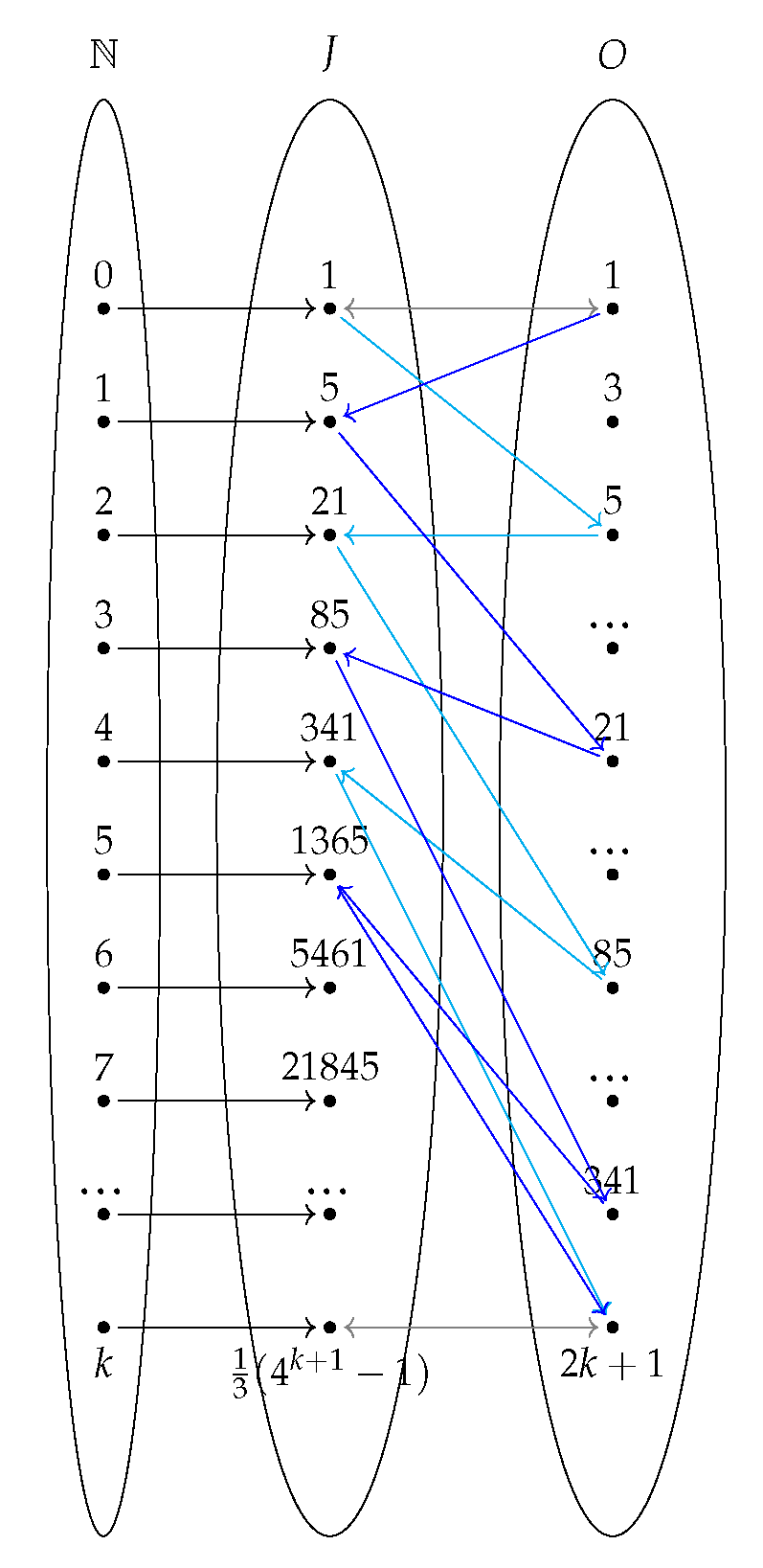

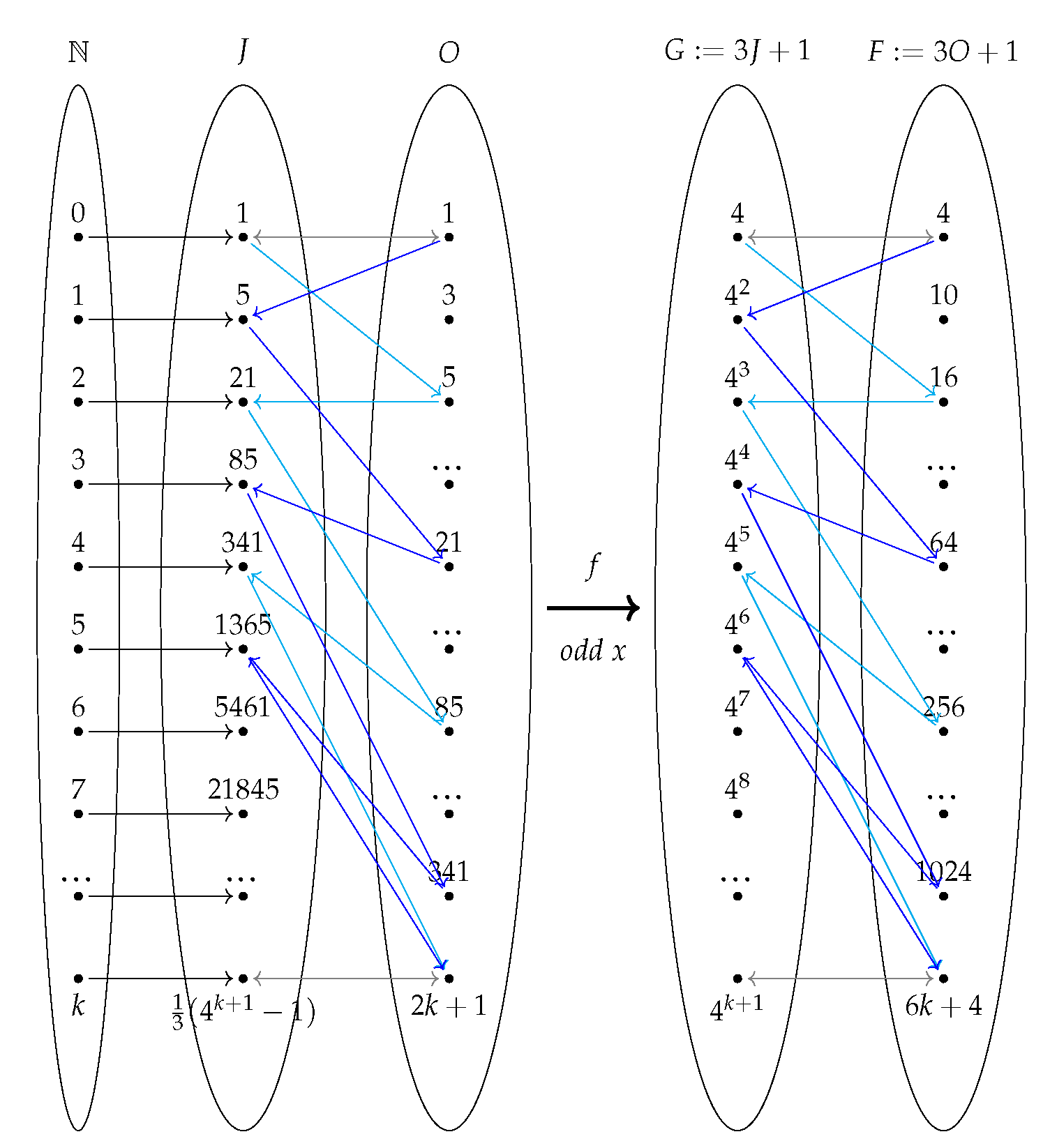

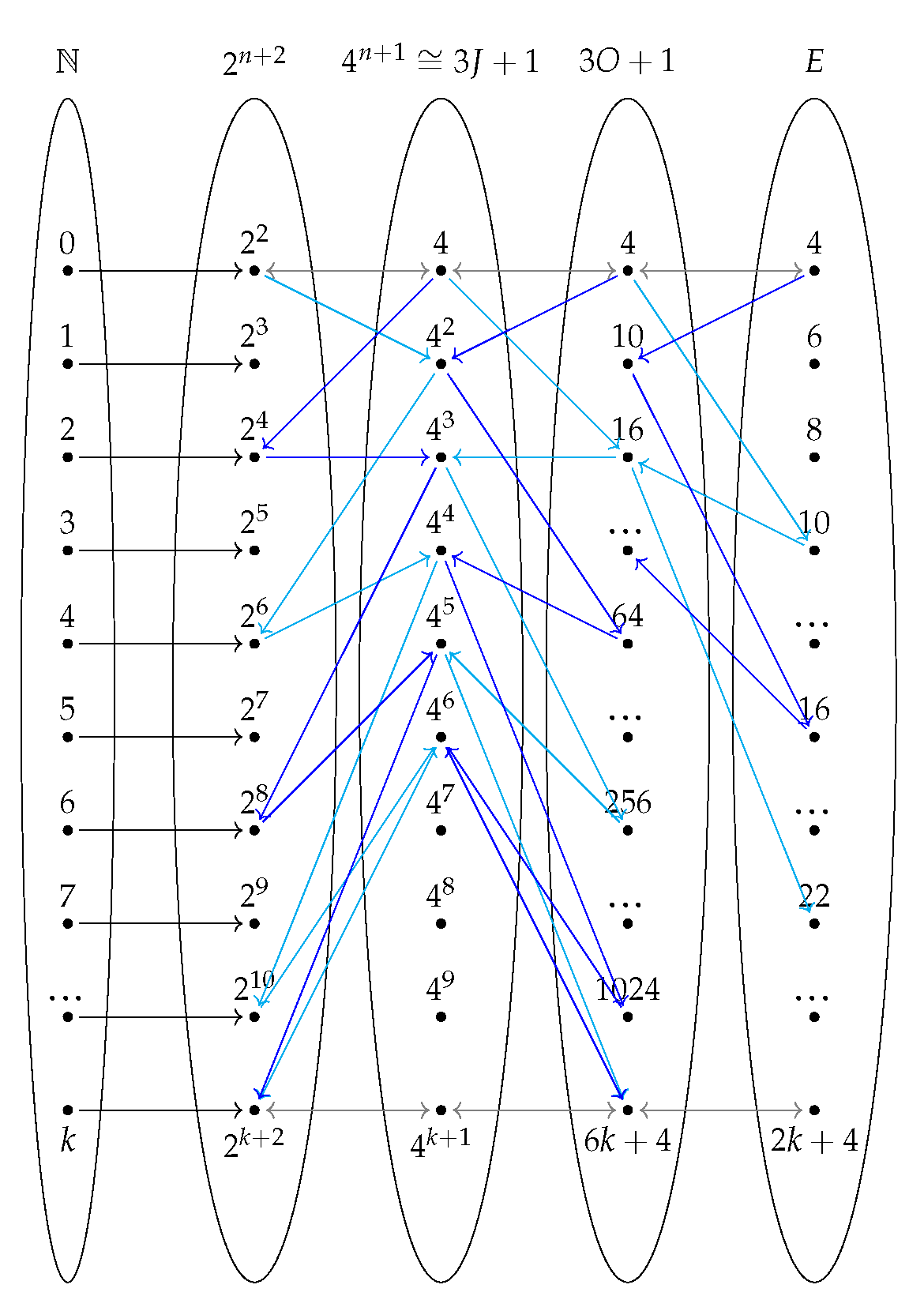

3.2. Set and Order Theory

3.3. Combinatorics

4. Discussion and Conclusion

5. Appendix

5.1. Set Theory Definitions

- Reflexive. For any set M, is a bijection .

- Symmetric. If is a bijection , then implies .

- Transitive. If and are bijections and , respectively, then implies .

5.2. Order Theory Definitions

- Reflexivity: for all .

- Antisymmetry: and implies .

- Transitivity: and implies .

- Reflexive, antisymmetric, and transitive for all .

- Comparability: either or is true for all .

5.3. Jacobsthal Sequence

5.4. Binomial Theorem

References

- M. Aigner and G.M. Ziegler (2018), Proofs from THE BOOK, sixth ed., Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany.

- E. Barone, A heuristic probabilistic argument for the Collatz sequence. (Italian), Ital. J. Pure Appl. Math. 4 (1999), 151–153.

- N. Bourbaki, Theory of Sets, Eléments de mathématiques 1, reprint ed. Springer (2004).

- G. Cantor (1883), “Ueber unendliche, lineare Punktmannichfaltigkeiten”, Mathematische Annalen 21, pp. 545–591. [CrossRef]

- K. Ciesielski, Set Theory for the Working Mathematician, London Mathematical Society Student Texts, vol. 39, Cambridge University Press, 1997, pp. 38–39.

- J. H. Conway, Unpredictable Iterations, Proc. 1972 Number Theory Conference (Univ. Colorado, Boulder, Colo., 1972), pp. 49-–52. Univ. Colorado, Boulder, Colo. 1972.

- J. H. Conway, FRACTRAN: A Simple Universal Computing Language for Arithmetic, In: Open Problems in Communication and Computation (T. M. Cover and B. Gopinath, Eds.), Springer-Verlag: New York 1987, pp. 3–27.

- F. H. Croom, Principles of Topology, reprint ed. Dover (2016).

- L. Fuchs (1963), Partially Ordered Algebraic Systems, Dover Publications, Reprint ed. March 5, 2014, pp. 2–3. 5 March.

- C. J. Everett (1977), Iteration of the number theoretic function f(2n)=n,f(2n+1)=3n+2, Advances in Math. 25 (1977), 42–45. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Guy (1983a) Don’t try to solve these problems!, Amer. Math. Monthly 90 (1983), 35–-41. [CrossRef]

- K. Hartnett, Mathematician Proves Huge Result on ’Dangerous’ Problem, Quanta Magazine, 2019.

- J. C. Lagarias, The 3x+1 problem and its generalizations, Amer. Math. Monthly 92 (1985), pp. 3–-23. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Lagarias, The set of rational cycles for the 3x + 1 problem, Acta Arithmetica 56 (1990), pp. 33–-53.

- J. C. Lagarias, The 3x+1 problem: An annotated bibliography (1963-1999), arXiv:math/0309224 Jan. 11, 2011, v13.

- J. C. Lagarias, The 3x+1 problem: An annotated bibliography, II (2000-2009), arXiv:math/0608208 Feb. 12, 2012, v6.

- The Ultimate Challenge: The 3x + 1 Problem. Edited by Jeffrey C. Lagarias. American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI, 2010, pp. 3–29.

- J. C. Lagarias, The 3x+1 Problem: An Overview. arXiv:2111.02635 Nov. 21, 2021, v1.

- D. Muller, A. Kontorovich, The simplest math problem no one can solve (short video), Veritasium, 2021.

- OEIS Foundation Inc. (2022), The Jacobsthal numbers, Entry A001045 in The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. http://oeis.org/A001045.

- OEIS Foundation Inc. (2022), The even-index Jacobsthal numbers, Entry A002450 in The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. http://oeis.org/A002450.

- OEIS Foundation Inc. (2022), Triangle read by rows giving successive states of cellular automaton generated by "Rule 50", Entry A071028 in The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. http://oeis.org/A071028.

- Bakuage Co., Ltd. (Japan). https://mathprize.net/posts/collatz-conjecture/index.htmlAccessed on 22 November 2021.

- N. J. A. Sloane (ed.), Sequence A001045 (Jacobsthal numbers), The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, OEIS Foundation.

- T. Tao, Almost all Collatz orbits attain almost bounded values, What’s new, Sept. 10, 2019. 2022. https://terrytao.wordpress.com/2019/09/10/almost-all-collatz-orbits-attain-almost-bounded-valuesAccessed 03 January 2022.

- T. Tao, Almost all orbits of the Collatz map attain almost bounded values, arXiv:1909.03562 Sept. 18, 2021, v4.

- R. Terras, A stopping time problem on the positive integers, Acta Arithmetica 30 (1976), 241–252.

- V. Thierry, Handbook of Mathematics, Norderstedt: Springer (1945), p. 23.

- Binomial theorem. (2021, July 18). Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binomial_theoremAccessed 25 July 2021.

- Cantor isomorphism theorem. (2021, July 18). Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cantor%27s_isomorphism_theoremAccessed 22 November 2021.

- Collatz conjecture. (2021, July 18). Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. 25 July. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collatz_conjectureAccessed 25 July 2021.

- Equivalence relation. (2021, December 26). Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equivalence_relation.

- Order isomorphism. (2021, July 18). Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Order_isomorphismAccessed 22 November 2021.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Totally Ordered Set." From MathWorld–A Wolfram Web Resource. 05 January. https://mathworld.wolfram.com/TotallyOrderedSet.htmlAccessed 05 January 2022.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Partial Order." From MathWorld–A Wolfram Web Resource. https://mathworld.wolfram.com/PartialOrder.htmlAccessed 05 January 2022.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Rule 50." From MathWorld–A Wolfram Web Resource. 03 January. https://mathworld.wolfram.com/Rule50.htmlAccessed 03 January 2022.

| 1 | A child is able to show one-to-one finger correspondence long before they are able to count to five [8] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).