Submitted:

28 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

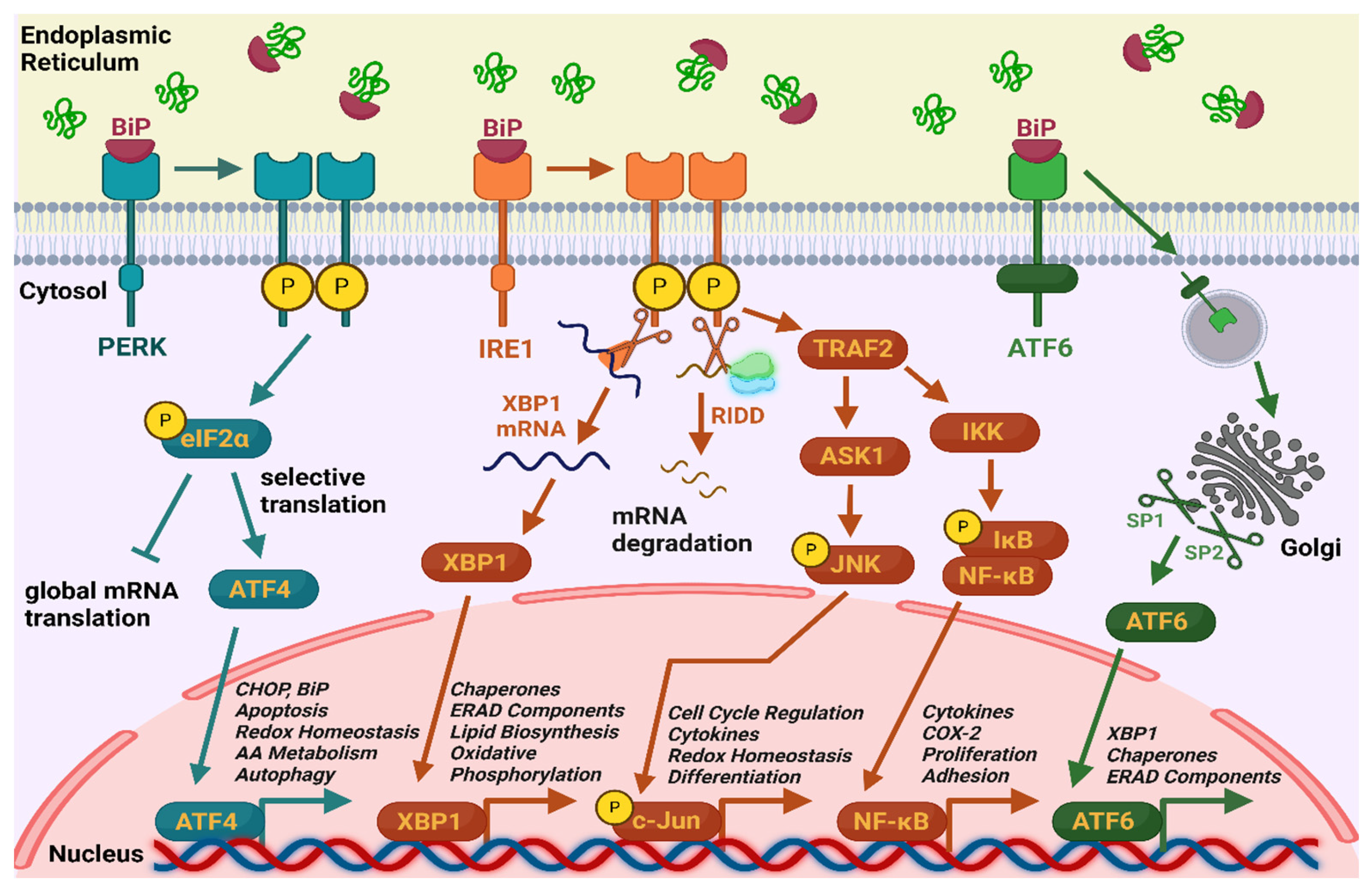

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

- Text availability – free full texts

- Publication date – from 2000/1/1 to 2025/5/1

- Article type – research articles

- Subject area – Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology

- Access type – open access and open archive

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Statistical Analyses and Presentation

3. Results

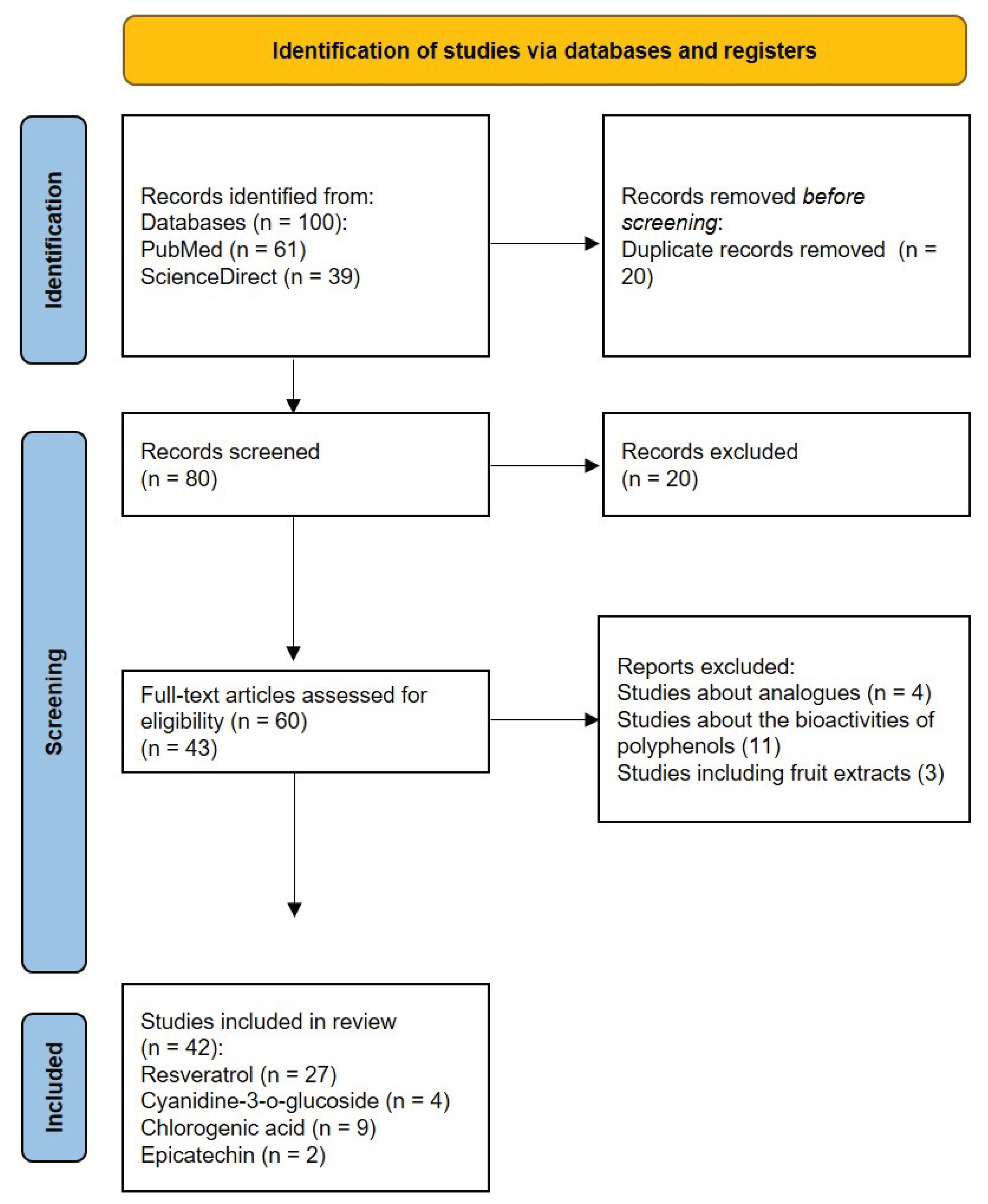

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Presentation of the Results

3.2.1. Modulation of ER Stress by Resveratrol

3.2.2. Modulation of ERS by Cyanidin-3-o-Glucoside, Chlorogenic Acid and Epicatechin

4. Discussion

- insufficient information on the effects of some polyphenols across all UPR branches.

- heterogeneity in experimental models limits direct comparisons and generalization.

- dose variation and dual effect of resveratrol on ER stress – determining the precise therapeutic dose and anticipating potential side effects is challenging.

- lack of clinical trials and data on long-term effects of polyphenol intake – it is difficult to determine the therapeutic potential of polyphenols, as well as to assess the long-term safety and efficacy of these compounds.

- although the results highlight the significant contribution of the polyphenols found at the highest concentrations in the aqueous dwarf elder extract, the possible biological activity of other present phytochemicals in lower amounts cannot be excluded.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schwarz, D.S.; Blower, M.D. The Endoplasmic Reticulum: Structure, Function and Response to Cellular Signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci 2016, 73, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozcan, L.; Tabas, I. Role of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Metabolic Disease and Other Disorders. Annu Rev Med 2012, 63, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.H.; Walter, P.; Yen, T.S.B. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Disease Pathogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol 2008, 3, 399–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ron, D.; Walter, P. Signal Integration in the Endoplasmic Reticulum Unfolded Protein Response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007, 8, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnain, S.Z.; Lourie, R.; Das, I.; Chen, A.C.; McGuckin, M.A. The Interplay between Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Inflammation. Immunol Cell Biol 2012, 90, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprenkle, N.T.; Sims, S.G.; Sánchez, C.L.; Meares, G.P. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Inflammation in the Central Nervous System. Mol Neurodegener 2017, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, A.Y.-L.; de la Fuente, E.; Walter, P.; Shuman, M.; Bernales, S. The Unfolded Protein Response during Prostate Cancer Development. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews 2009, 28, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.S. GRP78 Induction in Cancer: Therapeutic and Prognostic Implications. Cancer Res 2007, 67, 3496–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, P.M.; Tabbara, S.O.; Jacobs, L.K.; Manning, F.C.R.; Tsangaris, T.N.; Schwartz, A.M.; Kennedy, K.A.; Patierno, S.R. Overexpression of the Glucose-Regulated Stress Gene GRP78 in Malignant but Not Benign Human Breast Lesions. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2000, 59, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrasco, D.R.; Sukhdeo, K.; Protopopova, M.; Sinha, R.; Enos, M.; Carrasco, D.E.; Zheng, M.; Mani, M.; Henderson, J.; Pinkus, G.S.; et al. The Differentiation and Stress Response Factor XBP-1 Drives Multiple Myeloma Pathogenesis. Cancer Cell 2007, 11, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardif, K.D.; Mori, K.; Kaufman, R.J.; Siddiqui, A. Hepatitis C Virus Suppresses the IRE1-XBP1 Pathway of the Unfolded Protein Response. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279, 17158–17164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Jensen, G.; Yen, T.S. Activation of Hepatitis B Virus S Promoter by the Viral Large Surface Protein via Induction of Stress in the Endoplasmic Reticulum. J Virol 1997, 71, 7387–7392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Mehrian-Shai, R.; Chan, C.; Hsu, Y.-H.; Kaplowitz, N. Role of CHOP in Hepatic Apoptosis in the Murine Model of Intragastric Ethanol Feeding. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2005, 29, 1496–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammoun, H.L.; Chabanon, H.; Hainault, I.; Luquet, S.; Magnan, C.; Koike, T.; Ferré, P.; Foufelle, F. GRP78 Expression Inhibits Insulin and ER Stress–Induced SREBP-1c Activation and Reduces Hepatic Steatosis in Mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2009, 119, 1201–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, U.; Cao, Q.; Yilmaz, E.; Lee, A.-H.; Iwakoshi, N.N.; Özdelen, E.; Tuncman, G.; Görgün, C.; Glimcher, L.H.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Links Obesity, Insulin Action, and Type 2 Diabetes. Science (1979) 2004, 306, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukano, H.; Gotoh, T.; Endo, M.; Miyata, K.; Tazume, H.; Kadomatsu, T.; Yano, M.; Iwawaki, T.; Kohno, K.; Araki, K.; et al. The Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-C/EBP Homologous Protein Pathway-Mediated Apoptosis in Macrophages Contributes to the Instability of Atherosclerotic Plaques. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2010, 30, 1925–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katayama, T.; Imaizumi, K.; Sato, N.; Miyoshi, K.; Kudo, T.; Hitomi, J.; Morihara, T.; Yoneda, T.; Gomi, F.; Mori, Y.; et al. Presenilin-1 Mutations Downregulate the Signalling Pathway of the Unfolded-Protein Response. Nat Cell Biol 1999, 1, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, Y.; Soda, M.; Takahashi, R. Parkin Suppresses Unfolded Protein Stress-Induced Cell Death through Its E3 Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase Activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2000, 275, 35661–35664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Cabuy, E.; Caroni, P. A Role for Motoneuron Subtype–Selective ER Stress in Disease Manifestations of FALS Mice. Nat Neurosci 2009, 12, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, K.B.; Rizvi, S.I. Plant Polyphenols as Dietary Antioxidants in Human Health and Disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2009, 2, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Shokrzadeh; S. S. Saeedi Saravi The Chemistry, Pharmacology and Clinical Properties of Sambucus Ebulus: A Review. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 2010, 4, 95–103. [CrossRef]

- Jabbari, M.; Daneshfard, B.; Emtiazy, M.; Khiveh, A.; Hashempur, M.H. Biological Effects and Clinical Applications of Dwarf Elder ( Sambucus Ebulus L): A Review. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med 2017, 22, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasinov, O.; Kiselova-Kaneva, Y.; Ivanova, D. Sambucus Ebulus - from Traditional Medicine to Recent Studies. Scripta Scientifica Medica 2013, 45, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasinov, O.; Dincheva, I.; Badjakov, I.; Kiselova-Kaneva, Y.; Galunska, B.; Nogueiras, R.; Ivanova, D. Phytochemical Composition, Anti-Inflammatory and ER Stress-Reducing Potential of Sambucus Ebulus L. Fruit Extract. Plants 2021, 10, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Xu, S.; Giles, A.; Nakamura, K.; Lee, J.W.; Hou, X.; Donmez, G.; Li, J.; Luo, Z.; Walsh, K.; et al. Hepatic Overexpression of SIRT1 in Mice Attenuates Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Insulin Resistance in the Liver. The FASEB Journal 2011, 25, 1664–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Guo, X.; Xie, W.; Li, Y.; Ma, M.; Yuan, T.; Luo, B. Resveratrol Exerts an Anti-Apoptotic Effect on Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells Undergoing Cigarette Smoke Exposure. Mol Med Rep 2015, 11, 1752–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Xiao, W.; Li, B.; Jin, L.; Lian, J.; Zhou, L.; Liu, J. Inhibition of Cardiomyocytes Hypertrophy by Resveratrol Is Associated with Amelioration of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2016, 39, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Xia, X.; Rui, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Qin, L.; Han, S.; Wan, Z. The Combination of 1α,25dihydroxyvitaminD3 with Resveratrol Improves Neuronal Degeneration by Regulating Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, Insulin Signaling and Inhibiting Tau Hyperphosphorylation in SH-SY5Y Cells. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2016, 93, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.-J.; Liu, R.-B.; Wang, L.-K.; Ma, Y.-B.; Ding, S.-L.; Deng, F.; Hu, Z.-Y.; Wang, D.-B. Sirt3-Mediated Autophagy Contributes to Resveratrol-Induced Protection against ER Stress in HT22 Cells. Front Neurosci 2018, 12, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hong, S.-W.; Kwon, H.; Park, S.E.; Rhee, E.-J.; Park, C.-Y.; Oh, K.-W.; Park, S.-W.; Lee, W.-Y. Resveratrol, an Activator of SIRT1, Improves ER Stress by Increasing Clusterin Expression in HepG2 Cells. Cell Stress Chaperones 2019, 24, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Shu, L.; Song, G.; Ma, H. Resveratrol Reduces Liver Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Improves Insulin Sensitivity in Vivo and in Vitro. Drug Des Devel Ther 2019, Volume 13, 1473–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Dong, X.; Ding, M.; You, C.; Lin, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, M.; Xu, G.; Wang, G. Resveratrol Decreases High Glucose induced Apoptosis in Renal Tubular Cells via Suppressing Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Mol Med Rep 2020, 22, 4367–4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, S.E.; Buehne, K.L.; Besley, N.A.; Yang, P.; Silinski, P.; Hong, J.; Ryde, I.T.; Meyer, J.N.; Jaffe, G.J. Resveratrol Protects Against Hydroquinone-Induced Oxidative Threat in Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells. Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science 2020, 61, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xu, X.; Dong, W.; Yang, C.; Luo, Y.; He, Y.; Jiang, C.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J. DDIT3/CHOP Mediates the Inhibitory Effect of ER Stress on Chondrocyte Differentiation by AMPKα-SIRT1 Pathway. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2022, 1869, 119265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Hu, N.; Zhao, Y.; Lai, J.; Luo, X.; Liu, J. Resveratrol mediated Activation of SIRT1 Inhibits the PERK eIF2α ATF4 Pathway and Mitigates Bupivacaine induced Neurotoxicity in PC12 Cells. Exp Ther Med 2023, 26, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinta, S.J.; Poksay, K.S.; Kaundinya, G.; Hart, M.; Bredesen, D.E.; Andersen, J.K.; Rao, R. V. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress–Induced Cell Death in Dopaminergic Cells: Effect of Resveratrol. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience 2009, 39, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.-M.; Galson, D.L.; Roodman, G.D.; Ouyang, H. Resveratrol Triggers the Pro-Apoptotic Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response and Represses pro-Survival XBP1 Signaling in Human Multiple Myeloma Cells. Exp Hematol 2011, 39, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, C.; Pan-Castillo, B.; Valls, C.; Pujadas, G.; Garcia-Vallve, S.; Arola, L.; Mulero, M. Resveratrol Enhances Palmitate-Induced ER Stress and Apoptosis in Cancer Cells. PLoS One 2014, 9, e113929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraj, S.; Sun, Y.; Sukumaran, P.; Singh, B.B. Resveratrol Activates Autophagic Cell Death in Prostate Cancer Cells via Downregulation of STIM1 and the MTOR Pathway. Mol Carcinog 2016, 55, 818–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Kim, S.; Hwang, K.; Kang, J.; Choi, K. Resveratrol Induced Reactive Oxygen Species and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress mediated Apoptosis, and Cell Cycle Arrest in the A375SM Malignant Melanoma Cell Line. Int J Mol Med 2018, 42, 1427–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Zhou, X.; Gu, M.; Jiao, W.; Yu, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Yang, J.; Ji, F. Resveratrol Synergizes with Cisplatin in Antineoplastic Effects against AGS Gastric Cancer Cells by Inducing Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress mediated Apoptosis and G2/M Phase Arrest. Oncol Rep 2020, 44, 1605–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Lin, H.; Chuang, C.; Wang, P.; Wan, H.; Lee, M.; Kao, M. Resveratrol Alleviates Nuclear Factor-κB-mediated Neuroinflammation in Vasculitic Peripheral Neuropathy Induced by Ischaemia–Reperfusion via Suppressing Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2019, 46, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ge, S.; Xiong, W.; Xue, Z. Effects of Resveratrol Pretreatment on Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Cognitive Function after Surgery in Aged Mice. BMC Anesthesiol 2018, 18, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.-R.; Ren, Y.-L.; Liu, W.-X.; Hu, Y.-J.; Zheng, J.-S.; Xu, Y.; Wang, G. Resveratrol Prevents Hepatic Steatosis and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Regulates the Expression of Genes Involved in Lipid Metabolism, Insulin Resistance, and Inflammation in Rats. Nutrition Research 2015, 35, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, R.M.; Hernandez, F.; Puerta, N.; De Angulo, G.; Webster, K.A.; Vanni, S. Resveratrol Augments ER Stress and the Cytotoxic Effects of Glycolytic Inhibition in Neuroblastoma by Downregulating Akt in a Mechanism Independent of SIRT1. Exp Mol Med 2016, 48, e210–e210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, S.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, G.; Bu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, X. Resveratrol and Caloric Restriction Prevent Hepatic Steatosis by Regulating SIRT1-Autophagy Pathway and Alleviating Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in High-Fat Diet-Fed Rats. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0183541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardid-Ruiz, A.; Ibars, M.; Mena, P.; Del Rio, D.; Muguerza, B.; Bladé, C.; Arola, L.; Aragonès, G.; Suárez, M. Potential Involvement of Peripheral Leptin/STAT3 Signaling in the Effects of Resveratrol and Its Metabolites on Reducing Body Fat Accumulation. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Cao, W.; Chen, X.; Fang, S. Resveratrol Alleviates Inflammatory Injury and Enhances the Apoptosis of Fibroblast like Synoviocytes via Mitochondrial Dysfunction and ER Stress in Rats with Adjuvant Arthritis. Mol Med Rep 2019, 20, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, A.; Romeo, M.A.; Benedetti, R.; Masuelli, L.; Bei, R.; Gilardini Montani, M.S.; Cirone, M. New Insights into Curcumin- and Resveratrol-Mediated Anti-Cancer Effects. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecht, J.T.; Veerisetty, A.C.; Wu, J.; Coustry, F.; Hossain, M.G.; Chiu, F.; Gannon, F.H.; Posey, K.L. Primary Osteoarthritis Early Joint Degeneration Induced by Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Is Mitigated by Resveratrol. Am J Pathol 2021, 191, 1624–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totonchi, H.; Mokarram, P.; Karima, S.; Rezaei, R.; Dastghaib, S.; Koohpeyma, F.; Noori, S.; Azarpira, N. Resveratrol Promotes Liver Cell Survival in Mice Liver-Induced Ischemia-Reperfusion through Unfolded Protein Response: A Possible Approach in Liver Transplantation. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 2022, 23, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettaieb, A.; Vazquez Prieto, M.A.; Rodriguez Lanzi, C.; Miatello, R.M.; Haj, F.G.; Fraga, C.G.; Oteiza, P.I. (−)-Epicatechin Mitigates High-Fructose-Associated Insulin Resistance by Modulating Redox Signaling and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Free Radic Biol Med 2014, 72, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Seo, Y.H.; Jang, J.-H.; Jeong, C.-H.; Lee, S.; Jeong, G.-S.; Park, B. Epicatechin Prevents Methamphetamine-Induced Neuronal Cell Death via Inhibition of ER Stress. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2019, 27, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.-Y.; Li, Z.-Y.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Z.-H.; Jin, J. The Attenuation of Chlorogenic Acid on Oxidative Stress for Renal Injury in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Nephropathy Rats. Arch Pharm Res 2016, 39, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Dong, J.; Nie, J.; Zhu, J.-X.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q.; Chen, J.-Y.; Xia, J.-M.; Shuai, W. Amelioration of Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis by Chlorogenic Acid through Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Inhibition. Apoptosis 2017, 22, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Miao, L.; Zhang, H.; Wu, G.; Zhang, Z.; Lv, J. Chlorogenic Acid against Palmitic Acid in Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Mediated Apoptosis Resulting in Protective Effect of Primary Rat Hepatocytes. Lipids Health Dis 2018, 17, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazaz, I.O.; Demir, S.; Kerimoglu, G.; Colak, F.; Turkmen Alemdar, N.; Yilmaz Dogan, S.; Bostan, S.; Mentese, A. Chlorogenic Acid Ameliorates Torsion/Detorsion-Induced Testicular Injury via Decreasing Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. J Pediatr Urol 2022, 18, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preetha Rani, M.R.; Salin Raj, P.; Nair, A.; Ranjith, S.; Rajankutty, K.; Raghu, K.G. In Vitro and in Vivo Studies Reveal the Beneficial Effects of Chlorogenic Acid against ER Stress Mediated ER-Phagy and Associated Apoptosis in the Heart of Diabetic Rat. Chem Biol Interact 2022, 351, 109755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sari, I.; Moch Rizal, D.; Afiyah Syarif, R. The Effect of Chlorogenic Acid on Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Steroidogenesis in the Testes of Diabetic Rats: Study of MRNA Expressions of GRP78, XBP1s, 3β-HSD, and 17β-HSD. BIO Web Conf 2022, 49, 01001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam Moslehi; Tahereh Komeili-Movahhed; Mostafa Ahmadian; Mahdieh Ghoddoosi; Fatemeh Heidari Chlorogenic Acid Attenuates Liver Apoptosis and Inflammation in Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Mice. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2023, 26, 478–485. [CrossRef]

- Boonyong, C.; Angkhasirisap, W.; Kengkoom, K.; Jianmongkol, S. Different Protective Capability of Chlorogenic Acid and Quercetin against Indomethacin-Induced Gastrointestinal Ulceration. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2023, 75, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, P.; Yang, T.; Ning, C.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, T.; Gao, Z.; Fu, S. Chlorogenic Acid Attenuates Cardiac Hypertrophy via Up-regulating Sphingosine-1-phosphate Receptor1 to Inhibit Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. ESC Heart Fail 2024, 11, 1580–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Huang, Y.; Luo, G.; Yang, X.; Huang, W. Cyanidin-3-O-Glucoside Attenuates High Glucose–Induced Podocyte Dysfunction by Inhibiting Apoptosis and Promoting Autophagy via Activation of SIRT1/AMPK Pathway. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2021, 99, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambini, J.; Inglés, M.; Olaso, G.; Lopez-Grueso, R.; Bonet-Costa, V.; Gimeno-Mallench, L.; Mas-Bargues, C.; Abdelaziz, K.M.; Gomez-Cabrera, M.C.; Vina, J.; et al. Properties of Resveratrol: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies about Metabolism, Bioavailability, and Biological Effects in Animal Models and Humans. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015, 2015, 837042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleas, G.J.; Diamandis, E.P.; Goldberg, D.M. Resveratrol: A Molecule Whose Time Has Come? And Gone? Clin Biochem 1997, 30, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Si, X.; Tan, H.; Zang, Z.; Tian, J.; Shu, C.; Sun, X.; Li, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Meng, X.; et al. Cyanidin-3-O-Glucoside and Its Phenolic Metabolites Ameliorate Intestinal Diseases via Modulating Intestinal Mucosal Immune System: Potential Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2023, 63, 1629–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frountzas, M.; Karanikki, E.; Toutouza, O.; Sotirakis, D.; Schizas, D.; Theofilis, P.; Tousoulis, D.; Toutouzas, K.G. Exploring the Impact of Cyanidin-3-Glucoside on Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Investigating New Mechanisms for Emerging Interventions. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 9399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindranath, M.H.; Saravanan, T.S.; Monteclaro, C.C.; Presser, N.; Ye, X.; Selvan, S.R.; Brosman, S. Epicatechins Purified from Green Tea (Camellia Sinensis) Differentially Suppress Growth of Gender-Dependent Human Cancer Cell Lines. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2006, 3, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoyama, A.T.; Santin, J.R.; Machado, I.D.; de Oliveira e Silva, A.M.; de Melo, I.L.P.; Mancini-Filho, J.; Farsky, S.H.P. Antiulcerogenic Activity of Chlorogenic Acid in Different Models of Gastric Ulcer. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2013, 386, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Kaufman, R.J. From Acute ER Stress to Physiological Roles of the Unfolded Protein Response. Cell Death Differ 2006, 13, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwecka, N.; Rozpędek-Kamińska, W.; Wawrzynkiewicz, A.; Pytel, D.; Diehl, J.A.; Majsterek, I. The Structure, Activation and Signaling of IRE1 and Its Role in Determining Cell Fate. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutkowski, D.T.; Kaufman, R.J. A Trip to the ER: Coping with Stress. Trends Cell Biol 2004, 14, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabas, I.; Ron, D. Integrating the Mechanisms of Apoptosis Induced by Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Nat Cell Biol 2011, 13, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author(s) | Year | Experimental Model | Altered Expression or Activity of ER Stress Markers | Dosage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinta et al. [36] | 2009 | In vitro (dopaminergic N27 cells) | ↑cleavage of caspases 7 and 3 ↑GRP78 expression ↑GRP94 expression ↑CHOP expression ↑p-eIF2α expression |

50-250 μM |

| Wang et al. [37] | 2011 | In vitro (multiple myeloma cell lines ANBL-6, OPM2, MM.15) | ↑JNK phosphorylation ↑CHOP expression ↑XBP1 mRNA splicing ↓transcription of XBP1s |

100 μM |

| Li et al. [25] | 2011 | In vitro (tunicamycin-induced ER stress in HepG2 cells) | ↓XBP1 mRNA splicing ↓GRP78 expression ↓CHOP expression |

10 μM |

| Rojas et al. [38] | 2014 | In vitro (palmitate-induced ER stress in HepG2 cells) | ↑XBP1 mRNA splicing ↑CHOP expression |

100 μM |

| Zhang et al. [26] | 2015 | In vitro (cigarette smoke extract-induced apoptosis in cultured human bronchial epithelial cells) | ↓CHOP expression ↓caspases 3 and 4 expression |

20 µmol/l |

| Pan et al. [44] | 2015 | In vivo (high-fat diet-fed rats) | ↓ATF4 expression ↓GRP78 expression ↓CHOP expression ↓GRP78 expression ↓p-PERK expression |

100 mg/kg |

| Graham et al. [45] | 2016 | In vitro (2-deoxy-D-glucose inhibition of glycolysis in neuroblastoma cells) | ↑CHOP expression ↓GRP78 expression ↓GRP94 expression |

10 μM |

| Lin et al. [27] | 2016 | In vitro (neonatal rat cardiomyocytes) | ↓GRP78 expression ↓GRP94 expression ↓CHOP expression |

50 μM |

| Cheng et al. [28] | 2016 | In vitro (tunicamycin and Aβ25-35 induced ER stress in SH-SYSY cells) | ↓GRP78 expression ↓CHOP expression ↓p-eIF2α expression |

25 μM |

| Selvaraj et al. [39] | 2016 | In vitro (PC3 and DU145 prostate cancer cell lines) | ↑CHOP expression | 100 μM |

| Ding et al. [46] | 2017 | In vivo (high-fat diet-fed rats) | ↓GRP78 expression ↓CHOP expression |

200 mg/kg |

| Yan et al. [29] | 2018 | In vitro (tunicamycin-induced ER stress in neuronal HT22 cells) | ↓GRP78 expression ↓CHOP expression ↓caspase 12 expression |

50 μM |

| Heo et al. [40] | 2018 | In vitro (A375SM melanoma cells) | ↑p-eIF2α expression ↑CHOP expression |

10 μM |

| Ardid-Ruiz et al. [47] | 2018 | In vivo (diet induced obesity in rats) | ↓XBP1s expression | 200 mg/kg |

| Wang et al. [43] | 2018 | In vivo (surgical mice model) | ↓GRP78 expression ↓XBP1 expression ↓PERK expression ↓IRE1 expression |

100 mg/kg |

| Lee et al. [30] | 2019 | In vitro (tunicamycin-induced ER stress in HepG2 cells) | ↓PERK expression ↓IRE1 expression ↓CHOP expression ↑ERAD factors expression |

10, 50 and 100 μM |

| Zhao et al. [31] | 2019 | In vivo (high-fat diet-fed mice) In vitro (palmitic acid-induced insulin-resistant HepG2 cells) |

in vivo model – ↓p-PERK expression and ↓ATF4 expression in vitro model – ↑p-PERK expression, ↑ATF4 expression, ↓ATF6 expression (at 50 and 100 μM) and ↓ p-PERK expression, ↓ATF4 expression, ↑ATF6 expression (at 20 μM) | 60 mg/kg (in vivo model) 20, 50 and 100 μM (in vitro model) |

| Lu et al. [48] | 2019 | In vitro (fibroblast-like synoviocytes treated with H2O2) | ↑CHOP expression ↑caspase 12 and caspase 3 expression |

50, 100, 200 and 400 μM |

| Pan et al. [42] | 2019 | In vivo (induced vasculitic peripheral neuropathy by ischaemia–reperfusion in rats) | ↓p-PERK expression ↓p-IRE1 expression ↓ATF6 expression |

20 and 40 mg/кg |

| Zhang et al. [32] | 2020 | In vivo (db/db mice) In vitro (high glucose induced ER stress in NRK-52E cells) |

↓GRP78 expression ↓CHOP expression ↓caspase 12 expression |

20 μM (in vitro model) 40 mg/ kg (in vivo model) |

| Ren et al. [41] | 2020 | In vitro (AGS stomach cancer cell line) | ↑GRP78 expression ↑p-eIF2α expression ↑CHOP expression |

20 μM |

| Neal et al. [33] | 2020 | In vitro (retinal pigment cells treated with hydroquinone) | ↑XBP1 expression ↑CHOP expression |

15 and 30 μM |

| Arena et al. [49] | 2021 | In vitro (Her-2 positive breast cancer and salivary gland cancer cell lines) | ↑CHOP expression | 15 μM |

| Hecht et al. [50] | 2021 | In vivo (model of primary osteoarthritis in mice) | ↓CHOP expression | 0.25 g/L |

| Yu et al. [34] | 2022 | In vitro (tunicamycin-induced ER stress in chondrocytes) | ↓CHOP expression | 50 μM |

| Totonchi еt al. [51] | 2022 | In vivo (mice liver-induced ischemia-reperfusion) | ↓GRP78 expression ↓PERK expression ↓IRE1α expression ↓CHOP expression ↓XBP1 expression |

0.02 and 0.2 mg/kg |

| Luo et al. [35] | 2023 | In vitro (bupivacaine-induced cytotoxicity in PC12 rat adrenal pheochromocytoma cells) |

↓p-PERK expression ↓p-eIF2α expression ↓ATF4 expression |

20 µM |

| Author(s) | Year | Experimental Model | ER Stress Modulating Substance |

Altered Expression or Activity of ER Stress Markers | Dosage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thummayot et al. [38] | 2016 | In vitro (Aβ 25-35 induced neuronal cell death in SK-N-SH cells) | Cyanidin-3-o-glucoside | ↓GRP78 expression ↓p-PERK expression ↓p-eIF2α expression ↓ IRE1 expression ↓ XBP1 expression ↓ ATF6 expression ↓ CHOP expression |

0.2; 2; 18 and 20 µM |

| Chen et al. [40] | 2022 | In vitro (treated with palmitate isolated mouse pancreatic islets and INS-1E cells) | Cyanidin-3-o-glucoside | ↓ CHOP expression | 12,5; 25 and 50 µM |

| Tu et al. [41] | 2022 | In vivo (induced perodontitis in rats) | Cyanidin-3-o-glucoside | ↓ CHOP expression ↓ JNK and p-JNK expression |

3 or 9 mg/kg |

| Peng et al. [42] | 2022 | In vitro (blue light-irradiated retinal pigment epithelial cells) | Cyanidin-3-o-glucoside | ↓ATF4 expression ↓ CHOP expression |

10 and 25 μM |

| Bettaieb et al. [52] | 2014 | In vivo (high-fructose diet-fed rats) | Epicatechin | ↓p-PERK expression ↓p-IRE1 expression ↓XBP1 splicing |

20 mg/kg |

| Kang et al. [53] |

2019 | In vitro (methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity in HT22 hippocampal neuronal cells) | Epicatechin | ↓CHOP expression | 10 and 20 μM |

| Ye et al. [54] | 2016 | In vivo (streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy in rats) | Chlorogenic acid | ↓CHOP expression ↓ATF6 expression ↓p-eIF2α expression ↓p- PERK expression |

5 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg, 20 mg/kg |

| Wang et al. [55] | 2017 | In vivo (bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice), in vitro (pulmonary fibroblasts and RLE-6TN cells) | Chlorogenic acid | ↓GRP78 expression ↓CHOP expression ↓p-PERK expression ↓ATF6 expression ↓caspases 9, 3 and 12 expression |

15 mg/kg, 30 mg/kg, 60 mg/kg |

| Zhang et al. [56] | 2018 | In vitro (thapsigargin and palmitic acid-induced ER stress in rat hepatocytes) | Chlorogenic acid | ↓GRP78 expression ↓GRP94 expression ↓CHOP expression |

5 μmol/l |

| Kazaz et al. [57] | 2022 | In vivo (torsion/detorsion-induced testicular injury in rats) | Chlorogenic acid | ↓GRP78 expression ↓ATF6 expression ↓CHOP expression |

100 mg/kg |

| Rani et al. [58] | 2022 | in vitro (model of hyperglycemia in H9c2 embryonic rat heart cells) | Chlorogenic acid | ↓p-PERK expression ↓p-eIF2α expression ↓ATF4 expression ↓p-IRE1 expression ↓TRAF2 expression ↓p-JNK expression ↓XBP1 expression ↓ATF6 expression |

10 and 30 μM |

| Sari et al. [59] | 2022 | In vivo (diabetic model in rats) | Chlorogenic acid | ↓GRP78 expression ↓ XBP1 expression |

12.5 mg/kg, 25 mg/kg and 50 mg/kg |

| Moslehi et al. [60] | 2023 | In vivo (tunicamycin-induced ER stress in mice) | Chlorogenic acid | ↓GRP78 expression ↓PERK expression ↓IRE1 expression ↓caspase 3 expression |

20 and 50 mg/kg |

| Boonyong et al. [61] | 2023 | In vivo (indomethacin-induced gastrointestinal ulcer in rats) | Chlorogenic acid | ↓p-PERK expression ↓p-eIF2α expression ↓ATF-4 expression ↓CHOP expression |

100 mg/kg |

| Ping et al. [62] | 2024 | In vitro (isoproterenol stimulated H9c2 myocardial cells) In vivo (isoproterenol stimulated rats) |

Chlorogenic acid | ↓GRP78 expression ↓p-PERK expression ↓CHOP expression ↓caspases 12, 3 and 9 expression |

90 mg/kg (in vivo model) 50 μM (in vitro model) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).