1. Introduction

Hybrid wireless sensor networks (WSNs), comprising both mobile and static sensor nodes, offer robust solutions for monitoring and environmental data collection. However, these networks face critical security threats, including clone attacks, where adversaries replicate legitimate nodes to compromise network functionality [

1]. Traditional clone detection techniques often depend on knowledge of network topology or geographic locations of nodes, which is not always feasible in hybrid WSNs. This paper proposes a novel multifaceted clone detection mechanism leveraging a Distributive Correlated Neural Network (DCNN) algorithm [

2]. The DCNN algorithm dynamically identifies and isolates cloned nodes without requiring prior knowledge of network structure, enabling it to operate effectively in diverse, real-world environments. By parallelizing core detection processes, this method enhances detection speed and accuracy, offering a scalable, adaptive solution to safeguard hybrid WSNs against clone attacks [

3].

The

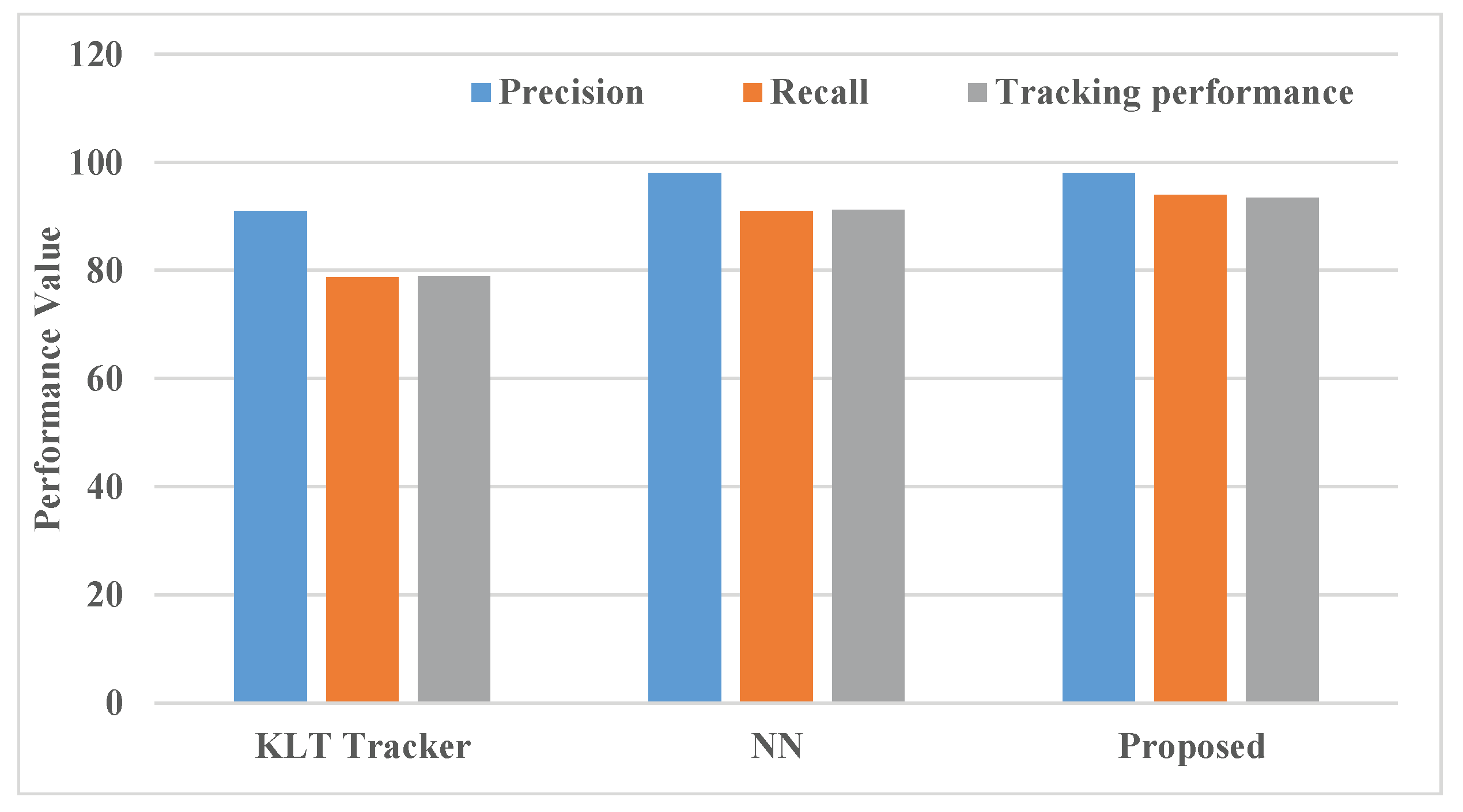

Figure 1 gives the system’s work flow diagram of the proposed work. Wireless sensor networks (WSNs) have gained a great deal of attention in the past decade due to their wide range of application areas and formidable design challenges. In general, wireless sensor networks consist of hundreds and thousands of low-cost, resource-constrained, distributed sensor nodes, which usually scatter in the surveillance area randomly, working without attendance [

4]. Examples of WSNs applications are already present in health care, navigation, rescue, intelligent transportation, social networking, gaming application fields, and critical infrastructure protection. In several military and civil applications, WSNs are often unattended and deployed in harsh environments [

5]. Due to their operating nature, WSNs are hence subject to several threats. For instance, an adversary can easily eavesdrop all network communications, as well as physically capture nodes and tamper with them (sensors are commonly assumed to be not tamper proof). A WSN on average consists of a hefty number of low costs, low power, and multifunctional wireless sensor nodes, with sensing, wireless communications and computation capabilities [

6].

Wireless sensor networks (WSNs) comprise a collection of sensor nodes that communicate wirelessly over short distances and work collaboratively to perform common tasks such as environmental monitoring, military surveillance, and industrial process automation. These sensor nodes generally fall into two categories:

battery-powered mobile nodes and

energy-harvesting static nodes. Mobile sensor nodes are advantageous in achieving extended network lifetime and high reliability, while static sensor nodes—although more durable—incur higher deployment costs due to the inclusion of energy-harvesting components [

7].

The cost disparity arises because static nodes integrate specialized energy-harvesting modules, which are typically more expensive than the conventional mobile units. Integrating both types of nodes in a

heterogeneous WSN offers an effective strategy for reconciling the trade-offs between operational longevity and deployment cost. A hybrid network of mobile and static sensor nodes enables the design of routing mechanisms based on a comprehensive cost function. This function accounts for key performance metrics including

end-to-end path reliability,

energy consumption, and

overall cost, thereby ensuring a satisfactory quality of service (QoS) for various applications operating in such networks [

8].

When these networks are deployed in hostile or adversarial environments, security becomes a paramount concern. One of the most serious threats in mobile WSNs is the

clone attack (also known as the

replica attack). In this attack, adversaries capture a few sensor nodes, extract their firmware and cryptographic credentials, and replicate them across multiple off-the-shelf sensor devices. Due to cost limitations, most WSN nodes do not incorporate tamper-resistant hardware, making them vulnerable to physical compromise [

9].

Cloned nodes, appearing identical to legitimate ones, can seamlessly integrate into the network and significantly expand an attacker’s influence. These malicious replicas can be strategically placed to manipulate data collection, disrupt routing paths, or engage in collaborative attacks that undermine the network's operations. Many clones can give an attacker control over critical parts of the network, potentially affecting the entire system. Moreover, clone attacks can act as enablers for various internal threats, intensifying their impact [

10].

This research focuses on enhancing the

security framework of WSNs, particularly in mitigating the threat of clone attacks. The clone attack involves duplicating a legitimate node’s identity, cryptographic materials, and injecting additional malicious code aligned with the attacker’s objectives. These rogue nodes can then interact with genuine nodes while being falsely recognized as legitimate, making detection difficult. Once inside, they can perform a variety of malicious operations—such as creating

black hole attacks, initiating

wormhole tunnels, injecting or altering data during aggregation, or leaking sensitive information [

11,

12].

What makes the clone attack particularly dangerous is its

low operational cost for adversaries. Only a single node needs to be compromised to produce numerous replicas. Detection is inherently difficult because most sensor nodes have knowledge limited to their local topology and routing context, making it hard to identify spatially dispersed replicas sharing the same identity [

13].

2. Nature of Research& Literature Review

Technological advancements have enabled the development of compact, low-cost sensor nodes using off-the-shelf hardware components. A

wireless sensor network is a decentralized and self-configuring network comprising these nodes, which are constrained in terms of power, memory, and processing capabilities. Despite their limitations, these nodes coordinate to achieve common objectives within the network [

14].

WSNs are frequently deployed in environments that are harsh, remote, or potentially hazardous—areas that are often inaccessible to human operators. Common applications include

industrial instrumentation,

pollution monitoring,

structural health assessment,

traffic management, and

remote healthcare monitoring. Additionally, WSNs are widely used in smart buildings and homes for controlling temperature, lighting, humidity, and motion detection [

15].

Despite their versatility and practical importance, WSNs face significant

security vulnerabilities. Given the economic infeasibility of equipping each sensor with tamper-proof hardware, nodes remain susceptible to physical compromise. Once compromised, attackers can reprogram nodes and exploit them for various purposes. Although numerous protocols have been developed to counteract threats related to localization, time synchronization, and secure routing, most are

attack-resilient rather than

attack-eliminating [

16].

Therefore, in mission-critical applications—such as battlefield surveillance—where sensor networks may be left unattended, the

prompt detection and revocation of compromised nodes becomes essential. Attack-resilient mechanisms alone are insufficient; effective strategies must aim to

identify, isolate, and neutralize the sources of attacks to minimize operational disruption and reduce the costs associated with prolonged security breaches [

17].

Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs) are increasingly deployed in hostile and remote environments due to their ability to operate autonomously and perform critical monitoring tasks. In such contexts, the presence of adversaries is a realistic threat. For example, WSNs are employed to detect firearm usage, monitor illicit crop cultivation, prevent drug and weapon trafficking, identify unauthorized human movements, and even observe nuclear activity in politically sensitive regions. Given these high-stakes applications,

securing WSNs becomes imperative to ensure the integrity, reliability, and continuity of their operations [

18].

The unattended nature of WSNs, particularly in adversarial environments, exposes them to a wide range of physical and cyber attacks. Without constant human oversight, attackers can exploit the system through various means, such as physical tampering or sophisticated network intrusions. Common threats include

clone attacks, where compromised nodes are duplicated and redeployed to act maliciously, as well as

radio jamming,

denial of service (DoS),

node outages,

eavesdropping, and

Sybil attacks—where a single device mimics multiple identities. Other potent threats include

sinkhole attacks,

wormhole attacks, and

selective forwarding, all of which disrupt data transmission or compromise the integrity of information being relayed [

19].

These attacks can be classified into two broad categories: layer-dependent and layer-independent threats. Layer-dependent attacks are closely associated with the OSI model and exploit specific functionalities of network communication layers. For instance, routing protocols may be targeted to misdirect data, while localization protocols can be manipulated to falsify node positions. Similarly, attacks on synchronization protocols can cause timing errors, and data aggregation protocols can be exploited to inject false or misleading information.

On the other hand, layer-independent attacks are more generalized and

application-independent, meaning they are not confined to specific OSI layers and can affect a broad range of WSN applications. These include, but are not limited to, object tracking, environmental monitoring, early fire detection, and battlefield surveillance. Such attacks do not rely on any particular network service or protocol and can universally disrupt multiple application domains [

20]. The classification of these attacks is often illustrated using comprehensive taxonomies or models (e.g.,

Figure 1 in related literature), which help researchers understand the attack surfaces and associated vulnerabilities.

To mitigate these diverse threats, several

security mechanisms have been developed. For routing-layer attacks, various

secure routing protocols aim to ensure data reaches its destination without being rerouted or dropped. In cases of

false data injection,

authentication frameworks have been introduced to verify the legitimacy of transmitted information. To secure

data aggregation, encryption-based and integrity-aware aggregation protocols have been proposed, which protect against malicious manipulation of collective data. Similarly,

robust localization and time synchronization mechanisms are implemented to counter attacks targeting spatial or temporal accuracy within the network [

21].

However, a critical limitation of most existing techniques is that they are

attack-resilient rather than

attack-eliminating. They focus on maintaining functionality in the presence of threats rather than identifying and neutralizing the root cause of the attack. While such resilience provides a certain degree of reliability, it is not sufficient in scenarios where long-term deployment and critical decision-making depend on accurate and uncompromised data. Therefore, there is a growing need for

proactive detection and immediate revocation of malicious or compromised nodes. By identifying the origin of an attack and eliminating it quickly, the network can minimize operational disruptions and reduce the costs and damages associated with prolonged exposure to threats [

22].

In summary, while WSNs are invaluable for mission-critical monitoring, especially in adversarial environments, their security remains a fundamental challenge. It is essential to shift from merely surviving attacks to actively defending against them by integrating intelligent, autonomous, and robust detection and revocation mechanisms. This proactive approach ensures greater trustworthiness and operational continuity in real-world applications where failures are not an option.

Figure 2 provides a structured classification of various attacks in Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs). Among these, a particularly alarming physical-layer attack is the

clone attack, also referred to as the

identity replication attack. In this attack, an adversary initially captures one or more legitimate sensor nodes. Once these nodes are physically accessed, the attacker extracts their unique identifiers (IDs), secret cryptographic material, and code. Using this extracted information, the adversary fabricates multiple replicas, or "clones," of the captured nodes and then strategically deploys these clones throughout the network. This sequence—comprising node capture, cloning, and deployment—poses a severe threat to network integrity, and is effectively illustrated in

Figure 2 [

23].

The severity of clone attacks lies in their

simplicity and high impact. Due to the limited tamper-resistance in most commercial sensor nodes, attackers can compromise a device using basic tools and extract its data, including memory contents, in less than a minute. This vulnerability stems from the cost constraints associated with embedding tamper-proofing mechanisms in each node. Once clones are deployed, they can either mimic benign behavior to gather sensitive data or behave maliciously to disrupt network operations [

24].

These clone nodes may selectively be reprogrammed by the adversary to conduct insider attacks such as injecting false data, suppressing legitimate messages, or misleading the aggregation process. They can also engage in more complex attacks like black hole creation, where all data directed through them is dropped, or wormhole attacks, in which clones collaborate across distant parts of the network to create false routing paths. Additionally, these clones can exploit node revocation protocols—which are often based on threshold voting—to falsely trigger the removal of legitimate nodes, further weakening the network.

The insidious nature of clone attacks is amplified by the fact that these replicated nodes appear

authentic to their neighbors. Since they carry valid IDs and credentials, other nodes within communication range accept them as trustworthy peers. This makes the detection of such attacks extremely challenging. If not identified and mitigated quickly, these clones can alter network protocols, compromise security mechanisms, and launch

persistent denial-of-service (DoS) or data-leakage attacks [

25].

Conventional security approaches—such as encryption, authentication, and access control—

are inadequate in preventing clone attacks. These mechanisms assume that all authenticated nodes are trustworthy, a presumption that fails when node credentials are compromised. As a result, there has been a growing body of research proposing clone detection schemes. Broadly, these techniques are classified into

radio-based and

network-based approaches. Notably, only a limited number of radio-based detection methods have been documented, such as the one discussed in [

26].

Attack Execution Stages:

Node Capture: Adversaries physically gain access to a sensor node, which lacks built-in mechanisms to detect physical intrusion (e.g., pressure, temperature, or voltage anomalies).

Memory Readout: After gaining access, the node's memory, including secret keys and program code, is extracted.

Cloning and Deployment: Replicated nodes with identical IDs and credentials are produced and strategically redeployed in the network.

Network Subversion: Clones manipulate routing and aggregation protocols, disrupt communication, and may even revoke legitimate nodes.

Static vs. Mobile WSNs: Impact on Clone Detection

WSNs are categorized as

static or

mobile, depending on the mobility of the sensor nodes. In

Static Wireless Sensor Networks (SWSNs), sensor nodes are immobile after deployment. Their fixed locations provide an advantage in clone detection: if the same node ID is detected in multiple physical locations, it clearly indicates the presence of a clone. Conversely, in

Mobile Wireless Sensor Networks (MWSNs), nodes can move independently, making position-based clone detection strategies inapplicable [

27].

Mobile sensor networks benefit from advances in robotics, allowing for autonomous movement and dynamic interactions with the physical environment. This mobility introduces flexibility in coverage and sensing, but it also complicates security enforcement. Unlike static networks where routing is often based on fixed paths or flooding protocols, mobile networks rely on

dynamic routing, which is inherently more susceptible to disruption by cloned nodes [

28].

Given the differing characteristics between static and mobile WSNs, clone detection strategies must be tailored accordingly. In static networks, clone detection can leverage location consistency, while in mobile networks, the detection must account for movement and time-based behavior.

Classification of Detection Techniques

For Static WSNs, clone detection techniques are broadly divided into:

-

Centralized Approaches:

- ○

Base Station-Based: The base station gathers information to identify conflicting node positions.

- ○

Key Usage-Based: Detection is based on inconsistencies in cryptographic key usage.

- ○

SET Operations-Based: Logical set operations identify duplications in identity claims.

- ○

Cluster Head-Based: Cluster heads monitor and report duplicate identities.

- ○

Neighborhood Social Signature-Based: Nodes create social signatures based on neighbor patterns.

-

Distributed Approaches:

- ○

Node-to-Network Broadcasting: Nodes broadcast their presence to detect duplicates.

- ○

Claimer-Reporter-Witness: Triplet-based schemes verify ID ownership.

- ○

Neighbor-Based: Local neighborhood monitoring detects ID replication.

- ○

Generation/Group-Based: Nodes belong to specific groups; replication is detected by group inconsistencies.

For Mobile WSNs, the techniques are:

-

Centralized:

- ○

Key Usage-Based: Similar to static networks, focused on cryptographic anomalies.

- ○

Node Speed-Based: Detects inconsistencies in node mobility behavior (e.g., a node appears in distant locations faster than physically possible).

-

Distributed:

- ○

Node Meeting-Based: Detection is based on meeting histories among nodes.

- ○

Mobility-Assisted: Uses mobile elements to assist in identity verification.

- ○

Information Exchange-Based: Nodes share identity observations to collaboratively identify clones [

30].

5. Significance of the Proposed Approaches

The increasing deployment of WSNs has brought with it a rise in security vulnerabilities, especially node clone attacks—where an adversary duplicates a captured node and places the clone strategically to disrupt the network. Although traditional authentication techniques are robust, they fall short in identifying these insider threats in mobile settings.

The key security requirements [

31] for WSNs—availability, authenticity, confidentiality, and data integrity—are seriously compromised in the presence of clone attacks. These cloned nodes, carrying authentic credentials, can bypass encryption, decryption, and authentication protocols just like original nodes.

Such replicas can enable an attacker to eavesdrop on communications, tamper with sensor data, trigger denial-of-service (DoS) attacks, inject false readings, manipulate aggregation processes, and jam network signals. As a result, the entire WSN can be destabilized, endangering both data security and network functionality.

Availability guarantees that network operations continue even under attack. However, with cloned nodes launching DoS attacks or signal jamming, service disruptions become inevitable. Authenticity is jeopardized because the network cannot distinguish between a legitimate node and its identical replica due to shared credentials. Confidentiality fails as cloned nodes gain access to sensitive or classified information. Integrity is threatened as attackers can alter or forge sensor data.

To evaluate these detection protocols, four primary metrics are considered:

Communication Overhead: The average number of messages a node transmits while sharing its location data.

Storage Overhead: The average memory used to save these location claims.

Detection Probability: The likelihood that a protocol successfully identifies and flags a clone node.

Detection Time: The latency between a clone's deployment and its detection.

Optimizing these parameters is crucial to ensure secure and efficient operation in mobile WSN environments.

8. Simulation Results

Simulations were carried out in the Python environment, the model was trained, tested & the results are presented in this section.

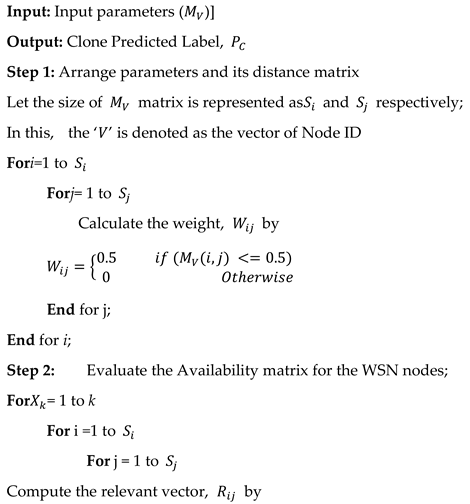

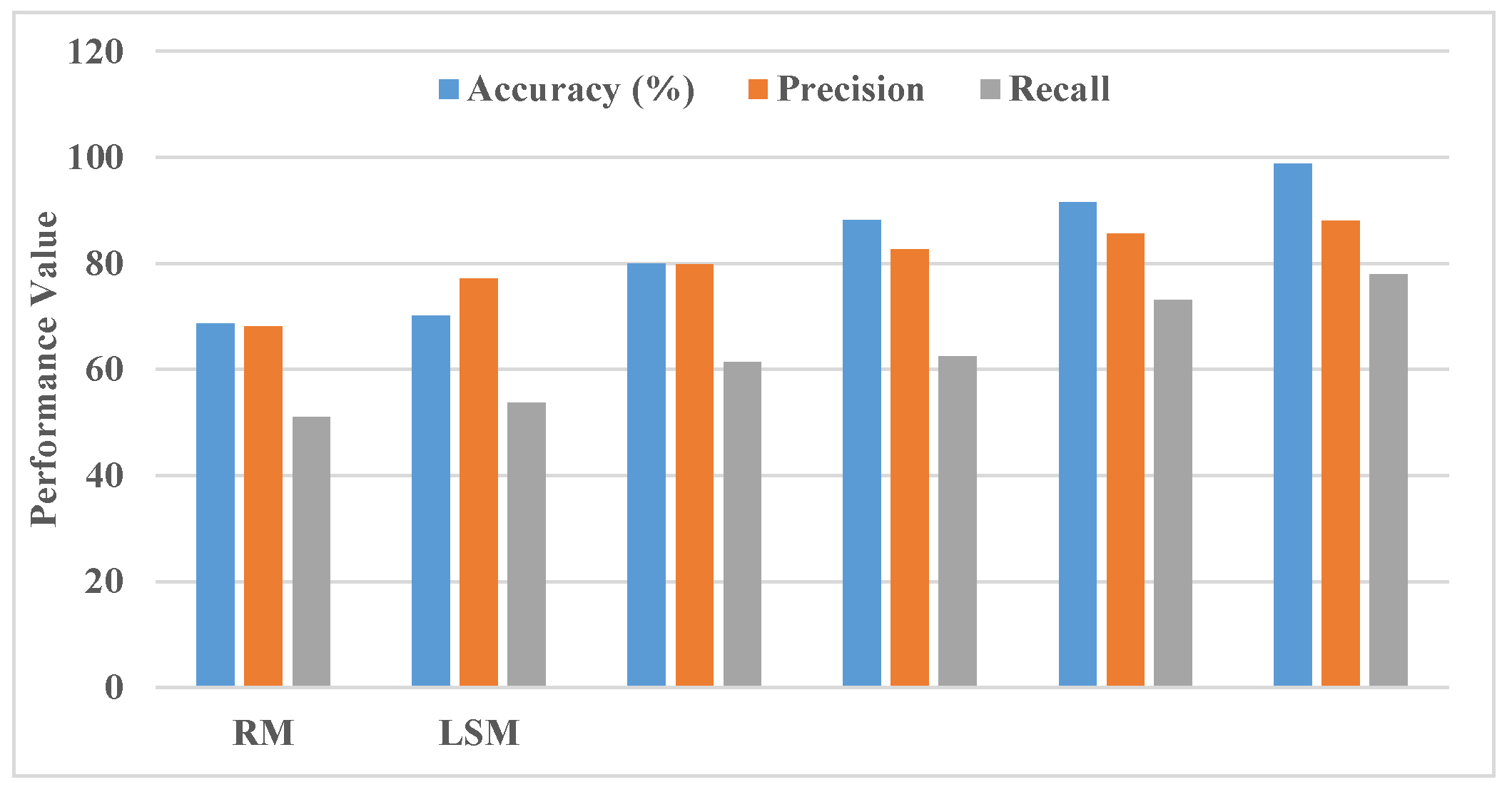

The results in the

Table 1 reveal a significant improvement in accuracy, precision, and recall for the proposed Distributive Correlated Neural Network (DCNN) algorithm in detecting cloned nodes in hybrid wireless sensor networks (WSNs). Compared with methods like RM, LSM, RAWL, TRAWL, and HRWZ, the DCNN algorithm demonstrates a marked increase in all performance metrics, achieving 98.3% accuracy, 0.91 precision, and 0.81 recall, which are the highest in the table. This improvement can be attributed to the DCNN algorithm’s ability to leverage distributive correlations and multifaceted clone detection without requiring detailed knowledge of network topology, allowing for a more adaptive response to dynamic network conditions.

In comparison, with [

1] in their work on distributed node replication detection achieved strong detection rates in WSNs, yet their method’s reliance on network topology limits its applicability in hybrid networks with both mobile and static nodes. This constraint likely impacts its adaptability and scalability, resulting in lower precision and recall when faced with complex, non-static networks. The DCNN, by contrast, benefits from a parallelized, topology-independent detection approach, allowing it to detect clone attacks with greater accuracy and efficiency, as shown by its improved metrics across the board. This distinction highlights the DCNN algorithm’s superior robustness and effectiveness in addressing clone detection challenges within hybrid WSNs which can be clearly seen in the

Figure 3.

The

Table 2 illustrates a substantial improvement in detection performance metrics (accuracy, precision, and recall) for the proposed Distributive Correlated Neural Network (DCNN) algorithm in detecting cloned nodes in hybrid wireless sensor networks (WSNs), especially when compared with previous methods such as RM, LSM, RAWL, TRAWL, and HRWZ. The proposed method reaches an accuracy of 98.9%, with precision and recall scores of 88 and 78, respectively, outperforming the highest-scoring previous method, HRWZ, which achieved 91.5% accuracy, 85.7% precision, and 73.1% recall, which can also be seen from graphical results in

Figure 4.

Compared with reference [

10], which focuses on clone detection through localized neighbor information, our DCNN algorithm shows marked improvements. Chessa and Santi's approach relies heavily on neighborhood-based verification, where clone detection can be affected by changes in node distribution and the limitations of localized information in highly dynamic or hybrid WSN environments. In contrast, the DCNN algorithm leverages a more holistic network approach, integrating distributive correlation and adaptive learning, which allows it to perform effectively regardless of node mobility or network topology changes. This adaptability leads to higher accuracy in clone detection and superior precision and recall, indicating that the DCNN method not only correctly identifies cloned nodes with higher reliability but also minimizes false positives.

The DCNN’s ability to analyze distributive data patterns and leverage multifaceted feature learning provides a robust defense against clone attacks, resulting in increased detection accuracy and efficiency in hybrid networks. This makes it particularly well-suited for complex WSN applications where both static and mobile nodes are present, outperforming traditional neighborhood-based methods such as those presented in reference [

10].

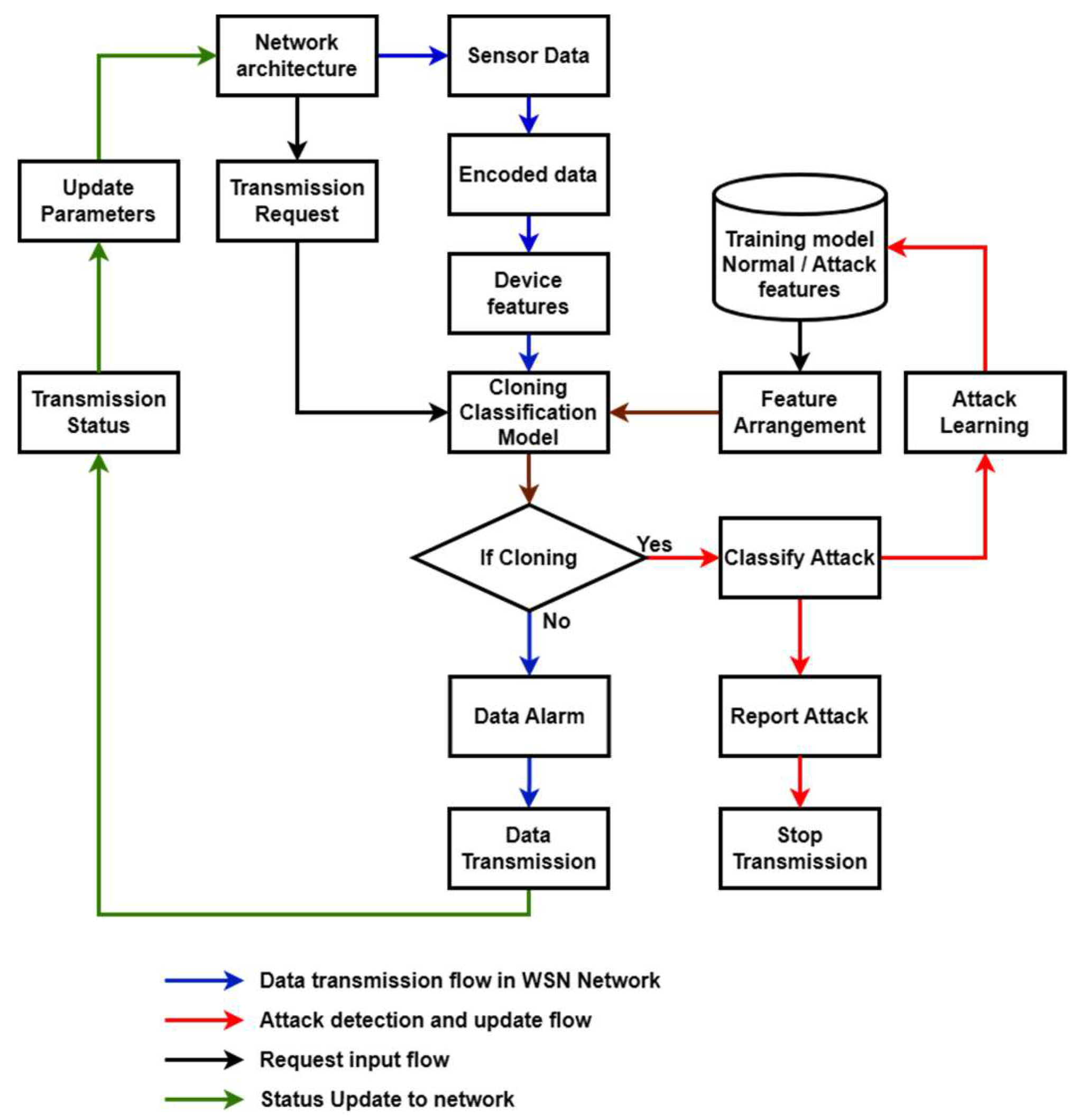

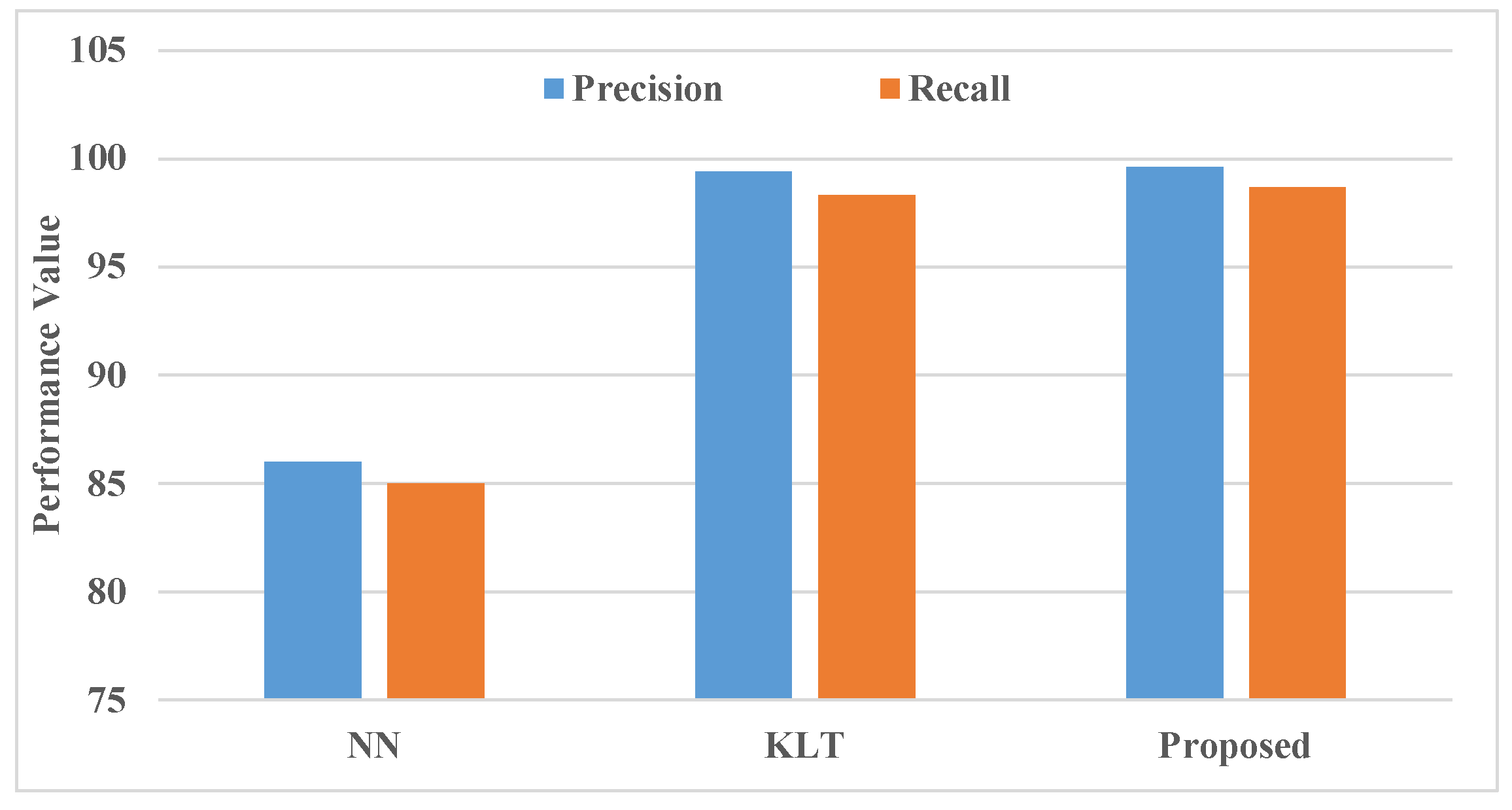

The

Table 3 highlights the superior performance of the proposed Distributive Correlated Neural Network (DCNN) algorithm in terms of precision and recall for clone detection in hybrid wireless sensor networks (WSNs). With precision at 99.6% and recall at 98.7%, the DCNN algorithm outperforms previous methods like NN and KLT, which achieve 86% and 99.4% precision and 85% and 98.3% recall, respectively.

In comparison to reference [

15], where KLT (Karhunen-Loève Transform) shows impressive results with 99.4% precision and 98.3% recall, the DCNN algorithm further enhances these metrics. The KLT-based method, which primarily focuses on dimensionality reduction and signal processing, is effective in environments with well-defined data characteristics. However, it may be limited by high computational demands and less adaptability in handling dynamic network topologies or hybrid configurations where both mobile and static nodes are present, which can be seen from the

Figure 5.

The DCNN algorithm’s marginal improvement over KLT in both precision and recall demonstrates its robustness and ability to handle complex data patterns through its distributive correlation approach. This adaptability allows DCNN to not only maintain high classification accuracy but also reduce false positives and negatives in diverse network conditions. By integrating distributive learning and adaptive classification, the proposed method provides an advanced, scalable solution that surpasses the KLT approach, especially in hybrid WSN environments where real-time accuracy and adaptability are critical.

The results

Table 4 shows the exceptional performance of the proposed Distributive Correlated Neural Network (DCNN) algorithm in clone detection for hybrid wireless sensor networks (WSNs), compared to methods such as the KLT Tracker and Neural Network (NN). The proposed DCNN algorithm achieves 99.6% precision, 98.6% recall, and an overall performance of 99.95%, outperforming both KLT Tracker and NN by significant margins.

Comparing with [

20] demonstrates the KLT Tracker’s performance, where recall is 89.65% with a performance score of 94.5%. While effective in reducing dimensionality and detecting signals, the KLT Tracker lacks adaptability to the complexities of hybrid WSNs that involve both mobile and static nodes. This limitation reduces its effectiveness in handling the varied network dynamics and leads to lower clone detection accuracy in such environments.The NN method, achieving 90% precision, 82% recall, and a performance score of 99.1%, shows better adaptability than the KLT Tracker, but it still lacks the advanced distributive correlation feature that DCNN offers. NN's accuracy drops in dynamic hybrid WSNs because it does not leverage multifaceted relationships among nodes as effectively as DCNN does.

The proposed DCNN algorithm’s superiority in all metrics—precision, recall, and overall performance—can be attributed to its unique ability to handle distributed and correlated data patterns, which enhances clone detection accuracy even in complex network topologies. By leveraging adaptive learning and distributive correlation, DCNN manages to maintain low false positive and false negative rates, demonstrating optimal reliability and efficiency, which makes it particularly suitable for hybrid WSNs where network dynamics are unpredictable and challenging.

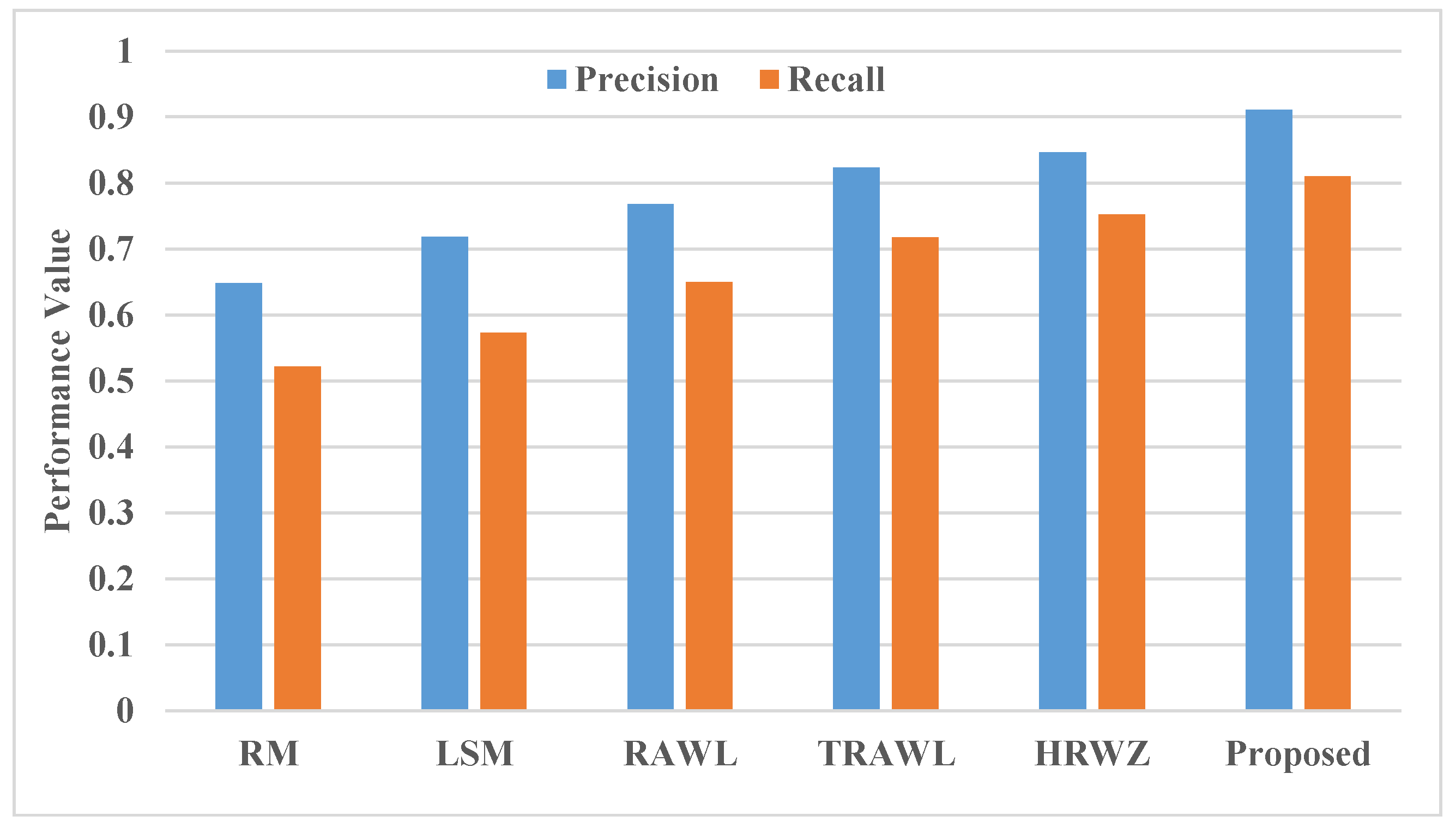

The

Table 5 highlights the superior clone detection capabilities of the proposed Distributive Correlated Neural Network (DCNN) algorithm, particularly when compared with methods like the KLT Tracker and Neural Network (NN). The DCNN algorithm achieves 98% precision, 94% recall, and a tracking performance of 93.4%, outperforming both KLT Tracker and NN in recall and tracking performance which can be seen from the

Figure 6.

In [

25], the KLT Tracker achieves 91% precision, 78.7% recall, and a tracking performance of 79. Although KLT is effective in feature tracking and dimensionality reduction, its limited recall and tracking performance show its constraints in dynamically adapting to hybrid WSN environments that include both mobile and static nodes. The KLT Tracker's performance is reduced due to its difficulty in adapting to network topology changes and complex data patterns, which are common in hybrid WSNs.The NN method performs better, reaching 98% precision, 91% recall, and 91.2% tracking performance. While this demonstrates strong detection capabilities, NN lacks the distributive correlation learning approach that DCNN provides. As a result, NN’s effectiveness in clone detection within hybrid WSNs is slightly lower, as it may not capture the subtle correlations in node behavior as effectively as DCNN does.

The DCNN algorithm’s distributive approach allows it to capture and adapt to diverse patterns and correlations within the network, achieving higher recall and tracking performance. This adaptability results in a more accurate detection of clone attacks, even in complex, hybrid WSNs where network conditions are variable and dynamic. Thus, the DCNN algorithm’s higher precision, recall, and tracking performance demonstrate its suitability for hybrid WSNs, providing more reliable and resilient clone detection compared to both the KLT Tracker and NN.

Figure 7.

Comparison of KLTT & NN with performance values for A,P,R for the tracking performances.

Figure 7.

Comparison of KLTT & NN with performance values for A,P,R for the tracking performances.