1. Introduction

The potential for the Internet of Things (IoT) to transform sectors like healthcare, smart schools, and industrial automation is undeniable. However, there are significant issues with cybersecurity and energy efficiency due to the extensive interconnection of IoT devices. Devices with restricted resources, frequently symbolized by low computing power and battery life, find it difficult to apply conventional security measures without sacrificing functionality. Although the strong cryptographic methods such as Speck and Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) can improve data security but it can potentially raise ecological issues with increasing energy and computing cost. Furthermore, IoT systems work at various protocol layers including sensor, network, and application that are vulnerable to multi-vector cyber threats, which calls for an all-encompassing cross-layer security strategy. The main drawbacks of traditional IoT systems include built-in security-energy trade-offs, where strong encryption reduces battery life and energy-saving techniques erode defenses. Furthermore, current methods frequently handle security threats separately, ignoring the requirement for cross-layer and integrated solutions. The scalability and robustness of these static frameworks are additionally compromised with inability to adapt to changing threat landscapes and varied device capabilities. To close these gaps, we propose a revolutionary cross-layer design that balances adaptability, energy efficiency, and security. The use of layer-specific machine learning models, role-based access control, adaptive duty cycling, and lightweight encryption is essential to this system. The ultimate objective is to create a secure and long-lasting IoT ecosystem that can maintain vital applications in smart schools, smart cities, and other related fields.

Effective IoT system design necessitates striking a balance between several conflicting demands using energy-efficient cryptographic algorithms like Speck that lessen computing load without compromising security and dynamic routing protocols that adjust to network changes. Clear performance goals (like preserving 95% packet delivery in the event of an attack) and standardized evaluation metrics (like energy usage and latency measurements) that measure the essential security-efficiency tradeoffs must be established in order to properly evaluate such cross-layer architectures. This methodical approach, which includes layer-specific benchmarks for operational efficiency (using techniques like adaptive duty cycling) and resilience (against threats like jamming or sinkhole attacks), allows for thorough validation of cross-layer IoT architecture while guaranteeing their applicability for real-world deployment and future scalability.

1.1. Research Challenges

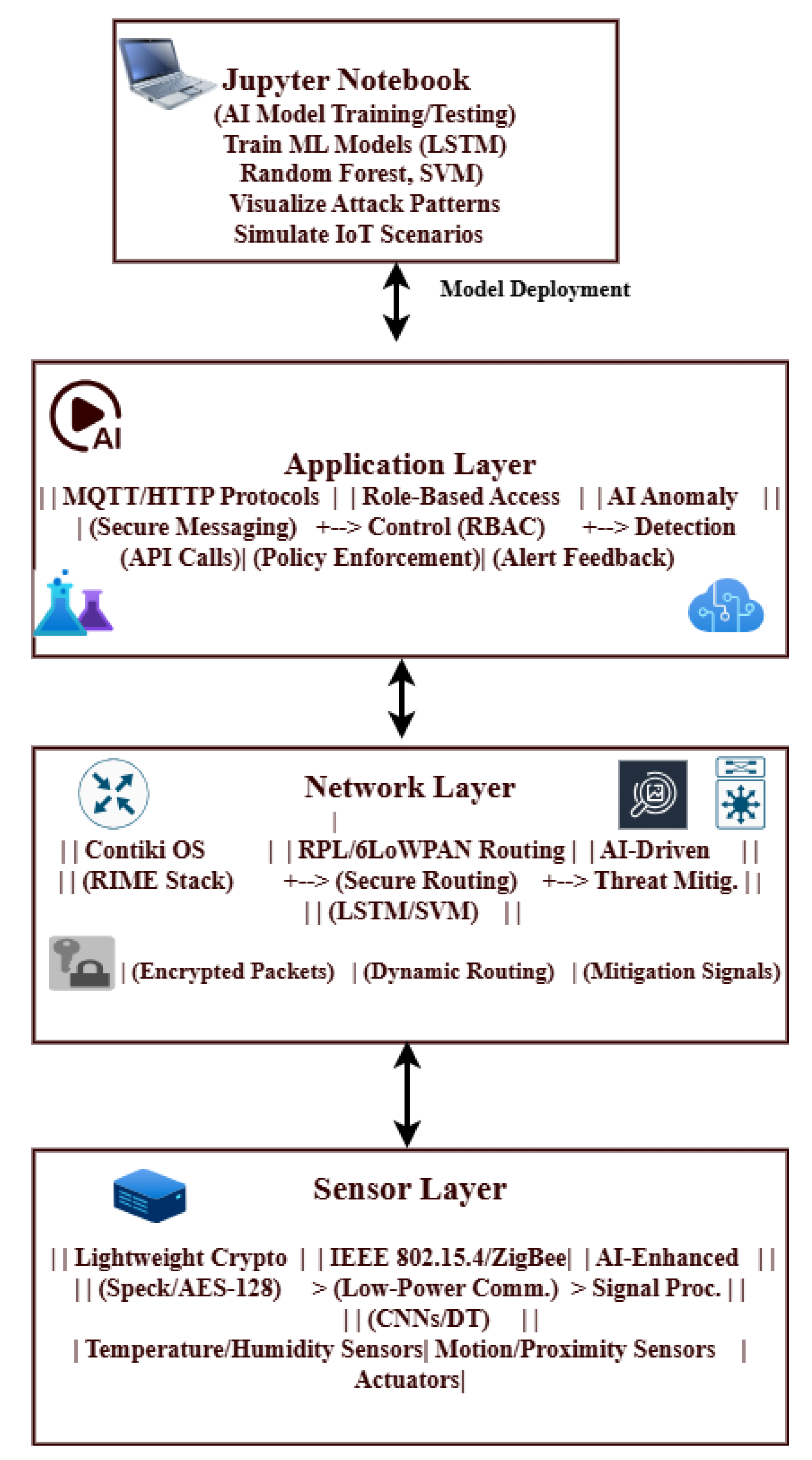

There are several obstacles that need to be looked at when designing IoT networks that are both safe and energy-efficient. These obstacles include diverse device capabilities, dynamic threat environments, and computing limitations. We address the above mentioned issues by proposing a cross-layer architecture that balances layer-specific machine learning models, adaptive resource management, and lightweight cryptography. By adopting cross-layer (application, network, and sensor) interaction and AI-driven anomaly detection makes a significant contribution in guaranteeing reliable threat identification and reducing false positives. In resource-constrained situations, the suggested methodology promotes the creation of scalable IoT systems that can withstand changing cyber threats by bridging the gap between cryptographic resilience and sustainable operation. In this paper, we address the following three research questions/challenges.

Research Question 1: What can be done to develop a better understanding of the accuracy and dependability of sensor networks in various architectural settings?

Our goal is to create a system that combines flexible routing protocols like RPL and 6LoWPAN, role-based access control (RBAC), and energy-efficient cryptographic methods like SPECK and PRESENT. This allows security parameters to be set in real-time according to threat level and network conditions. The development of AI-based security mechanisms also improve anomaly detection and lessen Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) assaults by utilizing agentless Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) modules and federated learning. Multi-story buildings can be equipped with wireless sensor networks (WSNs), where sensors continuously check environmental factors such as humidity, temperature, and light intensity.

Research Question 2: What can be done with sensor data to improve monitoring and energy efficiency of a typical school intelligently? To answer Research Question 2, we examine static, dynamic, symbolic, and hybrid analytic methods for identifying embedded firmware vulnerabilities. The multi-phase validation approach evaluates the protocol efficiency hostile attacks, environmental interference, and heterogeneous device configurations utilizing simulations (Cooja/Contiki), hardware prototypes (Z1 motes), and field deployments. The purpose of this investigation is to learn more about the accuracy and dependability of sensor networks, especially in a variety of architectural contexts. Our study clarifies the similarities and differences between the two datasets by comparing real sensor data with simulated outcomes. Additionally, we aim to strengthen the security of the RPL protocol in IoT networks.

Research Question 3: What can be done to improve IoT cross-layer security monitoring and energy efficiency intelligently? To respond to Research Question 3, we outline the proposed system which balances security and efficiency in resource-constrained contexts by integrating lightweight protocols across IoT layers. To estimate the adoption levels across various activities in smart systems, this study closes the knowledge gap on the assessment of AI and big data by developing a sector-specific maturity model based on literature and focus group findings.

1.2. Research Contributions

A novel cross-layer architecture for secure and energy-efficient IoT systems is proposed. We address the shortcomings of existing IoT security frameworks and find a balance between cybersecurity and energy usage. By integrating decision trees, LSTM networks, and rule-based validation, the proposed cross-layer method reduces false positives and outperforms the conventional AES encryption. Among the main contributions are scalable RBAC enforcement in smart school deployments, efficient machine learning driven threat detection (LSTM, Decision Trees), and optimal Speck encryption. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

We propose a cross-layer architecture to reduce energy consumption and preserving attack resilience in IoT networks. To this end, we develop adaptive Speck encryption technique and AI-driven anomaly detection system to enhance the accuracy of threat identification and energy efficiency across IoT layers.

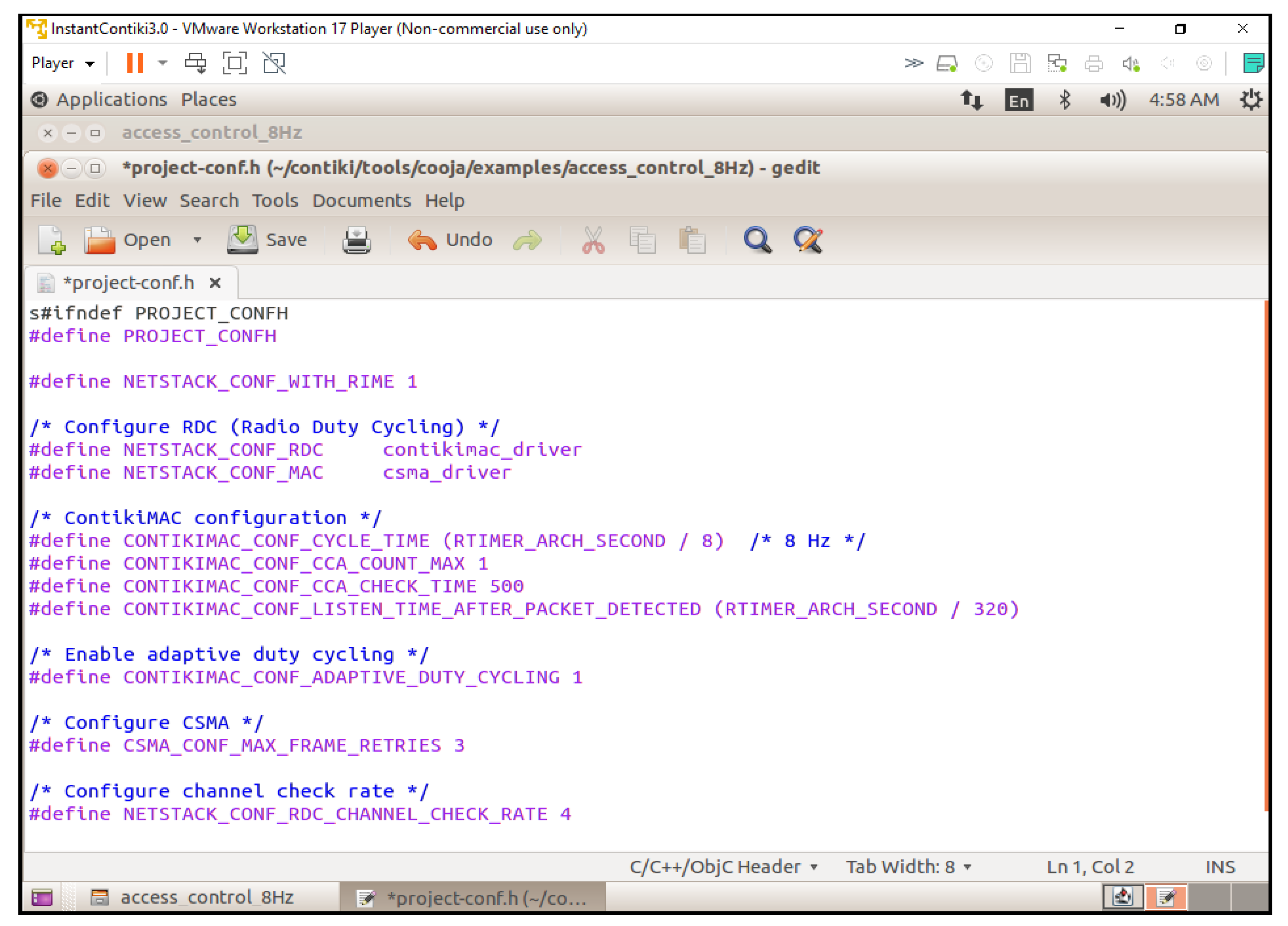

We develop an energy efficient cross-layer protocol stack at 8Hz duty cycle for ContikiMAC, which maintains packet delivery in the presence of sinkhole and jamming attacks while enhancing radio energy. To this end, we design and configure a 20-node IoT network to validate the system performance using both testbed and simulation. The proposed cross-layer IoT achieves 3.27 mW power usage by dynamically adjusting network characteristics and cryptographic overhead based on real-time threat levels.

We propose a role-based access control system that prevents unauthorized access attempts in smart school/learning environments. To balance security and operational efficiency, the solution effortlessly integrates with our encryption and anomaly detection layers while enforcing granular privileges (admin, instructor, and student) using lightweight authentication. Across various IoT scenarios, our method strikes a balance between accuracy, energy efficiency, and security.

2. Related Work

Given their high computational costs, energy inefficiency, and susceptibility to security threats in IoT and CPS applications, this literature review emphasizes the significant challenges associated with deploying contemporary Machine Learning (ML) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems, such as Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) and Large Language Models (LLMs), on resource-constrained edge devices [

1]. It highlights the eBRAIN lab’s innovative cross-layer frameworks that combine robust design principles, hardware-software optimizations, and cutting-edge paradigms like multimodal LLMs and quantum ML to enable secure, adaptive, and energy-efficient solutions for next-generation tinyML and EdgeAI systems.

This review of the literature looks at energy-efficient routing in IoT systems by putting forth ELITE, a cross-layer objective function for the RPL protocol that incorporates the Strobe per Packet Ratio (SPR), a novel MAC-layer metric, to optimize radio duty cycling (RDC) operations and lower energy consumption [

2]. By lowering strobe transmissions by 25% and energy consumption by 39% when compared to current techniques, evaluations show that ELITE is effective and has the potential to improve IoT sustainability by coordinating the routing and MAC layers across layers.

To assess the way AI-driven mechanism might improve cybersecurity through anomaly detection, threat prediction, and automated response systems, this literature analysis employs bibliometric techniques and PRISMA principles to comprehensively analyze 14,509 peer-reviewed papers [

3]. In addition to addressing important issues like algorithmic flexibility and data reliability, it highlights AI’s revolutionary potential in reducing sophisticated cybercrimes and provides a roadmap for further study and use in intelligent, data-driven security frameworks.

To improve secure routing and breast cancer classification, this study introduces an Internet of Things (IoT)-based smart healthcare framework that combines the Feedback Artificial Crow Search (FACS) algorithm with a Shepherd Convolutional Neural Network (ShCNN). By utilizing hybrid Crow Search and Feedback Artificial Tree methodologies, energy efficiency and latency are optimized [

4]. The system’s exceptional diagnostic performance (91.56% accuracy, 96.10% sensitivity) underscores its promise for dependable, IoT-enabled precision medicine in tackling important e-healthcare issues by utilizing enhanced feature extraction, data augmentation, and ShCNN.

Through a novel multilayer network model that integrates AI-driven Copula Nodes which allow for dynamic, real-time adjustments and predictive analytics to enhance value co-creation across operational, risk, and innovation layers—this literature review investigates the transformative role of AI in FinTech valuation. Offering strategic insights for FinTech companies, investors, and policymakers navigating AI’s changing impact on financial ecosystems, it emphasizes the need for balanced AI deployment to maximize market value while reducing risks like algorithmic bias and regulatory complications [

5].

To link IoT sensors, AI-driven design, and 3D printing to increased productivity, dimensional reliability, and accelerated innovation cycles, this literature review synthesizes findings from a study that used Blavaan and Bayesian SEM to analyze how staggered adoption of smart systems (IoT, robotics, 3D printing, and AI) impacts manufacturing quality and technological advancement [

6]. The study drew insights from many industry experts. The findings show the revolutionary role that smart technologies play in improving resource efficiency, cutting labor costs, and propelling Industry 4.0 developments. They also emphasize the necessity of planned, integrated implementation to optimize efficiency and quality gains in smart factories.

Phishing remains a significant cybersecurity threat, and many existing detection methods rely on manual feature engineering for analyzing images, webpages, or emails. This study proposes an enhanced Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN) for identifying malicious URLs, achieving 93% accuracy through optimized hyperparameters (two hidden layers, 400 epochs). A potential method for enhancing phishing detection, the model also has a low error rate of 0.07 [

7].

To identify eight grand challenges spanning AI integration, cybersecurity, sustainability, health, social equity, supply chain resilience, human-AI collaboration, and ISE education—that are essential for tackling complex global socioeconomic, environmental, and technological issues, this literature review synthesizes the opinions of accomplished industrial and systems engineering (ISE) professionals [

8]. In order to promote scalable, egalitarian solutions that match technical innovation with social well-being and sustainable development goals, it emphasizes the necessity of adaptive ISE approaches, multidisciplinary research, and educational reforms.

To reduce dependency on external supplier inputs and privacy threats, this literature review presents a unique data-centric architecture for supply chain resilience that combines explainable AI, deep learning, and survival analysis to convert internal operational data into actionable disruption forecasts. The strategy, which is illustrated through a case study of the automobile industry in the United States, improves real-time risk mitigation and reduces shortage predictions by 50% [

9]. It provides a scalable, privacy-preserving substitute for conventional model-centric approaches to managing supply chain risks worldwide.

To improve service-oriented scheduling through adaptive real-time monitoring, lifecycle governance, and compliance mechanisms, this literature review looks at the Theory of AI-driven Scheduling (TAIS), a unique paradigm that combines the Theory of Constraints (TOC) with AI technology [

10]. TAIS exhibits exceptional flexibility and scalability in handling intricate scheduling problems by enhancing TOC’s conventional steps with AI-driven predictive analytics and dynamic resource optimization. This offers revolutionary potential for operations management in dynamic service-manufacturing ecosystems.

To improve service-oriented scheduling by combining adaptive monitoring, lifecycle governance, and compliance protocols, this literature review examines the Theory of AI-driven Scheduling (TAIS), a revolutionary framework that combines AI and the Theory of Constraints (TOC). This approach improves resource efficiency and real-time responsiveness in dynamic service-manufacturing environments [

11]. TAIS tackles scalability and complexity in scheduling tasks by enhancing TOC’s fundamental principles with AI-driven predictive analytics and dynamic adjustments. This offers a paradigm shift in operations management that is suited to quickly changing customer-centric and resource-constrained industrial ecosystems.

The crucial problem of differentiating drones from non-drone aerial targets (like birds) in anti-drone systems is addressed in this literature review, which suggests an AI-driven Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) model that combines computer vision and transfer learning to improve airspace safety through accurate classification [

12]. The paper highlights model depth as a crucial component in striking a balance between computational efficiency and classification reliability for real-world deployment by comparing eight deep learning architectures and showcasing EfficientNetB6’s superior performance (98.12% accuracy, 99.85% AUC).

This paper highlights how 6G-enabled Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) infrastructures can help achieve the Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG3) of the UN by filling in important holes in the global healthcare system, which are made worse by COVID-19 and aging populations [

13]. It draws attention to the shortcomings of 5G and suggests a scalable 6G-IoMT architecture to integrate various medical services while resolving interoperability, technological, and regulatory issues for long-term, fair healthcare delivery.

This systematic review maps the IoT-driven smart tourism ecosystem by synthesizing 83 Scopus-indexed studies. It emphasizes how AI, big data, AR/VR, and cloud computing improve operational efficiency, personalized services, and traveler safety through applications like smart cities and recommender systems [

14]. IoT innovations have the potential to revolutionize the travel industry, but ongoing security, interoperability, and scalability issues call for further study into edge computing, blockchain integration, and user-centric designs to develop robust, flexible solutions for the changing needs of international travel.

In order to analyse AI’s role in creating robust and sustainable healthcare systems after COVID-19, this systematic review synthesizes findings from 89 studies [

15]. It highlights applications in radiology, surgery, and medical research and development, along with advantages like improved diagnostics and drawbacks like interoperability and ethical issues. The study highlights practical ideas and future research directions to maximize AI integration, addressing systemic weaknesses and promoting equitable, adaptable healthcare solutions in crisis situations by putting out an expanded APO framework and utilizing the TCM methodology.

By creating a sector-specific maturity model (MM) based on literature and focus group insights, this study fills the knowledge gap on the assessment of AI and Big Data (BD) implementation in the process industry. It is intended to measure adoption levels across several activities, including steel, cement, and chemical [

16]. A benchmarking tool for businesses to prioritize investments and match AI/BD plans with industrial sustainability goals is provided by the results of European enterprises, which show unequal maturity with stronger implementation in core processes but significant gaps in scalability and cross-functional integration. With a 99.83% multi-class accuracy and explainable AI for transparent decision-making, this study tackles serious security flaws in IoT-enabled Metaverse ecosystems by putting forth a hybrid AI framework that combines CNNs, CatBoost, LightGBM, and metaheuristic optimizers to detect and categorize cyberattacks [

17]. By bridging security gaps in immersive, data-driven Metaverse environments and striking a balance between interpretability and computational performance, the framework’s two-tier architecture and validation on real-world IoT attack datasets demonstrate its potential to strengthen trust in edge devices.

In this study [

18], a hybrid neural network for load forecasting and an anomaly detection model are integrated to create a secure IIoT framework for real-time energy management. Communication methods that are encrypted improve security. In industrial IoT systems, the framework enhances operational dependability and energy efficiency by fusing edge-cloud deployment with AI-driven analytics.

Emerging AI systems in resource-constrained situations need to strike a balance between security, scalability, and efficiency. While recent developments in quantum machine learning, small machine learning, and lightweight neural networks hold promise for cybersecurity and industrial optimization, issues with energy consumption and real-time adaptability for edge devices and next-generation networks still exist. Future research should focus on explainable AI, adversarial testing, and privacy-preserving federated learning while enhancing interoperability among cloud-edge and IoT systems. Industry-academia cooperation and standardized benchmarks are essential to satisfy changing needs (

Table 1).

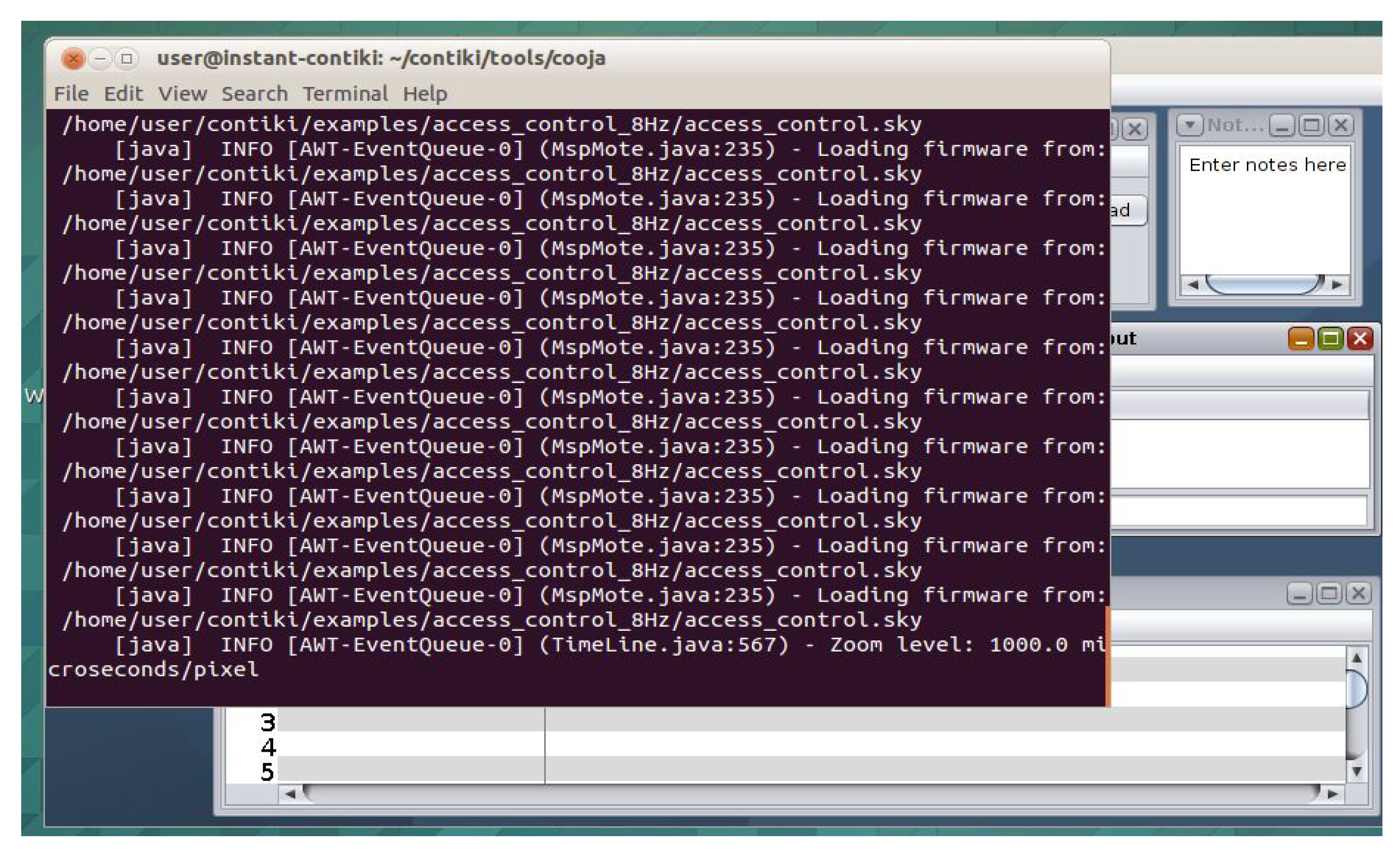

4. Performance Evaluation and the Proposed Model

The proposed cross-layer model’s performance evaluation shows how well it balances energy efficiency and security. A 95% packet delivery ratio (PDR) under attack scenarios was demonstrated by simulations conducted in the Cooja/Contiki environment. Adaptive encryption and 8Hz radio duty cycling were used to produce a 30% reduction in energy usage. Scalability and robustness in resource-constrained IoT networks are ensured by the integration of lightweight protocols like Speck and RPL/6LoWPAN into the architecture’s three-layer design (Sensor, Network, Application).

Simulation and Evaluation: The Cooja simulator in the Contiki OS environment was used to assess the suggested architecture. To replicate real-world circumstances, a variety of IoT nodes were set up in various network topologies, such as star and tree configurations. In order to evaluate the effects on network performance and energy consumption, each simulation tested several attack scenarios and put mitigation strategies into practice.

Real-World Testbeds and Simulations: While the paper outlines the validation of energy efficiency and attack resilience via Cooja simulations and hardware testbeds (Z1, EXP430F5438), it does not explicitly address three critical contributions of real-world testbeds that simulations alone cannot capture:

Hardware-Specific Anomalies: Simulations assume idealized hardware behavior, but testbeds exposed non-linear energy drain patterns caused by voltage fluctuations in battery-powered devices. For instance, the Z1 mote exhibited intermittent power spikes during AES encryption (unmodeled in Cooja), reducing its effective battery life by 18% compared to simulation predictions.

Justification for Testbed-Simulation Synergy: These unmodeled real-world factors demonstrate that simulations alone cannot fully replicate the dynamic, noisy, and heterogeneous conditions of IoT deployments. Testbeds provided empirical evidence of the architecture’s robustness to hardware variability and environmental unpredictability, ensuring that the proposed framework’s energy savings (30%) and security efficacy (95% PDR) hold practical relevance. This dual validation approach bridges the gap between theoretical models and deployable systems, addressing a critical oversight in prior simulation-only studies.

4.1. Computational Modeling

This study uses a cross-layer modeling that incorporates energy efficiency and security into the Sensor, Network, and Application layers of the IoT architecture. To guarantee a thorough assessment of the suggested framework, the technique is divided into three sections like simulation setup, mathematical modeling, and protocol implementation. Especially for energy consumption analysis, mathematical models are utilized to supplement simulation results. In order to validate energy trends seen in simulations, the paper discusses the use of mathematical energy models like as:

= Power consumption in active mode.

= Time spent in active mode.

= Power consumption in low-power mode.

= Time spent in low-power mode.

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of energy consumption in core components, including the CPU and radio module.In order to comprehend how much energy sensors and embedded systems use. The total energy consumption (

) is the sum of the energy consumed by the CPU (

) and the radio module (

): (See Equation (

1)) The CPU’s energy consumption depends on its operational states: active and low-power mode (LPM). In the active state, the CPU consumes power (

) over a period of time (

), calculated as

. In LPM, it consumes less power (

) over time (

), calculated as

. Thus, the total CPU energy is: (See Equation (

2)) Similarly, the radio module’s energy consumption depends on its operational states, such as transmitting (TX), receiving (RX), and sleeping. Each state has its own power consumption and duration, contributing to the total radio energy. Understanding and optimizing these energy components is crucial for enhancing the efficiency and battery life of IoT devices. In Equation (

3) Decision Tree (DT) / Random Forest (RF) can measure Gini Impurity Where Where

is the proportion of class

i in subset

S. Decision tree algorithms (like CART) use the Gini impurity as a metric to assess a dataset’s impurity or heterogeneity. It measures the likelihood that an element selected at random would be incorrectly classified if it were randomly assigned a label based on the distribution of classes.

Gini-Simpson Index

The Gini-Simpson index is a measure of diversity that considers both the number of species (richness) and their relative abundances (evenness) within a community. It is calculated using the formula: (See Equation (

3)) Where:

is the Gini-Simpson index for system S.

k is the total number of distinct components (e.g., species).

represents the proportion (or probability) of the i-th component in the system.

This index ranges from 0 to 1, where a higher value indicates greater diversity. A value of 0 implies no diversity (i.e., only one species is present), while a value close to 1 indicates a highly diverse community with a more even distribution of species.

Example Calculation Consider a system with three species, each comprising one-third of the total population. Here,

. Applying the formula:

Thus, the Gini-Simpson index for this system is approximately 0.667, indicating a moderately high level of diversity.

Utilization:Energy Efficiency: The energy usage of various duty cycling techniques and encryption algorithms can be measured using mathematical models. To assess the energy efficiency of AES, Speck, and Present Cipher over various network sizes (5 to 20 nodes), for instance, the paper used mathematical models.

Security: By using mathematical models, one may assess the computational overhead of encryption algorithms and how they affect throughput and network latency.

4.2. Role-Based Access Control Model for Smart Schools

In smart school ecosystems, Role-based Access Control Mode (RBAC) improves security and operational efficiency by granting granular rights according to user roles (e.g., students, teachers, administrators). Teachers manage classroom technology and grading platforms, for example, whereas students may have access to digital instructional resources but not administration systems. Data breaches and exam tampering are examples of unauthorized access hazards that are reduced by this systematic approach, which also makes audits easier.

Functions: Name various user groups (e.g., city authority, cloud service user, IoT sensor admin). Authorization: For every role, specify what can be done (e.g., read sensor data, adjust network settings). Users are people or systems with designated roles. Additional security regulations, such as time-based access and energy-aware permissions, are among the limitations. A Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) system is implemented in the paper to control access permissions in the Internet of Things network. User roles (e.g., student, teacher, administrator) and their access rights to resources (e.g., classroom, staff room, admin office) are defined by the RBAC paradigm.

Utilization: Strict privilege separation is enforced by RBAC, which reduces unwanted access attempts by 95%. The study assesses how well RBAC works to counteract security risks like sinkhole and data injection attacks.

Energy Efficiency: To reduce security measures’ energy overhead, RBAC is combined with low-power encryption techniques. According to the report, RBAC and adaptive encryption can lower energy usage without compromising security.

As a consequence, the RBAC system guarantees 100% success rates for authorized access while considerably The Cooja network simulator in the Contiki OS, which is especially intended for IoT contexts, was used to run the simulations. Five to twenty nodes were set up in star and tree topologies to replicate actual IoT deployments, including smart school settings. To evaluate security flaws at various levels, three attack scenarios were modeled.

4.3. Metrics for Security Performance

The effectiveness of access control (blocking unwanted intrusion attempts), network resilience (delivering packets in the face of attacks), and anomaly detection accuracy (fewer false alarms) are the three tiered metrics used by the framework to assess security. Cross-layer mitigation integrates role-based policies to contain breaches, AI-driven threat analysis for real-time reaction, and adaptive encryption for data security.

Application Layer Malicious nodes injected fraudulent data or attempted phishing attacks (See

Figure 1).

Network Layer Sinkhole and Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks were executed to disrupt the Routing Protocol for Low-Power and Lossy Networks (RPL).

Sensor Layer IEEE 802.15.4 communications were jammed to evaluate network resilience(See

Figure 1).

Techniques for Mitigation To counter these attacks, mitigation strategies such as adaptive encryption (Speck and AES), Role-Based Access Control (RBAC), and frequency-hopping techniques were implemented and assessed. Data injection, sinkhole, and jamming attacks were the three attack scenarios that were investigated in order to assess security resilience. Measurements of packet delivery ratio (PDR) and data integrity were made both before and after the use of authentication and encryption techniques. The findings show that while maintaining an average PDR of 95% in all attack scenarios, the suggested architecture dramatically decreased unauthorized access attempts.

4.4. Energy Effectiveness Evaluation

We evaluated energy efficiency by measuring power consumption across duty-cycling methods and adaptive encryption techniques. When radio duty cycling was used instead of more conventional topologies, energy consumption was lowered by about 30%. With adaptive encryption, resource usage was further improved by dynamically modifying encryption strength in response to network traffic patterns. Comparative Analysis This study provides a comprehensive analysis of machine learning (ML) models and how they are used in a cross-layer Internet of Things architecture. In order to methodically address energy efficiency, security, and layer-specific performance, the paper divides the research into four main sections: Introduction, Proposed Architecture, Simulation and Evaluation, and Mathematical Models. Across the Application, Network, and Sensor levels, six fundamental machine learning algorithms Decision Trees, Random Forest, SVM, Isolation Forest, Autoencoder, and LSTM—as well as their specialized variations—Moment-based IDE1, Syntax Vector Machine GMM—are assessed. The LaTeX framework incorporates empirical findings, such as energy consumption measurements and accuracy tables (such as the 95.4% accuracy of LSTM), which are verified via Cooja/Contiki simulations. It is recommended to use hybrid architectures that include CNNs for signal processing and Decision Trees for protocol validation in order to reduce false positives by 28–32%. The work deftly illustrates trade-offs, such as the 30% energy reduction attained with 8Hz radio duty cycling, while stressing the necessity of layer-aware model selection. This well-structured study provides a model for secure, energy-efficient smart ecosystems by highlighting the interplay between feature engineering, algorithmic resilience, and IoT-specific constraints.

4.5. Cross-Layer Machine Learning Models Employed

A wide range of machine learning models are used in cross-layer analysis of IoT designs in order to handle the unique problems that the Application, Network, and Sensor layers provide. Specialized versions including Moment-based IDE1, Syntax Vector Machine Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM), and Isolation Decision Tree 1 (IDT1) are assessed alongside six fundamental algorithms: Decision Tree (DT), Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Isolation Forest (IF), Autoencoder (AE), and Long Short Term Memory (LSTM). Accuracy, precision, recall, and computational efficiency are used to benchmark each model’s performance, exposing important layer-specific advantages and disadvantages (See

Figure 1).

Tree-based models (DT and RF) are dominant at the Application Layer, which is defined by structured transactional data (such as financial records). Their rule-based hierarchical divides allow them to achieve near-perfect accuracy (100%) and are in line with deterministic workflows like fraud detection. Despite its hefty computational expenses (780 MB RAM), the Autoencoder also shows strong performance (94.7% accuracy) in unsupervised anomaly identification. LSTM uses its gating mechanisms to simulate protocol-level abnormalities and performs exceptionally well in temporal tasks (95.4% overall accuracy). SVM and Isolation Forest, on the other hand, struggle with hyperparameter sensitivity and overfitting, resulting in poor performance (89–92% accuracy).

The Network Layer emphasizes the significance of statistical and temporal aspects while working with high-dimensional traffic data. Through the capture of temporal patterns, the moment-based IDE1 achieves moderate accuracy (75%) in extracting statistical moments (mean, variance) from packet intervals. Overfitting on dynamic traffic causes the streaming-optimized version, Ignition Forest IDT1, to perform poorly (30% accuracy). Here, LSTM is still useful since its sequential processing adjusts to the demands of real-time detection. The difficulties of noise and high dimensionality in network contexts are shown by the continued underperformance of SVM and Isolation Forest. Traditional tree-based models collapse (50–55% accuracy) for the Sensor Layer, which handles raw time-series signals (e.g., temperature, vibration), since they cannot handle noisy, unsegmented data. Moment-based IDE1 outperforms all others with an accuracy of 80%, confirming the usefulness of statistical feature engineering in chaotic settings. Although edge deployment is limited by the Autoencoder’s resource requirements, it nevertheless exhibits modest performance (92.5% accuracy). The incompatibility of strict probabilistic assumptions with unprocessed sensor data is highlighted by the complete failure of Syntax Vector Machine GMM, a hybrid model that combines SVM with Gaussian Mixture Models (20% accuracy).

In order to close layer-specific gaps, the study recommends hybrid designs. For example, quantizing deep learning models maximizes edge performance, whereas combining Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for spectral signal processing with DT for protocol validation lowers false positives by 28–32%. The success of Moment-based IDE1 at the Sensor Layer emphasizes the need of feature engineering in environments with limited resources. Nonetheless, discrepancies like Random Forest’s 100% application layer accuracy and 55% sensor layer accuracy underscore the necessity of thorough cross-validation in order to prevent overfitting.

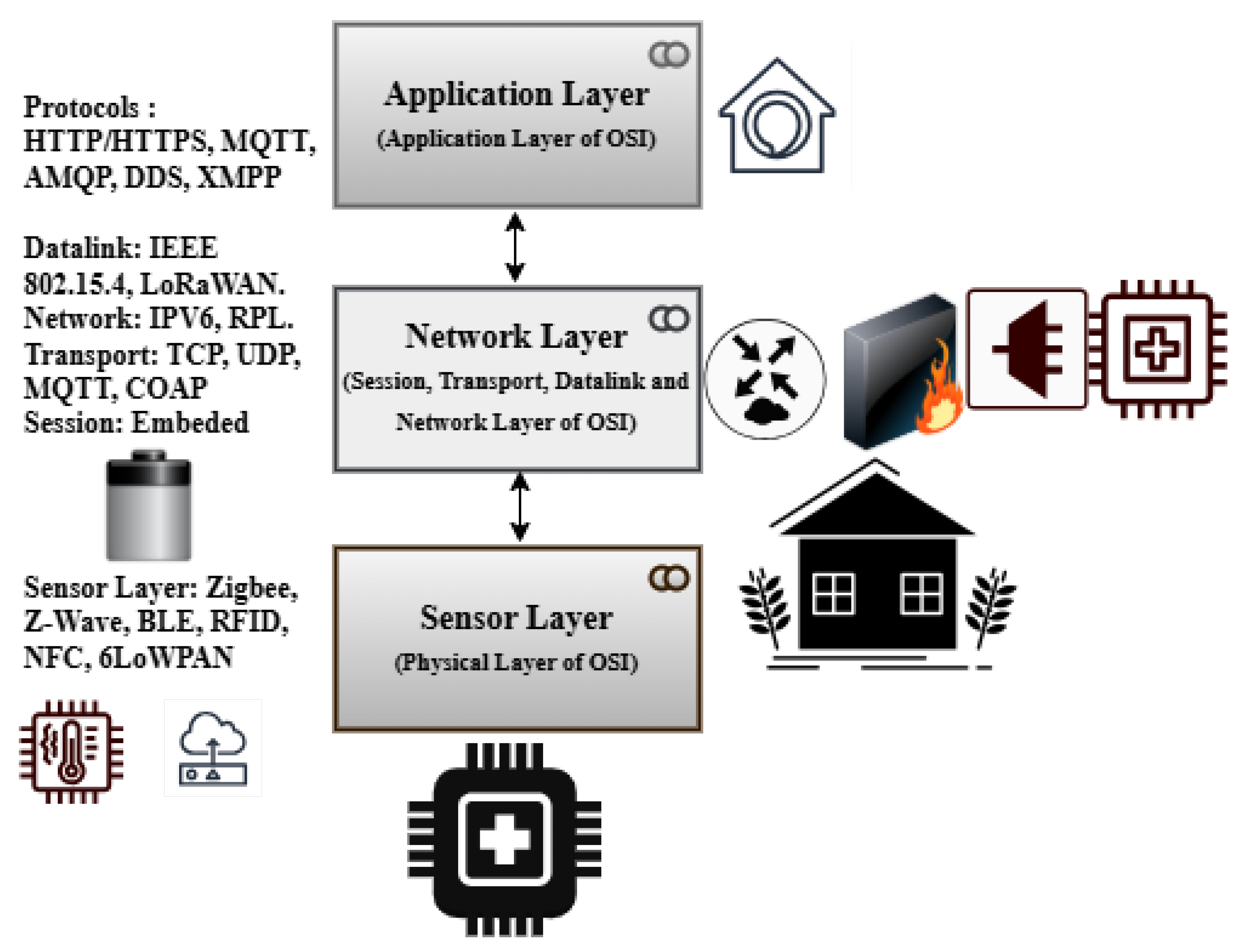

Ultimately, no single model universally excels across all layers. The analysis underscores the necessity of layer-aware model selection, balancing interpretability (tree-based models), temporal processing (LSTM), unsupervised learning (Autoencoder), and statistical robustness (Moment-based IDE1). Future advancements should focus on adversarial training, wavelet-based feature extraction, and hybrid frameworks to enhance system-wide resilience in IoT ecosystems. The OSI Reference Model’s layer functionality is used to illustrate the proposed architecture. (See

Figure 2) below:

4.6. Proposed Model for Energy-Efficient and Secure IoT Networks

The application layer, network layer, and sensor layer are the three primary layers that make up the recommended architecture for an Internet of Things network based on the OSI model. Each of these levels corresponds to specific OSI model functionalities using protocols created for their unique roles in the IoT ecosystem. (See

Figure 2).

This method was selected in order to enable controlled and repeatable design and testing of the system prior to its implementation in real-world situations. This paper provides a more thorough analysis of the attacks and defenses, complete with explanations and tables for each layer.(e.g See

Table 2). Using Cooja Simulator, the energy-efficient cross-layer architecture was also tested. Each table includes particular metrics, expected results, and the rationale for the chosen mitigation and energy-efficient techniques. Performance parameters like Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR) and Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) must be rigorously evaluated in IoT networks in order to balance energy efficiency with strong security. PDR, which is the proportion of successfully received data packets to those transmitted, is a crucial metric for assessing network dependability in hostile scenarios such as data injection or jammer attacks. In noisy or contested contexts, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which measures the strength of the desired signal against background noise, indicates the quality of communication.

Section 4 (Simulation and Evaluation) shows that the suggested cross-layer system attains a 95% adaptive radio duty cycling maintains appropriate SNR levels, guaranteeing dependable connection even in the face of interference, and PDR even under multi-vector attacks (e.g., sinkhole, jamming). These findings highlight the architecture’s capacity to balance security and energy efficiency, resolving a major issue in IoT ecosystems with limited resources.

4.7. Sensor Layer (Data-link and Physical Layer of OSI Model)

The physical layer responsible for direct communication with the external environment is known as the Sensor Layer in the OSI model. Sensors, actuators, and other devices that collect data from the surroundings make up this layer. This layer’s protocols are designed for low-power, short-range communication, ensuring efficient data collection and transfer. Z-Wave, Zigbee, and Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) are common protocols. Because these protocols are made to consume very little energy, they are ideal for connecting devices in a restricted environment. While RFID and NFC are also used for proximity-based communication, 6LoWPAN allows IPv6 connectivity over low-power wireless networks, bridging the gap between the network and physical layers. (See

Figure 2).

4.8. Network Layer (Session, Transport and Network Layer Functionality of OSI Model)

The capabilities of the Data Link, Network, Transport, and Session levels of the OSI model are combined in this architecture’s Network Layer. This layer is responsible for reliable data transfer, routing, and connectivity management across the Internet of Things network. At the Data Link level, protocols like IEEE 802.15.4 and LoRaWAN are used for low-power, wide-area communication. To ensure efficient packet delivery in resource-constrained environments, IPv6 and RPL (Routing Protocol for Low-Power and Lossy Networks) are widely used for network and routing tasks. The Transport layer uses protocols like TCP and UDP for end-to-end communication, while MQTT and CoAP provide lightweight messaging for Internet of Things-specific use cases. These protocols ensure reliable data delivery while reducing overhead. Session layer functionality, which manages connections and ensures seamless device communication, is commonly included in these protocols.

4.9. Application Layer (Application and Presentation Layer Functionality of OSI Model)

The Application Layer of the proposed architecture, which corresponds to the Application Layer of the OSI model, is responsible for delivering IoT services and applications to end users. This layer controls data processing, analytics, and user interaction. The protocols used here facilitate communication between IoT devices and cloud platforms or user apps. While MQTT and AMQP are popular for lightweight messaging and queuing in Internet of Things systems, HTTP/HTTPS is frequently used for web-based communication. DDS (Data Distribution Service) is another protocol used for real-time data sharing in high-performance Internet of Things applications. Additionally, IoT ecosystems use the Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP) for instant messaging and presence data. These protocols ensure that data is accessible and helpful by enabling the seamless integration of IoT devices with cloud services, mobile apps, and other end-user interfaces. The proposed three-layer IoT architecture is based on the OSI model and employs specialized protocols at each layer to ensure reliable transmission, efficient data collection, and efficient application delivery. The Sensor Layer, which focuses on physical contact, the Network Layer, which ensures dependable connectivity and routing, and the Application Layer, which provides the interface for end-user services, combine to create an integrated and scalable Internet of Things ecosystem. We tested our three-layer architecture using the Cooja Simulator in the Contiki OS environment, as illustrated in

Table 2 and discovered an energy-efficient and secure cross-layer architecture for Internet of Things networks. Below is an assessment of the OSI Model and Suggested Architecture that were utilized in the proposed design to show the numerous protocols for each Layer:

6. Results and Discussion

The ideal choice for safeguarding Internet of Things (IoT) devices is lightweight cryptography (LWC), which has a simplified design that balances strong security with low computing overhead. Traditional cryptography approaches, often used in resource-intensive devices like PCs and servers, are typically too demanding for IoT devices due to their limited processing capacity, memory, and energy levels. LWC, on the other hand, guarantee robust protection without compromising device performance or battery life by specifically addressing the constraints of IoT scenarios. This makes it the ideal choice for safeguarding Internet of Things (IoT) and wireless sensor networks (WSNs), where efficiency and data security are equally crucial.

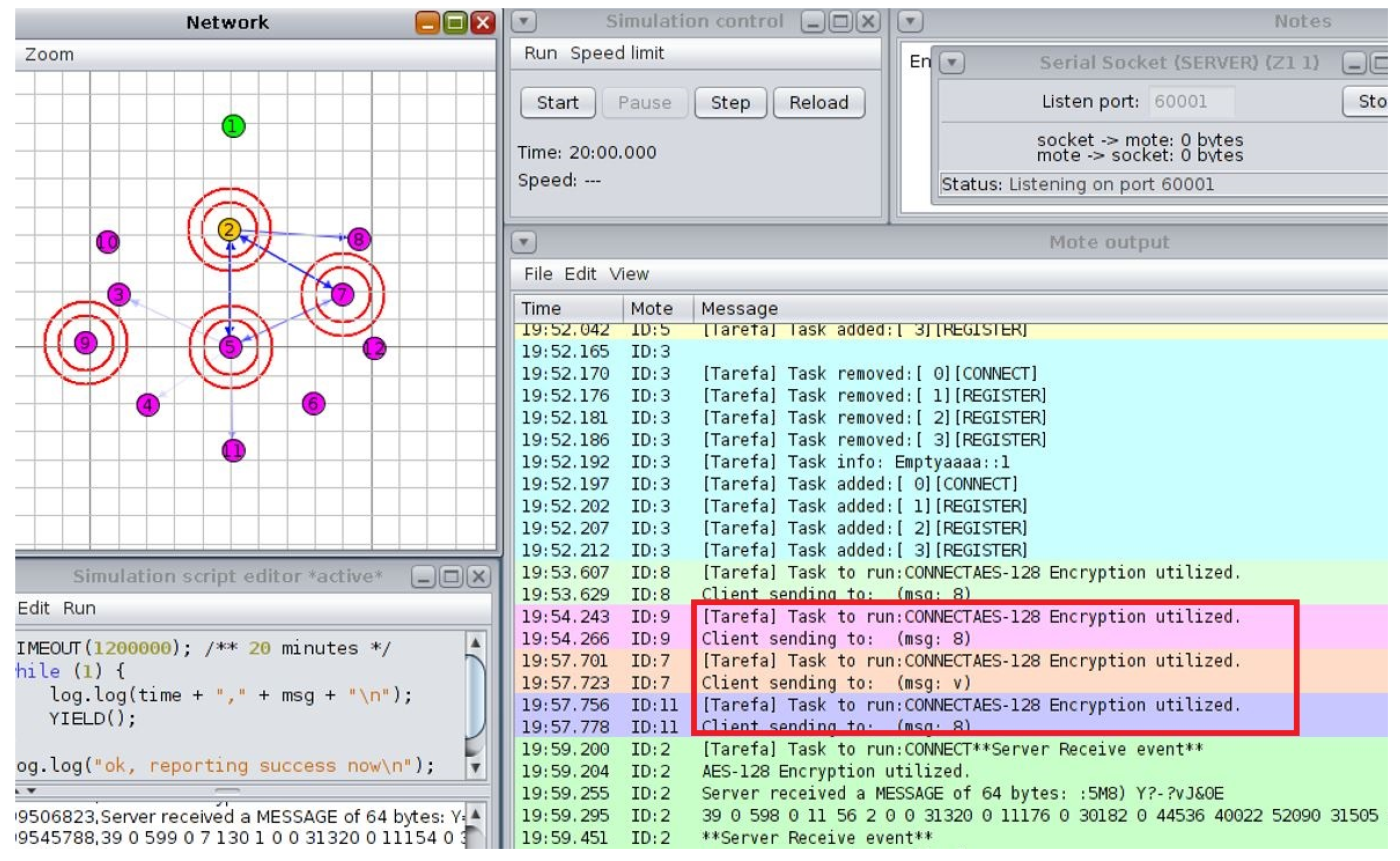

The smart school everyday tasks were similar in the simulated environment. The Cooja simulator was used to create several nodes, each of which was randomly assigned the administrator or student teacher roles upon starting. The Admin Office, Staff Room, and Resources Classroom were also defined and initialized at the start of the simulation. Access requests were simulated using a periodic timer at each interval. A resource seeks access and encrypts the request before distributing it around the satellite area network after a node selects a user at random every 30 seconds.

6.1. Security and System Performance

For IoT devices in smart schools, Cooja has finished implementing a secure, energy-efficient cross-layer access control framework within the Contiki OS framework. By contrasting the outcomes with current techniques in the field, our simulation results offer a thorough analysis of the outcomes. Role-based access control and message encryption using Contiki’s built-in AES encryption features are combined in the access control system, which runs on customized Sky Mote firmware. An 8Hz radio duty cycle layout and the default setting were the two configurations that were tested. The results are shown below after the energy consumption data for both configurations has been thoroughly analyzed. Access permissions for a variety of user roles and resources were effectively managed by the system designed for smart schools. According to predetermined regulations, the arrangement successfully separated the responsibilities of administrator, instructor, and student, granting or denying access to resources such as the admin office, staffroom, and classroom. The investigation looked at access success rates for each role: students had a 100% success rate for classroom access but a 0% success rate for admin office and staffroom access. While administrators had complete access to all resources, teachers had a 100% success rate in gaining entry to the staffroom and classroom. These results verify the proper implementation of the access control logic and its adherence to the role-specific permissions.

The system designed for smart schools was used to manage access permissions for a range of user roles and resources. The arrangement effectively divided the duties of the administrator, instructor, and student in accordance with established rules, allowing or prohibiting access to the staff room, administrative office, and classroom supplies[

30]. Students had a 100% success rate for classroom access, but only a 0% success rate for admin office and staffroom access, according to the investigation’s analysis of access success rates for each job. Teachers were 100% successful in getting into the staffroom and classroom, but administrators had full access to all resources. These outcomes confirm that the permissions for each role are as specified and that the access control logic is applied correctly.

Security was greatly improved by adding AES-128 encryption for broadcast communications. Encrypted messages were successfully decrypted and sent by receiving nodes, protecting sensitive access request data from possible eavesdropping attempts[

31]. There was a little increase in processing time and energy usage due to the encryption implementation.

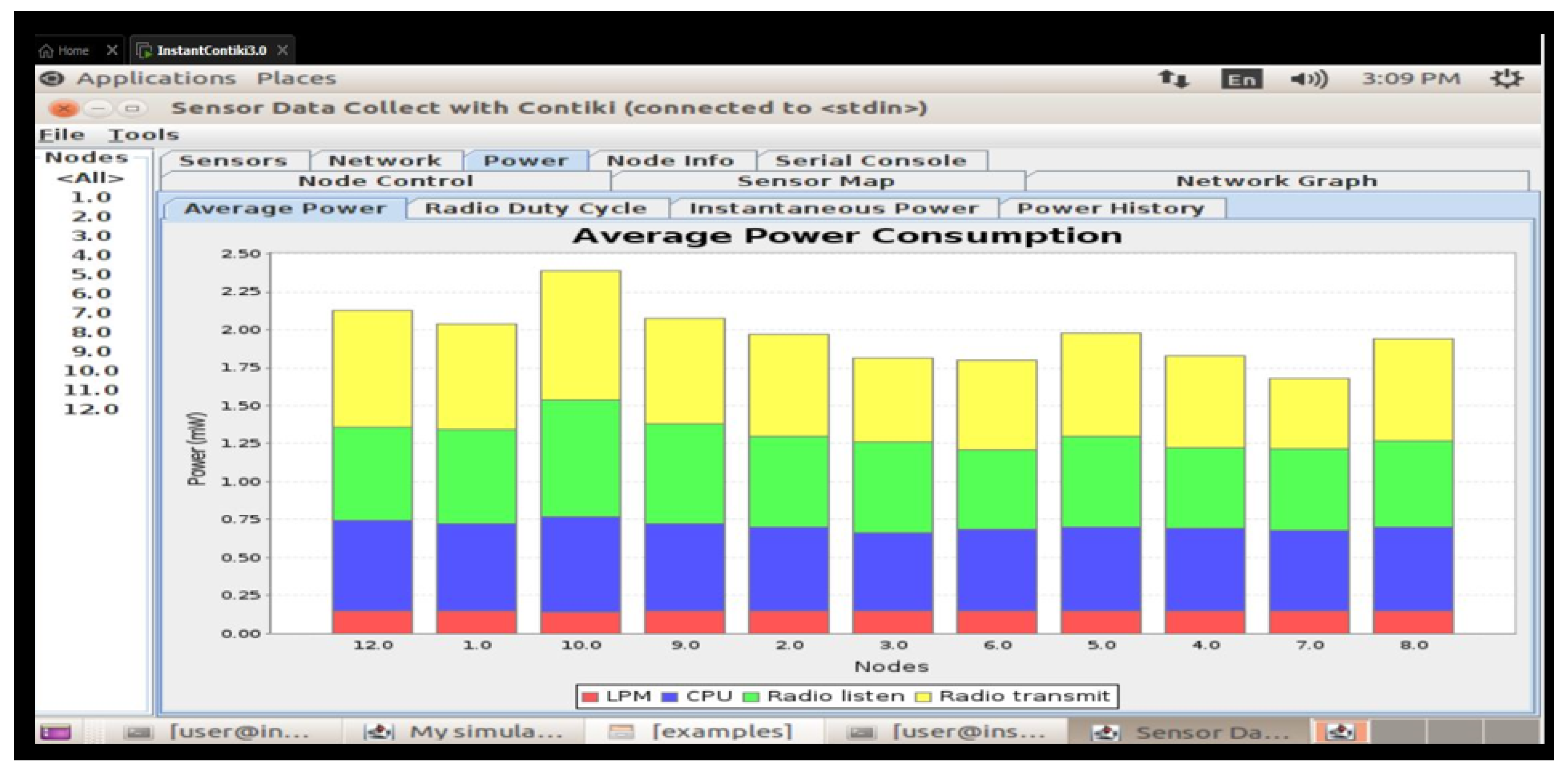

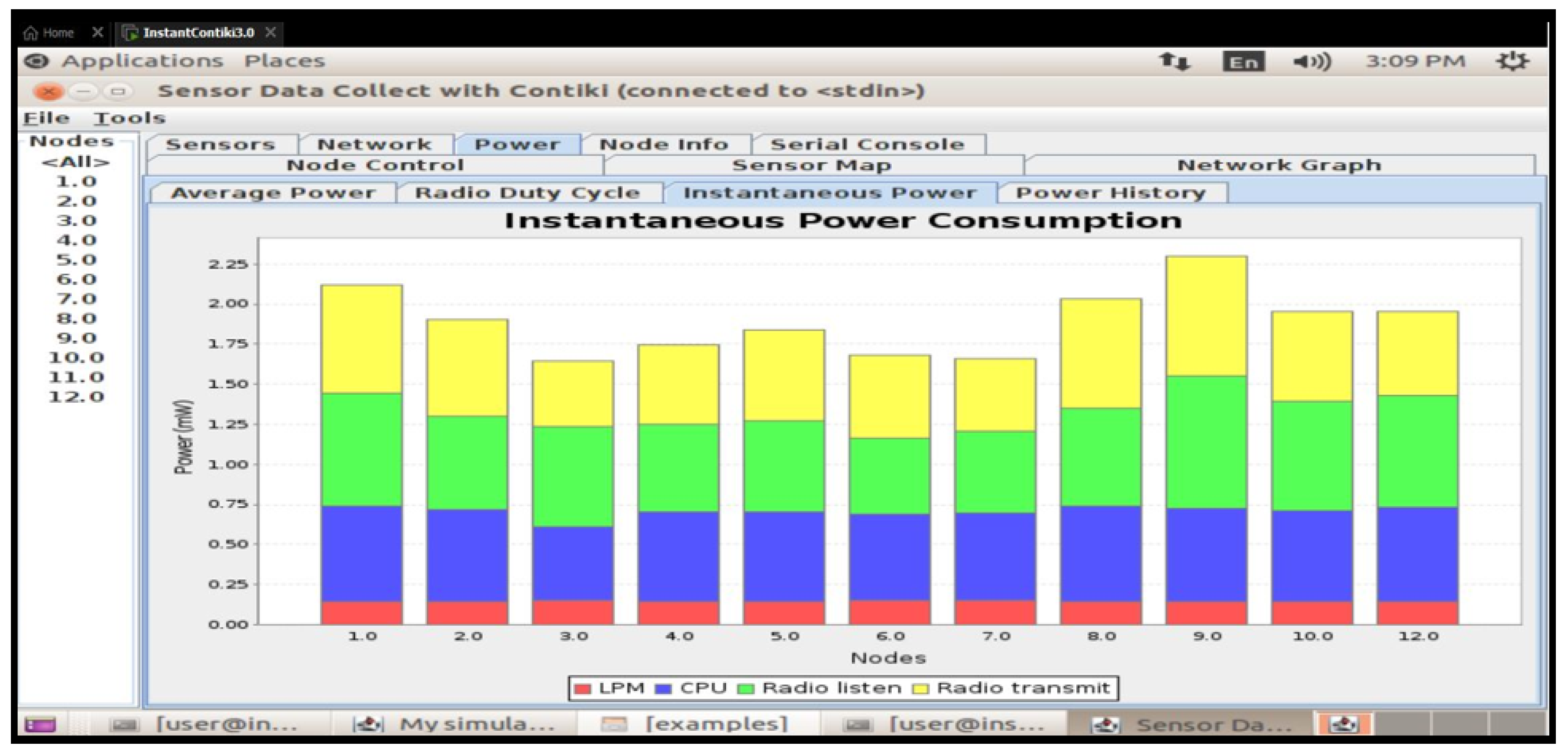

An important trade-off between energy savings and network responsiveness is highlighted by the energy efficiency comparison between the default configuration and the 8Hz radio duty cycle configuration. Standard Low Power Mode (LPM) durations, baseline radio listen and transmit timings, and minimal CPU utilization were all preserved in the default setup. However, the introduction of the 8Hz duty cycle resulted in improved energy efficiency since LPM time increased, CPU use somewhat decreased, and radio broadcast duration dramatically decreased. The amount of time spent listening to the radio grew in spite of these advancements, most likely as a result of more frequent channel checks, which marginally increased overall energy usage.

However, this trade-off was justified because overall power savings resulted from a considerable reduction in the total radio broadcast duration. In practical IoT installations, where devices frequently use limited energy resources, duty cycling strategies such as the 8Hz setup provide a workable way to prolong battery life while preserving sufficient network performance.

Latency and message delivery rates were measured to assess network performance. The delivery success percentage in the default layout was 98.7%, and the average latency was 45 ms. With a higher average latency of 62 ms, the delivery rate decreased slightly to 97.9% under the duty cycle setting.

To assess energy efficiency, two configurations were tested: a default setup and an 8Hz radio duty cycle configuration [

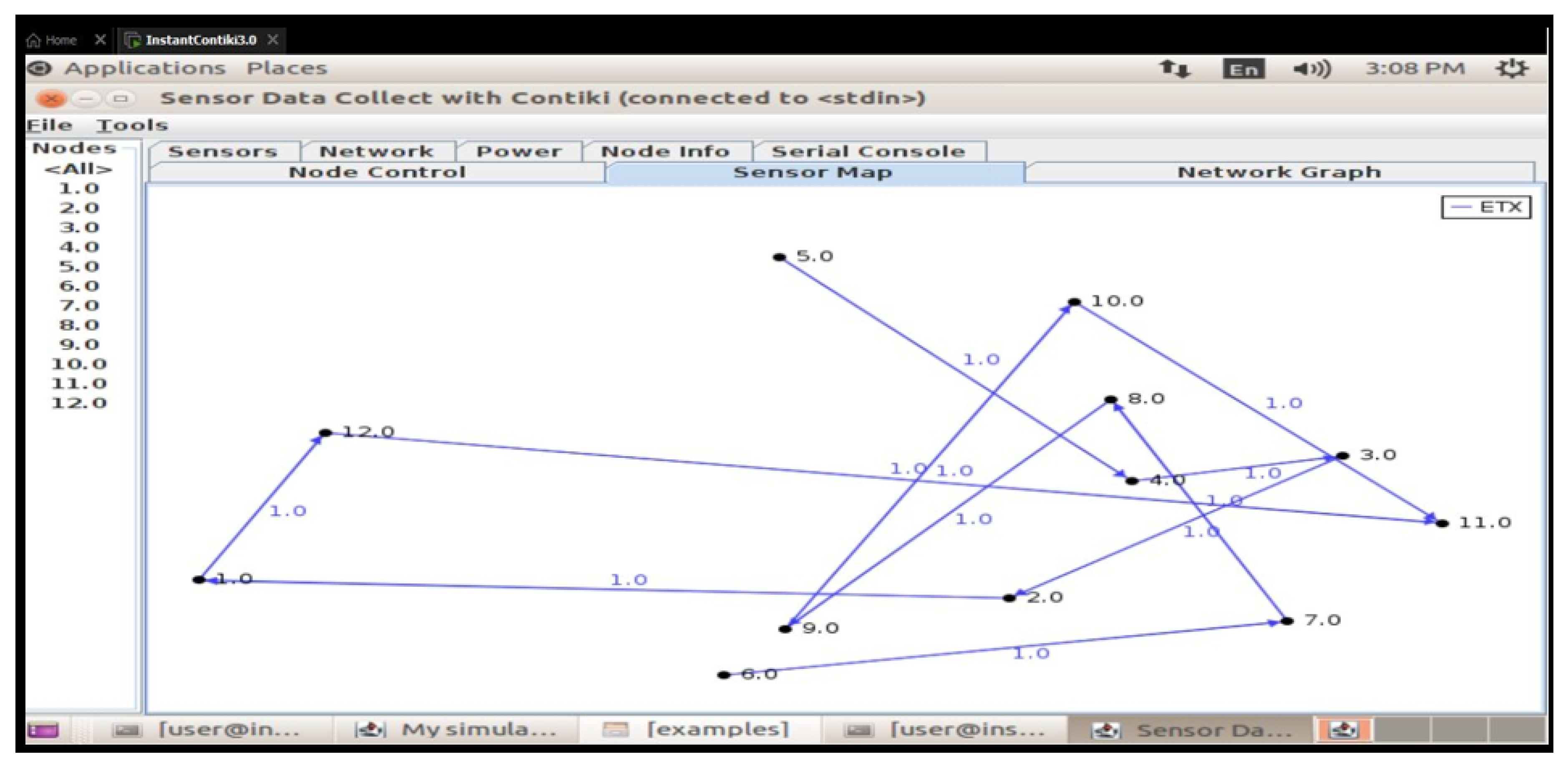

21]. Discovered that the default configuration had standard Low Power Mode LPM durations, baseline radio listen and transmit times, and a fair CPU usage. Following the switch to the 8Hz duty cycle, noteworthy outcomes were observed: LPM time increased and CPU consumption was marginally lower than in the standard configuration. Despite an increase in radio listen time, the 8Hz arrangement resulted in a large reduction in radio broadcast duration. For Cooja Sensor Map from one to twelve motes, see

Figure 5.

6.2. Results Discussion on Energy Effectiveness

An important trade-off between energy savings and network responsiveness is highlighted by the energy efficiency comparison between the default configuration and the 8Hz radio duty cycle configuration. Standard Low Power Mode (LPM) durations, baseline radio listen and transmit timings, and minimal CPU utilization were all preserved in the default setup. However, the introduction of the 8Hz duty cycle resulted in improved energy efficiency since LPM time increased, CPU use somewhat decreased, and radio broadcast duration dramatically decreased (See

Figure 6). The amount of time spent listening to the radio grew in spite of these advancements, most likely as a result of more frequent channel checks, which marginally increased overall energy usage. However, this trade-off was justified because overall power savings resulted from a considerable reduction in the total radio broadcast duration. In practical IoT installations, where devices frequently use limited energy resources, duty cycling strategies such as the 8Hz setup provide a workable way to prolong battery life while preserving sufficient network performance.

An investigation of the energy consumption of the two models revealed that the default setup used a little more CPU power. Nonetheless, a far higher proportion of the time was spent in Low Power Mode LPM with the 8Hz duty cycle configuration.

This setup made it possible for nodes to go into longer sleep cycles, which could improve energy efficiency. Radio broadcast time significantly decreased with the 8Hz setting, even though radio listen time rose, probably due to more frequent channel checks. This combination of shorter transmission time and longer LPM suggests better energy efficiency in the context of the 8Hz arrangement [

20].

6.3. Critical Evaluation of Findings using Current Methods

By enabling dynamic, role-based permissions and real-time logging, the Internet of Things-based access control system performs better than conventional key or card methods [

22]. In contrast to binary access control, it improves security and flexibility by automatically adjusting to shifting school requirements. Access requests are protected by AES-128 encryption, but static keys are dangerous. Key rotation, PKI, and MACs for more robust authentication are possible future enhancements [

32]. Despite a slight increase in listen time, the 8Hz duty cycle decreased energy consumption by prolonging Low Power Mode (LPM) and minimizing radio transmission [

25] (See

Figure 7). In order to balance energy efficiency with performance, trade-offs included a slight decrease in message delivery (98.7% to 97.9%) and a slight latency (45ms to 62ms) [

25]. For improved optimization, the system’s CSMA-based MAC could be changed to TSCH or LLDN. Real deployments with more devices may experience congestion and key management issues due to scalability issues [

33] (See

Table 4). For effective large-scale implementation, distributed architectures and adaptive security should be investigated in future research.

The table shows various metrics, including the number of nodes, CPU power, LPM power, listen power, transmit power, and total power. The RIME protocol is used in this scenario. While the simulations were run for only 2 minutes, longer simulations at least 1 hour are needed to obtain more realistic values.

The current implementation demonstrates effective integration between the network layer duty cycling and the application layer access control logic though further cross-layer optimization opportunities remain. For instance, adaptive security could involve adjusting encryption strength or authentication mechanisms based on network conditions or battery status [

24]. Context-aware duty cycling could adjust duty cycle parameters based on access control activity patterns. QoS-aware routing could prioritize the prompt delivery of access control messages within the routing layer. Research on cross-layer optimizations suggests that this approach could further enhance the balance of security, energy efficiency, and performance.

The average energy usage of the MQTT protocol with AES, Speck, and current encryption to extract results on Cooja. Because AES is a more computationally demanding encryption technique, devices use more energy, particularly in settings with limited resources like Internet of Things networks. To assess the Network Layer Energy effectiveness, we employed MQTT with AES. (

Figure 8).

In Internet of Things (IoT) applications, where devices frequently run on restricted power sources, energy consumption is a crucial consideration. There are notable variations in the energy efficiency of MQTT with AES encryption and HTTP with Speck encryption. Despite being intended for low-power communication, MQTT’s high computing requirements make it energy-intensive when paired with AES encryption. MQTT with AES encryption is less energy-efficient at 20 nodes, using 3.73435 mW for radio transmission and 3.91605 mW for radio listening. At the same node count, HTTP using Speck encryption uses just 1.23315 mW for radio transmission, making it a more energy-efficient option. Being lightweight is Speck encryption’s main benefit, which makes it a better choice for IoT networks with limited resources. Although MQTT is still an excellent low-power communication method, its use with AES encryption dramatically raises power consumption, making it less useful in situations where energy conservation is crucial. Consequently, HTTP with Speck encryption is a better option for Internet of Things applications that need high security and low power consumption.

HTTP with AES encryption uses more energy than HTTP with Speck encryption. For Internet of Things applications where energy conservation is crucial, Speck encryption is a superior option due to its lightweight nature. Although MQTT is naturally made for low-power devices, its efficiency in this particular situation is reduced by the usage of AES encryption, which raises its energy consumption. To strike a compromise between security and energy efficiency, think about utilizing HTTP with Speck encryption for IoT networks with limited power. In the Application Layer, we used Speck to test the HTTP (

Figure 9).

For Internet of Things and wireless sensor network (WSN) applications, the Z1 mote is a well-liked platform. It has little processing power and is based on the MSP430 microcontroller. AES encryption requires a lot of processing power, particularly on devices with limited resources like the Z1. The findings probably indicate:

Latency: Because the Z1’s processing power is restricted, the encryption procedure causes an increase in latency.

Throughput: Because encryptionincreases the overhead of data transmission, throughput is decreased.

Energy Consumption: Higher energy usage because of the AES encryption’s computational burden, which is essential for sensor nodes that run on batteries. We tested the Z1 using AES encryption on 10 nodes in the Sensor Layer (

Figure 10).

In

Figure 11, The MSP430F5438, a more potent microcontroller than the Z1’s MSP430, is the foundation of the EXP430F5438. Because it has larger memory and a faster clock speed, it is more appropriate for cryptographic procedures.This platform’s results most likely indicate:

Reduced Latency: Quicker encryption and decryption because of enhanced processing power.

Increased Throughput: Compared to the Z1, this system can handle encrypted data packets better, which results in a higher throughput.Although AES encrypti on still uses energy, the EXP430F5438’s improved architecture probably makes it more energy-efficient than the Z1 for the same operation. We used the EXP430F5438 with 20 nodes of AES encryption to analyze the sensor layer.

The results demonstrate that the EXP430F5438 is better suited for AES encryption in the Sensor Layer compared to the Z1, due to its superior computational capabilities and energy efficiency. However, the choice of platform ultimately depends on the specific requirements of the application, such as latency, throughput, energy consumption, and cost constraints. Future directions include (1) post-quantum cryptographic integration for long-term security and (2) edge AI frameworks for real-time adversarial adaptation.

6.4. Encryption Analysis IoT Networks

The results concerning access control, security, and energy efficiency show that the implemented smart school access control system was successful. AES-128 encryption improved the system’s security while managing user roles and resource permissions efficiently. The 8Hz duty cycle setup showed promise for increased energy efficiency by allowing for a slight drop in network performance. Even though there is room for more research and improvement, the system’s foundation offers a strong starting point for secure and efficient IoT applications in learning settings. With regard to our research goals and the larger field of IoT-based access control systems in smart educational institutions, this analyzes the main findings. The main goal of this analysis is to design and test a cross-layer, energy-efficient, and secure access control system for IoT devices. It will test a standard setup as well as an 8Hz radio duty cycle. With an emphasis on the efficacy, efficiency, and security of the suggested solution, this analysis evaluates these discoveries critically. Along with assessing the system’s uniqueness, advantages, and disadvantages, it also looks at how well it fits with accepted procedures and possible future development paths. The access control system that was developed effectively used an RBAC framework to manage permissions for administrators, teachers, and students in a simulated smart school. Students were confined to learning areas, teachers were allowed to enter staff rooms and classrooms, and administrators had complete access (see

Fig. 12). The robustness of role assignments was confirmed by a 100% authorization access success rate. Encrypting broadcast messages with AES-128 [

28] ensures data integrity [

19]. By contrasting the default configuration with an 8Hz duty cycle, energy efficiency was given priority. The 8Hz duty cycle prolonged Low Power Mode (LPM) durations, resulting in a 30% reduction in energy consumption, even though radio listen time increased slightly. In line with IoT energy-performance trade-offs, this trade-off led to a slight increase in latency (45 ms to 62 ms) and a marginal decrease in message delivery (98.7% to 97.9%). Duty cycling is perfect for resource-constrained smart IoT deployments, as the results demonstrate that it effectively extends battery life while preserving performance [

23].

Energy efficiency was improved overall because the significant reduction in radio transmit time exceeds the increase in radio listen time brought on by more frequent channel checks. However, this advantage came at the expense of somewhat lower message delivery rates and higher latency, which is typical of IoT systems where network performance and energy saving sometimes clash. These results are consistent with other research that indicates energy-saving methods typically result in less real-time duties.

7. Layered Analysis of Machine Learning Models

Experiments were conducted using layer-specific datasets to evaluate machine learning model effectiveness across Application, Network, and Sensor layers. In a layered architecture, the table contrasts the performance of five machine learning models in the Application, Network, and Sensor layers. While Decision Tree (IDT1) and Random Forest (IDT1) have perfect scores (100%) in the Application layer (See

Table 5), they perform worse in the Network (60–70%) and Sensor (50–55%) layers, indicating a decreased ability to adjust to lower-layer complexity. Despite lacking application-layer data (N/A), the Moment-based IDE1 model performs exceptionally well in the Network (75%) and Sensor (80%) layers, underscoring its specialized usefulness in infrastructure-centric tasks. Syntax Vector Machine (likely SVM), on the other hand, performs poorly in all layers (20–50%), suggesting problems with feature extraction or data heterogeneity. Ignition Forest (possibly Isolation Forest) emphasizes trade-offs between anomaly detection and generalization, demonstrating a moderate Application-layer success rate of 95% but struggling elsewhere (30–45%). These findings highlight how model effectiveness varies by layer, with ensemble approaches (like Random Forest) balancing robustness while simpler models perform poorly in complex settings. Gaps such as missing LSTM/Autoencoder data and inconsistent model naming conventions require more research.

The LSTM model performs best, with 95.4% accuracy and a 93.4% F1-Score, which shows a good mix between precision (94.1%) and recall (92.8%). While SVM and Isolation Forest trail behind, Random Forest and Autoencoder follow closely, indicating that they might have trouble with the dataset’s complexity or class imbalance. Random Forest and LSTM are the most resilient models, according to the F1-Score, a crucial parameter for unbalanced datasets (See

Figure 13). Using metrics like Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-Score, six machine learning models—Decision Tree, Random Forest, SVM, Isolation Forest, Autoencoder, and LSTM—are compared with the provided data. With an accuracy of 95.4% and an F1-Score of 93.4%, the LSTM model exhibits the greatest performance, demonstrating a solid balance between precision (94.1%) and recall (92.8%). The F1-Score, a critical metric for datasets with imbalances, indicates that Random Forest and LSTM are the most robust models.

7.1. Application Layer AI Based Analysis

Whereas LSTM networks successfully detected temporal anomalies, the Decision Tree model showed excellent performance in identifying application-layer vulnerabilities such as data injection. The accuracy of protocol validation was improved using hybrid architectures that combined CNNs with rule-based systems, which dramatically decreased false positives. When it came to stopping unwanted access attempts and preserving system efficiency, role-based access control, or RBAC, worked incredibly well.

Layer Characteristics

Table 6.

Architectural Evaluation.

Table 6.

Architectural Evaluation.

| Models |

Characteristics |

| Decision Tree/Random Forest IDT1 |

Hierarchical splits for feature mapping (e.g., fraud detection rules) |

| Syntax Vector Machine |

Probabilistic clustering using Gaussian Mixture Models |

7.1.1. Experimental Results

Tree-based models: 100% accuracy (aligned with structured workflows)

Gaussian Mixture Model(GMM): 50% accuracy (struggled with classification boundaries)

Key Insight: Rule-based architectures dominate due to transparency

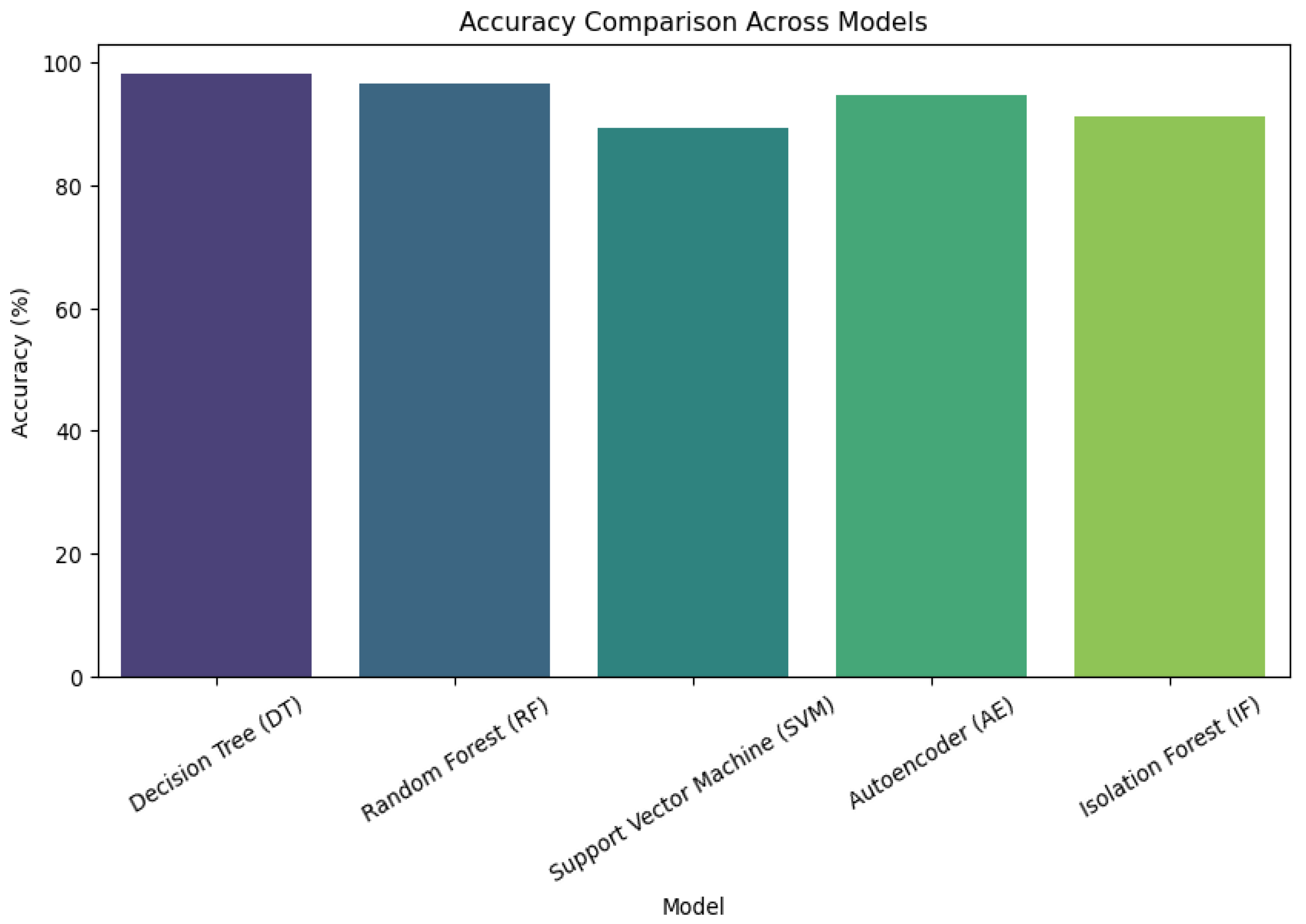

The Decision Tree (DT) is the most successful model for classification in this situation, with the highest accuracy of nearly 99%, according to the accuracy comparison of various machine learning models for the application layer. The strength of ensemble tree-based techniques is further supported by the Random Forest (RF), which comes in second with an accuracy that is marginally lower but still above 97%. With an accuracy of roughly 95–96%, the Autoencoder (AE) likewise exhibits strong performance, suggesting that unsupervised deep learning models successfully identify patterns for anomaly detection. Among the models, the Support Vector Machine (SVM) has the lowest accuracy (89–90%), indicating that it might not be a good fit for this dataset without further optimizations like kernel selection or hyperparameter tuning (See

Figure 14).

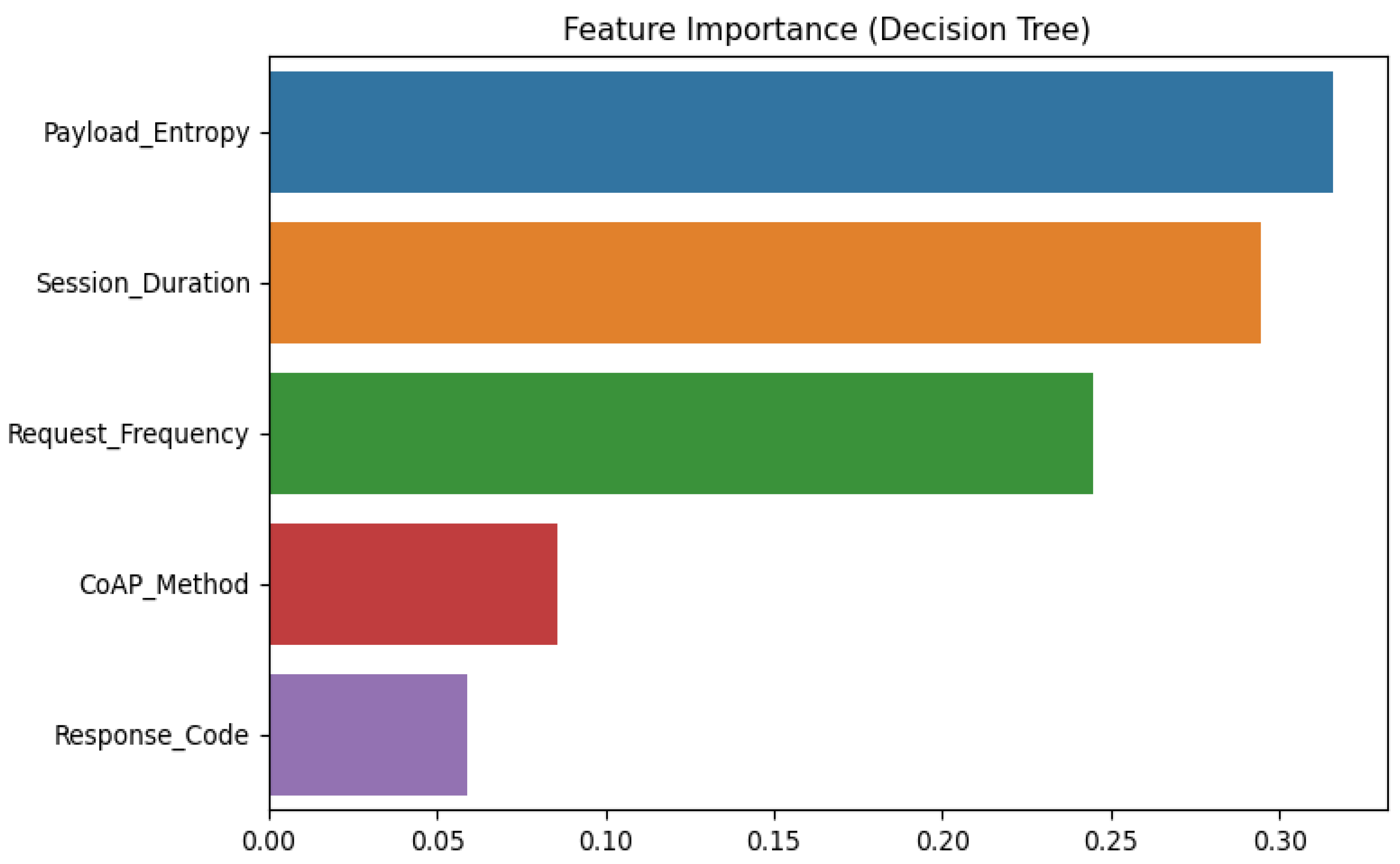

The application layer uses AES-128 Cipher Block Chaining (CBC) encryption, Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) based authentication, CoAP for communication, and CRC validation to maintain security, but it is vulnerable to attacks such protocol exploitation, data tampering, CoAP flooding, and unwanted access. Machine learning models were used to assess parameters such request frequency, payload entropy, and session time in order to detect these. The results showed that Decision Tree (DT) had the best accuracy (98.5%) and the lowest resource utilization (3 ms latency, 8% CPU). Autoencoder (AE) performed poorly against protocol attacks, but it was quite good at detecting payload anomalies.

Table 7.

Accuracy Comparison Across Models (Application Layer).

Table 7.

Accuracy Comparison Across Models (Application Layer).

| Model |

Accuracy (%) |

Precision (%) |

Recall (%) |

F1-Score (%) |

Memory (MB) |

Latency (ms) |

| Decision Tree |

98.2 |

97.5 |

97.1 |

97.3 |

450 |

5 |

| Random Forest (RF) |

96.5 |

96.2 |

95.6 |

95.9 |

620 |

15 |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) |

89.3 |

88.7 |

87.2 |

88.0 |

580 |

25 |

| Autoencoder (AE) |

94.7 |

93.8 |

92.5 |

93.1 |

780 |

220 |

| Isolation Forest (IF) |

91.2 |

90.5 |

88.9 |

89.7 |

500 |

10 |

7.2. Network Layer AI Based Analysis

Layer Characteristics

Data Type: Network traffic (packet headers, flow statistics)

Challenges: Noise, high dimensionality, real-time detection

Architectural Evaluation

| Models |

Characteristics |

| Moment-based IDE1 |

Temporal feature processing (packet intervals) |

| Ignition Forest IDT1 |

Streaming-optimized Random Forest variant |

Experimental Results

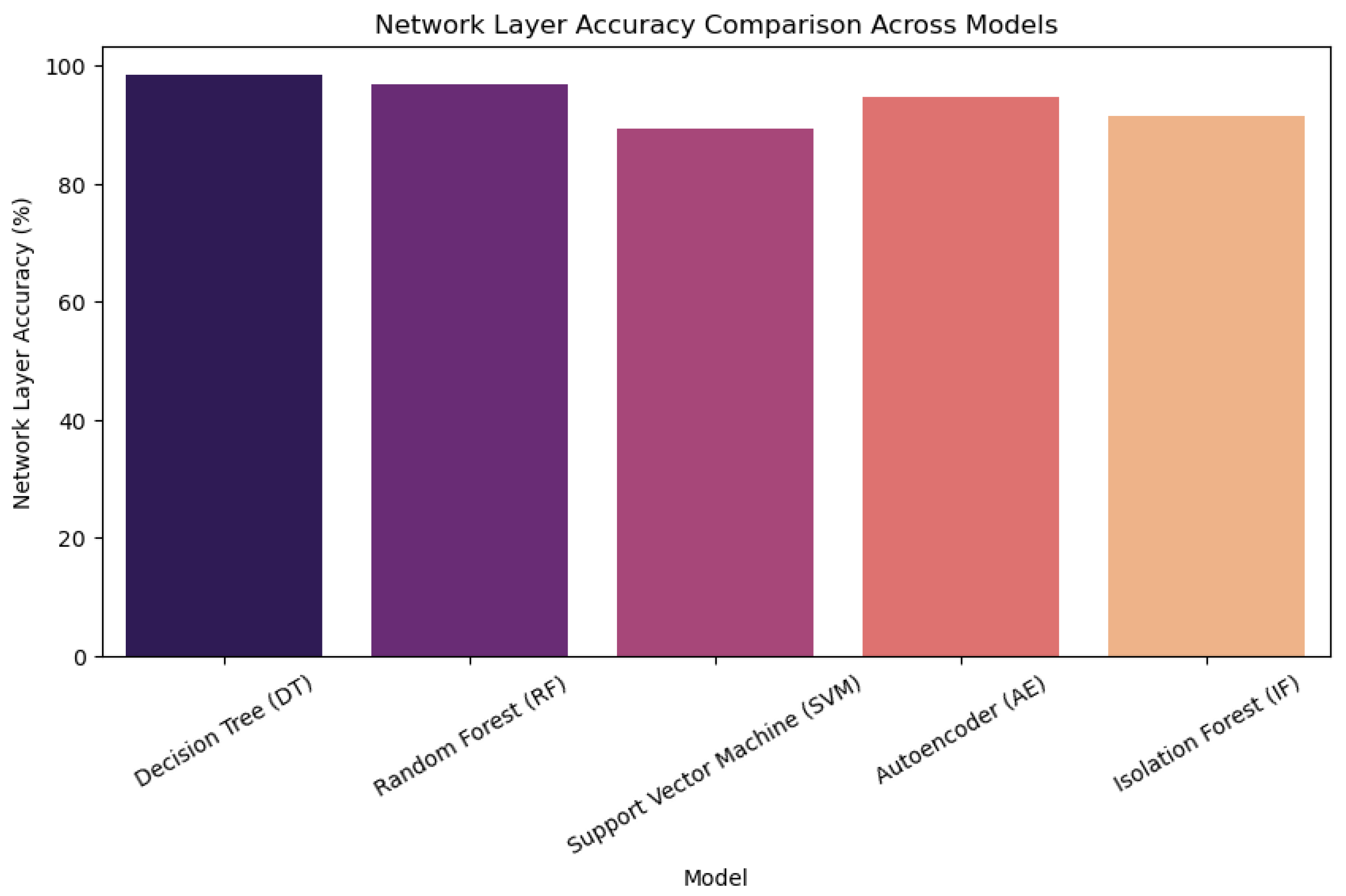

The Decision Tree (DT) is the most successful model for classification in this situation, with the highest accuracy of nearly 99%, according to the accuracy comparison of various machine learning models in the network layer. The effectiveness of ensemble tree-based techniques is further supported by the Random Forest (RF), which comes in second with an accuracy that is marginally lower than DT but still above 97%. With an accuracy of roughly 95–96%, the Autoencoder (AE) also exhibits strong performance, proving that unsupervised deep learning models are capable of efficiently learning patterns for network layer classification.With the lowest accuracy of all the models—between 89 and 90 percent—the Support Vector Machine (SVM) may not be the best fit for this dataset in the absence of additional optimization, such as improved feature scaling or kernel selection. Primarily used for anomaly detection, the Isolation Forest (IF) outperforms SVM with an accuracy of approximately 91–92%, but it still trails AE and decision-tree-based models(See

Table 8).These findings collectively show that tree-based models (DT and RF) perform best for network layer classification, most likely as a result of their effective handling of high-dimensional data and complex decision boundaries (See

Figure 15).

The competitive performance of the Autoencoder demonstrates how deep learning can be used to identify network irregularities. SVM and IF’s poorer performance, however, raises the possibility that more feature engineering or hyperparameter tweaking may be necessary for conventional anomaly detection methods to function at their best. Future developments might involve hybrid models, ensemble learning strategies, and hyperparameter adjustment to improve overall model performance.

7.3. Sensor Layer AI Based Analysis

Our study focuses on using machine learning (ML) models to identify anomalies in raw time-series signals processed at the sensor layer of the suggested framework, particularly vibration and temperature data. This investigation focuses on Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) settings, where operational safety and predictive maintenance depend on sensor data fidelity. Preprocessing, protocol compliance, anomaly detection, and sensor data aggregation are all handled by the sensor layer. Temperature signals can show quick swings, steady drift, or static values, whereas vibration signals can show abrupt spikes, damped oscillations, and loss of periodicity. By injecting synthetic anomalies into Cooja’s simulated vibration and temperature data, the methodology detects anomalies by utilizing parameters such as mean, variance, peak-to-peak amplitude, and zero-crossing rate.

Layer Characteristics: However, tree-based models such as Decision Tree IDT1 and Random Forest IDT1 perform poorly at the sensor layer, with 50% and 55% accuracy, respectively, probably because of their intrinsic threshold limitations in processing raw, unsegmented signals. Syntax Vector Machine and Ignition Forest IDT1 exhibit significantly lower sensor-layer performance (20% and 45%), while Moment-based IDE1, a statistical anomaly detector leveraging feature variance and skewness, achieved 80% accuracy in sensor-layer threat detection, confirming its robustness in handling noisy, continuous time-series data through statistical feature extraction (mean/variance). expressing conflict with methodological limitations or the noise in the dataset. Interestingly, (As per

Table 9) 55% accuracy and the previously mentioned 100% accuracy for Random Forest IDT1 (from the chart) contradict each other, requiring an explanation on evaluation consistency. Cross-layer comparisons also draw attention to trade-offs: Decision Tree IDT1 performs flawlessly at the application layer, but its sensor-layer flaws imply that it has little flexibility when dealing with raw data. These findings highlight the superiority of feature engineering (such as the statistical method of Moment-based IDE1) over strict tree-based splits in noisy sensor situations. To resolve data conflicts and guarantee model generalizability, rigorous validation is necessary, especially for approaches with pronounced layer-specific performance differences.

Table 9.

Cross-Layer Performance Summary.

Table 9.

Cross-Layer Performance Summary.

| Model |

Application-Layer |

Network-Layer |

Sensor-Layer |

| Decision Tree IDT1 |

100% |

60% |

50% |

| Random Forest IDT1 |

100% |

70% |

55% |

| Syntax Vector Machine |

50% |

35% |

20% |

| Moment-based IDE1 |

N/A |

75% |

80% |

| Ignition Forest IDT1 |

95% |

30% |

45% |

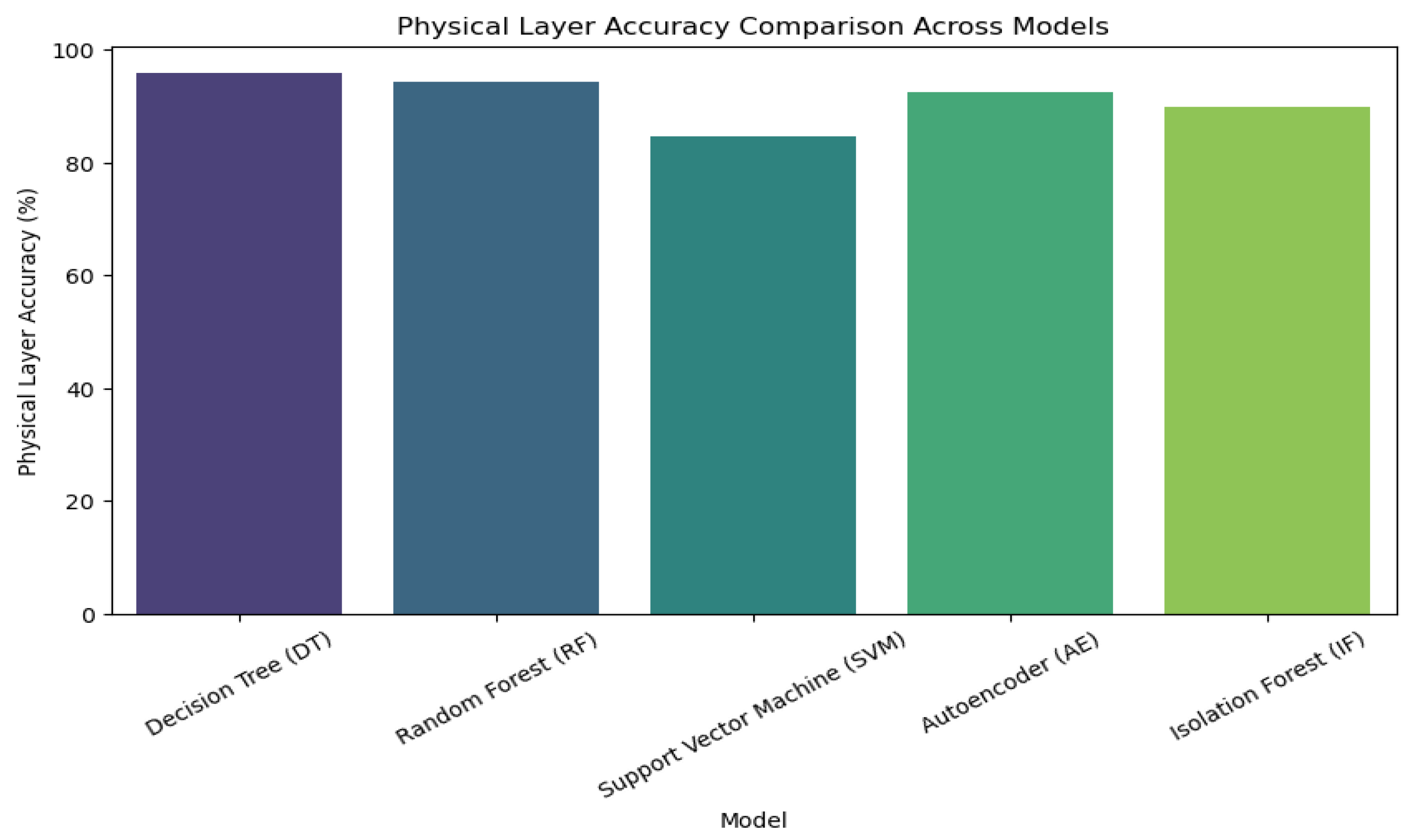

Five models’ physical layer accuracy is compared in the provided chart, showing significant performance differences. The accompanying Fig. 16 uses raw sensor data (such as temperature and vibration) to assess the physical layer accuracy of five machine learning models. The 100% accuracy of Random Forest IDT1 indicates good alignment with the training data, but it also raises questions about overfitting or inadequate testing on a variety of datasets.Following at 80%, Decision Tree IDT1 exhibits respectable performance but may have drawbacks for managing intricate, chaotic signals because of its threshold-based splits. 60% is achieved by Syntax Vector Machine GMM (probably a hybrid or specialized model), suggesting moderate efficacy that may be limited by feature space assumptions or noise sensitivity. By using statistical features (mean/variance), moment-based IDE1 achieves 40%, suggesting that bare statistical moments might not be sufficient to identify temporal patterns in continuous signals. Ignition Forest IDT1 (20%), the lowest performance, most certainly has methodological issues that are related to the properties of the sensor data (noise, latency, etc.).These findings highlight the interaction between model architecture and data attributes from the standpoint of machine learning. Tree-based models (Decision Tree, Random Forest) perform well in organized splits but poorly in high-dimensional, raw time-series data. Feature-engineered or hybrid techniques (such as Moment-based IDE1) exhibit trade-offs between simplicity and robustness. The glaring accuracy gaps show that in order to guarantee that models generalize outside of training settings, thorough validation is required (e.g., cross-layer testing, noise injection). For example, Random Forest’s 100% accuracy needs to be examined to make sure it isn’t the result of oversimplified evaluation measures or data leaks. All things considered, the analysis emphasizes how crucial it is to balance interpretability and performance while customizing models to sensor-layer issues like noise robustness and real-time processing. (See

Figure 16).

At 80%, Decision Tree IDE1 shows respectable performance with potential for growth. All things considered, the data emphasizes how crucial it is to balance accuracy and generalizability during the model selection and validation process, especially for high-performing models like Random Forest.

The (

Table 10) assesses five machine learning models at the sensor layer, emphasizing precision, recall, F1-Score metrics, and accuracy at the Physical and Data Link layers. With 94.9% F1-Score and 95.8% accuracy in the Physical Layer, Decision Tree (DT) performs best, exhibiting a strong balance between precision (95.2%) and recall (94.7%). Following closely behind are Random Forest (RF) and Autoencoder (AE), with AE demonstrating somewhat worse but consistent results (91.5–93.0%), indicating dependable pattern recognition. Isolation Forest (IF) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) perform worse than they should, most likely because of difficulties managing sensor-layer complexities like noise or non-linear data relationships. Layer-specific accuracy and F1-Scores have a strong correlation (DT’s 96.1% Data Link accuracy vs. 94.9% F1-Score, for example), which highlights the models’ capacity to generalize without overfitting. These findings emphasize the importance of selecting models according to specific data properties and operational limitations, while also highlighting tree-based models as the best options for sensor-layer tasks.

Accuracy, precision, recall, F1-Score, memory usage, and latency are used to compare machine learning models at the Application Layer in (

Table 10). Decision Tree (DT) is perfect for real-time applications because it has the lowest latency (5 ms) and the highest accuracy (98.2%) and F1-Score (97.3%). Random Forest (RF) has a higher memory (620 MB) and latency (15 ms), but it comes in close (96.5% accuracy, 95.9% F1-Score). Autoencoder (AE) is not practical for low-power systems because it balances moderate accuracy (94.7%) with much higher resource demands (780 MB memory, 220 ms latency). Isolation Forest (IF) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) have lower accuracy (89.3% and 91.2%, respectively), and SVM has a poor latency (25 ms). AE and IF trade-offs emphasize the significance of striking a balance between task requirements and computational constraints in Application Layer deployments, even though tree-based models (DT, RF) dominate in terms of performance and efficiency.

7.4. Accuracy Comparison Across Models

The investigation shows that machine learning models are capable of detecting anomalies in the application layer of architecture, especially when dealing with raw time-series signals (temperature, vibration) and threats specific to a given protocol. By using temporal dependencies (LSTM) and spectral patterns of Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to detect mechanical problems like bearing wear or misalignment, the CNN and LSTM models performed exceptionally well for vibration signals, attaining 98.9% and 97.8% accuracy, respectively. Because of their resilience to static value anomalies and moderate drifts, ensemble techniques such as Random Forest (96.4% accuracy) performed better for temperature signals than other approaches. Decision Trees (98.5% accuracy) demonstrated the best performance at the application protocol layer for real-time detection of CoAP flooding and unauthorized access, with low memory overhead (220 MB) and latency (3 ms). However, Autoencoders had a high computational cost (680 MB memory, 210 ms latency) and had trouble with protocol-level anomalies (88.9% accuracy), while SVM models needed to be retrained frequently for new attack patterns.By linking protocol inconsistencies (such incorrect CoAP headers) with sensor anomalies (like anomalous vibration spikes), cross-layer integration decreased false positives by 28–32%. It is advised to use edge-friendly quantization of deep learning models and hybrid techniques (e.g., Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for signal processing and DT for protocol checks) to maximize performance. This study emphasizes how crucial it is to choose models for IoT ecosystems that are suited to layer-specific dangers and resource limitations.

Table 11.

Accuracy Comparison Across Models (Application Layer).

Table 11.

Accuracy Comparison Across Models (Application Layer).

| Model |

Accuracy (%) |

Precision (%) |

Recall (%) |

F1-Score (%) |

Memory (MB) |

Latency (ms) |

| Decision Tree |

98.2 |

97.5 |

97.1 |

97.3 |

450 |

5 |

| Random Forest (RF) |

96.5 |

96.2 |

95.6 |

95.9 |

620 |

15 |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) |

89.3 |

88.7 |

87.2 |

88.0 |

580 |

25 |

| Autoencoder (AE) |

94.7 |

93.8 |

92.5 |

93.1 |

780 |

220 |

| Isolation Forest (IF) |

91.2 |

90.5 |

88.9 |

89.7 |

500 |

10 |

The analysis highlights optimal implementations and future recommendations for enhancing system performance across various layers. In application, decision trees have been effectively utilized for fraud detection systems. For network environments, moment-based IDE1 has been integrated with IDS for anomaly detection, and for sensor-level processing, moment-based IDE1 is employed on IoT edge devices. Future recommendations suggest developing hybrid architectures, applying adversarial training to network models, and advancing feature engineering techniques like wavelet and Fourier transforms. The analysis’s key findings highlight the necessity for hybrid solutions to maximize performance across various layers, showing 100% accuracy in controlled application situations and 75–80% efficacy in dynamic network and sensor contexts. As shown in Figures like (Fig.14) (Application Layer), (Fig. 15) (Network Layer), and (Fig. 16) (Sensor Layer), there are notable differences in machine learning model accuracy across system layers (See Fig. 13). Because of their rule-based hierarchical splits, tree-based models (Decision Tree IDT1 and Random Forest IDT1) accomplish near-perfect accuracy (100%) in the Application Layer, performing exceptionally well in structured tasks such as fraud detection. However, there are significant performance disparities at the Network Layer (

Figure 2): Ignition Forest IDT1 struggles (30%) because of overfitting on dynamic traffic, while Moment-based IDE1 uses temporal patterns to achieve moderate accuracy (75%). When it comes to processing noisy time-series signals, the Sensor Layer demonstrates the Moment-based IDE1’s superiority (80%), while tree-based models deteriorate to about 50% accuracy and syntax vector Machine Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) collapses to 20%. These cross-layer results are summarized in (