1. Introduction

In-line filters play an important role in optical sensing [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5] and mode-locked fiber lasers [

6]. Now, as far as we know, there are mainly five types of in-line filters, namely FBG filters [

7,

8,

9], LPG filters [

10,

11,

12], Lyot filters [

13], MZI filters [

14,

15] and Birefringence plate filter [

16]. Pattern interference is the fundamental function of MZI filters. There are two types of pattern interference: interference between the core mode and the cladding mode and interference between the core mode and the core mode.

Currently, there are numerous MZI solutions, including a pair of long-period fiber gratings (LPGs) [

17], segment fusing of specialty fiber [

18,

19,

20], microfiber-based structures [

21], mode field or core-mismatch fusion splice [

22], and in-fiber air cavities [

23]. Each of these options has drawbacks. For instance, the interference spectrum range is constrained by the LPG band width, and LPGs need to be manufactured precisely. High contrast stripes are only produced by a small number of designs, and specialty fiber is costly. Due to the laborious human assembly of fiber parts, fiber core lateral mismatch or mode field fusion is difficult to do with good consistency. Devices with microfiber and air cavities are intrinsically weak and unreliable. The core-cladding mode interference used in the aforementioned designs typically has a complex, uneven interference spectrum and a significant insertion loss. Furthermore, it is hard to manage their free-spectral range (FSR) precisely.

Ultrafast laser direct writing is a multifunctional tool enabling permanent modifications of physical and chemical properties inside transparent solids, such as glass, crystal, and polymer [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. In the past, femtosecond micromachining has been used to demonstrate fiber in-line MZIs [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Nevertheless, the majority of these methods for directly writing MZI are multi-line direct writing methods, which will introduce increased difficulty in direct writing and lower the quality of MZI.

In this work, we propose a single-line direct-writing method. The operation of this approach is straightforward and does not require sophisticated path scanning control. By using this method, we developed an MZI-based filter with a length of 516 μm and compared it with the findings that have already been published [

30]. The direct writing length is cut by 2.4 times under the same free spectral range, and the insertion loss is lowered by 2.7 times with the same extinction ratio. This result's successful implementation has created a strong basis for the later development of integrated mode-locked fiber lasers.

2. Method

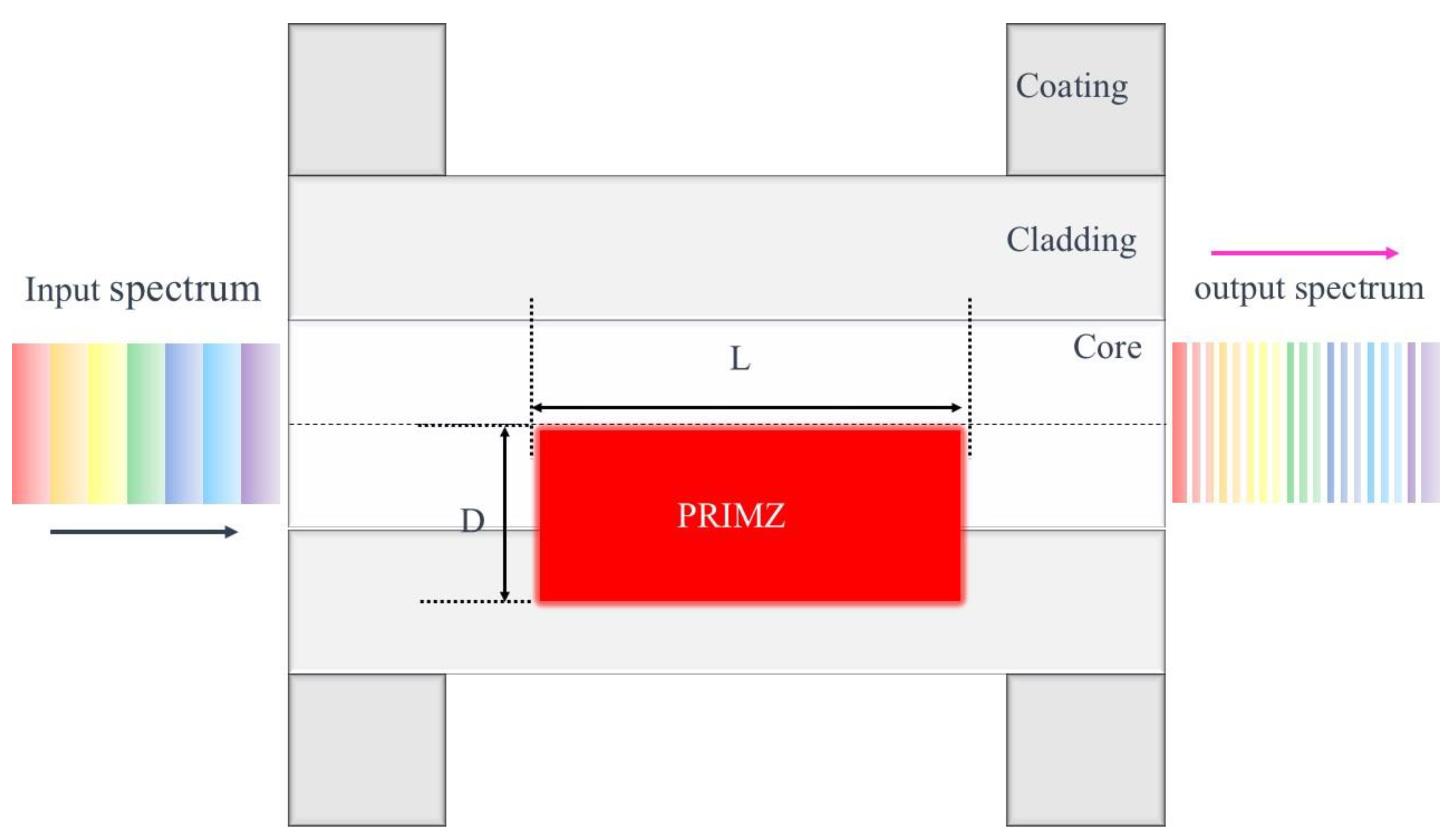

The off-axial positive refractive index-modified zone (PRIMZ) is the main structure of the fiber-core MZI, as depicted in the schematic design in

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the all-in-fiber-core MZI .

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the all-in-fiber-core MZI .

Femtosecond laser inscription modifies the refractive index of a portion of the core and cladding with length L and width D to form the PRIMZ. The initial single-mode fiber segment is transformed into a few-mode fiber section with the introduction of the PRIMZ. As a result, the effective refractive index difference between various modes can produce an optical path difference (OPD) when incident light passes through the few-mode fiber section. An MZI filter is created when these modes interfere with one another. Following propagation across the length L of the modified fiber, the phase difference between the fundamental mode and a higher-order mode can be roughly described as

where λ is the wavelength of light in vacuum and

is the effective refractive index difference between the fundamental mode and the higher-order mode. Where m is an integer and the phase difference meets the formula φ=(2m+1) π, an intensity dip is seen.

The OPD

determines the interference fringe pattern's FSR in such a way that

The density of the comb-like transmission spectra is determined by the FSR.

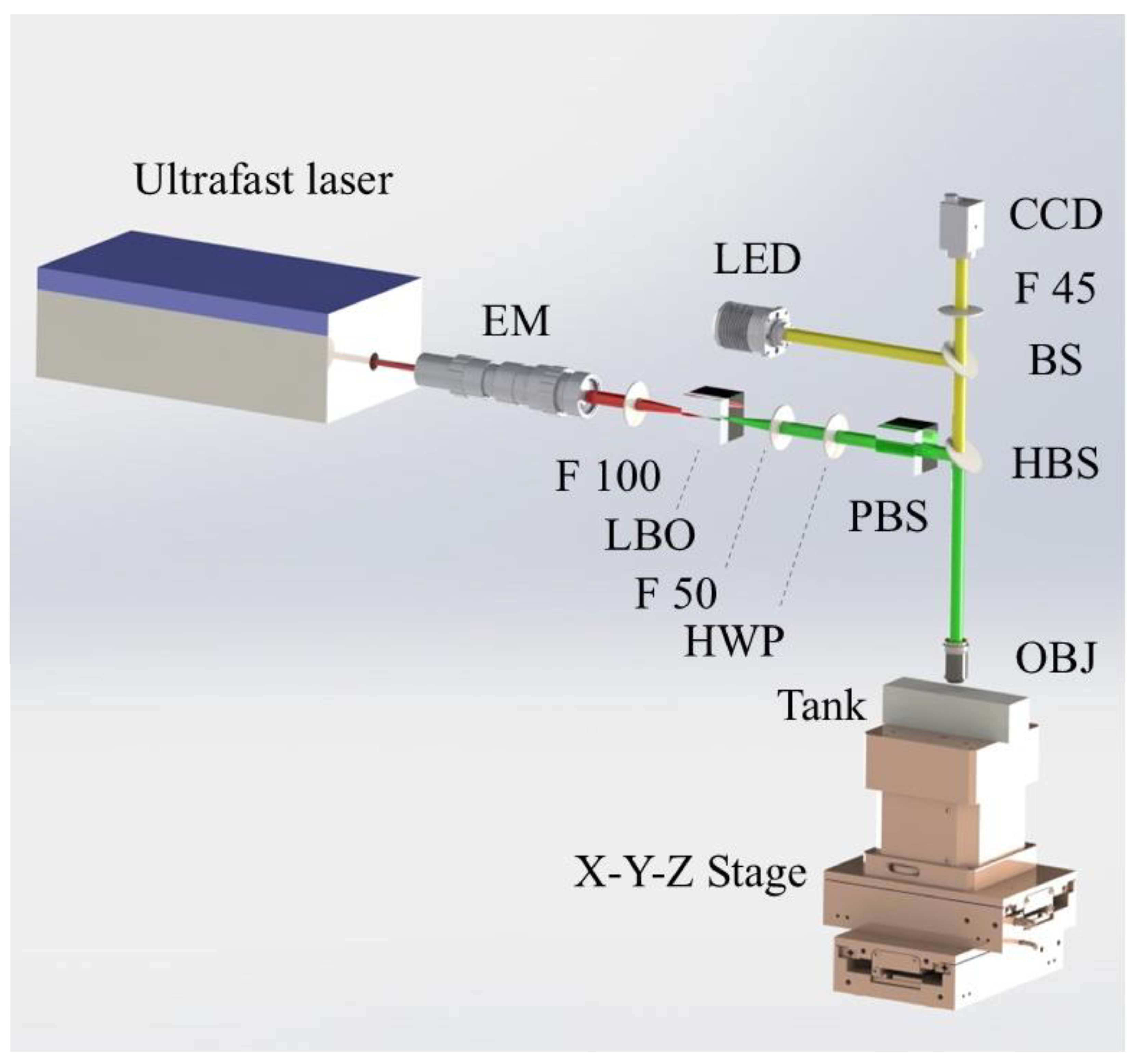

The setup used for the ultrafast laser direct writing of the MZI filters in the SMF is

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

processing apparatus for optical fiber MZI filters. EM: expansion mirror; F 100, F 50, F 45: Lens; HBS: harmonic beam splitters; HWP: half wave plate; PBS: polarization beam splitters; BS: beam splitter; OBJ: oil immersion objective; LED: light emitting diode; CCD: charge coupled device.

Figure 2.

processing apparatus for optical fiber MZI filters. EM: expansion mirror; F 100, F 50, F 45: Lens; HBS: harmonic beam splitters; HWP: half wave plate; PBS: polarization beam splitters; BS: beam splitter; OBJ: oil immersion objective; LED: light emitting diode; CCD: charge coupled device.

An ultrafast laser (Qingdao Zimao Laser, TCR-FS-1030-20) with a center wavelength of 1030 nm, a pulse width of 900 fs, and a repetition frequency of 200 kHz was used in our experiment. The LBO crystal doubles the frequency, producing green light at 515 nm. The fundamental frequency light is then filtered out using a harmonic beam splitter to guarantee that the frequency doubling light has a main direct writing function. A segment of three-dimensional moto stage (Newport, Inc.) with a 0.1 μm resolution is fixed to a section of striped single-mode fiber (SMF, Corning, HI1060). Using an oil-immersed objective lens (Leica, 100×, NA 1.25), the laser beam is focused into the fiber core. The fiber was submerged in index matching oil (SHINHO, 1.47) to reduce the fiber surface’s lens effect. In order to add MZI filters, the ultrafast laser beam is scanned parallel to the fiber axis during manufacturing at a speed of 5 μm/s. The spot size of the focused laser beam was roughly 3 μm. The laser pulse has an energy of 57.15 nJ. The direct writing direction is parallel to the polarization direction of the ultrafast laser. At the predetermined speed, scan along the optical fiber's axial direction. In order to measure the spectral response of the MZI filters under the current conditions, we independently constructed a wide-spectrum light source with an effective spectral width of 200 nm by using a gain fiber (LIEKKI, Yb1200-6/125DC-PM) and a single-mode pump (Mai Rui Optoelectronics Co., LTD) with a center wavelength of 976 nm. An optical spectrum analyzer (Yokogawa AQ-6370D) was then connected at the end of the single-mode fiber to assess the output spectral changes in real time after it had been input into the fiber.

3. Results

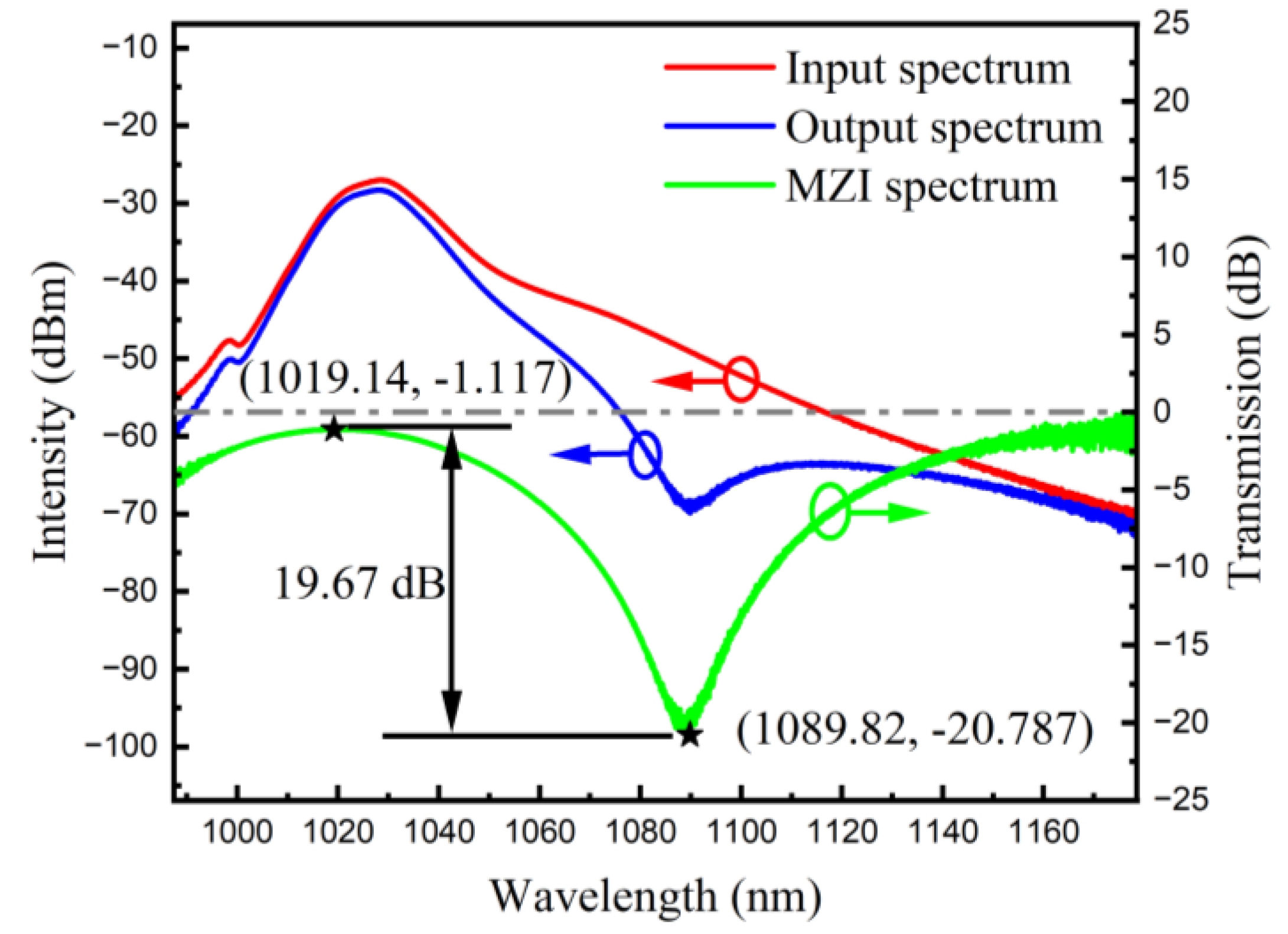

The input spectrum and transmission spectrum of the wide-spectrum light source's and the MZI filter's transmission spectrum are displayed in

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

the input spectrum, transmission spectrum of the wide-spectrum light source and the transmission spectrum of the MZI filters.

Figure 3.

the input spectrum, transmission spectrum of the wide-spectrum light source and the transmission spectrum of the MZI filters.

As can be seen from the green solid line in

Figure 3, the central wavelength of the loss peak is 1089.82 nm, and the central wavelength corresponding to the adjacent peak with the highest intensity is 1019.14 nm. The extinction ratio is 19.69 dB. The wavelength spacing between the adjacent highest and lowest points is 70.68 nm, which allows us to roughly determine that the free spectral range of the current MZI is 141.36 nm. Substituting into formula 3, the refractive index difference can be calculated to be 0.016. The refractive index change in reference [

30] is 0.011, which is basically the same. In figure 3, the red solid line represents the output spectrum of the self-made broadband ASE light source, and the blue solid line represents the transmission spectrum of the broadband ASE light source after passing through our directly-written MZI filter.

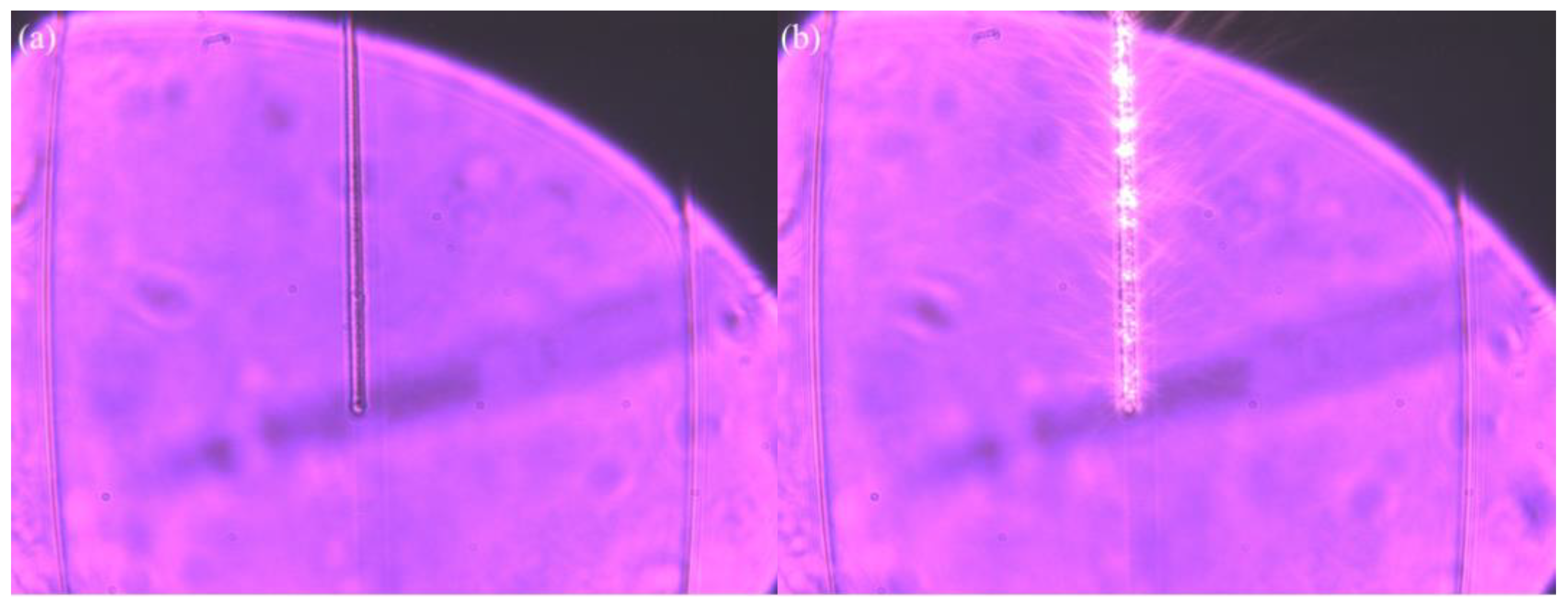

The microscopic view of the MZI filter is shown in

Figure 4.

Figure 4.

the microscopic view of the MZI filters; (a) the top view of the fiber core position; (b) the top view after inputting the wide-spectrum light source.

Figure 4.

the microscopic view of the MZI filters; (a) the top view of the fiber core position; (b) the top view after inputting the wide-spectrum light source.

Figure 4 shows the physical diagram of the MZI filter completed in the HI1060 optical fiber using our method. As can be seen from

Figure 4a, most of the engraved lines are inside the core of the fiber, and a small part is in the cladding. Moreover, the uniformity before and after the engraving is good. From

Figure 4b, it can be observed that when a wide-spectrum light source is input, a significant amount of scattered light from the MZI filter can be clearly seen, but most of the light is confined within the waveguide. This also provides evidence that the straight-written engraved lines have excellent waveguide properties.

4. Simulation

In order to deeply investigate the rationality of the MZI filter we have completed, we conducted simulations using the commercial Rsoft software. The simulation parameters are as follows: elliptical cylindrical waveguide, length 516 μm, elliptical minor axis of the cross-section 3 μm, elliptical major axis 4 μm. The Gaussian beam propagates inside the optical fiber, with the core refractive index of 1.464, the cladding refractive index of 1.458, the written waveguide refractive index of 1.477, the core diameter of 5.3 μm, and the cladding diameter of 125 μm. The calculation is performed using the BeamPROP module.

The simulation results are shown in

Figure 5. The central wavelength corresponding to

Figure 5a is 1.019 um, which belongs to the passband region of the MZI filter. The left figure in

Figure 5a represents the mode field distribution, and the right figure corresponds to the intensity variation curve. A significant modulation phenomenon occurs in the waveguide region, and then it passes through the waveguide with a relatively high transmittance. The central wavelength corresponding to

Figure 5b is 1.089 um, which belongs to the stopband region of the MZI filter. The left figure in

Figure 5b indicates that at the wavelength of 1.089 um, the mode field is basically blocked. The right figure of

Figure 5b shows the intensity variation curve with the lowest transmittance passing through the waveguide.

Figure 5c is the wavelength-dependent full-scan curve. The vertical axis represents the normalized transmittance. The lowest transmittance wavelength corresponds to the experimental results in

Figure 3, and the entire broadband range corresponds to the wavelength range of the broadband light source. This simulation well demonstrates the rationality of implementing MZI using single-line direct writing waveguides.

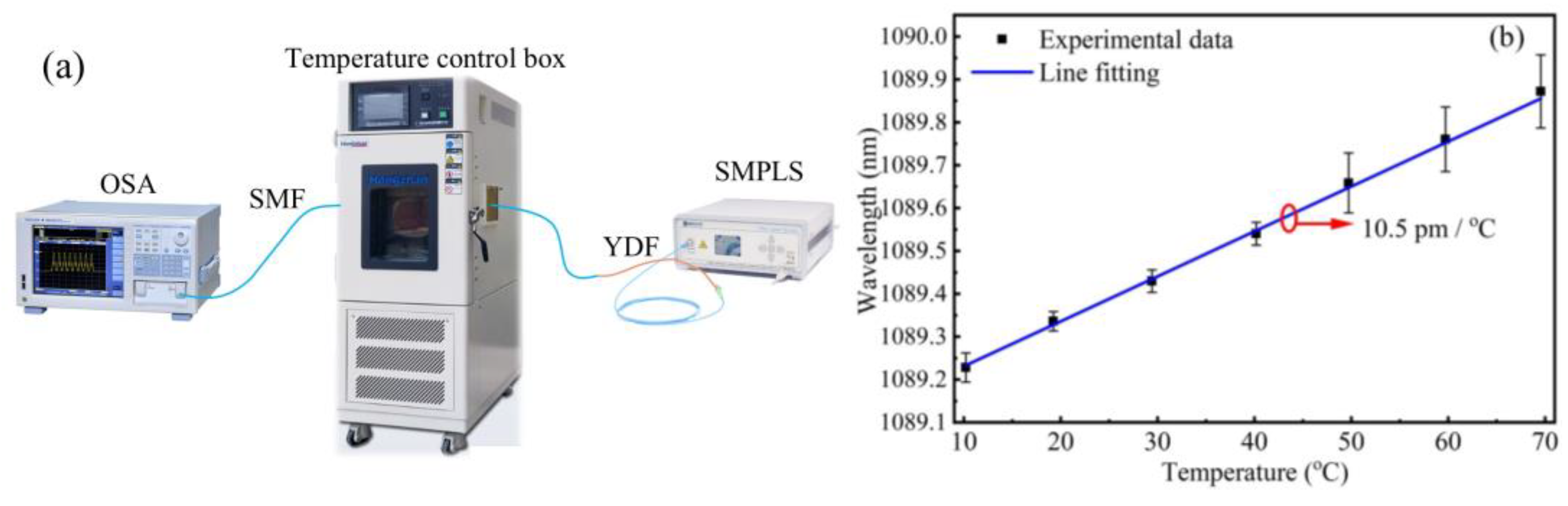

In order to verify the temperature response characteristics of the MZI filter, we independently constructed a measurement device, as shown in figure 6a.

Figure 6b shows the temperature response curve. To ensure the validity of the data, we collected data every 10 minutes, and for each temperature, we collected three sets of data. As can be seen from

Figure 6b, the central wavelength shifts towards the longer wavelength direction, with a shift of 10.5 pm per degree Celsius. Therefore, it can be applied in the field of temperature sensing. For mode-locked fiber lasers, a small temperature drift is desirable.

Figure 5.

the interference spectra of the wave crests and troughs under the current experimental parameters, the corresponding wavelengths of (a) are 1.019 μm; (b) correspond to 1.089 μm; (c) the wavelength-dependent full-scan curve.

Figure 5.

the interference spectra of the wave crests and troughs under the current experimental parameters, the corresponding wavelengths of (a) are 1.019 μm; (b) correspond to 1.089 μm; (c) the wavelength-dependent full-scan curve.

Figure 6.

the (a) temperature response measurement schematic diagram; SMPLS: single mode pump light source; YDF: ytterbium doped fiber; OSA: optical spectrum analyzer., and (b) temperature response curve of the MZI filter.

Figure 6.

the (a) temperature response measurement schematic diagram; SMPLS: single mode pump light source; YDF: ytterbium doped fiber; OSA: optical spectrum analyzer., and (b) temperature response curve of the MZI filter.

5. Discussion

Firstly, we proposed a simple single-line direct writing method, which reduced the difficulty of multi-line direct writing in MZI and achieved the same filter depth. We also adjusted the line distribution to be applicable to a wider range of applications.

Table 1 presents the detailed comparison results of this method with the multi-line direct writing method. It is worth noting that we have for the first time applied this method to the HI1060 optical fiber, which will facilitate the application of the all-fiber MZI in 1um mode-locked fiber lasers. The pulse width of the ultra-fast laser we use is 900 fs. This will provide a valuable reference. Ultra-fast lasers with a pulse width greater than 500 fs can still etch excellent waveguide structures. Secondly, regarding the experimental results shown in

Figure 3, if a wider broadband light source is used, more details of the transmission spectra of the MZI filters will be observable. In our subsequent research, we will increase the waveguide length of the MZI to reduce the value of the free spectral range, because only when the free spectral range is less than 15nm will it be more conducive to achieving mode locking. Again, the reason why we didn't directly write a longer MZI filter at the beginning was that the loss would change with the increase of distance. To better demonstrate the direct writing effect of our method, we chose an MZI whose central wavelength corresponded to the central wavelength of the broadband light source. Finally, although our method can reduce the writing difficulty of the all-fiber MZI, there is still much room for improvement. That is, by using a pulsed-packet laser, we can effectively lower the thermal damage threshold. We will demonstrate this change in our subsequent research results.

Table 1.

Comparison of Different Direct Writing Methods for All-Fiber MZI.

Table 1.

Comparison of Different Direct Writing Methods for All-Fiber MZI.

| Fiber type |

Waveguide distribution |

Waveguide length/mm |

|

Number of scans |

Insertion loss |

Filtering depth |

Working range |

Direct write pulse width |

References |

| SMF-28e |

The core accounts for 50%, and the cladding is 0 um thick. |

2 |

4.1 |

9 |

3 |

20 |

1400-1700 |

350 |

[30] |

| SMF-28e |

The core accounts for 25%, and the inner layer of the cladding is 2 microns. |

5 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

- |

1250-1550 |

350 |

[31] |

| HI1060 |

The core accounts for 50% and the cladding is 1 micron thick. |

0.516 |

3 |

1 |

1.1 |

19.665 |

1000-1160 |

900 |

This work |

6. Conclusions

In summary, we have proposed a single-line direct writing method, which not only reduces the difficulty of multi-line etching of waveguides, but also achieves the same modulation effect. We first applied this method to the HI1060 optical fiber and successfully constructed a MZI filter with a length of 516 micrometers. To verify the rationality of the MZI filter, we conducted simulations using commercial software, and the results were basically consistent with the experimental results. Finally, we measured the temperature response curve of the MZI filter, demonstrating its potential applications in temperature sensing and mode-locked fiber lasers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and L.X.; methodology, L.X. and X.H.; validation, X.H.; formal analysis, Y.P.; investigation, L.X., Y.L., X.H. and Y.P.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, L.X.; writing—original draft preparation, L.X.; writing—review and editing, X.C.; supervision, X.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Acknowledgments

First of all, I would like to express my gratitude to Xiangyu Chen and Yuanchuan Huang from Wuhan Hongtuo New Technology Co., Ltd. for their meticulous guidance on this experiment. Secondly, we would like to express our gratitude to Qingdao Free Trade Technology Co., Ltd. for supplying the ultrafast laser needed for this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xu, Y.; Lu, P.; Qin, Z.; Harris, J.; Baset, F.; Lu, P.; Bhardwaj, V. R; Bao, X. Vibration sensing using a tapered bend-insensitive fiber- based Mach-Zehnder interferometer. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 3031–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, S. Ultrasensitive long-period gratings sensor works near dispersion turning point and mode transition region by optimally designing a photonic crystal fiber. Opt. Laser Technol. 2019, 112, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jung, Y.; Choi, H.; Sohn, I.; Lee, J. Hybrid LPG-FBG based high-resolution micro bending strain sensor. Sensors 2021, 21, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Sui, R.; Peng, Z.; Meng, Y.; Zhong, H.; Shan, R.; Liang, W.; Liao, C.; Yin, X.; Wang, Y. Wide-range OFDR strain sensor based on the femtosecond-laser-inscribed weak fiber Bragg grating array. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 5819–5822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Liu, B.; Liu, D.; Liu, D.; Wang, F.; Guan, C.; Wang, Y.; Liao, C. Femtosecond laser inscribed excessively titled fiber grating for humidity sensing. Sensors 2024, 24, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, A.; Buckley, J.; Renninger, W.; Wise, F. All-normal-dispersion femtosecond fiber laser. Opt. Express 2006, 14, 10095–10100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Chiang, K.S. Transverse-mode switchable passively mode-locked fiber laser based on a two-mode fiber Bragg grating. OECC/ACOFT, 2014; 65–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Yan, Z.; Mou, C.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, L. Narrow bandwidth passively mode locked picosecond erbium doped fiber laser using a 450 tilted fiber grating device. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 16708–16714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Huang, X.; Li, X.; Luo, P.; Gao, C.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Xi, F.; Yin, X.; Zhang, K. 1.9 µm ultra-narrow spectral width mode-locked pulsed laser based on femtosecond laser inscribed FBG. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 2024, 181, 108441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostovalov, A. V.; Wolf A., A.; Babin S., A. Long-period fiber grating writing with a slit-apertured femtosecond laser beam (λ = 1026 nm). Quantum Electronics 2015, 45, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shen, F.; Shu, X.; Zhou, K.; Jiang, H.; Xia, H.; Xie, K.; Zhang, L. Line by line inscribed small period long period grating for wide range refractive index sensing. Opt. Communications 2022, 508, 127821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cheng, P.; Zhao, R.; Cai, J.; Shen, M.; Shu, X. Mode-locked fiber laser based on a small-period long-period fiber grating inscribed by femtosecond laser. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 2241–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tian, J.; Quan, M.; Yao, Y. Tunable Multiwavelength Er-doped fiber laser with a two stage lyot filter. IEEE photonics technology letters 2017, 29, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Jin, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Ma, X. All-fiber high-power spatiotemporal mode-locked laser based on multimode interference filtering. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 2909–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teran, M.A. C.; Gonzalez D., T.; Hernandez J. M., S.; Ayala J. M., E.; Ayona J. R., R.; Garcia J. C., H.; Garcia M. S., A.; Biancherri, M.; Toffanin, S.; Laguna R., R. Switchable multi-wavelength ytterbium-doped fiber laser based on a photonic crystal fiber Mach-Zehnder interferometer. Opt. Communications 2025, 577, 131400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Doerr, C. R.; Haus H., A.; Ippen E., P. ; Haus H. A.; Ippen E. P. Soliton fiber ring laser stabilization and tuning with a broad intracavity filter. IEEE Photonic technology letters 1994, 6, 697–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Shu, X.; Zhang, A.; Liu, W.; Zhang, L.; He, S.; Bennion, L. Implementation and characterization of Liquid-level sensor based on a long-period fiber grating Mach-Zehnder Interferometer. IEEE sensors journal 2011, 11, 2878–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L. V.; Hwang, D.; Moon, S.; Moon D., S.; Chung, Y.; Hwang, D.; Moon, S.; Moon, D.S.; Chung, Y. High temperature fiber sensor with high sensitivity based on core diameter mismatch. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 11369–11375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, B.H. All-fiber mach-zehnder type interferometers formed in photonic crystal fiber. Opt. Express 2007, 15, 5711–5720.

- Jung, Y.; Lee, S.; Lee, B. H.; Oh, K. Ultracompact in-line broadband Mach-Zehnder interferometer using a composite leaky hollow-optical-fiber waveguide. Opt. Lett. 2008, 33, 2934–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Yu, Y.; Xue, Y.; Chen, C.; Chen, Q.; Sun, H. Single S-tapered fiber Mach-Zehnder interferometers. Opt. Lett. 2011, 36, 4482–4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Lu, P.; Lao, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhang, J. Highly sensitive curvature sensor based on single-mode fiber using core-offset splicing. Opt. Laser Technol. 2014, 57, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Lee, S.; Ha, W.; Kim, D.; Shin, W.; Sohn, I.; Oh, K. Ultracompact intrinsic micro air-cavity fiber Mach-Zehnder interferometer. IEEE Photonics technology letters 2009, 21, 1027–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Cao, X. Ultrafast laser direct writing of material independent integrated nonlinear components based on NPE. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 15936–15945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiu, L. ,.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Pang, X.; Liu, Y.; Cao, X. Ultrafast laser direct writing of in-line polarizers based on nano-gratings. Opt. Lett. 2024, 49, 6880–6883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Xu, X.; Wu, J.; He, J.; Wang, Y.; Liao, C.; Wang, Y.; He, J. Femtosecond laser plane-by-plane inscription of ultra-short DBR fiber lasers for sensing applications. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 30326–30334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Fan, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, X.; Yu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Juodkazis, S.; Chen, Q.; Sun, H. Super-stealth dicing of transparent solids with nanometric precision. Nature Photonics 2024, 18, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Duan, T.; Wang, R.; Chen, F.; Qiao, X. Ultrahigh return loss LPFGs fabricated via femtosecond laser direct writing of ultrashort TFBGs. Opt. Lett. 2025, 50, 2053–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Wang, D.N.; Liu, S.; Lu, P. Fiber in-line Mach-Zehnder interferometer fabricated by femtosecond laser micromachining for refractive index measurement with high sensitivity. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2010, 27, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Shu, X.; Sugden, K. Ultra-compact all-in-fiber core Mach-Zehnder interferometer. Opt. Lett. 2017, 42, 4059–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Liu, H.; Shu, X. High-performance vector torsion sensor based on high polarization-dependent in-fiber Mach-Zehnder interferometer. Opt. Express, 2023, 31, 8844–8854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhao, R.; Xu, Z.; Miao, Q.; Shu, X.; Yu, B.; Lu, L.; Yu, Q. Femtosecond laser-inscribed in-fiber Mach-Zehnder interferometer for ultra-sensitive small-angle torsion measurement. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 181, 112058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).