Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- Population: adolescent and adult female gymnasts.

- Concept: evaluation of stress urinary incontinence in gymnasts.

- Context: to assess incontinence in a training environment, in a sports context.

2.2. Evidence Sources

2.3. Research Strategy

2.4. Evidence Selection

2.5. Analysis and Results Presentation

3. Results

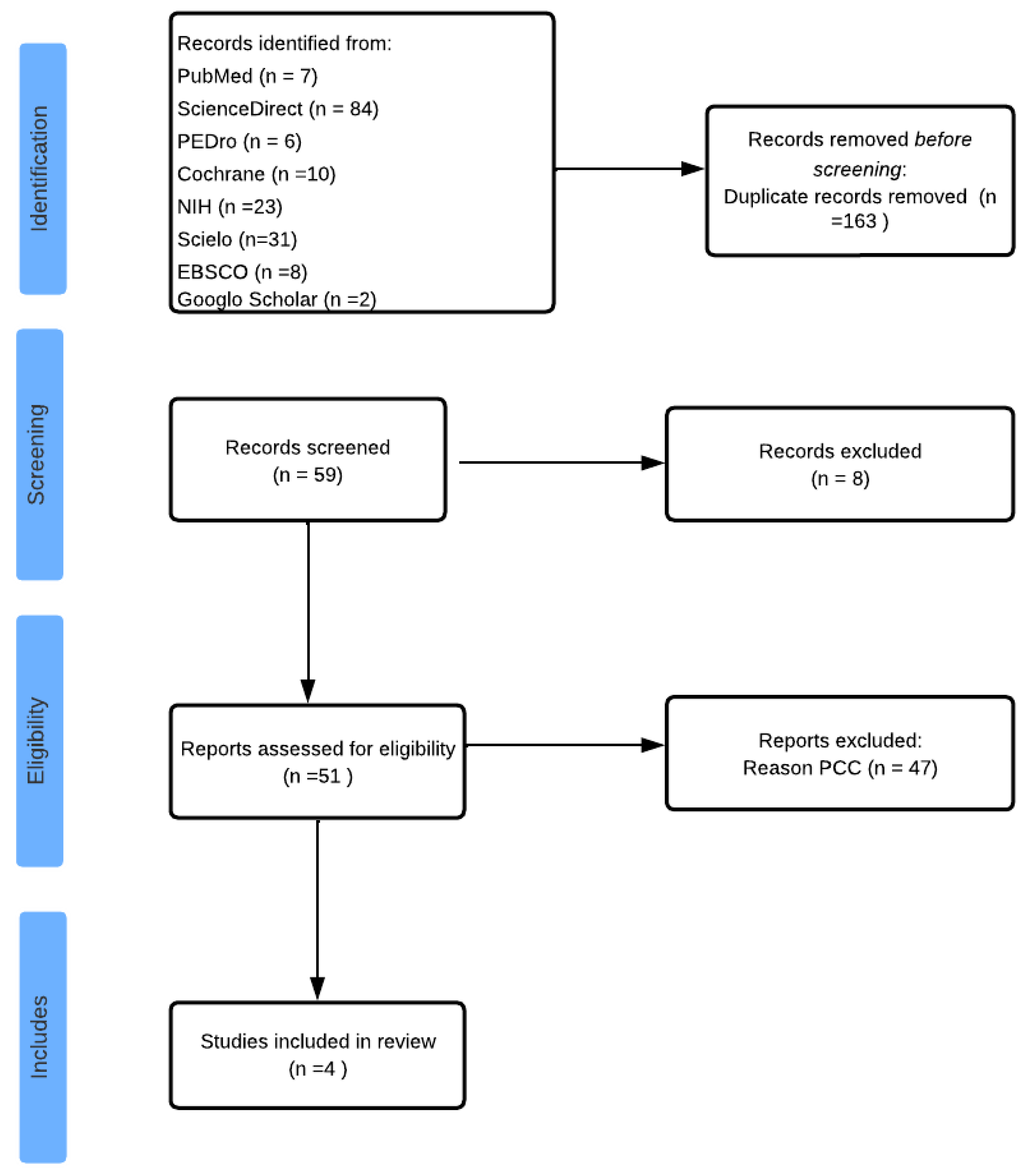

3.1. Selection of Evidence Sources

3.2. Types of Study

3.3. Participant characteristics

3.4. Intervention

3.5. Assessment tools

3.6. Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haylen, BT., De Ridder, D., Freeman, R., Swift, S., Berghmans, B., Lee, JH., Monga, A., Petri, E., Rizk, DEE., Sand, PK., & Schaer, GN. An international urogynecological association (IUGA)/international continence society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourology and Urodynamics 2011, 29(1): 4-20. [CrossRef]

- D’Ancona, CAL., Haylen, BT., Wein, AJ., Abranches-Monteiro, L., Arnold, EP., Goldman, H B., Hamid, R., Homma, Y., Marcelissen, T., Rademakers, K., Schizas, A., Singla, AK., Soto, I., Tse, V., De Wachter, S., Herschorn, S., & Dysfunction. The International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for adult male lower urinary tract and pelvic floor symptoms and dysfunction. Neurourology and Urodynamics 2019, 38(2): 433 477. [CrossRef]

- Dedicação, AC., Haddad, M., Saldanha, M., & Driusso, P. Comparação da qualidade de vida nos diferentes tipos de incontinência urinária feminina. Revista Brasileira De Fisioterapia 2009, 13(2): 116 122. [CrossRef]

- Aoki, Y., Brown, HE., Brubaker, L., Cornu, J., Daly, JO. & Cartwright, R. Urinary incontinence in women. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2017, 3(1): 17042. [CrossRef]

- Milsom, I., Altman, D., Cartwright, R., Lapitan, MC., Nelson, R., Sillén, U., & Tikkinen, K. Epidemiology of Urinary Incontinence (UI) and other Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS), Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP) and Anal Incontinence (AI). In: Incontinence: 5th International Consultation on Incontinence, Paris, P. Abrams, L. Cardozo, S. Khoury, & A. J. Wein (5th ed). 2013, ICUD-EAU, 15-107.

- Correia, S., Dinis, P., Rolo, F., & Lunet, N. Prevalence, treatment and known risk factors of urinary incontinence and overactive bladder in the non-institutionalized Portuguese population. International Urogynecology Journal 2009, 20(12): 1481-1489. [CrossRef]

- Preda, A. & Moreira, S. Incontinência Urinária de Esforço e Disfunção Sexual Feminina : O Papel da Reabilitação do Pavimento Pélvico. Acta Médica Portuguesa 2019, 32(11), 721-726. [CrossRef]

- Benício, CDAV., Luz, MHBA., De Oliveira Lopes, MV. & De Carvalho, NAR. Incontinência Urinária : Prevalência e Fatores de Risco em Mulheres em uma Unidade Básica de Saúde. Estima 2016, 14(4): 161-168. [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Lopes, MV., & Higa, R. Restrições causadas pela incontinência urinária à vida da mulher. Revista Da Escola De Enfermagem Da Usp 2006, 40(1): 34-41. [CrossRef]

- Abrams, P., Cardozo, L., Fall, M., Griffiths, D., Rosier, PF., Ulmsten, U., Van Kerrebroeck, P., Victor, A. & Wein, A. J. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function : Report from the standardisation sub-committee of the international continence society. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2002, 187(1): 116-126. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M., Barra, AA., Saltiel, F., Silva-Filho, AL., Da Fonseca, AMRM. & Figueiredo, EM. Urinary incontinence and other pelvic floor dysfunctions in female athletes in Brazil : A cross-sectional study. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2016, 26(9): 1109-1116. [CrossRef]

- Bø, K. Urinary Incontinence, Pelvic Floor Dysfunction, Exercise and Sport. Sports Medicine 2004, 34(7): 451-464. [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, I. & Shaw, JM. Physical activity and the pelvic floor. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2016, 214(2), 164-171. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, JM. & Nygaard, I. Role of chronic exercise on pelvic floor support and function. Current Opinion in Urology 2017, 27(3): 257-261. [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, I., DeLancey, JO., Arnsdorf, L., & Murphy, E. Exercise and incontinence. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics 1995, 33(4), 384. [CrossRef]

- Carls, C. The prevalence of stress urinary incontinence in high school and college-age female athletes in the midwest : implications for education and prevention. Urologic nursing 2007, 27(1): 21-24.

- Bø, K. & Borgen, JS. Prevalence of stress and urge urinary incontinence in elite athletes and controls. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 2001, 33(11): 1797-1802, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Thyssen, HH., Clevin, L., Olesen, SS. & Lose, G. Urinary Incontinence in Elite Female Athletes and Dancers. International Urogynecology Journal 2002, 13(1): 15-17, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, K., Larsson, TE. & Mattsson, E. Prevalence of stress incontinence in nulliparous elite trampolinists. Scan J Med Sci Sports 2002, 12(2): 106 110. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, CL., Srivastava, K., Ochuba, O., Ruo, SW., Alkayyali, T., Sandhu, JK., Waqar, A., Jain, A. & Poudel, S. Stress Urinary Incontinence Among Young Nulliparous Female Athletes. Cureus 2021, 13(9): e17986. [CrossRef]

- Tanno, AP. & Marcondes, FK. Estresse, ciclo reprodutivo e sensibilidade cardíaca às catecolaminas. Revista Brasileira De Ciencia Do Solo 2002, 38(3): 273-289. [CrossRef]

- Guezennec, C., Oliver, C., Lienhard, F., Seyfried, D., Huet, F. & Pesce, G. Hormonal and metabolic response to a pistol-shooting competition. Science & Sports 1992, 7(1): 27-32. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372(71). [CrossRef]

- Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Porritt K, Pilla B, Jordan Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis 2020. [CrossRef]

- Gram, MCD., & Bø, K. High level rhythmic gymnasts and urinary incontinence : Prevalence, risk factors, and influence on performance. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2020, 30(1): 159 165. [CrossRef]

- Skaug, KL., Engh, ME., Frawley, H. & Bø, K. Urinary and anal incontinence among female gymnasts and cheerleaders—bother and associated factors. A cross-sectional study. International Urogynecology Journal 2022, 33(4): 955-964. [CrossRef]

- Da Roza, T., Brandão, S., Mascarenhas, T., Jorge, RN. & Duarte, J. A. Volume of Training and the Ranking Level Are Associated With the Leakage of Urine in Young Female Trampolinists. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 2015, 25(3): 270 275. [CrossRef]

- Rockwood, T. H., Church, J. M., Fleshman, J. W., Kane, R. L., Mavrantonis, C., Thorson, A. G., Wexner, S. D., Bliss, R. N. D., & Lowry, A. C. Patient and surgeon ranking of the severity of symptoms associated with fecal incontinence. Diseases of The Colon & Rectum 1999, 42(12), 1525 1531. [CrossRef]

- Cotterill, N., Norton, C., Avery, K. N. L., Abrams, P., & Donovan, J. L. Psychometric Evaluation of a New Patient-Completed Questionnaire for Evaluating Anal Incontinence Symptoms and Impact on Quality of Life : The ICIQ-B. Diseases of The Colon & Rectum 2011, 54(10), 1235 1250. [CrossRef]

- De Maria, U. P., & Juzwiak, C. R. Cultural adaptation and validation of the low energy availability in females questionnaire (LEAF-Q). Bras Med Esporte 2021, 27(2). [CrossRef]

- De Souza, M. J., Nattiv, A., Joy, E. A., Misra, M., Williams, N. I., Mallinson, R. J., Gibbs, J. C., Olmsted, M. P., Goolsby, M., Matheson, G. O., & Panel, L. 2014 Female Athlete Triad Coalition Consensus Statement on Treatment and Return to Play of the Female Athlete Triad : 1st International Conference held in San Francisco, California, May 2012 and 2nd International Conference held in Indianapolis, Indiana, May 2013. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2014 48(4), 289. [CrossRef]

- Malek, S., Reinhold, E. J., & Pearce, G. The Beighton Score as a measure of generalised joint hypermobility. Rheumatology International 2021, 41(10), 1707-1716.

- Wiegel, M., Meston, C. M., & Rosen, R. C. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) : Cross-Validation and Development of Clinical Cutoff Scores. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 2005, 31(1), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Santos, KMD., Da Roza, T., Da Silva, LL., Wolpe, RE., Da Silva Honório, GJ., & Da Luz, SC. Female sexual function and urinary incontinence in nulliparous athletes : An exploratory study. Physical Therapy in Sport 2018, 33, 21-26. [CrossRef]

- Bø, K. Physiotherapy management of urinary incontinence in females. Journal of Physiotherapy 2020, 66(3): 147-154. [CrossRef]

- Dumoulin, C., Hay-Smith, J., & Mac Habée-Séguin, G. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. The Cochrane library 2014, 5: 1-94. [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women : management. NICE guideline 2019, No.123.

- Tamanini, JTN., Dambros, M., D’Ancona, CAL., Palma, P. & Netto, NR. Validação para o português do « International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire - Short Form » (ICIQ-SF). Revista De Saude Publica 2004, 38(3): 438-444. [CrossRef]

- Saboia, DM., Firmiano, MLV., De Castro Bezerra, K., Neto, JD., Oriá, MOB. & Vasconcelos, C TM. Impacto dos tipos de incontinência urinária na qualidade de vida de mulheres. Revista Da Escola De Enfermagem Da Usp 2017, 51(0): e03266. [CrossRef]

- Avery, KNL., Donovan, JL., Peters, TJ., Shaw, C., Gotoh, M., & Abrams, P. ICIQ : A brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourology and Urodynamics 2004, 23(4): 322-330. [CrossRef]

- Bø, K., & Nygaard, I. Is Physical Activity Good or Bad for the Female Pelvic Floor ? A Narrative Review. Sports Medicine 2020, 50(3): 471-484. [CrossRef]

- Seegmiller, JG. & McCaw, ST. Ground Reaction Forces Among Gymnasts and Recreational Athletes in Drop Landings. J Athl Train 2003, 38 (4): 311 314.

| Database | Search Strategy | Filters used |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (“woman” OR “female” OR “athlete”) AND (“gymnastic” OR “trampoline” OR “acrobatic” OR “high impact sport”) AND (“urinary incontinence” OR “stress urinary incontinence” OR “pelvic floor disorders” OR “loss of urine” OR “urine leakage”) AND (“prevalence” OR “treatment” OR “knowledge” OR “impact” OR “quality of life” OR “prevention”) | Published between 2012 and 2023 Full text available Study type: journal article, clinical trial, randomised controlled trial, books and documents Language: English, Portuguese Age: adolescents (13–18 years), young adults (19–24 years), adults (19–44 years) Sex: female |

| Cochrane | (“gymnastic” OR "trampolim" OR "acrobatic" OR "high impact sport") AND (“urinary incontinence” OR “stress urinary incontinence” OR “pelvic floor disorders”) | Published between 2012 and 2023 Language: English Publication type: Clinical trials |

| Science Direct | (“gymnastic” OR "trampolim" OR "acrobatic" OR "high impact sport") AND (“urinary incontinence” OR “stress urinary incontinence” OR “pelvic floor disorders”). | Published between 2012 and 2023 Publication type: research articles, book chapters Access: free access, open archive |

| Scielo | (“gymnastic” OR "trampolim" OR "acrobatic" OR "high impact sport") AND (“urinary incontinence” OR “stress urinary incontinence” OR “pelvic floor disorders”) | Published between 2012 and 2023 Language: English, Portuguese Type of literature: articles |

| EBSCO | (“gymnastic” OR "trampolim" OR "acrobatic" OR "high impact sport") AND (“urinary incontinence” OR “stress urinary incontinence” OR “pelvic floor disorders”) | Published between 2012 and 2023 References available Type of publication: academic journal articles, reports, books |

| PEDro | “incontinence. Subdisciplina: “sports” |

Published from 2012 onwards Method: clinical trial |

| NIH | “urinary incontinence”. Outros termos: “sport” |

Articles published from 2012 onwards Study type: clinical trial, observational study Status: completed and closed Expanded access: available Study with results Age: children and adults Sex: female |

| Authors /Year |

Study | Objectives | Participants | Assessment tools |

Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almeida et al. (2016) |

Cross-sectional study | To investigate the occurrence of pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) symptoms among athletes and non-athletes. To investigate the influence of sport on the occurrence and severity of urinary dysfunction. |

n = 163 Athletes (n=67): artistic gymnastics and trampoline (n=9) Non-athletes (n=96) 15-29 years BMI athletes: 21.7 (± 2.6) BMI non-athletes: 20.9 (± 3.9) Nulliparous IU (gymnasts) : 88.9% IUE (gymnasts): 87.5% |

ICIQ-UI-SF FISI Criteria Rome III FSFI ICIQ-VS |

Pelvic floor dysfunctions Influence of modality Impact on quality of life Attitude towards UI |

| Da Roza et al. (2015) |

Cohort study | To investigate the association between UI severity and training volume and athletic performance in young female nulliparous trampolinists. | n = 22 Trampolinists/ National level 14-25 years BMI: 20.4 (± 1.3) Nulliparous SUI: 72.7% |

ICIQ-UI-SF |

Prevalence of pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) Association between UI severity and training volume Impact on quality of life and athletic performance |

| Gram et Bø, (2020) |

Cross-sectional study | To investigate the prevalence and risk factors of UI in rhythmic gymnasts and the impact of UI on sports performance. Evaluate MPP knowledge and MPP training. |

n = 107 Rhythmic gymnastics International level 12-21 years BMI: 18.5 (± 5.3) Nulliparous 65.4% menarche UI: 31.8% SUI: 61.8% UI: 8.8% UI: 17.6% Other UI: 11.8% |

ICIQ-UI-SF "Triad-specific self- report questionnaire" LEAF-SF Beighton score |

UI prevalence Prevalence of type of UI Impact of UI on athletic performance Knowledge about MPP and its training |

| Skaug et al., (2022) |

Cross-sectional study | To investigate the prevalence and risk factors of UI and anal incontinence (AI) in high-performance female artistic gymnasts (GA), team gymnasts (GE) and female cheerleaders To investigate the impact of UI/IA on sports performance To assess the athletes' knowledge of MPP. |

n = 319 Artistic gymnastics (n=68), Team gymnastics (n=116),C Cheerleading (n=135) National and international level 12-36 years BMI: 21.7 (± 2. 7) Nulliparous 92.2% menarcas IU: GA 70.6%, GE 83.6% IUE: GA 70.6%, GE 80.2% IUU: GA 8.8%, GE 12.9% |

ICIQ-UI-SF ICIQ-B LEAF-Q |

Prevalence of UI and AI Prevalence of type of UI Impact on athletic performance Knowledge of UI |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).