1. Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI), defined as any “complaint of involuntary loss of urine” [

1], is a widespread condition among women worldwide. The prevalence of UI rises with age and is reported to affect 58–84% of women, with most of studies reporting a prevalence of any UI in the range of 25%–45% [

2,

3,

4]. The high variability in the reported prevalence of UI can be attributed to cultural differences in the perception of UI, variations in study methodologies, and inconsistencies in its definition [

3,

5]. Despite its high prevalence, UI remains underdiagnosed since up to half of the affected women may refrain from reporting it to their healthcare provider due to embarrassment or the misconception that UI is a natural part of aging [

6].

Incontinence types can be classified according to its pathophysiological mechanism as: a) stress urinary incontinence (SUI) when the urethral closure mechanism functioning is poor and the anatomic urethral support is lost, b) urge urinary incontinence (UUI) when bladder detrusor muscle involuntary contracts during the during the filling phase of the micturition cycle, and c) mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) when there is the concomitant presence of defective urethral closure or support mechanisms and of detrusor overactivity [

6,

7]. From a clinical perspective, SUI is defined as the complaint of involuntary urine leakage of urine during activities that increase abdominal pressure (such as exercise, sneezing, or coughing), UUI is defined as the complaint of involuntary urine leakage accompanied by or immediately preceded by a sudden, compelling urge to urinate that is difficult to postpone, while MUI is characterized by the presence of both SUI and UUI symptoms [

8].

UI negatively affects the quality of life (QoL) affecting different areas of the subjects’ life including, social, work, psychological and sexual wellbeing [

9,

10]. A detrimental impact of UI has been observed on sexual function, affecting 26% of women with SUI and 43% of women with UUI [

11]. The impact of UI QoL is not yet fully understood, highlighting the need for more comprehensive research and targeted investigation to fully capture its multifaceted consequences [

10].

UI not only affects the QoL of the individual afflicted but is also a significant economic burden for the healthcare services [

12]. The annual cost of UI in Sweden, for example, has been reported to account for approximately 2% of the total health-care budget [

13]. Recent international research on the economic burden of urinary incontinence estimates that the cost of continence care in Europe will reach € 69.1 billion in 2023. Without proactive measures to improve continence health, this financial burden is projected to increase by 25%, reaching € 86.7 billion by 2030 [

14,

15,

16]. Moreover, toileting assistance associated with UI imposes a significant substantial additional burden on family caregivers and nursing facilities staff [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

Our pilot study aimed to assess the efficacy of a commercially available food supplement (Dermoxen

® PelviPlus worldwide and Dermoxen

® Urocollagen in the Chinese market, Ekuberg Pharma, Carpignano Salentino, Italy) when used in conjunction with regular pelvic floor muscle exercises (PFMT) to improve the UI symptoms and the QoL in women with SUI, UUI or MUI. This food supplement was specifically formulated to support the pelvic floor by collagen and to help the normal muscle functioning by magnesium. A study conducted by Gong et al. reported collagen abnormalities linked to an imbalance between matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) in women with weakened pelvic support tissues [

22]. Similarly, research by Chen et al. reported a 60% reduction in total collagen content per milligram of protein in women with SUI compared to controls [

23]. These findings suggest that SUI may be associated with increased MMP-mediated collagen degradation within the extracellular matrix of pelvic floor support tissues, resulting in insufficient support for the bladder neck and urethra [

24,

25]. Magnesium was demonstrated to be effective in improving detrusor instability or sensory urgency in women [

26]. The food supplement contained also ingredients having beneficial effects in preventing urinary tract infections (cranberries and horsetail extracts), in muscle strength (Vitamin D), and in reducing the degradation of bladder structure due to lack of estrogens (

Cimicifuga racemosa extract) [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trial Design

This single-center randomized (1:1 ratio), double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted over a 6-week follow-up period at the Nutratech S.r.l. facilities (Rende, CS, Italy) between June and September 2024. It consisted of a screening visit, a baseline visit (W0) and a follow-up (W6) visit after 6 weeks of product use. Eligible subjects were enrolled, at baseline by a board-certified gynecologist and randomized to receive the active or the placebo product. After the baseline visit subjects received detailed instruction and training on pelvic floor muscle exercises by a physiotherapist (

Figure S1).

The trial protocol (NT0000653/24 vers. 01 by 29/05/2024) was approved on 13 June 2024 (EC ref. no 2024/04) by and independent Ethics Committee (“Comitato Etico Indipendente per le Indagini Cliniche Non Farmacologiche”, Genova, Italy). All study procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were informed about the risks and benefits of the trial. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

2.2. Participants

Eligible participants were healthy Caucasian women aged 45 to 70 years claiming stress and/or urge urinary incontinence (UI). Before inclusion in the trial the diagnosis of stress or urge UI was confirmed by a board-certified gynecologist based on clinical anamnesis and the answers to the Questionnaire for Urinary Incontinence Diagnosis (QUID,

Table S2). The cut-off value was set at ≥ 4 for SUI and ≥ 6 for UUI [

36]. Exclusion criteria included a positive medical history of pathologies (acute, chronic, or progressive) or pharmacological treatments (i.e. alpha-adrenergic blockers/stimulants, anticholinergics, calcium channel blockers, psychoactive drugs, misoprostol, opioids, hormone replacement therapy, diuretics) that could potentially interfere with the test product; simultaneous participation in other clinical trials; participation in a similar trial without an adequate washout period; food intolerance or food allergies (including allergies to ingredients of the test product); concomitant use of food supplements, topical products or procedures to treat UI; prior use of UI-active products or procedures without an adequate washout period; history of drug, alcohol, or substance abuse; nutrition and eating disorders (e.g. bulimia, psychogenic eating disorders, etc.); pregnant or breastfeeding women; and absence of adequate contraceptive measures in women of childbearing age.

2.3. Intervention, Randomization, and Compliance with Treatment

After the enrolment subjects were assigned to receive the active or the placebo products in a 1:1 ratio. The active arm (DXP) received (daily) 1 stick pack of a commercially available food supplement (Dermoxen® PelviPlus worldwide and Dermoxen® Urocollagen in the chinese market, Ekuberg Pharma, Carpignano Salentino, Italy) containing isomalt, Actaea racemosa L. rhizome dry extract (titrated to 2.5% saponins), vitamin D3 (100.000 IU/G cholecalciferol), tribasic magnesium citrate, hydrolyzed marine collagen, creatine monohydrate, Equisetum arvense L. herb dry extract (titrated to 2.0% in silica), Vaccinium macrocarpon Aiton fruit dry extract (titrated to 10.0% in proanthocyanidins), citric acid (E330), lemon flavoring, sucralose, silicon dioxide. The placebo arm (PLA) received (daily) 1 stick pack having the same appearance of the active product and containing isomalt, citric acid, lemon flavoring, sucralose, silicon dioxide.

A restricted randomization list was generated by PASS 11 (version 11.0.8, PASS, LLC, Kaysville, UT, USA) using the “Efron’s biased coin” algorithm. Participants received the food supplement in sealed boxes, each labeled uniquely coded to maintain blinding. The randomization list was securely stored in sequentially numbered, sealed, and opaque envelopes, ensuring that both the investigator and the participants remained unaware of the product assignment.

Participants were instructed to report any adverse events throughout the study. Compliance with the treatment was determined by counting and recording the unused stick packs at the end of the 6-week treatment period, with a compliance threshold defined as ≥ 80%. Participants with compliance below 80% were excluded from the intention-to-treat (ITT) population due to poor adherence to the treatment regimen.

2.4. Primary and Secondary Endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint was the improvement in UI symptoms from baseline to 6 weeks, as assessed by the QUID questionnaire and the gynecologist assessment. Additional analysis was done on participants who demonstrated an improvement in their QUID scores. Any adverse event was also assessed as a primary outcome.

The secondary endpoints of the trial were assessing improvements in participants' QoL and confirming product tolerability.

2.5. Outcomes

The Questionnaire for Urinary Incontinence Diagnosis (QUID) [

36] was used to distinguish SUI and UUI and to follow the improvement of UI symptoms over time. The QUID is a self-administered, 6-item questionnaire for UI symptoms, proven to be reliable and valid when compared to standard clinical evaluations in outpatient urogynecology settings [

37]. The first three items of the questionnaire address symptoms of SUI, while the remaining three focus on UUI symptoms (

Table S1). Possible answers to each item are six frequency-based options (from “none of the time” to “all of the time”) scored on a 6 points scale (from 0 to 5). Scores are calculated additively, yielding separate Stress and Urge scores, each ranging from 0 to 15 points.

At the end of the treatment period, the gynecologist assessed the product's efficacy using a verbal rating scale to address a question on treatment effectiveness (“Was the treatment effective?”). The scoring system was based on a verbal rating scale (VRS) as follows: 1. No, completely disagree, 2. No, disagree, 3. Yes, agree, and 4. Yes, completely agree.

The QoL questionnaire consisted of 10 items focused on the participant perception of the UI discomforts in the last two weeks (

Table S3). Answers were on a 11-points numerical rating scale (NRS) from 0 (“not at all”) to 10 (“maximum discomfort”).

2.6. Statistics

Data normality was checked by Shapiro Wilk-W test. Since all the data were not normally distributed, non-parametric tests were used. The Wilcoxon test was employed to evaluate intragroup differences compared to baseline, while the Mann-Whitney U test was used to assess intergroup variations between DXP and PLA at week 6 (W6). All statistical analyses were two-sided with a significance level set at 5% (p < 0.05) and were performed using Rstudio 2024 (version 2024.4.1.748; Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA). The levels of significance were denoted as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1. Subjects Characteristics, Compliance with Treatment, and Tolerability

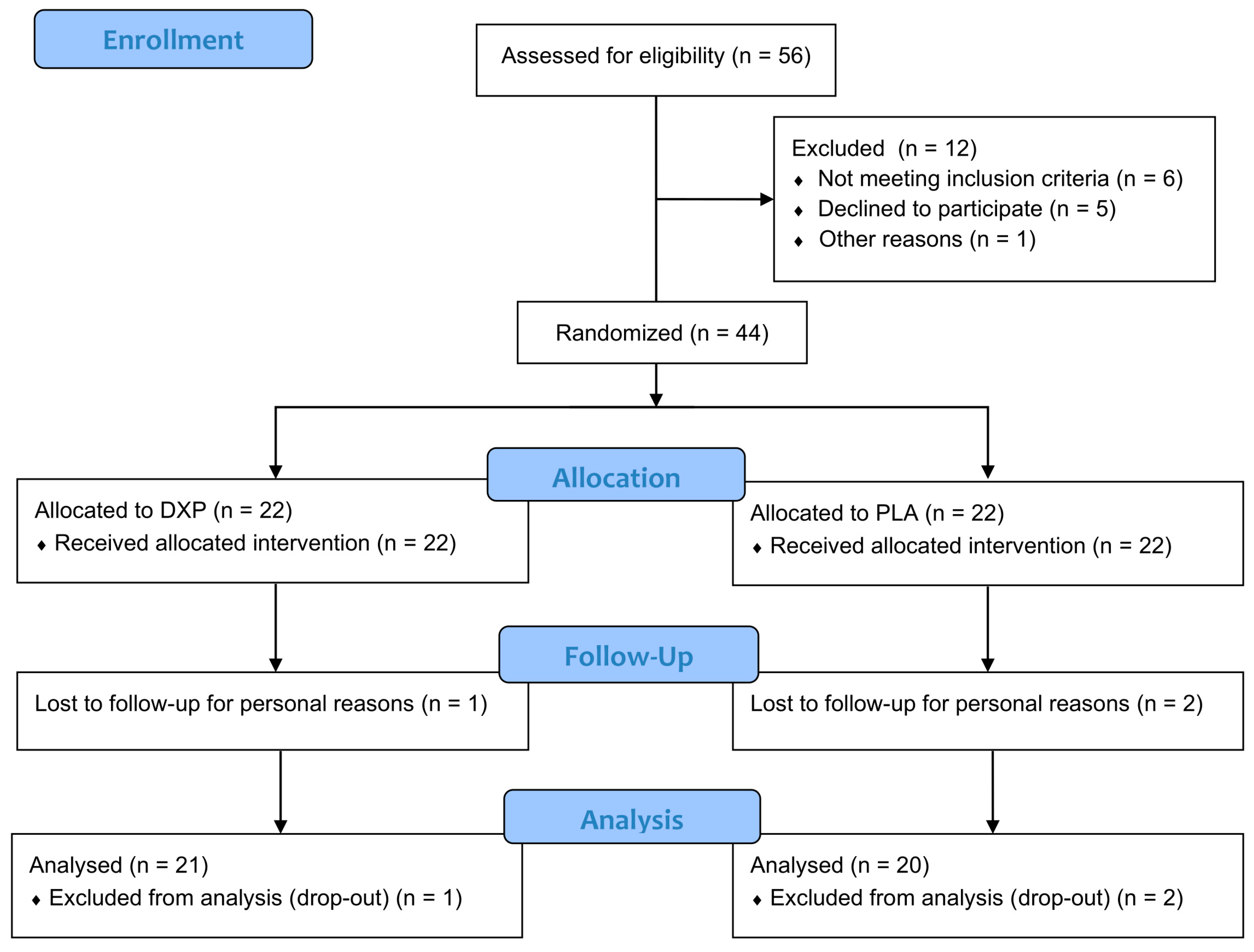

The study screened a total of 56 subjects (n = 56), with 12 excluded for the following reasons: 6 failed to meet the inclusion criteria, 5 declined participation, and 1 initiated pharmacological therapy. Forty-four subjects (n = 44) with SUI, UUI, or MUI were successfully randomized into two treatment groups (DXP or PLA), with 22 subjects in each group. A total of 41 subjects completed the study (per-protocol population). One subject in the DXP group and 2 subjects in the PLA group withdrew from the study for personal reasons not related to product use. The participants flow chart is reported in

Figure 1.

The mean age was 58.6 ± 1.7 in the DXP group and 53.7 ± 1.3 in the PLA group. The distribution of subjects with SUI, UUI, or MUI was balanced across the treatment groups. Additional demographic and baseline data are provided in

Table 1.

The compliance with treatment was above 95% for both groups (DPX = 97 ± 1%, range 83-100%; PLA = 98 ± 1%, range 90-100%).

3.2. Primary Outcomes

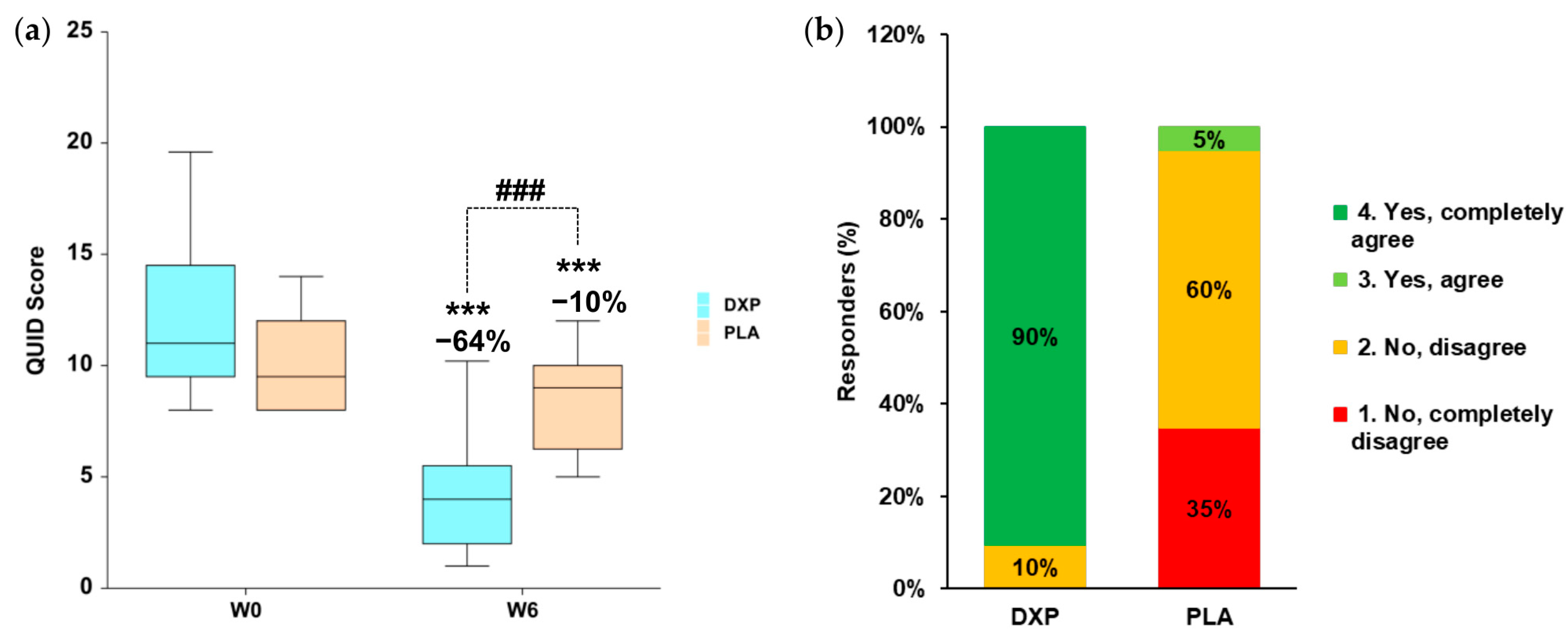

At baseline, the QUID total score was 11 (IQR 10-14) in the DPX group and 10 (IQR 8-12) in the PLA group. After 6 weeks of treatment, the QUID total score, in the active group was statistically significant (

p < 0.001) reduced by 64% (

Figure 2a). In the placebo treatment arm, the QUID score showed a slight reduction of 10%, which was statistically significant (

p < 0.001). The variation in QUID scores at week 6 (W6) between the DXP and PLA groups was statistically significant (

p < 0.001). Interestingly, a reduction in the QUID score corresponded to a negative diagnosis of UI in 76% (n = 16) of DXP-treated subjects, compared to only 25% (n = 5) of PLA-treated subjects.

The efficacy of the DXP treatment was positively evaluated by the gynecologist in 90.5% of participants, compared to only 5% in the PLA group (

Figure 2b). The global scoring between the DXP (median 4 “Yes, completely agree”; IQR 4-4) and the PLA (median 2 “No, disagree; IQR 1-2) treatment was statistically significant (

p < 0.001).

3.3. Secondary Outcomes

After 6 weeks of treatment, the quality of life in the DXP group improved by 76% (

Table 2), while no change was observed in the PLA group.

The improvement of QoL was associated with a reduction of the UI-related discomforts having a negative impact on the social functioning, the daily activities, and the mood of the affected subjects. In the PLA group, performing only PFMT exercises had no effect on QoL. At W6, the QoL scores for each item were statistically significantly different between the DXP and PLA treatment groups (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

The economic burden of urinary incontinence on healthcare services and its impact on family caregivers have been increasing in recent years, a trend exacerbated by an aging society [

14]. In the “integrated care for older people (ICOPE) guidelines”, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified urinary incontinence (UI) as a priority issue, recognizing its detrimental effects on the quality of life of older adults, their overall health status, levels of depression, and need for care [

38]. Non-pharmacological treatments are the most effective and safe approach to reduce the economic burden of urinary incontinence (UI) on healthcare systems, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, while also minimizing the risk of caregiver strain and burden [

38,

39].

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT), first described by the American gynecologist Kegel, is the first-line treatment for UI [

40]. However, several studies have reported that the efficacy of intensive and frequent PFMT practice supervised by qualified personnel rates from 29% to 59% and lasting for at least 3 months, as recommended by European Association of Urology (EAU) [

41,

42,

43,

44]. A systematic review by Riemsma et al. also found that the percentage of responders to PFMT varies depending on the subtype of UI, with SUI subjects showing the highest response rate (58.8% of responders) and UUI subjects the lowest (17% of responders) after 12 months of supervised PFMT [

41].

In the scientific literature there is increasing evidence of the role of food supplements in maintaining general health and in reducing the risk factor for a disease [

45]. However, the number of studies evaluating the relationship between food supplements, PFMT, and improvements in urinary incontinence (UI) is limited [

46]. To address this gap, we decided to explore the impact of food supplementation combined with pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) exercises on managing urinary incontinence (UI) symptoms. The key ingredients of the tested food supplement included collagen, aimed at counteracting the natural collagen degradation associated with aging, and magnesium, intended to alleviate detrusor instability and sensory urgency [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. The product formula also incorporated ingredients with beneficial effects on urinary and pelvic health, including cranberries and horsetail extracts for preventing urinary tract infections, Vitamin D for muscle strengthening, and

Cimicifuga racemosa extract to mitigate bladder structure degradation associated with estrogen deficiency.

Our findings clearly demonstrated the efficacy of food supplementation in increasing the percentage of responders (i.e. subjects with a negative diagnosis for UI) to PFMT treatment from 25% to 76% and in reducing UI-related discomforts. Interestingly the rate of improvement of PFMT that we observed is comparable with the rate of improvement reported in the literature [

43,

44]. The active product also proved to be effective in improving quality of life (QoL), demonstrating a significant reduction in discomforts related to social functioning (−75%), daily activities at home (−100%) and outdoors (−75%), as well as mood disturbances (−75%) of the affected subjects. This positive effect is an important step toward fostering age-friendly conditions (alignment of life span with health span) that promote the independence of elderly individuals, helping them maintain autonomy and avoid feeling like a burden to society.

The strength of this study is its study design (randomized clinical trial), the blind allocation to treatments, the high compliance with treatment (> 95%), and the positive results obtained in only 6 weeks. One of the main limitations of the study is the relatively small sample size that does not allow for robust subanalysis of the results obtained in each of the UI subtypes.

5. Conclusions

Our results clearly demonstrate the efficacy of oral supplementation with collagen and magnesium combined with PFMT in improving the UI-associated discomforts and the quality of life of the affected subjects.

The putative mechanism of action underlying our results may involve a positive effect on the pelvic floor muscles, enhanced support for the pelvic floor tissues, and improved regulation of detrusor instability or sensory urgency.

Based on our findings we can conclude that daily supplementation with Dermoxen® PelviPlus or Dermoxen® Urocollagen combined with pelvic floor strengthening can be a successful strategy to better urinary control after only 6 weeks of treatment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Instructions for performing Kegel exercises to strengthen pelvic floor muscles; Table S1: Template for the Questionnaire on Urinary Incontinence Diagnosis (QUID); Table S1: Template for the Quality of Life (QoL) Questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.N., C.S., E.D.C., and D.C.; methodology, F.A. and E.D.A.; validation, V.N., R.V., and M.M.; formal analysis, R.V., E.D.A. and V.N.; investigation, M.M.; resources, D.C. and F.A.; data curation, R.V. and V.N.; writing—original draft preparation, V.N.; writing—review and editing, V.N.; visualization, V.N.; supervision, F.A.; project administration, F.A.; funding acquisition, G.P.

Funding

This research was funded by Ekuberg Pharma. (Carpignano Salentino, Italy), grant number NT0000653/24. The APC was funded by EKUBERG pharma s.u.r.l. (Carpignano Salentino, Italy).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the and independent Ethics Committee (“Comitato Etico Indipendente per le Indagini Cliniche Non Farmacologiche”, Genova, Italy) on 13 June 2024 (EC ref. no. 2024/04).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. However, the data are not publicly available as they are the property of the study sponsor (EKUBERG pharma s.u.r.l., Carpignano Salentino, Italy).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the staff of Nutratech and Complife Italia for their invaluable contributions to the study, including subject recruitment, and for their professionalism and unwavering support throughout the study's development.

Conflicts of Interest

D.C., C.S. and E.D.C. are employed full-time at Ekuberg Pharma. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UI |

Urinary incontinence |

| PFMT |

Pelvic floor muscle training |

| SUI |

Stress urinary incontinence |

| UUI |

Urge urinary incontinence |

| MUI |

Mixed urinary incontinence |

| QUID |

Questionnaire for urinary incontinence diagnosis |

| DPX |

Active product |

| PLA |

Placebo product |

| QoL |

Quality of life |

| MMP |

Matrix metalloproteinases |

| TIMP |

Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases |

| VRS |

Verbal rating scale |

| NRS |

Numerical rating scale |

| ICOPE |

Integrated care for older people |

| WHO |

World health organization |

| EAU |

European association of Urology |

| EC |

Ethical committee |

References

- Haylen, B. T.; de Ridder, D.; Freeman, R. M.; Swift, S. E.; Berghmans, B.; Lee, J.; Monga, A.; Petri, E.; Rizk, D. E.; Sand, P. K.; Schaer, G. N.; International Urogynecological Association; International Continence Society. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) Joint Report on the Terminology for Female Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn 2010, 29 (1), 4–20. [CrossRef]

- Altman, D.; Cartwright, R.; Lapitan, M. C.; Milsom, I.; Nelson, R.; Sjöström, S.; Tikkinen, K. A. O. Epidemiology of Urinary Incontinence (UI) and Other Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS), Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP) and Anal Incontinence (AI). In Incontinence; Abrams, P., Cardozo, L., Wagg, A., Wein, A. J., Eds.; International Continence Society: Bristol, 2017; pp 1–141.

- Milsom, I.; Gyhagen, M. The Prevalence of Urinary Incontinence. Climacteric 2019, 22 (3), 217–222. [CrossRef]

- Mostafaei, H.; Sadeghi-Bazargani, H.; Hajebrahimi, S.; Salehi-Pourmehr, H.; Ghojazadeh, M.; Onur, R.; Al Mousa, R. T.; Oelke, M. Prevalence of Female Urinary Incontinence in the Developing World: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis-A Report from the Developing World Committee of the International Continence Society and Iranian Research Center for Evidence Based Medicine. Neurourol Urodyn 2020, 39 (4), 1063–1086. [CrossRef]

- Milsom, I.; Coyne, K. S.; Nicholson, S.; Kvasz, M.; Chen, C.-I.; Wein, A. J. Global Prevalence and Economic Burden of Urgency Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review. European Urology 2014, 65 (1), 79–95. [CrossRef]

- Russo, E.; Caretto, M.; Giannini, A.; Bitzer, J.; Cano, A.; Ceausu, I.; Chedraui, P.; Durmusoglu, F.; Erkkola, R.; Goulis, D. G.; Kiesel, L.; Lambrinoudaki, I.; Hirschberg, A. L.; Lopes, P.; Pines, A.; Rees, M.; Trotsenburg, M. van; Simoncini, T. Management of Urinary Incontinence in Postmenopausal Women: An EMAS Clinical Guide. Maturitas 2021, 143, 223–230. [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, P. L. Differentiating Stress Urinary Incontinence from Urge Urinary Incontinence. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2004, 86 Suppl 1, S17-24. [CrossRef]

- Gacci, M.; Sakalis, V. I.; Karavitakis, M.; Cornu, J.-N.; Gratzke, C.; Herrmann, T. R. W.; Kyriazis, I.; Malde, S.; Mamoulakis, C.; Rieken, M.; Schouten, N.; Smith, E. J.; Speakman, M. J.; Tikkinen, K. A. O.; Gravas, S. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Male Urinary Incontinence. European Urology 2022, 82 (4), 387–398. [CrossRef]

- Sazonova, N. A.; Kiseleva, M. G.; Gadzhieva, Z. K.; Gvozdev, M. Y. [Urinary incontinence in women and its impact on quality of life]. Urologiia 2022, No. 2, 136–139.

- Frigerio, M.; Barba, M.; Cola, A.; Braga, A.; Celardo, A.; Munno, G. M.; Schettino, M. T.; Vagnetti, P.; De Simone, F.; Di Lucia, A.; Grassini, G.; Torella, M. Quality of Life, Psychological Wellbeing, and Sexuality in Women with Urinary Incontinence-Where Are We Now: A Narrative Review. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022, 58 (4), 525. [CrossRef]

- Walters, M. D.; Taylor, S.; Schoenfeld, L. S. Psychosexual Study of Women with Detrusor Instability. Obstet Gynecol 1990, 75 (1), 22–26.

- Wagner T, Moore K, Subak L, De Wachter S, Dudding T. Economics of urinary and faecal incontinence, and prolapse. In:Abrams P, Cardozo L, Wagg A, Wein A, eds. Incontinence. 6th ed. Paris: Health Publications Ltd; 2016:17–24.

- Ekelund, P.; Grimby, A.; Milsom, I. Urinary Incontinence. Social and Financial Costs High. BMJ 1993, 306 (6888), 1344. [CrossRef]

- Uroweb. The annual economic burden of urinary incontinence could reach €87 billion in 2030 if no action is taken. Available online: https://uroweb.org/press-releases/the-annual-economic-burden-of-urinary-incontinence-could-reach-87-billion-in-2030-if-no-action-is-taken (accessed 2025-01-02).

- Morrison, A.; Levy, R. Fraction of Nursing Home Admissions Attributable to Urinary Incontinence. Value Health 2006, 9 (4), 272–274. [CrossRef]

- Coyne, K. S.; Wein, A.; Nicholson, S.; Kvasz, M.; Chen, C.-I.; Milsom, I. Economic Burden of Urgency Urinary Incontinence in the United States: A Systematic Review. J Manag Care Pharm 2014, 20 (2), 130–140. [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.; Leslie, S. W.; Riggs, J. Mixed Urinary Incontinence. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024.

- Morrison, A.; Levy, R. Fraction of Nursing Home Admissions Attributable to Urinary Incontinence. Value Health 2006, 9 (4), 272–274. [CrossRef]

- Bektas Akpinar, N.; Unal, N.; Akpinar, C. Urinary Incontinence in Older Adults: Impact on Caregiver Burden. J Gerontol Nurs 2023, 49 (4), 39–46. [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, M.; Matsukawa, Y.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Funahashi, Y.; Kato, M.; Hattori, R. Impact of Urinary Incontinence on the Psychological Burden of Family Caregivers. Neurourol Urodyn 2009, 28 (6), 492–496. [CrossRef]

- Schumpf, L. F.; Theill, N.; Scheiner, D. A.; Fink, D.; Riese, F.; Betschart, C. Urinary Incontinence and Its Association with Functional Physical and Cognitive Health among Female Nursing Home Residents in Switzerland. BMC Geriatr 2017, 17 (1), 17. [CrossRef]

- Gong, R.; Xia, Z. Collagen Changes in Pelvic Support Tissues in Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2019, 234, 185–189. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. H.; Wen, Y.; Li, H.; Polan, M. L. Collagen Metabolism and Turnover in Women with Stress Urinary Incontinence and Pelvic Prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2002, 13 (2), 80–87; discussion 87. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, M.; Qu, Z.; Ruan, S.; Chen, B.; Ran, J.; Shu, W.; Chen, Y.; Hou, W. Effect of Electroacupuncture on the Degradation of Collagen in Pelvic Floor Supporting Tissue of Stress Urinary Incontinence Rats. Int Urogynecol J 2022, 33 (8), 2233–2240. [CrossRef]

- Patel, P. D.; Amrute, K. V.; Badlani, G. H. Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Stress Urinary Incontinence: A Review of Etiological Factors. Indian Journal of Urology 2007, 23 (2), 135. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.; Groutz, A.; Ascher-Landsberg, J.; Lessing, J. B.; David, M. P.; Razz, O. Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Magnesium Hydroxide for Treatment of Sensory Urgency and Detrusor Instability: Preliminary Results. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998, 105 (6), 667–669. [CrossRef]

- Jeitler, M.; Michalsen, A.; Schwiertz, A.; Kessler, C. S.; Koppold-Liebscher, D.; Grasme, J.; Kandil, F. I.; Steckhan, N. Effects of a Supplement Containing a Cranberry Extract on Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections and Intestinal Microbiota: A Prospective, Uncontrolled Exploratory Study. J Integr Complement Med 2022, 28 (5), 399–406. [CrossRef]

- Jepson, R. G.; Mihaljevic, L.; Craig, J. Cranberries for Preventing Urinary Tract Infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004, No. 2, CD001321. [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, D.; Jardim, T.; Araújo, Y.; Arantes, A.; de Sousa, A.; Barroso, W.; Sousa, A.; da Cunha, L.; Cirilo, H.; Bara, M.; Jardim, P. Equisetum Arvense: New Evidences Supports Medical Use in Daily Clinic. Pharmacognosy Reviews 2019, 13 (26), 50–58. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.; Groutz, A.; Ascher-Landsberg, J.; Lessing, J. B.; David, M. P.; Razz, O. Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Magnesium Hydroxide for Treatment of Sensory Urgency and Detrusor Instability: Preliminary Results. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998, 105 (6), 667–669. [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, C. P.; Tangpricha, V.; Motahar-Ford, N.; Goode, P. S.; Burgio, K. L.; Allman, R. M.; Daigle, S. G.; Redden, D. T.; Markland, A. D. Vitamin D and Incident Urinary Incontinence in Older Adults. Eur J Clin Nutr 2016, 70 (9), 987–989. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J. B.; Kakkad, V.; Kumar, S.; Roy, K. K. Cross-Sectional Study on Vitamin D Levels in Stress Urinary Incontinence in Women in a Tertiary Referral Center in India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2019, 23 (6), 623–627. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. B.; Perdawood, D.; Abdulrahman, R.; Al Farraj, D. A.; Alkubaisi, N. A. Vitamin D Deficiency as a Risk Factor for Urinary Tract Infection in Women at Reproductive Age. Saudi J Biol Sci 2020, 27 (11), 2942–2947. [CrossRef]

- Raz, R. Postmenopausal Women with Recurrent UTI. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2001, 17 (4), 269–271. [CrossRef]

- El-Din, W. A. N. Role of Tibolone and Cimicifuga Racemosa on Urinary Bladder Alterations in Surgically Ovariectomized Adult Female Rats. The Egyptian Journal of Anatomy 2015.

- Bradley, C. S.; Rovner, E. S.; Morgan, M. A.; Berlin, M.; Novi, J. M.; Shea, J. A.; Arya, L. A. A New Questionnaire for Urinary Incontinence Diagnosis in Women: Development and Testing. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005, 192 (1), 66–73. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C. S.; Rahn, D. D.; Nygaard, I. E.; Barber, M. D.; Nager, C. W.; Kenton, K. S.; Siddiqui, N. Y.; Abel, R. B.; Spino, C.; Richter, H. E. The Questionnaire for Urinary Incontinence Diagnosis (QUID): Validity and Responsiveness to Change in Women Undergoing Non-Surgical Therapies for Treatment of Stress Predominant Urinary Incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 2010, 29 (5), 727–734. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE): Guidelines on Community-Level Interventions to Manage Declines in Intrinsic Capacity: Evidence Profile: Urinary Incontinence. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/342254 (accessed 2025-01-08).

- Shogenji, M.; Yoshida, M.; Kakuchi, T.; Hirako, K. Factors Associated with Caregiver Burden of Toileting Assistance at Home versus in a Nursing Home: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLOS ONE 2024, 19 (3), e0299721. [CrossRef]

- Kegel, A. H. Physiologic Therapy for Urinary Stress Incontinence. J Am Med Assoc 1951, 146 (10), 915–917. [CrossRef]

- Riemsma, R.; Hagen, S.; Kirschner-Hermanns, R.; Norton, C.; Wijk, H.; Andersson, K.-E.; Chapple, C.; Spinks, J.; Wagg, A.; Hutt, E.; Misso, K.; Deshpande, S.; Kleijnen, J.; Milsom, I. Can Incontinence Be Cured? A Systematic Review of Cure Rates. BMC Med 2017, 15 (1), 63. [CrossRef]

- Hay-Smith, E. J. C.; Herderschee, R.; Dumoulin, C.; Herbison, G. P. Comparisons of Approaches to Pelvic Floor Muscle Training for Urinary Incontinence in Women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011, No. 12, CD009508. [CrossRef]

- Curillo-Aguirre, C. A.; Gea-Izquierdo, E. Effectiveness of Pelvic Floor Muscle Training on Quality of Life in Women with Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59 (6), 1004. [CrossRef]

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 155: Urinary Incontinence in Women. Obstet Gynecol 2015, 126 (5), e66–e81. [CrossRef]

- Vignesh, A.; Amal, T. C.; Sarvalingam, A.; Vasanth, K. A Review on the Influence of Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods on Health. Food Chemistry Advances 2024, 5, 100749. [CrossRef]

- Takacs, P.; Pákozdy, K.; Koroknai, E.; Erdődi, B.; Krasznai, Z.; Kozma, B. A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial to Assess the Effectiveness of a Specially Formulated Food Supplement and Pelvic Floor Muscle Training in Women with Stress-Predominant Urinary Incontinence. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23 (1), 321. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).