1. Introduction

The introduction of automatic speech recognition (ASR) systems offers significant benefits to various aspects of society, including increased productivity and expanded opportunities for the elderly and individuals with disabilities. However, effective and safe use of these technologies requires a high degree of accuracy and the ability of the speech model to understand language in a context-sensitive manner.

ASR systems are a set of methods and algorithms aimed at converting spoken language into text form. In recent decades, ASR has evolved from an experimental technology into an integral part of everyday life. Modern ASRs are widely used in various fields, including voice assistants, automatic translation systems, smart device control, and audio data processing.

ASR for the Kazakh language presents several significant challenges, both technical and linguistic. Despite growing interest in studying and digitalizing the Kazakh language, it remains a low-resource language, particularly in the context of speech technologies. Turkic languages, such as Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Uzbek, and Tatar, are considered low-resource languages [

1]. With the exception of Turkish, most Turkic languages have a limited amount of available and labeled audio and text data, which complicates the development of speech recognition algorithms and other speech technology applications. Additionally, the high morphological complexity and agglutinative nature of these languages present further challenges when designing ASR models [

2].

In the era of active development of voice technologies and speech recognition systems, high-quality audio data is becoming the basis for building reliable and practical models. It is impossible to discuss high-precision speech recognition without a thorough understanding of how audio data is collected, annotated, and processed. Behind the scenes of voice assistants, automatic subtitles, and voice recorders lies a complex and labor-intensive process with numerous technical and resource challenges.

Modern research in the field of automatic speech recognition inevitably faces several significant challenges, including the low quality of audio recordings, high variability in speech patterns, the need for many qualified annotators, and the requirement to comply with strict data protection regulations. Although the stage of audio data collection is an important component in the development of speech technologies, a much more complex task is to ensure the high quality and consistency of both the audio fragments themselves and their accompanying annotation.

Audio data often contains elements that allow identifying the speaker, which requires obtaining explicit and documented consent from participants to use their voice information for research or commercial purposes.

The process of annotating audio materials inevitably requires text transcription, the quality of which has a direct impact on the success of model training. The presence of incomplete, inaccurate, or subjective transcription, as well as the use of non-standardized abbreviations and designations, significantly reduces the effectiveness of subsequent processing.

A separate difficulty is the technical quality of audio recordings. The presence of background noise, acoustic distortions, low diction intelligibility, or poor recording conditions complicates the training of models. It requires the use of specialized signal preprocessing algorithms, including noise reduction, volume normalization, and filtering methods. In some cases, data that cannot be corrected is excluded from the training set, which increases the cost of resources and time required to form a comprehensive training sample.

One practical approach to compensate for the lack of audio data is the creation of synthetic speech corpora, which generate audio signals based on text-to-speech (TTS) technologies [

3,

4]. This method enables the scalable acquisition of audio materials with controlled parameters, such as speech rate, intonation, acoustic conditions, and the speaker’s speech characteristics, ensuring the formation of balanced and diverse training samples. An alternative, widely used approach is the extraction of audio data from open-source Internet sources, including podcasts, video hosting sites, and public speech databases. Additionally, data can be collected through targeted recording of user speech using specialized equipment and software. These methods provide realistic examples of spontaneous and formal speech in the Kazakh language across various acoustic and linguistic contexts, which is crucial for testing and training models.

For the Kazakh language, the audio data is limited, compared with high-resource languages, like English. These data are presented in

Section 3.1 below.

The study’s purpose is not only a technical analysis, but also the development of recommendations for improving the availability and quality of voice technologies for Kazakh-speaking users. These recommendations, including proposals for the development of open speech corpora, support for data crowdsourcing initiatives, and stimulation of scientific and commercial projects in Kazakh speech analytics, have the potential to significantly reduce the digital divide and expand the presence of the Kazakh language in the digital space.

2. Related Works

Large datasets, advanced neural architectures, and powerful computing resources have become key factors for developing robust ASR and TTS systems. Current research efforts are focused on enhancing the models’ robustness to noise and their ability to adapt to low-resource languages, improving the capacity to generalize across languages, and increasing the naturalness and expressiveness of synthesized speech.

Authors explored and compared various techniques used across different stages of modern speech recognition systems, concluding that MFCC and deep learning methods form the foundation of the most accurate ASR solutions [

5]. The potential of leveraging speech synthesis to enhance ASR performance is demonstrated using two corpora from distinct domains. The results show the viability of synthetic speech as a data augmentation technique for domain adaptation. While augmenting training data with synthesized speech leads to measurable improvements in recognition accuracy, a notable performance disparity persists between models trained on natural human speech and those trained on synthetic data [

6]. A multilingual End-to-End (E2E) ASR system incorporating LID prediction within the RNN-T framework was proposed, utilizing a cascaded encoder architecture [

7]. Experiments that were conducted on a multilingual voice search dataset encompassing nine language locales demonstrate that the proposed approach achieves an average LID prediction accuracy of 96.2%. The system achieves second-pass word error rates (WER) comparable to those obtained when oracle LID information is provided as input.

The Universal Speech Model (USM), a unified large-scale model designed for ASR across more than 100 languages, was presented in [

8]. A comprehensive overview of ASR systems, focusing on limited vocabulary scenarios, particularly in the context of under-resourced languages, is provided [

9]. The study reviewed key techniques, tools, and recent developments that support the development of ASR systems recognizing a small set of words or phrases. Emphasizing the role of limited vocabulary ASR as a stepping stone for promoting linguistic inclusion, especially for illiterate users, the work highlighted that many of the discussed methods are also applicable to general ASR system development. A series of experiments on low-resource languages in the context of telephony-grade speech, focusing on Assamese, Bengali, Lao, Haitian, Zulu, and Tamil, were presented. The results highlight the effectiveness of the proposed techniques, particularly the learning of robust bottleneck features, in enhancing performance on test data [

10].

Recent studies have made considerable progress in speech and language technologies for low-resource languages, particularly within the Turkic language family, highlighting various approaches to address data scarcity and linguistic complexity. A comprehensive review of ASR development for three low-resource Turkic languages—Uyghur, Kazakh, and Kyrgyz—was presented in [

11]. They analyze common challenges such as data scarcity, pronunciation variation, and linguistic uniqueness, while also highlighting effective techniques and shared strategies that have advanced ASR across these related languages. The multilingual TTS system was developed for ten low-resourced Turkic languages, focusing on a zero-shot learning scenario [

3]. Using only Kazakh language data, they trained an end-to-end TTS model based on the Tacotron 2 architecture. To enable cross-lingual synthesis, they employed a transliteration approach by mapping the Turkic language alphabet to IPA symbols and then converting them into the Kazakh script. The proposed system demonstrated promising subjective evaluation results, showing the potential of transliteration-based methods for multilingual TTS in low-resource settings.

The UzLM language model was developed specifically for continuous Uzbek speech recognition, addressing the lack of publicly available resources for the Uzbek language. The authors explored both statistical and neural network-based language modeling techniques, incorporating linguistic features unique to the Uzbek language. Using a corpus of 80 million words and 15 million sentences, their experiments demonstrated that neural language models reduced the character error rate to 5.26%, outperforming traditional manually encoded methods and confirming the effectiveness of neural approaches in low-resource settings [

12]. An overview of recent progress in natural language processing for Central Asian Turkic languages, including Kazakh, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, and Turkmen. It highlights the persistent challenges of low resources, such as limited datasets and linguistic tools, while also noting advancements like the creation of language-specific corpora and initial models for downstream tasks. The paper emphasizes the role of transfer learning from high-resource languages and provides a comparative analysis of available labeled and unlabeled data, thereby helping to define future research directions in this underexplored area [

13].

A novel deep learning-based end-to-end Turkish TTS system, addressing the absence of a publicly available corpus for the Turkish language [

14]. The authors constructed a dataset using recordings from a male speaker and implemented a Tacotron 2 combined with a HiFi-GAN architecture. Their system achieved high-quality speech synthesis, with a Mean Opinion Score of 4.49 and an objective MOS-LQO score of 4.32. This study represents one of the first documented efforts to apply a Tacotron 2 + HiFi-GAN pipeline to Turkish, demonstrating the feasibility and effectiveness of DL-based approaches for under-resourced TTS development.

The application of the Whisper transformer architecture for Turkish ASR was explored in [

15], targeting a low-resource language with distinct linguistic features. Initial experiments conducted on five Turkish speech datasets reported WER ranging from 4.3% to 14.2%. To improve performance, Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) was applied for efficient fine-tuning, resulting in WER reductions of up to 52.38%. This study demonstrates the potential of adapting large-scale pretrained models like Whisper for low-resource ASR and provides practical approaches to addressing language-specific challenges.

A freely available speech corpus for the Uzbek language, referred to as the Uzbek Speech Corpus (USC) [

16]. The corpus includes transcribed audio recordings from 958 distinct speakers, totaling 105 hours of speech data. To ensure data quality, all recordings have been manually verified by native Uzbek speakers. Experimental evaluations indicate USC’s strong potential for advancing ASR research and development.

Facebook’s Wav2Vec2.0 and Wav2Vec2-XLS-R models and OpenAI’s Whisper were used to evaluate the performance of standard speech models in transcribing the Kazakh language and compare their performance with existing supervised ASR systems. Also, experiments with the Whisper architecture, focusing on fine-tuning in different scenarios, and with the Wav2Vec2.0 and Wav2Vec2-XLS-R architectures, exploring different pre-training and fine-tuning scenarios, were described. Authors compare two accurate neural-based ASR architectures, Wav2Vec2.0 and Whisper, with the baseline E2E Transformer model [

18]. The evaluation obtained from the comparative data between the models provides insight into the performance of these models for the Kazakh language and may also be relevant for other low-resource languages.

The first open-source Kazakh speech dataset for TTS applications is presented in [

4]. The collected dataset consists of over 93 hours of transcribed audio recordings, consisting of about 42,000 recordings. The authors built the first Kazakh E2E-TTS systems based on the Tacotron 2 and Transformer architectures and evaluated them using the subjective MOS metric. The transcribed audio corpus collected in [

2] comprises 554 hours of data in the Kazakh language, providing insight into letter and syllable frequencies, as well as demographic parameters such as gender, age, and region of residence of native speakers. Experiments in machine learning were carried out using the DeepSpeech2 model. To enhance model robustness, filters initialized with symbol-level embeddings were incorporated, minimizing the model’s reliance on precise object map positioning. During training, convolutional filters were simultaneously optimized for both spectrograms and symbolic objects. The proposed method in [

2] resulted in a 66.7% reduction in model size while preserving accuracy, with the character error rate (CER) on the test set improving by 7.6%. Authors introduced the Kazakh Speech Corpus (KSC), an open-source dataset containing approximately 332 hours of transcribed audio from over 153,000 utterances by speakers of various ages, genders, and regions [

18]. To evaluate the quality and reliability of the corpus, the authors conducted ASR experiments using ESPnet, achieving a CER of 2.8% and a WER of 8.7% on the test set, which indicates the high quality of both the audio recordings and their transcriptions.

The authors presented a cascade speech translation system for the Kazakh language, incorporating ASR and machine translation (MT) modules trained on the ST-kk-ru dataset, which was derived from the ISSAI Corpus [

19]. They employed state-of-the-art deep learning techniques for both ASR and neural machine translation, achieving an improvement of approximately 2 BLEU points by augmenting the training data. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the cascade approach and highlight the importance of leveraging additional data to enhance translation quality for low-resource language pairs. Transformer-based and connectionist temporal classification (CTC) models were investigated to develop an end-to-end speech recognition system for the Kazakh language [

20]. Given the agglutinative nature of Kazakh and the scarcity of available training data, the study explored the advantages of Transformer architectures, which have shown promising results in low-resource language settings. The experiments demonstrated that combining Transformer and CTC approaches, along with an integrated language model, achieved a CER of 3.7% on a clean test set, indicating a significant improvement in recognition accuracy. The research focuses on speech recognition for the Kazakh language using advanced deep learning techniques alongside traditional models such as Hidden Markov Models (HMM) [

21]. The study explores key components including data preprocessing, acoustic modeling, and language modeling tailored to Kazakh’s linguistic features. It emphasizes the importance of developing precise and reliable ASR systems for Kazakh, addressing challenges related to low-resource languages, and discusses potential applications and future directions in this field.

The Soyle model [

22] was shown to perform effectively across both the Turkic language family and the official languages of the United Nations. In the same work, the first large-scale open-source speech dataset for the Tatar language was introduced, along with a data augmentation technique aimed at improving the noise robustness of ASR models. A significant contribution to Kazakh ASR research was made in [

23], where the first industrial-scale open-source speech corpus was introduced. This resource includes the KSC and KazakhTTS2, and incorporates additional data from television news, radio programs, parliamentary speeches, and podcasts.

The reviewed studies were selected to provide a comprehensive understanding of recent advancements, methodologies, and challenges in the development of speech and language technologies for Turkic and low-resource languages. By analyzing works related to ASR, TTS synthesis, language modeling, and multilingual processing—particularly for languages such as Kazakh, Uzbek, Turkish, and others—we aim to identify effective strategies, transferable techniques, and gaps that remain unaddressed. These insights serve as a foundation for our future research, which will focus on enhancing the performance of end-to-end ASR and TTS systems, improving language representation in multilingual models, and developing robust, scalable tools for Turkic languages with minimal annotated resources.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Speech Recognition and Synthesis Systems for Kazakh Language

Speech recognition and synthesis technologies have experienced remarkable development in recent years, largely driven by advances in deep learning. ASR systems are designed to transcribe spoken language into text. Traditional ASR architectures based on HMM and Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) have largely been replaced by end-to-end models such as Transformer [

24], Conformer [

25], and Whisper [

26], which unify acoustic, language, and pronunciation models into a single deep neural network.

In low-resource settings such as the Kazakh language, the lack of large annotated corpora present a major limitation. To address this, researchers have applied techniques like transfer learning [

27], multilingual modeling [

28], and LoRA [

29] to adapt pre-trained ASR models to Kazakh and other Turkic languages. Open-source toolkits such as ESPnet [

30], Kaldi [

31], and Hugging Face’s Transformers library [

32] provide flexible environments for building such systems.

In parallel, TTS synthesis has evolved from concatenative and parametric approaches to fully neural, end-to-end architectures. Systems such as Tacotron 2 [

33], FastSpeech 2 [

34], and HiFi-GAN [

35] achieve high-quality synthesis by modeling both prosody and phonetic detail. These models often include a sequence-to-sequence frontend with attention mechanisms and a neural vocoder to generate realistic waveforms.

For the Kazakh language, research efforts have focused on developing ASR and TTS systems using small-scale datasets and transliteration techniques. For instance, multilingual TTS approaches leveraging IPA mapping and zero-shot synthesis have shown promising results for Turkic languages [

3]. Despite the progress in the research, due to the fact that the Kazakh language is a low-resource language and is an agglutinative language, the problem still remains.

Table 1.

Kazakh Audio Resources – Availability and Total Duration.

Table 1.

Kazakh Audio Resources – Availability and Total Duration.

| Audio corpora name |

Data type |

Volume |

Accessibility |

| Common Voice [36] |

Audio recordings, with transcriptions. |

150+ hours |

open access |

| KazakhTTS [37] |

Audio-text pair |

271 hours |

conditionally open |

| Kazakh Speech Corpus [18,38] |

Speech + transcriptions |

330 hours |

open access |

| Kazakh Speech Dataset (KSD) [2,39] |

Speech |

554 hours |

open access |

3.2. Audio and Text Dataset Formation

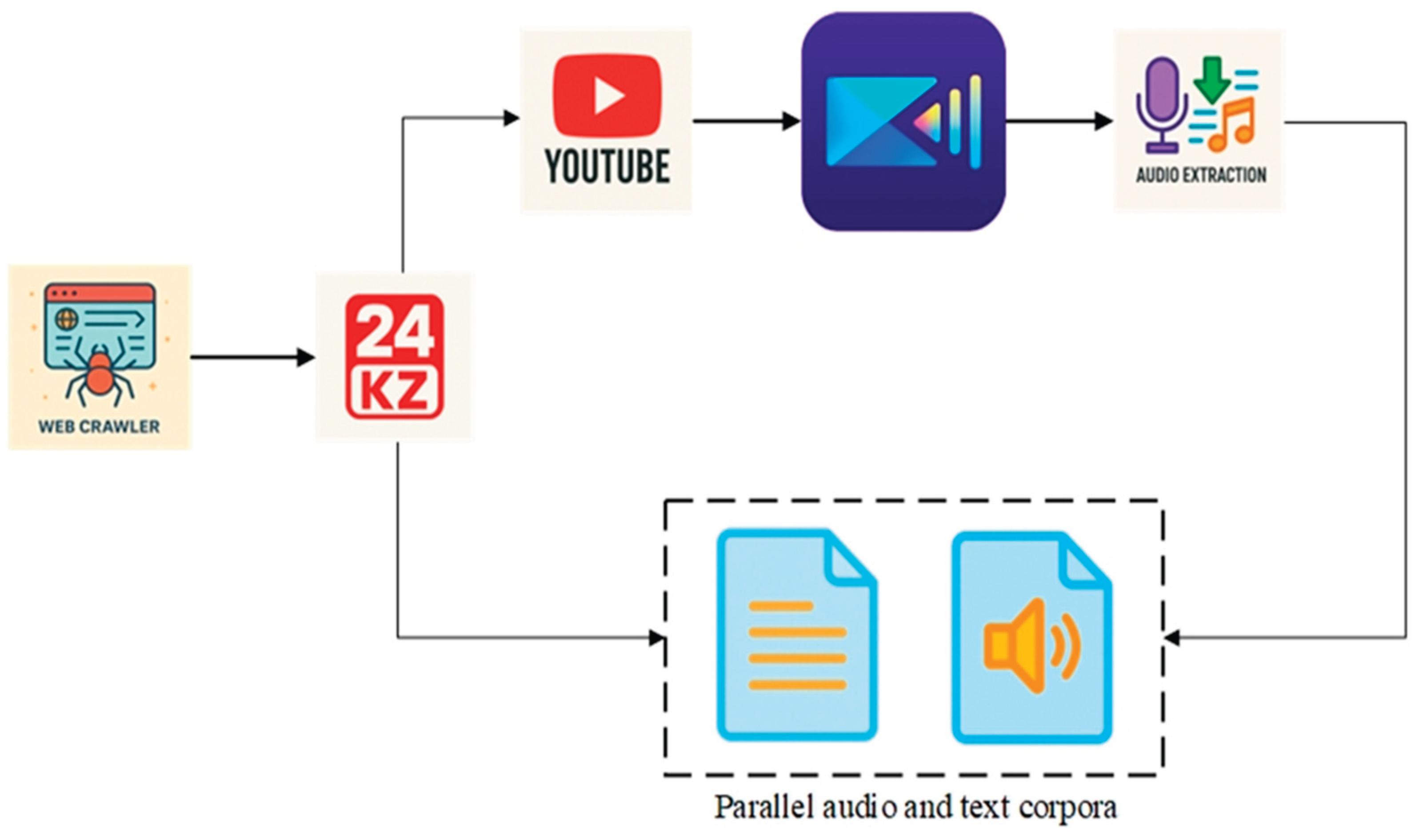

Speech-to-Text (STT) and TTS are tasks that transform audio data into textual data and vice versa, respectively. These tasks require the datasets to be qualitative, precise, and mainly formal in nature. The Kazakh news website is valuable because it features YouTube-hosted video content accompanied by textual transcripts. The 24.kz news portal was scraped using a Python script, retrieving the Title, Date, Script, YouTube URL, and web page URL. Another script was implemented for downloading videos from YouTube’s video hosting service. This step ensures that high-quality, diverse spoken language samples are captured directly from real-life broadcasts, which is crucial for building robust STT and TTS systems. Audio files from videos are extracted using video editing software such as Cyberlink PowerDirector or CapCut, which are commonly used in multimedia processing. They provide the possibility of separating audio tracks from video content, allowing for working with sound independently. The audio files were exported as MP3 and WAV files with a unified frequency range. For effective audio processing, the speech was split into sentences and saved in separate files. For effective audio processing, the speech was split into sentences and saved in separate files. The corresponding textual scripts were also split into sentences and saved in separate files. The scheme of web scraping, audio extraction, and parallel corpora formation is shown in

Figure 1.

Then, the ready-made parallel audio and textual corpora from Nazarbayev University were taken. The same process was used to split audio and text into sentences and save them in separate files. Therefore, the audio and textual corpora of 200 sentences (100 sentences scraped from the news portal and 100 sentences of Nazarbayev University) were formed. Then, the ready-made parallel audio and textual corpora from Nazarbayev University were taken. The same process was used for splitting audio and text into sentences and saving them in separate files.

3.3. ASR Systems and Selecting Criteria

Several existing ASR systems were considered and evaluated based on a predetermined set of criteria, each of which plays a crucial role in the practical application of speech recognition technologies. The criteria were arranged in order of importance, allowing for an objective analysis.

Availability. The most important criterion was the system’s availability for large-scale use. This concept meant both technical availability (the ability to deploy and integrate quickly) and legal openness, including the availability of a free license or access to the source code. Preference was given to open-source solutions that did not require significant financial investments at the implementation stage.

Recognition quality. One of the key technical parameters was the linguistic accuracy of the system. This crucial factor ensures the system’s ability to correctly interpret both standard and accented speech, taking into account the language’s morphological and syntactic features. Particular attention was also paid to the contextual relevance of the recognized text, that is, the system’s ability to preserve semantic integrity when converting oral speech into written form.

The efficiency of subsequent processing. An additional criterion was the system’s ability to effectively work with a large volume of input data, implying not only accurate recognition but also the possibility of further processing (for example, automatic translation or categorization of content). Special importance was given to the scalability of the architecture and support for batch processing of audio files, ensuring a high-performance system.

There are several ASR models and systems that are effectively used for converting audio data into text. Among them, the most significant ones in recognizing the Kazakh speech are Whisper, GPT-4o-transcribe, Soyle, Elevenlabs, Voiser, and others.

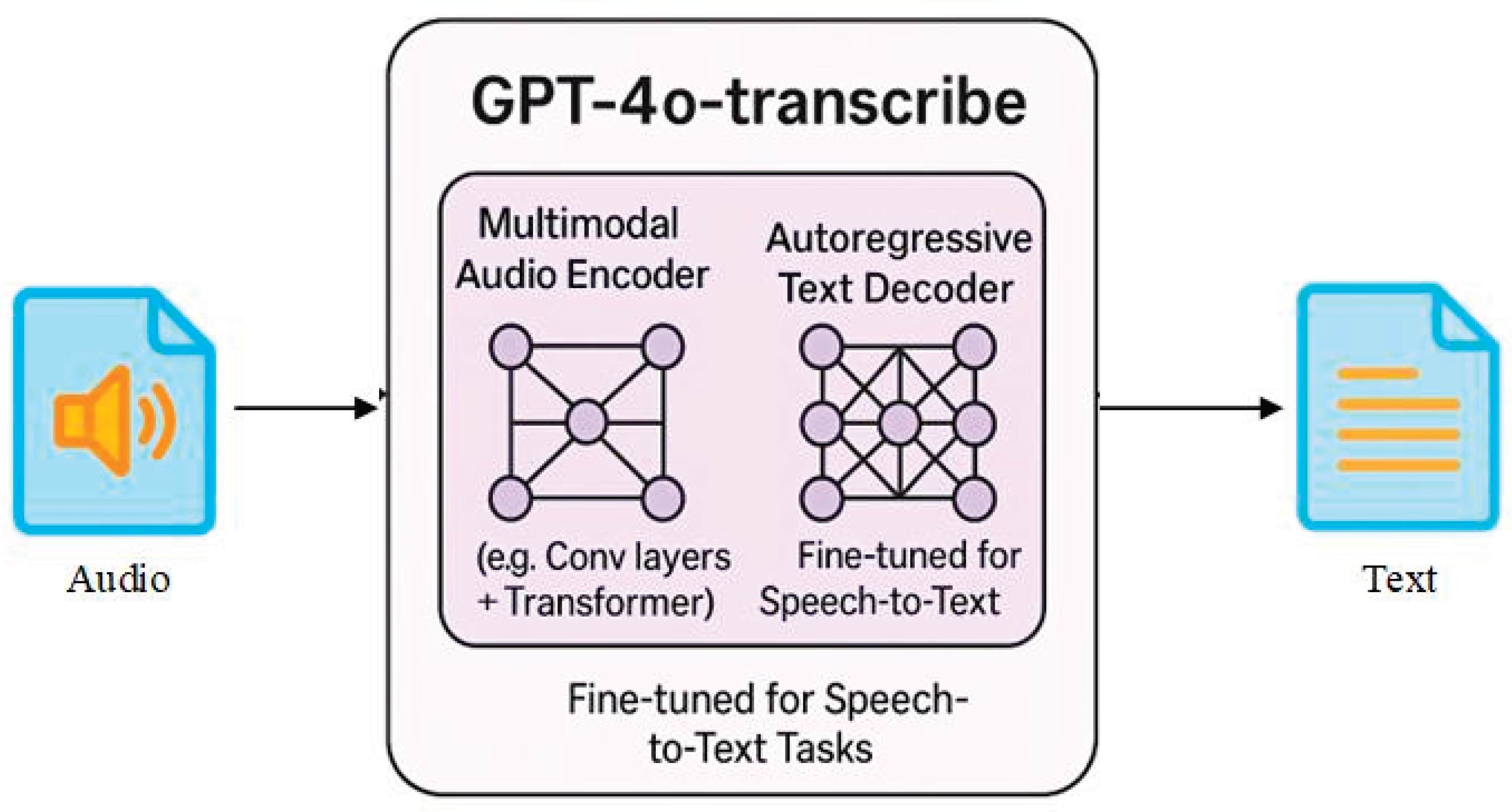

GPT-4o-transcribe is an STT model developed by OpenAI. It is fine-tuned to bring high-accuracy transcription across a wide range of languages [

40]. One of the key advancements of this model is its significantly lower word error rate and improved language recognition compared to the Whisper model. GPT-4o-transcribe demonstrates strong performance in recognizing low-resource and morphologically rich languages, such as Kazakh. GPT-4o-transcribe’s ability to perform reliably in noisy or complex audio environments establishes it as a leading model for transcription tasks that demand high accuracy across diverse languages. The scheme of the audio conversion to text with GPT-4o-transcribe is shown in

Figure 2.

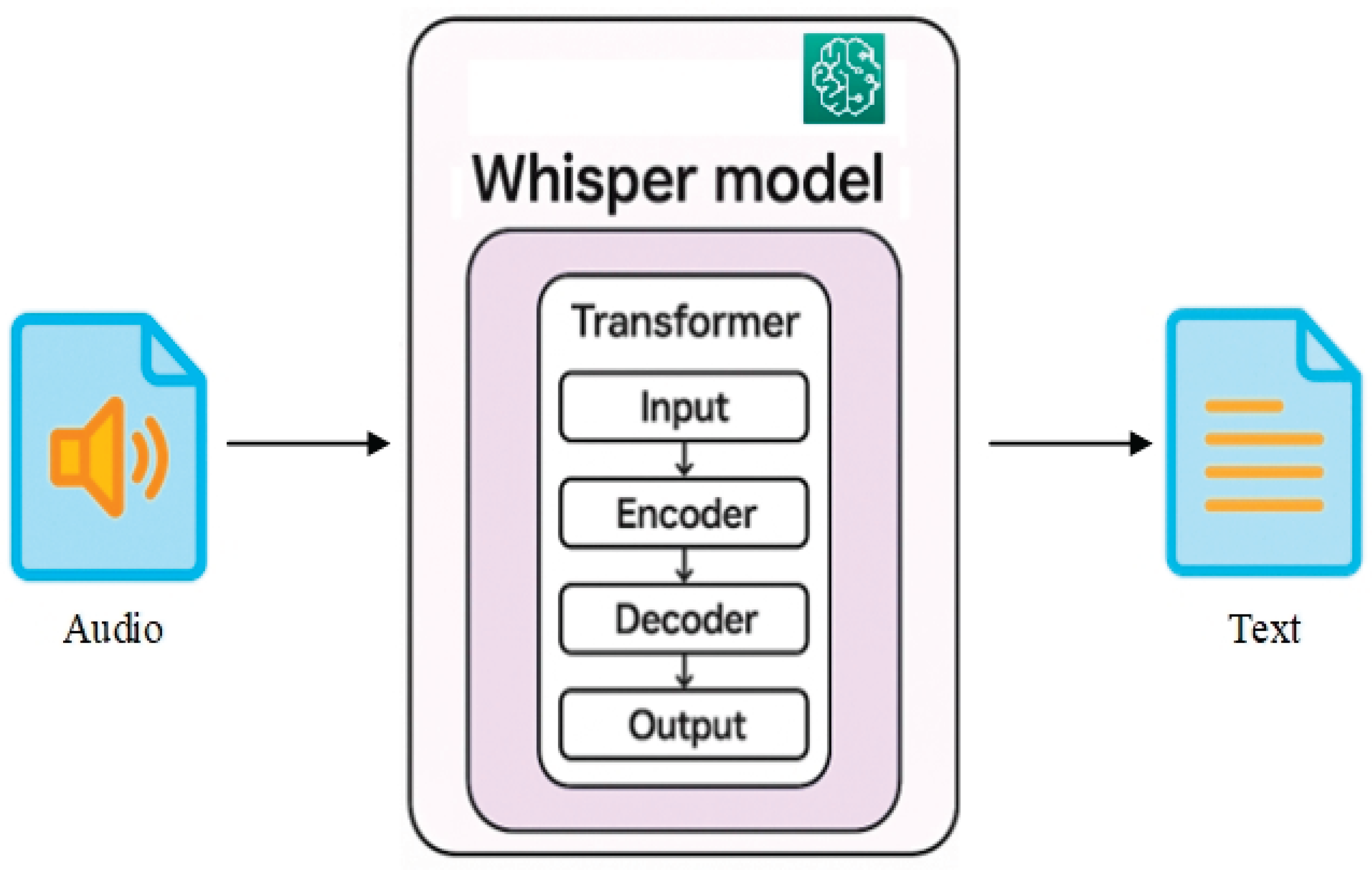

The Whisper model, developed by OpenAI [

41], is designed to convert spoken language into written text and supports a wide variety of languages and tasks. A notable strength of Whisper is its multilingual capability of over 99 languages. It can automatically detect the spoken language and also perform speech translation. At the heart of Whisper is a transformer-based encoder-decoder architecture, similar to models like GPT. The encoder takes audio input represented as log-Mel spectrograms, while the decoder generates text tokens in an autoregressive fashion. This design allows Whisper to transcribe speech and translate complex audio, even when challenged by background noise, regional accents, or atypical pronunciation. Whisper is available in several model sizes, ranging from lightweight versions to a “large” model that delivers the highest accuracy, albeit with increased computational requirements. All versions are trained on an extensive dataset of 680,000 hours of audio collected from the web, encompassing a broad spectrum of noisy and multilingual speech scenarios. This training makes Whisper remarkably resilient compared to conventional ASR systems.

The scheme of the audio conversion to text with Whisper is shown in

Figure 3.

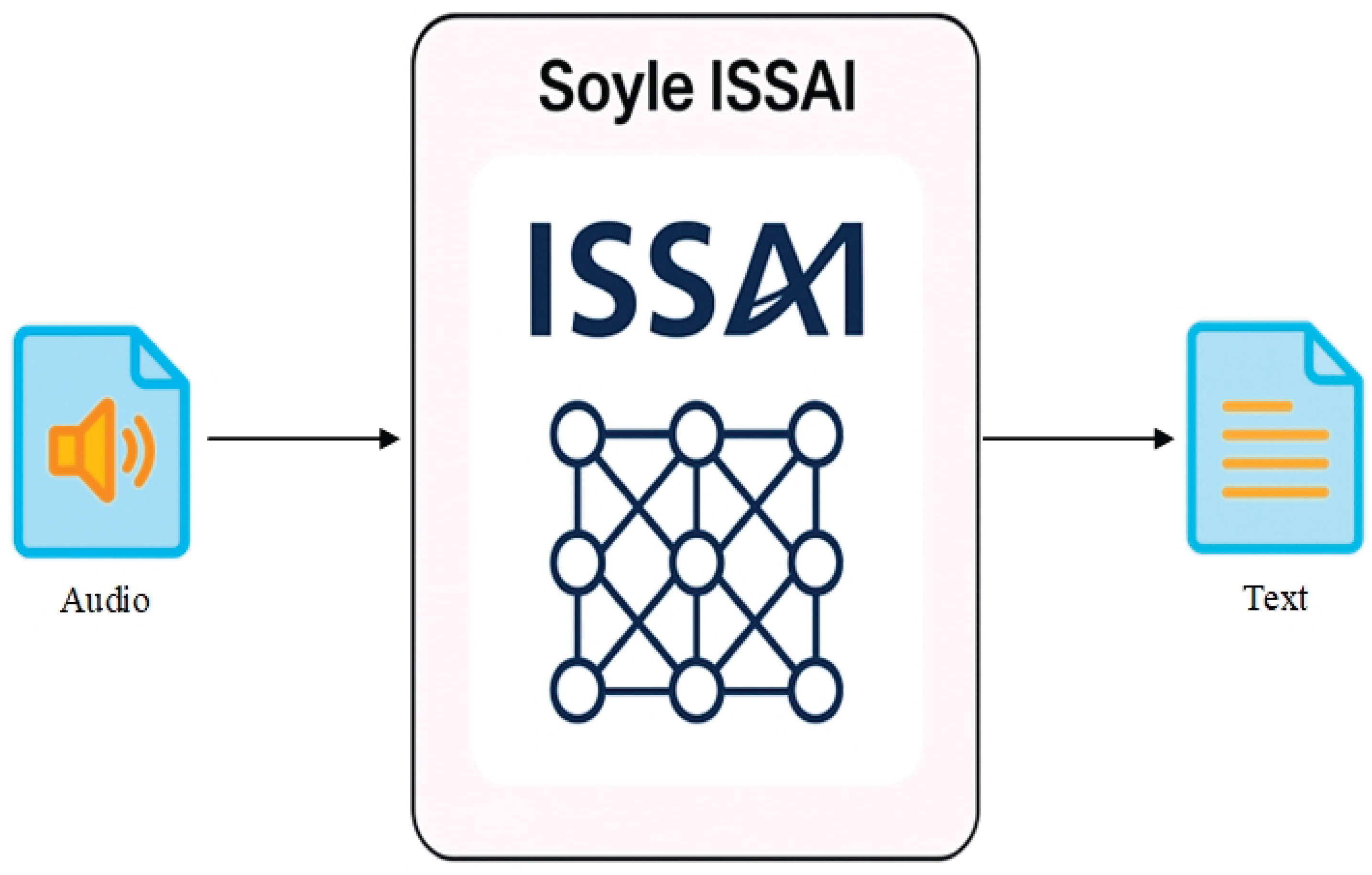

The Soyle model is an advanced STT system developed by the Institute of Smart Systems and Artificial Intelligence (ISSAI) at Nazarbayev University, with a particular focus on low-resource Turkic languages, especially Kazakh [

42]. While many global STT models struggle with underrepresented languages due to limited training data, Soyle was trained and fine-tuned on extensive Kazakh-language datasets, including the Kazakh Speech Corpus 2 and Mozilla’s Common Voice. This targeted training provides Soyle with a significant advantage in accurately transcribing Kazakh speech across different dialects and speaking styles. The key specification of Soyle is its effectiveness against background noise and speaker variability, a crucial feature for practical use in real-world settings, such as classrooms, interviews, and public events. Unlike many other STT systems, Soyle achieves high transcription accuracy due to its exposure to diverse and realistic audio during training.

The scheme of the audio conversion to text with Soyle is shown in

Figure 4.

ElevenLabs is one of the most advanced systems in speech recognition today. It stands out for its efficiency and support of the Kazakh language [

43]. This marks a significant advancement, as Kazakh has long been underrepresented in the field of speech recognition. ElevenLabs’ STT model delivers outstanding transcription accuracy for Kazakh, positioning itself as one of the most effective commercial STT solutions. It also includes speaker diarization, enabling the model to distinguish between multiple speakers, which is beneficial for transcribing meetings, interviews, or panel discussions. Moreover, the model can detect non-verbal audio events, such as laughter or applause, thereby enhancing the contextual quality of the transcription. These capabilities are accessible through an API, while the ElevenLabs website provides an interface for uploading audio files. Currently, the model is optimized for file-based transcription, with a low-latency, real-time version in development. Overall, ElevenLabs’ STT model represents a significant leap forward in speech-to-text technology for low-resource languages, such as Kazakh.

The scheme of the audio conversion to text with Elevenlabs is shown in

Figure 5.

The Voiser model is another ASR system developed to convert spoken audio into written text [

44]. It is designed to support a broad range of languages, with a specific emphasis on Turkic languages such as Kazakh and Turkish. Voiser’s STT system is built on advanced deep learning architectures, specifically Transformer-based encoder-decoder networks, which are well-suited for processing speech in real-world, noisy environments. Although not all technical specifications of the model are described, the model offers several key features, including transcription, punctuation restoration, and speaker diarization. Delivered as a cloud-based service, Voiser is easily integrated into various use cases, including meeting transcription, media subtitling, and voice analytics for call centers. The Voiser model is very strong in processing the Kazakh language. By delivering an accurate transcription for Kazakh, the model fills a critical gap in speech recognition of this language. Overall, the Voiser system combines speed, accuracy, and flexibility to serve both global and local linguistic needs. The scheme of the audio conversion to text with Elevenlabs is shown in

Figure 6.

The comparison of STT models is presented in

Table 2.

3.4. Text-to-Speech (TTS)

Modern TTS systems employ deep neural network models that significantly enhance the quality of synthesis, yielding speech that is more natural and expressive. One of the first models to demonstrate the potential of the neural network approach is Tacotron. Tacotron 1 implements a sequential architecture with an attention-based engine, converting the input text into a mel spectrogram, which is then converted into sound using a separate vocoder.

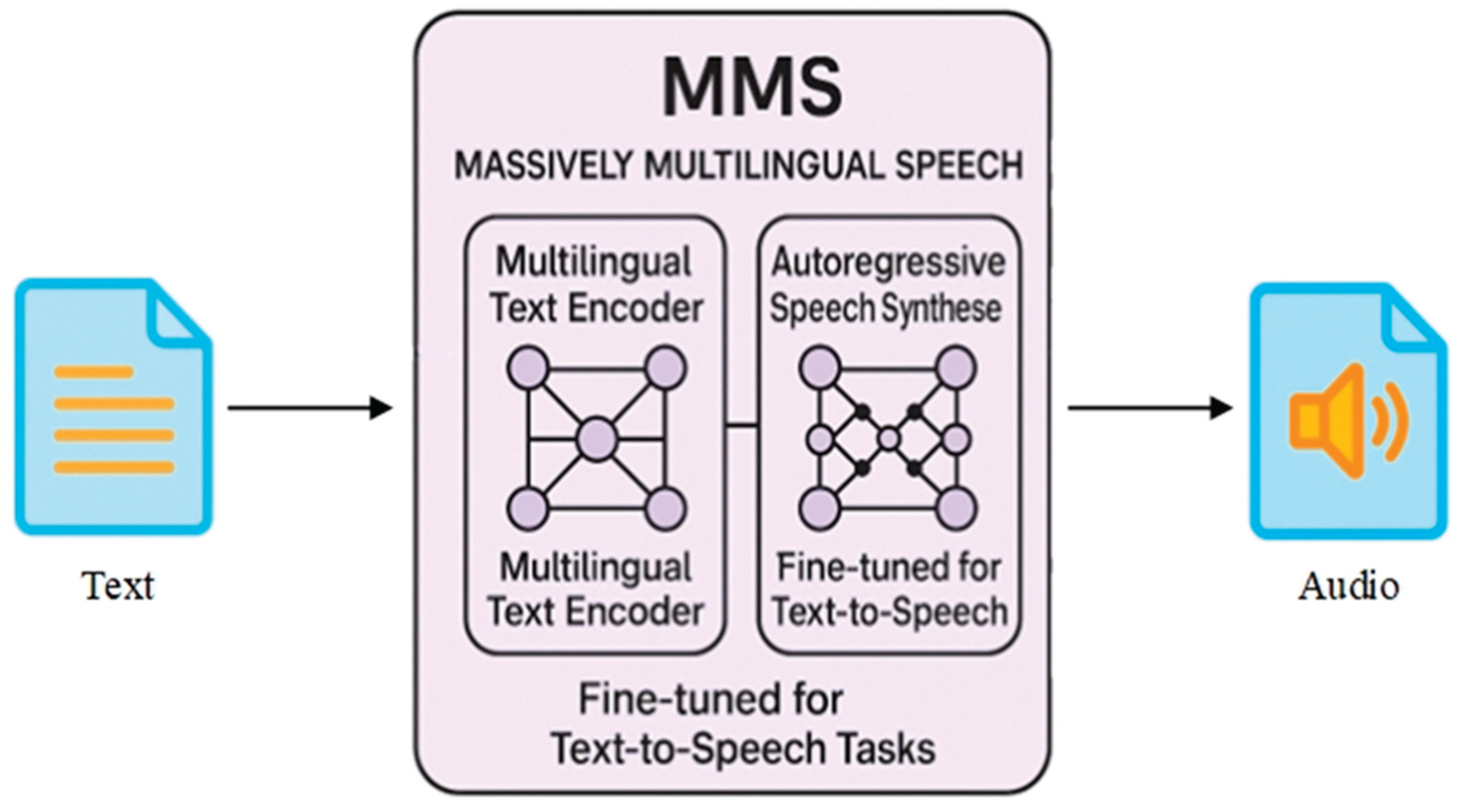

The Massively Multilingual Speech (MMS) model, developed by the Meta AI research unit, is a large-scale, general-purpose system for language recognition, synthesis, and identification, covering over 1,100 languages, including Kazakh [

54]. Unlike many multilingual models, which are limited to a few dozen languages, MMS significantly expands its coverage by utilizing self-supervised approaches and training on massive multilingual speech corpora, partly collected from religious and educational sources. MMS is architecturally built on wav2vec 2.0, modified for multi-task learning. This model utilizes contrastively learned transformers to extract language-independent features from audio signals. Support for both ASR and TTS makes MMS a versatile solution, although its performance for Kazakh may be inferior to that of more specialized models. For Kazakh, the model provides ASR and TTS functionality, making it unique in the context of supporting languages with limited digital resources. However, despite its broad language support, MMS’s performance in Kazakh is inferior to specialized national solutions, especially for dialectal and colloquial speech variants. MMS can quickly adapt to low-resource languages through massive multilingual learning and has shown competitive results even with small amounts of audio data. The text to audio conversion using MMS is shown in

Figure 7.

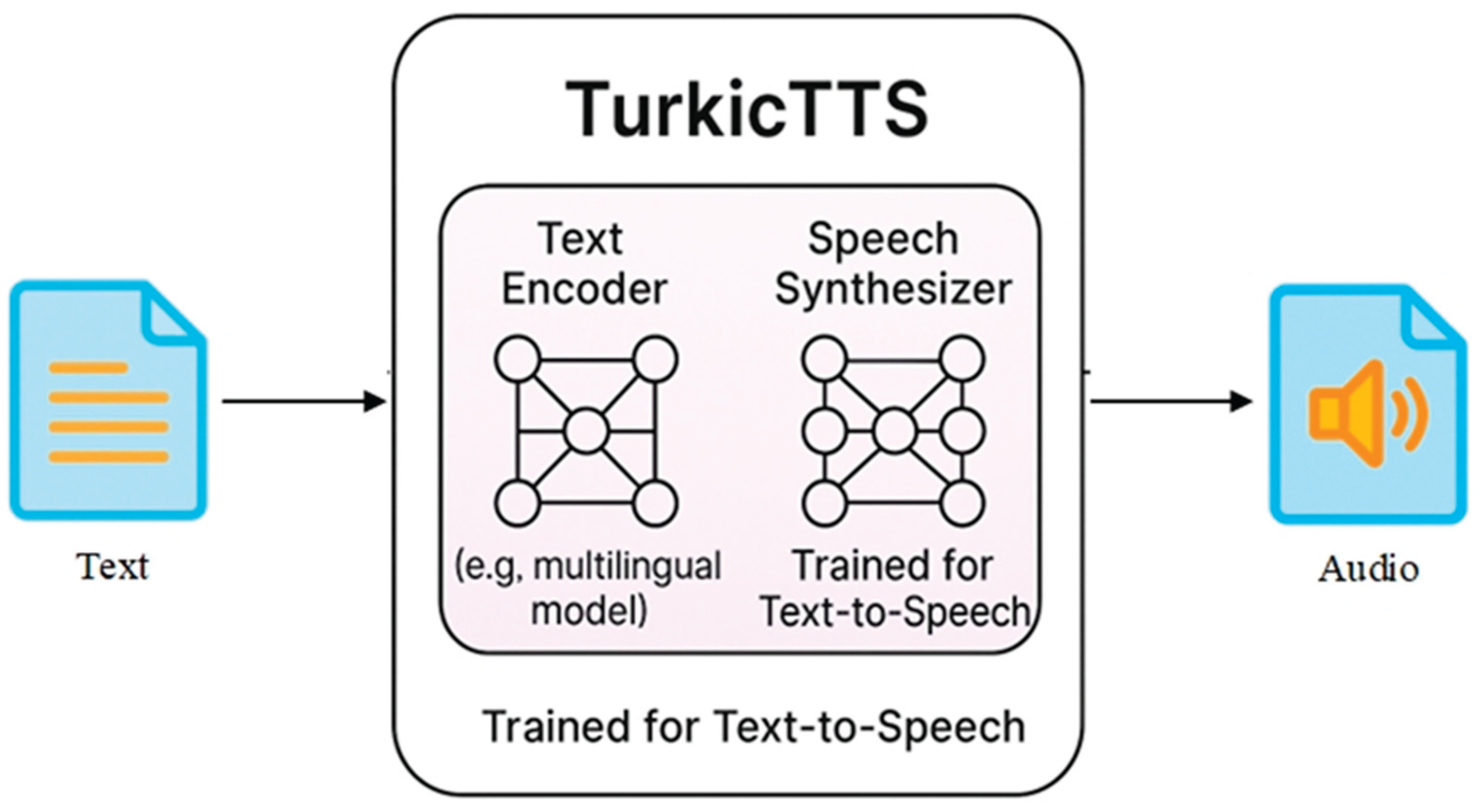

TurkicTTS is a specialized initiative, developed by the researchers at Nazarbayev University, aimed at developing a text-to-speech system for Turkic languages [

55]. TurkicTTS is a multilingual speech synthesis system for Turkic languages using transliteration based on the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). The system architecture is based on a combination of Tacotron2 and WaveGAN models, enabling a full-fledged end-to-end approach to speech synthesis. The Tacotron2 model converts input text into logarithmic mel spectrograms. The architecture includes a bidirectional LSTM-based encoder and an autogenerative decoder with an attention mechanism. To convert spectrograms into an audio signal, the WaveGAN neural network vocoder, modified and trained on Kazakh audio data, is used. TurkistTS provides zero-shot speech generation trained exclusively on the Kazakh language, and is capable of synthesizing speech in other Turkic languages without additional training. This method enables the use of a single TTS model for a wide range of related languages, despite the lack of audio corpora for most of them. TurkicTTS, with its high efficiency, is a powerful tool for solving speech synthesis problems, especially in conditions of limited language and audio resources. The process of text conversion to audio using TurkicTTS is shown in

Figure 8.

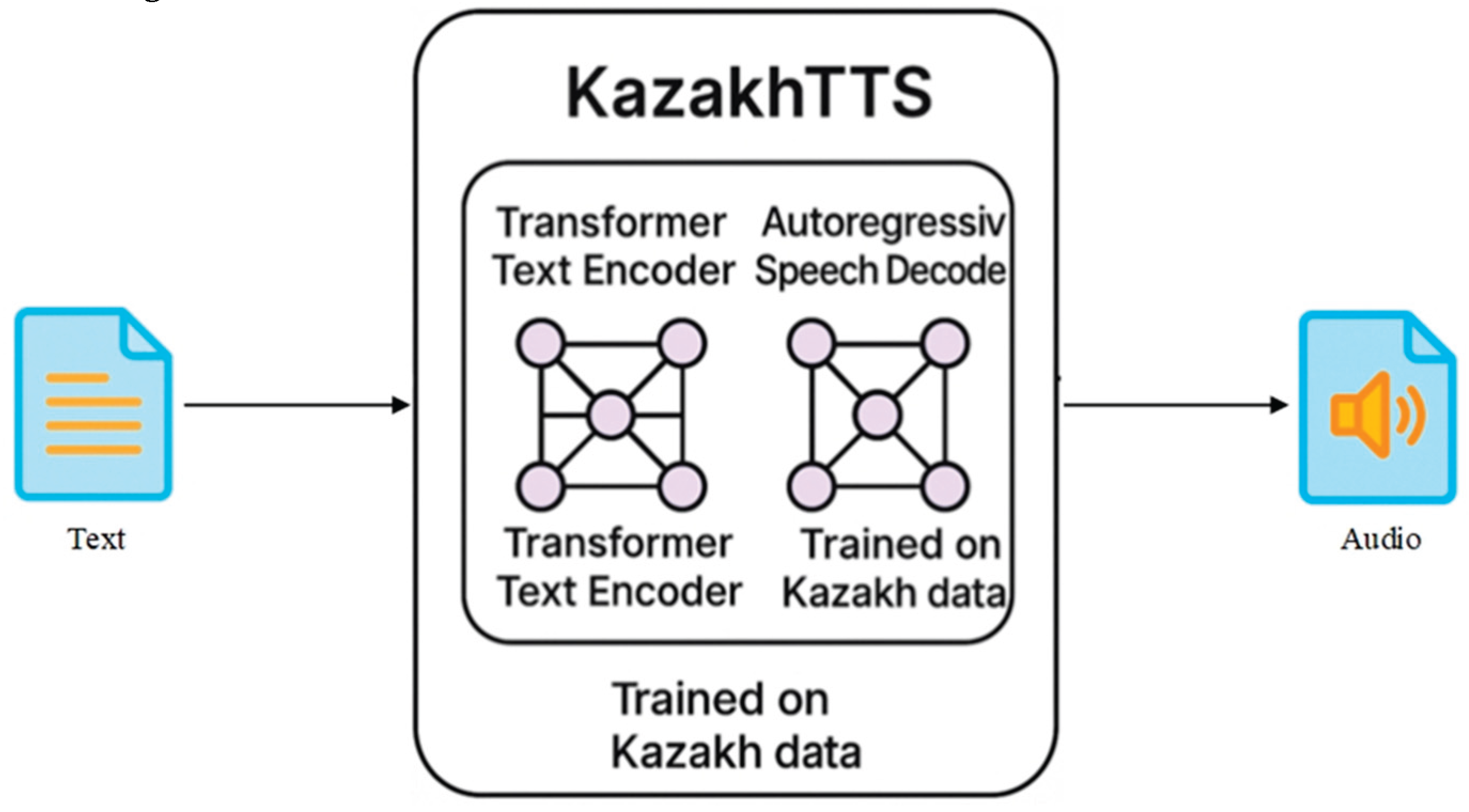

KazakhTTS2 is the second iteration of the national speech synthesis system for the Kazakh language, developed as part of the initiative to support digital Kazakh speech [

56]. KazakhTTS2, with its modern neural network architectures and innovative approach, is a significant advancement in the field. It uses Tacotron 2 to generate a spectrogram from the text, employing a two-phase architecture (Seq2Seq + attention). HiFi-GAN is then utilized as a neural network vocoder to convert the spectrogram into an audio signal. This powerful combination enables the system to achieve a high degree of naturalness in speech, with smooth intonations and adequate stress placement. These features are particularly significant for the Kazakh language due to its unique phonological system. Moreover, KazakhTTS2 is a crucial tool for emotional voice applications, where the emotional perception of the voice is as important as readability. Despite high basic performance, the model requires additional adaptation to generate emotional or expressive speech, which remains the subject of further research and development. The process of text conversion to audio using KazakhTTS2 is shown in

Figure 9.

The ElevenLabs TTS system is a versatile tool, capable of generating high-quality, natural, context-adaptive, and emotionally charged speech in a wide range of languages [

57]. This includes Kazakh, a language it has been able to synthesize since 2024. The company does not disclose the source code, so the exact architecture is unknown. However, it is known that the system generates a representation of future speech, typically as a spectrogram or a sequence of quantized audio tokens, using a neural network transformer, such as an autoregressive transformer or a diffusion-based architecture. The process of text conversion to audio using KazakhTTS2 is shown in

Figure 10.

Unlike traditional TTS models, the OpenAI TTS architecture is tightly integrated with language models, allowing it to utilize advanced speech generation methods that are integrated with the GPT architecture [

58]. One of its key strengths is its competitive performance in multiple languages, including Kazakh, which reassures users of its quality.. The architecture employs an approach similar to VALL-E (quantized audio coding + autoregressive transformer) or Jukebox-style models. In this process, audio reconstruction is performed through hierarchical transformers, leading to the generation of speech in the form of tokens corresponding to audio codecs (for example, EnCodec). This method allows for the creation of natural and expressive voice responses with high contextual relevance. The system’s tight integration with GPT enables it to adjust intonation, pauses, and emotional accents based on the text’s meaning, further enhancing the quality of the generated speech. It allows for the creation of highly accurate synthesized speech. However, despite its technical advantages, the system remains closed, as it can only be used via an API, without the ability to fine-tune or further train, which limits its flexibility and adaptation to specific tasks. The process of converting text to audio using OpenAI TTS is illustrated in

Figure 11.

Table 3.

The comparison of TTS models.

Table 3.

The comparison of TTS models.

| Models |

Advantages |

Drawbacks |

|

MMS

|

Open-source and publicly available

Supports 1,100+ languages, including Kazakh

Unified model for ASR, TTS, and language identification

Trained on a vast amount of data

|

Less optimized for real-time use

May show degraded performance on specific dialects

|

|

TurkicTTS

|

Specially designed for Turkic languages into 7 languages (Azerbaijani, Bashkir, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Sakha, Tatar, Turkish, Turkmen, Uyghur, and Uzbek)

Incorporates phonological features of Turkic speech

Provides open research resources and benchmarks

|

sometimes incorrectly identifies Turkic languages

Limited in domain coverage and audio quality variation

Research-focused with minimal production integration

|

|

KazakhTTS2

|

Tailored for high-quality Kazakh TTS

Improved naturalness and prosody over earlier versions

Developed for national applications

Open-source and available via GitHub

|

Limited to Kazakh only

Requires fine-tuning for expressive or emotional speech

|

| Elevenlabs |

High-fidelity, human-like voice synthesis

Supports multilingual and emotional speech

User-friendly web and API interfaces

Fast inference and low-latency output

|

Commercial licensing with usage restrictions

No access to full training data or fine-tuning options

|

|

OpenAI TTS

|

Advanced TTS with realistic prosody and expressiveness

Integrated with GPT models for contextual generation

Robust handling of punctuation, emphasis, and emotion

|

closed model; not open-source

Limited user control and customization

Subject to usage caps or API quotas

|

3.5. Text and Audio Quality Metrics

The evaluation of STT systems is primarily based on the use of three key metrics: Bilingual Evaluation Understudy (BLEU), WER, and Translation Edit Rate (TER). Each of these metrics offers a different perspective on how accurately the system reproduces human-spoken content in written form.

BLEU is a metric developed initially for MT but is also applied in STT evaluation, especially when multiple valid transcriptions are possible. BLEU measures the overlap of n-grams (sequences of words) between the predicted transcription and the reference text [

45]. It calculates precision scores for 1- to 4-grams, applying a brevity penalty to penalize short outputs. BLEU scores range from 0 to 1, where a higher score indicates greater similarity between the generated text and the reference text. While BLEU is useful for capturing phrase-level correctness and can tolerate minor word order variations, it may not always reflect meaning preservation in short sentences or with minor word changes, making it a less direct fit for STT than other metrics. The BLEU metric is computed by (1):

where

is a modified precision for n-grams;

is a weight for each n-gram level; BP is a brevity penalty, calculated as (2):

where c is the length of the candidate transcription; r is the length of the reference transcription.

WER is the most widely adopted metric in the field of speech recognition. It directly measures the number of errors in the transcription at the word level [

46]. Specifically, WER is calculated as the sum of substitutions, insertions, and deletions required to transform the system’s output into the reference transcription, divided by the number of words in the reference. The lower the WER, the better the transcription quality. A WER of 0 indicates a perfect match. This metric is highly interpretable and intuitive, making it the gold standard for evaluating STT systems. WER is calculated as (3):

where S is the number of substitutions; D is the number of deletions; I is the number of insertions; N is the total number of words in the reference.

TER comes from the field of MT but is also useful for STT evaluation. TER measures the number of edits (insertions, deletions, substitutions, and shifts of word sequences) needed to convert the hypothesis into the reference transcription, normalized by the number of words in the reference [

47]. Unlike WER, TER allows for shifts, capturing cases where words are correct but in the wrong order. It makes TER useful in contexts where flexibility in word order is acceptable. However, it is more complex to compute than WER and is less commonly used for real-time or low-resource STT benchmarking. TER is calculated as (4):

where S is the number of substitutions; D is the number of deletions; I is the number of insertions; Sh is the number of shifts; R is the total number of words in the reference.

chrF is a character-based metric based on the intersection of character n-grams between a hypothesis and a reference [

48]. It was initially developed for translation evaluation, but is also widely used in STT, especially in morphologically rich languages where word-based evaluation may be inaccurate. Unlike WER or BLEU, chrF works at the character level rather than the word level, allowing it to measure morphological and lexical differences even when words overlap accurately.

chrF, with its robustness to partial matches, is not sensitive to word order and works exceptionally well in agglutinative languages (e.g., Kazakh) where words can be long and morphologically complex. chrF is calculated as (5):

where, P - precision: proportion of n-grams in the hypothesis found in the reference, R - recall: proportion of n-grams of the reference found in the hypothesis, β - weight regulating the contribution of recall (usually β=2).

COMET, a practical semantic reference metric, is derived from the field of MT but is also employed to evaluate the quality of STT systems, particularly in multilingual or semantically sensitive tasks. Unlike traditional metrics based on character or word matches, COMET utilizes a neural network model to estimate the semantic similarity between a hypothesis and a reference [

49]. During training, the model learns to predict a human-like quality score (in the range of -1 to 1 or 0 to 1) by comparing the semantic similarity between the hypothesis and the reference. COMET is especially useful when exact word matches are not critical, but maintaining semantic accuracy is important. This metric makes it relevant for STT systems that allow wording variability.

WER, BLEU, and TER are traditional metrics that offer a multifaceted evaluation of STT system output. WER focuses on word-level errors, BLEU measures n-gram matches, and TER considers the number of edits, including shifts, required to align a hypothesis with the benchmark. These metrics enable the examination of both surface accuracy and structural deviations. However, as the demand for high-quality speech recognition in multilingual and noisy environments increases, there is a noticeable shift in interest towards more flexible and semantically sensitive metrics, such as chrF and COMET. These metrics, which complement traditional approaches, enable a deeper analysis of recognition results and engage professionals and researchers in the field in the dynamic evolution of speech recognition evaluation.

The evaluation of speech synthesis (TTS) quality is a comprehensive process, crucial in the development and implementation of speech technologies. It particularly applies to tasks that require high naturalness and intelligibility of sound. Both objective and subjective metrics are used for quantitative analysis of the output audio signal, providing a thorough assessment. The most common ones include Perceptual Evaluation of Speech Quality (PESQ), Short-Time Objective Intelligibility (STOI), MCD (Mel Cepstral Distortion), and LSD (Log Spectral Distance). PESQ and STOI provide automated assessments of the quality and intelligibility of synthesized speech based on acoustic features. At the same time, MCD estimates the acoustic distance between the synthesized and reference speech at the level of mel-cepstral coefficients and is widely used as an indicator of spectral matching quality. Unlike perceptual assessments, MCD enables the quantification of distortion in speech generation, making it particularly useful for debugging vocoders and spectrogram models. For a deeper analysis, modern neural network metrics, such as DNSMOS, are also utilized, which are capable of predicting human perception based on trained models. Together, these metrics provide a comprehensive and multi-level assessment of TTS systems, covering both technical and perceptual characteristics of synthesized speech.

MCD used in TTS to measure how much the spectra of the original and synthesized sound differs, the lower the value, the better (6) [

50].

where T is the total number of frames, M is the number of mel-spectral coefficients,

is the mel-cepstral coefficient of the reference speech at time t,

is the mel-cepstral coefficient of the synthesized speech at time t, ln10 is the natural logarithm of 10.

LSD computes the perceptual difference between the spectrum of a reference and a synthesized speech signal. It reflects spectral distortion that is perceived as a difference in timbre, clarity, or naturalness of the speech. Since human auditory perception is logarithmic in frequency and amplitude, LSD uses the log power spectrum to better model how humans hear differences between sounds (7).

where

K is the number of frequency bins,

is the power spectrum of the reference,

is the power spectrum of the synthesized signal.

PESQ used in TTS to assess speech quality (8) (1–4.5, where 1 - worst quality, 4.5 - almost perfect) [

51];

where

is the average disturbance between reference and degraded signals,

is the variance disturbance,

are emperically derived constants

STOI used in TTS to how well speech can be understood (0–1); the higher, the better (9) [

52].

where

is the total number of analyzed frames,

is a clean speech segment,

is a synthesized speech segment,

is a similarity function that evaluates the similarity in the domain.

DNSMOS (Deep Noise Suppression Mean Opinion Score) is a neural network speech quality assessment metric proposed by Microsoft researchers as part of the Deep Noise Suppression (DNS) Challenge [

53]. Metric is designed to automatically predict MOS (Mean Opinion Score), which is the speech quality assessment that people typically give on a scale from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent). DNSMOS is a non-intrusive model, meaning it does not require a reference signal. It only needs a noisy or synthesized audio file to predict a probable MOS score. This simplicity, combined with the neural network’s training on real human annotations, makes DNSMOS a user-friendly tool for assessing speech quality (10).

where,

x is the input audio signal, Features(

x) are spectral features (e.g. mel, log-power),

is a neural network model with parameters

θ,

is the predicted MOS.

The model is optimized using the MSE (mean square error) between the predicted and actual MOS scores (11):

All of the above metrics are used for a comprehensive assessment of the quality of automatic speech recognition STT and TTS systems, allowing for an objective characterization of their accuracy, naturalness of sound, and effectiveness.

4. Results

Table 4 presents the results obtained based on the evaluation metrics, providing an overview of the STT model quality metrics achieved by the selected ASR system for the Kazakh language collected from the 24kz YouTube portal.

Table 5 shows the quality metrics for STT on the finished audio data from Nazarbayev University.

The use of TTS after STT in this experiment is explained by the need for a two-way quality assessment, encompassing not only speech recognition but also its synthesis. When collecting audio data from the 24kz portal, we didn’t just gather audio, but also their transcribed text, which was then used for TTS. This comprehensive approach ensures the reliability of our results.

Table 6 and

Table 7 show the results of comparing gold audio with that generated with different TTS models.

4. Discussion

The evaluation results of the STT models for Kazakh, presented in

Table 4, based on 24KZ data, demonstrate a significant difference in performance between the systems. The Voiser model demonstrated the highest quality scores, achieving the highest values for chrF (80.88) and COMET (1.01), indicating high accuracy and semantic correspondence between its recognized transcriptions and the reference ones. At the same time, it also showed one of the best results for TER (31.97%) and low WER (40.65%), indicating a minimal number of errors and strong robustness to speech variability.

The Soyle model, despite a slightly higher WER (48.14%), shows promise, achieving the best COMET score (0.97) among the open models and ranking second for chrF (80.35). These values indicate a high level of semantic and morphological recognition accuracy, especially considering that the model was specifically designed for low-resource Turkic languages, including Kazakh. This potential offers hope for the field of speech recognition in the Kazakh language.

GPT-4 Transcribe and ElevenLabs also demonstrated stable and competitive results, providing a reassuring balance between accuracy and semantic recall. GPT-4 showed a good balance (COMET=0.86, chrF=76.99, WER=43.75), and ElevenLabs provided similar results (COMET=0.88, chrF=77.36) with a slightly better WER (42.77%). This competitive performance is a reassuring sign for the future of speech recognition for Kazakh.

In contrast, the Whisper model, despite its popularity and availability, proved to be significantly less accurate, with WER, TER, and BLEU scores of 77.10%, 74.87%, and 13.22%, respectively. Such results highlight the challenges Whisper faces in working with the Kazakh language, particularly given its morphological complexity and dialectal diversity.

Thus, Voiser and Soyle are the most promising solutions for building Kazakh speech recognizers. Voiser is a highly accurate and robust system for commercial implementation, and Soyle is a local, open-source solution optimized for the peculiarities of Kazakh speech. GPT-4 and ElevenLabs also demonstrate excellent performance, but may be limited by licensing terms and the cost of API access for large-scale data processing. In contrast, Whisper, despite its versatility, shows insufficient suitability for building high-quality STT corpora in Kazakh without additional adaptation.

The results of evaluating the STT models on the data collected and labeled at Nazarbayev University demonstrate a clear difference in performance between the systems (see

Table 5). Notably, the Soyle model, developed by the ISSAI at Nazarbayev University, achieved the highest performance in all metrics. The model demonstrated outstanding speech recognition quality, with BLEU=74.93%, WER and TER at 18.61% each, chrF at 95.60, and a maximum COMET value of 1.23. Soyle indicates a high degree of coincidence with the reference transcription at both the formal (lexical) and semantic levels. One possible factor contributing to such high accuracy is that part of the corpus collected at the university may have been used in the training of Soyle, which gives it a significant advantage when working with this dataset. GPT-4 Transcribe performs similarly, demonstrating balanced and stable results across all metrics: WER = 36.22%, TER = 23.04%, BLEU = 53.46%, chrF = 81.15, and COMET = 1.02. GPT-4 Transcribe indicates a high ability of the model to recognize Kazakh speech even without explicit localization. However, given the closed architecture of GPT-4 and the impossibility of obtaining information about its training data, it cannot be ruled out that the model had indirect access to speech data.

ElevenLabs also achieved high results: BLEU=59.45%, WER=30.84%, chrF=88.04, COMET=1.13, and an especially low TER=17.27%, indicating the closeness of word forms and word order to the standard. These data confirm that the system demonstrates competitive recognition quality, especially in the context of formally accurate transcription.

The Voiser model showed slightly more modest results on NU data, yet still decent results (chrF=84.51, COMET=1.05, BLEU=47.04%), inferior to ElevenLabs and GPT-4 in accuracy, but still surpassing the baseline of most universal models. It can be considered a balanced solution with moderate accuracy and availability via API.

In turn, Whisper, despite its vast popularity as an open-source model from OpenAI, demonstrated the worst results on local Kazakh data: WER = 60.55%, TER = 54.36%, and COMET = 0.30. These values indicate the low accuracy of Whisper in processing Kazakh speech, which can be attributed to both the insufficient amount of Kazakh data in the training corpus and the model’s limited adaptation to the features of Turkic languages.

Overall, Soyle, GPT-4 Transcribe, and ElevenLabs demonstrated the highest performance for Kazakh speech, with Soyle showing particularly high performance, likely due to the partial representation of the Nazarbayev University audio corpus in the training set. This highlights the importance of localized data when developing STT systems for resource-constrained languages. Whisper, in turn, requires additional adaptation or retraining on specialized Kazakh datasets to achieve a comparable level of performance.

After the transcription was obtained from the original audio using STT models, this text was voiced using TTS to check how well the original speech signal can be reconstructed from the text. This allowed us to perform a reverse check: how well the STT + TTS combination works and how much the synthesized speech differs from the original.

For a comprehensive comparative analysis of the quality of speech synthesis in the Kazakh language, data published on the 24.kz portal were utilized and analyzed using five primary metrics: STOI, PESQ, MCD, LSD, and DNSMOS (see

Table 6). These metrics enable an objective and comprehensive assessment of both the acoustic accuracy and the subjective perception of synthesized speech, underscoring the importance of our research in the fields of speech synthesis and linguistics.

According to the STOI indicator, which reflects speech intelligibility, all models demonstrate similar values in the range of 0.09–0.11. The best value is observed in the TurkicTTS model (0.11), which indicates its relative advantage in intelligibility compared to other systems.

PESQ, as a metric of objective sound quality, varies from 1.09 (KazakhTTS2) to 1.16 (TurkicTTS), demonstrating a generally low level of perceived quality of synthesized speech. However, TurkicTTS and OpenAI TTS show better results, which may indicate a more natural sound and lower distortion levels.

As for MCD, which evaluates the acoustic closeness of synthesized speech to the reference, the lowest value is recorded by OpenAI TTS (123.44), indicating high accuracy in spectral characteristics. At the opposite extreme are Elevenlabs and KazakhTTS2 with MCD above 150, which may indicate significant distortions in the spectrum.

The LSD metric achieved the lowest score of 1.03 on OpenAI TTS. KazakhTTS2 performed well with an LSD of 1.11, while TurkicTTS had a moderate LSD of 1.06, suggesting good spectral accuracy. At the same time, MMS and Elevenlabs had relatively higher LSDs of 1.15 and 1.34.

The DNSMOS metric, which reflects a subjective quality assessment based on neural network analysis, demonstrates the most significant variability among models. KazakhTTS2 leads with a score of 8.79, which may indicate a high perceived naturalness of synthesized speech, despite less impressive objective indicators. OpenAI TTS (7.43) and Elevenlabs (6.13) also have high values.

Summarizing the results, it can be noted that TurkicTTS demonstrates the most balanced values for objective metrics (STOI, PESQ, MCD), while KazakhTTS2 stands out from the others in terms of subjective perception of speech quality (DNSMOS).

The results of evaluating TTS models on Kazakh audio using metrics, conducted on the Nazarbayev University audio corpus, demonstrate noticeable differences in the quality of synthesized speech between the systems under consideration (

Table 7). The evaluation was carried out using five metrics: STOI, PESQ, MCD, LSD, and DNSMOS, each of which reflects different aspects of quality: from intelligibility and spectral similarity to human perceptual perception. The best results in DNSMOS - 8.96, indicating high subjective sound quality, were achieved by the KazakhTTS2 model, specifically developed for the Kazakh language. In addition, this model achieved the lowest PESQ value (1.07) and one of the lowest STOI scores (0.12) and LSD (1.12), indicating limited intelligibility with a high overall perception of quality. However, the key achievement of KazakhTTS2 is a significantly lower MCD (137.03) compared to MMS and TurkicTTS, indicating a high spectral proximity of the synthesized signal to the reference one. This indicates that despite relatively weak intelligibility indicators, KazakhTTS2 demonstrates a good approximation to the original sound, which is especially important in natural synthesis tasks.

OpenAI TTS demonstrated balanced performance, with STOI (0.14), LSD (1.19), and PESQ (1.14) values comparable to the best. In contrast, the MCD was only 117.11, the lowest among all models, indicating high spectral accuracy. DNSMOS 7.04 further confirmed the high subjective quality of synthesis. This balanced performance positions OpenAI TTS as one of the most reliable models, offering a universal approach without explicit adaptation to the Kazakh language.

The TurkicTTS model, designed for Turkic languages, showcased the highest STOI (0.15), indicating superior speech intelligibility among all systems, and a PESQ score of 1.14, comparable to that of OpenAI TTS. However, its MCD (145.49) and DNSMOS (6.39) scores are lower than those of KazakhTTS2 and OpenAI, suggesting less accurate spectrum reproduction and slightly less natural speech perception. Despite this, the model exhibits high stability in the basic parameters, hinting at its promising potential for further adaptation and development.

ElevenLabs demonstrated moderate performance with MCD (139.75), PESQ (1.08), STOI (0.13), and DNSMOS (6.38), but it got the highest LSD score of 1.29. The balance and consistently high quality of this model confirms its applicability to Kazakh speech generation tasks in applied products. Its commercial availability and support for multilingual synthesis further enhance its practicality and potential for widespread use.

The MMS model yielded the lowest quality results, with STOI (0.12) and PESQ (1.11) at the lower end of the range, a moderate LSD score of 1.20, and MCD of 148.40 — the highest among all models. Despite the acceptable DNSMOS (3.91), this model does not provide satisfactory compliance in either intelligibility or spectral matching, indicating its limited suitability for Kazakh speech synthesis without additional training.

Thus, the models of most significant interest for further use are KazakhTTS2 (if high subjective quality is required), OpenAI TTS (if a balance between accuracy and versatility is desired), and TurkicTTS (if intelligibility is a priority). The choice of model should be determined depending on the system’s priorities: intelligibility, naturalness of sound, or spectral accuracy.

5. Conclusion and Future Work

The use of TTS after STT in this experiment represents a crucial stage in a comprehensive assessment of speech technology quality. It enables us to analyze the accuracy of the full cycle of speech signal conversion — from audio to text and back (audio → text → audio) — and identify accumulated distortions at each stage. This approach enables the assessment of TTS systems not only in terms of compliance with the generated text, but also in terms of the approximation of synthesized speech to the original sound in terms of both acoustic and perceptual characteristics. In addition, it enables us to determine the extent to which the system can reproduce the original speech flow, including intonation and prosodic features, rather than merely generating a formally correct voiceover of the text.

In this study, various STT and TTS systems were evaluated using a test dataset, and the most suitable system was chosen based on predefined criteria, including availability, speech recognition accuracy, speech synthesis quality, and efficiency. Thus, the integration of TTS after STT extends beyond the technical procedure and serves as a crucial tool for a comprehensive evaluation of the reliability and realism of speech systems under conditions of limited training data.

Through a meticulous evaluation methodology, the optimal models for STT and TTS tasks in the Kazakh language were selected. The selection was based on a range of quality metrics, including WER, TER, chrF, COMET, and BLEU for STT, and MCD, PESQ, STOI, LSD, and DNSMOS for TTS, with a focus on accuracy, intelligibility, and perceptual quality.

In the task of automatic speech recognition of Kazakh, the chosen GPT-4 Transcribe model demonstrated the best results among the general-purpose models not trained on the target corpus. The model’s high accuracy with WER = 36.22%, TER = 23.04%, as well as significant chrF (81.15) and COMET (1.02) values, reaffirm its potential as a strong candidate for STT tasks in scalable or multilingual applications.

It should be noted that, despite demonstrating the best metrics among all tested systems (WER = 18.61%, chrF = 95.60%, COMET = 1.23), the Soyle model was not selected as the final solution. This is because some of the data used in the experiment may have been part of its training set, potentially leading to an overestimation of the model’s actual accuracy on the target test corpus. This could reduce the validity of its choice as a universal tool for general speech recognition tasks, as it may not perform as well on unseen data.

The OpenAI TTS model was selected for Kazakh speech synthesis (TTS), demonstrating the best balance between spectral accuracy and subjective sound quality. The model achieved the lowest MCD value (117.11), as well as high PESQ (1.14) and DNSMOS (7.04) scores, indicating high-quality acoustic implementation and a positive perception of the synthesized speech. The STOI value (0.14) also confirms speech intelligibility, making OpenAI TTS a suitable choice for a wide range of applications, including speech generation in educational settings, media content, and dialog systems in the Kazakh language.

In future work, we plan to focus on collecting parallel audio data between Kazakh and other Turkic languages. The creation of parallel corpora is essential given the current shortage of parallel speech data for Turkic languages, which is critical for developing and testing speech-to-speech systems (STS). The development of this database will address two important problems: it will provide a foundational platform for creating speech models in various languages and will aid in advancing the development of digital linguistic technologies in the Central Asian region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.; methodology, A.K. and V.K.; software, A.K. and V.K.; experiments, A.K. and V.K.; validation, A.K. and V.K.; formal analysis, B.A. and D.T.; investigation, A.K.; resources, A.K. and V.K.; data curation, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K. , V.K., and B.A; writing—review and editing, A.K. and V.K.; visualization, V.K.; supervision, A.K.; project administration, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the grant project «Study of automatic generation of parallel speech corpora of Turkic languages and their use for neural models» (grant number IRN AP AP23488624) of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASR |

Automatic speech recognition |

| TTS |

Text-to-speech |

| STT |

Speech-to-Text |

| E2E |

End-to-End |

| WER |

Word error rates |

| TER |

Translation Edit Rate |

| BLEU |

Bilingual Evaluation Understudy |

| chrF |

CHaRacter-level F-score |

| LoRA |

Low-Rank Adaptation |

| CER |

Character error rate |

| KSC |

Kazakh Speech Corpus |

| MT |

Machine translation |

| HMM |

Hidden Markov Models |

| PESQ |

Perceptual Evaluation of Speech Quality |

| STOI |

Short-Time Objective Intelligibility |

| USM |

Universal Speech Model |

| USC |

Uzbek Speech Corpus |

| MCD |

Mel Cepstral Distortion |

| DNSMOS |

Deep Noise Suppression Mean Opinion Score |

| DNS |

Deep Noise Suppression |

| MOS |

Mean Opinion Score |

| MSE |

Mean square error |

| MMS |

Massively Multilingual Speech |

| MFCC |

Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients |

| ISSAI |

Institute of Intelligent Systems and Artificial Intelligence |

| NU |

Nazarbayev University |

| CTC |

Connectionist temporal classification |

| KSD |

Kazakh Speech Dataset |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| COMET |

Crosslingual Optimized Metric for Evaluation of Translation |

| RNN-T |

Recurrent neural network-transducer |

| LSTM |

Long Short-Term Memory |

| UzLM |

Uzbek language model |

| STS |

Speech-to-speech |

| LID |

Language identifier |

| DL |

Deep Learning |

| IPA |

International Phonetic Alphabet |

| API |

Application Programming Interface |

| GPT |

Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| WebRTC |

Web Real-Time Communication |

| MOS-LQO |

Mean Opinion Score - Listening Quality Objective |

| HiFi-GAN |

Generative Adversarial Networks for Efficient and High Fidelity Speech Synthesis |

| WaveGAN |

Generative adversarial network for unsupervised synthesis of raw-waveform audio |

References

- Bekarystankyzy, A.; Mamyrbayev, O.; Mendes, M.; et al. Multilingual end-to-end ASR for low-resource Turkic languages with common alphabets. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadyrbek, N.; Mansurova, M.; Shomanov, A.; Makharova, G. The Development of a Kazakh Speech Recognition Model Using a Convolutional Neural Network with Fixed Character Level Filters. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2023, 7, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeshpanov, R.; Mussakhojayeva, S.; Khassanov, Y. Multilingual Text-to-Speech Synthesis for Turkic Languages Using Transliteration. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH; 2023; pp. 5521–5525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussakhojayeva, S.; Janaliyeva, A.; Mirzakhmetov, A.; Khassanov, Y.; Varol, H.A. KazakhTTS: An Open-Source Kazakh Text-to-Speech Synthesis Dataset. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH; 2021; pp. 2786–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, S.; Agrawal, H.; Jena, S.; Gite, S.; Bachute, M.; Pradhan, B.; Assiri, M. Challenges and Limitations in Speech Recognition Technology: A Critical Review of Speech Signal Processing Algorithms, Tools and Systems. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2023, 135, 1053–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, A.; Zhang, Y.; Ramabhadran, B.; et al. Speech recognition with augmented synthesized speech. In Proceedings of the IEEE ASRU 2019; pp. 996–1002.

- Zhang, C.; Li, B.; Sainath, T.; et al. Streaming end-to-end multilingual speech recognition with joint language identification. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, W.; Qin, J.; et al. Google USM: Scaling automatic speech recognition beyond 100 languages. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.01037. [Google Scholar]

- Fendji, J.L.K.E.; Tala, D.C.M.; Yenke, B.O.; Atemkeng, M. Automatic Speech Recognition Using Limited Vocabulary: A Survey. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metze, F.; Gandhe, A.; Miao, Y.; et al. Semi-supervised training in low-resource ASR and KWS. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2015; pp. 5036–5040. [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Maimaitiyiming, Y.; Nijat, M.; et al. Automatic Speech Recognition for Uyghur, Kazakh, and Kyrgyz: An Overview. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhamadiyev, A.; Mukhiddinov, M.; Khujayarov, I.; Ochilov, M.; Cho, J. Development of Language Models for Continuous Uzbek Speech Recognition System. Sensors 2023, 23, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veitsman, Y.; Hartmann, M. Recent Advancements and Challenges of Turkic Central Asian Language Processing. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Language Models for Low-Resource Languages; ACL: Abu Dhabi, UAE, 2025; pp. 309–324. [Google Scholar]

- Oyucu, S. A Novel End-to-End Turkish Text-to-Speech (TTS) System via Deep Learning. Electronics 2023, 12, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, H.; Turan, A.K.; Koçak, C.; Ulaş, H.B. Implementation of a Whisper Architecture-Based Turkish ASR System and Evaluation of Fine-Tuning with LoRA Adapter. Electronics 2024, 13, 4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaev, M.; Mussakhojayeva, S.; Khujayorov, I.; et al. USC: An open-source Uzbek speech corpus and initial speech recognition experiments. In Speech and Computer. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer, 2021; pp. 437–447. [Google Scholar]

- Kozhirbayev, Z. Kazakh Speech Recognition: Wav2vec2.0 vs. Whisper. J. Adv. Inf. Technol. 2023, 14, 1382–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khassanov, Y.; Mussakhojayeva, S.; Mirzakhmetov, A.; et al. A Crowdsourced Open-Source Kazakh Speech Corpus and Initial Speech Recognition Baseline. Proceedings of EACL 2021; pp. 697–706.

- Kozhirbayev, Z.; Islamgozhayev, T. Cascade Speech Translation for the Kazakh Language. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orken, M.; Dina, O.; Keylan, A.; et al. A study of transformer-based end-to-end speech recognition system for Kazakh language. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapyshev, G.; Nurtas, M.; Altaibek, A. Speech recognition for Kazakh language: a research paper. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 231, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussakhojayeva, S.; et al. Noise-Robust Multilingual Speech Recognition and the Tatar Speech Corpus. In Proceedings of the ICAIIC 2024, Osaka, Japan; 2024; pp. 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussakhojayeva, S.; Khassanov, Y.; Varol, H.A. KSC2: An industrial-scale open-source Kazakh speech corpus. Proceedings of INTERSPEECH 2022; pp. 1367–1371.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; et al. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, A.; Qin, J.; Chiu, C.C.; et al. Conformer: Convolution-augmented Transformer for Speech Recognition. Proceedings of INTERSPEECH 2020; pp. 5036–5040. [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.; Xu, T.; et al. Robust Speech Recognition via Large-Scale Weak Supervision. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.04356. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, S.; Hori, T.; Karita, S.; et al. ESPnet: End-to-End Speech Processing Toolkit. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.00015. [Google Scholar]

- Conneau, A.; Khandelwal, K.; Goyal, N.; et al. Unsupervised Cross-lingual Representation Learning at Scale. Proceedings of ACL 2020; pp. 8440–8451.

- Hu, E.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; et al. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.09685. [Google Scholar]

- ESPnet Toolkit. Available online: https://github.com/espnet/espnet (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Ghoshal, A.; Boulianne, G.; Burget, L.; et al. The Kaldi speech recognition toolkit. In Proceedings of the ASRU; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, T.; et al. Transformers: State-of-the-art Natural Language Processing. Proceedings of EMNLP 2020; pp. 38–45. [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; et al. Natural TTS synthesis by conditioning WaveNet on mel spectrogram predictions. In ICASSP 2018, pp. 4779–4783. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; et al. FastSpeech 2: Fast and High-Quality End-to-End Text to Speech. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.04558. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, J.; et al. HiFi-GAN: Generative Adversarial Network for Efficient and High Fidelity Speech Synthesis. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.05646. [Google Scholar]

- Common Voice. Available online: https://commonvoice.mozilla.org/ru/datasets (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- KazakhTTS. Available online: https://github.com/IS2AI/Kazakh_TTS (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Kazakh Speech Corpus. Available online: https://www.openslr.org/102/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Kazakh Speech Dataset. Available online: https://www.openslr.org/140/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- GPT-4o-transcribe (OpenAI). Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/models/gpt-4o-transcribe (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Whisper. Available online: https://github.com/openai/whisper (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Soyle. Available online: https://github.com/IS2AI/Soyle (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- ElevenLabs Scribe. Available online: https://elevenlabs.io/docs/capabilities/speech-to-text (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Voiser. Available online: https://voiser.net/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.J. BLEU: a Method for Automatic Evaluation of Machine Translation. Proceedings of ACL 2002; pp. 311–1040.

- Gillick, L.; Cox, S. Some Statistical Issues in the Comparison of Speech Recognition Algorithms. In ICASSP 1989, 1, 532–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snover, M.; Dorr, B.; Schwartz, R.; Micciulla, L.; Makhoul, J. A Study of Translation Edit Rate with Targeted Human Annotation. In Proceedings of AMTA 2006. https://www.cs.umd.edu/~snover/pub/amta06_ter_final.pdf.

- Popović, M. chrF: character n-gram F-score for automatic MT evaluation. Proceedings of WMT 2015; pp. 392–3049.

- Rei, R.; Farinha, A.C.; Martins, A.F.T. COMET: A Neural Framework for MT Evaluation. Proceedings of EMNLP 2020; pp. 2685–2702.

- Kubichek, R. Mel-cepstral distance measure for objective speech quality assessment. In Proceedings of the IEEE Pacific Rim Conf. 1993; 1, pp. 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rix, A.W.; Beerends, J.G.; Hollier, M.P.; Hekstra, A.P. Perceptual evaluation of speech quality (PESQ). In ICASSP 2001, 2, 749–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taal, C.H.; Hendriks, R.C.; Heusdens, R.; Jensen, J. An Algorithm for Intelligibility Prediction of Time–Frequency Weighted Noisy Speech. IEEE Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2011, 19, 2125–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.; et al. DNSMOS: A Non-Intrusive Perceptual Objective Speech Quality Metric to Evaluate Noise Suppressors. In Proceedings of the ICASSP; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MMS (Massively Multilingual Speech). Available online: https://github.com/facebookresearch/fairseq/tree/main/examples/mms (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- TurkicTTS. Available online: https://github.com/IS2AI/TurkicTTS (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- KazakhTTS2. Available online: https://github.com/IS2AI/Kazakh_TTS (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- ElevenLabs TTS. Available online: https://elevenlabs.io/docs/capabilities/text-to-speech (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- OpenAI TTS. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/text-to-speech (accessed on 30 June 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).