Submitted:

27 July 2025

Posted:

28 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

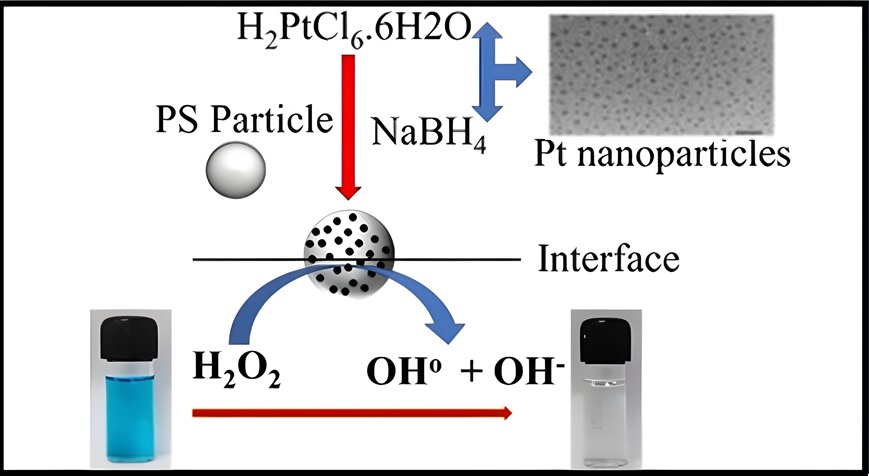

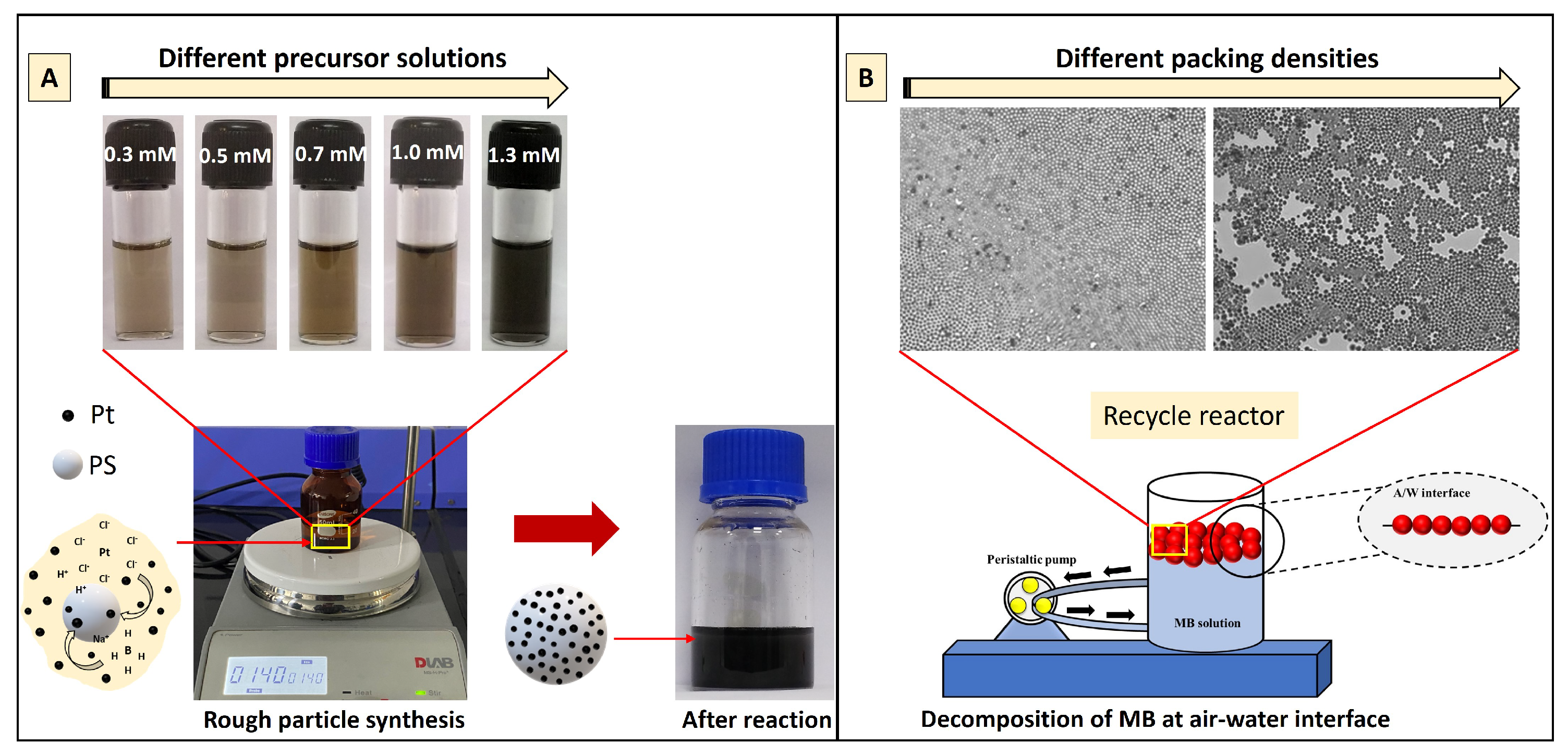

2.2.1. Synthesis of Pt Nanoparticles and Rough Particles

2.2.2. Discoloration of MB Using Rough Particles at Air-Water Interface

2.2.3. ANN Methodology

2.2.4. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

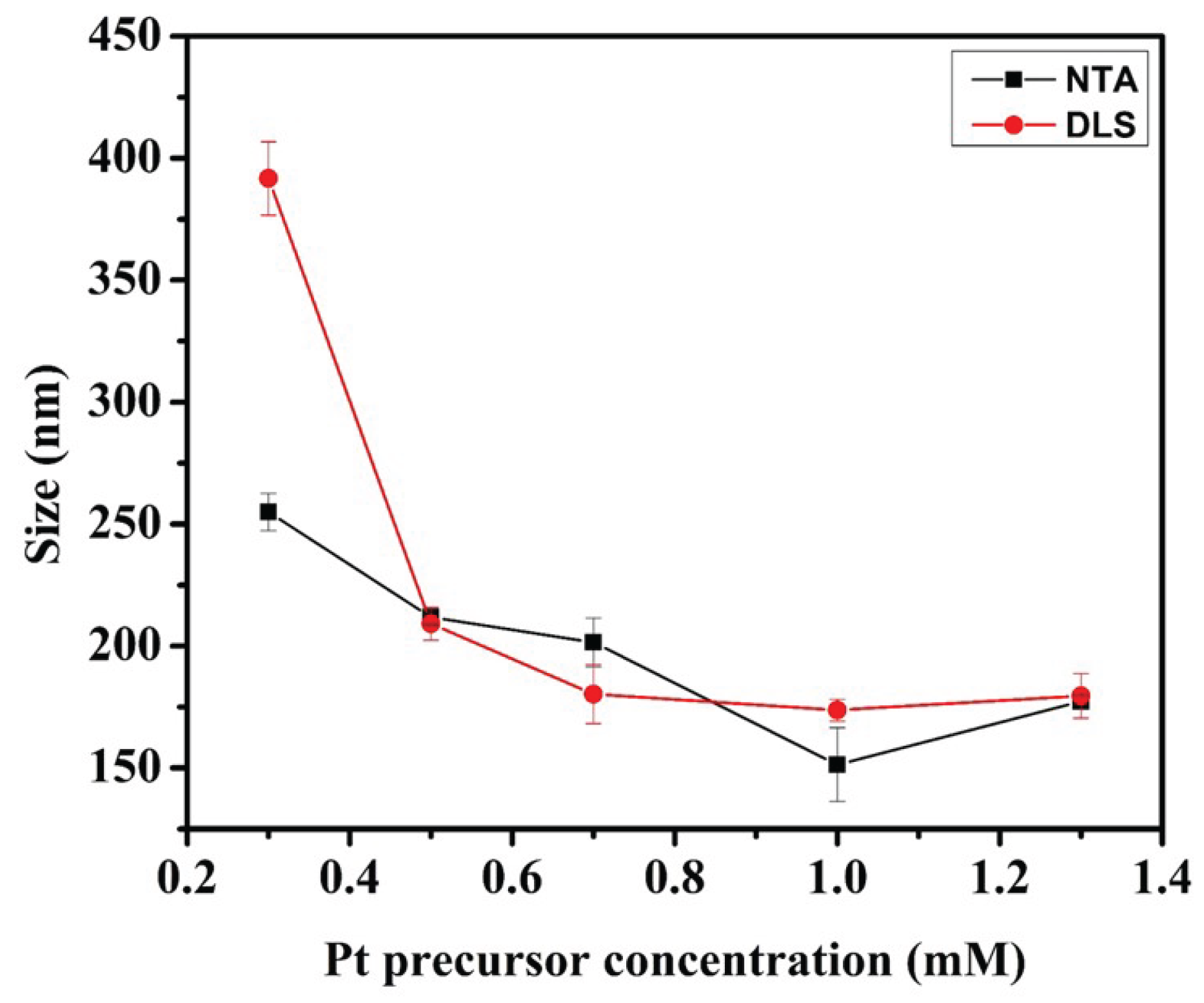

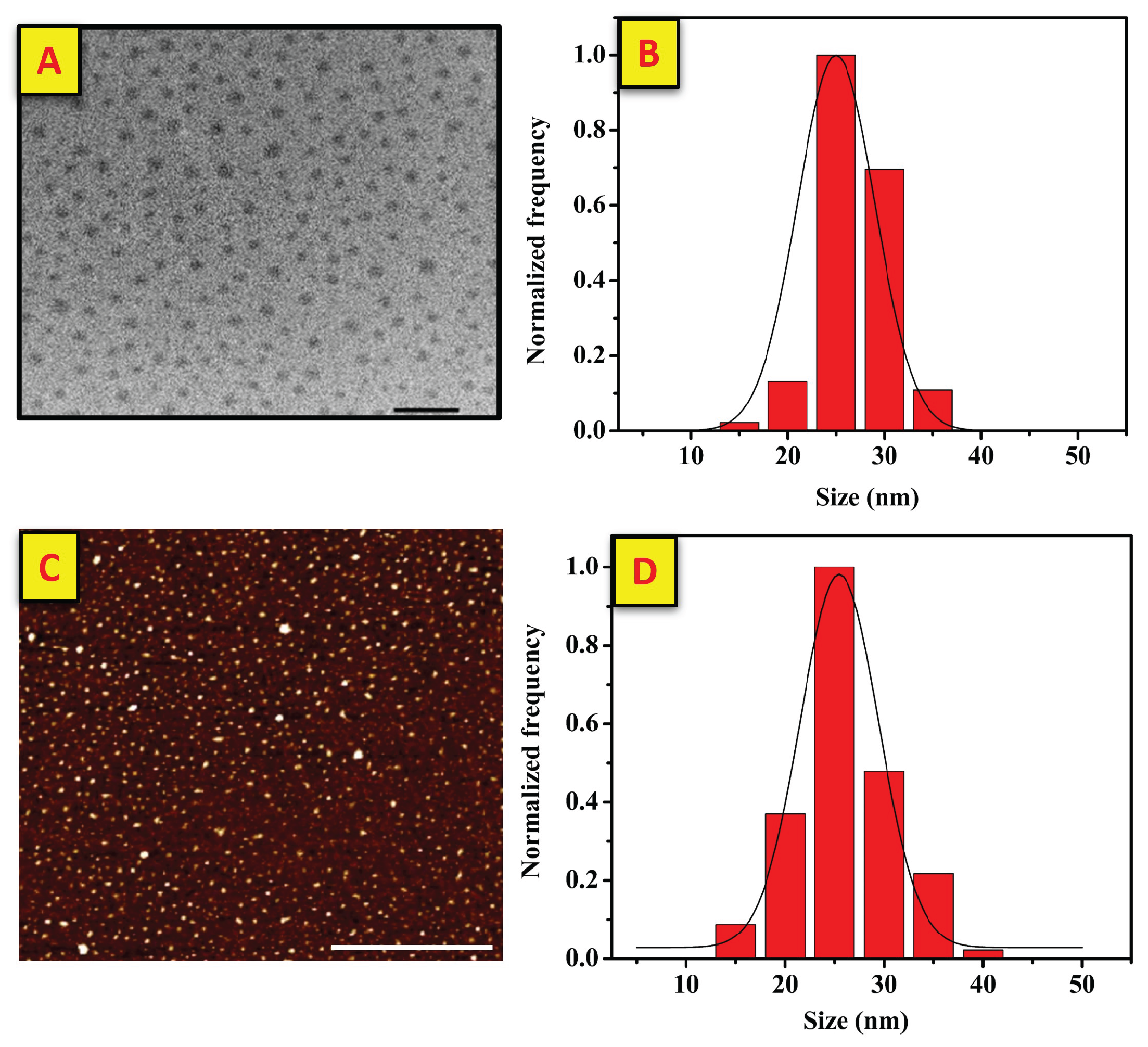

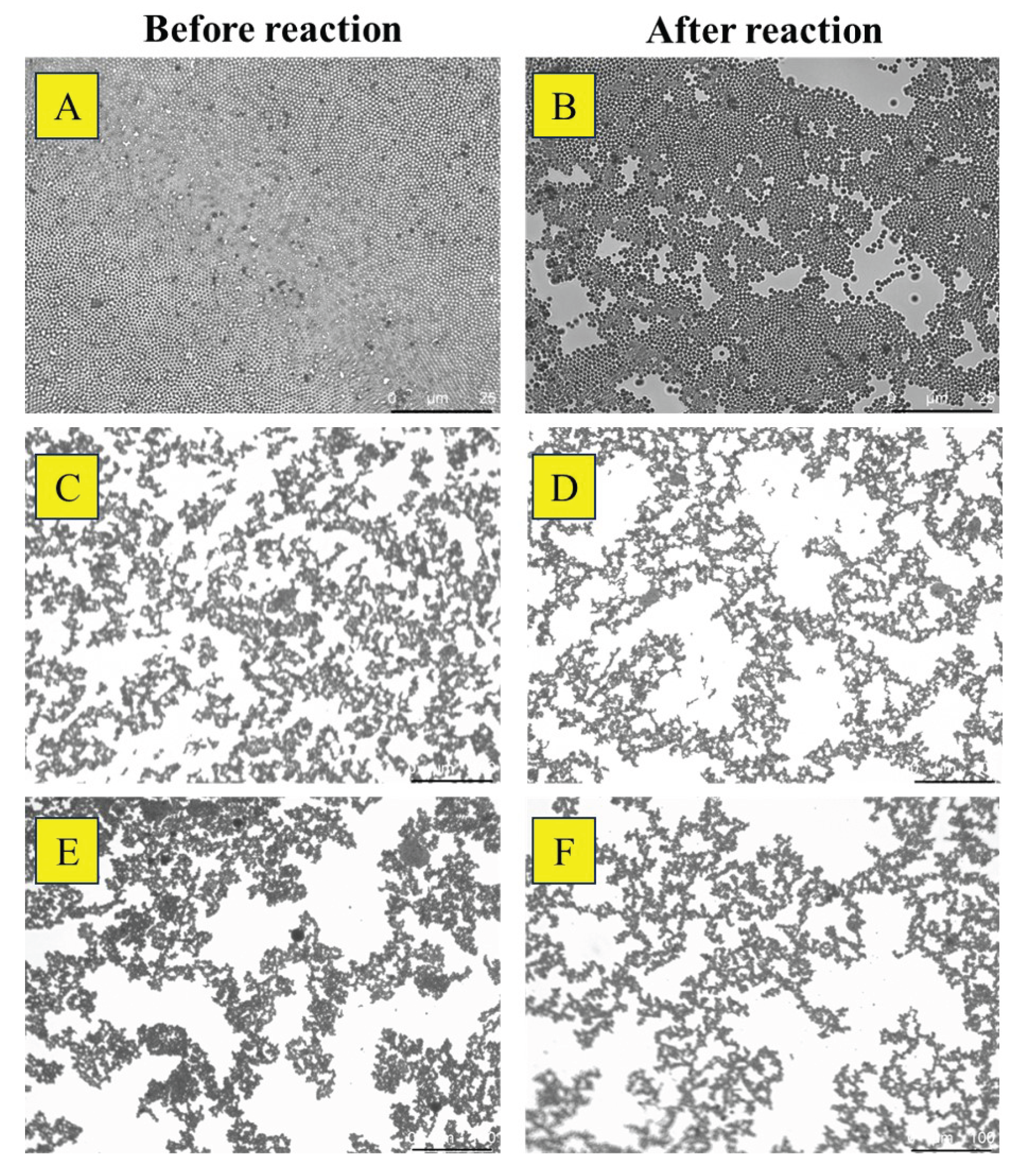

3.1. Characterization of Pt and Rough Particles

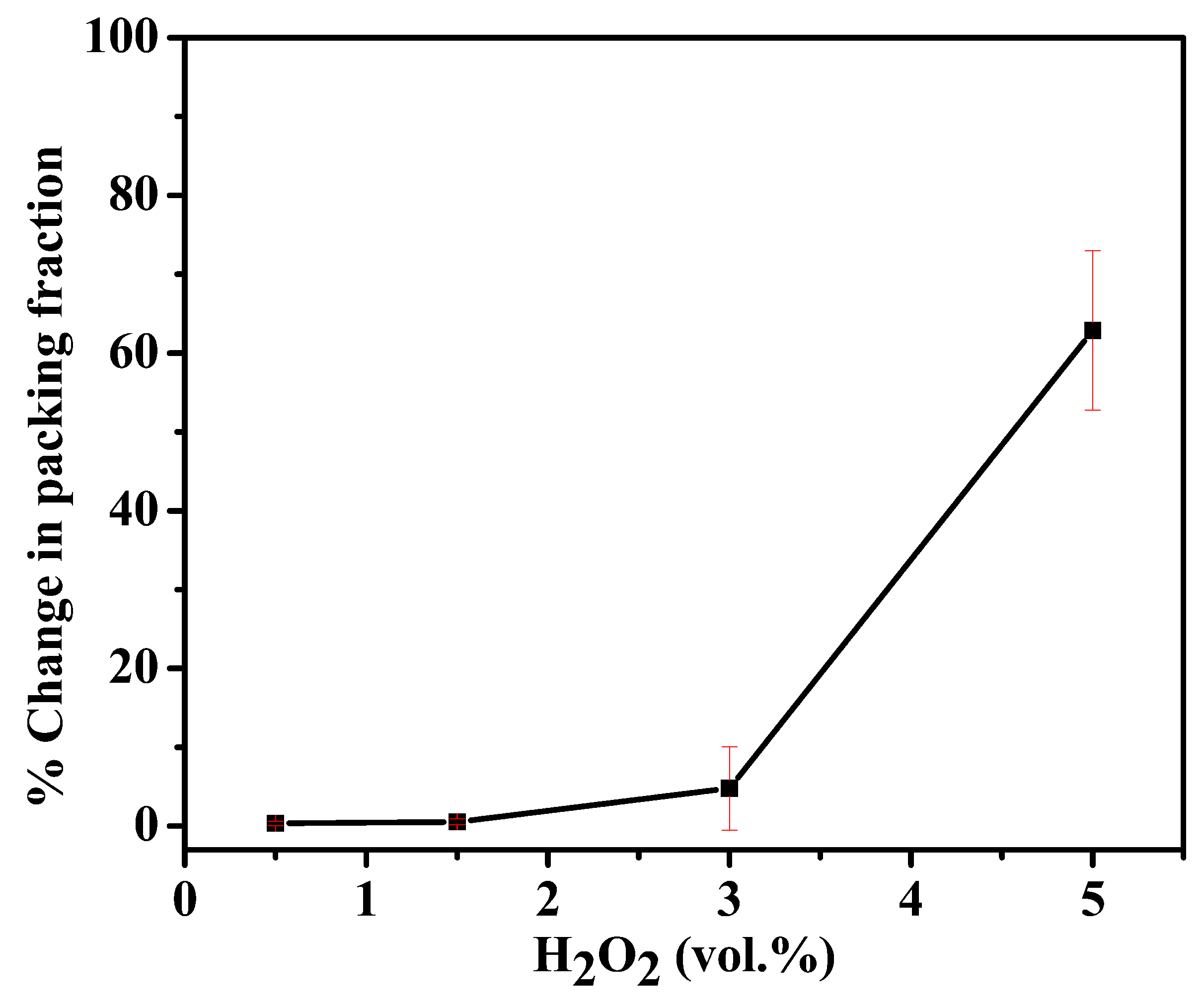

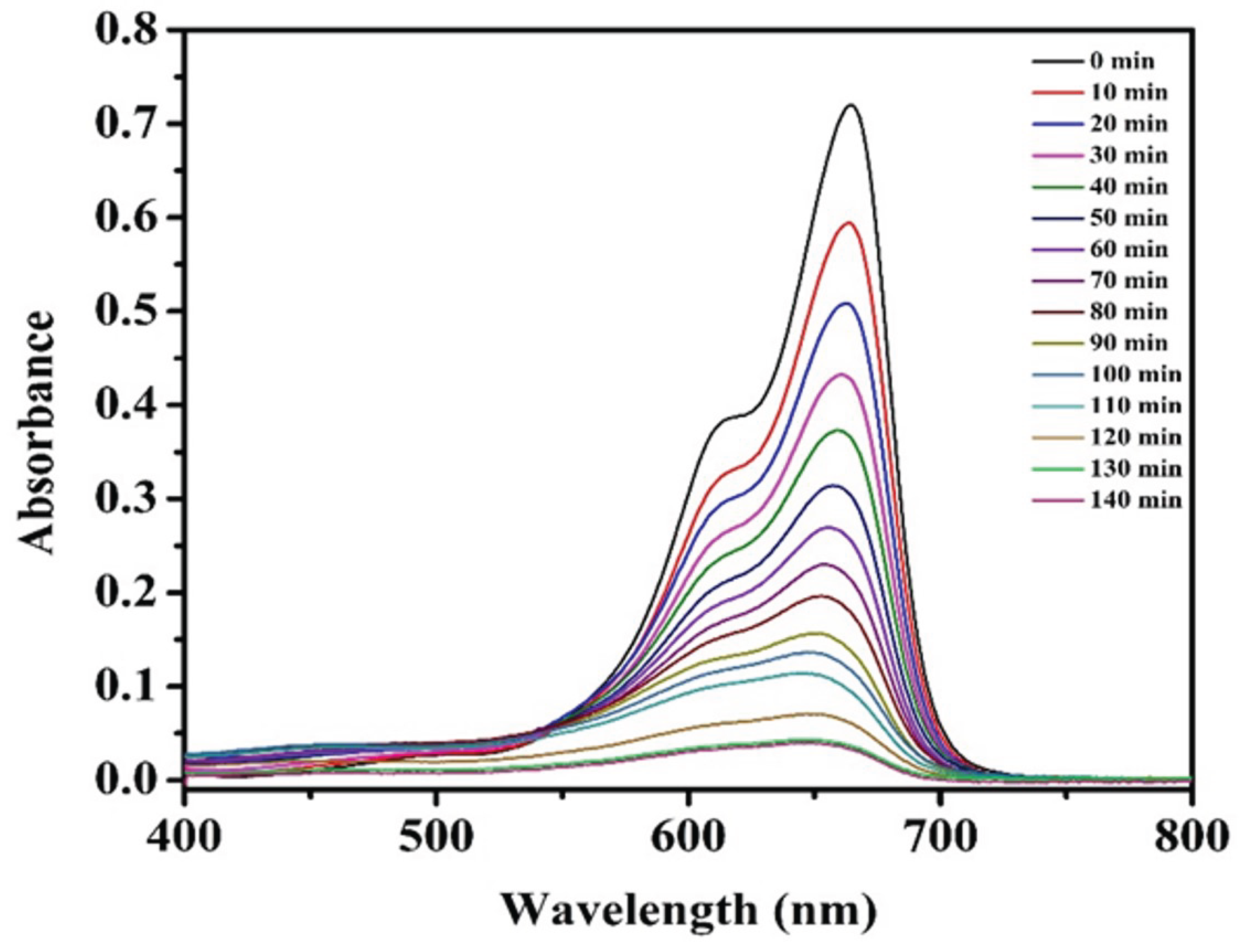

3.2. Discoloration of MB at Air-Water Interface

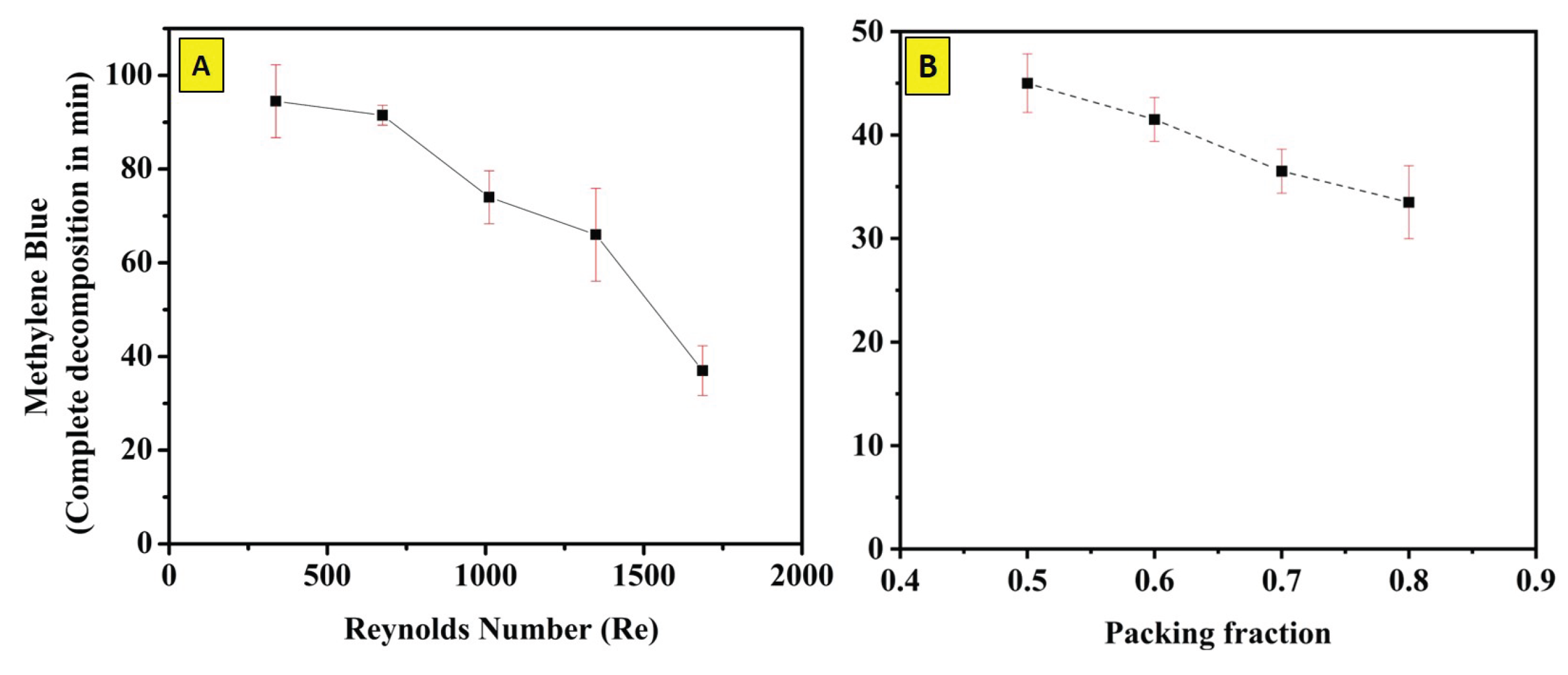

3.3. The Effect of Circulation Speed on MB Degradation

3.4. Effect of Packing Fraction () on the MB Degradation

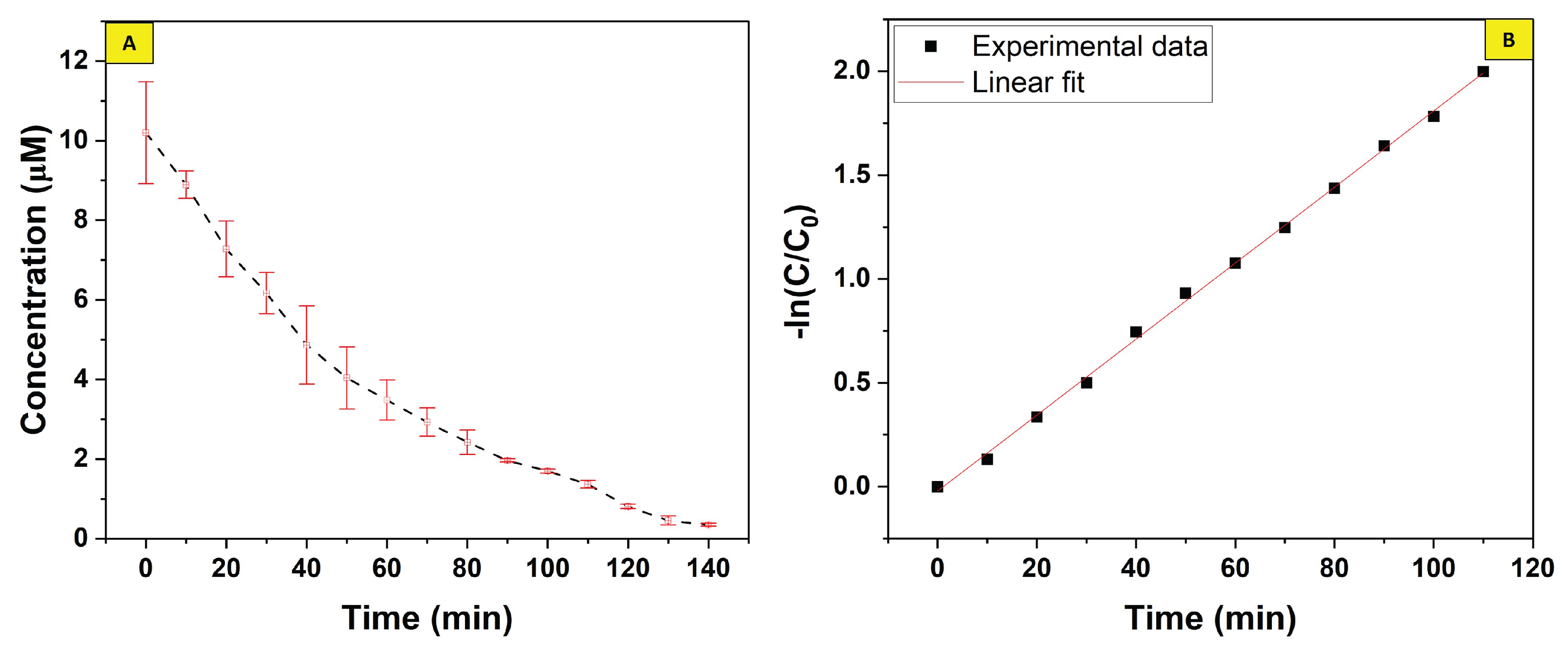

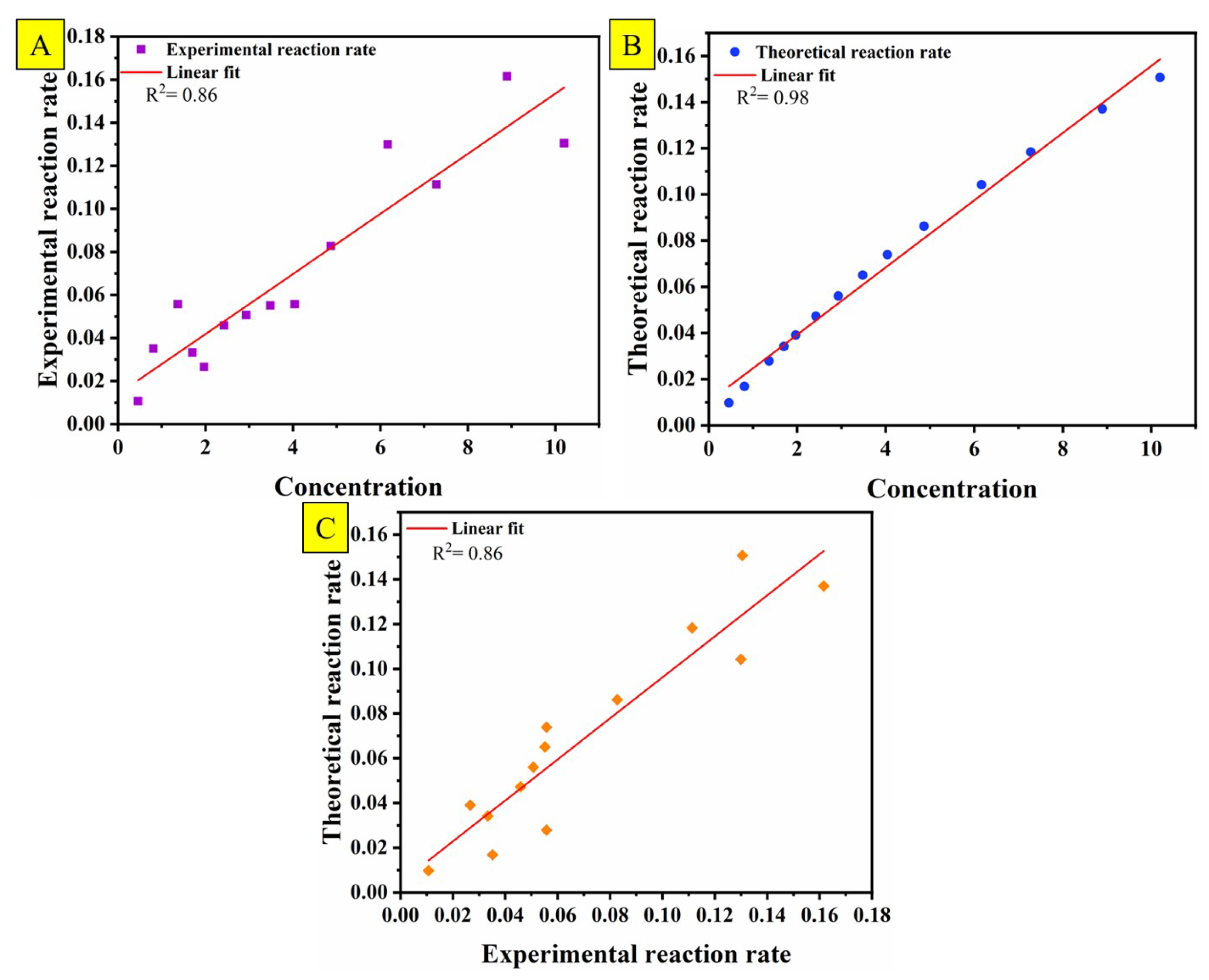

4. Degradation Kinetics

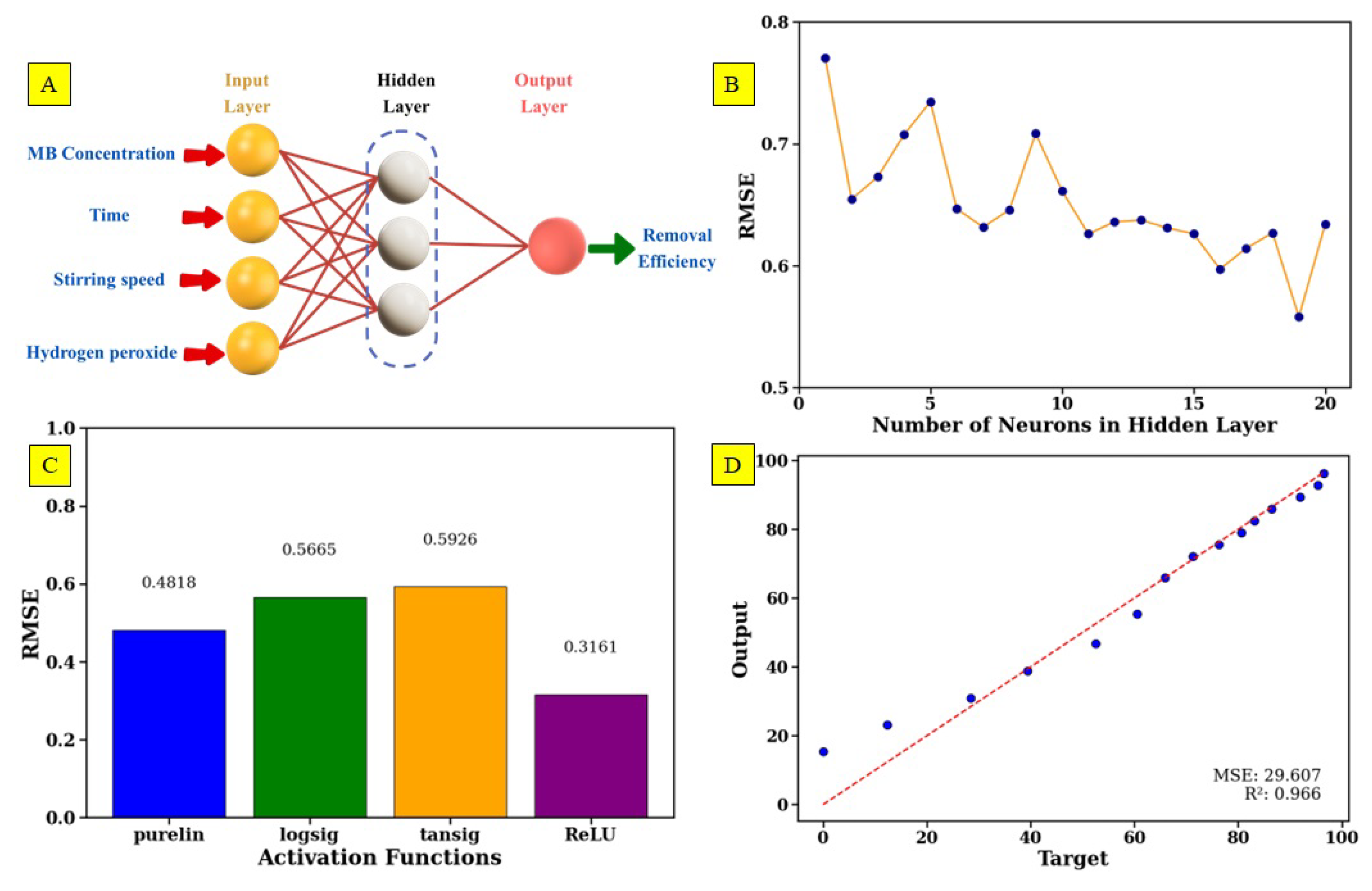

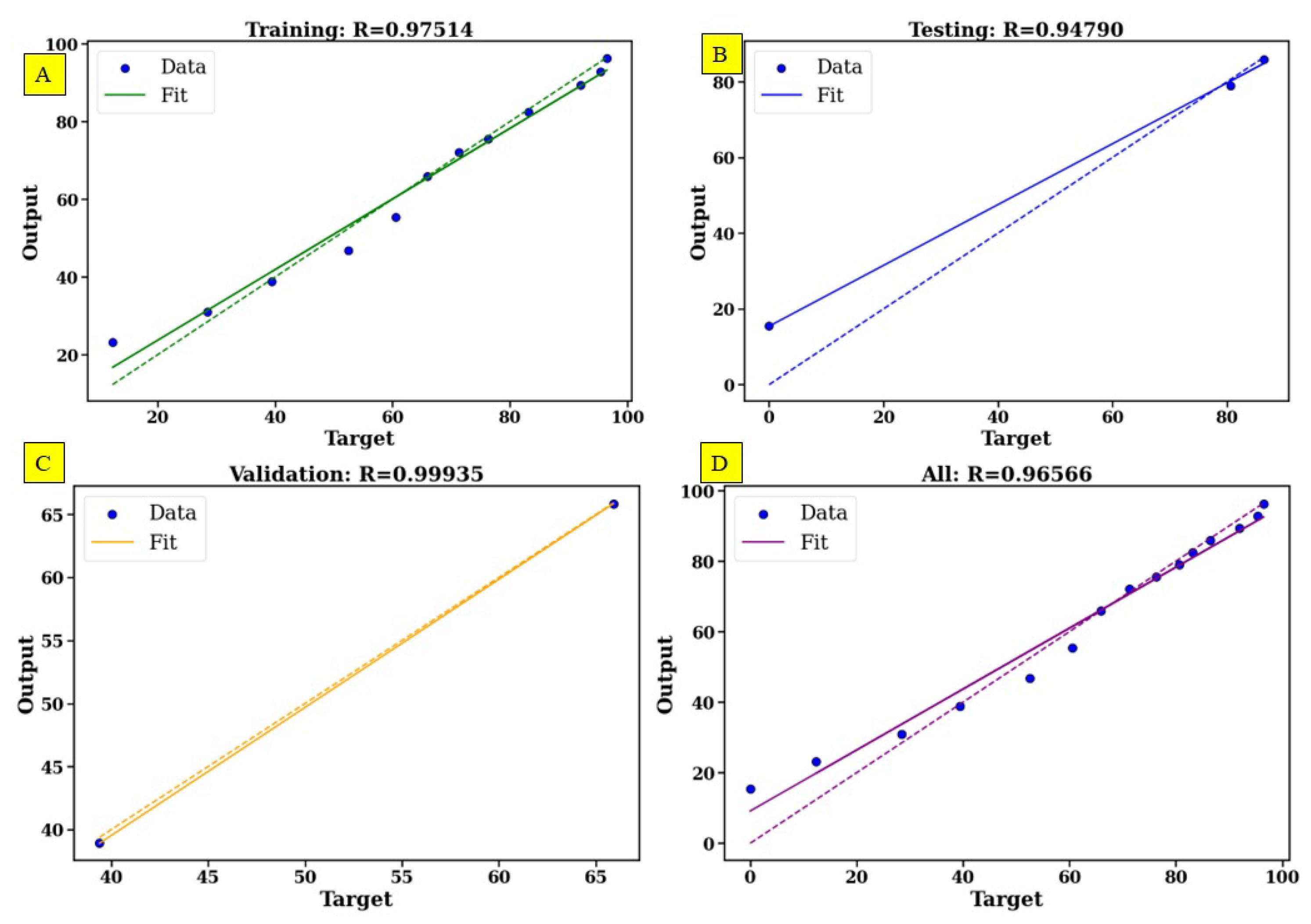

5. ANN Modeling of MB Removal

6. Future Scope and Limitations

7. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Data Availability Statement

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shimizu, N.; Ogino, C.; Dadjour, M.F.; Murata, T. Sonocatalytic degradation of methylene blue with tio2 pellets in water. Ultrasonics sonochemistry 2007, 14, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElShafei, G.M.; Yehia, F.; Dimitry, O.; Badawi, A.; Eshaq, G. Ultrasonic assisted-fenton-like degradation of nitrobenzene at neutral ph using nanosized oxides of fe and cu. Ultrasonics sonochemistry 2014, 21, 1358–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, A.; Dianti, L.R.; Mayangsari, N.E.; Widiana, D.R.; Dermawan, D. Removal of methylene blue using heterogeneous fenton process with fe impregnated kepok banana (musa acuminate l.) peel activated carbon as catalyst. Inorganic Chemistry Communications 2023, 152, 110715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivisatos, P. The use of nanocrystals in biological detection. Nature biotechnology 2004, 22, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, Y. Nanocrystals from solutions: catalysts. Chemical Society Reviews 2014, 43, 2112–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, C.; Liu, Z.; Huang, J.; Wu, M.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y. Pt-based nanocrystal for electrocatalytic oxygen reduction. Advanced Materials 2019, 31, 1808115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantatos, G.; Sargent, E.H. Nanostructured materials for photon detection. Nature nanotechnology 2010, 5, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, K.M.; Hafner, J.H. Localized surface plasmon resonance sensors. Chemical reviews 2011, 111, 3828–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, S.; Link, S.; Halas, N.J. Nano-optics from sensing to waveguiding. Nature photonics 2007, 1, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenderink, A.F.; Alu, A.; Polman, A. Nanophotonics: Shrinking light-based technology. Science 2015, 348, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, L.N.; Kang, J.; Ning, C.-Z.; Yang, P. Nanowires for photonics. Chemical reviews 2019, 119, 9153–9169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheshtawy, H.S.; Shoueir, K.R.; El-Kemary, M.; et al. Activated h2o2 on ag/sio2–srwo4 surface for enhanced dark and visible-light removal of methylene blue and p-nitrophenol. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2020, 842, 155848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Shekhar, C.; Mondal, T.; Sabapathy, M. Rapid removal of methylene blue and tetracycline by rough particles decorated with pt nanoparticles. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 2024, 26, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.; Delgado, L.; Torà, J.A.; Casals, E.; González, E.; Puntes, V.; Font, X.; Carrera, J.; Sánchez, A. Effect of cerium dioxide, titanium dioxide, silver, and gold nanoparticles on the activity of microbial communities intended in wastewater treatment. Journal of hazardous materials 2012, 199, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaegi, R.; Voegelin, A.; Sinnet, B.; Zuleeg, S.; Hagendorfer, H.; Burkhardt, M.; Siegrist, H. Behavior of metallic silver nanoparticles in a pilot wastewater treatment plant. Environmental science & technology 2011, 45, 3902–3908. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, A.; Mihaly-Cozmuta, A.; Nicula, C.; Mihaly-Cozmuta, L.; Jastrzebska, A.; Olszyna, A.; Baia, L. Uv light-assisted degradation of methyl orange, methylene blue, phenol, salicylic acid, and rhodamine b: photolysis versus photocatalyis. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 2017, 228, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, H.A.; Khaleefa, S.A.; Basheer, M.I. Photolysis of methylene blue dye using an advanced oxidation process (ultraviolet light and hydrogen peroxide). Journal of Engineering and Sustainable Development 2021, 25, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikhlaqa, A.; Javedb, F.; Niaza, A.; Munirc, H.M.S.; Qid, F. Combined uv catalytic ozonation process on iron loaded peanut shell ash for the removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution. Desalination and Water Treatment 2020, 200, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, R.; Taufik, A. Degradation of methylene blue and congo-red dyes using fenton, photo-fenton, sono-fenton, and sonophoto-fenton methods in the presence of iron (ii, iii) oxide/zinc oxide/graphene (fe3o4/zno/graphene) composites. Separation and Purification Technology 2019, 210, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbosiuba, T.C.; Abdulkareem, A.S.; Kovo, A.S.; Afolabi, E.A.; Tijani, J.O.; Auta, M.; Roos, W.D. Ultrasonic enhanced adsorption of methylene blue onto the optimized surface area of activated carbon: Adsorption isotherm, kinetics and thermodynamics. Chemical engineering research and design 2020, 153, 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.; Lin, P.-Y. Fept nanoparticles as heterogeneous fenton-like catalysts for hydrogen peroxide decomposition and the decolorization of methylene blue. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 2012, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Li, J.; Ye, L.; Li, X. Heterogeneous nanostructure anatase/rutile titania supported platinum nanoparticles for efficient photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dyes. Sustainable Chemistry for the Environment 2024, 5, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.J.; Wu, L.-Y.; Ko, T.-S.; Wu, C.-W.; Liu, C.-C.; Fan, J.-J.; Lee, P.-Y.; Lin, Y.-S. Effects of thermal treatment on sea-urchin-like platinum nanoparticlese. Applied Surface Science 2024, 657, 159799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, J.; Guo, P.; Zhai, J.; Liu, X.; Yu, D.; You, X.; Li, J. Pdptcu nanoflower mediated photothermal enhanced fenton catalysis for recyclable degradation of methylene blue. Inorganic Chemistry Communications 2024, 160, 111841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; Ahmed, J.; Algethami, J.S.; Alkorbi, A.S.; Harraz, F.A. Facile synthesis of platinum/polypyrrole-carbon black/sns2 nanocomposite for efficient photocatalytic removal of gemifloxacin under visible light. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society 2024, 28, 101806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameel, M.S.; Aziz, A.A.; Dheyab, M.A.; Mehrdel, B. Rapid methanol-assisted amalgamation of high purity platinum nanoparticles utilizing sonochemical strategy and investigation on its catalytic activity. Surfaces and Interfaces 2020, 21, 100785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Tiri, R.N.E.; Bekmezci, M.; Altuner, E.E.; Aygun, A.; Mei, C.; Yuan, Y.; Xia, C.; Dragoi, E.-N.; Sen, F. Synthesis of novel activated carbon-supported trimetallic pt–ru–ni nanoparticles using wood chips as efficient catalysts for the hydrogen generation from nabh4 and enhanced photodegradation on methylene blue. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 21055–21065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peramune, D.; Manatunga, D.C.; Dassanayake, R.S.; Premalal, V.; Liyanage, R.N.; Gunathilake, C.; Abidi, N. Recent advances in biopolymer-based advanced oxidation processes for dye removal applications: A review. ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH 2022, 215, 114242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Hersch, S.J.; He, X.; Zhou, R.; Dong, T.G.; Lu, Q. A lightweight, mechanically strong, and shapeable copper-benzenedicarboxylate/cellulose aerogel for dye degradation and antibacterial applications. Separation and Purification Technology 2022, 283, 120229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Mu, M.; Wang, L.; Fan, Y.; Liu, X. Eco-friendly ferrocene-functionalized chitosan aerogel for efficient dye degradation and phosphate adsorption from wastewater. Chemical engineering journal 2022, 439, 135605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakis, S.; Lin, K.-Y.A.; Ghanbari, F. A review of the recent advances on the treatment of industrial wastewaters by sulfate radical-based advanced oxidation processes (sr-aops). Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 406, 127083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, C.; Li, Y.; Gao, J.; Yu, C.-P. Enhancement of emerging contaminants removal using fenton reaction driven by h2o2-producing microbial fuel cells. Chemical Engineering Journal 2017, 307, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari, A.; Mahmoudian, M.H.; Niari, M.H.; Eş, I.; Dehganifard, E.; Kiani, A.; Javid, A.; Azari, H.; Fakhri, Y.; Khaneghah, A.M. Rapid and efficient ultrasonic assisted adsorption of diethyl phthalate onto feiife2iiio4@ go: Ann-ga and rsm-df modeling, isotherm, kinetic and mechanism study. Microchemical Journal 2019, 150, 104144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wei, D.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Yan, L.; Wei, Q.; Du, B.; Xu, W. Edta functionalized magnetic biochar for pb (ii) removal: Adsorption performance, mechanism and svm model prediction. Separation and Purification Technology 2019, 227, 115696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, A.; Hait, S. Metal bioleaching from printed circuit boards by bio-fenton process: Optimization and prediction by response surface methodology and artificial intelligence models. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 326, 116797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Tian, Y.-j.; Deng, N.-y. Robust unsupervised and semi-supervised bounded ν- support vector machines. In Advances in Neural Networks–ISNN 2009: 6th International Symposium on Neural Networks, ISNN 2009 Wuhan, China, -29, 2009 Proceedings, Part II 6; Springer, 26 May 2009; pp. 312–321. [Google Scholar]

- Knudson, D. Linear and angular kinematics. In Fundamentals of biomechanics; Springer, 2021; pp. 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, S.; Yadav, M.K.; Gupta, A.K.; Uddameri, V.; Toppo, A.N.; Maheedhar, B.; Ghosal, P.S. Modeling defluoridation of real-life groundwater by a green adsorbent aluminum/olivine composite: Isotherm, kinetics, thermodynamics and novel framework based on artificial neural network and support vector machine. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 302, 113965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathankumar, A.K.; Saikia, K.; Ribeiro, M.H.; Cheng, C.K.; Purushothaman, M.; Vaidyanathan, V.k. Application of statistical modeling for the production of highly pure rhamnolipids using magnetic biocatalysts: Evaluating its efficiency as a bioremediation agent. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 412, 125323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.; Mahanty, B.; Hait, S. Coagulative removal of polystyrene microplastics from aqueous matrices using fecl3-chitosan system: Experimental and artificial neural network modeling. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 468, 133818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, H.E.; Seland, F.; Sunde, S.; Burheim, O.S.; Pollet, B.G. Two routes for sonochemical synthesis of platinum nanoparticles with narrow size distribution. Materials Advances 2021, 2, 1962–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchon, A.; Zhang, P.; Li, J.; Joseph, E.A.; Chen, W.; Zhou, H.-C. Effect of isomorphic metal substitution on the fenton and photo-fenton degradation of methylene blue using fe-based metal–organic frameworks. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2020, 12, 9292–9299. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, H.; Zhao, H.; Cao, T.; Qian, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, G. Efficient degradation of high concentration azo-dye wastewater by heterogeneous fenton process with iron-based metal-organic framework. Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical 2015, 400, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | Catalyst | Contaminant | M=Catalyst/MB ratio | Removal efficiency(%) | Time (min) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCN-250 (500 PPM) | MB (15 PPM) | 33.3 | 88 | 720 | Kirchon et al. [42] | |

| PCN-250 (500 PPM) | MB (15 PPM) | 33.3 | 100 | 720 | Kirchon et al. [42] | |

| MIL-100 | (1000 PPM) | MB (500 PPM) | 2.0 | 42 | 230 | Lv et al. [43] |

| Fe | MIL-100 (1000 PPM) | MB (500 PPM) | 2.0 | 94 | 230 | Lv et al. [43] |

| (1000 PPM) | MB (500 PPM) | 2.0 | 59 | 230 | Lv et al. [43] | |

| MIL-100 | (1000 PPM) | MB (500 PPM) | 2.0 | 95 | 230 | Lv et al. [43] |

| Fe | MIL-100 (1000 PPM) | MB (500 PPM) | 2.0 | 85 | 230 | Lv et al. [43] |

| (1000 PPM) | MB (500 PPM) | 2.0 | 61 | 230 | Lv et al. [43] | |

| Fe-Pt | Fe-Pt (5 ppm) | MB (5 ppm) | 1.0 | 90 | 90 | Hsieh et al. [21] |

| (500 ppm) | MB (5 ppm) | 100 | 55 | 90 | Hsieh et al. [21] | |

| PS-Pt | Pt (5 PPM) | MB (3.2 ppm) | 1.5 | 86 | 110 | This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).