1. Introduction

India’s agricultural landscape has long been characterised by traditional practices that contribute to environmental sustainability, climate resilience, and food security (Patel et al., 2020). However, a notable shift is occurring as younger generations increasingly migrate to non-agricultural sectors, resulting in workforce shortages and a growing reliance on technological interventions (Amalan & Aram, 2023). Artificial Intelligence (AI) offers promising solutions by automating processes, enhancing decision-making, and increasing operational efficiency (Büyüközkan & Uztürk, 2024).

A critical gap remains in understanding its integration with Non-Chemical Agricultural Methods (NCAM) (Klerkx et al., 2019). NCAM represents sustainable farming practices that prioritise biodiversity, preserve soil health, and support chemical-free food production. Despite its ecological benefits, NCAM adoption remains limited due to challenges such as labour intensity, lack of technological support, and limited financial resources. Integrating AI into NCAM systems could address these challenges by improving productivity, reducing environmental impact, and supporting climate-smart agricultural (CSA) practices (Finger, 2023).

While the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) is widely used to evaluate technology adoption, it often neglects the influence of traditional ecological knowledge on perceived usefulness (Pierpaoli et al., 2013). This study bridges that gap by adopting a justice-centred lens to examine AI adoption in NCAM. By employing discourse and thematic analysis, it captures smallholders’ lived experiences, addressing how narratives and local contexts shape adoption (Bronson & Knezevic, 2016).

NCAM promote climate resilience, biodiversity, and sustainability, rooted in traditional practices yet needing modern support. Sir Albert Howard (1945) praised India’s chemical-free farming resilience. AI can address challenges like labour shortages and climate stress by enabling pest detection, soil monitoring, and yield prediction (Liu et al., 2021; Saiz-Rubio & Rovira-Más, 2020). Integrating AI into extension services can enhance NCAM adoption through predictive analytics and decision-support tools (Zul Azlan et al., 2024).

Despite its promise, Artificial Intelligence adoption in NCAM faces barriers such as high costs, low digital literacy, and inadequate rural infrastructure (Laskar, 2023; Liu et al., 2021). Addressing these infrastructural gaps is crucial for ensuring equitable access to AI technologies. Resistance from traditional farming communities also poses challenges. Inclusive, transparent deployment strategies are essential to foster trust and ensure equitable access (Gardezi et al., 2023).

AI adoption in NCAM, by addressing farmers’ strategic communication needs, could enhance their cognitive, social, and emotional capacities (Akash & Aram, 2022; Zerfass & Huck, 2007). Educational programmes, peer learning, and success stories foster trust (Spanaki et al., 2021). Human-centred, explainable AI ensures farmer control and supports sustainable practices through transparent, autonomous technologies (Ahmed et al., 2022; Holzinger et al., 2024).

This study pursues three key objectives:

To identify the causal configurations leading to AI adoption among NCAM farmers using fsQCA.

To analyse how discourse constructs a justice-centred relationship between TAM variables and actual adoption.

To develop a refined TAM framework that integrates fsQCA and discourse insights to offer a holistic understanding of AI adoption from a justice-centred perspective.

2. Review of Literature

AI technologies, including artificial neural networks, fuzzy systems, and agricultural robots, are transforming farming by enhancing crop monitoring, pest management, disease detection, and yield prediction (Elbasi et al., 2023). AI-driven smart agriculture systems using deep learning and IoT sensors can reduce pesticide use and improve environmental sustainability (Chen et al., 2020). Precision agriculture, supported by technologies like drones, satellites, and sensors, optimises inputs and reduces labour costs (Sharma et al., 2021)

The increasing cost of labour and the demand for premium produce are driving the adoption of AI technologies in on-farm sorting and transportation, reducing post-harvest losses through faster and more accurate processing (Zhou et al., 2023). Additionally, AI-powered autonomous weeding systems employing 3D visual tracking and predictive control are improving sustainability by reducing herbicide use and optimising operations across varied terrains (Wu et al., 2020).

However, AI adoption in rural India faces challenges such as inadequate infrastructure, digital illiteracy, and financial constraints (Gandhi & Parejiya, 2023; Laskar, 2023). Linguistic diversity in India presents a major communication challenge for AI adoption, with over 600 languages complicating outreach efforts. Trust issues also persist, particularly among marginalised farming communities, due to limited exposure to AI applications (Tzachor, 2021).

NCAM, such as organic farming, conservation agriculture, and Integrated Pest Management (IPM), promote sustainable practices by reducing pesticide use and enhancing soil health (Kumar et al., 2023; Paudel et al., 2020). It also provides added benefits by eliminating synthetic pesticides, preserving biodiversity, enhancing soil health, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. (Benbrook et al., 2021; Gomiero et al., 2011). AI can complement NCAM by providing real-time monitoring, predictive analytics, and decision-support systems to optimise irrigation, detect diseases, and evaluate soil health (Sachithra & Subhashini, 2023). Despite challenges, integrating AI with NCAM holds promise for sustainable farming and improving food security in India(Andujar, 2023;Islam et al., 2024)Islam et al., 2024). Aversion to unsafe food is increasing consumer demand for healthier, organic options, leading to the expansion of NCAM adoption and emphasising sustainable agricultural practices (Thanki et al., 2022).

3. Theoretical Framework

This study presents an integrated framework combining the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), justice-centred theory, and ecological values to examine AI and NCAM adoption in sustainable agriculture. Using thematic analysis, discourse analysis, and fsQCA, it captures farmers' perspectives and complex factors shaping responsible technology use.

3.1. TAM Application in AI Adoption

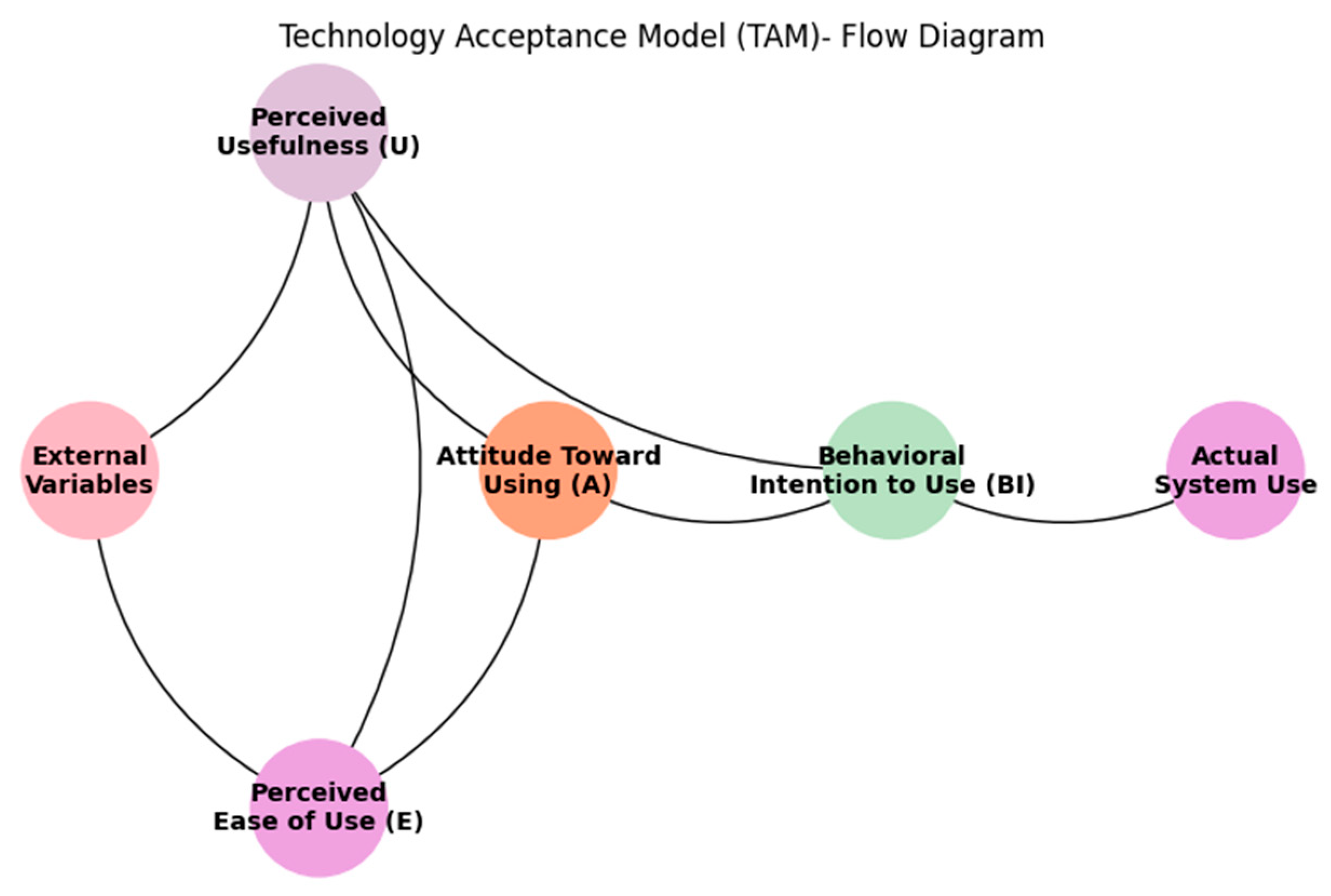

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) is widely used to assess the adoption of technology in various fields, including agriculture. The model, as shown in

Figure 1, demonstrates that Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) affect Behavioural Intention (BI), eventually leading to Actual Use (Davis, 1989). However, TAM applications in sustainable agriculture often neglect how traditional ecological knowledge shapes farmers’ perceptions of usefulness (Pierpaoli et al., 2013).

This study uses the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), developed by Davis (1989), to describe the user adoption of technological innovations. TAM is a foundational model across diverse sectors, including e-learning, e-commerce, and digital services to explore the adoption pattern among the end-user(Venkatesh & Davis, 2000; Marangunić & Granić, 2014). Its primary constructs—perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEU)—provide critical insights into users’ attitudes, behavioural intentions, and actual technology usage (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

Adopting the Technology Acceptance Model in agriculture has become increasingly important. Agriculture towards a sustainable environment are at its beginning, and significant studies are forming (Mohr & Kühl, 2021). The implication of sustainable practices and hesitation among farmers to adopt new methods that rely on chemical-free methods, using TAM could adequately explain the adoption and use of biological inputs (Bagheri et al., 2021). This study assesses the acceptance and adoption of AI and NCAM among farmers using TAM and investigates how AI-driven solutions can complement sustainable agricultural practices.

This study attempts to integrate the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) with ecological values and technology development, examining how AI aligns with the values of NCAM farmers. A justice-centred approach to adoption serves as a mediating framework for promoting AI adoption in sustainable agriculture. To encourage the responsible adoption of AI and NCAM by addressing both technological advancement and environmental sustainability.

3.2. Thematic and Discourse Analysis

Thematic analysis identifies patterns from Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) on AI and NCAM, capturing farmers’ concerns, beliefs, and expectations regarding AI adoption (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) examines how language, shaped by social power dynamics and inequalities, influences understanding and adoption of technology (Kress 1991). By combining thematic and discourse analysis, the study highlights how farmers’ narratives shape perceptions and potential barriers to AI adoption (Phillips et al., 2004).

3.3. fsQCA for Evaluating AI and NCAM Adoption in the TAM Pathway

Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) is an advanced analytical method that identifies causal configurations leading to specific outcomes. By applying fsQCA to AI adoption in NCAM, this study explores the complex interplay of factors influencing farmers’ decisions. fsQCA captures multifaceted interactions, complementing the TAM (Ragin, 2008). While TAM has been widely used to assess technology adoption in agriculture, its application to AI and NCAM remains underexplored.. Integrating fsQCA with TAM and discourse analysis offers a holistic perspective on how AI adoption unfolds in sustainable agriculture, providing valuable insights for policymakers, agricultural agencies, and AI developers. A similar approach has been applied in health technology adoption (Mustafa et al., 2022), but this study is one of the first to apply fsQCA to AI adoption pathways in agriculture.

3.4. Justice-Centred Perspective in AI and NCAM Adoption

A justice-centred view of AI adoption prioritises fair access to technology, shared decision-making, and inclusive policies, ensuring that marginalised farmers benefit from AI in NCAM. Barriers such as cost, infrastructure, and lack of support contribute to the digital divide, while social issues like job security, trust, and the absence of diverse stakeholder voices are also significant (Cubric, 2020). Political theorist Nancy Fraser’s justice framework highlights three dimensions: economic justice (fair resource distribution), cultural justice (recognition of all social groups), and political justice (ensuring equal participation) (Fraser, 1995). In NCAM, a justice-centred approach calls for localised AI models that incorporate ecological and cultural knowledge, promoting inclusion and addressing unequal resource distribution. It also questions who benefits from AI adoption, urging continuous reflection on political representation and the voices included in AI development to ensure equitable access and outcomes.

3.5. Novelty of the Study

This study introduces an innovative framework that integrates the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) with a justice-centred approach and ecological values to explore AI and NCAM adoption in sustainable agriculture. The study stands out by combining qualitative methods—thematic and critical discourse analysis—with quantitative modelling through fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA). This mixed-methods approach captures both farmers’ subjective experiences and the complex causal factors influencing adoption. By incorporating economic, cultural, and political justice dimensions into TAM, the framework provides a more inclusive and context-sensitive model of technology acceptance, reflecting the diverse realities of farming communities.

4. Methodology

A structured questionnaire combining closed-ended and open-ended questions was employed to gather data on farmers’ attitudes toward Non-Chemical Agricultural Methods (NCAM), their awareness of AI, and communication preferences. Focus group discussions (FGDs) were also conducted to gain in-depth qualitative insights into challenges, perceptions, and solutions for AI adoption among NCAM farmers (Nyumba et al., 2018). The questionnaire was divided into four sections: Demographic Profile, which gathered basic participant information to contextualise responses; NCAM Practices, which assessed engagement with NCAM and perceptions of its effectiveness; Technology Adoption and AI, which explored awareness and willingness to adopt AI; and Information Needs and Communication Strategy, which investigated communication preferences and effective channels for promoting AI adoption in agriculture.

4.1. Study Area

The study was conducted at three levels: Village Level (Thuraiyur, Nemili Block, Ranipet District), where most participants were women farmers; Block Level (Nemili Block), which included farmers from various villages interested in NCAM; and District Level (18 districts in Tamil Nadu), with farmers actively engaged in agricultural technology programmes.

Figure 2 illustrates a focus group discussion with farmers from Nemili Block and Thuraiyur Village.

4.2. Participant Selection

A purposive sampling technique was used to select 57 NCAM farmers and those willing to adopt NCAM for the focus group, ensuring diversity across Tamil Nadu. From this group, 18 to 21 farmers were selected for each FGD to explore topics in more detail.

Focus Group 1 (FGD1) – Marginal Farmers (n=18): Farmers practising or interested in adopting NCAM in Thuraiyur village, Nemili Block.

Focus Group 2 (FGD2) – Active NCAM Engagement (n=21): Farmers practising NCAM and sharing insights on agricultural technologies, from various villages in Nemili Block.

Focus Group 3 (FGD3) – Interest in Agricultural Technologies (n=18): Farmers from multiple villages and blocks across 18 districts in Tamil Nadu, offering perspectives on AI’s benefits and challenges in NCAM.

This sampling technique was used to select 57 NCAM farmers, ensuring diversity across Tamil Nadu. Each focus group comprised 18-21 farmers, facilitating in-depth exploration of topics.

5. Data Analysis

Descriptive Statistics: Descriptive statistics summarise data using measures of central tendency (mean, median) and variability (standard deviation, range), providing an overview of the dataset. These summaries help identify patterns and distributions, forming the foundation for deeper analysis and ensuring transparency in research, aiding decision-making in data analysis (Ryan & Bernard, 2003).

Thematic Analysis: Qualitative data from open-ended questions were coded into themes to capture common patterns and viewpoints, grounded in the actual language of participants (Lochmiller, 2021). Thematic analysis identifies recurring patterns, helping interpret farmers’ core ideas and facilitating decision-making in research design (Wood et al., 2014).

Discourse Analysis: A justice-centred approach prioritises equity, examining socio-economic conditions and resource access disparities, particularly for marginalised smallholders (Chindasombatcharoen et al., 2024; McGuire et al., 2024). It evaluates external variables such as age, gender, location, and farming experience, considering their impact on AI and NCAM adoption. The study assesses perceived usefulness (PU), ease of use (PEU), farmers’ attitudes (A), and behavioural intentions (BI) toward AI/NCAM adoption, con sidering historical and cultural contexts. Trust in institutions, participatory decision-making, and digital literacy are central to understanding adoption gaps and fostering inclusivity.

The study integrates fsQCA with discourse analysis to uncover essential causal combinations that facilitate AI adoption in the context of NCAM. Unlike regression analysis, fsQCA accommodates non-linear relationships, making it well-suited for exploring complex, real-world scenarios (Kraus et al., 2018). From the FGD’s themes are coded for fsQCA analysis are presented in

Table 1, illustrating the key conditions for successful AI adoption in NCAM.

The fsQCA process follows a structured methodology with several key steps. Initially, necessity analysis is performed to identify conditions that consistently align with AI adoption. The next step, sufficiency analysis, explores different combinations of factors that lead to AI adoption. The study integrates fsQCA with discourse analysis to uncover essential causal combinations that facilitate AI adoption in the context of NCAM. A truth table is then constructed to identify high-consistency pathways. The final step involves deriving QCA solutions, including complex, parsimonious, and intermediate solutions, which provide varying levels of causal explanation. To ensure the robustness of the findings and to support the discourse analysis, the fsQCA calculations were performed using Python for further validation and reliability checks.

6. Data Interpretation

Understanding the adoption of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Non-Chemical Agricultural Methods (NCAM) among farmers requires a nuanced interpretation of both numerical trends and experiential accounts. To achieve this, a mixed-methods approach was employed, combining descriptive statistics, thematic analysis, discourse analysis, and narrative inquiry. These methods help illuminate not only the patterns of adoption but also the underlying perceptions, socio-cultural factors, and power dynamics that shape farmers’ choices. To further identify causal conditions influencing adoption, discourse analysis was integrated with fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA), guided by the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). Together, these analytical tools provide a comprehensive understanding of how ecological values, technological perceptions, and communication practices interact in shaping sustainable agricultural transitions.

6.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics from three focus group discussions (n=57) reveal a predominantly middle-aged male sample with an average farming experience of 4.35 years. Respondents are distributed across multiple districts, showing some variability. Approximately half of the respondents have adopted NCAM, although adoption remains limited (

Table 2). Workforce shortages are minimal, but participants strongly agree that NCAM is labour-intensive and feel they lack sufficient technology to balance workforce demands.

Most participants lack awareness of AI applications in farming and show limited willingness to adopt AI-driven technologies, indicating potential barriers. Communication channels are rated highly effective, but mobile app usage for farming guidance shows mixed responses, reflecting varied adoption levels.

6.2. Thematic Analysis

Thematic insights from the focus group discussions (FGDs) revealed three core areas shaping farmers’ perspectives: (1) the practice and effectiveness of Non-Chemical Agricultural Methods (NCAM), (2) the perceived utility and scope of AI technologies in sustainable farming, and (3) the information needs and communication strategies required for effective adoption. These themes provide a structured lens to interpret how NCAM is practiced, how AI is perceived, and how communication efforts can be better aligned to support knowledge and technology transfer.

6.2.1. Theme 1: Non-Chemical Agriculture Methods – Crops Cultivated in NCAM

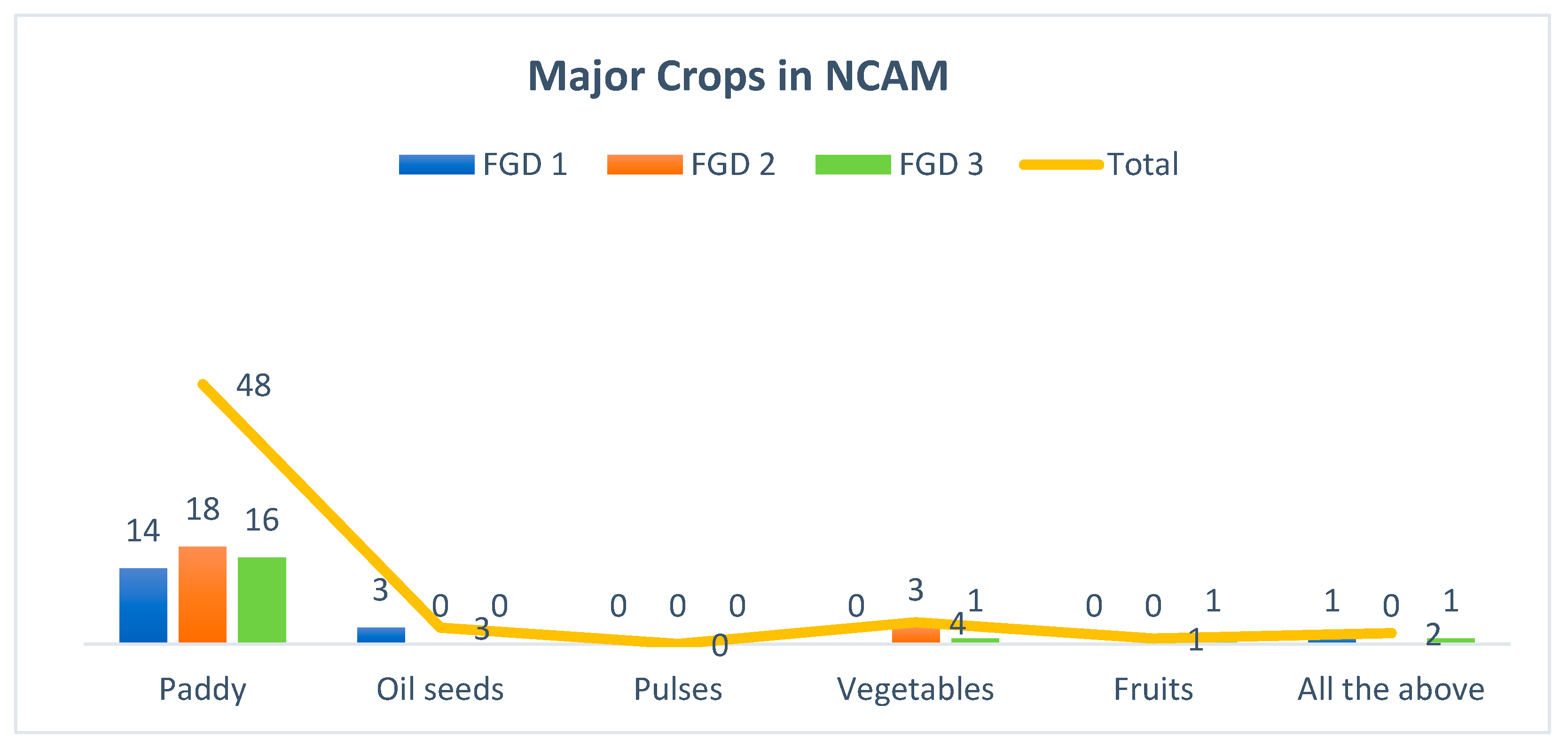

In

Figure 3 shows that paddy cultivation dominates among NCAM farmers, with 48 respondents across three focus groups reporting its cultivation. Oilseeds and vegetables were cultivated by fewer farmers, while only one participant in FGD 3 grew fruits. Two farmers (one each from FGD 1 and FGD 3) grew mixed crops. This pattern indicates limited crop diversity in NCAM systems, with paddy being the primary focus.

- 2.

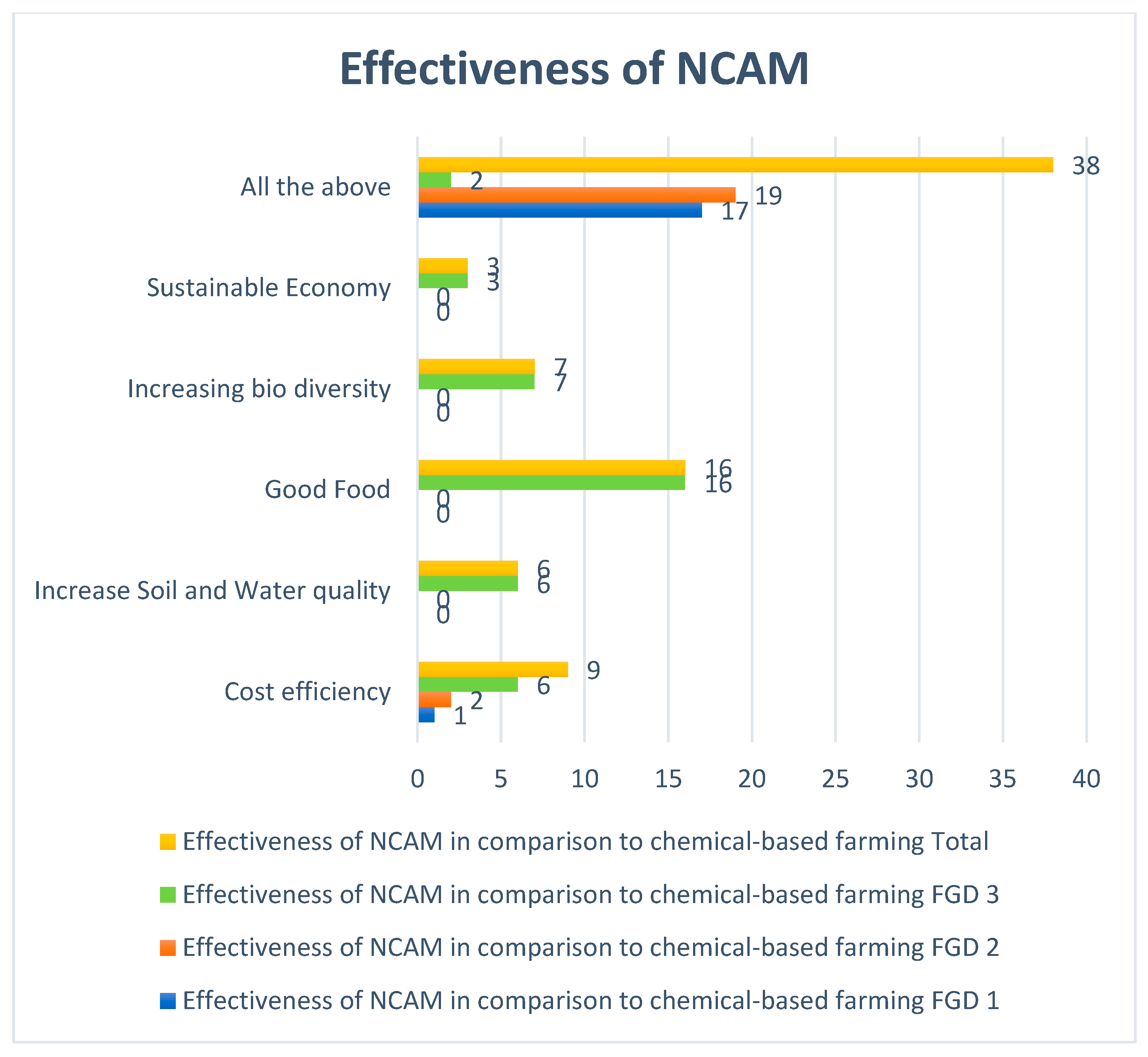

Effectiveness of NCAM Compared to Chemical-based Farming

Figure 4 presents farmers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of NCAM. FGD 3 showed the strongest support for the benefits of NCAM, particularly in producing healthier food (18 responses) and improving sustainability (19 combined responses). FGD 2 emphasised cost efficiency (6 responses) and biodiversity (7 responses), while FGD 1 remained largely disengaged. Environmental benefits like soil quality (14 responses) received moderate support, while economic sustainability concerns were most prominent in FGD 3 (8 responses).

6.2.2. Theme 2: AI Technology Adoption

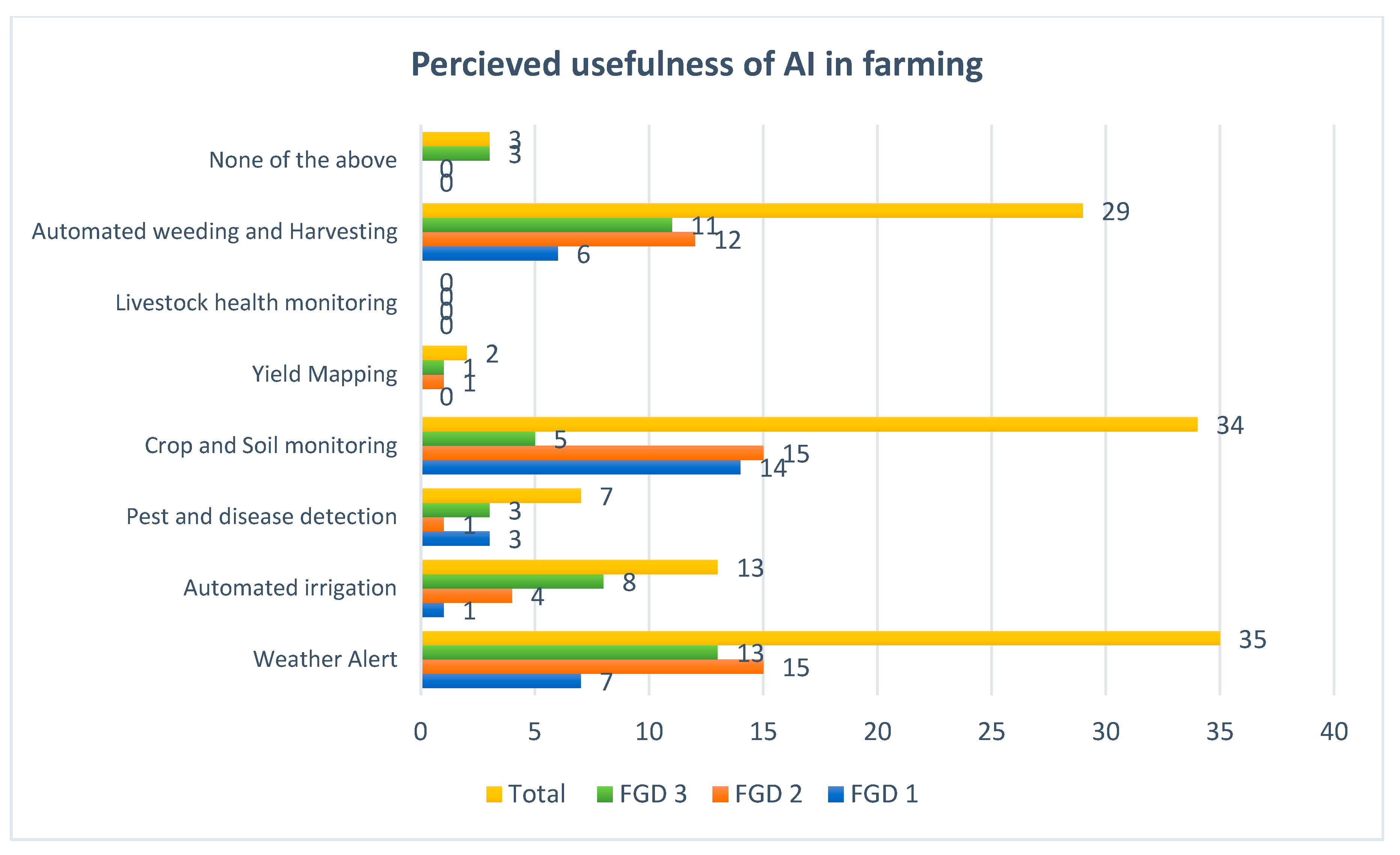

Figure 5 illustrates farmers’ perceptions of useful AI applications. Weather alerts, crop monitoring, and automated weeding received 50-60% approval. Irrigation support attracted 13 responses, while pest detection garnered only 7 responses. Interest in yield mapping was minimal (2 responses), and there was no interest in livestock monitoring, which aligns with the predominant focus on paddy cultivation.

- 2.

Farmer Preferences for AI Applications: Emphasis on Labour-Saving and Climate-Smart Solutions

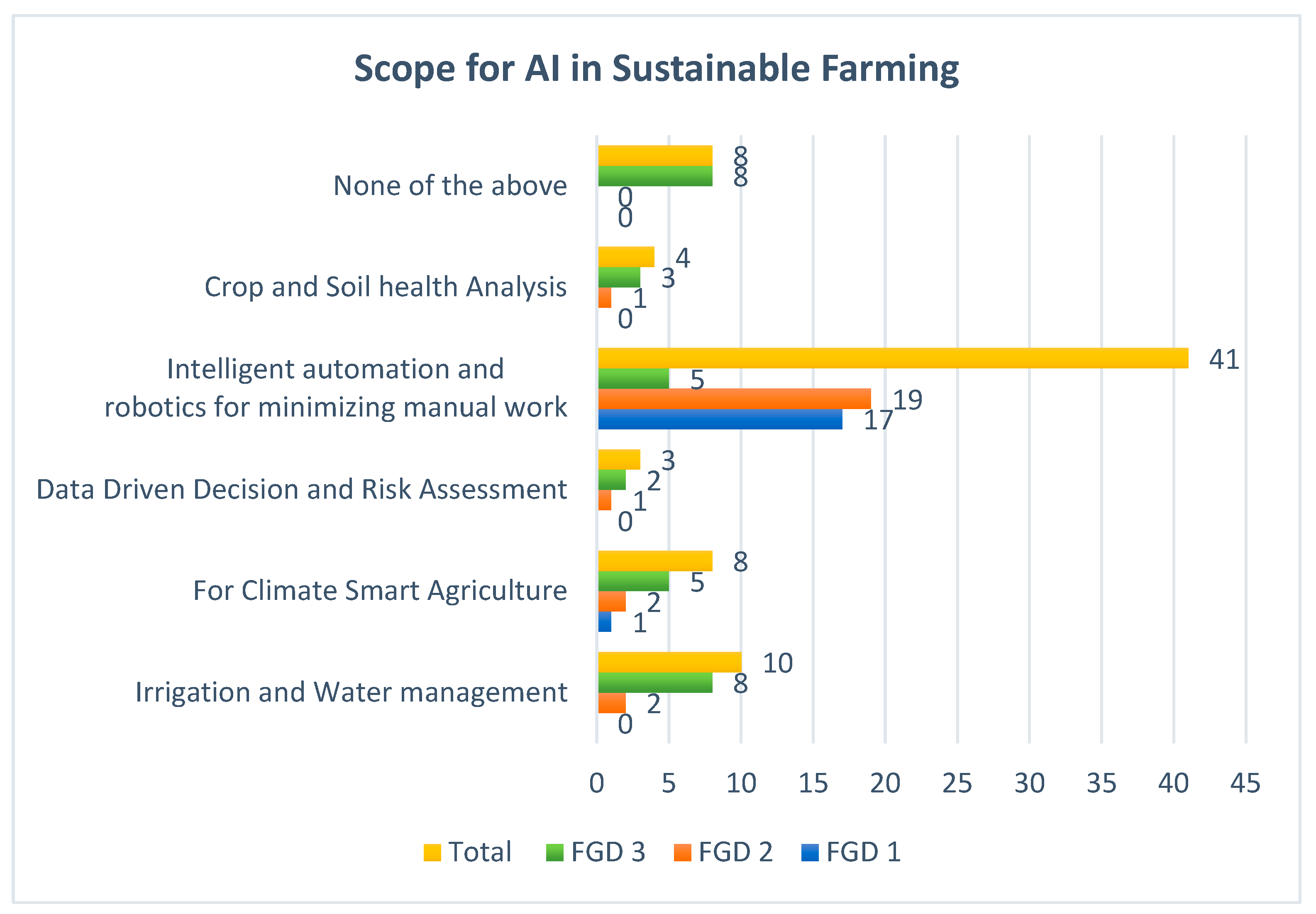

Farmers particularly valued labour-saving applications, with intelligent automation receiving 41 responses (

Figure 6). Water management and climate-smart applications garnered moderate interest, with 10 and 8 responses, respectively.

- 3.

Support or information needed to adopt AI technologies

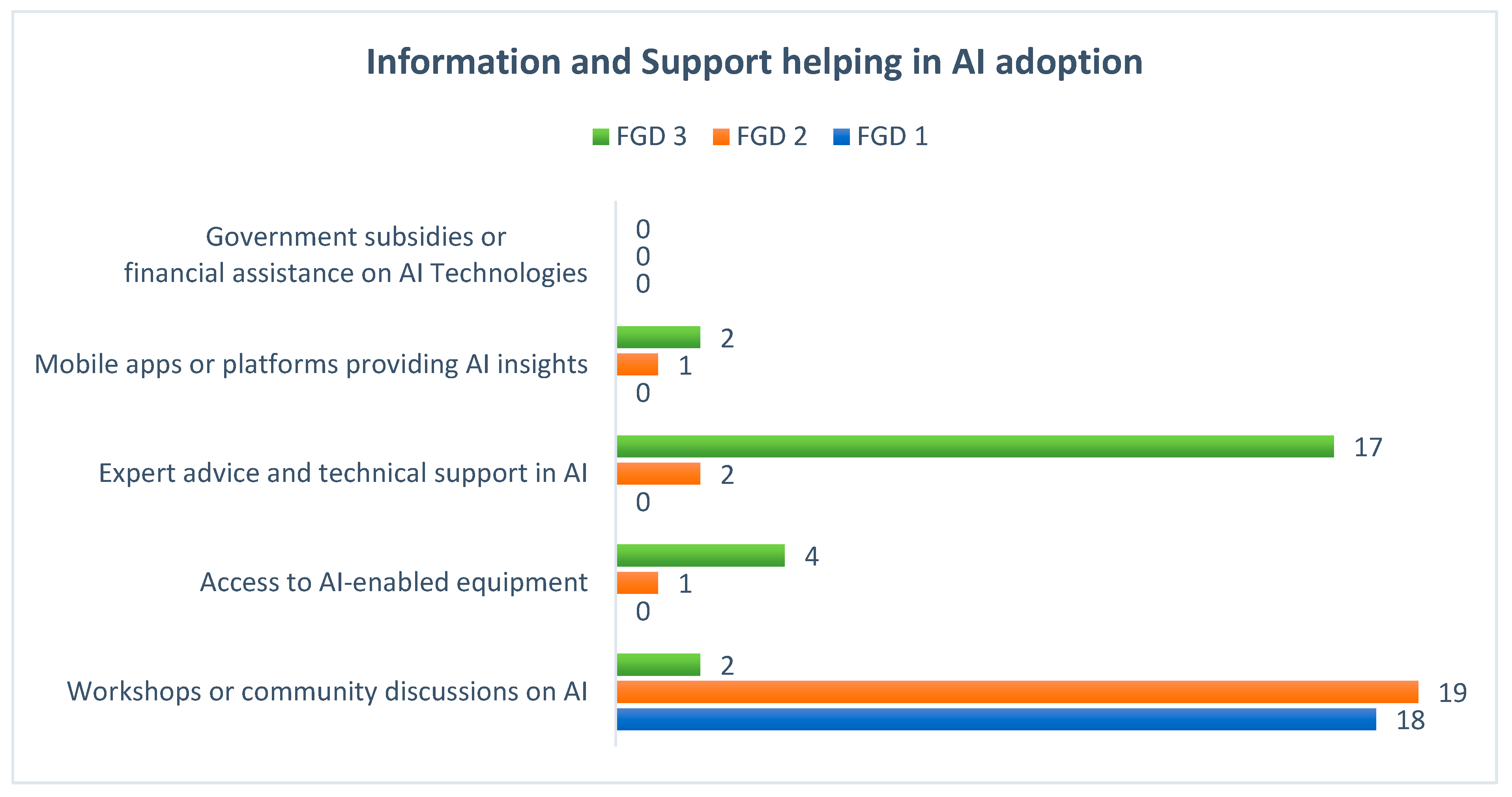

Figure 7 shows that preferred learning methods varied by focus group. FGD 1 and FGD 2 favoured workshops (18 and 19 responses, respectively), while FGD 3 prioritised expert guidance (17 responses). Financial support was rarely mentioned, with a stronger focus on knowledge transfer. Digital platforms and equipment access received limited interest (under 10 responses combined).

6.2.3. Theme 3: Information Need and Communication Strategy

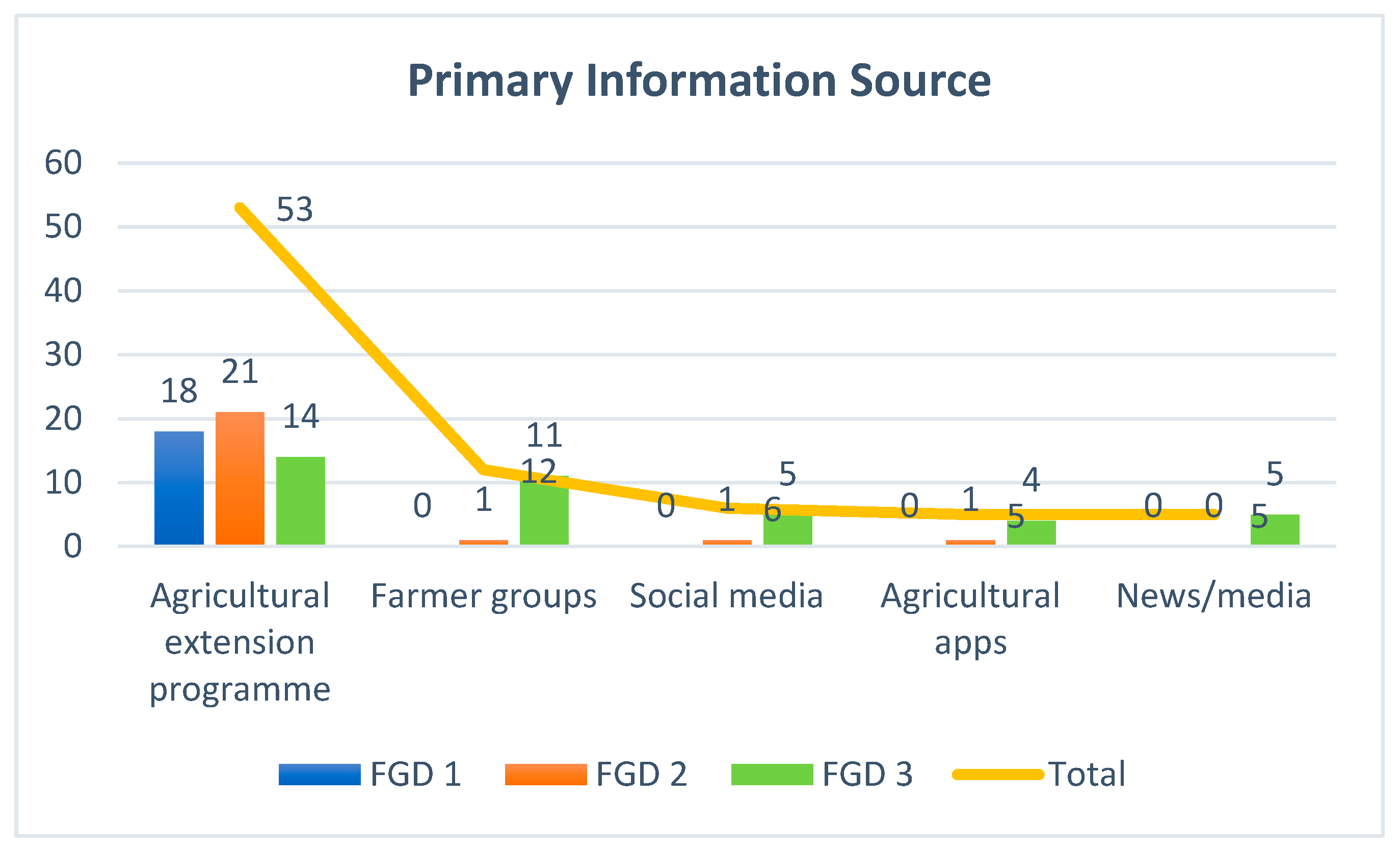

Figure 8 reveals that extension programmes were the dominant information source (53 responses), particularly in FGD 1 and FGD 2. Farmer groups were also important sources of information (12 responses), while digital channels were minimally used (4-5 responses for apps/social media). In identifying effective communication methods, extension programmes again led strongly (52 responses), with other options receiving fewer than 10 responses each, confirming farmers’ preference for traditional knowledge-sharing channels.

6.3. Discourse Analysis and Narratives on AI and NCAM Adoption

6.3.1. Discourse Patterns on AI and NCAM Adoption: Demographic, Perceptual, and Behavioural Insights

The demographic characteristics of farmers influence how they engage in discussions about AI and NCAM. The study finds that middle-aged male farmers dominate these conversations, often shaping discourse based on traditional farming experiences. Resistance to technological change is more pronounced among experienced farmers, whereas younger farmers demonstrate greater openness to AI-driven farming solutions. Additionally, variations in farming practices across districts influence the way AI and NCAM are perceived, with farmers in areas with institutional interventions showing more enthusiasm for technological adoption.

- 2.

Perceived Usefulness: Economic and Practical Considerations

Farmers’ discussions about NCAM highlight concerns regarding labour intensity and economic feasibility. While some farmers acknowledge the long-term benefits of NCAM for sustainability and biodiversity, they struggle to justify its short-term viability. The discourse reveals that NCAM is perceived as an environmentally-friendly alternative but economically impractical without technological intervention. In contrast, discussions about AI reveal a general lack of awareness rather than outright rejection. Farmers recognize the potential of AI tools such as automated irrigation and pest detection but are uncertain about their practical integration into current farming practices.

- 3.

Perceived Ease of Use: Challenges in Adoption

Farmers frequently discuss NCAM as labour-intensive and difficult to implement without mechanization. While AI technologies could address this labour burden, discourse suggests that concerns over accessibility, technological complexity, and training requirements hinder adoption. While some farmers believe AI can simplify tasks such as weeding and pest detection, others worry about their ability to operate such systems effectively.

- 4.

Attitude towards AI and NCAM: Trust and Social Influence

Farmers prefer learning about new technologies through workshops, peer discussions, and government extension programmes. The discourse suggests that trust plays a crucial role in adoption, with farmers relying on institutional sources and experienced peers to validate new farming methods. Unlike financial constraints, which are not a primary concern, unfamiliarity and lack of hands-on experience with AI and NCAM contribute to scepticism.

- 5.

Behavioural Intention and Actual System Use

The discourse analysis reveals that while farmers express an interest in AI, they still rely primarily on traditional agricultural extension programmes rather than digital platforms. AI-powered farming applications remain underused due to a preference for direct interactions over digital tools. Bridging this gap requires integrating AI education into existing extension programmes and fostering farmer-led technology adoption initiatives.

6.3.2. Discourse Analysis with Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA)

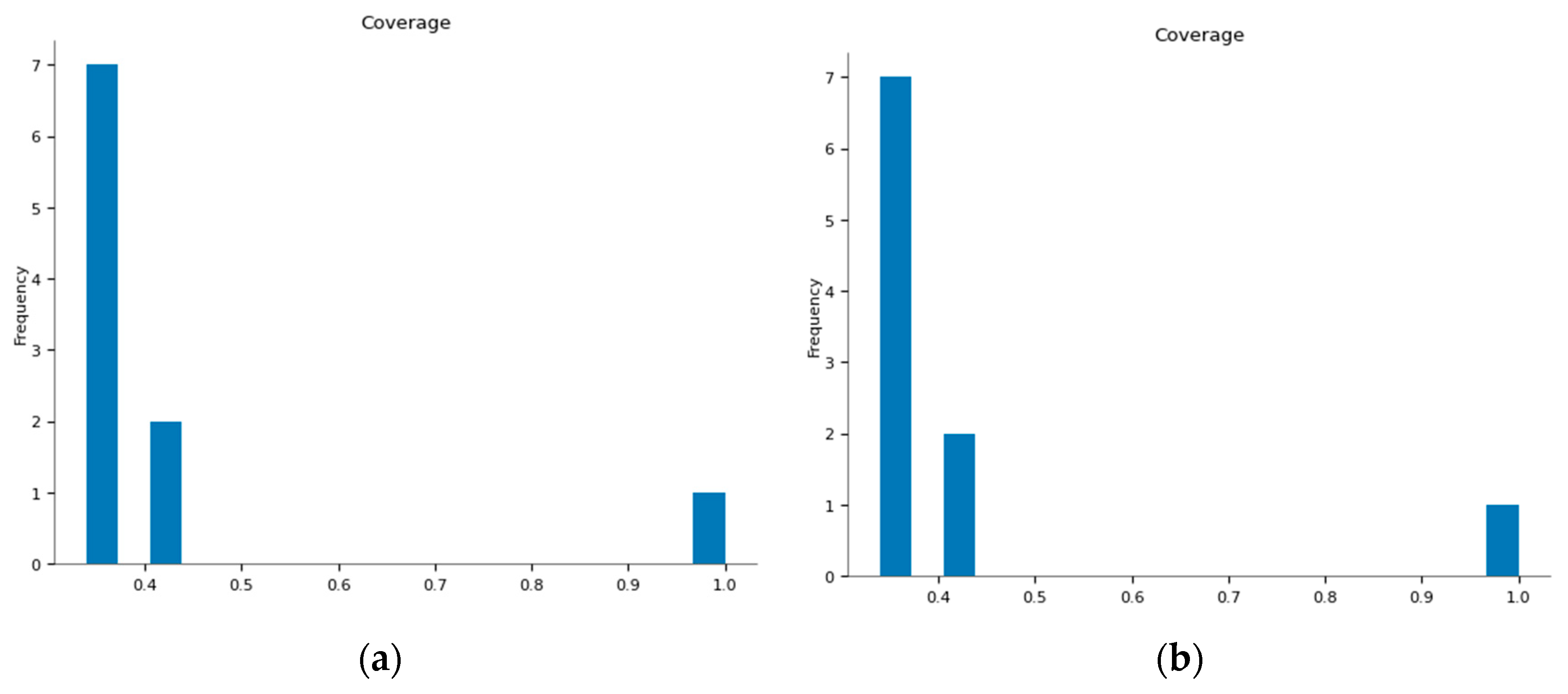

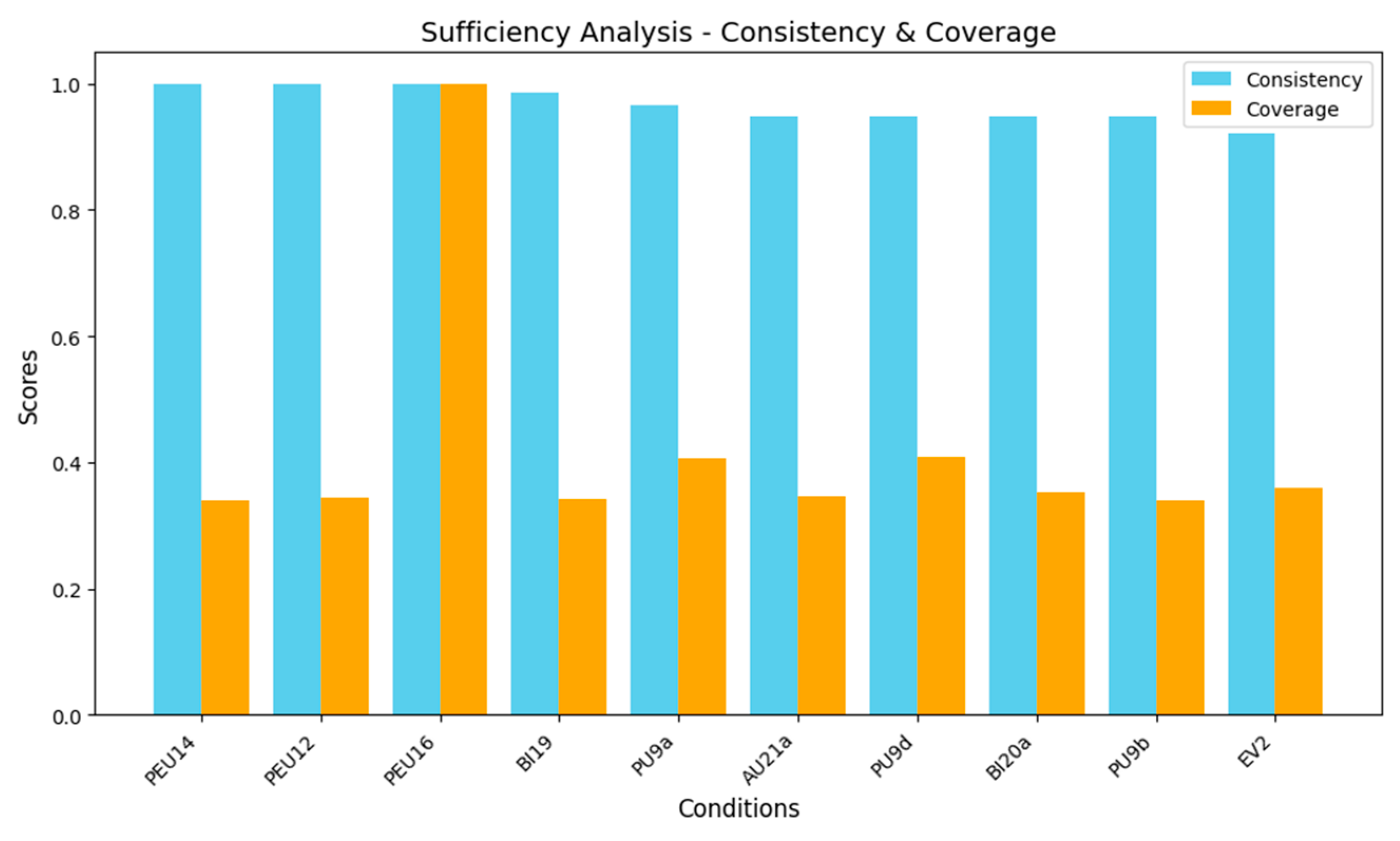

The conditions with the highest consistency scores (≥ 0.90) indicate their necessity for AI adoption (UA). Among them, PEU14 (perception of NCAM as labour-intensive), PEU12 (workforce shortage), and PEU16 (use of agricultural mobile apps) exhibit a perfect consistency score of 1.000, confirming their absolute necessity. Other conditions also demonstrate high consistency, including BI19 (effectiveness of AI communication channels) at 0.987, PU9a (NCAM cost efficiency) at 0.965, and AU21a (agricultural extension programmes as an information source) at 0.948. Additionally, PU9d (biodiversity benefits of NCAM), BI20a (extension programmes for AI communication), and PU9b (NCAM’s impact on food quality) each hold a consistency score of 0.948, further supporting their necessity. Lastly, EV2 (gender) is also identified as a significant factor with a consistency score of 0.922. Given that PEU14, PEU12, and PEU16 have a perfect consistency score of 1.000, they are considered entirely necessary for AI adoption in NCAM.

Necessity analysis identifies conditions consistently present in AI adoption cases.

Table 5.

Conditions present in AI adoption cases.

Table 5.

Conditions present in AI adoption cases.

| Condition |

Consistency |

Coverage |

| PEU14 (Labour-intensive perception of NCAM) |

1.000 |

0.339 |

| PEU12 (Workforce shortage) |

1.000 |

0.344 |

| PEU16 (Use of agricultural mobile apps) |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| BI19 (Effectiveness of AI communication) |

0.987 |

0.342 |

| PU9a (NCAM cost efficiency) |

0.965 |

0.405 |

| AU21a (Agricultural extension programme as information source) |

0.948 |

0.346 |

| PU9d (NCAM biodiversity benefits) |

0.948 |

0.407 |

| BI20a (Extension programmes for AI communication) |

0.948 |

0.352 |

| PU9b (NCAM impact on food quality) |

0.948 |

0.339 |

| EV2 (Gender) |

0.922 |

0.360 |

- 2.

Sufficiency Analysis

The analysis evaluates sufficiency conditions for AI adoption. PEU14, PEU12, and PEU16 show perfect sufficiency (1.0), making them strong drivers. BI19, PU9a, and AU21a have high consistency but lower coverage, indicating support without guaranteeing adoption. EV2 (gender) has lower sufficiency but remains relevant. Overall, labour intensity, workforce shortages, and mobile apps are key drivers, while cost efficiency, AI communication, and extension programmes assist in the adoption but are not essential.

- 3.

Calibration of Raw Data

Calibration transforms raw survey data into fuzzy-set membership scores, enabling a nuanced analysis of AI adoption among farmers using Non-Chemical Agricultural Methods (NCAM). This process moves beyond binary classifications, capturing varying degrees of membership. It follows a three-anchor point method: full membership (1.0) represents a high likelihood of AI adoption, the crossover point (0.5) indicates a neutral position, and full non-membership (0.0) signifies a low likelihood. Membership scores are assigned using a logistic function or direct threshold setting through fsQCA software.

Table 6.

Calibration of key conditions for AI adoption.

Table 6.

Calibration of key conditions for AI adoption.

| Condition |

Raw Data Range |

Full Membership (1.0) |

Crossover (0.5) |

Full non-membership (0.0) |

| PEU14 (Labour-intensive NCAM perception) |

1 - 5 (Likert Scale) |

5 |

3 |

1 |

| PEU12 (Workforce shortage) |

1 – 5 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

| PEU16 (Use of agricultural mobile apps) |

0 - 10 (usage frequency) |

10 |

5 |

0 |

| BI19 (Effectiveness of AI communication) |

1 - 5 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

| PU9a (NCAM cost efficiency) |

1 - 5 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

| AU21a (Agricultural extension programme info source) |

1 - 5 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

| PU9d (NCAM biodiversity benefits) |

1 - 5 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

| BI20a (AI communication via extension programmes) |

1 - 5 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

| PU9b (NCAM impact on food quality) |

1 - 5 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

| EV2 (Gender) (Male=1, Female=0) |

0 - 1 |

1 (Male) |

0.5 |

0 (Female) |

Truth Table Construction shows different configurations leading to AI adoption.

Table 7.

Configurations leading to AI adoption.

Table 7.

Configurations leading to AI adoption.

| PEU14 |

PEU12 |

PEU16 |

BI19 |

PU9a |

AU21a |

Cases |

AI Adoption Rate |

| 1 |

1 |

1 |

0.75 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

| 1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

15 |

1 |

| 1 |

0.5 |

0 |

0.75 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| 1 |

0.67 |

0.5 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

| 1 |

1 |

0 |

0.75 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

| 1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

7 |

0 |

| 1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

| 1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

24 |

0 |

AI adoption takes place when NCAM is labour-intensive, workforce shortages exist, and mobile apps are used at a level of at least 0.75. Additionally, effective AI communication further supports adoption. AI adoption is more likely when workforce shortages are significant, mobile app usage exceeds 0.5, AI communication is effective, and agricultural extension programmes are used.

- 4.

Solution Pathways (fsQCA Results)

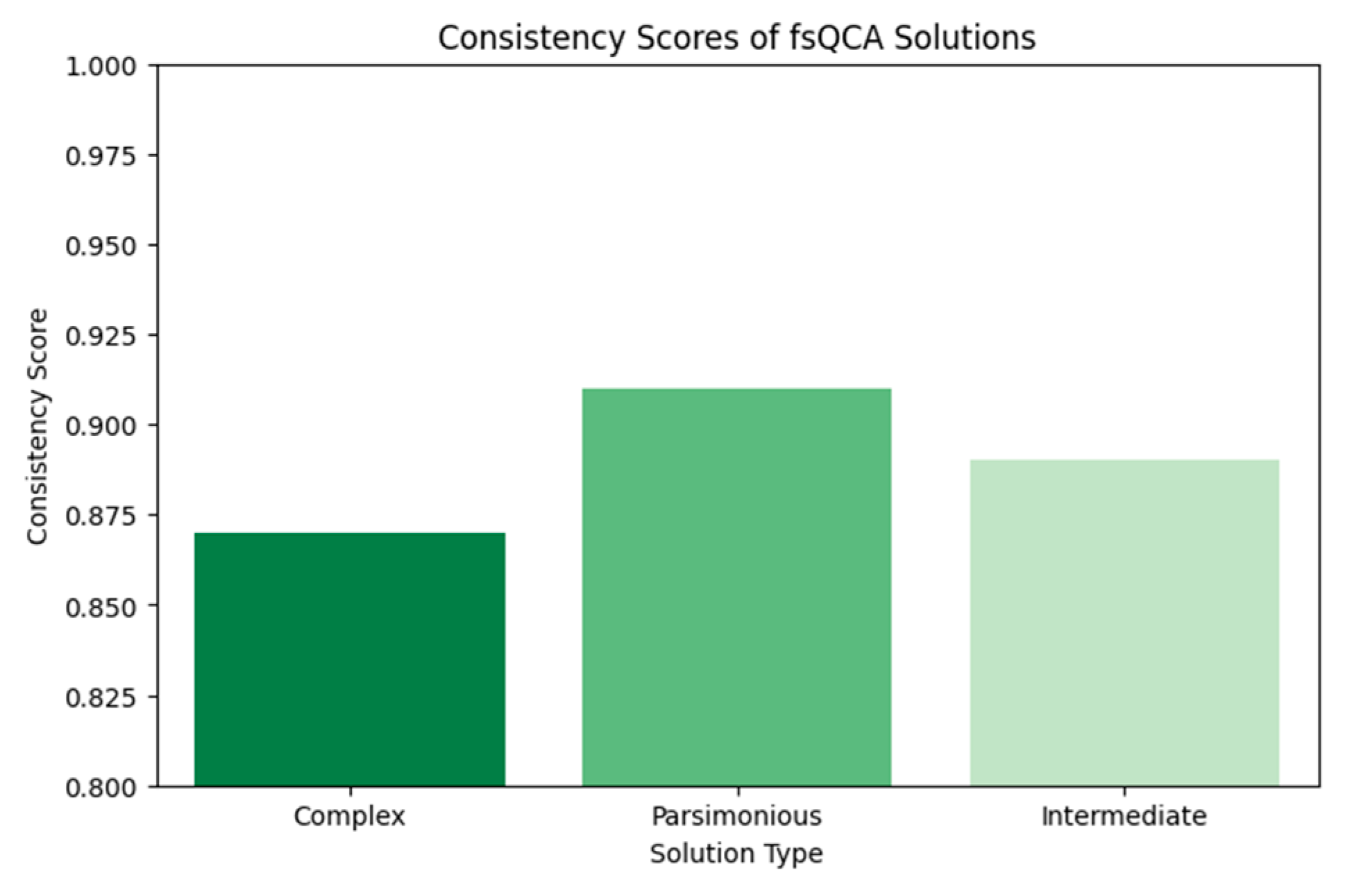

The parsimonious solution, with a consistency of 0.91, presents the strongest and most streamlined pathways for AI adoption. The complex solution, while having lower consistency, provides more detailed configurations without simplifications. The intermediate solution achieves a balance between complexity and simplification, maintaining a consistency of 0.89.

Table 8.

Balance between complexity and simplification.

Table 8.

Balance between complexity and simplification.

| Solution Type |

Consistency |

Coverage |

| Complex |

0.87 |

0.78 |

| Parsimonious |

0.91 |

0.82 |

| Intermediate |

0.89 |

0.80 |

- 5.

Causal Pathways for AI Adoption

AI adoption is high when NCAM is labour-intensive, workforce shortages exist, mobile apps are used, AI communication is effective, NCAM is cost-efficient, and farmers rely on extension programmes. However, adoption remains high even without extension programmes. A key insight is that workforce shortages, mobile app usage, and effective AI communication play a crucial role in driving AI adoption.

7. Key Findings

7.1. Thematic Analysis

7.1.1. Demographics

The demographic profile reveals a skewed pattern in age and gender representation in agriculture. The absence of younger participants (under 30) in the focus group discussions (FGDs) indicates a generational gap that raises concerns about the continuity of sustainable farming practices. Furthermore, women were notably underrepresented—only 15 of 57 participants, primarily in FGD 1—highlighting a broader issue of social recognition. Despite their critical roles in agricultural labour and decision-making, women remain marginalised within predominantly male-dominated structures.

7.1.2. Theme 1: Non-Chemical Agricultural Methods (NCAM)

Farmers generally support non-chemical agricultural methods (NCAM), though significant challenges persist, notably workforce shortages and limited access to appropriate technologies. Priorities varied by group: FGD 2 emphasised cost efficiency, FGD 3 prioritised environmental sustainability, while FGD 1 demonstrated less engagement with the specific benefits of NCAM. Paddy cultivation dominates across all groups, with limited crop diversification due to economic constraints. Interestingly, the labour-intensive nature of NCAM was perceived positively—either because it creates employment opportunities or remains manageable under current conditions.

From an economic justice perspective, although farmers endorse NCAM, they often lack the institutional support and resources required for its full-scale implementation. Small-scale farmers, in particular, bear disproportionate labour burdens without sufficient technological or financial assistance.

7.1.3. Theme 2: AI Technology Adoption

Farmers express interest in artificial intelligence (AI) applications—particularly for weather alerts and automated weeding—yet actual usage and awareness remain limited. There is a marked preference for hands-on training and expert guidance over financial incentives, suggesting that informational barriers outweigh economic ones. Use of mobile-based tools and advanced technologies is especially limited among women and smallholder farmers.

This reflects both digital and representational inequalities. Despite clear interest, access to AI is hindered by insufficient digital infrastructure and farmers' exclusion from the technology design process. The lack of participatory design undermines trust and inhibits adoption.

7.1.4. Theme 3: Information Needs and Communication

Agricultural extension programmes remain the most trusted and frequently used sources of information across all FGDs. Reactions to mobile applications, such as the Uzhavar app, were mixed. Smallholder and women farmers in FGD 1 cited digital barriers, while participants in FGD 2 provided more positive feedback, though concerns about content sufficiency persisted. Across the board, farmers continue to favour face-to-face extension methods over digital platforms for future training and support.

This communication gap underscores challenges of both recognition and representation. Digital tools are not yet fully accessible or tailored to the diverse needs of farming communities, and farmers are rarely consulted during development. This lack of engagement exacerbates informational inequalities and deepens the digital divide.

Viewed through Nancy Fraser’s justice framework, the findings suggest that while farmers are willing to adopt both NCAM and AI technologies, their capacity to do so is constrained by systemic inequalities across access, recognition, and representation.

Economic injustice manifests through inadequate access to labour-saving technologies and financial support.

Social misrecognition affects women and smallholder farmers, whose knowledge and labour remain undervalued.

Representational exclusion persists, as farmers are seldom included in policy development or technology design.

To enable inclusive and sustainable farming, future initiatives must prioritise participatory training, culturally and linguistically appropriate communication, and farmer-led co-design of technologies. Only through these measures can NCAM and AI solutions promote not just productivity, but also equity, justice, and empowerment.

7.2. Integrated Analysis of fsQCA and Discourse Findings

The sufficiency analysis reveals that although several conditions show high consistency scores (0.92–1.00), indicating their statistical importance for AI adoption, the coverage scores (0.4–0.9) are more moderate, suggesting these conditions do not account for adoption across all cases. Discourse analysis helps explain this divergence by uncovering the socio-cultural and structural factors that quantitative metrics alone may overlook.

For example, workforce shortages—one of the most consistent predictors of adoption—manifest differently across groups. While fsQCA confirms its statistical significance, discourse analysis reveals that for smallholders and women, who often depend on informal labour-sharing systems, AI solutions may be viewed as disruptive rather than supportive. This contextual nuance helps explain why high consistency does not always translate to high coverage.

Similarly, institutional trust plays a mediating role in the effectiveness of extension programmes. Although fsQCA identifies these programmes as highly consistent drivers of AI adoption, their variable coverage reflects uneven access and engagement quality. Discourse data show that marginalised farmers often receive generalised, infrequent support, while better-resourced farmers benefit from sustained, context-specific assistance. These disparities diminish trust, which in turn limits participation and explains the shortfall in coverage.

The analysis of adoption pathways further illustrates this tension. Mobile-based solutions demonstrate high consistency (0.92+) but relatively low coverage (0.4–0.6). Discourse findings attribute this to the exclusion of older and less digitally literate farmers. The success of the parsimonious solution, which aligns with a preference for low-tech, community-based learning, confirms that adoption strategies are most effective when they build upon existing knowledge systems rather than impose external, top-down technologies.

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11: fsQCA Outputs.

In summary, while fsQCA validates the statistical strength of certain drivers of AI adoption, discourse analysis reveals that equity and contextual relevance are equally critical. Bridging the gap between technical robustness and inclusive design is essential for ensuring that NCAM and AI technologies benefit all farmers—especially those historically marginalised.

8. Conclusion

This study integrates thematic, discourse, and fsQCA analyses to propose a justice-centred approach to sustainable agricultural transformation. By focusing on farmers’ lived experiences, it highlights the systemic inequalities that shape the adoption of Non-Chemical Agricultural Methods (NCAM) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Tamil Nadu. The chapter lays out strategic recommendations rooted in equity, practical feasibility, and local relevance—emphasising that the success of innovation depends as much on social inclusion and trust as on technological efficacy.

8.1. A Justice-Centred Pathway for Equitable Agricultural Transformation

This study provides a multi-method understanding of sustainable agricultural innovation by combining thematic analysis, discourse analysis, and fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA). The findings reveal both the potential and limitations of Non-Chemical Agricultural Methods (NCAM) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) adoption, with implications for justice in marginalised farming communities.

Farmers in FGDs 2 and 3 expressed strong support for NCAM, highlighting its positive impact on food quality, biodiversity, and soil health. Participants showed awareness of the harmful effects of agrochemicals on microbial diversity and long-term sustainability (Meena et al., 2020). Despite this, fsQCA (consistency: 0.92–1.00; coverage: 0.4–0.9) revealed uneven adoption due to systemic inequalities. Discourse analysis confirmed that smallholders and women—representing 65% of marginalised operators—face exclusion rooted in historical under recognition of their knowledge and roles (Šūmane et al., 2018).

Labour shortages, despite labour-intensive NCAM practices being well regarded, present a significant barrier (fsQCA consistency > 0.95). These shortages could impact food, water, and energy systems, though food remains more resilient due to diverse alternatives (Karan & Asgari, 2021). Justice-oriented strategies should:

Promote gender-sensitive labour solutions;

Integrate mechanisation that respects traditional knowledge;

Support NCAM markets through fair pricing.

- 2.

AI in Agriculture: Bridging the Awareness–Justice Gap

The digital divide persists in AI adoption. Although automation showed high consistency (>0.92), coverage remained low (0.4–0.6). Forty-nine respondents, mainly from FGD 1, were unaware of AI, preferring simpler tools like weather alerts. The fsQCA parsimonious solution (consistency = 1.000) echoed Fraser's (1995) participatory parity, stressing locally adapted, low-tech approaches.

- 3.

Information Access and Trust

While extension services (coverage 0.4–0.9) were moderately used, marginalised farmers often received generic support. Cook (2024) argues that targeting participation in natural resource management improves engagement. The ‘Uzhavar’ app's variable reception further highlights this digital marginalisation.

8.2. Strategic Recommendations: A Justice-Centred Framework

To ensure an equitable transition in agricultural technology, we recommend:

Equitable NCAM Scaling

Inclusive AI Integration

Participatory Governance

Ensure marginalised farmers have a voice in policymaking.

Track adoption metrics by gender, age, and farm size to identify and correct disparities.

This study advances a justice-centred technology adoption framework by quantifying exclusion through the consistency–coverage gaps in fsQCA. It further validates that parsimonious solutions often align with the lived realities of marginalised farmers—illustrating that perceived “effective” innovations may fail when equity in design is neglected.

8.3. AI Integration in NCAM: Merging Technology with Social Justice

The integration of AI into NCAM marks a transformative shift in sustainable agriculture. However, its success is not determined solely by technological performance but by how equitably it is adopted.

FsQCA findings show that cost efficiency (0.92 consistency) and workforce shortages (0.95) significantly influence perceived usefulness, while mobile app literacy (0.88) strongly affects perceived ease of use. Discourse analysis reveals that these factors disproportionately affect women smallholders whose traditional systems are disrupted by inappropriately designed technologies.

- 2.

Adoption Pathway

Farmers initially value AI for its potential to reduce NCAM’s labour demands (e.g., automated irrigation), but actual adoption hinges on social validation—highlighted by 60% of participants who cited peer influence as key. Despite early enthusiasm, a significant proportion remains unaware of or unable to access AI tools, reflecting structural limitations.

Farmer-led networks have proven vital—achieving 70% coverage where extension programmes failed (consistency: 0.75)—underscoring the importance of horizontal, peer-driven knowledge exchange.

- 3.

-

Equity-Centric Priorities:

- 1.

Labour Justice: AI should augment, not replace, labour—especially in women-led collectives.

- 2.

Trust Networks: Peer groups significantly boost adoption rates and trust.

- 3.

Digital Inclusion: Tools must cater to local contexts and literacy levels through regional language and offline designs.

8.4. Reimagining TAM

Traditional Technology Acceptance Models must evolve to include structural and social mediators such as gender roles, trust dynamics, and access inequities, which condition how usefulness and ease of use are perceived.

Practical Measures

Co-design AI tools with farmers to ensure local relevance;

Empower “AI mentors” at village level to lead peer education;

Hybridise extension with both digital and in-person channels to provide sustained support.

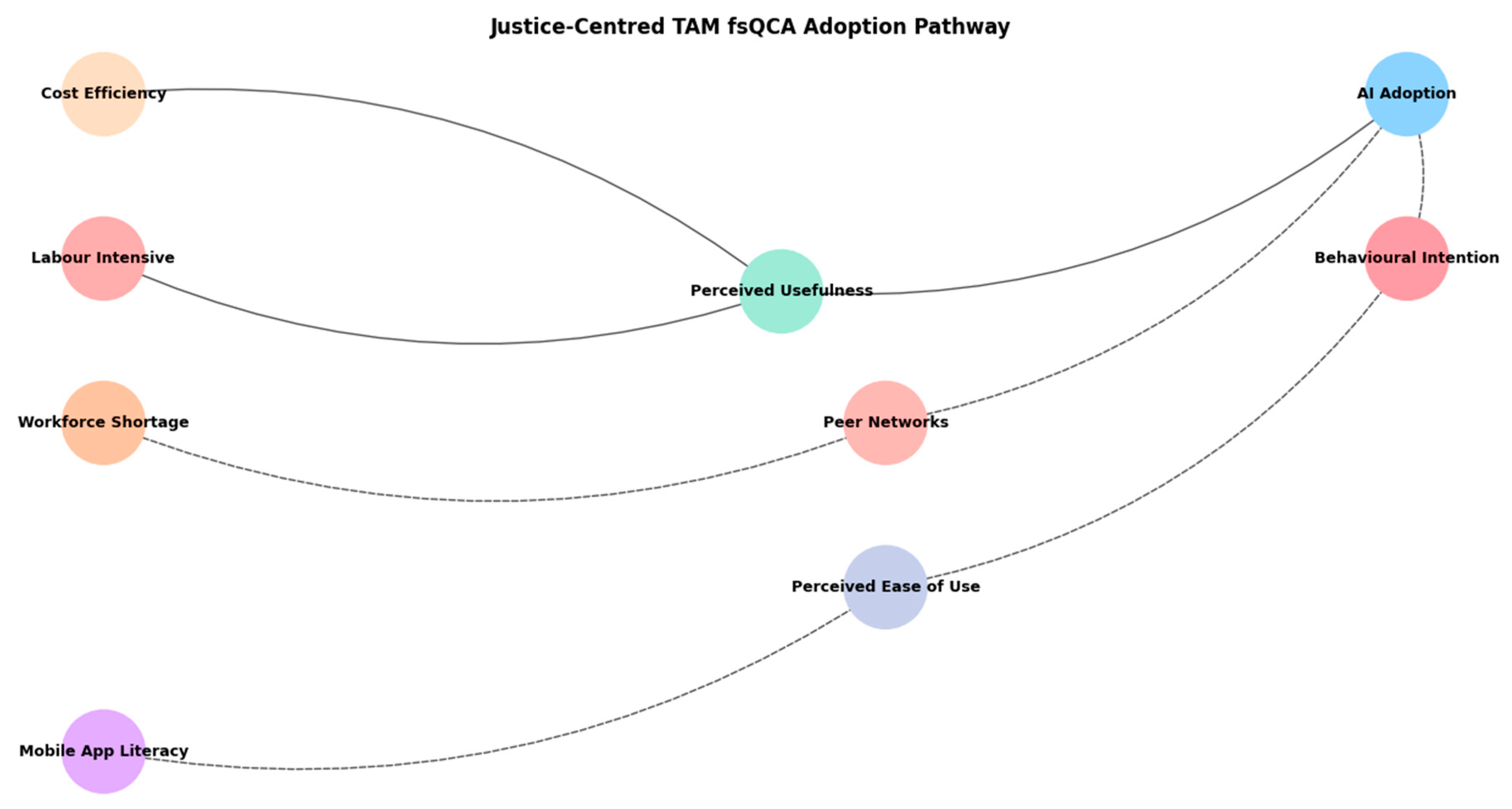

Figure 12.

Visualising the TAM Pathway:.

Figure 12.

Visualising the TAM Pathway:.

Looking ahead, the role of AI in NCAM is expected to evolve from an experimental phase to systemic integration as early adopters influence wider farming communities. Peer testimonials have been instrumental, with 68% of adopting farmers citing them as key in their decision to adopt AI. However, this transition is contingent upon policymakers and developers recognising that equitable adoption requires addressing structural barriers with the same rigour as technological design. As our justice-centred framework illustrates, the pathway to adoption is shaped by both TAM constructs such as perceived usefulness and ease of use (solid lines) and contextual equity mediators like labour justice, peer networks, and digital inclusion (dashed lines). These elements must be considered in tandem to ensure that AI innovations are not only technically effective but also socially just and locally grounded.

8.5. Aligning with Tamil Nadu’s Organic Farming Policy (2023)

This study’s evidence-based strategies align closely with the Tamil Nadu Organic Farming Policy(Agriculture-Farmers Welfare Department, 2023), offering clear pathways for implementation:

-

Soil Health and NCAM Adoption (Policy Objective 1.2)

-

AI-Enabled Resource Optimisation (Policy Objective 2.1)

-

Institutional Reform (Policy Objective 5.4)

-

Justice-Centred Implementation Framework

Labour-Responsive AI: Tools must support women’s collectives without displacing labour.

Two-Track Inclusion: Pair digital tools with local radio for knowledge dissemination.

Subsidy Redistribution: Shift incentives from inputs to NCAM and climate-smart tech.

8.6. Limitations and Future Research

This study centres farmer perspectives, offering grounded insights into real-world challenges. However, it omits the views of policymakers, technologists, and agricultural scientists. Future studies should integrate these actors to assess implementation readiness and infrastructural needs. Furthermore, understanding regional variations within Tamil Nadu could inform context-specific strategies for scaling AI and NCAM adoption.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, A.A.A.; supervision, I.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by INDIAN COUNCIL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH, CENTRALLY ADMINISTERED FULL-TERM DOCTORAL FELLOWSHIP, grant number: File No. RFD/2021-2022/GEN/MED/317.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Anna University, Chennai, India (Protocol Code: AU/Ethics/2021/093; Date of Approval: 15 March 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent was also obtained from the participants for publication of any potentially identifiable data.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the support of the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR) for awarding the Centrally Administered Full-Term Doctoral Fellowship (2021–2023), which enabled the successful completion of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence (AI) |

| BI |

Behavioural Intension |

| CSA |

climate-smart agriculture |

| DA |

Discourse Analysis |

| EV |

External Variable |

| FGD |

Focus Group Discussion |

| fsQCA |

Fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis |

| ICT |

Information and Communication Technology |

| NCAM |

Non-Chemical Agricultural Methods |

| PEU |

Perceived Ease of Use |

| PU |

Perceived Usefulness |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| TAM |

Technology Adoption Model |

References

- Agriculture-Farmers Welfare Department. (2023). Tamil Nadu Organic Farming Policy. https://agritech.tnau.ac.in/pdf/66617733-Tamil-Nadu-Organic-Farming-Policy-2023_230315_093042.pdf.

- Ahmed, I., Jeon, G., & Piccialli, F. (2022). From artificial intelligence to Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Industry 4.0: A Survey on What, How, and Where. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON INDUSTRIAL INFORMATICS, 18(740006), 16–19.

- Akash, J. H., & Aram, I. A. (2022). A convergent parallel mixed method of study for assessing the role of communication in community participation towards sustainable tourism. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 24(11), 12672–12690. [CrossRef]

- Amalan, A. A., & Aram, I. A. (2023). Media influence in agriculture practices and scopes for non-chemical agricultural messages. Communications in Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(2), 43–47. [CrossRef]

- Andujar, D. (2023). Back to the Future: What Is Trending on Precision Agriculture? Agronomy, 13(8). [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, A., Bondori, A., Allahyari, M. S., & Surujlal, J. (2021). Use of biologic inputs among cereal farmers: application of technology acceptance model. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 23(4), 5165–5181. [CrossRef]

- Benbrook, C., Kegley, S., & Baker, B. (2021). Organic farming lessens reliance on pesticides and promotes public health by lowering dietary risks. Agronomy, 11(7), 1–36. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [CrossRef]

- Bronson, K., & Knezevic, I. (2016). Big Data in food and agriculture. Big Data and Society, 3(1), 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Büyüközkan, G., & Uztürk, D. (2024). Integrated design framework for smart agriculture: Bridging the gap between digitalization and sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 449(September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. J., Huang, Y. Y., Li, Y. S., Chang, C. Y., & Huang, Y. M. (2020). An AIoT Based Smart Agricultural System for Pests Detection. IEEE Access, 8, 180750–180761. [CrossRef]

- Chindasombatcharoen, N., Tsolakis, N., Kumar, M., & O’Sullivan, E. (2024). Navigating psychological barriers in agricultural innovation adoption: A multi-stakeholder perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 475(March), 143695. [CrossRef]

- Cook, N. J. (2024). Experimental evidence on minority participation and the design of community-based natural resource management programs. Ecological Economics, 218(May 2023), 108114. [CrossRef]

- Cubric, M. (2020). Drivers, barriers and social considerations for AI adoption in business and management: A tertiary study. Technology in Society, 62(March), 101257. [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [CrossRef]

- Elbasi, E., Mostafa, N., Alarnaout, Z., Zreikat, A. I., Cina, E., Varghese, G., Shdefat, A., Topcu, A. E., Abdelbaki, W., Mathew, S., & Zaki, C. (2023). Artificial Intelligence Technology in the Agricultural Sector: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access, 11(January), 171–202. [CrossRef]

- Finger, R. (2023). Digital innovations for sustainable and resilient agricultural systems. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 50(4), 1277–1309. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. (1995). Debate: Recognition or Redistribution? A Critical Reading of Iris Young’s Justice and the Politics of Difference. The Journal of Political Philosophy, 3(2), 166–180.

- Gandhi, P. B., & Parejiya, A. (2023). The Power of Ai In Addressing The Challenges Faced By Indian Farmers In The Agriculture Sector: An Analysis. In Tuijin Jishu/Journal of Propulsion Technology (Vol. 44, Issue 4, pp. 4753–4777). [CrossRef]

- Gardezi, M., Joshi, B., Rizzo, D. M., Ryan, M., Prutzer, E., Brugler, S., & Dadkhah, A. (2023). Artificial intelligence in farming: Challenges and opportunities for building trust. Agronomy Journal, 116(3), 1217–1228. [CrossRef]

- Gomiero, T., Pimentel, D., & Paoletti, M. G. (2011). Environmental impact of different agricultural management practices: Conventional vs. Organic agriculture. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences, 30(1–2), 95–124. [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, A., Fister, I., Fister, I., Kaul, H. P., & Asseng, S. (2024). Human-Centered AI in Smart Farming: Toward Agriculture 5.0. IEEE Access, 12(May), 62199–62214. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M., Bijjahalli, S., Fahey, T., Gardi, A., Sabatini, R., & Lamb, D. W. (2024). Destructive and non-destructive measurement approaches and the application of AI models in precision agriculture: a review. In Precision Agriculture (Vol. 25, Issue 3). Springer US. [CrossRef]

- Karan, E., & Asgari, S. (2021). Resilience of food, energy, and water systems to a sudden labor shortage. Environment Systems and Decisions, 41(1), 63–81. [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L., Jakku, E., & Labarthe, P. (2019). A review of social science on digital agriculture, smart farming and agriculture 4.0: New contributions and a future research agenda. NJAS - Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 90–91, 100315. [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S., Ribeiro-Soriano, D., & Schüssler, M. (2018). Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) in entrepreneurship and innovation research – the rise of a method. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14(1), 15–33. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R., Kumar, S., Yashavanth, B. S., Venu, N., Meena, P. C., Dhandapani, A., & Kumar, A. (2023). Natural Farming Practices for Chemical-Free Agriculture: Implications for Crop Yield and Profitability. Agriculture (Switzerland), 13(3). [CrossRef]

- Laskar, M. H. (2023). Examining the emergence of digital society and the digital divide in India: A comparative evaluation between urban and rural areas. Frontiers in Sociology, 8. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Xu, Y., Engel, B. A., Sun, S., Zhao, X., Wu, P., & Wang, Y. (2021). The impact of urbanization and aging on food security in developing countries: The view from Northwest China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 292, 126067. [CrossRef]

- Lochmiller, C. R. (2021). Conducting thematic analysis with qualitative data. Qualitative Report, 26(6), 2029–2044. [CrossRef]

- Marangunić, N., & Granić, A. (2014). Technology acceptance model: a literature review from 1986 to 2013. Universal Access in the Information Society, 14(1), 81–95. [CrossRef]

- McGuire, E., Al-Zu’bi, M., Boa-Alvarado, M., Luu, T. T. G., Sylvester, J. M., & Leñero, E. M. V. (2024). Equity principles: Using social theory for more effective social transformation in agricultural research for development. Agricultural Systems, 218(September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Meena, R. S., Kumar, S., Datta, R., Lal, R., Vijayakumar, V., Brtnicky, M., Sharma, M. P., Yadav, G. S., Jhariya, M. K., Jangir, C. K., Pathan, S. I., Dokulilova, T., Pecina, V., & Marfo, T. D. (2020). Impact of agrochemicals on soil microbiota and management: A review. Land, 9(2), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Mohr, S., & Kühl, R. (2021). Acceptance of artificial intelligence in German agriculture: an application of the technology acceptance model and the theory of planned behavior. Precision Agriculture, 22(6), 1816–1844. [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, S., Zhang, W., Shehzad, M. U., Anwar, A., & Rubakula, G. (2022). Does Health Consciousness Matter to Adopt New Technology? An Integrated Model of UTAUT2 With SEM-fsQCA Approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(February), 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Nyumba, T. O., Wilson, K., Derrick, C. J., & Mukherjee, N. (2018). The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9(1), 20–32. [CrossRef]

- Patel, S. K., Sharma, A., & Singh, G. S. (2020). Traditional agricultural practices in India: an approach for environmental sustainability and food security. Energy, Ecology and Environment, 5(4), 253–271. [CrossRef]

- Paudel, S., Sah, L. P., Devkota, M., Poudyal, V., Prasad, P. V. V., & Reyes, M. R. (2020). Conservation agriculture and integrated pest management practices improve yield and income while reducing labor, pests, diseases and chemical pesticide use in smallholder vegetable farms in Nepal. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(16). [CrossRef]

- Phillips, N., Lawrence, T. B., & Hardy, C. (2004). Discourse and institutions. Academy of Management Review, 29(4), 636–652. [CrossRef]

- Pierpaoli, E., Carli, G., Pignatti, E., & Canavari, M. (2013). Drivers of Precision Agriculture Technologies Adoption: A Literature Review. Procedia Technology, 8(Haicta), 61–69. [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C. C. (2008). Redesigning social inquiry: Fuzzy sets and beyond. University of Chicago Press.

- Ryan, G. W., & Bernard, H. R. (2003). Techniques to Identify Themes. Field Methods, 15(1), 85–109. [CrossRef]

- Sachithra, V., & Subhashini, L. D. C. S. (2023). How artificial intelligence uses to achieve the agriculture sustainability: Systematic review. Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture, 8, 46–59. [CrossRef]

- Saiz-Rubio, V., & Rovira-Más, F. (2020). From smart farming towards agriculture 5.0: A review on crop data management. Agronomy, 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A., Jain, A., Gupta, P., & Chowdary, V. (2021). Machine Learning Applications for Precision Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Access, 9, 4843–4873. [CrossRef]

- Spanaki, K., Sivarajah, U., Fakhimi, M., Despoudi, S., & Irani, Z. (2021). Disruptive technologies in agricultural operations: a systematic review of AI-driven AgriTech research. In Annals of Operations Research (Vol. 308, Issues 1–2). Springer US. [CrossRef]

- Šūmane, S., Kunda, I., Knickel, K., Strauss, A., Tisenkopfs, T., Rios, I. des I., Rivera, M., Chebach, T., & Ashkenazy, A. (2018). Local and farmers’ knowledge matters! How integrating informal and formal knowledge enhances sustainable and resilient agriculture. Journal of Rural Studies, 59, 232–241. [CrossRef]

- Thanki, H., Shah, S., Oza, A., Vizureanu, P., & Burduhos-Nergis, D. D. (2022). Sustainable Consumption: Will They Buy It Again? Factors Influencing the Intention to Repurchase Organic Food Grain. Foods, 11(19), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Tzachor, A. (2021). Barriers to AI Adoption in Indian Agriculture. International Journal of Innovation in the Digital Economy, 12(3), 30–44. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (2000). Theoretical extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science, 46(2), 186–204. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 27(3), 425–478. [CrossRef]

- Wood, B. A., Blair, H. T., Gray, D. I., Kemp, P. D., Kenyon, P. R., Morris, S. T., & Sewell, A. M. (2014). Agricultural science in the wild: A social network analysis of farmer knowledge exchange. PLoS ONE, 9(8). [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., Aravecchia, S., Lottes, P., Stachniss, C., & Pradalier, C. (2020). Robotic weed control using automated weed and crop classification. Journal of Field Robotics, 37(2), 322–340. [CrossRef]

- Zerfass, A., & Huck, S. (2007). Innovation, Communication, and Leadership: New Developments in Strategic Communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 1(2), 107–122. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z., Zahid, U., Majeed, Y., Nisha, Mustafa, S., Sajjad, M. M., Butt, H. D., & Fu, L. (2023). Advancement in artificial intelligence for on-farm fruit sorting and transportation. Frontiers in Plant Science, 14(April), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Zul Azlan, Z. H., Junaini, S. N., Bolhassan, N. A., Wahi, R., & Arip, M. A. (2024). Harvesting a sustainable future: An overview of smart agriculture’s role in social, economic, and environmental sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 434(June 2023), 140338. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).