1. Introduction

Maintaining skeletal integrity and mineral homeostasis is crucial for overall health, as disruptions in these processes underlie a range of debilitating bone disorders. Central to this dynamic balance is bone remodeling, a continuous and tightly regulated physiological process involving the coordinated activity of osteocytes, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts [

1,

2]. Among these, osteocytes, the most abundant cell types in bone tissue, play a pivotal role in regulating both bone formation and resorption. Once considered passive, osteocytes are now recognized as central orchestrators of bone remodeling, functioning through biochemical signaling and mechano-transduction [

3]. In response to mechanical and biochemical cues, osteocytes secrete substances such as sclerostin, which inhibits bone growth, and prostaglandins and IGF-1, which promote bone growth [

4,

5]. Their extensive dendritic networks allow for intercellular communication across the bone matrix, ensuring synchronized remodeling activity [

6]. Mechanistically, osteocytes regulate osteoblast and osteoclast function via key signaling pathways, including Wnt/β-catenin and the OPG/RANKL axis [

7,

8].

The proper function of osteocytes is essential for preserving bone microarchitecture and systemic mineral homeostasis, especially for calcium and phosphate regulation [

8]. Dysregulation of osteocyte activity contributes to a spectrum of skeletal pathologies, such as osteoporosis and high bone mass syndrome. While significant advances have been made in understanding osteocyte biology, many regulatory mechanisms remain to be fully understood, which illustrates the importance of continued research and the integration of emerging technologies. To address these challenges, regenerative strategies have increasingly turned toward mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and their secreted extracellular vesicles, particularly exosomes. MSCs are multipotent cells capable of osteogenic differentiation and exert potent immunomodulatory effects [

9]. Their therapeutic potential has been demonstrated across a range of inflammatory and degenerative conditions [

10]. Notably, it is now widely recognized that MSCs exert many of their regenerative effects through exosomes—nanosized vesicles rich in proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids that facilitate paracrine signaling [

11]. MSC-derived exosomes are key mediators at the intersection of bone regeneration and immune modulation. They promote osteoblast proliferation and differentiation, deliver osteoinductive microRNAs, and facilitate osteocyte [

12,

13]. Additionally, they influence immune cell behavior by modulating cytokine release and promoting anti-inflammatory phenotypes [14-16]. These vesicles enhance regeneration, inhibit apoptosis, and stimulate angiogenesis in multiple disease models, making them an attractive cell-free therapeutic tool for musculoskeletal repair [

17,

18].

Emerging evidence also emphasizes the critical role of immunomodulation in bone homeostasis, particularly in osteocyte differentiation and function. The bidirectional communication between immune cells and bone-resident cells, a concept central to osteoimmunology, shapes the bone remodeling landscape. Cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and RANKL, produced by immune cells, directly influence osteoclast and osteoblast activity [

19]. Both innate and adaptive immune cells, including macrophages, dendritic cells, T cells, and B cells, contribute to this tightly regulated interface [

20,

21]. MSC-derived exosomes further contribute to this immunomodulatory network. For instance, inflammatory preconditioning of MSCs can enhance the immunomodulatory content of exosomes, promote anti-inflammatory macrophage polarization, and favor osteogenesis while limiting bone resorption [

22,

23]. While balanced immune signaling supports osteocytes differentiation and bone regeneration, excessive or dysregulated immune activation can result in pathological bone loss, emphasizing the importance of immune homeostasis in skeletal health [

24].

2. Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Exosomes: An Overview

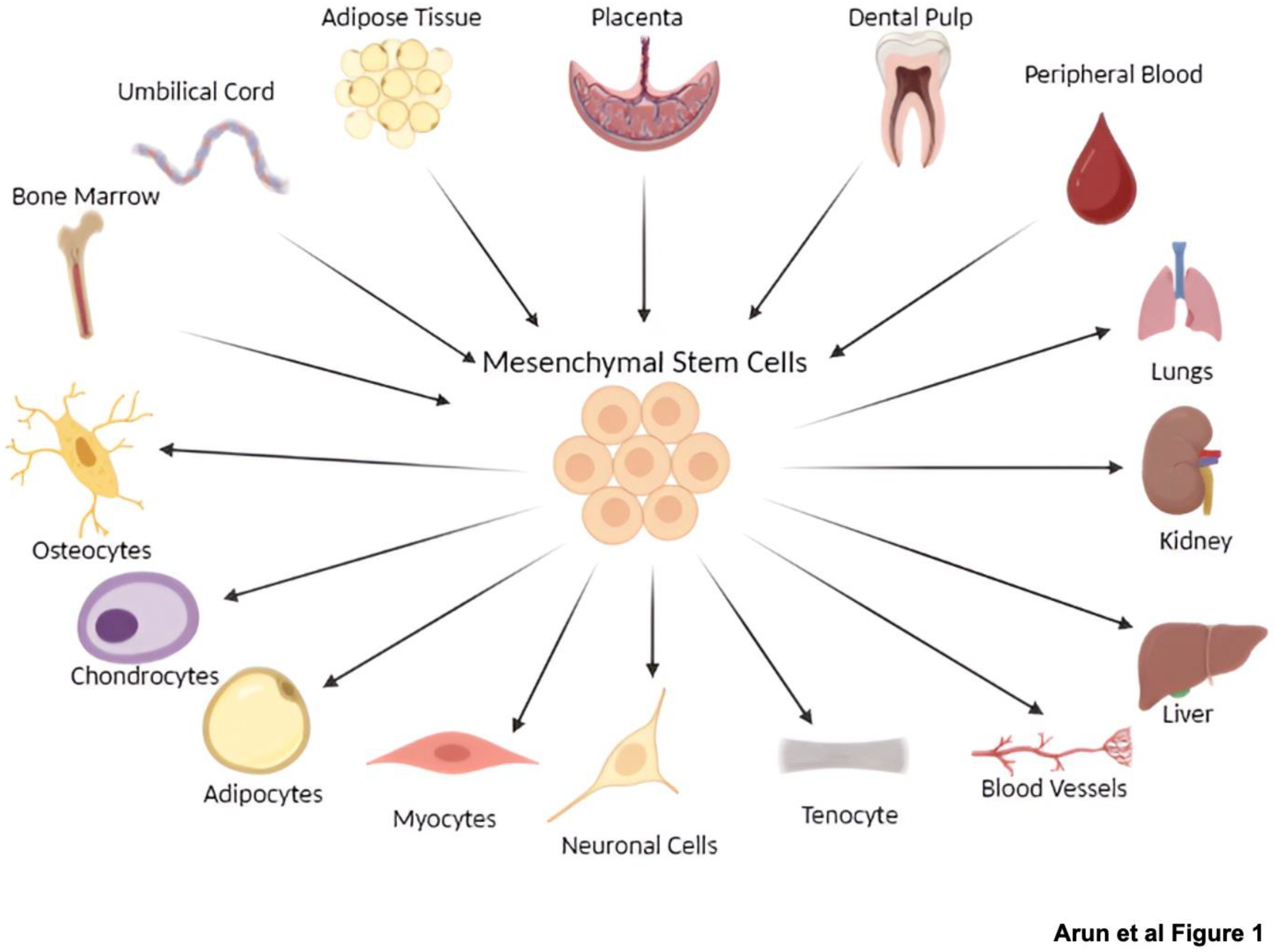

MSCs are known for their extensive proliferation capacity and trilineage differentiation ability into osteocytes, adipocytes, and chondrocytes [25-27], which is summarized in

Figure 1. In vitro, MSCs are characterized by their adherence to plastic surfaces and the expression of specific cell surface positive markers such as CD73, CD90, and CD105, and negative markers CD45 and CD34 [25-27]. In addition to their multilineage differentiation potential, MSCs exhibit significant immunomodulatory properties and robust self-renewal capabilities, making them highly suitable for a wide range of therapeutic applications due to their accessibility and expandability [

26,

27].

MSCs can be isolated from various sources, broadly categorized into adult, perinatal, and dental tissues. Common adult sources include bone marrow MSCs (BM-MSCs) and adipose tissue MSCs (AD-MSCs) [25-27]. Perinatal sources, such as umbilical cord blood and Wharton’s offer MSCs with superior proliferative potential and lower immunogenicity [

25,

26]. These varied origins and the associated differentiation capacities are comprehensively illustrated in

Figure 1. Dental-derived MSCs, such as those from the periodontal ligament, have recently gained interest for applications in regenerative dentistry [

28,

29].

Beyond direct MSC transplantation, increasing evidence highlights that their therapeutic benefits are significantly mediated through exosomes—nanoscale extracellular vesicles secreted by MSCs and other cell types [

30]. These nanovesicles are enriched with bioactive molecules, including proteins, lipids, messenger RNAs (mRNAs), and microRNAs (miRNAs) and play a critical role in intercellular communication and molecular trafficking under both physiological and pathological conditions [

30]. Their cargo is dynamically modulated by cellular stress, such as oxidative or thermal stimuli, enabling exosomes to influence recipient cell behavior, promote homeostasis, and mitigate tissue damage [

30]. MSC-derived exosomes have emerged as key paracrine mediators in regenerative medicine, facilitating tissue repair by transferring signaling molecules that influence proliferation, differentiation, and immune responses [

30]. These exosomes are also being explored as diagnostic biomarkers. Furthermore, advancements in exosomal bioengineering now allow for the precise delivery of therapeutic agents, positioning them as highly promising tools for targeted interventions [

30,

31]. Owing to their rich cargo of growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and other extracellular vesicles, they actively shape a regenerative microenvironment [

25,

27]. Compared to cell-based therapies, exosome-based strategies offer distinct advantages, including reduced immunogenicity, lower tumorigenic risk, and fewer ethical concerns [

32,

33].

A groundbreaking advancement in the field of stem cell biology is the advent of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), generated through the epigenetic reprogramming of somatic cells [

26,

29]. These reprogrammed iPSCs can differentiate into multiple lineages, including iPSC-derived MSCs (iMSCs) [

26,

29], which serve as a renewable, patient-specific source for autologous therapies [

26]. Compared to adult MSCs, iMSCs offer enhanced proliferative capacity, greater cellular heterogeneity, and potent anti-inflammatory properties [

29,

34]. While the direct application of iMSCs in bone regeneration is well documented, their secretome, particularly exosomes, plays an equally vital role [

25,

35]. Although the application of iMSC-derived exosomes in bone regeneration remains unexplored, their similarity to conventional MSC-derived exosomes suggests that they may possess enhanced therapeutic potential due to the superior attributes of their parental cells [

30,

36]. Given their ability to regulate stress responses and foster tissue homeostasis, iMSC-derived exosomes represent a promising next-generation, cell-free approach for advanced bone repair and regeneration therapies.

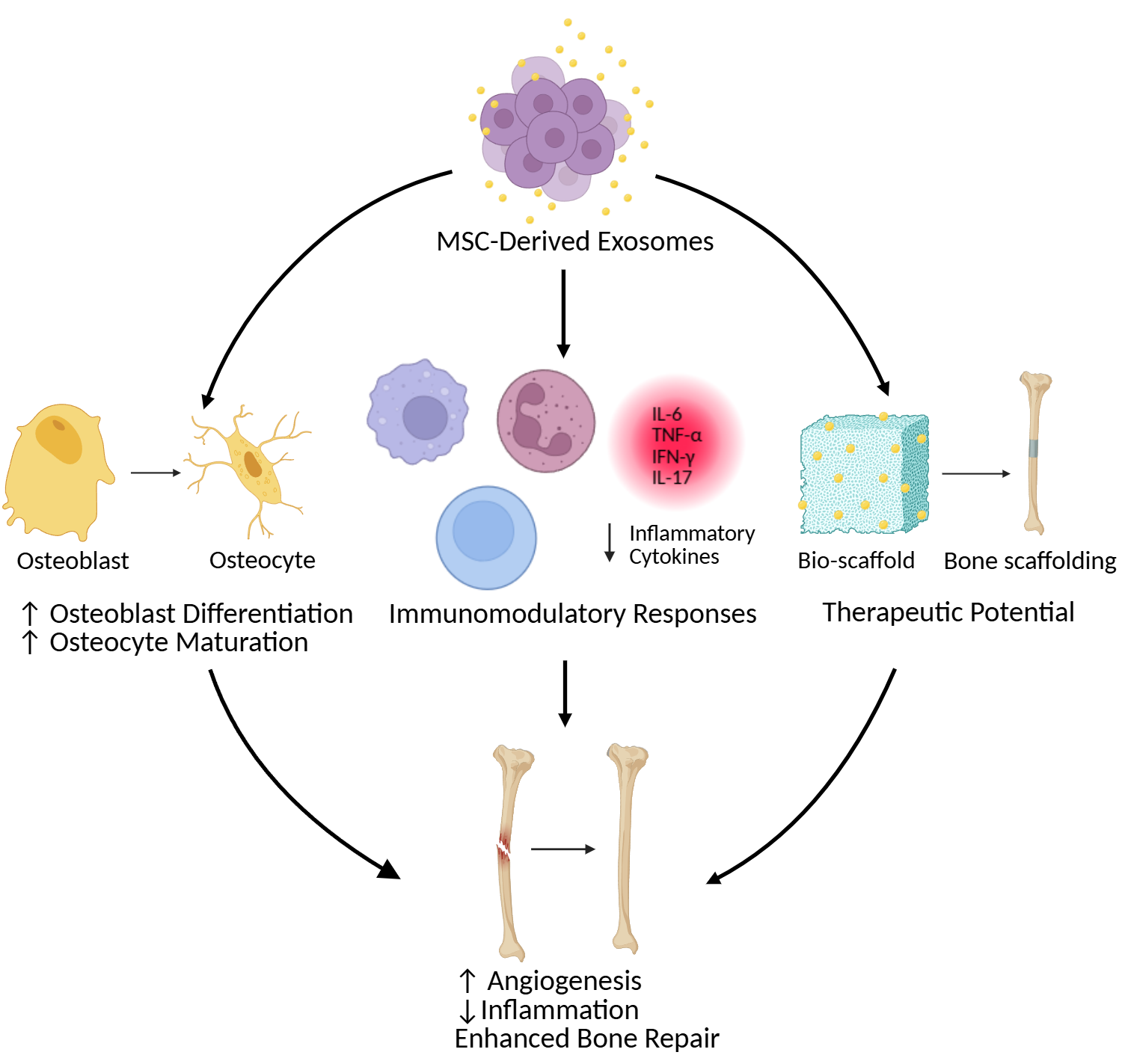

2. MSC-Derived Exosomes in Bone Regeneration

Several in vitro studies have demonstrated that MSC-derived exosomes enhance the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts, the cells responsible for new bone formation [

37,

38]. These exosomes deliver specific miRNAs that promote osteogenic gene expression and suppress negative regulators of bone formation, thereby influencing osteoblast maturation into osteocytes. For instance, exosomal miR-21 enhances osteoblast proliferation and differentiation by modulating the TGF-β signaling pathway, which also plays a crucial role in osteocyte differentiation. Similarly, miR-29a has been shown to promote osteoblast differentiation and extracellular matrix mineralization, indirectly supporting a favorable microenvironment for osteocyte maturation [

39]. In addition to osteogenesis, MSC-derived exosomes also stimulate angiogenesis, a key process for delivering oxygen and nutrients to regenerating bone tissue, thereby supporting both osteoblast and osteocyte survival and function [

40,

41] (

Table 1).

In vivo studies using animal models of bone defects have further supported the bone-regenerative potential of MSC-derived exosomes. Both local and systemic administration of these vesicles has been shown to accelerate bone repair, increase bone volume, and improve the mechanical strength of newly formed bone [

18,

42]. These outcomes are crucial for restoring the structural integrity and long-term function of bone tissue, which is critically dependent on a well-maintained osteocyte network. Furthermore, MSC-derived exosomes help modulate the inflammatory response at the defect site, creating a more favorable environment for tissue regeneration [

43,

44,

45] (

Table 2).

The therapeutic efficacy of MSC-derived exosomes in bone regeneration can be further enhanced through strategies such as preconditioning MSCs with specific growth factors or cytokines before exosome isolation [

22,

46,

47]. This approach can enrich the exosomal cargo with pro-osteogenic and pro-angiogenic factors, thereby improving their regenerative potential [

23]. While current preconditioning strategies primarily focus on enhancing osteoblast activity and bone formation, future efforts may target osteocyte-specific pathways to optimize outcomes in bone regeneration. Additionally, strategies include loading exosomes with therapeutic agents or engineering their surfaces to improve targeted delivery to bone tissues [

48,

49,

50,

51]. The cell-free nature of MSC-derived exosomes offers several advantages over direct MSC transplantation, including lower immunogenicity, reduced risk of tumorigenesis, and fewer off-target effects [

32,

52]. These benefits make exosome-based therapies a compelling and safe approach for regenerating healthy, functional bone tissue.

3. Immunomodulatory Properties of MSC-Derived Exosomes

MSC-derived exosomes play a crucial role in bone regeneration by mediating communication within the skeletal microenvironment and influencing key processes such as the transition of osteoblasts to osteocytes. These vesicles deliver bioactive molecules, including proteins, RNAs, and lipids, that regulate the behavior of recipient cells and support bone healing and remodeling [

13,

53]. Through paracrine signaling, MSC-exosomes promote osteoblast differentiation into osteocytes; they contribute to bone homeostasis and mineralization [

12,

54]. Furthermore, they enhance neovascularization and modulate local immune responses, both of which are vital for effective bone repair [

53,

55]. These regenerative mechanisms include the transfer of microRNAs and proteins that influence gene expression, cell proliferation, and lineage commitment, while also interacting with osteoclasts and osteocytes to maintain skeletal balance [

53,

54,

56]. Despite this promise, the translation of these findings into clinical therapies remains a challenge, owing to the complexity of exosome biology and the standardization of their production.

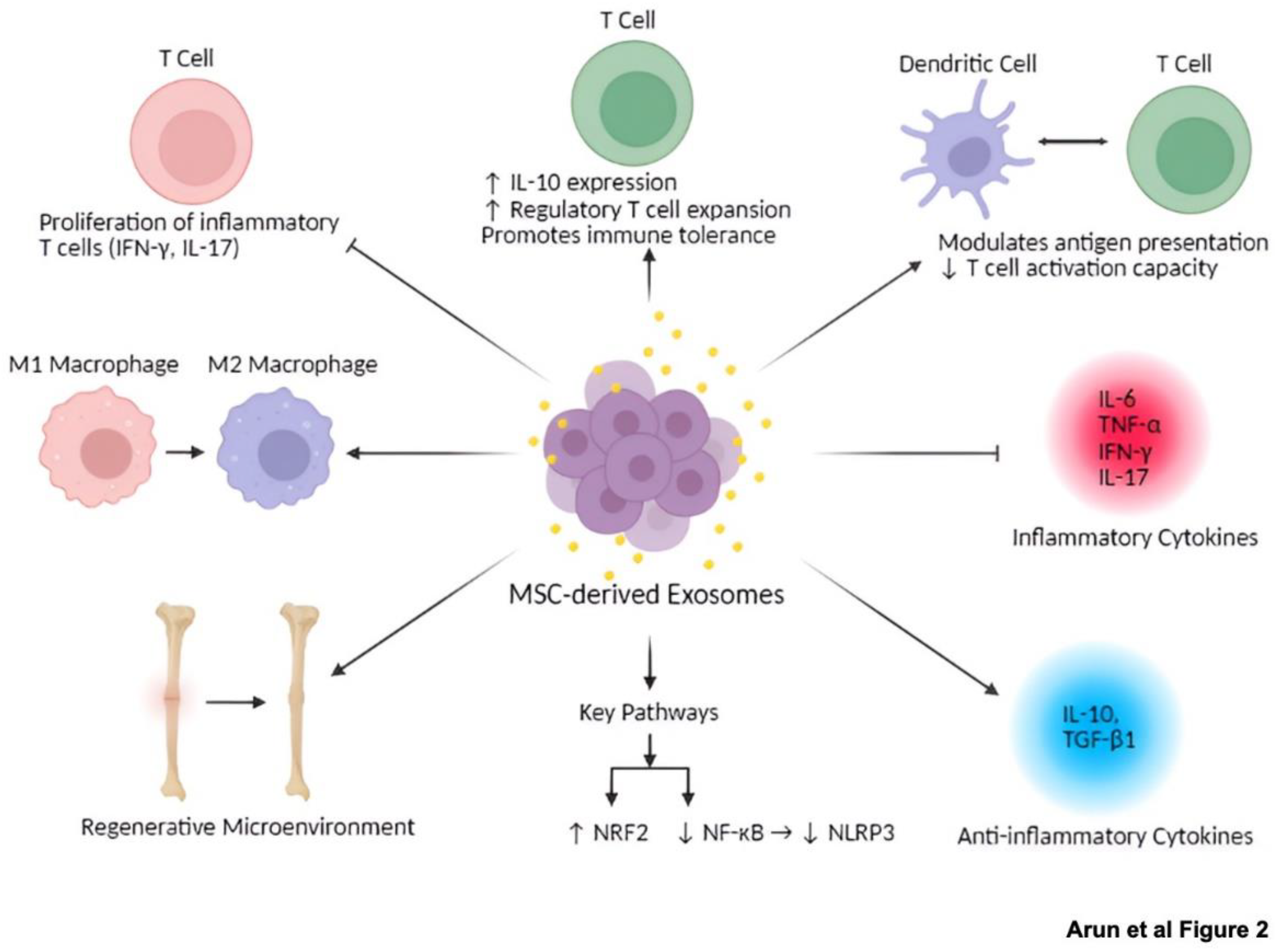

MSC-derived exosomes also exhibit profound immunomodulatory properties by targeting key immune cells such as macrophages, T cells, and dendritic cells, which has important implications for bone regeneration and immune-mediated bone diseases. The intricate mechanisms through which these exosomes exert their immunomodulatory effects, crucial for bone regeneration and immune-mediated bone diseases (

Figure 2). In macrophages, exosomes can polarize cells toward either pro-inflammatory (M1) or anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotypes, depending on the microenvironment. This plasticity is crucial for resolving inflammation and promoting regeneration in conditions such as atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and bone healing [

57,

58]. Our group has shown that iMSCs derived from periodontal ligament fibroblasts exert potent anti-inflammatory effects [

29]. Moreover, iMSCs derived from urinary epithelial cells have been shown to enhance the differentiation of T cells into Foxp3 regulatory T cells (Tregs) in vitro and to therapeutically improve retinal immune function in vivo by increasing Tregs levels, thereby reducing inflammation and protecting against ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury-induced retinal degeneration [

59]. In contrast, tumor-derived exosomes often skew macrophages toward immunosuppressive phenotypes, supporting tumor progression and immune evasion [

60]. In T cells, tumor-derived exosomes expressing PD-L1 inhibit T cell activation and induce immune tolerance [

60], whereas immune-cell-derived exosomes can promote T cell activation and proliferation, making them useful in cancer immunotherapy [

61]. T cell modulation is also relevant in bone-related autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis. Exosomes also influence dendritic cell function by modulating antigen presentation and T cell activation capacity [

62]. Tumor-derived exosomes impair dendritic cell metabolism, thereby reducing their ability to activate T cells [

63]. Moreover, dendritic cells can also influence bone metabolism through crosstalk with osteoblasts and osteoclasts [

2,

64]. These dual roles of exosomes in promoting immune activation or suppression are highly context-dependent and highlight the importance of source-specific exosomal profiling for therapeutic applications.

MSC-derived exosomes also exhibit both anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving effects essential for tissue repair. They suppress inflammatory T cell subsets producing interferon-γ and IL-17 while enhancing the production of IL-10, thereby shifting immune responses toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype [

14]. In neuroinflammatory models, tMSC-derived exosomes reduce proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α and promote M2 macrophage polarization, supporting tissue repair [

15]. These actions are mediated through pathways such as NRF2/NF-κB/NLRP3, where exosomes upregulate NRF2 and inhibit NF-κB, facilitating inflammation resolution [

15]. MSC-exosomes also facilitate the expansion of regulatory T cells and promote immune tolerance, which has therapeutic implications in autoimmune conditions such as multiple sclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease [

14,

65,

66]. The ability of MSC-derived exosomes to suppress and resolve inflammation enables a finely tuned immunological balance conducive to healing.

The immunoregulatory effects of MSC-derived exosomes are largely attributed to their cytokine and microRNA content. These exosomes suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IFN-γ while promoting anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10 and TGF-β1, thereby contributing to immune tolerance [16,67-70]. A comprehensive summary of these specific immunomodulatory effects on various immune cell types, including macrophages, T cells, and dendritic cells (

Table 3). They also carry angiogenic growth factors, including VEGF and HGF, which support neovascularization and tissue repair [

71]. He et al. (2024) found that miR-540-3p modulates dendritic cells and T cell responses through the CD74/NF-κB axis, enhancing immune tolerance and reducing graft rejection [

16]. It has been reported that miRNAs such as miR-3940-5p, miR-22-3p, and miR-16-5p inhibit tumor proliferation and migration by targeting oncogenic pathways [

17]. Similarly, miRNAs such as miR-21, miR-146a, and miR-181 are involved in regulating inflammatory signaling and enhancing cell survival [

72,

73]. However, while these molecular mediators show therapeutic promise, it is important to note that MSC-derived exosomes can also contribute to immunosuppression in tumor settings [

60], necessitating cautious application in cancer-related contexts. The heterogeneity of exosome cargo and the variability of immune environments demonstrate the value of refined, targeted therapeutic strategies. For instance, our recent studies showed that dental pulp stem cell-derived exosomes (DPSC-Exo) accelerated periodontal tissue repair by converting pro-inflammatory macrophages to an anti-inflammatory response, thereby suppressing periodontal inflammation and modulating the immune response [

28]. These findings point out the importance of tailored exosome therapies in modulating local immune responses for tissue regeneration.

4. Evidence of MSC-Derived Exosomes Promoting Osteocyte Differentiation

Numerous in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that MSC-derived exosomes play a crucial role in regulating osteogenic processes, including osteoblast differentiation and the osteoblast-to-osteocyte transition [

74,

75]. For example, mechanically strained osteocytes release exosomes containing miRNAs such as miR-3110-5p and miR-3058-3p, which promote osteoblast differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells [

76]. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell (BMSC)-derived exosomes have also shown significant osteogenic potential [

58,

77,

78]. Wang et al. (2022) demonstrated that BMSC-derived exosomes increase alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity and upregulate RUNX2 expression in osteoprogenitor cells, thereby facilitating their differentiation into osteoblasts. Supporting these in vitro findings, in vivo studies using ovariectomized mouse models demonstrated that MSC-derived exosomes improve bone formation and increase bone mass, highlighting their therapeutic potential in treating osteoporosis and osteomyelitis [

56,

79,

80]. Furthermore, our laboratory has successfully generated iPSC-derived MSCs that differentiate into osteocytes, underscoring the potential of their exosomes to drive robust osteogenesis and support osteocyte maturation [

26,

29].

The differentiation stage of MSCs significantly influences the functional profile of their secreted exosomes in promoting osteogenesis. Wang et al. (2018) demonstrated that exosomes derived from MSCs at late-stage osteogenic differentiation enhance matrix mineralization and reinforce lineage commitment toward osteoblast maturation, which eventually become osteocytes [

81]. Conversely, Zhai et al. (2020) found that exosomes from MSCs at early osteogenic stages promote differentiation via activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway. These findings indicate that the timing of the exosome release critically shapes their osteogenic signaling and downstream effects on cells progressing toward the osteocyte lineage [

82]. In parallel, Liu et al. (2021) demonstrated that exosomal miR-20a enhances osteogenic differentiation by targeting BAMBI, a known inhibitor of TGF-β signaling, which is essential for both osteoblast and osteocyte maturation [

18].

The inflammatory microenvironment plays a major role in modulating the osteogenic effects of MSC-derived exosomes. Guo et al. (2022) demonstrated that pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α suppress osteogenesis by downregulating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and shifting MSC fate toward adipogenesis. However, MSC-derived exosomes can counteract these inhibitory effects [

17]. It has been reported that delivery of bioactive cargo stimulates osteoblast activity while concurrently suppressing osteogenic differentiation, thereby mitigating inflammation-induced inhibition of bone formation [

13]. Furthermore, a study has reported that exosomes from osteogenically differentiated MSCs enhance osteogenic markers such as ALP and BMP2, further promoting osteoblast lineage commitment [

38]. Another study mentioned that exosomes harvested from MSCs during early osteogenesis, enriched in bone-related proteins, significantly enhance osteogenic differentiation compared to naïve extracellular vesicles (EVs) [

83].

In vivo studies further support the regenerative potential of MSC-derived exosomes. It has been demonstrated that these exosomes significantly improved bone formation and integration with implants in osteoporotic rat models, confirming their efficacy in physiological systems [

18]. Moreover, the exosomes derived from younger plasma sources possess higher osteogenic potential than those from aged plasma, suggesting that donor age influences the therapeutic quality of exosomal content [

84].

Despite the promising outcomes, the precise mechanisms through which MSC-derived exosomes influence osteocyte differentiation and broader bone remodeling remain an area of active investigation. The heterogeneity of exosomal cargo, influenced by the MSC source and culture conditions, and the dynamic interplay with the inflammatory milieu present ongoing challenges. Further investigation is needed to delineate the molecular pathways governing exosome-mediated osteocyte maturation. Addressing these challenges, particularly through the development of targeted exosome delivery systems, could significantly improve the clinical utility of MSC-exosome therapies for inflammatory bone diseases and skeletal regeneration. Although much of the current literature focuses on the impact of MSC-derived exosomes on osteoblast proliferation and early differentiation, the transition toward fully mature osteocytes remains a critical frontier in regenerative research [

12,

13,

39]. Studies have shown that the successful generation of iPSC-derived MSCs capable of differentiating into osteocytes provides a strong foundation for future explorations into the role of exosomes in terminal osteocyte maturation [

26,

29,

85]. Ultimately, the capacity of MSC-derived exosomes to modulate osteogenic differentiation while mitigating inflammation represents a promising strategy for advancing regenerative medicine, especially in the context of musculoskeletal disorders.

5. Therapeutic Potential and Clinical Implications

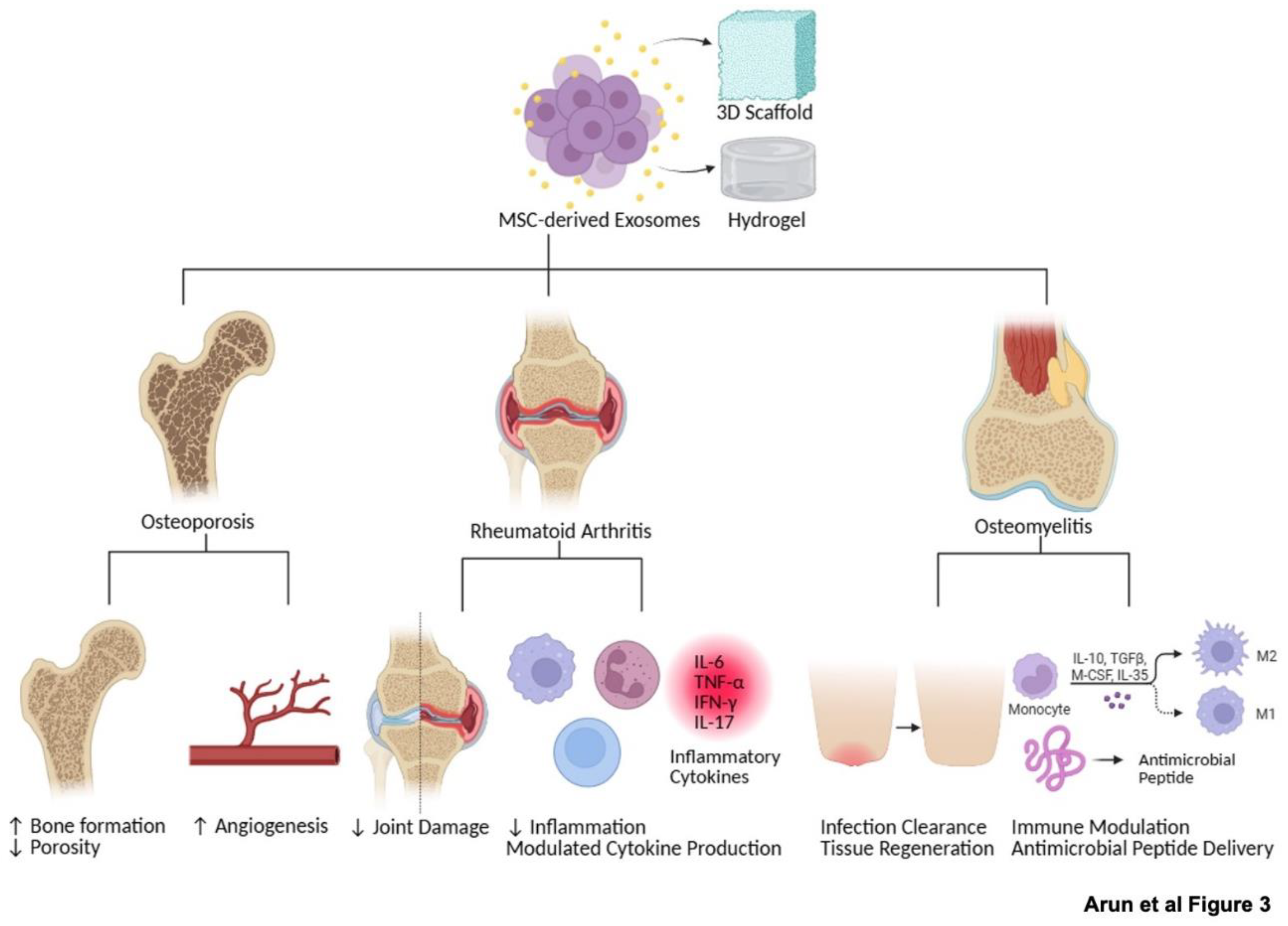

MSC-derived exosomes are increasingly recognized as a promising cell-free alternative to MSC transplantation for bone regeneration. Their therapeutic potential, underscored by numerous preclinical findings (

Table 2), allows them to encapsulate the benefits of MSCs while circumventing risks associated with live cell therapy, such as tumorigenicity, immune rejection, and ethical concerns [

32,

33]. Replicating the anti-inflammatory, osteoinductive, and angiogenic functions of MSCs, exosome-based therapies offer a more controllable and safer approach for treating skeletal disorders.

Their small size and intrinsic tissue tropism enable MSC-exosomes to efficiently deliver therapeutic cargo—such as microRNAs, proteins, and lipids—to sites of injury and regeneration, including bone [

86,

87]. This makes them particularly suited for targeting the bone microenvironment. Their diverse and impactful effects on bone regeneration, encompassing osteogenesis, angiogenesis, and the modulation of inflammation (

Table 4). Current research is actively exploring the engineering of exosomal surfaces with bone-homing peptides to enhance targeting specificity and retention at skeletal sites. Furthermore, exosomes exhibit excellent stability in circulation and can cross biological barriers, increasing their clinical utility for both systemic and local administration. Despite these advantages, several challenges remain. The heterogeneity of exosomal cargo and lack of standardized production protocols can affect consistency and reproducibility. Additionally, the precise mechanisms by which MSC-exosomes exert their therapeutic effects in bone tissues are still being elucidated. Addressing these gaps will be critical for optimizing their clinical application.

One promising avenue to enhance therapeutic efficacy, as further explored in the diverse applications (

Figure 3), involves the integration of MSC-exosomes with biomaterial scaffolds. Advanced delivery systems—such as hydrogels, collagen sponges, and 3D-printed scaffolds—can enable the sustained and localized release of exosomes at the site of bone injury [

43]. These scaffolds not only improve the retention and bioavailability of exosomes but also provide mechanical support and structural cues for tissue regeneration. MSC-exosomes embedded in such scaffolds deliver bioactive molecules, including osteogenic miRNAs, growth factors, and immunomodulatory proteins, which promote angiogenesis, modulate inflammation, and enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone matrix deposition [

12,

13,

39,

53,

81].

Importantly, these exosome-functionalized scaffolds offer an attractive alternative to cell-based therapies by overcoming issues related to immune incompatibility, regulatory complexity, and storage logistics. The use of biocompatible and customizable scaffolds allows for precise control of exosome release kinetics and provides a versatile platform adaptable to patient-specific needs. Moreover, preconditioning MSCs with osteoinductive or neurotrophic agents—such as nerve growth factor (NGF)—has been shown to enrich the exosomal cargo, enhancing both neuroregenerative and osteogenic effects [

88]. This strategy may improve the maturation of osteoblasts into fully functional osteocytes and further support bone remodeling.

6. Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the compelling preclinical evidence supporting the osteoinductive and immunomodulatory capabilities of MSC-derived exosomes, several critical challenges hinder their clinical translation. A major limitation lies in the heterogeneity of exosomal cargo, which is profoundly influenced by the MSC source, culture conditions, and the stage of differentiation [

89,

90]. This variability undermines reproducibility across studies and complicates the consistency of therapeutic outcomes, particularly in bone regeneration. However, our work with iPSC-derived MSCs shows promise that these cells maintain stable characteristics and chromosomal integrity even at later passages, offering a more uniform and scalable source for exosome production [

26]. Another challenge stems from the species-specific nature of bone biology research. Much of our current understanding of bone remodeling and osteocyte function is based on single-species studies, limiting the generalizability of findings. Comparative cross-species research is needed to define conserved mechanisms and translate findings more broadly [

91].

Critically, the role of MSC-exosomes in osteocyte differentiation remains underexplored. While numerous studies have demonstrated their effects on osteoblast proliferation and early-stage osteogenesis [

37,

38], the specific molecular mechanisms driving the osteoblast-to-osteocyte transition are poorly defined [

12,

13]. This knowledge gap is particularly significant given the central role of osteocytes in bone homeostasis, mechanotransduction, and skeletal disease pathophysiology [

8]. Moreover, the inflammatory microenvironment profoundly influences exosome function. Although MSC-derived exosomes can attenuate inflammation and promote bone repair, pathological conditions such as diabetes and osteoporosis alter their bioactive content, reducing efficacy [

37,

42]. Future work should focus on identifying disease-induced alterations in exosomal cargo and developing engineering strategies to enhance their regenerative potential even under such pathological conditions. Understanding how microenvironments modulate exosome function will be crucial for improving therapeutic precision, particularly regarding osteocyte differentiation and survival.

Further progress also requires advanced in vivo imaging and tracking systems. Although in vivo studies have shown improved bone formation and implant integration with MSC-exosome administration [

18,

42], the biodistribution and behavior of exosomes within the osteocyte network remain poorly understood. Innovations in high-resolution intravital microscopy and humanized bone models could provide unprecedented insights into how exosomes interact within the bone microenvironment. Coupling this with lineage-tracing tools could clarify their fate and mechanisms of action.

Another frontier involves targeted delivery strategies. Biomaterial scaffolds—such as hydrogels and 3D-printed constructs—have demonstrated potential for sustained localized exosome release [

43,

48]. However, ensuring compatibility between scaffold composition and exosome bioactivity remains a challenge. Future research should explore surface conjugation with bone-homing peptides and the use of stimuli-responsive biomaterials to achieve spatial and temporal precision in exosome release at sites of bone injury. Equally important is the need to standardize exosome isolation, characterization, and quantification protocols. Current methods—including ultracentrifugation, precipitation, and immunoaffinity capture—often result in inconsistent purity, yield, and functional activity [

92,

93]. Without universally accepted protocols, clinical scalability and inter-study comparisons remain limited. Addressing these issues will require coordinated, multi-institutional efforts to develop reproducible and regulatory-compliant standards for exosome manufacturing and quality control.

Lastly, the immunological context in which MSC-exosomes operate adds another layer of complexity. Their immunomodulatory effects vary with MSC source, tissue of origin, and the surrounding inflammatory cues [

15,

17]. Unraveling the specific receptors and signaling pathways mediating interactions between exosomes and immune cell subsets within the bone niche is essential for developing context-specific, disease-targeted therapies.

Looking forward, future research should prioritize three interconnected goals:

1) Dissecting the molecular pathways through which MSC-exosomes influence osteocyte differentiation and function.

2) Establishing standardized, scalable protocols for exosome production, purification, and characterization.

3) Innovating delivery systems—such as engineered scaffolds and targeting ligands—that maximize therapeutic precision.

Interdisciplinary collaboration across stem cell biology, biomaterials engineering, immunology, and regenerative orthopedics will be vital to overcome these challenges. Addressing them effectively could revolutionize musculoskeletal therapy, enabling the development of less invasive, more targeted, and highly personalized treatments for a wide range of bone-related disorders.

Nevertheless, several key questions remain unresolved. Identifying the optimal scaffold composition, loading strategies, and release profiles is essential for clinical translation. Additionally, understanding the interactions between exosomal cargo and resident bone cells at the molecular level will help refine therapeutic designs. Standardizing manufacturing processes for exosome isolation, characterization, and integration into biomaterials is another critical step toward regulatory approval and large-scale clinical deployment. In summary, MSC-derived exosomes, particularly when combined with bioengineered scaffolds, represent a cutting-edge approach to bone regeneration. Their immunomodulatory, osteogenic, and angiogenic properties—coupled with their safety and adaptability—highlight their strong translational promise. With continued refinement of delivery systems and mechanistic understanding, MSC-exosome-based therapies are poised to become a powerful tool in the clinical management of bone diseases.

7. Conclusion

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and their derived exosomes represent a promising frontier in regenerative medicine, particularly for their versatile roles in bone regeneration and immunomodulation. These naturally occurring nanocarriers facilitate intercellular communication by modulating osteoblast differentiation, osteocyte maturation, angiogenesis, and key immune responses within the bone microenvironment. Compared to traditional cell-based therapies, exosome-based approaches offer several advantages, including reduced immunogenicity and improved safety profiles.

However, significant challenges remain—most notably the need to standardize exosome production and characterization, address cargo heterogeneity, and enhance targeted delivery strategies. Future research must prioritize the elucidation of molecular mechanisms, the development of robust in vivo models, and the integration of interdisciplinary expertise spanning stem cell biology, biomaterials, and immunology. These efforts will be critical for advancing the clinical translation of MSC-derived exosome therapies and hold the potential to transform the treatment landscape for a wide range of musculoskeletal disorders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A., S.R., P.M., J.R.; Literature collection, M.A., S.R.; writing-original draft preparation, M.A., S.R.; writing—review and editing, J.R., P.M., S.R.; All authors have read and agreed to the current version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the American Heart Association Transformational Project Award 20TPA35490215 and the National Institute of Health R01 grant HL141345 to JR.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

All figures were created with Biorender.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article.

References

- Florencio-Silva, R.; Sasso, G.R.; Sasso-Cerri, E.; Simões, M.J.; Cerri, P.S. Biology of Bone Tissue: Structure, Function, and Factors That Influence Bone Cells. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, 421746. [CrossRef]

- Raggatt, L.J.; Partridge, N.C. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of bone remodeling. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 25103-25108. [CrossRef]

- Bonewald, L.F. The amazing osteocyte. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 2011, 26, 229-238. [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Helder, M.N.; Bravenboer, N.; Wu, G.; Jin, J.; Ten Bruggenkate, C.M.; Klein-Nulend, J.; Schulten, E. Is There a Governing Role of Osteocytes in Bone Tissue Regeneration? Curr Osteoporos Rep 2020, 18, 541-550. [CrossRef]

- Tresguerres, F.G.F.; Torres, J.; López-Quiles, J.; Hernández, G.; Vega, J.A.; Tresguerres, I.F. The osteocyte: A multifunctional cell within the bone. Ann Anat 2020, 227, 151422. [CrossRef]

- Marahleh, A.; Kitaura, H.; Ohori, F.; Noguchi, T.; Mizoguchi, I. The osteocyte and its osteoclastogenic potential. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1121727. [CrossRef]

- Du, J.H.; Lin, S.X.; Wu, X.L.; Yang, S.M.; Cao, L.Y.; Zheng, A.; Wu, J.N.; Jiang, X.Q. The Function of Wnt Ligands on Osteocyte and Bone Remodeling. J Dent Res 2019, 98, 930-938. [CrossRef]

- Niedźwiedzki, T.; Filipowska, J. Bone remodeling in the context of cellular and systemic regulation: the role of osteocytes and the nervous system. J Mol Endocrinol 2015, 55, R23-36. [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, M.H.; Kink, J.A.; Hematti, P.; Capitini, C.M. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and Exosomes: Progress and Challenges. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 8, 665. [CrossRef]

- Akbar, N.; Razzaq, S.S.; Salim, A.; Haneef, K. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes and Their MicroRNAs in Heart Repair and Regeneration. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2024, 17, 505-522. [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, A.; Rahman, H.S.; Markov, A.; Endjun, J.J.; Zekiy, A.O.; Chartrand, M.S.; Beheshtkhoo, N.; Kouhbanani, M.A.J.; Marofi, F.; Nikoo, M.; et al. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cell-derived exosomes in regenerative medicine and cancer; overview of development, challenges, and opportunities. Stem Cell Res Ther 2021, 12, 297. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, B.; Zhang, L. Exosome mediated biological functions within skeletal microenvironment. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10, 953916. [CrossRef]

- Torrecillas-Baena, B.; Pulido-Escribano, V.; Dorado, G.; Gálvez-Moreno, M.; Camacho-Cardenosa, M.; Casado-Díaz, A. Clinical Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes in Bone Regeneration. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Baharlooi, H.; Salehi, Z.; Minbashi Moeini, M.; Rezaei, N.; Azimi, M. Immunomodulatory Potential of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells and their Exosomes on Multiple Sclerosis. Adv Pharm Bull 2022, 12, 389-397. [CrossRef]

- Che, J.; Wang, H.; Dong, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fu, L.; Zhang, J. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes attenuate neuroinflammation and oxidative stress through the NRF2/NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway. CNS Neurosci Ther 2024, 30, e14454. [CrossRef]

- He, J.G.; Wu, X.X.; Li, S.; Yan, D.; Xiao, G.P.; Mao, F.G. Exosomes derived from microRNA-540-3p overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells promote immune tolerance via the CD74/nuclear factor-kappaB pathway in cardiac allograft. World J Stem Cells 2024, 16, 1022-1046. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Tan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Shi, F.; She, J. The therapeutic potential of stem cell-derived exosomes in the ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. Stem Cell Res Ther 2022, 13, 138. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Huang, J.; Chen, F.; Xie, D.; Wang, L.; Ye, C.; Zhu, Q.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Yang, L. MSC-derived small extracellular vesicles overexpressing miR-20a promoted the osteointegration of porous titanium alloy by enhancing osteogenesis via targeting BAMBI. Stem Cell Res Ther 2021, 12, 348. [CrossRef]

- Ponzetti, M.; Rucci, N. Updates on Osteoimmunology: What's New on the Cross-Talk Between Bone and Immune System. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019, 10, 236. [CrossRef]

- Ignatius, A.; Sobacchi, C. Editorial: Innate Immunity in the Context of Osteoimmunology. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 603. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhu, L. Osteoimmunology: The Crosstalk between T Cells, B Cells, and Osteoclasts in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Pajarinen, J.; Nabeshima, A.; Lu, L.; Nathan, K.; Jämsen, E.; Yao, Z.; Goodman, S.B. Preconditioning of murine mesenchymal stem cells synergistically enhanced immunomodulation and osteogenesis. Stem Cell Res Ther 2017, 8, 277. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shou, Z.; Xu, C.; Huo, K.; Liu, W.; Liu, H.; Zan, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, L. Enhancing the Implant Osteointegration via Supramolecular Co-Assembly Coating with Early Immunomodulation and Cell Colonization. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2025, 12, e2410595. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.C.; Shin, M.K.; Jang, B.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, M.; Sung, J.S. Immunomodulatory Effect and Bone Homeostasis Regulation in Osteoblasts Differentiated from hADMSCs via the PD-1/PD-L1 Axis. Cells 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Nitkin, C.R.; Rajasingh, J.; Pisano, C.; Besner, G.E.; Thébaud, B.; Sampath, V. Stem cell therapy for preventing neonatal diseases in the 21st century: Current understanding and challenges. Pediatr Res 2020, 87, 265-276. [CrossRef]

- Rajasingh, S.; Sigamani, V.; Selvam, V.; Gurusamy, N.; Kirankumar, S.; Vasanthan, J.; Rajasingh, J. Comparative analysis of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells and umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2021, 25, 8904-8919. [CrossRef]

- Vasanthan, J.; Gurusamy, N.; Rajasingh, S.; Sigamani, V.; Kirankumar, S.; Thomas, E.L.; Rajasingh, J. Role of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Regenerative Therapy. Cells 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.; Aghazadeh, M.; Rajasingh, S.; Dixon, D.; Jain, V.; Rajasingh, J. Stem cells in regenerative dentistry: Current understanding and future directions. J Oral Biosci 2024, 66, 288-299. [CrossRef]

- Vembuli, H.; Rajasingh, S.; Nabholz, P.; Guenther, J.; Morrow, B.R.; Taylor, M.M.; Aghazadeh, M.; Sigamani, V.; Rajasingh, J. Induced mesenchymal stem cells generated from periodontal ligament fibroblast for regenerative therapy. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2025, 250, 10342. [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.; Gurusamy, N.; Ulaganathan, T.; Paluck, A.J.; Ramalingam, S.; Rajasingh, J. Therapeutic potentials of stem cell-derived exosomes in cardiovascular diseases. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2023, 248, 434-444. [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S.; Rajasingh, S.; Drosos, N.; Zhou, Z.; Dawn, B.; Rajasingh, J. Exosomes: new molecular targets of diseases. Acta pharmacologica Sinica 2017. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.J.; Wei, R.; Li, F.; Liao, S.Y.; Tse, H.F. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes in cardiac regeneration and repair. Stem Cell Reports 2021, 16, 1662-1673. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.C.; Kang, I.; Yu, K.R. Therapeutic Features and Updated Clinical Trials of Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC)-Derived Exosomes. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Niho, S.; Shimizu, Y. Cell-Based Therapy for Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Diseases, Current Status, and Potential Applications of iPSC-Derived Cells. Cells 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Guan, J.; Niu, X.; Hu, G.; Guo, S.; Li, Q.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y. Exosomes released from human induced pluripotent stem cells-derived MSCs facilitate cutaneous wound healing by promoting collagen synthesis and angiogenesis. Journal of translational medicine 2015, 13, 49. [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.; Abadchi, S.N.; Shababi, N.; Ravari, M.R.; Pirolli, N.H.; Bergeron, C.; Obiorah, A.; Mokhtari-Esbuie, F.; Gheshlaghi, S.; Abraham, J.M.; et al. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Promote Wound Repair in a Diabetic Mouse Model via an Anti-Inflammatory Immunomodulatory Mechanism. Advanced healthcare materials 2023, 12, e2300879. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, B.; Shang, J.; Wang, Y.; Jia, L.; She, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, D.; Guo, J.; Zhang, F. Diabetic and nondiabetic BMSC-derived exosomes affect bone regeneration via regulating miR-17-5p/SMAD7 axis. Int Immunopharmacol 2023, 125, 111190. [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Li, Z.; Crawford, R.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, Y. Immunoregulatory role of exosomes derived from differentiating mesenchymal stromal cells on inflammation and osteogenesis. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2019, 13, 1978-1991. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Cao, H.; Hua, W.; Gao, L.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zeng, Z. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles for Bone Defect Repair. Membranes (Basel) 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Shen, H.; Xie, F.; Hu, D.; Jin, Q.; Hu, Y.; Zhong, T. Role of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in the regeneration of different tissues. J Biol Eng 2024, 18, 36. [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Lin, Y.; Liu, W.; Yang, L.; Zhao, M. MSC-Exos: Important active factor of bone regeneration. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2023, 11, 1136453. [CrossRef]

- Huo, K.L.; Yang, T.Y.; Zhang, W.W.; Shao, J. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells-derived exosomes for osteoporosis treatment. World J Stem Cells 2023, 15, 83-89. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liang, Y.; Luo, D.; Li, P.; Chen, Y.; Fu, X.; Yue, Y.; Hou, R.; Liu, J.; Wang, X. Advantages and disadvantages of various hydrogel scaffold types: A research to improve the clinical conversion rate of loaded MSCs-Exos hydrogel scaffolds. Biomed Pharmacother 2024, 179, 117386. [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.M.; Teixeira, J.H.; Almeida, M.I.; Gonçalves, R.M.; Barbosa, M.A.; Santos, S.G. Extracellular Vesicles: Immunomodulatory messengers in the context of tissue repair/regeneration. European journal of pharmaceutical sciences : official journal of the European Federation for Pharmaceutical Sciences 2017, 98, 86-95. [CrossRef]

- Phinney, D.G.; Pittenger, M.F. Concise Review: MSC-Derived Exosomes for Cell-Free Therapy. Stem Cells 2017, 35, 851-858. [CrossRef]

- Long, R.; Wang, S. Exosomes from preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells: Tissue repair and regeneration. Regen Ther 2024, 25, 355-366. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, L.; Rong, Y.; Qian, D.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Z.; Luo, Y.; Jiang, D.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, S.; et al. Hypoxic mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote bone fracture healing by the transfer of miR-126. Acta biomaterialia 2020, 103, 196-212. [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.H.; Lee, R.P.; Wu, W.T.; Chen, I.H.; Yeh, K.T.; Wang, C.C. Advancing Osteoarthritis Treatment: The Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes and Biomaterial Integration. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Liang, G. Strategies for Engineering Exosomes and Their Applications in Drug Delivery. Journal of biomedical nanotechnology 2021, 17, 2271-2297. [CrossRef]

- Elsharkasy, O.M.; Nordin, J.Z.; Hagey, D.W.; de Jong, O.G.; Schiffelers, R.M.; Andaloussi, S.E.; Vader, P. Extracellular vesicles as drug delivery systems: Why and how? Advanced drug delivery reviews 2020, 159, 332-343. [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A.; Bagherifar, R.; Ansari Dezfouli, E.; Kiaie, S.H.; Jafari, R.; Ramezani, R. Exosomes as bio-inspired nanocarriers for RNA delivery: preparation and applications. Journal of translational medicine 2022, 20, 125. [CrossRef]

- Lener, T.; Gimona, M.; Aigner, L.; Börger, V.; Buzas, E.; Camussi, G.; Chaput, N.; Chatterjee, D.; Court, F.A.; Del Portillo, H.A.; et al. Applying extracellular vesicles based therapeutics in clinical trials - an ISEV position paper. J Extracell Vesicles 2015, 4, 30087. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Thomsen, P. Mesenchymal stem cell–derived small extracellular vesicles and bone regeneration. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology 2021, 128, 18-36. [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Han, B.; Hai, Y.; Sun, D.; Yin, P. Mechanism of Action of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes in the Intervertebral Disc Degeneration Treatment and Bone Repair and Regeneration. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 833840. [CrossRef]

- Wa, Q.; Luo, Y.; Tang, Y.; Song, J.; Zhang, P.; Linghu, X.; Lin, S.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Z.; et al. Mesoporous bioactive glass-enhanced MSC-derived exosomes promote bone regeneration and immunomodulation in vitro and in vivo. J Orthop Translat 2024, 49, 264-282. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fu, L.; Sun, R.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Exosomes (BMSC-ExO) Promote Osteogenic Differentiation In Vitro and Osteogenesis In Vivo by Regulating miR-318/Runt-Related Transcription Factor 2 (RUNX2). Journal of Biomaterials and Tissue Engineering 2022, 12, 1266-1271. [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Cruz, M.; Vázquez-González, W.G.; Molina-Vargas, P.; Faustino-Trejo, A.; Chávez-Rueda, A.K.; Legorreta-Haquet, M.V.; Aguilar-Ruíz, S.R.; Chávez-Sánchez, L. Exosomes as Regulators of Macrophages in Cardiovascular Diseases. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bai, J.; Xiao, B.; Li, C. BMSC-derived exosomes promote osteoporosis alleviation via M2 macrophage polarization. Molecular medicine (Cambridge, Mass.) 2024, 30, 220. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, M.; Rasiah, P.K.; Bajwa, A.; Rajasingh, J.; Gangaraju, R. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Induced Foxp3(+) Tregs Suppress Effector T Cells and Protect against Retinal Ischemic Injury. Cells 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.H.; Zheng, J.Q.; Ding, J.Y.; Wu, Y.F.; Liu, L.; Yu, Z.L.; Chen, G. Exosome-Mediated Immunosuppression in Tumor Microenvironments. Cells 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhou, M. Immune-Cell-Derived Exosomes for Cancer Therapy. Mol Pharm 2022, 19, 3042-3056. [CrossRef]

- Othman, N.; Jamal, R.; Abu, N. Cancer-Derived Exosomes as Effectors of Key Inflammation-Related Players. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2103. [CrossRef]

- Kugeratski, F.G.; Kalluri, R. Exosomes as mediators of immune regulation and immunotherapy in cancer. Febs j 2021, 288, 10-35. [CrossRef]

- Madel, M.B.; Ibáñez, L.; Wakkach, A.; de Vries, T.J.; Teti, A.; Apparailly, F.; Blin-Wakkach, C. Immune Function and Diversity of Osteoclasts in Normal and Pathological Conditions. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1408. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Zhang, S.; Guo, W.Z.; Li, X.K. The Unique Immunomodulatory Properties of MSC-Derived Exosomes in Organ Transplantation. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 659621. [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.M.; Yang, M.F.; Xu, H.M.; Zhu, M.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, J.; Wang, L.S.; Liang, Y.J.; Li, D.F. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-derived Exosomes: Novel Therapeutic Approach for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Stem Cells Int 2023, 2023, 4245704. [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Bian, Q.; Hong, Y.; Shen, Z.; Xu, H.; Rui, K.; Yin, K.; Wang, S. Olfactory Ecto-Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Ameliorate Experimental Colitis via Modulating Th1/Th17 and Treg Cell Responses. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 598322. [CrossRef]

- Shahir, M.; Mahmoud Hashemi, S.; Asadirad, A.; Varahram, M.; Kazempour-Dizaji, M.; Folkerts, G.; Garssen, J.; Adcock, I.; Mortaz, E. Effect of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes on the induction of mouse tolerogenic dendritic cells. Journal of cellular physiology 2020, 235, 7043-7055. [CrossRef]

- Fathollahi, A.; Hashemi, S.M.; Haji Molla Hoseini, M.; Yeganeh, F. In vitro analysis of immunomodulatory effects of mesenchymal stem cell- and tumor cell -derived exosomes on recall antigen-specific responses. International immunopharmacology 2019, 67, 302-310. [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, M.Y.; Jasim, S.A.; Altalbawy, F.M.A.; Bansal, P.; Kaur, H.; Al-Hamdani, M.M.; Deorari, M.; Abosaoda, M.K.; Hamzah, H.F.; B, A.M. A comprehensive insight into the immunomodulatory role of MSCs-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) through modulating pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs). Cell biochemistry and function 2024, 42, e4029. [CrossRef]

- Nikfarjam, S.; Rezaie, J.; Zolbanin, N.M.; Jafari, R. Mesenchymal stem cell derived-exosomes: a modern approach in translational medicine. J Transl Med 2020, 18, 449. [CrossRef]

- Harrell, C.R.; Djonov, V.; Volarevic, A.; Arsenijevic, A.; Volarevic, V. Molecular Mechanisms Responsible for the Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes in the Treatment of Lung Fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Ti, D.; Hao, H.; Fu, X.; Han, W. Mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomal microRNAs contribute to wound inflammation. Sci China Life Sci 2016, 59, 1305-1312. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Wang, L.; Gao, Z.; Chen, G.; Zhang, C. Bone marrow stromal/stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles regulate osteoblast activity and differentiation in vitro and promote bone regeneration in vivo. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 21961. [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, R.; Huang, C.C.; Ravindran, S. Hijacking the Cellular Mail: Exosome Mediated Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells Int 2016, 2016, 3808674. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Cao, Z.; Xue, J.; Wang, X.; Hu, T.; Han, B.; Guo, Y. Mechanically strained osteocyte-derived exosomes contained miR-3110-5p and miR-3058-3p and promoted osteoblastic differentiation. Biomed Eng Online 2024, 23, 44. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Lyu, F.J.; Deng, Z.; Zheng, Q.; Ma, Y.; Peng, Y.; Guo, S.; Lei, G.; Lai, Y.; Li, Q. Therapeutic potential of stem cell-derived exosomes for bone tissue regeneration around prostheses. J Orthop Translat 2025, 52, 85-96. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Song, C.; Zhen, G.; Jin, Q.; Li, W.; Liang, X.; Xu, W.; Guo, W.; Yang, Y.; Dong, W.; et al. Exosomes derived from BMSCs in osteogenic differentiation promote type H blood vessel angiogenesis through miR-150-5p mediated metabolic reprogramming of endothelial cells. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS 2024, 81, 344. [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Li, Y.; Ji, Y.; Kang, R.; Zhang, K.; Su, X.; Li, J.; Ji, M.; Wu, T.; Cao, X.; et al. Exosomes derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells induce the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation and regulate the inflammatory state in osteomyelitis in vitro model. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's archives of pharmacology 2025, 398, 1695-1705. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Jiao, T.; Yang, L. Enhancing osteoporosis treatment with engineered mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: mechanisms and advances. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15, 119. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Omar, O.; Vazirisani, F.; Thomsen, P.; Ekström, K. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes have altered microRNA profiles and induce osteogenic differentiation depending on the stage of differentiation. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0193059. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, M.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, M.; Mao, C. Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Derived Exosomes Enhance Cell-Free Bone Regeneration by Altering Their miRNAs Profiles. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2020, 7, 2001334. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sharabi, N.; Mohamed-Ahmed, S.; Shanbhag, S.; Kampleitner, C.; Elnour, R.; Yamada, S.; Rana, N.; Birkeland, E.; Tangl, S.; Gruber, R.; et al. Osteogenic human MSC-derived extracellular vesicles regulate MSC activity and osteogenic differentiation and promote bone regeneration in a rat calvarial defect model. Stem Cell Res Ther 2024, 15, 33. [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Wang, G.; Zhou, F.; Li, G.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Z.; Han, Y.; Chen, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Exosomes from young plasma alleviate osteoporosis through miR-217-5p-regulated osteogenesis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell. Composites Part B: Engineering 2024, 276, 111358. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Su, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, L.; Zhang, L. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells: whether they can become new stars of cell therapy. Stem Cell Res Ther 2024, 15, 367. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, S.; Lu, J.; Chen, X.; Zheng, T.; He, R.; Ye, C.; Xu, J. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in skeletal diseases. Front Mol Biosci 2024, 11, 1268019. [CrossRef]

- Janockova, J.; Slovinska, L.; Harvanova, D.; Spakova, T.; Rosocha, J. New therapeutic approaches of mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes. J Biomed Sci 2021, 28, 39. [CrossRef]

- Lian, M.; Qiao, Z.; Qiao, S.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J.; Xu, R.; Zhu, N.; Tang, T.; Huang, Z.; Jiang, W.; et al. Nerve Growth Factor-Preconditioned Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosome-Functionalized 3D-Printed Hierarchical Porous Scaffolds with Neuro-Promotive Properties for Enhancing Innervated Bone Regeneration. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 7504-7520. [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Qiao, X.; Liu, Q.; Song, S.; Zhu, K.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, X.; Jia, C.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; et al. Systemic proteomics and miRNA profile analysis of exosomes derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 2022, 13, 449. [CrossRef]

- González-Cubero, E.; González-Fernández, M.L.; Gutiérrez-Velasco, L.; Navarro-Ramírez, E.; Villar-Suárez, V. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Journal of Anatomy 2021, 238, 1203-1217. [CrossRef]

- Currey, J.D.; Dean, M.N.; Shahar, R. Revisiting the links between bone remodelling and osteocytes: insights from across phyla. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 2017, 92, 1702-1719. [CrossRef]

- Altıntaş, Ö.; Saylan, Y. Exploring the Versatility of Exosomes: A Review on Isolation, Characterization, Detection Methods, and Diverse Applications. Anal Chem 2023, 95, 16029-16048. [CrossRef]

- Hade, M.D.; Suire, C.N.; Suo, Z. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes: Applications in Regenerative Medicine. Cells 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Sources and Differentiation Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs). Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can be isolated from various tissue sources, including bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, placenta, dental pulp, and peripheral blood. These multipotent cells possess the ability to differentiate into a range of cell types such as osteocytes, chondrocytes, adipocytes, myocytes, neuronal cells, and tenocytes. Additionally, MSCs play roles in regenerating tissues of the lungs, kidneys, liver, and vasculature, highlighting their broad therapeutic potential in regenerative medicine.

Figure 1.

Sources and Differentiation Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs). Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can be isolated from various tissue sources, including bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, placenta, dental pulp, and peripheral blood. These multipotent cells possess the ability to differentiate into a range of cell types such as osteocytes, chondrocytes, adipocytes, myocytes, neuronal cells, and tenocytes. Additionally, MSCs play roles in regenerating tissues of the lungs, kidneys, liver, and vasculature, highlighting their broad therapeutic potential in regenerative medicine.

Figure 2.

Immunomodulatory effects of MSC-derived exosomes. The exosomes modulate T cell responses by suppressing the proliferation of inflammatory T cells (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-17 producers) while promoting regulatory T cell expansion and IL-10 expression, enhancing immune tolerance. They also inhibit M1 macrophage polarization, dendritic cell antigen presentation, and T cell activation capacity. Key anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β1) and pathways (↑NRF2, ↓NF-κB/NLBP3) contribute to a regenerative microenvironment, countering pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-17).

Figure 2.

Immunomodulatory effects of MSC-derived exosomes. The exosomes modulate T cell responses by suppressing the proliferation of inflammatory T cells (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-17 producers) while promoting regulatory T cell expansion and IL-10 expression, enhancing immune tolerance. They also inhibit M1 macrophage polarization, dendritic cell antigen presentation, and T cell activation capacity. Key anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β1) and pathways (↑NRF2, ↓NF-κB/NLBP3) contribute to a regenerative microenvironment, countering pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-17).

Figure 3.

Therapeutic Potential of MSC-Derived Exosomes for Bone Diseases. This schematic diagram illustrates the multifaceted therapeutic roles of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes in addressing various bone disorders. MSCs secrete exosomes, which can be directly administered or integrated into biomaterial scaffolds. In osteoporosis, exosomes enhance bone density and reduce fracture risk by stimulating osteoblast activity and inhibiting osteoclastogenesis. In rheumatoid arthritis, they alleviate joint damage and modulate cytokine production by suppressing inflammatory pathways. In osteomyelitis, exosomes promote tissue regeneration and modulate immune responses, possibly by delivering antimicrobial peptides and regulating inflammatory cell activity, aiding in the healing of infected bone tissues.

Figure 3.

Therapeutic Potential of MSC-Derived Exosomes for Bone Diseases. This schematic diagram illustrates the multifaceted therapeutic roles of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes in addressing various bone disorders. MSCs secrete exosomes, which can be directly administered or integrated into biomaterial scaffolds. In osteoporosis, exosomes enhance bone density and reduce fracture risk by stimulating osteoblast activity and inhibiting osteoclastogenesis. In rheumatoid arthritis, they alleviate joint damage and modulate cytokine production by suppressing inflammatory pathways. In osteomyelitis, exosomes promote tissue regeneration and modulate immune responses, possibly by delivering antimicrobial peptides and regulating inflammatory cell activity, aiding in the healing of infected bone tissues.

Table 1.

Exosomal Cargo and Their Roles in Bone Regeneration.

Table 1.

Exosomal Cargo and Their Roles in Bone Regeneration.

| Bioactive Cargo |

Function |

Citation |

| miR-3110-5p |

Promote osteoblast differentiation |

[76] |

| miR-3058-3p |

| miR-21 |

Enhance osteoblast proliferation and differentiation by targeting the TGF-β signaling pathway |

[39] |

| miR-29a |

Promotes osteoblast differentiation and extracellular matrix mineralization |

[39] |

| miR-20a |

Contributes to osteogenic differentiation by targeting BAMBI |

[18] |

| miR-540-3p |

Modulates dendritic cells and T cells via the CD74/NF-κB pathway, enhancing immune tolerance and reducing graft rejection |

[16] |

| miR-3940-5p |

Can inhibit tumour proliferation and migration by targeting oncogenic pathways |

[17] |

| miR-22-3p |

| miR-16-5p |

| miR-21 |

Involved in regulating inflammatory signalling and cell survival |

[72,73] |

| miR-146a |

| miR-181 |

| Pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IFN-γ) |

Suppressed by MSC-derived exosomes |

[16] |

| Anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β1) |

Promoted by MSC-derived exosomes, contributing to immune tolerance |

[16] |

| Growth factors (VEGF, HGF) |

Support tissue repair and angiogenesis |

[71] |

Table 2.

Preclinical Studies of MSC-Derived Exosomes in Bone Regeneration Models.

Table 2.

Preclinical Studies of MSC-Derived Exosomes in Bone Regeneration Models.

| Disease Model |

Key Findings |

Citations |

| Osteoporosis |

Promoted osteointegration of porous titanium alloy by enhancing osteogenesis |

[18] |

| Improve bone mass and formation |

[39] |

| Enhance bone density and reduce fracture risk likely through stimulation of osteoblast activity and inhibition of osteoclastogenesis |

[42] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) |

Alleviate joint damage and improve function |

[21] |

Table 3.

Immunomodulatory Effects of MSC-Derived Exosomes on Immune Cells.

Table 3.

Immunomodulatory Effects of MSC-Derived Exosomes on Immune Cells.

| Immune Cell Type |

Observed Immunomodulatory Effects |

Citation |

| Macrophages |

Induce either pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory phenotypes depending on the microenvironment |

[57] |

| Promote M2 macrophage phenotype in neuroinflammatory models |

[15] |

| Macrophages (DPSC-Exo specific) |

Facilitate the conversion of macrophages from a pro-inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory phenotype, thereby suppressing periodontal inflammation |

[28] |

| T cells |

Suppress proliferation of inflammatory T cells (producing interferon-γ and IL-17) |

[14] |

| T cells |

Enhance IL-10 expression |

[65] |

| T cells |

Encourage regulatory T cell expansion and immune tolerance |

[66] |

| Dendritic cells |

Alter antigen presentation and T cell activation capacity |

[62] |

| Dendritic cells |

miR-540-3p modulates dendritic cells via CD74/NF-κB pathway |

[16] |

Table 4.

Effect of MSC-Derived Exosomes in Bone Regeneration.

Table 4.

Effect of MSC-Derived Exosomes in Bone Regeneration.

| Effect |

Specifications |

Citation |

| Promotion of Osteogenesis |

Enhance osteoblast proliferation and differentiation |

Deliver specific microRNAs (miRNAs) that promote osteogenic markers and inhibit negative regulators of bone formation. For instance, miR-21 enhances osteoblast proliferation and differentiation by targeting the TGF-β signaling pathway. miR-29a promotes osteoblast differentiation and extracellular matrix mineralization. |

[37] |

| [38] |

| [39] |

| Influence osteoblast maturation into osteocytes |

Exosomes deliver specific microRNAs (miRNAs) that influence the maturation of osteoblasts into osteocytes. |

[37] |

| [38] |

| Stimulation of Angiogenesis |

Promote formation of new blood vessels |

Crucial for supplying nutrients and oxygen to regenerating bone tissue and developing osteocytes within that tissue |

[40] |

| In Vivo Bone Regeneration |

Accelerate bone healing, increase bone volume, and improve mechanical strength |

Animal models of bone defects have demonstrated this in response to local or systemic administration. Crucial for restoring structural integrity and long-term functionality of bone tissue |

[18] |

| [42] |

| Modulation of Inflammatory Response |

Create a favorable environment for tissue regeneration |

MSC-derived exosomes can modulate the inflammatory response in the bone defect site |

[58] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).