1. Introduction

Understanding how attractions and tourist motivations interact is crucial for developing effective marketing strategies and enhancing the overall tourist experience. At the heart of this inquiry, one critical question shall always be asked and addressed: are tourists inherently drawn to the attractions themselves, or do their choices reflect deeper personal motivations? This necessity arises from the recognition that as the tourism landscape evolves, so too do the expectations and motivations of tourists, making it imperative for destinations to adapt accordingly. While iconic landmarks may possess a magnetic appeal, the underlying drivers of tourist behaviour often reveal a tapestry of needs and aspirations that extend beyond the mere presence of an attraction (Li et al., 2015). This exploration gains further significance through Leiper’s (1990) tourist attraction system model, which has sparked vibrant discussions among scholars and industry professionals regarding the complex interplay between attractions, tourists, and their environments.

Leiper’s (1990) model emphasises that attractions are not isolated entities; instead, they exist within a broader system that includes tourists’ motivations, the socio-cultural context, and the physical environment. This interconnectedness prompts us to consider how evolving tourist motivations shape the tourism landscape and influence the effectiveness of marketing strategies (Dunn-Ross & Iso-Ahola, 1991). McKercher (2017) further emphasises that destination strategies must adapt as tourists’ motivations shift to engage and attract visitors effectively. This adaptability is crucial in a globalised tourism market where cultural exchanges and technological advancements continuously reshape tourist expectations. However, a comprehensive analysis synthesising these dynamics across different global contexts remains a gap, particularly in understanding how various attractions resonate with diverse motivations (Lew, 1987).

The motivations underlying travel are multifaceted and shaped by various factors, including social, psychological, and cultural influences. Crompton (1979) identified several motivational dimensions, including push and pull factors, which motivate individuals to travel and draw them to destinations. This duality is essential for understanding the complex dynamics of tourists’ attraction choices. For example, a tourist may be motivated to travel due to a desire for adventure (a push factor), but may also be drawn to a specific destination because of its renowned natural beauty (a pull factor). This interplay emphasises the necessity for a detailed understanding of tourist motivations that goes beyond simplistic classifications. To contextualise this study, the authors examine four diverse destinations: South Africa, Hong Kong, Australia, and England. These locations were selected for their representation of both built and natural attractions, as well as their ability to cater to diverse tourist motivations, as evidenced by recent short- and long-haul market reports (UN Tourism, 2024).

Each destination offers a unique blend of experiences that reflect its cultural heritage and natural beauty, providing a rich ground for analysis. For instance, South Africa’s blend of wildlife and cultural heritage, Hong Kong’s urban vibrancy juxtaposed with natural landscapes, Australia’s diverse ecosystems, and England’s historical landmarks all present distinct attractions that cater to different tourist motivations. A qualitative case study was employed to explore the interplay between tourist attractions and motivations. It draws upon various theoretical concepts and models supported by existing research in the field. Market reports from the countries’ official websites provide credible insights into their built and non-built attractions, marketing strategies, visitor demographics, and overall recipient profiles (South African Department of Tourism, 2024; Hong Kong Tourism Board, 2024; Tourism Australia, 2024; VisitBritain, 2024).

Additionally, supplementary data from organisations such as UN Tourism and various attraction site offices are integrated to enhance the conceptual framework and arguments related to attractions and travel motives. Thus, understanding the interplay between attractions and tourist motivations is essential for shaping effective marketing strategies that enhance the broader discourse about tourism and its triple-bottom-line effects. By comprehensively examining these themes, this study aims not only to bridge the gaps in the current literature but also to synthesise findings to create a conceptual framework that integrates insights on how attractions and personal motivations influence tourist behaviour in the selected case study regions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Attractions and Activities

Attractions serve as a focal point for visitors, acting as the “lifeblood” of destinations because they significantly influence the overall visitor experience (Pearce, 1991; Swarbrooke, 2002). Jafari (1974) conceptualised attractions as products, a notion supported by the UNWTO (2004), which defines destinations as physical locations comprising various products. According to the UNWTO (2008), attractions encompass anything visitors use. Mckercher (2016) expanded on this definition, noting that family members or business entities can qualify as attractions depending on the purpose of the visit, such as visiting friends and relatives or conducting business. He argued that non-locational activities, such as shopping, sightseeing, and dining, should also be considered attractions. Ultimately, attractions play a crucial role in enhancing visitors’ enjoyment and overall experience at a destination. Attractions can be categorised into built and natural forms, each appealing to distinct tourist market segments (Pearce, 1991).

Built attractions, such as museums, theme parks, and historical sites, often fulfil educational and entertainment needs. In contrast, natural attractions like national parks and beaches typically cater to desires for relaxation and adventure (Frochot & Morrison, 2000). This distinction is vital for understanding how different types of attractions influence tourists’ decision-making processes. For example, built attractions may draw those seeking cultural enrichment, while natural attractions appeal to those yearning for escapism and a connection with the natural world. Recognising these differences enables the development of more targeted marketing strategies and tourism products. However, some argue the presence or absence of attractions does not always significantly influence tourists’ decision-making, as many may passively engage with available resources (Timothy, 1997; McKercher & Wong, 2021).

Scholars suggest that the varying needs and desires of tourists at these attractions significantly influence their choices. Even when destinations offer various infrastructures, such as transportation and accommodations, not all tourists express interest in utilising them (Mill & Morrison, 1985; Leiper, 1990; Mckercher, 2016). Tourists may share broad needs and wants, yet the activities that satisfy these needs can differ widely, indicating that a broader range of activities can meet diverse tourist preferences (Leiper, 1990; Tangeland, 2011). Thus, if tourists seek to fulfil their general needs, the specific attributes of destinations, including built attractions, may become secondary, particularly in multi-product urban destinations with abundant options (Crompton, 1979; McKercher & Wong, 2021; Framke, 2002).

Goeldner (2000) further emphasises that specific and built attractions should be bundled with other tourism resources such as sightseeing, shopping, entertainment, culture, and recreation to maximise competitiveness. When needs are less specific, any destination or attraction can potentially satisfy tourists (Botti et al., 2008). However, if travel is driven by a particular need, as seen in the context of leisure, tourists are likely to be drawn to attractions (Hartel et al., 2006). This understanding implies that specifically built attractions can attract tourists motivated by specific needs, while their importance diminishes when needs are broad and interchangeable (Mckercher, 2017). Thus, built attractions can cater to specific, non-substitutable needs while serving merely as an end for those motivated by broader, substitutable attractions. Curiosity and the desire for new experiences often motivate individuals to choose specific attractions (Podoshen, 2013; Sharpley & Stone, 2009).

Attractions within a destination act as vehicles for fulfilling tourists’ needs and wants. Lundberg (1976) noted that what travellers label as motivations may merely reflect deeper, unarticulated needs. These intrinsic desires can sometimes remain unrecognised, with attractions providing a medium for satisfying them. In some cases, especially among youth travellers, a quest for risk and adventure may drive decisions, as young adults often seek experimentation and exploration (Gibson & Yiannakis, 2002). The millennial generation is inclined to pursue memorable and authentic experiences, seeking to immerse themselves in local cultures and often prioritising safety, health, and well-being (Veiga et al., 2017). In the contemporary context, experience transcends mere service delivery; it focuses on creating memorable and unique events where the buyer is regarded as a guest and the seller as a provider (Pine & Gilmore, 1998). As a result, experiential tourism continues to thrive, reflecting this shift towards valuing distinct and meaningful interactions.

2.2. Tourist Motivation and Activities

Tourist motivation is crucial in understanding travellers’ needs, desires, and satisfaction (Chang et al., 2014). It drives tourists’ behaviours, influencing their decisions to visit specific destinations or attractions (Suhartanto et al., 2018). Moutinho (2000) characterises motivation as a condition that compels individuals toward activities likely to yield personal satisfaction. Tangeland (2011) posits that motivations can range from specific to general; the more generalised the need, the wider the array of activities available to fulfil it. Leiper (1990) supports this notion, noting that while different individuals may share a common broad need for relaxation, they often pursue this need through various activities, suggesting that each person harbours more specific sub-needs. In exploring these activities, authors investigate the fundamental reasons that prompt tourists to select attractions. Tourists typically possess multiple motivations for travel, even within a single trip (Bowen & Clarke, 2009).

Meng & Uysal (2008) emphasise that a deeper understanding of travel motivations can enhance market segmentation, enabling tourism marketers to allocate limited resources more effectively. Consequently, prominent figures in the field and related disciplines have developed numerous theories and models to address the complex nature of tourism motivation. These frameworks not only help dissect the layers of tourist motivations but also provide valuable insights into how various factors, such as cultural influences, personal experiences, and socio-economic conditions, influence individuals’ travel decisions. By identifying and categorising these motivations, tourism professionals can tailor their offerings to meet travellers’ diverse expectations, ultimately improving satisfaction and fostering long-term engagement with destinations.

2.3. Push-Pull Motivation Theory

After Tolman’s (1959) conceptualisation of push-pull motivation, Dann (1977) brought the idea of push-pull tourist motivation into tourism research. Since then, the theory has emerged as one of the most widely used frameworks for studying tourist behaviour (Wong et al., 2017; Michael et al., 2017). Empirical research on tourist motivation has predominantly employed the push-pull motivation theory to examine the demand and supply sides within various tourism contexts (Kassean & Gassita, 2013). The push factors in this theory are associated with the intrinsic motivations of tourists who choose to visit specific destinations. These factors encompass a range of desires, including the need for rest, health, relaxation, escape, prestige, social interaction, and discovery (Prebesen et al., 2013; Yoon & Uysal, 2005). Dann (1981) elaborated on this by introducing concepts such as anomie, which represents an interest in escaping the monotony of everyday life, and ego-enhancement, which denotes the need for acknowledgement related to travel experiences.

Iso-Ahola (1982) proposed two primary motivators: escaping, which refers to the traveller’s interest in leaving their usual residence and seeking, which pertains to pursuing intrinsic rewards through travel in new settings. His escape or pursuit theory introduces a four-quadrant framework that encompasses both individual benefits and social interactions. These motivations for escape and seeking are closely linked to the push-pull factors defined by previous scholars (Dann,1977; Crompton, 1979). Nevertheless, there is a degree of scepticism regarding the universal applicability of this approach across diverse contexts and its ability to fully encapsulate the complexities of tourist motivation (Jamal & Lee, 2003; Dann, 1981; Crompton & McKay, 1997). Critics argue that tourists do not always act in accordance with conventional assumptions (Pearce, 1991) and that their desires may extend beyond mere need satisfaction, which the push-pull theory is based on (MacCannell, 1973; Cohen, 1972).

Furthermore, Mckercher (2016) noted that the value of each attraction is contingent upon the specific needs of the tourists, highlighting the central role of tourists in evaluating whether their motivations will be met when selecting attractions, destinations, and other tourism services. Conversely, pull motivation is viewed as external influences connected to the appeal of attractions, destinations, or products that can affect tourists’ visiting or purchasing behaviours (Michael et al., 2017). These factors encompass tangible and intangible elements, including safety, affordability, cultural activities, entertainment options, uniqueness, staff friendliness, and a perceived contrast to their home environment. Once tourists have decided on a particular product or destination, pull factors can effectively satisfy their push motivations. Tourists often consider multiple pull factors if they align with their underlying push motivations. Moreover, when attractions or destinations are managed effectively, they can create an environment that fosters push-pull motivation, enhancing the overall appeal for potential tourists (Dean & Suhartanto, 2019; Yoon & Uysal, 2005; Suni & Pesonen, 2019).

2.4. Travel Personality Model and Travel Career Ladder

The Travel Personality Model, introduced by Plog (1974), is grounded in the psychological traits of individuals. It posits that people are placed along a range of travel personalities, ranging from “allocentric” to “psychocentric.” This spectrum includes categories such as “near allocentric,” “mid-centric,” and “near psychocentric.” The extremes, allocentric and psychocentric, are relatively uncommon, with most individuals situated somewhere in between these two poles. This model highlights the diversity of travellers’ motivations and preferences, reflecting a rich tapestry of personality traits influencing travel choices.

The travel career ladder has been introduced based on the motivational theories of Maslow (1964) and Pearce (1991). Pearce (1991) categorised tourist motivations into five ascending levels: relaxation, stimulation, relationships, self-esteem, and ultimately, self-actualisation at the peak. This framework acknowledges that varying motivations emerge from different travel experiences shaped by an individual’s life journey. As travellers embark on their journeys, they often start with simpler goals, such as seeking relaxation, and progressively aspire to higher objectives as their experiences deepen, culminating in the quest for self-actualisation. In response to critiques regarding the original “ladder” metaphor, Ryan (1998) made slight modifications to introduce the travel career pattern, which focuses on the patterns of motivation rather than a strict hierarchy. This revised model highlights the dynamic nature of travel motivations, emphasising that they evolve more nuanced than a linear progression might suggest (Pearce & Lee, 2005).

2.5. Strangeness Versus Familiarity

Cohen (1972) approached tourism sociologically, situating the model within the social context. He contended that tourism is a social event, emphasising the need to analyse tourists in relation to business entities, such as tour operators, and the destinations they visit. This analysis introduces the concept of strangeness and familiarity, which he developed by deconstructing Boorstin’s (1964) all-encompassing portrayal of “tourists” into more defined and empirically distinguishable categories: “organised” and “individual” mass tourists, “explorer,” and “drifter,” as identified by Chen and colleagues (2011).

Cohen (1972) argued that tourists are driven by an interest in experiencing the strangeness and familiarity of their destinations. This interplay results in a spectrum that captures the different levels of tourists’ unfamiliarity with the attractions they visit, alongside their familiarity with the surrounding environment. Some tourists may feel entirely out of their depth in a new locale, while others may find comfort in familiar cultural elements. This continuum allows for a nuanced classification of tourists, highlighting the diverse nature of their experiences and the various motivations that drive them to explore. Understanding these dynamics will enable us to recognise how multiple factors influence a tourist’s experience. It highlights that tourism is not a universal experience; it varies significantly from person to person. Some tourists may seek adventure and novelty, while others might look for comfort in familiar surroundings.

3. Methodology

The research methodology for this secondary literature review is structured to provide a comprehensive analysis of existing scholarship on tourist attractions and personal motivations, aiming to develop a conceptual framework that elucidates the evolving motivations of tourists across various continents, with a specific focus on case studies from South Africa, Hong Kong, Australia, and England.

3.1. Literature Search Strategy

A rigorous literature search was undertaken using leading academic databases, such as Scopus and Web of Science, which are renowned for their comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed journals in the social sciences. These platforms are particularly valuable for research in tourism, leisure, and hospitality, ensuring a wide-ranging and authoritative foundation for our study (Dann et al., 1988). The search employed a carefully crafted combination of keywords and phrases such as “motivation”, “tourist motivations,” “motivation theories”, “attraction”, “tourist attractions,” “cross-continental tourism,” and family words. This strategic approach aims to capture a comprehensive array of relevant studies, ensuring a robust foundation for the analysis.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Upon completing the initial searches, a systematic screening process was employed to select studies that align with the established inclusion criteria. This process focuses on peer-reviewed articles, book chapters, and relevant conference papers published in reputable sources. Non-academic sources, articles lacking empirical evidence, and studies that do not specifically address the comparative aspects of attractions and motivations were excluded to maintain the integrity and relevance of the literature reviewed. Accordingly, the authors included 65 articles in the analysis.

3.3. Thematic Categorisation and Analysis

The selected literature was meticulously organised into thematic categories based on prevalent themes and topics (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008; Braun & Clarke, 2006). These categories include theoretical frameworks on tourist motivations, empirical studies exploring the relationship between attractions and motivations, and comparative analyses across the four case study regions. For instance, the literature on South Africa emphasises natural attractions and cultural heritage, while studies from Hong Kong focus on urban attractions and shopping motivations. In contrast, Australia’s literature explores adventure tourism and ecological motivations, whereas England highlights historical sites and cultural experiences.

Following the organisation of the literature, a thematic analysis was conducted to identify key patterns, trends, and discrepancies within the existing scholarship. This analysis synthesises findings, culminating in the development of a conceptual framework that visually represents the intricate relationship between attractions and personal motivations in tourism. The framework considers how specific factors, such as cultural, social, and economic influences, interact to shape tourist behaviours in South Africa, Hong Kong, Australia, and England.

3.4. Synthesis and Reporting

The final stage of the methodology involves creating a narrative summary that synthesises the insights derived from the thematic analysis. This summary highlights major themes, identifies gaps in the current literature, and suggests potential areas for future research. Additionally, visual representation is developed to illustrate the newly constructed conceptual framework, thereby enhancing the accessibility and comprehensibility of the findings for the academic community and practitioners in the field of tourism studies. This comprehensive methodology aims to significantly contribute to the understanding of tourist motivations, offering a refined perspective that integrates attractions and personal drivers within a cross-continental context, enriched by specific case studies from South Africa, Hong Kong, Australia, and England.

3.5. Quality Appraisal

To ensure the reliability and validity of the selected studies, a quality appraisal was conducted. This appraisal assesses the methodological rigour of the included studies, considering factors such as relevance of search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the appropriateness of the analytical techniques employed. Studies are rated based on established appraisal criteria, ensuring that only high-quality literature contributes to the final synthesis (Moher et al., 2009; Okoli & Schabram, 2015).

3.6. Purpose and Contribution

The purpose of this research is to deepen the understanding of tourist motivations by integrating insights from diverse geographical contexts. By focusing on case studies from South Africa, Hong Kong, Australia, and England, the study aims to highlight the unique attractions and motivations pertinent to each region, contributing to a broader understanding of global tourism dynamics. The findings are expected to offer valuable insights for academics, policymakers, and practitioners in tourism management, providing a foundation for future research and practical applications in the field with a conceptual framework (Wang et al., 2021).

4. Results

4.1. South Africa’s Tourism Attractions, Activities, and Market Report

South Africa is renowned for its diverse and captivating attractions, significantly contributing to its tourism appeal. The country offers a blend of natural and built environments, including famous sites such as Kruger National Park, Table Mountain, the Cape Winelands, and the vibrant cities of Cape Town and Johannesburg. Each site caters to tourist motivations, from adventure and exploration to relaxation and cultural enrichment (South African Department of Tourism, 2024). Table Mountain, celebrated for its stunning views and unique biodiversity, attracts outdoor lovers and thrill-seekers eager to explore its picturesque trails. This situation aligns with the travel career ladder, where visitors move from general leisure interests to more specific natural pursuits (Cohen, 1972). Kruger National Park is among the largest game reserves in Africa, providing opportunities for wildlife safaris that fulfil the desire for adventure and discovery, a key aspect of the travel personality model (Pearce, 1991).

Additionally, the Cape Winelands offer a range of cultural and gastronomic experiences, drawing visitors interested in wine tasting and culinary exploration (South African Department of Tourism, 2024). Cultural attractions, such as the Apartheid Museum and Robben Island, provide profound insights into the nation’s history and heritage, appealing to travellers motivated by education and cultural understanding (South African Department of Tourism, 2024). This position reflects the hierarchy of travel motivation, where tourists seek deeper engagement with cultural narratives as their basic needs are met (Maslow, 1943).

Recent reports indicate that South Africa continues to attract a diverse range of international tourists, with significant contributions from markets such as the UK, the US, and Germany. These long-haul travellers often seek unique experiences that combine adventure, culture, and natural beauty, typically averaging a length of stay of 10 to 14 nights (South African Department of Tourism, 2024). This trend illustrates the applicability of the distance decay theory, as proximity influences the volume and behaviour of visitors (Bull, 1991). Tourists from neighbouring countries, including Namibia and Botswana, often make shorter trips focused on leisure and adventure activities, such as wildlife viewing and outdoor sports. In contrast, long-haul tourists from North America and Europe are motivated by combining vacationing and cultural experiences, indicating a deeper engagement with South Africa’s rich heritage (Ho & McKercher, 2014).

The South African Department of Tourism utilises a variety of marketing strategies tailored to these diverse segments. These include digital marketing campaigns, travel agency partnerships, and participation in international tourism fairs (South African Department of Tourism, 2024). Such strategies aim to highlight the unique attractions of South Africa, appealing to tourists’ motivations for adventure, cultural enrichment, and relaxation (Wong et al., 2016). Additionally, India has emerged as a growing market for South African tourism, with Indian travellers increasingly drawn to the country’s natural beauty and cultural experiences. This trend aligns with the travel personality model, suggesting that as travellers gain experience, their motivations evolve, prompting them to seek more enriching and diverse travel experiences (Pearce, 1991). Overall, South Africa’s attractions and marketing strategies effectively cater to tourist motivations, aligning with the hierarchy of travel motivation interpretations. By offering a mix of adventure, culture, and relaxation, the country enhances the overall visitor experience, encouraging repeat visits and deeper engagement with its diverse offerings.

4.2. Australia’s Tourism Attractions, Activities, and Market Report

To meet the varied demands of tourists, Australia has developed a comprehensive array of tourism products, encompassing both natural and built attractions, which have successfully drawn millions of visitors worldwide. Among these, the Sydney Opera House is a hallmark of twentieth-century engineering. It symbolises Australia and the country’s most frequented site, serving as the busiest performing arts centre, welcoming over eight million visitors annually (Patricia & Susan, 2005). Tourism Australia (2024) states that, although the Opera House is a built attraction, it offers visitors opportunities to participate in various performances, enriching their cultural experience. Moreover, it can be seamlessly integrated with other attractions, creating a holistic visit that maximises visitor satisfaction across a spectrum of needs. In addition to built attractions, Australia boasts the Great Barrier Reef, one of the largest coral reef ecosystems globally, renowned for its globally significant biodiversity (Gaładyk & Podhorodecka, 2021) and diverse underwater habitats, which contribute to its universally recognised scenic beauty (Hughes et al., 2003). Tourists are drawn to the reef for experiences such as scuba diving, snorkelling, and exploring through glass-bottomed boats and seaplanes. Furthermore, Australia offers a variety of other natural and cultural attractions, including Bondi Beach, Uluru (formerly Ayers Rock), and a range of wine and culinary experiences.

With its attractions and a focus on contemporary experiential marketing, Australian tourism has witnessed significant growth in international arrivals. By 2024, the country welcomed 20.2 million international visitors, contributing AUD 47.8 billion, with AUD 26.4 billion coming from leisure spending and AUD 4.4 billion from business visitors. This data highlights the sector’s economic impact on the country, demonstrating its importance as a key sector for revenue generation (Tourism Australia, 2024). Unlike many other nations, Australia’s inbound tourism primarily consists of long-haul travellers. However, distance decay theory posits that tourism demand decreases as the distance travelled increases or when time and monetary costs rise (Bull, 1991). According to the same report, Australia attracts the most tourists from China, New Zealand, the US, the UK, Japan, and Singapore, with long-haul and short-haul visitors primarily motivated by the country’s natural beauty (Tourism Australia, 2024).

In a contemporary context, natural attractions are recognised for their positive effects on well-being, including restorative benefits, increased agreeableness, stress reduction, empathy, and pro-social behaviour (White et al., 2013). Thus, Australia’s tourism marketing emphasises experiences that promote cognitive enrichment, exploration, and overall well-being, particularly through visits to its natural attractions. For instance, the Tourism Australia Report (2024) indicates that 71% of tourists visit Australia for its natural wonders, with a strong intention to return for repeat visits. This result suggests that many of these visitors are experienced travellers, as explained in the travel career pattern model, and are motivated by goals of self-development and education. At the same time, many tourists continue to seek out iconic cultural resources, such as the Sydney Opera House and urban botanical gardens. This dual attraction model effectively draws both short- and long-haul tourists. Australia’s diverse tourism resources are well-suited to accommodate tourists with a range of needs, as reflected in their marketing strategies and promotional efforts. Understanding these dynamics enables Australia to tailor its offerings to meet diverse motivations, aligning with the hierarchy of travel motivation interpretations and the travel personality model, thereby enhancing the overall visitor experience.

4.3. Hong Kong’s Tourism Attractions, Activities, and Market Report

Hong Kong is recognised globally as a vibrant international city renowned for luxury shopping. However, it also boasts a unique cultural blend and dynamic lifestyle, featuring forested mountains, traditional fishing villages, soft sandy beaches, and islands with breathtaking skylines (McKercher et al., 2004). The Hong Kong Tourism Board (2024) has further enriched the visitor experience by enhancing its year-round program of major events, adding vibrancy and colour to the city, thereby elevating the overall travel experience for tourists. Key attractions and activities in Hong Kong include Victoria Peak, a prime spot for sightseeing, cable car rides, and photography; Hong Kong Disneyland, where visitors can enjoy amusement rides, shows, dining, shopping, and sightseeing; Victoria Harbour, famous for its Symphony of Lights, which offers excellent photo opportunities and shopping; Old Town Central, known for its art installations and picturesque views; Man Mo Temple, a site for meditation and sightseeing; and Ocean Park, which combines dining, rides, shows, and sightseeing (Hong Kong Tourism Board, 2024).

The Hong Kong Tourism Board provides visitor profile reports detailing the various tourist source markets. Unlike Australia’s predominantly long-haul tourism, the distance decay theory is particularly relevant in Hong Kong, suggesting that the distance tourists travel significantly influences visitor volume, demographics, behaviour, and activities (Ho & Mckercher, 2014; Hong Kong Tourism Board, 2024). According to this theory, China and Taiwan emerged as the primary source markets for Hong Kong. Chinese tourists are primarily motivated by vacations, visits to friends and relatives, conventions, studies, and familiarisation tours. Taiwanese visitors are similarly motivated, with vacation travel predominant, though business tourism also features prominently, distinguishing them from the predominantly short-haul Chinese market (Hong Kong Tourism Board, 2024; Ho & McKercher, 2014). Most tourists visiting Hong Kong fall within the familiarity aspect of Cohen’s (1972) Strangeness and Familiarity Continuum, seeking experiences that resonate with their cultural backgrounds. Hong Kong employs conventional tourism marketing strategies, such as digital consumer promotions and public relations campaigns, which contrast with the strategies used in Australia. Long-haul US and UK tourists are primarily driven by vacation, business, and visiting friends and relatives’ motivations, respectively (Hong Kong Tourism Board, 2024).

The Hong Kong Tourism Board implements various marketing initiatives to attract these visitors, including destination alliance workshops, educational seminars, conventions, and direct consumer advertising (Wong et al., 2016; Hong Kong Tourism Board, 2024). Additionally, India has emerged as a growing market, with Indian tourists motivated primarily by vacations, followed by business travel. This dynamic landscape of attractions and tourist motivations in Hong Kong can be analysed through various frameworks, such as the travel personality model and the travel career ladder. These models illustrate how individual preferences and experiences evolve, influencing tourists’ choices and satisfaction. The hierarchy of travel motivation emphasises that travellers fulfil basic needs and seek higher-level experiences, which Hong Kong effectively provides through its blend of cultural, natural, and entertainment attractions.

4.4. England’s Tourism Attractions, Activities, and Market Report

The VisitBritain report (2024) highlights the vital role of tourism in England’s economy and the importance of understanding tourist motivations. Attractions experienced an 11% increase in visitors from 2022 to 2023, although this figure remains 28% lower than in 2019. Art galleries and museums led the gains, with a 20% increase, while religious sites recorded a 19% increase. This growth was largely fueled by an 80% surge in international visitors and an increase in school trips. The Museum emerged as the most popular attraction, drawing 5.8 million visitors (a 42% increase from 2022), while the Tower of London led paid attractions with 2.8 million visitors (up 38% from 2021). England’s attractions encompass a diverse range of built environments, including renowned buildings, historic castles, museums, art galleries, gardens, parks, theatres, and shopping venues. Approximately half of the inbound tourists visit for leisure, with the top three source markets being the United States, France, and Germany, particularly among travellers aged 25 to 34 (VisitBritain, 2024). This demographic insight aligns with the Travel Career Model, suggesting that many visitors to London are relatively inexperienced travellers drawn to these built attractions for relaxation and escapism. In contrast, rural attractions appeal to more experienced and familiar travellers, often motivated by the desire to visit friends and relatives.

As noted earlier, the majority of inbound tourists to England come from the United States, France, and Germany. However, Australia leads the long-haul market, followed by China, with average lengths of stay of 9.6 and 8.3 nights, respectively (VisitBritain, 2024). Australians often have a strong emotional connection to England, viewing it through a lens of nostalgia tied to familial roots. This familiarity means that Australian tourists are typically not strangers to the culture and attractions of the region. In the same report, Norway and France emerged as the primary short-haul markets, with average stays of 4 to 7 nights. Norwegian tourists primarily visit for dining and shopping experiences, while French visitors are motivated by shopping, sightseeing, and leisure pursuits. Similar to the trends seen in Hong Kong, India is identified as an emerging market for travel to England (VisitBritain, 2024). These dynamics can be analysed through the travel personality model and the travel career ladder frameworks, which illustrate how individual preferences and experiences develop over time, influencing travel choices and satisfaction. The hierarchy of travel motivation further emphasises that as travellers meet their basic needs, they are inclined to seek more enriching experiences, a trend that England’s diverse attractions effectively cater to, enhancing the overall visitor experience.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theory, Criticism, and Application

In 1979, Leiper developed a tourism system model to understand tourist flow and inform studies on tourist behaviour, emphasising that tourist motivation is the primary factor driving tourism flows rather than simply the existence of attractions. This view of tourist motivation poses a challenge to the widely known push-pull theory; Dann’s (1977, 1981) work considers visiting attractions as part of the overall experience. Given the former, Pearce (1991) and Ryan (1998) have become proponents of the work of Leiper (1979), where tourism motivation is a critical part of the system, as tourists travel and visit attractions to satisfy their motivational needs through experiences and flow. Similarly, the travel career pattern (Pearce, 1991) considers motives like escape, relaxation, experiencing novelty, and building relationships as the core layer of tourism over built attractions. In this order, other tourist motivation scholars also explore the pursuit of positive experiences (Filep, 2014; Filep & Greenacre, 2007) and develop a new concept of positive tourism. In one way or another, from the Australian market report and case study, tourist behaviour researchers have shaped Australian Tourism practices regarding attractions, marketing, development and execution philosophy towards the new concept of positive tourism experiences.

However, Cohen (1972) argued that tourists seek not only to fulfil their psychological needs but also to experience the true essence of the destination. Pearce (1991) also suggested that motivation evolves within the travel career ladder, while the push-pull theory does not adequately account for these dynamics. Therefore, tourist travel patterns depend on their experience and life cycle as well as their needs and wants (Pearce, 1991; Herbert, 1996; Peters & Weiermair, 2016). Thus, to satisfy these needs, tourists are not only confined to visiting buildings or specific primary attractions like most attractions in Hong Kong and England; instead, they demand an inclusive experience of the overall visit to a given destination. Numerous scholars have argued that providing tourists with opportunities to engage in meaningful and enjoyable activities is crucial for the success of tourism enterprises (Wall & Mathieson, 2006; Bowen & Clarke, 2009; Morgan, 2010; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Unlike the built attractions, which are still crucial as attractions, tourists are increasingly interested in experiencing authentic aspects of society and tourism products (Ramkissoon & Uysal, 2018).

Even if there are efforts in Hong Kong and England in tourism activities and marketing strategies, Australian Tourism is highly influenced by tourists’ concepts and theories of emotion, motivation, and experience, rather than relying purely on traditional demographic segments. Australian Tourism believes that even if tourists are of similar age, income, and gender, they may have different attitudes, interests, and behaviours. Therefore, they segment and target their consumers based on psychographic aspects, such as attitudes, interests, and behaviours. The segmented and targeted tourists for Australian tourism are those identified as travellers who enjoy experiences and satisfy their needs by visiting Authentic Australia, positioned as the High-Value Traveller. The country attributes their motivational needs, and the majority pointed out that new knowledge and authenticity satisfy their visits. This approach challenges the widely accepted Push-Pull tourist motivation theory. However, some tourists have a mix of different needs and try to meet their attractions and the experiences they will encounter, which are not accounted for in the tourism plan (McKercher, 2017).

In comparison and analysis of the three case studies, the long-haul market is dominated by business travellers rather than short-haul leisure travellers in Hong Kong and England. Business tourists intend to travel alone, and they are more senior and male-dominated. Short-haul tourists prefer to rest, relax and escape from their daily routine, and short-haul business travellers engage in more shopping activities than long-haul travellers. Therefore, business tourists have specific needs and wants, which is why they participate in business events, and these events represent the attractions that satisfy their needs. On the other hand, vacation tourists, such as long-haul Australian visitors, have diverse needs and wants that need to be met, and they require more attractions and activities at the destination. These enormous ranges of needs and wants of tourists can be satisfied by any destination and its attractions (Wong et al., 2016; McKercher, 2008; Botti et al., 2008; McKercher & Wong, 2021).

Similar to the studies by Mckercher (2008) and Ho & Mckercher (2014), long-haul tourists are generally older and have more extended night stays than short-haul tourists. This trend is particularly noticeable among Australian visitors, with an average duration of 36 days. Similarly, in these studies, there was a substantially larger number of young short-haul tourists than in the long-haul markets, which is vividly observed in the case of England and Hong Kong visitors, emphasising the applicability of the push-pull model of tourist motivation in such built attraction-concentrated destinations. Young tourists prefer destinations with outdoor activities, good shopping centres, opportunities for socialising with the host community, and affordable travel (Tomić et al., 2014). As extracted from the case studies, the travel career pattern (Pearce, 1991) and the General-Specific tourist needs continuum (McKercher, 2017) are likely applicable, as the aged and experienced travellers are generally motivated and visit places for educational, appreciative, and self-development purposes, similar to Australian visitors. In contrast, younger and inexperienced individuals travel for specific motives of relaxation and escape, likely in Hong Kong and England, staying for shorter periods and only visiting the built-in attractions.

5.2. Travel Need-Career-Attraction Nexus framework

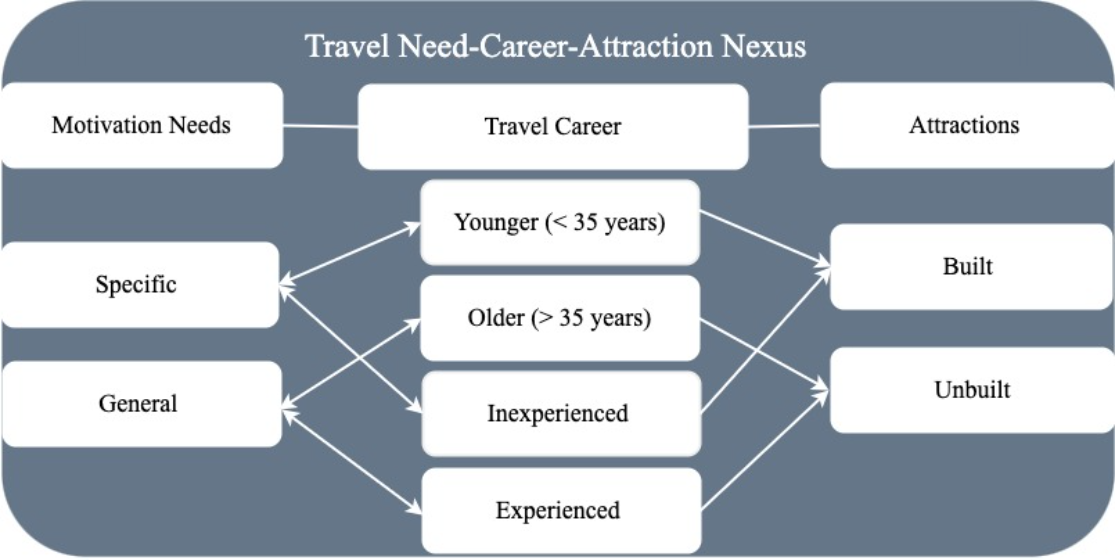

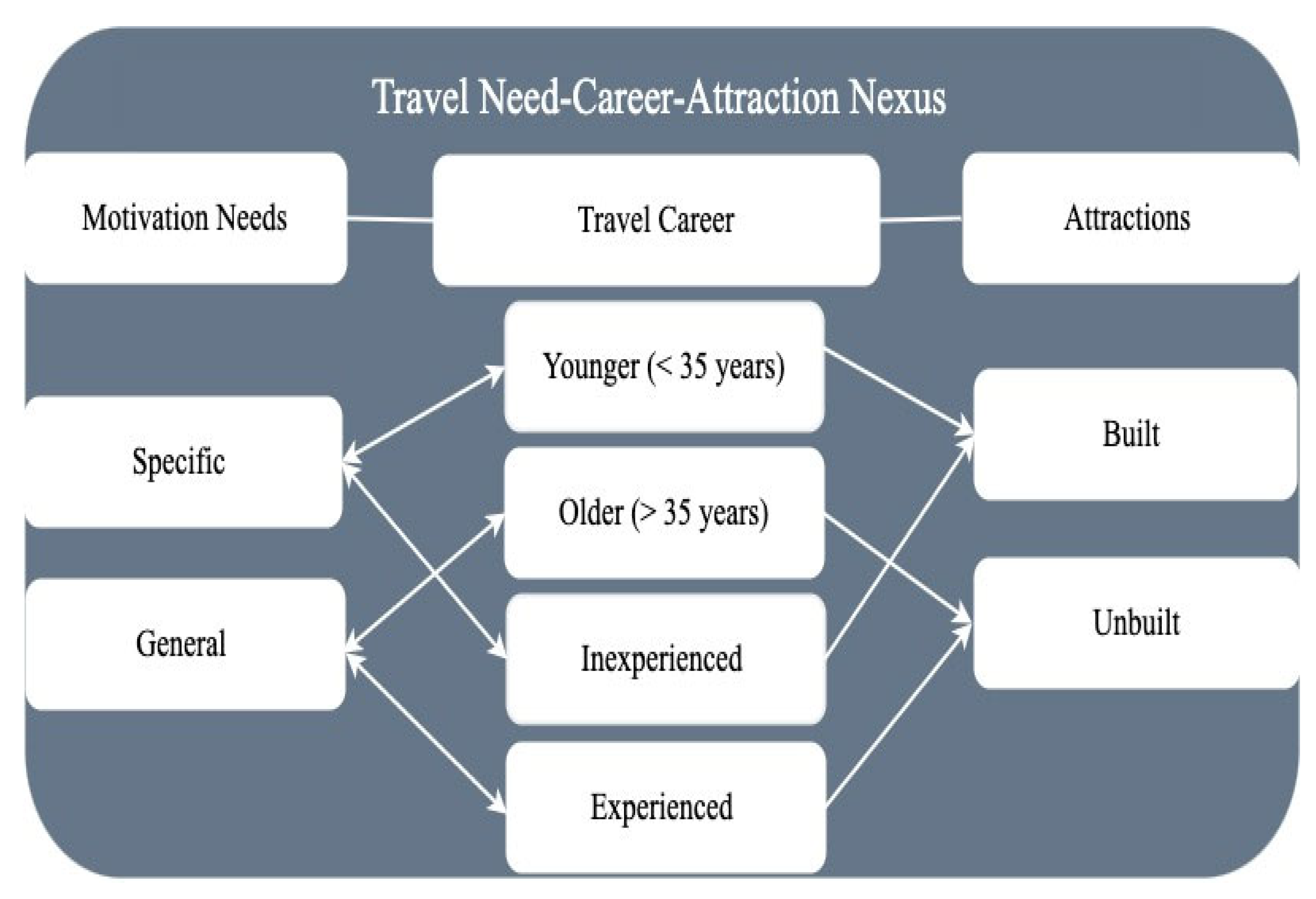

Following exploring and analysing various theories and models (Maslow, 1943; Plog, 1974; Pearce, 1991; Ryan, 1998; McKercher, 2017) and applying case studies, authors develop an innovative theoretical and conceptual framework that addresses tourist motivational needs, travel careers, and attractions. This is aptly called the Travel Need-Career-Attraction Nexus framework and is illustrated below in

Figure 1.

The framework elucidates the intricate relationship between tourist motivation needs, travel careers, and attractions while interrelating with theoretical frameworks such as the travel personality model, travel career ladder, travel career pattern, and hierarchy of travel motivation. At the foundation of this framework are the motivation needs, which can be classified into specific and general categories. Specific needs, like the desire for relaxation, adventure, or cultural immersion, align with the hierarchy of travel motivation. This hierarchy posits that travellers progress from basic needs, such as safety and comfort, to higher-level desires for self-actualisation and meaningful experiences. The travel career component of the framework is divided by age, distinguishing younger travellers (under 35) from older travellers (over 35). This segmentation recognises the influence of the travel career ladder, which suggests that as individuals gain more travel experience, their motivations evolve. Younger travellers may prioritise exploration and novelty, often embodying traits from the travel personality model that emphasise openness to experience. In contrast, older travellers may focus more on relaxation and cultural enrichment, reflecting a more developed understanding of their travel preferences.

The distinction between inexperienced and experienced travellers within these age categories illustrates the travel career pattern. Inexperienced travellers, who often seek structured experiences, may gravitate towards built attractions such as theme parks and popular landmarks. These attractions provide familiarity and comfort, aligning with their initial motivational needs. Meanwhile, experienced travellers are likelier to pursue unbuilt attractions that offer authenticity and novelty. This pursuit aligns with higher motivational needs for self-discovery and personal growth, echoing the principles outlined in the hierarchy of travel motivation. Ultimately, the interplay between motivation needs, travel careers, and attractions in this framework highlights the complexity of tourist experiences and underscores how various theoretical models can enhance the understanding of travel behaviours and preferences.

6. Conclusions

Since many tourists engage in different activities after arriving at their destinations, it is not straightforward to argue why tourists visit South Africa, Hong Kong, Australia, and England. It should be addressed, even if it is a predetermined visit, whether due to the presence of attractions or the need to satisfy. Therefore, whether attractions “attract” tourists depends on how the attraction is defined, the purpose of tourists’ visits, their engagement in activities, and their needs and wants. Most vacation tourists visit destinations because of the presence of attractions, rather than a specific attraction. However, the attractions attracted many business tourists to satisfy their demands. Therefore, the importance of built attractions increases if the needs of tourists are specific and limited, which adheres to the push-pull theory. However, if the demands are broad and undefined, the power of a particular attraction to attract tourists will be nominal, as there will be a wide array of substitute attraction sets in the destination (McKercher & Wong, 2021; McKercher & Koh, 2017).

The various tourist motivation approaches and theories remain relevant, including the widely recognised push-pull motives. However, nowadays, these approaches may not be entirely applicable to all tourist segments because technology and society have evolved rapidly, and tourist needs and motivations, as reflected in the travel career pattern model, require variability in experience and age. These unique travel patterns give rise to a new tourism typology, including slum, volunteer, farm, and ecotourism, with an emphasis on authenticity and experiential flows rather than focusing on building and specified iconic attractions. In certain circumstances, distinguishing tourists from non-tourists is becoming increasingly challenging, as visitors are now interested in being fully immersed in the experience and flow, necessitating a revision of today’s definition of tourism and a critique of the push-pull theory. Surprisingly, tourists indirectly become part of the attraction and tourism services, irrespective of the primary and built attractions. Despite this, it’s difficult to underestimate the attraction’s role in satisfying tourists’ needs. However, focusing exclusively on and promoting the traditional conception of attractions implies a deterrent effect, as it will not address tourists with broad and substitutable tourism product needs.

Today’s research-based marketers, such as those in Australian tourism, go beyond merely promoting built and individualised attractions, as tourists with diverse motives are less likely to be addressed. It will inevitably shift the marketing approach from a specific to an inclusive one, focusing on the satisfaction of tourists’ needs who are motivated by experience, well-being, and authenticity. It is worth noting that attractions are a significant part of tourism demand, particularly for tourists with specific needs, such as those visiting friends and relatives and business travellers. However, contemporary marketers understand that attractions are not the end for all tourists; they are a means for tourists with more general and diverse attraction needs in each destination. In conclusion, following a thorough examination of various theories and case studies, the authors propose a novel theoretical and conceptual framework, known as the Travel Need-Career-Attraction Nexus. This innovative model presents a promising avenue for future research, aligning with emerging trends in understanding and marketing attractions. It emphasises the importance of addressing tourist satisfaction within today’s dynamic tourism experience economy, where positive experiences are paramount. Similarly, like Australian Tourism, the country’s head of tourism boards would rather question the traditional push-pull theory, learn about new trends in tourism and tourists’ motivational needs, and act in formulating and executing their tourism development and marketing strategies.

6.1. Limitations and Future Research Avenue

While the study comprehensively examines the interplay of tourist attractions and motivations, it is essential to recognise certain limitations that may impact the findings. Firstly, although the qualitative case study approach provides valuable insights, it limits the ability to generalise the findings beyond the specific cases being studied. The subjective nature of qualitative research can lead to biases that may not fully capture the diverse experiences and motivations of all tourists. Focusing on four specific destinations—South Africa, Hong Kong, Australia, and England — may not represent the complete range of global tourism trends. Each destination has unique cultural, social, and economic contexts that shape tourist motivations. Future research could benefit from employing mixed methods approaches, combining qualitative insights with quantitative data to enhance robustness and generalizability. Thus, expanding the study to include a broader range of destinations, particularly those in emerging markets or less-studied regions, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of how different attractions resonate with diverse motivations. Secondly, while this research incorporates various theoretical concepts and models, it may not address all relevant frameworks in the tourism field.

Future studies could explore additional theories, such as the experience economy or the postmodern tourism paradigm, to deepen the analysis of tourist behaviour and attraction dynamics. Another limitation is the reliance on existing market reports and secondary data, which may not capture the latest tourist motivations and behaviour trends, especially in a rapidly evolving tourism landscape influenced by technological advancements and global events. Ongoing research should prioritise real-time data collection through surveys and interviews with tourists to keep pace with shifting motivations and expectations. Lastly, this study highlights the need for a deeper exploration of how socio-cultural factors influence tourist motivations and choices. Future research could delve into the impact of cultural exchanges, social media, and globalisation on tourist behaviour, thereby enriching the discourse on tourism dynamics. Although the study contributes important perspectives on the link between attractions and motivations, addressing its limitations and exploring the proposed avenues for subsequent research will enhance awareness of tourism as a multifaceted experience. Therefore, such studies will ultimately empower tourism stakeholders to adjust their strategies more effectively to respond to the evolving demands of tourists.