1. Introduction

Cancer continues to be a major global health challenge, with an estimated 19.3 million new cases and 1 million cancer-related deaths reported annually [

1]. Despite substantial advancements in cancer therapy, including immunotherapy and molecular-targeted treatments, systemic chemotherapy remains the cornerstone of treatment for Gastrointestinal malignancies. Among the standard chemotherapy regimens for gastrointestinal cancers, oxaliplatin-based protocols, such as S-1 plus oxaliplatin, oxaliplatin with capecitabine, and oxaliplatin combined with leucovorin and fluorouracil (FOLFOX), continue to be widely utilized. These regimens are frequently employed as first- and second-line therapies for gastrointestinal tract tumors, making their use nearly unavoidable. In pancreatic cancer, the FOLFIRINOX regimen, comprising oxaliplatin, irinotecan, leucovorin, and 5-fluorouracil, has emerged as an intensive first-line option, particularly for patients with good performance status, offering improved survival at the cost of increased toxicity [

2].

A major complication of chemotherapy is chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia (CIT), which results from the suppression of bone marrow megakaryocytes, leading to a decline in peripheral platelet counts below 100 × 10⁹/L [

3]. Among patients with solid tumors, CIT is most commonly observed in non-small cell lung cancer (25%), ovarian cancer (24%), and colorectal cancer (18%) [

4]. A retrospective hospital-based study conducted in the Netherlands, which included over 600 adult patients receiving chemotherapy for solid tumors, reported that 22% of patients developed thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 100 × 10⁹/L) [

5]. The highest incidence was observed in patients receiving carboplatin monotherapy (82%) and oxaliplatin monotherapy (50%). Additionally, combination regimens involving carboplatin (58%), gemcitabine (64%), and paclitaxel (59%) were also associated with an increased risk of thrombocytopenia [

5].

CIT remains a frequent and clinically significant complication in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy, affecting approximately 20–25% of individuals with solid tumors [

4,

6]. CIT’s incidence, severity, and duration vary widely based on the specific chemotherapeutic agents and their administered doses [

4,

6]. Notably, regimens containing gemcitabine and platinum-based compounds are associated with a particularly high risk of thrombocytopenia, defined as platelet counts dropping below 150 G/L. Reported thrombocytopenia rates in patients receiving gemcitabine-based therapy are as high as 64%, while those undergoing treatment with platinum-containing agents experience rates of 56% [

4].

2. Pathophysiology

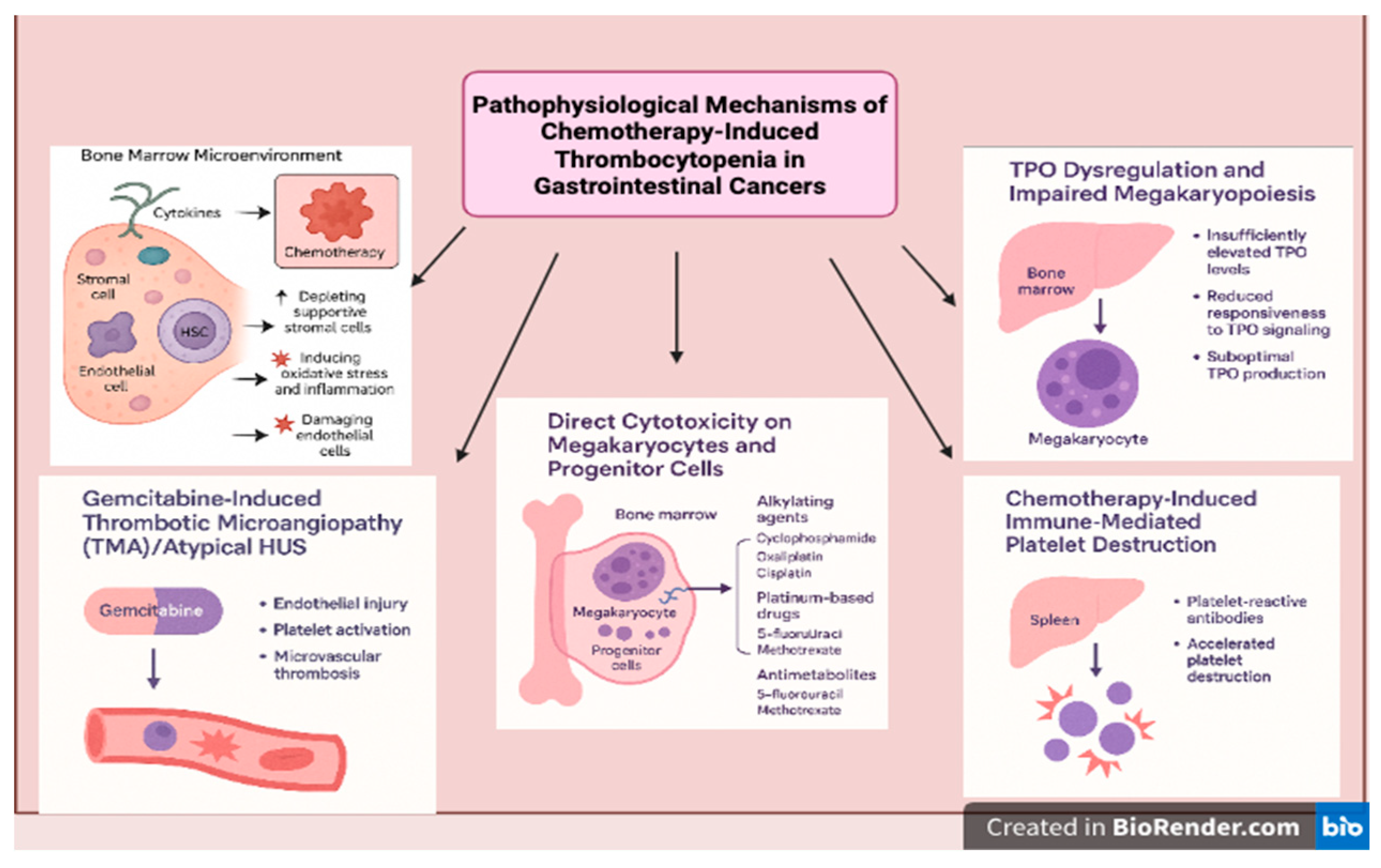

Outlined below are the distinct and interconnected pathophysiological processes that contribute to the development of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia (CIT), reflecting its complex biological underpinnings (

Figure 1).

2.1. Direct Cytotoxicity on Megakaryocytes and Progenitor Cells

Chemotherapeutic agents, particularly alkylating agents (e.g., cyclophosphamide), platinum-based drugs (e.g., oxaliplatin, cisplatin), and antimetabolites (e.g., 5-fluorouracil, methotrexate), are known to damage actively proliferating cells. Since HSPCs and megakaryocyte progenitors in the bone marrow undergo rapid division, they are particularly susceptible to chemotherapy-induced apoptosis and DNA damage, leading to platelet-producing cell depletion and thrombocytopenia [

7].

A notable example is oxaliplatin-induced thrombocytopenia, which can occur acutely due to immune-mediated destruction or chronic marrow suppression. Oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy regimens, commonly used for gastrointestinal cancers, have been associated with acute thrombocytopenia, sometimes leading to treatment delays or dose reductions [

8]

Table 1.

2.2. Disruption of the Bone Marrow Microenvironment

The bone marrow niche supports hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) maintenance and differentiation and consists of stromal cells, endothelial cells, and cytokines that regulate hematopoiesis. Chemotherapy alters this microenvironment by:

Depleting supportive stromal cells, impairing their ability to secrete essential growth factors (e.g., TPO, interleukins).

Inducing oxidative stress and inflammation, disrupting normal HSC function.

Damaging endothelial cells, which are crucial for sustaining the BM niche and protecting stem cells from toxic insults [

7].

As a result, megakaryopoiesis is severely compromised, leading to inadequate platelet production and a higher risk of bleeding complications. Furthermore, studies have shown that platinum-based chemotherapy and targeted therapies can cause long-term suppression of bone marrow progenitor cells, further worsening CIT in cancer patients [

20] (

Table 2).

2.3. TPO Dysregulation and Impaired Megakaryopoiesis

Thrombopoietin (TPO) is crucial for platelet production, as it stimulates the differentiation and maturation of megakaryocytes. Under normal conditions, when platelet levels drop, TPO levels rise to compensate. However, chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression disrupts this process in several ways:

TPO levels may be insufficiently elevated to compensate for platelet loss.

Megakaryocyte precursors may have reduced responsiveness to TPO signaling due to drug-induced cellular damage.

The liver, which produces TPO, may also be affected by chemotherapy, leading to suboptimal TPO production [

21].

These factors collectively exacerbate thrombocytopenia and delay platelet recovery after chemotherapy. Studies have explored the use of TPO receptor agonists (e.g., eltrombopag, romiplostim) to mitigate CIT, with promising results in clinical trials [

22] (

Table 3).

2.4. Immune-Mediated Platelet Destruction

Certain systemic therapy, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapies, can inadvertently trigger an immune response against platelets or megakaryocytes, leading to their accelerated clearance from circulation. This is observed in some patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., pembrolizumab, nivolumab), which can cause immune thrombocytopenia (ITP)-like syndromes in addition to myelosuppressive effects.

Furthermore, drug-associated thrombocytopenia has been linked to platelet-reactive antibodies, which accelerate platelet destruction in the spleen. Studies suggest that drug-induced thrombocytopenia can occur through immune-mediated pathways, particularly with certain chemotherapy drugs and monoclonal antibodies [

23].

Table 4.

Immune-Mediated Platelet Destruction.

Table 4.

Immune-Mediated Platelet Destruction.

| Mechanism |

Associated Chemotherapeutic Agents |

Clinical Consequences |

References |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced thrombocytopenia |

Pembrolizumab, nivolumab |

Increased platelet destruction, ITP-like syndrome |

ASH, 2018 [23] |

| Drug-associated platelet-reactive antibodies |

Monoclonal antibodies, targeted therapies |

Accelerated platelet clearance in spleen, worsening thrombocytopenia |

ASH, 2018 [23] |

| T-cell-mediated platelet destruction |

Some targeted therapies and immune-based treatments |

Increased risk of severe bleeding complications |

ASH, 2018 [23] |

2.5. Gemcitabine Induced Thrombotic Microangiopathies (TMA)/Atypical HUS

Gemcitabine-induced thrombotic microangiopathy (GiTMA) is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication observed in patients receiving gemcitabine-based chemotherapy, particularly for pancreatic and other gastrointestinal cancers. The incidence of GiTMA is estimated to range between 0.015% and 0.31% of treated patients, though some single-center studies suggest higher rates in heavily pretreated populations [

24]. The pathogenesis is thought to involve direct endothelial injury, resulting in platelet activation, microvascular thrombosis, and complement activation particularly through the alternative pathway, resembling atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) [

25,

26]. Clinically, patients present with the triad of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute kidney injury, often accompanied by hypertension and proteinuria. Management includes prompt discontinuation of gemcitabine and supportive care, such as dialysis when indicated. While the role of plasma exchange remains unclear, eculizumab, a complement C5 inhibitor, has shown promise in select patients, particularly those with complement dysregulation [

27].

3. Incidence of CIT-Induced Thrombocytopenia

According to the NCCN guidelines, CIT is defined as a platelet count of <100 × 10⁹/L persisting for ≥3 to 4 weeks after the last chemotherapy administration and/or causing delays in chemotherapy initiation due to thrombocytopenia. A threshold of <100 × 10⁹/L is clinically significant, as it correlates with higher risks of treatment modifications, including dose delays, reductions, or discontinuations, and an increased likelihood of recurrence in future chemotherapy cycles [

28].

The Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) categorizes thrombocytopenia into four grades based on platelet counts: Grade 1: 75–100 × 10⁹/L, Grade 2: 50–75 × 10⁹/L, Grade 3: 25–50 × 10⁹/L, and Grade 4: <25 × 10⁹/L. The clinical impact of thrombocytopenia aligns with these grades, ranging from mild, asymptomatic cases with petechiae to life-threatening hemorrhagic events, such as intracranial or gastrointestinal bleeding [

29,

30]. The grades are also clinically categorized based on bleeding severity. Grade 1 corresponds to petechiae, Grade 2 to mild blood loss, Grade 3 to gross blood loss, and Grade 4 to debilitating blood loss [

31] (

Table 5).

Although platelet count is a key predictor of bleeding risk, other factors significantly contribute to bleeding complications in CIT. Platelet function, the rate of platelet decline, infections, kidney insufficiency, underlying coagulopathies, and the concomitant use of antithrombotic agents all modulate the overall bleeding risk [

15]. These factors may explain why some patients with moderate thrombocytopenia experience severe bleeding while others with very low platelet counts remain asymptomatic. Further research is needed to refine risk assessment models beyond platelet thresholds and incorporate functional platelet activity and patient-specific risk factors into CIT management strategies.

4. Discussion

Among solid tumors, gastrointestinal malignancies are particularly prone to CIT, due to both disease-related factors and the intensive chemotherapy regimens used for treatment, contributing to treatment delays, dose modifications, and increased bleeding risk. The incidence of CIT varies depending on tumor type, patient characteristics, and treatment regimen, with some studies reporting rates ranging between 13–40% in patients receiving chemotherapy for GI cancers [

15,

29]. The risk of thrombocytopenia is further exacerbated in patients with underlying liver dysfunction, which is common in GI cancers such as hepatocellular carcinoma and metastatic colorectal cancer. Additionally, thrombocytopenia in these patients is not only a consequence of myelosuppressive chemotherapy but also may be influenced by splenic sequestration and compromised thrombopoiesis due to liver disease [

32].

Given the high incidence of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia (CIT) in GI cancers, it is essential to evaluate which chemotherapy regimens contribute most significantly to this complication and how they impact treatment outcomes. Fluoropyrimidines (5-fluorouracil and capecitabine), gemcitabine, platinum-based agents (oxaliplatin and cisplatin), and irinotecan are among the most frequently used cytotoxic drugs in the treatment of GI malignancies, either as monotherapy or in combination regimens.

Multiple retrospective studies have investigated chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia (CIT) in solid tumors. In a large retrospective study by Shaw et al., 13% of patients with solid tumors developed thrombocytopenia, with the highest incidence observed in patients receiving gemcitabine and platinum-based therapies [

29]. Similar findings were reported in a retrospective study of 47,159 patients, reinforcing the association between CIT and both platinum-based and gemcitabine-containing regimens [

4].

In a recent meta-analysis on metastatic colorectal cancer by Zhan et al. (2024) [

20], the Surface Under the Cumulative Ranking (SUCRA) values were used to assess the risk of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia (CIT) across different regimens. The analysis found that CAPIRI + bevacizumab (capecitabine and irinotecan with bevacizumab), FOLFIRI + bevacizumab (5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan with bevacizumab), and CAPIRI + cetuximab (capecitabine and irinotecan with cetuximab) had the lowest risk of thrombocytopenia, ranking highest in safety. Conversely, S-1 + oxaliplatin, FUOX, FOLFOXIRI + bevacizumab, and IROX exhibited a higher risk of thrombocytopenia, as reflected by their lower SUCRA scores. Notably, the study also observed that platinum-containing regimens were more strongly associated with thrombocytopenia, highlighting the need for close platelet monitoring in patients receiving these treatments [

20]. Among combination regimens, FOLFIRINOX has been linked to a higher incidence of Grade 3-4 thrombocytopenia compared to gemcitabine alone [

2] (

Table 6).

5. Management

The management of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia (CIT) requires a comprehensive approach, considering the underlying cause, chemotherapy regimen, and treatment goals. Before initiating specific interventions, it is crucial to evaluate for secondary causes of thrombocytopenia, such as infection, coagulopathy, bone marrow suppression, or concurrent medications that may exacerbate platelet suppression [

15]. In CIT, depending on chemotherapy regimen and risk of myelosuppression, platelet nadir and recovery varies. However, the depth of the platelet nadir may worsen with successive chemotherapy cycles, leading to an increased risk of bleeding and the need for treatment modifications [

28].

One major strategy is to reduce the chemotherapy frequency or dosage. This is usually preferred if the therapy is not standard or not of curative intent [

6]. A retrospective analysis evaluating irinotecan-based (FOLFIRI) and oxaliplatin-based (mFOLFOX6) regimens in metastatic colorectal cancer patients demonstrated that maintaining higher relative dose intensity (RDI) of irinotecan was significantly associated with improved outcomes (PFS: 9.9 vs. 5.6 months and OS: 26.7 vs. 12.9 months) [

33]. These findings underscore the critical balance between managing CIT and preserving chemotherapy dose intensity to optimize patient outcomes.

Platelet transfusion is a key intervention in the management of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia (CIT), particularly for patients at high risk of bleeding or those experiencing active hemorrhage. According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines, prophylactic platelet transfusions are recommended when platelet counts fall below 10 × 10⁹/L in solid tumors. A higher threshold can be used in case of bleeding or necrotic tumors [

34]. A few studies mention <20 × 10⁹/L if the patient is febrile [

15]. However, platelet transfusions have several limitations, making their use less ideal for long-term management. One of the main concerns is their short-lived effect—transfused platelets survive only 3-5 days [

6,

35]. Additionally, repeated transfusions can lead to alloimmunization, where patients develop HLA antibodies, making subsequent transfusions less effective and increasing the risk of platelet refractoriness. Patients who become refractory may require HLA-matched platelets [

35]. Furthermore, platelet transfusions carry risks of transfusion-related reactions, infections, and thrombotic complications [

36]. Given these limitations, platelet transfusions should be used judiciously, mainly for acute management of severe thrombocytopenia or active bleeding.

In patients with liver cirrhosis, splenic sequestration often contributes to persistent thrombocytopenia, which can complicate the administration of systemic chemotherapy. Partial splenic embolization (PSE) offers a minimally invasive strategy to mitigate hypersplenism by reducing splenic blood flow, thereby increasing circulating platelet counts. This approach has shown effectiveness in improving hematologic parameters, enabling safer delivery of chemotherapy in select cirrhotic patients. A prospective phase II study demonstrated that PSE enabled 94% of patients with gastrointestinal cancers to resume chemotherapy within a median of 14 days post-procedure, significantly improving platelet counts and minimal procedure-related morbidity [

37]. Compared to splenectomy, PSE carries a lower procedural risk and can be tailored to minimize complications such as infarction or portal vein thrombosis [

38].

Antifibrinolytic agents like ε-aminocaproic acid and tranexamic acid have been considered for managing bleeding in thrombocytopenic cancer patients when platelet transfusions are ineffective. However, their clinical benefit remains unproven, and their use may increase thrombotic risk, particularly in cancer patients [

6,

15].

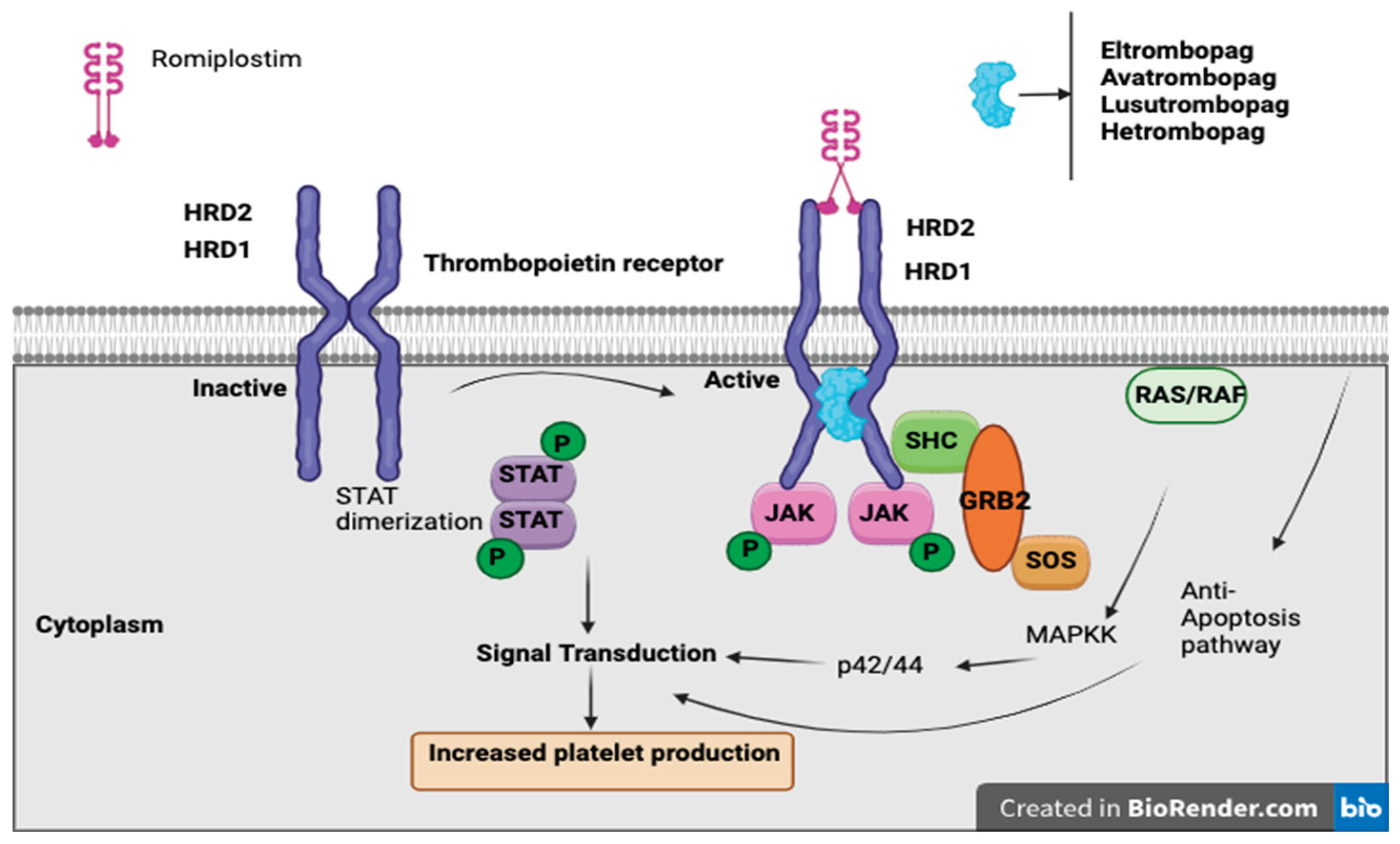

Thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) have emerged as a promising therapeutic option for managing chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia (CIT), particularly in patients with solid tumors. These agents, including romiplostim, eltrombopag, and avatrombopag, function by stimulating the thrombopoietin receptor, thereby enhancing megakaryocyte proliferation and increasing platelet production. Their use aims to maintain chemotherapy dose intensity, reduce the need for platelet transfusions, and mitigate bleeding risks associated with CIT.

Thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) are a class of drugs that bind to and activate the TPO receptor (MPL), stimulating megakaryocyte proliferation, differentiation, and platelet production, without containing the peptide sequence of endogenous thrombopoietin [

39]. There are currently four available TPO-RAs: romiplostim, a “peptibody” administered via weekly subcutaneous injection, and eltrombopag, avatrombopag, and lusutrombopag, which are oral small-molecule agents [

40]. While TPO-RAs are FDA-approved for conditions such as immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), hepatitis C-associated thrombocytopenia, aplastic anemia, and periprocedural thrombocytopenia in chronic liver disease, their role in CIT remains under investigation. To date, only studies involving romiplostim have shown a significant benefit in CIT, whereas other agents require further evaluation [

40].

Romiplostim, a subcutaneous TPO-RA, has demonstrated CIT, enabling chemotherapy continuation and reducing the need for platelet transfusions

(Figure 2). In a retrospective study of 20 cancer patients with platelet counts <100 × 10⁹/L and prior chemotherapy dose delays or reductions, romiplostim increased platelet counts in all patients, with 19/20 achieving ≥100 × 10⁹/L and 15 resuming chemotherapy, of whom 14 completed at least two more cycles without modifications [

41].

A phase II trial evaluated weekly romiplostim in CIT, where over half of the patients had primary gastrointestinal malignancies, and nearly 50% had primary or metastatic liver involvement. Romiplostim led to platelet recovery (≥100,000/μL) within 3 weeks in 93% (14/15) of treated patients, compared to only 12.5% (1/8) in the observation group. Mean platelet counts increased from 63,000/μL to 141,000/μL, allowing for safe chemotherapy resumption, and none of the romiplostim-treated patients required platelet transfusions. Due to the strong statistical significance (P < 0.001) and lack of spontaneous platelet recovery in the control group, the trial was converted into a single-arm, open-label study, where 85% (44/52) of patients achieved platelet correction within 3 weeks. Among those who resumed chemotherapy with romiplostim maintenance, 64% continued the same chemotherapy regimen, and 58% of those who previously required dose reductions were able to return to full or increased dosing. Only 6.8% (3/44) experienced CIT recurrence, leading to dose modifications. 10.2% of patients developed venous thromboembolism (VTE), but romiplostim was not discontinued due to VTE, and there was no observed increase in myocardial infarction or stroke risk. These findings reinforce romiplostim’s potential to restore platelet counts, sustain chemotherapy dose intensity, and minimize transfusion dependency while maintaining a stable safety profile [

42].

In addition to romiplostim, several other TPO-RAs, including eltrombopag, avatrombopag, and lusutrombopag, have been explored for CIT. In a phase II study of solid tumors receiving gemcitabine monotherapy or gemcitabine with cisplatin/carboplatin, eltrombopag failed to show a significant improvement in platelet nadir compared to placebo [

43]. Similarly, a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study evaluating the use of avatrombopag in non-hematological malignancies showed no difference in CIT between avatrombopag and placebo group [

44].

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, S.P. and R.I; methodology, S.P; software, A.D; validation, S.P. and R.I; formal analysis, K.T and S.P.; investigation, S.P and A.D.; resources, S.P; data curation, S.P and A.D; writing—original draft preparation, S.P.; writing—review and editing, S.P , A. D; visualization, S.P.; supervision, S.P , J.K , K.T.; project administration, J.K , S.P .; funding acquisition, R.I All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.