Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

28 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

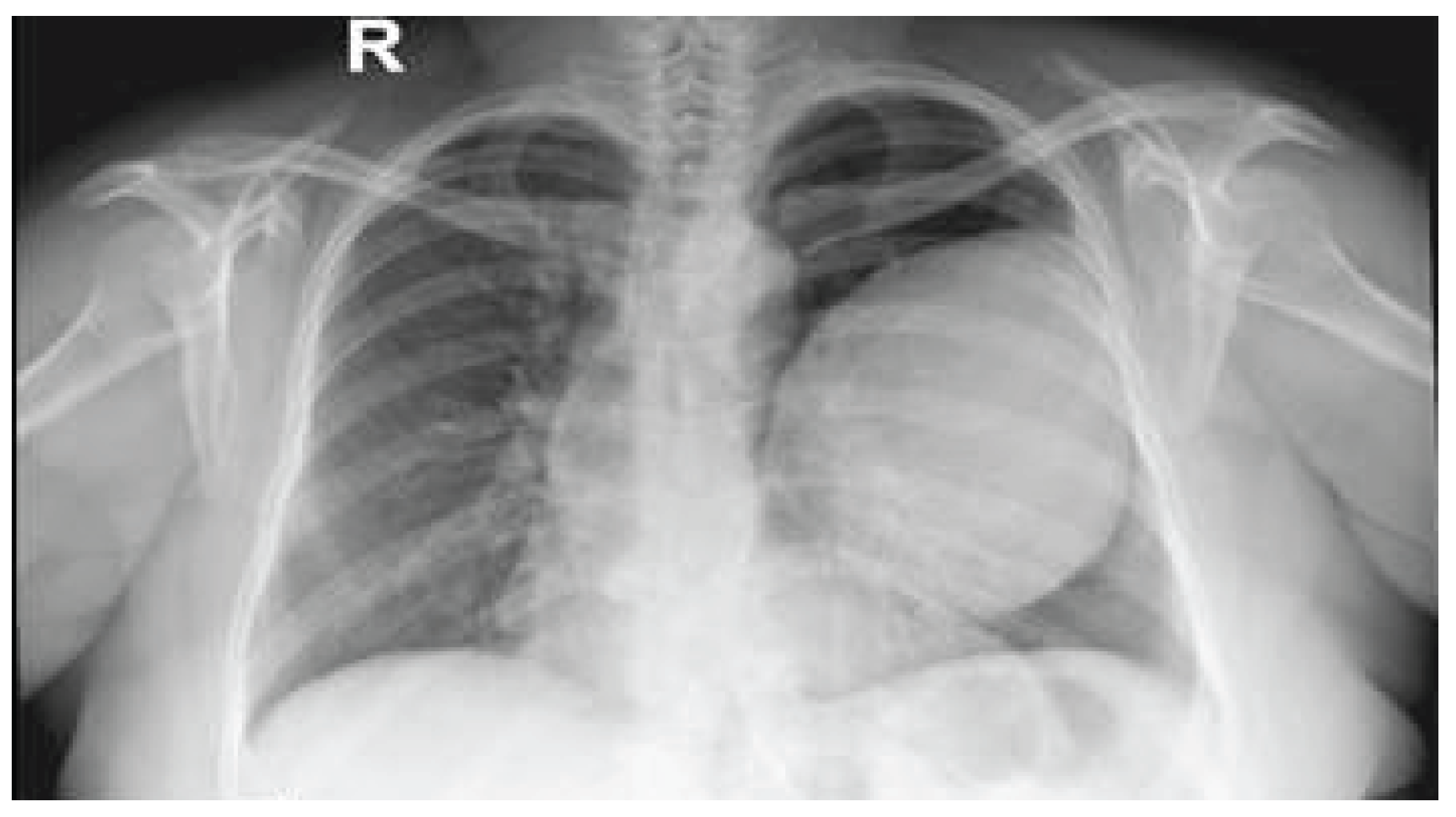

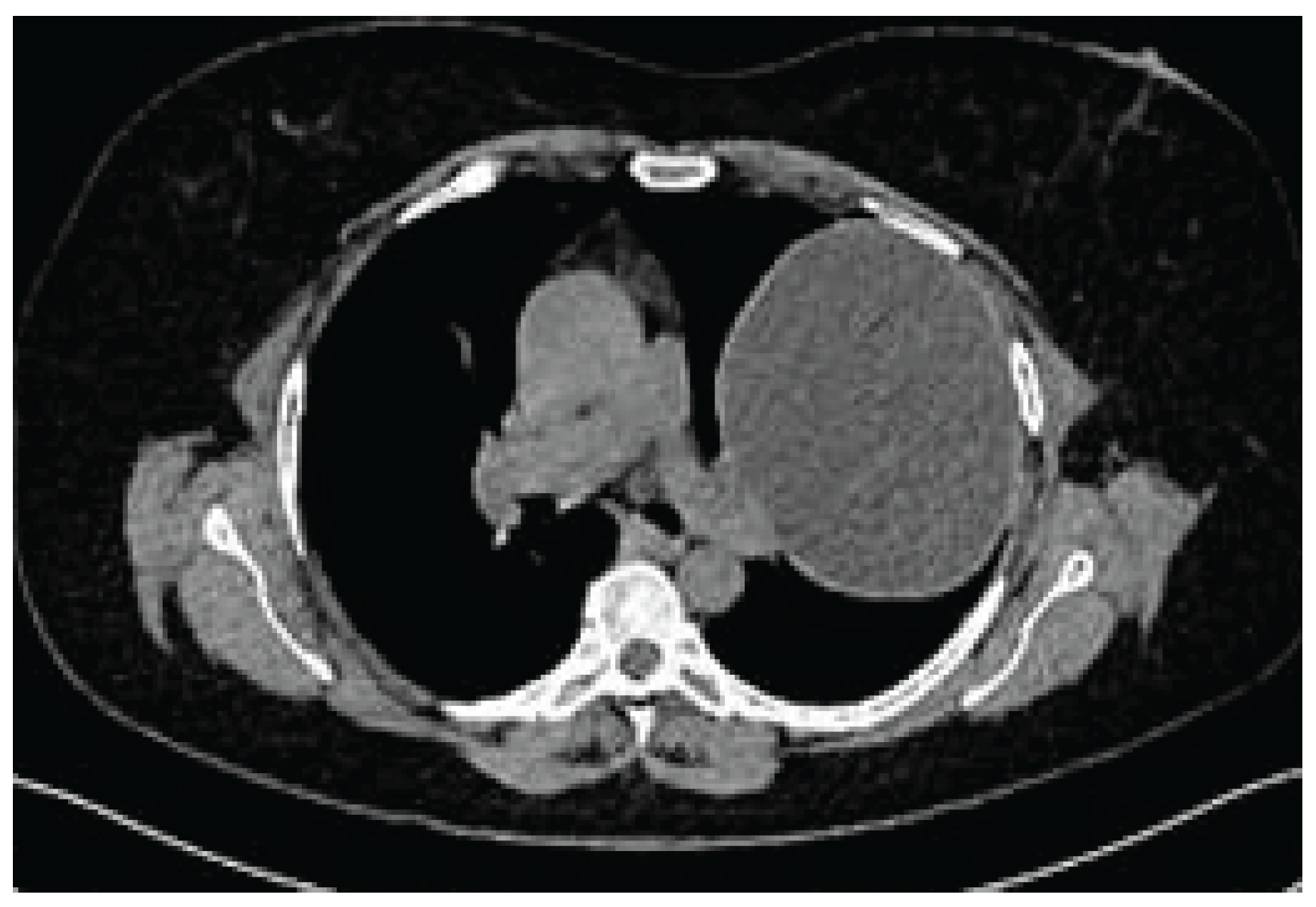

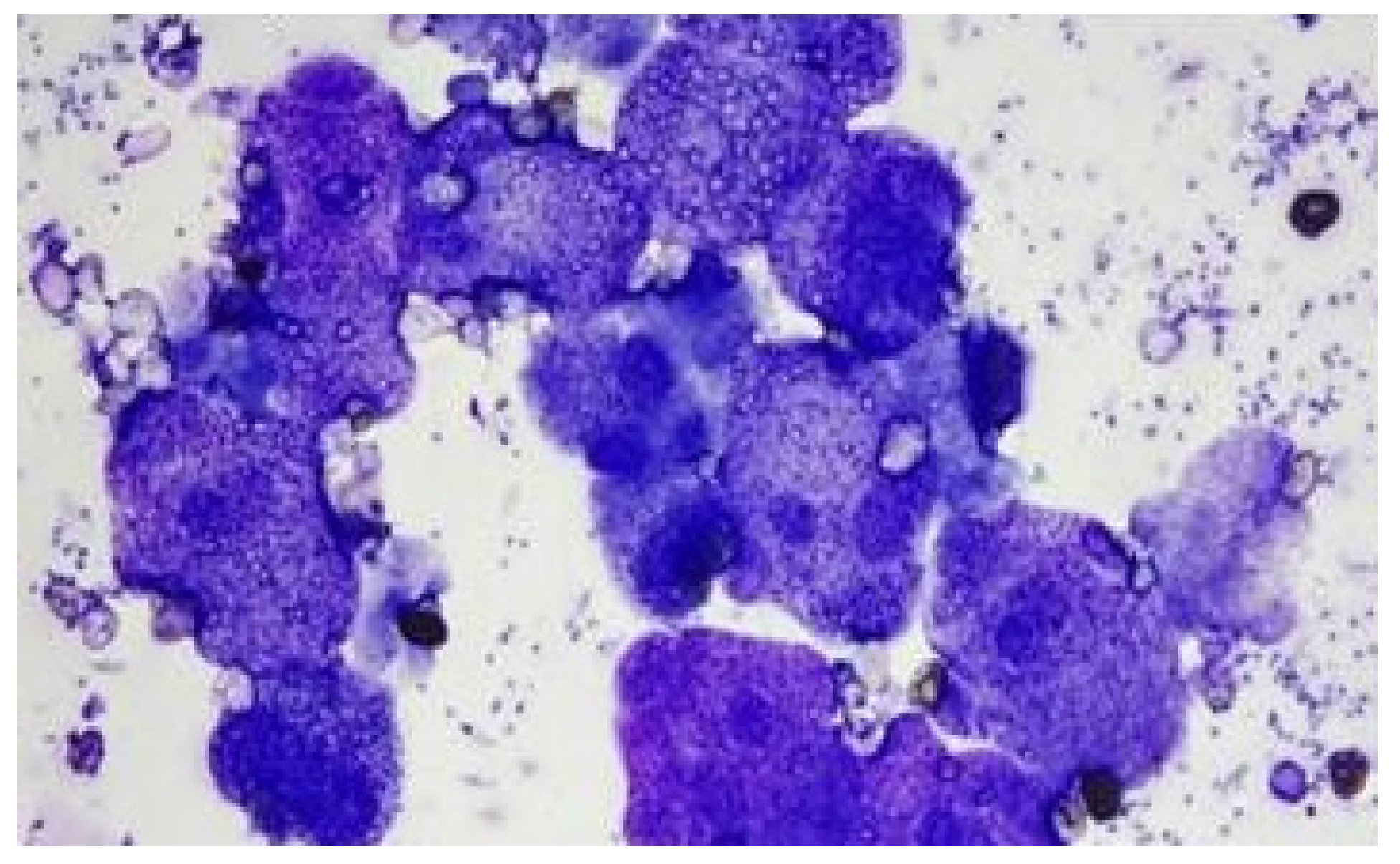

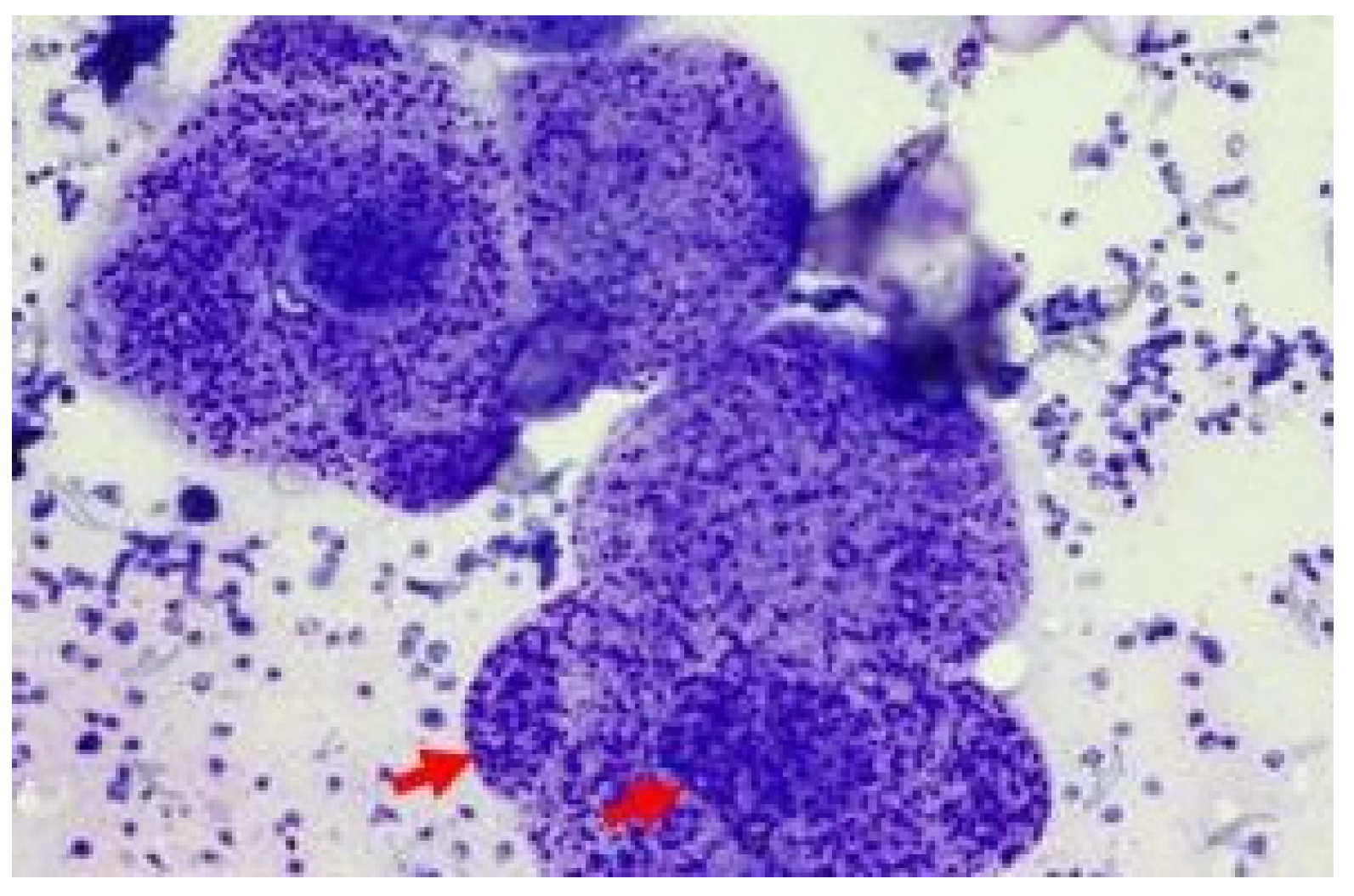

Case

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusions

Funding

Ethical statement

Acknowledgements

Declaration of competing interest

References

- Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Bolivar-Mejia, A.; Calvo-Betancourt, L.S.; Alarcón-Olave, C. Echinococcosis in Colombia — A Neglected Zoonosis? In Current Topics in Echinococcosis; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessese, A.T. Review on Epidemiology and Public Health Significance of Hydatidosis. Vet Med Int 2020, 2020, 8859116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Sarmiento, D.; Chiluisa-Utreras, V. First molecular identification of hydatid tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato G6/G7 in Ecuador. J Helminthol 2019, 94, e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, F.; Verdugo, C.; Cárdenas, F.; Sandoval, R.; Morales, N.; Olmedo, P.; Bahamonde, A.; Aldridge, D.; Acosta-Jamett, G. Echinococcus Granulosus in the Endangered Patagonian Huemul (Hippocamelus bisulcus). J Wildl Dis 2019, 55, 694–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, S.; McSpadden, K.; Baker, S.; Jenkins, D.J. Occurrence of tongue worm, Linguatula cf. serrata (Pentastomida: Linguatulidae) in wild canids and livestock in south-eastern Australia. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl 2017, 6, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aili, A.; Peng, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Peng, L.; Yi, Q.; Zhou, H. Hydatid Pulmonary Embolism: A Case Report and Literature Review. Am J Case Rep 2021, 22, e934157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, A.; Al Rajhi, S. Case Report of Hydatid Cyst in the Pulmonary Artery Uncommon Presentation: CT and MRI Findings. Case Rep Radiol 2018, 2018, 1301072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, S.; Tek, C.; Dilek Gokharman, F.; Fatihoglu, E.; Nercis Kosar, P. Isolated hydatid cyst of thyroid: An unusual case. Ultrasound 2018, 26, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çobanoğlu, U.; Aşker, S.; Mergan, D.; Sayır, F.; Bilici, S.; Melek, M. Diagnostic Dilemma in Hydatid Cysts: Tumor-Mimicking Hydatid Cysts. Turk Thorac J 2015, 16, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; Prakash, M.; Khandelwal, N. Radiological manifestations of hydatid disease and its complications. Trop Parasitol 2016, 6, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, V.K.; Chopra, N.; Singh, P.; Venugopal, V.K.; Narang, S. Hydatid cyst of parotid: Report of unusual cytological findings extending the cytomorphological spectrum. Diagn Cytopathol 2016, 44, 770–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davakis, S.; Syllaios, A.; Kyros, E.; Garmpis, N.; Charalabopoulos, A. An extraordinary rare presentation of liver hydatidosis with hydatid cyst scolices. Clin Case Rep 2020, 8, 2298–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engström, E.L.S.; Salih, G.N.; Wiese, L. Seronegative, complicated hydatid cyst of the lung: A case report. Respir Med Case Rep 2017, 21, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khefacha, F.; Touati, M.D.; Bouzid, A.; Ayadi, R.; Landolsi, S.; Chebbi, F. A rare case report: Primary isolated hydatid cyst of the spleen- diagnosis and management. Int J Surg Case Rep 2024, 120, 109869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, Y.; Ulas, A.B.; Ahmed, A.G.; Eroglu, A. Pulmonary Hydatid Cyst in Children and Adults: Diagnosis and Management. Eurasian J Med 2022, 54, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koirala, D.P.; Yadav, M.; Shah, N.A.; Yadav, D.; Neupane, S.; Yadav, C. Giant isolated splenic hydatid cyst in a pediatric patient: A rare case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2024, 120, 109768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.; Tan, C.; Meredith, G.; Chard, R. Minimally invasive surgical resection of a large primary pulmonary hydatid cyst: A thoracoscopic approach. J Surg Case Rep 2023, 2023, rjad090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirlohi, S.H.; Tajfirooz, S.; Raji, H.; Akhavan, S. Coexistence of kidney and lung hydatid cyst in a child: A case report. Respir Med Case Rep 2024, 52, 102138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Ahmed, H.; Simsek, S.; Liu, H.; Yin, J.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Cao, J. Molecular characterization of human Echinococcus isolates and the first report of E. canadensis (G6/G7) and E. multilocularis from the Punjab Province of Pakistan using sequence analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2020, 20, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.; Pathania, R.; Jhobta, A.; Thakur, B.R.; Chopra, R. Cystic pulmonary hydatidosis. Lung India 2016, 33, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zou, Y.; Yin, C. Rare presentation of multi-organ abdominal echinococcosis: Report of a case and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2015, 8, 11814–11818. [Google Scholar]

- Heidari, Z.; Sharbatkhori, M.; Mobedi, I.; Mirhendi, S.H.; Nikmanesh, B.; Sharifdini, M.; Mohebali, M.; Zarei, Z.; Arzamani, K.; Kia, E.B. Echinococcus multilocularis and Echinococcus granulosus in canines in North-Khorasan Province, northeastern Iran, identified using morphology and genetic characterization of mitochondrial DNA. Parasit Vectors 2019, 12, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocerino, M.; Pepe, P.; Bosco, A.; Ciccone, E.; Maurelli, M.P.; Boué, F.; Umhang, G.; Pellegrini, J.; Lahmar, S.; Said, Y.; et al. An innovative strategy for deworming dogs in Mediterranean areas highly endemic for cystic echinococcosis. Parasit Vectors 2024, 17, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipas, M.J.; Fowler, D.R.; Bardsley, K.D.; Bangoura, B. Survey of coyotes, red foxes and wolves from Wyoming, USA, for Echinococcus granulosus s. l. Parasitol Res 2021, 120, 1335–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arıbaş, E.T.; Metin, B.; Dumanlı, A.; Arıbaş, O.K. Concomitant Occurrence of Hepatopulmonary hydatid Cysts in Turkey. Iran J Parasitol 2021, 16, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alene, D.; Maru, M.; Demessie, Y.; Mulaw, A. Evaluating zoonotic metacestodes: Gross and histopathological alterations of beef in north-west Ethiopia one health approach for meat inspection and animal management. Front Vet Sci 2024, 11, 1411272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Shrestha, A.K.; Deo, A.; Sharma, G.R. Intramuscular hydatid cyst of paraspinal muscle: A diagnostic challenge. Clin Case Rep 2023, 11, e8105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pangeni, R.P.; Regmi, P.R.; Khadka, S.; Timilsina, B. Ruptured pulmonary hydatid cyst presenting as hemoptysis in TB endemic country: A case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2022, 78, 103836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zayati, M.; Chaouch, M.A.; Mokni, S.; Maaref, M.; Gafsi, B.; Noomen, F. Peritoneal hydatidosis secondary to an asymptomatic liver hydatid cyst rupture: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2024, 123, 110220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onal, O.; Demir, O.F. The relation between the location and the perforation rate of lung hydatid cysts in children. Asian J Surg 2018, 41, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadashiva, N.; Shukla, D.; Devi, B.I. Rupture of Intraventricular Hydatid Cyst: Camalote Sign. World Neurosurg 2018, 110, 115–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichimura, H.; Ozawa, Y.; Shiigai, M.; Shiotani, S.; Kikuchi, K.; Sato, Y. Enlarged mediastinal air cyst in a patient with bronchial diverticula localized in the left main bronchus: A case report with surgical and bronchoscopic findings. Surg Case Rep 2017, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawar, P.A.; Deshmukh, P.P.; Deshpande, M.; Pusate, A.A. Asymptomatic Presentation of Large Cardiac Ball. J Assoc Physicians India 2016, 64, 96–97. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Rather, G. Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology of Cysticercosis: A Study of 30 Cases. J Cytol 2019, 36, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Goyal, S. Cysticercosis: A case of missed diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol 2022, 50, E214–e216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apte, O.; Bhartendu, B.; Panwar, V.K.; Prajapati, T.; Phulware, R.H. Cytomorphology of Renal Hydatid Cyst Mimicking as Simple Renal Cyst. Cytopathology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beigh, A.B.; Darzi, M.M.; Bashir, S.; Kashani, B.; Shah, A.; Shah, S.A. Gross and histopathological alterations associated with cystic echinococcosis in small ruminants. J Parasit Dis 2017, 41, 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, C.; Stoore, C.; Strull, K.; Franco, C.; Corrêa, F.; Jiménez, M.; Hernández, M.; Lorenzatto, K.; Ferreira, H.B.; Galanti, N.; et al. New insights of the local immune response against both fertile and infertile hydatid cysts. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhabria, B.A.; Agarwal, R.; Garg, M.; Gupta, N.; Bal, A.; Dhooria, S.; Sehgal, I.S. A rare cause of airway obstruction: Mediastinal cyst secondarily infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Lung India 2018, 35, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, T.; Arpaci, R.B.; Vayisoğlu, Y.; Serinsöz, E.; Gürsoy, D.; Özgür, A.; Apaydin, D.; Özcan, C. Hydatid Cyst of Parotid Gland: An Unusual Case Diagnosed by Fine Needle Aspiration Biopsy. Turk Patoloji Derg 2017, 33, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlak, E.; Kerget, F.; Demirdal, T.; Şen, P.; Ulaş, A.B.; Öztürk Durmaz, Ş.; Pekok, U.; Ertürk, A.; Akyol, D.; Kepenek Kurt, E.; et al. The Epidemiology, Clinical Manifestations, Radiology, Microbiology, Treatment, and Prognosis of Echinococcosis: Results of NENEHATUN Study. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2021, 21, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gök, H.; Başkurt, O. Giant Primary Intracranial Hydatid Cyst in Child with Hemiparesis. World Neurosurg 2019, 129, 404–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidis, E.T.; Galanis, I.N.; Pavlidis, T.E. Current considerations for the management of liver echinococcosis. World J Gastroenterol 2025, 31, 103973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incekara, F.; Findik, G.; Turk, İ.; Erturk, H.; Aydogdu, K.; Apaydin, S.M.K.; Demiröz, S.M.; Demirag, F. Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Treatment of Coelomic Cysts. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2020, 30, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, C.; Li, J.; Jia, D.; Wang, Y.; Xie, W.; Wang, J. A large pericardial cyst mimicking a unilateral pleural effusion: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023, 102, e33540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeropoulu, S.K.; Schwierz, E.; Meyerhoff, M.; Ratjszczak, R.; Nadler, T.; Raphael, B.L. ULTRASOUND-GUIDED PERCUTANEOUS TREATMENT OF HEPATIC HYDATIDOSIS IN TWO RED-SHANKED DOUC LANGURS (PYGATHRIX NEMAEUS). J Zoo Wildl Med 2023, 54, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peer, S.; Jabbal, H.S.; Singh, P.; M, P.S.; Kakkera, S.; Bhat, P. A case report of successful percutaneous aspiration, injection, and re-aspiration (PAIR) technique for treatment of retrovesical pelvic hydatid cyst. Radiol Case Rep 2023, 18, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauci, C.G.; Jenkins, D.J.; Lightowlers, M.W. Protection against cystic echinococcosis in sheep using an Escherichia coli-expressed recombinant antigen (EG95) as a bacterin. Parasitology 2023, 150, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jazouli, M.; Lightowlers, M.W.; Bamouh, Z.; Gauci, C.G.; Tadlaoui, K.; Ennaji, M.M.; Elharrak, M. Immunological responses and potency of the EG95NC(-) recombinant sheep vaccine against cystic echinococcosis. Parasitol Int 2020, 78, 102149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essolaymany, Z.; Amara, B.; Khacha, A.; El Bouardi, N.; Haloua, M.; Alaoui Lamrani, M.Y.; Boubbou, M.; Serraj, M.; Maâroufi, M.; Alami, B. Hydatid pulmonary embolism underlying cardiac hydatid cysts - A case report. Respir Med Case Rep 2023, 44, 101856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Harsh, V.; Prakash, A.; Sahay, C.B.; Kumar, A. Neglected Case of Primary Intraorbital Hydatid Cyst. Neurol India 2022, 70, 337–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).