Introduction

Fractional flow reserve (FFR) is the most widely used intracoronary physiology index to guide coronary revascularization strategy in the catheterization laboratory. The safety of FFR as a decision-making tool has been documented in studies that mainly involved patients affected by stable coronary artery disease [

1], but has recently also been demonstrated in the context of acute coronary syndromes [

2,

3].

Multiple large randomized trials showed that stenoses with an FFR < 0.80 have a poor prognosis and require treatment by PCI whereas PCI of lesions with FFR > 0.80 can be safely deferred [

4]. The safety of deferring revascularization in FFR-negative lesions stems from the benefit of identifying lesions that are non-flow limiting and with a low risk of triggering acute ischaemic events. However, FFR does not allow precise assessment of plaque morphology and cannot detect atherosclerotic lesions with unstable features, which may identify patients at higher risk of acute coronary events while presenting without flow limitation [

5].

In previous intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) studies, lesion characteristics that were predictive of events associated with non-culprit lesions included a large plaque burden, a small luminal area, and thin-cap fibroatheromas (TFCA) [

6]. In diabetic patients mainly affected by stable coronary artery disease, optical coherence tomography (OCT) allowed to detect unstable plaques with TFCA in 25% of FFR-negative lesions, which were associated with a five-fold higher rate of MACE despite the absence of ischaemia [

7]. Among patients with myocardial infarction and FFR-negative non-culprit lesions, the presence of a high-risk plaque, defined by OCT analysis, was associated with a worse clinical outcome [

8].

Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) is a further imaging modality to identify vulnerable lesions through the automated detection and quantification of lipid content [

9]. In the PROSPECT II study, the combined use of NIRS and intravascular ultrasound, allowed to detect angiographically non-obstructive lesions with a high lipid content and large plaque burden that were at increased risk for future adverse cardiac outcomes [

10].

In the PREVENT trial, treatment of vulnerable plaques, detected by OCT and IVUS-NIRS criteria, with a preventive percutaneous coronary intervention strategy reduced the risk of major cardiovascular events compared to medical therapy [

11].

To aim of this study is to perform an integrated assessment of angiographically intermediate coronary lesions by FFR and IVUS-NIRS and to evaluate the distribution of plaque vulnerability features, assessed by IVUS-NIRS, in functionally significant and non-significant lesions.

Material and Methods

The INTERFERE (NCT02985112) is an observational, prospective, study that was conducted in two italian sites (Misericordia Hospital, Grosseto and University of Ferrara, Ferrara).

Subjects undergoing coronary angiography for stable coronary artery disease, non-ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and unstable angina were eligible for enrollment if they had at least one angiographically borderline stenosis (≥ 40, <70% by Quantitative Coronary Angiography, QCA) with normal antegrade flow (TIMI 3). The index lesion was evaluated by FFR; afterwards, plaque composition and lesion characteristics were evaluated by intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and NIRS. Revascularization of the index lesions was guided by the FFR findings according to current guidelines on myocardial revascularization [

12]: patients with exclusively FFR-positive lesions (i.e. FFR < 0.80) underwent mandatory revascularization. Patients with FFR-negative index lesion (i.e. FFR > 0.80) were treated by guideline-recommended optimal medical therapy.

Patients with hemodynamic instability, ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction, known allergy to antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs, history of previous surgical revascularization, significant left main disease, life expectancy < 1 year, severe renal failure, malignancy, scheduled valve surgery, inability to provide informed consent, known bronchial asthma, age < 18 were excluded.

The IVUS-NIRS system, as used in this study, consists of a 3.2-F rapid exchange catheter, a pullback and rotation device, and a console (InfraReDx, Burlington, Massachusetts). Image acquisition was performed by a motorized catheter pullback at a speed of 0.5 mm/s and 240 rpm in the target vessel, starting distal to the index lesion. The system performed 1,000 chemical measurements per 12.5 mm, in which each measurement interrogated 1 to 2 mm

2 of vessel wall from a depth of approximately 1 mm in the direction from the luminal surface toward the adventitia [

13]. NIRS data generate a chemogram, which is a colour-coded distribution of lipid probability with the x-axis corresponding to the axial vessel position (0·1 mm per pixel) and the y-axis corresponding to the circumferential position (1° per pixel). Low probability of lipid is shown as red and high probability of lipid is shown as yellow [

14]. The lipid core burden index (LCBI) is the fraction of pixels with probability of lipid greater than 0·6 divided by all analysable pixels within the region of interest, multiplied by 1000. MaxLCBI4mm is defined as the maximum LCBI within any 4 mm pullback length across the entire lesion (appendix p 26). LCBI and maxLCBI4mm reported measures range from 0 to 1000, equivalent to 0% to 100% yellow pixels in the region of interest.

Based on the results of the PROSPECT and PROSPECT 2 studies, we considered the following features as markers of vulnerable plaques: a minimal lumen area of less than 4.0 mm² by intravascular ultrasonography; a plaque burden of more than 70% by intravascular ultrasonography; a lipid-rich plaque by near-infrared spectroscopy (defined as maximum lipid core burden index within any 4 mm pullback length [maxLCBI4mm] >325)vi,x. The definition of high-risk plaque required the simultaneous presence of these three criteria.

IVUS and NIRS images were analyzed offline by an independent core laboratory (Euroimaging Srl, Rome). Core laboratory personnel were blinded to all other patient and outcome data.

The occurrence of MACEs (composite of all-cause mortality, non-fatal MI or unplanned revascularization) was also evaluated at long-term follow.

Statistical Analysis

The normal distribution of continuous variables was assessed through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables were presented as means (standard deviation [SD]) or median (interquartile range [IQR]), and comparisons of patient-level variables were conducted using either the Student t-test or the Mann-Whitney test, as deemed appropriate. Categorical variables were summarized by frequency and percentage and compared with Pearson Chi-square or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. A 2-sided P value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The analysis of the major cardiovascular events was performed comparing patients with and without a high-risk plaque. Patients were censored at their last known moment of follow-up. Time-to-event data for the primary end point were presented descriptively using Kaplan-Meier curves, and a log-rank test was used to evaluate whether there was a difference between the groups. Analyses were performed using Prism (GraphPad Software 225 Franklin Street. Fl. 26 Boston, MA 02110).

Results

From march 2014 to december 2019 a total of 57 patients in two Italian study centers were enrolled in the study and 57 lesions were analysed by both FFR and IVUS-NIRS.

Table 1 shows patient demographics and procedural characteristics. Median age was 66 years and 18 % of the patients were females. The majority of patients (>70%) were treated for acute coronary syndromes and only the 28% of them was admitted with a diagnosis of stable coronary disease. A quarter of patients had a previous acute coronary syndrome and a third of them a previous percutaneous coronary revascularization.

Table 2.

Clinical outcome at long-term follow-up. .

Table 2.

Clinical outcome at long-term follow-up. .

| Major cardiovascular events in high-risk and non high-risk lesions: general population |

|---|

| |

Total |

High risk lesions |

Non high-risk lesions |

p-value |

| |

N=57 |

N= 10 |

N= 47 |

|

| All-cause death |

10 (18%) |

2 (20%) |

8 (17%) |

0.82 |

| Myocardial infarction |

1 (2%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (2%) |

0.64 |

| Unplanned revascularization |

2 (4%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (4%) |

0.51 |

Composite end-point:

all-cause death, myocardial infarction, unplanned revascularization |

12 (21%) |

2 (20%) |

10 (21%) |

0.93 |

| Major cardiovascular events in high-risk and non high-risk lesions: patients with negative FFR

|

| |

Total |

High risk lesions |

Non high-risk lesions |

p-value |

| |

N=32 |

N= 7 |

N= 25 |

|

| All-cause death |

6 (19%) |

2 (29%) |

4 (16%) |

0.45 |

| Myocardial infarction |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

|

| Unplanned revascularization |

1 (3%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (4%) |

0.59 |

Composite end-point:

all-cause death, myocardial infarction, unplanned revascularization |

7 (22%) |

2 (29%) |

5 (20%) |

0.63 |

Most of patients were discharged with an indication to dual antiplatelet therapy and optimized lipid-lowering therapy (i.e. maximum tolerated dose) throughout the follow-up period. The index lesion was located in the LAD in almost 70% of cases.

Twenty-five lesions showed a FFR value < 0.80, were treated by PCI and represented the group A: the remaining 32 lesions with a negative FFR (> 0.80) and addressed to medical treatment were labeled as group B.

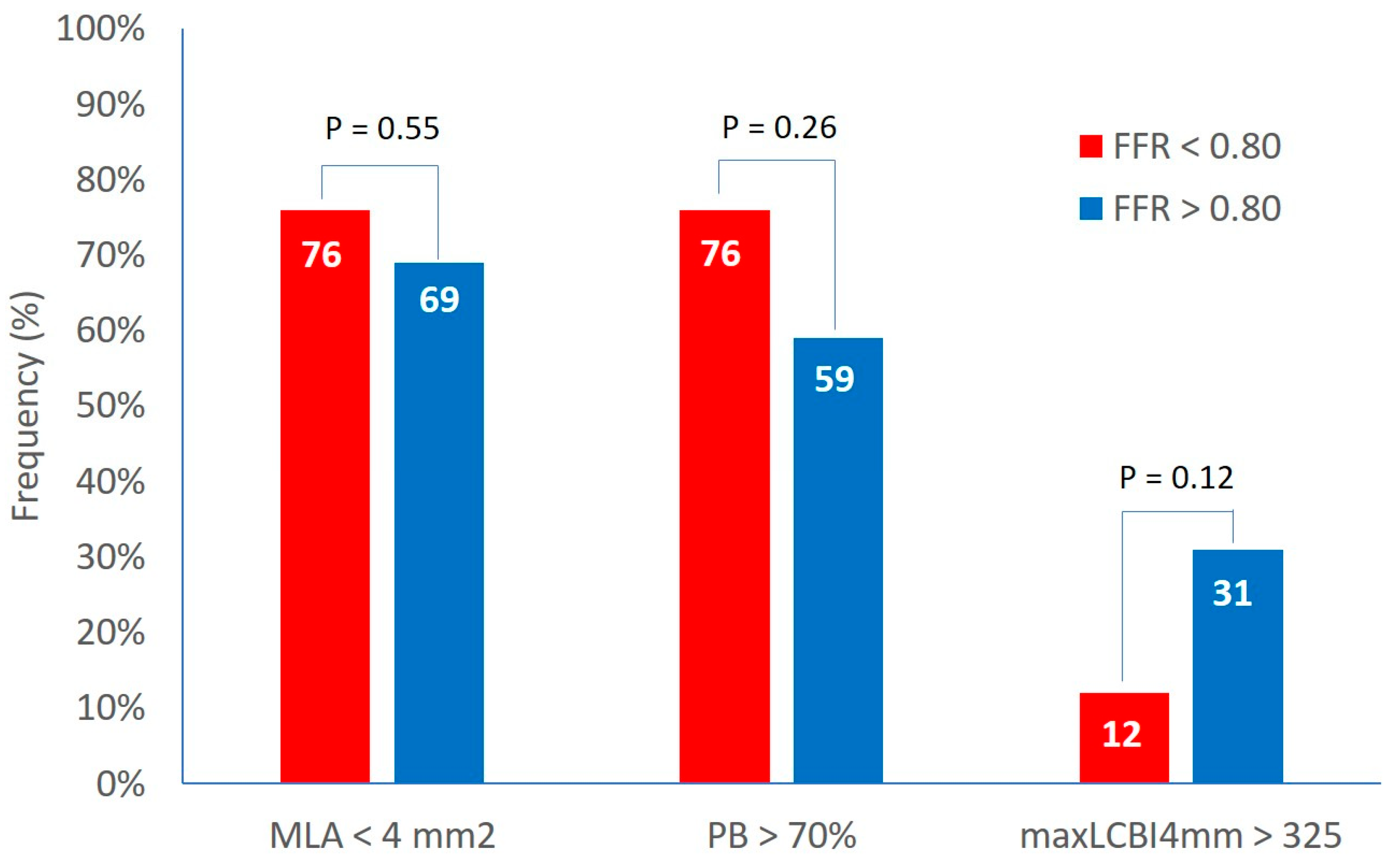

Clinical and demographics characteristics were similar in both groups. The IVUS analysis showed a MLA of 3.6±1.2 mm2 and a plaque burden at the site of MLA of 73.3±7.9 % with no difference between the two groups. The percentage of lesions with MLA < 4 mm2 and with plaque burden > 70% was 72% and 67% respectively with non significant differences between group A and B (

Figure 1).

At the NIRS analysis, the LCBI 4 mm around MLA was 204±160 and the percentage of patients with a LCBI 4 mm around MLA > 325 was 23% with no difference between the two groups (

Figure 1).

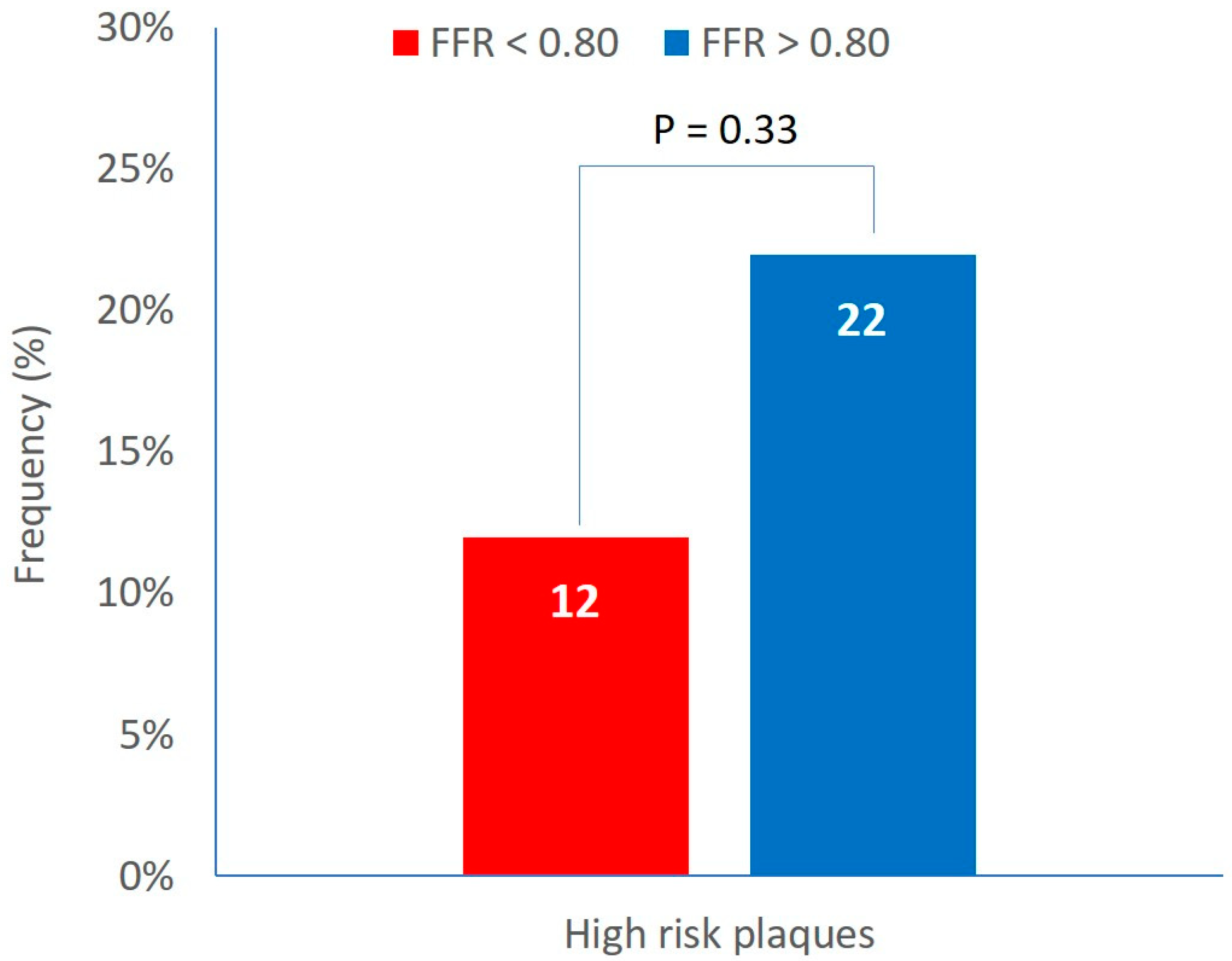

High risk plaques (defined by the simultaneous presence of the three plaque vulnerability features, MLA < 4 mm2, plaque burden > 70% and LCBI 4 mm around MLA > 325) were detected in the 18% of patients. The prevalence of high risk plaques was not different between groups A and B (12% vs 22%, P=0.33) (

Figure 2).

The incidence of MACEs (composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction and unplanned revascularization) was also assessed at a mean follow-up of 2896 ± 57 days in subjects with high-risk and non high-risk lesions. No difference was detected between the two groups in the overall population: in the subgroup of patients with functionally non-significant stenoses, a trend toward an increased risk of events in the high-risk lesion group was detected with no statistically significance difference.

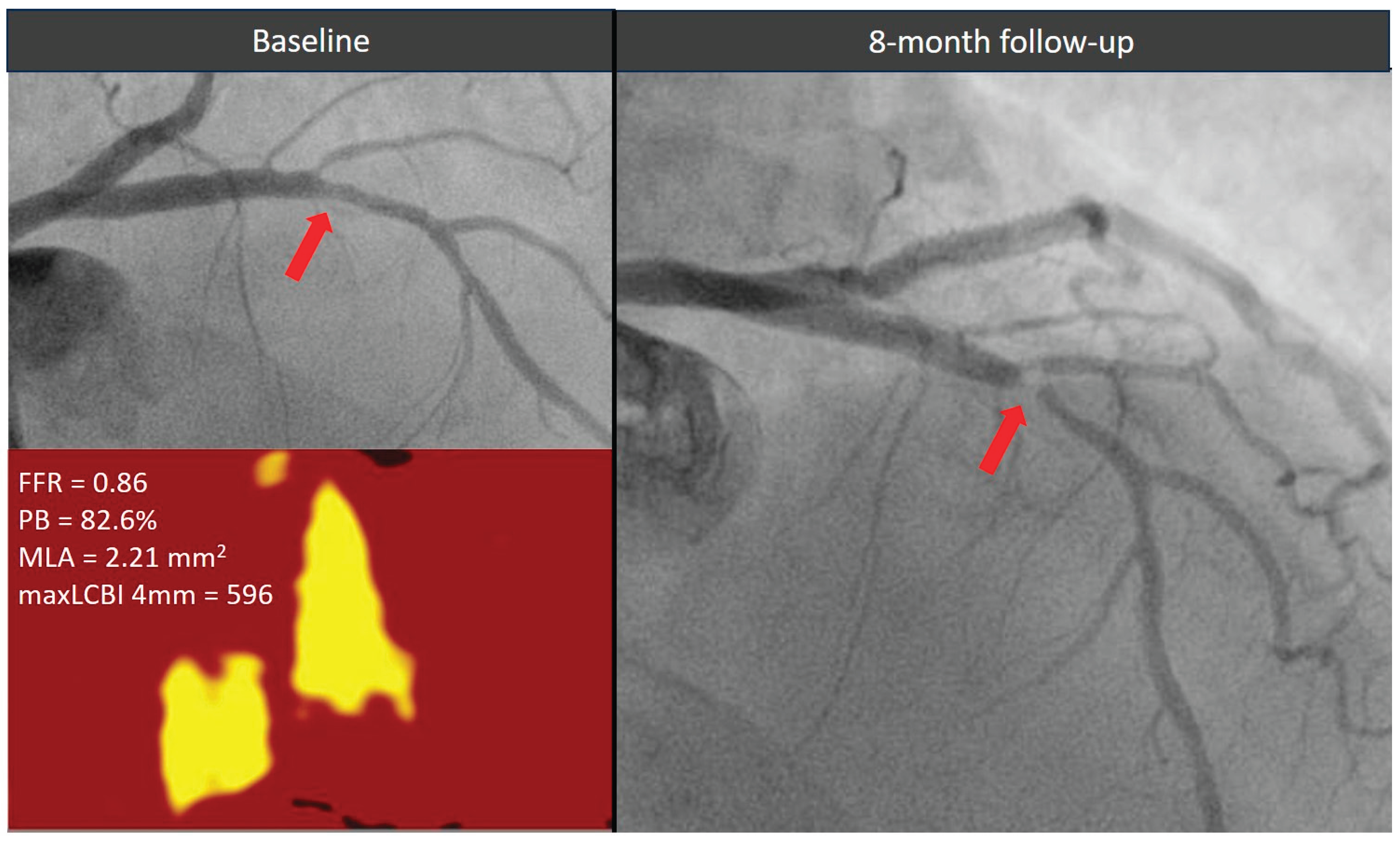

Figure 3.

Evolution of a functionally non-significant proximal left descending artery lesion (red arrow) exhibiting all three high-risk morphological features. The plaque showed a significant stenosis progression causing an acute coronary syndrome within 1 year from the index angiogram. FFR = fractional flow reserve, MaxLCBI4mm = maximum lipid core burden index within any 4 mm segment, MLA = minimal lumen area, PB = plaque burden.

Figure 3.

Evolution of a functionally non-significant proximal left descending artery lesion (red arrow) exhibiting all three high-risk morphological features. The plaque showed a significant stenosis progression causing an acute coronary syndrome within 1 year from the index angiogram. FFR = fractional flow reserve, MaxLCBI4mm = maximum lipid core burden index within any 4 mm segment, MLA = minimal lumen area, PB = plaque burden.

Discussion

The major findings of this study are as follows: 1) plaque vulnerability criteria are equally distributed between functionally significant and non-significant coronary lesions, 2) the prevalence of high-risk plaques—defined by the simultaneous presence of three vulnerability features (MLA < 4 mm², PB > 70%, and maxLCBI₄mm > 325) does not differ significantly between functionally significant and non-significant lesions, 3) twenty-two percent of FFR-negative lesions, managed with pharmacological treatment, are characterized by the presence of high-risk plaques.

Our study provides new insights into the relationship between plaque composition and FFR values, clearly demonstrating that non-flow-limiting lesions can exhibit morphological features of plaque vulnerability, similar to those observed in functionally significant stenoses, which are typically treated invasively.

Similar results were observed in the COMBINE OCT–FFR trialvii. In that study, OCT-detected vulnerable plaques were present in up to 25% of angiographically intermediate, FFR-negative lesions and were responsible for over 80% of future adverse events despite optimal medical therapy. Conversely, the remaining 75% of FFR-negative lesions without vulnerability features were associated with a low risk of future events.The percentage of high-risk, non-significant stenoses in the COMBINE OCT–FFR trial (25%) closely aligns with our findings (22%). The slight discrepancy may be explained by differences in study populations: the COMBINE OCT–FFR cohort consisted exclusively of diabetic patients.

A higher prevalence of high-risk plaques was reported in the PECTUS trial (34%), which enrolled only patients with acute coronary syndromes (STEMI and NSTEMI) viii. In such populations, the detection of vulnerable plaques in non-culprit lesions is expected to be more frequent.

In the more recent PREVENT trial, the prevalence of high-risk plaques among FFR-negative lesions was substantially higher (45%)xi. This may be attributed to the use of less stringent criteria for plaque vulnerability, defined by the presence of only two features. Additionally, the adoption of a lower maxLCBI cutoff (315) may have contributed to the higher observed prevalence.

The optimal treatment strategy for functionally non-significant lesions with high-risk morphological features remains a topic of ongoing debate. In the PREVENT study, prophylactic percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of non-flow-limiting, vulnerable plaques was associated with a lower incidence of major adverse cardiac events during long-term follow-up compared with pharmacological therapy

xi. However, medical therapy in the study was largely suboptimal, with limited use of PCSK9 inhibitors and relatively high LDL-cholesterol targets (60 to 85 mg/dL). Previous studies have demonstrated that adding PCSK9 inhibitors to high-intensity statin therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction leads to favorable effects on plaque regression and stabilization, including reductions in lipid burden and increases in fibrous cap thickness [

15,

16].

Based on current evidence, the actual impact of functionally non-significant lesions with high-risk morphological features on cardiovascular outcomes remains uncertain and the optimal treatment strategy for such lesions should be evaluated in large-scale randomized trials.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the small sample size may have introduced bias. Second, IVUS-NIRS analysis has not been performed in all three coronary vessels: therefore, we might have missed high-risk lesions. However, such targeted evaluation might be more feasible in clinical practice. Third, we did not perform FFR pullbacks, which may further help distinguish between focal and diffuse disease patterns. Fourth, operators were not blinded to IVUS-NIRS findings, which could potentially have led to altered decision-making. However, the IVUS-NIRS analyses were performed post hoc by an independent core laboratory.

Conclusions

In a population of patients predominantly affected by acute coronary syndrome, plaque vulnerability features are similarly distributed between functionally significant and non-significant coronary lesions, with no significant difference in the prevalence of high-risk plaques between the two groups. Notably, more than one-fifth of FFR-negative lesions managed conservatively exhibit high-risk characteristics; however, further studies are required to determine whether these lesions would benefit from interventional treatment or a more intensive pharmacological strategy.

References

- De Bruyne B, Pijls NHJ, Kalesan B, Barbato E, Tonino PAL, Piroth Z, Jagic N, Mo¨bius-Winkler S, Rioufol G, Witt N, Kala P, MacCarthy P, Engstro¨m T, Oldroyd KG, Mavromatis K, Manoharan G, Verlee P, Frobert O, Curzen N, Johnson JB, Ju¨ni P, Fearon WF; FAME 2 Trial Investigators. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI versus medical therapy in stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2012;367:991–1001.

- Lee JM, Kim HK, Park KH et al. FRAME-AMI Investigators. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography-guided strategy in acute myocardial infarction with multivessel disease: a randomized trial. European Heart Journal (2023) 44, 473–484.

- Biscaglia S, Guiducci V, Escaned J et al. FIRE Trial Investigators. Complete or Culprit-Only PCI in Older Patients with Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med 2023 Sep 7;389(10):889-898.

- Zimmermann FM, Omerovic E, Fournier S, Kelbæk H, Johnson NP, Rothenbühler M, Xaplanteris P, Abdel-Wahab M, Barbato E, Høfsten DE, Tonino PAL, Boxma-de Klerk BM, Fearon WF, Køber L, Smits PC, De Bruyne B, Pijls NHJ, Jüni P, Engstrøm T. Fractional flow reserve-guided percutaneous coronary intervention vs. medical therapy for patients with stable coronary lesions: meta-analysis of individual patient data. Eur Heart J 2019 Jan 7;40(2):180-186.

- Prati F, Romagnoli E, Gatto L, La Manna A, Burzotta F, Ozaki Y, Marco V, Boi A, Fineschi M, Fabbiocchi F, Taglieri N, Niccoli G, Trani C, Versaci F, Calligaris G, Ruscica G, Di Giorgio A, Vergallo R, Albertucci M, Biondi-Zoccai G, Tamburino C, Crea F, Alfonso F, Arbustini E. Relationship Relationship between coronary plaque morphology of the left anterior descending artery and 12 months clinical outcome: the CLIMA study. Eur Heart J. 3: 2020 Jan 14;41(3):383-391.

- Stone GW, Maehara A, Lansky AJ, de Bruyne B, Cristea E, Mintz GS, Mehran R, McPherson J, Farhat N, Marso SP, Parise H, Templin B, White R, Zhang Z, Serruys PW; PROSPECT Investigators. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 20;364(3):226-35. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2011 Nov 24;365(21):2040. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedhi E, Berta B, Roleder T, Hermanides RS, Fabris E, IJsselmuiden AJJ, Kauer F, Alfonso F, von Birgelen C, Escaned J, Camaro C, Kennedy MW, Pereira B, Magro M, Nef H, Reith S, Al Nooryani A, Rivero F, Malinowski K, De Luca G, Garcia Garcia H, Granada JF, Wojakowski W. Thin-cap fibroatheroma predicts clinical events in diabetic patients with normal fractional flow reserve: the COMBINE OCT-FFR trial. Eur Heart J. 2021 Dec 1;42(45):4671-4679.

- Mol JQ, Volleberg RHJA, Belkacemi A, Hermanides RS, Meuwissen M, Protopopov AV, Laanmets P, Krestyaninov OV, Dennert R, Oemrawsingh RM, van Kuijk JP, Arkenbout K, van der Heijden DJ, Rasoul S, Lipsic E, Rodwell L, Camaro C, Damman P, Roleder T, Kedhi E, van Leeuwen MAH, van Geuns RM, van Royen N. Fractional Flow Reserve-Negative High-Risk Plaques and Clinical Outcomes After Myocardial Infarction. JAMA Cardiol. 2023 Nov 1;8(11):1013-1021.

- Waxman S, Dixon SR, L’Allier P, Moses JW, Petersen JL, Cutlip D, Tardif JC, Nesto RW, Muller JE, Hendricks MJ, Sum ST, Gardner CM, Goldstein JA, Stone GW, Krucoff MW. In vivo validation of a catheter-based near-infrared spectroscopy system for detection of lipid core coronary plaques: initial results of the SPECTACL study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009 Jul;2(7):858-68.

- Erlinge D, Maehara A, Ben-Yehuda O, Bøtker HE, Maeng M, Kjøller-Hansen L, Engstrøm T, Matsumura M, Crowley A, Dressler O, Mintz GS, Fröbert O, Persson J, Wiseth R, Larsen AI, Okkels Jensen L, Nordrehaug JE, Bleie Ø, Omerovic E, Held C, James SK, Ali ZA, Muller JE, Stone GW; PROSPECT II Investigators. Identification of vulnerable plaques and patients by intracoronary near-infrared spectroscopy and ultrasound (PROSPECT II): a prospective natural history study. Lancet. 2021 Mar 13;397(10278):985-995.

- Park SJ, Ahn JM, Kang DY, Yun SC, Ahn YK, Kim WJ, Nam CW, Jeong JO, Chae IH, Shiomi H, Kao HL, Hahn JY, Her SH, Lee BK, Ahn TH, Chang KY, Chae JK, Smyth D, Mintz GS, Stone GW, Park DW; PREVENT Investigators. Preventive percutaneous coronary intervention versus optimal medical therapy alone for the treatment of vulnerable atherosclerotic coronary plaques (PREVENT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2024 Apr 4:S0140-6736(24)00413-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Authors/Task Force members; Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Jüni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014 Oct 1;35(37):2541-619. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waxman S, Dixon SR, L’Allier P, Moses JW, Petersen JL, Cutlip D, Tardif JC, Nesto RW, Muller JE, Hendricks MJ, Sum ST, Gardner CM, Goldstein JA, Stone GW, Krucoff MW. In vivo validation of a catheter-based near-infrared spectroscopy system for detection of lipid core coronary plaques: initial results of the SPECTACL study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009 Jul;2(7):858-68. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner CM, Tan H, Hull EL, Lisauskas JB, Sum ST, Meese TM, Jiang C, Madden SP, Caplan JD, Burke AP, Virmani R, Goldstein J, Muller JE. Detection of lipid core coronary plaques in autopsy specimens with a novel catheter-based near-infrared spectroscopy system. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008 Sep;1(5):638-48. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Räber L, Ueki Y, Otsuka T, Losdat S, Häner JD, Lonborg J, Fahrni G, Iglesias JF, van Geuns RJ, Ondracek AS, Radu Juul Jensen MD, Zanchin C, Stortecky S, Spirk D, Siontis GCM, Saleh L, Matter CM, Daemen J, Mach F, Heg D, Windecker S, Engstrøm T, Lang IM, Koskinas KC; PACMAN-AMI collaborators. Effect of Alirocumab Added to High-Intensity Statin Therapy on Coronary Atherosclerosis in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction: The PACMAN-AMI Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2022 May 10;327(18):1771-1781. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholls SJ, Kataoka Y, Nissen SE, Prati F, Windecker S, Puri R, Hucko T, Aradi D, Herrman JR, Hermanides RS, Wang B, Wang H, Butters J, Di Giovanni G, Jones S, Pompili G, Psaltis PJ. Effect of Evolocumab on Coronary Plaque Phenotype and Burden in Statin-Treated Patients Following Myocardial Infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022 Jul;15(7):1308-1321. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).