1. Introduction

Precise evaluation of myocardial ischemia is crucial in the management of coronary artery disease (CAD) for making informed decisions about coronary revascularization [

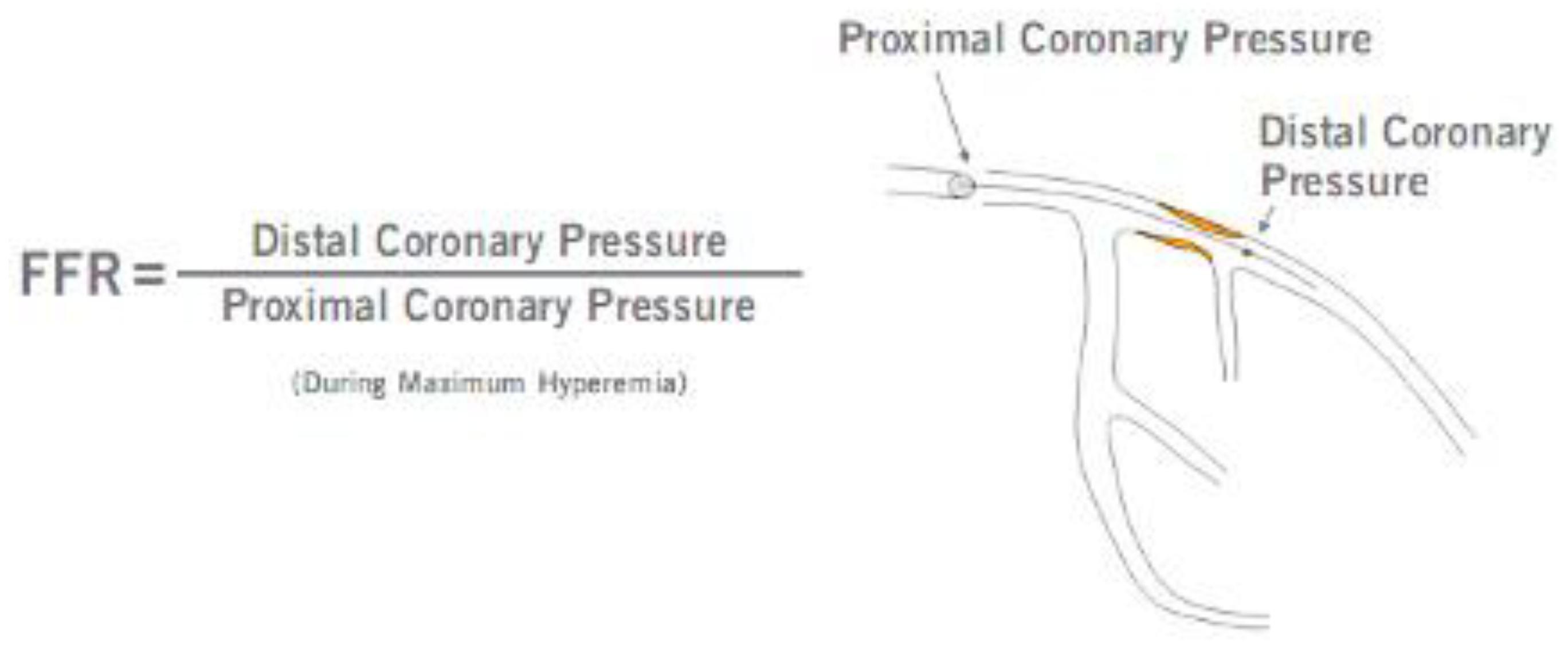

1]. Fractional flow reserve (FFR) is a pressure-derived estimate of coronary flow impairment and one of the most established invasive physiological tests in interventional cardiology. It is defined as the ratio between the mean hyperemic coronary artery pressure distal to the lesion and mean pressure in the aorta. FFR is an invasive index of hemodynamic significance of stenosis severity with a diagnostic accuracy similar to myocardial perfusion scintigraphy [

2]. European guidelines recommend performing fractional flow reserve (FFR) measurements prior to revascularization, particularly when previous ischemia testing is inconclusive or absent [

3]. However, despite the growing preference for physiologically guided revascularization, there remains a significant gap between guideline recommendations and the actual clinical use of functional assessment of the lesions [

4,

5].

The hemodynamic significance, as defined by an FFR ≤0.80, shows a weak correlation with the visually assessed diameter of the stenosis. In the FAME trial (Fractional Flow Reserve versus Angiography for Guidance of PCI in Patients with Multivessel Coronary Artery Disease), only 35% of stenoses assessed by invasive quantitative coronary angiography (CA) in the 50-70% range were hemodynamically significant, and among stenoses in the 71-90% range, 20% were not significant. Only a stenosis diameter estimated at >90% was found to be hemodynamically significant with a high accuracy of 96% [

6]. CA is the current gold-standard method of CAD assessment, but it fails to adequately determine lesion significance because lumen narrowing is just one of many variables influencing coronary flow limitation. Other critical factors that are not easily quantifiable by CA include lesion length, collateral flow, and the amount and viability of the myocardium supplied downstream [

7,

8]. Several studies have shown that FFR-based evaluation at the time of CA led to the reclassification of revascularization strategies (PCI, coronary artery bypass grafting, or medical treatment) in a significant proportion of patients with intermediate-grade lesions (>40% of patients were reclassified) [

9,

10,

11]. However, the impact of FFR on determining revascularization tactics may be of greater interest for patients with multivessel CAD, giving us the opportunity to minimally intervene on functionally significant lesions and safely defer insignificant ones [

12].

Unlike FFR, which is an objective method for assessing lesions capable of inducing ischemia, CA is a subjective method for evaluating the degree of arterial lumen stenosis, dependent on the observer. The inter-observer agreement in visually guided therapeutic decision-making is variable [

13], and not always confirmed by the functional significance of coronary lesions [

14]. Therefore, we aimed to determine the variability in visual assessment of CAD and the impact of FFR on the clinical decision making. Angiographically guided therapeutic decisions were largely concordant with FFR results in our study. However, in 12.4% of cases, FFR impacted the treatment strategy, both by indicating PCI for hemodynamically significant lesions (8.9%) and by deferring PCI for non-significant lesions (15%).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

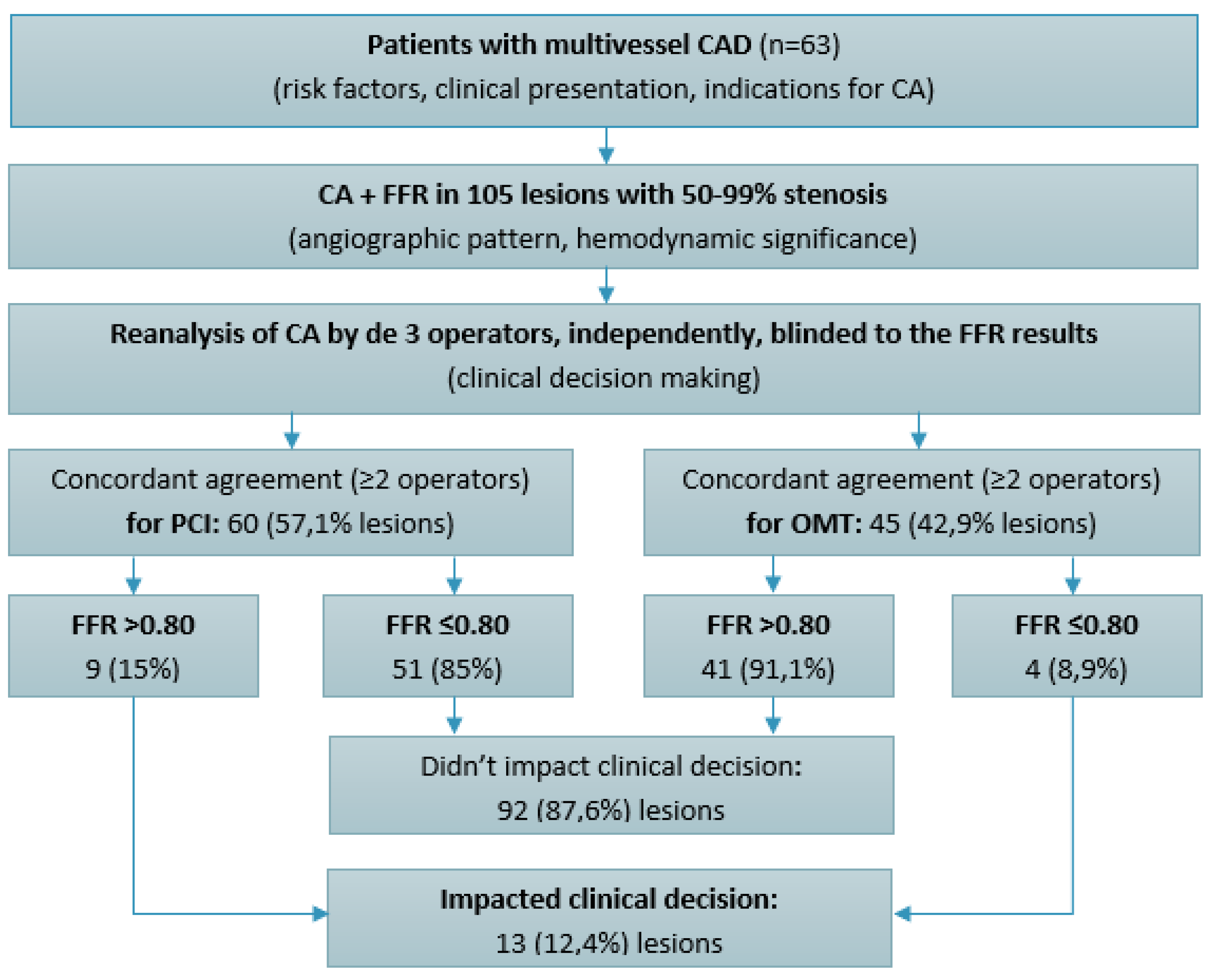

This was a retrospective observational study that included 63 patients with CAD assessed by CA, who underwent at the same time functional evaluation by FFR of 105 lesions (50-99% artery lumen stenosis) in 2023, in the Institute of Cardiology, Chisinau, Republic of Moldova. Patients were assessed for age, sex, traditional risk factors, clinical status at presentation (stable angina, unstable angina, or NSTEMI), clinical and paraclinical data serving as indications for CA (anginal symptoms, dyspnea, exercise test, prior myocardial infarction, low left ventricular ejection fraction). CA was performed using GE Innova IGS angiography machines, following standard protocol. The angiographic characteristics of CAD were assessed: number of diseased vessels, the location and severity of stenoses. Thus, inclusion criteria for the study group were patients with CAD, defined as 50-99% lumen narrowing, as assessed by CA, which were subsequently evaluated by FFR measurement (

Figure 1). Patients with STEMI, left main CAD and those with chronic total occlusions were excluded from this study.

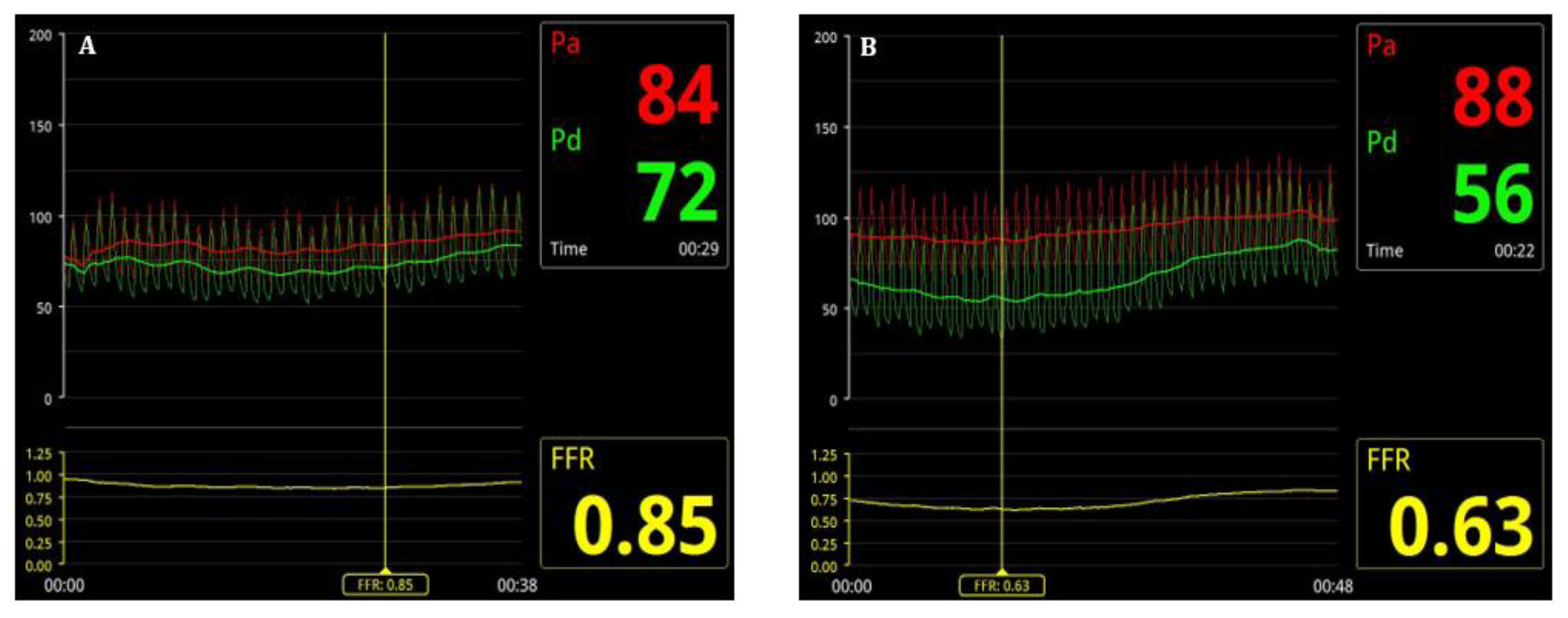

2.2. Fractional Flow Reserve

FFR assessment was performed for all 50-99% stenoses assessed by the primary operator at the time of CA. After intravenous administration of heparin (70 IU/kg), a 0.014” intracoronary pressure wire, 175 cm (PressureWire X, Abbott Medical, Minneapolis, USA) was advanced distal to the stenosis (

Figure 2). After intracoronary administration of 100-200 mcg of isosorbide dinitrate (according to hemodynamics), reactive hyperemia was induced by intravenous adenosine (140–180 µg/kg/min) administration [

15]. An FFR value of ≤0.80 was used as the cutoff to indicate functional significance of CAD [

16]. Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was performed for lesions with an FFR ≤0.80, while lesions with an FFR >0.80 were managed with optimal medical therapy (OMT), in accordance with current guideline recommendations [

3]. If a patient had two or more functionally significant lesions in two or more arteries, staged PCI was preferred, with an interval of 2-4 weeks between the initial procedure and subsequent intervention. PCI was performed using standard percutaneous techniques, either via radial, brachial, or femoral approach.

2.3. Visual Assessment Variability

Each CA was reanalyzed by three experienced interventional cardiologists (with a volume of >300 PCIs performed annually), independently of each other, to determine the angiographic severity of lesions and the need for revascularization based on visual assessment, clinical presentation, and blinded to FFR values. Concordant agreement was considered when at least two interventional cardiologists made the same decision - to treat or not treat a lesion. Complete agreement, when all three interventional cardiologists had the same treatment decision, was also assessed. These results were matched with FFR results to reveal were it had an impact to change clinical decision-making.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 16. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation. The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

The mean age of the study population of 63 patients was 63,55 years (range 34 to 78 years), with 48 (76,2%) males and 15 (23,8%) females (

Table 1). The most prevalent risk factors in this study group were: hypertension – 60 patients (95,2%), dyslipidemia – 54 patients (85,7%), type 2 diabetes mellitus – 40 patients (63,5%), family history of cardiovascular disease – 11 patients (17,5%), and smoking 9 patients (14,3%). In total, there were identified 105 lesions of 50-99% stenosis in 63 patients, which were evaluated by FFR, averaging 1,67 lesions per patient.

Clinical presentation was diverse, including stable angina in 39 patients (61,9%), unstable angina in 20 patients (31,7%), and NSTEMI in 4 patients (6,4%). The indications for CA were predominantly the presence of typical angina pectoris: 34 patients (53,9%) and prior myocardial infarction 16 patients (25,4%). Most patients - 56 (88,9%) who underwent CA did not have exercise testing within the 90-day pre-procedural period, and only 7 (11,1%) of them had a positive exercise test for documenting ischemia. In 92% of cases, coronary angiography was performed via radial access, which implies minimal local complications at the puncture site.

3.2. Lesion Characteristics

In terms of angiographic characteristics, 33 (52,4%) patients in the study group had multivessel CAD (two- or three- vessel disease), and the majority of lesions were located in the left anterior descending artery (LAD) - 53 (50,5%) (

Table 2). The primary operator visually assessed 58 (55,2%) of lesions as being severe and 47 (44,8%) of lesions as being moderate. Nonsignificant FFR values (>0.8) were found in 50 of the lesions (47,6%), which did not undergo PCI, while significant FFR values (≤0.8) were found in 55 of the lesions (52,4%), which underwent PCI (

Figure 3). Interestingly to mention that 21 of the hemodynamic significant lesions (38.2%) were find in patients presented with acute coronary syndrome (unstable angina or NSTEMI).

Lesions located in the LAD showed hemodynamic significance (FFR ≤0.8) in 25 (47,2%) of cases, those in the RCA – in 15 (53.6%) of cases, and those in the LCx – in 15 (62.5%) of cases. Moderate stenoses (50-74%) were hemodynamic significant (FFR ≤0.8) in 8 (17,1%) of cases, and the majority of severe stenoses (75-99%) were hemodynamically significant – in 47 (81,0%) of cases.

3.3. Clinical Decision Making

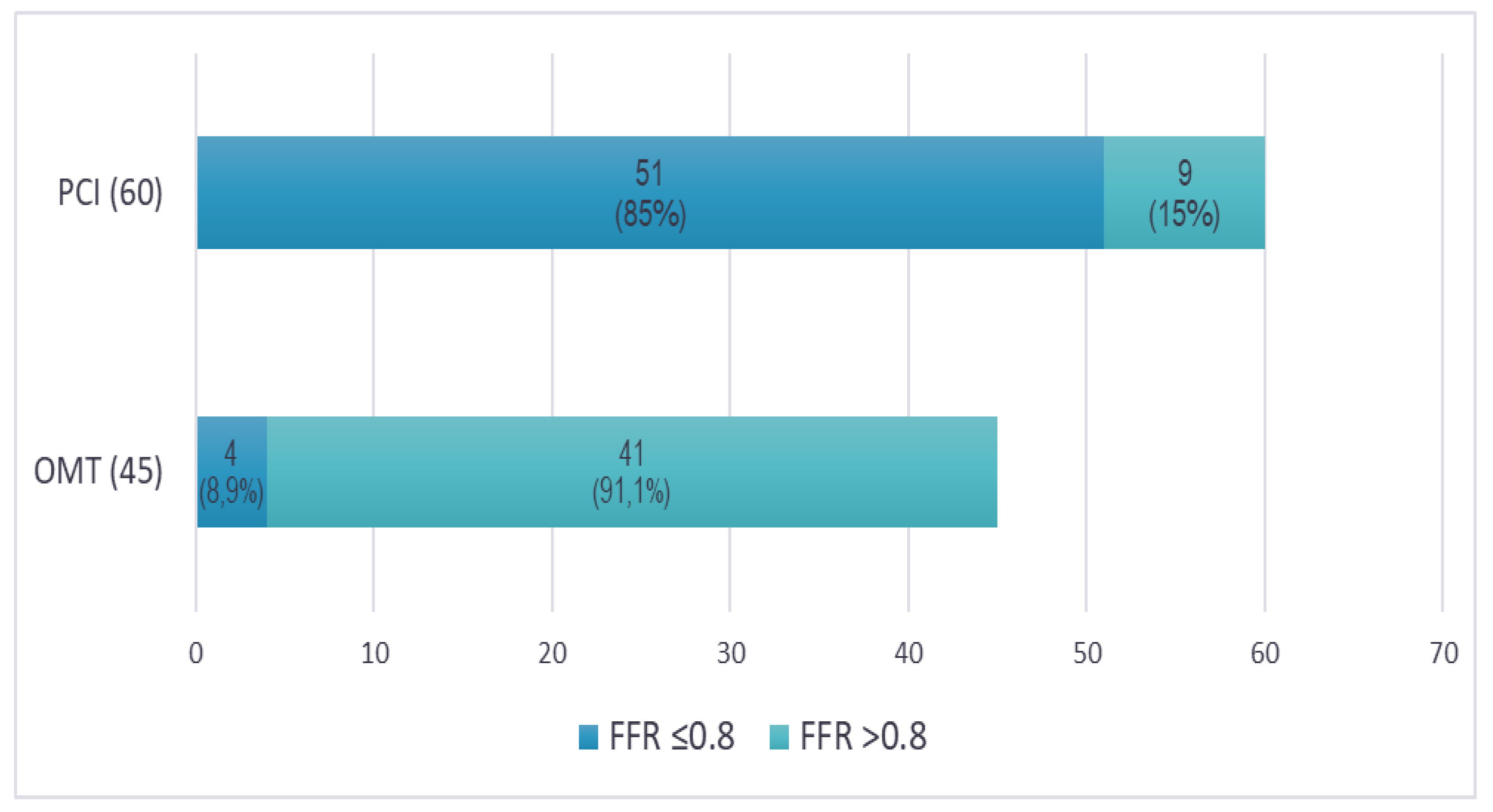

Upon re-evaluating the angiographic images, three experienced interventional cardiologists (each performing over 300 PCIs annually) independently reviewed the cases, blinded to FFR results. Concordant agreement (at least two out of three cardiologists making the same decision) was reached to proceed with PCI for 60 lesions (57.1%) based on angiographic assessment and clinical presentation (

Figure 4). Interestingly, 9 of these lesions (15%) had FFR values that were functionally insignificant. Conversely, there was concordant agreement to defer PCI in favor of OMT for 45 lesions (42.9%). However, 4 of these lesions (8.9%) had FFR values that were functionally significant and required PCI. As a result, FFR had an impact to change revascularization decision in 13 lesions (12.4%), both indicating PCI for 4 functionally significant lesions, and deferring 9 functionally non-significant lesions for OMT. Notably, complete agreement (all three cardiologists making the same decision to either perform PCI or defer to OMT) was achieved in only 82 lesions (78.1%).

4. Discussion

The current study evaluates the impact of FFR on revascularization decisions for atherosclerotic lesions with 50-99% stenosis in a group of 63 patients with CAD. The majority of patients with CAD are men, typically over the age of 60, with other traditional risk factors such as hypertension and dyslipidemia [

17,

18]. Most often, the indication for CA is driven by typical angina symptoms, and rarely have these patients undergone non-invasive stress testing to document inducible ischemia. On CA this population has predominantly multivessel disease and most frequently lesions involve the LAD. More than half of these lesions are functionally significant and require revascularization via PCI.

Despite the demonstrated benefits of FFR, less than 10% of coronary procedures utilize intracoronary imaging or FFR to guide patient management [

19,

20]. This is due to various practical limitations related to FFR measurement, such as the additional time and costs associated with using a coronary guidewire equipped with a distal pressure sensor and the need for intracoronary or intravenous adenosine administration. Consequently, PCI is sometimes performed on functionally insignificant lesions, where the intervention could be safely deferred in favor of optimal medical therapy [

21].

The study cohort included a variety of clinical presentations, ranging from stable angina to unstable angina and NSTEMI. Previously, the diagnostic performance of FFR in patients with NSTEMI had been evaluated by others [

22,

23]. In the present study, one of the key findings was that significant FFR (≤0.8) was found in 55 (52.4%) lesions, and in more than one-third of them—21 (38.2%), patients presented with acute coronary syndrome (unstable angina or NSTEMI).

Another important finding from this study was that moderate stenosis, angiographically assessed at 50-79%, revealed hemodynamic significance (FFR ≤0.8) in 17% of cases, while the majority of severe stenosis, assessed at 75-99%, were hemodynamically significant - in 81% of cases. However, 19% of lesions with severe stenosis were found to be functionally non-significant, allowing the FFR-guided strategy to prevent unnecessary revascularization in these cases. The difference in visual and hemodynamic guidance was found in other studies, where it had reduced the need for stenting and flattened the added cost of the pressure wire [

24,

25].

Discrepancies between the visually and functionally estimated significance of intermediate stenoses are frequently encountered and can change the clinical decision-making in more than one third of cases, as reported in other studies [

26]. In the present study, there was concordant agreement (≥2 out of 3 interventional cardiologists) to revascularize 60 (57.1%) of the lesions based on the angiographic appearance, while 9 (15%) of these were functionally non-significant according to FFR measurements. On the other hand, a concordant agreement to defer PCI in favor of OMT was reached for 45 (42.9%) of the lesions, while 4 (8.9%) of these were functionally significant. Thus, FFR assessment of lesions has a significant clinical impact, leading to a change in treatment strategy in 13 lesions (12.4%).

Despite its well-established clinical value, the routine use of FFR in daily practice is not consistently cost-effective [

24], making it important to identify the group of lesions where FFR can yield truly significant results. The clinical and cost implications of such a shift in the decision-making process, especially in resource-limited areas like the Republic of Moldova, require further evaluation in larger studies. In reality, many factors can influence the physician’s decision to perform revascularization, including patient preference, treatment compliance, lesion complexity, the feasibility of achieving complete revascularization, and additional costs, all of which can lead to a decision that may be discordant with the FFR outcome.

5. Conclusions

Angiographically guided decision making on revascularization of CAD is largely aligned with FFR results. However, in 12.4% of cases, FFR influenced a change in treatment strategy, leading to the indication of PCI for hemodynamically significant lesions (8.9%) and the deferral of PCI for non-significant ones (15%).

Author Contributions

Involved in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization and writing the original draft: MD, PhD candidate Andrei Grib. Ensure project administration and resources, as well as writing – reviewing & editing: MD, PhD Marcel Abras. Involved in data curation and software: MD, PhD Artiom Surev. Substantial contributions to conceptualization, methodology and supervision: Prof. Dr. Livi Grib. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This is an investigator-driven study supported by the State University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Nicolae Testemitanu”, Chisinau, Republic of Moldova.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Research at USMF "Nicolae Testemitanu", nr. 00274RA from 12.09.2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The current paper was academically supported by the State University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Nicolae Testemitanu”, Chisinau, Republic of Moldova and received logistical support from the Institute of Cardiology, Chisinau, Republic of Moldova.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xaplanteris, P.; Fournier, S.; Pijls, N.H.J.; Fearon, W.F.; Barbato, E.; Tonino, P.A.L.; Engstrøm, T.; Kääb, S.; Dambrink, J.-H.; Rioufol, G.; et al. Five-Year Outcomes with PCI Guided by Fractional Flow Reserve. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 379, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiono, Y.; Matsuo, H.; Fujita, H.; Tanaka, N.; Ogasawara, Y.; Kawamura, I.; Katayama, Y.; Matsuo, A.; Kawase, Y.; Kakuta, T.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Diastolic Fractional Flow Reserve for Functional Evaluation of Coronary Stenosis: DIASTOLE Study. JACC: Asia 2021, 1, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, F.J.; Sousa-Uva, M.; Ahlsson, A.; Alfonso, F.; Banning, A.P.; Benedetto, U.; Byrne, R.A.; Collet, J.P.; Falk, V.; Head, S.J.; et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on Myocardial Revascularization. Eur Heart J 2019, 40, 87–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, S.; Westra, J.; Adjedj, J.; Ding, D.; Liang, F.; Xu, B.; Holm, N.R.; Reiber, J.H.C.; Wijns, W. Fractional Flow Reserve in Clinical Practice: From Wire-Based Invasive Measurement to Image-Based Computation. Eur Heart J 2020, 41, 3271–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruyne, B.; McFetridge, K.; Tóth, G. Angiography and Fractional Flow Reserve in Daily Practice: Why Not (Finally) Use the Right Tools for Decision-Making? Eur Heart J 2013, 34, 1321–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nunen, L.X.; Zimmermann, F.M.; Tonino, P.A.L.; Barbato, E.; Baumbach, A.; Engstrøm, T.; Klauss, V.; Maccarthy, P.A.; Manoharan, G.; Oldroyd, K.G.; et al. Fractional Flow Reserve versus Angiography for Guidance of PCI in Patients with Multivessel Coronary Artery Disease (FAME): 5-Year Follow-up of a Randomised Controlled Trial. The Lancet 2015, 386, 1853–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narula, J. Coronary Anatomy, Physiology, and Beyond…. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2023, 16, 1465–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, K.L.; Johnson, N.P.; Bateman, T.M.; Beanlands, R.S.; Bengel, F.M.; Bober, R.; Camici, P.G.; Cerqueira, M.D.; Chow, B.J.W.; Di Carli, M.F.; et al. Anatomic Versus Physiologic Assessment of Coronary Artery Disease: Role of Coronary Flow Reserve, Fractional Flow Reserve, and Positron Emission Tomography Imaging in Revascularization Decision-Making. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013, 62, 1639–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillmore, T.; Jung, R.G.; Moreland, R.; Di Santo, P.; Stotts, C.; Makwana, D.; Abdel-Razek, O.; Ahmed, Z.; Chung, K.; Parlow, S.; et al. Impact of Intracoronary Assessments on Revascularization Decisions: A Contemporary Evaluation. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions 2022, 100, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Belle, E.; Cosenza, A.; Baptista, S.B.; Vincent, F.; Henderson, J.; Santos, L.; Ramos, R.; Pouillot, C.; Calé, R.; Cuisset, T.; et al. Usefulness of Routine Fractional Flow Reserve for Clinical Management of Coronary Artery Disease in Patients With Diabetes. JAMA Cardiol 2020, 5, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escaned, J.; Berry, C.; De Bruyne, B.; Shabbir, A.; Collet, C.; Lee, J.M.; Appelman, Y.; Barbato, E.; Biscaglia, S.; Buszman, P.P.; et al. Applied Coronary Physiology for Planning and Guidance of Percutaneous Coronary Interventions. A Clinical Consensus Statement from the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) of the European Society of Cardiology. EuroIntervention 2023, 19, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Zimmermann, F.M.; Otsuki, H.; El Farissi, M.; Oldroyd, K.G.; Wendler, O.; Reardon, M.J.; Woo, Y.J.; Yeung, A.C.; et al. Outcomes Based on Angiographic vs Functional Significance of Complex 3-Vessel Coronary Disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2023, 16, 2112–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basman, C.; Levine, E.; Tejpal, A.; Thampi, S.; Rashid, U.; Barry, R.; Stoffels, G.; Kliger, C.A.; Coplan, N.; Patel, N.; et al. Variability and Reproducibility of the SYNTAX Score for Triple-Vessel Disease. Cardiovascular Revascularization Medicine 2022, 37, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.-J.; Kang, S.-J.; Ahn, J.-M.; Shim, E.B.; Kim, Y.-T.; Yun, S.-C.; Song, H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kim, W.-J.; Park, D.-W.; et al. Visual-Functional Mismatch Between Coronary Angiography and Fractional Flow Reserve. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2012, 5, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth, G.G.; Johnson, N.P.; Jeremias, A.; Pellicano, M.; Vranckx, P.; Fearon, W.F.; Barbato, E.; Kern, M.J.; Pijls, N.H.J.; De Bruyne, B. Standardization of Fractional Flow Reserve Measurements. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016, 68, 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruyne, B.; Pijls, N.H.J.; Kalesan, B.; Barbato, E.; Tonino, P.A.L.; Piroth, Z.; Jagic, N.; Möbius-Winkler, S.; Rioufol, G.; Witt, N.; et al. Fractional Flow Reserve–Guided PCI versus Medical Therapy in Stable Coronary Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2012, 367, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, C.W.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Alonso, A.; Beaton, A.Z.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Boehme, A.K.; Buxton, A.E.; Carson, A.P.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 145, E153–E639. [Google Scholar]

- Abras, M.; Grib, A.; Surev, A.; Damascan, S.; Pasat, E.; Vascenco, A.; Esanu, A.; Lutica, N. Predictors of Atherosclerotic Plaque Progression in Patients with Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease. Atherosclerosis 2021, 331, e154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, J.J.; MacDonnell, C.; Arnous, S.; Kiernan, T.J. Fractional Flow Reserve in 2017: Current Data and Everyday Practice. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2017, 15, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, F.; Biccirè, F.G.; Budassi, S.; Di Pietro, R.; Albertucci, M. Intracoronary Imaging Guidance of Percutaneous Coronary Interventions: How and When to Apply Validated Metrics to Improve the Outcome. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2024. [CrossRef]

- Okutucu, S.; Cilingiroglu, M.; Feldman, M.D. Physiologic Assessment of Coronary Stenosis: Current Status and Future Directions. Curr Cardiol Rep 2021, 23, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalidis, I.; Meier, D.; De Bruyne, B.; Collet, C.; Sonck, J.; Mahendiran, T.; Rotzinger, D.; Qanadli, S.D.; Eeckhout, E.; Muller, O.; et al. Diagnostic Performance of Angiography-derived Fractional Flow Reserve in Patients with NSTEMI. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions 2023, 101, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surev, A.; Abras, M.; Ciobanu, L.; Grib, A.; Moiseeva, A.; Diaconu, N. Post PCI Coronary Flow Evaluation in Low and Intermediate Risk Non-STEMI Pacients: Immediate versus Delayed Reperfusion. Atherosclerosis 2020, 315, e252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, W.F.; Bornschein, B.; Tonino, P.A.L.; Gothe, R.M.; Bruyne, B. De; Pijls, N.H.J.; Siebert, U. Economic Evaluation of Fractional Flow Reserve–Guided Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients With Multivessel Disease. Circulation 2010, 122, 2545–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puymirat, E.; Cayla, G.; Simon, T.; Steg, P.G.; Montalescot, G.; Durand-Zaleski, I.; le Bras, A.; Gallet, R.; Khalife, K.; Morelle, J.-F.; et al. Multivessel PCI Guided by FFR or Angiography for Myocardial Infarction. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 385, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfaramawy, A.; Hassan, M.; Nagy, M.; ElGuindy, A.; Elmahdy, M.F. Impact of Fractional Flow Reserve on Decision-Making in Daily Clinical Practice: A Single Center Experience in Egypt. Egyptian Heart Journal 2018, 70, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).