1. Introduction

Molecular diagnostic tools play a crucial role in pathogen identification and controlling the transmission of pathogenic bacteria. Although polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology has long been considered the gold standard for molecular diagnosis, it requires specialized instrumentation, trained personnel, and controlled laboratory environments. Consequently, significant efforts have been devoted to developing more accessible and simplified molecular diagnostic technologies.CRISPR technology was initially developed for gene editing. Subsequent studies revealed that Cas13, Cas12, Cas14, and Cas9 proteins also possess trans-cleavage activity[

1,

2,

3,

4].According to the trans-cleavage activity of Cas proteins, a series of detection platforms have been developed, including HOMES, DETECTOR, and SHERLOCK. CRISPR-based detection technologies have attracted significant attention due to their high sensitivity, specificity, and cost-effectiveness. When combined with lateral flow assay (LFA) technology, CRISPR-based detection becomes more portable, enabling nucleic acid testing without the need for expensive PCR instruments[

5,

6,

7].

Although CRISPR-based detection offers numerous advantages, it still requires integration with isothermal amplification or PCR for low-abundance targets [

8,

9,

10]. However, compatibility issues exist between CRISPR detection and amplification systems (e.g., isothermal amplification or PCR). Consequently, the initial approach involved conducting amplification and CRISPR detection in separate steps, where amplification preceded detection [

11,

12]. To address this limitation, a one-pot assay was subsequently developed, combining isothermal amplification and CRISPR detection in a single reaction tube [

13,

14]. These technological advancements have established CRISPR-based detection as a next-generation molecular diagnostic tool.

While the integration with isothermal amplification enables the detection of low-abundance targets, it concomitantly increases costs and operational complexity, thereby limiting the broader application of CRISPR-based diagnostics. Consequently, significant efforts have been devoted to developing amplification-free CRISPR detection technologies. For instance, Sha et al. [

15] achieved femtomolar (fM) sensitivity by conjugating Cas13 and Cas14 proteins through hybrid DNA hairpins. Similarly, Shi et al. [

16] engineered a split CRISPR guide RNA (scgRNA) with dual functionality: upon cleavage, it generates both a fluorescent signal and novel target DNA recognized by the T2 complex. Subsequent T2 complex activation induces further scgRNA cleavage, establishing a positive feedback loop that exponentially amplifies the fluorescent signal. Additionally, Lim et al. [

17] attained attomolar (aM) detection sensitivity using biotin-labeled hairpin DNA as a signal amplifier. Despite these advancements, current amplification-free CRISPR detection systems face challenges, including complex signal amplifier, high background signals, and a predominant reliance on LbCas12a protein, with limited reports on alternative variants such as AsCas12a and FnCas12a.

This study established an amplification-free CRISPR detection platform by utilizing hairpin DNA as a signal amplifier in conjunction with AsCas12a protein. Through optimization of buffer composition and hairpin DNA configuration, femtomolar-level DNA detection sensitivity was achieved. Notably, we demonstrated that AsCas12a outperformed the commonly used LbCas12a protein in this system, and that high-salt conditions effectively suppressed background signals generated by hairpin DNA. The method's sensitivity and specificity were rigorously evaluated using T. gondii and L. monocytogenes as model targets, followed by validation with real samples. Collectively, this work presents a novel amplification-free CRISPR-based detection approach with high sensitivity and specificity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Proteins and Nucleic Acids

The CRISPR/Cas12a proteins, including AsCas12a (Cpf1) Nuclease (32104) and LbCas12a (Cpf1) Nuclease (32108), were procured from Tolobio Technology and diluted according to experimental requirements prior to use. The

Toxoplasma gondii B1 gene fragment was synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai), dissolved, and stored at -20°C for subsequent experiments.The crRNA sequences were designed using the online tool available at

https://ezassay.com/primer. The hairpin DNA was designed based on the report by Jae Hoon Jeung et al. [

18], while the reporter probe was selected with reference to the study by Li Linxian et al. [

19]. All oligonucleotides, including crRNA, hairpin DNA, and reporter probes, were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai). The synthesized hairpin DNA was dissolved in TE buffer (pH 8.0) and diluted to a final concentration of 10 μM. Subsequently, gradient annealing was performed to ensure proper secondary structure formation before use.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide sequences utilized in this study.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide sequences utilized in this study.

| Name |

Sequence |

Application |

| GT-crRNA |

UAAUUUCUACUGUUGUAGAUCUCUCUUCACUGUCACGUAC |

crRNA for the B1 gene |

| Act-crRNA |

UAAUUUCUACUCUUGUAGAUUUCCGCAAUACUCCCCCAGGU |

crRNA for Act DNA |

| Act-ssDNA |

ACC TGG GGG AGT ATT GCG GAG GAA GGT |

single-stranded Act DNA |

| Act-ssDNA-C |

ACCTTCCTCCGCAATACTCCCCCAGGT |

Complementary strand of Act DNA |

| T7-crRNA-F |

GAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGG |

In vitro transcription of crRNA targeting the hly gene of L. monocytogenes

|

| T7-LM2-R2 |

CAGGGAGAACATCTGGTTGAATCTACAACAGTAGAAATTCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAATTTC |

| ssDNA |

5’FAM-TCTACTCTC-3’BHQ1 |

Reporter probe |

| Act-H-2p |

GGA ACC TGG GGG AGT ATT GCG GAG GAATTTTC CTC CGC AAT ACT CCC CCA GGT TCC |

Screening of hairpin DNA loop length |

| Act-H-4p |

GGA ACC TGG GGG AGT ATT GCG GAG GAATTTTTTC CTC CGC AAT ACT CCC CCA GGT TCC |

| Act-H-6p |

GGA ACC TGG GGG AGT ATT GCG GAG GAATTTTTTTTC CTC CGC AAT ACT CCC CCAGGT TCC |

| Act-H-8p |

GGA ACC TGG GGG AGT ATT GCG GAG GAATTTTTTTTTTC CTC CGC AAT ACT CCC CCAGGT TCC |

| Act-H-10p |

GGA ACC TGG GGG AGT ATT GCG GAG GAATTTTTTTTTT TTCC TCC GCA ATA CTC CCCCAG GTT CC |

| Act-H-8p-C |

GGA ACC TGG GGG AGT ATT GCG GAG GAACCCCCCCCTTC CTC CGC AAT ACT CCC CCAGGT TCC |

Screening of hairpin loop compositions |

| Act-H-8p-A |

GGA ACC TGG GGG AGT ATT GCG GAG GAAAAAAAAAATTC CTC CGC AAT ACT CCC CCAGGT TCC |

| Act-H-8p-G |

GGA ACC TGG GGG AGT ATT GCG GAG GAAGGGGGGGGTTC CTC CGC AAT ACT CCC CCAGGT TCC |

| GT-95DNA-T |

GGCGGACCTCTCTTGTCTCGAATACACGAACGAGATCTGCTGGATCTCTTCCCTTGAATGCGATGTCGTACGTGACAGTGAAGAGAGGAAACAGG |

B1 gene fragment |

| Act-H-2Loop-Bio |

Bio-TGGA ACC TGG GGG AGT ATT GCG GAG GATTTATTT TCC TCC GCA ATACTTATTTC CCC CAG GTTCCA |

Screening of labeled hairpin loops |

| Act-H-2Loop-N |

TGGA ACC TGG GGG AGT ATT GCG GAG GATTTATTT TCC TCC GCA ATACTTATTTC CCC CAG GTTCCA |

2.2. Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) Analysis

The polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) kit was purchased from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, C631101-0100). A 20 μL reaction mixture was prepared as follows:1 μL of 1 μM Cas12a protein、1 μL of 2 μM crRNA、1 μL of 10 ng/μL target DNA、2 μL of 10× NEB Buffer 3.1、1 μL of 10 μM hairpin DNA (HP-DNA)、14 μL of deionized water. The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 60 min to allow Cas12a-mediated cleavage of the hairpin DNA loop region, converting it into linear DNA. A 15% polyacrylamide gel was prepared with the following components: 6 mL of 30% acrylamide/bis-acrylamide solution、3.6 mL of distilled water、2.4 mL of 5× Tris-Borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer、200 μL of 10% ammonium persulfate (APS)、10 μL of TEMED (N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine)、The gel was polymerized at room temperature before electrophoresis.Electrophoresis Conditions: Running buffer: 1× TBE、Voltage: 100 V、Duration: 75 min. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with GelRed Nucleic Acid Stain for 20 min and visualized using the GelDoc XR Imaging System (Bio-Rad, CA, USA).

2.3. Validation of Hairpin DNA Effects on Cas12a Trans-Cleavage Activity

The Cas12a/crRNA complex was prepared by mixing 1 μL of 1 μM Cas12a protein and1 μL of 2 μM crRNA. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 10 min to facilitate the formation of the Cas12a/crRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex.

Evaluation of Inhibitory Effects: The inhibitory activity was assessed using a 20 μL CRISPR/Cas12a reaction system containing:1 μL RNP2(pre-assembled Cas12a/crRNA complex 2)、1 μL 10 μM hairpin DNA 、2 μL 10× NEB buffer、1 μL 10 μM fluorescent reporter probe、15 μL nuclease-free water. The reaction mixture was incubated at 35°C for 60 min, with real-time fluorescence measurements recorded using QuantStudio5.

Evaluation of Activatory Effects: A 20 μL primary reaction containing: 1 μL RNP1(pre-assembled Cas12a/crRNA complex 1)、1 μL 10 ng/μL target DNA、2 μL 10× NEB buffer、1 μL 10 μM hairpin DNA 、15 μL nuclease-free water. After 60 min incubation at 37°C, the reaction was heat-inactivated at 85°C for 10 min to denature Cas12a activity, followed by cooling to room temperature. Then 1 μL RNP2 and 1 μL 10 μM ssDNA reporter were added to the mixture. The reaction proceeded at 37°C for 40 min with continuous fluorescence monitoring.

2.4. Single Cas12a Assay

The Cas12a/crRNA complex was prepared by mixing 1 μL of 1 μM Cas12a protein and1 μL of 2 μM crRNA. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 10 min to facilitate the formation of the Cas12a/crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex. The reaction scale could be proportionally increased based on experimental requirements. For a single Cas12a reaction, a 20 μL reaction mixture was prepared as follows: 1μL RNP、2 μL of 10× NEB Buffer、2μL target DNA、1μL 10μM ssDNA reporter、14 μL of deionized water.The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 60 min in a real-time fluorescence PCR system (QuantStudio5). Fluorescence signals (FAM) were recorded at 30-sec intervals to monitor Cas12a-mediated trans-cleavage activity.

2.5. CRISPR- Cascade Assay

To simplify the workflow and minimize aerosol contamination, we integrated the target recognition and signal amplification steps into a single PCR tube. A 20 μL reaction mixture was prepared as follows:1 μL RNP1 (pre-assembled Cas12a/crRNA complex 1)、1 μL RNP2 (pre-assembled Cas12a/crRNA complex 2)、2 μL Target DNA、2 μL 10× NEB Buffer 3.1、2 μL 0.5 μM Hairpin DNA (hpDNA, substrate for signal amplification)、11 μL Nuclease-free water、 1 μL 10 μM Fluorescent Reporter Probe (FAM-ssDNA-BHQ1) inner surface of the PCR tube cap. After gently sealing the PCR tube, incubate at 30°C for 20 min to allow target recognition and singal amplification. Then centrifuge and mix the tube (8000 rpm,15 sec). Incubate the reaction at 30°C for 60 min while monitoring real-time fluorescence (FAM channel) at 30-sec intervals using QuantStudio5 qPCR instrument.

2.6. Evaluation of Reaction System Specificity and Sensitivity

To assess the specificity of the established detection system, genomic DNA from four distinct parasites (Toxoplasma gondii, Clonorchis sinensis, Cryptosporidium parvum and Babesia) as well as genomic DNA from Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, Salmonella enteritidis, and Staphylococcus aureus were collected.

For sensitivity evaluation, a synthetic DNA fragment of the T. gondii B1 gene was utilized as the amplification template. Ten-fold serial dilutions were prepared, covering a concentration range of 100 nM to 10 fM, and 2 μL of each dilution was used for assessment. Additionally, L. monocytogenes genomic DNA was subjected to gradient dilution (500 pg/μL to 50 fg/μL) to evaluate the sensitivity of the proposed method.

2.7. Detection of Artificially Spiked Samples

To assess the detection performance of the established method on real-world samples, we prepared 30 artificially simulated samples. T. gondii Samples: A 10 g portion of beef sample was minced and mixed with 90 mL of sterile saline solution (0.9% NaCl), followed by homogenization at medium speed for 15 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 500 r/min for 30 s to remove large food particles. After nucleic acid extraction, a T. gondii B1 gene fragment was added at a final concentration of 100 fM. L. monocytogenes Samples: A 10 g portion of beef sample was minced and mixed with 90 mL of sterile saline solution (0.9% NaCl), followed by homogenization at medium speed for 15 min. Different concentrations of L. monocytogenes were added to 900 μL of the homogenate and thoroughly mixed by vortexing. The spiked samples were centrifuged at 500 r/min for 30 s to remove large food particles. The supernatant was subjected to nucleic acid extraction via DNA extraction kit and subsequently detected using the cascade-CRISPR assay.

3. Results

3.1. One-Tube Amplification-Free CRISPR/Cas12a Detection Workflow

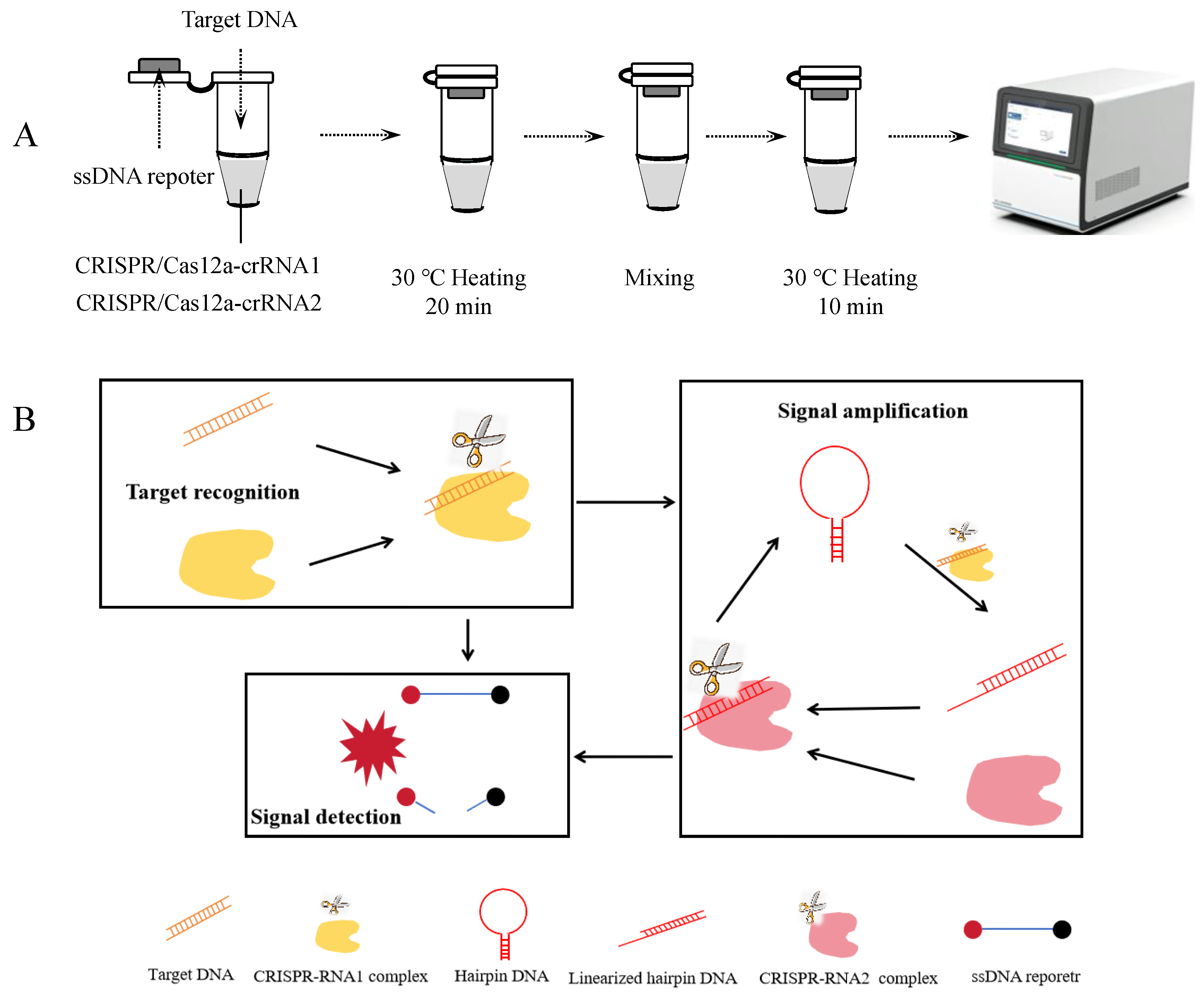

The amplification-free CRISPR/Cas12a detection process is illustrated in Figures 1A and 1B. This assay consists of three key steps: target recognition, signal amplification, and signal detection. When the target DNA fragment is present in the reaction system, the trans-cleavage activity of the RNP1 complex is activated. RNP1 cleaves the loop region of the hairpin DNA, converting it into linearized DNA. Subsequently, the linearized hairpin DNA activates the trans-cleavage activity of the RNP2 complex, which further cleaves additional hairpin DNA molecules, generating more linearized hairpin DNA and establishing a cascading amplification cycle. Simultaneously, the activated RNP1 and RNP2 complexes cleave single-stranded reporter DNA present in the system. The reporter DNA is labeled with a FAM fluorophore at one end and a BHQ1 quencher at the other. Upon cleavage, the fluorophore is separated from the quencher, resulting in a detectable fluorescence signal.

Figure 1.

Amplification-free CRISPR-Cas12a detection. (A) Workflow of the amplification-free CRISPR-Cas12a assay. (B) Schematic diagram of the amplification-free CRISPR-Cas12a detection.

Figure 1.

Amplification-free CRISPR-Cas12a detection. (A) Workflow of the amplification-free CRISPR-Cas12a assay. (B) Schematic diagram of the amplification-free CRISPR-Cas12a detection.

3.2. Feasibility Analysis of the Amplification-Free Detection System

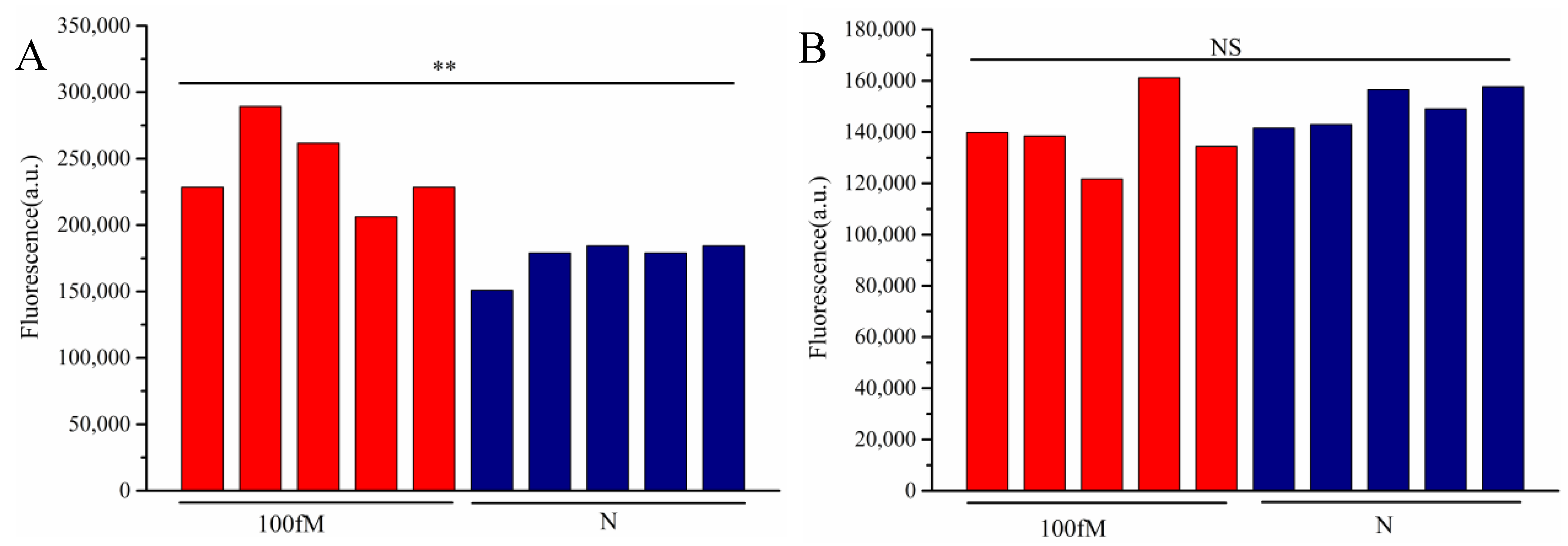

To establish an amplification-free detection system using hairpin DNA, we first evaluated the inhibitory effect of hairpin DNA on the trans-cleavage activity of CRISPR/Cas12a proteins. As shown in

Figure 2A, we tested three commonly used Cas12a proteins: FnCas12a, LbCas12a, and AsCas12a. The results demonstrated that hairpin DNA exhibited varying degrees of inhibition on the trans-cleavage activity of all three Cas12a proteins, with the weakest inhibition observed for LbCas12a. While FnCas12a and AsCas12a showed comparable inhibition effects, the AsCas12a detection system generated the strongest fluorescent signal when double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) was used as the target. Therefore, AsCas12a was selected for subsequent experiments.

Next, we assessed the cleavage efficiency of AsCas12a on hairpin DNA. In

Figure 2B, comparison between lanes 2 and 4 revealed that after adding target DNA, the CRISPR/Cas12a-crRNA1 complex cleaved the hairpin DNA into two bands: an upper band corresponding to linearized hairpin DNA and a lower band representing intact hairpin DNA. This result confirmed partial cleavage of hairpin DNA into linear DNA.

We then evaluated the activation effect of linearized hairpin DNA on AsCas12a. The CRISPR/Cas12a-crRNA1 complex, targeting the

T. gondii B1 gene, was used to cleave hairpin DNA. After the reaction, heat treatment at 85°C for 10 min was performed to inactivate the CRISPR/Cas12a-crRNA1 complex. Upon cooling to room temperature, the hairpin DNA regained its double-stranded structure. Subsequently, the CRISPR/Cas12a-crRNA2 complex and single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) reporter probe were added to the system to measure fluorescence intensity. As illustrated in

Figure 2C, when the CRISPR/Cas12a-crRNA2 complex (targeting linearized hairpin DNA) was introduced into the inactivated CRISPR/Cas12a-crRNA1 system, the reaction mixture containing linearized hairpin DNA produced a stronger fluorescent signal than that containing only intact hairpin DNA. This finding demonstrated that linearized hairpin DNA could effectively activate the trans-cleavage activity of AsCas12a.Collectively, these results confirm the feasibility of establishing an amplification-free CRISPR detection system using hairpin DNA.

Screening of different Cas12a proteins(A),Verification of trans-cleavage activity on hairpin DNA(B):Lane 1: RNP1,Lane 2: 8T-HP,Lane 3: RNP1 + target,Lane 4: RNP1 + target + 8T-HP, M: DNA ladder and Validation of linearized hairpin DNA activation efficacy(C). In the chart, bars represent the mean average value, and the error bar represents the standard deviation.

3.3. Optimization of Amplification-Free Detection System

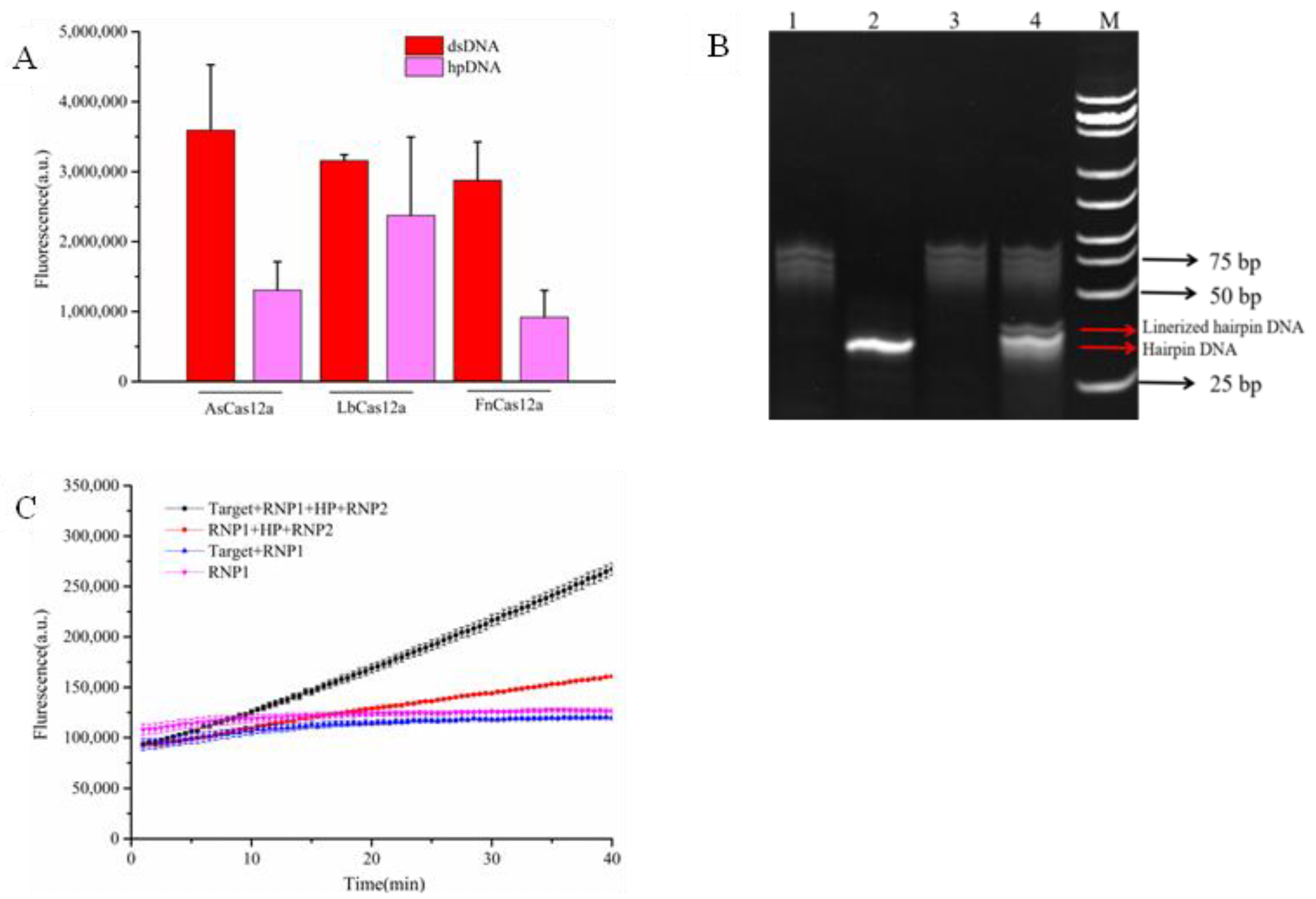

Given that reaction temperature can influence the stability of hairpin DNA structures, we evaluated the trans-cleavage efficiency of the CRISPR/Cas12a-crRNA1 complex on hairpin DNA at 30 °C, 35 °C, 40 °C, 45 °C, 50 °C, and 55 °C. Under identical conditions, the fluorescence signal generated by linearized double-stranded DNA was divided by that produced by hairpin DNA as the evaluation metric. As shown in

Figure 3A, the highest fold increase (2.6-fold) was observed at 30°C, indicating optimal performance at this temperature. Subsequently, we assessed the cleavage efficiency of the CRISPR/Cas12a-crRNA2 complex on single-stranded reporter DNA at 20 °C, 25 °C, 30 °C, 35 °C, and 40 °C (

Figure 3B). While the trans-cleavage activity of CRISPR/Cas12a-crRNA2 on single-stranded reporter DNA increased with rising temperature, the background signal also gradually intensified. A maximum fold change of 4.6 was observed at 30 °C, prompting its selection as the preferred reaction temperature.

Different reaction buffers can also affect the cleavage activity of the Cas12a protein. We evaluated 10× NEB buffer 1.1, 10× NEB buffer 2.1, 10× NEB buffer 3.1, 10× NEB CutSmart buffer, and 10× HOMLES buffer. Over time, the inhibitory effects of 10× NEB buffer 1.1, 10× NEB buffer 2.1, and 10× NEB CutSmart buffer gradually weakened, whereas 10× NEB buffer 3.1 and 10× HOMLES buffer demonstrated superior and comparable suppression efficacy (Figure C). Comparative analysis of buffer compositions revealed that the primary difference among 10× NEB buffer 1.1, 10× NEB buffer 2.1, and 10× NEB buffer 3.1 lay in NaCl concentration. By supplementing buffer 1.1 with varying NaCl concentrations, we observed a progressive reduction in background signal with increasing NaCl levels, suggesting that elevated NaCl concentrations effectively suppress background noise.

The composition of hairpin DNA also influences the cleavage efficiency of the Cas12a protein. We examined the inhibitory effects of hairpin DNAs with different loop lengths (2 bp, 4 bp, 6 bp, 8 bp, and 10 bp) on Cas12a at 35 °C for 60 minutes. The 8 bp loop length exhibited the strongest suppression(Figure D). Additionally, we evaluated the impact of different base compositions in the loop region on Cas12a cleavage, using the ratio of fluorescence signals from linearized hairpin DNA to hairpin DNA as the metric. As illustrated in Figure E, hairpin DNA with an adenine loop demonstrated the most favorable performance. The number of loops in the hairpin structure may also affect cleavage efficiency. Comparative analysis of hairpin DNAs with one versus two loops revealed that the single-loop variant generated stronger fluorescence signals and superior inhibitory effects (Figure F).Unexpectedly, we observed that biotin-modified hairpin DNA exhibited inferior inhibitory effects(

Figure S2).

Ultimately, the optimized detection system conditions were determined as follows: reaction buffer (10× NEB buffer 3.1), AsCas12a as the detection protein, 30°C for CRISPR/Cas12a-crRNA1 detection system, 8 bp-adenine loop hairpin DNA as the signal amplifier, and 30°C for CRISPR/Cas12a-crRNA2 detection system.

Temperature screening for CRISPR/Cas12a-crRNA1-mediated cleavage of hairpin DNA(A),Temperature screening for CRISPR/Cas12a-crRNA2-mediated cleavage of ssDNA reporter(B),Optimization of reaction buffer conditions(C),Screening of hairpin DNA loop length(D),Evaluation of hairpin DNA loop base composition(E),Optimization of hairpin DNA loop quantity(F). In the chart, bars represent the mean average value, and the error bar represents the standard deviation.

3.4. Evaluation of Detection Sensitivity and Specificity

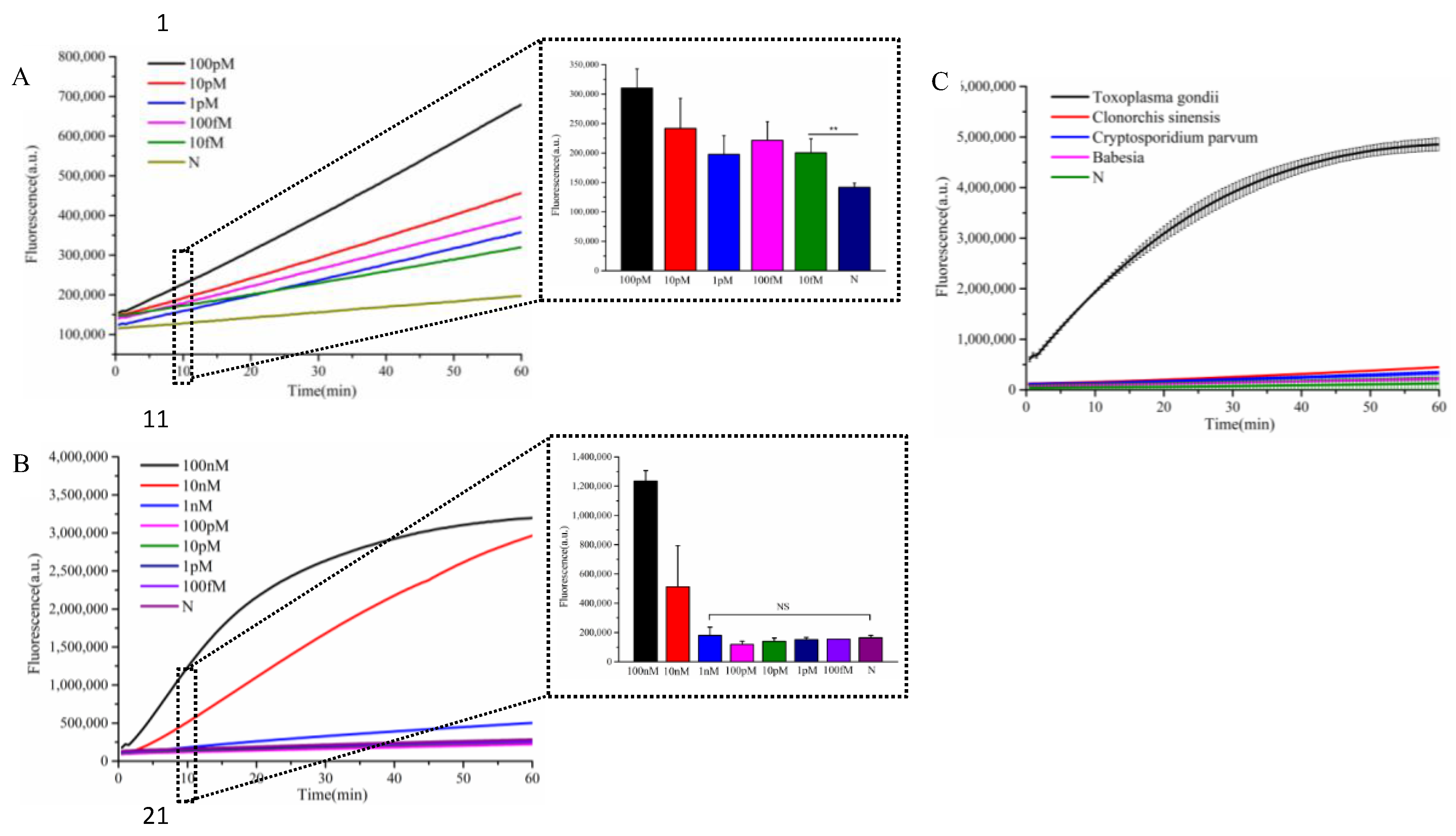

To assess the specificity of the established detection system, we tested four distinct parasitic species. As shown in

Figure 4A, only

T. gondii generated a strong fluorescence signal, while non-

T. gondii parasites exhibited no significant signal variation, confirming the high specificity of the assay. For sensitivity evaluation, we used a synthetic DNA fragment of the

T. gondii B1 gene as the target.

Figure 4B demonstrates that the system could detect concentrations as low as 10 fM, whereas single Cas12a detection methods only achieved a limit of detection of 1 nM—indicating a 10

5 fold improvement in sensitivity. Notably, this method enabled the detection of

T. gondii B1 gene fragments at 10 fM within just 30 minutes. (

20 min for target recognition and singal amplification, 10 min for detection)

Sensitivity analysis of Cascade-CRISPR-based T. gondii detection(A), Sensitivity assessment of single Cas12a-mediated T. gondii detection(B), Specificity testing of Cascade-CRISPR system for T. gondii identification(C). In the chart, bars represent the mean average value, and the error bar represents the standard deviation. p<0.01(**), no significant difference(NS)

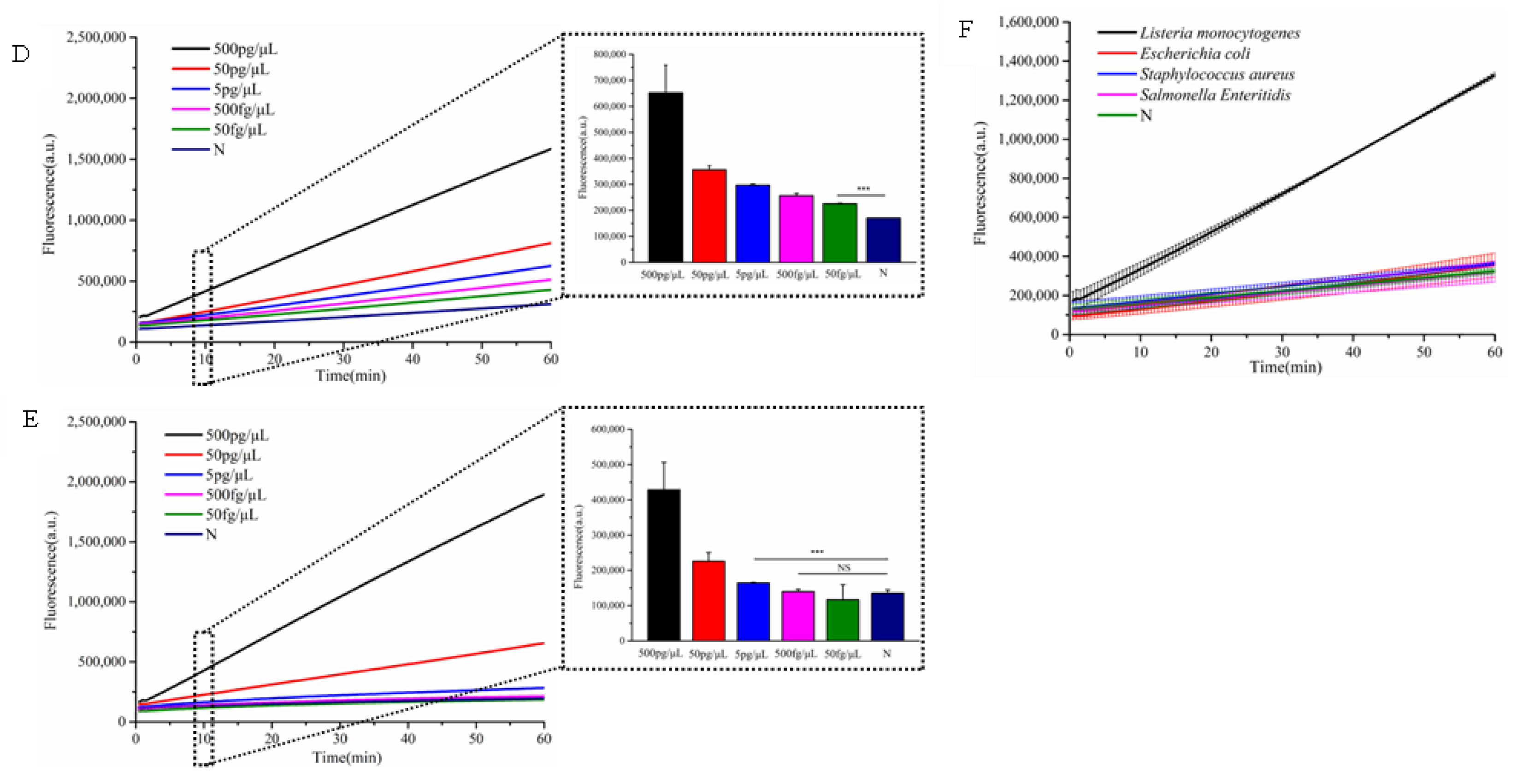

To further demonstrate the broad applicability of the designed hairpin DNA signal amplifier , we selected the

L. monocytogenes hemolysin virulence gene (

hly) as the target and designed corresponding crRNA1 to evaluate the method's sensitivity and specificity. As illustrated in

Figure 5, only genomic DNA from

L. monocytogenes triggered a significantly enhanced fluorescence signal, while non-target samples produced negligible background signals. This confirms the high specificity of the detection system for

L. monocytogenes. The assay demonstrated exceptional sensitivity, detecting

L. monocytogenes DNA at concentrations as low as 50 fg/μL—a 100-fold improvement over single CRISPR-based methods, which had a detection limit of 5 pg/μL. Notably, this ultra-sensitive detection was achieved within 30 minutes, highlighting the rapidity and efficiency of the cascade-CRISPR approach.

Sensitivity analysis of cascade-CRISPR-based L. monocytogenes detection(D), Sensitivity assessment of single Cas12a-mediated L. monocytogenes detection(E), Specificity testing of Cascade-CRISPR system for L. monocytogenes identification(F). In the chart, bars represent the mean average value, and the error bar represents the standard deviation. p<0.001(***), no significant difference(NS)

3.5. Detection of Artificially Spiked Samples

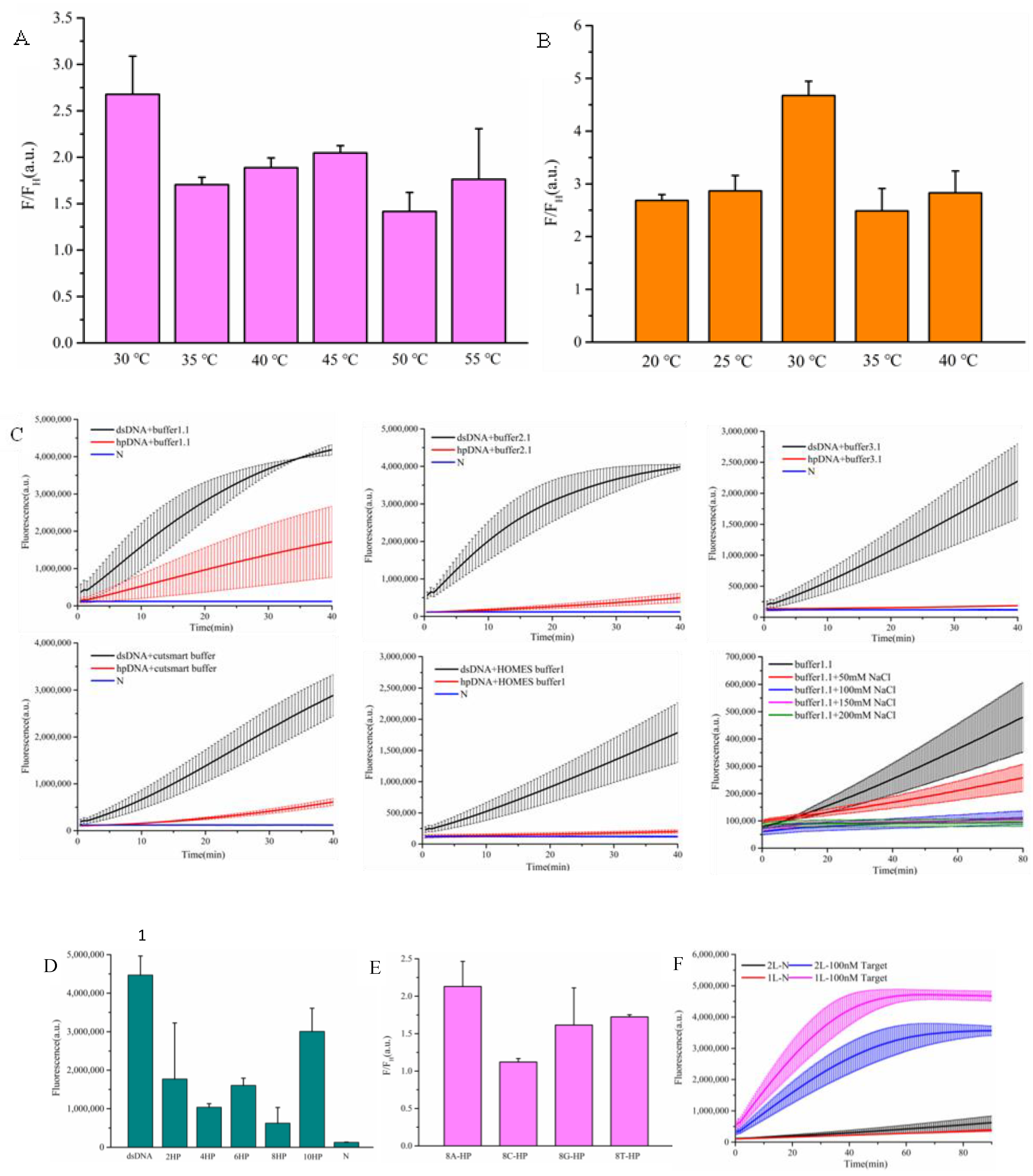

The detection was performed on artificially contaminated raw beef samples, with quantitative fluorescence PCR (qPCR) serving as the control. As shown in

Table 2, qPCR detected 10 positive samples out of 20, while cascade-CRISPR also identified 10 positives. In contrast, the single Cas12a method only detected 6 positive samples. Notably, all samples missed by the single Cas12a method exhibited relatively low target concentrations. Consistent with these findings, the

T. gondii detection results demonstrated that the single Cas12a method failed to detect nucleic acids at concentrations as low as 100 fM, whereas cascade-CRISPR maintained detectable sensitivity at this level.

Figure 6.

Results of 100 fM DNA detection in beef samples, detection based on Cascade-CRISPR(A), detection based on single Cas12a (B),p<0.01(**), no significant difference(NS).

Figure 6.

Results of 100 fM DNA detection in beef samples, detection based on Cascade-CRISPR(A), detection based on single Cas12a (B),p<0.01(**), no significant difference(NS).

4. Discussion

In recent years, the increasing demand for rapid testing has driven significant advancements in molecular point-of-care testing (POCT) technologies. Within the field of foodborne pathogen detection, methodological evolution has progressed from conventional culture-based methods and classical PCR to various isothermal amplification techniques, including recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA), loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), and rolling circle amplification (RCA) [20-22]. However, practical implementation has revealed limitations: isothermal amplification either requires complex reaction systems (e.g., RPA necessitates three distinct enzymes) or involves sophisticated primer design (e.g., LAMP requires 4-6 primers). Moreover, the constant temperature conditions predispose these methods to false-positive results [

23], thereby restricting their widespread adoption.This technological gap has spurred interest in CRISPR-based detection systems. The integration of CRISPR with isothermal amplification addresses both the false-positive issues inherent to isothermal methods and the limited sensitivity of CRISPR for low-abundance targets. However, this combined approach increases operational complexity and elevates costs, highlighting the need for amplification-free CRISPR detection strategies.

Several innovative systems have emerged: Shi et al. [

16] developed the CONAN system using fluorophore-labeled ssDNA/RNA hybrids as signal amplifiers, achieving 1 aM sensitivity within 20 min. Deng et al. [

24] employed circular DNA amplifiers in the AutoCAR system (15-60 min for 1 aM detection). Sun et al. [

25] created the CALSA system with LNA-modified ssDNA amplifiers (50 fM sensitivity in 1 h). Lim et al. [

17] utilized biotinylated hairpin DNA for 1 aM detection in 10 min. While these studies demonstrated single-tube, isothermal detection using a solitary CRISPR protein, their signal amplifiers faced challenges in synthesis difficulty, high cost, and elevated background signals.

This study establishes a novel amplification-free CRISPR-based detection technology utilizing hairpin DNA as the signal amplifier and

AsCas12a protein. The hairpin DNA amplifiers can be readily prepared through simple synthesis followed by annealing, offering significant advantages in both simplicity of production and cost-effectiveness. Elevated NaCl concentrations provided additional background suppression. While Zhou et al. [

26] achieved femtomolar-level detection (83 fM) using hairpin DNA amplifiers with

LbCas12a, their system exhibited substantial background interference. Previous studies have reported that elevated NaCl concentrations attenuate the trans-cleavage activity of Cas12a proteins [

27]. In our system, the inherently weak activation of Cas12a's trans-cleavage by hairpin DNA, combined with this salt-mediated suppression, synergistically reduced non-specific background signals. Unexpectedly, we observed that biotin modification actually increased background signals, indicating this strategy lacks universal applicability. In conclusion, this study demonstrates a single-tube, amplification-free nucleic acid detection system utilizing hairpin DNA and AsCas12a protein. The hairpin DNA-based signal amplifier offers facile synthesis and low production cost, achieving femtomolar (fM) sensitivity within 30 minutes.

Although CRISPR-based detection offers significant advantages over existing technologies, several challenges remain to be addressed. For instance, achieving multiplex detection in a single-tube system using a single Cas protein requires further optimization. Additionally, our study observed that nucleic acids rapidly extracted using automated extraction systems exhibit strong inhibition in CRISPR-based assays, while their impact on qPCR detection was minimal (data not shown). These findings highlight the need to improve the impurity tolerance of CRISPR detection systems.

5. Conclusions

This study established an amplification-free detection system based on the AsCas12a protein by utilizing hairpin DNA. Through optimization of hairpin DNA composition, reaction buffer, and reaction temperature, the system achieved detection of DNA at the femtomolar (fM) level. By adjusting the NaCl concentration in the reaction buffer, the background signal of the reaction was effectively reduced. The high specificity and sensitivity of this method were demonstrated through the detection of Toxoplasma gondii and Listeria monocytogenes, with a short detection time of only 30 minutes. Notably, when detecting different targets, only RNP1 needed to be replaced while RNP2 remained unchanged, indicating the universal applicability of the hairpin DNA amplifier in this system. Artificial contamination experiments further confirmed the feasibility of this method for detecting foodborne pathogens in real-world samples. In summary, this study developed a simple and practical amplification-free CRISPR detection method, which holds great potential for the rapid identification of foodborne pathogens.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org Figure S1: Melting curves of hairpin DNA Act-H-8p-A、Act-H-2Loop-N, and Act-H-2Loop-Bio. Figure S2: Verification of trans-cleavage activation by biotin-labeled versus unlabeled hairpin DNAs on AsCas12a protein.

Author Contributions

D. conducted all the experiments and drafted the manuscript; S.M. conducted most of the experiments and revise the manuscript; L.B. provided the foodborne bacterial isolate and assisted in performing experiments related to foodborne bacteria, including DNA extraction, detection of L. monocytogenes and detection of artificially spiked samples; M.J. provided softwa and data curation. Z.Q. participated in experimental design and project administration; Y.W. participated in the detection of T. gondii; L.J.,W.M.and L.L. participated in the optimization of the experiment; Y.P. was involved in experimental design and offered substantive technical recommendations; S.Y. contributed parasite DNA samples, participated in experimental design, and secured research funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 82372283) and Jiangsu Province Preventive Medicine Research Project (Ym2023085) .

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Professor Hua Cong for kindly providing T. gondii strains and for her valuable comments during the manuscript review process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gootenberg, J. S.; Abudayyeh, O. O.; Lee, J. W.; Essletzbichler, P.; Dy, A. J.; Joung, J.; Verdine, V.; Donghia, N.; Daringer, N. M.; Freije, C. A.; et al. Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR-Cas13a/C2c2. Science. 2017, 356, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S. Y.; Cheng, Q. X.; Wang, J. M.; Li, X. Y.; Zhang, Z. L.; Gao, S.; Cao, R. B.; Zhao, G. P.; Wang, J. CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted nucleic acid detection. Cell Discov. 2018, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, L. B.; Burstein, D.; Chen, J. S.; Paez-Espino, D.; Ma, E.; Witte, I. P.; Cofsky, J. C.; Kyrpides, N. C.; Banfield, J. F.; Doudna, J. A. Programmed DNA destruction by miniature CRISPR-Cas14 enzymes. Science 2018, 362, 839–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Huang, L.; Lin, X.; Chen, H.; Xiang, W.; Liu, L. Trans-nuclease activity of Cas9 activated by DNA or RNA target binding. Nat Biotechnol. 2025, 43, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Tang, H.; Li, R.; Xia, Z.; Yang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Lu, G.; Ni, S.; Shen, J. A New Method Based on LAMP-CRISPR-Cas12a-Lateral Flow Immunochromatographic Strip for Detection. Infect Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; Guo, J.; Meng, X.; Yao, M.; He, L.; Nie, X. , Xu; H., Liu, C.; Sun, J.; et al. Rapid detection of feline parvovirus using RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a-based lateral flow strip and fluorescence. Front Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1501635. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, X.; Yin, D.; Cai, C.; Liu, H.; Yang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Yin, L.; Shen, X.; Dai, Y.; et al. Rapid and Easy-Read Porcine Circovirus Type 4 Detection with CRISPR-Cas13a-Based Lateral Flow Strip. Microorganisms. 2023, 11, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Chen, Z.; Xie, R.; Li, J.; Liu, C.; He, Y.; Ma, X.; Yang, H.; Xie, Z. CRISPR/Cas12a-Assisted isothermal amplification for rapid and specific diagnosis of respiratory virus on an microfluidic platform. Biosens Bioelectron. 2023, 237, 115523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Cao, F.; Dai, T.; Liu, T. RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a-Mediated Isothermal Amplification for Rapid Detection of Phytopythium helicoides. Plant Dis. 2024, 108, 3463–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zeng, H.; Wu, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, J. Isothermal Amplification and CRISPR/Cas12a-System-Based Assay for Rapid, Sensitive and Visual Detection of Staphylococcus aureus. Foods 2023, 12, 4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Tong, X.; Han, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Duan, J.; Lei, X.; Huang, M.; Qiu, Y. Fast and sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA using suboptimal protospacer adjacent motifs for Cas12a. Nat Biomed Eng. 2022, 6, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broughton, J. P.; Deng, X.; Yu, G.; Fasching, C. L.; Servellita, V.; Singh, J.; Miao, X.; Streithorst, J. A.; Granados, A.; Sotomayor-Gonzalez, A.; et al. CRISPR-Cas12-based detection of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 870–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Yin, K.; Li, Z.; Lalla, R. V.; Ballesteros, E.; Sfeir, M. M.; Liu, C. Ultrasensitive and visual detection of SARS-CoV-2 using all-in-one dual CRISPR-Cas12a assay. Nat Commun. 2020, 11, 4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, X.; Wu, H.; Liu, J.; Xiang, J.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Q. One-pot diagnostic methods based on CRISPR/Cas and Argonaute nucleases: strategies and perspectives. Trends Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 1410–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y.; Huang, R.; Huang, M.; Yue, H.; Shan, Y.; Hu, J.; Xing, D. Cascade CRISPR/cas enables amplification-free microRNA sensing with fM-sensitivity and single-base-specificity. Chem Commun. 2021, 57, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Xie, S.; Tian, R.; Wang, S.; Lu, Q.; Gao, D.; Lei, C.; Zhu, H.; Nie, Z. A CRISPR-Cas autocatalysis-driven feedback amplification network for supersensitive DNA diagnostics. Sci Adv. 2021, 7, eabc7802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Van, A. B.; Koprowski, K.; Wester, M.; Valera, E.; Bashir, R. Amplification-free, OR-gated CRISPR-Cascade reaction for pathogen detection in blood samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2025, 122, e2420166122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeung, J. H.; Han, H.; Lee, C. Y.; Ahn, J. K. CRISPR/Cas12a Collateral Cleavage Activity for Sensitive 3'-5' Exonuclease Assay. Biosensors 2023, 13, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, S.; Wu, N.; Wu, J.; Wang, G.; Zhao, G.; Wang, J. HOLMESv2: A CRISPR-Cas12b-Assisted Platform for Nucleic Acid Detection and DNA Methylation Quantitation. ACS Synth Biol. 2019, 8, 2228–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladhadh, M. A Review of Modern Methods for the Detection of Foodborne Pathogens. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Chen, J.; Chen, D.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, K.; Lin, X.; Chen, J.; Song, D. Sensitive and rapid detection of three foodborne pathogens in meat by recombinase polymerase amplification with lateral flow dipstick (RPA-LFD). Int J Food Microbiol. 2024, 422, 110822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndraha, N.; Lin, H. Y.; Wang, C. Y.; Hsiao, H. I.; Lin, H. J. Rapid detection methods for foodborne pathogens based on nucleic acid amplification: Recent advances, remaining challenges, and possible opportunities. Food Chem. 2023, 7, 100183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Shi, X.; Shi, H.; Wang, Z.; Peng, C. Review in isothermal amplification technology in food microbiological detection. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2022, 31, 1501–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Li, Y.; Yang, B.; Sang, R.; Deng, W.; Kansara, M.; Lin, F.; Thavaneswaran, S.; Thomas, D. M.; Goldys, E. M. Topological barrier to Cas12a activation by circular DNA nanostructures facilitates autocatalysis and transforms DNA/RNA sensing. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Pu, L.; Chen, C.; Chen, M.; Li, K.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Geng, J. An autocatalytic CRISPR-Cas amplification effect propelled by the LNA-modified split activators for DNA sensing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Lau, C. H.; Wang, J.; Guo, R.; Tong, S.; Li, J.; Dong, W.; Huang, Z.; Wang, T.; Huang, X.; et al. Rapid and Amplification-free Nucleic Acid Detection with DNA Substrate-Mediated Autocatalysis of CRISPR/Cas12a. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 28866–28878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, I.; Song, Y. H.; Lee, S. Enhanced trans-cleavage activity using CRISPR-Cas12a variant designed to reduce steric inhibition by cis-cleavage products. Biosens Bioelectron. 2025, 267, 116859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).