1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Rationale

As the world becomes increasingly interconnected through globalization, societies are becoming more and more culturally diverse. Technological advancements and the digital economy further shape population diversity by enabling remote work and international collaboration, leading to culturally mixed communities [

1]. Another significant reason for this diversity is the rapid movement of people across borders due to economic opportunities, conflicts, and climate change that has led to multicultural healthcare environments where patients present varying linguistic, religious, and cultural needs [

2]. In primary healthcare, where early diagnosis, treatment, and prevention efforts are critical, the ability of nurses to deliver culturally competent care is essential to ensuring equitable and effective healthcare services [

3]. However, navigating cultural differences in healthcare can present ethical dilemmas, particularly when cultural beliefs and traditions conflict with biomedical principles or standard healthcare practices [

4].

Cultural competence is increasingly recognized as a fundamental skill in nursing, ensuring that healthcare providers are equipped to understand and respond to the diverse needs of their patients. At its core, cultural competence involves awareness, knowledge, and the ability to apply culturally appropriate communication and interventions in healthcare settings [

5]. Meanwhile, nursing ethics serve as a moral compass, guiding healthcare professionals to uphold patient rights, promote equity, and practice non-discriminatory care. However, ethical dilemmas frequently arise when cultural expectations intersect with healthcare policies, particularly in primary healthcare settings, where nurses play a crucial role in decision-making and patient advocacy [

6]. Despite the significance of these two concepts, research exploring the direct interrelationship between cultural competence and ethical nursing practice remains limited. This study aims to fill this gap by examining how cultural competence influences ethical decision-making among nurses in primary healthcare or how Knowledge, attitudes and practice of healthcare ethics and law among nurse influences cultural competence.

1.2. Cultural Competence in Nursing

Cultural competence in nursing refers to the ability of healthcare providers to effectively engage with patients from diverse backgrounds by acknowledging and respecting their cultural perspectives, values, and traditions. This concept extends beyond language barriers to encompass deeper aspects of cultural sensitivity, including respect for religious beliefs, dietary preferences, and social norms that shape patient health behaviors [

7]. Models such as Campinha-Bacote’s model of cultural competence emphasize that cultural competence is not an innate trait but rather a skill that must be cultivated through continuous education, self-awareness, and clinical experience [

8].

A growing body of research suggests that culturally competent nursing care is linked to improved patient satisfaction [

9], better adherence to treatment [

10], and overall enhanced healthcare outcomes [

11]. Studies have demonstrated that when nurses possess cultural competence, they are better able to build trust with their patients, minimize misunderstandings, and create a healthcare environment where individuals feel valued and respected [

12]. However, a lack of cultural competence can contribute to disparities in healthcare access and quality, as patients from minority backgrounds may feel alienated or misunderstood in clinical settings [

13].

Given these findings, integrating cultural competence training into nursing education and professional development programs has become a priority for healthcare organizations worldwide [

14]. Several national and international health bodies, including the World Health Organization (WHO), have advocated for cultural competence as a key competency in healthcare, emphasizing its role in eliminating health disparities and improving healthcare accessibility [

15,

16]. However, while cultural competence is widely recognized as an essential component of nursing practice, its connection to ethical decision-making requires further exploration.

1.3. Ethics in Nursing Practice

Ethical principles form the foundation of nursing practice, ensuring that healthcare providers act with integrity, respect, and compassion. The core ethical principles guiding nursing include autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice, all of which are designed to protect the rights and dignity of patients [

17]. Autonomy, for example, emphasizes a patient’s right to make informed decisions about their healthcare, while justice ensures fair and equitable access to medical resources. However, these principles can sometimes come into conflict with cultural traditions and values, creating complex ethical dilemmas for nurses [

18].

One of the most significant ethical challenges faced by nurses in culturally diverse settings involves balancing respect for cultural traditions with adherence to professional ethical guidelines [

19]. One of the key ethical challenges in multicultural healthcare settings is the principle of autonomy. In some cultures, family members may make healthcare decisions on behalf of a patient, which can contradict Western bioethical principles that prioritize individual autonomy [

20]. Similarly, end-of-life care preferences, religious beliefs regarding medical interventions, and differing attitudes toward gender roles in healthcare can all create ethical conflicts for nursing professionals [

21,

22,

23].

Another key ethical consideration is healthcare equity which refers to the principle of justice. Research has shown that minority and immigrant populations often experience barriers to healthcare, including discrimination, language barriers, and lower-quality care [

24]. Nurses, as patient advocates, must navigate these systemic challenges while ensuring that all patients receive equitable treatment regardless of cultural background [

25]. This responsibility highlights the importance of cultural competence as a tool for ethical nursing practice, as it enables nurses to recognize and address potential biases while upholding ethical standards.

1.4. The Interrelationship Between Cultural Competence and Ethics

The integration of cultural competence and ethical principles is essential for ensuring patient-centered care in today’s multicultural healthcare environments. Culturally competent nurses are better equipped to navigate ethical dilemmas by understanding the cultural contexts that influence patients’ health beliefs and decisions [

26]. According to Kuhlmann & Tallman [

27] a nurse who understands cultural variations in pain expression is more likely to make ethically sound treatment decisions that align with a patient’s needs, reducing the risk of undertreatment or misinterpretation.

Conversely, a lack of cultural competence can lead to ethical conflicts that compromise patient safety and trust. Miscommunication due to language barriers, for instance, can result in patients receiving inadequate information about their condition or treatment, which violates the ethical principle of informed consent [

28]. Similarly, cultural misunderstandings may lead to bias in clinical decision-making, negatively impacting patient outcomes [

29]. Nursing education and training programs must emphasize both cultural competence and ethical reasoning to prepare healthcare professionals for the complexities of modern clinical practice.

1.5. Study Objectives

Given the increasing diversity of healthcare settings and the ethical complexities that arise in multicultural environments, this study aims to explore the interrelationship between cultural competence and ethical decision-making among nurses in primary healthcare. To achieve this goal, we had to assess the level of cultural competence among nurses working in primary healthcare settings and evaluate nurses’ understanding of ethical principles and their application in culturally diverse clinical environments. In sequence, we examined the correlation between cultural competence and ethical decision-making in nursing practice, trying to identify challenges and barriers to providing culturally competent and ethically sound care in primary healthcare.

By addressing these objectives, this study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on the role of cultural competence in ethical nursing practice. The findings hopefully will provide valuable insights for nursing education, professional development, and healthcare policy, reinforcing the need for an integrated approach to cultural competence and ethics in primary healthcare.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This study employed a cross-sectional design to explore the association between cultural competence and ethical-deontological knowledge, attitudes, and practices among registered nurses working in public primary healthcare settings across mainland and insular Greece. The choice of Greece as the study setting is significant, as the country—and particularly its islands—serves as a major gateway for migrants and refugees into Europe. Nurses in these regions are frequently engaged in delivering care to culturally diverse patient populations, making them an ideal sample for this investigation.

2.2. Study Population and Sampling

This study employed a census approach, targeting the entire population of registered nurses employed in public primary healthcare units under the jurisdiction of the 2nd Regional Health Authority of Piraeus and the Aegean. This area includes both urban and island regions, ensuring geographic and institutional diversity. Questionnaires were distributed to all eligible nurses across these units to achieve comprehensive coverage and enhance the generalizability of the results.

The study population consisted exclusively of registered nurses meeting the following inclusion criteria: (a) active employment in a public primary healthcare unit within the specified region, and (b) a minimum of one year of professional experience in the public primary healthcare sector. To ensure the focus remained on nurses engaged in direct patient care, individuals occupying purely administrative or managerial positions were excluded. Additionally, student nurses were excluded due to their non-registered status and limited independent clinical responsibilities. Nurses working in other healthcare settings, such as hospitals or the private sector, were also excluded from the study.

A total of 737 questionnaires were distributed by mail to eligible participants. Of these, 492 were returned fully completed, resulting in a response rate of 67%. This level of participation reflects a strong engagement from the nursing workforce and contributes to the reliability and representativeness of the study findings.

2.3. Instruments and Data Collection

Data were collected using a composite questionnaire, combining two validated tools designed to assess cultural competence and ethical knowledge and attitudes:

2.3.1. Transcultural Self-Efficacy Tool (TSET-Gr)

To assess cultural competence, the TSET-Gr [

30] was used. This instrument was designed as a diagnostic tool to measure and evaluate nurses’ perceptions of self-efficacy concerning cultural care of patients from diverse backgrounds. The original Transcultural Self-Efficacy Tool (TSET) was developed and tested by Jeffreys and Smodlaka [

31,

32] and Jeffreys [

33]. The third edition of the tool was released by Jeffreys [

34]. According to the authors, the TSET is conceptually based on Bandura’s Social Learning Theory and self-efficacy as well as a review of the relevant transcultural nursing literature. This tool comprises 83 items rated on a 10-point Likert scale, where 1 = not at all confident and 10 = completely confident. It is divided into three subscales:

Cognitive (25 items): Evaluates self-efficacy regarding knowledge of cultural factors influencing nursing care.

Practical (30 items): Assesses self-efficacy in conducting culturally sensitive nursing interviews. Interview topics include items such as language preferences, religion, discrimination, and attitudes about health and illness.

Affective (28 items): Measures self-efficacy related to respecting values, attitudes and beliefs concerning cultural awareness, acceptance, appreciation, recognition, and advocacy.

2.3.2. Nurses’ Ethics Questionnaire (NEQ-Gr)

To measure knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to healthcare ethics, the Nurses’ Ethics Questionnaire (NEQ-Gr) [

35] was used. The original questionnaire was developed and tested by Hariharan et al [

36]. This 28-item instrument includes two sections:

The first section (13 items) evaluates:

Perceived frequency and clinical impact of common ethical/legal dilemmas in nursing practice

Perceived relevance of ethical/legal knowledge in clinical decision-making, including knowledge acquisition pathways

Preferred consultation resources when addressing ethical/legal challenges

Response formats include binary (Yes/No) choices and Likert-type scales.

The second section (15 items) assesses ethical dilemmas commonly encountered in nursing practice, employing a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Participants rated their agreement with statements addressing diverse ethical and legal challenges, thereby elucidating their ethical perspectives and bioethical awareness in clinical contexts.

Permissions for use of both tools were obtained from the authors of the tools, as well as from the authors of the original tools.

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

Data were collected between February 20, 2024, and May 31, 2024. The research questionnaire was prepared in printed form, and 737 of them were grouped in envelopes and mailed to all Public Primary Healthcare Units in the selected area, with instructions on how to return the questionnaire anonymously. Informed consent was included in the initial communication, and participation was voluntary. Returning the completed questionnaire was considered as equivalent to giving informed consent to participation in the study.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 28.0. Categorical variables are presented as absolute and relative frequencies, while continuous variables are presented as mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum values. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was applied to assess the normality of distribution for quantitative variables.

For the bivariate analysis, several statistical tests were applied (Independent samples t-test, One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), Pearson’s correlation coefficient, Spearman’s correlation coefficient), depending on the nature of the variables.

To further examine associations and control for confounding variables, multivariable linear regression analysis was performed. Results are expressed as regression coefficients (b), along with 95% confidence intervals and corresponding p-values. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees. Ethical approval was granted by the Research Ethics and Deontology Committee of the University of Peloponnese. Further implementation approval was obtained from the Scientific Council of the 2nd Regional Health Authority of Piraeus and the Aegean.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and anonymity and confidentiality were rigorously maintained throughout the study.

3. Results

A total of 492 registered nurses working in public primary healthcare settings across mainland and insular Greece participated in the study, sharing their views on cultural competence and ethical-deontological attitudes. The results are presented in alignment with the study objectives, covering sociodemographic characteristics, descriptive statistics of cultural competence and ethical knowledge/attitudes, and inferential analyses examining associations among variables.

3.1. Participant Demographics

The mean age of the respondents was 42.2 years (range: 20–66, SD = 9.7), with a median age of 42 years. The majority of participants were female (88.7%) and married or in a civil partnership (64.9%).

In terms of educational background, 77.6% held a degree from a Technological Educational Institute (TEI) or University (AEI), 22.4% were graduates of the two-year basic nursing programs, 26.2% had obtained a postgraduate (Master’s) degree, and 0.8% held a doctoral degree (PhD).

Regarding workplace location, 63.6% of participants were employed in mainland units, while 36.4% worked in island-based healthcare units. Notably, 18.1% were employed in areas with a Reception and Identification Center or a closed-controlled facility under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Migration and Asylum, serving migrant and refugee populations.

The mean years of professional nursing experience was 16 years (SD = 9.9), with a range from 8 months to 40 years and a median of 15 years.

The demographic and professional characteristics of the participants are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Cultural Competence Levels Among Nurses

The Transcultural Self-Efficacy Tool – Greek version (TSET-Gr) demonstrated excellent internal consistency across all subscales. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were:

0.975 for the Cognitive subscale,

0.975 for the Practical subscale, and

0.960 for the Affective subscale,

indicating a high level of reliability for assessing cultural competence among nurses.

The descriptive statistics for each subscale are presented in

Table 2. Higher scores reflect greater self-efficacy in the corresponding domain of cultural competence. Participants reported the highest mean score in the Affective subscale (M = 7.4, SD = 1.3), followed by the Cognitive subscale (M = 7.2, SD = 1.6) and the Practical subscale (M = 6.9, SD = 1.5). In all three domains, the average scores indicate moderate to high levels of perceived transcultural self-efficacy.

An item-level analysis of the Transcultural Self-Efficacy Tool – Greek version (TSET-Gr) offered nuanced insights into specific areas where nurses felt confident or uncertain when delivering culturally responsive care.

In the Cognitive Self-Efficacy subscale, the highest confidence levels were reported in understanding how cultural factors influence care related to hygiene (M = 7.5, SD = 2.1) and health restoration (M = 7.5, SD = 1.9). On the other hand, the lowest confidence levels were observed in items concerning sexuality (M = 7.0, SD = 2.3) and aspects of death, grief, and loss (M = 7.1, SD = 2.3), reflecting some uncertainty when addressing these sensitive and complex areas within culturally diverse contexts.

In the Practical Self-Efficacy subscale, nurses felt most confident when assessing patients’ views on personal space and physical contact (M = 7.4, SD = 1.9) and the role of family in illness (M = 7.1, SD = 1.9). However, lower confidence was reported in engaging with patients on traditional medical practices (M = 6.5, SD = 2.0) and worldviews or life philosophies (M = 6.6, SD = 2.1), highlighting potential challenges in addressing deeper cultural beliefs and traditional health behaviors during clinical interactions.

In the Affective Self-Efficacy subscale, participants expressed strong self-efficacy in being aware of their own biases and limitations (M = 8.4, SD = 1.4) and their cultural heritage and beliefs (M = 8.3, SD = 1.5), as well as in appreciating culturally sensitive care. However, they felt least confident in their awareness of intra-cultural variation within their own culture (M = 5.2, SD = 1.4) and in recognizing the value of traditional home remedies and folk practices (M = 6.0, SD = 2.2). These findings suggest that while affective cultural self-awareness is generally high, there may be gaps in understanding cultural complexity and traditional knowledge systems.

3.3. Knowledge and Attitudes of Nurses About Ethics

The Nurses’ Ethics Questionnaire (NEQ-Gr) evaluated nurses’ experiences, knowledge, and attitudes regarding ethical and legal issues in clinical practice. The results are organized into two main sections: (I) perceptions of ethical/legal challenges and resources, and (II) attitudes toward ethical and bioethical dilemmas. Descriptive findings for key domains are summarized below, with corresponding data about some of them, shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

Section I: Perceptions of Ethical/Legal Challenges and Institutional Support

Most nurses reported facing ethical or legal dilemmas regularly, with 33.1% encountering them monthly and 28.9% weekly. Over 40% indicated that such dilemmas moderately complicated their clinical practice. Nearly half the sample reported being at least occasionally required to perform actions that conflicted with their ethical or legal views.

The mean ethical knowledge score was 2.4 (SD = 0.9) out of 4, reflecting moderate awareness of core ethical frameworks such as the Hippocratic Oath, the Nuremberg Code, and the Declaration of Helsinki. Knowledge was primarily acquired through workplace experience (74.2%) and formal education (72.2%), with a smaller proportion attributing their learning to self-directed study (38.8%) (

Table 3). Regarding the usefulness of ethical information sources, most nurses found lectures (96.5%) and conferences (95.9%) to be very helpful, followed closely by books (92.7%).

When addressing ethical dilemmas, participants most often sought consultation from colleagues (72.8%) and supervisors (67.3%), while one in four (24.6%) also consulted family or friends. For legal challenges, the top choices were lawyers (70.1%), supervisors (52.2%), and colleagues (44.7%).

Most nurses (72.8%) believed that their workplace should have an Ethics Committee. The most widely endorsed functions of such a committee included advising staff on ethical and legal issues (88.6%), upholding institutional ethical standards (84.1%), and guiding administrative decisions related to ethics and policy (71.7%).

Section II: Ethical and Bioethical Attitudes

Participants’ ethical attitudes were assessed using a 10-item scale, which yielded a mean score of 3.8 (SD = 0.4), with a median of 3.7, a minimum of 2.5, and a maximum of 5.0. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.650, indicating acceptable internal consistency. Most nurses demonstrated strong support for fundamental ethical principles. The majority agreed that patients should always be informed of medical errors (79.5%), should be actively involved in decision-making about their care (75.6%), and should receive full disclosure of their health condition, even when facing serious illness (73.2%).

The second part of this section explored views on controversial bioethical dilemmas (

Table 4). A substantial proportion of nurses (63.0%) opposed the notion that a patient who wishes to die should be assisted, regardless of their illness. On the topic of treatment refusal, 80.7% stated that healthcare professionals should advise patients on the appropriate medical course of action, whereas only 15.7% supported fully respecting the patient’s decision without question. Views on abortion were more divided: 46.5% agreed that a nurse cannot refuse to participate in an abortion when it is legally permitted, 25.0% disagreed, and 28.5% were unsure. In contrast, near consensus was observed on the topic of parental consent for pediatric care, with 79.9% of participants agreeing that children should never be treated without the consent of a parent or guardian, except in emergencies. Finally, just over half (54.2%) disagreed that organ donation should proceed automatically without family consent, while 22.6% supported this policy, and 23.2% remained uncertain.

3.4. Correlations Between Cultural Competence and Knowledge and Attitudes of Nurses About Ethics

To examine the interrelationships among demographic, professional, and outcome variables, a series of bivariate correlations and multivariable linear regression analyses were conducted. The focus was on the three subscales of transcultural self-efficacy (cognitive, practical, affective), as well as ethical knowledge and ethical attitudes. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

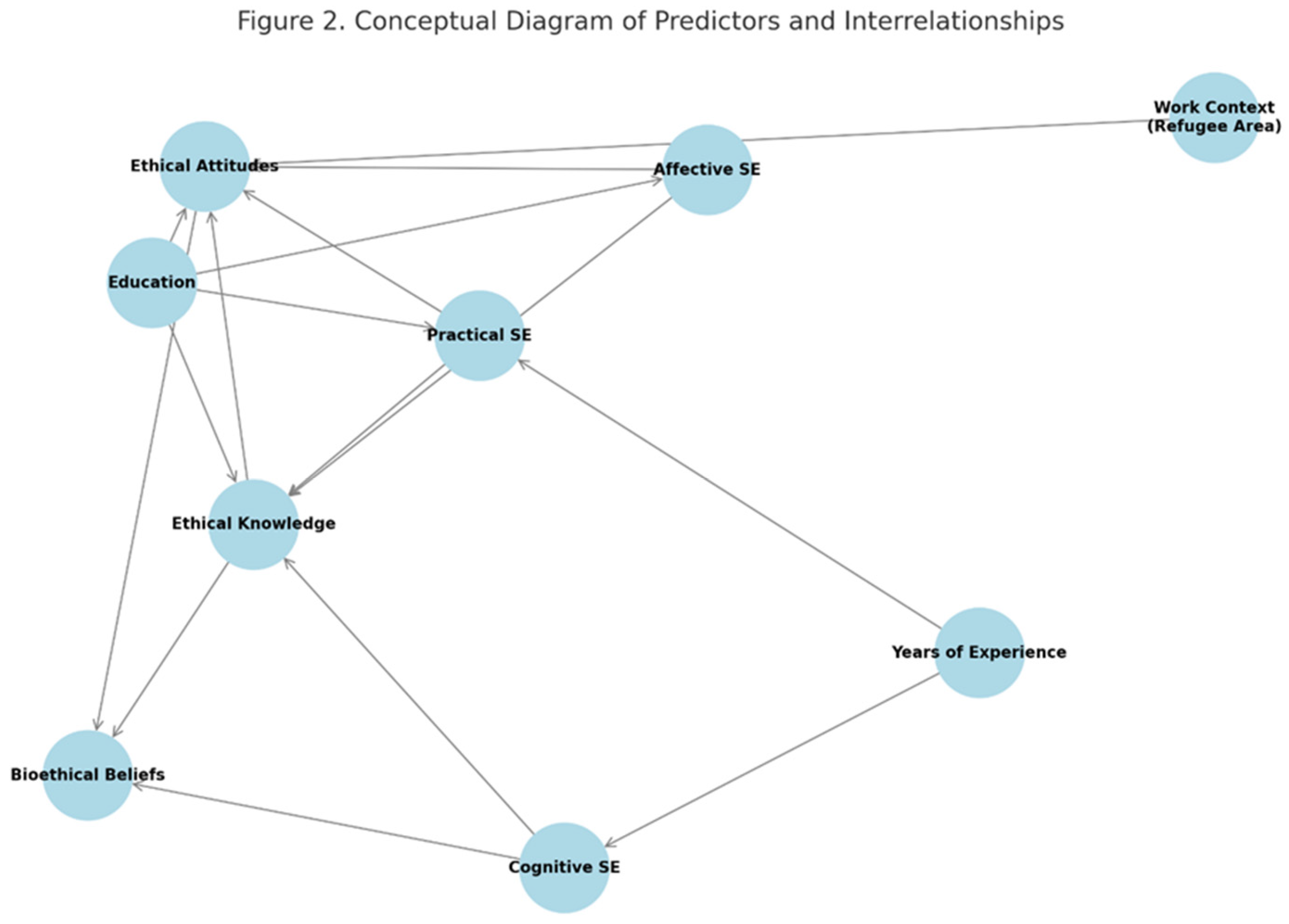

Multivariable linear regression analysis indicated that cognitive self-efficacy was significantly and negatively associated with years of professional experience (b = –0.03, 95% CI: –0.04 to –0.01, p = 0.001). This suggests that nurses with more years in practice reported lower confidence in their knowledge cultural factors influencing care. No other demographic or professional variable showed a statistically significant association with cognitive self-efficacy.

In terms of practical self-efficacy, two significant predictors emerged. A negative relationship was observed with years of experience (b = –0.02, 95% CI: –0.03 to –0.007, p = 0.003), indicating that more experienced nurses expressed less confidence in culturally sensitive communication and patient interaction. Conversely, educational level was positively associated with practical self-efficacy (b = 0.12, 95% CI: 0.002 to 0.24, p = 0.045), implying that higher education enhanced perceived competency in conducting culturally sensitive nursing interviews.

Affective self-efficacy, which reflects attitudinal and emotional readiness to provide culturally appropriate care, was significantly predicted by educational level alone (b = 0.15, 95% CI: 0.06 to 0.25, p = 0.002). Nurses with higher academic qualifications were more likely to report greater affective self-efficacy, indicating stronger cultural acceptance, empathy, and advocacy.

With respect to ethical outcomes, ethical attitudes were significantly influenced by two factors. First, educational level was positively associated with more favorable ethical attitudes (b = 0.03, CI: 0. 001 to 0.07, p = 0.048). Second, working in a region that hosts a Refugee Reception or Closed-Controlled Structure was also a strong predictor (b = 0.18, CI: 0. 09 to 0.28, p < 0.001). These findings suggest that both formal education and multicultural work environments enhance nurses’ ethical sensitivity and perspectives in clinical settings.

Ethical knowledge, as measured by awareness of key ethical and legal frameworks, was significantly associated with educational level (b = 0.10, 95% CI: 0.02 to 0.17, p = 0.014), further supporting the critical role of academic preparation in the development of ethical competency among nursing professionals.

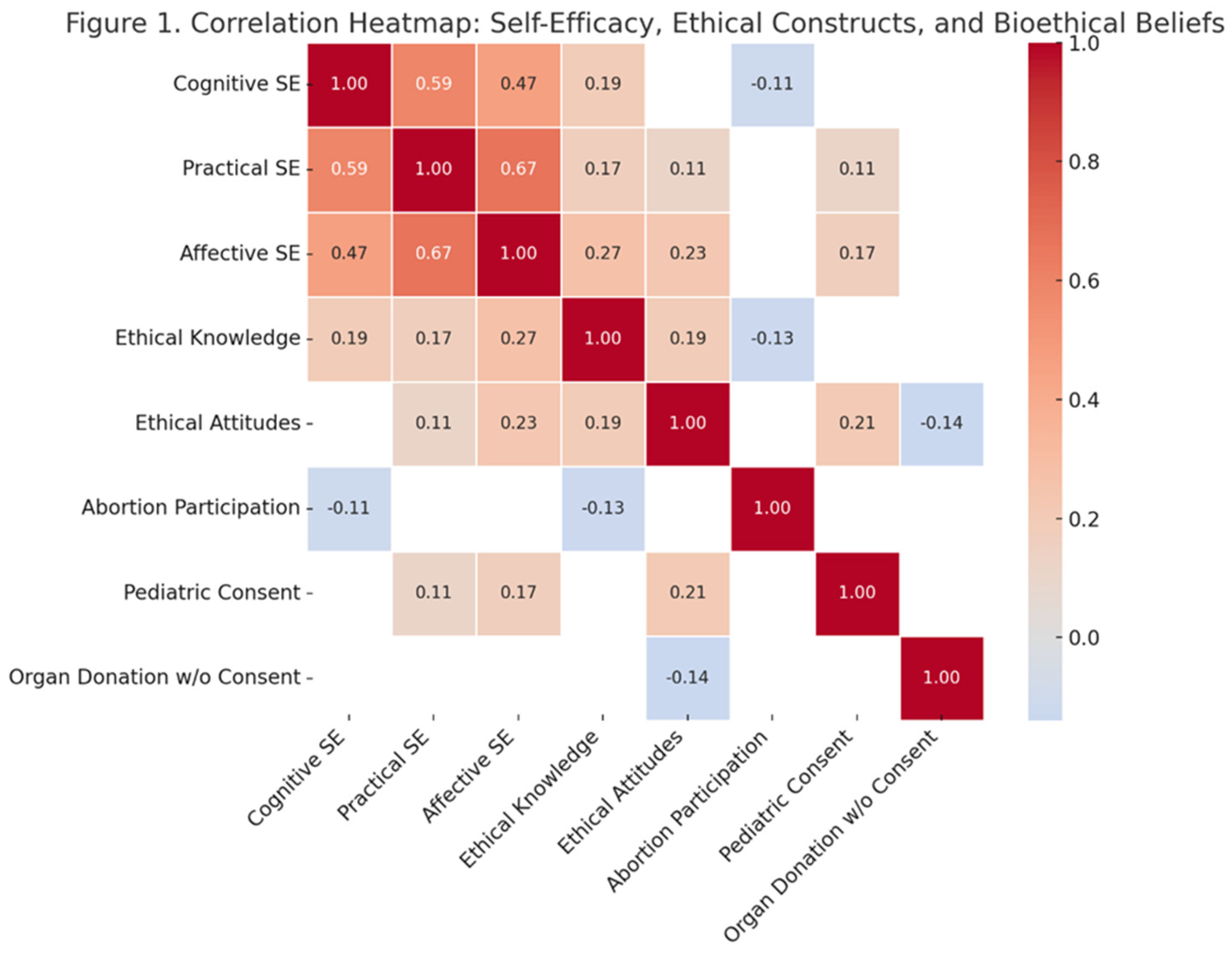

Pearson’s correlation analysis revealed statistically significant interrelations among some of the study’s primary variables as shown in

Table 5. There were strong positive associations between all three subscales of transcultural self-efficacy. Specifically, cognitive and practical self-efficacy were strongly correlated (r = 0.59, p < 0.001), as were practical and affective self-efficacy (r = 0.67, p < 0.001), and cognitive and affective self-efficacy (r = 0.47, p < 0.001).

Beyond internal self-efficacy dimensions, further associations were observed with ethical constructs. Cognitive self-efficacy was positively correlated with ethical knowledge (r = 0.19, p < 0.001), while practical self-efficacy was positively associated with both ethical attitudes (r = 0.11, p = 0.02) and ethical knowledge (r = 0.17, p < 0.001). Likewise, affective self-efficacy correlated positively with ethical attitudes (r = 0.23, p < 0.001) and ethical knowledge (r = 0.27, p < 0.001). Finally, ethical knowledge and ethical attitudes themselves were also positively related (r = 0.19, p < 0.001), indicating a consistent pattern of alignment between nurses’ knowledge and their moral perspectives.

Table 5.

Correlations Between Core Study Variables.

Table 5.

Correlations Between Core Study Variables.

| |

PracticalSelf-Efficacy |

AffectiveSelf-Efficacy |

Ethical Attitudes |

Ethical Knowledge |

| |

Pearson’s r |

p-Value |

Pearson’s r |

p-Value |

Pearson’s r |

p-Value |

Pearson’s r |

p-Value |

| Cognitive Self-Efficacy |

0.59 |

<0.001 |

0.47 |

<0.001 |

0.03 |

0.54 |

0.19 |

<0.001 |

Practical

Self-Efficacy |

|

|

0.67 |

<0.001 |

0.11 |

0.02 |

0.17 |

<0.001 |

| Affective Self-Efficacy |

|

|

|

|

0.23 |

<0.001 |

0.27 |

<0.001 |

Ethical

Attitudes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.19 |

<0.001 |

Further analysis of ethical practice variables revealed that cognitive self-efficacy was weakly but significantly associated with the frequency of ethical conflict with colleagues (r = 0.09, p = 0.04), suggesting that those more confident in their cultural knowledge may also be more likely to experience interpersonal ethical tensions. Additionally, ethical attitudes were positively correlated with the perceived importance of ethics in clinical decision-making (r = 0.10, p = 0.03), indicating that more ethically inclined nurses place greater value on moral considerations in daily care.

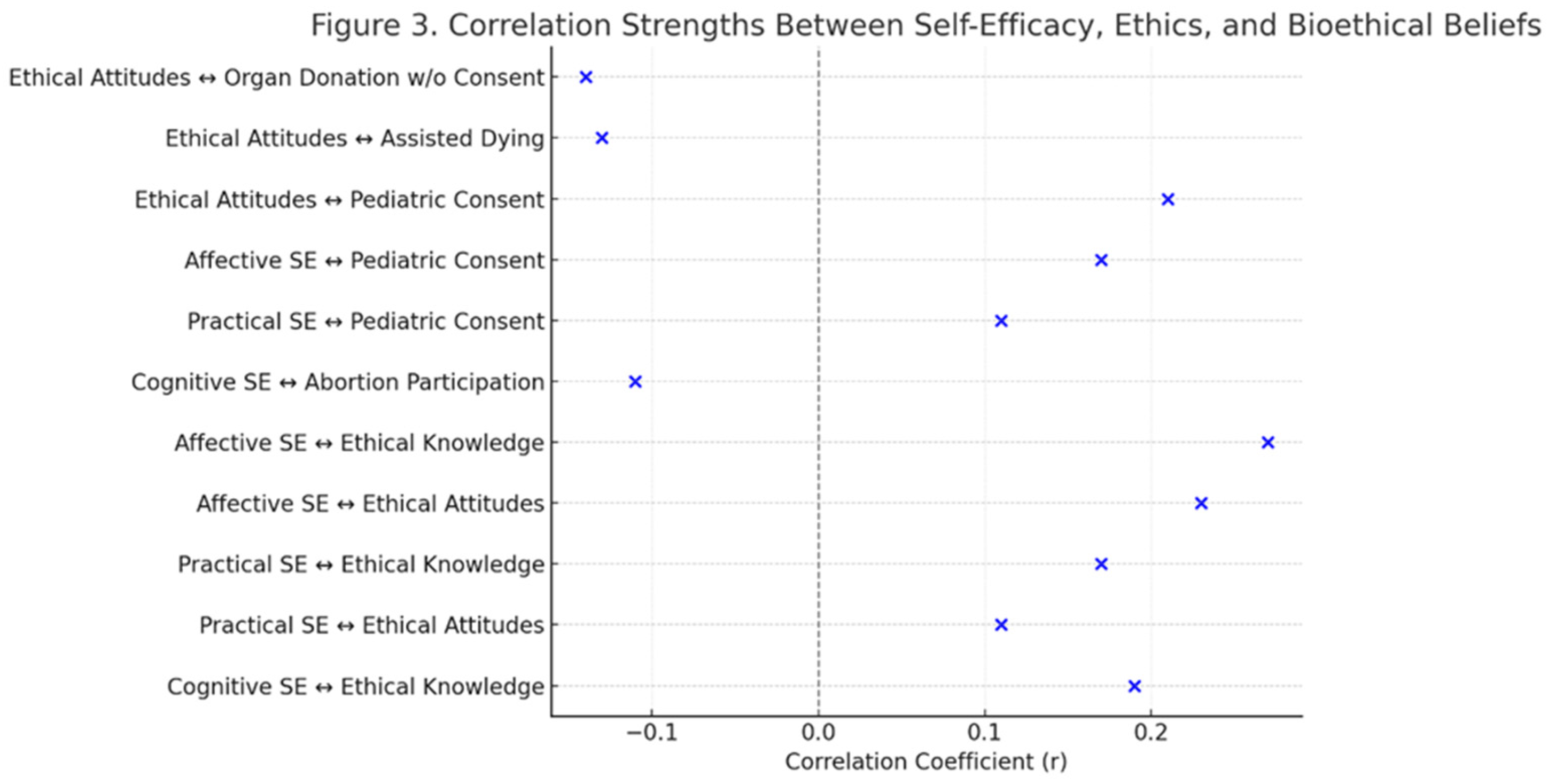

Spearman’s correlations showed a range of statistically significant associations between the core variables and participants’ responses to controversial bioethical dilemmas.

Notably, higher cognitive self-efficacy was negatively associated with agreement that nurses must participate in abortion procedures when legally permitted (r = –0.11, p = 0.02), as was ethical knowledge (r = –0.13, p = 0.004). This suggests that greater ethical awareness and cultural confidence may be linked to stronger endorsement of conscientious objection.

Conversely, nurses with higher practical and affective self-efficacy, and more positive ethical attitudes, were significantly more likely to support the necessity of parental consent for pediatric care, with correlation coefficients of r = 0.11, r = 0.17, and r = 0.21, respectively (p < 0.001 in all cases). These findings reflect a shared commitment to safeguarding minors’ rights through appropriate legal and ethical procedures.

Moreover, ethical attitudes were significantly negatively correlated with support for assisted dying (r = –0.13, p = 0.004), and with acceptance of organ donation without familial consent (r = –0.14, p = 0.002), indicating that stronger ethical stances among nurses may align with more conservative bioethical values in these domains.

To further illustrate the key interrelationships among the study variables, a correlation heatmap (

Figure 1), a conceptual diagram of statistically significant predictors and pathways (

Figure 2), and a summary plot of effect sizes (

Figure 3) are presented below.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to explore the interrelationship between cultural competence and ethical decision-making among nurses working in primary healthcare settings across Greece. Specifically, it sought to assess the levels of transcultural self-efficacy among nurses and their knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to ethical and legal issues. It further examined how these dimensions interact and whether specific demographic or professional factors—such as education, years of experience, or multicultural work environments—influence these constructs. In doing so, the study addresses a critical gap in the literature regarding the integrated role of cultural competence and ethical awareness in nursing care delivery.

The findings of this study offer a nuanced view of how cultural competence and ethical understanding coexist and influence each other in the everyday work of nurses in Greece’s primary healthcare system. At the heart of the results is the observation that the three components of transcultural self-efficacy—cognitive, practical, and affective—are not only distinct but also closely interconnected. This supports the idea that being culturally competent is not just about knowing facts or protocols; it also requires having the communication skills and emotional awareness to navigate cultural differences effectively. This pattern echoes what Bandura [

37,

38] describes in his self-efficacy theory: confidence in one area tends to reinforce competence in other related areas.

This is also consistent with models proposed by scholars such as Papadopoulos [

39], who argued that effective transcultural care relies on a balanced development of knowledge, skills, and emotional sensitivity. The strength of the associations among these domains in our study suggests that training interventions aimed at one dimension are likely to enhance the others—a claim supported by previous evaluations of cross-cultural nursing curricula [

40]. This multidimensional effect of educational interventions is further emphasized by Leyva-Moral et al. [

41], who found that transcultural learning experiences among nursing students lead not only to increased cultural knowledge but also to profound changes in attitudes, self-awareness, and interpersonal skills—highlighting the integrative impact of well-designed curricula.

The inverse relationship we observed between years of clinical experience and cognitive/practical self-efficacy is particularly noteworthy. Interestingly, nurses with more years of professional experience tended to report lower levels of confidence in their cultural knowledge and practical skills. This finding diverges from the assumption that clinical experience naturally enhances all forms of competence. While the relationship might seem surprising, it’s likely a reflection of evolving educational content. Nurses trained more recently may have had better exposure to topics like multicultural care and health equity, which have gained prominence in recent decades [

6,

42,

43]. In contrast, nurses who entered the profession earlier may not have had formal training on these issues, highlighting the importance of lifelong learning. This suggests that unless supported by continuous professional development, prolonged clinical exposure may not guarantee increased confidence in cross-cultural communication. On the other hand, education—particularly at higher academic levels—was consistently linked with better self-assessed competence, especially in practical and affective domains. This aligns with existing evidence showing that advanced education contributes not only to clinical skills but also to ethical reasoning and intercultural communication [

39,

40,

44].

Other researchers further support these findings. For instance, Sharma et al. [

45] found that healthcare professionals and trainees with more extensive formal education in India reported significantly higher preparedness in addressing the needs of sexual and gender minority patients.

Ethical outcomes in this study were similarly shaped by both education and work environment. Recent studies have shown that structured educational interventions significantly improve nurses’ ethical sensitivity, decision-making, and advocacy behaviors. For instance, Su et al. [

46] found that ethics education enhanced nursing students’ capacity for patient advocacy, while Ishihara et al. [

47] reported that such training increased nurses’ moral efficacy and confidence in managing ethical challenges in acute care settings. Milliken and Grace [

48] emphasize that when nursing curricula intentionally include ethics as an integral component, nurses are more likely to engage thoughtfully with ethical issues and act with greater moral clarity in their professional roles. These findings support the view that ethical competence is not solely intuitive but can be cultivated through targeted educational strategies. Regarding the effect of the work environment, we found that nurses working in refugee-hosting or multicultural areas showed stronger ethical attitudes. Exposure to diverse populations may challenge practitioners to think more deeply about values, fairness, and patient rights. Kotrotsiou et al. [

49], similarly observed that Greek nursing students demonstrated higher levels of cultural competence when interacting with patients from various cultural backgrounds, indicating that such exposure enhances nurses’ ethical awareness and sensitivity. Ünsal et al. [

50] came to a similar conclusion in their study of Turkish nurses caring for displaced populations after natural disasters, where navigating linguistic and religious differences required a blend of emotional intelligence and ethical reasoning.

What stood out particularly was the strong link between affective self-efficacy—the ability to emotionally engage with patients from different backgrounds—and ethical sensitivity. Nurses who felt more confident about their cultural empathy and open-mindedness were also more likely to demonstrate strong ethical awareness. This suggests that empathy and cultural openness may serve as important bridges between competence and moral action [

42]. Affective empathy plays a crucial role in the moral reasoning and ethical decision-making processes of healthcare providers, especially in intercultural contexts. Studies have shown that healthcare professionals who exhibit higher levels of affective empathy are better equipped to navigate complex moral dilemmas and foster effective communication across diverse cultural settings. This ability is paramount in healthcare, where understanding patients’ emotional states can significantly improve patient-provider interactions and overall health outcomes. Jeon and Choi [

51] discuss the importance of empathy in healthcare settings, emphasizing that the emotional aspect of empathy, particularly affective empathy, enables practitioners to connect with patients on a deeper psychological level. They argue that while cognitive empathy involves understanding another’s feelings intellectually, affective empathy allows healthcare providers to share and resonate with patients’ emotional experiences. This emotional connection is crucial in fostering patient-centered care, which can enhance patient satisfaction and treatment adherence.

The results also shed light on how cultural and ethical orientations shape nurses’ opinions on controversial bioethical issues. For instance, nurses with higher cognitive self-efficacy and greater knowledge of ethical standards were less likely to support mandatory involvement in abortion procedures, perhaps reflecting a stronger alignment with professional autonomy and the right to conscientious objection. This aligns with the findings of Krawutschke et al [

52] who supports that nurses who object to abortion often see mandatory referrals as complicity in actions they morally oppose, thereby reinforcing their alignment with professional autonomy. Conversely, those with stronger affective and practical cultural competence tended to support parental consent in pediatric care—emphasizing the importance of family involvement and legal safeguards in vulnerable situations. Guarda-Rodrigues [

53] also discusses how culturally competent practices promote parental empowerment and enhance the quality of nursing care.

In more ethically complex areas such as assisted dying and organ donation without consent, those with higher ethical attitudes expressed more cautious views, opposing both practices. These positions may reflect an emphasis on informed consent, patient dignity, and moral responsibility, which are central values in nursing ethics globally [

54]. Similarly, a 2023 study by Dörmann et al. [

55] explored professional nursing views on assisted suicide in Germany. The study highlighted that nurses’ attitudes are shaped by their ability to understand patients’ wishes, personal values, and ethical concerns, leading many to adopt a cautious stance toward assisted suicide.

Additionally, our results contribute to the literature on moral distress and the ethical climate in healthcare institutions. The correlation between cognitive self-efficacy and conflicts with colleagues over ethical issues is an important area of study, especially in ethically diverse environments. Nurses, as ethically aware practitioners, may experience increased tension within rigid or homogeneous teams. This phenomenon highlights how divergent ethical perspectives can create friction, particularly in settings that lack cultural competence alongside ethical awareness. These conflicts may not indicate a deficiency, but rather a heightened moral awareness—a theme that warrants further investigation. Ethical leadership fosters an environment where ethical concerns can be voiced without fear of reprisal. Elhihi et al. [

56] found that ethical leadership significantly impacted nurses’ error reporting behavior and moral courage. Their study demonstrated that moral courage partially mediated the relationship between ethical leadership and error reporting, suggesting that leaders promoting an ethical culture can help mitigate conflicts arising from differing ethical viewpoints. This implies that teams lacking strong ethical leadership may struggle with navigating conflicts effectively.

5. Implications for Nursing Practice

This study underscores the pressing need for continuous professional development in cultural competence. Findings revealed that longer years of clinical experience were associated with decreased confidence in both cognitive and practical aspects of transcultural care, suggesting that routine exposure alone is insufficient. Regular training, mentorship, and reflective practice are essential to sustain culturally competent and ethically sound nursing over time.

Healthcare institutions also play a critical role in fostering an environment where ethical and culturally competent care can flourish. Providing structured opportunities—such as ethics committees, simulation-based learning, and interdisciplinary workshops—can help nurses navigate complex ethical dilemmas while remaining sensitive to cultural diversity.

At the policy level, results support the integration of comprehensive cultural competence and healthcare ethics training into nursing education. Curricula at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels should include evidence-based content on intercultural communication, ethical reasoning, and diversity-sensitive care. This alignment between education, institutional practice, and continuing development is vital for ensuring equity, respect, and quality in patient care across diverse populations.

6. Limitations of the Study

This study has a few limitations that warrant consideration. First, the use of self-reported questionnaires may have introduced social desirability bias, whereby participants may have portrayed themselves as more culturally competent or ethically aware than they truly are in practice. While validated tools such as the TSET-Gr and NEQ-Gr were used, these instruments assess perceptions rather than observable behaviors, potentially limiting the objectivity of the findings.

Second, the study population consisted exclusively of nurses working in primary healthcare settings in Greece, which restricts the generalizability of the findings to other settings, professions, or cultural contexts. Ethical and cultural practices are shaped by national policies, societal values, and workplace norms, which may differ considerably in other countries or sectors of care.

Third, the study did not assess actual clinical behavior or outcomes, focusing instead on perceived self-efficacy and attitudes. As such, it cannot confirm whether higher self-reported competence translates into culturally sensitive or ethically sound clinical actions.

7. Conclusions

This study sheds light on how nurses in Greece navigate the intertwined challenges of providing culturally competent and ethically sound care in today’s diverse healthcare settings. The findings suggest that while most nurses feel reasonably confident in their cultural understanding and moral responsibilities, there are important differences based on factors like education and work experience.

What stood out most clearly was the link between empathy—especially emotional openness to cultural difference—and ethical awareness. Nurses who felt more emotionally prepared to engage with patients from various backgrounds also showed stronger ethical perspectives. This reinforces the idea that being a culturally sensitive nurse isn’t just about knowledge; it’s about genuinely connecting with patients and understanding their values.

Educational background played a key role across the board. Those with higher academic qualifications tended to report greater confidence in their ability to communicate across cultures and make ethically grounded decisions. On the other hand, nurses with more years of experience often reported lower confidence in some cultural competencies, perhaps reflecting the need for continuous learning and updated training in a rapidly evolving field.

Working in multicultural environments also made a difference. Nurses in regions that host refugee or migrant populations showed stronger ethical attitudes, likely because daily encounters with cultural difference can sharpen one’s ethical lens and promote more inclusive thinking.

Taken together, these results point to a clear takeaway: cultural competence and ethics are not separate skill sets—they are deeply connected. Being prepared to care for people from different backgrounds requires both an understanding of cultural contexts and the ethical insight to respond with sensitivity and fairness.

To strengthen these skills, healthcare systems must take action. Ongoing professional development in cultural competence should be a priority, supported by institutional policies and practices. Nursing curricula should integrate ethics and cultural sensitivity as core competencies, not just optional add-ons.

In an era of increasing diversity, ensuring that nurses are both ethically grounded and culturally responsive is not just a professional obligation—it’s a matter of compassionate, high-quality care.

8. Recommendations for Future Research and Practice

This study highlights how closely linked cultural competence and ethical sensitivity are in nursing. However, more work is needed to fully understand and support this connection in everyday clinical practice.

Future research should explore how these skills evolve over time, especially as nurses gain experience. Our findings suggest that confidence in culturally competent care may decline without regular reinforcement. Longitudinal studies could help explain why this happens and how to prevent it.

There is also a need for research on what types of education or training are most effective. Not all learning experiences are equal—identifying what works best could help educators and institutions design stronger programs. Qualitative studies could further enrich this understanding by capturing nurses’ personal stories and challenges.

Practically speaking, healthcare institutions have a vital role to play. Ongoing professional development, supportive leadership, and active ethics committees can create environments where ethical and culturally responsive care thrives. Policies should also prioritize these areas by embedding them into nursing curricula and continuing education frameworks.

Finally, expanding this kind of research across different healthcare settings and cultural contexts will help build a more inclusive, evidence-based understanding of what nurses need to care for all patients with empathy, respect, and ethical clarity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.T. and F.T.; methodology, F.T.; software, L.T.; validation, L.T., E.C.F. and A.P.; formal analysis, L.T.; investigation, L.T.; resources, L.T.; data curation, L.T.; writing—original draft preparation, L.T.; writing—review and editing, L.T., E.C.F., A.P. and F.T.; visualization, L.T.; supervision, F.T.; project administration, F.T.; funding acquisition, L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by L.T.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to technical/ time limitations. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to L.T.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jaiswal, R.; Gupta, S.; Gupta, S.K. The Impending Disruption of Digital Nomadism: Opportunities, Challenges, and Research Agenda. World Leis. J. 2025, 67, 74–104. [CrossRef]

- Global Trends Report 2023 Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/media/global-trends-report-2023 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- ICN_PHC-Report-2024_EN_FINAL.Pdf.

- Tosam, M.J. Global Bioethics and Respect for Cultural Diversity: How Do We Avoid Moral Relativism and Moral Imperialism? Med. Health Care Philos. 2020, 23, 611–620.

-

Handbook for Culturally Competent Care; Fenkl, E.A., Purnell, L.D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2024; ISBN 978-3-031-70491-8.

- Douglas, M.K.; Rosenkoetter, M.; Pacquiao, D.F.; Callister, L.C.; Hattar-Pollara, M.; Lauderdale, J.; Milstead, J.; Nardi, D.; Purnell, L. Guidelines for Implementing Culturally Competent Nursing Care. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2014, 25, 109–121. [CrossRef]

- Truong, M.; Paradies, Y.; Priest, N. Interventions to Improve Cultural Competency in Healthcare: A Systematic Review of Reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 99.

- Campinha-Bacote, J. The Process of Cultural Competence in the Delivery of Healthcare Services: A Model of Care. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2002, 13, 181–184. [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Tian, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, K.; Xiao, X.; Simoni, J.M.; Wang, H. The Influence of Cultural Competence of Nurses on Patient Satisfaction and the Mediating Effect of Patient Trust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 749–759. [CrossRef]

- Jui-Chin, H.; Fen-Fang, C.; Tso-Ying, L.; Pao-Yu, W.; Mei-Hsiang, L. Exploring the Care Experiences of Hemodialysis Nurses: From the Cultural Sensitivity Approach. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23. [CrossRef]

- Mihu, L.; Marques, R.M.D.; Pontifice Sousa, P. Strategies for Nursing Care of Critically Ill Multicultural Patients: A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 3468–3476. [CrossRef]

- Reeves, K.; Job, S.; Blackwell, C.; Sanchez, K.; Carter, S.; Taliaferro, L. Provider Cultural Competence and Humility in Healthcare Interactions with Transgender and Nonbinary Young Adults. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2024, 56, 18–30. [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, J.R.; Corbett, J.; Bondaryk, M.R. Addressing Disparities and Achieving Equity: Cultural Competence, Ethics, and Health-Care Transformation. Chest 2014, 145, 143–148.

- Spurlark, R.S.; Akintade, B.; Broholm, C.; Clark, R.; Fyle-Thorpe, O.; Gatewood, E.; Graves, S.; Kuster, A.; Mihaly, L.; Mitchell, S.; et al. Advanced Practice Nursing Education: Strategies to Advance Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging. J. Nurs. Educ. 2025, 1–5. [CrossRef]

-

Refugee and Migrant Health: Global Competency Standards for Health Workers; 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2021; ISBN 978-92-4-003062-6.

-

Promoting the Health of Refugees and Migrants: Experiences from Around the World; 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2023; ISBN 978-92-4-006711-0.

- McDermott-Levy, R.; Leffers, J.; Mayaka, J. Ethical Principles and Guidelines of Global Health Nursing Practice. Nurs. Outlook 2018, 66, 473–481.

- Usberg, G.; Uibu, E.; Urban, R.; Kangasniemi, M. Ethical Conflicts in Nursing: An Interview Study. Nurs. Ethics 2021, 28, 230–241. [CrossRef]

- Alarabi, A.A.; Alamri, A.A.; Jumah, S.A.; Aljohani, W.M.; Mohammed, A.; Badarb, A.M.B. The Impact of Cultural Beliefs on Medical Ethics and Patient Care. 2024.

- Naramore, R.; Marquez, E. A Choice Not to Choose: Respecting Patient Autonomy in Collectivist Cultures. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2024, 67, e636.

- Alanazi, M.A.; Shaban, M.M.; Ramadan, O.M.E.; Zaky, M.E.; Mohammed, H.H.; Amer, F.G.M.; Shaban, M. Navigating End-of-Life Decision-Making in Nursing: A Systematic Review of Ethical Challenges and Palliative Care Practices. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23. [CrossRef]

- Linnard-Palmer, L.; Kools, S. Parents’ Refusal of Medical Treatment for Cultural or Religious Beliefs: An Ethnographic Study of Health Care Professionals’ Experiences. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2005, 22, 48–57.

- Neuberg, M.; Sopić, D.; Košanski, T.; Grabant, M.K.; Ribić, R.; Meštrović, T. Gender Bias and Perceptions of the Nursing Profession in Croatia: A Cross-Sectional Study Comparing Patients and the General Population. SAGE Open Nurs. 2024, 10, 23779608241271653.

- Theodosopoulos, L.; Fradelos, E.C.; Panagiotou, A.; Dreliozi, A.; Tzavella, F. Delivering Culturally Competent Care to Migrants by Healthcare Personnel: A Crucial Aspect of Delivering Culturally Sensitive Care. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 530.

- Choi, P.P. Patient Advocacy: The Role of the Nurse. Nurs. Stand. 2014 2015, 29, 52.

- Markey, K. Moral Reasoning as a Catalyst for Cultural Competence and Culturally Responsive Care. Nurs. Philos. 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, E.H.; Tallman, B.A. The Impact of Nurses’ Beliefs, Attitudes, and Cultural Sensitivity on the Management of Patient Pain. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2022, 33, 624–631.

- Borowski, D.; Koreik, U.; Ohm, U.; Riemer, C.; Rahe-Meyer, N. Informed Consent at Stake? Language Barriers in Medical Interactions with Immigrant Anaesthetists: A Conversation Analytical Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19. [CrossRef]

- Marcelin, J.R.; Siraj, D.S.; Victor, R.; Kotadia, S.; Maldonado, Y.A. The Impact of Unconscious Bias in Healthcare: How to Recognize and Mitigate It. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 220, S62–S73.

- Sarafis, P.; Michael, I.; Chara, T.; Maria, M. Reliability and Validity of the Transcultural Self-Efficacy Tool Questionnaire (Greek Version). J. Nurs. Meas. 2014, 22.

- Jeffreys, M.R.; Smodlaka, I. Steps of the Instrument Design Process: An Illustrative Approach for Nurse Educators. Nurse Educ. 1996, 21, 47–52.

- Jeffreys, M.R.; Smodlaka, I. Exploring the Factorial Composition of the Transcultural Self-Efficacy Tool. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 1998, 35, 217–225.

- Jeffreys, M.R. Development and Psychometric Evaluation of the Transcultural Self-Efficacy Tool: A Synthesis of Findings. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2000, 11, 127–136. [CrossRef]

- Jeffreys, M.R. The Cultural Competence Education Resource Toolkit 2016.

- Toska, A.; Latsou, D.; Saridi, M.; Sarafis, P.; Souliotis, K. The Validity and Reliability of a Questionnaire on the Knowledge and Attitudes of Nurses about Ethics.

- Hariharan, S.; Jonnalagadda, R.; Walrond, E.; Moseley, H. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice of Healthcare Ethics and Law among Doctors and Nurses in Barbados. BMC Med. Ethics 2006, 7. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Macmillan, 1997;

- Bandura, A. On the Functional Properties of Perceived Self-Efficacy Revisited. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 9–44. [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, I. The Papadopoulos, Tilki and Taylor Model of Developing Cultural Competence. Transcult. Health Soc. Care Dev. Cult. Competent Pract. 2006, 7–24.

- Kaihlanen, A.-M.; Hietapakka, L.; Heponiemi, T. Increasing Cultural Awareness: Qualitative Study of Nurses’ Perceptions about Cultural Competence Training. BMC Nurs. 2019, 18, 38.

- Leyva-Moral, J.M.; Tosun, B.; Gómez-Ibáñez, R.; Navarrete, L.; Yava, A.; Aguayo-González, M.; Dirgar, E.; Checa-Jiménez, C.; Bernabeu-Tamayo, M.D. From a Learning Opportunity to a Conscious Multidimensional Change: A Metasynthesis of Transcultural Learning Experiences among Nursing Students. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22. [CrossRef]

- Jeffreys, M.R. Teaching Cultural Competence in Nursing and Health Care: Inquiry, Action, and Innovation; Springer Publishing Company, 2015;

- Osmancevic, S.; Großschädl, F.; Lohrmann, C. Cultural Competence among Nursing Students and Nurses Working in Acute Care Settings: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Farokhzadian, J.; Nematollahi, M.; Dehghan Nayeri, N.; Faramarzpour, M. Using a Model to Design, Implement, and Evaluate a Training Program for Improving Cultural Competence among Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Mixed Methods Study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Mohlia, A.; Kukreti, P.; Saurabh; Kataria, D. Sexual and Gender Minority Health Care Issues Related Competence and Preparedness Among the Health Care Professionals and Trainees in India: A Comparative Study. J. Psychosexual Health 2024, 6, 338–347.

- Su, S.; Basit, G.; Demirören, N.; Alabay, K.N.K. Impact of Ethics Education on Nursing Students’ Ethical Sensitivity and Patient Advocacy: A Quasi-Experimental Study. J. Acad. Ethics 2024, 1–13.

- Ishihara, I.; Inagaki, S.; Osawa, A.; Umeda, S.; Hanafusa, Y.; Morita, S.; Maruyama, H. Effects of an Ethics Education Program on Nurses’ Moral Efficacy in an Acute Health Care Facility. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 2207–2215. [CrossRef]

- Milliken, A.; Grace, P. Nurse Ethical Awareness: Understanding the Nature of Everyday Practice. Nurs. Ethics 2017, 24, 517–524. [CrossRef]

- Kotrotsiou, S.; Stathopoulou, A.; Theofanidis, D.; Katsiana, A.; Paralikas, T. Investigation of Cultural Competence in Greek Nursing Students. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2020, 13, 1898.

- Ünsal, B.; Özbudak Arıca, E.; Höbek Akarsu, R. Ethical Issues after the Earthquake in Turkey: A Qualitative Study on Nurses’ Perspectives. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2024.

- Jeon, J.; Choi, S. Factors Influencing Patient-Centeredness among Korean Nursing Students: Empathy and Communication Self-Efficacy. In Proceedings of the Healthcare; MDPI, 2021; Vol. 9, p. 727.

- Krawutschke, R.; Pastrana, T.; Schmitz, D. Conscientious Objection and Barriers to Abortion within a Specific Regional Context - an Expert Interview Study. BMC Med. Ethics 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Guarda-Rodrigues, J.; Dias, M.P.F.C.; Fatela, M.M.R.; Jeremias, C.J.R.; Negreiro, M.P.G.; e Sousa, O.L. Culturally Competent Nursing Care as a Promoter of Parental Empowerment in Neonatal Unit: A Scoping Review. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2025, 31, 31–38.

- ICN_Code-of-Ethics_EN_Web.Pdf.

- Dörmann, L.; Nauck, F.; Wolf-Ostermann, K.; Stanze, H. “I Should at Least Have the Feeling That It […] Really Comes from Within”: Professional Nursing Views on Assisted Suicide. Palliat. Med. Rep. 2023, 4, 175–184. [CrossRef]

- Elhihi, E.A.; Aljarary, K.L.; Alahmadi, M.; Adam, J.B.; Almwualllad, O.A.; Hawsawei, M.S.; Hamza, A.A.; Ibrahim, I.A. The Mediating Role of Moral Courage in the Relationship between Ethical Leadership and Error Reporting Behavior among Nurses in Saudi Arabia: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).