Submitted:

24 July 2025

Posted:

28 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

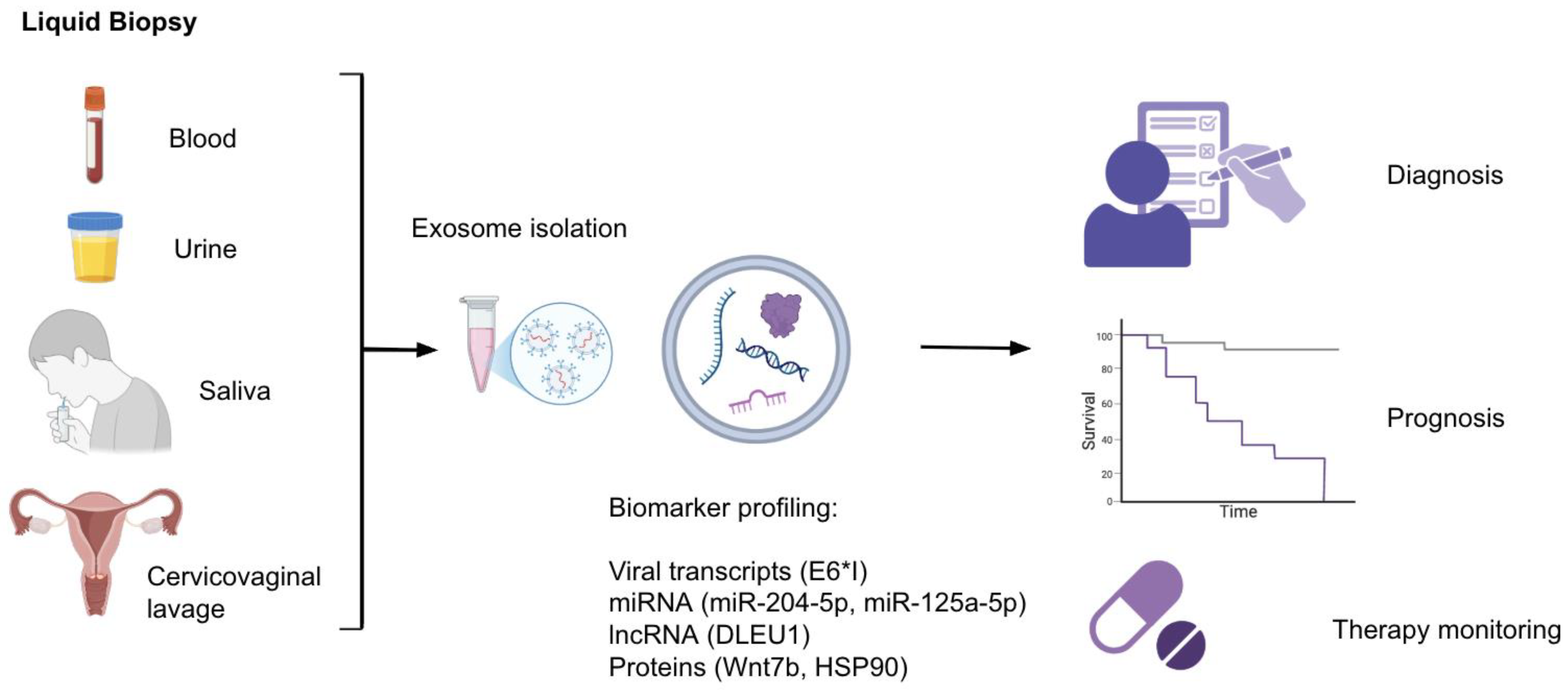

2. Exosomes and Liquid Biopsy: Diagnostic and Prognostic Applications

2.1. Exosomal Nucleic Acids

2.2. Exosomal Protein Biomarkers

2.3. Exosomal Long Non-Coding RNAs

2.4. Monitoring of Treatment Response

3. Exosome-Related Therapies

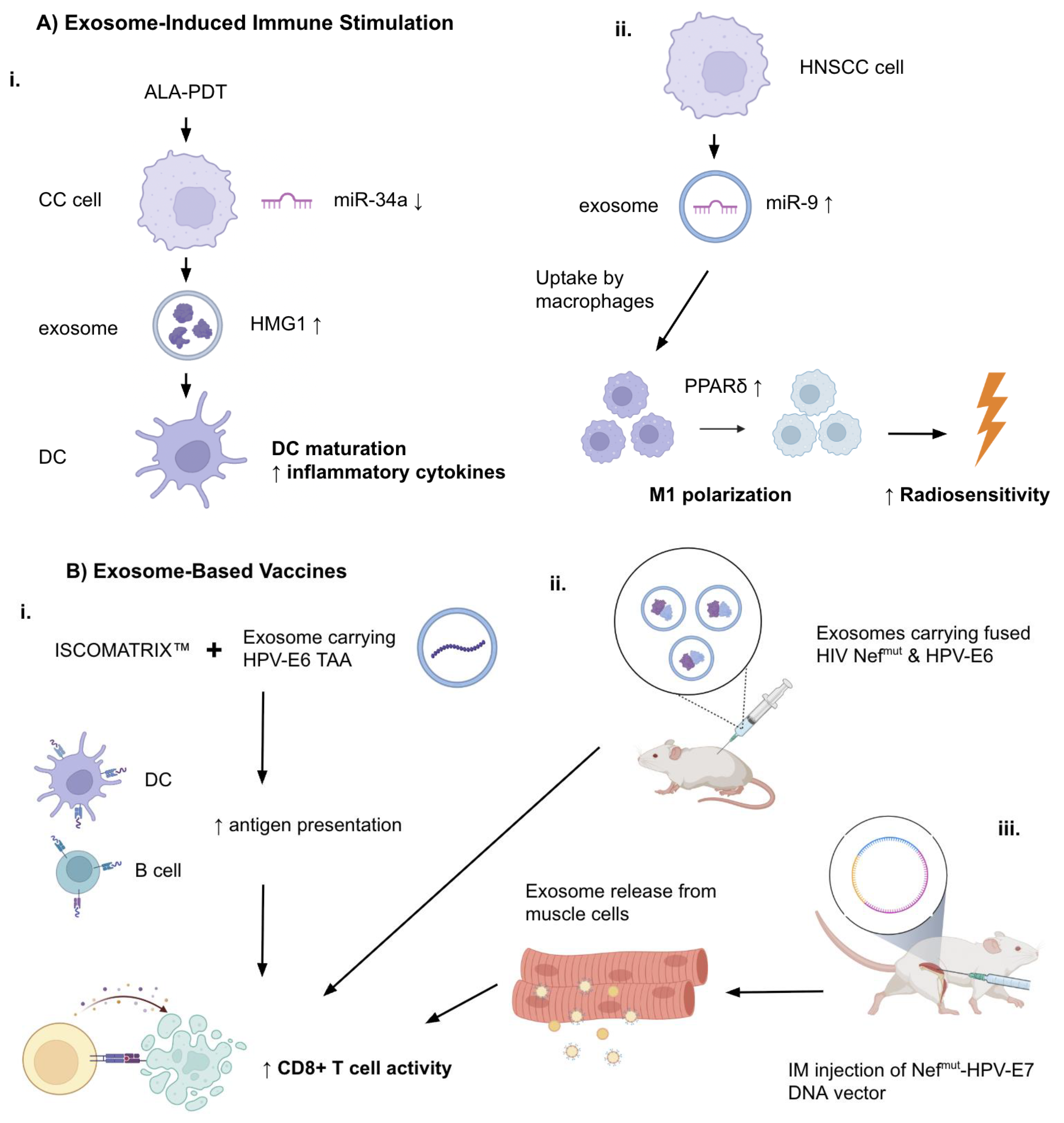

3.1. Exosome-Induced Immune Stimulation

3.2. Exosome-Based Vaccines

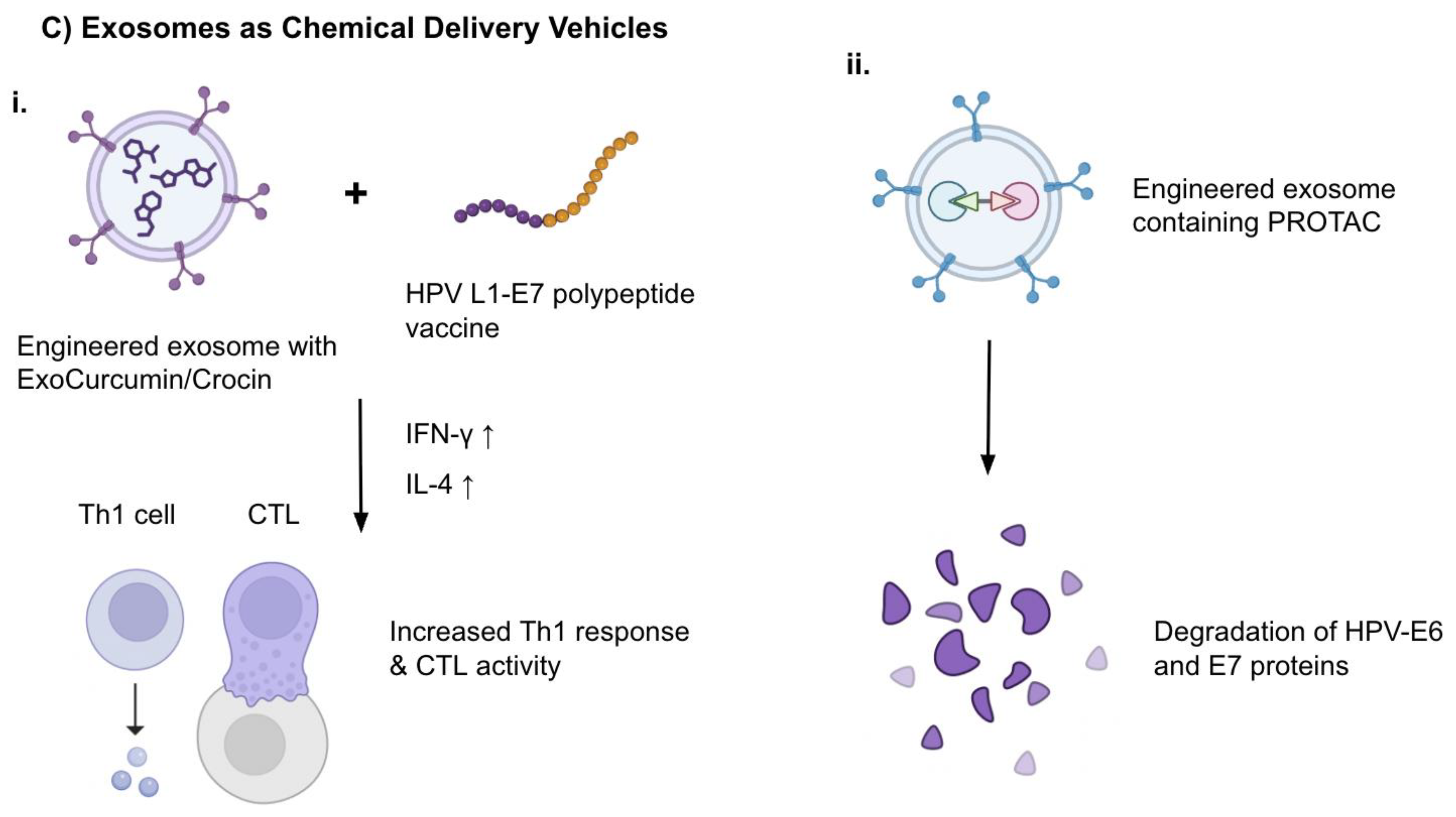

3.3. Exosomes as Drug Delivery Vehicles

3.4. Engineered Exosomes: PROTACs and Targeting Strategies

3.5. Exosomes and Therapy Resistance

4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| ALA-PDT CC CSC CTL EV |

5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy Cervical cancer Cancer stem cell Cytotoxic T lymphocyte Extracellular vesicle |

| HNSCC HPV |

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma Human papillomavirus |

| OPC | Oropharyngeal carcinoma |

| PROTAC TME TSC |

Proteolysis-targeting chimera Tumor microenvironment Tongue squamous cell carcinoma |

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Cancers Caused by HPV.” Human Papillomavirus (HPV), Available online: www.cdc.gov/hpv/about/cancers-caused-by-hpv.html. (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Bray, F., Ferlay, J., Soerjomataram, I., Siegel, R. L., Torre, L. A., & Jemal, A. (2018). Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 68(6), 394–424. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. “Cervical Cancer.” Available online: www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer. (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Kuang, L., Wu, L., & Li, Y. (2025). Extracellular vesicles in tumor immunity: mechanisms and novel insights. Molecular Cancer, 24(1), BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. F., Luh, F., Ho, Y. S., & Yen, Y. (2024). Exosomes: a review of biologic function, diagnostic and targeted therapy applications, and clinical trials. In Journal of Biomedical Science (Vol. 31, Issue 1). BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Zeringer, E., Barta, T., Schageman, J., Cheng, A., & Vlassov, A. v. (2014). Analysis of the RNA content of the exosomes derived from blood serum and urine and its potential as biomarkers. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1652). [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Yi, M., Dong, B., Tan, X., Luo, S., & Wu, K. (2021). The role of exosomes in liquid biopsy for cancer diagnosis and prognosis prediction. In International Journal of Cancer (Vol. 148, Issue 11, pp. 2640–2651). John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Mó, M., Siljander, P. R. M., Andreu, Z., Zavec, A. B., Borràs, F. E., Buzas, E. I., Buzas, K., Casal, E., Cappello, F., Carvalho, J., Colás, E., Cordeiro-Da Silva, A., Fais, S., Falcon-Perez, J. M., Ghobrial, I. M., Giebel, B., Gimona, M., Graner, M., Gursel, I., … de Wever, O. (2015). Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. In Journal of Extracellular Vesicles (Vol. 4, Issue 2015, pp. 1–60). Co-Action Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Qiao, D., Chen, L., Xu, M., Chen, S., Huang, L., Wang, F., Chen, Z., Cai, J., & Fu, L. (2019). Chemotherapeutic drugs stimulate the release and recycling of extracellular vesicles to assist cancer cells in developing an urgent chemoresistance. Molecular Cancer, 18(1). [CrossRef]

- Nikanjam, M., Kato, S., & Kurzrock, R. (2022). Liquid biopsy: current technology and clinical applications. In Journal of Hematology and Oncology (Vol. 15, Issue 1). BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Sadri Nahand, J., Moghoofei, M., Salmaninejad, A., Bahmanpour, Z., Karimzadeh, M., Nasiri, M., Mirzaei, H. R., Pourhanifeh, M. H., Bokharaei-Salim, F., Mirzaei, H., & Hamblin, M. R. (2020). Pathogenic role of exosomes and microRNAs in HPV-mediated inflammation and cervical cancer: A review. In International Journal of Cancer (Vol. 146, Issue 2, pp. 305–320). Wiley-Liss Inc. [CrossRef]

- Paskeh, M. D. A., Entezari, M., Mirzaei, S., Zabolian, A., Saleki, H., Naghdi, M. J., Sabet, S., Khoshbakht, M. A., Hashemi, M., Hushmandi, K., Sethi, G., Zarrabi, A., Kumar, A. P., Tan, S. C., Papadakis, M., Alexiou, A., Islam, M. A., Mostafavi, E., & Ashrafizadeh, M. (2022). Emerging role of exosomes in cancer progression and tumor microenvironment remodeling. In Journal of Hematology and Oncology (Vol. 15, Issue 1). BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Gabaran, S. G., Ghasemzadeh, N., Rahnama, M., Karatas, E., Akbari, A., & Rezaie, J. (2025). Functionalized exosomes for targeted therapy in cancer and regenerative medicine: genetic, chemical, and physical modifications. In Cell Communication and Signaling (Vol. 23, Issue 1). BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Liu, Y., Luo, X., & et al. (2024). HPV16 E6-induced M2 macrophage polarization in the cervical microenvironment via exosomal miR-204-5p. Scientific Reports, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J., Sun, S., Tang, X., Lin, Y., & Hua, K. (2020). Extracellular vesicular Wnt7b mediates HPV E6-induced cervical cancer angiogenesis by activating the β-catenin signaling pathway. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research, 39(1). [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A., Yadav, J., Thakur, K., & et al. (2022). Transcriptome analysis of cervical cancer exosomes and detection of HPVE6*I transcripts in exosomal RNA. BMC Cancer, 22(1). [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q., Shen, Y. J., Hsueh, C. Y., Zhang, Y. F., Yuan, X. H., Zhou, Y. J., Li, J. Y., Lin, L., Wu, C. P., & Hu, C. Y. (2022). Plasma Extracellular Vesicles-Derived miR-99a-5p: A Potential Biomarker to Predict Early Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Pathology and Oncology Research, 28. [CrossRef]

- Leung, L. L., Riaz, M. K., Qu, X., Chan, J., & Meehan, K. (2021). Profiling of extracellular vesicles in oral cancer, from transcriptomics to proteomics. Seminars in Cancer Biology, 74. [CrossRef]

- Galiveti, C. R., Kuhnell, D., Biesiada, J., Zhang, X., Kelsey, K. T., Takiar, V., Tang, A. L., Wise-Draper, T. M., Medvedovic, M., Kasper, S., & Langevin, S. M. (2023). Small extravesicular microRNA in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and its potential as a liquid biopsy for early detection. Head and Neck, 45(1), 212–224. [CrossRef]

- Lv, A., Tu, Z., Huang, Y., Lu, W., & Xie, B. (2020). Circulating exosomal miR-125a-5p as a novel biomarker for cervical cancer. Oncology Letters, 21(1). [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Sun, H., Wang, X., Yu, Q., Li, S., Yu, X., & Gong, W. (2014). Increased exosomal microRNA-21 and microRNA-146a levels in the cervicovaginal lavage specimens of patients with cervical cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 15(1), 758–773. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M., Hou, L., Ma, Y., Zhou, L., Wang, F., Cheng, B., Wang, W., Lu, B., Liu, P., Lu, W., & Lu, Y. (2019). Exosomal let-7d-3p and miR-30d-5p as diagnostic biomarkers for non-invasive screening of cervical cancer and its precursors. Molecular Cancer, 18(1). [CrossRef]

- Tang, K. D., Wan, Y., Zhang, X., Bozyk, N., Vasani, S., Kenny, L., & Punyadeera, C. (2021). Proteomic Alterations in Salivary Exosomes Derived from Human Papillomavirus-Driven Oropharyngeal Cancer. Molecular Diagnosis and Therapy, 25(4), 505–515. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Liu, S. C., Luo, X. H., Tao, G. X., Guan, M., Yuan, H., & Hu, D. K. (2016). Exosomal Long Noncoding RNAs are Differentially Expressed in the Cervicovaginal Lavage Samples of Cervical Cancer Patients. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis, 30(6), 1116–1121. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Cui, F., Wu, X., Zhao, W., & Xia, Q. (2025). The expression and clinical significance of serum exosomal-long non-coding RNA DLEU1 in patients with cervical cancer. Annals of Medicine, 57(1). [CrossRef]

- Dong, S., Zhang, Y., & Wang, Y. (2023). Role of extracellular vesicle in human papillomavirus-associated cervical cancer. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology, 149(17), 16203–16212. [CrossRef]

- Apeltrath, C., Simon, F., Riders, A., Rudack, C., & Oberste, M. (2024). Extracellular Vesicle microRNAs as Possible Liquid Biopsy Markers in HNSCC—A Longitudinal, Monocentric Study. Cancers, 16(22). [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y., Guan, Z., Wang, X., Wang, Z., Zeng, R., Xu, L., & Cao, P. (2018). ALA-PDT promotes HPV-positive cervical cancer cells apoptosis and DCs maturation via miR-34a regulated HMGB1 exosomes secretion. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy, 24, 27–35. [CrossRef]

- Tong, F., Mao, X., Zhang, S., Xie, H., Yan, B., Wang, B., Sun, J., & Wei, L. (2020). HPV + HNSCC-derived exosomal miR-9 induces macrophage M1 polarization and increases tumor radiosensitivity. Cancer Letters, 478, 34–44. [CrossRef]

- Manfredi, F., di Bonito, P., Ridolfi, B., Anticoli, S., Arenaccio, C., Chiozzini, C., Morelli, A. B., & Federico, M. (2016). The CD8+ T cell-mediated immunity induced by HPV-E6 uploaded in engineered exosomes is improved by ISCOMATRIXTM adjuvant. Vaccines, 4(4). [CrossRef]

- di Bonito, P., Ridolfi, B., Columba-Cabezas, S., Giovannelli, A., Chiozzini, C., Manfredi, F., Anticoli, S., Arenaccio, C., & Federico, M. (2015). HPV-E7 delivered by engineered exosomes elicits a protective CD8+ T cell-mediated immune response. Viruses, 7(3), 1079–1099. [CrossRef]

- di Bonito, P., Chiozzini, C., Arenaccio, C., Anticoli, S., Manfredi, F., Olivetta, E., Ferrantelli, F., Falcone, E., Ruggieri, A., & Federico, M. (2017). Antitumor HPV E7-specific CTL activity elicited by in vivo engineered exosomes produced through DNA inoculation. International Journal of Nanomedicine, 12, 4579–4591. [CrossRef]

- Abbasifarid, E., Bolhassani, A., Irani, S., & Sotoodehnejadnematalahi, F. (2021). Synergistic effects of exosomal crocin or curcumin compounds and HPV L1-E7 polypeptide vaccine construct on tumor eradication in C57BL/6 mouse model. PLoS ONE, 16(10 October). [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Zhang, Y., Chen, W., Wu, Y., & Xing, D. (2024). New-generation advanced PROTACs as potential therapeutic agents in cancer therapy. In Molecular Cancer (Vol. 23, Issue 1). BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Mukerjee, N., Maitra, S., & Ghosh, A. (2024). Exosome-based therapy and targeted PROTAC delivery: A new nanomedicine frontier for HPV-mediated cervical cancer treatment. In Clinical and Translational Discovery (Vol. 4, Issue 4). Blackwell Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S., Kumar, P., & Das, B. C. (2021). HPV+ve/−ve oral-tongue cancer stem cells: A potential target for relapse-free therapy. In Translational Oncology (Vol. 14, Issue 1). Neoplasia Press, Inc. [CrossRef]

- Hill, B. L., Calder, A. N., Flemming, J. P., Guo, Y., Gilmore, S. L., Trofa, M. A., Daniels, S. K., Nielsen, T. N., Gleason, L. K., Antysheva, Z., Demina, K., Kotlov, N., Davitt, C. J. H., Cognetti, D. M., Prendergast, G. C., Snook, A. E., Johnson, J. M., Kumar, G., Linnenbach, A. J., … Mahoney, M. Ỹ. G. (2023). IL-8 correlates with nonresponse to neoadjuvant nivolumab in HPV positive HNSCC via a potential extracellular vesicle miR-146a mediated mechanism. Molecular Carcinogenesis, 62(9), 1428–1443. [CrossRef]

- Bastón, E., García-Agulló, J., & Peinado, H. (2025). The influence of extracellular vesicles on tumor evolution and resistance to therapy. Physiological Reviews. [CrossRef]

- Mivehchi, H., Eskandari-Yaghbastlo, A., Emrahoglu, S., & et al. (2025). Tiny messengers, big Impact: Exosomes driving EMT in oral cancer. Pathology - Research and Practice, 268, 155873. [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z., Su, X., Liu, L., & Duan, S. (2025). Liquid biopsy based on EV biomarkers: A new frontier for early diagnosis and prognosis assessment of cancer at ESMO 2024. Nano TransMed, 4, 100084. [CrossRef]

- Tang, L., Zhang, W., Qi, T., Jiang, Z., & Tang, D. (2025). Exosomes play a crucial role in remodeling the tumor microenvironment and in the treatment of gastric cancer. Cell Communication and Signaling, 23(1). [CrossRef]

- Owliaee, I., Khaledian, M., Boroujeni, A. K., & Shojaeian, A. (2023). Engineered small extracellular vesicles as a novel platform to suppress human oncovirus-associated cancers. Infectious Agents and Cancer, 18(1). [CrossRef]

- Semeradtova, A., Liegertova, M., Herma, R., & et al. (2025). Extracellular vesicles in cancer´s communication: messages we can read and how to answer. Molecular Cancer, 24(1). [CrossRef]

| Biomarker | Cancer Type | HPV Status Association | Clinical Utility | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-21 miR-146a |

Cervical Cancer | Upregulated in HPV+ EVs | Diagnosis | Liu et al, 2014 |

| let-7d-3p miR-30d-5p |

Cervical Cancer | Upregulated in HPV+ EVs, regardless of HPV type |

Non-invasive screening of CC, diagnosis | Zheng et al, 2019 |

| miR-125a-5p | Cervical Cancer | Downregulated in HPV+ EVs | Diagnosis | Aixia LV et al, 2021 |

| miR-451a miR-16-2-3p |

HNSCC | Upregulated in HPV+ EVs | Diagnosis, clinical reproducibility | Galiveti et al, 2022 |

| miR-99a-5p | HNSCC | Enriched in HPV+ plasma EVs | Diagnosis, RFS prediction | Huang et al, 2022 Leung et al, 2021 Galiveti et al, 2022 |

| miR-21 miR-let-7a miR-181a |

HNSCC | Upregulated in HPV+ EVs | Diagnosis, follow-up | Apeltrath et al, 2024 |

| miR-204-5p | Cervical Cancer | Upregulated in HPV+ CC EVs | Lesion severity stratification, disease monitoring | Chen et al, 2024 |

| Biomarker | Cancer Type | HPV Status Association | Clinical Utility | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viral RNA (mRNA) | ||||

| HPV16 E6*I | Cervical Cancer | Present in HPV16+ EVs | Viral oncogene detection | Bhat et al, 2022 |

| DNA | ||||

| HPV16 E6/7 DNA | OPC | Present in HPV16+ salivary EVs | Detection of HPV+ OPC patients | Tang et al, 2021 |

| Proteins | ||||

| Wnt7b | Cervical Cancer | Elevated in HPV+ CC | Prognosis (OS, RFS) | Qiu et al, 2020 |

| ANXA1 HSP90 ACTN4 |

Oral Cancer | Upregulated in HPV+ EVs | Disease progression | Leung et al, 2021 |

| Glycolytic enzymes (ALDOA, GAPDH, LDHA, LDHB, PGK1, PKM) | OPC | Present in HPV+ salivary EVs | Detection of HPV+ OPC patients | Tang et al, 2021 |

| lncRNAs | ||||

| HOTAIR MALAT1 MEG3 |

Cervical Cancer | Enriched in exosomes from CVL samples of HPV+ patients | Early detection, risk stratification | Zhang et al, 2016 |

| DLEU1 | Cervical Cancer | Not HPV-type specific | Tumor burden, prognosis | Chen et al, 2025 |

| Strategy | Cargo | Target Mechanism | Cancer Type/Model | Therapeutic Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nefmut-HPV E7 Exosomes | E7 fusion protein | CTL generation | Mouse TC-1 tumor | Anti-tumor CTL response | Bonito et al, 2015 |

| DNA vector for E7-Nefmut | Endogenous E7 exosome production | Immunization without ex vivo engineering | Mouse TC-1 tumor | Anti-tumor CTL response | Bonito et al, 2017 |

| Exo + ISCOMATRIX™ | HPV E6 protein | Enhance antigen presentation | C57 Bl/6 mice | Anti-tumor CTL response | Manfredi et al, 2016 |

| ExoCurcumin/Crocin + L1-E7 vaccine | Natural compounds + vaccine | Th1/CTL immunity induction | Mouse TC-1 tumor | Increased IFN-γ & IL-4 | Abbasifarid et al, 2021 |

| Exosomal PROTACs | E6/E7 degraders | Oncoprotein elimination | Theoretical model (HPV-related) | Targeted degradation | Mukherjee et al, 2024 |

| Mechanism | Exosomal Component | Cancer Type | Effect on Therapy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immune checkpoint failure | miR-146a (↓) | HPV+ HNSCC | Dsg2 (↑) IL-8 (↑) Anti-PD-1 resistance |

Hill et al, 2023 |

| Chemoresistance, relapse | miRNA from CSC-derived exosomes | TSCC (HPV+) | miRNA-driven resistance | Gupta et al, 2021 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).