1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

In the era of smart cities, intelligent transport systems (ITSs) enhance urban traffic efficiency, reduce vehicular congestion, and improve road safety, with vehicle-to-everything (V2X) communication—encompassing vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V), vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I), vehicle-to-network (V2N), and vehicle-to-pedestrian (V2P)—serving as a core enabler [

1,

2,

3]. V2V communication is critical for direct, ultra-low-latency data exchange between vehicles, supporting safety features like collision avoidance, while V2N facilitates high-throughput interactions with cellular infrastructure or base station (BS) for applications like real-time traffic updates and remote diagnostics. However, interlink interference and limited spectrum resources challenge the balance between high V2N data rates and robust V2V reliability. Proper resource block (RB) allocation mitigates interference and latency, optimizing this trade-off to ensure efficient resource use, high V2N rates, and reliable V2V connections, thereby enhancing overall performance in dense, dynamic vehicular networks.

In dynamic vehicular environments, traditional radio resource management (RRM) methods struggle to perform effectively due to high mobility, rapidly changing network topologies, and harsh wireless channel conditions. Specifically, centralized strategies, such as LTE-V2X Mode 3 and new radio-V2X (NR-V2X) Mode 1, face scalability issues due to heavy signaling overhead and reliance on precise global channel state information (CSI) [

4]. Meanwhile, distributed strategies (LTE-V2X Mode 4 and NR-V2X Mode 2) suffer from limited local observations and lack of centralized coordination, leading to frequent collisions and unreliable communication links [

5]. Recently, the application of reinforcement learning (RL) techniques to resource management in vehicular networks has attracted considerable attention. Researchers have proposed RL-based frameworks, leveraging agent-environment interactions to learn optimal allocation policies [

6,

7]. RL agents can learn optimal strategies through environmental interactions without explicit models, adapting to highly dynamic scenarios and optimizing long-term objectives [

8]. However, traditional RL methods, especially those based on independent learning agents and local observations, are limited by partial observability, non-stationary environments, and insufficient modeling of inter-agent interactions.

In a dynamically changing traffic environment, complex resource competition and channel interference exist among V2V communication links. Ignoring the relational structure among vehicles leads to suboptimal decisions, rendering single-agent RL inadequate for addressing the aforementioned challenges [

9]. In this way, each agent (i.e., a V2V link) must consider not only its local state information—such as channel gain, remaining transmission time, and resource demands—but also, more critically, the potential interference from neighboring links on the same spectrum resources. If agents rely solely on local information for policy learning, resource conflicts are likely to occur in high-density dynamic environments, significantly reducing communication success ratios and overall system throughput. Traditional RL methods [

10], such as double Q-learning (DQN) or basic Actor-Critic strategies, typically model states as individual observations, lacking the capability to handle the adjacency relationships in communication topologies and overlooking the interference structure between links. Then, constructing policy networks solely based on traditional feature inputs struggles to capture critical interference information embedded in the network structure. Consequently, policies are susceptible to being constrained by local optima or manifesting self-interested tendencies.

In fact, vehicular networks exhibit distinct graph-structured characteristics: interference relationships among links naturally form a graph, with edges representing resource conflict probabilities or interference relationships. The primary goal of this paper is to coordinate V2V and V2N communications, ensuring their coexistence while maximizing V2V reliability and latency requirements and minimizing V2V interference to V2N links. We convert V2V reliability into a success reception ratio. In this paper, we introduce the Graph Attention Network (GAT) as an interference relationship-aware module in the state processing [

11]. GAT models the interference relationships among links in the communication environment as a graph, where each node represents a V2V link, and edges denote potential interference. The core mechanism of GAT leverages an attention weight mechanism to evaluate the importance of each neighboring link to the current link’s policy decision, aggregating neighbor features with weighted contributions to generate a new state representation enriched with structural information. This enhanced representation incorporates not only local state information but also the structural context of "whether neighboring links conflict and their significance," enabling the policy network to achieve global coordination. Furthermore, this paper adopts a dynamic graph construction mechanism. At each time step, the system dynamically reconstructs the adjacency matrix based on current vehicle positions, channel states, and resource usage, generating a communication graph structure that accurately reflects the real-time interference landscape. In contrast to static adjacency graphs, dynamic graph construction more accurately captures the evolving conflict risks among links, thereby ensuring that the information aggregated by the GAT remains contemporaneously valid. This significantly enhances the generalization ability and environmental adaptability of the policy network.

1.2. Related work

Early works, such as [

12,

13,

14,

15] introduced Q-Learning and DQN methods for distributed resource allocation in V2V networks. These approaches enabled each vehicle or communication link to independently learn resource selection policies, optimizing throughput or reliability while minimizing interference. However, they often assumed stationary environments or negligible inter-agent action impacts, which do not hold in dense vehicular networks where mutual interference is prevalent. To tackle issues arising from nonstationary and partial observability, some studies explored RL methods, including independent Q-Learning [

12], Double Q-Learning [

16], and Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) [

14]. More advanced architectures, such as Multi-Agent DDPG (MADDPG) [

17], explicitly modeled interactions among multiple agents to improve coordination and overall system performance in V2X. Despite progress, existing RL-based resource allocation methods often treat agents as isolated learners or assume limited interaction modeling, constraining their ability to dynamically predict and mitigate interference. Additionally, traditional RL frameworks typically assume a fixed number of agents and static state-action spaces, making them ill-suited for dynamic vehicle densities and fluctuating network topologies.

Given the limitations of traditional RL in modeling inter-agent dependencies, researchers have increasingly turned to Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to capture the complex relational structures within vehicular networks [

18][

19]. GNNs, including Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) [

20] and GraphSAGE [

21], provide powerful tools for learning representations on graph-structured data, where nodes represent vehicles or links, and edges denote interference, proximity, or communication quality. In vehicular network applications, GNNs have been used for link prediction [

22], channel allocation, and resource allocation [

23][

24][

25]. By aggregating information from neighboring nodes, GNNs enable vehicles to construct richer, context-aware representations of their local environment, leading to more informed and coordinated decisions. However, most existing GNN-based methods assume static or slowly evolving graph topologies. In dynamic vehicular networks, where high mobility, varying vehicle numbers, and rapidly changing relationships prevail, maintaining and updating graph structures pose significant challenges. Moreover, many GNN methods are integrated into centralized frameworks, where a central controller aggregates global information for decision-making. While effective in some scenarios, centralized architectures face scalability and latency issues, making them unsuitable for fully distributed V2V communication systems.

Recent efforts have explored dynamic graph learning, proposing techniques like dynamic graph convolutional networks [

11] and attention-based dynamic edge updates [

12] to efficiently capture and update evolving neighbor relationships in vehicular communication, reflecting changing interference patterns and mobility behaviors. Nevertheless, integrating dynamic graph learning into RL for distributed vehicular networks remains relatively unexplored. Most existing GNN-RL hybrid methods either fix graph structures during training or update them infrequently, limiting their responsiveness to real-time environmental changes. Thus, there is an urgent need for frameworks that can (1) dynamically adapt to varying vehicle densities and network topologies, (2) effectively model and leverage inter-agent relationships through graph-based learning.

1.3. Contributions

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

Firstly, we adopt a GAT to extract global features, shifting the optimization objective from individual vehicle performance to system-wide optimality across the entire vehicular network.

Secondly, we dynamically update neighbor relationships based on real-time vehicle positions to accurately capture current interference patterns between vehicles.

Thirdly, we propose a novel GAT-Advantage Actor-Critic (GAT-A2C) RL framework, pioneering the integration of GAT with the Advantage Actor-Critic (A2C) algorithm. This architecture dynamically adapts to positional changes, communication states, and interference fluctuations among neighboring vehicles, enabling optimized resource allocation for both V2V and V2N links.

Lastly, we conduct extensive experimental evaluations across diverse vehicular scenarios with varying densities. Results demonstrate that our GAT-A2C framework outperforms existing methods in key metrics (including V2N rate and V2V success ratio), particularly excelling in high-density environments. The solution further exhibits robust adaptability and superior scalability across all tested vehicle densities.

1.4. Organization

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: In

Section 2, we present a detailed system model for the communication scenario and interference computation.

Section 3 introduces the design of the GAT. In

Section 4, we detail the methodology of GAT-A2C, the training process of A2C, and system implementation considerations.

Section 5 presents experimental settings and experimental results. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. System model, interference analysis, and problem formulation

2.1. Scenario and abstract model

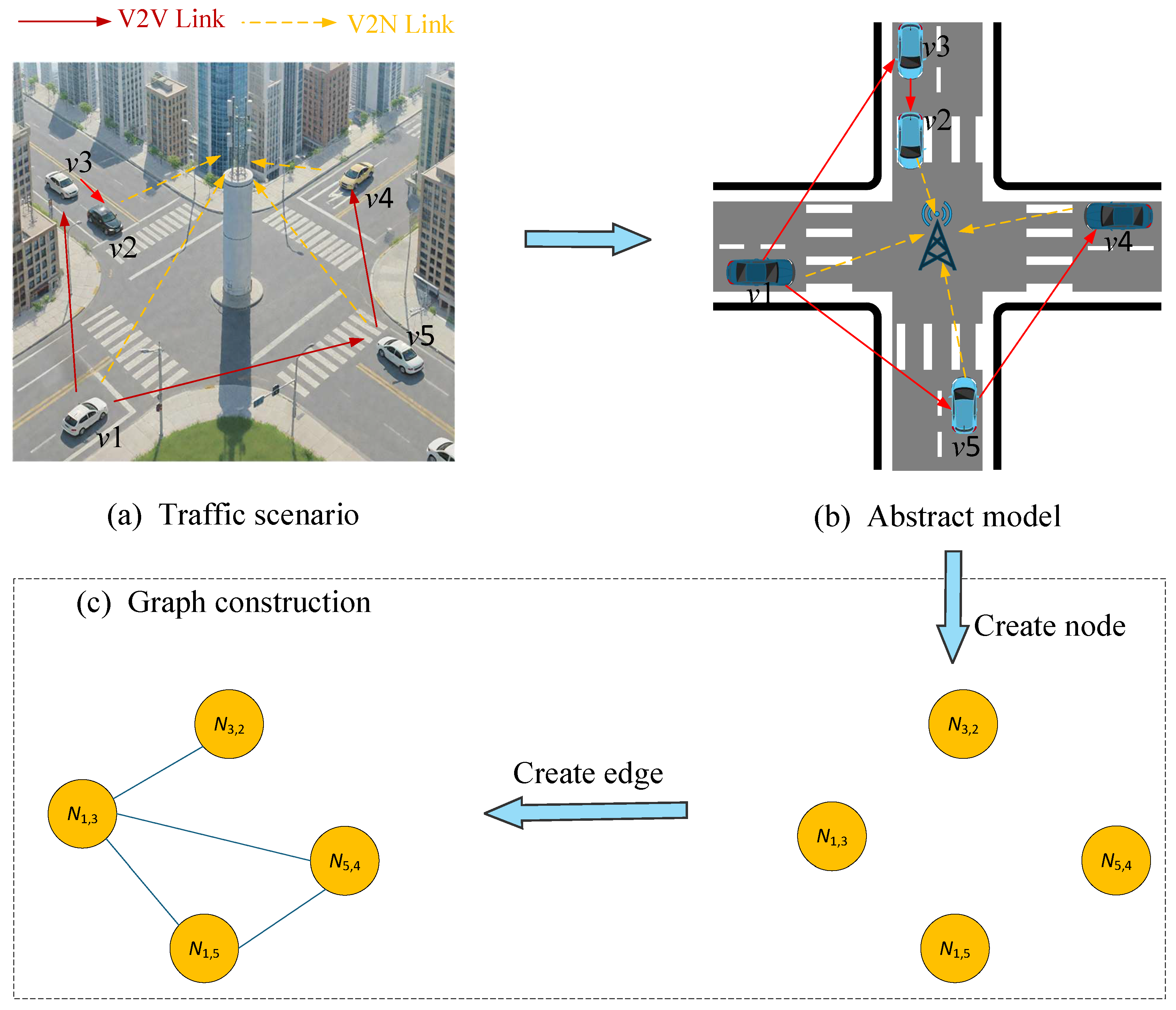

In this paper, we considered an intersection scenario, as shown illustrated in

Figure 1. Vehicles are randomly distributed on the roads. The BS is placed at the exact center of the scenario. V2N uplink and V2V share the same orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (OFDM) band in an in-band overlay manner [

21]. Then, a graph is constructed (as illustrated in

Figure 1 (c)) to represent the vehicular network. A subset of V2V links is sampled and presented as the nodes of the graph, while edges denote the interference relationship between these links. The graph construction process is detailed in

Section 3.1.

2.2. Interference computation and analysis

In this system, the received signal power is directly proportional to the transmit power while being modulated by channel gain, which consists of three components: path loss, shadowing, and fast fading. The power of the received signal can be expressed as:

where

is the transmit power,

and

denote the antenna gains of the transmitter and receiver, respectively, and

is the channel gain, which can be expressed as:

where

,

, and

represent path loss, shadowing, and fast fading, respectively.

Assuming a scenario with

m V2N links, denoted by

,

n connected vehicles, denoted by

, and

k pairs of V2V links, denoted by

. For a V2N or V2V link whoes receiver is vehicle

, the signal-to-interference-plus-noise ratio (SINR) is calculated as follows:

where

denotes the signal power received from the tagged link;

and

represent the interference power from vehicle

and BS, respectively;

and

denote indicator variables, taking the value 1 when their corresponding resource blocks overlap with those of the tagged link, and 0 otherwise;

represents the noise power. Thus, according to Shannon’s second theorem, the channel capacity of the tagged link is given by:

where

B denotes the channel bandwidth.

2.3. Problem formulation

In this paper, resource selection is primarily categorized into two types: resource block selection and transmission power selection. For vehicular communication networks, efficient resource utilization is a prerequisite for maximizing efficiency, playing a critical role in preventing channel congestion and resource selection conflicts. This is particularly vital in cellular-V2X (C-V2X), where vehicles must not only meet their own communication needs but also consider collaboration with other vehicles and avoid occupying their resources.

Regarding transmission power selection, (

1) shows that increasing transmit power can improve received signal quality; it also intensifies interference to other communication links, necessitating an optimal balance between signal quality enhancement and interference control. This system employs a multi-level power control strategy and dynamically adjusts transmit power through RL algorithms to achieve overall system performance optimization. These mathematical relationships provide an important theoretical foundation for power control, resource allocation, and performance optimization in V2V communication systems.

3. Design of graph attention network

In traffic scenarios, V2V links encounter non-uniform interference patterns, with some links being subject to strong interference while others are affected only weakly. We leverage the attention mechanism of GAT to adaptively learn which link contribute more or less interference. This allows the vehicle to effectively avoid heavily interfering neighbors during action selection, thereby reducing link-level interference and improving overall communication performance. In this section, we introduce graph construction and GAT model.

3.1. Graph construction

3.1.1. Principle of graph construction

In this paper, we model the vehicular network as a graph. Each node in the graph, denoted as , represents a unidirectional V2V communication link from transmitter i to receiver j. The edge, denoted as , represents the interference exerted from node x to node y. A complete graph is unsuitable in this context, as vehicles in a vehicular network often transmit messages in a broadcast manner, causing the number of nodes to grow quadratically with the number of vehicles, which in turn leads to significant computational overhead during subsequent processing.

To address the scalable problem of the complete graph, Ji et al. [

21] constructed a graph based on the communication relationship between vehicles, and their simulation results demonstrated its effectiveness. Thus, this paper adopts the same approach to model the vehicular network. For each vehicle, 3 output links are selected whose destination vehicles belong to the nearest 20% subset of all vehicles. This approach reduces the number of nodes to a linear scale, approximately three times the number of vehicles. Then the graph structure can be expressed as follows:

where

is the set of nodes that represents the unidirectional V2V links.

represents the set of all edges in the graph. An edge is established between the corresponding nodes if mutual interference exists between two links.

3.1.2. Graph node state

The feature vector initialized for each node

N is denoted as:

where

and

represent the channel gain of the V2N and V2V communications, respectively;

denotes the total interference power experienced by the node

N.

3.1.3. Dynamic adjacency matrix for graph expression

According to the principle of graph construction, we adopt a link-level adjacency matrix

A with the size of

(which is

, since 3 output links are sampled for each vehicle), representing the connectivity relationships between nodes of the graph. The elements of the link-level adjacency matrix

A are defined as:

where

to preserve the influence of the node’s own features during the attention scoring computation in GAT.

Due to the continuous motion of vehicles, neighbor relationships are not static. Thus, the link-level adjacency matrix

A is reconstructed every

T seconds. Meanwhile, the matrix is also updated immediately upon detecting events such as vehicle acceleration changes exceeding a threshold or significant position jumps. The update frequency needs to balance communication latency and computational overhead, typically set as:

3.2. GAT model

After constructing the graph, we will introduce the GAT model. The aggregation process in GAT refers to how each node collects information from its neighboring nodes, weighted sums them, and forms new node features. In the process, the operation of each node can be divided into: performing linear transformation on the features of itself and all neighboring nodes; calculating the attention score of itself and each neighbor; normalizing these weights using softmax; using these weights to weight the neighbor features and get the new node features.

3.2.1. Linear transformation on the features

In this paper, the initialization of V2V link features serves as the starting point for the entire system’s input. These features are directly fed into the GAT encoding module for neighbor relationship modeling and feature aggregation, while also serving as critical inputs for subsequent Actor action generation and Critic value evaluation. Insufficient input feature information can lead to incomplete node feature extraction by GAT, thereby impacting the accuracy of resource allocation decisions and overall system performance. As previously discussed, we modeled the state of graph nodes as

. However, during the training and iteration of the GAT network, uneven feature dimensions may lead to gradient explosion issues. To accelerate training convergence and mitigate gradient explosion caused by inconsistent feature dimensions, we uniformly normalize the initial input features of graph nodes using standardization:

where

represents the mean of each feature in the training set, and

denotes the standard deviation of each feature in the training set. After standardization, feature values are centered around 0, which enhances the stability and convergence speed of GAT encoding and Actor-Critic training.

After normalization, we further apply a linear transformation to the initial node features. The transformed features for each node are obtained as:

where

represents a shared learnable linear weight matrix, and

denotes the feature dimension of

after transformation. The linear transformation maps all node features to a unified new feature space, providing consistent input for subsequent attention scoring.

3.2.2. Attention score computation

For each pair of adjacent nodes

(satisfying

), the attention score is computed as:

where

is a learnable attention vector,

denotes vector concatenation, and LeakyReLU is the activation function. The purpose of computing attention scores is to learn local similarity or interference strength based on the combination of a node’s own features and its neighbors’ features, preparing for subsequent normalization.

To ensure comparability of scores across varying numbers of neighbors, the attention scores for all neighboring nodes are normalized using Softmax:

where

represents the set of neighbor nodes of node

x. After normalization, the sum of the importance coefficients for all neighbors equals 1, forming a probability distribution to prevent any single neighbor’s features from dominating.

GAT computes an attention score by feeding the concatenated state features of each neighbor node pair into a shared feedforward network, followed by normalization via Softmax to obtain the weight . This weight reflects the importance of a neighbor node to the current node’s policy generation. In V2V scenarios, a neighbor’s importance can be interpreted as its potential interference capability, with higher weights assigned to neighbors more likely to cause resource conflicts. Through this aggregation mechanism, GAT enables each link to identify neighbors posing genuine interference threats, allowing proactive avoidance of these conflict sources in subsequent policy selections.

Using the normalized attention coefficients, a weighted sum of neighbor node features is computed:

where ReLU is a nonlinear activation function, and

represents the context-enhanced feature representation of node

x. By dynamically integrating information from the most important neighbors, this produces node features enriched with contextual and interference-aware information, providing a more accurate basis for subsequent action selection.

3.2.3. Multi-head attention mechanism

The multi-head attention mechanism enables understanding neighbor features from multiple perspectives. A multi-head attention mechanism is employed to further enhance expressiveness and stability. While using

K attention heads,

and

represent the independent weight matrices and attention vectors for

K-th head. Each head independently computes attention coefficients and weighted aggregation outputs; intermediate layer outputs are concatenated. The expression for the intermediate layer is:

Then the final layer output is averaged.

4. The GAT-A2C model for resource allocation problems

In this model, the node embeddings output by the GAT are incorporated as structured features into the state input of the RL agent, greatly enhancing the expressiveness of the state representation. In this way, the RL main network can perceive not only the communication quality, interference level, and resource demand of each link, but also its complex dependencies with neighboring nodes. This enables the agent to make more optimal resource allocation decisions. The integration of GAT and RL in this manner significantly improves the overall performance and generalization capability of the system. This section introduces the GAT-A2C model for optimizing C-V2X resource allocation, including the design of key elements in RL and A2C, as well as the overall framework of the GAT-A2C model.

4.1. The design of key elements in RL and A2C

RL is commonly represented as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), where an agent repeatedly engages with its environment. At each time step, the agent observes the environment’s current state, , and chooses an action, , based on that state. In response, the environment delivers a reward, , and moves to a new state, . This sequence forms a full RL interaction cycle.

In this study, the input state of the RL agent is defined as the combination of features from the GAT and features provided by the environment. The agent responds by selecting both resource blocks and a transmission power level. The environment then returns a reward based on the V2V link interruption probability, V2N communication rate, and transmission time. This reward guides the agent to continuously optimize its action selection to maximize long-term reward, ultimately aiming to learn an optimal dynamic resource allocation strategy.

4.1.1. State space

The state feature vector of each V2V link obtained from the environment is denoted as:

where

represents the channel capacity of the V2N link,

denotes the total interference power received by the V2V link,

indicates the channel gain of the local V2V link,

reflects the resource occupancy status of neighboring links,

stands for the remaining transmission time,

represents the remaining data to be transmitted.

In addition to the state from the environment, we also incorporate the feature

generated by the GAT as part of the state. In this way, the state of the agent is expressed as:

where the symbol "‖" denotes concatenation.

4.1.2. Action space

Based on the collected and observed state information, the A2C network selects an action

according to the policy

. These actions include resource block selection and transmission power selection. In this paper, we adopt a simplified scenario in which the actor network could select actions from

m different resource block groups and three discrete transmission power levels: low, medium, and high. Then the size of the action space is

. The action

corresponds to the resource blocks and power as follows:

where % denotes the modulo operation and / represents floor division.

and

represent the selected resource blocks and the selected power level, respectively.

4.1.3. Reward function

In the resource allocation problem, the immediate reward

is typically designed based on three key criteria: a positive reward is given when the V2V link completes data transmission within the specified time; a negative reward is imposed if the transmission fails; and an additional incentive is provided for achieving successful transmission with lower power consumption, thereby encouraging efficient use of communication resources. The specific reward is calculated as follows.

where

equals the V2N rate, represents the impact of the current action on the V2N communication link;

denotes the V2V transmission success ratio of the current link, corresponding to the impact of the current action on the V2V communication link,

is a weighting coefficient that balances the importance between V2V and V2N communications,

indicates the remaining transmission time for the current task, and

denotes the maximum allowable transmission time.

4.1.4. Actor network

In the A2C algorithm, the Actor’s policy is described using the following policy function:

where

denotes the model parameters of the policy function

, which outputs a probability distribution over actions given an input state. The primary objective of the actor network is to learn an optimal policy

that maximizes

where

where

represents the parameters of the Actor network, and

denotes the probability of taking action

given state

under the current policy.

is the Advantage function, and we have

where

a represents the set of all possible actions and

refers to the action sampled from the distribution.

represents the state-action value estimated by the Critic network.

represents the value estimation of the current state. If

, it indicates that the action performs better than average and its selection probability should be increased; if

, it indicates that the action is suboptimal and its selection probability should be decreased.

In (

21),

is the entropy regularization coefficient. By incorporating policy entropy regularization, the exploration ability of the policy is preserved, helping to prevent premature convergence to local optima. The entropy is defined as:

Therefore, the update formula of the Actor network is:

The final action is selected by choosing the one with the highest probability, as follows.

where

a represents the set of all possible actions, and

refers to the action sampled from the distribution.

Therefore, the update formula for the Actor network is:

where

is a trainable parameter of the Actor network.

4.1.5. Critic network

The goal of the Critic network is to approximate the true action value. we optimize the parameter of the Critic network using the temporal difference (TD) error, which can be expressed as follows.

and

where

represents the immediate reward,

is the discount factor,

is the target Actor network,

denotes the parameters of the target Actor network, and

denotes the parameters of the target Critic network. Therefore, the update formula for the Critic network is:

where

is a trainable parameter of the Critic network.

Periodically, the parameters of the Actor main networks and Critic main networks are adopted to update their respective target networks to ensure stable learning and convergence every

C steps, as follows:

where

is the learning rate, which is typically set to 0.005 or smaller.

4.2. Overall framework of GAT-A2C model

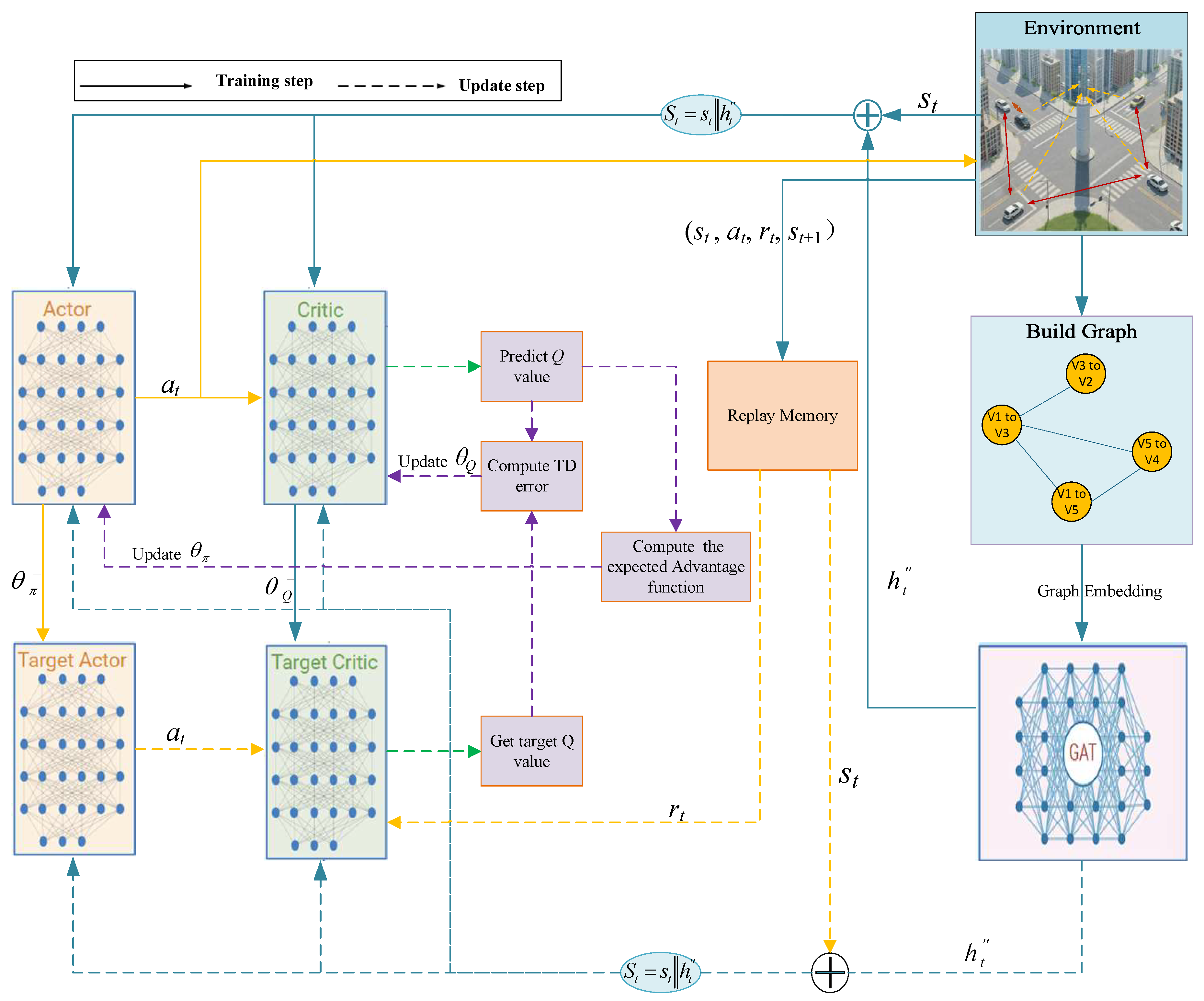

Each V2V link operates as an independent agent and executes the decision-making process described in Algorithm 1. The overall framework is as shown in

Figure 2. In the framework, each vehicle agent is equipped with the following modules, including the environment module, graph construction module, GAT encoding module, Actor decision-making module, Critic evaluation module, local experience replay, and training module. During the training process, the environment first constructs an adjacency matrix based on the current positions of vehicles. This matrix is then used to form a graph structure representing the V2V links and the interference relationship between them. The resulting graph is then fed into the GAT, where multi-head attention mechanisms are applied to aggregate and enhance the features of neighboring nodes, producing enriched node embeddings.

|

Algorithm 1 ResourceAllocationAlgorithm() |

-

Require:

Local state , GAT model, Actor-Critic model, Maximum iteration counter , Current iteration counter , Convergence threshold ,

-

Ensure:

GAT Network parameter , Actor Network parameter , Critic Network parameter , Target Network parameter , , Replay Memory Buffer D; - 1:

while < and = do

- 2:

Initialize Environment, get local State , - 3:

//Step 1: Build Adjacency matrix(dynamic Graph) - 4:

Build dynamic Graph

- 5:

//Step 2: GAT aggregates neighbor information - 6:

- 7:

//Step 3: State concatenation - 8:

- 9:

//Step 4: action selection (Actor outputs resource blocks & power) - 10:

- 11:

//Step 5: Critic scores the current state - 12:

- 13:

//Step 6: The agent executes actions on the environment, and the environment provides feedback to the agent. - 14:

Get

- 15:

//Step 7: Store experiences - 16:

Store (,a,,) into the Replay Memory Buffer D

- 17:

//Step 8: Update Network - 18:

if reached the update period then

- 19:

//Batch sample B instances - 20:

Batch sample B instances from Replay Memory Buffer D ← Batch - 21:

//Calculate the TD(Temporal Difference) target value - 22:

- 23:

//Update the Critic network by minimizing the TD error - 24:

- 25:

//Calculate the Advantage - 26:

- 27:

//Update the Actor network by maximizing the expected advantage function - 28:

- 29:

//Soft update the target network parameters - 30:

- 31:

- 32:

end if

- 33:

- 34:

end while |

The proposed system can be regarded as an instance of centralized training and distributed execution. During training, both the GAT and RL components leverage global network information to learn optimal representations and policies. During execution, each node can make decisions based on its own local state and the corresponding GAT embedding, enabling distributed resource allocation without requiring real-time access to global information. This paradigm combines the advantages of global optimization during training with the scalability and practicality of distributed decision-making during deployment.

Within the framework, the GAT module serves as the core feature encoding unit, which not only performs information aggregation but, more critically, equips each RL agent with the ability to perceive the neighbor interference structure. Specifically, the GAT module receives the initialized node features and the dynamically constructed adjacency matrix. The output context-enhanced features serve for action generation in the Actor network and value evaluation in the Critic network.

These embeddings are then concatenated with the original environmental state to form a composite feature vector

, which is input into the actor network. The actor network processes the state vector and outputs an action

for the corresponding V2V link. Once the action is executed, the environment computes an immediate reward

according to (

19). The environment then updates its state to

, and the transition tuple (

) is stored in the replay memory.

During the update phase, mini-batches B are sampled from the replay memory and fed into the respective networks to update the actor, critic, and GAT networks.

The A2C algorithm consists of two main components: the actor, which represents the policy function and determines the agent’s actions, and the critic, which serves as the value function to evaluate the value of those actions. Based on the rewards returned by the environment, the system adjusts the actor if its action was suboptimal, and corrects the critic if its evaluation was inaccurate. Through continuous updates and iterations, the model gradually learns to output more optimal actions by the approach to maximize the expected return. From the perspective of V2V links, this means that the quality and reliability of V2V communications will progressively improve.

5. Experiment

This section presents the experimental setup and results of a study evaluating the performance of the proposed GAT-A2C strategy for resource allocation in vehicular networks. The experiments are designed to assess the effectiveness of integrating Graph Attention Networks (GAT) with an Actor-Critic (A2C) reinforcement learning framework, particularly under varying vehicle density conditions. By comparing the proposed approach against three baseline methods: random resource allocation, a standard DQN model, and a GNN-DDQN model. This study highlights the advantages of GAT-A2C in optimizing V2N rate and V2V success ratio. The simulation settings, model configurations, and detailed performance analyses are provided to demonstrate the scalability and adaptability of the proposed strategy in dynamic, high-interference vehicular communication environments.

5.1. Experimental settings

The simulations in this study were conducted using Python 3.8 and PyTorch 2.0, adopting settings similar to those in related literature [

21][

26]. We established a Manhattan grid traffic road scenario with a radio communication frequency band of 2 GHz, following the scenario settings described in 3GPP TR 36.885, encompassing both line-of-sight (LOS) and non-line-of-sight (NLOS) channel conditions [

27]. The vehicles are placed according to a Poisson distribution. Each vehicle’s speed, acceleration, and other related information were assigned via a Gaussian distribution.

We employed a GAT model with a depth of two, using four attention heads in the first layer and incorporating edge weights to reflect varying degrees of interaction between communication links. The feature dimension extracted by GAT was set to 16. The input feature dimension for each node in the graph network was 60, with a self-attention mechanism used for feature aggregation. For the A2C model, the state input dimension was 102. Both the actor and critic networks adopted a three-layer neural network architecture with 500, 250, and 120 neurons per layer, respectively. The actor network outputs a probability distribution over 60 actions, while the critic network estimates the value of the state-action pair. A Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) is used as the activation function between layers. The learning rate was set to decrease gradually during training. For the GAT network, the initial learning rate was 0.01, with a decay factor of 0.96, and the final learning rate was

. For the A2C network, the initial learning rate was 0.005, and the final learning rate was

. Other detailed parameter settings are provided in

Table 1.

5.2. Experiment results

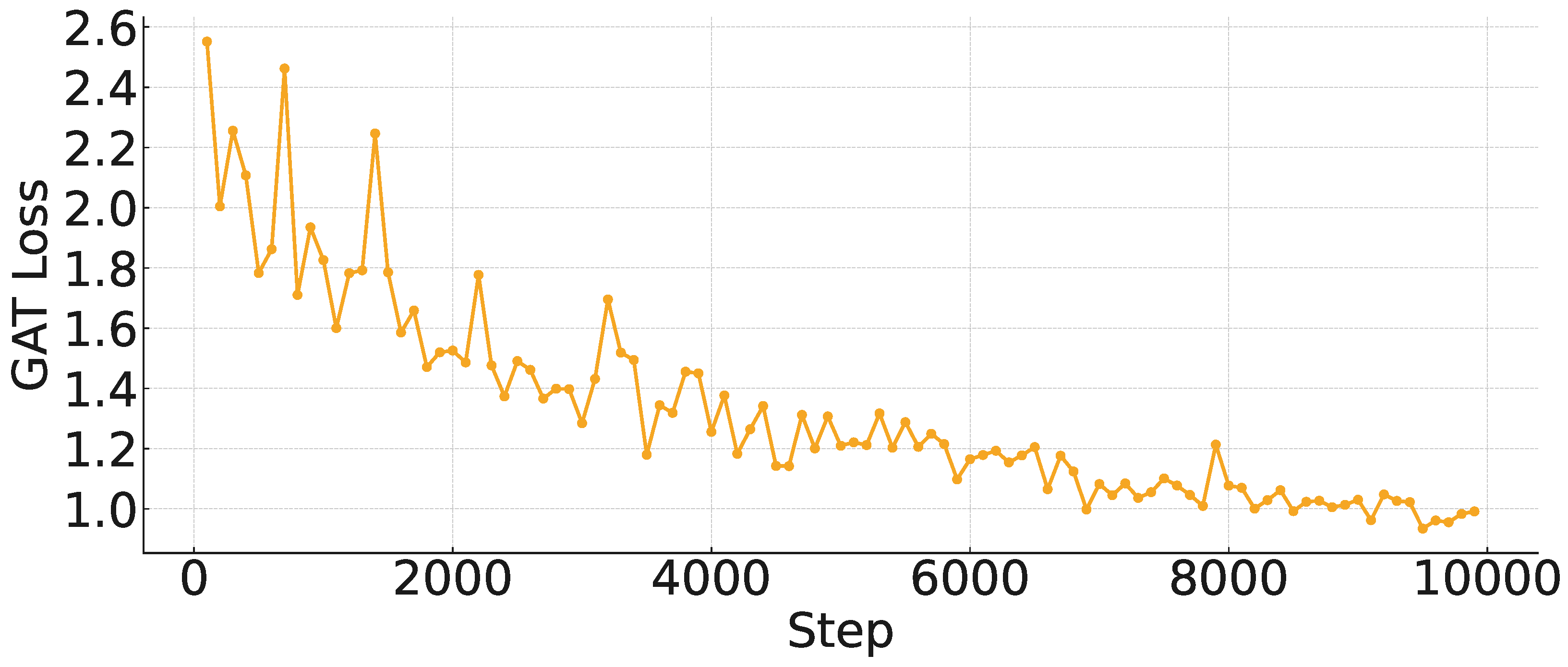

To analyze the training process, we monitored the training details of the GAT separately.

5.2.1. Training loss of the GAT-A2C model

Figure 3 shows the loss performance of the GAT-A2C model in the training process. To optimize computational efficiency, the GAT-A2C model is updated every 100 iterations. We observed that the loss converged quickly, although the environment was reset every 2000 iterations and the relationship of the graph was rebuilt, which caused the loss value to fluctuate significantly in the early stage. However, as the training progressed, it can be seen that the amplitude of the fluctuation is constantly decreasing, which shows that the GAT-A2C model can adapt to the environment.

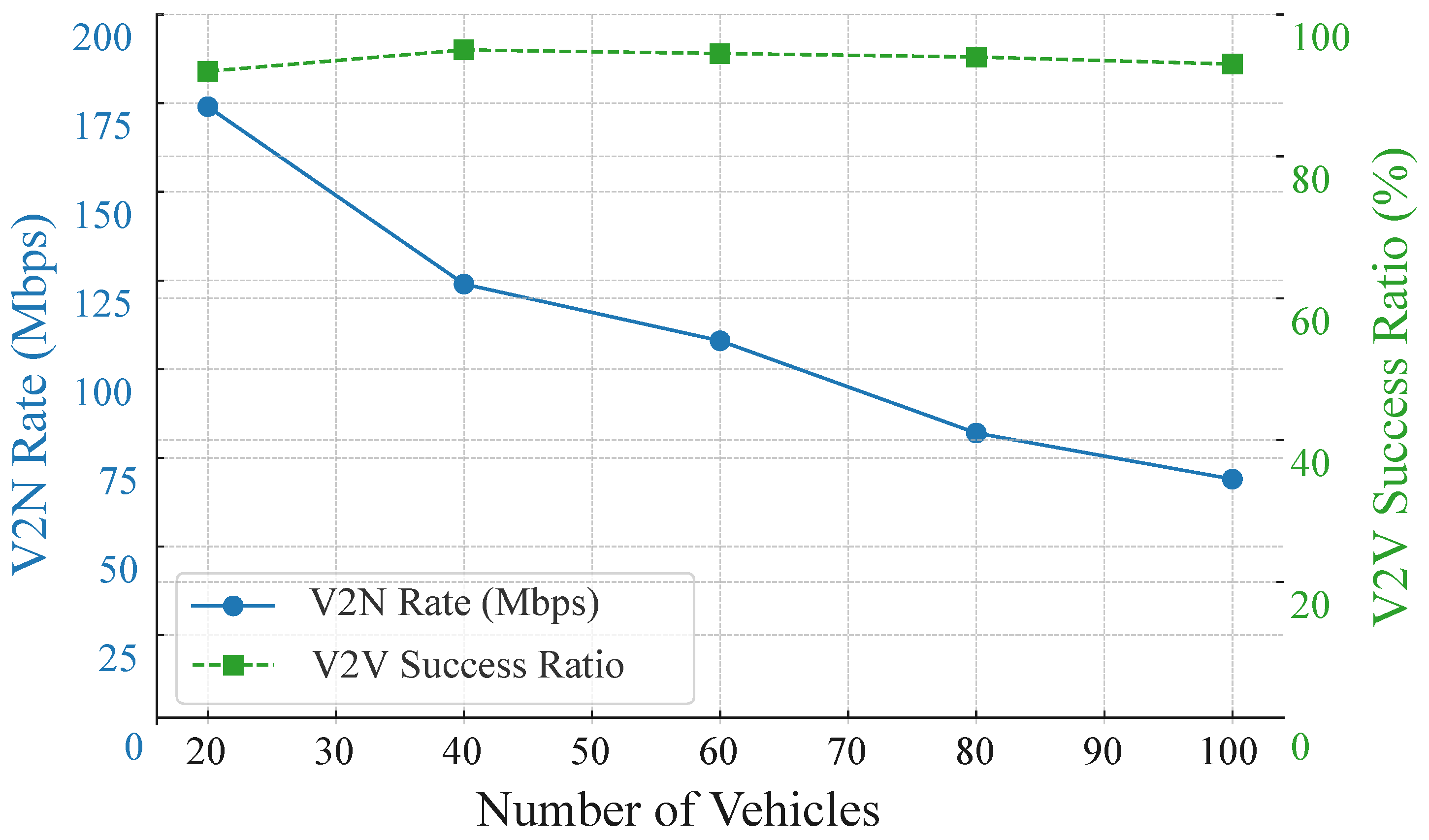

5.2.2. Performance analysis of GAT-A2C at different densities

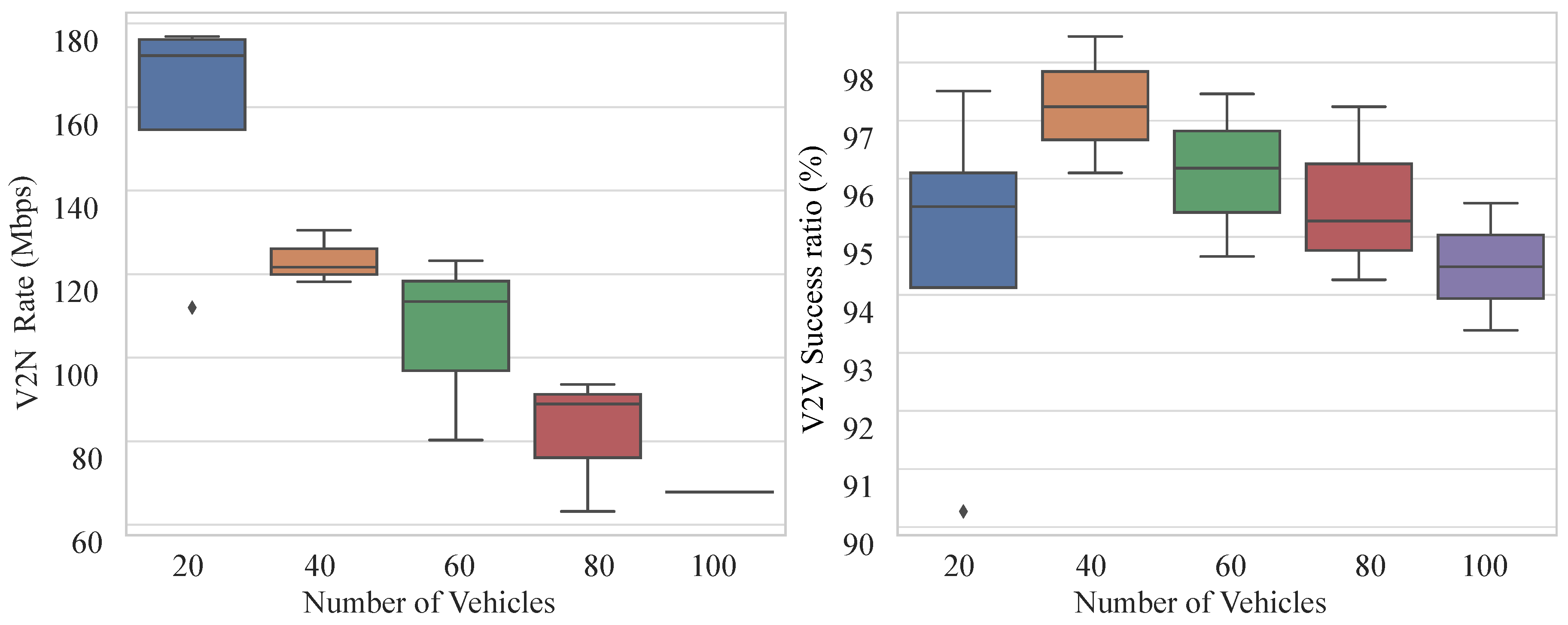

We evaluated the performance of the proposed GAT-A2C strategy on V2N Rate and V2V Success Ratio as the number of vehicles increased from 20 to 100 vehicles. As shown in

Figure 4, the experimental results indicate that as the number of vehicles grows, the number of links in the system surges, intensifying resource block competition and interference. Consequently, the V2N rate exhibits a clear downward trend, dropping from approximately 170 Mbps to around 70 Mbps. Remarkably, despite the vehicle density doubling, the V2V success ratio consistently remains above 90% with minimal fluctuations, demonstrating strong robustness. This can be attributed to the introduction of the GAT, which enables agents to obtain contextually richer state representations, combined with the Actor-Critic strategy’s long-term value assessment mechanism for resource selection. This ensures efficient scheduling even under high vehicle density. Thus, despite some V2N performance trade-offs, the proposed strategy showcases excellent scalability and scheduling robustness in ensuring core V2V service guarantees.

The boxplots in

Figure 5 reveal distinct distribution patterns: V2N rates exhibit decreasing mean values with increasing vehicle density, reflecting intensified interference impacts on resource scheduling. Conversely, V2V success ratios demonstrate remarkable robustness, maintaining medians above 0.93 with minimal fluctuations across densities. Optimal V2V performance occurs at 40 vehicles, showing both peak success ratio and minimal variance. Notably, this outperforms sparse scenarios (e.g., 20 vehicles) since the graph attention mechanism requires sufficient node connectivity and the A2C framework benefits from diverse interaction experiences for optimal policy learning. Occasional low values during initialization confirm the system’s recovery capability, collectively validating the approach’s robustness in high-density environments, particularly for core V2V link maintenance.

5.2.3. Performance analysis compared with other methods

Three baseline methods are employed for comparison. The first is a random resource allocation approach, where the agent arbitrarily assigns channels and power levels, establishing a lower performance benchmark. The second, presented in [

12], utilizes a standard DQN model for resource allocation. The third, described in [

21], integrates GNN with a DDQN to enable each agent to acquire more information from local observations.

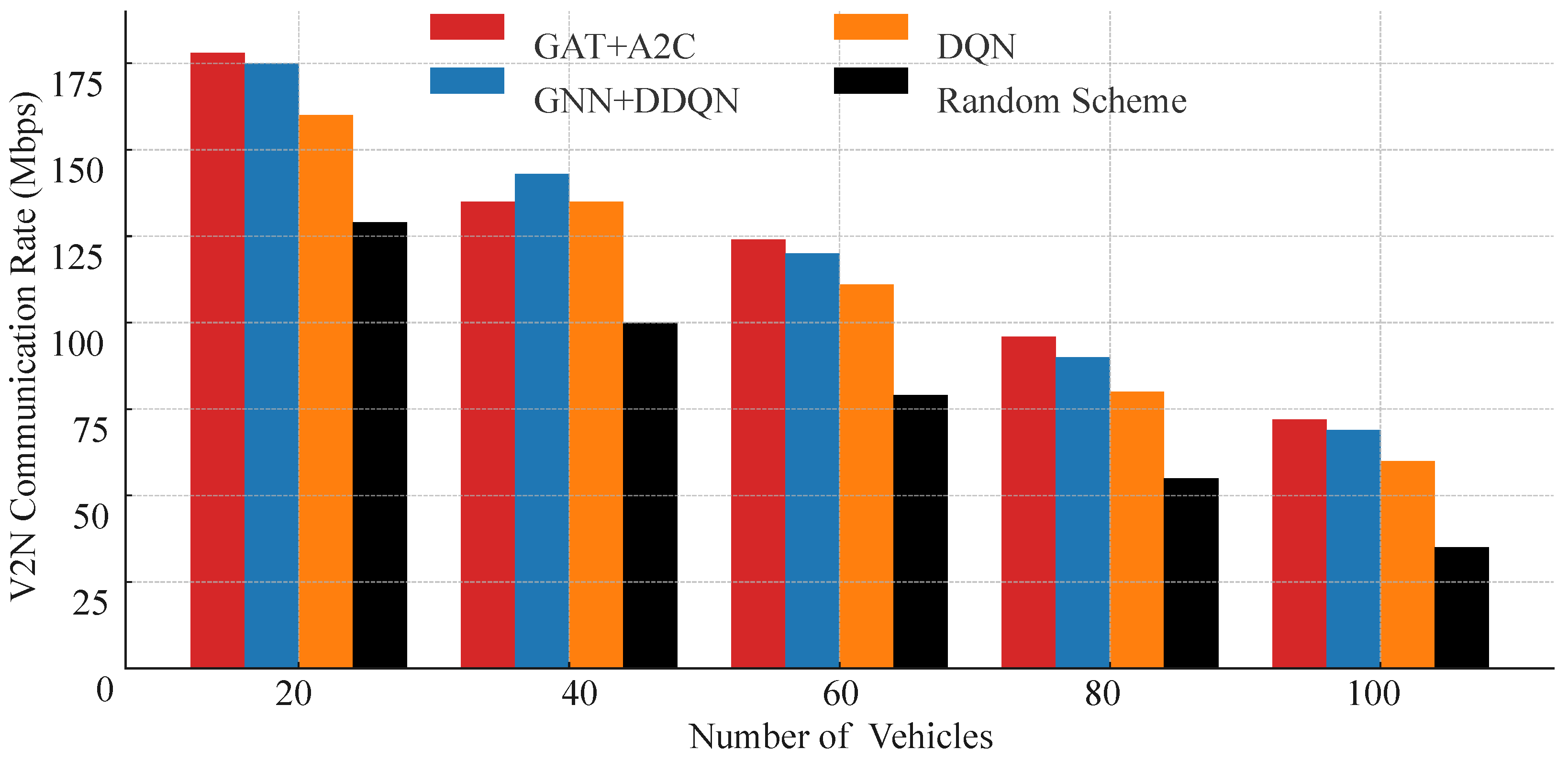

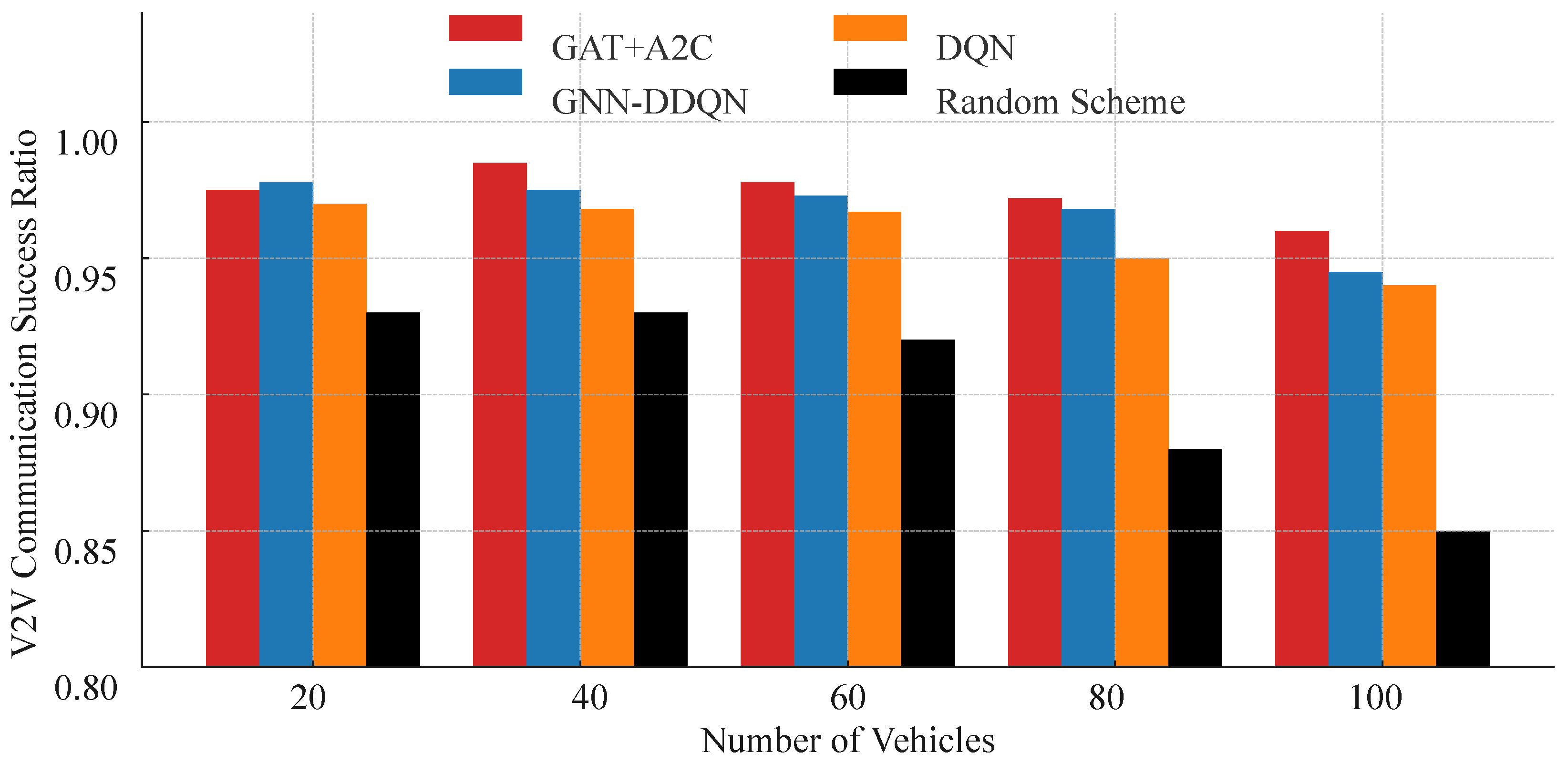

We compared the V2N communication performance of these four resource allocation strategies under varying vehicle density conditions. As shown in

Figure 6, the experimental results demonstrate the significant advantage of the proposed GAT-A2C strategy in terms of V2N rate. As the number of vehicles increases from 20 to 100, the number of interfering links in the system multiplies, intensifying resource block competition, and the V2N rate of all strategies shows a declining trend. However, at each vehicle density, GAT-A2C consistently maintains the highest V2N rate, with a more pronounced lead in high-density scenarios (80 and 100 vehicles). Compared to the traditional DQN method, GAT-A2C achieves over 20% higher V2N rate in the 100-vehicle scenario, and nearly doubles compared to the random strategy. This phenomenon is attributed to the critical role of the Graph Attention Network in state modeling, enabling the strategy to accurately identify high-interference links and make avoidance-driven resource selections. Additionally, the policy gradient optimization mechanism of the A2C architecture enhances the flexibility of resource allocation, avoiding extreme action decisions and improving resource utilization efficiency.

Figure 7 illustrates the V2V link transmission success ratios of different strategies under various vehicle densities, further confirming the effectiveness of the proposed GAT-A2C strategy in ensuring link service guarantees. Overall, GAT-A2C and GNN-DDQN consistently rank highest in V2V success ratio, particularly exhibiting the most stable performance in medium-to-high density scenarios (40–80 vehicles), with success ratios maintained above 96%. In contrast, the standard DQN method shows a significant decline in scenarios with 80 and 100 vehicles, while the random strategy drops below 90%, highlighting the limitations of traditional methods in high-interference environments. Notably, although both GNN-DDQN and the proposed method utilize graph embedding mechanisms, the A2C architecture demonstrates superior policy learning capabilities, dynamically adapting to changes in link states and task urgency, thus offering greater stability under high-density conditions. Combined with

Figure 6, it is evident that the proposed strategy not only ensures high V2V success ratios but also balances V2N rate, showcasing excellent scheduling coordination and overall system service capability. These results validate the feasibility of deeply integrating graph neural network structures with policy-based reinforcement learning methods, effectively addressing the core challenges of multi-link resource allocation in V2X communication.

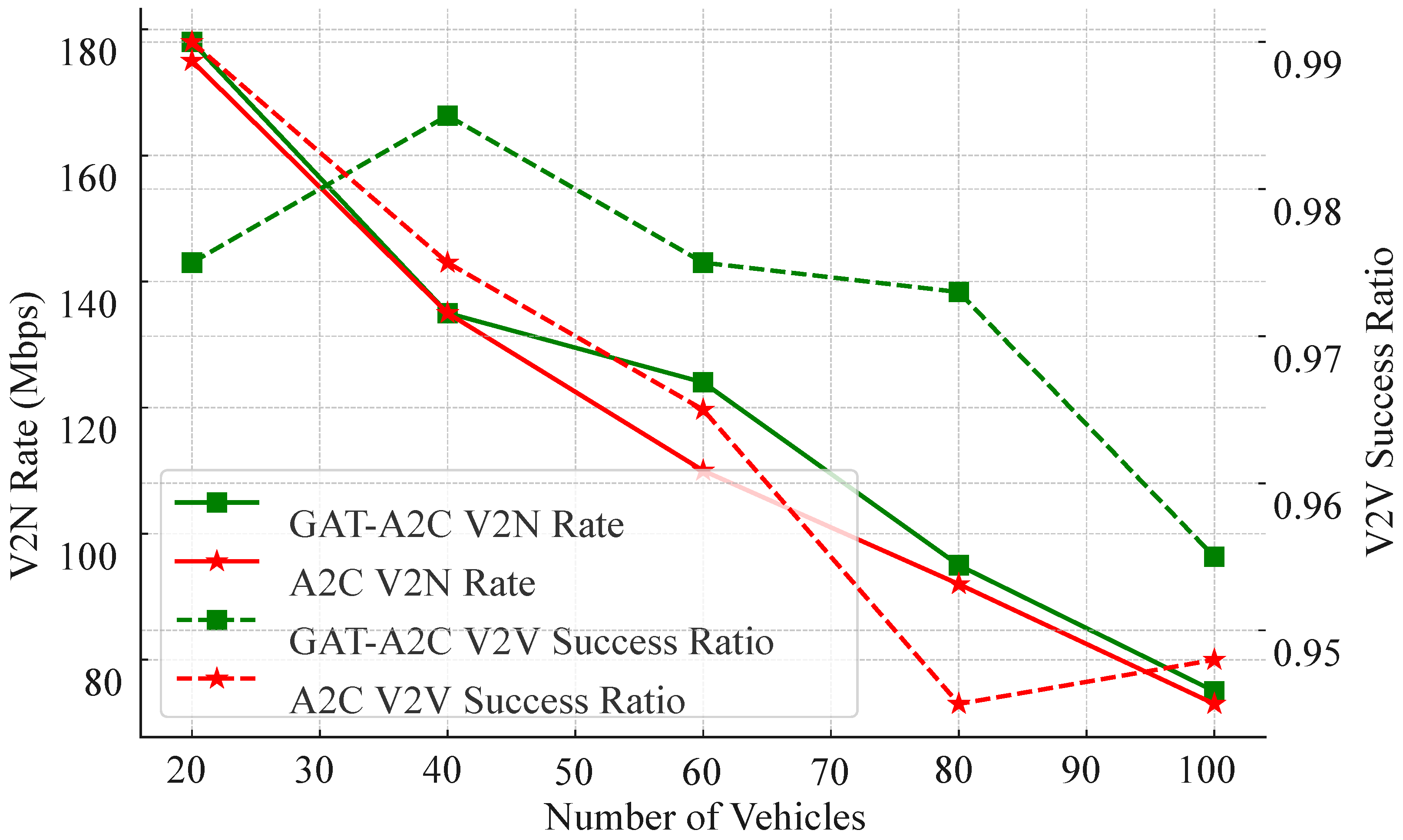

5.2.4. The effect of GAT

Figure 8 presents a comparative analysis of the proposed GAT-A2C strategy versus a pure A2C strategy without graph structure embedding, evaluating V2N rate and V2V success ratio across varying vehicle numbers. The experimental results clearly demonstrate that while both strategies perform similarly in low-density scenarios (20–40 vehicles), GAT-A2C exhibits significantly greater robustness and scalability in medium-to-high density environments.

For V2N rate, both strategies show a declining trend as vehicle density increases. However, GAT-A2C consistently maintains higher transmission rates, particularly in environments with 80 and 100 vehicles, where its rate surpasses A2C by 10–15 Mbps. This indicates that the incorporation of GAT enables the strategy to more accurately perceive interference contexts during resource block selection, mitigating conflict escalation in high-density scenarios.

Regarding V2V success ratio, GAT-A2C not only achieves superior overall performance (consistently above 95%) but also exhibits a more gradual decline. In contrast, the A2C strategy experiences a rapid drop in success ratio when the vehicle number exceeds 60, highlighting its significant limitations in multi-link resource coordination. Combined with earlier power distribution experiments, it is evident that GAT-A2C proactively increases the proportion of medium-to-low power selections in dense vehicle scenarios, whereas A2C exhibits rigid behavior and uniform distribution, failing to adapt flexibly to environmental changes.

In summary, this figure strongly validates the critical role of graph structure awareness in reinforcement learning strategies for large-scale vehicular networks. GAT not only enhances state representation capabilities but also provides a robust foundation for modeling link dependencies, enabling the strategy to maintain strong service guarantees and optimization flexibility in high-density, high-interference, and dynamic topology scenarios. The scheduling stability and high success ratio demonstrated by the GAT-A2C model in complex environments underscore its core advantage as a deployable scheduling solution for vehicular networks.

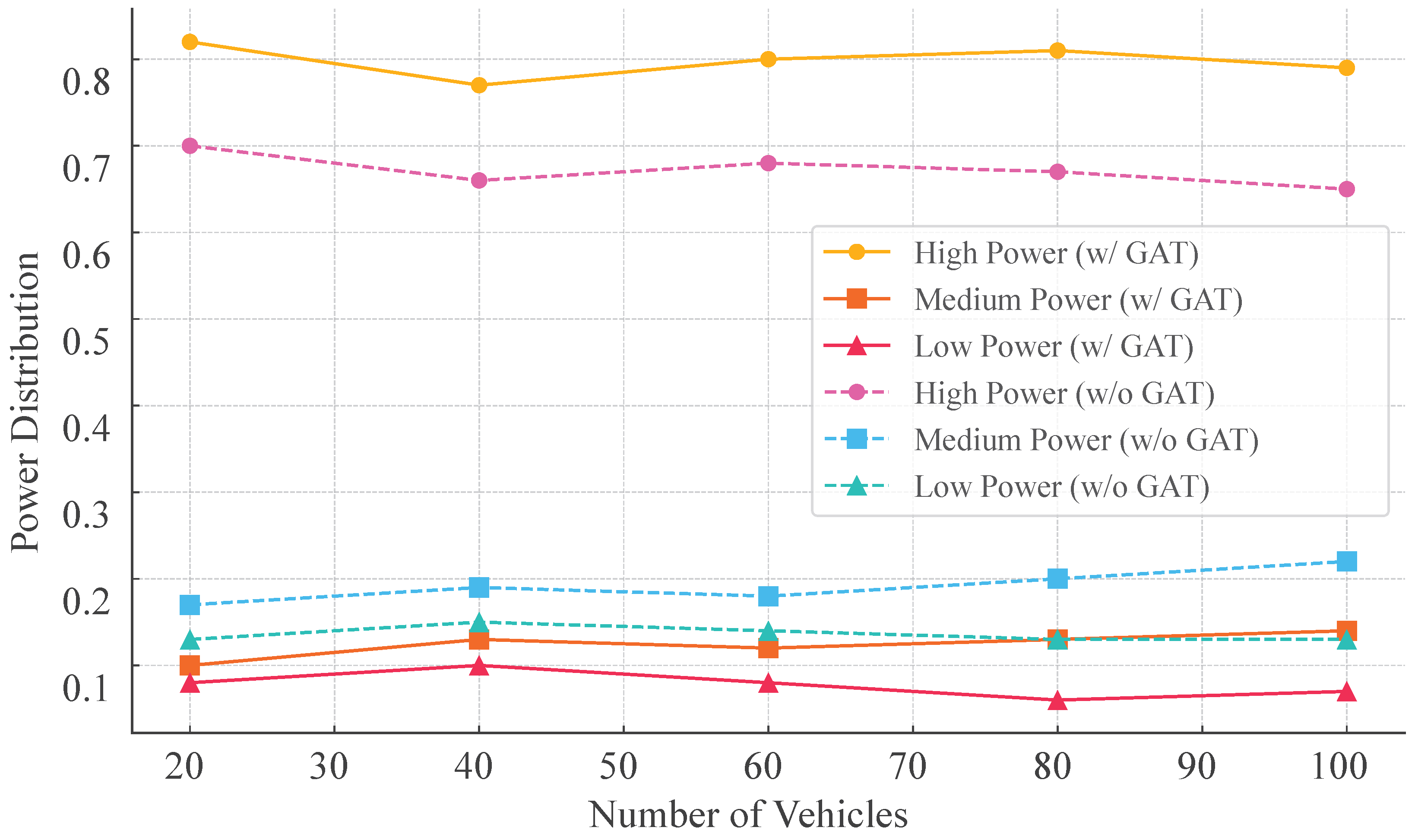

Figure 9 illustrates how the proposed GAT-A2C strategy adjusts the distribution of three transmission power levels (high, medium, low) across varying vehicle densities (20 to 100 vehicles). It is evident that high-power selection consistently prevails (75%–82%) across all density levels, maximizing the transmission range of data packets. This preference enhances the strategy’s ability to ensure robust data delivery, particularly by extending the reach of transmissions. The incorporation of contextual link interference information from the GAT model further reinforces this tendency. Compared to the A2C strategy without GAT, the incorporation of the GAT module markedly elevates the predilection for high-power utilization, capitalizing on structural information embedded within state modeling. This figure confirms, from a behavioral strategy perspective, the enhanced control and adaptability provided by GAT, underscoring the superior effectiveness and robustness of the GAT-A2C strategy in high-density V2X communication systems.

6. Conclusions

This paper addresses the significant challenge of dynamic communication resource allocation in vehicular networks by proposing a novel framework that integrates Graph Attention Networks with Advantage Actor-Critic (GAT-A2C) Deep Reinforcement Learning. This framework innovatively combines GAT with the Advantage Actor-Critic RL paradigm, effectively tackling the resource allocation challenges in dynamic vehicular network environments. Additionally, the method dynamically updates the adjacency matrix based on real-time vehicle mobility and channel conditions, ensuring that the GAT module accurately reflects the current network topology. This is crucial for maintaining communication performance in highly dynamic vehicular environments.

The GAT-A2C framework demonstrates robust training performance, with its GAT loss function converging rapidly after initial fluctuations, showcasing strong learning stability. Comprehensive experimental evaluations confirm the superiority of the proposed method across various vehicle densities. The GAT-A2C framework consistently achieves a V2V communication success ratio above 95%, with minimal degradation as vehicle numbers increase from 20 to 100, highlighting exceptional link service assurance. While the V2N rate declines with rising vehicle density, GAT-A2C outperforms baseline methods like DQN and Actor-Critic without graph structures, achieving over 20% higher rates than traditional DQN in a 100-vehicle scenario. The strategy consistently favors high-power transmission (75%–82%) across density levels, enhancing data delivery range and robustness. By integrating contextual link interference information, the GAT module further strengthens this preference and enhances adaptability, ensuring superior performance compared to other methods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G. L. and Z. L.; methodology, G. L. and Z.W.; software, G. L. and Z. L.; validation, G. L., Z.W., and Z. L.; formal analysis,W. Z.; investigation,W. Z.; data curation, Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Z. L.; writing—review and editing, A. B.; visualization, G. L.; supervision, A. B.; project administration, Z. L.; funding acquisition, Z. L.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Basic Scientific Research Funds of Universities of Heilongjiang Province grant number 2023-KYYWF-1485.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lu, N.; Cheng, N.; Zhang, N.; Shen, X.; Mark, J. Connected Vehicles: Solutions and Challenges. Internet of Things Journal, IEEE 2014, 1, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Chen, J.; Hu, Z.; Lu, Z. A p-Opportunistic Channel Access Scheme for Interference Mitigation Between V2V and V2I Communications. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2020, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y. Connected Vehicles Make Transportation Faster, Safer, Smarter, and Greener! Vehicular Technology IEEE Transactions on 2015, 64, 5409–5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehla, K.; Nguyen, T.M.T.; Pujolle, G.; Velloso, P.B. Resource Allocation Modes in C-V2X: From LTE-V2X to 5G-V2X. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 8291–8314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Martín, M.; Sepulcre, M.; Molina-Masegosa, R.; Gozalvez, J. Analytical Models of the Performance of C-V2X Mode 4 Vehicular Communications. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2019, 68, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zheng, G.; Wong, K.K.; Letaief, K.B. Meta-Reinforcement Learning Based Resource Allocation for Dynamic V2X Communications. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2021, 70, 8964–8977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, B.; Dong, B.; Li, D.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Tsimenidis, C.; Menon, V.G. Optimization of resource allocation for V2X security communication based on multi-agent reinforcement learning. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Xie, X.; Kadoch, M. Intelligent Resource Management Based on Reinforcement Learning for Ultra-Reliable and Low-Latency IoV Communication Networks. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2019, 68, 4157–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, S.; Qian, Y.; Hu, R.Q. Resource Allocation in Vehicular Communications Using Graph and Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM); 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, X.; Palicot, J.; Zhang, H. TACT: A Transfer Actor-Critic Learning Framework for Energy Saving in Cellular Radio Access Networks. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2014, 13, 2000–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Lio, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph Attention Networks 2017. [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Li, G.Y.; Juang, B.H.F. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Resource Allocation for V2V Communications. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2019, 68, 3163–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Qin, H.; Song, B.; Zhang, Y.; Du, X.; Guizani, M. A Reinforcement Learning Method for Joint Mode Selection and Power Adaptation in the V2V Communication Network in 5G. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive Communications and Networking 2020, 6, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.K.; Duong, T.Q.; Vien, N.A.; Le-Khac, N.A.; Nguyen, L.D. Distributed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient for Power Allocation Control in D2D-Based V2V Communications. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 164533–164543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Xie, X.; Kadoch, M. Intelligent Resource Management Based on Reinforcement Learning for Ultra-Reliable and Low-Latency IoV Communication Networks. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2019, 68, 4157–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Chai, X.; Song, X.; Song, T. A DDQN-based Energy-Efficient Resource Allocation Scheme for Low-Latency V2V communication. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 5th International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC); 2022; pp. 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Du, C.; Hu, Y.; Liang, W.; Ng, S.X. Attention Enhanced Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning for Cooperative Spectrum Sensing in Cognitive Radio Networks. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2024, 73, 10464–10477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhang, X.; You, M.; Zheng, G.; Lambotharan, S. A GNN-Based Supervised Learning Framework for Resource Allocation in Wireless IoT Networks. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 1712–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yang, C. Learning Power Allocation for Multi-Cell-Multi-User Systems With Heterogeneous Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2022, 21, 884–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wang, L.; Ye, H.; Li, G.Y.; Juang, B.H.F. Resource Allocation based on Graph Neural Networks in Vehicular Communications. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2020 - 2020 IEEE Global Communications Conference; 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Wu, Q.; Fan, P.; Cheng, N.; Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Letaief, K.B. Graph Neural Networks and Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Resource Allocation for V2X Communications. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2025, 12, 3613–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Zhao, H.; Yan, W.; Hou, L. Resource Allocation with Multi-Level QoS for V2X Based on GNN and RL. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Information Processing and Network Provisioning (ICIPNP); 2023; pp. 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, Y. Link Prediction Based on Graph Neural Networks 2018. [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.02907 2016.

- Zhang, M.; Cui, Z.; Neumann, M.; Chen, Y. An End-to-End Deep Learning Architecture for Graph Classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, H.; Li, G.Y.; Juang, B.H.F. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Resource Allocation for V2V Communications. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2019, 68, 3163–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gpp, T.R. 3rd Generation Partnership Project; Technical Specification Group Radio Access Network; Evolved Universal Terrestrial Radio Access (E-UTRA); Further advancements for E-UTRA physical layer aspects (Release 9).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).