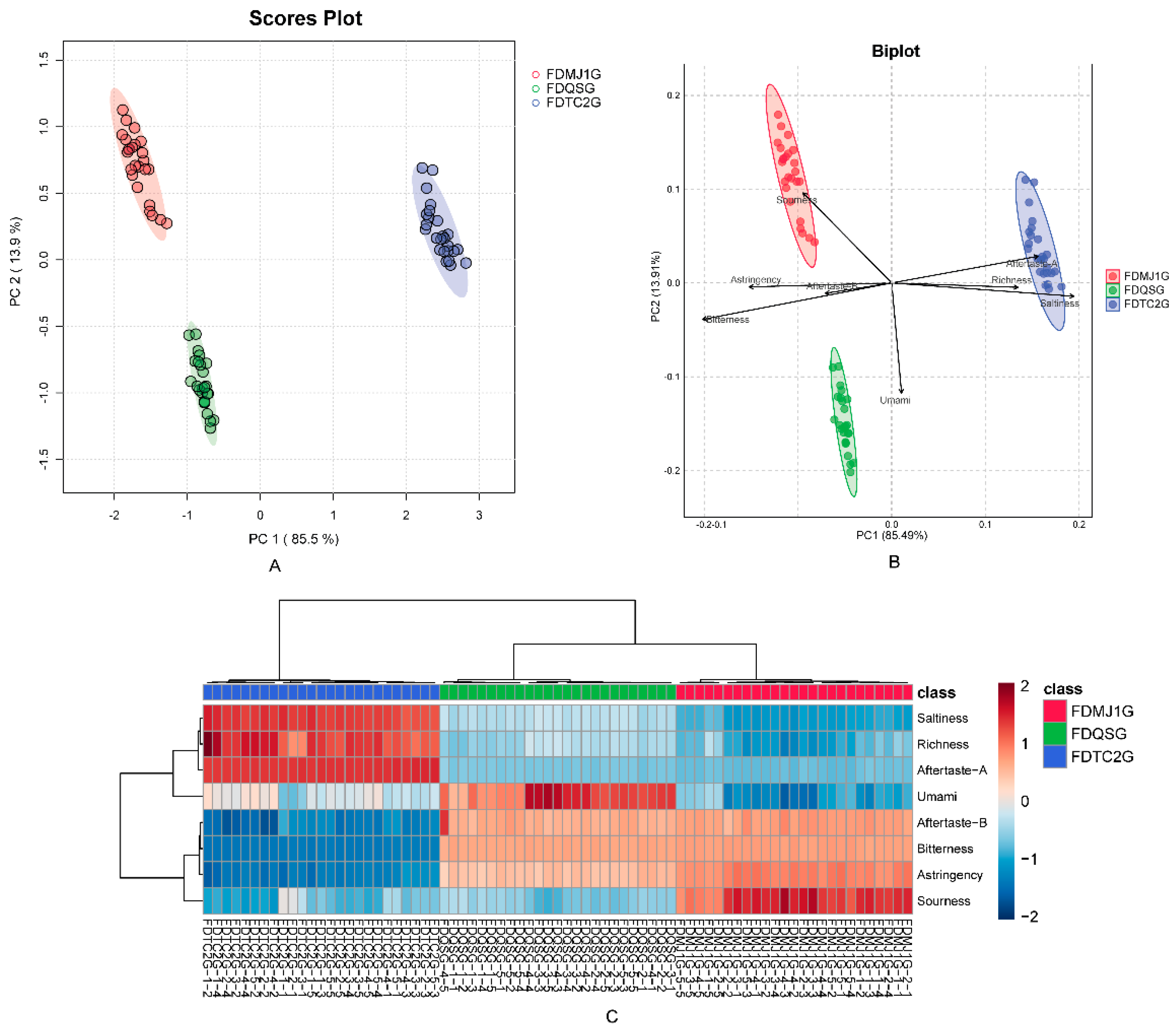

3.3.1. Qualitative and Quantitative VOC Profiling

The overall volatile compound profiles of green teas with different tenderness levels were systematically analyzed using HS-GC-IMS. Compound identification was based on retention time, drift time, and retention index values derived from IMS data. Using the Reporter plug-in, both three-dimensional (

Figure 3A) and two-dimensional (

Figure 3B) topographic visualizations were generated to comprehensively characterize the volatile fingerprints of the tea samples. In the 3D representation, the X-axis corresponds to ion drift time, the Y-axis to gas chromatographic retention time, and the Z-axis to the signal intensity of each volatile compound. The 2D topographic plot offers a more intuitive overview of VOC distribution across the samples, effectively illustrating characteristic fingerprints for green teas of varying leaf tenderness. As shown in

Figure 3B, the spectra were normalized and aligned using the reactive ion peak (RIP), which appears at a drift time of 1.0 (marked by a vertical reference line). Each feature point to the right of the RIP represents an individual volatile component detected in the sample. The color gradient from light blue to deep red indicates increasing compound concentration, with deeper red denoting higher relative abundance.

Figure 3 demonstrates the presence of multiple characteristic peaks, indicating that green tea samples of different maturity levels contain a diverse array of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). To further elucidate differences in volatile profiles among the teas, a differential comparison method was employed (

Figure 3C), with the single-bud sample (FDQSG) set as the reference. Relative differences in VOC intensity between FDQSG and the other two samples (FDMJ1G and FDTC2G) were computed to generate visual differential plots. In these maps, white regions indicate no significant difference; red regions reflect relative enrichment of specific compounds in the compared sample, whereas blue regions indicate reduced abundance relative to the reference. The differential plots revealed a substantially greater number of blue regions in both FDMJ1G and FDTC2G compared with FDQSG, suggesting that increased leaf maturity is associated with a general decline in the concentration of many volatile aroma compounds. Further identification and visualization of these decreasing compounds require detailed examination of the VOC fingerprint maps.

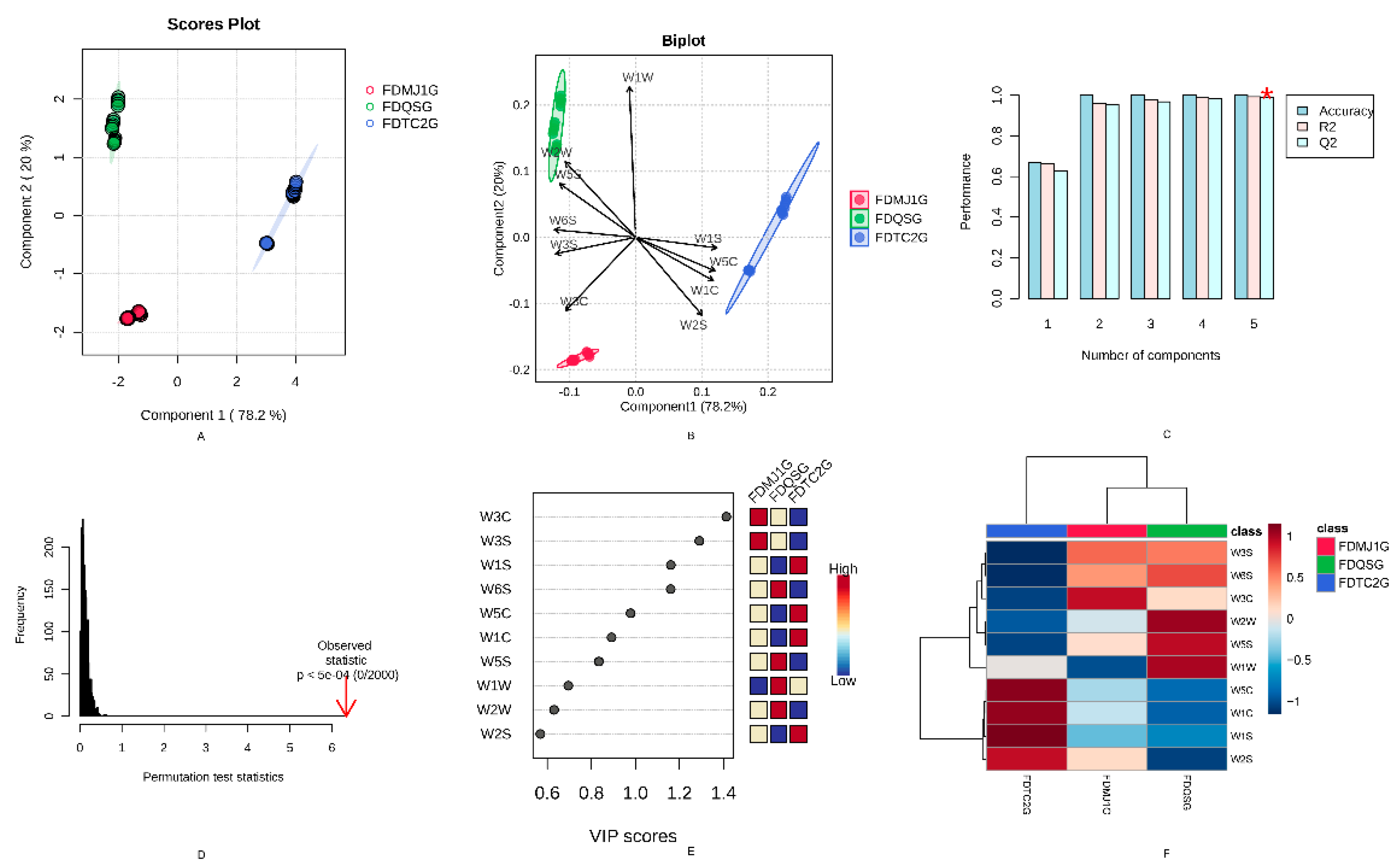

In total, 85 VOCs were detected (

Table S4), comprising 8 terpenes, 19 aldehydes, 13 ketones, 9 alcohols, 10 esters, 6 furans, 3 aromatics, 3 sulfur compounds, 3 pyrazines, 2 acids, 1 heterocyclic (2-acetyl-1-pyrroline), and 8 unidentified peaks. Notably, five VOCs — Nonanal-D, Heptanal-D, Octanal-D, n-Hexanol-D, and pentan-1-ol-D — were identified as forming dimers, a phenomenon attributed to proton-bound dimerization (2M+H)⁺ at elevated concentrations[

14]. The dominant compound classes were aldehydes (22.4%), ketones (15.3%), alcohols (11.8%), and esters (11.8%), with terpenes at 8.2% (

Figure 4A).

Quantitative analysis revealed the highest total VOC content in FDMJ1G (22.03 mg/L), followed by FDQSG and FDTC2G. FDQSG was notable for its aldehyde, sulfur compound, pyrazine, and acid content. FDMJ1G was enriched in terpenes, ketones, furans, aromatics, and unknown compounds, whereas FDTC2G had higher levels of alcohols, esters, heterocyclics (e.g., 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline), and sulfides—including compounds associated with “popcorn”, “meaty”, and “coffee” aromas (

Table S5,

Figure 4B). These compositional differences suggest the involvement of distinct metabolic pathways across different leaf maturity levels, which may have important implications for optimizing processing strategies and guiding product classification and grading in green tea production.

To further identify characteristic volatile compounds and distinguish aroma-active substances among green tea samples with different tenderness levels, fingerprint profiles were constructed to visualize the concentration changes of individual VOCs (

Figure 5). Specifically, regions I, III, and IV correspond to the potential characteristic VOCs of FDQSG, FDMJ11G, and FDTC2G, respectively. Notably, region I, representing FDQSG (single bud), featured the highest number of discriminative compounds (21 in total), predominantly composed of C5–C9 short-chain aldehydes and ketones that impart fresh and green notes. Additionally, short-chain esters (e.g., butyl propanoate) and unsaturated aldehydes (e.g., (E)-2-octenal) contributed fruity and ester-like aromas, while unsaturated alcohols such as oct-1-en-3-ol provided mushroom, earthy, and green sensory characteristics. These compounds are recognized as key odor-active constituents in Nen Xiang (NX), Li Xiang (LX), and Qing Xiang (QX) style green teas [

25]. Furthermore, pyrazines (e.g., 2-ethyl-6-methylpyrazine) and furans (e.g., 2-n-butylfuran), common products of Maillard reactions, contributed roasty and nutty aromas [

26]. Collectively, these volatiles define the fresh and green aroma characteristics typical of single-bud green teas.

In contrast, Region III, associated with FDMJ11G (one bud with one leaf), contained 12 representative VOCs, including methyl salicylate, linalool, 2-butoxyethanol, n-propyl acetate, 2-methyl-2-pentenal, beta-pinene, 2-acetylfuran, furfural, 3-methylthiopropanal, and three unknown compounds. As an intermediate maturity stage, FDMJ11G exhibited a volatile profile suggestive of a metabolic transition between young and mature leaves. This was characterized by terpenoid dominance (e.g., linalool, beta-pinene) and a balance between esters and aldehydes, reflecting a dynamic conversion from alcohols to aldehydes and subsequently to esters. Linalool and methyl salicylate contributed complex floral attributes (citrus, floral, rose, wintergreen, minty), which distinguished this profile from the fresh-green aroma of FDQSG. Additionally, furfural and 2-acetylfuran provided roasted undertones, mitigating excessive grassy notes. Intriguingly, Chen-Yang Shao’s study [

11] on baked green teas with varying tenderness reported a significant increase in methyl salicylate with leaf maturity, which differs from our findings—likely due to varietal differences.

Region IV represented the characteristic VOCs of FDTC2G (one bud with two leaves), which included 3-pentanol, 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline, 2,5-dimethylfuran, benzene acetaldehyde, 2-butanone, and ethylsulfide. The VOC profile of this group, derived from more mature leaves, reflected pronounced Maillard reaction activity during processing, facilitating the formation of compounds such as 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline (popcorn-like) and 2,5-dimethylfuran meaty, gravy roasted beef juice). The accumulation of 3-pentanol and 2-butanone suggested elevated lipid oxidation in FDTC2G compared to the less mature counterparts. 3-Pentanol (herbal) and benzene acetaldehyde (green, floral, sweet) co-occurred with 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline (meaty, roasted) to create a layered and mellow flavor profile for two-leaf green tea. Previous research has identified dimethyl sulfide (cooked corn-like) as a key contributor to the fresh and delicate aroma of green tea [

15,

27], while ethylsulfide—another key VOC in FDTC2G—conveyed coffee- and meat-like notes. The conversion pathway between dimethyl sulfide and ethylsulfide may be critical for modulating the aroma type and quality of FDG, warranting further investigation.

Furthermore, Regions II and V reflected common VOCs shared by all three green tea types. Based on their concentrations and aroma characteristics, six major shared compounds were identified with levels exceeding 1000 µg/L: linalool (citrus, floral, rose), heptanal-D (green), 2-methylbutanal (cocoa), 2-propanone (ethereal, apple, pear), mesityl oxide (vegetal), and methyl acetate (ethereal sweet, fruity). Among these, linalool and heptanal are well-established as key aroma-active compounds in green tea [

2,

28,

29]. Additionally, 2-methylbutanal (VIP = 2.70) and 3-methylbutanal (VIP = 1.30) have been reported as differential markers between yellow teas of different tenderness levels (LYT vs. BYT/SYT) [

10], further suggesting that leaf maturity strongly influences the accumulation of 2-methylbutanal.

Additionally, region IV contained compounds commonly expressed in both FDMJ11G and FDTC2G, notably benzaldehyde (sharp sweet, almond, cherry) and beta-ocimene (floral). Benzaldehyde has been cited as a marker for chestnut-like aroma in green tea[

30], while beta-ocimene, with OAV > 1, is a key floral contributor in flower-scented green teas [

25].

Overall, fingerprint-based VOC profiling provided valuable insights into the compositional and sensory differentiation among green teas with varying tenderness. However, it should be noted that aroma perception is influenced not only by compound concentration but also by the odor threshold in a given matrix. Thus, high-concentration compounds may not necessarily dominate aroma perception, and low- concentration compounds could still play key roles. Quantitative verification of these contributions requires further rOAV (relative Odor Activity Value) analysis.

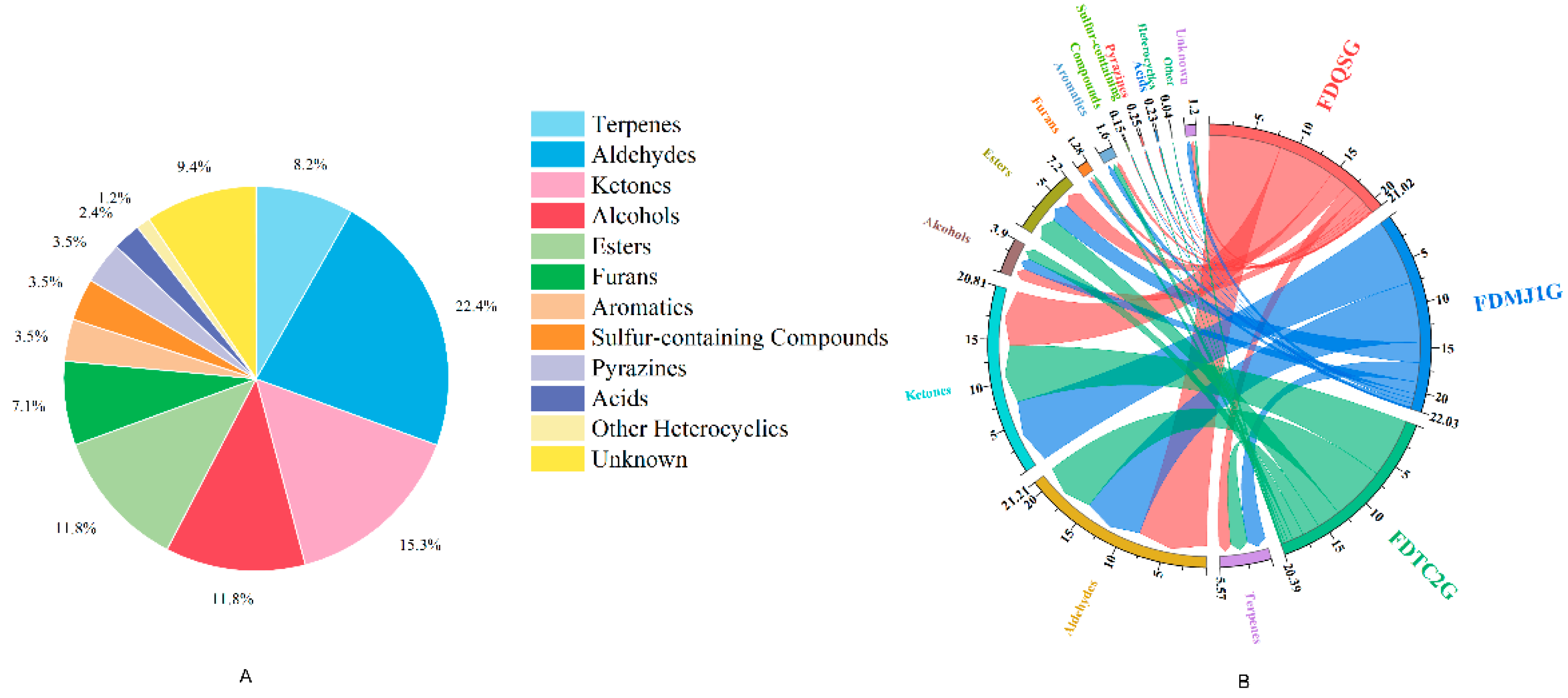

3.3.2. Analysis of VOCs Variation Among FDG of Different Tenderness

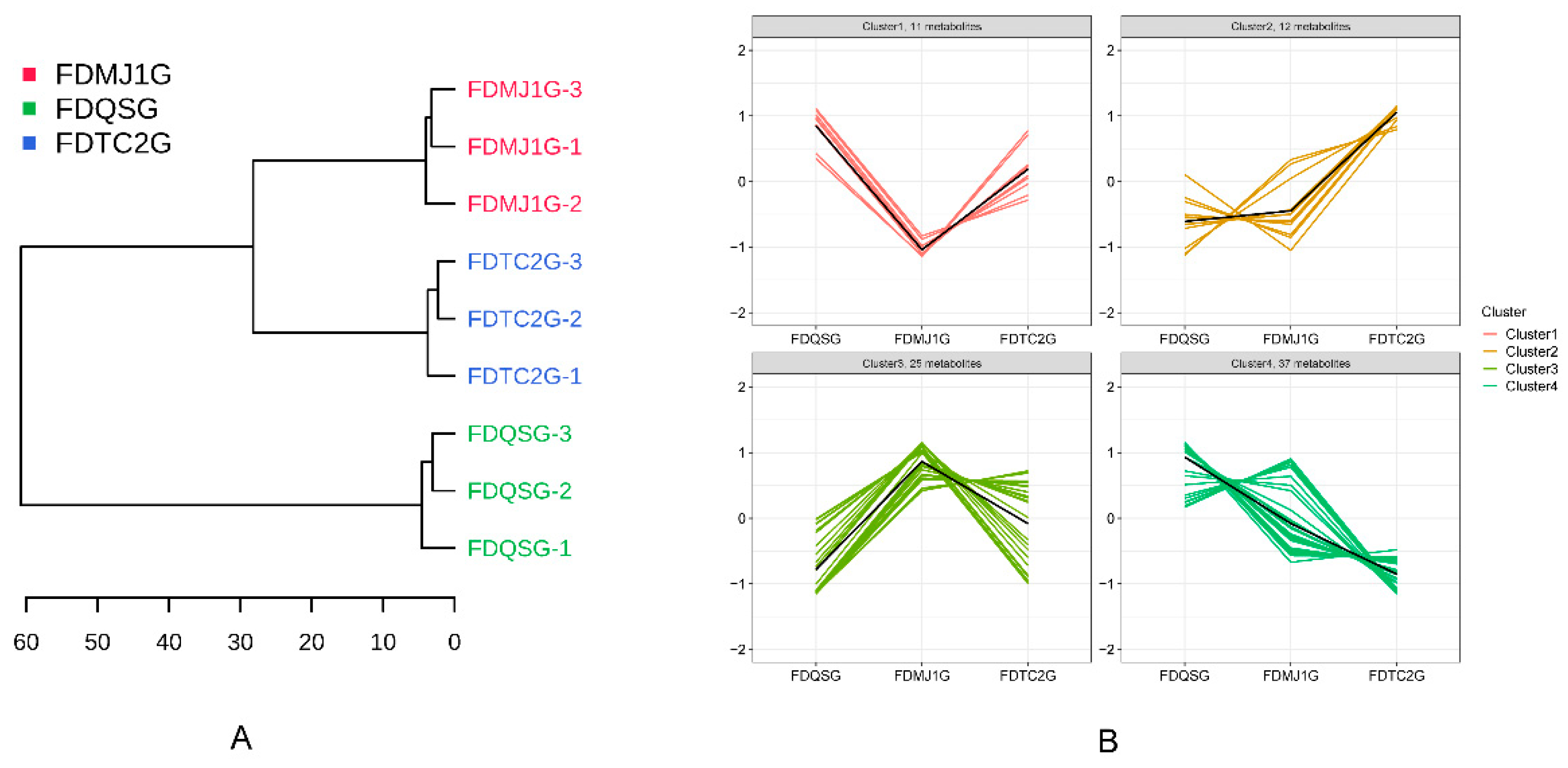

Hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) of all detected VOCs effectively distinguished the green tea samples by tenderness level (

Figure 6A). Notably, the two more mature samples, FDMJ1G and FDTC2G, clustered together on the same branch, while the most tender sample, FDQSG, formed a separate clade, indicating clear differentiation based on VOC composition. Subsequent K-means clustering divided the complete set of VOCs into four distinct clusters (

Figure 6B), each exhibiting unique trends associated with leaf tenderness. Specifically, Cluster 2 contained VOCs whose concentrations increased as leaf tenderness decreased; Cluster 4 showed the opposite trend, with a decline in compound abundance as tenderness decreased. Meanwhile, Cluster 1 exhibited a U-shaped pattern (initial decline followed by an increase), and Cluster 3 demonstrated an inverted U-shape (initial increase followed by a decrease).

Focusing on Cluster 2, which included 12 compounds that increased with decreasing tenderness (see

Table S4), this group exhibited a wide spectrum of sensory attributes such as citrus, cocoa, fruity, roasted, coffee, and popcorn-like aromas. Several compounds also possessed functional properties beyond aroma: for example, Octanal-M is known for its antioxidant and antimicrobial activity[

31], while 3-Pentanol has been reported to stimulate plant immune responses[

32]. In contrast, Cluster 4, comprising 37 VOCs that decreased in abundance with increasing leaf maturity, was characterized predominantly by fresh, green, fatty, fruity, and earthy notes. This suggests a substantial loss of freshness and green-earthy qualities as tenderness diminishes.

Specifically, Cluster 1, with 11 VOCs—primarily aldehydes, alcohols, and ketones—displayed a pattern of decreasing and then increasing concentrations across the tenderness gradient. These compounds were associated with floral, green, and citrusy aromas. Whereas, Cluster 3, encompassing 25 VOCs, exhibited greater structural diversity and included terpenes, short-chain aldehydes/ketones, and aromatic compounds. This cluster was dominated by floral-terpenic, woody, and bready notes, with key compounds such as linalool (citrus, floral, woody), cis-linalool oxide (earthy, floral, woody), β-ocimene (citrus, tropical, green), and β-pinene (pine, woody, resinous). Preliminary analysis suggested that the FDMJ1G sample exhibited notably higher expression levels of terpene-related compounds. These dynamic clustering patterns offer valuable insights into the transformation of volatile profiles across different maturity levels of green tea, highlighting both flavor transitions and potential bio-functional implications.

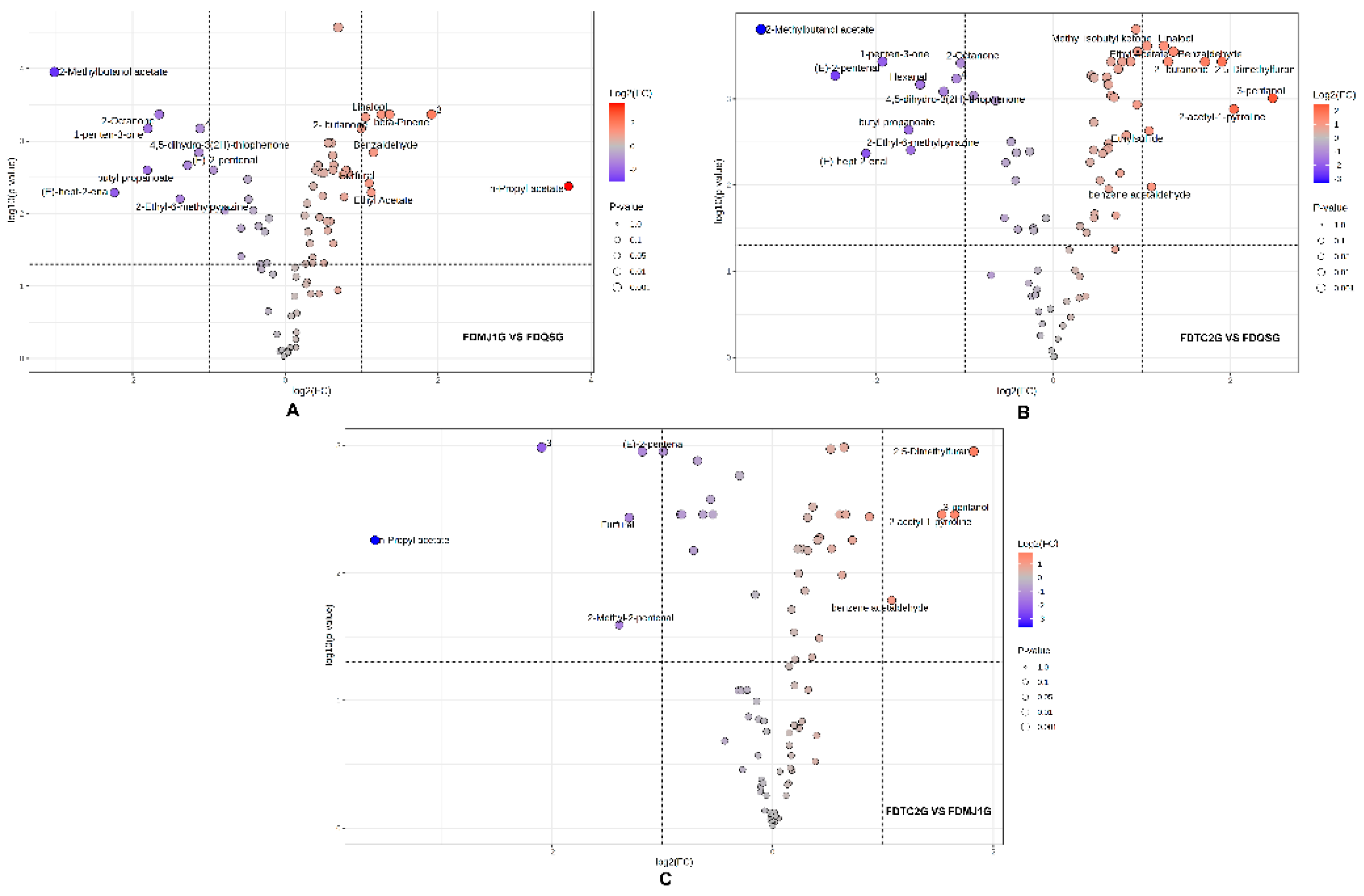

To further elucidate the intergroup differences in VOCs among green teas of varying leaf tenderness, volcano plots were constructed based on fold change (FC) and statistical significance (adjusted p < 0.05, |log₂FC| ≥ 1). A total of 17 VOCs showed significant differences between FDMJ1G and FDQSG, of which 8 were upregulated and 9 were downregulated (

Figure 7A). The upregulated compounds primarily included terpenes such as linalool and β-pinene, which are associated with enhanced plant defense and antimicrobial activity[

33,

34], contributing floral and dry woody notes. Aromatic aldehydes (e.g., benzaldehyde) and furans (e.g., furfural) impart bitter almond, bready, and baked aromas, while esters (e.g., ethyl acetate, n-propyl acetate) and ketones (e.g., 2-butanone) enrich fruity characteristics. In contrast, the downregulated VOCs were predominantly green leaf volatiles responsible for fresh-green notes, including (E)-2-pentenal, (E)-hept-2-enal, 4,5-dihydro-3(2H)-thiophenone, and several fruity, earthy, herbal, and spicy compounds such as 2-methylbutanol acetate, butyl propanoate, 2-octanone, and 1-penten-3-one.

Similarly, in the FDTC2G vs. FDQSG comparison (

Figure 7B), 10 VOCs were significantly upregulated and 10 were downregulated. The upregulated compounds—linalool, methyl isobutyl ketone, benzaldehyde, 2,5-dimethylfuran, 2-butanone, ethyl acetate, 3-pentanol, 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline, ethylsulfide, and benzene acetaldehyde—collectively contributed floral, almond, bready, sweet fruity, toasted grain, coffee, meaty, and honey-like aromas. On the other hand, downregulated compounds included 2-methylbutanol acetate, 1-penten-3-one, 2-octanone, (E)-2-pentenal, hexanal, 4,5-dihydro-3(2H)-thiophenone, butyl propanoate, 2-ethyl-6-methylpyrazine, and (E)-hept-2-enal, which are associated with green, herbal, fatty, and roasted potato–like aromas. The reduction of these compounds indicates a decline in the fresh, fruity, and green sensory qualities.

By contrast, relatively fewer differential compounds were observed between the two more mature samples (FDTC2G vs. FDMJ1G). Only four VOCs showed significant upregulation in FDTC2G (2,5-dimethylfuran, 3-pentanol, 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline, and benzene acetaldehyde), while five VOCs (including (E)-2-pentenal, furfural, n-propyl acetate, 2-methyl-2-pentenal) were significantly downregulated (

Figure 7C). The upregulated compounds contributed roasted, nutty, and fermented notes, indicating a metabolomic shift characteristic of more mature tea leaves. The downregulated compounds were associated with fresh and fruity aromas, echoing the trend observed between FDQSG and the more mature samples.

In summary, comprehensive analysis revealed distinct volatile compound signatures across the three tenderness grades of green tea, demonstrating clear metabolic stratification associated with leaf maturity. In greater detail, the volatile profile of FDQSG (single bud) is predominantly characterized by high levels of C6 aldehydes and alcohols (e.g., hexanal, (Z)-3-hexenol) and monoterpenes (e.g., nerol), which jointly contribute to the fresh, green, fruity, and floral notes typically associated with cut grass and citrus aromas. By contrast, FDMJ1G (one bud plus one leaf) represents an intermediate stage of leaf maturity, where the aroma profile reflects a transition in metabolic activity. The relative balance between terpenes and esters, along with the emergence of Maillard reaction–derived compounds such as benzaldehyde and furfural, results in a more complex and enriched aroma bouquet. Notably, compounds like linalool (floral), β-pinene (woody), and benzaldehyde (almond-like) are markedly elevated, while the content of C6 aldehydes shows a progressive decline. In the case of FDTC2G (one bud plus two leaves), the volatile composition is dominated by Maillard reaction products (e.g., 2,5-dimethylfuran, 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline), fermentation-related esters (e.g., ethyl acetate), and microbial metabolites (e.g., 3-pentanol), collectively imparting roasted, nutty, and savory characteristics. Interestingly, while 2-ethyl-6-methylpyrazine—a key compound contributing to roasted potato–like aromas—is known to enhance roasted notes, its concentration decreases with increasing leaf maturity, implying the involvement of a more intricate regulatory mechanism that warrants further investigation.

Overall, the findings highlight that FDQSG is particularly rich in fresh, green, and fruity aromatic attributes, making it highly suitable for low-temperature fixation processes that aim to retain delicate floral volatiles. This observation is consistent with previous reports on large-leaf black teas with varying degrees of tenderness [

9], although the specific compounds contributing to freshness and fruitiness may vary depending on cultivar and processing techniques. FDMJ1G exhibits a more balanced and multidimensional aroma profile, integrating both floral and fruity characteristics, indicative of an intermediate metabolic state. In contrast, FDTC2G is enriched in nutty, roasted, and fermented sweet–meaty notes, reflecting greater metabolic transformation during processing. These findings are also in agreement with previous research on yellow teas processed from leaves of different maturity levels [

10], where teas made from more mature leaves were associated with enhanced roasted aromas, while bud-only teas demonstrated higher intensities of fresh and floral sensory attributes.

These results suggest that leaf maturity markedly influences volatile metabolite composition and aroma profile. Notably, some VOCs with lower concentrations may still significantly impact scent if their odor activity (rOAV) is high, warranting further sensory threshold validation.

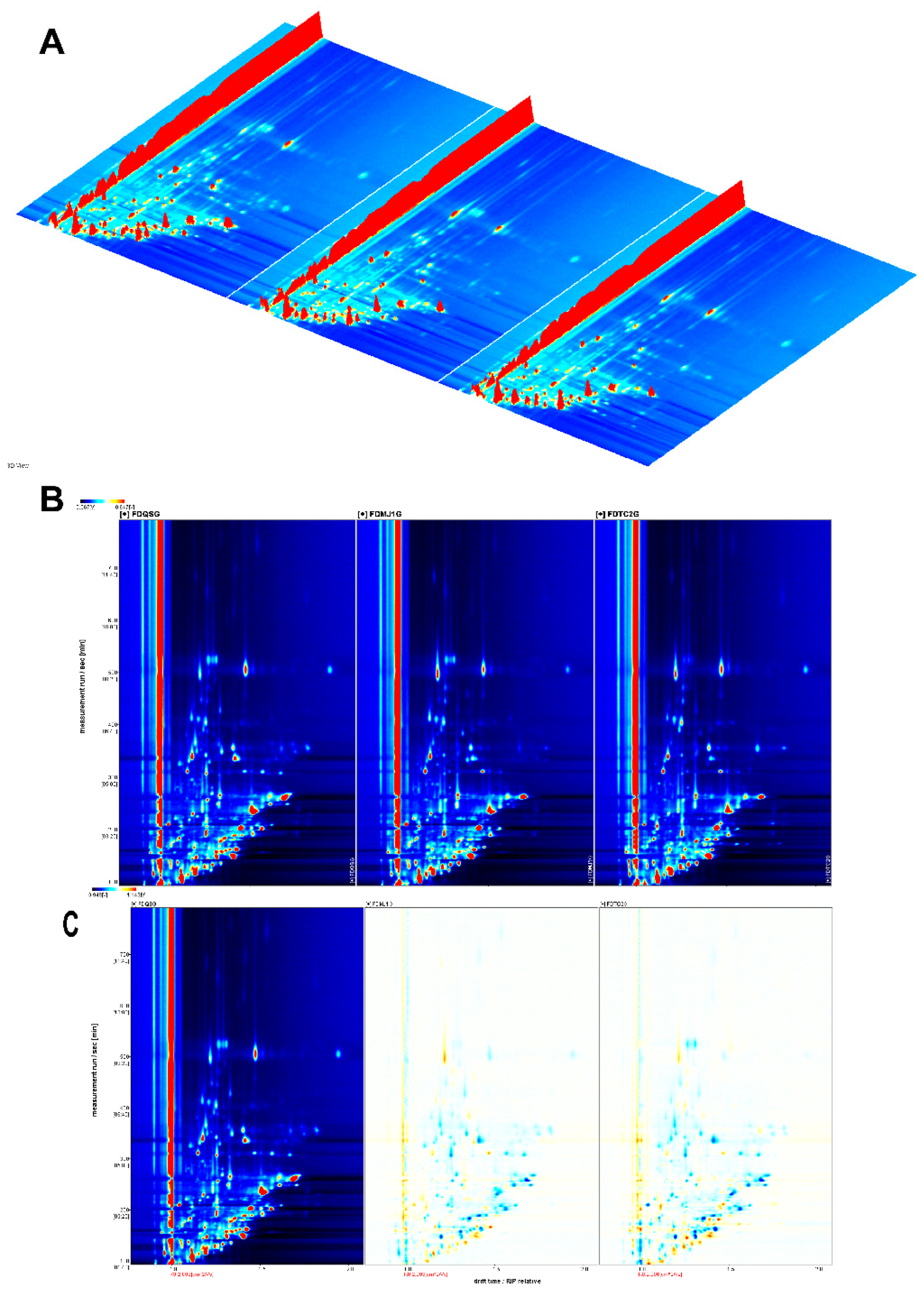

3.3.3. Multivariate Statistical Analysis

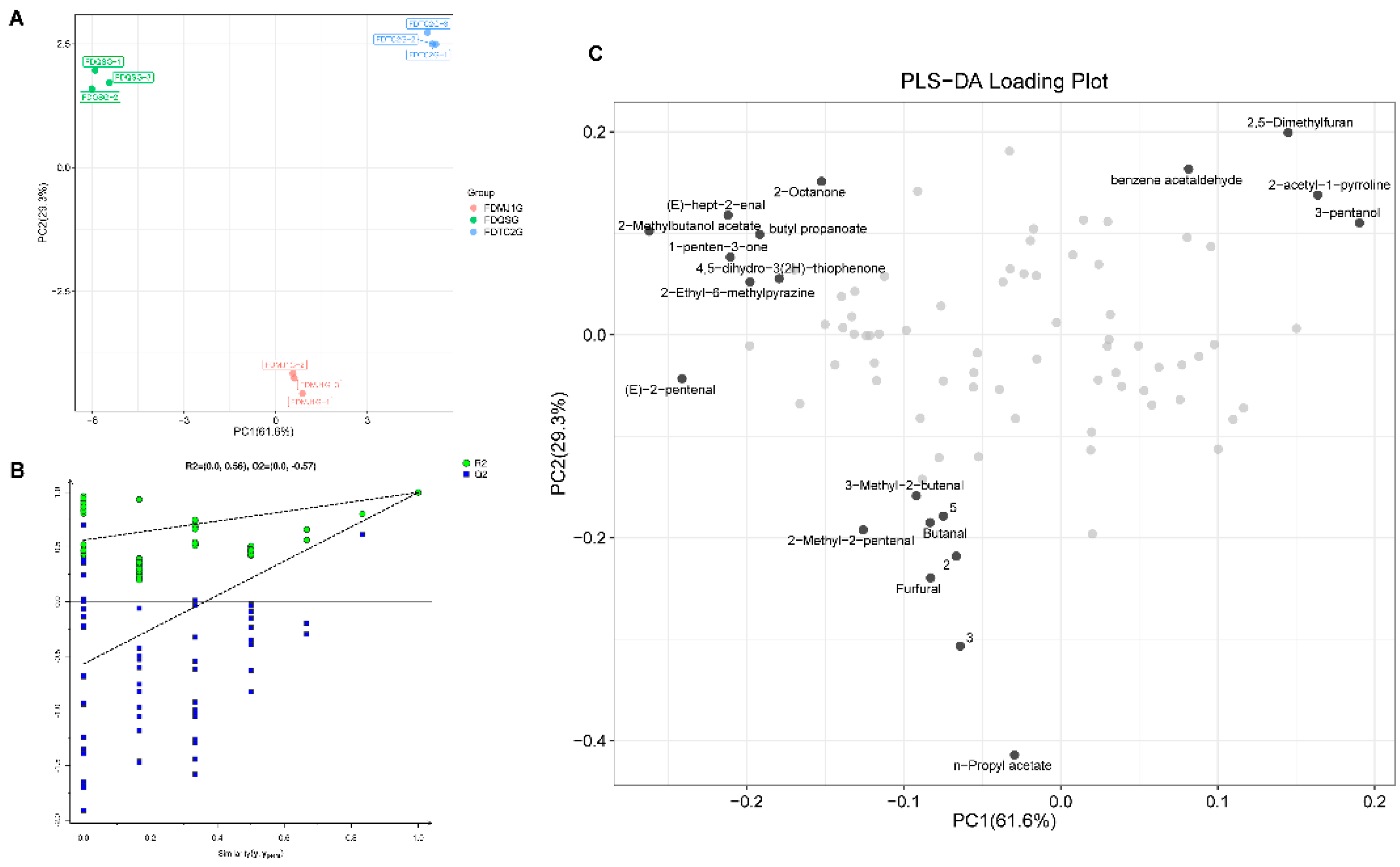

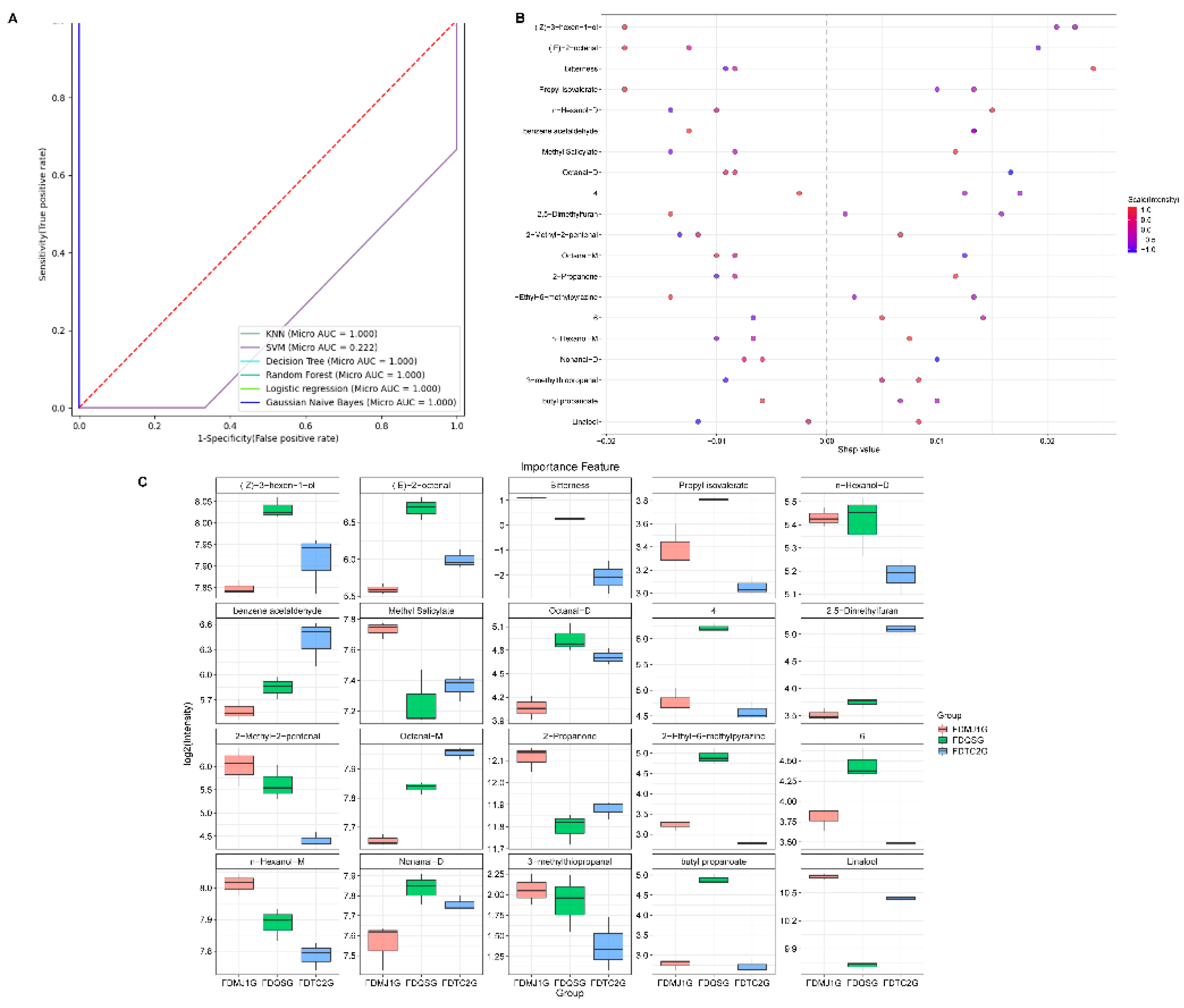

To further investigate the differential VOCs and their evolution across green teas of varying tenderness, a Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) model based on VOCs was employed (

Figure 8). The PLS-DA model yielded high explanatory and predictive power, with R²X = 0.909, R²Y = 0.999, and Q² = 0.998. Additionally, a 200-time permutation test was conducted to assess model robustness, showing a Q² regression intercept of –0.57 on the Y-axis, which is below zero (

Figure 8B), indicating that the model is reliable and not overfitted. As shown in the score plot (

Figure 8A), PC1 accounted for 61.6% of the variance, while PC2 contributed 29.3%, together explaining 90.9% of the total variance. This demonstrates that the first two principal components sufficiently represent the original dataset. The three green tea samples—FDQSG, FDMJ1G, and FDTC2G—were well-separated in the model without any overlap, indicating that the HS-GC-IMS method for VOC acquisition and detection provided strong classification ability for tea samples of different tenderness levels. Moreover, the strong clustering of VOC profiles within each group reflects high repeatability and stability in VOC detection for samples of the same tenderness level.

The loading plot (

Figure 8C) illustrates the contribution of highly correlated VOCs to the principal components, further clarifying the differences in volatile profiles among the three green tea samples of varying tenderness. The plot highlights the VOCs most strongly associated with each sample group—FDQSG, FDMJ1G, and FDTC2G—offering additional insight into their respective aroma characteristics. As shown in

Figure 8C, FDQSG exhibits a larger number of highly correlated VOCs compared to the other two groups. These findings are consistent with the characteristic compounds identified in

Figure 5. Specifically, FDQSG is predominantly associated with C5–C9 short-chain aldehydes and ketones, short-chain esters, which contribute to its fresh and green aroma. FDMJ1G features a balanced profile of esters and aldehydes, reflecting an intermediate metabolic state. In contrast, FDTC2G is characterized by Maillard reaction products and 3-pentanol, indicating a shift toward roasted, nutty, and fermented flavor attributes as leaf maturity increases.

To further identify key VOCs responsible for differentiating among green tea samples, Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) scores were calculated. VIP scores reflect the contribution and explanatory power of each variable to the classification and discrimination of the sample groups. Compounds with VIP scores >1 were considered significant discriminators. As shown in

Table S6, 31 VOCs with VIP >1 were identified as key differential volatile markers in the PLS-DA model based on HS-GC-IMS. These VOCs serve as candidate markers for distinguishing green teas of different tenderness levels. These VOCs serve not only as markers for distinguishing green teas of different tenderness levels but also as foundational features for building subsequent machine learning models aimed at identifying key characteristic parameters.

3.3.4. rOAV Analysis

To assess the contribution of individual volatile compounds (VOCs) to the overall aroma profile of FDG with different tenderness grades, the relative odor activity value (rOAV) of each compound was calculated (

Table S5). Compounds with rOAVs greater than 1 are generally considered to have a perceptible impact on aroma [

20], and thus VOCs meeting this criterion were extracted and summarized in

Table 1 for further discussion.

In total, 41 volatile compounds exhibited rOAV values exceeding 1. Among them, FDQSG contained 33 such compounds, FDMJ1G had 32, and FDTC2G had 31. Notably, 30 VOCs with OAV > 1 were common across all three groups, indicating that the majority of the identified volatiles contribute meaningfully to the aroma profile of FDG. Among these, compounds with extremely high rOAV (rOAV > 1000) were primarily aldehydes (e.g., 2-methylbutanal), terpenes (linalool), and pyrazines (2-ethyl-3,5-dimethylpyrazine), which serve as key odorants. Specifically, 2-methylbutanal (chocolate/cocoa-like) and 3-methylbutanal (chocolate, peach) demonstrated remarkably high rOAVs (>1000 and ~ 580 –720, respectively), confirming their potent sensory effects. Linalool, a floral terpene, exhibited the highest rOAV across all samples (ranging from 6298 to 7430), despite its relatively low concentration due to its ultra-low odor threshold (OT = 0.22 μg/L), making it a major aroma-contributing compound. Likewise, 2-ethyl-3,5-dimethylpyrazine, with its nutty character and extremely low OT (0.04 μg/L), also showed high rOAVs (~1400–1600), indicating its persistent and potent contribution.

Interestingly, linalool peaked in the intermediate maturity sample FDMJ1G, suggesting a metabolic surge at this developmental stage, whereas 2-methylbutanal increased progressively with maturity and reached its maximum in the most mature sample FDTC2G. Pyrazines, in contrast, remained relatively stable across all tenderness stages, indicating their sustained contribution to nutty and roasted attributes.

Furthermore, a clear maturity-dependent shift in dominant aroma-active compounds was observed across the three tenderness levels of green tea. In early maturity (FDQSG, single bud), the aroma profile was primarily characterized by fresh, green, floral, and citrus-like attributes. This was largely driven by high rOAVs of terpenes such as linalool (3834.59) and trans-linalool oxide (4.23), along with C6 aldehydes and alcohols, including hexanal (169.37) and (Z)-3-hexenol (67.14), which contributed grassy and leafy freshness. In addition, the presence of 2-methylbutanal (1054.31), a cocoa-like aldehyde, imparted a subtle sweet and nutty nuance. These volatiles collectively defined the characteristic fresh and green sensory quality typical of bud-only green teas.

At the intermediate maturity stage (FDMJ1G, one bud plus one leaf), the aroma complexity increased significantly, reflecting a balance between floral, fruity, and nutty notes. Notably, linalool reached its highest rOAV (7430.09), indicating a floral surge likely linked to transient metabolic activation. Meanwhile, 2-ethyl-3,5-dimethylpyrazine (1444.50) provided a stable nutty backbone. A substantial decline in hexanal (71.45; −58% vs. FDQSG) marked the attenuation of green freshness. Concurrently, elevated levels of Maillard- and fermentation-associated compounds such as 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline and ester volatiles (e.g., 2-methylbutanol acetate) contributed toasted, sweet, and fruity nuances, indicating active secondary metabolic transitions.

In contrast, late maturity (FDTC2G, one bud plus two leaves) was marked by a pronounced shift toward roasted, nutty, and savory sensory attributes. The sharp increase in Maillard-derived 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline (163.08; +185% vs. FDMJ1G) contributed intense popcorn-like notes. The persistent high levels of 2-ethyl-3,5-dimethylpyrazine (~1349.00) ensured continuity in nutty perception. These changes collectively reflect a maturity-dependent transformation in aroma composition, likely governed by both enzymatic and non-enzymatic reactions during leaf development and subsequent processing.

3.3.4. KEGG Functional Annotation and Enrichment of VOCs

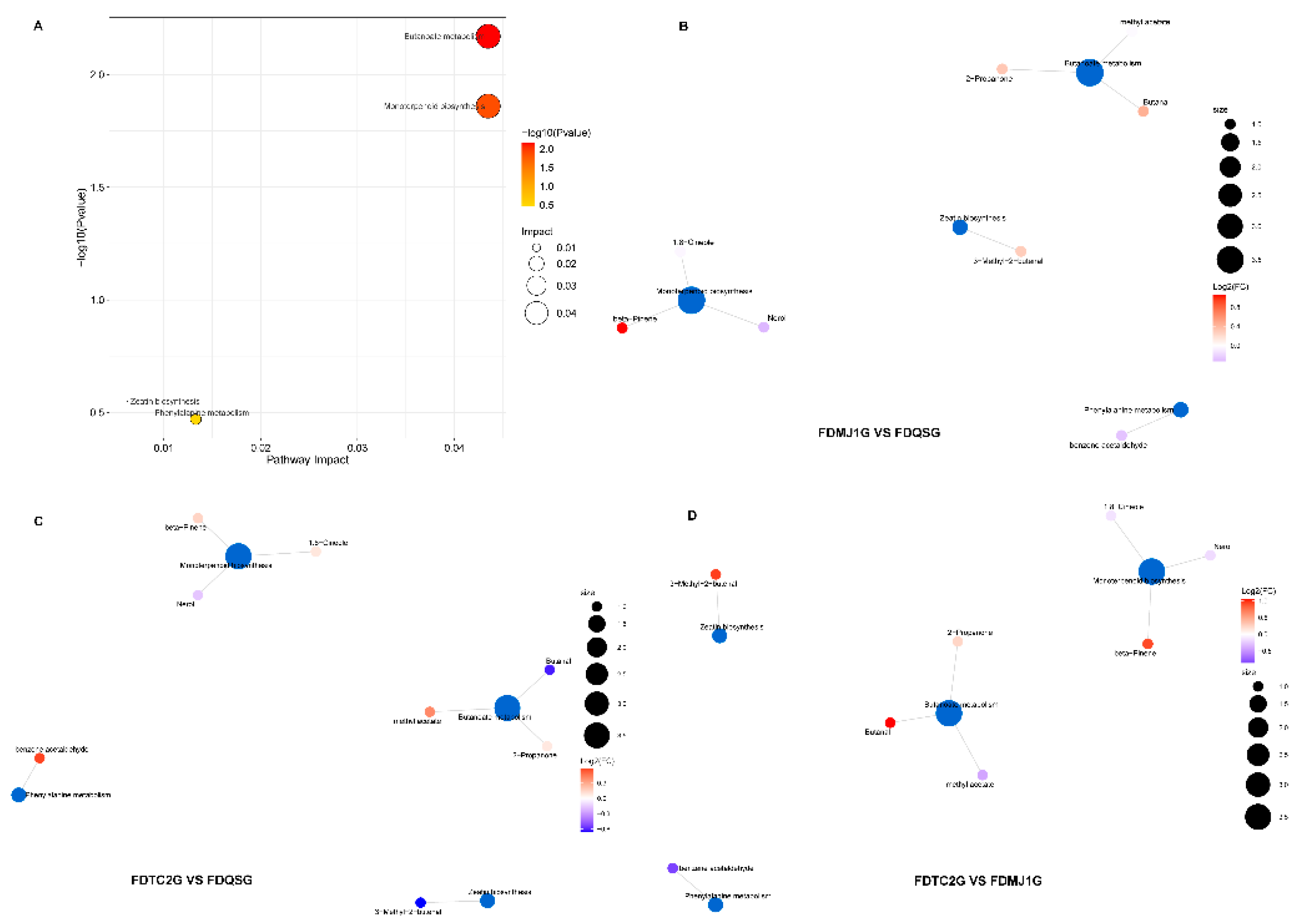

To further investigate the potential biosynthetic pathways associated with differential VOCs in FDG of varying tenderness, the identified VOCs were cross-referenced with the KEGG database to retrieve detailed information on their involved metabolic pathways. Enrichment analysis was subsequently performed to identify pathways and the annotated results are presented in

Figure 9 and

Table S7. A total of eight key VOCs were mapped to four metabolic pathways: butanoate metabolism, monoterpenoid biosynthesis, zeatin biosynthesis, and phenylalanine metabolism. Among them, butanoate metabolism and monoterpenoid biosynthesis were significantly enriched (

Figure 9A), indicating their critical roles in the metabolic differentiation of aroma profiles among green teas of different maturity stages. As illustrated in Figure 9B–D and detailed in

Table S7, the butanoate metabolism pathway was associated with 2-propanone, butanal, and methyl acetate; monoterpenoid biosynthesis was linked to nerol, β-pinene, and 1,8-cineole. In contrast, zeatin biosynthesis involved 3-methyl-2-butenal; and phenylalanine metabolism was associated with benzene acetaldehyde.

Pairwise comparison of VOC accumulation patterns revealed that 2-propanone (apple, pear aroma), butanal (chocolate), β-pinene (dry woody), and 3-methyl-2-butenal (sweet, fruity, nutty, almond) were predominantly enriched in FDMJ1G (one bud + one leaf), suggesting enhanced activity of butanoate metabolism and monoterpene biosynthesis at the intermediate maturity stage. In contrast, methyl acetate and benzene acetaldehyde, which contribute sweet, fruity, floral, honey, and cocoa-like aromas, were more highly expressed in FDTC2G (one bud + two leaves). Meanwhile, nerol, a floral monoterpene, was specifically enriched in FDQSG (single bud), supporting its strong floral character.

The KEGG-based enrichment results, when integrated with previous aroma and rOAV analyses, provide a coherent metabolic explanation for the VOC variations observed among the three tenderness grades. Specifically, FDMJ1G was characterized by a notable burst in monoterpenoid biosynthesis and active butanoate metabolism, consistent with its complex and balanced aroma profile. FDQSG was dominated by C6 aldehydes/alcohols (e.g., hexanal, (Z)-3-hexenol), mainly derived from the lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway, contributing to its fresh and grassy aroma[

35]. In contrast, FDTC2G showed enrichment in Maillard reaction products, esterification-derived volatiles, and phenylalanine-derived sweet-aromatic compounds such as benzene acetaldehyde, reflecting a maturity-dependent shift toward roasted and sweet-fruity notes.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the differential accumulation of aroma-related VOCs across leaf tenderness levels is closely tied to the dynamic modulation of key biosynthetic pathways, particularly butanoate metabolism and monoterpenoid biosynthesis. These pathways may serve as biochemical markers for evaluating and optimizing green tea quality in relation to raw material tenderness.