1. Introduction

Surface EMG (sEMG) signal represents neuromuscular activity during potential changes on the skin surface during muscle contraction. Surface EMG signal detection is a non-invasive detection method. It is important in the analysis of sports movements, clinical diagnostics, and rehabilitation. In particular, the most important movements in sports are performed using the muscles of the arms and legs.

In recent years, extensive research has been conducted on leg movement detection using EMG signals [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. These studies are mainly aimed at improving the control capabilities of rehabilitation technologies, smart prostheses, and exoskeleton robotic systems. In particular, various machine learning algorithms (SVM, RF, KNN, TCN - Temporal Convolutional Network) and feature extraction methods (in the time, frequency, time-frequency domains) have been used to classify movement from EMG signals. However, problems such as increasing classification accuracy, ensuring fatigue resistance, and real-time performance efficiency are still relevant. Therefore, approaches in this area and their results are analyzed by studying the existing literature (

Table 1).

In a study [

1] aimed at assessing the muscle activity of the LLL segment, an experimental method was developed to detect leg movements from EMG signals of human movement. Feature vectors were formed based on time-domain features (such as RMS, MAV, ZC), and based on this data, an SVM classifier was selected to detect 5 main leg movements. As a result of experiments conducted based on the proposed model, an average accuracy rate of 95.66% was recorded.

The potential of EMG signals is gaining importance in gait analysis and control of rehabilitation exoskeletons. The study evaluated the effectiveness of machine learning algorithms (KNN, RF, SVM) in classifying movements based on EMG signals obtained from 22 participants [

2]. As a result of experiments, the RF model with a combination of time and frequency domain features showed the highest result (92%).

Research is underway on smart prosthetic systems based on EMG signals to improve the quality of life of patients with lower limb amputations. In study, EMG signals from leg muscles were obtained and time domain features and the CatBoost algorithm were used to classify 5 movements (level walking, up the stairs, down the stairs and ramp ascent and descent) [

3].

An integrated approach of EEG and EMG signals based on discriminant correlation analysis (DCA) was considered for detecting bilateral LLL segment movements [

4]. EEG and EMG signals from 28 healthy participants were combined at the feature level and 5 types of classifiers were used to detect movements. The multimodal approach showed a particularly high performance (96.64%) with the linear discriminant analysis (LDA) classifier.

Next, a study was reviewed in which a new classification approach based on EMG and Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA) optimized for LLL segment motion detection was proposed [

5]. In the study, EMG signals recorded for 4 different motions (walking, up the stairs, down the stairs and sitting and standing) were processed and separated into feature vectors based on their time and frequency domain features. The SSA-SVM model was compared with the traditional SVM and TCN models in motion pattern detection. The SSA-SVM model achieved the highest classification accuracy (98.9%).

Inter-subject differences in sEMG signals are a major problem in detecting LLL segment movements in exoskeleton robots. In this regard, a motion detection method based on sEMG signals using non-negative matrix factorization, multiple nonlinear features, Fisher discriminant function, and GA-PSO optimized SVM is proposed [

6]. This approach achieved 96.03% accuracy in distinguishing 3 different movements in 11 healthy and 11 knee pathology participants.

Existing functional electrical stimulation (FES) devices are inconvenient to place and cannot detect the user’s movement intention or muscle fatigue, which limits their application in daily life. A new wearable FES system based on sEMG with electrodes specially woven for the user is an important step in this direction [

7]. The proposed deep learning-based parallel model FES system was tested on five participants and was able to detect lower leg movements and muscle fatigue with high accuracy (93.33%).

In order to improve human-computer interaction in the control of smart prosthetics, a method for detecting LLL segment movements based on sEMG signals is proposed. To overcome the problem of phase information loss in existing methods, the proposed approach implements S-transform-based energy density analysis and multi-channel synthesis [

8]. In this regard, sEMG signals obtained from six muscles of ten participants were analyzed based on four movements and a detection accuracy of 96% was achieved.

Although the number and location of sEMG electrodes have been widely studied to improve the classification accuracy in movement target detection, an increase in the number of channels also leads to an increase in processing time. In this regard, the classification accuracy of 1 to 4 sEMG channels installed in the right LLL segment of healthy subjects was compared [

9]. MAV, ZC, WL and SSC were used as feature vectors, which were reduced by Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and then the classification was performed using the SVM algorithm. The results showed that accuracy of over 90% could be achieved when using 3 or 4 channels, but the difference in accuracy between 2 and 4 channels did not exceed 5%, regardless of the number of samples being 500 or 1000, indicating that increasing the number of channels does not always guarantee maximum accuracy.

A novel solution is to use a CNN-Transformer-LSTM (CNN-TL) coupled model based on sEMG data to classify LLL segment movements with greater accuracy [

10]. sEMG signals from 20 participants were collected during 4 movements, analyzed in the time and frequency domains, and the selected features were fed into a neural network. The CNN-TL model achieved 96% accuracy and was 3.76%, 5.92%, and 14.92% higher than CNN, LSTM, and SVM, respectively.

The use of EMG signals is important in assessing and monitoring the physical condition of athletes involved in wrestling. In the literature reviewed in this regard, 8 general physical exercises and 2 technical movements specific to athletes were selected as the main evaluation criteria, and during their performance, EMG signals were recorded using sensors installed at the most active points of the body [

11]. Based on the EMG data, the athletes' movements were divided into 10 classes and analyzed using 5 different classification algorithms, and the RF model achieved an accuracy of 96.97%.

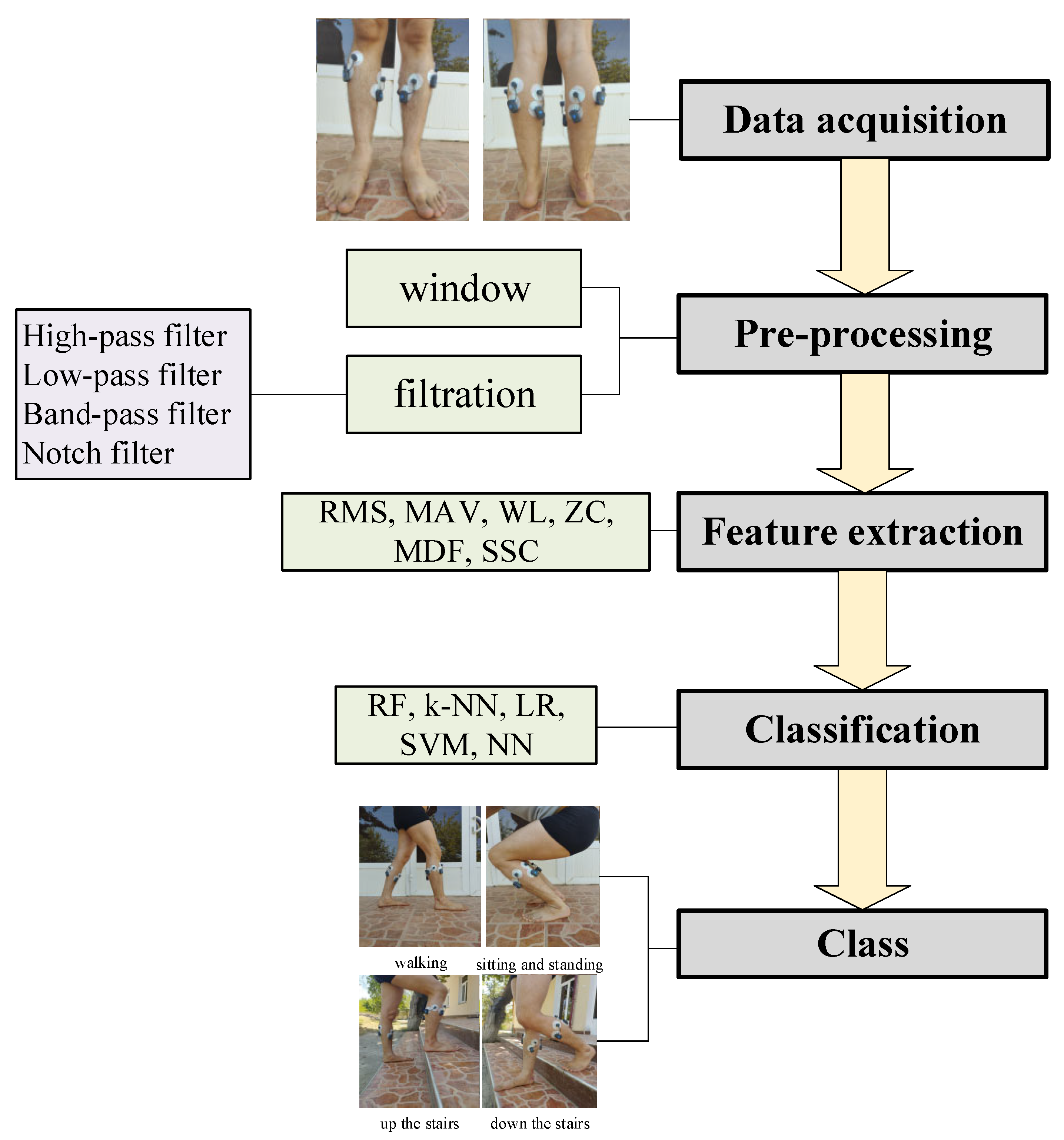

Figure 1 illustrates the sequence of the research organization process. In the first stage of the process, EMG signals are recorded in real time using 2 devices, and a data set is formed. In the next stage, the initial signal processing process is performed on the raw data. In this stage, the signals are cleaned of various noise and artifacts, and signal cleaning filtration operations are performed using low-pass filter high-pass filter, band-pass filter and notch filters. After the initial processing, a feature extraction stage is performed to identify the most important components of the signal. In the final stage, each leg movement is classified using machine learning or deep learning algorithms (SVM, KNN, RF, NN and LR).

2. Data Collection Organization

2.1. Devices

Special test-experiments were conducted to organize the DS. During the experiments, the athletes were adjusted taking into account the characteristics of the LLL segment movements.

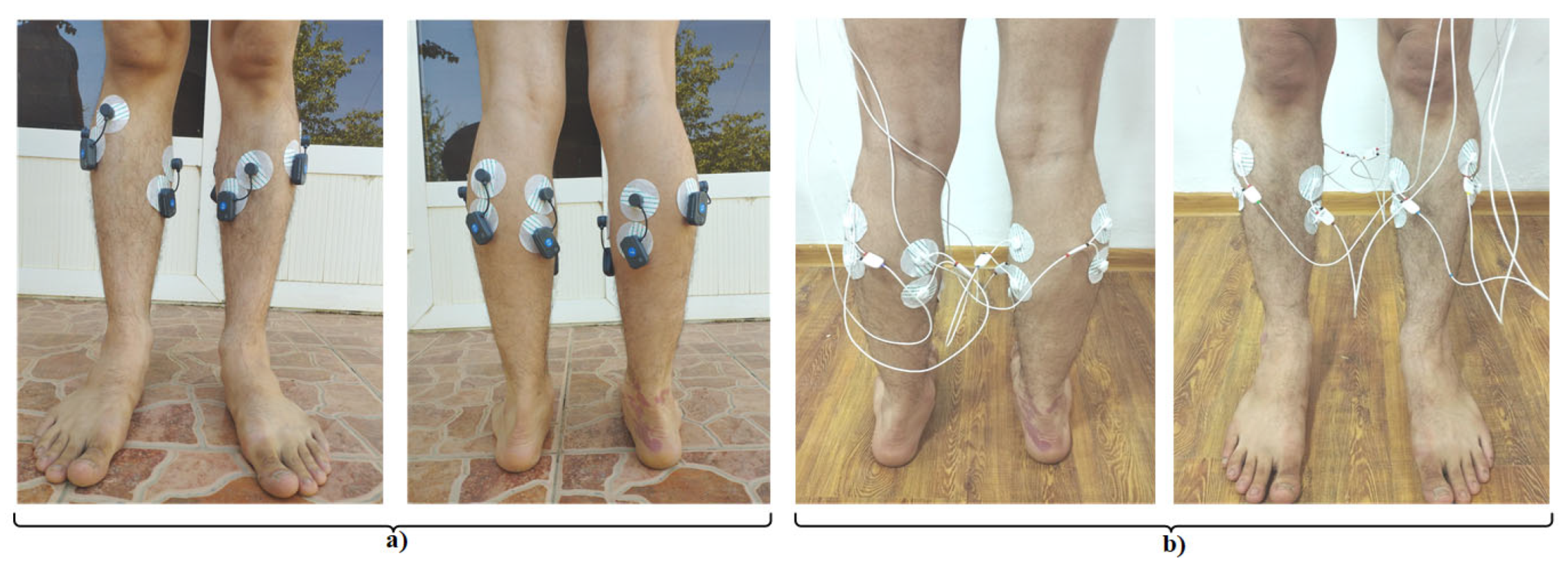

Two devices were used to record the EMG signal: the 8-channel BTS FreeEMG 1000 (

Figure 2, a) (Italy, BTS Bioengineering S.P.A.) and the 8-channel Biosignalsplux (

Figure 2, b) (Portugal, PLUX Wireless Biosignals S.A.) devices. The technical characteristics of these two devices are shown in

Table 2.

During the signal recording process, Ag/AgCl (silver chloride) electrodes were used and placed in the innervation zones of the muscles (

Figure 3, a, b).

The electrodes of the BTS FreeEMG and Biosignalsplux devices were selected to target the muscles that were most active during leg movements (

Figure 3). Based on the location of the human leg muscles and the correspondence between the muscles and movement, the following muscles were selected for each of the right and left legs: fibularis anterior, soleus, gastrocnemius lateral and gastrocnemius medial.

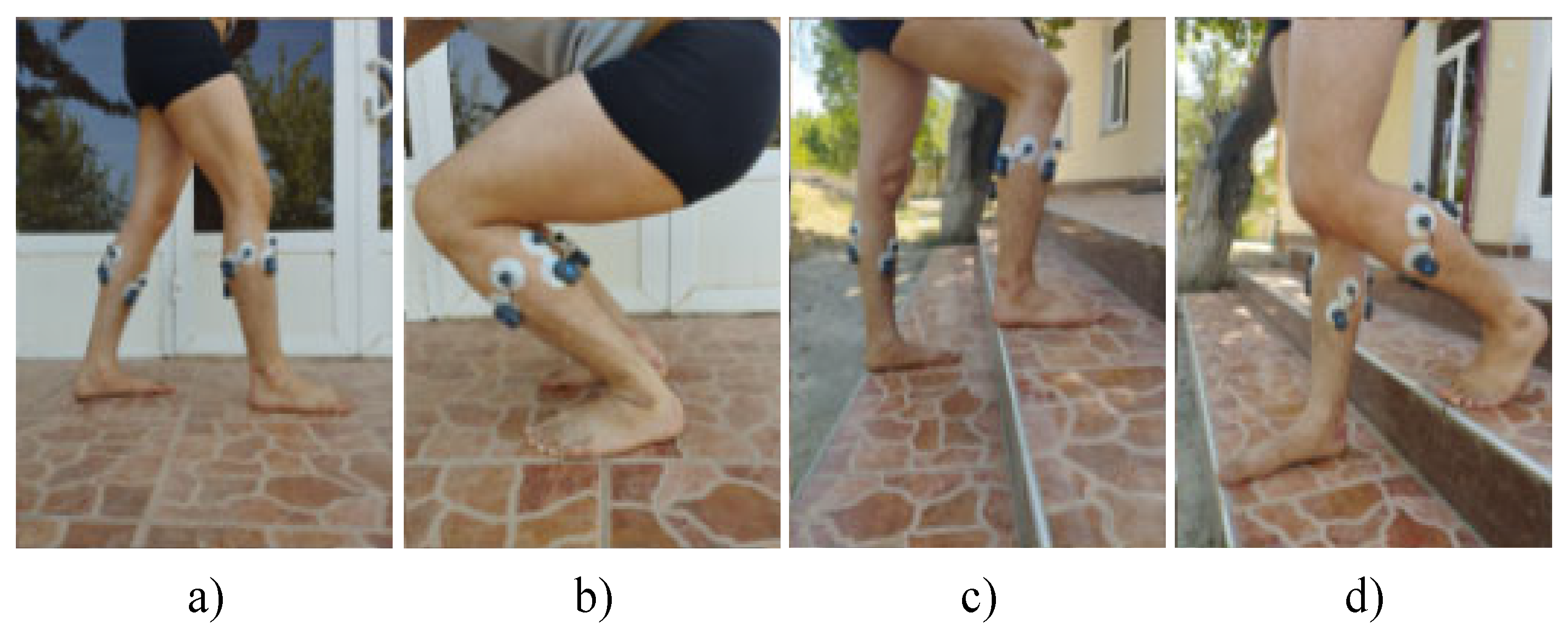

2.2. DS Structure

In the study, the main muscles of the LLL segment were selected, considering that the leg plays an important role in human movement. In addition, 4 important types of physical exercises that are most often used in the leg were selected: walking, sitting and standing, up the stairs, and down the stairs (

Figure 4).

During the study, a separate DS was created for each device. Each participant repeated the leg movements 5 times. Each session was held once a week. 15 sessions were held in 3 weeks. The volume of the DS is as follows:

The experiment was conducted on 25 students, including 11 girls and 14 boys.

As a sample, the representative segments of EMG signals recorded from the lateral gastrocnemius muscle of the left leg are visually presented in

Figure 5. This figure illustrates the time-domain variations of the EMG signals corresponding to each movement.

3. Feature Extraction and Classification

This section describes the step-by-step process of detecting athletes' leg movements based on EMG signals, pre-filtering the signals, and forming a set of features necessary for their classification. Characteristic features of movements are extracted, and modern and efficient classification algorithms are used to automatically identify movements based on these features.

As part of the study, analyses were conducted on EMG data sets collected separately using FreeEMG and Biosignalsplux devices. The data collected using each device was processed separately, and the accuracy of the classification models used to classify movements was compared. The experimental results analyzed the effect of the feature set on classification for different devices, as well as the performance of the algorithms, and their advantages and disadvantages were identified.

3.1. Filtration of EMG Signal

Factors that negatively affect the quality of EMG signals (noise) include: power line, motion artifacts, intermuscular interference, signal saturation, and physiological noise [

13]. Various filters are used to eliminate these factors. High-pass filters are used to reduce motion artifacts and smooth the signal at frequencies of 10–30 Hz. Low-pass filters remove high frequencies, separate the signal envelope, and are used before analog-to-digital conversion. Bandpass filters eliminate low frequencies in the range of 5–20 Hz and high frequencies in the range of 200–1000 Hz. Notch filters are effective in removing electrical noise at frequencies of 50 or 60 Hz [

14,

15].

3.2. Feature Extraction

It is not recommended to use raw EMG signals directly in classification algorithms, because these signals are very large and have a diverse nature. Therefore, the feature extraction method is used. Through this process, useful information is extracted from the signal and the data volume is reduced. The feature extraction technique is a necessary step for identifying effective patterns, and its effectiveness increases the accuracy of the classification result [

16].

Table 3 presents an analysis of the studies conducted on the features of EMG signals.

For efficient classification, the best 6 features were selected from the EMG signals based on the results of various scientific works.

The RMS feature has been used in many studies such as [

17,

18,

19,

22] and [

24]. In particular, 95% accuracy was achieved in studies [

22] and [

24]. This feature is a key parameter representing the total energy of the signal and provides stable results in classification. MAV is also found in many sources, for example, it was used in [

17,

18,

21,

23] and [

25]. In [

17], 97.44% accuracy was achieved and in [

23], 97% accuracy was achieved. This feature calculates the average power of the signal in a simple and efficient way. WL represents the overall complexity of the signal shape. It was used in [

18,

19,

23], and [

24], and in [

23] it gave 97% accuracy. This feature provides good discrimination in classification. ZC is the frequency variation of the signal by counting the zero crossing points. This feature was used in [

18,

19,

21], and [

25]. In particular, it showed 96% accuracy in [

21]. MDF is a frequency domain feature that indicates the spectral midpoint of the signal energy. It was used in [

18,

19], and [

23], and in [

23] it achieved 97% accuracy and in [

19] it achieved 93%. SSC represents the variability of the signal shape. This feature was used in [

18,

19], and [

21], and in [

21] it achieved 96% accuracy.

Six of the studied features - RMS, MAV, WL, ZC, MDF, and SSC - represent important aspects of the EMG signal and were selected as the best because they helped in classification with high accuracy in various studies. The remaining features - STD, VAR, Mean, and Skew - were not used because they showed low accuracy in the analyzed studies.

The six feature extraction models selected above are calculated as follows:

- ➢

RMS is a widely used time-domain feature in electromyographic (EMG) signal processing [

22]. RMS effectively reflects muscle contraction intensity and is sensitive to signal amplitude variations, making it valuable for assessing neuromuscular activity. It can be obtained as:

- ➢

MAV reflects the overall magnitude of muscle activation and is often used in real-time EMG-based control systes due to its computational simplicity and responsiveness to muscle contractions [

21] and is defined as:

- ➢

WL reflects the complexity and variability of the signal and is sensitive to both amplitude and frequency changes, making it useful for capturing the dynamic characteristics of muscle activity [

23] and is calculated as follows:

- ➢

ZC quantifies the number of instances where the signal amplitude transitions through zero, indicating a change in polarity [

21]. It can be obtained as:

- ➢

MDF represents the frequency point within the EMG power spectrum at which the spectrum is partitioned into two regions of equal power [

23] and is defined as:

- ➢

SSC characterize the frequency-related dynamics of EMG signals by quantifying the number of sign reversals in the signal’s slope within a defined time window [

19] and is calculated as follows:

3.3. Classification

Convolutional neural network (CNN) is a supervised learning model (SLM) that has shown high performance for temporal and visual data analysis. Many studies have used CNN models to achieve high performance [

27,

31]. However, when processing images in the classification process, high-performance GPUs are required.

In this study, five classification algorithms - RF, k-NN, LR, SVM, and NN - were used to classify athletes’ LLL segment movements for both DSs collected from two devices and the classification results were compared. These methods are known to work effectively with features in different structures and to ensure the stability of classification results [

11,

27,

28,

29].

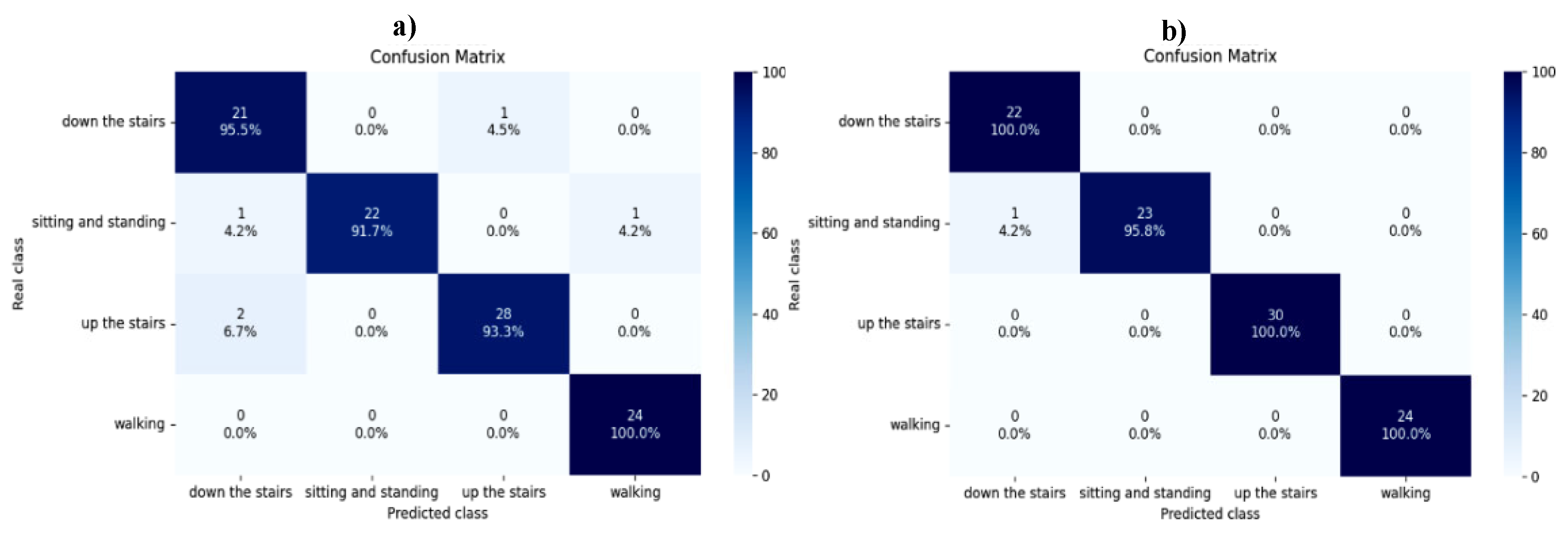

The confusion matrix serves as the main indicator in the evaluation of classification models. It allows you to visually represent the results of the selected classification algorithm. The evaluation results of the RF model used in this study for both DS are shown in

Figure 6 in the form of a confusion matrix, and the values of precision, recall, f1-score are shown in

Table 4.

The classification accuracy for the athletes' LLL segment movement classes was calculated separately using the 5 selected classification algorithms using both DSs, and a generalized evaluation was performed based on these results.

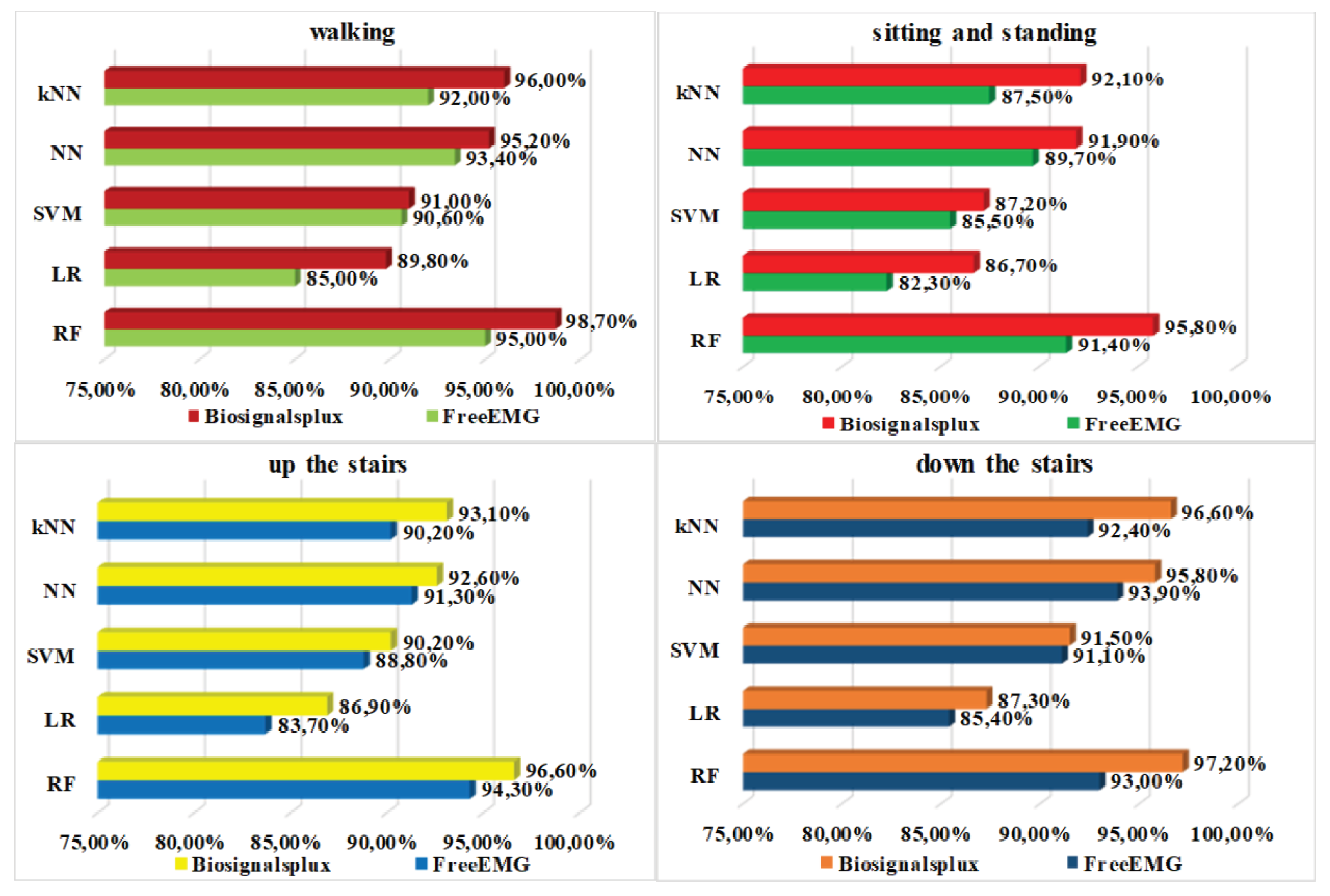

Experimental tests showed that all classifiers, based on the selected feature set, were able to classify athletes' footwork with high efficiency. The results differed in accuracy depending on the type of movement, and there were some significant differences between the classifiers (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

In this study, data were collected using two different devices, FreeEMG and Biosignalsplux, to detect athletes' leg movements through EMG signals, and classification was performed using five classification algorithms, RF, k-NN, LR, SVM, and NN. The movements were divided into four types: walking, sitting and standing, up the stairs, and down the stairs.

The analysis of the research results shows that the RF algorithm showed the highest accuracy among all tested classifiers in classifying movements. In both devices, the RF algorithm outperformed the other models in all types of movements. In particular, for walking movements, the FreeEMG device achieved 95% accuracy, and the Biosignalsplux device achieved 98.7%. For sitting and standing movements, the accuracies were 91.4% and 95.8%, for up the stairs 94.3% and 96.6%, and for down the stairs 93% and 97.2%, respectively. These indicators prove the effectiveness of the RF algorithm in identifying differences between complex movements, its stability, and its high adaptability to the characteristics of the EMG signal. When used in conjunction with the Biosignalsplux device, the RF algorithm provided the highest results in all cases.

In addition, the NN and kNN algorithms also showed high accuracy results. For example, in the walking movement, the NN algorithm worked with 93.4% accuracy in FreeEMG and 95.2% in Biosignalsplux. The kNN algorithm has achieved the highest results in other studies for classifying EMG signals [

30]. However, in our study, it performed worse than the RF and NN models. In the down the stairs movement, the kNN algorithm achieved 92.4% accuracy in FreeEMG and 96.6% in Biosignalsplux.

At the same time, the results of the SVM and LR algorithms were relatively lower. In the sitting and standing movements, LR showed 82.3% accuracy in the FreeEMG device and 86.7% accuracy in the Biosignalsplux device, while SVM achieved 85.5% and 87.2% accuracy, respectively. It was observed that the SVM and LR algorithms could not perform at the level of powerful models such as RF and NN in cases of complex, dynamic movements or in cases where there is similarity between movements. In some studies, high results were obtained by hybridizing the SVM model with methods such as ReliefF and Chi2 to improve its accuracy [

28,

31].

5. Conclusions

The article presents the recognition of athletes’ LLL segment movements based on EMG signals. A total of 25 athletes participated in the data collection process. The study analyzed previous work on movement recognition using EMG signals. It is worth noting that in this study, unlike other studies, data were collected separately from two different devices and their classification performance was compared. The Biosignalsplux device provided higher accuracy in movement classification compared to FreeEMG. The Biosignalsplux device consistently outperformed the FreeEMG device for each movement type and classifier, and this difference was especially evident in the cases of walking and down the stairs.

The EMG signals were filtered to remove various noise and artifacts. In the next stage, several literatures were analyzed and the RMS, MAV, WL, ZC, MDF and SSC features of the EMG signal that provide high accuracy in classification were selected and DSs were created using these features. RF, LR, SVM, NN and kNN classification algorithms were tested on the basis of EMG signals collected by FreeEMG and Biosignalsplux devices to recognize 4 types of leg movements of athletes. All algorithms showed an overall accuracy of 82.3% to 98.7%. The RF algorithm achieved the highest result, with an accuracy of up to 97% in the Biosignalsplux device. This result demonstrated the effectiveness of the RF algorithm in identifying differences between movements in the EMG signal.

Based on the above analysis, it can be said that the combination of the RF algorithm and the Biosignalsplux device can be recommended as the most optimal technological solution for detecting athletes' leg movements based on EMG signals.

Author Contributions

Methodology, K.Z., S.B., M.T., F.R., G.B.; software, S.B., M.T., F.R.; validation, K.Z., S.B., and S.M.; formal analysis, K.Z., G.P., G.S., and S.B.; resources, M.T., F.R., F.A., and G.P.; data curation, K.Z., S.B.; writing—original draft, K.Z., S.B., F.R., and M.T.; writing—review and editing, K.Z., S.B., and F.A.; supervision, K.Z., S.B., and M.T.; project administration, K.Z., and S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All used dataset are available online which open access.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- W. Ge, J. Zhao, F. Wang, C. Xu, Z. Yang and J. She, “Experimental Design of Lower-limb Movement Recognition Based on Support Vector Machine,” 2022 41st Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Hefei, China, 2022, pp. 6493-6497. [CrossRef]

- P. Mitsantisuk, S. Kiatthaveephong, P. Autthasan and T. Wilaiprasitporn, “MotionXpert: EMG-Based Classification for Optimized Lower-Limb Motion Detection,” 2024 IEEE-EMBS Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Sciences (IECBES), Penang, Malaysia, 2024, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- A. K, S. Vinoth Krishna, V. Hamsadhwani, P. A. Karthick, S. Kumaravel and N. Sivakumaran, “Recognition of Lower Limb Movements From the Time Domain Features of Surface EMG and Catboost Classifier,” 2024 International Conference on Brain Computer Interface & Healthcare Technologies (iCon-BCIHT), Thiruvananthapuram, India, 2024, pp. 70-73. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Al-Quraishi, I. Elamvazuthi, T. B. Tang, M. Al-Qurishi, S. Parasuraman and A. Borboni, “Multimodal Fusion Approach Based on EEG and EMG Signals for Lower Limb Movement Recognition,” in IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 21, no. 24, pp. 27640-27650, 15 Dec.15, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Han and Q. Tao, “A fine sensing method of lower limb movement electromyography based on sparrow search algorithm optimised support vector machine*,” 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), Koh Samui, Thailand, 2023, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Tu, P.; Li, J.; Wang, H. Lower Limb Motion Recognition with Improved SVM Based on Surface Electromyography. Sensors 2024, 24, 3097. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Bai, Z.; Yan, P.; Liu, H.; Shao, L. Recognition of Human Lower Limb Motion and Muscle Fatigue Status Using a Wearable FES-sEMG System. Sensors 2024, 24, 2377. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xu, G.; Pei, J.; Luo, D.; Li, H.; Du, C.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, S. Lower Limb Motion Recognition Based on Surface Electromyography Decoding Using S-Transform Energy Concentration. Machines 2025, 13, 346. [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Pérez, D.C.; Martínez-Prado, M.A.; Gómez-Loenzo, R.A.; Paredes-García, W.J.; Rodríguez-Reséndiz, J. A Study of Movement Classification of the Lower Limb Based on up to 4-EMG Channels. Electronics 2019, 8, 259. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Tao, Q.; Su, N.; Liu, J.; Chen, Q.; Li, B. Lower Limb Motion Recognition Based on sEMG and CNN-TL Fusion Model. Sensors 2024, 24, 7087. [CrossRef]

- Kudratjon Zohirov, Rashid Nasimov, Sardor Boykobilov, Gulrukh Sherboboyeva, Mirjakhon Temirov, and Mamadiyor Sattorov. 2025. An EMG Signal Based Approach for Assessing the Physical Condition of Athletes in Wrestling. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Future Networks & Distributed Systems (ICFNDS '24). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 602–608. [CrossRef]

- L. Fedorová, V. Rajťúková, T. Tóth and J. Živčák, “EMG system application in muscle parametrization of the upper extremities,” 2014 IEEE 12th International Symposium on Applied Machine Intelligence and Informatics (SAMI), Herl'any, Slovakia, 2014, pp. 85-89. [CrossRef]

- M. Ayachi and H. Seddik, “Overview of EMG Signal Preprocessing and Classification for Bionic Hand Control,” 2022 IEEE Information Technologies & Smart Industrial Systems (ITSIS), Paris, France, 2022, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Chand, R., Tripathi, P., Mathur, A., & Ray, K. C. (2010). FPGA implementation of fast FIR low pass filter for EMG removal from ECG signal. 2010 International Conference on Power, Control and Embedded Systems. [CrossRef]

- K. Zohirov, “A New Approach to Determining the Active Potential Limit of an Electromyography Signal,” 2023 3rd International Conference on Technological Advancements in Computational Sciences (ICTACS), Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2023, pp. 291-294. [CrossRef]

- Pancholi, S. and Joshi, A.M., 2019. Electromyography-Based Hand Gesture Recognition System for Upper Limb Amputees. IEEE Sensors Letters, 3 (3), pp. 1 - 4): 1-4. [CrossRef]

- M.B.Prakash, H.M.Harish, M.Niranjana Kumara. Time Domain Analysis of EMG Signals using KNN and SVM Techniques WSEAS TRANSACTIONS on SIGNAL PROCESSING. [CrossRef]

- Sara Abbaspour, Maria Linden, Hamid Gholamhosseini, Autumn Naber, Max Ortiz-Catalan. “Evaluation of surface EMG-based recognition algorithms for decoding hand movements”. 2020 Jan;58(1):83-100. Epub 2019 Nov 21. [CrossRef]

- Cemil Altin, Orhan Er. “Comparison of Different Time and Frequency Domain Feature Extraction Methods on Elbow Gesture’s EMG”. European Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies May-August 2016 Volume 2, Issue3.

- S.Raurale, J.McAllister, & J.Martinez del Rincon. “EMG WRIST-HAND MOTION RECOGNITION SYSTEM FOR REAL-TIME EMBEDDED PLATFORM”. In 2019 International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing (ICASSP) (pp. 1523-1527). Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadreza Asghari Oskoei and Huosheng Hu. Support vector machine-based classification scheme for myoelectric control applied to upper limb. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 55(8):1956–1965, 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. Rojas-Martinez, M. A. Mananas, and J. Alonso. High-density surface EMG maps from upper-arm and forearm muscles. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 9:85– 85, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Maria V Arteaga, Jenny C Castiblanco, Ivan F Mondragon, Julian D Colorado, and Catalina Alvarado-Rojas. Emg-driven hand model based on the classifica tion of individual finger movements. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 58:101834, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jinxian Qi, Guozhang Jiang, Gongfa Li, Ying Sun, and Bo Tao. Surface emg hand gesture recognition system based on pca and grnn. Neural Computing and Applications, 32(10):6343–6351, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hyeon-min Shim and Sangmin Lee. Multi-channel electromyography pattern classification using deep belief networks for enhanced user experience. Journal of Central South University, 22(5):1801–1808, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Laganà, F.; Pratticò, D.; Angiulli, G.; Oliva, G.; Pullano, S.A.; Versaci, M.; La Foresta, F. Development of an Integrated System of sEMG Signal Acquisition, Processing, and Analysis with AI Techniques. Signals 2024, 5, 476-493. [CrossRef]

- K. Zohirov, “Classification Of Some Sensitive Motion Of Fingers To Create Modern Biointerface,” 2022 International Conference on Information Science and Communications Technologies (ICISCT), Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2022, pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Muguro, J.K.; Laksono, P.W.; Rahmaniar, W.; Njeri, W.; Sasatake, Y.; Suhaimi, M.S.A.b.; Matsushita, K.; Sasaki, M.; Sulowicz, M.; Caesarendra, W. Development of Surface EMG Game Control Interface for Persons with Upper Limb Functional Impairments. Signals 2021, 2, 834-851. [CrossRef]

- Miaoulis, D.; Stivaros, I.; Koubias, S. Developing a Novel Muscle Fatigue Index for Wireless sEMG Sensors: Metrics and Regression Models for Real-Time Monitoring. Electronics 2025, 14, 2097. [CrossRef]

- Zaim, T.; Abdel-Hadi, S.; Mahmoud, R.; Khandakar, A.; Rakhtala, S.M.; Chowdhury, M.E.H. Machine Learning- and Deep Learning-Based Myoelectric Control System for Upper Limb Rehabilitation Utilizing EEG and EMG Signals: A Systematic Review. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 144. [CrossRef]

- Pires, N.; Macedo, M.P. A Bimodal EMG/FMG System Using Machine Learning Techniques for Gesture Recognition Optimization. Signals 2025, 6, 8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).