1. Introduction

Owing to the ability to isolate mechanical waves within specific frequency ranges, bandgap mechanical metamaterials are broadly applicable in engineering vibration and sound insulation. Vasconcelos et al. [

1] proposed a metamaterial-based interface to attenuate pressure waves induced by the impact hammer acting on the top of an offshore monopile. Zuo et al. [

2] applied a star-shaped metamaterial to the shell of an underwater vehicle to reduce engine noise emission. A lattice-structured metamaterial capable of both sound insulation and ventilation was developed by Li et al. [

3], and can be used as a roadside noise barrier. Seismic metamaterials composed of periodically arranged building foundations have been validated for shielding seismic waves and train-induced vibrations [

4]. Replacing conventional aggregates with local resonant masses [

5] enables concrete structural members to function as metamaterials capable of dissipating elastic waves induced by dynamic loads.

Dynamic loads within the bandgap may still induce significant structural responses in the metamaterials, which is known as bandgap resonance [

6]. For example, Zhang et al. [

7] designed a negative stiffness metamaterial that exhibits a peak in its frequency response curve within the bandgap range. Jiang et al. [

8] designed negative stiffness metamaterials whose frequency response curves do not exactly match their bandgaps. The chiral and hexagonal lattices proposed by Li et al. [

9,

10] also experience large frequency responses within the bandgap ranges. Bandgap resonance can similarly be observed in the frequency response curves of the metamaterials studied in Ref. [

11,

12,

13,

14]. The presence of bandgap resonance suggests that certain eigenfrequencies of the metamaterial lie within the bandgap range, thereby compromising its vibration isolation performance. Therefore, it is necessary to prevent this phenomenon in the engineering design of bandgap metamaterials.

Bandgap resonance attracted early attention in the field of solid-state physics. In calculating the specific heat capacity of crystals, periodically arranged atoms are modelled as vibrating one-dimensional atomic chains. Thus, some early studies focused on the correspondence between the eigenfrequency spectra and the dispersion functions of finite atomic chains. Born [

15] studied two types of one-dimensional atomic chains and concluded that the spectrum of a finite atomic chain with free ends is consistent with its dispersion function. Wallis [

16], however, identified an eigenfrequency within the bandgap while analyzing the spectrum of a finite diatomic chain. Since then, similar phenomena have been widely observed in elastomers [

17,

18,

19,

20].

Calculating the dispersion function via Bloch’s theorem assumes that the metamaterials exhibit translational symmetry [

21], necessitating that they be either infinitely extended or subjected to periodic boundary conditions [

22]. However, finite metamaterials in engineering possess non-periodic boundaries, so their spectra deviate from the dispersion functions. This suggests that the existence of bandgap resonance is determined by the boundary conditions. Bastawrous et al. [

6] introduced boundary conditions as perturbations to the dynamic stiffness matrix and analytically derived a closed-form condition for the existence of bandgap resonance in finite diatomic chains. Guo et al. [

23] and Sugino et al. [

24] solved dynamic differential equations with boundary conditions substituted to obtain the spectra of finite two-phase plates. Jin et al. [

25] incorporated boundary conditions in the form of a Fourier series into the dynamic stiffness matrix and solved the spectrum of a two-phase metamaterial plate. By comparing the obtained spectra with the dispersion functions of the metamaterials, the existence of bandgap resonance can be identified.

Analytical calculations of the spectra of metamaterials require explicit expressions for the eigenfrequencies, which poses a substantial mathematical challenge. As a result, existing studies have primarily focused on simple systems, such as two-phase plates or diatomic chains [

6,

23,

24,

25]. However, metamaterials designed for specific bandgaps are usually complex, making it difficult to analytically solve their spectra. Therefore, to ensure the vibration isolation performance of a designed metamaterial, bandgap resonance should preferably be avoided without solving the spectrum.

This paper proposes a design method for stretch-dominated metamaterials that achieve expected bandgaps while avoiding bandgap resonance. The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 derives the sufficient condition for avoiding the bandgap resonance in stretch-dominated metamaterials.

Section 3 presents the equations for designing the unit cell parameters under symmetry constraint. A design example is illustrated in

Section 4, which is used to validate both the sufficient condition and the corresponding design method. Finally,

Section 5 draws some conclusions.

2. Sufficient Condition for Avoiding Bandgap Resonance

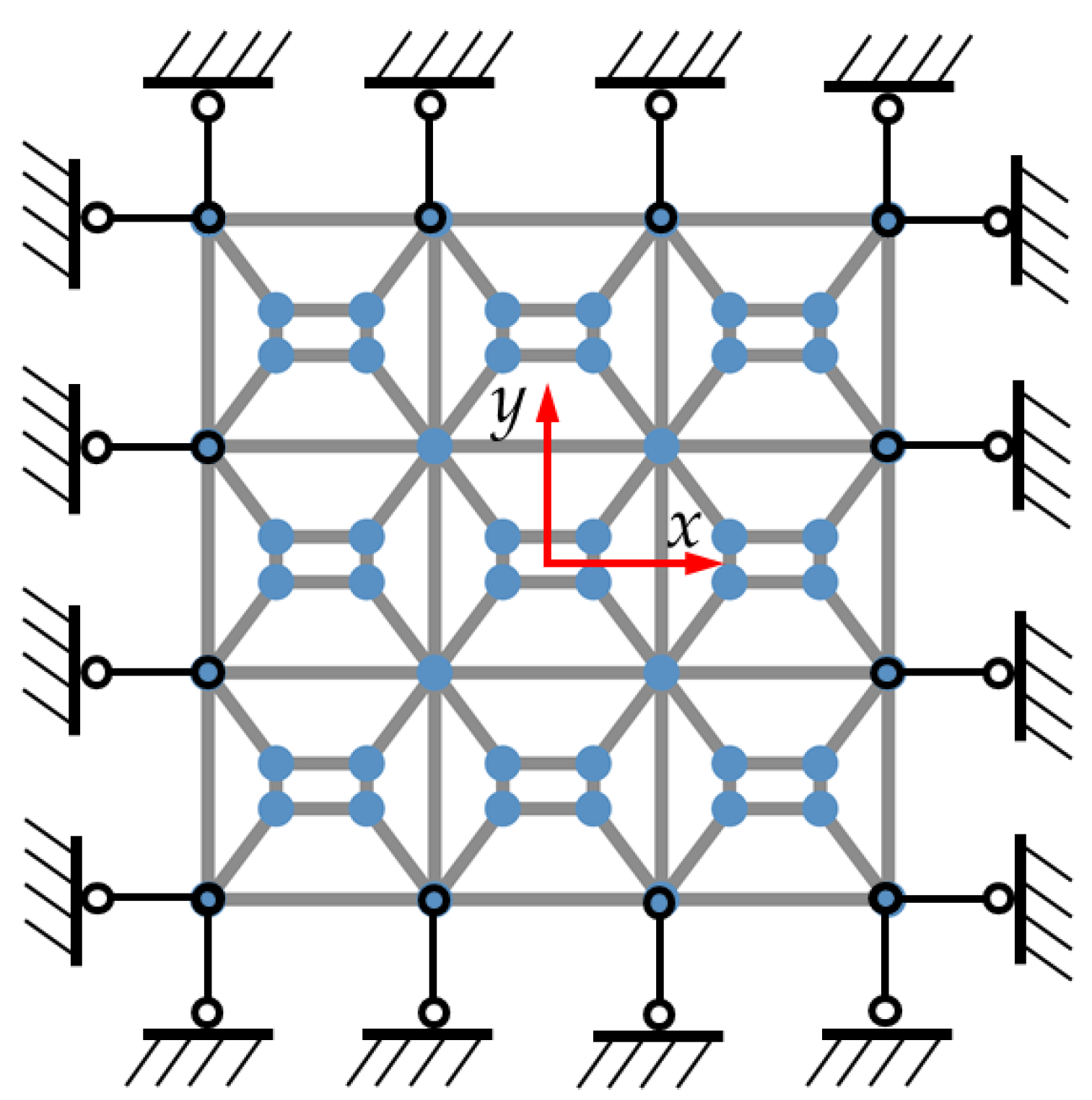

A two-dimensional stretch-dominated metamaterial is used as an example to demonstrate the derivation of the sufficient condition for avoiding bandgap resonance. As shown in

Figure 1, a 3×3 metamaterial, denoted by m, is modelled as a pin-jointed bar structure and subjected to a boundary condition that can be practically realized in engineering.

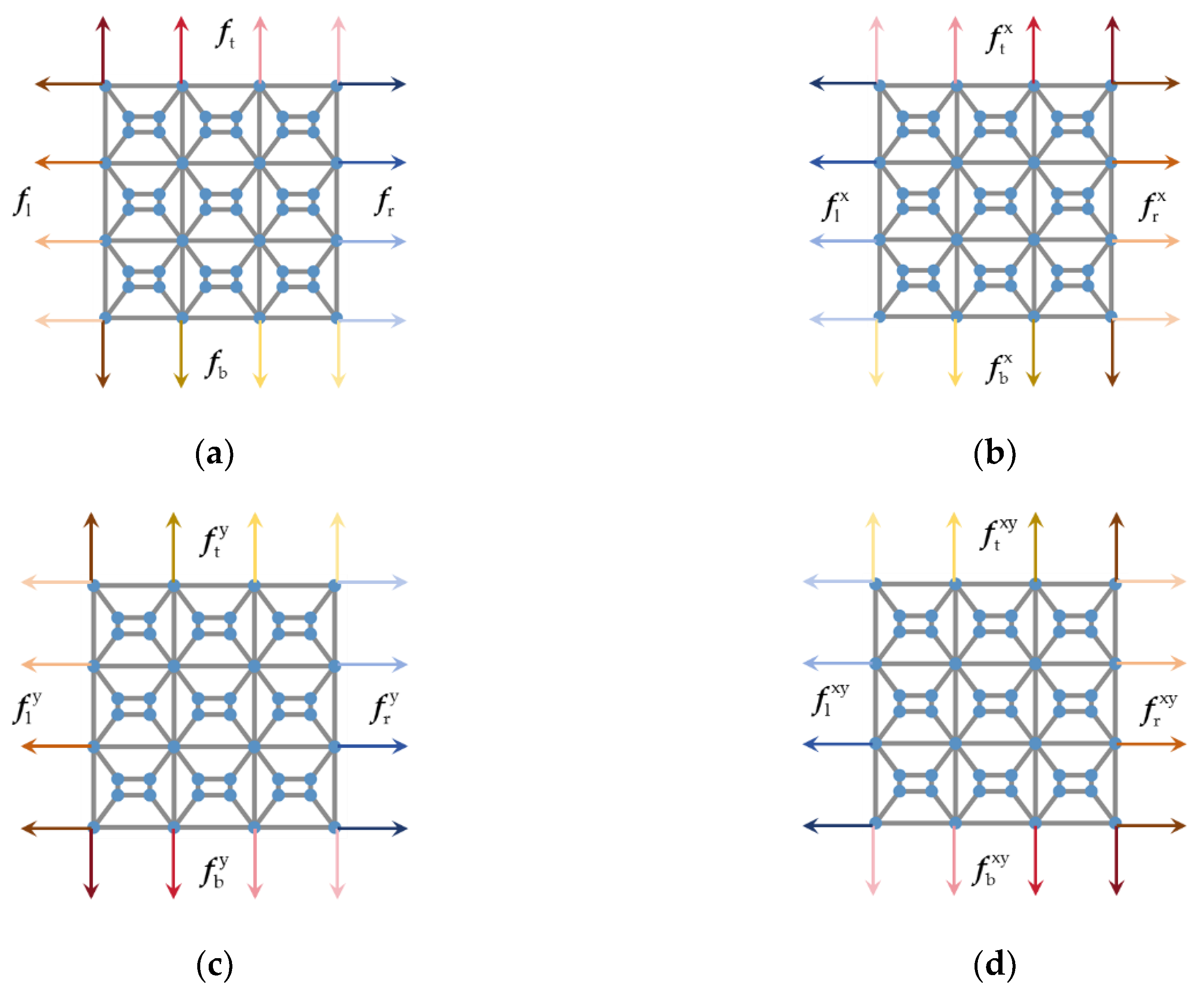

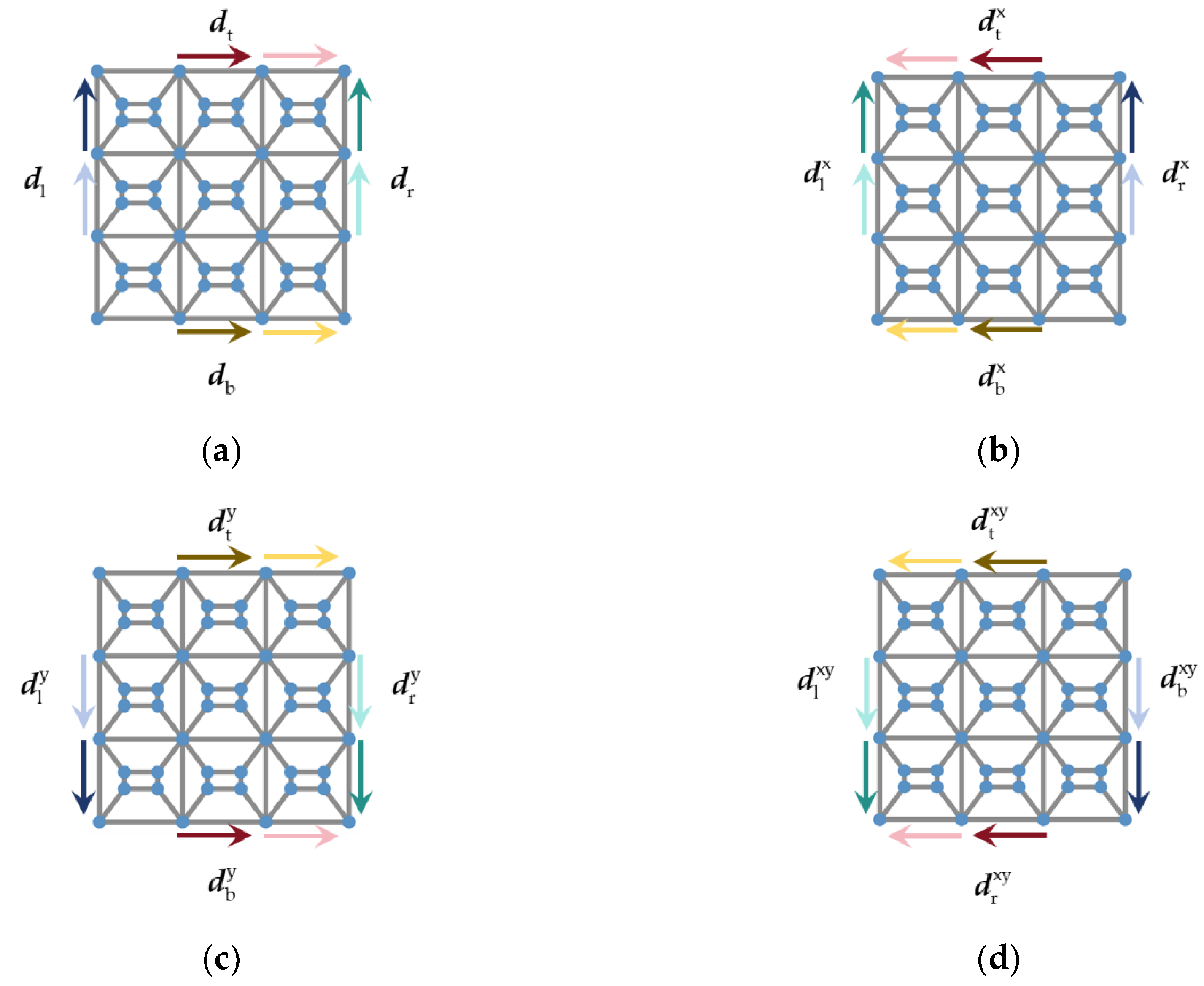

Figure 2a and

Figure 3a show the distributions of modal forces and displacements on the boundaries corresponding to any eigenfrequency

ωj of m. Except for the corner nodes, the horizontal components of the node forces are zero on the top and bottom edges, while the vertical components are zero on the left and right edges. Similarly, the vertical components of the node displacements are zero on the top and bottom edges, and the horizontal components are zero on the left and right edges. Thus, it can be derived that

where

dt/b and

ft/b are the displacement and force vectors of the nodes on the top or bottom edge;

dl/r and

fl/r are the displacement and force vectors of the nodes on the left or right edge;

and

(

u=1, …,

nt/b) are the

x and

y components of the displacement of the

u-th node on the top or bottom edge, respectively,

and

(

u=1, …,

nt/b) are the corresponding force components;

and

(

u=1, …,

nl/r) are the

x and

y components of the displacement of the

u-th node on the left or right edge,

and

(

u=1, …,

nl/r) are the corresponding force components;

nt/b is the number of nodes on the top or bottom edge, and

nl/r is that on the left or right edge; the superscript T denotes the transpose of a vector or matrix.

Spatial inversion of m in the

x-direction (i.e., mirroring across the

y-axis) yields the metamaterial m

x. The distributions of modal forces and displacements on the boundaries are shown in

Figure 2b and

Figure 3b, and the corresponding frequency remains constant at

ωj. According to

Figure 2b and

Figure 3b, the boundary node displacement and force vectors of m

x can be written as

Spatial inversion of m in the

y-direction (i.e., mirroring across the

x-axis) yields the metamaterial m

y. The distributions of modal forces and displacements on the boundaries are shown in

Figure 2c and

Figure 3c, and the corresponding frequency remains constant at

ωj. According to

Figure 2c and

Figure 3c, the boundary node displacement and force vectors of m

y can be written as

Spatial inversion of m

x in the

y-direction yields the metamaterial m

xy. The distributions of modal forces and displacements on the boundaries are shown in

Figure 2d and

Figure 3d, and the corresponding frequency remains constant at

ωj. According to

Figure 2d and

Figure 3d, the boundary node displacement and force vectors of m

xy can be written as

As can be seen from

Figure 2 and Eqs. (1), (2), (5), (6), (9), (10), (13) and (14), the boundary node displacement vectors satisfy

Moreover,

Figure 3 and Eqs. (3), (4), (7), (8), (11), (12), (15) and (16) indicate that the boundary node force vectors satisfy the following relationships except for corner nodes:

Let nodes 1, 2, 3 and 4 denote the lower right corner node of m, the lower left corner node of m

x, the upper right corner node of m

y, and the upper left corner node of m

xy, respectively. Then, their node forces satisfy

Eqs. (17)– (19) indicate that the corresponding nodes on the bottom edge of m and the top edge of m

y have identical displacements, and their node forces are in equilibrium. The same relationship holds between the right edge of m and the left edge of m

x, the top edge of m

xy and the bottom edge of m

x, and the right edge of m

y and the left edge of m

xy. This suggests that m, m

x, m

y, and m

xy can be merged into a new structure M.

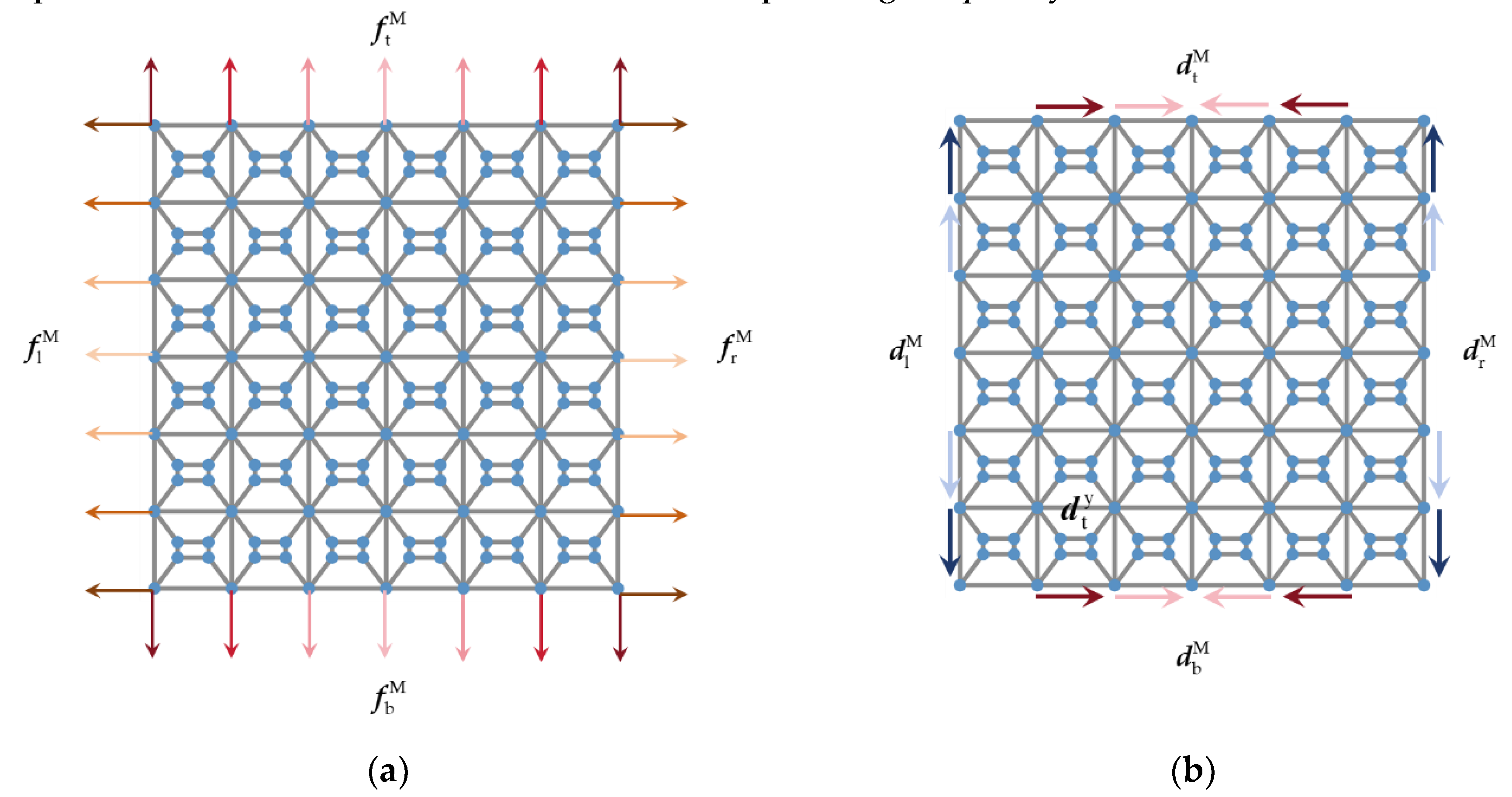

Figure 4a and

Figure 4b show the distributions of its modal forces and displacements on the boundaries, and the corresponding frequency is still

ωj.

The boundary node displacement and force vectors of M can be written as

According to Eqs. (20)– (27), the node displacements and forces on the boundaries of M satisfy the periodic boundary condition [

26]. However, M may not be a translationally symmetric metamaterial because m is not necessarily identical to m

x, m

y and m

xy. Conversely, if m remains unchanged after the spatial inversions in both the

x- and

y-directions, M is a metamaterial satisfying the periodic boundary condition. This requires that the unit cell of m exhibits spatial inversion symmetry along

x- and

y-axes. In this case, the spectrum of M must coincide with the dispersion function obtained via Bloch’s theorem, indicating that none of the eigenfrequencies of M, including

ωj, lie within the bandgap. Since any eigenfrequency

ωj of m lies outside the bandgap, the metamaterial m can avoid bandgap resonance.

The above derivation can be generalized to three-dimensional metamaterials and some other boundary conditions. For two- and three-dimensional cases, the applicable boundary conditions are listed in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively.

In

Table 1 and

Table 2,

x,

y and

z represent nodes on the boundaries normal to the

x-,

y- and

z-directions, respectively; c

1, c

2 and c

3 represent constraints applied in the

x-,

y- and

z- directions, respectively.

In summary, the sufficient condition for avoiding bandgap resonance can be express as

Theorem 1.A d-dimensional metamaterial can avoid bandgap resonance if both of the following conditions are satisfied: 1. The unit cell exhibits spatial inversion symmetry along all d coordinate axes; 2. One of the boundary conditions listed inTable 1or

Table 2is imposed.

3. Perturbation of Bandgap

The following generalized characteristic equation [

26,

27,

28,

29] can be used to solve the dispersion function of the metamaterial consisting of unit cells with spatial inversion symmetry:

where

;

and

are the

d·

n×

d·

n stiffness and mass matrices of the unit cell, respectively, and their explicit forms can be found in Ref. [

29];

n is the number of nodes in the unit cell; the superscript H denotes the Hermite transpose;

is the

d·

n×

d·

r reduction matrix introducing Bloch’s theorem [

29], and

r is the number of inequivalent nodes [

29];

ω(

k) is the circular frequency, and

k is the

d×1 wave vector [

30]. Once

k is given, the generalized eigenvalues

ωj(

k)

2 (

j=1, 2, …,

d·

r) and their corresponding eigenvectors

(

d·

r×1) can be solved via Eq. (28). Thus, the dispersion function of the metamaterial, i.e., the

k‒

ω relation, is established with a total of

d·

r branches of

k‒

ωj.

According to matrix perturbation theory [

28,

29], the perturbation of branch

j caused by the increments of unit cell parameters, including node coordinates and element cross-sectional areas, can be calculated by

where

is the (

b+

d·

n)×1 incremental unit cell parameter vector;

b is the number of elements in the unit cell;

Ai (

i=1,…,

b) is the cross-sectional area of the

i-th element;

(

p=1, …,

n,

k=1, ..,

d) is the

k-th coordinate of the

p-th node.

Oj(

k) is a 1×(

b+

d·

n) row vector whose

v-th component is

where

v=

b+

d·(

p-1)+

k for the second term;

is the eigenvector normalized by

;

,

. The explicit forms of

,

,

and

are given in Ref. [

29].

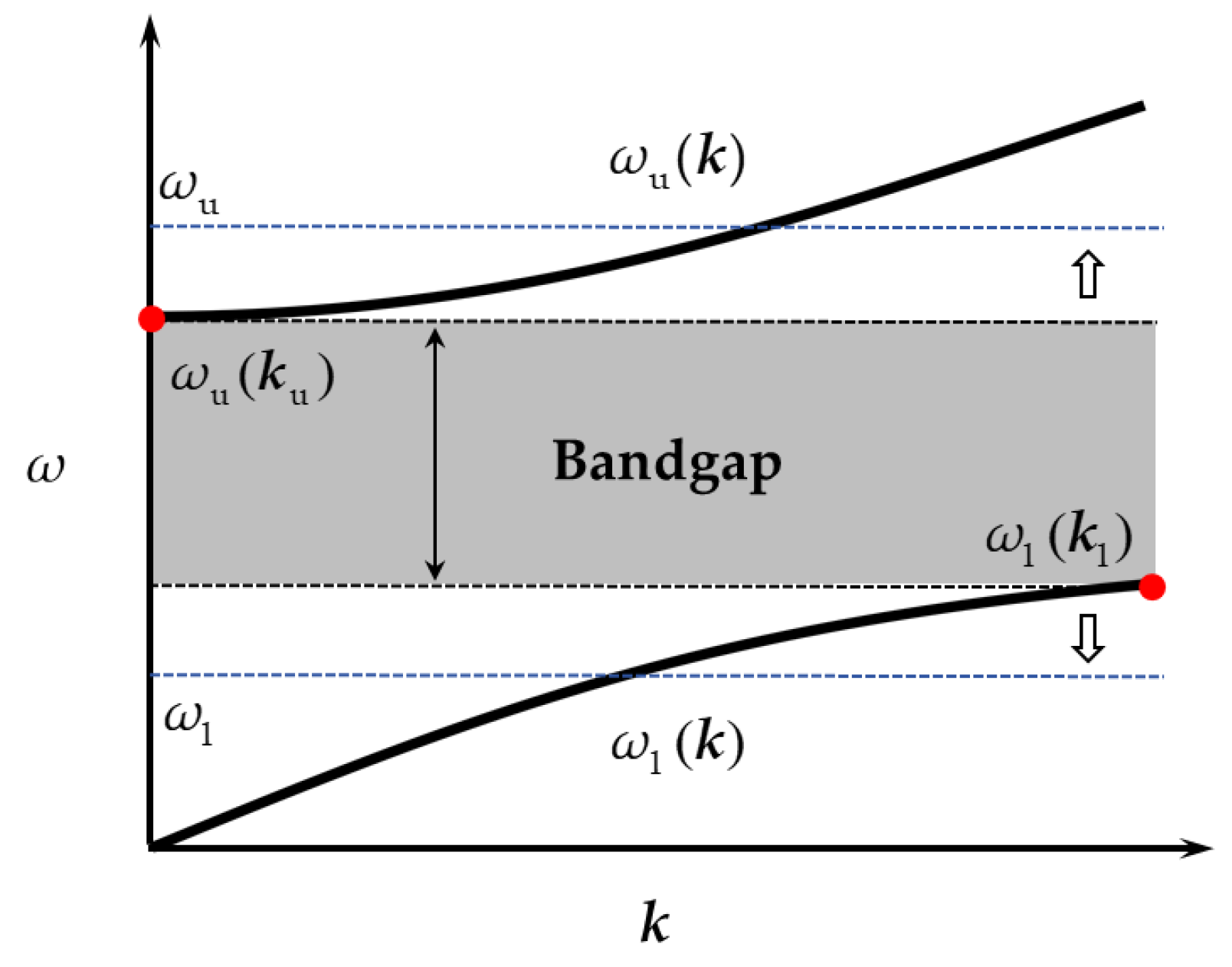

An illustrative bandgap between the lower branch

ωl(

k) and the upper branch

ωu(

k) is shown in

Figure 5. The range of the bandgap is [

ωl(

kl),

ωu(

ku)], where

kl and

ku are the wave vectors corresponding to the maximum value of

ωl(

k) and the minimum value of

ωu(

k), respectively. Substituting

kl and

ku into Eq. (29), the perturbation of

ωl(

kl) and

ωu(

ku) can be expressed as

The difference between the expected bandgap [

ωl,

ωu] shown in

Figure 5 and the current bandgap is Δ

ωt={

ωu-

ωu(

ku),

ωl-

ωl(

kl)}

T. By substituting Δ

ωt into Eq. (31), Δ

ε for adjusting unit cell parameters and tuning bandgap can be solved. However, Δ

ε must satisfy spatial inversion symmetry, or it will break the symmetry of the unit cell.

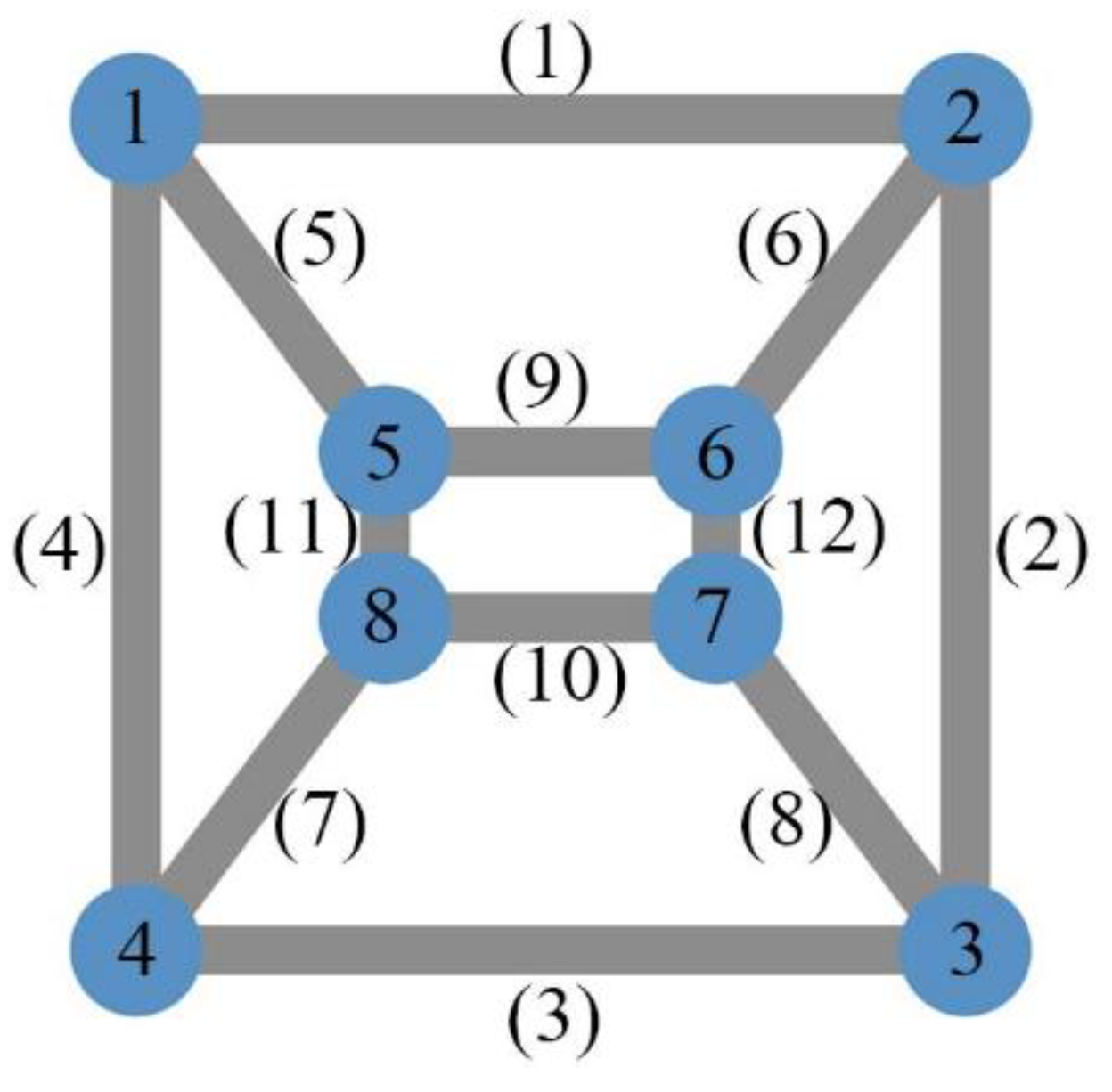

Figure 6 shows a unit cell with 8 nodes and 12 elements. An increment vector adjusting the coordinates of nodes 5, 6, 7 and 8 with

,

,

and

satisfies spatial inversion symmetry, and is denoted as Δ

εg. Similarly, Δ

A5=1, Δ

A6=1, Δ

A7=1 and Δ

A8=1 can be assembled into another Δ

εg satisfying spatial inversion symmetry. If there are at most

τ linearly independent Δ

εg, then any incremental unit cell parameter vector satisfying spatial inversion symmetry can be expressed as

where Δ

κ is an arbitrary

τ×1 coefficient vector.

Substituting Eq. (32) and Δ

ωt into Eq. (31), it can be obtained that

The least squares solution [

31] of Eq. (33) is

By substituting Eq. (34) into Eq. (32), the resulting Δεsym can be used to adjust the unit cell parameters and tune the bandgap under the constraint of spatial inversion symmetry.

The unit cell parameters should be modified in small steps due to the strong nonlinearity in their relationship with the dispersion function. Thus, Δ

εsym is scaled by

where

s is a specified scaling factor; ||•|| denotes the 2-norm of the vector. The expected bandgap can be obtained by iteratively adjusting the unit cell parameters with Δ

εs until ||Δ

ωt|| falls below a specified tolerance

c.

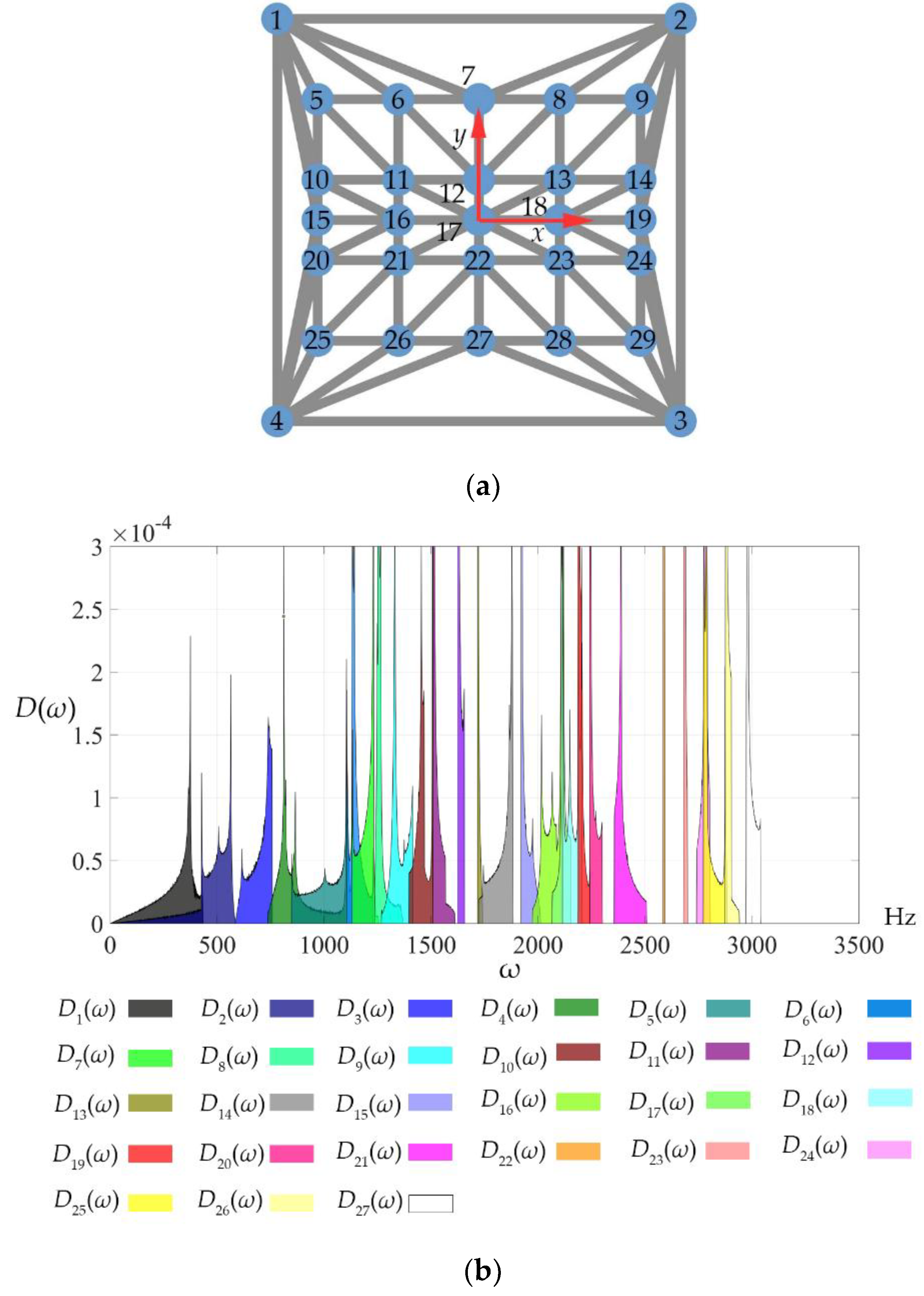

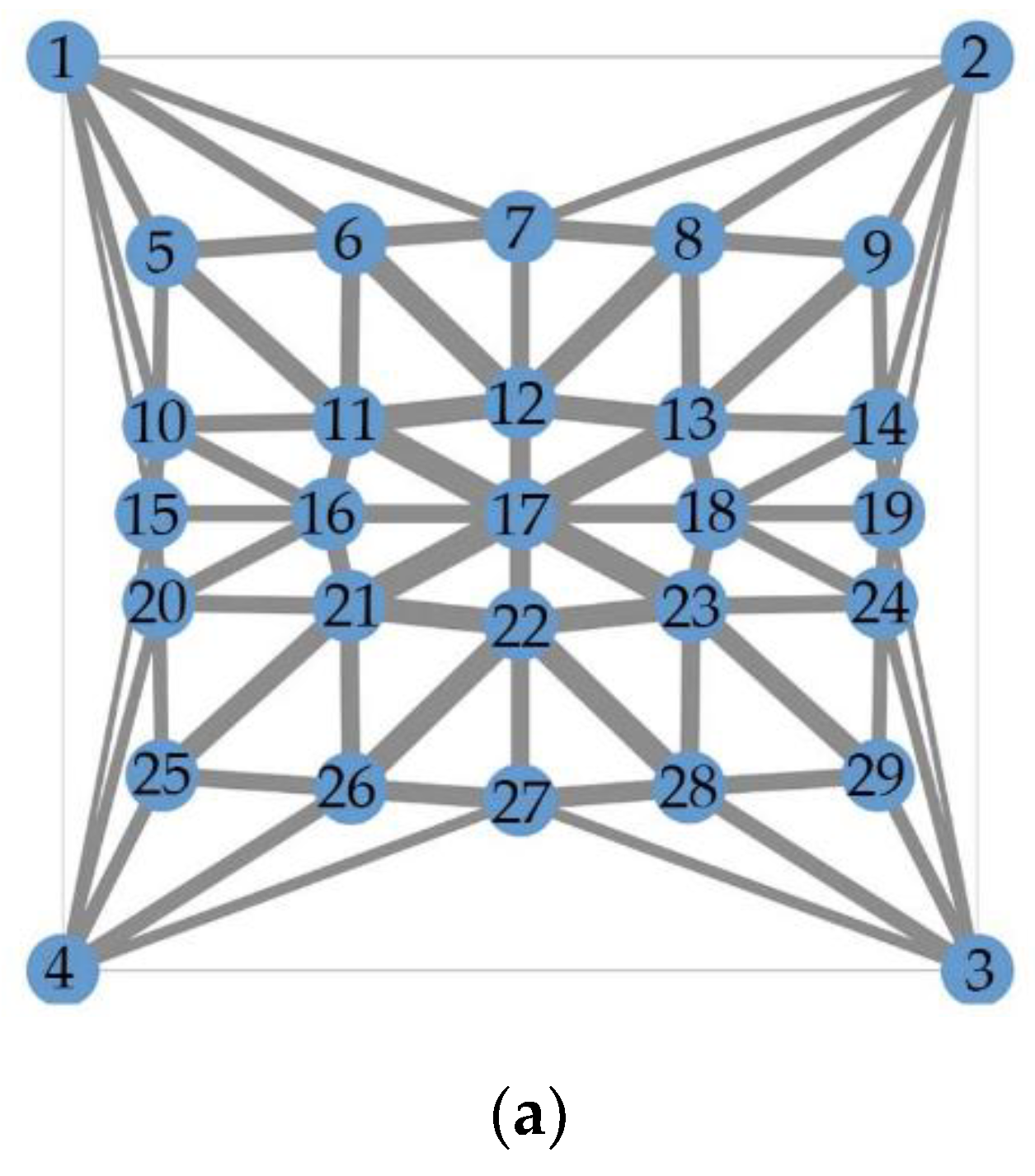

4. Example

Figure 7a shows a square unit cell with a side length of 10 mm that exhibits spatial inversion symmetry along the

x- and

y-axes. The origin of the coordinate system is at the center of the unit cell with the axes shown in

Figure 7a. The node coordinates are listed in

Table 3. All the elements of the unit cell have a circular cross-section with a radius of 0.3 mm (area

A=0.283 mm

2) and are made of plastic with a Young’s modulus of

E=1.2 GPa and a density of

ρ=0.9 g/cm

3.

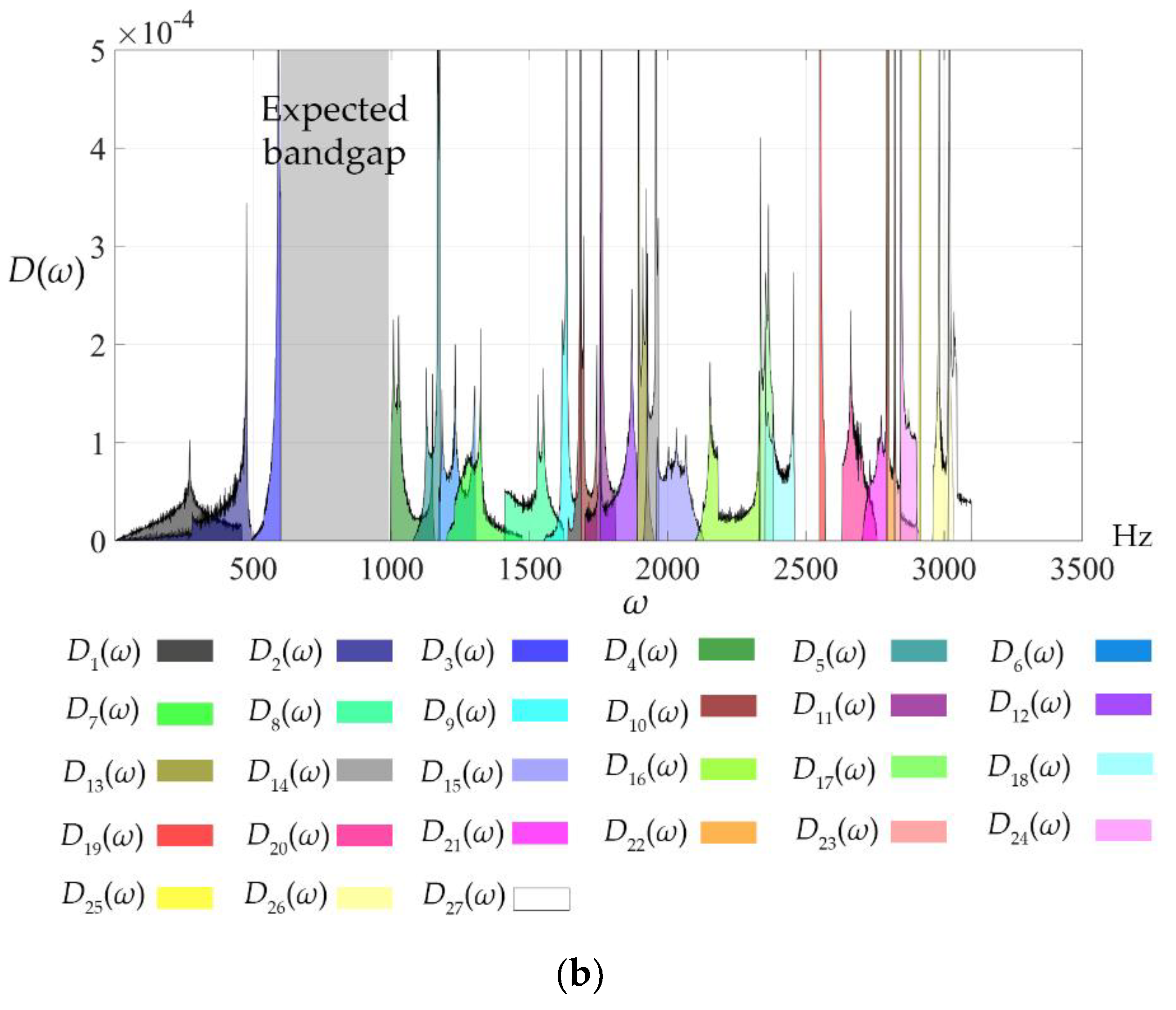

For this unit cell, the dispersion function obtained using Eq. (28) consists of 52 branches, whose significant overlap makes it difficult to depict their surfaces on a plane. To illustrate the band structure, a frequency distribution function for branch

j can be constructed as follows:

where

Π denotes the first Brillouin zone [

30]; d

A=d

kxd

ky is the area of the infinitesimal element of

Π; and

kx and

ky are the

x and

y components of

k, respectively. According to Eq. (36),

Dj(

ω) represents the total area of the infinitesimal elements for which

ωj=

ω. If

Dj(

ω)≠0, there must exist a wave vector

k such that

ωj(

k)=

ω. Therefore,

ωj(

k) lies within the frequency domain with nonzero

Dj(

ω). The frequency distribution of the dispersion function can be visualized by plotting

Dj(

ω) for all branches, with

ω as the horizontal axis and area as the vertical axis.

Figure 7b shows 27 lower-frequency branches distributed between 0 and 3100 Hz.

This example aims to achieve a bandgap of 600–1000 Hz by designing the coordinates of nodes 5–29 and the cross-sectional areas of all elements. According to

Figure 7b, the expected bandgap is most likely generated between branches 3 and 4. The unit cell parameters are iteratively adjusted using Eqs. (31)– (35) with a tolerance of

c=2. The resulting unit cell is shown in Fib. 8a, whose element cross-sectional areas and node coordinates are listed in

Table 4 and

Table 5, respectively. The frequency distribution of the updated dispersion function is shown in

Figure 8b, where a bandgap of 600.0–998.6 Hz can be found.

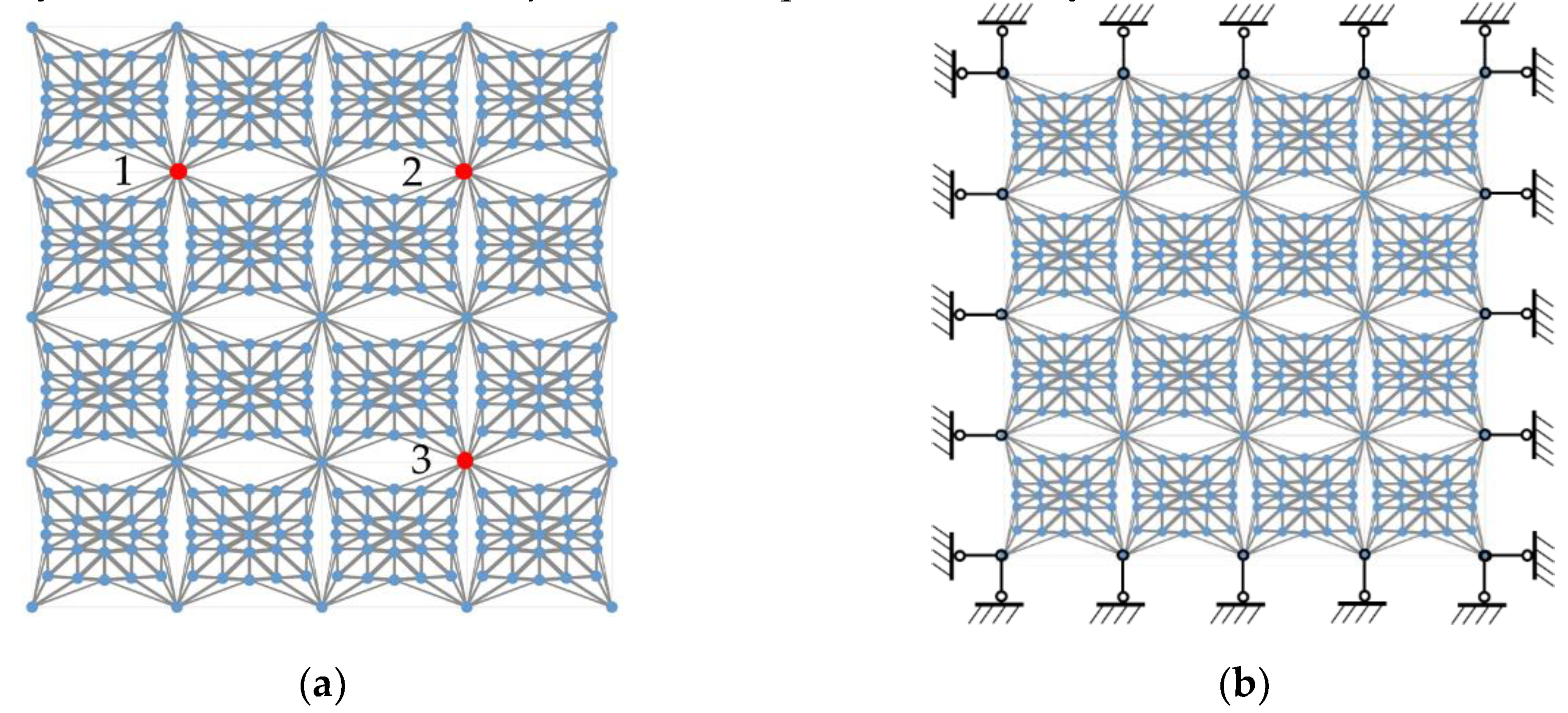

A metamaterial consisting of 4×4 designed unit cells is shown in

Figure 9a. The metamaterial is denoted as PBC, FBC or SBC when the periodic, free, or specific boundary condition is imposed. The specific boundary condition is illustrated in

Figure 9b and corresponds to case 3 in

Table 1. In addition, the symmetry of the designed unit cell can be slightly broken by adjusting the coordinate of node 15 to (-4.03, 1.00), resulting in a bandgap of 601.0–904.7 Hz. The 4×4 metamaterial, consisting of this asymmetric unit cell and subjected to the specific boundary condition, is denoted as SBCA.

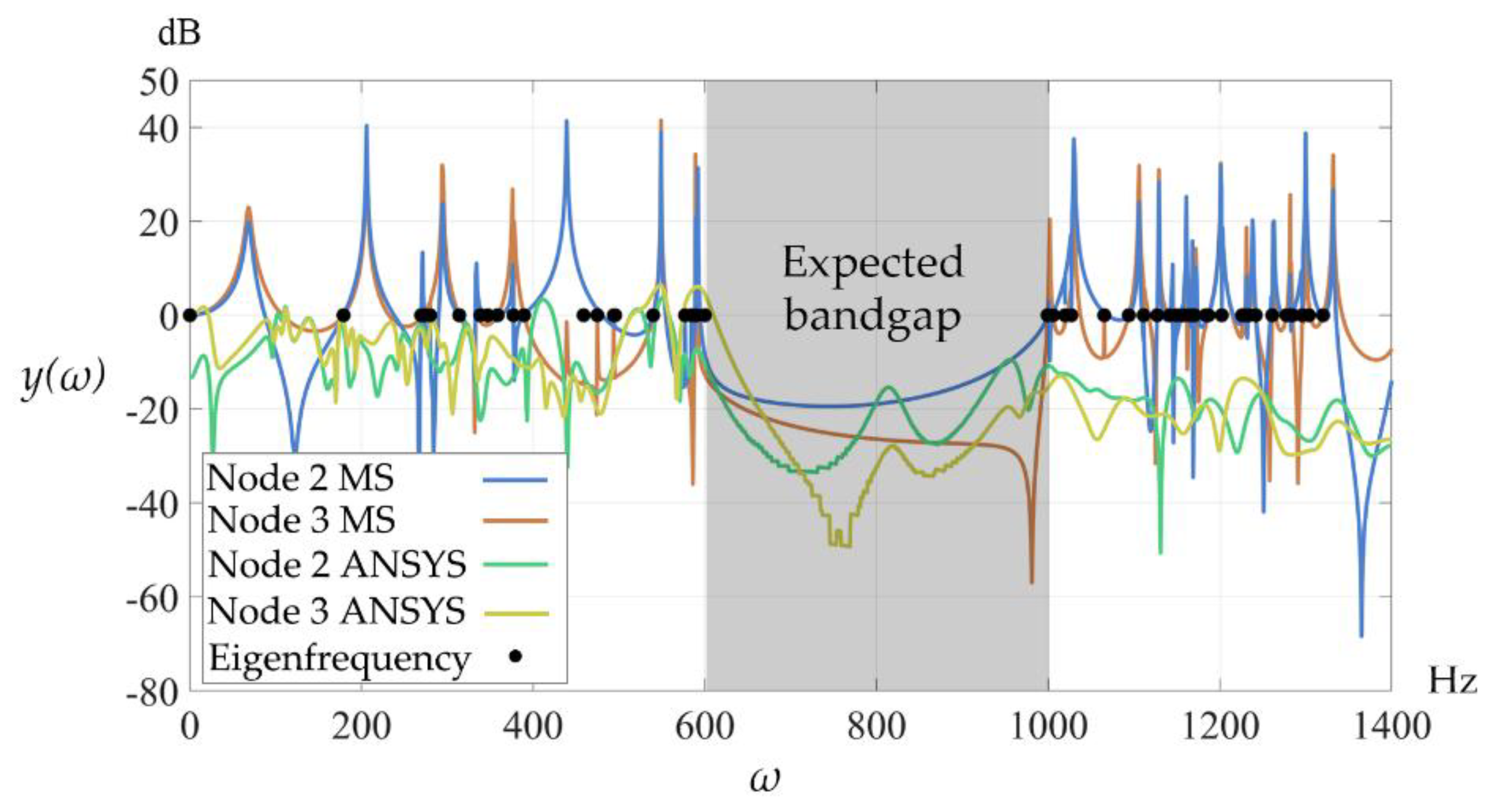

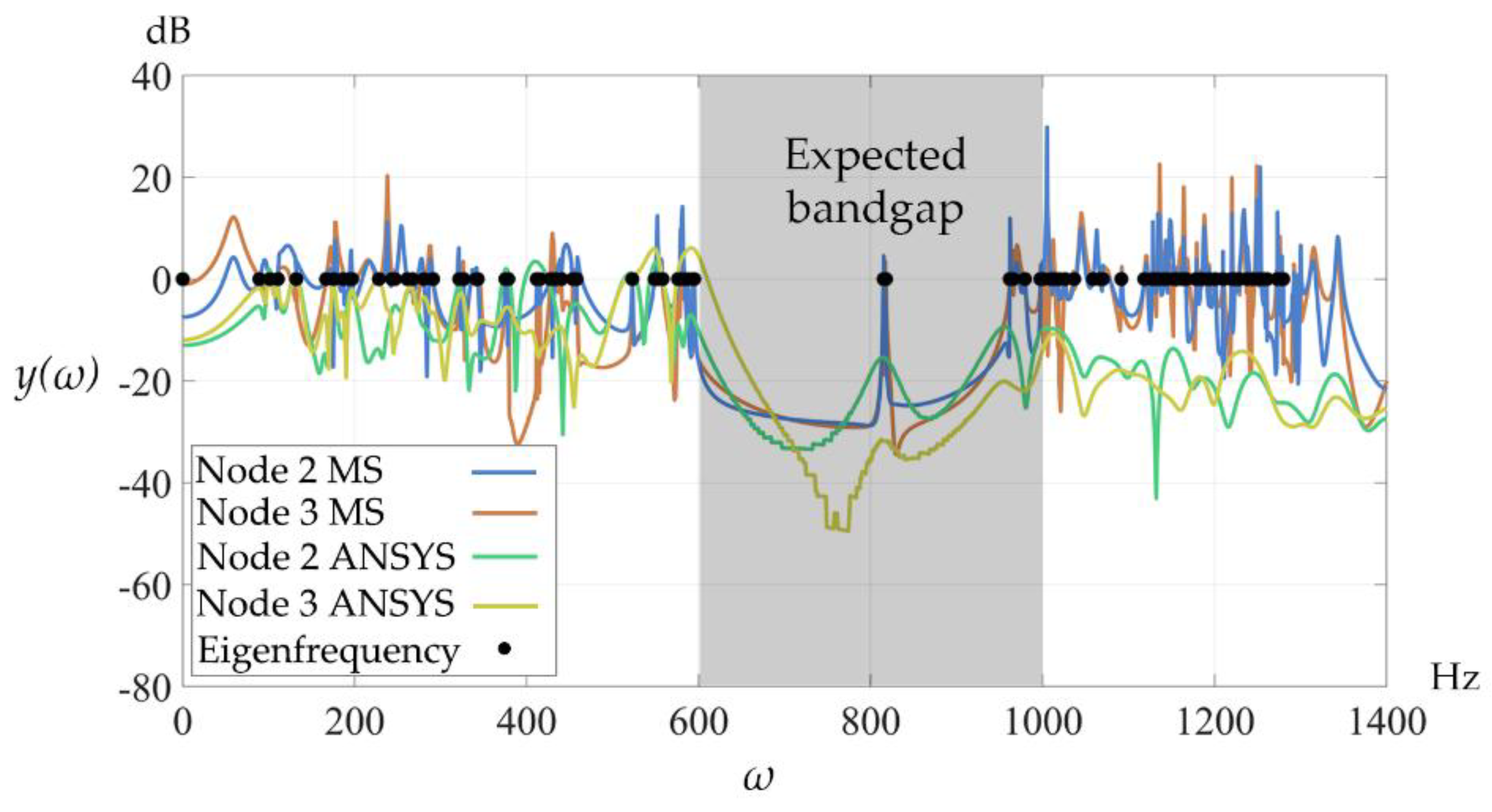

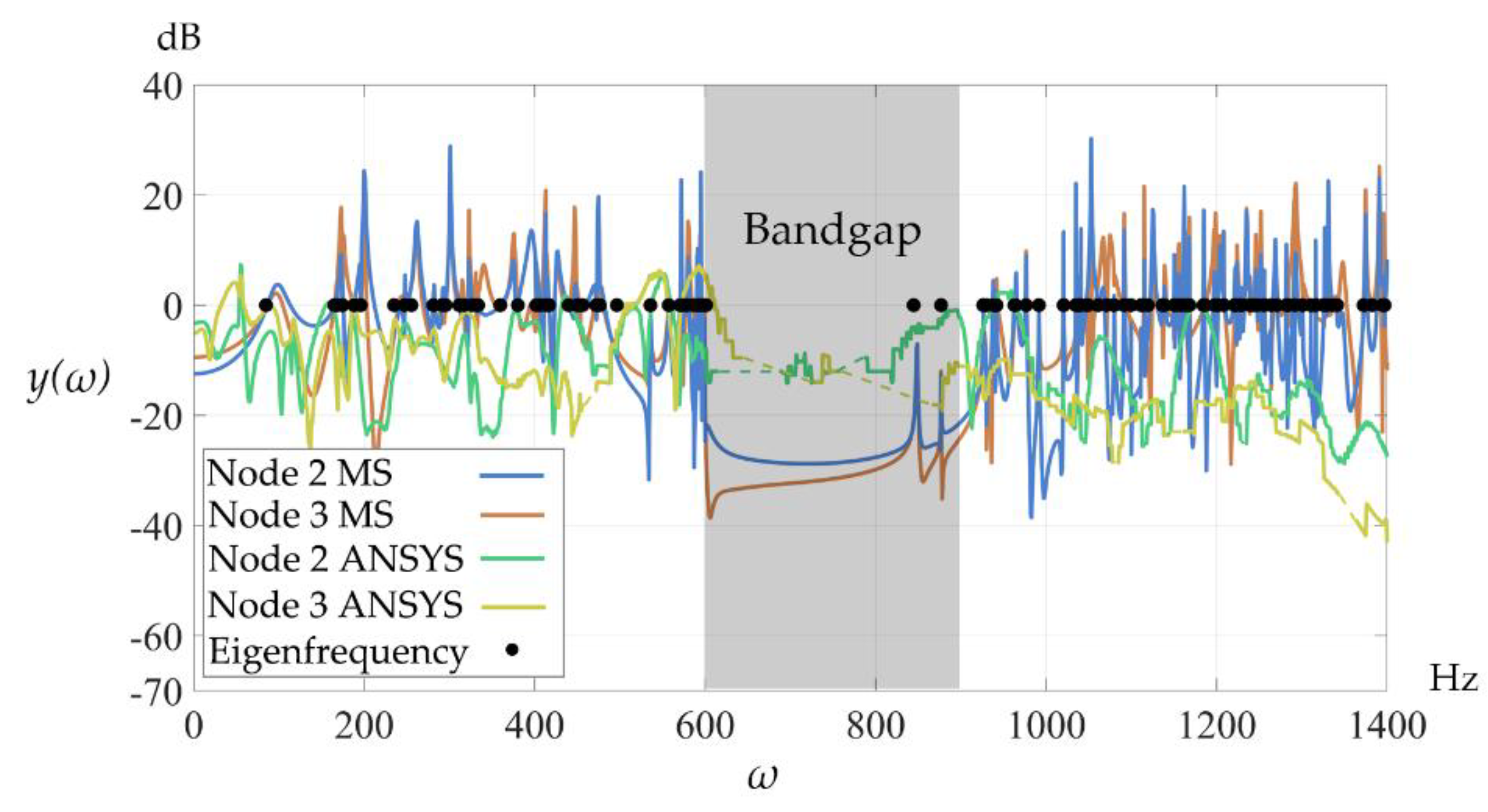

The eigenfrequencies and frequency-response curves of PBC, FBC, SBC, and SBCA are shown in

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13. The frequency-response function is defined as

where ||

din(

ω)|| is the displacement amplitude at input node 1, and ||

dout(

ω)|| is that at output node 2 or 3. These nodes are labeled in

Figure 9a. With a modal damping of 0.02, ||

din(

ω)|| and ||

dout(

ω)|| are calculated using the modal superposition method (MS) [

32] and the finite element software ANSYS, respectively. The MS is implemented in MATLAB, and the procedure includes the following steps: (1) Set up the dynamic equation for the metamaterial consisting of 4×4 unit cells. (2) Calculate the eigenfrequencies and eigenmodes of the metamaterial. (3) Calculate the displacements at the input and output nodes, i.e.,

din and

dout, under a simple harmonic load using the displacement equation [

32] of the modal superposition method. The metamaterials are also modelled in ANSYS. All the elements are simulated by Link180. A harmonic response analysis is conducted to obtain the displacements

din and

dout, with the solution method [

33] set to FULL.

As illustrated in

Figure 10, the eigenfrequencies and frequency-response curves of PBC are consistent with the bandgap, confirming that the metamaterial with expected bandgap has been successfully designed. However, when the metamaterial is subjected to the free boundary condition, eigenfrequencies emerge within the bandgap, as illustrated in

Figure 11.

Figure 12 shows that the bandgap resonances in SBC are effectively suppressed by imposing the specific boundary condition, thereby validating the second condition of Theorem 1. For the asymmetric metamaterial, even when the specific boundary condition is imposed, bandgap resonances still emerge in the frequency-response curves of

Figure 13. This validates the first condition of Theorem 1.