1. Introduction

The prevention of damage to human society caused by surface waves from earthquakes, traffic, construction, explosions, and other factors has always been a serious challenge. Since 2012, seismic metamaterials (SMs) have attracted great attention as an artificial material. In that year, Brülé and colleagues conducted large-scale experiments demonstrating that a two-dimensional periodic and symmetric array of vertical cylindrical holes in the ground could effectively shield seismic waves around 50 Hz [

1]. This groundbreaking work marked a milestone in the field of seismic resistance and protection. Subsequently, Miniaci and Roux confirmed similar results through numerical simulations and experiments, respectively [

2,

3]. However, due to the large structural dimensions of these SMs, which are based on the Bragg scattering mechanism, controlling low-frequency seismic waves proved challenging. Inspired by Liu et al.’s work on the generation of bandgaps in locally resonant phononic crystals [

4], Researchers have begun to focus on the development of locally resonant seismic metamaterials (RSMs) [

3,

5]. RSMs utilize small-sized resonator units to manage long-wavelength seismic vibrations. When the frequency of seismic waves resonates with that of the resonator units, the seismic wave energy is effectively dissipated [

6]. Typically, the resonant units in RSMs are arranged in periodic arrays, forming configurations known as Buried RSMs or Above-Surface RSMs. The periodic arrangement of these resonators leads to the formation of a bandgap, while their interaction with surface waves causes both self-oscillation and scattering of the surface waves. These factors thereby collectively suppress the propagation of the surface waves.

To date, various structures of RSMs have been developed for attenuating the surface waves. However, it is worth noting that most of the published literature primarily emphasizes the performance evaluation of RSMs in terms of Rayleigh wave attenuation [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38], while the impact of seismic metamaterials on Love waves has received comparatively less attention [

39,

40,

41,

42]. In fact, Love waves primarily cause horizontal shear motion, which can be particularly damaging to structures not designed to withstand lateral forces. They include cracking or collapse of walls due to excessive horizontal displacement and shear failure in columns and beams, especially in buildings with weak lateral reinforcement. They travel faster than Rayleigh waves and can carry considerable energy over long distances, causing substantial damage. Consequently, Love waves play a notable role in seismic events. Therefore, understanding the attenuation of Love waves by seismic metamaterials is crucial for advancing seismic protection strategies.

On the other hand, most of the SMs mentioned above are studied through simulations [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

39,

40,

41,

42] and laboratory experiments [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

35,

36,

37,

38], with very few being investigated through field experiments [

1,

7,

24,

25]. The advantage of simulation technology is that it can rapidly test SMs with a variety of complex geometric shapes and material properties, which facilitates the optimization of SMs for specific earthquake applications and significantly reduces the time and cost of SMs design. However, the accuracy of simulations largely depends on the assumptions made in the models. The complexity of the physical interactions between SMs and actual seismic environments makes it challenging for simulation results to accurately reflect real-world conditions. For instance, due to soil heterogeneity, “its theoretical and numerical analysis requires some simplified assumptions that can lead to inaccurate wave simulations. This means experimental validation is absolutely necessary” [

3]. Therefore, while simulation technology is a powerful tool for predicting the performance of SMs , field experimental validation is crucial to ensure its reliability and effectiveness.

In this study, we aim to harness a structurally simple SMs and conduct field experiments to observe and compare its attenuation effects on Rayleigh and Love waves. This includes examining bandgap width, energy variation, and frequency dependence. The research is motivated by the limited attention given to Love waves in existing studies. We first designed a SMs consisting of a periodic and symmetric array of holes based on elastic wave propagation theory and numerical simulation techniques as the subject of investigation. Five sensors were strategically and symmetrically positioned behind the metamaterials to measure vibration velocity signals in the x, y, and z directions. Their performance was assessed by comparing scenarios with and without SMs. The experimental results reveal that an ultra-wide bandgap exists for Rayleigh waves within the range of 40 Hz to 60 Hz, and for Love waves within 43 Hz to 56 Hz. Moreover, a wave attenuation reversal point occurs at 50 Hz: below this frequency, the attenuation of Love waves surpasses that of Rayleigh waves, whereas above 50 Hz, Rayleigh waves experience greater attenuation. These findings demonstrate that even a simple-structured hole-type SMs exhibits differing attenuation effects on Rayleigh and Love waves and underscore the importance of considering the attenuation capacity for Love waves when designing and evaluating seismic metamaterials for surface wave mitigation. Our work not only deepens the understanding of surface wave mechanics from an experimental perspective but also provides valuable insights for the design strategies and applications of metamaterials aimed at attenuating surface waves.

2. Theoretical

2.1. Elastic Wave Propagation Equation

Considering the propagation of elastic waves in the shallow subsurface, with displacements being small deformations, the elastic wave propagation equation based on the thin-plate model is used as follows [

1]

Where ω is the angular frequency, ρ is the soil density, u is the displacement field in vector form, h is the thickness of elastic plate, and D is the plate rigidity expressed by

where E is the Young’s modulus and ν is the Poisson’s ratio. The solution of an elastic wave propagating in a periodic potential field can be written as

Where

r is the space coordinate vector,

k is the Bloch wave vector, and

uk(

r) is a periodic function as follows

Where

a is the lattice vector. Accordingly, the Bloch periodic boundary conditions can be expressed as

Substituting equation (5) into equation (1), we can obtain the eigenvalue equation

where

D(

k) is the lattice stiffness matrix,

is the lattice mass matrix and

k is the Bloch wave vector. By calculating the wave vectors under different structures along the first Brillouin region M-Γ-X-M, the dispersion relationship between

k and

can be obtained.

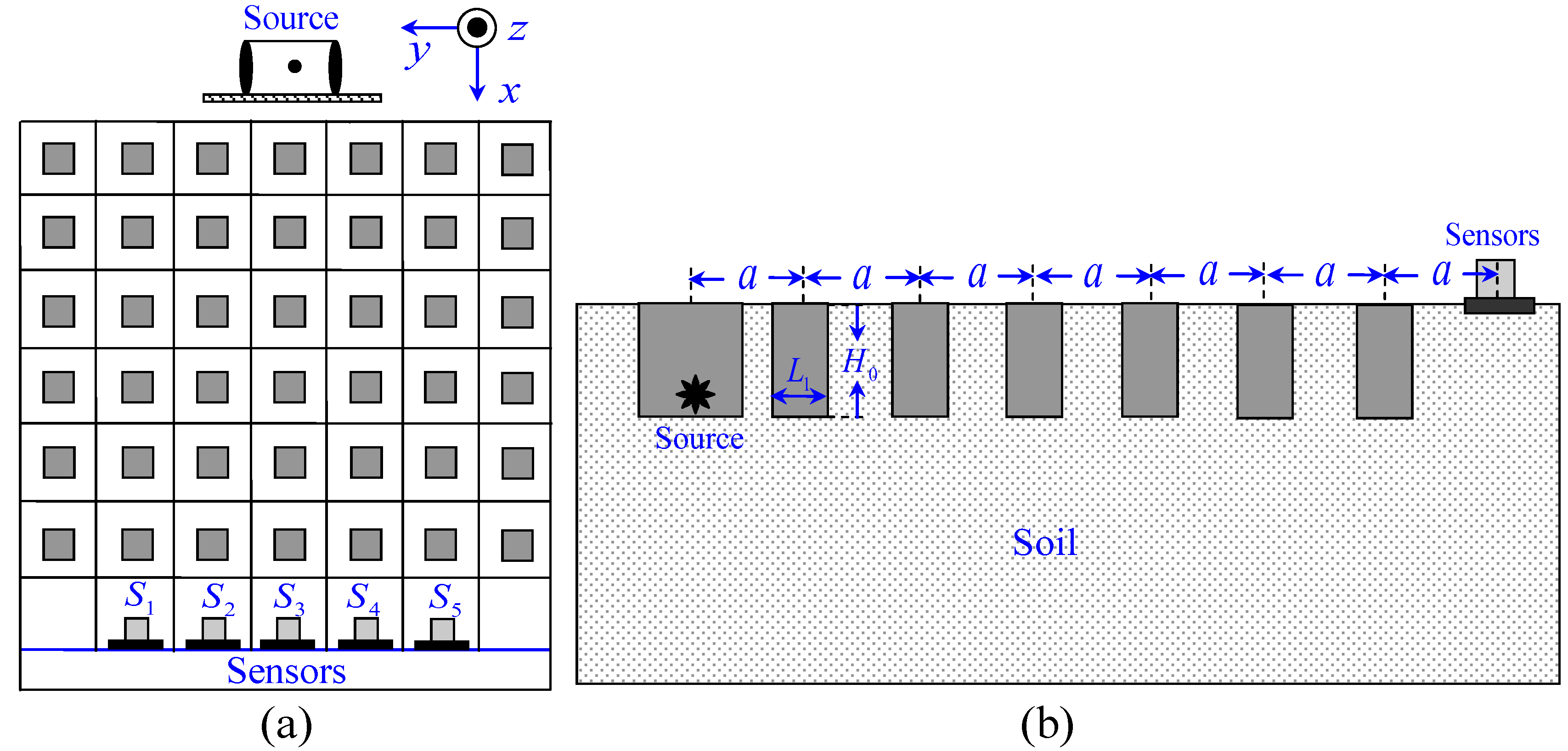

2.2. Numerical Simulation

The design of seismic metamaterials is typically based on periodic structures and symmetry. Periodic structures possess translational symmetry, which allows for effective control over the propagation of seismic waves. Here, the SMs structure designed by using COMSOL Multiphysics consists of a 6×7 periodic and symmetric square hole array, with a lattice constant of a = 1m. The cell of the structural unit is a square hole with a side length of L

1 = 0.27m and a depth of H

0 = 0.35m. The vibration source and five sets of sensors are symmetrically placed in the front and rear of the periodic structure, as shown in

Figure 1.

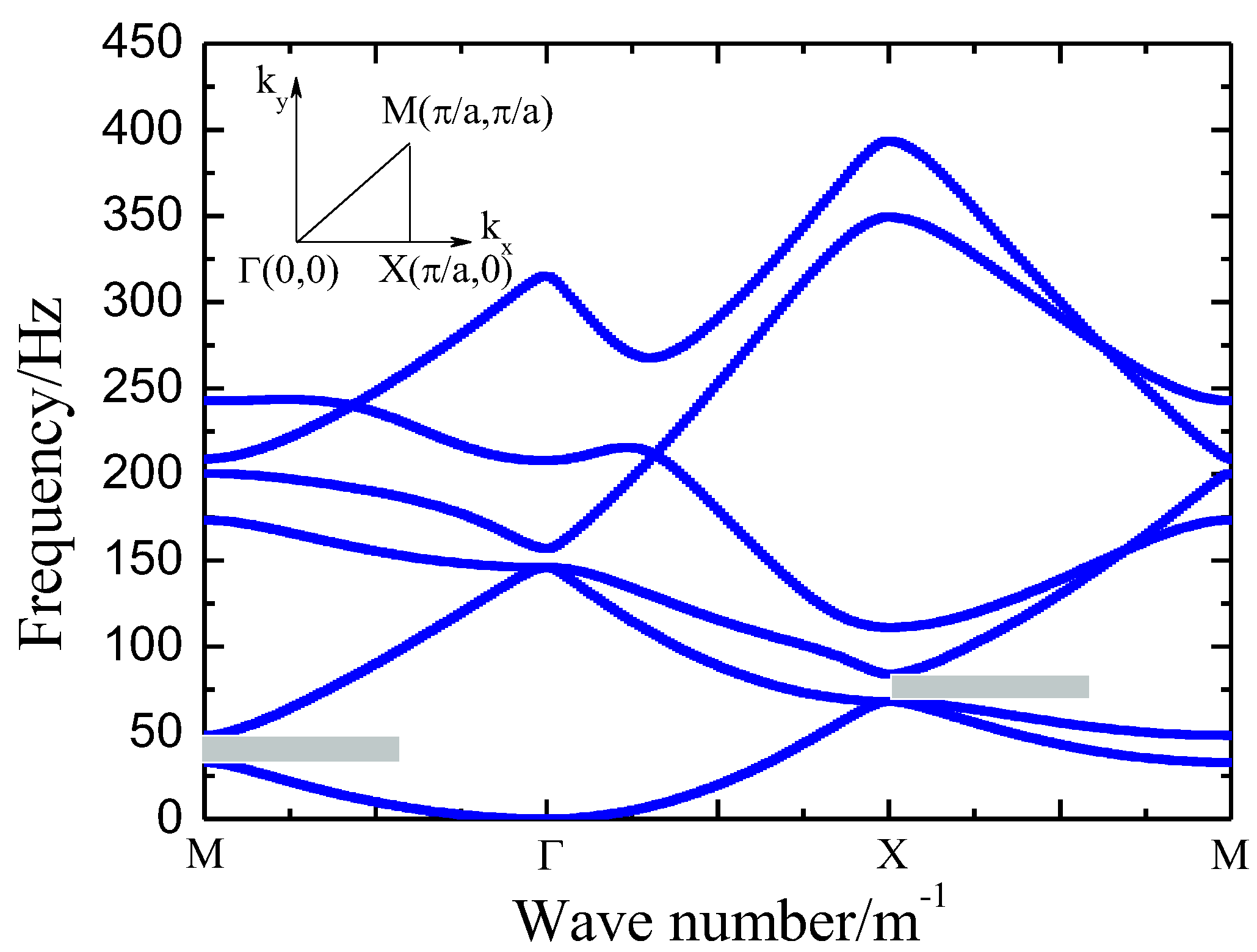

The band structure of SMs is shown in

Figure 2, where the simulation parameters used are density ρ = 1500 kg/m³, Young's modulus E = 100 MPa, and Poisson’s ratio ν = 0.3, respectively. It can be observed that there is a localized bandgap in the MΓ direction, ranging from 34 Hz to 50 Hz, and another localized bandgap in the XM direction, ranging from 70 Hz to 82 Hz.

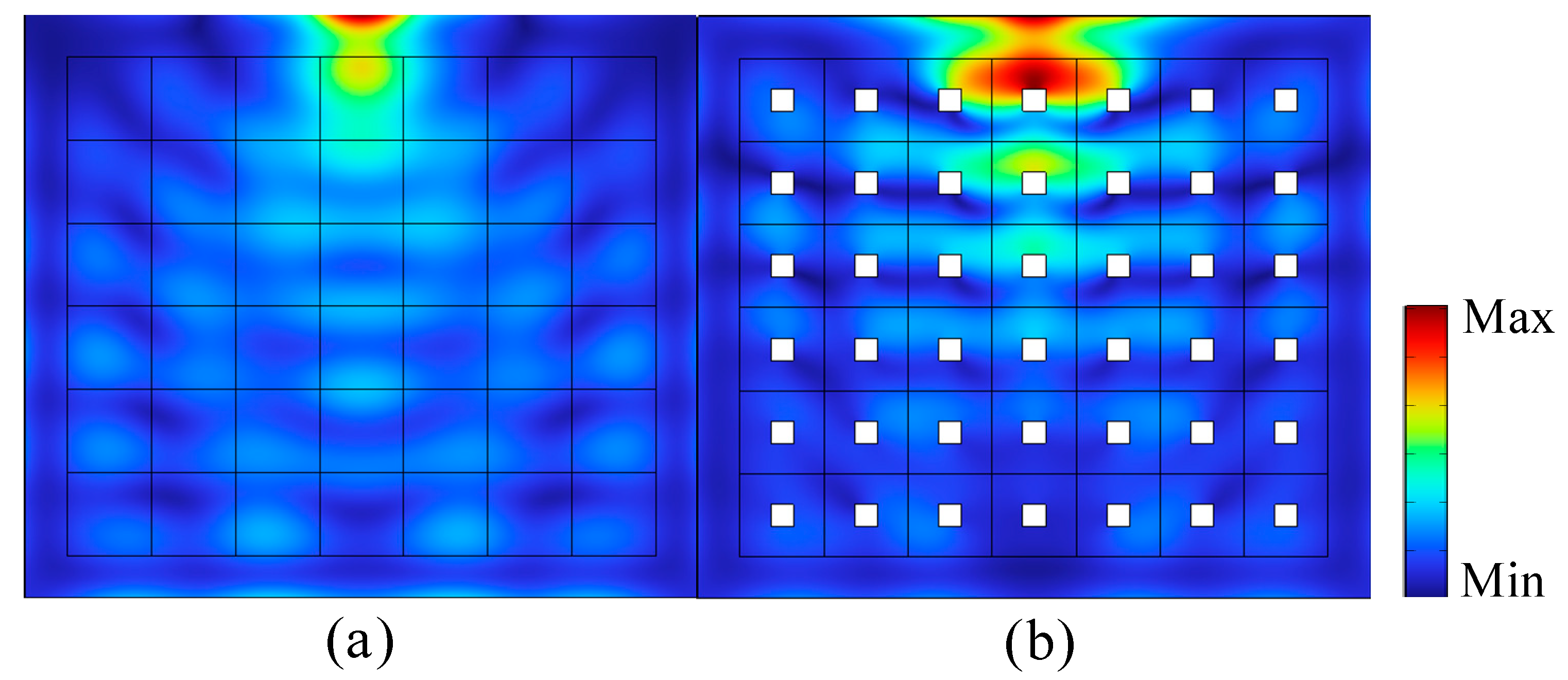

The displacement field distribution of surface wave propagation shown in

Figure 3 indicates that the designed SMs have a damping effect on the waves and can change the direction of wave propagation, leading to the formation of a bandgap. Actually, the bandgap of periodic structures is essentially a result of symmetry, characterized by time-reversal symmetry and spatial translational symmetry.

3. Experimental

3.1. Set Up

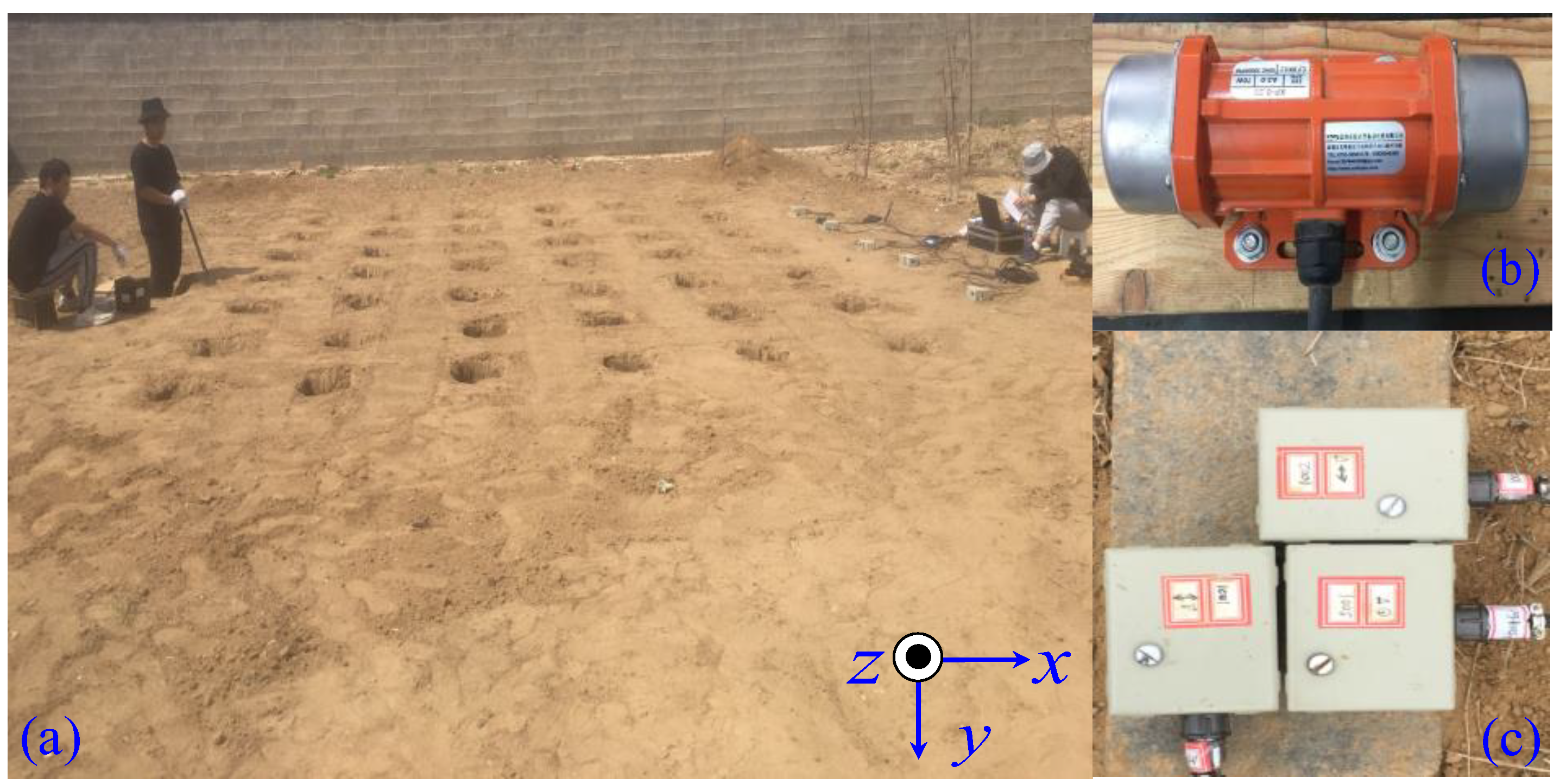

The experimental site, as shown in

Figure 4a, where the 6×7 periodic and symmetric square hole array was arranged based on the simulation, is located in the North Campus of the Institute of Disaster Prevention. From the perspective of the SMs structure, the square holes here are somewhat innovative, as they differ from the circular holes designed by previous researchers [

1,

24]. The soil type is stiff clay, with a relative humidity of 60%-70%. The Love wave velocity in the soil is 105 m/s. The vibration source is an eccentric wheel vibrator (XDP-80DC-24,

Figure 4b) powered by a 24V DC power supply, with a frequency adjustment range of 20 Hz to 70 Hz. A 24-bit data acquisition system was used to record the signals. During the experiment, the vibration source was placed 0.5 meters below the ground, and the set frequency ranged from 40 Hz to 60 Hz with an interval of 2 Hz. Five sets of sensors (velocity range: low-frequency cutoff at -3 dB, bandwidth of 0.5 Hz to 150 Hz) were symmetrically positioned on the ground at the rear end of the SMs structure, spaced 1 meter apart, labeled S

1 to S

5 (

Figure 1a). Compared to measuring wave attenuation only at the position directly facing the wave source [

7,

25], observing at five different locations provides insights into the attenuation information of SMs for waves propagating in different directions.

In addition, each set consists of three unidirectional sensors (

x,

y,

z) used to measure three signal components along the horizontal inline (

x-component), horizontal crossline (

y-component) and vertical directions (

z-component), as shown in

Figure 4a. In contrast to the existing literature which typically focuses only on the attenuation of the

z-direction vibration component [

7], measuring the attenuation of the

x,

y, and

z vibration components can provide a comprehensive understanding of how SMs impact wave propagation in all spatial directions.

3.2. Data Processing

First, start the data acquisition instrument and wait for 5-10 s, then start the vibrator. During the experiment, record data for 120 s and calculate the average energy per unit time from the data collected between 40 s and 80 s, i.e.

In which, represents the components of energy in x, y and z directions, E is the total energy, t2 and t1 are the upper and lower limits of time, vi represents the corresponding velocity components, and m means the mass of sensor.

During the experimental process, the background noise signal is measured first. Only when the energy of the received vibration source signal per unit time is at least five times greater than that of the background noise, and the fundamental frequency matches the signal frequency, can the signal be considered valid and recorded. To analyze the energy attenuation, we define the total energy of the structure without SMs as

and that of the structure with SMs as

, along with their respective components

and

(

i =

x,

y,

z), and the corresponding attenuation coefficients as

kH and

ki, respectively. We have,

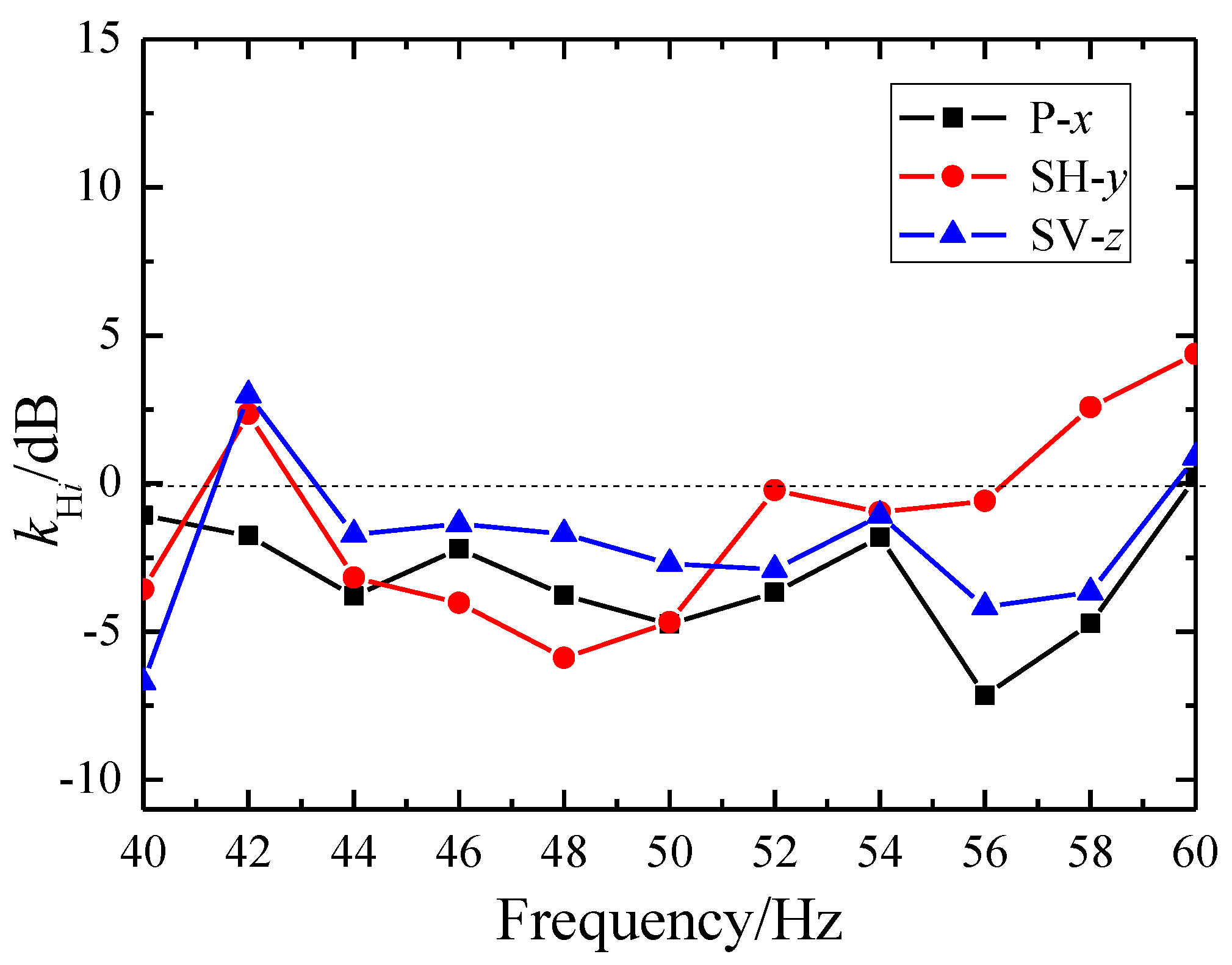

3.3. Energy Attenuation of Surface Waves

Figure 5 provides an example of the attenuation of three vibration components of surface waves at the position directly opposite (S

3). The black square dots represent the

x-component (P-wave), the red circular dots represent the

y-component (SH-wave), and the blue triangular dots represent the

z-component (SV-wave). It can be seen that the SMs generate ultra-wide bandgaps for all three components of the surface waves, with the narrowest ultra-wide bandgap from 43 Hz to 56 Hz. Additionally, the SMs exhibits a more pronounced attenuation effect on SH-waves and P-waves within the bandgap range, while the attenuation of SV-waves is relatively weaker. This may be attributed to the localized resonance mechanism of the hole structure. Obviouslly, observing the attenuation of various vibration components of surface waves helps in designing SMs that selectively attenuate specific vibration components.

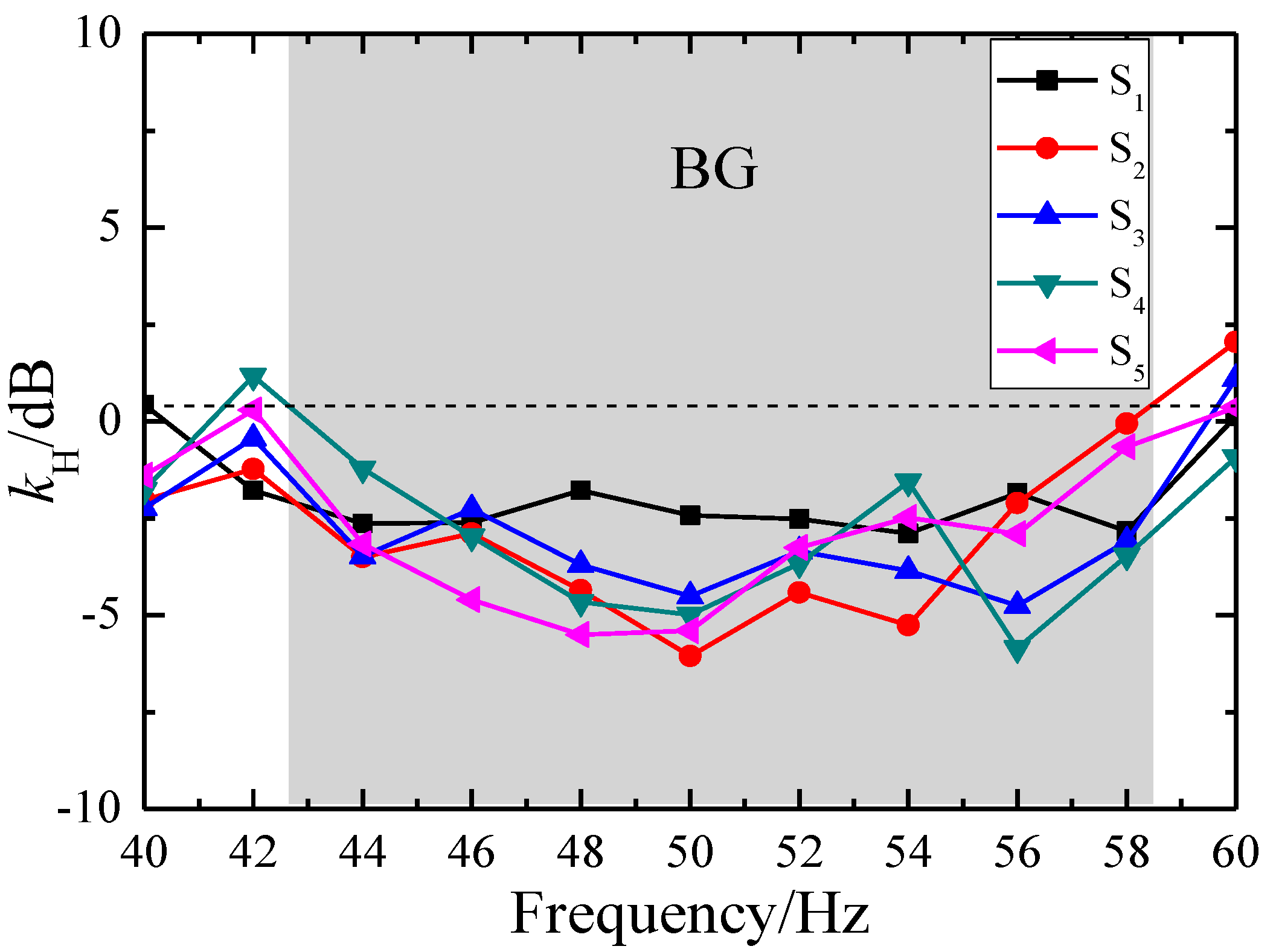

If we consider the vector sum of the energies of the

x,

y, and

z components of vibration as the total energy of the vibration, we can obtain the attenuation of the total energy of surface waves measured at different frequencies by five sensor sets (S

1 - S

5) located at different positions, as shown in

Figure 6. It is evident that there is a significant ultra-wide bandgap between 43 Hz and 58 Hz, indicating that the SMs structure can effectively attenuate surface waves within this frequency range.

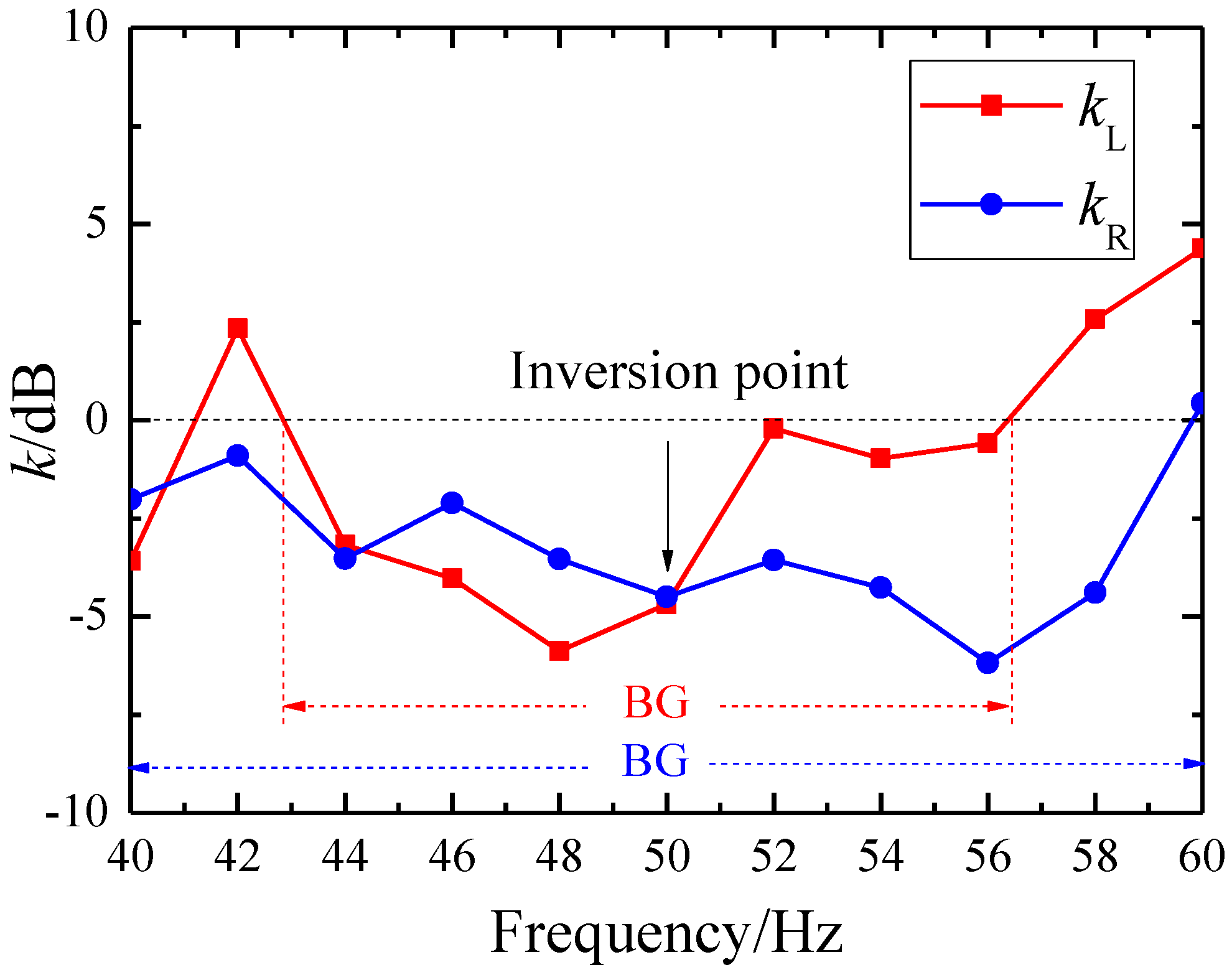

3.4. Attenuation of Rayleigh and Love Waves

Now, we use the recorded results from the S

3 sensor to further examine the attenuation effects of the RMs on Rayleigh and Love waves. Considering that both Rayleigh and Love waves result from the interaction between the incident waves and the RMS, Rayleigh waves are the superposition of horizontal inline waves (P-waves) and vertical waves (SV-waves) after passing through the SMs structure, they should be included in the sum of the measurement results in the

x and

z directions. In contrast, Love waves are the superposition of horizontal crossline waves (SH-waves) that undergo multiple reflections after encountering the SMs structure, and they should be included in the measurement results in the y direction. Therefore, we can define the attenuation coefficients of Rayleigh and Love waves as

kR and

kL, respectively. That is

Figure 7 illustrates the attenuation effects of surface waves at the position directly opposite (S

3). The red square dots represent the attenuation of Love waves, while the blue circular dots represent the attenuation of Rayleigh waves. From the figure, it can be observed that the bandgap for Rayleigh waves is approximately 40 Hz to 60 Hz, while the bandgap for Love waves is around 43 Hz to 56 Hz. Additionally, there is a point of reversal in wave attenuation at 50 Hz: below this frequency, the attenuation of Love waves exceeds that of Rayleigh waves, whereas above 50 Hz, Rayleigh waves experience greater attenuation. This may be because, below 50 Hz, the shear motion of Love waves within the horizontal plane interacts more strongly with the periodic holes of the structure, leading to increased scattering and energy loss. In contrast, above 50 Hz, the vertical component of high-frequency Rayleigh waves induces vibrations in the air within the holes, resulting in localized resonance, which enhances wave scattering and energy dissipation. This phenomenon also highlights the complex interactions between wave types, frequencies, and the SM structure, providing insights for the development of advanced strategies to manipulate seismic waves within specific frequency ranges to enhance attenuation.

4. Conclusions

The innovation of this work lies indemenstrating the necessity of incorporating Love wave attenuation into the design of metamaterials through field experimental validation, as this improvement could enhance their overall effectiveness in earthquake protection. A key finding of this study is the phenomenon of wave type inversion during attenuation. The square hole-shaped SMs we designed serve primarily as a platform for conducting field experiments to assess their responses to Rayleigh and Love waves. From the perspective of the SMs structure, the square holes we used are an innovation, as they differ from the circular holes designed by previous researchers.The experimental methods and data processing used in this research provide valuable reference samples for related studies. In contrast to numerical simulations, our field experiments closely mimic real-world scenarios, lending greater reliability to our conclusions. By measuring attenuation effects in the x, y, and z directions employing five sensors placed at different locations, we achieve a more comprehensive and accurate assessment of the seismic performance of the SMs, and enhancing our understanding of their overall control over complex wave fields.

In summary, our work highlights the importance of considering the attenuation of Love waves when designing seismic metamaterials, as well as the complexity of the interaction between the SMs and surface waves. The relationship between the attenuation wave types and their frequency dependence is a topic worthy of further investigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. and Q.S.; methodology, Q.S.; software, W.L.; validation, X.Z. and Q.S.; formal analysis, X.Z.; investigation, W.L.; resources, W.L.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z.; writing—review and editing, Q.S.; visualization, W.L.; supervision, Q.S.; project administration, W.L.; funding acquisition, Q.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 11974044.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the National Natural Science Foundation for their support (No: 11974044). We also thanks to Professor Yulin Lu from the School of Civil Engineering at the Institute of Disaster Prevention for his valuable discussions, as well as to Dr. Changyin Ji from the School of Physics at the Beijing Institute of Technology for his helpful assistance with the simulation program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- S. Brûlé, E. H. Javelaud, S. Enoch, S. Guenneau. Experiments on Seismic Metamaterials: Molding Surface Waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 113901.

- Marco Miniaci, Anastasiia Krushynska, Federico Bosia, Nicola M. Pugno. Large scale mechanical metamaterials as seismic shields. New J. Phys. 2016, 18, 083041. [CrossRef]

- Brûlé, S. Enoch, S. Guenneau, Emergence of seismic metamaterials: Current state and future perspectives. Physics Letters A. 2020, 384, 126034. [CrossRef]

- Zhengyou Liu, Xixiang Zhang, Yiwei Mao, Y. Y. Zhu, Zhiyu Yang, C. T. Chan, Ping Sheng. Locally Resonant Sonic Materials. Science 2000, 289, 1734.

- Di Mu, Haisheng Shu, Lei Zhao, Shuowei An. A Review of Research on Seismic Metamaterials. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2020, 22, 1901148. [CrossRef]

- Xinchao Zhang, Ning Zheng, Changyin Ji, Yulin Lu, Qingfan Shi. Attenuation of seismic waves using resonant metasurfaces: A field study on an array of rubber oscillators. Materials Today Communications 2024, 41, 110659. [CrossRef]

- Yi Zeng, Shu-Yan Zhang, Hong-Tao Zhou, Yan-Feng Wang, Liyun Cao, Yifan Zhu, Qiu-Jiao Du, Badreddine Assouar, Yue-Sheng Wang. Broadband inverted T-shaped seismic metamaterial. Materials & Design 2021, 208, 109906.

- Xingbo Pua, Antonio Palermoa, Zhibao Cheng, Zhifei Shi, Alessandro Marzani. Seismic metasurfaces on porous layered media: Surface resonators and fluid-solid interaction effects on the propagation of Rayleigh waves. International Journal of Engineering Science 2020, 154, 103347. [CrossRef]

- Farhad Zeighami, Leonardo Sandoval, Alberto Guadagnini, Vittorio Di Federico. Uncertainty quantification and global sensitivity analysis of seismic Metabarriers. Engineering Structures 2023, 277, 115415. [CrossRef]

- Andrea Colombi1, Richard V. Craster1, Daniel Colquitt, Younes Achaoui, Sebastien Guenneau, Philippe Roux and Matthieu Rupin. Elastic Wave Control Beyond Band Gaps: Shaping the Flow of Waves in Plates and Half-Spaces with Subwavelength Resonant Rods. Frontiers in Mechanical Engineering 2017, 3, 1.

- Jia Lou, Xiang Fang, Jianke Du, Huaping Wu. Propagation of fundamental and third harmonics along a nonlinear seismic metasurface. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2022, 221, 107189. [CrossRef]

- AndreaColombi, Daniel Colquitt, Philippe Roux, SebastienGuenneau, RichardV. Craster. A seismic metamaterial: The resonant metawedge. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 27717.

- D. J. Colquitta, A. Colombib, R.V. Crasterb, P. Rouxc, S.R.L. Guenneau. Seismic metasurfaces: Sub-wavelength resonators and Rayleigh wave interaction. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2017, 99, 379. [CrossRef]

- Yi Zeng, Yang Xu, Hongwu Yang, Muhammad Muzamil, Rui Xu, Keke Deng, Pai Peng, Qiujiao Du. A Matryoshka-like seismic metamaterial with wide band-gap Characteristics. International Journal of Solids and Structures 2020, 185–186, 334.

- Chao Zeng, Chunfeng Zhao, Farhad Zeighami. Seismic surface wave attenuation by resonant metasurfaces on stratified soil. Earthquake Engng Struct Dyn. 2022, 51, 1201. [CrossRef]

- Jia Lou, Xiang Fang, Hui Fan, Jianke Du. A nonlinear seismic metamaterial lying on layered soils. Engineering Structures 2022, 272, 115032. [CrossRef]

- Xiang Fang, Jia Lou, Yu Mei Chen, Ji Wang, Ming Xu, Kuo-Chih Chuang. Broadband Rayleigh wave attenuation utilizing an inertant seismic metamaterial. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2023, 247, 108182. [CrossRef]

- Runcheng Cai, Yabin Jin, Timon Rabczuk, Xiaoying Zhuang, Bahram Djafari-Rouhani. Propagation and attenuation of Rayleigh and pseudo surface waves in viscoelastic metamaterials. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 129, 124903. [CrossRef]

- Antonio Palermo, Sebastian Krödel, Alessandro Marzani, Chiara Daraio. Engineered metabarrier as shield from seismic surface waves. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39356.

- R. Zaccherini, A. R. Zaccherini, A. Palermo, A. Marzani, A. Colombi, V. Dertimanis, and E. Chatzi. Mitigation of Rayleigh-like waves in granular media via multi-layer resonant metabarriers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 117, 254103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachele Zaccherini, Andrea Colombi, Antonio Palermo, Vasilis K. Dertimanis, Alessandro Marzani, Henrik R. Thomsen, Bozidar Stojadinovic, Eleni N. Chatzi. Locally Resonant Metasurfaces for Shear Waves in Granular Media. Physical Review Applied 2020, 13, 034055.

- Antonio Palermo, Sebastian Krödel, Kathryn H. Matlack, Rachele Zaccherini, Vasilis K. Dertimanis, Eleni N. Chatzi, Alessandro Marzani, Chiara Daraio. Hybridization of Guided Surface Acoustic Modes in Unconsolidated Granular Media by a Resonant Metasurface. Physical Review Applied 2018, 9, 054026. [CrossRef]

- Meng Ma, Bolong Jiang, Jian Gao, Weining Liu. Experimental study on attenuation zone of soil-periodic piles system. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 2019, 126, 105738. [CrossRef]

- Selcuk Kacin, Murat Ozturk, Umur Korkut Sevim, Bayram Ali Mert, Zafer Ozer, Oguzhan Akgol, Emin Unal, Muharrem Karaaslan. Seismic metamaterials for low-frequency mechanical wave Attenuation. Natural Hazards 2021, 107, 213.

- Chenzhi Cai, Lei Gao, Xuhui He, Yunfeng Zou, Kehui Yu, Dizi Wu. The surface wave attenuation zone of periodic composite in-filled trenches and its isolation performance in train-induced ground vibration isolation. Computers and Geotechnics 2021, 139, 104421. [CrossRef]

- Y. Achaoui, T. Antonakakis, S. Brûlé, R. V. Craster, S. Enoch, S. Guenneau. Clamped seismic metamaterials: Ultra-low frequency stop bands. New J. Phys. 2017, 19, 063022. [CrossRef]

- Xingbo Pu, Zhifei Shi. A novel method for identifying surface waves in periodic structures. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 2017, 98, 67. [CrossRef]

- Antonio Palermo, Matteo Vitali, Alessandro Marzani. Metabarriers with multi-mass locally resonating units for broad band Rayleigh waves attenuation. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 2018, 113, 265. [CrossRef]

- Younes Achaoui, Bogdan Ungureanua, Stefan Enocha, Stéphane Brûlé, Sébastien Guenneaua. Seismic waves damping with arrays of inertial resonators. Extreme Mechanics Letters 2016, 8, 30. [CrossRef]

- Xiao Wang, Shui Wan, Yuze Nian, Peng Zhou, Yingbo Zhu. Periodic in-filled pipes embedded in semi-infinite space as seismic metamaterials for filtering ultra-low-frequency surface waves. Construction and Building Materials 2021, 313, 125498. [CrossRef]

- Chunfeng Zhao, Chao Zeng, Yinzhi Wang, Wen Bai, Junwu Dai. Theoretical and Numerical Study on the Pile Barrier in Attenuating Seismic Surface Waves. Buildings 2022, 12, 1488. [CrossRef]

- Hua-Yang Chen, Zhen-Hui Qin, Sheng-Nan Liang, Xin Li, Si-Yuan Yu, Yan-Feng Chen. Gradient-index surface acoustic metamaterial for steering omnidirectional ultra-broadband seismic waves. Extreme Mechanics Letters 2023, 58, 101949. [CrossRef]

- Ting Li, Qian Su, Sakdirat Kaewunruen. Seismic metamaterial barriers for ground vibration mitigation in railways considering the train-track-soil dynamic interactions. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 260, 119936. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, C.W. Lim, Krzysztof Kamil Zur. Wide Rayleigh waves bandgap engineered metabarriers for ground born vibration attenuation. Engineering Structures 2021, 246, 113019. [CrossRef]

- Yi Zeng, Pai Peng, Qiu-Jiao Du, Yue-Sheng Wang, Badreddine Assouar. Subwavelength seismic metamaterial with an ultra-low frequency bandgap. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 128, 014901. [CrossRef]

- Yi Zeng, Yang Xu, Keke Deng, Pai Peng, Hongwu Yang, Muhammad Muzamil, Qiujiao Du. A broadband seismic metamaterial plate with simple structure and easy realization. J. Appl. Phys. 2019, 125, 224901. [CrossRef]

- Harshkumar Kamleshbhai Maheshwari, Prabhu Rajagopal. Novel locally resonant and widely scalable seismic metamaterials for broadband mitigation of disturbances in the very low frequency range of 0–33 Hz. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 2022, 161, 107409. [CrossRef]

- Weijia Yu, Linyun Zhou. Seismic metamaterial surface for broadband Rayleigh waves attenuation. Materials & Design 2023, 225, 111509.

- Xingbo Pu, Antonio Palermo, Alessandro Marzani. Lamb’s problem for a half-space coupled to a generic distribution of oscillators at the surface. International Journal of Engineering Science 2021, 168, 103547. [CrossRef]

- Qiujiao Du, Yi Zeng, Guoliang Huang, Hongwu Yang. Elastic metamaterial-based seismic shield for both Lamb and surface waves. AIP ADVANCES 2017, 7, 075015. [CrossRef]

- Dian-Kai Guo, Tungyang Chen. Seismic metamaterials for energy attenuation of shear horizontal waves in transversely isotropic media. Materials Today Communications 2021, 28, 102526. [CrossRef]

- Kai Zhang, Jie Luo, Fang Hong, Zichen Deng. Seismic metamaterials with cross-like and square steel sections for low-frequency wide band gaps. Engineering Structures 2021, 232, 111870.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).