1. Introduction

Nanotechnology is the engineering and science of designing, characterizing, synthesizing, and using materials and technologies at the nanoscale (1–100 nm) for diagnostics, treatments, and biomedical research tools [

1]. Materials frequently show unique properties at the nanoscale, including chemical, physical, and biological properties that are significantly changed from their bulk counterparts, allowing novel applications in different industries. In the medical sector, nanotechnology improves regenerative therapies, targeted drug delivery, and diagnostics because of its adjustable size, multifunctional properties, and high surface area [

2]. Medications may now be administered at a molecular level using these techniques; thus, addressing the disease and improving the investigation of its etiology. Indeed, nanoparticles with precisely regulated chemistry, dimensions, surface charge, and adjustable functionalization with targeted ligands can deliver medications to previously deemed inaccessible locations and impart novel characteristics. As a result, nanoengineered drug carriers can selectively target cells and tissues or protect the medications from host defense mechanisms until they arrive at their intended location [

3].

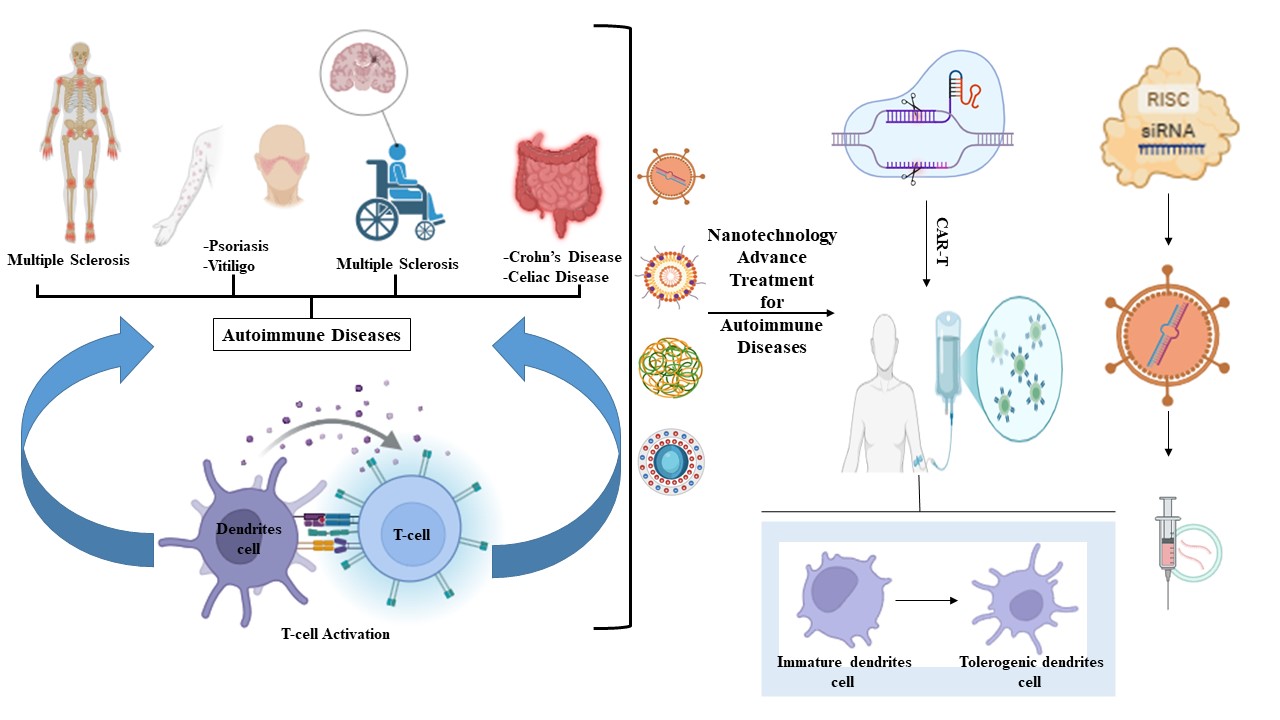

The disruption in the mechanism of particular antigen recognition and eradication can be classified as autoimmunity. This is primarily due to chemical, environmental, or biological influences, causing cells to undergo antigenic alteration, which may activate various immune responses [

4,

5]. Autoimmune diseases are chronic diseases defined by an abnormal immune response represented by failure to distinguish self from non-self, which results in tissue destruction and inflammation. The imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines seems to contribute to the onset of autoimmunity [

6]. Common examples include type 1 diabetes (T1D), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), multiple sclerosis (MS), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and psoriasis [

7,

8]. Traditional therapies often rely on broad immunosuppression, which frequently relieves symptoms but has serious adverse effects, such as elevated risk of infection, systemic toxicity, and poor long-term efficacy [

9]. In recent years, there has been a notable shift toward interventions designed to target the specific immune pathways and cell types responsible for disease activity, rather than applying blanket suppression, which is known as precision therapies [

10].

This review aims to explore the application of nanotechnology-based therapies in managing autoimmune diseases, highlighting recent advances, underlying mechanisms, therapeutic potential, and existing challenges in translating these strategies into clinical practice.

2. Mechanisms of Nanotechnology in Autoimmune Disease Treatment

Autoimmune disorders are persistent, deleterious conditions that may result in functional impairment and multi-organ failure. Notwithstanding, significant improvements in therapeutic agents, particularly biologicals, constraints related to administration routes, the necessity for regular long-term doses, and insufficient targeting alternatives frequently result in unsatisfactory efficacy, systemic negative outcomes, and patient non-compliance [

5]. Nanotechnology presents interesting approaches to enhance and refine the treatment of autoimmune diseases by addressing the challenges associated with existing immunosuppressive and biological therapies [

11]. This section concentrates on the nanomedicine mechanism for biological immunomodulatory drugs in the treatment of autoimmune diseases.

Many medications are utilized in the treatment of autoimmune conditions, including corticosteroids such as prednisone [

12]; immunosuppressants including methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil [

13]. Additionally, biologic drugs including infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, and rituximab; disease-modifying agents include sulfasalazine and leflunomide. Furthermore, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapies include ibuprofen and naproxen; and lastly the targeted biologic medicines include tocilizumab and abatacept [

14,

15]. These medications are delivered by multiple routes that necessitate elevated systemic concentrations to attain bioavailability and hit the affected organs, although they also produce adverse effects that influence healthy organs and tissues. Therefore, the formation of nanoparticles loaded with these medications was followed to increase their specificity, bioavailability, and effectiveness. They can be designed for targeting specific cells and tissues, transporting therapeutic agents such as immunosuppressants or antigens, and even scavenging extracellular nucleic acids associated with certain autoimmune disorders [

16,

17].

2.1. The Fundamental Role of the Immune System

The immune system’s reaction is essential for maintaining equilibrium, which is critical for safeguarding the body from foreign bodies and threats. However, an aberrant immune reaction, encompassing both immunosuppression and immune hyperactivity, will ultimately result in disease [

18]. Recent investigations indicate that both inflammatory responses (immune activation) and immunological tolerance (lack of responsiveness to self-antigens or certain foreign antigens) are affected by the manner of antigen presentation [

18,

19]. An immune-stimulating mechanism may cause an intense negative reaction, as observed in autoimmune disorders. These are collection of disorders that arise when the body’s tissues are attacked by its immune system [

20]. Conversely, allergic disorders include a range of disorders resulting from the immune system’s hypersensitivity to usually harmless environmental chemicals. Immunosuppressants are among the most frequently utilized medications for the treatment of autoimmune disorders and allergies. These medications diminish or obstruct the self-reactivity of the immune response, although they possess several adverse effects [

21].

2.2. Nanoparticles Loaded with Autoimmune Drugs for Targeted Delivery

The initially developed generation of nanoparticle-based medicines for treating autoimmunity focused on utilizing nanoparticles as vehicles for delivering immunosuppressive medications to areas of autoimmune inflammation [

22]. This antigen-non-specific method aims to mitigate effector immune reactions that result in tissue or organ injury following antigen identification by autoreactive T and B cells. These chemicals aim to enhance the concentration of the active pharmaceutical ingredient at particular targeting sites or to deliver hydrophobic therapeutic molecules, thereby minimizing off-target toxicity and boosting therapeutic efficacy [

23], as shown in

Table 1. The chemical and physical characteristics of these nanoparticle transporters, including structural components, morphology, dimensions, and the surface chemistry/coating, can be adjusted to enhance the pharmacokinetic characteristics and pharmacodynamic profiles of the compounds, such as distribution accessibility, transparency to and accumulation at target locations, and specific drug dissolution rates, among other factors [

24,

25].

Table 1.

NPs loaded with immunosuppressants for the treatment of different autoimmune diseases.

Table 1.

NPs loaded with immunosuppressants for the treatment of different autoimmune diseases.

| Type of nano-formulation |

Targeted disease |

Treatment type |

Model |

Results |

References |

Methotrexate caffeic acid-based polyphenol polymer nanoparticles

(MTX@PCOH NPs) |

RA |

Metothrexate |

Collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) mice |

MTX@PCOH nanoparticles significantly reduced the required medication dosage and alleviated harmful side effects in RA therapy |

[26] |

| MTX-loaded NPs |

RA |

Methotrexate |

CIA mice |

MTX-NPs reduced arthritis severity and joint damage in CIA mice compared to those treated with free MTX. The concentrations of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α, and vascular endothelial growth factor, were decreased in mice treated with MTX-NPs |

[27] |

| Methotrexate and minocycline- loaded PLGA nanoparticles (MMNPs) |

RA |

Methotrexate and minocycline |

- -

RAW 264.7 - -

Freund’s adjuvant (CFA)-induced arthritic Wistar albino rat |

The in vivo anti-arthritis study demonstrated the efficacy of the produced MMNPs in reducing arthritis following intravenous treatment. This proof of concept suggests that MTX paired with MNC nanoparticles may be useful in treating RA associated with serious infections

|

[28] |

| Tacrolimus-loaded lecithin-chitosan hybrid nanoparticles |

Psoriasis |

Tacrolimus |

IMQ-mouse |

This study demonstrated that manufactured nanoparticles had greater anti-psoriatic activity than the commercial product in ocular observation and postmortem skin sample histology. In vivo drug deposition achieved better nanoparticle skin deposition than the commercial product

|

[29] |

| Triamcinolone acetonide-loaded methoxypoly(ethyleneglycol)-poly(dl-lactide-co-glycolic acid) (TA-mPEG-PLGA) nanoparticles |

Uveitis

|

Triamcinolone acetonide |

Female Lewis rats |

TA-loaded mPEG-PLGA nanoparticles have improved anti-inflammatory treatment for chronic and recurrent uveitis in clinical practice

|

[30] |

Cyclosporine A loaded in poly-(lactic-co-glycolic-Acid) (PLGA)

(CYA-NPs)

|

IBS |

Cyclosporine A |

Balb/c mice |

CYA-loaded PLGA NPs, have been targeted inflamed mucosal regions and facilitated localized controlled release at the disease site, exhibited enhanced efficacy and safety in a pertinent preclinical mouse model in vivo

|

[31] |

Mycophenolic acid conjugated to dextran loaded into polysaccharide mycophenolate nanoparticles

(MPA@Dex-MPA NPs) |

Psoriasis |

Mycophenolic acid |

Balb/c mice |

MPA@Dex-MPA NPs were predominantly localized in dendritic cells (DCs) and markedly inhibited the hyperactivated DCs both in vivo and in vitro. Consequently, this study suggested that MPA@Dex-MPA nanoparticles are highly promising for the treatment of induced psoriasis-like skin inflammatin

|

[32] |

| Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) loaded on megalin-conjugated mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN-NPs) |

Lupus nephritis on

SLE |

Mycophenolate mofetil |

Murine autoimmune disease mice (MRL-lpr) |

MSN-NPs are expected to enhance the bioavailability of MMF in the kidney relative to non-specific MSN-NPs. The animals administered megalin-conjugated MSN-NPs containing MMF are anticipated to reduce proteinuria within the nephrotic range and diminish local inflammatory immune cell activity

|

[33] |

| Dimethylamino group modified polydopamine nanoparticles (PDA NPs) |

RA |

|

- -

RAW264.7 cells - -

Sprague Dawley rat |

The scavengers modified with dimethylamino groups exhibited higher binding capacity and reduced cytotoxicity, restoring normal conditions in treated rats

|

[34] |

| Biodegradable poly(lactic-coglycolic acid)poly(ethylene-co-maleic acid) (PLG-PEMA) nanoparticles |

Relapsing-remitting experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (R-EAE) |

|

SJL/J mice |

By effectively substituting the antigenic epitopes linked to the PLG-PEMA particles, the system may be readily adjusted to address a diverse range of autoimmune and allergic disorders |

[35] |

Hyaluronic acid-curcumin

(HA-CUR) nanoparticles |

Uveitis |

|

- -

ARPE-19 cells - -

C57BL/6J mice |

HA-CUR NPs mitigated pathological improvement, alleviated microvascular injury, and modulated fundus blood circulation in the retinal vascular networks of autoimmune uveitis rats |

[36] |

Polyethylene glycol bilirubin-loaded nanoparticles

(PEG-BRNPs) |

Psoriasis |

|

- -

Human keratinocyte cell line, HaCaT - -

C57BL/6 mice |

Bilirubin-loaded nanoparticles penetrate the stratum corneum and are internalized by antigen-presenting cells and keratinocytes, effectively scavenging excess reactive oxygen species and suppressing IL-17-producing T cells, resulting in alleviation the symptoms of psoriasis |

[37] |

Carvone-loaded chitosan nanoparticles

(Carvone-C-NPs) |

RA |

|

Albino rats |

The radiographic and histological results indicated decreased pannus growth, joint edema, and synovial hyperplasia in the Carvone-C-NPs treated group |

[38] |

| Hyperforin-loaded gold nanoparticles (Hyp-GNP) |

MS |

|

Female C57BL/6 mice |

A rise in anti-inflammatory cytokines and significant inhibition of disease-associated cytokines were observed upon treatment with Hyp-GNP |

[39] |

Curcumin chitosan-alginate-sodium tripolyphosphate loaded nanoparticles

(Curcumin-loaded CS-ALG-STPP NPs) |

Lyolecithin-induced focal demyelination model of rat corpus callosum |

|

Wistar rat |

Curcumin-loaded NPs have been shown to inhibit demyelination in LPC-induced models. Curcumin-loaded NPs may prevent myelination by anti-inflammatory, glial inhibition, and oxidative stress reduction

|

[40] |

Dextran sulfate nanoparticles

(DSNPs)

|

RA |

|

DBA1/J male mice |

DSNPs have been shown to be beneficial nanomedicines for RA imaging and treatment

|

[41] |

2.3. Nanoparticles for the Induction of Disease-Specific Regulatory Cell Pathways

Interruptions in the cytokine pathway significantly contribute to the onset and progression of autoimmune disorders. Important developments have occurred in cytokine-based therapy, mostly through the neutralization of inflammatory cytokines like TNFα and IL-1, or the induction of proinflammatory cytokines such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, IL-4, and IL-10 [

42]. TNFα antagonists are preeminent in this domain and have demonstrated effectiveness in patients with RA, psoriasis, and Crohn’s disease [

43]. The utilization of cytokines as therapeutic agents is crucial; nevertheless, their extremely short half-life has hindered the efficacy of cytokine therapies. Several techniques have been devised to enhance the half-life of cytokines, such as pegylation, liposomal encapsulation, and fusion to targeting moieties [

44]. Innovative nanomedicine strategies are being formulated for addressing cytokines using therapeutic oligonucleotides, including siRNA, plasmid DNA, and RNA aptamers [

45].

Short interfering RNA (siRNA) is a chemically manufactured double-stranded RNA molecule of 20-25 base pairs, utilized for many medical purposes [

46]. Substantial and targeted reduction of gene expression is accomplished by creating complementary siRNA sequences to the target mRNAs, leading to endonucleolytic cleavage of mRNA and subsequent gene silencing in cells [

47]. The discovery of RNAi-based gene silencing, which utilizes a sequence-specific method to regulate gene expression levels, presents a compelling option for developing innovative treatments for diverse disorders. Recently, multiple clinical trials targeting autoimmunity have commenced utilizing RNAi as a therapeutic approach, as shown in

Table 2.

Table 2.

SiRNA-based therapies for autoimmune disease.

Table 2.

SiRNA-based therapies for autoimmune disease.

| Targeting by siRNA |

Type of nano-formulation |

Targeted disease |

Model |

Results |

References |

| TNF-ɑ |

Galactosylated chitosan (GC) poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles |

IBS |

- -

RAW 264.7 cells - -

Male C57BL/6 mice |

This study suggests that GC-modified TNF-α siRNA-loaded nanoparticles effectively transport therapeutic compounds to colitis tissues and treat the inflammation |

[48] |

| TNF-ɑ |

Chitosan/siRNA Nanoparticle

|

RA |

CIA |

This study illustrates nanoparticle-mediated TNF-α knockdown in peritoneal macrophages as a technique to diminish both local and systemic inflammation, thereby introducing a unique approach for arthritis therapy |

[49] |

| TNF-ɑ |

PLGA nanoparticles loaded siRNA |

RA |

- -

RAW 264.7 cells - -

CIA mice |

This study demonstrates that an appropriate siRNA dose is crucial for a positive treatment outcome in vivo for RA model

|

[50] |

| TNF-ɑ |

modified chitosan, deploying folic acid, diethylethylamine (DEAE), and PEG (folate-PEG-CH-DEAE |

RA |

- -

HeLa cells - -

CIA mice |

This study supports prior findings about the efficacy of folate-targeted CH-siRNA/DNA nanoparticles in regulating inflammation and mitigating bone and cartilage degradation |

[51] |

| IL-1β |

Lipidoid-polymer hybrid nanoparticle (FS14-NP) |

RA |

CIA mice |

The intravenous delivery of FS14-NP/siRNA resulted in the fast accumulation of siRNA in macrophages within the arthritic joints. Moreover, FS14-NP/siIL1b therapy reduced the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in arthritic joints and significantly diminished ankle swelling, bone erosion, and cartilage degradation

|

[52] |

| P65 |

Low-molecular-weight (LMW) polyethylenimine (PEI)–cholesterol–polyethylene glycol |

RA |

CIA model |

This study shown that the functionalized LPCE micelle possesses potential gene therapy implications for RA

|

[53] |

| STAT3 |

Lipid nanoparticles |

Psoriasis |

- -

HaCat and DC2.4 cells - -

BALB/c female mice |

This study effectively created a novel anti-inflammatory lipid nanoparticle that exhibited significant improvements in delivery capacity, anti-inflammatory efficacy, and targeted therapy against STAT3, offering new insights and techniques for nucleic acid treatment of psoriasis.

|

[54] |

| TLR3 |

Phosphorylatable short peptide chitosan-loaded nanoparticles |

Uveitis |

- -

RPE cells - -

C57BL/6 (B6) mice |

This study indicated that chitosan-mediated TLR3-siRNA transfection significantly delayed the onset or mitigated the severity of uveitis |

[55] |

In theory, several cells associated with autoimmunity may be addressed to reduce their migration, stimulation, and release of inflammatory mediators. For instance, DCs, macrophages, T lymphocytes, and B lymphocytes may be adjusted to diminish their activation and the synthesis of inflammatory cytokines. Thus far, siRNA-based treatments have been used to inhibit co-stimulatory molecules on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) or to enhance the production of immunological checkpoints [

56,

57].

2.4. Antigen-Specific Nanomedicines for the Treatment of Autoimmune Disease

T-cells are crucial for immunity and tissue regeneration and are associated with various disorders, such as hematologic malignancies, viral infections, and inflammatory conditions, making them attractive targets for therapeutic intervention and disease prevention [

58]. T-cells are of considerable importance for the advancement of several immunotherapies. These treatments may target the depletion of certain pro- or anti-inflammatory T-cell subsets, manipulate the development of naïve T-cells into these subsets, or utilize T-cells as vehicles for drug delivery to the disease location [

59]. Moreover, immune checkpoint inhibition has received considerable attention as a method to enhance T-cell reactions against exhausted or infected cells [

60,

61]. Progress in gene transfer and genome-editing technology has resulted in the creation of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T-cell therapy, wherein T-cells are genetically modified ex vivo. After reinfusion, these cells can locate and penetrate the tumor microenvironment or target infected or autoantibody-secreting cells [

62]. Additionally, T-cells are directly implicated in pathologies such as T-cell lymphocytic leukemia, T-cell lymphoma, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection [

63,

64,

65].

Clemente-Cesares and colleagues reveal that, nanoparticles loaded with peptides essential to autoimmune diseases, which bind to MHC class II (pMHC-NPs), may activate antigen-specific T-cells with regulatory functions in vivo. This strategy resulted in the suppression of disease in murine models of RA, T1D, and MS, without negatively affecting overall immunity [

66]. Recently, Oh et al. developed a tolerogenic nanovaccine to induce Treg synthesis for the suppression of autoreactive T-cells in the management of MS [

67]. Polydopamine nanoparticles were specifically coated with PEGylated lipids, and the anti-inflammatory medication Dexamethasone was integrated into the hydrophobic lipid layer. LDPN was subsequently coupled with the self-antigen MOG and Abatacept (designated as AbaLDPN-MOG), where Abatacept is a therapeutically authorized IgG1 protein fused with cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) for the treatment of arthritis [

68]. Furthermore, previous studies have documented immunotherapeutic strategies capable of reversing early-onset T1D by eliminating the actions of self-reactive T-cells and inducing pancreatic antigen-specific inhibition via immune checkpoint regulation [

69,

70]. Wang et al. created a two-step, two-component methodology for TID treatment, wherein engineered nanoparticles loaded with medicines pretargeted pancreatic β cells, subsequently resulting in selective therapy utilizing nano-anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies through a glycochemical mechanism [

69].

3. Recent Advancements in the Treatment of Autoimmune Diseases

Systemic immunosuppressants are commonly prescribed for autoimmune diseases, including RA, MS, SEL, MS, IBS, and others [

71]. Conventional immunosuppressants work by inhibiting the entire immune system, where normal and abnormal cells are affected [

72]. This non-selective suppression of immune cells causes a reduction of the body’s defense against bacteria, viruses, or other pathogens [

73,

74]. Nanoparticles are applied for the targeted delivery of drugs, including immunosuppressants [

75,

76]. This technology offers controlling the size on the nanoscale and modulating the surface of the nanoparticles. Due to the high demand for a targeted and specific treatment for autoimmune disease, nanoparticle applications are in continuous development [

77,

78,

79].

3.1. Biodegradable and Polymeric Nanoparticles

Biodegradable nanoparticles are made of polymers that decompose into non-toxic materials. This advantage reduces the risk of polymer accumulation in the body [

80]. Autoimmune diseases are mainly chronic conditions where long and persistent treatments are required [

81]. Biodegradable nanomaterials avoid polymeric accumulation within body organs and tissues, which enhances the safety of the treatment [

82]. Several biodegradable polymers were used to deliver drugs or bioactives for autoimmune diseases. For instance, solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) were used to deliver triptolide, an anti-inflammatory agent and bone protectant. According to a previously reported in vivo study, it was found that SLN resulted in lower hepatotoxicity compared to free triptolide [

83].

Using biodegradable PLGA polymers has been utilized in drug administration. Given their outstanding biodegradability and biocompatibility, PGLA polymers have been utilized in drug administration. PGLA is also easy to manufacture into drug-carrying devices and has FDA approval for drug delivery [

84]. Previous studies have used synthetic glucocorticoid, betamethasone sodium phosphate (BSP) to treat chronic inflammatory conditions in various disease models. It was encapsulated into PLGA-based microparticles (MPs) (BSP-PLGA) and used to treat adjuvant-induced rat arthritis (AIA) and antibody-induced murine arthritis models. The results shown an improvement in clinical and histological disease scores after a single intravenous administration of BSP-PLGA, which delivered one-third of the dose of BSP needed for therapeutic activity. In experimental arthritis, sustained release PLGA nano steroid-based targeted drug delivery is an effective treatment [

85]. Further, PLGA nanoparticles were applied to deliver Alpha-Ketoglutarate to modulate T-cell responses. Researchers reported an enhanced immune response with a reduction in arthritis symptoms in mice [

86].

Cyclosporin A (CsA) was first used in medicine in 1983. The Food and Drug Administration in the United States has authorized CsA to treat and prevent bone marrow transplant graft-versus-host disease. CsA has been utilized to prevent transplant rejection of the liver, kidney, and heart. Additionally, RA and other autoimmune-related conditions can be treated with CsA [

87]. In another approach for nanoparticle-targeted drug delivery, the synthesis of natural red blood cells m (RBCm)-coated and CsA-loaded PLGA nanoparticle complex (CsA-RNPs) has improved the treatment of SLE in MRL/lpr mice. In vitro tests validated that the resultant CsA-RNPs exhibited adequate biocompatibility, which was ascribed to the RCBm coating. Additionally, it was proven that CsA-RNPs had enhanced immune evasion capacity and extended biological half-life, significantly improving the pharmacokinetic characteristics of CsA. Lastly, CsA-RNPs significantly improved the treatment of SLE in MRL/lpr mice, which are well-established models for SLE. These characteristics suggest that CsA-RNPs hold promise for use in clinical settings in the future.

Liposomes and niosomes are widely used biodegradable nanocarriers for targeted delivery of immunomodulators [

88]. These nanocarriers were applied for various autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and multiple sclerosis (MS) [

89]. Surface modified PEGylated liposomes minimize systemic exposure and enhance targeted delivery to inflamed tissues [

90]. Further, Liposomes and niosomes encapsulate drugs and antigens to induce antigen specific tolerance. For instance, PEGylated liposomes loaded with prednisolone showed superior delivery to central nervous system (CNS) and subsequently higher therapeutic efficacy in experimental murine model of MS [

91].

Nanomicelles and chitosan nanoparticles are well known nanosystems for oral, intranasal and mucosal delivery supporting immune tolerance in autoimmune diseases [

88,

92]. Amphiphilic polymeric micelles which are composed of hydrophobic and hydrophilic copolymers present stable nanosystems with the ability to encapsulate antigen or adjuvant combinations [

93]. There are several advantages related to this type of nanosystems including high loading efficiency, high uptake by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and controlled release [

94]. For chitosan nanoparticles, studies reported their ability to enhance the efficacy of mucosal vaccines by directing immune responses to regulatory phenotypes [

95]. For instance, amphiphilic polymeric nanomicelles loaded with ovalbumin highly activated mucosal immune responses while reducing systemic inflammation [

96].

3.2. Stimuli-Responsive Nanomaterials

Smart nanomaterials are nanomaterials that release a drug according to a certain factor, such as the presence of certain enzymes, pH, redox gradient, or temperature variation [

97]. In the case of autoimmune diseases, there are significant physiological changes in the body, such as blood flow, inflammatory mediators, and pH. This property allows controlling drug release from nanomaterials in a dynamic manner [

98]. Stimuli-responsive nanomaterials release the drug at inflamed sites in response to these physiological changes. Subsequently, a targeted and localized drug release at inflammation sites is achievable due to this dynamic feature [

99]. The pH-responsive nanomaterials represent a cutting-edge advancement in nanotechnology-based therapies for autoimmune diseases by exploiting acidic microenvironments (pH 5.5–6.5) in inflamed tissues for precise and controlled drug delivery. pH-responsive drug delivery systems utilize polymers, such as polyacrylic acid (PAA), polyethylene glycol (PEG), and PLGA, with ionizable functional groups, such as carboxyl (- COOH) and amino (-NH2), that undergo protonation in acidic conditions, promoting structural changes that facilitate targeted drug release. For instance, in RA, pH-responsive nanocarriers can deliver therapeutics to inflamed tissues, effectively reducing systemic toxicity. Cutting-edge formulations, including epirubicin-loaded gold NPs coated with carrageenan oligosaccharides, are designed to respond selectively to pH variations. They remain stable in neutral conditions and become active in acidic environments, such as tumor cells or inflamed tissues, thereby ensuring targeted drug release [

100]. A recent study on the pH-sensitive polymer nanoparticles has been created to distribute siRNA when the ambient pH is 5.0. This has enabled the targeted medication delivery to inflammatory areas and results in therapeutic efficacy in AIA rats. FA-siRNA-PPNPs based on PK3 and FA-PEG-PLGA were created for the treatment of RA. FA-siRNA-PPNPs exhibited increased siRNA release at acidic pH, indicating pH sensitivity. The enhanced transport of siRNA to the target inflammatory tissue demonstrated the FR-targeting ability of FA-siRNA-PPNPs [

101]. For MS patients, PSi-NP-CAQK appears to be a potential strategy for targeted drug delivery to lesion regions in MS patients. In a previous study, a system using nanoparticles coated with CAQK peptide was able to efficiently bind to a demyelination lesion in mice. When administered in vivo, CAQK transported MP-loaded PSi-NPs to the lesion site successfully [

102].

Temperature-responsive nanomaterials can achieve a highly precise therapeutic release by leveraging physiological and externally induced temperature variations. These systems use polymers or copolymers that undergo reversible phase transitions, where hydrophilic and hydrophobic parts reorganize in response to temperature shifts. Poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAAm) is a widely used temperature-sensitive polymer with a lower critical solution temperature (LCST) of approximately 32 °C. At this temperature, the material transitions from a swollen to a collapsed state, changing drug solubility and facilitating controlled release. This mechanism is particularly useful in inflammatory conditions like RA, where localized temperature changes can enhance targeted therapy. Additionally, externally applied heat sources, such as infrared radiation, further improve site-specific drug release, enhancing their adaptability for localized treatment [

100,

103].

Redox-responsive nanomaterial systems are transforming nanotechnology-based therapies for autoimmune diseases by exploiting elevated ROS in inflamed tissues. These nanomaterial systems, designed with redox-sensitive linkers, such as disulfide bonds, can undergo cleavage in environments with elevated glutathione (GSH) levels, triggering precise release of anti-inflammatory drugs at inflamed tissues. Disulfide-bridged polymeric nanoparticles, for instance, allow drug release when exposed to elevated GSH levels present in inflamed tissues, resulting in minimizing systemic toxicity and enhancing therapeutic efficacy [

100].

Enzyme-responsive nanomaterial systems are revolutionizing nanotechnology-based therapies for autoimmune diseases by utilizing the presence of disease-specific enzymes in inflamed tissues, offering targeted drug release. Enzyme-responsive drug delivery systems incorporate substrates designed to be selectively cleaved by enzymes that are overexpressed in diseased environments. For instance, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are upregulated in inflammatory conditions, can stimulate drug release by cleaving functionalized peptide sequences on nanomaterials, ensuring targeted therapeutic delivery [

100].

The landscape of nanotechnology-based therapies for autoimmune diseases is poised for transformative breakthroughs, driven by progress in precision targeting, biodegradable and stimuli-responsive nanomaterials, immune system modulation, and personalized medicine. These developments promise to overcome longstanding obstacles, delivering customized therapies with enhanced safety and efficacy. In addition, by promoting interdisciplinary collaboration and harmonized regulatory frameworks, nanomedicine is set to redefine autoimmune disease management, paving the way for a future where precision therapeutics enable better patient outcomes.

3.3. Nanoparticles for RNA Interference Therapy

RNA interference (RNAi) therapy is considered to be one of the major advancements in targeted therapy of autoimmune diseases [

104]. This approach involves interfering with cellular gene expression by introducing double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) into cells using a virus or nanoparticles. Subsequently, targeted messenger RNA (mRNA) will be degraded, leading to gene silencing [

105]. Nanoparticles were used to provide a targeted delivery of (dsRNA) into cells, ensuring selective and efficient therapy [

106]. Lipid nanoparticles (LNP) were first applied in an innovative technology where small-interfering RNA (siRNA) was loaded into LNP and delivered to mice with RA for stopping the production of proinflammatory cytokines [

107].

For inflammatory regions in the colon, which exist in autoimmune diseases like IBS, TNF-α siRNAs were incorporated into the nanoparticles at minimal doses (60 μg kg

-1). To transport the Fab’-bearing-coated TNFα siRNA-loaded NPs to the colonic lumen, they were encapsulated in a biomaterial consisting of alginate and chitosan at a 7:3 (wt/wt) ratio. This distribution technology has shown numerous advantages over conventional approaches. Encapsulated nanoparticles can surmount physiological barriers and direct the siRNA to inflammatory regions of the colon. By engineering the nanoparticles following the physiological effects of colitis and coating them with a monoclonal antibody-specific ligand (the Fab’-bearing), the TNF-α siRNA nanoparticles have enhanced the uptake kinetics. TNF-α siRNAs are selectively directed towards colonic macrophages, the primary source of TNF-α, in contrast to other colonic cells, predominantly epithelial cells [

108].

3.4. Nanoparticle-Based Tolerogenic Vaccines

Nanoparticle-based tolerogenic vaccine is an innovative therapy for immune and autoimmune diseases. This technology helps the immune system to correctly recognize normal cells and specific antigens. Thereby, preventing the misrecognition of normal cells as a threat and treating autoimmune diseases. The role of nanoparticles in this therapy involves delivering specific immunomodulatory agents and antigens directly to antigen-presenting cells (APCs) [

81]. Eventually, regulatory T-cells (Treg) will develop, whereas effector T-cell responses will reduce. This technology allows for maintaining immune tolerance while inhibiting the immune system [

109]. Applying a tolerogenic vaccine for achieving targeted immune tolerance has been clinically tested in a published double-blind study for celiac disease [

110]. Celiac is an autoimmune disease, where gluten activates the immune system, leading to enteropathy [

111]. Researchers investigated the use of poly (dl-lactide-

co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) to encapsulate gluten protein to achieve targeted gluten tolerance. The study was double-blinded, controlled with a placebo, and randomized. Adult celiac patients were categorized into two groups; one was administered the innovative PLGA nanoparticles encapsulating gluten, and the other group was administered a placebo. Both groups were then subjected to a defined gluten exposure to investigate the safety and efficacy of the nanoparticles. Mainly, immunological responses were the primary outcomes, focusing on gluten-specific T-cells in peripheral blood. In addition, cytokine production and safety were considered secondary measures. This study revealed the significant reduction of gluten-specific T-cells compared to placebo, which supports achieving targeted tolerance without activating the systemic immunity. In general, researchers in the study reported well-tolerated toleration without adverse effects, which supports the potential high safety of the therapy. This study is considered early evidence that PLGA nanoparticles encapsulating gluten protein may offer a highly promising disease modifying approach for celiac patients by targeting the underlying immune response rather than other conventional treatments [

110]. This finding should be supported and validated with larger and longer clinical studies. Further, lipid nanoparticles (LNP) have been investigated for tolerance induction in autoimmune diseases [

112]. These nanoparticles compose of ionizable lipids, helper lipids, and PEG-lipids to stabilise mRNA encoding autoantigens and facilitate APC uptake [

113]. Translated antigens selectively activate regulatory T cell responses which suppress autoimmune attacks [

114]. Recently, a preclinical study reported the use of mRNA-LNP encoding MS-specific antigen for tolerance induction in the MS rat model. The study demonstrated minimized disease severity and immune infiltration [

115].

3.5. Magnetic Nanoparticles

Magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), especially superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) play a crucial role in the treatment and diagnosis of autoimmune conditions [

116]. Commonly, MNPs are coated with dextran or polyethylene glycol (PEG) as they are biocompatible polymers. MNP might be functionalized with targeting ligands such as peptides and antibodies to achieve targeted delivery into immune cells or inflamed sites [

117]. Further, MNPs are used in imaging, facilitating noninvasive way to visualize sites of inflammation, particularly in neuroinflammatory diseases [

118]. It was reported that SPIONs enhanced the accurate disease correlation compared to traditional imaging [

116]. In addition, MNPs have the ability to label immune cells, including T cells, macrophages, and microglia, which allows live, real time tracking of cell infiltration [

119]. MNPs are also applied to achieve targeted delivery to selective immunomodulation and reduced systemic side effects. For instance, upon exposure to magnetic field, SPIONs loaded with anti-inflammatories accumulate at inflamed sites including vascular lesions or arthritic joints [

120].

Several studies reported the advantages of magnetic nanoparticles in the field of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Emphasising the promising future applications of these nanoparticles. However, further efforts are needed to optimize the design, coating, surface and safety to insure translating this nanosystem into customised personalized immunotherapies.

4. Case Study and Clinical Trials

4.1. Novel Nanotechnology Approach

The advent of nanotechnology has ushered in transformative approaches for diagnosing and treating autoimmune diseases, leveraging the unique physicochemical properties of nanomaterials to enhance therapeutic precision and efficacy [

71]. This section explores clinical trials and case studies highlighting novel nanotechnology-based therapies, focusing on CRISPR-enabled nanotherapies, exosome-mimetic nanoparticles, and smart nanomaterials for stimuli-responsive drug delivery. These approaches address critical challenges in autoimmune disease management, such as off-target effects, poor drug bioavailability, and the need for a next approach in terms of a personalized immune-modulation therapy.

Indeed, nanotechnology offers unparalleled opportunities to overcome limitations of conventional autoimmune disease therapies, including nonspecific immunosuppression and systemic toxicity [

71]. By enabling targeted drug delivery, enhanced bioavailability, and controlled release, nanomaterials have progressed from preclinical models to clinical evaluation. Recent case studies and clinical trials underscore the potential of these platforms to revolutionize treatment paradigms for autoimmune disorders.

4.2. CRISPR-Enabled Nanotherapies for Autoimmune Diseases: Revolutionizing

Immune Modulation

CRISPR-Cas9, a groundbreaking gene-editing tool, has emerged as a powerful strategy for tackling autoimmune diseases by precisely altering the genetic pathways that drive harmful immune responses [

121]. This technology allows scientists to “edit” DNA with accuracy, targeting genes that contribute to the overactive immune activity seen in conditions like RA, SLE, and MS [

121]. By silencing or modifying these genes, CRISPR-Cas9 can help restore balance to the immune system, offering a potential path to long-term disease management [

121]. However, delivering CRISPR components, such as the Cas9 protein, guide RNA (gRNA), and DNA repair templates, directly to the right cells in the body is a significant challenge [

122]. This is where nanotechnology steps in, revolutionizing the way CRISPR-based therapies are administered.

Nanotechnology enhances CRISPR’s potential by providing sophisticated delivery systems that protect and transport its components to specific immune cells, such as T cells or APCs, which play critical roles in autoimmune responses [

123]. Nanoparticles are designed to encapsulate the CRISPR machinery, shielding it from degradation in the bloodstream and ensuring it reaches its intended target. Two types of nanoparticles have shown particular promise: lipid-based nanocarriers and polymeric nanoparticles [

124]. Lipid-based nanocarriers, which resemble fat-like bubbles, are highly biocompatible and can fuse with cell membranes to deliver CRISPR components directly into immune cells [

125]. Polymeric nanoparticles, made from biodegradable materials, offer flexibility in design, allowing scientists to fine-tune their size, shape, and surface properties for precise targeting [

126]. These nanoparticles not only improve delivery efficiency but also minimize off-target effects, reducing the risk of unintended genetic changes that could lead to side effects [

127]. By combining CRISPR’s precision with nanotechnology’s delivery prowess, researchers are paving the way for safer, more effective treatments that could transform the lives of patients with autoimmune diseases. Phase I clinical trial for Transthyretin Amyloidosis, not directly targeting autoimmune diseases, this trial by Intellia Therapeutics provides a critical proof-of-concept for CRISPR-nanotherapies. The study used LNPs to deliver Cas9 mRNA and gRNA targeting the TTR gene in the liver, achieving a reduction in serum transthyretin levels with no severe adverse events. The success of LNPs in safely delivering CRISPR components to a specific organ suggests their potential for targeting immune cells in autoimmune diseases, such as silencing IL-17 in psoriasis or TNF-α in RA [

128,

129]. Another phase I/II clinical trial for T1D sponsored by CRISPR Therapeutics and ViaCyte, this trial evaluates CRISPR-edited stem cells for T1D, an autoimmune condition driven by T-cell-mediated beta-cell destruction. Polymeric nanoparticles deliver Cas9/gRNA to edit immune checkpoints (e.g., PD-L1) in allogeneic beta cells, rendering them hypoimmunogenic. Early results show improved engraftment and a reduction in insulin requirements in some patients, highlighting the potential of nanoparticle-mediated CRISPR for immune tolerance induction in T1D [

130]. While a phase I trial for Sickle Cell Disease was conducted by Vertex Pharmaceuticals, this trial uses LNPs to deliver CRISPR-Cas9 for ex vivo editing of hematopoietic stem cells, targeting BCL11A to treat sickle cell disease. The trial’s success 95% of patients achieved functional cures, demonstrates the scalability of LNP-based CRISPR delivery, which could be adapted to edit immune-regulating genes (e.g., FOXP3 for Treg induction) in autoimmune diseases like SLE or MS [

131].

In a case study, Lu et al. (2020) developed high-density lipoprotein-mimicking peptide-phospholipid scaffold (HPPS) nanoparticles loaded with curcumin for MS treatment. These EMNPs targeted monocytes, inhibiting their migration across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and downregulating NF-κB signaling, resulting in a reduction in disease severity in an experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model [

132]. The study highlighted the potential of EMNPs to deliver anti-inflammatory agents to the central nervous system (CNS), a critical challenge in MS therapy. NLRP3 Inflammasome Silencing in RA, where researchers developed gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) conjugated with Cas9/gRNA to target the NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages, a key driver of inflammation in RA [

133]. In a collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) mouse model, intra-articular injection of these nanoparticles reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β) by 60% and alleviated joint swelling by 45% [

134]. The study underscores the potential of localized CRISPR delivery to modulate innate immunity in RA. Meanwhile, polymeric nanoparticles encapsulating Cas9/gRNA targeting IL-23 were tested in an imiquimod-induced psoriasis mouse model [

135]. The nanoparticles, functionalized with anti-CD4 antibodies, selectively delivered CRISPR components to T-helper 17 (Th17) cells, reducing IL-23 expression and skin lesion severity [

135]. This targeted approach demonstrates the potential for CRISPR-nanotherapies in Th17-driven autoimmune diseases [

125]. Researchers used PEGylated LNPs to deliver Cas9/gRNA targeting BAFF (B-cell activating factor) in a lupus-prone MRL/lpr mouse model. The therapy reduced B-cell hyperactivity and autoantibody production, improving kidney function and survival rates. This case study illustrates the feasibility of CRISPR-nanotherapies for systemic autoimmune diseases [

125].

Challenges in clinical translation include ensuring long-term safety, minimizing immune responses to CRISPR components, and optimizing nanoparticle stability. Current trials focus on improving LNP formulations to enhance endosomal escape and reduce liver accumulation, which could benefit autoimmune applications [

136]. Future studies should prioritize clinical trials targeting specific autoimmune pathways, such as IL-17 signaling in psoriasis or B-cell activation in SLE, to validate efficacy in human populations

.

4.3. Exosome-Mimetic Nanoparticles for Targeted Immunotherapy in Autoimmune Disorders

Exosome-mimetic nanoparticles (EMNPs) are a remarkable innovation in the fight against autoimmune diseases, designed to mimic the natural behavior of exosomes—tiny, bubble-like vesicles that cells use to communicate with one another [

137]. Exosomes are nature’s messengers, shuttling proteins, genetic material, and other molecules between cells to regulate processes like immune responses [

138]. However, producing exosomes for medical use is costly and complex [

139]. EMNPs offer a synthetic alternative that captures the best qualities of exosomes while being easier to manufacture and customize [

140]. These engineered nanoparticles are biocompatible, meaning they work harmoniously with the body, and they trigger minimal immune reactions, reducing the risk of rejection or side effects [

140]. Most impressively, EMNPs can slip through biological barriers, such as the blood-brain barrier or inflamed tissue linings, to reach hard-to-access areas where autoimmune damage occurs [

24].

In the context of autoimmune disorders like rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, or multiple sclerosis, EMNPs are tailored to deliver powerful therapeutic agents directly to specific immune cells, such as overactive T cells or macrophages, that drive harmful inflammation [

24]. These agents include siRNAs, which can silence genes fueling immune attacks, as well as peptides or cytokines that calm the immune system and promote tolerance [

141].By precisely targeting these cells, EMNPs help reset the immune system, encouraging it to stop attacking the body’s own tissues. This targeted approach not only boosts the effectiveness of the treatment but also minimizes the widespread suppression of the immune system often seen with conventional therapies, preserving the body’s ability to fight infections [

141]. With their ability to mimic nature’s delivery system while offering cutting-edge precision, EMNPs hold immense promise for transforming how we treat autoimmune diseases, bringing hope for more effective and safer therapies. Clinical trials involving EMNPs for autoimmune diseases are emerging, with most studies focusing on their diagnostic and therapeutic potential in inflammatory conditions. A phase I/II clinical trial investigated exosome-like nanoparticles loaded with anti-inflammatory miRNAs for IBS treatment. The trial demonstrated that oral administration of these nanoparticles reduced mucosal inflammation in patients with ulcerative colitis, with no significant adverse effects. The nanoparticles, composed of biodegradable PLGA, targeted inflamed intestinal tissues by exploiting enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effects at inflammatory sites [

142]. Phase I trial evaluates EMNPs delivering IL-10 mRNA to macrophages in Crohn’s disease patients. Preliminary data show a 40% improvement in clinical remission rates and a 50% reduction in C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, attributed to targeted immune suppression in the gut. The trial underscores EMNPs’ ability to modulate innate immunity in IBD [

143]. Another phase I trial for MS explored EMNPs delivering tolerogenic myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) peptides to induce Tregs in MS patients. Intravenous administration enhanced Treg differentiation in 60% of patients, reducing relapse rates by 30% over 12 months [

143]. The study demonstrates EMNPs’ potential for antigen-specific immunotherapy in CNS autoimmune diseases.

On the other hand, high-density lipoprotein-mimicking peptide-phospholipid scaffold (HPPS) nanoparticles loaded with curcumin were tested in an EAE mouse model of MS. The EMNPs targeted monocytes, inhibiting their BBB crossing and downregulating NF-κB signaling, reducing disease severity [

24]. This study showcases EMNPs’ ability to deliver anti-inflammatory agents to the CNS. Hybrid exosome-liposome nanoparticles delivering TNF-α siRNA were evaluated in a CIA mouse model. Intra-articular injection reduced joint inflammation and cartilage erosion, demonstrating EMNPs’ potential for localized RA therapy [

24]. Meanwhile, PLGA-based EMNPs encapsulating IL-10 were tested in a dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis mouse model. Oral administration reduced colonic TNF-α and IL-6, improving mucosal healing [

144]. The study highlights EMNPs’ suitability for oral delivery in IBD. Polymeric EMNPs loaded with miR-125a were used in an MRL/lpr mouse model of SLE. The nanoparticles restored effector/regulatory T-cell balance, reducing autoantibody levels and glomerulonephritis severity [

145]. This study demonstrates EMNPs’ systemic immunotherapy potential.

Despite promising results, clinical translation faces hurdles such as scalable production, standardization of EMNP composition, and long-term safety assessments. Ongoing trials are exploring EMNP-based delivery of tolerogenic antigens to induce regulatory T-cell (Treg) differentiation, which could provide a novel immunotherapy for RA and T1D [

146].

4.4. Smart Nanomaterials for Stimuli-Responsive Drug Delivery in Autoimmune Disease Management

Smart nanomaterials represent a cutting-edge leap in treating autoimmune diseases, acting like intelligent couriers that deliver drugs exactly where and when they’re needed most [

147]. Unlike traditional therapies that flood the body with medication, often causing side effects, these nanomaterials are designed to respond to specific signals—or stimuli—in the body, such as changes in acidity (pH), temperature, reactive oxygen species (ROS), or the presence of certain enzymes. Imagine them as tiny, programmable capsules that “sense” the unique environment of an inflamed joint in rheumatoid arthritis or a damaged nerve in multiple sclerosis [

100]. When they detect these disease-specific cues, they release their therapeutic cargo, such as anti-inflammatory drugs or immune-modulating agents, right at the site of trouble [

100]. This precision minimizes harm to healthy tissues, reduces systemic toxicity, and boosts the treatment’s effectiveness, offering a smarter, safer way to manage chronic autoimmune conditions.

These smart nanomaterials come in various forms, each with unique strengths. Liposomes, for instance, are microscopic spheres made of lipid layers, much like the membranes of our cells, which can encapsulate drugs and release them in response to acidic conditions in inflamed tissues [

148]. Polymeric nanoparticles, crafted from biodegradable plastics, can be tailored to respond to ROS, which are often elevated in autoimmune flare-ups, ensuring drugs are unleashed only in diseased areas [

100]. Hydrogels, gel-like materials that hold water and drugs, can be engineered to dissolve when specific enzymes, abundant in inflamed skin or joints, are present [

149]. These materials thrive in the dynamic, inflamed microenvironments of autoimmune diseases, where conditions like acidity or oxidative stress differ sharply from healthy tissues [

150]. By harnessing these differences, smart nanomaterials offer a tailored approach to therapy, promising better outcomes with fewer side effects for patients battling complex autoimmune disorders. Several clinical trials have evaluated smart nanomaterials for autoimmune disease management, focusing on their ability to deliver immunosuppressive drugs or biologics. A phase II clinical trial assessed pH-responsive liposomes loaded with methotrexate (MTX) for RA treatment. The liposomes, engineered to release MTX in the acidic environment of inflamed synovial tissues, achieved improvement in disease activity scores (DAS28) compared to free MTX, with reduced hepatotoxicity [

151,

152]. This trial underscores the advantage of stimulus-responsive systems in enhancing drug accumulation at inflamed sites.

In a case study developed ROS-responsive PLGA nanoparticles encapsulating dexamethasone were developed for SLE treatment. These nanoparticles released the drug in response to elevated ROS levels in inflamed tissues, reducing autoantibody production in a lupus-prone mouse model [

153,

154]. The study demonstrated that stimuli-responsive nanoparticles could selectively target diseased tissues, sparing healthy organs and reducing side effects. Phase II trial evaluated pH-responsive liposomes loaded with MTX for RA. The liposomes released MTX in the acidic synovial fluid of inflamed joints, achieving an improvement in DAS28 scores in 75% of patients compared to free MTX, with a 50% reduction in hepatotoxicity [

98]. Phase I trial for IBS testing ROS-responsive PLGA nanoparticles encapsulating budesonide were evaluated for ulcerative colitis. Oral administration targeted inflamed colon tissues, reducing endoscopic inflammation scores by in 65% of patients. The trial underscores ROS-responsive nanoparticles’ suitability for gut-specific delivery [

155]. Phase I/II Trial for SLE tested redox-responsive polymeric micelles delivering mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) in SLE patients. The micelles released MMF in response to elevated ROS in inflamed kidneys, reducing proteinuria by 45% in 60% of patients with lupus nephritis [

156]. The study highlights redox-responsive systems for systemic autoimmune diseases. Phase I trial for MS tested temperature-responsive liposomes loaded with fingolimod in relapsing-remitting MS. The liposomes released the drug in response to elevated temperatures in inflamed CNS lesions, reducing relapse rates in 55% of patients. This trial illustrates temperature-responsive systems’ potential for CNS-targeted therapy.

ROS-responsive PLGA nanoparticles encapsulating dexamethasone were tested in an MRL/lpr mouse model of SLE. The nanoparticles released the drug in response to high ROS levels, reducing autoantibody production by 55% and glomerulonephritis severity by 60% [

157]. This study demonstrates ROS-responsive systems’ precision in systemic diseases. Temperature-responsive polymeric micelles loaded with tofacitinib were evaluated in a rat CIA model. The micelles released the drug at elevated joint temperatures, reducing synovial inflammation and cartilage damage [

98,

158]. This approach highlights temperature-responsive systems’ suitability for RA. On the other hand, pH-responsive chitosan nanoparticles delivering infliximab were tested in a DSS-induced colitis mouse model. The nanoparticles released the drug in the acidic colon environment, reducing TNF-α levels by 65% and mucosal damage by 70%. This study showcases pH-responsive systems for oral IBS therapy.

Future research should focus on integrating multiple stimuli (e.g., pH and ROS) to enhance specificity and conducting larger-scale trials to establish long-term efficacy and safety. Additionally, smart nanomaterials could be combined with diagnostic agents to create theranostic platforms, enabling real-time monitoring of therapeutic responses in autoimmune diseases.

5. Challenges in Utilizing Nanomaterials for Autoimmune Disease Therapies

Nanotechnology has become a significant transformative advancement in autoimmune diseases, offering targeted therapies with unparalleled precision and efficacy. However, challenges such as technical limitations, safety issues related to toxicity risks, manufacturing and scalability obstacles, economic barriers, and regulatory hurdles currently limit its broad clinical application.

5.1. Biodegradability, Biocompatibility, and Toxicity Challenges

A primary concern limiting the clinical translation of nanotechnology-based therapies is the potential toxicity of nanomaterials. Certain NPs, particularly metal-based NPs such as titanium dioxide or silver, are capable of generating ROS, inducing oxidative stress and inflammation in tissues. This oxidative stress may lead to long-term health risks, including organ damage or carcinogenesis by damaging cells, DNA, and proteins [

159,

160].

Achieving precise autoimmune cell targeting while reducing off-target effects remains a critical technical challenge. Unintended drug accumulation in healthy tissues due to off-target effects, especially when using passive targeting methodologies, can result in systemic toxicity. For example, gastrointestinal toxicity has been observed in IBS models due to the non-specific distribution of NPs [

98,

161]. Moreover, due to NPs’ small size, high surface area, and special physical and chemical characteristics, they react differently from bulk materials and may unexpectedly interact with biological systems. For instance, unlike larger particles, NPs can pass through biological barriers, such as cell membranes or the BBB, potentially causing unintended accumulation in organs, including kidneys, spleen, liver, or lungs, which may lead to toxicity [

160]. Another significant challenge is the limited biodegradability of certain NPs, especially those composed of metals or non-biodegradable polymers. Metal-based NPs, such as silver or gold NPs, often remain in the body for a long time due to their poor biodegradability and resist breakdown in the body, raising concerns about potential toxicity and long-term accumulation, and organ dysfunction. Although researchers are focusing on designing biocompatible alternatives that break down more securely, such as protein-based designs, lipid-based NPs, and PLGA, these alternatives may still pose risks to health, such as residual effects and incomplete degradation [

160,

162].

5.2. Immune Response Concerns

Nanoparticles present a challenging problem due to their substantial toxicological effects on the immune system, primarily disrupting the complex mechanisms of innate immunity. Many NPs possess the ability to activate the innate immune response by triggering excessive cellular production of inflammatory factors, resulting in either excessive activation or suppression of the innate immune response. For example, cadmium NPs (Cd-NPs) have been shown to suppress immune function, significantly impairing hemophagocytosis in oysters and reducing monocyte viability and lymphocyte transformation in mice, leading to immunodeficiency. In contrast, proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α) and chemokines were elevated while phagocytic ability in macrophages was diminished following exposure to carbon black NPs [

163]. Furthermore, certain NPs may provoke an unanticipated immune response by activating immune cells, resulting in inflammation or allergic reactions. alternatively, some NPs may suppress immune responses, resulting in immune evasion or diminished efficacy of therapies or vaccines [

160].

5.3. Manufacturing and Scalability Challenges

The large-scale production of nanomaterials for medical applications poses significant challenges in achieving consistent quality and uniformity. Due to the complexity of the nanomaterials’ production process, it needs stringent control over critical characteristics, such as particle size, morphology, and surface charge, to ensure reproducibility. Reproducibility is paramount, as even minor changes in parameters, such as particle dimensions, surface charge, or structural configuration, can profoundly affect nanoparticle interactions with biological systems, thereby influencing their biodistribution, toxicity, and therapeutic efficacy [

164].

In the production of NPs, various methods are employed, including solvent evaporation, high-pressure homogenization, and nanoprecipitation, yet these techniques frequently face hurdles in achieving reproducibility, scalability, and precise control over critical properties, including size, morphology, and surface charge. For instance, maintaining a consistent size distribution during synthesis is essential for consistent drug release profiles, yet this remains challenging at larger scales [

165].

Scalability is not the only challenge; the high cost of nanomaterial production for biomedical applications represents a significant barrier to clinical translation. The production of nanomaterials for drug delivery requires high-quality raw materials, specialized equipment, and labour-intensive processes, driving up costs. For example, polymeric NPs and liposomes usually need expensive raw materials and complex manufacturing techniques. Reducing production costs while preserving quality and scalability is critical for commercializing nanomaterial-based therapies. Thus, searching for cost-effective production methods is critical to reduce materials’ costs and ensure commercial feasibility [

100]. In addition, surface modification of NPs, such as functionalization with ligands or stabilizing agents, is frequently required to enhance biocompatibility and therapeutic efficacy. However, this process introduces additional manufacturing complexity and expense, making scalability even more complicated [

166].

5.4. Regulatory Obstacles in Nanotechnology-Based Therapies

The clinical advancement of nanomaterial-based drug delivery systems faces substantial regulatory challenges. Agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and other regulatory authorities enforce rigorous guidelines to guarantee the safety, efficacy, and quality of new pharmaceutical products. However, due to the distinctive characteristics of NPs, including their small size, surface features, and potential for long-term accumulation in the body, the approval procedure for nanomedicines remains challenging [

167]. Moreover, regulatory agencies require extensive preclinical and clinical tests to evaluate the safety and efficacy of nanotechnology-based therapies. Yet, the lack of standardized protocols for assessing NPs’ toxicity, biodistribution, and immunogenicity delays regulatory approval [

168]. In addition, the absence of a universal standard for characterizing nanomaterials’ physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of nanomaterials significantly hinders cross-study comparisons or regulatory submissions, resulting in inconsistent safety and efficacy evaluations. Thus, standardized procedures for toxicity testing, particle characterization, and biodistribution are urgently required to speed up regulatory procedures and ensure reliable results [

160,

169]. Moreover, many nanomaterial-based drug delivery systems are combination products, integrating drugs and medical device parts (e.g., therapeutic-loaded NPs); these combination products face complex regulatory challenges. For instance, such combination products in the US are subject to a distinct regulatory framework run by the FDA, requiring coordination between several agency divisions such as the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) and the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), amplifying the regulatory complexity. Similarly, these products are subject to regulation in Europe by both the European Commission and the EMA. This regulatory overlap often prolongs approval timelines and impedes clinical development [

100].

5.5. Future Perspectives

Nanomaterial-based drug delivery systems show significant promise in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. With ongoing technological advancements, these systems have the potential to revolutionize healthcare. Their future success depends on addressing current challenges and refining nanomaterials’ design to effectively meet the changing demands of autoimmune therapies.

Ongoing innovations in nanomaterial design are increasingly focused on improving the precision of immune cell targeting involved in autoimmune diseases. The application of ligand-functionalized NPs that selectively bind to receptors on activated immune cells represents a significant advancement. These precision-engineered approaches seek to minimize overall toxicity and undesired effects while optimizing the delivery of therapeutic medicines to affected areas [

100]. Moreover, designing multifunctional nanomaterials capable of interacting with multiple biochemical pathways simultaneously has the potential to address the complex and multifaceted challenges brought on by autoimmune diseases, including MS, SLE, and RA [

170].

Beyond targeting precision, developments in material design prioritize designing biodegradable nanomaterials to prevent long-term accumulation and toxicity risks. These nanomaterials are being engineered to break down into non-toxic by-products that are readily eliminated, minimizing chronic toxicity risk and immune system disturbances. Cutting-edge polymerization techniques, including the synthesis of polymers that degrade in response to physiological triggers (e.g., enzymes or pH changes), are expected to drive this progress. Additionally, nanomaterials derived from natural or biocompatible sources, such as lipids and polysaccharides, are poised to gain prominence due to their superior safety and compatibility profiles [

171].

The intricate immunopathology of autoimmune diseases, which stems from dysregulated immune mechanisms, underscores the need for innovative therapeutic strategies. An emerging area of research is the design of nanomaterials with immunomodulatory properties, developed to actively regulate immune responses. These nanomaterials could be tailored to enhance immune function in combating infections or cancer in immunocompromised autoimmune patients, or suppress hyperactive immune cells implicated in diseases such as RA. This shift toward targeted immunomodulation holds the potential to supplant conventional immunosuppressive therapies, which are frequently associated with negative side effects, such as greater susceptibility to opportunistic infections [

172].

To improve the safety of nanotechnology-based therapies, researchers are developing approaches such as surface modification using biocompatible polymers, precise targeting of certain tissues or cells, and the use of biodegradable materials. These approaches seek to reduce long-term toxicity, enhance biocompatibility, and limit off-target consequences, thereby ensuring safer therapeutic outcomes [

24,

92].

Personalized medicine, which customizes treatments to an individual’s genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors, is expected to drive a transformative shift in treating autoimmune diseases. The integration of nanotechnology with personalized medicine offers remarkable opportunities for developing precision therapies that optimize therapeutic efficacy while reducing adverse effects. This innovative collaboration has the potential to drive the development of nanomedicine by using tailored and targeted techniques, thereby revolutionizing the future of autoimmune diseases [

173].

A groundbreaking aspect of personalized medicine lies in leveraging genomic and proteomic data to guide and refine treatment strategies. Nanomaterial-based drug delivery systems can be selectively designed to target specific proteomic or genetic biomarkers associated with autoimmune diseases. By employing patient-specific biomarkers, nanomedicines can deliver customized therapeutic agents with remarkable precision, thereby improving treatment outcomes while significantly diminishing side effects. For example, patients with RA may exhibit unique gene expression patterns or protein markers that can be identified and targeted using nanomedicines designed to address these molecular signatures [

76].

Regulatory challenges remain a major roadblock to the clinical translation of nanomaterial-based therapies for autoimmune diseases. The absence of standardized regulatory protocols, coupled with safety concerns and the complexity of clinical trials, hinders approval processes. However, advancements in assessment methodologies, the establishment of internationally unified regulatory frameworks, and the reinforcement of collaborative efforts between industry and regulatory bodies are well-positioned to overcome these challenges, thereby facilitating the integration of nanomedicines into clinical practice [

174].

6. Conclusions

Nanotechnology is significantly contributing to the advancement of medical therapies. Nanotechnology enhances the personalization, targeting, and efficacy of therapy for autoimmune diseases. Unlike conventional immunosuppressive treatments, nanotechnology-based approaches can accurately modulate immune responses by targeting drugs or biological agents to specific cells and tissues, therefore minimizing systemic side effects. The transition from broad immunosuppressant medicines to precision therapeutics with immune-specific interventions would significantly improve patients’ quality of life and treatment results. The integration of advanced nanomedicine technology into pharmacy and immunology is expected to promote the discovery of novel diagnostics, enhance drug delivery systems, and perhaps provide disease-modifying therapies that improve immunological tolerance. Continuous multidisciplinary collaboration and clinical research are necessary to transform these major findings into inexpensive and practical medications, which have the potential to change treatments for autoimmune diseases.

Author Contributions

M.B. and J.M.A.E. conceptualized the review and supervised the overall direction of the manuscript. L.F.A., D.R. E.H, and S.B.A., contributed to the literature search and initial drafting. D.R. and E.H. were responsible for data extraction and synthesis. L.F.A. developed the figures and tables. R.A.A.Q. and D.K.C, T.A. and M.A.A.A.N. critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the author(s) used ChatGPT 4.0 in order to proofread the English language of the manuscript. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Consent for Publication

All authors have reviewed and consented to the publication of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Subramani, K. , et al., Introduction to nanotechnology, in Nanobiomaterials in clinical dentistry. 2019, Elsevier. p. 3-18.

- Sahu, M.K., R. Yadav, and S.P. Tiwari, Recent advances in nanotechnology. International Journal of Nanomaterials, Nanotechnology and Nanomedicine, 2023. 9(1): p. 015-023.

- Xia, Y. , Are we entering the nano era? 2014, Wiley Online Library. p. 12268-12271. [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, S. , et al., Autoimmune disorders–immunopathogenesis and potential therapies. Journal of Young Pharmacists, 2017. 9(1): p. 14.

- Viswanath, D. , Understanding autoimmune diseases-a review. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Science, 2013. 6(6): p. 08-15.

- O’Shea, J.J., A. Ma, and P. Lipsky, Cytokines and autoimmunity. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2002. 2(1): p. 37-45.

- Juarranz, Y. , Molecular and cellular basis of autoimmune diseases. 2021, MDPI. p. 474.

- Davidson, A. and B. Diamond, Autoimmune diseases. New England Journal of Medicine, 2001. 345(5): p. 340-350.

- Carballido, J.M. , et al., The emerging jamboree of transformative therapies for autoimmune diseases. Frontiers in Immunology, 2020. 11: p. 472.

- Desvaux, E. , et al., Model-based computational precision medicine to develop combination therapies for autoimmune diseases. Expert Review of Clinical Immunology, 2022. 18(1): p. 47-56.

- Chountoulesi, M. and C. Demetzos, Promising nanotechnology approaches in treatment of autoimmune diseases of central nervous system. Brain Sciences, 2020. 10(6): p. 338.

- Trombetta, A.C., M. Meroni, and M. Cutolo, Steroids and autoimmunity. Front Horm Res, 2017. 48: p. 121-32.

- Bach, J.-F. , Immunosuppressive therapy of autoimmune diseases. Trends in pharmacological sciences, 1993. 14(5): p. 213-216.

- Chandrashekara, S. , The treatment strategies of autoimmune disease may need a different approach from conventional protocol: a review. Indian journal of pharmacology, 2012. 44(6): p. 665-671.

- Rosman, Z., Y. Shoenfeld, and G. Zandman-Goddard, Biologic therapy for autoimmune diseases: an update. BMC medicine, 2013. 11: p. 1-12.

- Thatte, A.S. , et al., Emerging strategies for nanomedicine in autoimmunity. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 2024. 207: p. 115194.

- Yuan, F., G. M. Thiele, and D. Wang, Nanomedicine development for autoimmune diseases. Drug Development Research, 2011. 72(8): p. 703-716.

- Hess, K.L. , et al., Engineering immunological tolerance using quantum dots to tune the density of self--antigen display. Advanced functional materials, 2017. 27(22): p. 1700290.

- Froimchuk, E. , et al., Self-assembly as a molecular strategy to improve immunotherapy. Accounts of chemical research, 2020. 53(11): p. 2534-2545.

- Steinman, L. , Immune therapy for autoimmune diseases. Science, 2004. 305(5681): p. 212-216.

- Khurana, A. and D.C. Brennan, Current concepts of immunosuppression and side effects. Pathology of solid organ transplantation, 2010: p. 11-30.

- Yadav, K. , et al., Targeting autoimmune disorders through metal nanoformulation in overcoming the fences of conventional treatment approaches, in Translational autoimmunity. 2022, Elsevier. p. 361-393.

- Hoeppli, R.E. , et al., How antigen specificity directs regulatory T--cell function: self, foreign and engineered specificity. Hla, 2016. 88(1-2): p. 3-13.

- Lenders, V. , et al., Biomedical nanomaterials for immunological applications: ongoing research and clinical trials. Nanoscale Advances, 2020. 2(11): p. 5046-5089.

- Kinnear, C. , et al., Form follows function: nanoparticle shape and its implications for nanomedicine. Chemical reviews, 2017. 117(17): p. 11476-11521.

- Dai, C. , et al., Coffee-derived self-anti-inflammatory polymer as drug nanocarrier for enhanced rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Chinese Chemical Letters, 2025. 36(3): p. 109869.

- Park, J.-S. , et al., Methotrexate-loaded nanoparticles ameliorate experimental model of autoimmune arthritis by regulating the balance of interleukin-17-producing T cells and regulatory T cells. Journal of Translational Medicine, 2022. 20(1): p. 85.

- Janakiraman, K. , et al., Development of Methotrexate and Minocycline-Loaded Nanoparticles for the Effective Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. AAPS PharmSciTech, 2020. 21: p. 1-17.

- Fereig, S.A. , et al., Self-assembled tacrolimus-loaded lecithin-chitosan hybrid nanoparticles for in vivo management of psoriasis. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 2021. 608: p. 121114.

- Guo, D. , et al., Evaluation of controlled-release triamcinolone acetonide-loaded mPEG-PLGA nanoparticles in treating experimental autoimmune uveitis. Nanotechnology, 2019. 30(16): p. 165702.

- Melero, A. , et al., Targeted delivery of Cyclosporine A by polymeric nanocarriers improves the therapy of inflammatory bowel disease in a relevant mouse model. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, 2017. 119: p. 361-371.

- Li, Y. , et al., Polysaccharide mycophenolate-based nanoparticles for enhanced immunosuppression and treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Theranostics, 2021. 11(8): p. 3694.