1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria are a serious threat to public health, affecting the ability to treat infections and increasing morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs [

1,

2]. Moreover, the misuse and overuse of antibiotics has contributed to the acceleration of antimicrobial resistance worldwide [

3].

Due to the limited number of new antimicrobial agents, WHO published, since 2017, a priority list of novel antibiotics for the development of effective treatments against those pathogens considered critical such as carbapenem-resistant

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, carbapenem-resistant and ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae [

4].

Carbapenems belong to the beta-lactam antibiotics family and are used to provide broad-spectrum coverage against various types of bacteria [

5]. Over the past 30 years, the emergence of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae has been observed [

6], leading to a significant increase in the use of carbapenems to treat infections caused by these organisms [

7].

Unfortunately, this increased utilization of carbapenems has contributed to the development of resistance to these antibiotics in

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CRPA) and Enterobacterales (CRE) through various mechanisms such as OXA-48 carbapenemases, KPCs, New Delhi Metallo-β-lactamase-1 (NDM-1), IMP-1, and VIM-1 metallo-β-lactamases [

8,

9]. Additionally, resistance can occur through the loss of porins and up-regulation of efflux pumps [

10,

11].

Several studies have investigated the risk factors associated with the acquisition of infections caused by multidrug-resistant

P. aeruginosa and Enterobacterales. A study showed that the infection with CRE was associated with long-term hospitalization, major surgery, and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy [

12].

CAZ-AVI is a novel β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combination with activity against

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, except the ones carrying metallo-β-lactamases [

13].

CAZ-AVI could serve as an alternative treatment option in order to reduce the use of carbapenems, thus reducing the development of selective resistance observed with these antibiotics [

14].

Therefore, it is crucial to determine phenotypically the resistance profiles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates against CAZ-AVI and investigate genotypically the molecular mechanisms of resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

Bacterial isolates

A total of 394 P. aeruginosa, 90 E. coli and 84 K. pneumoniae isolates were delivered from the Pathology and Laboratory Medicine department at the American University of Beirut, Medical Center to the bacteriology and molecular microbiology laboratory at the American University of Beirut.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Antimicrobial susceptibly testing (AST) was performed by disc diffusion and broth microdilution against different antimicrobials from different antimicrobial classes, with a focus on ceftazidime-avibactam (CAZ-AVI), meropenem-vaborbactam (MEV) and imipenem-relebactam (IMR).

Disk Diffusion

For each isolate, a bacterial suspension equivalent to 0.5 MacFarland was prepared. Then it was subcultured on a round Mueller-Hinton agar plate, in all the directions, to ensure that the bacterial suspension covered all the plate using a sterile swab. The plate was left for around 10 minutes closed on the bench, followed by the addition of the tested antimicrobials. The plate was then incubated at 37 °C for 18-24 hours after which the zone of inhibition diameters was measured, and the results were interpreted according to the CLSI M100 guideline.

Broth microdilution

Serial dilution was performed with concentrations ranging from 512 µg/mL to 0.5 µg/mL and the plate was incubated at 37 °C for 18-24 hours. All the experiments were run in duplicates. The results were interpreted according to the CLSI M100 guideline. Control strain P. aeruginosa ATCC® 27853, E. coli ATCC® 25922 and K. pneumoniae ATCC® 13833 were used in parallel to monitor the MIC results.

Whole-Genome Sequencing

A total of 30 P. aeruginosa, 30 E. coli, and 30 K. pneumoniae were sequenced. To prepare whole-genome sequencing libraries, fresh cultures were grown on LB and MacConkey agar and genomic DNA was extracted using Quick-DNA™ Fungal/Bacterial Miniprep kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA), then DNA will be purified using the DNA Cleanup and Concentrator (Genomic DNA Clean & Concentrator™ kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Sequencing libraries were prepared using the Illumina DNA prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) and sequenced on Illumina MiSeq sequencer, 2 × 250 cycles.

Bioinformatics analysis

Reads quality control and trimming was done using FastQC and Trimmomatic (v.1.2.14) after which assembly of the genome was performed using Unicycler on Galaxy (

https://usegalaxy.org/).

Variant calling

Sequencing quality reports were generated for the raw FASTQ files using FastQC to check for low quality bases and presence of adapters. After that, the VariantDetective (PMID: 38366603) pipeline was used to call variants. Briefly, the pipeline aligns the raw reads to the reference genome pseudomonas_aeruginosa_pao1 and escherichia_coli_str_k_12_substr_mg1655_gca_000005845 downloaded from Ensembl using BWA (PMID: 19451168). Aligned reads are stored in sequence alignment map (SAM) files for each isolate. Then, consensus single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and short insertions and deletions (INDELs) are called using Freebayes (

https://arxiv.org/abs/1207.3907), GATK HaplotypeCaller (PMID: 20644199) and Clair3 (PMID: 38177392) tools using the SAM files generated from the previous step as input. The final output is a VCF file that contains the consensus variant calls. Ensembl-VEP (PMID: 27268795) was run to annotate the called variants and a tabulated form of the variants was generated using bcftools (PMID: 33590861) +split-vep plugin.

3. Results

3.1. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Results

Our results showed that 20 out of 84 K. pneumoniae isolates (24%) were multi-drug resistant, 52 (62%) were extensively drug resistant and 11 (13%) were pan drug resistant.

Moreover, 45 out of 90 E. coli isolates (50%) were multi-drug resistant, 42 (47%) were extensively drug resistant.

Furthermore, 81 out of 394 P. aeruginosa isolates (21%) were multi-drug resistant, 77 (20%) were extensively drug resistant and 1 (0.3%) were pan drug resistant.

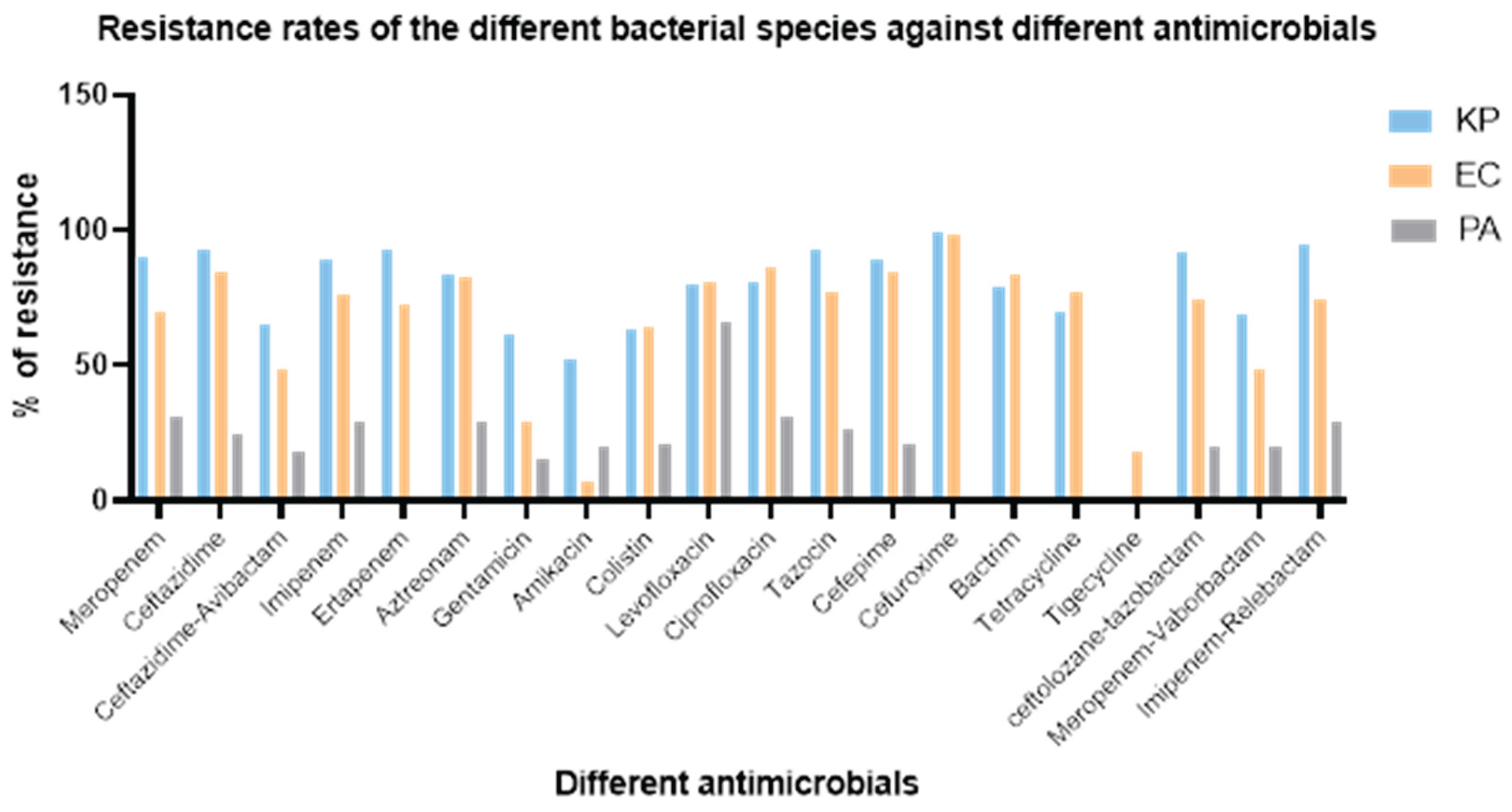

AST results showed varying resistance rates for the different bacterial species against different antimicrobials. The highest resistance rates observed for

K. pneumoniae and

E. coli were against cefuroxime (99% and 98% respectively) and for

P. aeruginosa was against levofloxacin (66%). On the other hand, the lowest resistance rates observed for

K. pneumoniae and

E. coli were against amikacin (52% and 7% respectively) and for

P. aeruginosa was against gentamicin (15%) (

Figure 1).

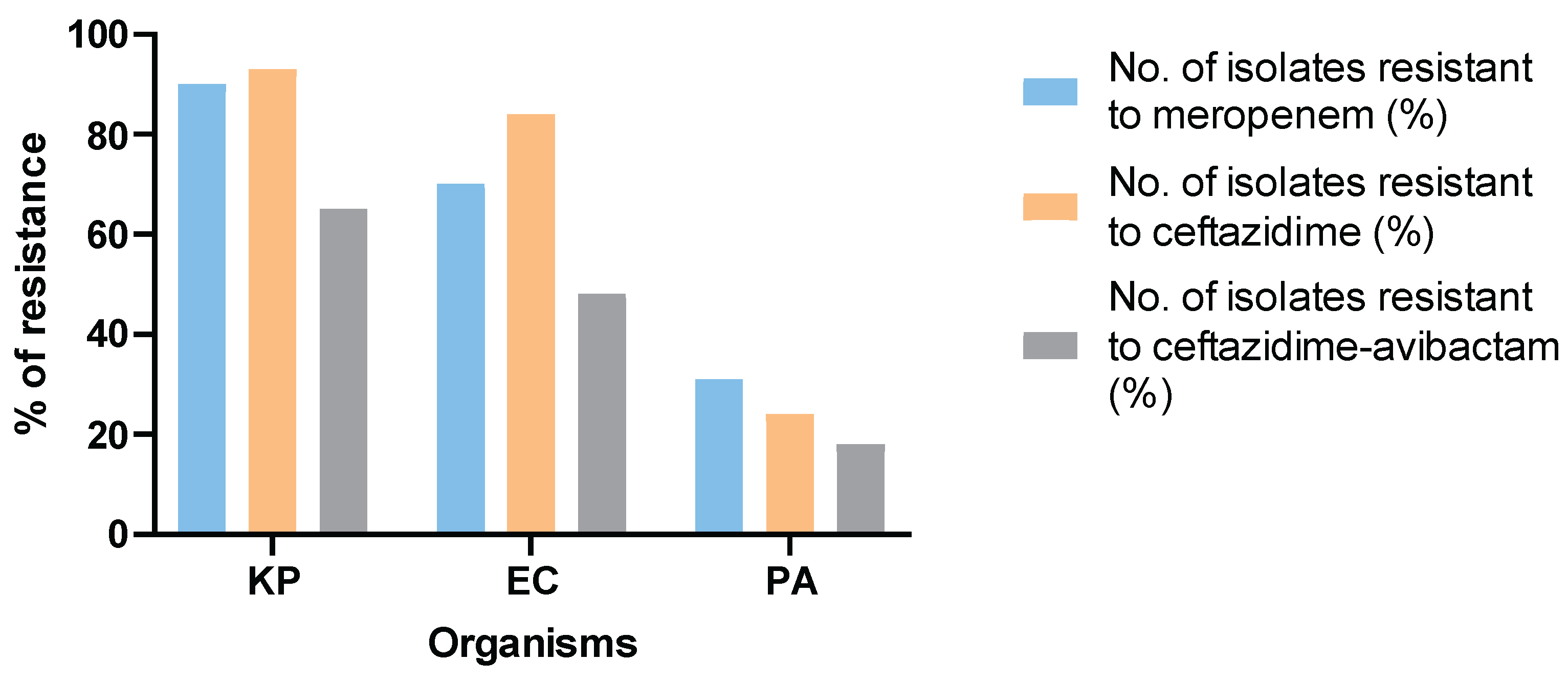

Furthermore, 90% of K. pneumoniae, 70% of E. coli and 31% of P. aeruginosa isolates were found to be resistant to meropenem. Whereas 65% of K. pneumoniae, 48% of E. coli and 18% of P. aeruginosa isolates were resistant to CAZ-AVI.

In addition, lower resistance rates against CAZ-AVI (65%, 48% and 18%) compared to ceftazidime (93%, 84% and 24%) were detected in

K. pneumoniae, E. coli and

P. aeruginosa isolates respectively (

Figure 2).

3.2. Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) Analysis

To investigate the molecular mechanism of resistance, WGS was conducted on 30 isolates from each bacterial species.

3.2.1. Sequence Types (STs)

Among the sequenced isolates, 13, 17 and 8 different STs were observed for each

K. pneumoniae, E. coli and

P. aeruginosa isolates, with ST383 (47%), ST648 (30%) and ST111 (50%) being the most frequent, respectively. Interestingly, 7% of

K. pneumoniae,

E. coli and 3% of

P. aeruginosa isolates were of unknown ST (

Figure 3).

3.2.2. Plasmids

K. pneumoniae isolates harbored 19 different plasmids with IncHI1B (pNDM-MAR) (63%) and IncFIB (pNDM-Mar) (47%) being the most frequent. Regarding E. coli isolates, 31 different plasmids were detected, among which IncFIA (60%), IncFIB (AP001918) (53%) and IncFII (43%) were the most commonly observed.

3.2.3. AMR Genes

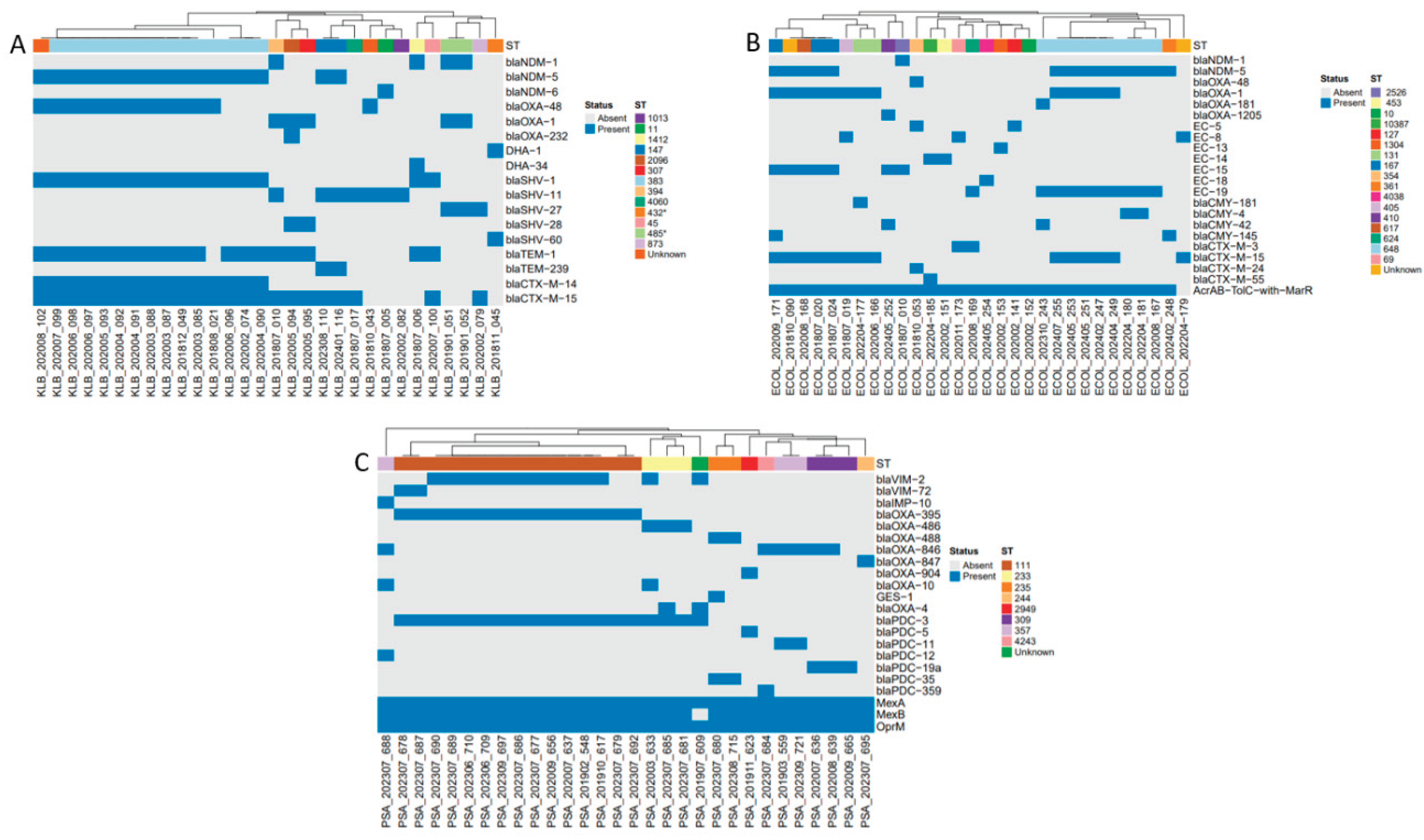

WGS analysis also shows that K. pneumoniae, E. coli and P. aeruginosa isolates encode numerous antimicrobial resistance determinants (97, 120 and 119, respectively).

The below heatmap (

Figure 4) visualizes the distribution of various beta-lactamase genes, efflux pump components, and porins across

K. pneumoniae,

E. coli, and

P. aeruginosa isolates, revealing their distinct genetic resistance landscapes and co-occurrence patterns with specific sequence types.

Across all three panels, the presence of a gene is indicated by a blue square, while its absence is shown in gray. The hierarchical clustering of isolates is based on their resistance gene profiles and sequence types, which provides insights into the epidemiological relationships and the co-selection of resistance mechanisms within these bacterial populations.

3.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Molecular Characterization of CAZ-AVI-Resistant P. aeruginosa and Enterobaterales

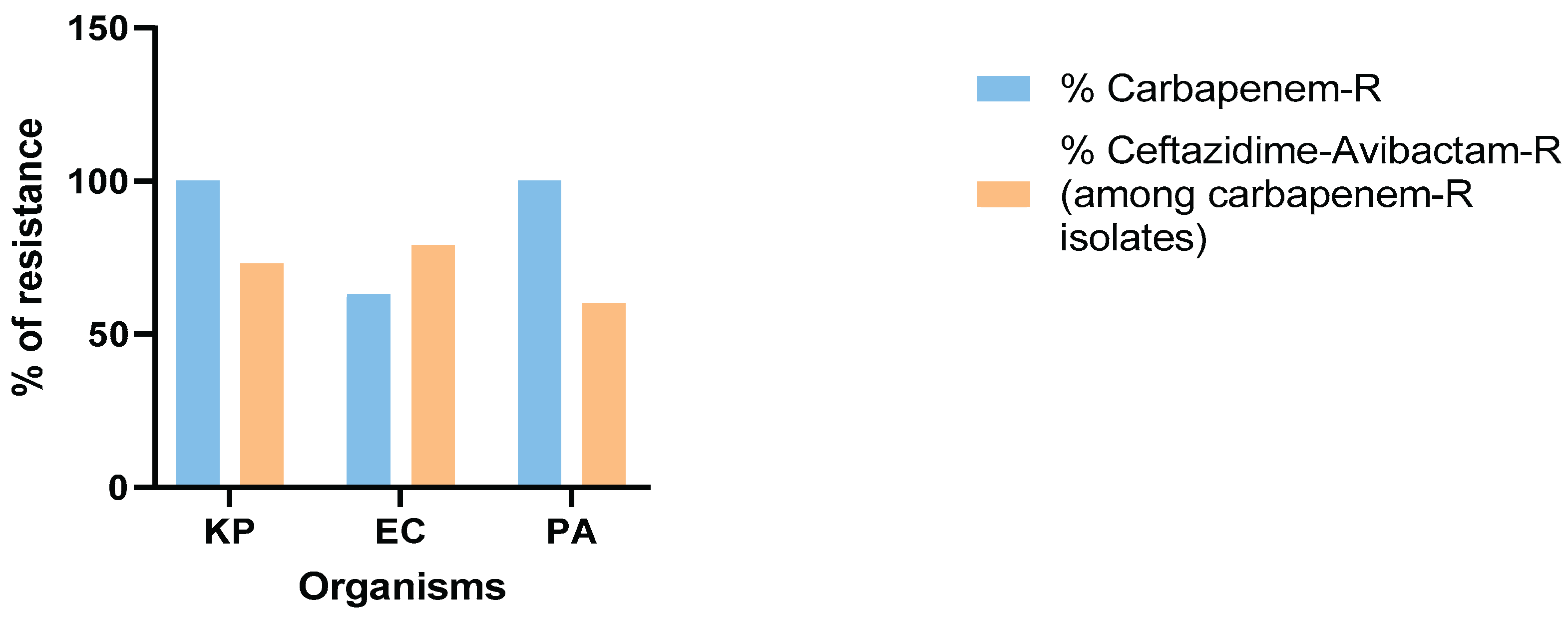

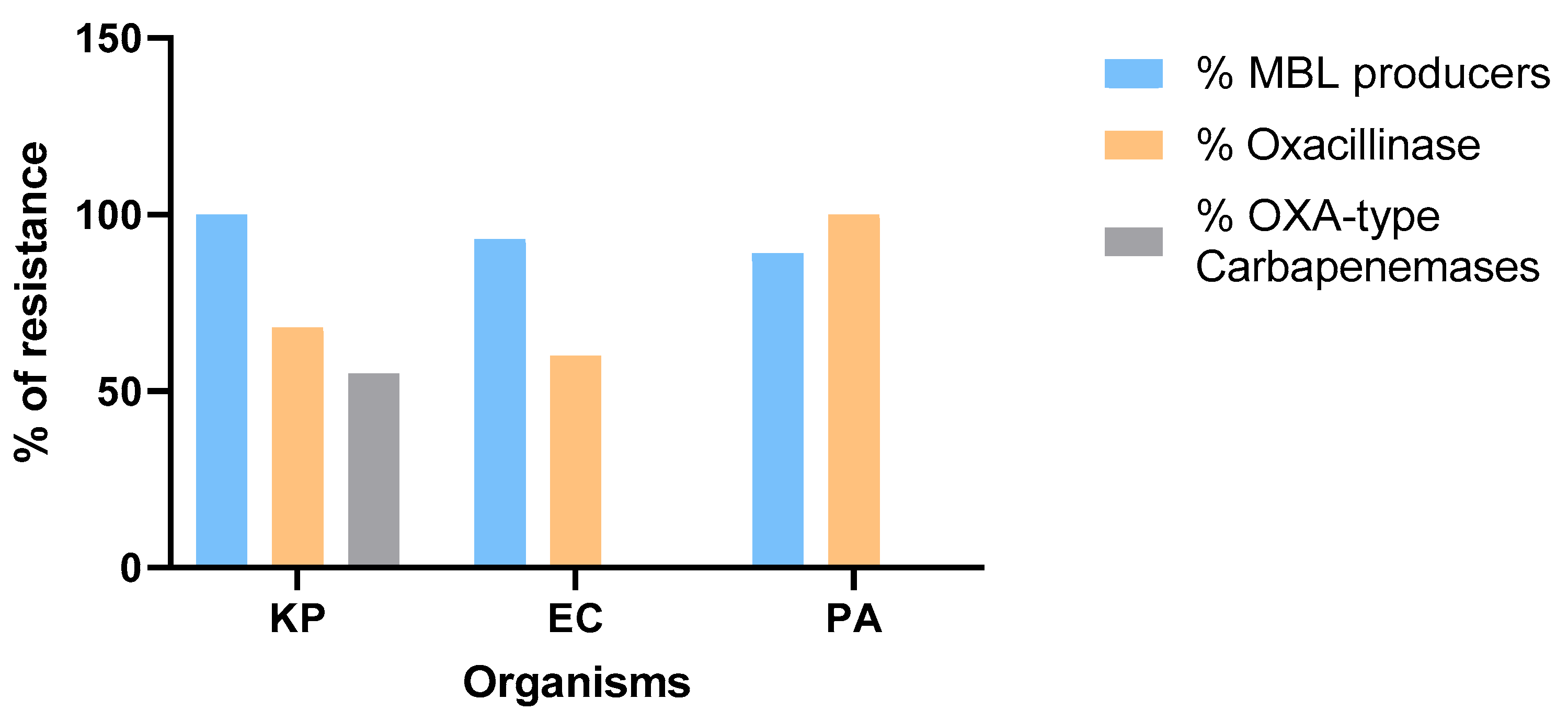

Moreover, the rates of resistance to carbapenem among sequenced isolates were as follows: 30 out of 30 (100%) for

K. pneumoniae, 19 out of 30 (63%) for

E. coli and 30 out of 30 (100%) for

P. aeruginosa isolates. Among those, 22 out of 30 (73%)

K. pneumoniae, 15 out of 19 (79%)

E. coli and 18 out of 30 (60%)

P. aeruginosa isolates were resistant to ceftazidime-avibactam (

Figure 5). Furthermore, the percentages of isolates harboring metallo-β-lactamase genes among sequenced carbapenem and CAZ-AVI-resistant isolates were as follows: 22 out of 22 for

K. pneumoniae (100%)

, 14 out of 15 for

E. coli (93%) and 16 out of 18 for

P. aeruginosa (89%). Additionally, 68% of

K. pneumoniae, 60% of

E. coli and 100% of

P. aeruginosa isolates were oxacillinase producers, of which 55% of

K. pneumoniae isolates encoded carbapenemases (

blaOXA-48,

blaOXA-232) (

Figure 6).

3.4. WGS Analysis of Non-MBL CAZ-AVI-Resistance Isolates and Associated Resistance Genes.

As no metallo-β-lactamase (MBL) genes were detected in the remaining two CAZ-AVI-resistant P. aeruginosa and E. coli isolates, resistance is likely driven by alternative mechanisms. To comprehensively elucidate these molecular bases of CAZ-AVI resistance in non-MBL-producing clinical isolates, we conducted detailed genetic analyses. This investigation focused on identifying mutations potentially leading to altered gene expression—either overexpression or repression—or amino acid substitutions that affect protein function. Specifically, for P. aeruginosa, we analyzed beta-lactamase-encoding gene regulators (blaAmpD, blaAmpR, blaAmpG), genes encoding the MexAB-OprM multidrug efflux pump regulators (mexR, nalC, nalD), and the dacB gene, which encodes penicillin-binding protein 4 (PBP4). However, for E. coli, we focused on beta-lactamase-encoding gene (blaAmpC), genes encoding the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump regulators (mexR), and gene encoding a major outer membrane porin ompC.

We found single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in

ampD (D183Y, G148A, R11L) and

ampR (D135N) for PSA_202307_695. As for PSA_202309_721 isolate, SNVs were detected in

mexR (V126E) and in

ampD (A96T, E68D); in

ampR, SNVs (M288R, S179T, E114A) and substitutions (RG282RE), all resulting in missense mutations. For the

E. coli isolate, we identified various amino acid alterations: in

ampC, SNVs (D367A, D304G, L257R, A157T), and substitutions (RP312HP, NE260ND, LK254MN, VQ250VR, PPA208PPP); in

marR, SNVs (G103S, Y137H), all resulting in missense mutations; in

ompC, substitutions (SLA295SVA, GAI216AAV, GNPSG175GSVSG) resulting in missense mutations, and highly disruptive INDELs (RG308TIAGRN, FTSGVT182MT) leading to frameshift mutations (

Table S1).

4. Discussion

In this study, we determined the phenotypic resistance profiles of K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa clinical isolates, particularly against CAZ-AVI, and investigated the underlying molecular mechanism of resistance through WGS. We analyzed the susceptibility to CAZ-AVI in 394 P. aeruginosa, 90 E. coli and 84 K. pneumoniae isolates collected between 2017 and 2024 in Lebanon. Finally, we performed WGS on 30 isolates from each species in order to uncover the antimicrobial resistance determinants associated with CAZ-AVI resistance.

Our findings show varied resistance rates against commonly used antimicrobials. In particular, 65% of

K. pneumoniae, 48% of

E. coli, and 18% of

P. aeruginosa were CAZ-AVI-resistant. Moreover, avibactam is a β-lactamase inhibitor effective against class A, C and D β-lactamases. When combined with ceftazidime, it prevents its hydrolysis by binding to the active site of serine-β-lactamases, thus restoring ceftazidime activity against resistant Gram-negative bacteria [

15]. This is reflected in our findings where the resistance rate to CAZ-AVI was lower than to ceftazidime alone in all 3 species (65 vs 93%, 48 vs 84% and 18 vs 24%, respectively) highlighting the effectiveness of avibactam in restoring ceftazidime antibacterial activity [

16].

Notably, a significant proportion of sequenced isolates exhibited carbapenem resistance: 100% of

K. pneumoniae, 63% of E. coli, and 100% of

P. aeruginosa. Among these, CAZ-AVI resistance rates were 73%, 79%, and 60%, respectively, underscoring concerns about CAZ-AVI’s effectiveness against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria and emphasizing the urgent need for novel antimicrobials [

17,

18].

Moreover, using WGS, we uncovered the molecular mechanisms of resistance of these isolates by revealing their arsenals of antimicrobial resistance determinants. In Enterobacterales, the predominant mechanism associated with CAZ-AVI resistance was the presence of metallo-β-lactamase (MBL)-encoding genes, particularly

blaNDM variants. All 22 CAZ-AVI-resistant

K. pneumoniae (100%) and 14 out of 15 CAZ-AVI-resistant

E. coli isolates (93%) harbored

blaNDM genes, which aligns with previously reported data indicating that MBL production is the leading cause of CAZ-AVI resistance [

19]. Among CAZ-AVI-resistant

P. aeruginosa isolates, 89% were found to be MBL-producers, particularly

blaVIM and

blaIMP variants, which supports previous findings that the presence of MBLs in

P. aeruginosa is a major contributor to CAZ-AVI resistance [

20].

As no MBL genes were detected in the remaining CAZ-AVI-resistant

P. aeruginosa and

E. coli isolates, a detailed genomic analysis was conducted, revealing that CAZ-AVI resistance is multifactorial and attributed to other mechanisms. In

P. aeruginosa isolates, resistance is likely driven by mutations in

ampD and

ampR, leading to AmpC hyperproduction [

21], and in

mexR, causing overexpression of the MexAB-OprM efflux pump, which slightly raises the MIC of CAZ-AVI [

22,

23,

24]. For the

E. coli isolate, resistance is primarily due to

ompC frameshift INDELs severely reducing outer membrane permeability, a critical factor given CAZ-AVI’s reliance on passive diffusion for cellular entry [

25]. Additionally,

marR mutations enhance AcrAB-TolC efflux, and numerous

ampC substitutions potentially alter beta-lactamase activity. These combined chromosomal alterations provide a robust mechanism for evading CAZ-AVI activity [

26].

Oxacillinase genes were also detected in 68% of CR-

K. pneumoniae, 60% of CR-

E. coli, and 100% of CRPA isolates. Although oxacillinases generally have a limited impact on CAZ-AVI activity, a subset of these genes encodes carbapenemases such as

blaOXA-48 and

blaOXA-232, which are known to reduce susceptibility to CAZ-AVI, especially when occurring simultaneously with porin loss, efflux pump overexpression or additional resistance-conferring elements [

27].

Our WGS results demonstrate a significant clonal diversity in addition to high numbers of AMR genes and plasmids. The most prominent STs identified were ST383 in

K. pneumoniae, ST648 in

E. coli, and ST111 in

P. aeruginosa, known for their role in the global spread of multidrug resistance [

28,

29,

30]. Moreover, the variety and high prevalence of AMR genes observed across our isolates highlights an alarming layered complexity and redundancy of resistance mechanisms, prompting urgent improvement of surveillance and control strategies on the national level. Furthermore, the presence of multiple plasmids, such as IncHI1B(pNDM-MAR) and IncFIB(pNDM-Mar) in

K. pneumoniae, and IncFIA and IncFIB (AP001918) in

E. coli suggest a high potential for horizontal gene transfer leading to the spread of resistance, which calls for immediate cooperation on national and regional levels to contain this dissemination [

31].

Overall, the concordance between our genotypic and phenotypic data in Enterobacterales highlights NDM-type MBL production as the primary molecular etiology of CAZ-AVI resistance [

32]. In contrast, we suggest that

P. aeruginosa presents a more complex resistance profile in the absence of MBLs, where other resistance mechanisms, such as efflux pump overexpression and AmpC deregulation, potentially play a significant role in conferring CAZ-AVI resistance [

17,

33]. Nonetheless, the high frequency of CAZ-AVI resistance among isolates carrying MBLs and carbapenemases reaffirms the need for routine genotypic screening alongside phenotypic testing, especially in clinical settings where CAZ-AVI is considered a frontline treatment.

In conclusion, our findings reveal alarmingly high levels of resistance to CAZ-AVI among carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae, E. coli and P. aeruginosa isolates. The widespread presence of MBLs, oxacillinases, and transferable resistance plasmids highlights the dynamic and multifactorial nature of resistance. These results emphasize the critical importance of molecular diagnostics, antimicrobial stewardship, and collaborative surveillance to guide effective therapeutic strategies and mitigate the spread of CAZ-AVI resistance in high-burden settings. In the short term, combining other antimicrobial agents such as aztreonam with CAZ-AVI may offer a viable option against resistant isolates until novel antimicrobials are developed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, ZK, AAF and GM; Methodology, JRG, SB; Software, AK; Validation, JRG, SB, HH, AS, ZJ and FER; Formal Analysis, JRG and AK; Investigation, JRG, SB, HH, AS, ZJ and FER; Resources, GA; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, JRG; Writing—Review and Editing, SB, HH, AS, ZJ, FER, ZK, AAF and GM; Visualization, JRG; Supervision, ZK, AAF and GM; Project Administration, ZK, AAF and GM; Funding Acquisition, ZK. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| CRPA |

Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| CRE |

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales |

| CAZ-AVI |

Ceftazidime-Avibactam |

| PA |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| EC |

Escherichia coli |

| KP |

Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| AST |

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| WGS |

Whole-Genome Sequencing |

| MBLs |

Metallo-β-lactamases |

| CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| ESBL |

Extended-Spectrum Beta-lactamase |

| NDM-1 |

New Delhi Metallo-β-lactamase-1 |

| OXA-48 |

Oxacillinase-48 |

| KPC |

Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase |

| IMP-1 |

Imipenemase-1 |

| VIM-1 |

Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase-1 |

| OmpC |

Outer membrane protein C |

| MEV |

Meropenem-Vaborbactam |

| IMR |

Imipenem-Relebactam |

| CARD |

Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database |

| CGE |

Center of Genomic Epidemiology |

| MLST |

Multilocus Sequence Typing |

| ST |

Sequence Type |

| SNPs |

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms |

| INDELs |

Short Insertions and Deletions |

| PBP4 |

Penicillin-Binding Protein 4 |

| AMR |

Antimicrobial Resistance |

References

- C. J. L. Murray et al., “Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis,” The Lancet, vol. 399, no. 10325, pp. 629–655, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Chinemerem Nwobodo et al., “Antibiotic resistance: The challenges and some emerging strategies for tackling a global menace,” Clinical Laboratory Analysis, vol. 36, no. 9, Sept. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Llor and L. Bjerrum, “Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem,” Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 229–241, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Al-Tawfiq et al., “Antibiotics in the pipeline: a literature review (2017–2020),” Infection, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 553–564, June 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Papp-Wallace, A. Endimiani, M. A. Taracila, and R. A. Bonomo, “Carbapenems: Past, Present, and Future,” Antimicrob Agents Chemother, vol. 55, no. 11, pp. 4943–4960, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- X. Qin et al., “Prevalence and Mechanisms of Broad-Spectrum β-Lactam Resistance inEnterobacteriaceae: a Children’s Hospital Experience,” Antimicrob Agents Chemother, vol. 52, no. 11, pp. 3909–3914, Nov. 2008. [CrossRef]

- R. I. El-Herte, S. S. Kanj, G. M. Matar, and G. F. Araj, “The threat of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Lebanon: An update on the regional and local epidemiology,” Journal of Infection and Public Health, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 233–243, June 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. G. Moloughney, J. D. Thomas, and J. H. Toney, “Novel IMP-1 metallo-Î2-lactamase inhibitors can reverse meropenem resistance inEscherichia coliexpressing IMP-1,” FEMS Microbiology Letters, vol. 243, no. 1, pp. 65–71, Feb. 2005. [CrossRef]

- C. Urban et al., “Carbapenem-ResistantEscherichia coliHarboringKlebsiella pneumoniaeCarbapenemase β-Lactamases Associated with Long-Term Care Facilities,” CLIN INFECT DIS, vol. 46, no. 11, pp. e127–e130, June 2008. [CrossRef]

- P. Nordmann, L. Dortet, and L. Poirel, “Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: here is the storm!,” Trends in Molecular Medicine, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 263–272, May 2012. [CrossRef]

- L. Poirel, C. Héritier, V. Tolün, and P. Nordmann, “Emergence of Oxacillinase-Mediated Resistance to Imipenem inKlebsiella pneumoniae,” Antimicrob Agents Chemother, vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 15–22, Jan. 2004. [CrossRef]

- E. Cendejas, R. Gómez-Gil, P. Gómez-Sánchez, and J. Mingorance, “Detection and characterization of Enterobacteriaceae producing metallo-β-lactamases in a tertiary-care hospital in Spain,” Clinical Microbiology and Infection, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 181–183, Feb. 2010. [CrossRef]

- A. Torres et al., “Ceftazidime-avibactam versus meropenem in nosocomial pneumonia, including ventilator-associated pneumonia (REPROVE): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 non-inferiority trial,” The Lancet Infectious Diseases, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 285–295, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Bassetti, D. R. Giacobbe, C. Robba, P. Pelosi, and A. Vena, “Treatment of extended-spectrum β-lactamases infections: what is the current role of new β-lactams/β-lactamase inhibitors?,” Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases, vol. 33, no. 6, pp. 474–481, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Falcone and D. Paterson, “Spotlight on ceftazidime/avibactam: a new option for MDR Gram-negative infections,” J. Antimicrob. Chemother., vol. 71, no. 10, pp. 2713–2722, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- W. W. Nichols, P. A. Bradford, S. D. Lahiri, and G. G. Stone, “The primary pharmacology of ceftazidime/avibactam: in vitro translational biology,” Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, vol. 77, no. 9, pp. 2321–2340, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Mehwish and I. Iftikhar, “EMERGENCE OF CEFTAZIDIME-AVIBACTAM RESISTANCE IN ENTERO-BACTERALES AND PSEUDOMONAS AERUGINOSA,” Pak J Pathol, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 113–117, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhen, H. Wang, and S. Feng, “Update of clinical application in ceftazidime–avibactam for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria infections,” Infection, vol. 50, no. 6, pp. 1409–1423, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Sobh et al., “Molecular characterization of carbapenem and ceftazidime-avibactam-resistant Enterobacterales and horizontal spread of blaNDM-5 gene at a Lebanese medical center,” Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol., vol. 14, June 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. T. Al-Alaq, S. S. Mahmood, N. S. K. AL-Khafaji, H. O. M. Al-Dahmoshi, and M. Memariani, “Investigation of blaIMP-1, blaVIM-1, blaOXA-48 and blaNDM-1 carbapenemase encoding genes among MBL-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa,” JANS, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 740–745, Sept. 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. Caille et al., “Structural and Functional Characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Global Regulator AmpR,” J Bacteriol, vol. 196, no. 22, pp. 3890–3902, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- G. Torrens et al., “Activity of Ceftazidime-Avibactam against Clinical and Isogenic Laboratory Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolates Expressing Combinations of Most Relevant β-Lactam Resistance Mechanisms,” Antimicrob Agents Chemother, vol. 60, no. 10, pp. 6407–6410, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. Babouee Flury et al., “Multifactorial resistance mechanisms associated with resistance to ceftazidime-avibactam in clinical Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Switzerland,” Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol., vol. 13, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Castanheira, T. B. Doyle, C. J. Smith, R. E. Mendes, and H. S. Sader, “Combination of MexAB-OprM overexpression and mutations in efflux regulators, PBPs and chaperone proteins is responsible for ceftazidime/avibactam resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates from US hospitals,” Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, vol. 74, no. 9, pp. 2588–2595, Sept. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Xiong et al., “Molecular mechanisms underlying bacterial resistance to ceftazidime/avibactam,” WIREs Mechanisms of Disease, vol. 14, no. 6, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. L. Smith, S. Fernando, and M. D. King, “Escherichia coli resistance mechanism AcrAB-TolC efflux pump interactions with commonly used antibiotics: a molecular dynamics study,” Sci Rep, vol. 14, no. 1, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Palwe, Y. D. Bakthavatchalam, K. Khobragadea, A. S. Kharat, K. Walia, and B. Veeraraghavan, “In-Vitro Selection of Ceftazidime/Avibactam Resistance in OXA-48-Like-Expressing Klebsiella pneumoniae: In-Vitro and In-Vivo Fitness, Genetic Basis and Activities of β-Lactam Plus Novel β-Lactamase Inhibitor or β-Lactam Enhancer Combinations,” Antibiotics, vol. 10, no. 11, p. 1318, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Guo et al., “Nosocomial Outbreak of OXA-48-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Chinese Hospital: Clonal Transmission of ST147 and ST383,” PLoS ONE, vol. 11, no. 8, p. e0160754, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, C. H. Seward, Z. Wu, H. Ye, and Y. Feng, “Genomic insights into the ESBL and MCR-1-producing ST648 Escherichia coli with multi-drug resistance,” Science Bulletin, vol. 61, no. 11, pp. 875–878, June 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Oliver, X. Mulet, C. López-Causapé, and C. Juan, “The increasing threat of Pseudomonas aeruginosa high-risk clones,” Drug Resistance Updates, vol. 21–22, pp. 41–59, July 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Schjorring, C. Struve, and K. A. Krogfelt, “Transfer of antimicrobial resistance plasmids from Klebsiella pneumoniae to Escherichia coli in the mouse intestine,” Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, vol. 62, no. 5, pp. 1086–1093, July 2008. [CrossRef]

- F. Uddin et al., “NDM Production as a Dominant Feature in Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Isolates from a Tertiary Care Hospital,” Antibiotics, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 48, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Mojica et al., “Molecular Mechanisms of Resistance to Ceftazidime/Avibactam in Clinical Isolates of Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Latin American Hospitals”.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).