Submitted:

24 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

2.2.1. Patient Tissue Slides

2.2.2. Generation of Patient-Derived Cell Block

2.2.3. Antibody Staining of Patient Tissue and Cell Block Slices

2.2.4. Quantification of Antibody Staining

2.3. Flow Cytometry

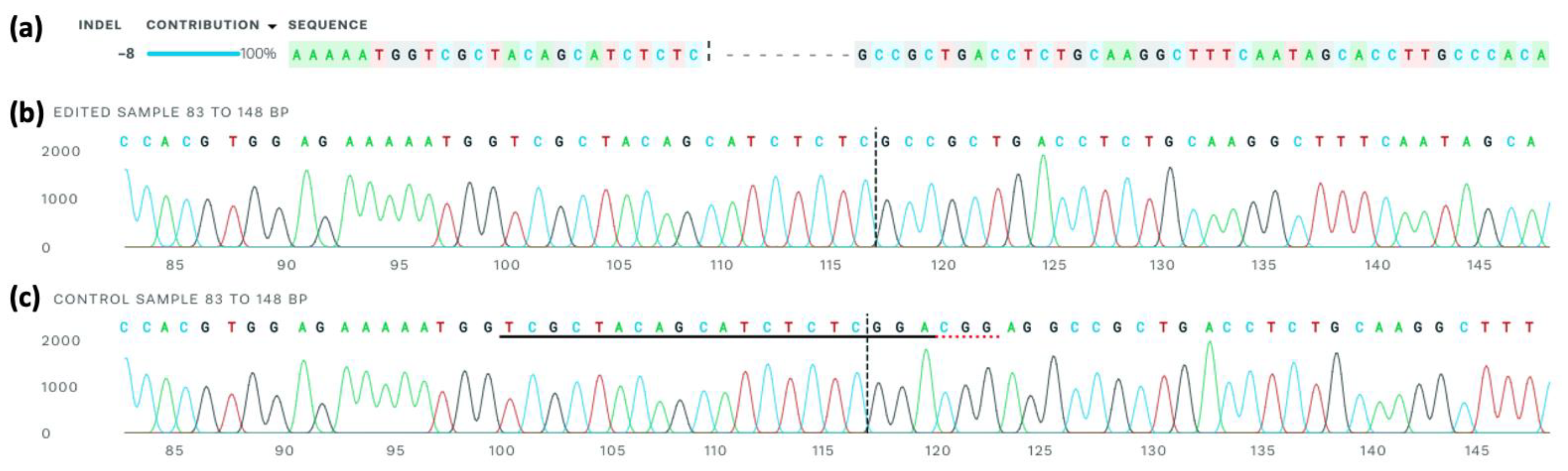

2.4. CD44 Knockout

2.4.1. Lipofectamine CRISPR Transfection

2.4.2. Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting

2.5. qRT-PCR

2.5.1. RNA Extraction

2.5.2. cDNA Synthesis

2.5.3. RT-PCR

2.6. Sanger Sequencing

2.6.1. DNA Extraction

2.6.2. Primer Design

2.6.3. Polymerase Chain Reaction

2.6.4. PCR Purification

2.6.5. Sanger Sequencing and Analysis

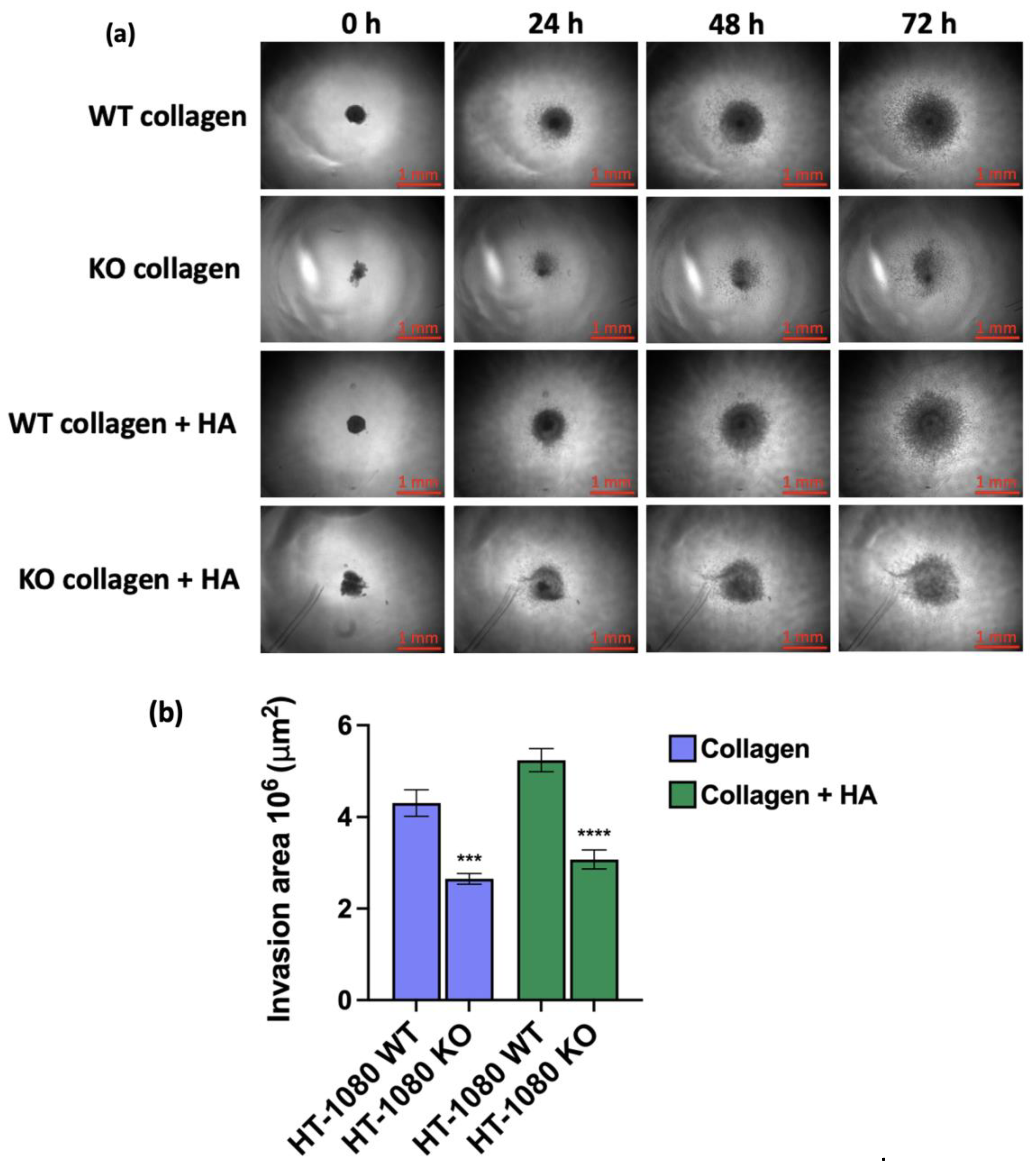

2.7. Collagen Spheroid Invasion Assay

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| ACT BSA |

Atypical cartilaginous tumour Bovine serum albumin |

| Cas9 | CRISPR associated protein 9 |

| CD44 | Cluster of differentiation 44 |

| cDNA | Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid |

| CRISPR | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| DAB | 3,3’-diaminobenzidine |

| DI | De-ionised |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EFS | Event-free survival |

| EMT | Epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| FACS | Fluorescence activated cell sorting |

| FITC | Fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| KO | Knockout |

| MEM | Minimum Essential Medium |

| MMP-9 | Matrix metalloproteinase-9 |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| RhoA | Ras homolog family member A |

| ROCK | Rho-associated coiled coil containing protein kinase |

| RPMI | Roswell Park Memorial Institute |

| sgRNA | Single guide ribonucleic acid |

| TBS | Tris-buffered saline |

| ULA | Ultra-low attachment |

| WT | Wild type |

References

- Aran, V.; Devalle, S.; Meohas, W.; Heringer, M.; Cunha Caruso, A.; Pinheiro Aguiar, D.; Leite Duarte, M.E.; Moura Neto, V. Osteosarcoma, Chondrosarcoma and Ewing Sarcoma: Clinical Aspects, Biomarker Discovery and Liquid Biopsy. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2021, 162, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Lee, S.K. Classification of Chondrosarcoma: From Characteristic to Challenging Imaging Findings. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-J.; Cho, K.-J.; Ayala, A.G.; Ro, J.Y. Chondrosarcoma: With Updates on Molecular Genetics. Sarcoma 2011, 2011, 405437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, J.; McTiernan, A.; Cooper, N.; Wong, Y.K.; Francis, M.; Vernon, S.; Strauss, S.J. Incidence and Survival of Malignant Bone Sarcomas in England 1979-2007. Int J Cancer 2012, 131, E508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Sun, Y.; Han, X.; Zhang, J. The Clinicopathological Characteristics and Prognosis of Young Patients with Chondrosarcoma of Bone. Front. Surg. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierselhuis, E.F.; Gerbers, J.G.; Ploegmakers, J.J.W.; Stevens, M.; Suurmeijer, A.J.H.; Jutte, P.C. Local Treatment with Adjuvant Therapy for Central Atypical Cartilaginous Tumors in the Long Bones: Analysis of Outcome and Complications in One Hundred and Eight Patients with a Minimum Follow-up of Two Years. JBJS 2016, 98, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehner, C.A.; Maloney, N.; Amini, B.; Jennings, J.W.; McDonald, D.J.; Wang, W.-L.; Chrisinger, J.S.A. Dedifferentiated Chondrosarcoma with Minimal or Small Dedifferentiated Component. Modern Pathology 2022, 35, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, K.L.; Raymond, A.K. Low-Grade/Dedifferentiated/High-Grade Chondrosarcoma: A Case of Histological and Biological Progression. The Iowa Orthopaedic Journal 2002, 22, 75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sekito, S.; Kato, M.; Nishikawa, K.; Yoshio, Y.; Kanai, M.; Kanda, H.; Arima, K.; Sugimura, Y. Successfully Treated Lung and Renal Metastases from Primary Chondrosarcoma of the Scapula with Radiofrequency Ablation and Surgical Resection. Case Reports in Oncological Medicine 2019, 2019, 6475356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, J.D.; Laitinen, M.K.; Parry, M.C.; Sumathi, V.; Grimer, R.J.; Jeys, L.M. The Role of Surgical Margins in Chondrosarcoma. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 2018, 44, 1412–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirbel, R.J.; Schulte, M.; Maier, B.; Koschnik, M.; Mutschler, W.E. Chondrosarcoma of the Pelvis: Oncologic and Functional Outcome. Sarcoma 2000, 4, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italiano, A.; Mir, O.; Cioffi, A.; Palmerini, E.; Piperno-Neumann, S.; Perrin, C.; Chaigneau, L.; Penel, N.; Duffaud, F.; Kurtz, J.E.; et al. Advanced Chondrosarcomas: Role of Chemotherapy and Survival. Ann Oncol 2013, 24, 2916–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, Y.; Ingola, M.; Briaire-de Bruijn, I.H.; Kruisselbrink, A.B.; Venneker, S.; Palubeckaite, I.; Heijs, B.P.A.M.; Cleton-Jansen, A.-M.; Haas, R.L.M.; Bovée, J.V.M.G. Radiotherapy Resistance in Chondrosarcoma Cells; a Possible Correlation with Alterations in Cell Cycle Related Genes. Clinical Sarcoma Research 2019, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.N.; Chandavarkar, V.; Sharma, R.; Bhargava, D. Structure, Function and Role of CD44 in Neoplasia. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2019, 23, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhao, S.; Karnad, A.; Freeman, J.W. The Biology and Role of CD44 in Cancer Progression: Therapeutic Implications. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2018, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodison, S.; Urquidi, V.; Tarin, D. CD44 Cell Adhesion Molecules. Mol Pathol 1999, 52, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirillo, N. The Hyaluronan/CD44 Axis: A Double-Edged Sword in Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 15812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon, L. Matrix Hyaluronan-Activated CD44 Signaling Promotes Keratinocyte Activities and Improves Abnormal Epidermal Functions. The American journal of pathology 2014, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitulescu, G.M.; Van De Venter, M.; Nitulescu, G.; Ungurianu, A.; Juzenas, P.; Peng, Q.; Olaru, O.T.; Grădinaru, D.; Tsatsakis, A.; Tsoukalas, D.; et al. The Akt Pathway in Oncology Therapy and beyond (Review). International Journal of Oncology 2018, 53, 2319–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rekabi, Z.; Fura, A.M.; Juhlin, I.; Yassin, A.; Popowics, T.E.; Sniadecki, N.J. Hyaluronan-CD44 Interactions Mediate Contractility and Migration in Periodontal Ligament Cells. Cell Adh Migr 2019, 13, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martincuks, A.; Li, P.-C.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.-J.; Yu, H.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, L. CD44 in Ovarian Cancer Progression and Therapy Resistance—A Critical Role for STAT3. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 589601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdoli Shadbad, M.; Hosseinkhani, N.; Asadzadeh, Z.; Derakhshani, A.; Karim Ahangar, N.; Hemmat, N.; Lotfinejad, P.; Brunetti, O.; Silvestris, N.; Baradaran, B. A Systematic Review to Clarify the Prognostic Values of CD44 and CD44+CD24- Phenotype in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Patients: Lessons Learned and The Road Ahead. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaya, R.; Yamaguchi, S.; Ishi, Y.; Okamoto, M.; Echizenya, S.; Motegi, H.; Fujima, N.; Fujimura, M. Increased CD44 Expression in Primary Meningioma: Its Clinical Significance and Association with Peritumoral Brain Edema. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, M.; Christofori, G. EMT, the Cytoskeleton, and Cancer Cell Invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2009, 28, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.L.; Reinke, L.M.; Damerow, M.S.; Perez, D.; Chodosh, L.A.; Yang, J.; Cheng, C. CD44 Splice Isoform Switching in Human and Mouse Epithelium Is Essential for Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Breast Cancer Progression. J Clin Invest 2011, 121, 1064–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, N.; Yano, H.; Nishida, T.; Kamura, T.; Kojiro, M. Angiogenesis in Cancer. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2006, 2, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Fu, C.; Zhang, Q.; He, C.; Zhang, F.; Wei, Q. The Role of CD44 in Pathological Angiogenesis. FASEB J 2020, 34, 13125–13139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, C.; Alsaleem, M.; Orah, N.; Narasimha, P.L.; Miligy, I.M.; Kurozumi, S.; Ellis, I.O.; Mongan, N.P.; Green, A.R.; Rakha, E.A. Elevated MMP9 Expression in Breast Cancer Is a Predictor of Shorter Patient Survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2020, 182, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano-González, P.A.; Rivera-Ramírez, O.; Montaño, L.F.; Rendón-Huerta, E.P. Proteolytic Processing of CD44 and Its Implications in Cancer. Stem Cells International 2021, 2021, 6667735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menke-van der Houven van Oordt, C.W.; Gomez-Roca, C.; van Herpen, C.; Coveler, A.L.; Mahalingam, D.; Verheul, H.M.W.; van der Graaf, W.T.A.; Christen, R.; Rüttinger, D.; Weigand, S.; et al. First-in-Human Phase I Clinical Trial of RG7356, an Anti-CD44 Humanized Antibody, in Patients with Advanced, CD44-Expressing Solid Tumors. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 80046–80058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauw, Y.W.S.; Huisman, M.C.; Nayak, T.K.; Vugts, D.J.; Christen, R.; Naegelen, V.M.; Ruettinger, D.; Heil, F.; Lammertsma, A.A.; Verheul, H.M.W.; et al. Assessment of Target-Mediated Uptake with Immuno-PET: Analysis of a Phase I Clinical Trial with an Anti-CD44 Antibody. EJNMMI Res 2018, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundhill, E.A.; Jabri, S.; Burchill, S.A. ABCG1 and Pgp Identify Drug Resistant, Self-Renewing Osteosarcoma Cells. Cancer Lett 2019, 453, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankhead, P.; Loughrey, M.B.; Fernández, J.A.; Dombrowski, Y.; McArt, D.G.; Dunne, P.D.; McQuaid, S.; Gray, R.T.; Murray, L.J.; Coleman, H.G.; et al. QuPath: Open Source Software for Digital Pathology Image Analysis. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 16878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Z.; Luo, D.; Wang, S.; Rong, R.; Evers, B.M.; Jia, L.; Fang, Y.; Daoud, E.V.; Yang, S.; Gu, Z.; et al. Deep Learning–Based H-Score Quantification of Immunohistochemistry-Stained Images. Modern Pathology 2024, 37, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cao, H.; Luo, H.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Z.; Dai, Z.; Wu, W.; Liu, G.; Xie, Z.; Cheng, Q.; et al. RUNX1/CD44 Axis Regulates the Proliferation, Migration, and Immunotherapy of Gliomas: A Single-Cell Sequencing Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homo Sapiens CD44 Molecule (IN Blood Group) (CD44), RefSeqGene (LRG_815) on Chromosome 11. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NG_008937.1 (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Ye, J.; Coulouris, G.; Zaretskaya, I.; Cutcutache, I.; Rozen, S.; Madden, T.L. Primer-BLAST: A Tool to Design Target-Specific Primers for Polymerase Chain Reaction. BMC Bioinformatics 2012, 13, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-H.; Cheng, Y.-H.; Chuang, L.-Y.; Chang, H.-W. Specific PCR Product Primer Design Using Memetic Algorithm. Biotechnology Progress 2009, 25, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conant, D.; Hsiau, T.; Rossi, N.; Oki, J.; Maures, T.; Waite, K.; Yang, J.; Joshi, S.; Kelso, R.; Holden, K.; et al. Inference of CRISPR Edits from Sanger Trace Data. CRISPR J 2022, 5, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, S.J.; Coyle, B. Establishing an In Vitro 3D Spheroid Model to Study Medulloblastoma Drug Response and Tumor Dissemination. Current Protocols 2022, 2, e357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazendam, A.; Popovic, S.; Parasu, N.; Ghert, M. Chondrosarcoma: A Clinical Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wu, K.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Q.; Han, N.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, L.; Wu, G.S.; Wu, K. CD44 Correlates with Clinicopathological Characteristics and Is Upregulated by EGFR in Breast Cancer. Int J Oncol 2016, 49, 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyse, T.J.; Malcherczyk, D.; Moll, R.; Timmesfeld, N.; Wapelhorst, J.; Fuchs-Winkelmann, S.; Paletta, J.R.J.; Schofer, M.D. CD44: Survival and Metastasis in Chondrosarcoma. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2010, 18, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeister, V.; Agarwal, S.; Bordeaux, J.; Camp, R.L.; Rimm, D.L. In Situ Identification of Putative Cancer Stem Cells by Multiplexing ALDH1, CD44, and Cytokeratin Identifies Breast Cancer Patients with Poor Prognosis. Am J Pathol 2010, 176, 2131–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combaret, V.; Gross, N.; Lasset, C.; Frappaz, D.; Beretta-Brognara, C.; Philip, T.; Beck, D.; Favrot, M.C. Clinical Relevance of CD44 Cell Surface Expression and MYCN Gene Amplification in Neuroblastoma. European Journal of Cancer 1997, 33, 2101–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.M.; Rakoczy, K.; Hart, J.; Jones, K.B.; Groundland, J.S. Presenting Features and Overall Survival of Chondrosarcoma of the Pelvis. Cancer Treatment and Research Communications 2022, 30, 100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlemsani, C.; Larousserie, F.; Percin, S.D.; Audard, V.; Hadjadj, D.; Chen, J.; Biau, D.; Anract, P.; Terris, B.; Goldwasser, F.; et al. Biology and Management of High-Grade Chondrosarcoma: An Update on Targets and Treatment Options. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, A.M.; Pan, Y.K.; Chandrapalan, T.; Kwong, R.W.M.; Perry, S.F. Loss-of-Function Approaches in Comparative Physiology: Is There a Future for Knockdown Experiments in the Era of Genome Editing? Journal of Experimental Biology 2019, 222, jeb175737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapahnke, M.; Banning, A.; Tikkanen, R. Random Splicing of Several Exons Caused by a Single Base Change in the Target Exon of CRISPR/Cas9 Mediated Gene Knockout. Cells 2016, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, B.; Henriques, A.C.; Silva, P.M.A.; Bousbaa, H. Three-Dimensional Spheroids as In Vitro Preclinical Models for Cancer Research. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Yan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Choy, E.; Hornicek, F.J.; Mankin, H.; Duan, Z. CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Silencing of CD44 in Human Highly Metastatic Osteosarcoma Cells. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2018, 46, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, S.; Hascall, V.C.; Markwald, R.R.; Ghatak, S. Interactions between Hyaluronan and Its Receptors (CD44, RHAMM) Regulate the Activities of Inflammation and Cancer. Front Immunol 2015, 6, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbownik, M.S.; Nowak, J.Z. Hyaluronan: Towards Novel Anti-Cancer Therapeutics. Pharmacological Reports 2013, 65, 1056–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dovedytis, M.; Liu, Z.J.; Bartlett, S. Hyaluronic Acid and Its Biomedical Applications: A Review. Engineered Regeneration 2020, 1, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| OS | EFS | |||

| HR | p-Value | HR | p-Value | |

| Tumour size | 1.001 | 0.9184 | 1.002 | 0.4617 |

| CD44 expression | 1.031 | 0.0060 | 1.020 | 0.0057 |

| Metastasis | 17.41 | 0.0101 | 13.35 | 0.0002 |

| Age | 1.052 | 0.1234 | 1.044 | 0.1290 |

| Sex | 0.6488 | 0.7453 | 0.2177 | 0.1725 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).