1. Introduction

Dyslipidemia, characterized by abnormal levels of lipids in the blood, is a well-recognized factor influencing overall cardiovascular health [

1,

2]. Both genetic predisposition and dietary habits play pivotal roles in determining cholesterol levels and overall lipid metabolism [

3]. The interplay between genetic factors and lifestyle choices has been extensively studied, with evidence suggesting that different ethnic groups exhibit varying lipid profiles and metabolic responses [

3,

4,

5]. Epidemiological data reveals substantial variations in the prevalence of dyslipidemia across different ethnicities. South Asians, for example, demonstrate a significantly higher prevalence of lipid imbalances compared to Caucasians, which has been attributed to both genetic factors and dietary patterns rich in carbohydrates and refined sugars [

2,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Individuals of Asian descent tend to have lower levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), higher triglyceride levels, and a greater prevalence of small dense low-density lipoprotein (sdLDL), factors that may impact cardiovascular health [

7,

9]. Emerging research suggests that Asian populations may require tailored approaches to lipid management due to distinct metabolic traits [

5].

Botanical extracts and polyphenols have been widely investigated for their potential role in supporting healthy lipid metabolism, particularly for individuals seeking natural alternatives to conventional lipid-lowering strategies. Various plant and plant-derived compounds, including red yeast rice, garlic, guggul, bergamot, fiber-enriched botanicals, resveratrol and berberine have demonstrated lipid-modulating effects through mechanisms such as hepatic cholesterol metabolism regulation, bile acid excretion enhancement, and modulation of lipid pathways at different cellular levels [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. However, despite extensive research on these compounds, comparative data on their effectiveness across different ethnic populations remains limited.

Among the most studied botanicals, bergamot has gained increasing attention for its rich composition of flavonoids, including neoeriocitrin, neohesperidin, and naringin, which have demonstrated clinically supported effects on lipid metabolism through well-described mechanisms of action [

10,

16]. In particular, two complementary clinical trials demonstrated that 150 mg of flavonoids (including neoeriocitrin, naringin, neohesperidin) from a standardized bergamot extract (Bergavit™) helped maintain healthy cholesterol levels by supporting optimal total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and triglycerides (TG), while promoting favorable HDL-C levels. These two studies emphasize both the early onset and the sustained efficacy of this bergamot extract, offering robust evidence of its physiological support for cardiovascular health. The first 6-month observational trial involving 80 participants demonstrated significant and progressive improvements in lipid parameters, highlighting the supplement’s long-term effectiveness. In addition to reductions in total and LDL cholesterol, the study reported a favorable shift in LDL subfractions, with an increase in LDL-1 (pattern A), which are less atherogenic than the pattern B LDL molecules (i.e., LDL-3, -4, -5), which were significantly decreased. Due to their larger particle size and lower density, LDL-1 particles are less able to penetrate arterial walls, are less prone to oxidation, and exhibit lower inflammatory potential, thereby contributing to a reduced atherogenic risk. [

10]. The second randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 60 participants confirmed the supplement’s safety and efficacy, with benefits evident by 2 months and continuing through the 4 months follow-up [

17]. Together, these studies, both conducted in Caucasian populations, confirm the reproducibility and consistency of 150 mg of flavonoid supplementation from a standardized bergamot extract’s lipid-modulating effects, while also providing insights into its gradual and sustained mechanism of action. However, no clinical trials to date have evaluated the lipid-modulating effects of bergamot extract in Asian populations, where genetic, dietary, and lifestyle factors may influence individual responses to supplementation [

5]. The present study aims to fill this gap by conducting the first clinical trial assessing the effects of a standardized bergamot extract on lipid parameters in an Asian cohort. By confirming its efficacy and safety in this population, this research provides scientific insights into the use of bergamot extract across diverse ethnic groups, contributing to the development of more personalized approaches to lipid health worldwide.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethics

This clinical trial was conducted at Complife Asia Testing Technology (Xicheng District, Beijing, China) between September 2022 and October 2024. The study employed a monocentric, randomized, placebo-controlled design to evaluate the intervention’s effects over a four-month period. Eligible participants were enrolled at baseline (Month 0, M0) following a screening assessment that included blood analysis to determine low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels, which served as a primary inclusion criterion. Study visits were scheduled at baseline (M0) and subsequently after 2 (M2), 3 (M3), and and 4 (M4) months, during which clinical evaluations and sample collections were performed to monitor treatment outcomes and safety parameters.

The study protocol (H.E.HU.AC.NMS00.210.00.00_IT0002159/22) was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Calabria on 21 March 2022. The clinical trial was prospectively registered in the ISRCTN registry under the identifier ISRCTN90859063 (

https://doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN90859063, accessed on 13 June 2025).

All study procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant national and institutional guidelines governing research involving human subjects. Prior to enrollment, each participant received detailed oral and written information regarding the study’s objectives, procedures, potential risks, and expected benefits. Informed consent was obtained in writing from all individuals before participation, ensuring voluntary involvement and respect for personal autonomy throughout the study.

2.2. Participants

Eligible participants were adult male and female individuals aged between 40 and 70 years. The study population was stratified such that half of the participants had LDL-C levels ranging from 119 to 139 mg/dL, while the other half had LDL-C levels between 100 and 159 mg/dL.

Exclusion criteria included the use of statins or lipid-lowering nutraceuticals within one month prior to study initiation; adherence to a vegetarian diet; significant changes in habitual lifestyle (such as physical activity levels or dietary habits) within two weeks before the screening visit; a positive medical history of gastrointestinal disorders or conditions affecting visceral motility; pregnancy or lactation (only for women); smoking; a medical history of pathologies or pharmacological treatments potentially interfering with the test product; non-adherence to the treatment regimen, defined as discontinuation of the product for more than one week; current engagement in a weight loss diet or use of weight control products; history of drug, alcohol, or substance abuse; known food intolerances or allergies; participation in another clinical trial within the previous month; the presence of unstable medical conditions (e.g., cardiac arrhythmias, myocardial ischemia, uncontrolled hypertension or hypotension, renal failure, or diabetes mellitus); history of stroke or cerebrovascular accident; active cancer under chemotherapy; use of diuretics within one month prior to screening; and any psychological, cognitive, or physical condition that could impair the participant’s ability to fully comply with study procedures.

2.3. Intervention, Randomization, and Masking

The test item was a commercially available, standardized natural extract (BergavitTM, Bionap S.r.l., Piano Tavola Belpasso, CT, Italy) characterized by its flavonoids content, including neohesperidin, naringin, and neoeriocitrin. The extract is derived from the juice of Citrus aurantium L. var. bergamia (bergamot), a citrus fruit known for its elevated concentration of bioactive flavonoids. For the purposes of the clinical trial, Bergavit™ (BRG) was administered (at breakfast) in the form of oral capsules, each containing 375 mg of the extract, corresponding to a daily intake of approximately 150 mg of flavonoids. The capsule formulation was completed with excipients to ensure capsule stability and consistency, comprising 134 mg of pregelatinized starch, 0.4 mg of magnesium stearate, 0.3 mg of talc, and 0.3 mg of silica.

The placebo capsules (PLA) were identical in appearance and composition to the active formulation, with the exception that the 375 mg of Bergavit™ extract was replaced by an equivalent amount (375 mg) of maltodextrin. All other excipients were maintained.

The allocation of participants to the active or placebo group was conducted through a randomized process based on the sequential entry number of each subject into the study. A computer-generated, balanced (1:1), and restricted randomization list was employed, utilizing Efron’s biased coin design to ensure allocation concealment and balance between groups. The randomization sequence was generated using PASS 11 software (version 11.0.8; PASS, LLC, Kaysville, UT, USA).

Allocation concealment was achieved using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes, each containing the pre-assigned intervention code according to the randomization list. These envelopes were securely stored by an independent third party not involved in participant recruitment, data collection, or analysis.

2.4. Clinical Biochemistry

Venous blood samples were collected after an overnight fast of approximately 12 hours by a trained nurse in a certified clinical biochemistry laboratory. The primary endpoints of the study were low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), total cholesterol (TC), oxidized LDL (ox-LDL), and paraoxonase-1 (PON1) enzymatic activity. Secondary endpoints included anthropometric and metabolic parameters, specifically body weight, blood pressure, triglycerides (TG), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), C-reactive protein (CRP), serum creatinine, and additional measurements of PON1 activity. All hematological and biochemical parameters were determined using standardized, validated routine laboratory methods.

2.5. Statistical methods

Pairwise comparisons were conducted to evaluate changes in biochemical and clinical parameters over time and between treatment arms. Statistical analyses were performed using NCSS 10 software (version 10.0.7 for Windows; NCSS, LLC, Kaysville, UT, USA).

Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and statistical significance was reported using the following notation: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

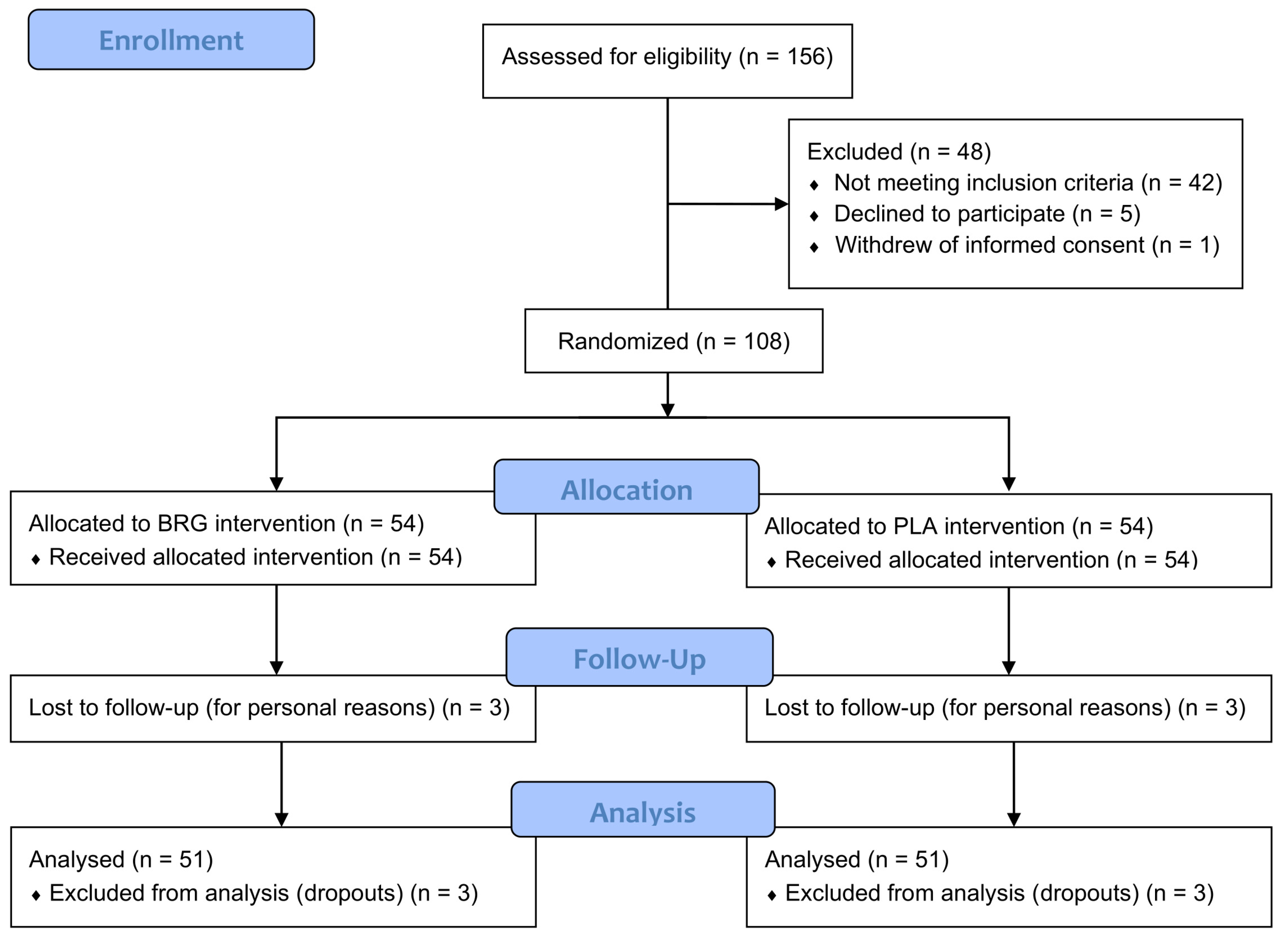

A total of 156 individuals were screened for eligibility based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Following initial assessment, 48 subjects were excluded prior to randomization. Specifically, 42 individuals did not meet the inclusion criteria, most commonly due to low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentrations or body mass index (BMI) values falling outside the required range. Additionally, 5 participants declined to participate after receiving detailed study information, and 1 subject withdrew informed consent before formal enrollment. As a result, 108 participants met all eligibility requirements and were subsequently randomized into the study.

A total of 102 participants completed the study, with 51 individuals in each treatment group. Six participants (three from each group) discontinued the intervention prematurely, after 1 or 2 months of supplementation, due to personal reasons not related to product use. These individuals were classified as lost to follow-up and were excluded from the per-protocol analysis (

Figure 1). The demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of the study population are presented in

Table 1.

3.2. Primary Endpoints

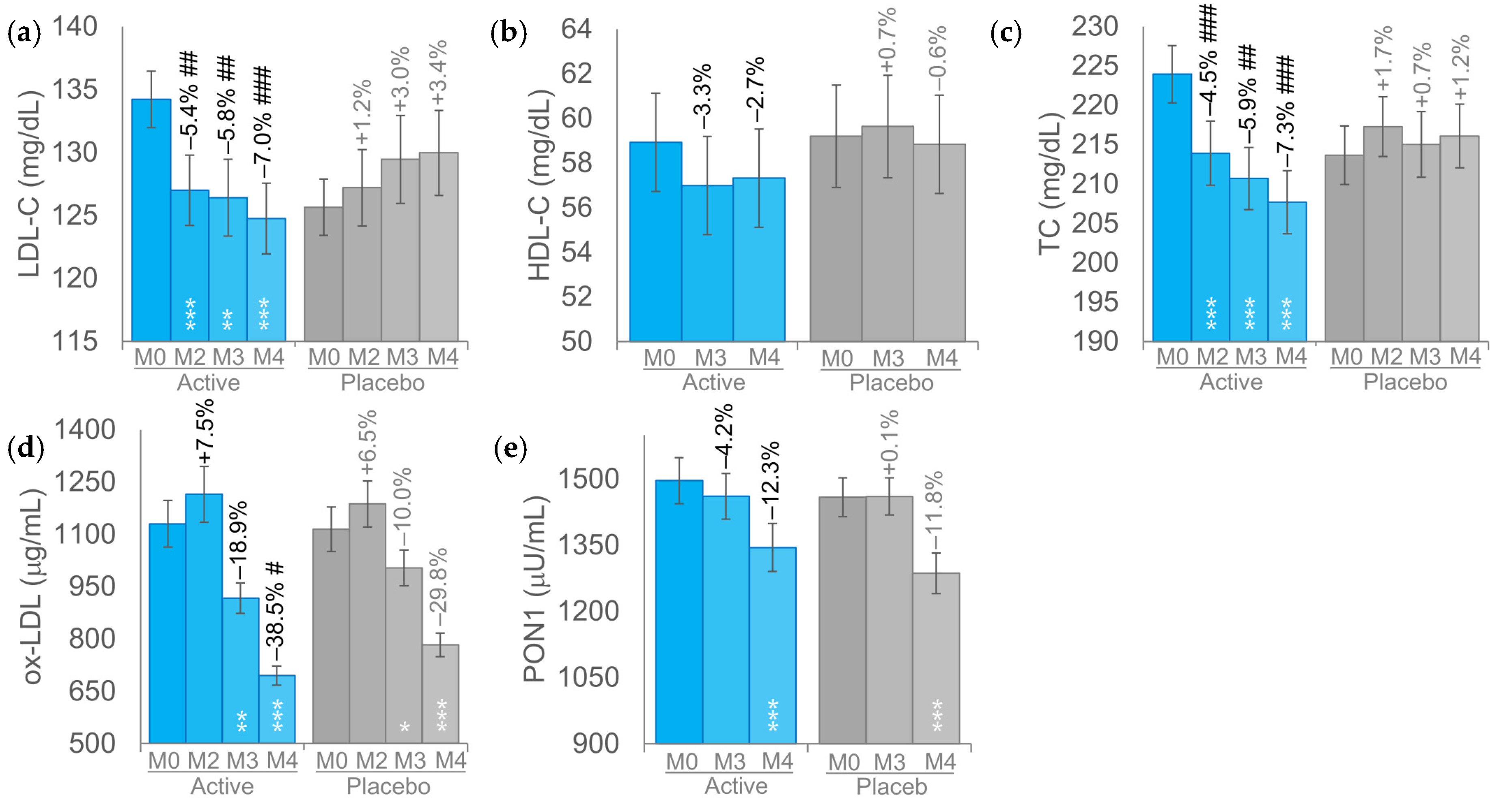

At baseline, the mean LDL-C blood concentrations were 134.2 ± 2.2 mg/dL in the BRG group and 125.6 ± 2.2 mg/dL in the PLA group (

p > 0.05). In the BRG group, LDL-C levels exhibited a progressive reduction, with a 5.4% (127.0 ± 2.8 mg/dL,

p < 0.001) decrease observed after two months followed by a further reduction of 5.8% (126.4 ± 3.0 mg/dL,

p < 0.01) and 7.0% (124.7 ± 2.8 mg/dL,

p < 0.001) after 3 and 4 months, respectively (

Figure 2a). Although not statistically significant (

p > 0.05), LDL-C levels in the PLA group exhibited an upward trend over the study period. Differences between the BRG and PLA were statistically significant (

p < 0.05) at each timepoint.

The changes in HDL-C levels over the course of the study were not statistically significant in either the BRG or PLA group (

p > 0.05). In both groups, HDL-C values remained relatively stable throughout the intervention period. No statistically significant (

p > 0.05) differences were observed between the BRG and PLA groups throughout the study period (

Figure 2b).

In the BRG group, baseline total cholesterol (TC) levels (223.9 ± 3.6 mg/dL) were significantly reduced by 4.5% at month 2 (213.9 ± 4.1 mg/dL, p < 0.001), 5.9% at month 3 (210.7 ± 4.0 mg/dL, p < 0.001), and 7.3% at month 4 (207.7 ± 4.0 mg/dL, p < 0.001), demonstrating a consistent and statistically significant downward trend over time (

Figure 2c). In the PLA group, total cholesterol (TC) levels remained unchanged throughout the study period (p > 0.05). In contrast, the differences in TC levels between the BRG and PLA groups were statistically significant at all assessed time points (

p < 0.05).

In the BRG group, the ox-LDL levels decreased by 18.9% (

p < 0.01) starting from M3 and further decreased by 38.5% (

p < 0.001) at M4. A statistically significant reduction in ox-LDL levels was also observed in the PLA group, with a 10.0% decrease at M3 (p < 0.05) and a 29.8% decrease at M4 (p < 0.001), although the magnitude of change was consistently lower compared to the BRG group (

Figure 2d). Variations of ox-LDL levels between BRG and PLA groups were statistically significant at M4.

No statistically significant differences in PON1 activity were observed between the BRG and PLA groups (

p > 0.05) throughout the study period (

Figure 2e).

In the subgroup with a lower LDL-C range (119–139 mg/dL) the mean LDL-C levels were 130.7 ± 1.7 mg/dL for the BRG group and 130.5 ± 1.6 mg/dL for the PLA group (

p > 0.05). In the subgroup with lower LDL-C concentrations (119 ≤ LDL-C ≤ 139 mg/dL), the results for LDL-C, HDL-C, and total cholesterol (TC) were consistent with those observed in the overall study population (

Table 2). Similarly, as in the entire cohort, no significant differences were detected in oxidized LDL (ox-LDL) and paraoxonase-1 (PON1) variations between the BRG and PLA groups.

3.3. Secondary Endpoints

Throughout the duration of the intervention, no adverse effects on hepatic or renal function were detected in either group. Specifically, key hepatic biomarkers including aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), and C-reactive protein (CRP) remained within normal physiological ranges and did not show statistically significant variations from baseline at any time point (

Table 3). Similarly, serum creatinine (CR), a principal marker of renal function, remained stable, suggesting that neither the active treatment nor the placebo had a detrimental impact on liver or kidney health. In addition, glycemic parameters, including fasting blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), were not significantly altered by the intervention. In the BRG group, triglyceride (TG) levels remained stable over the course of the study, whereas in the placebo (PLA) group, TG levels increased by 19.0% (

p < 0.01) at M3 and by 28.4% (

p < 0.001) at M4. The differences between the BRG and PLA groups were also statistically significant at both timepoints (

p < 0.01 at M3 and

p < 0.001 at M4).

Participants in both the BRG and PLA groups demonstrated high treatment adherence rates (> 90%), with no withdrawals attributed to treatment-related adverse events. These findings further reinforce the favorable outcomes observed in key hepatic and renal biochemical parameters, collectively supporting the safety and tolerability profile of the intervention and indicating its good acceptability among study participants.

4. Discussion

Dyslipidemia was identified as one of the three primary risk factors targeted by the

Healthy China 2030 initiative, a national strategic framework that underscores the critical role of health in China’s socioeconomic development [

18].

Recent epidemiological studies indicate that dyslipidemia is emerging as a major public health concern among Chinese adults, characterized by an increasing prevalence [

19,

20]. Despite the growing burden, the rates of awareness, treatment, and effective control remain alarmingly low, underscoring a critical gap in preventive healthcare and lipid management strategies within this population [

18,

21,

22,

23,

24]. This situation is further exacerbated by increasing reports of statin-associated adverse effects and statin intolerance, which contribute to suboptimal statin utilization and poor patient adherence to lipid-lowering therapy [

25,

26]. Against this backdrop, naturally derived bioactive compounds, employed as part of non-pharmacological interventions, are gaining widespread consumer acceptance. This preference is largely attributed to their favorable toxicological profiles and perceived environmental sustainability compared to conventional synthetic pharmaceuticals [

27].

This study aimed to assess the LDL-C-lowering efficacy of bergamot extract in an Asian population, with the goal of enhancing the generalizability of findings from our previous clinical trial conducted in a Caucasian cohort [

17]. Considering the ethnic variability in lipid profiles and treatment-associated response, evaluating the effectiveness of bergamot extract in a distinct population is essential for confirming its broader clinical applicability and potential integration into culturally tailored dyslipidemia management strategies.

The Bergavit extract demonstrated a significant LDL-C-lowering effect beginning from the second month of supplementation, thereby corroborating the outcomes previously observed in a Caucasian population. In addition to its effect on LDL-C, the Bergavit extract consumption was associated with a significant reduction in TC at all assessed time points, as well as a marked decrease in ox-LDL levels after four months of supplementation. These findings suggest a broader cardioprotective effect on lipid metabolism and oxidative stress-related atherogenic risk [

28,

29].

The marked reduction in ox-LDL levels observed in this study (up to 38.5%), despite the absence of a significant increase in PON1 activity, suggests that Bergavit™ may exert its lipid-lowering effects through multiple antioxidative mechanisms that may vary in prominence depending on the target population. This interpretation aligns with the mechanisms of action reported by Toth et al. and Spina et al., which demonstrated consistent reductions in LDL-C and TC across different populations, supporting the potential of Bergavit™ as a flexible nutraceutical intervention capable of delivering clinically relevant LDL-C and TC reductions irrespective of ethnic and environmental variabilities.

The absence of a significant HDL-C increase in the Chinese population following BRG extract supplementation may reflect the extract’s primary mechanism targeting LDL-C pathways, ethnic-specific genetic factors affecting HDL metabolism, and potential ceiling effects based on baseline HDL-C values. Further studies are warranted to explore whether extended treatment duration, higher doses, or co-interventions may enhance HDL-C response in this demographic [

31,

32,

33,

34]. All the data related to lipid profile and the stability of PON1 activity observed could be partially explained by the negative correlation of paraxonase activity with TC and LDL-C levels and positive correlation between paraxonase activity with HDL-C and TG in Asian populations [

30].

Notably, comparable results were observed in both the lower (119 ≤ LDL-C ≤ 139 mg/dL) and higher (100 ≤ LDL-C ≤ 159 mg/dL) LDL-C subgroups. This suggests that the intervention may produce consistent lipid-lowering effects across a spectrum of baseline LDL-C levels, underscoring its potential utility in individuals with varying degrees of cardiovascular risk.

This study represents the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial to assess the lipid-lowering efficacy and safety of a polyphenol-standardized Citrus bergamia extract in an Asian population. A major strength lies in its rigorous study design, including stratified randomization, allocation concealment, and the use of validated clinical and biochemical endpoints. The relatively long intervention duration (4 months) and intermediate time-point assessments allowed for the evaluation of both short- and longer-term effects of supplementation. The high compliance rate and minimal dropout enhance the reliability of the findings. Despite these strengths, certain limitations should be acknowledged. The lack of dietary control among participants is the major limitation of this study. However, the variability that could be introduced by an unmonitored intake of nutrients or compounds potentially influencing the measured parameters is taken under control in the PLA group.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, oral supplementation with an extract of Citrus bergamia providing a standardized daily dose of 150 mg of flavonoids (including neohesperidin, naringin, and neoeriocitrin) proved to be significantly effective in reducing total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels both in the short term and over prolonged use, with clinically meaningful effects observed as early as the second month of intake. Interestingly, similar results were observed across the entire LDL-C range studied (100–159 mg/dL), including within the subgroup of participants with intermediate baseline LDL-C levels (119–139 mg/dL). These findings suggest that the intervention may exert consistent lipid-modulating effects regardless of baseline LDL-C concentration within this range, highlighting its potential applicability across different cardiovascular risk profiles.

These findings are consistent with, and further confirm, the results obtained in two previous studies conducted in Caucasian populations [

10,

17], thereby reinforcing the reproducibility and robustness of the observed effects. Consistency across studies highlights the reliability of the intervention’s biochemical and clinical outcomes, particularly regarding its safety, tolerability, and efficacy. The multiple antioxidative mechanisms exerted by Bergavit may also support the progressive and sustained reduction in lipid parameters over time. Taken together, the present data contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting the intervention as a safe and well-tolerated solution in the Asian populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.N. and V.I.; methodology, V.N., X.Y. and V.I.; validation, V.N., F.A. and X.Y.; formal analysis, V.N. and X.Y.; investigation, X.Y.; resources, V.N. and V.Z.; data curation, V.N., F.A. and X.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, V.N.; writing—review and editing, V.N., F.A. and X.Y.; visualization, V.N.; supervision, V.N.; project administration, V.N. and F.A.; funding acquisition, V.N. and V.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Bionap Srl (95032 Piano Tavola Belpasso, CT, Italy). The APC was funded by Bionap Srl (95032 Piano Tavola Belpasso, CT, Italy).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study can be obtained upon request from the corresponding author. As they are the property of the study sponsor, Bionap Srl (95032 Piano Tavola Belpasso, CT, Italy), the data are not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the Complife China and Italia staff for their professionalism and support during the study, particularly in recruiting participants and assisting with the study’s development.

Conflicts of Interest

V.Z. is a Bionap S.r.l. employee. This does not alter the author’s adherence to all the journal policies on sharing data and materials. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HDL-C |

High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| sdLDL |

small dense Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| TC |

Total Cholesterol |

| LDL-C |

Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| TG |

Triglycerides |

| ox-LDL |

oxidized LDL Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| PON1 |

Paraoxonase-1 |

| AST |

Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| ALT |

Alanine Aminotransferase |

| GGT |

Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase |

| HbA1c |

Glycated Hemoglobin |

| hs-CRP |

high sensitivity C-Reactive Protein |

| CR |

Creatinine |

References

- Pirillo, A.; Casula, M.; Olmastroni, E.; Norata, G. D.; Catapano, A. L. Global Epidemiology of Dyslipidaemias. Nat Rev Cardiol 2021, 18, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappan, N.; Awosika, A. O.; Rehman, A. Dyslipidemia. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, J.; Romanelli, R.; Zhao, B.; Azar, K. M. J.; Hastings, K. G.; Nimbal, V.; Fortmann, S. P.; Palaniappan, L. P. Dyslipidemia in Special Ethnic Populations. Cardiol Clin 2015, 33, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-F.; Chang, Y.-H.; Chien, S.-C.; Lin, Y.-H.; Yeh, H.-Y. Epidemiology of Dyslipidemia in the Asia Pacific Region. International Journal of Gerontology 2018, 12, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z.-V.; Llanes, E. J.; Sukmawan, R.; Thongtang, N.; Ho, H. Q. T.; Barter, P.; on behalf of the Cardiovascular RISk Prevention (CRISP) in Asia Network. Prevalence of Plasma Lipid Disorders with an Emphasis on LDL Cholesterol in Selected Countries in the Asia-Pacific Region. Lipids in Health and Disease 2021, 20, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical Feature: The Unique South Asian Phenotype and Opportunities for Early Intervention to Prevent Diabetes and ASCVD. Available online: https://www.lipid.org/lipid-spin/summer-2020/clinical-feature-unique-south-asian-phenotype-and-opportunities-early (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Yuan, L.; Verhoeven, A.; Blomberg, N.; van Eyk, H. J.; Bizino, M. B.; Rensen, P. C. N.; Jazet, I. M.; Lamb, H. J.; Rabelink, T. J.; Giera, M.; van den Berg, B. M. Ethnic Disparities in Lipid Metabolism and Clinical Outcomes between Dutch South Asians and Dutch White Caucasians with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Metabolites 2024, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Lee, J. E.; Song, W. O.; Paik, H.-Y.; Song, Y. Carbohydrate Intake and Refined-Grain Consumption Are Associated with Metabolic Syndrome in the Korean Adult Population. J Acad Nutr Diet 2014, 114, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makshood, M.; Post, W. S.; Kanaya, A. M. Lipids in South Asians: Epidemiology and Management. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 2019, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, P. P.; Patti, A. M.; Nikolic, D.; Giglio, R. V.; Castellino, G.; Biancucci, T.; Geraci, F.; David, S.; Montalto, G.; Rizvi, A.; Rizzo, M. Bergamot Reduces Plasma Lipids, Atherogenic Small Dense LDL, and Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Subjects with Moderate Hypercholesterolemia: A 6 Months Prospective Study. Front Pharmacol 2015, 6, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanotti, I.; Dall’Asta, M.; Mena, P.; Mele, L.; Bruni, R.; Ray, S.; Del Rio, D. Atheroprotective Effects of (Poly)Phenols: A Focus on Cell Cholesterol Metabolism. Food Funct 2015, 6, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurana, S.; Venkataraman, K.; Hollingsworth, A.; Piche, M.; Tai, T. C. Polyphenols: Benefits to the Cardiovascular System in Health and in Aging. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3779–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangney, C.; Rasmussen, H. E. Polyphenols, Inflammation, and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2013, 15, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, W.; Arshad, M. S.; Jabeen, A.; Muhammad Anjum, F.; Qaisrani, T. B.; Suleria, H. A. R. Fiber-Enriched Botanicals: A Therapeutic Tool against Certain Metabolic Ailments. Food Sci Nutr 2022, 10, 3203–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wal, A.; Verma, N.; Balakrishnan, S. K.; Gahlot, V.; Dwivedi, S.; Sahu, P. K.; Tabish, M.; Wal, P. A Systematic Review of Herbal Interventions for the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases. Curr Cardiol Rev 2024, 20, e030524229664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauman, M. C.; Johnson, J. J. Clinical Application of Bergamot (Citrus Bergamia) for Reducing High Cholesterol and Cardiovascular Disease Markers. Integr Food Nutr Metab 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina, A.; Amone, F.; Zaccaria, V.; Insolia, V.; Perri, A.; Lofaro, D.; Puoci, F.; Nobile, V. Citrus Bergamia Extract, a Natural Approach for Cholesterol and Lipid Metabolism Management: A Randomized, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Foods 2024, 13, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Z.; Huang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Mao, A.; Qiu, W. Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, and Control of Dyslipidemia in Chinese Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med 2023, 10, 1186330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Su, X.; Chen, J.; Xu, B.; Tao, J.; Wang, Z.; Ma, A.; Li, H. Economic Burden of Myocardial Infarction Combined With Dyslipidemia. Front Public Health 2021, 9, 648172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Herrera, K.; Pedroza-Tobías, A.; Hernández-Alcaraz, C.; Ávila-Burgos, L.; Aguilar-Salinas, C. A.; Barquera, S. Attributable Burden and Expenditure of Cardiovascular Diseases and Associated Risk Factors in Mexico and Other Selected Mega-Countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16, 4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Zhang, F.; Sun, L.; Lin, J.; Wang, D.-M.; Wang, L.-Y. Genome-Wide Linkage Scan of a Pedigree with Familial Hypercholesterolemia Suggests Susceptibility Loci on Chromosomes 3q25-26 and 21q22. PLoS One 2011, 6, e24838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-Z.; Su, L.; Liang, B.-Y.; Tan, J.-J.; Chen, Q.; Long, J.-X.; Xie, J.-J.; Wu, G.-L.; Yan, Y.; Guo, X.-J.; Gu, L. Trends in Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, and Control of Diabetes Mellitus in Mainland China from 1979 to 2012. Int J Endocrinol 2013, 2013, 753150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Hao, G.; Zhang, Z.; Shao, L.; Tian, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zheng, C.; Wang, J.; Zhu, M.; Weintraub, W. S.; Gao, R.; China Hypertension Survey Investigators. Status of Hypertension in China: Results From the China Hypertension Survey, 2012-2015. Circulation 2018, 137, 2344–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Li, K.; Yan, A. F.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, J.; Cheskin, L. J.; Hussain, A.; Wang, Y. Prevalence, Management, and Associated Factors of Obesity, Hypertension, and Diabetes in Tibetan Population Compared with China Overall. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 8787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.-J.; Dou, K.-F.; Zhou, Z.-G.; Zhao, D.; Ye, P.; Chen, H.; Chen, Z.-Y.; Peng, D.-Q.; Guo, Y.-L.; Wu, N.-Q.; Qian, J.; Experts, C. Chinese Expert Consensus on the Clinical Diagnosis and Management of Statin Intolerance. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2024, 115, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Jia, X.; Min, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhai, Y. Relationships between Beliefs about Statins and Non-Adherence in Inpatients from Northwestern China: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, X.; Shi, S.; Liu, B.; Shan, M.; Tang, D.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Lu, C.; Wang, Y. Bioactive Compounds from Herbal Medicines to Manage Dyslipidemia. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2019, 118, 109338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navab, M.; Berliner, J. A.; Watson, A. D.; Hama, S. Y.; Territo, M. C.; Lusis, A. J.; Shih, D. M.; Van Lenten, B. J.; Frank, J. S.; Demer, L. L.; Edwards, P. A.; Fogelman, A. M. The Yin and Yang of Oxidation in the Development of the Fatty Streak. A Review Based on the 1994 George Lyman Duff Memorial Lecture. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1996, 16, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zern, T. L.; Fernandez, M. L. Cardioprotective Effects of Dietary Polyphenols1. The Journal of Nutrition 2005, 135, 2291–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, N.; Roy, A. C.; Teo, S. H.; Tay, J. S.; Ratnam, S. S. Influence of Serum Paraoxonase Polymorphism on Serum Lipids and Apolipoproteins. Clin Genet 1991, 40, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barter, P.; Gotto, A. M.; LaRosa, J. C.; Maroni, J.; Szarek, M.; Grundy, S. M.; Kastelein, J. J. P.; Bittner, V.; Fruchart, J.-C.; Treating to New Targets Investigators. HDL Cholesterol, Very Low Levels of LDL Cholesterol, and Cardiovascular Events. N Engl J Med 2007, 357, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teslovich, T. M.; Musunuru, K.; Smith, A. V.; Edmondson, A. C.; Stylianou, I. M.; Koseki, M.; Pirruccello, J. P.; Ripatti, S.; Chasman, D. I.; Willer, C. J.; Johansen, C. T.; Fouchier, S. W.; Isaacs, A.; Peloso, G. M.; Barbalic, M.; Ricketts, S. L.; Bis, J. C.; Aulchenko, Y. S.; Thorleifsson, G.; Feitosa, M. F.; Chambers, J.; Orho-Melander, M.; Melander, O.; Johnson, T.; Li, X.; Guo, X.; Li, M.; Shin Cho, Y.; Jin Go, M.; Jin Kim, Y.; Lee, J.-Y.; Park, T.; Kim, K.; Sim, X.; Twee-Hee Ong, R.; Croteau-Chonka, D. C.; Lange, L. A.; Smith, J. D.; Song, K.; Hua Zhao, J.; Yuan, X.; Luan, J.; Lamina, C.; Ziegler, A.; Zhang, W.; Zee, R. Y. L.; Wright, A. F.; Witteman, J. C. M.; Wilson, J. F.; Willemsen, G.; Wichmann, H.-E.; Whitfield, J. B.; Waterworth, D. M.; Wareham, N. J.; Waeber, G.; Vollenweider, P.; Voight, B. F.; Vitart, V.; Uitterlinden, A. G.; Uda, M.; Tuomilehto, J.; Thompson, J. R.; Tanaka, T.; Surakka, I.; Stringham, H. M.; Spector, T. D.; Soranzo, N.; Smit, J. H.; Sinisalo, J.; Silander, K.; Sijbrands, E. J. G.; Scuteri, A.; Scott, J.; Schlessinger, D.; Sanna, S.; Salomaa, V.; Saharinen, J.; Sabatti, C.; Ruokonen, A.; Rudan, I.; Rose, L. M.; Roberts, R.; Rieder, M.; Psaty, B. M.; Pramstaller, P. P.; Pichler, I.; Perola, M.; Penninx, B. W. J. H.; Pedersen, N. L.; Pattaro, C.; Parker, A. N.; Pare, G.; Oostra, B. A.; O’Donnell, C. J.; Nieminen, M. S.; Nickerson, D. A.; Montgomery, G. W.; Meitinger, T.; McPherson, R.; McCarthy, M. I.; McArdle, W.; Masson, D.; Martin, N. G.; Marroni, F.; Mangino, M.; Magnusson, P. K. E.; Lucas, G.; Luben, R.; Loos, R. J. F.; Lokki, M.-L.; Lettre, G.; Langenberg, C.; Launer, L. J.; Lakatta, E. G.; Laaksonen, R.; Kyvik, K. O.; Kronenberg, F.; König, I. R.; Khaw, K.-T.; Kaprio, J.; Kaplan, L. M.; Johansson, Å.; Jarvelin, M.-R.; Cecile J. W. Janssens, A.; Ingelsson, E.; Igl, W.; Kees Hovingh, G.; Hottenga, J.-J.; Hofman, A.; Hicks, A. A.; Hengstenberg, C.; Heid, I. M.; Hayward, C.; Havulinna, A. S.; Hastie, N. D.; Harris, T. B.; Haritunians, T.; Hall, A. S.; Gyllensten, U.; Guiducci, C.; Groop, L. C.; Gonzalez, E.; Gieger, C.; Freimer, N. B.; Ferrucci, L.; Erdmann, J.; Elliott, P.; Ejebe, K. G.; Döring, A.; Dominiczak, A. F.; Demissie, S.; Deloukas, P.; de Geus, E. J. C.; de Faire, U.; Crawford, G.; Collins, F. S.; Chen, Y. I.; Caulfield, M. J.; Campbell, H.; Burtt, N. P.; Bonnycastle, L. L.; Boomsma, D. I.; Boekholdt, S. M.; Bergman, R. N.; Barroso, I.; Bandinelli, S.; Ballantyne, C. M.; Assimes, T. L.; Quertermous, T.; Altshuler, D.; Seielstad, M.; Wong, T. Y.; Tai, E.-S.; Feranil, A. B.; Kuzawa, C. W.; Adair, L. S.; Taylor Jr, H. A.; Borecki, I. B.; Gabriel, S. B.; Wilson, J. G.; Holm, H.; Thorsteinsdottir, U.; Gudnason, V.; Krauss, R. M.; Mohlke, K. L.; Ordovas, J. M.; Munroe, P. B.; Kooner, J. S.; Tall, A. R.; Hegele, R. A.; Kastelein, J. J. P.; Schadt, E. E.; Rotter, J. I.; Boerwinkle, E.; Strachan, D. P.; Mooser, V.; Stefansson, K.; Reilly, M. P.; Samani, N. J.; Schunkert, H.; Cupples, L. A.; Sandhu, M. S.; Ridker, P. M.; Rader, D. J.; van Duijn, C. M.; Peltonen, L.; Abecasis, G. R.; Boehnke, M.; Kathiresan, S. Biological, Clinical and Population Relevance of 95 Loci for Blood Lipids. Nature 2010, 466, 707–713. [CrossRef]

- Todur, S. P.; Ashavaid, T. F. Association of CETP and LIPC Gene Polymorphisms with HDL and LDL Sub-Fraction Levels in a Group of Indian Subjects: A Cross-Sectional Study. Indian J Clin Biochem 2013, 28, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallaud, C.; Gueguen, R.; Sass, C.; Grow, M.; Cheng, S.; Siest, G.; Visvikis, S. Genetic Influences on Lipid Metabolism Trait Variability within the Stanislas Cohort. J Lipid Res 2001, 42, 1879–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).