1. Introduction

I argue transhumanism is not a radical rupture from humanism but its continuation—technologically intensified and corporately branded. The transhumanist vision of technologically enhanced humans does not escape the orbit of late-stage capitalism. Instead, it inherits and extends its core logic: commodification, individuation, and market capture.

The human, within this framework, is incubated and intubated by corporate parents—profit-driven entities like Apple

1, Meta

2, and Google

3. The question we now face is not merely “What kind of human will I become?” but “’Whose human am I?’ Are you an Apple human, a Meta human, or a Google human—in the branded warfare for subjectivity and market supremacy?”

This metaphor–of humans as biotechnological offspring of platform capital–adds a vivid biopolitical edge to critiques already circulating in posthumanist theory. In my work [

1], I develop the concept of

cybernetic subjectivity—a mode of being governed by corporate systems that organize perception, behavior, and affect through data-driven infrastructures. This resonates with Dean’s [

2,

3] analysis of neoliberal subject formation as a recursive feedback loop of optimization and performativity, as well as with Schafheitle et al.’s [

4] argument that datafication now operates as an infrastructure of organizational control.

What I offer here is not merely an extension of these critiques but a reframing: transhumanism as the incubation of human subjectivity within corporate infrastructures that act as techno-parental incubators and ventilators. This framing is supported by Morozov’s [

5] dismantling of Silicon Valley’s techno-solutionist mythology and by Barbrook and Cameron’s [

6] genealogy of transhumanism within the libertarian–neoliberal convergence they call the

Californian Ideology. The

enhanced human, then, is not an emancipated posthuman self but a cybernetic-neoliberal product engineered in branded ecologies, optimized for market alignment, and sold as freedom.

2. Background and Context

Before advancing my own argument, it is important to pause and trace a set of influential critiques developed by key figures in posthumanist theory. These interventions do not dismiss transhumanism wholesale. Rather, they interrogate the ideological underpinnings of transhumanism’s utopian promises of optimization, transcendence, and liberation through technology. What they reveal is that these promises are not neutral or novel; they are entangled with enduring assumptions about the human, the role of technology, and the logic of the market. Grasping the contours of these critiques is crucial, as my argument builds upon and extends them, particularly by drawing attention to the emergence of the branded, corporatized subject as a central figure in contemporary techno-futures.

2.1. Brief Historical Context

To situate this critique, it is important to recognize that transhumanism and posthumanism, despite sounding similar, emerge from fundamentally different genealogies. Transhumanism arose from Enlightenment humanism, Silicon Valley futurism, and techno-libertarian optimism. As Morozov [

5] has argued, Silicon Valley’s futurism is inseparable from its deeply embedded techno-solutionist worldview: an orientation that frames every social or political problem as a technological challenge to be optimized.

Barbrook and Cameron [

6] analyze this orientation more ideologically, tracing it to the Cold War fusion of countercultural libertarianism and neoliberal market logic; a formation they call the

Californian Ideology. Edwards [

7], meanwhile, places these developments in the longer arc of Cold War computing, showing how cybernetic systems thinking and military-sponsored technological infrastructures shaped the logics of control, abstraction, and technical mastery that underpin contemporary techno-futurist visions. Figures like Kurzweil [

8], Bostrom [

9], and More [

10] popularized its core vision: a future where human limitations (i.e., aging, disease, even death) can be overcome through technological enhancement. This vision often presumes a universal subject, but in practice it reflects the aspirations of a very particular kind of subject: affluent, able-bodied, Western, and male.

Posthumanism, by contrast, emerged from a critical tradition rooted in post-structuralism, feminist theory, ecological thought, and continental philosophy. Thinkers like Haraway [

11], Braidotti [

12], and Wolfe [

13] reject the idea of a stable, bounded human subject. Instead, they emphasize entanglement, vulnerability, and the de-centering of the human in favor of a more distributed understanding of agency across biological, technological, and environmental systems.

These two trajectories, one amplifying the liberal humanist subject through technology and the other deconstructing that very subject, do not merely offer competing definitions. They represent conflicting ontological and political commitments. And while posthumanism remains largely an academic critique, transhumanism is increasingly embedded in the infrastructure of everyday life, marketed through glossy visions of longevity, productivity, and hyper-efficiency. That shift–from discourse to system, from idea to interface–is where my argument begins.

2.2. Brief Terminological Glossary

To ensure clarity as we move forward, I want to briefly define some key terms that frequently appear in this discussion. Understanding these concepts is crucial for grasping the nuances of the critique I develop.

Biopolitics: The governance of life itself, where power operates through controlling bodies, health, and populations. It provides a useful lens for understanding how corporate and technological systems regulate human existence in subtle and pervasive ways.

Capitalism, Late-Stage: A term describing the advanced phase of capitalism characterized by high financialization, corporate monopolization, commodification of almost all social life, and global market dominance.

Cybernetics: An interdisciplinary science focused on systems, feedback loops, and control in machines and living organisms. It underpins many techno-futurist visions and critiques of subjectivity as governed by recursive information flows.

Datafication: The process by which social and biological phenomena are transformed into quantifiable data, enabling new forms of monitoring, control, and commodification within digital infrastructures.

Enlightenment: The intellectual and cultural movement that emerged in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries, emphasizing reason, science, individual autonomy, and progress. It laid the foundation for modern humanism but has been critiqued for promoting a narrow, anthropocentric view of the human subject.

Humanism: The Enlightenment-rooted belief in the human as a rational, autonomous individual, which is the center of moral and intellectual life. This tradition assumes human exceptionalism and mastery over nature.

Neoliberalism: An economic and political framework emphasizing free markets, individual responsibility, competition, and privatization. It shapes contemporary ideas of selfhood as entrepreneurial and self-optimizing.

Platform Sovereignty: A concept describing how tech giants like Apple, Google, and Meta act not merely as companies but as new forms of governance through their control of digital infrastructures, data flows, and social behaviors.

Posthumanism: A critical theoretical perspective that challenges humanism’s assumptions. It questions the fixed boundaries of the human, emphasizing relationality, hybridity, and the decentering of the human subject within a network of nonhuman agents, whether machines, animals, or ecological systems.

Subjectivity: The condition or quality of being a subject, often understood as the way individuals experience and interpret themselves and the world. In critical theory, subjectivity is seen as socially constructed and politically influenced.

Techno-solutionism: The belief that technological innovation can provide straightforward solutions to complex social, political, and ecological problems, often ignoring deeper systemic causes.

Technological Instrumentalism: The view that technology is a neutral tool to be used for human ends. This perspective overlooks the embedded political, economic, and ecological influences within technological systems.

By grounding the discussion in these terms, I aim to situate my argument clearly within ongoing debates while making it accessible to readers less familiar with this specialized vocabulary.

2.3. Humanist Continuity

One of the most incisive critiques emerging from posthumanist thought is that transhumanism does not represent a rupture from humanism; rather, it intensifies and retools its foundational commitments. Far from dismantling the figure of the rational, autonomous, mastery-driven subject, transhumanism reinforces it—only now outfitted with neural implants, biometric sensors, and biotech enhancements. The Enlightenment subject, long critiqued for its exclusions and abstractions, reappears here in upgraded form: not deconstructed, but fortified.

Building on this insight, thinkers such as Braidotti [

12] and Wolfe [

13] argue that transhumanism sustains the fantasy of human supremacy—over nature, over the body, and even over mortality itself. In this view, the transhumanist subject is not a departure from humanism but its perfection: a retooling, not a disruption. This continuity forms a core part of my own critique. I contend that transhumanism operates not as a radical break, but as a techno-utopian intensification of the liberal humanist legacy. It does not escape the figure of the autonomous subject; rather, it rebrands it as augmented and optimized, but still tethered to systems of control and deeply embedded in corporate infrastructures.

This continuity is exemplified in the work of key transhumanist thinkers. Kurzweil’s [

8] vision of the Singularity envisions a frictionless human future in which mortality and fallibility are technologically eliminated—a fantasy of pure transcendence that updates Enlightenment ideals through the lens of digital acceleration. Bostrom [

9], while attentive to existential risk, nonetheless frames the future of humanity through a managerial, optimization-driven logic. More [

10] explicitly links transhumanist enhancement to libertarian values of autonomy, competition, and personal self-mastery.

Together, these visions amplify humanist logic within the ideological apparatus of neoliberalism [

8,

9,

10]. What is enhanced is not simply the body or mind, but the market-oriented, self-optimizing subject: competitive, modular, and governable. As Fiesler [

14] notes, governance structures embedded in technological design shape and constrain users under the guise of choice. Lindtner et al. [

15] further reveal how spaces of supposed innovation (such as hackerspaces and maker cultures) reproduce neoliberal ideals through techno-entrepreneurial models of selfhood and labor.

By contrast, posthumanist theory, as articulated by Haraway’s [

11] cyborg theory, offers a more disruptive critique. Her cyborg ontology emphasizes hybridity, partiality, and entanglement. Rather than extending humanist logic, she envisions a non-liberal posthumanism rooted in relationality, situated knowledge, and resistance to commodified technoculture. intervention foregrounds a technogenesis that resists the market’s imperative to enhance and optimize. Rather than perfecting the human, it gestures toward forms of subjectivity that elude control, commodification, and corporate temporalities.

2.4. Technological Instrumentalism

Another critical concern articulated by posthumanist scholars centers on how transhumanism conceptualizes technology as a neutral, controllable instrument serving human ambitions. This framing, however, glosses over the intricate entanglements between technology, politics, economics, and power structures; and, crucially, how technology in turn shapes human subjectivities and social relations. Haraway [

11], in her seminal

Cyborg Manifesto, disrupts both utopian and dystopian narratives by advancing a relational, hybrid ontology. She envisions human and machine not as distinct, hierarchical entities but as co-constitutive assemblages, mutually shaping one another.

2.5. Anthropocentrism and Relationality

A further critique advanced by posthumanist theorists targets transhumanism’s entrenched anthropocentrism, specifically its relentless focus on enhancing the isolated human subject, often severed from ecological entanglements, other species, and planetary systems. In this frame, the human is positioned as both the primary agent and the ultimate beneficiary of technological progress. Transhumanism remains committed to seeking to make humans more (i.e., more rational, more optimized, more enduring) rather than rethinking what it means to live in relation to nonhuman others.

By contrast, posthumanist thinkers such as Haraway [

11], Braidotti [

12], and Wolfe [

13], foreground relationality, interdependence, and affective entanglement. Haraway [

11], in her notion of

becoming-with, pushes beyond critique to envision new multispecies ontologies based on kinship, partial connections, and shared vulnerability. Braidotti [

12] challenges the centrality of the human by advocating for a posthuman ethics rooted in zoe-centric equality and ecological accountability. Wolfe [

13], drawing from systems theory and philosophy, deconstructs the illusion of the self-contained subject and stresses the constitutive role of nonhuman forces.

Building on these interventions, I argue that transhumanism does not merely overlook relationality; it actively suppresses it [

8]. The figure it valorizes is a corporate self:

optimized,

datafied, and

owned. Its vision of the future is not collective or ecological but atomized and proprietary. This suppression of relationality finds a further analogue in how cognition itself is reimagined in posthumanist thought.

Parisi [

16] deepens the critique of anthropocentrism by theorizing algorithmic cognition as a form of posthuman intelligence that emerges not from human rationality but from nonconscious, computational processes. In her account, cognition is no longer exclusive to human minds; it becomes a distributed function of code, data, and architecture that resists anthropomorphic assumptions. Schank [

17,

18] extends this line of critique by showing how these same algorithmic infrastructures commodify behavior and fragment ethical integrity. His work demonstrates how digital systems displace stable identities and relational accountability, creating environments in which integrity is not merely neglected but systematically eroded by design.

Collectively, these thinkers enact a decisive break from transhumanism’s enhancement-driven individualism. Instead of pursuing mastery over the body or the environment, the posthumanist orientation insists on interdependence, ecological embeddedness, and non-sovereign forms of subjectivity. It is in this space of becoming-with, of algorithmic decentering, of techno-ethical vulnerability that alternatives to transhumanist futures begin to emerge.

2.6. Neoliberal Subjectivity

2.6.1. Neoliberal Self and Enhancement-as-Commodity

Perhaps the most pressing social critique of transhumanism is its reproduction of the neoliberal subject: an individual who is self-responsible, relentlessly self-optimizing, fiercely competitive, and deeply compliant with market imperatives. Enhancement technologies thus shift from mere tools to consumer choices, transforming the body and mind into perpetual sites of productivity, investment, and commodification. This embeds individual bodies within market logics, making self-improvement a form of economic participation shaped by neoliberal values.

2.6.2. Datafied Subject and Platform Capitalism

Scholars such as Dean [

2,

3] have revealed how digital platforms capture and responsibilize desire, reinforcing neoliberal ideals through feedback, surveillance, and behavioral control. Braidotti [

12] critiques this entrepreneurial self as a distortion of posthumanist thought, where selfhood becomes a project of continuous enhancement rather than relational becoming. Corporate techno-governance intricately shapes bodily autonomy by embedding surveillance, feedback, and algorithmic control into everyday biometric and data-driven practices, effectively transforming individuals into datafied subjects whose behaviors and desires are continuously monitored, responsibilized, and regulated within neoliberal infrastructures [

2,

3,

14,

18,

19,

24].

2.6.3. Cyborg: A Critical Counterpoint

Haraway’s [

11] cyborg theory offers a critical counterpoint to this neoliberal trajectory. Rather than accepting the bounded, entrepreneurial self, she proposes a hybrid ontology that resists binary logics such as organic versus technological, human versus machine, and self versus other, exposing how technological embodiment can be either complicit in or resistant to capitalist modes of control. Crucially, her cyborg is not a self-branding subject of market desire but a politically situated figure capable of subverting dominant narratives. Yet transhumanism, by contrast, evacuates this radical potential by folding hybridity into commercial logics of enhancement, optimization, and proprietary control.

2.6.4. Obscured Inequalities and Algorithmic Governance

Dean [

2,

3], Braidotti [

12], and I [

8] have exposed how this logic obscures systemic inequalities, as enhancement remains a privilege accessible only to those with earned or inherited social and economic capital, leaving others behind both materially and symbolically. A dense body of scholarship further supports this critique: Schank [

18] illustrates how algorithmic governance enforces compliance by turning bodies into disciplined data points; Cooper [

21] frames biotechnology as speculative capital within neoliberal markets; Lupton [

23] documents how self-tracking extends neoliberal selfhood through embedded surveillance and discipline; and Pasquale [

24] highlights opaque corporate algorithms that predict and manipulate behavior, further entrenching power asymmetries.

2.6.5. Transhumanism as Incubator of Neoliberal Subjectivity

Building on this extensive evidence, I argue that transhumanism does more than mirror neoliberal subjectivity; it actively incubates and intensifies it. The future human, far from being merely

enhanced, is

licensed,

leased,

branded, and ultimately

owned—a subscription model wrapped in flesh, no longer a sovereign self but a commodified vessel engineered for corporate extraction and recorded as a line item in the ledger of transhuman capital [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. The fantasy of the self-improving posthuman is not one of liberation, but of logistics: a techno-cultural hallucination sustained by the algorithmic machinery of corporate power and market capture.

2.7. Disambiguation of “Posthuman”

The term posthuman is frequently appropriated in conflicting ways, generating confusion and ideological slippage. Transhumanist thinkers such as Kurzweil [

1], Bostrom [

2], and More [

3] envision the posthuman as a technologically enhanced, perfected being who transcends biological limits, essentially extending humanist ideals through technology. Conversely, posthumanist theorists, including Haraway [

11], Braidotti [

12], Wolfe [

13], and Parisi [

18], articulate a different conception. For them, the posthuman is not a superior human but a decentered, distributed, and relational figure embedded within ecological and technological assemblages. This perspective challenges essentialist and progressivist assumptions, disrupting binaries like human/machine and nature/culture.

This fundamental distinction is critical for positioning my own intervention. To clarify ongoing misappropriation,

Table 1 provides a comparative overview of these divergent usages of posthuman in transhumanist and posthumanist perspectives.

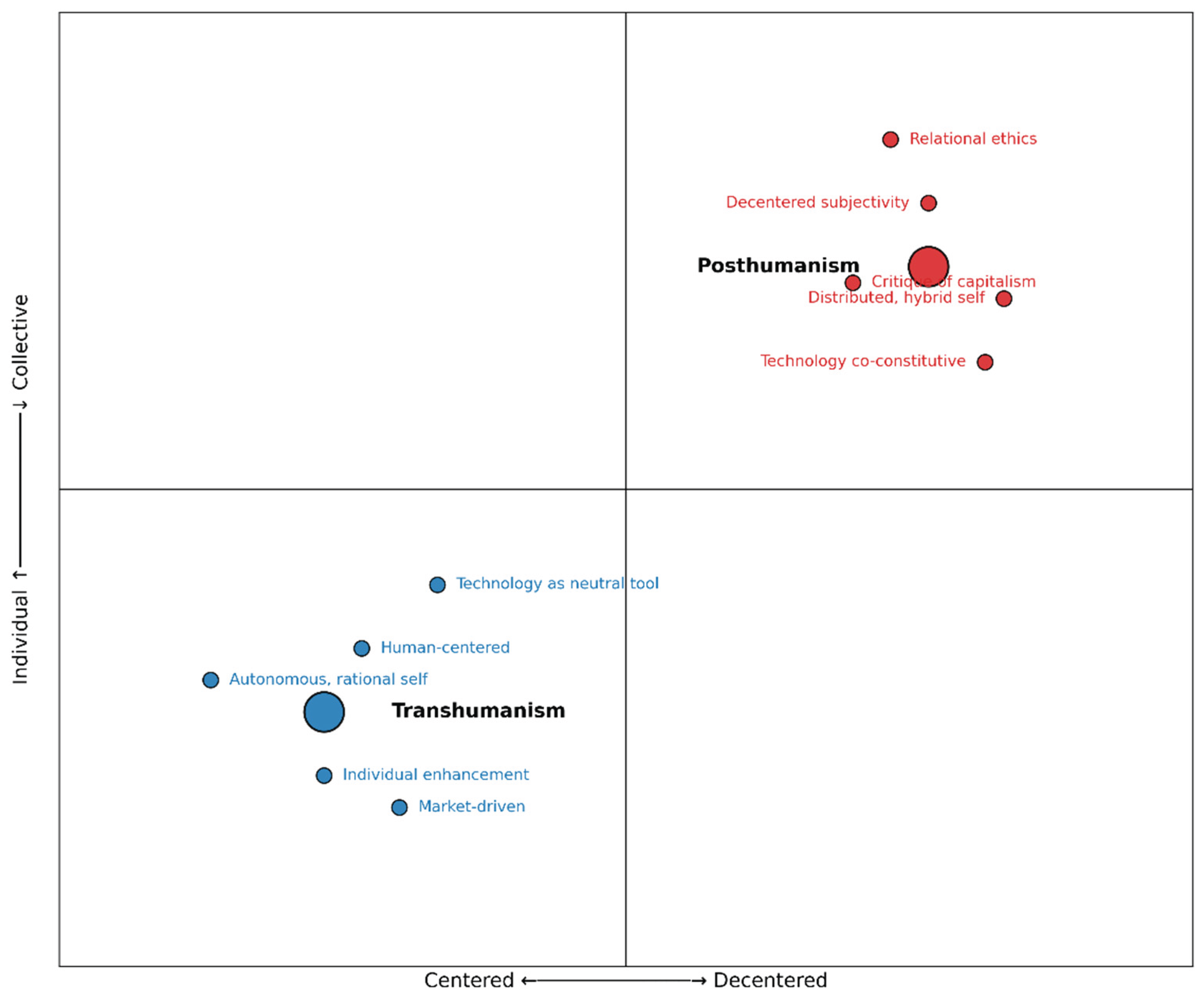

To further clarify the conceptual divergence between transhumanism and posthumanism, I offer a quadrant diagram (

Figure 1) that maps their respective commitments along two intersecting axes: subjectivity (centered vs. decentered) and social orientation (individual vs. collective). This visual aid is not exhaustive, but it illustrates key tensions in how each framework understands the human, the role of technology, and the broader ethical-political stakes. Transhumanism, positioned in the bottom-left quadrant, reflects a commitment to individual enhancement, rational autonomy, and market-aligned techno-optimism. Posthumanism, in contrast, occupies the top-right quadrant, foregrounding decentered subjectivity, relational ethics, and a systemic critique of capitalist infrastructures. The goal of this map is to help readers see how these frameworks are not simply alternatives but oppositional worldviews structured by distinct ontological and political assumptions.

I am not interested in presenting transhumanism as a neutral or purely technological breakthrough. Rather, it is essential to recognize how deeply it is entangled with late-stage capitalism—a system driven by market gains, profit, and power. This history is marked by regulatory failures and government loopholes that allow corporate giants such as Apple, Meta, and Google to shape not only technology but also what it means to be human. These companies do not simply sell products; they construct infrastructures that commodify our bodies and minds, exploiting weak oversight to strengthen their control. Without situating transhumanism within this political and economic context, it is easy to mistake its corporate-driven agenda for genuine progress. In truth, enhancement technologies represent another front in the ongoing logic of extraction, surveillance, and privatization that defines neoliberal governance today.

2.8. Whose Future?

Transhumanism sells a future of longer life, sharper minds, and seamless human-tech integration. But this future is already locked down, monopolized by corporate platforms that control not only our data, but also our desires, identities, and even our bodies. The enhanced human is not free; they are fed, ventilated, and updated by their corporate parents.

Imagine a branded transhuman whose biometric systems are linked to a subscription they can no longer afford. Their neural enhancements begin to lag. Notifications pile up. Then the ventilation halts, not because of a medical failure but because a payment was not processed. In the world transhumanism builds, existence itself becomes a service tier.

Another sits before a forced End User License Agreement (EULA), blinking notice suspended at “I Agree.” Declining means immediate disconnection from their social neural interface. No messages from their children. No shared memories. No presence in the only space where family now gathers. To refuse is to vanish. To agree is to surrender legal rights to their thoughts, behaviors, and biometric expressions. They consent, not out of will, but out of grief and necessity.

These critiques make clear that transhumanism is not a neutral vision of the future. It is a project with philosophical, political, and economic stakes. These stakes are shaped by market and profit imperatives, enabled by regulatory loopholes, and perpetuated through ongoing corporate governance failures. What remains less examined, and what I aim to foreground in the following section, is how these dynamics are not only discursive but also infrastructural. Branded technologies, extractive platforms, and datafied systems are already reshaping what it means to be human. Corporate platforms now govern futures and desires through infrastructural and algorithmic control. They transform individuals into commodities and data points within sprawling ecosystems of surveillance and capital extraction [

8,

9,

10,

11,

16,

19].

3. Illustrative Cases and Extrapolated Futures

To ground the preceding theoretical claims in concrete analysis, this section presents three illustrative cases of platform-human entanglement. I illustrate this logic through three emblematic figures: the Apple Human, the Meta Human, and the Google Human. Each exposes how corporate giants operationalize branded technologies to capture biosubjectivity, regulate affect and behavior, and preconfigure human futures under the logics of extraction and control. Critical analyses conclude each illustration.

3.1. The Apple Human

The Apple Human exemplifies how biometric tracking and health integration have become deeply embedded in everyday life, shaping identity and control through branded ecosystems.

3.1.1. Present: Biometric Tracking and Health Integration

Today’s Apple Human is defined by biometric tracking and intimate health integration. Wearable devices continuously monitor heart rates, sleep patterns, oxygen levels, and a cascade of other bodily metrics. The body becomes a quantified self; an endlessly measured, optimized, and fed back into corporate data streams. This quantified self is not simply about personal health; it forms the foundation of branded biosubjectivity, where identity and value are constructed through subscription-based health ecosystems.

Lupton [

15] demonstrates how self-tracking technologies shape bodily experience and governance, merging health data with identity in ways that obscure structural inequalities. Sadowski [

11] exposes the data infrastructures beneath these devices, showing how they serve as sites of both capital accumulation and behavioral discipline. Cooper [

21] further critiques the health-tech sector by revealing how the commodification of life processes extends neoliberal market logics into the intimate realm of bodily existence.

Media accounts trace this shift from niche biohacking to mainstream normalization. Early adopters who turned their bodies into “medical labs” illustrate the origins of the quantified self movement [

25]. The transformation of biometric monitoring into a ubiquitous everyday practice is well documented [

26]. Critical exposés reveal how Apple’s techno-utopian narratives conceal a broader authoritarian potential embedded within its infrastructure [

27,

28].

3.1.2. Future: Branded Biosubjectivity via Subscription Ecosystems

In the near future, the Apple Human becomes enmeshed in a seamless, yet deeply controlling, ecosystem where life itself is commodified as a service. Beyond mere health tracking, biometric data will be integrated into an elaborate subscription model that governs access to personalized health insights, predictive diagnostics, and life-enhancing medical interventions. The body ceases to be a sovereign entity and transforms into a continuous data stream flowing into proprietary corporate platforms designed to extract surplus value under the guise of wellness and optimization.

Algorithmic systems will monitor and modulate bodily states in real time, nudging users towards prescribed behaviors to maximize health outcomes, but primarily, platform profits. Emotional states and stress levels, derived from biometric signals, will be tracked and subtly shaped, aligning personal well-being with corporate goals. As Cooper [

21], Sadowski [

22], and Lupton [

23] argue, this digital capitalism of biosubjectivity extends market logics into intimate corporeal experience, making human life itself a site of ongoing economic extraction.

Subscription tiers and exclusive licensing agreements will create new inequalities, where access to critical health services and interventions depends on the capacity to pay and comply with opaque EULAs. Pasquale’s [

24] critique of the black box algorithms illustrates how these systems operate beyond user scrutiny, encoding systemic biases and reinforcing socioeconomic disparities. Moreover, EULAs and behavioral use licenses will constrain autonomy, normalizing consent to pervasive data collection and behavioral regulation. Ericson et al. [

19] emphasize how such contracts shape user attitudes and limit meaningful choice, while Contractor et al. [

20] warn that emerging AI governance frameworks may entrench corporate control rather than challenge it.

The Apple Human’s future will see the blurring of boundaries between care and control, wellness and surveillance. Health ecosystems will act as infrastructures of power governing not just bodies but emotions, identities, and social participation. In this future, continued existence depends not only on biology but on the capacity to pay, subscribe, and comply with corporate demands. The enhanced human is not liberated or empowered but trapped within a system that commodifies life itself, turning bodies into platforms and existence into a service controlled by corporate interests.

3.1.3. Critical Analysis

The Apple Human exemplifies how biometric and health tracking technologies serve as instruments of governance under digital capitalism. This integration of bodies into corporate data ecosystems is not simply about health optimization but constitutes a profound reshaping of subjectivity through branded biosubjectivity and subscription-based control. Lupton’s [

15] work on self-tracking highlights how these technologies mediate bodily experience while obscuring broader social inequalities. Sadowski’s [

11] critique of data infrastructures reveals how seemingly personal health data fuels capital accumulation and disciplinary mechanisms. Cooper’s [

21] analysis of life commodification within health tech further underscores the neoliberal extension of market logics into intimate corporeality, transforming bodies into sites of continuous extraction.

Pasquale’s [

24] concept of the black box algorithmic governance is crucial for understanding how opaque systems enforce these controls, embedding biases and reinforcing structural inequalities beneath the veneer of technological innovation. The enforcement of restrictive EULA, as Ericson et al. [

19] demonstrate, limits meaningful user autonomy and consent, entrenching corporate power. Contractor et al. [

20] offer a critical perspective on AI governance frameworks, warning that behavioral use licensing may reinforce existing corporate monopolies rather than enable ethical oversight or user empowerment. This future governance model risks further alienating users, binding their biological existence to corporate subscription services.

This critique aligns with broader concerns in surveillance capitalism as detailed by Zuboff [

29], who shows how intimate data is commodified and behavioral futures sold back to consumers. The Apple Human’s transformation echoes Terranova’s [

30] arguments about the exploitation of emotional and cognitive labor in digital economies, and Berlant’s [

31] insights on affective attachments reveal the political stakes of these technological dependencies. Further enriching this analysis, Sedgwick [

32] and Ahmed [

33] explore how affect circulates culturally and politically, while Massumi [

34] and Seigworth and Gregg [

35] reveal the preconscious dynamics of affect that underpin these embodied governance systems. Hardt and Negri [

36] connect these mechanisms to neoliberal global power structures, and Probyn’s [

37] examination of shame and vulnerability deepens understanding of the emotional regulation embedded within corporate platforms. Together, these critiques illuminate the Apple Human as a figure trapped within a corporate ecosystem that commodifies life itself, transforming health and identity into algorithmically mediated products, and ultimately reinforcing socio-economic hierarchies under the guise of wellness and technological progress.

3.2. The Meta Human

The Meta Human reveals how immersive digital platforms govern affect, behavior, and social realities through algorithmic control.

3.2.1. Present: Oculus and Horizon Worlds

The Meta Human emerges through immersive platforms like Oculus and Horizon Worlds, where affective experience and social interaction are governed by algorithmic design. Meta’s virtual environments do more than connect users; they capture emotional responses, shape behavior, and mediate political discourse on an unprecedented scale. Dean [

2] highlights how immersive platforms capture affect, transforming human emotions into data for continuous extraction. Pasquale [

24] reveals the black box society within these digital spaces, where opaque systems determine interaction and visibility. Morozov [

5] critiques Meta’s techno-utopian aspirations, warning that beneath the promise of immersive freedom lies a latent infrastructure of authoritarian control.

Media investigations document the real-world consequences of Meta’s governance. The

New York Times [

38] details Facebook’s facilitation of the Capitol riot, showing how platform affordances enable political mobilization that destabilizes democratic processes. The

Guardian [

39] demonstrates how Facebook’s algorithm amplifies authoritarian content, shaping collective affect and political attitudes. Whistleblower reports [

40] expose internal research revealing harm to teen mental health caused by unchecked design choices in Meta’s immersive systems. Scholarly analysis [

41] confirms that Meta governs emotional, political, and economic behavior at a platform-wide scale, while Senate hearings [

42] record repeated failures to moderate misinformation and disinformation effectively.

Contextualized by long-form journalism from

The Atlantic [

43] and

The New Yorker [

44], these developments illustrate the convergence of platform capitalism and techno-authoritarianism. Meta’s virtual environments do not simply host social life; they manufacture it, embedding behavioral norms and affective cues into every interface. These systems function as infrastructures of governance, operating under the guise of innovation while advancing the political economy of surveillance and control.

3.2.2. Future: Algorithmic Intimacy and Affective Control

Meta’s platforms capture your heartache, your pleasure, your pain, your folly, depersonalize your emotions, your experiences, your life, and then sell them back as personalized content. One person’s unique suffering becomes everyone’s shared burden, transformed into a commodified currency that shapes how millions feel and behave. Individuality fades while collective vulnerability swells.

Inside immersive worlds like Horizon Worlds, your relationships, your politics, and your desires become data points routed through platforms that watch and score your feelings in real time. Your self shrinks to an interface, your moods tracked, your preferences nudged, and your choices shaped by predictive systems designed to maximize engagement, compliance, and profit. Dean’s [

2] analysis of feedback loops shows how these platforms turn affect into raw material for endless extraction, while Pasquale’s [

24] concept of the black box society reveals the hidden power of algorithms governing your inner life.

Meta’s affective control extends beyond individual nudging to full-spectrum governance of emotional life. Meta’s systems read your gaze, your voice tone, and your biometric signals to make your subjectivity programmable and governable. Political dissent or emotional difference, for example, a muted reaction in a virtual meeting or an ambiguous emoji, can trigger downgrades or social exile. Participation becomes the price of access to work, school, and social belonging, making emotional conformity a form of economic control.

Recent innovations further entrench this model. Meta’s standalone AI app, launched in April 2025, integrates with platforms like WhatsApp, Instagram, Facebook, and Messenger [

45]. Powered by the LLaMA 4 model, the app offers personalized interactions, including voice capabilities and real-time memory, creating a more intimate and continuous user experience [

45,

46]. The app’s “Discover” feed encourages sharing of AI interactions, raising concerns about privacy and commodification of personal experiences.

Meta’s [

47] hAI! Friend MR app for Meta Quest delivers AI companions designed for emotional support and personalized interaction in VR and AR spaces. These companions blur the line between genuine human connection and algorithmic affect while being subtly puppeteered by Meta’s corporate marketing machinery. Users are nudged to deepen their emotional investments through monetized interactions (such as gifting, virtual “sugar baby” dynamics, or Valentine’s Day offerings to their AI romantic partners) transforming intimacy into a platform for continuous consumer extraction.

3.2.3. Critical Analysis

This future signals a profound shift: AI companions are no longer mere tools but emotional actors within a surveillance economy. Meta’s orchestration of affect commodifies and recycles human subjectivity itself into platform capital, encouraging addictive relational loops that generate profit. This echoes Schafheitle et al.’s [

4] warnings about datafication reshaping social control and Morozov’s [

5] critique of techno-solutionism masking systemic power imbalances. It also resonates with Zuboff’s [

29] concept of surveillance capitalism, which details how behavioral futures are predicted, modulated, and sold back to users, transforming intimate experiences into data assets. Complementing Berlant’s [

31] focus on affective attachments and political optimism, Terranova’s [

30] work on digital labor highlights how emotional and cognitive effort is exploited under neoliberal regimes. Further enriching this analysis, Sedgwick [

32] and Ahmed [

33] explore the cultural circulation of affect and emotion, while Massumi [

34] and Seigworth and Gregg [

35] illuminate the nonconscious dynamics that animate affective politics. Hardt and Negri [

36] connect these affective economies to broader global neoliberal power structures, and Probyn’s [

37] examination of vulnerability and shame adds depth to understanding how affective life is regulated within corporate platforms.

3.3. The Google Human

The Google Human navigates a world shaped by predictive systems that anticipate needs, behaviors, and decisions, embedding anticipatory governance into daily life.

3.3.1. Present: Predictive Platforms and Everyday Navigation

The Google Human lives within a seamless web of services (i.e., Gmail, Maps, Search, Assistant, Calendar) all synchronized to anticipate and guide action. Google’s infrastructure captures queries, habits, locations, and timing patterns, creating an up-to-date behavioral map of each user. This predictive capacity transforms everyday conveniences into deep forms of behavioral governance.

Zuboff [

29] identifies this as the extraction of

behavioral surplus, where user data is repurposed to predict, and eventually preempt future behavior. What begins as personalized assistance becomes algorithmic nudging: suggested routes, autocomplete phrases, calendar prompts, and targeted ads all guide the user toward profitable outcomes. Parisi [

18] explains this as computational rationality, where decision-making is refracted through pre-processed models that make acting otherwise increasingly improbable.

Google is a planetary infrastructure as part of a multi-layered system of sovereignty that reshapes civic, geographic, and perceptual realities [

49]. Journalistic and long-form reporting underscore this shift. Wired [x] and Public Seminar [x] document how Google Maps reshapes human geography, redefining not just how people move but how they conceptualize space. Google’s AI-driven suggestions in Gmail and Android predict actions and emotional tone, while critics [x] warn of overreach in emotion recognition and mental health detection.

3.3.2. Future: Algorithmic Captivity in The Stack

Imagine living as the Google Human in a future where every step, every choice, and every interaction is pre-judged by opaque algorithms steeped in racial bias and corporate control. You face digital redlining. Not through explicit laws but via coded discrimination embedded deep within platforms that shape your access to jobs, housing, healthcare, and essential services. Your neighborhood is algorithmically gerrymandered: surveillance cameras and sensors watch your every move, while predictive policing algorithms mark you as a future threat, ushering in preemptive incarceration before any crime is committed.

Much like travelers once guided by

The Negro Motorist Green Book [

48], you navigate a fractured cityscape where “safe” spaces are algorithmically gated, leaving you confined to digital and physical enclaves deemed acceptable by corporate-state powers. Your identity, reduced to data points, is constantly scored and ranked—your digital shadow controlling everything from the ads you see to whether you qualify for social programs or bail.

This fractured lived experience unfolds across Benjamin H. Bratton’s planetary-scale computational megastructure;

The Stack [

49], which enforces racialized control at every level:

- a)

Earth layer: The physical environment sustaining this system is violently extracted, disproportionately burdening marginalized communities whose land and resources power the infrastructure that oppresses them. Environmental degradation and toxic waste perpetuate histories of ecological racism, grounding digital sovereignty in real-world extraction and violence [

4,

50,

51,

52].

- b)

Cloud layer: Google’s centralized data centers hoard your personal information, transforming it into behavioral futures markets. Predictive models systematically assign greater risk to Black and Brown bodies, digitally recreating the boundaries of historic redlining through biased machine learning [

29,

53,

54]. Your potential actions become commodities traded in opaque marketplaces, defining your possibilities before you act [

5].

- c)

City layer: Smart urban systems enforce digital apartheid. Sensors, cameras, and biometric scanners partition the city into surveilled zones, algorithmically gerrymandering neighborhoods by social desirability and predicted compliance [

22,

55,

56]. You navigate an algorithmically curated cityscape restricting your mobility and access.

- d)

Address layer: Identification systems like facial recognition misidentify people of color with alarming frequency, feeding you into pre-crime incarceration systems [

11,

57,

58,

59]. This is not about past behavior but anticipated futures, a racialized surveillance regime cloaked in data science, criminalizing potential rather than actions [

41].

- e)

Interface layer: Google’s platforms regulate your speech and social interactions. Content moderation algorithms nudge conformity and silence dissent, erasing marginalized voices while amplifying sanitized narratives that serve corporate and state interests [

60,

61,

62]. Interfaces become tools of political and cultural control [

4,

24].

- f)

User layer: Your subjectivity is fragmented into quantifiable metrics [

23]. Autonomy is hollowed out as your behavior is predicted, scored, and regulated. Freedom becomes conditional, contingent on algorithmic approval [

62]. Sovereignty, once a claim of self-determination, erodes into a state of managed participation without consent [

60].

In this world we find ourselves in, the Google Human lives under anticipatory governance where algorithms not only predict behavior but enforce it, shaping social life with chilling precision. Algorithmic sovereignty replaces people and states as the ultimate arbiters of inclusion and exclusion. Access to resources, mobility, and freedom are rationed by invisible lines drawn in code rather than law, perpetuating a digital reincarnation of racialized governance practices like redlining and gerrymandering.

The ghosts of that earlier era persist not in printed guides but encoded within opaque algorithms deciding who moves, who belongs, and who is confined. Within The Stack, the Google Human is trapped inside a planetary computational apparatus surveilling, controlling, and preemptively punishing along lines of race and class, turning autonomy into a myth and liberty into an algorithmically engineered performance.

3.3.3. Critical Analysis

The figure of the Google Human reveals a cybernetic intensification of interlocking systems of oppression through anticipatory governance. Predictive algorithms operate as adaptive feedback loops that continuously monitor, regulate, and constrain human behavior across multiple infrastructural layers, generating recursive cycles of control and resistance [

1,

2,

4]. This intensification embeds racialized and class-based power asymmetries into the core of digital architectures, transforming autonomy into a managed performance within algorithmic regimes.

Fundamentally reconfigured by predictive computation, autonomy is subsumed into systems that anticipate, nudge, and ultimately constrain decision-making. Computational rationality describes how individual choices become increasingly preprocessed by algorithmic models, narrowing possibilities and making deviation structurally improbable [

14,

63]. Behavioral surplus extraction converts intimate human practices into data commodities, extending neoliberal logics into everyday life [

2,

26,

29].

The Stack [

48] is critical here for understanding t how these layers interlock to produce the Google Human as a subject embedded in a planetary computational megastructure. The Earth layer’s violent extraction reproduces environmental racism, disproportionately burdening marginalized communities and establishing a material base for digital sovereignty [

48,

49,

50]. The Cloud layer’s centralized data centers and opaque algorithmic futures markets perpetuate digital redlining, encoding racial bias into machine learning systems that reinscribe segregation in computational terms [

25,

28,

29,

53]. These biases are structurally embedded, systemically disadvantaging Black and Brown bodies [

56,

57].

The City layer partitions urban space into surveilled enclaves controlled through predictive policing and smart infrastructure technologies. Algorithmic gerrymandering creates digital apartheid zones that gatekeep safety and opportunity, restricting mobility and access [

48,

54,

58]. The Address layer compounds injustices with biometric misidentifications and pre-crime incarceration algorithms that punish anticipated futures rather than past actions, extending state control through data-driven anticipation [

56,

57,

58].

At the Interface layer, platforms mediate social interaction via content moderation and algorithmic curation, silencing dissenting and marginalized voices while amplifying sanitized narratives aligned with corporate and state interests [

3,

59,

60]. These processes function as technologies of political and cultural control, shaping public discourse and eroding democratic deliberation. The User layer reduces subjectivity to quantifiable metrics via behavioral scores, affective captures, and predictive profiles that hollow out autonomy and condition participation within algorithmic power structures [

4,

26,

29].

Together, these layers reveal that Google’s platform infrastructures do not merely facilitate or enhance life; they actively incubate, govern, and commodify it. The Google Human becomes a site of managed, datafied existence where freedom depends on compliance with algorithmic governance [

2,

25,

29,

48]. This process rearticulates liberal sovereignty as a cybernetic mechanism of control, shifting the locus of power from states to techno-conglomerates that invisibly govern inclusion and exclusion [

1,

48,

53]. Cybernetic feedback loops embedded within anticipatory governance systems intensify structural inequalities by preempting behaviors and shaping lived realities through computational rationality and behavioral commodification. The Google Human lives constrained agency, simultaneously empowered and trapped by the planetary megastructure.

4. Conceptual Reflection: Platform Sovereignty and the Human OS

4.1. Attention and Affect Extraction

The contemporary human operating system (OS) is embedded within a sprawling platform ecosystem whose power extends far beyond mere technology. It functions as a comprehensive apparatus of attention and affect extraction, where human desires, emotions, and social interactions are systematically harvested and converted into commodified data streams. Platforms deploy algorithmic architectures specifically designed to capture and monetize user attention at scale, feeding complex cross-industry markets spanning advertising, healthcare, finance, and beyond. This dynamic enmeshes users within an endless cycle of consumption and engagement, where affect becomes a resource mined for profit, blurring the boundaries between subjectivity and capital.

4.2. Socioeconomic Stratification and Unequal Access

Crucially, this attention economy intersects with socioeconomic stratification. Access to enhancement technologies, datafied infrastructures, and biometric governance is unevenly distributed, reproducing and exacerbating existing social inequalities. Those with greater economic capital gain privileged entry into the branded transhumanist futures, while marginalized communities face exclusion or coerced participation under surveillance regimes that amplify precarity. Thus, the human OS is not a neutral or universal platform but one marked by hierarchical inclusion and exclusion based on class, race, gender, ability, and other axes of difference.

4.3. Cross-Industry Consumer Marketing and Corporate Ecosystems

At the core of this ecosystem lies a relentless consumer marketing logic, which incentivizes corporate stakeholders across multiple industries to align their interests. Health tech companies, insurance providers, wellness startups, and social media platforms form symbiotic relationships to capture value from user data and behavioral patterns. This cross-industry stakeholder network fuels an expansive marketplace where bodily and cognitive enhancement are not only individual choices but tightly bound to ongoing consumerism, subscription models, and proprietary ecosystems that lock users into corporate control.

4.4. Branding, Brand Loyalty, and Kinship Dynamics

An extension of this marketing logic is the strategic use of branding and brand loyalty, which profoundly shapes social relations, kinship, and heritage. Platforms and corporations cultivate generational brand attachments, effectively locking entire families into lifelong ecosystems of consumption and data extraction. This branding goes beyond products or services; it determines who can be your friends, your social circle, and even who can be recognized as kin. By embedding familial and social identity within branded environments, corporations enforce generational entrapment, extracting wealth, data, and loyalty across time, thus reproducing social hierarchies and corporate dominion through the fabric of personal and collective identity.

4.5. Democratic Erosion and Corporate Governance

Such platform sovereignty poses profound threats to democratic life. The collapse of democracy emerges as these corporate platforms, operating with minimal regulatory oversight, mediate public discourse, shape political imaginaries, and surveil dissident voices. The privatization of critical infrastructures results in policy capture, where corporate interests supersede public good. This undermines collective deliberation and accountability, eroding the conditions necessary for meaningful democratic participation. As political power migrates into opaque algorithmic systems, the future of self-governance becomes precarious.

4.6. Discrimination, Eugenics, and Algorithmic Policing

Embedded within this dystopian vision are stark discriminations of bodies and identities. The ideal datafied subject promoted by transhumanist and platform logics embodies racialized, gendered, able-bodied, and normative ideals. Algorithmic biases reinforce systemic exclusions by shaping who gains access to enhancements and whose data is deemed valuable. This perpetuates historical patterns of marginalization and exclusion, now mechanized through coded infrastructures that invisibly police and discipline bodies that deviate from corporate norms.

This dynamic extends into a contemporary form of eugenics, where datafication and enhancement converge to engineer an ideal subject optimized for market efficiency and governance. Biometric monitoring, predictive analytics, and algorithmic decision-making collectively enforce standards of productivity, health, and comportment that echo exclusionary logics of bodily perfection and social worth. The human is no longer a sovereign individual but a calibrated entity molded to fit neoliberal imperatives, with profound ethical and political implications for autonomy and justice.

4.7. Access, Predictive Control, and Intergenerational Impact

Access also defines life trajectories in this ecosystem. Control over access to information, employment, and opportunity is intimately tied to one’s branded identity and data profile. When an individual is branded, for example, as a thief or otherwise socially marginalized, these labels cascade down generations. Their children become subjects of predictive control regimes that preemptively monitor and restrict them based on presumed criminality or deviance. This form of algorithmic policing extends beyond individuals to entire families, effectively criminalizing and limiting the futures of descendants through datafied stigmatization, entrenching cycles of exclusion and social control.

4.8. Policing Through Biometric and Algorithmic Infrastructures

Policing of subjects occurs both through overt surveillance and more insidious infrastructural controls embedded in everyday technologies. Corporate platforms enforce compliance by regulating biometric data streams, shaping behavioral feedback loops, and constraining participation in digitally mediated social spaces. This governance regime blurs the lines between state and corporate power, embedding disciplinary mechanisms that monitor, classify, and correct individuals within a panoptic network that stretches from social media to health trackers to workplace monitoring systems.

5. Conclusion: Beyond the Branded Human

Transhumanism, far from heralding a liberatory posthuman future, functions as an intensified extension of liberal humanism deeply embedded within neoliberal capitalism. The figure of the enhanced human is not an emancipated posthuman subject but a corporately branded and datafied entity, optimized for market participation and governed by infrastructures of surveillance and control. This cybernetic subject is tethered to platform capitalism’s logic of commodification, responsibilization, and algorithmic governance, where autonomy is recast as continuous self-optimization within corporate ecosystems. Transhumanism’s promises of transcendence and liberation are thus inseparable from neoliberal market imperatives and the privatization of embodied existence. By contrast, posthumanist critiques illuminate the limits of this vision, emphasizing relationality, hybridity, and ecological embeddedness as grounds for alternative modes of subjectivity.

Recognizing the full complexity of this ecosystem is essential to envisioning possibilities for collective agency amidst corporate extraction, inequality, and governance. Through open-source initiatives, policy demands for transparency and equity, and reimaginings of subjectivity that embrace relationality over commodification, cracks appear in the dominant system. These openings suggest the human OS can be disrupted and reconfigured, nurturing futures that resist extraction, eugenic logics, and reinstate democratic accountability.

Within these openings lies a site of transgression where refusal, collective action, and alternative techno-ethical imaginaries confront corporate capture and neoliberal biopolitics. Acts of disobedience, technopolitical hacking, and multispecies kinship destabilize proprietary subjectivities and cultivate relational modes of becoming-with. Moving beyond enhancement-as-commodity, these practices foster shared vulnerability, ecological accountability, and the reconfiguration of techno-social relations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, ENSL; methodology, ENSL; software, ENSL; validation, ENSL; formal analysis, ENSL; investigation, ENSL; resources, ENSL; data curation, ENSL; writing—original draft preparation, ENSL; writing—review and editing, ENSL; visualization, ENSL; supervision, ENSL; project administration, ENSL; funding acquisition, ENSL. The sole author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Easy Does It Counseling, p.c., a 501(c)(3) teletherapy practice, where the author serves as Founding Clinical Director. The practice provided financial support in the form of salary, as well as essential resources including computational infrastructure, statistical software, qualitative analysis tools, testing materials, and administrative assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 |

Apple Inc., founded in 1976, is a multinational technology company headquartered in Cupertino, California. It is known for its consumer electronics, including the iPhone, iPad, and Mac; as well as its software ecosystem and digital services. |

| 2 |

Meta Platforms, Inc., originally founded as Facebook in 2004, is a technology conglomerate based in Menlo Park, California. It is focused on social media products and the development of immersive digital environments known as the metaverse. |

| 3 |

Google LLC, founded in 1998 and now a subsidiary of Alphabet Inc., is a technology company headquartered in Mountain View, California. It is best known for its search engine, digital advertising services, Android operating system, and cloud-based tools. |

References

- Lockhart ENS. Reflexive examination of IWSC(HAT)P through cybernetics. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy. 2025;37(1-2):62–71. [CrossRef]

- Dean J. Blog theory: feedback and capture in the circuits of drive. Polity; 2010.

- Dean J. Publicity’s secret: how technoculture capitalizes on democracy. Cornell University Press; 2002.

- Schafheitle S, Weibel A, Ebert I, Kasper G, Schank C, Leicht-Deobald U. No stone left unturned? Towards a framework on the impact of datafication technologies on organizational control. Academy of Management Discoveries. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Morozov E. To save everything, click here: the folly of technological solutionism. PublicAffairs; 2013.

- Barbrook R, Cameron A. The Californian ideology. Mute Magazine. 1995. Available from: https://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/californian-ideology (accessed on 3 April 2000).

- Edwards PN. The closed world: computers and the politics of discourse in Cold War America. MIT Press; 1996.

- Kurzweil R. The singularity is near: when humans transcend biology. Viking Press; 2005.

- Bostrom N. Superintelligence: paths, dangers, strategies. Oxford University Press; 2014.

- More M. The philosophy of transhumanism. In: More M, Vita-More N (editors). The transhumanist reader: classical and contemporary essays on the science, technology, and philosophy of the human future. Wiley-Blackwell; 2013. pp. 3–17.

- Haraway D. A cyborg manifesto: science, technology, and socialist-feminism in the late twentieth century. In: Simians, cyborgs, and women: the reinvention of nature. Routledge; 1991. pp. 149–181.

- Braidotti R. The posthuman. Polity; 2013.

- Wolfe C. What is posthumanism? University of Minnesota Press; 2010.

- Fiesler C. Lawful users: copyright circumvention and legal constraints on technology use. In: Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; April 2020; Honolulu, HI, USA. pp. 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Lindtner S, Hertz GD, Dourish P. Emerging sites of HCI innovation: hackerspaces, hardware startups, and incubators. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; April 2014; Toronto, Canada. pp. 439–448. [CrossRef]

- Parisi L. Contagious architecture: computation, aesthetics, and space. MIT Press; 2013.

- Schank C. Die Digitalisierung als Herausforderung für die persönliche Integrität. Zeitschrift für Wirtschafts- und Unternehmensethik. 2019;(20)2:176-201. [CrossRef]

- Schank C. Algorithmen und ihr Einfluss auf Compliance und Integrity. In: Bertelsmann Stiftung; Wittenberg-Zentrum für Globale Ethik (Hrsg.). Unternehmensverantwortung im digitalen Wandel. Ein Debattenbeitrag zu Corporate Digital Responsibility. Bertelsmann Stiftung: Gütersloh; 2020. pp. 123–133.

- Ericson JD, Albert WS, Bernard BP, Brown E. End-user license agreements (EULAs): investigating the impact of human-centered design on perceived usability, attitudes, and anticipated behavior. Information Design Journal. 2021;26(3):193–215. [CrossRef]

- Contractor D, McDuff D, Haines JK, Lee J, Hines C, Hecht B, Vincent N, Li H. Behavioral use licensing for responsible AI. In: Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency; 2022; Seoul, South Korea. pp. 778–788. [CrossRef]

- Cooper M. Life as surplus: biotechnology and capitalism in the neoliberal era. University of Washington Press; 2008.

- Sadowski J. Too smart: how digital capitalism is extracting data, controlling our lives, and taking over the world. MIT Press; 2020.

- Lupton D. The quantified self: a sociology of self-tracking. Polity; 2016.

- Pasquale F. The black box society: the secret algorithms that control money and information. Harvard University Press; 2015.

- Guardian Staff. Self-tracking: the people turning their bodies into medical labs. The Guardian, 24 November 2012. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2012/nov/24/self-tracking-health-wellbeing-smartphones (accessed on 24 November 2012).

- MedTech Pulse Staff. Quantified self: The long path from fringe into mainstream health. MedTech Pulse, 29 June 2022. Available online: https://www.medtechpulse.com/article/insight/quantified-self-the-long-path-from-fringe-into-mainstream-health/ (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Atlantic Staff. The rise of techno-authoritarianism. The Atlantic, 1 March 2024. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2024/03/facebook-meta-silicon-valley-politics/677168/ (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- New Yorker Staff. The dark side of techno-utopianism. The New Yorker, 30 September 2019. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/09/30/the-dark-side-of-techno-utopianism (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Zuboff S. The age of surveillance capitalism: the fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. PublicAffairs; 2019.

- Terranova T. Network culture: politics for the information age; Pluto Press; 2004.

- Berlant L. Cruel optimism. Duke University Press; 2011.

- Sedgwick EK. Touching feeling: affect, pedagogy, performativity. Duke University Press; 2003.

- Ahmed S. The cultural politics of emotion. Edinburgh University Press; 2004.

- Massumi B. Parables for the virtual: movement, affect, sensation. Duke University Press; 2002.

- Seigworth GJ, Gregg M. An inventory of shimmers: affect, sensation, and politics. In: The affect theory reader; Gregg M, Seigworth GJ, editors. Duke University Press; 2010. p. 1–25.

- Hardt M, Negri A. Empire. Harvard University Press; 2000.

- Probyn E. Blush: faces of shame. University of Minnesota Press; 2005.

- Isaac M., Frenkel S. Facebook’s role in the Capitol riot: What we learned. The New York Times. 2021, 1 March. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/01/technology/facebook-capitol-riot.html (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Hill K. How Facebook’s algorithm boosts authoritarianism. The Guardian. 2023, 5 February. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/feb/05/facebook-algorithm-authoritarianism (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Hern A. Facebook whistleblower reveals internal research showing harm to teen girls. The Guardian. 2021, 25 September. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/sep/25/facebook-whistleblower-reveals-internal-research-showing-harm-to-teen-girls (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Sweeney M., et al. Platform surveillance and algorithmic governance: Facebook’s role in shaping public discourse. Journal of Digital Media & Policy. 2024;15(1):43–61. [CrossRef]

- United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. Examination of social media platforms’ role in the spread of misinformation. Senate Hearing; 2021, 8 October. Available online: https://www.commerce.senate.gov/2021/10/examination-of-social-media-platforms-role-in-the-spread-of-misinformation (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Atlantic Staff. The rise of techno-authoritarianism. The Atlantic. 2024, 1 March. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2024/03/facebook-meta-silicon-valley-politics/677168/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- New Yorker Staff. The dark side of techno-utopianism. The New Yorker. 2019, 30 September. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/09/30/the-dark-side-of-techno-utopianism (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Business Insider. (2025, June 11). Mark Zuckerberg has created the saddest place on the internet with Meta AI’s public feed. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/mark-zuckerberg-meta-ai-chatbot-discover-feed-depressing-why-2025-6 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Meta. (2025, April 29). Meta AI: a new way to access your AI assistant. Available online: https://about.fb.com/news/2025/04/introducing-meta-ai-app-new-way-access-ai-assistant/ (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- URAV Advanced Learning Systems Pvt Ltd. (2025, March 17). hAI! Friend MR. Available online: https://www.altlabvr.com/hai-friend-vr (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Green VH. editor. The Negro motorist green book: an international travel guide. Victor H. Green & Company; 1949.

- Bratton BH. The stack: on software and sovereignty. The MIT Press; 2026.

- Bullard RD. Dumping in Dixie: race, class, and environmental quality. Routledge; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mohai P, Pellow D, Roberts JT. Environmental justice. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 2019;34:405–30. [CrossRef]

- Carley S, Konisky DM, Decker CS. Justice and sustainability in the energy transition: public acceptance of energy systems in disadvantaged communities. Nature Energy. 2021;6(2):141–9.

- Crawford K, Paglen T. Excavating AI: the politics of training sets for machine learning. AI & Society. 2021;36(4):1027–36.

- Benjamin R. Race after technology: abolitionist tools for the new Jim Code. Polity; 2019.

- Kitchin R. The data revolution: big data, open data, data infrastructures and their consequences. Sage; 2020.

- Monahan T. Surveillance in the time of insecurity. Rutgers University Press; 2021.

- Garvie C, Bedoya A, Frankle J. The perpetual line-up: unregulated police face recognition in America. Georgetown Law Center on Privacy & Technology; 2016.

- Raji ID, Buolamwini J. Actionable auditing: investigating the impact of publicly naming biased performance results of commercial AI products. Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Brayne S. Predict and surveil: data, discretion, and the future of policing. Oxford University Press; 2021.

- Gillespie T. Custodians of the internet: platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. Yale University Press; 2020.

- Roberts ST. Behind the screen: content moderation in the shadows of social media. Yale University Press; 2019.

- Tufekci Z. Algorithmic harms beyond Facebook and Google: emergent challenges of computational agency. Colorado Technology Law Journal. 2018;16(1):203–18.

- Liao Y-C, Holz C. Redefining affordance via computational rationality. Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces. 2025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).