Submitted:

24 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Intensification of Harmful Cyanobacteria Blooms (HCB)

1.2. Shallow Lakes Are Hotspots for HCB

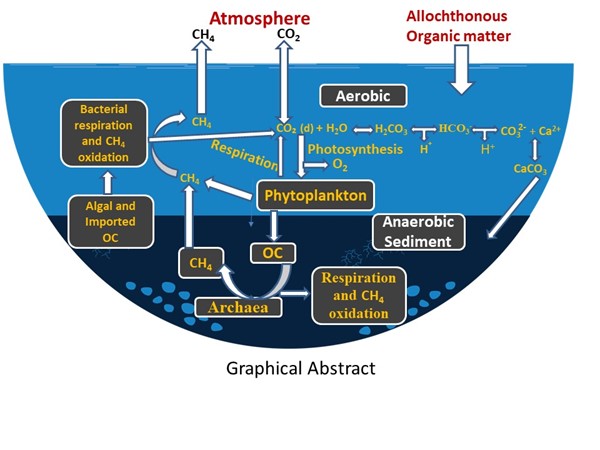

2. Sequestration of Organic C

2.1. Are Lakes a Source or a Sink of CO₂?

2.2. Burial Efficiency (BE) of Organic Carbon

2.3. Distinguishing Factors in Carbon BE: Lakes vs. Oceans

2.3.1. Exposure to Oxygen and the Temperature

2.3.2. Density of the Phytoplankton Biomass

2.4. Sequestration of Organic Carbon in the Marine and Freshwater Bodies

2.5. Can Mitigation of Phytoplankton Blooms in Freshwater Bodies Be Used for Substantial Carbon Burial?

3. The Fate of Inorganic Carbon in the Marine- and Fresh- Waterbodies

3.1. The CO₂-Concentrating Mechanisms (CCMs)

3.2. Calcification Processes

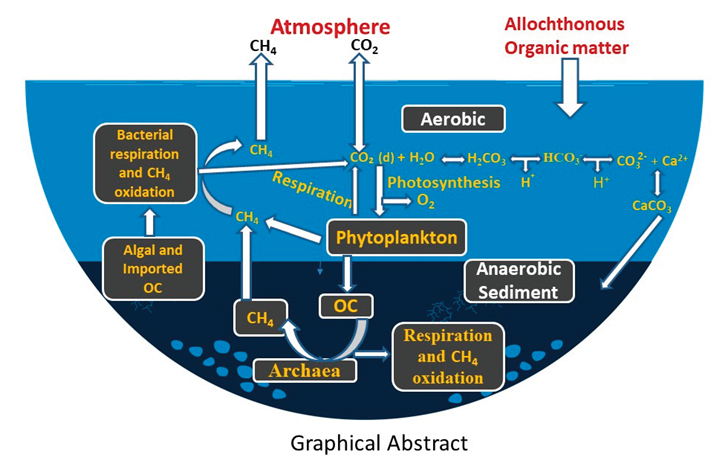

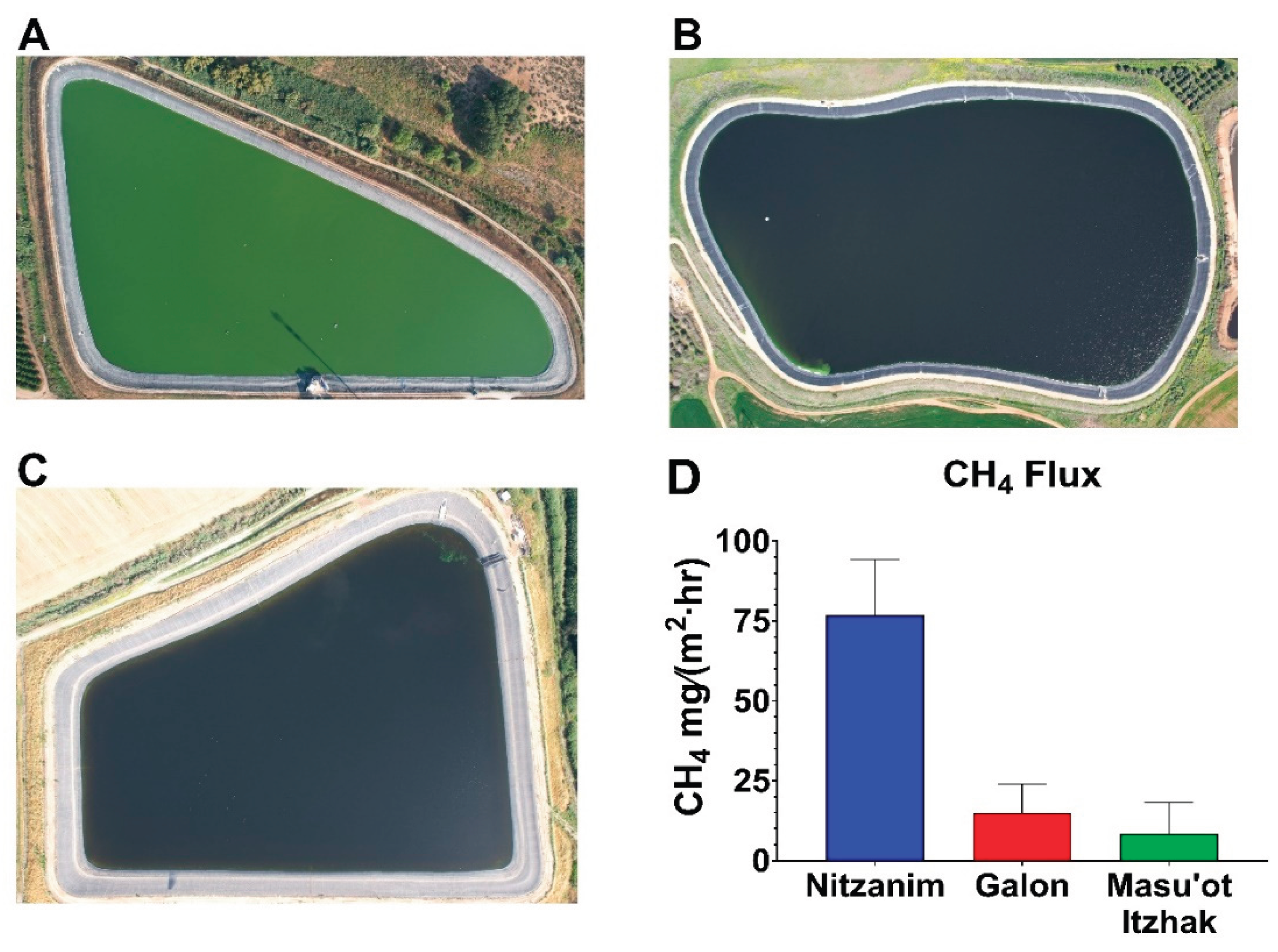

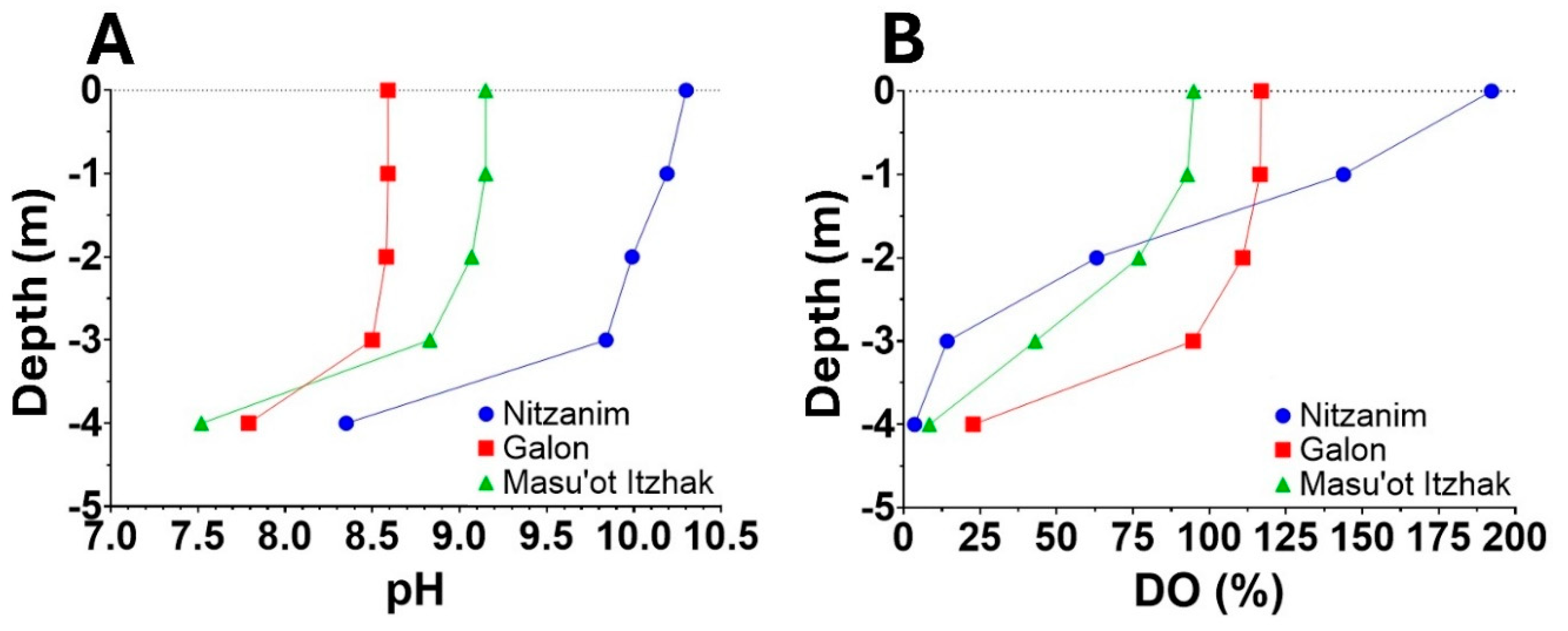

4. The Methane Enigma

4.1. Methane Biosynthesis

The Methane Paradox

4.2. Methane Consumption

4.3. Can HCB Mitigation Reduce Methane Emissions?

5. Nitrous Oxide in Freshwater Bodies

6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Griscom, B.W.; Adams, J.; Ellis, P.W.; Houghton, R.A.; Lomax, G.; Miteva, D.A.; Schlesinger, W.H.; Shoch, D.; Siikamäki, J.V.; Smith, P.; et al. Natural climate solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad.Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11645–11650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Wang, Y.; Hou, X.; Qin, B.; Kuster, T.; Qu, F.; Chen, N.; Paerl, H.W.; Zheng, C. Harmful algal blooms in inland waters. Nat. Rev. Earth & Environm. [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Qin, B.; Zhang, Q.; Paerl, H.W.; Van Dam, B.; Jeppesen, E.; Zeng, C. Global lake phytoplankton proliferation intensifies climate warming. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, P.M.; Verspagen, J.M.H.; Sandrini, G.; Stal, L.; Matthijs, H.C.P.; Davis, T.W.; Paerl, H.W.; Huisman, J. How rising CO2 and global warming may stimulate harmful cyanobacterial blooms. Harmful Algae.

- Sukenik, A.; Kaplan, A. Cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms in aquatic ecosystems: A comprehensive outlook on current and emerging mitigation and control approaches. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, D.; Thiery, W.; Mercado-Bettín, D.; Xiong, L.; Xia, J.; Woolway, R.I. Enhanced heating effect of lakes under global warming. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, E.E.; Lauber, T.; van den Hoogen, J.; Donmez, A.; Bain, R.E.S.; Johnston, R.; Crowther, T.W.; Julian, T.R. Mapping safe drinking water use in low- and middle-income countries. Science, /: 784–790, https.

- Kaplan, A.; Harel, M.; Kaplan-Levy, R.N.; Hadas, O.; Sukenik, A.; Dittmann, E. The languages spoken in the water body (or the biological role of cyanobacterial toxins). Front aquatic Microbiol, /: https. [CrossRef]

- Gantar, M.; Berry, J.P.; Thomas, S.; Wang, M.; Perez, R.; Rein, K.S. Allelopathic activity among Cyanobacteria and microalgae isolated from Florida freshwater habitats. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008, 64, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberhaus, L.; Briand, J.-F.; Humbert, J.-F. Allelopathic growth inhibition by the toxic, bloom-forming cyanobacterium Planktothrix rubescens. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008, 66, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Li, J.; Hu, J.; An, G.; Wang, C. Deciphering the joint intracellular and extracellular regulatory strategies of toxigenic Microcystis to achieve intraspecific competitive advantage: An integrated multi-omics analysis with novel allelochemicals identified. Water Res. 2025, 283, 123774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel, M.; Weiss, G.; Lieman-Hurwitz, J.; Gun, J.; Lev, O.; Lebendiker, M.; Temper, V.; Block, C.; Sukenik, A.; Zohary, T.; et al. Interactions between Scenedesmus and Microcystis may be used to clarify the role of secondary metabolites. Environm. Microbiol. Rep. 2013, 5, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardi, A.; Schatz, D.; Beeri, K.; Motro, U.; Sukenik, A.; Levine, A.; Kaplan, A. Dinoflagellate-cyanobacterium communication may determine the composition of phytoplankton assemblage in a mesotrophic lake. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12, 1767–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukenik, A.; Eshkol, R.; Livne, A.; Hadas, O.; Rom, M.; Tchernov, D.; Vardi, A.; Kaplan, A. Inhibition of growth and photosynthesis of the dinoflagellate Peridinium gatunense by Microcystis sp. (cyanobacteria): a novel allelopathic mechanism. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2002, 47, 1656–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, P.; Wu, H.; Pan, M.; Cao, G.; Wu, X.; Tian, C.; Wang, C.; Xiao, B. Eutrophication amplifies Microcystis response to increasing winter temperatures, intensifying winter blooms. J. Appl. Phycol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, P.; Cai, Q.; He, F.; Huang, Y.; Tian, C.; Wu, X.; Wang, C.; Xiao, B. Flexibility of Microcystis overwintering strategy in response to winter temperatures. Microorganisms 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunberg, A.-K.; Blomqvist, P. Benthic overwintering of Microcystis colonies under different environmental conditions. J. Plank. Res. 2002, 24, 1247–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinl, K.L.; Harris, T.D.; North, R.L.; Almela, P.; Berger, S.A.; Bizic, M.; Burnet, S.H.; Grossart, H.-P.; Ibelings, B.W.; Jakobsson, E.; et al. Blooms also like it cold. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 2023, 8, 546–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressac, M.; Laurenceau-Cornec, E.C.; Kennedy, F.; Santoro, A.E.; Paul, N.L.; Briggs, N.; Carvalho, F.; Boyd, P.W. Decoding drivers of carbon flux attenuation in the oceanic biological pump. Nature 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, N.Z.; Luo, T.W.; Chen, Q.R.; Zhao, Z.; Xiao, X.L.; Liu, J.H.; Jian, Z.M.; Xie, S.C.; Thomas, H.; Herndl, G.J.; et al. The microbial carbon pump and climate change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falkowski, P.; Scholes, R.J.; Boyle, E.; Canadell, J.; Canfield, D.; Elser, J.; Gruber, N.; Hibbard, K.; Hogberg, P.; Linder, S.; et al. The global carbon cycle: A test of our knowledge of earth as a system. Science 2000, 290, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DelSontro, T.; Beaulieu, J.J.; Downing, J.A. Greenhouse gas emissions from lakes and impoundments: Upscaling in the face of global change. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 2018, 3, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, J.J.; DelSontro, T.; Downing, J.A. Eutrophication will increase methane emissions from lakes and impoundments during the 21st century. Nature Commun. 2019, 10, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, J.J.; Waldo, S.; Balz, D.A.; Barnett, W.; Hall, A.; Platz, M.C.; White, K.M. Methane and carbon dioxide emissions from reservoirs: Controls and upscaling. J. Geophys. Res.:Biogeos. [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, J.; Nakayama, K.; Komai, K.; Kubo, A.; Shimizu, T.; Omori, J.; Uno, K.; Fujii, T. Carbon dioxide uptake in a eutrophic stratified reservoir: Freshwater carbon sequestration potential. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobek, S.; Durisch-Kaiser, E.; Zurbrügg, R.; Wongfun, N.; Wessels, M.; Pasche, N.; Wehrli, B. Organic carbon burial efficiency in lake sediments controlled by oxygen exposure time and sediment source. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2243. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Nie, X.; Li, Z.; Ran, F.; Yang, C.; Xiao, T. Quantification of sedimentary organic carbon sources in a landeriverelake continuum combined with multi-fingerprint and un-mixing models. Intnl. J. Sedim. Res.

- Du, Z.; Wang, L.; Xie, S.; Yang, J.; Yan, F.; Li, C.; Ding, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, X.; Xiao, C. Carbon dioxide and methane fluxes in different waterbodies in Inexpressible Island, Ross Sea, East Antarctica. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 213, 117703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel, M.; Weiss, G.; Daniel, E.; Wilenz, A.; Hadas, O.; Sukenik, A.; Sedmak, B.; Dittmann, E.; Braun, S.; Kaplan, A. Casting a net: fibres produced by Microcystis sp. in field and laboratory populations. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2012, 4, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco-Morgado, M.; Amador-Espejo, G.G.; Pérez-Cortés, M.; Gutiérrez-Uribe, J.A. Microalgae and cyanobacteria polysaccharides: Important link for nutrient recycling and revalorization of agro-industrial wastewater. Appl. Food Res. 2023, 3, 100296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Philippis, R.; Vincenzini, M. Exocellular polysaccharides from cyanobacteria and their possible applications. FEMS Microbiol Rev 1998, 22, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; De Philippis, R. Role of cyanobacterial exopolysaccharides in phototrophic biofilms and in complex microbial mats. Life (Basel, Switzerland) 2015, 5, 1218–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, F.; Wang, H.; Shen, C.; Yu, K. Meta-analysis of abiotic conditions affecting exopolysaccharide production in cyanobacteria. Metabolites 2025, 15, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcolombri, U.; Peaudecerf, F.J.; Fernandez, V.I.; Behrendt, L.; Lee, K.S.; Stocker, R. Sinking enhances the degradation of organic particles by marine bacteria. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yi, S.; Wang, M. Biomimetic mineralization for carbon capture and sequestration. Carbon Capt. Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Gu, P.; Zhu, W.; Jing, C.; He, J.; Yang, X.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, Z. Effects of cyanobacterial accumulation and decomposition on the microenvironment in water and sediment. J. Soils Sedim. 2020, 20, 2510–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, G.; Krause, S.M.B.; Bodelier, P.L.E.; Meima-Franke, M.; Pitombo, L.; Irisarri, P. Interactions between cyanobacteria and methane processing microbes mitigate methane emissions from rice soils. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Zhao, M.; Song, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, N. Characteristics of extracellular organic matters and the formation potential of disinfection by-products during the growth phases of M. aeruginosa and Synedra sp. Environm. Sci. Poll. Res. 2022, 29, 14509–14521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fu, H.; Yu, J.; Su, Y.; Liu, Z. Geochemical characteristics of n-alkanes in sediments from oligotrophic and eutrophic phases of five lakes and potential use as paleoenvironmental proxies. CATENA 2023, 220, 106682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobek, S.; Gudasz, C.; Koehler, B.; Tranvik, L.J.; Bastviken, D.; Morales-Pineda, M. Temperature dependence of apparent respiratory quotients and oxygen penetration depth in contrasting lake sediments. Geophys. Res.: Biogeosci. 3076. [Google Scholar]

- Pavia, F.J.; Anderson, R.F.; Lam, P.J.; Cael, B.B.; Vivancos, S.M.; Fleisher, M.Q.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Cheng, H.; Edwards, R.L. Shallow particulate organic carbon regeneration in the South Pacific Ocean. Proc Natl Acad USA, 9753. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.H.; Knauer, G.A.; Karl, D.M.; Broenkow, W.W. ;. VERTEX: carbon cycling in the Northeast Pacific. Deep Sea Res. 1987, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, J.P.; Sarmiento, J.L.; Gnanadesikan, A. A synthesis of global particle export from the surface ocean and cycling through the ocean interior and on the seafloor. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycl. 2007, 21, GB4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.J.; Heathcote, A.J.; Engstrom, D.R.; contributors, G.d. Anthropogenic alteration of nutrient supply increases the global freshwater carbon sink. Sci Adv 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, R.; Kosten, S.; Sobek, S.; Cardoso, S.J.; Figueiredo-Barros4, M.P.; Estrada, C.H.D.; Roland, F. Organic carbon burial efficiency in a large tropical hydroelectric reservoir. Biogeosci. Dis. 2015, 12, 18513–18540. [Google Scholar]

- Clow, D.W.; Stackpoole, S.M.; Verdin, K.L.; Butman, D.E.; Zhu, Z.; Krabbenhoft, D.P.; Striegl, R.G. Organic carbon burial in lakes and reservoirs of the conterminous United States. Environ. Sci. Technol 2015, https. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallistova, A.Y.; Kosyakova, A.I.; Rusanov, II; Kadnikov, V. V.; Beletsky, A.V.; Koval, D.D.; Yusupov, S.K.; Zekker, I.; Pimenov, N.V. Methane production in a temperate freshwater lake during an Intense cyanobacterial bloom. Microbiology 2023, 92, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, G.; Gao, G. Eutrophication control of large shallow lakes in China. Sci. Total Environm. 2023, 881, 163494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhao, D.; Hu, C.; Xu, W.; Anderson, D.M.; Li, Y.; Song, X.P.; Boyce, D.G.; Gibson, L.; et al. Coastal phytoplankton blooms expand and intensify in the 21st century. Nature 2023, 615, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paerl, H.W.; Gardner, W.S.; Havens, K.E.; Joyner, A.R.; McCarthy, M.J.; Newell, S.E.; Qin, B.; Scott, J.T. Mitigating cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms in aquatic ecosystems impacted by climate change and anthropogenic nutrients. Harmful Algae 2016, 54, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phlips, E.J.; Badylak, S.; Milbrandt, E.C.; Stelling, B.; Arias, M.; Armstrong, C.; Behlmer, T.; Chappel, A.; Foss, A.; Kaplan, D.; et al. Fate of a toxic Microcystis aeruginosa bloom introduced into a subtropical estuary from a flow-managed canal and management implications. J. Environm. Manag. 2025, 375, 124362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geider, R.J.; MacIntyre, H.L.; Kana, T.M. Dynamic model of phytoplankton growth and acclimation: Responses of the balanced growth rate and the chlorophyll a:carbon ratio to light, nutrient-limitation and temperature. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1997, 148, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.S. The Ecology of Phytoplankton.; Cambridge University Press. ISBN: 978-0521605199. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, M.; Ma, S.; Su, J.; He, K.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S. From cyanobacteria to kerogen: A model of organic carbon burial. Precam. Res. 2023, 390, 107035–107145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dynarski, K.A.; Bossio, D.A.; Scow, K.M. Dynamic Stability of Soil Carbon: Reassessing the “Permanence” of Soil Carbon Sequestration. Front. Environmen. Sci. /: https. [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, T.; Gotanda, K.; Haraguchi, T.; Danhara, T.; Yonenobu, H.; Brauer, A.; Yokoyama, Y.; Tada, R.; Takemura, K.; Staff, R.A.; et al. SG06, a fully continuous and varved sediment core from Lake Suigetsu, Japan: Stratigraphy and potential for improving the radiocarbon calibration model and understanding of late Quaternary climate changes. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2012, 36, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Bali, B.m.S.; Muneer, W.; Ali, S.N.; Morthekai, P.; Wani, A.H.; Sabreena; Ganai, B. A. Deciphering source, degradation status and temporal trends of organic matter in a himalayan freshwater lake using multiproxy indicators, optically stimulated luminescence dating and time series forecasting. Sci.Total Environm. 2024, 957, 177618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zastepa, A.; Taranu, Z.E.; Kimpe, L.E.; Blais, J.M.; Gregory-Eaves, I.; Zurawell, R.W.; Pick, F.R. Reconstructing a long-term record of microcystins from the analysis of lake sediments. Sci. Total Environm. 2017, 579, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, G.I.; Tani, Y.; Seto, K.; Tazawa, T.; Yamamuro, M.; Watanabe, T.; Nakamura, T.; Takemura, T.; Imura, S.; Kanda, H. Holocene paleolimnological changes in Lake Skallen Oike in the Syowa Station area of Antarctica inferred from organic components in a sediment core (Sk4C-02). J. Paleolimnol. 2010, 44, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engstrom, D.R.; Schottler, S.P.; Leavitt, P.R.; Havens, K.E. A reevaluation of the cultural eutrophication of Lake Okeechobee using multiproxy sediment records. Ecol. Appl. 2006, 16, 1194–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Block, B.; Jessup, B.; Salk, K.; >, P. ; >, P.;. Estimates of sediment accumulation rates and bottom core ages in Northeast Lakes. U.S. Environm. Prot. Agency, Washington, DC, /: https, 3612. [Google Scholar]

- Joarder, M.S.A.; Islam, M.S.; Hasan, M.H.; Sadman- Anjum, J.; Kabir, M.F.; Rashid, F.; Joarder, T.A. A comprehensive review of carbon dioxide capture, transportation, utilization, and storage: a source of future energy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.R.; Cao, H.S.; Zheng, J.; Teng, F.; Wang, X.J.; Lou, K.; Zhang, X.H.; Tao, Y. Suppression of water-bloom cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa by algaecide hydrogen peroxide maximized through programmed cell death. J. Hazard. Mat. 1016. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.C.; Yu, S.M.; Hu, J.; Effiong, K.; Ge, Z.W.; Tang, T.; Xiao, X. Programmed cell death process in freshwater Microcystis aeruginosa and marine Phaeocystis globosa induced by a plant derived allelochemical. Sci.Total Environm. 2022, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Li, J.; Li, T.; Sha, J.; Liu, J.; Li, L.; Dai, G.; Jia, Y.; Song, L. Unveiling the susceptibility mechanism of Microcystis to consecutive sub-lethal oxidative stress—Enhancing oxidation technology for cyanobacterial bloom control. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 480, 135993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zaman, F.; Jia, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, T.; Bai, F.; Li, L.; Song, L.; Li, J. Harmful cyanobacterial bloom control with hydrogen peroxide: Mechanism, affecting factors, development, and prospects Curr. Poll. Rep. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinley-Baird, C.; Calomeni, A.; Berthold, D.E.; Lefler, F.W.; Barbosa, M.; Rodgers, J.H.; Laughinghouse, H.D. Laboratory-scale evaluation of algaecide effectiveness for control of microcystin-producing cyanobacteria from Lake Okeechobee, Florida (USA). Ecotoxicol. Environm. Saf. 2021, 207, 111233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandrini, G.; Piel, T.; Xu, T.S.; White, E.; Qin, H.J.; Slot, P.C.; Huisman, J.; Visser, P.M. Sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide of the bloom-forming cyanobacterium Microcystis PCC 7806 depends on nutrient availability. Harm. Algae 2020, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, B.M.; Jones, G.J.; Orr, P.T. Cellular microcystin content in N-limited Microcystis aeruginosa can be predicted from growth rate. Appl. Environm. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badger, M.R.; Price, G.D. CO2 concentrating mechanisms in cyanobacteria: molecular components, their diversity and evolution. J. Exp. Bot. 2003, 54, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnap, R.L.; Hagemann, M.; Kaplan, A. Regulation of the CO2 concentrating mechanism in cyanobacteria. Life 2015, 5, 348–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, A.; Reinhold, L. CO2 concentrating mechanisms in photosynthetic microorganisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol.ar Biol. 1999, 50, 539–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raven, J.A. Inorganic carbon concentrating mechanisms in relation to the biology of algae. Photosynth. Res. 2003, 77, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucius, S.; Hagemann, M. The primary carbon metabolism in cyanobacteria and its regulation. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1417680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, M.; Beardall, J.; Raven, J.A. CO2 concentrating mechanisms in algae:: Mechanisms, environmental modulation, and evolution. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2005, 56, 99–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandrini, G.; Matthijs, H.C.P.; Verspagen, J.M.H.; Muyzer, G.; Huisman, J. Genetic diversity of inorganic carbon uptake systems causes variation in CO2 response of the cyanobacterium Microcystis. ISME J 2014, 8, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.F.; Qiu, B.S. The CO2-concentrating mechanism in the bloom-forming cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa (Cyanophyceae) and effects of UVB radiation on its operation. J. Phycol. 2007, 43, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchewitz, T.; Guljamow, A.; Meissner, S.; Timm, S.; Henneberg, M.; Baumann, O.; Hagemann, M.; Dittmann, E. Non-canonical localization of RubisCO under high-light conditions in the toxic cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa PCC7806. Environm. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 4836–4851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guljamow, A.; Barchewitz, T.; Grosse, R.; Timm, S.; Hagemann, M.; Dittmann, E. Diel Variations of Extracellular Microcystin Influence the Subcellular Dynamics of RubisCO in Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7806. Microorganisms 2021, 9, https. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Guljamow, A.; Dittmann, E. Impact of temperature on the temporal dynamics of microcystin in Microcystis aeruginosa PCC7806. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1200816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilliges, Y.; Kehr, J.C.; Meissner, S.; Ishida, K.; Mikkat, S.; Hagemann, M.; Kaplan, A.; Borner, T.; Dittmann, E. The cyanobacterial hepatotoxin microcystin binds to proteins and increases the fitness of Microcystis under oxidative stress conditions. Plos One 2011, 6, e17615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schatz, D.; Keren, Y.; Vardi, A.; Sukenik, A.; Carmeli, S.; Boerner, T.; Dittmann, E.; Kaplan, A. Towards clarification of the biological role of microcystins, a family of cyanobacterial toxins. Environm. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teikari, J.E.; Russo, D.A.; Heuser, M.; Baumann, O.; Zedler, j.A.Z.; Liaimer, A.; Dittmann, E. Competition and interdependence define interactions of Nostoc sp. and Agrobacterium sp. under inorganic carbon limitation. NPJ Biofilms Microbiom. 2025, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raven, J.A. Distribution and Functions of Calcium Mineral Deposits in Photosynthetic Organisms. In Progress in Botany Vol. 84, Lüttge, U., Cánovas, F.M., Risueño, M.-C., Leuschner, C., Pretzsch, H., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 293–326. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A.R.; Brownlee, C.; Wheeler, G. Coccolithophore cell biology: Chalking up progress. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2017, 9, 283–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinou, C.; Wang, Y. ;. Unlocking the potential of microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation (MICP) for hydrological applications: A beview of opportunities, challenges, and environmental considerations. Hydrology. [CrossRef]

- Gaëtan, J.; Halary, S.; Millet, M.; Bernard, C.; Duval, C.; Hamlaoui, S.; Hecquet, A.; Gugger, M.; Marie, B.; Mehta, N.; et al. Widespread formation of intracellular calcium carbonates by the bloom-forming cyanobacterium Microcystis. Environm. Microbiol. 2023, 25, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.L.; Zhao, L.; Li, G.K.; Zhu, C.; Xu, D.; Ji, J.F.; Chen, J. Assessment and selection of cyanobacterial strains for CO2 mineral sequestration: implications for carbonation mechanism. Geomicrobiol. J. 2023, 40, 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Marcé, R.; Laas, A.; Obrador, B. The relevance of pelagic calcification in the global carbon budget of lakes and reservoirs Limnetica. 41, /: https. [CrossRef]

- Riebesell, U.; Zondervan, I.; Rost, B.; Tortell, P.D.; Zeebe, R.E.; Morel, F.M.M. Reduced calcification of marine plankton in response to increased atmospheric CO2. Nature 2000, 407, 364–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruley, A.; Gaëtan, J.; Gugger, M.; Pancrace, C.; Millet, M.; Gaschignard, G.; Dezi, M.; Humbert, J.-F.; Leloup, J.; Skouri-Panet, F.; et al. Diel changes in the expression of a marker 1 gene and candidate genes for intracellular 2 amorphous CaCO3 biomineralization in 3 Microcystis Peer Comm. J. 2024, 5, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, N.; Gaëtan, J.; Giura, P.; Azaïs, T.; Benzerara, K. Detection of biogenic amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC) formed by bacteria using FTIR spectroscopy. Spect. Acta Part a-Mol. Biomol. Spect. 2022, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fruchter, N.; Lazar, B.; Nishri, A.; Almogi-Labin, A.; Eisenhauer, A.; Be'eri Shlevin, Y.; Stein, M. 88Sr/86Sr fractionation and calcite accumulation rate in the Sea of Galilee. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2017, 215, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escoffier, N.; Perolo, P.; Many, G.; Pasche, N.T.; Perga, M.-E. Fine-scale dynamics of calcite precipitation in a large hardwater lake. Sci. Total Environm. 2023, 864, 160699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiser, R.; Jongsma, R.; Bakenhus, I.; Möckel, R.; Philipp, B.; Neu, T.R.; Wendt-Potthoff, K. Interaction of cyanobacteria with calcium facilitates the sedimentation of microplastics in a eutrophic reservoir. Water Res. 2021, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Many, G.; Escoffier, N.; Perolo, P.; Bärenbold, F.; Bouffard, D.; Perga, M.-E. Calcite precipitation: The forgotten piece of lakes’ carbon cycle. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eado5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, A.E.; Eadie, B.J. Satellite observations of calcium carbonate precipitations in the Great Lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1978, 23, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küchler-Krischun, J.; Kleiner, J. Heterogeneously nucleated calcite precipitation in Lake Constance. A short time resolution study. Aquatic Sci. 1990, 52, 176–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.B.; Cheng, H.M.; Gao, K.S.; Qiu, B.S. Inactivation of Ca2+/H+ exchanger in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 promotes cyanobacterial calcification by upregulating CO2-concentrating mechanisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 4048–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansson, C.; Northen, T. Calcifying cyanobacteria—the potential of biomineralization for carbon capture and storage. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2010, 21, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Burnap, R.L. Action at a distance: The remarkable coupling of CO2 uptake to electron transfer in specialized cyanobacterial NDH-1 complexes PNAS in press 2025.

- Tchernov, D.; Hassidim, M.; Luz, B.; Sukenik, A.; Reinhold, L.; Kaplan, A. Sustained net CO2 evolution during photosynthesis by marine microorganisms. Curr. Biol. 1997, 7, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGowan, H.; Lensky, N.; Abir, S.; Shaked, Y.; Wurgaft, E. Direct measurement of CO2 air-sea exchange over a desert Fringing coral rReef, Gulf of Eilat (Aqaba), Israel. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 2022, 127, e2022JC018548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, W.E. The carbon cycle and biogeochemical dynamics in lake sediments. J. Paleolimnol. 1999, 21, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepernick, B.N.; Gann, E.R.; Martin, R.M.; Pound, H.L.; Krausfeldt, L.E.; Chaffin, J.D.; Wilhelm, S.W. Elevated pH Conditions Associated With Microcystis spp. Blooms Decrease Viability of the Cultured Diatom Fragilaria crotonensis and Natural Diatoms in Lake Erie. Front. Microbiol. [CrossRef]

- Nishri, A.; Stiller, M.; Rimmer, A.; Geifman, Y.; Krom, M. Lake Kinneret (The Sea of Galilee): the effects of diversion of external salinity sources and the probable chemical composition of the internal salinity sources. Chem. Geol. 1999, 158, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Shen, Q.; Gu, X.; Zhang, L.; Han, C.; Wang, Z. Burial or mineralization: Origins and fates of organic matter in the water–suspended particulate matter–sediment of macrophyte- and algae-dominated areas in Lake Taihu. Water Res. 2023, 243, 120414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Neil, J.R. Theoretical and experimental aspects of isotopic fractionation. In: Stable isotopes in high temperature geological processes (ed. J. W. Valley et al.) Rev. Mineral. 1986, 16, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, A.; Nishri, A. Calcium, magnesium and strontium cycling in stratified, hardwater lakes: Lake Kinneret (Sea of Galilee), Israel. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2013, 105, 372–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wu, C.; Xie, D.; Ma, J. Sources, migration, transformation, and environmental effects of organic carbon in eutrophic lakes: A critical review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Penga, Y.; Zhou, M.; Jiaa, R.; Bud, H.; Xua, X.; Chen, L.; Mag, J.; Kinouchi, B.; Wang, G. Cyanobacteria decay alters CH4 and CO2 produced hotspots along vertical sediment profiles in eutrophic lakes Water Research 2024, 265, 122319. 265, 122319. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, I.F.; Günthel, M.; Klintzsch, T.; Kirillin, G.; Grossart, H.-P.; Keppler, F.; Isenbeck-Schröter, M. High spatiotemporal dynamics of methane production and emission in oxic surface water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1451. [Google Scholar]

- Rocher-Ros, G.; Stanley, E.; Loken, L.; Raymond, P.; Liu, S.; Sponseller, R. Global methane emissions from rivers and streams. Nature 2023, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosentreter, J.A.; Borges, A.V.; Deemer, B.R.; Holgerson, M.A.; Liu, S.; Song, C.; Melack, J.; Raymond, P.A.; Duarte, C.M.; Allen, G.H.; et al. Half of global methane emissions come from highly variable aquatic ecosystem sources. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgerson, M.A.; Raymond, P.A. Large contribution to inland water CO2 and CH4 emissions from very small ponds. Nat. Geosci. 2016, 9, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend-Small, A.; Disbennett, D.; Fernandez, J.M.; Ransohoff, R.W.; Mackay, R.; Bourbonniere, R.A. Quantifying emissions of methane derived from anaerobic organic matter respiration and natural gas extraction in Lake Erie. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2016, 61, S356–S366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kh-Hriiziirou, M.; Khoiyangbam, R.S. Strategies for CH4 Emission Reduction from Lakes: Understanding the Key Driving Factors for CH4 Production and Lake Restoration Intnl. j. Lakes Rivers. 2024, 17, 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Lew, S.; Burandt, P.; Glińska-Lewczuk, K. Microbial Communities Drive Methane Fluxes From Floodplain Lakes—A Hydrological Gradient Perspective. Environm. Microbiol. 2025, 27, e70127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hounshell, A.G.; D’Acunha, B.M.; Breef-Pilz, A.; Johnson, M.S.; Thomas, R.Q.; Carey, C.C. Eddy covariance data reveal that a small freshwater reservoir emits a substantial amount of carbon dioxide and methane. J.Geophys. Res.: Biogeosci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldo, S.; Beaulieu, J.J.; Barnett, S.W.; Balz, D.A.; Vanni4, M.J.; Williamson, T.; Walker, J.T. Temporal trends in methane emissions from a small eutrophic reservoir: the key role of a spring burst. Biogeosciences, 2021, 18, 5291–5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jentzsch, K.; van Delden, L.; Fuchs, M.; Treat, C.C. An expert survey on chamber measurement techniques for methane fluxes. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2024, 2024, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiticar, M. Carbon and hydrogen isotope systematics of bacterial formation and oxidation of methane. J. Chem. Geol. 1999, 161, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerbin, S.; Pérez, G.; Rybak, M.; Wejnerowski, Ł.; Konowalczyk, A.; Helmsing, N.; Naus-Wiezer, S.; Meima-Franke, M.; Pytlak, Ł.; Raaijmakers, C.; et al. Methane-derived carbon as a driver for cyanobacterial growth. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroll, M.; Liu, L.; Einzmann, T.; Keppler, F.; Grossart, H.-P. Methane accumulation and its potential precursor compounds in the oxic surface water layer of two contrasting stratified lakes. Sci. Total Environm. 2023, 903, 166205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bižić, M.; Klintzsch, T.; Ionescu, D.; Hindiyeh, M.Y.; Günthel, M.; Muro-Pastor, M.A.; Eckert, W.; Urich, T.; Keppler, F.; Grossart, H.-P. Aquatic and terrestrial cyanobacteria produce methane. Science Advances, 5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.X.; Zhou, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.Y.; Tang, X.X. Effect of CO2-induced seawater acidification on growth, photosynthesis and inorganic carbon acquisition of the harmful bloom-forming marine microalga, Karenia mikimotoi. Plos One 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klintzsch, T.; Geisinger, H.; Wieland, A.; Langer, G.; Nehrke, G.; Bizic, M.; Greule, M.; Lenhart, K.; Borsch, C.; Schroll, M.; et al. Stable carbon isotope signature of methane released from phytoplankton. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, https. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizic, M. Phytoplankton photosynthesis: an unexplored source of biogenic methane emission from oxic environments. J. Plankton Res. 2021, 43, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.X.; Lian, J.C.; Liu, B.; Zhu, X.W.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, L.J.; Tan, F.X.; Wu, D.J.; Liang, H. Integrated ferrate and calcium sulfite to treat algae-laden water for controlling ultrafiltration membrane fouling: High-efficiency oxidation and simultaneous cell integrity maintaining. Chem. Engin. J. 2023, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepernick, B.N.; Hart, L.N.; Chase, E.E.; Natwora, K.E.; Obuya, J.A.; Olokotum, M.; Houghton, K.A.; Kiledal, E.A.; Achieng, D.; Barker, K.B.; et al. Molecular investigation of harmful cyanobacteria reveals hidden risks and niche partitioning in Kenyan Lakes. Harmful Algae 2024, 140, 102757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Gao, G.; Berman-Frank, I.; Bizic, M.; Gao, K. Light-dependent methane production by a coccolithophorid may counteract its photosynthetic contribution to carbon dioxide sequestration. Commun. Earth & Environm. 2024, 5, 695. [Google Scholar]

- Khatun, S.; Iwata, T.; Kojima, H.; Fukui, M.; Aoki, T.; Mochizuki, S.; Naito, A.; Kobayashi, A.; Uzawa, R. Aerobic methane production by planktonic microbes in lakes. Sci.Total Environm. 2019, 696, https. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazi, S.; Amalfitano, S.; Venturi, S.; Pacini, N.; Vazquez, E.; Olaka, L.A.; Tassi, F.; Crognale, S.; Herzsprung, P.; Lechtenfeld, O.J.; et al. High concentrations of dissolved biogenic methane associated with cyanobacterial blooms in East African lake surface water. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, S.S.; Williams, H.J.; Dangott, L.J.; Chakrabarti, M.; Raushel, F.M. The catalytic mechanism for aerobic formation of methane by bacteria. Nature 2013, https. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repeta, D.J.; Ferrón, S.; Sosa, O.A.; Johnson, C.G.; Repeta, L.D.; Acker, M.; DeLong, E.F.; Karl, D.M. Marine methane paradox explained by bacterial degradation of dissolved organic matter. Nat. Geosci. 2016, 9, 884–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.L.; Li, H.; Tang, Z.Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; He, Q. Underestimated methane production triggered by phytoplankton succession in river-reservoir systems: Evidence from a microcosm study. Water Res. 2020, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lin, L.-Z.; Chen, M.-Y.; Teng, W.-K.; Zheng, L.-L.; Peng, L.; Lv, J.; Brand, J.J.; Hu, C.-X.; Han, B.-P.; et al. The widespread capability of methylphosphonate utilization in filamentous cyanobacteria and its ecological significance. Water Res. 2022, 217, 118385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dummer, N.F.; Willock, D.J.; He, Q.; Howard, M.J.; Lewis, R.J.; Qi, G.; Taylor, S.H.; Xu, J.; Bethell, D.; Kiely, C.J.; et al. Methane oxidation to methanol. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 6359–6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Peng, Y.; Yua, M.; Deng, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, L.; Xua, X.; Zhang, S.; Yanb, Y.; Wang, G. Severe cyanobacteria accumulation potentially induces methylotrophic methane producing pathway in eutrophic lakes. Environm. Poll. 2022, 292, 118443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zheng, X.; Wang, D.; Yao, E.; Li, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhong, J. Significant diurnal variations in nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions from two contrasting habitats in a large eutrophic lake (Lake Taihu, China). Environm. Res. 2024, 261, 119691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, J.M.; Townsend-Small, A.; Zastepa, A.; Watson, S.B.; Brandes, J.A. Methane and nitrous oxide measured throughout Lake Erie over all seasons indicate highest emissions from the eutrophic Western Basin. J. Great Lakes Res. 2020, 46, 1604–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, B.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, N.; Paerl, H.W.; Wang, T.; Hong, W.; Penuelas, J.; Qian, H. Potential health risk assessment of cyanobacteria across global lakes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, e01936–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, P.J.; Niedzielski, J.J. Nitrous oxide production by cyanobacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 1986, 146, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabisik, F.; Guieysse, B.; Procter, J.; Plouviez, M. Nitrous oxide (N2O) synthesis by the freshwater cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa. Biogeosciences 2023, 20, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Lao, Q.; Chen, C.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, F. The impact of algal blooms on promoting in-situ N2O emissions: A case in Zhanjiang bay, China. J. Environm. Manag. 2024, 358, 120935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plouviez, M.; Shilton, A.; Packer, M.A.; Guieysse, B. Nitrous oxide emissions from microalgae: potential pathways and significance. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roothans, N.; Pabst, M.; van Diemen, M.; Herrera Mexicano, C.; Zandvoort, M.; Abeel, T.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Laureni, M. Long-term multi-meta-omics resolves the ecophysiological controls of seasonal N2O emissions during wastewater treatment. Nat. Water 2025, 3, 590–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Palmero, E.; Morales-Baquero, R.; Thamdrup, B.; Löscher, C.; Reche, I. Sunlight drives the abiotic formation of nitrous oxide in fresh and marine waters. Science 2025, 387, 1198–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).