1. Introduction

The international second-hand clothing trade is a huge global commercial network that provides the main source of garments for millions of consumers living in poverty. The wholesale trade was valued at over 4.9 billion dollars in 2024, and an estimated 24.2 billion individual items of apparel were exported from developed economies (see explanation in

section 3.2) [

1] (UN Comtrade, 2025). Used apparel is primarily traded from affluent societies in Asia, Europe and North America to sub-Sharan Africa, Central America, Eastern Europe and some of the developing economies of Asia. It has a direct impact on the livelihoods of many of the world’s poorest people and the economies of low-income countries [

2] (Grüneisl, 2025). As a major flow of materials—in excess of 4,848,586 metric tons per year, as reported to UN Comtrade—the global circulation of used clothes shapes the sustainability of the entire fashion industry, which is one of the world’s most expansive and resource intensive consumer sectors [

3] (Fletcher, 2013). Despite this large economic and environmental silhouette, the trade receives limited attention from policy makers, only occasional mentions in the international media, and has been under-explored within academic literature on sustainability [

4] (Brooks, 2019).

In addition to this empirical lacuna, the international second-hand clothing trade demands further critical attention due to new market trends that are disrupting the onward sale of high value garments, and the way in which the used clothing networks fits within conceptions of a ‘circular economy’ [

5] (Brooks et al. 2017). First, the growth in peer-to-peer retail via online platforms, such as Vinted, is using digitalization and connectivity to enable new patterns of used clothing commerce within developed economies [

6] (Failory, 2023), a growth area is characteristic of industry 4.0 [

7] (Da Costa et al., 2019). Secondly, within the fashion sector, as sustainability has become an important value for brands, retailers and consumers, the means by which garments are re-sold, at either national or global scales, has become an important indicator of the potential for the sector to be at the forefront of a nascent circular economy [

8] (MacArthur, 2013). Despite the avowed enthusiasm among key industry players for a circular fashion economy, evidence suggests that there has been limited progress towards this objective. Rather the used clothing trade may be undermining any transition towards a truly sustainable fashion sector [

9] (The OR, 2025). Lower levels of material and energy use would require a more fundamental transformation of market relations and slowing of cycles of production and consumption that would ultimately disrupt the dominate fast fashion retail model [

10] (Fletcher, 2010].

The purpose of the article is to set out the main features of the international second-hand clothing trade and explore if and how the sector contributes to sustainability. The first results section (3.1) provides an overview of the origins and structure of the trading networks, drawing on evidence from historical and contemporary source material. Next the most important export patterns are mapped out to indicate the major sources and sinks of used garments, via analysis of UN Comtrade data (3.2). Thirdly, the economic impact of imports on sink nations are investigated (3.3) highlighting the ways in which low-value used clothes have out-competed domestic clothing industries or crowded-out the opportunities for industrial development. Here evidence focuses on under-development in sub-Sharan Africa and draws on data from key nations. The next section of results (3.4) considers the environmental impacts of the trade both on destination countries, drawing on local reporting, and conceptually at a global scale. The final results section (3.5), sketches out the recent growth in peer-to-peer retail in Europe and North America.

Following the presentation of this research evidence, the used garment networks are discussed in relation to the circular economy, examining both the current contribution and the potential and limits of clothing re-use systems. The conclusion section serves the main aim of the paper in evaluating if the second-hand clothing trade is a sustainable industry, with reference to not just the environmental impacts, but also the cultural and economic sustainability of the international second-hand clothing trade for the world’s poorest people.

2. Materials and Methods

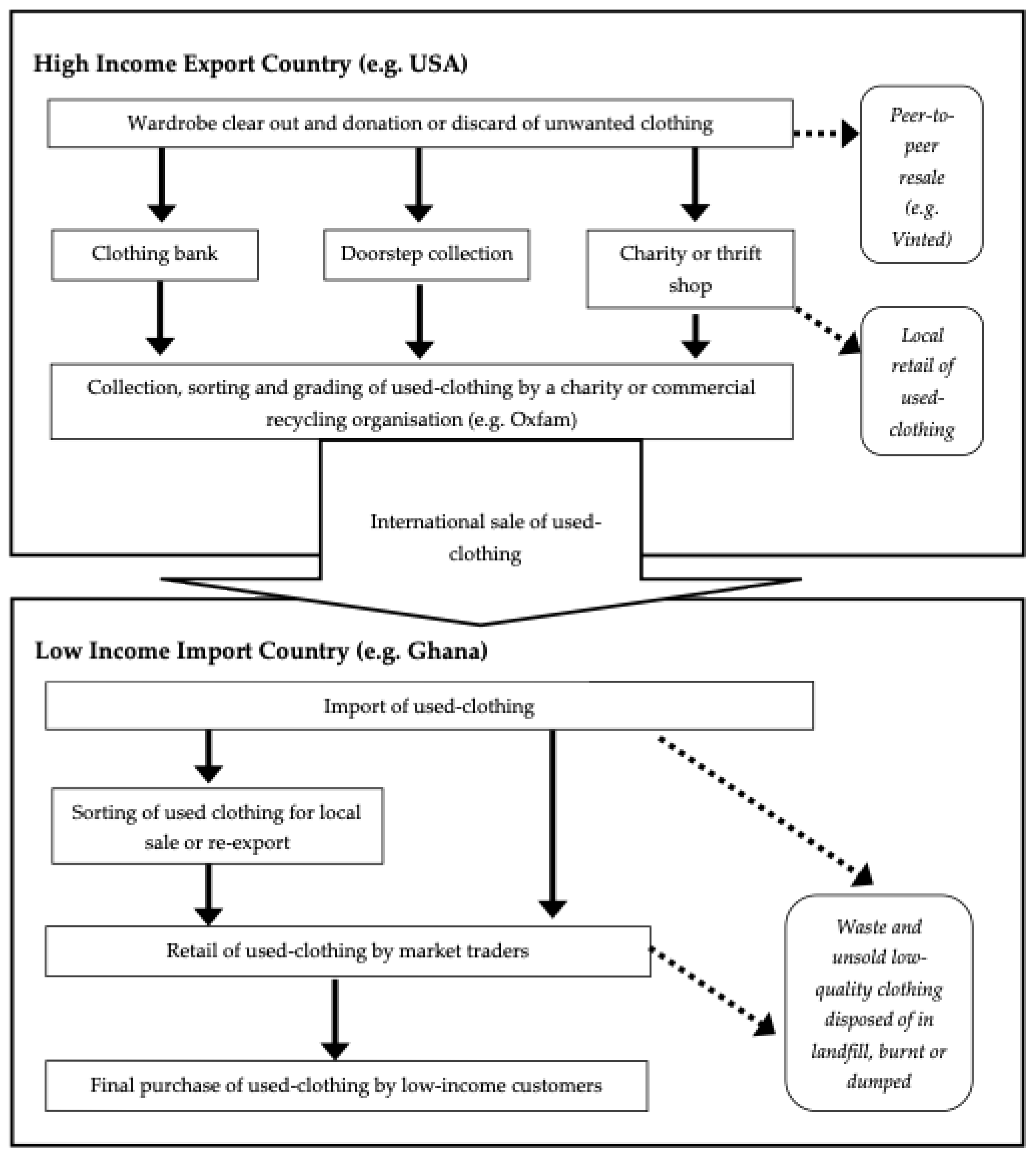

This study is based upon different modes of research, with layers of evidence serving different sections of the results. The background overview (3.1) draws upon previous research by the author in mapping second-hand clothing networks carried out in multiple field studies since 2010 and previously published elsewhere see [

4,

11,

12] (Brooks, 2019; Ericsson and Brooks, 2014; Brooks 2013). To provide an accessible overview a conceptual flow chart was produced (

Figure 1). The primary quantitative evidence in 3.2 draws upon analysis of UN Comtrade data and follows the approach of Frazer (2008) [

13]. The most recent available UN data was cleaned, tabulated and presented. All the UN Comtrade statistics quoted are SITC code 26901 ‘Bulk textile waste, old clothing traded in bulk or in bales’ and all commodity values are converted from national currency into US dollars using exchange rates supplied by the reporter countries, or derived from monthly market rates and volume of trade. Export figures are used in place of import figures, due to the greater reliability of export reporting in the used clothing trade, see Brooks and Simon (2012) [

14] for further discussion. To investigate the wider economic impacts of the second-hand clothing trade at a macro level (3.3), existing trade reports, NGO reports, academic studies and other grey literature were systematically reviewed. The environmental assessment similarly drew upon a range of published sources. Section 3.5 primarily drew upon corporate and media reporting of the rise of peer-to-peer retail, given the limited amount of publicly available economic data on this developing trade pattern.

3. Results

3.1. An Overview of the Intenrational Second-Hand Clothing Trade

The starting point of the international second-hand clothing trade is the overconsumption of cheap fast-fashon in Europe and North America [

15] (Cline, 2013). The persistent marketing of new product lines and the constant cycles of buying, wearing and discarding clothing means there is an abundunt supply of billions of re-useable garments that have limited economic value in their local markets. For the majority of people, who can readily afford to buy new items, unwanted clothes that are outgrown, worn out, unfashionable or no longer needed are either discarded as part of the household waste for commercial disposal, depositied for recycling or donated for resale by charities. Alongside the limted number of clothes resold via peer-to-peer networks (e.g. Depop, eBay, Vinted, discussed in 3.4), the local sale of used clothing in chairty stores (as predominate in the UK) or thrift stores (comonplace in the USA) represents a sustainable re-use of clothing. However, due to the limited demad for second-hand clothing in developed economies the majority of collected used garments are processed for export, via large and well established networks, iincluding many of the donations made to charities such as Oxfam [

16] (Gregson and Beale, 2004).

Used clothes are typically sourced via doorstep collections, depostis in clothing banks or in-store donations. From there, the majority will never reach the over-saturated domestic second-hand market and instead will be processed for export (see

Figure 1). Processing plants work to transform disorderly and random deposits of garments in to valuble export commodities. Clothes pass along convey belts where pickers sort out different categories—such as women’s blue jeans or men’s coloured t-shirts—and discard soiled items, unwearbale rags and rubbish. The industry standard is for sorted clothes to be wrapped in 100 lbs/45 kg bales, and packed into shipping containers. Sometimes, unsorted clothing is shipped directly to a low-income country where the garments are sorted before being re-exported. However, as transport costs are high, relative to the vlaue of the commodity, and the highest grade clothing is disproprionately profitable, sorting prior to export is more common. Intricate and perplexing supply networks have long been a feature of the global trade [

17,

18] (Haggblade, 1990; Velia et al., 2006), but what is clear is that this is overwhelmingly a commercial trade pattern, and the used-clothes collected by charities and clothing recyclers alike are exported to the Global South and sold for profit [

19] (Baden and Barber, 2005). Across used clothing networks there is limited knowledge among those who rid themsleves of unwanted garments of their ultimate destinations and the final consumers in countries such as Kenya, Mozambique, and Zambia are equally unfamiliar with their previous lifecycles [

20] (Hansen, 2000). The worlds richest and poorest people are intimately linked when the latter pulls a t-shirt over the head that months earlier someone a world away took off and threw away.

Figure 1.

Simplified schematic representation of the international used-clothing trade, after Brooks (2013).

Figure 1.

Simplified schematic representation of the international used-clothing trade, after Brooks (2013).

3.2. Import and Export Patterns

The second-hand clothing sector is global in reach, but is not universal. It has particular geographies shaped by econmic, political and social forces. The low-value of used-clothing means that it may be used as mark-up cargo to fill vessels to capacity, or act as the return freight on shipping routes, so it can be shaped by other economic relationships. Diaspora networks can link export and import countires, these are especially beneifcal as there is frequently a lack of trust between commerical patterns in second-hand clothing businesses due to the inherent variability of the goods [

21] (Abimbola, 2012). Cultural values can also be important as clothing products from some export countries are of greater value as they suit particular down-stream markets.

UN Comtrade data shows 4,848,586,806kg of clothing was exported in 2024. This includes a mix of light (e.g. underwear), medium (e.g. shirts) and heavy weight items (e.g. coats). Less bulky, light weight items are most commonly traded internationally, and light apparel is preferred in the primarily warm and tropical climates of export destinations. Therefore taking the average item to be a 0.2kg t-shirt, the total weight of the global exports is equal to 24.2 billion items.

3.2.1. Exports

As shown in

Table 1. the top 20 export countries account for 90% of the global trade in used clothing by value (

$4.5 billion). As the two largest economies in the world, it is as expected that the USA and China fill the top two positions, but they are there for different reasons. The USA is the world’s biggest fast-fashion market and has long been the most significant source of used clothing, with its primary destination being central America. However, American used clothing is not consistently prized in export markets, this includes social challenges around body shape. For instance, in West Africa clothing shipments from the USA are typically of lower value than items from the UK because the average waist size in the USA is greater and clothes are less likely to fit slimmer African bodies [

12] (Brooks, 2013). After the UK, which is a clear third by value and has strong cultural ties with many destination countries and a long history of domestic clothing recycling, the majority of the exporters are the advanced EU economies, as well as South Korea and Australia.

Chinese exports of used clothing have risen dramatically over the last 10 years, from 133 million kg in 2015, to 1.147 billon kg in 2024. Chinese exports are now greater than the combined weight of UK and USA exports but are only worth half the amount in dollars. As the UN data includes bulk textile waste, and China is the world’s largest manufacturer of clothing, which is primarily fast-fashion for high-income countries, much of the Chinese exports are of waste rather than pre-worn clothes. This can include faulty clothing goods and shoddy (torn textiles) and will combine both clothing exported to be worn for the first time and apparel waste to be used in industrial processes, as well as used clothes.

Pakistan, Malaysia and India all feature as major exporters. For the two South Asian nations there is clear evidence of their roles as re-exporters. Indeed, in India used-clothing imports for the domestic market have been banned. Clothing sorting plants operate in special economic zones where they export sorted and graded used clothing to secondary markets, primarily in East Africa [

22] (Norris, 2010). As the value of imports exceeds Malaysian exports it suggests that Malaysia (see

Table 2) follows a similar pattern to Pakistan

3.2.2. Imports

Used clothing is primarily exported to a wide range of low income-countries from a narrower set of rich nations. To determine the twenty major importers of used clothing, the destination of exports from the twenty largest exporters was used (

Table 2). The most significant destination is Pakistan, which has both an important domestic market for used clothes, especially from the UK where diaspora networks link supply and demand, but also as a processing hub for re-export. The presence of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) at second among the top destination for exports, despite it being a relatively advanced economy with a small population. It’s absence from the list of exporters (

Table 1), suggests that either used clothing is very popular in the UAE –a hypothesis we can reject given the limited retail market for second-hand clothes– or it is acting as a shipping hub, and the second-hand clothes are re-exported. This demonstrates a limit of the UN Comtrade data (which is the best available data set) in recording the ultimate destination for used clothing exports.

The remainder of the top twenty listed is mainly populated by low-income countries in Central and South America, Africa and Asia. It is in these marketplaces where large volumes of used clothing imports provide the major sources of clothing for local people [

23] (Maclean, 2014). Ukraine is the eighth biggest destination, but by weight imports far fewer garments than nations with comparable dollar values of imports such as Ghana, the Philippines and Poland. This is most likely accounted for by the re-sale of used military clothing and other high-value items in support of the armed forces. Poland has historically been a major recipient of out of season styles from western Europe.

A notable outlier at number 20 is Japan, one of the world’s most affluent consumer societies, this is for a very particular reason. Japan imports a small volume of high-value collectable vintage clothing primarily from the USA. In Japan, items such as distressed denim jeans, leather jackets and iconic fashion labels are highly prized, with interest in Americana stemming from the post-War era when many US troops were stationed in Japan and influenced the fashion culture [

24] (Yoshimi and Buist, 2003). This type of high-value niche re-use of fashion is very different to the overwhelming pattern of the international second-hand clothing trade, but serves as an example of the ways in which economic value can be restored in used clothing articles, and showcases that there is the potential to foster regimes of re-use that value previously discarded garments [

25] (Fletcher, 2016).

3.3. Economic Impacts

Imported used clothing provides a cheaper source of garments than equivalent new apparel and is thus preferred by low-income consumers in the impoverished nations which import the bulk of global exports. In countries where there is sorting and grading facilities, often in export processing zones, this work provides opportunities for value adding and revenue generation. However, large imports of used clothing to economies with persistent real trade deficits, such as Ghana and Kenya, harms their economic situation [

26] (Stop Waste Colonialism, 2025). Moreover, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, the trade has faced persistent attempts to ban and control imports, due to its negative economic and cultural impacts. This includes the case of Rwanda, where imports face a punitive tariff of

$2.50 per kilogram [

27] (Africanews, 2024). “The objective is to see many more companies produce clothes here in Rwanda,” said Telesphore Mugwiza, an official at Rwanda’s ministry of trade and industry speaking when the ban was first implemented [

28] (quoted by Gambino 2017). Rwanda has faced recent pressure from the United States to relax trade controls, but other more powerful countries have persistently regulated the trade. India has long successfully maintained an outright ban on used clothing imports and protected their domestic industry. With regard to culture, Mugwiza continues to explain how there is an issue of human dignity and independence for Rwandans: “It is also about protecting our people in terms of hygiene. If Rwanda produces its own clothes, our people won’t have to wear T-shirts or jeans used by someone else. People need to shift to [this] kind of mindset.” Sales of used underwear are common in Africa (see

Figure 2). It is impossible to celebrate the sustainability of the international second-hand clothing trade when it is part of a global economic structure that leaves some consumers so impoverished that the only underwear they can afford are previously worn items discarded by affluent consumers in rich countries. This is not the sustainable provision of clothing this an afront to human dignity.

Counter perspectives are that it was economic liberalization in the 1990s that killed the African clothing industries and eliminating used clothing imports will not address the underlying economic problem [

13] (Frazer, 2008). Additionally, some advocates for the trade highlight the entrepreneurial opportunities enabled by second-hand clothing imports, which can be tailored, adding value and recreating new commodities [

29] (Textile Recycling Association, 2020). However, these are niche enterprises, the vast majority of pre-worn garments are simply re-sold in the same condition as they were discarded in the Global North.

Today the African continent lacks an industrial base. Previously, there were periods of economic modernization in the 1970s and 80s that built fashion industries, which used African grown cotton to manufacture garments for local and international markets, this helped boost local economies and met indigenous culture desires for appropriate clothing. Since then the closure of clothing factories in countries including Mozambique, Nigeria and Zambia has been directly attributed to the import of used clothing [

14] (Brooks and Simon, 2012) and in countries like Rwanda, with limited manufacturing capacity, the imports crowds-out the opportunity for local producers to establish themselves in domestic markets – however the same is true of cheap new clothing imports. It is also common for used clothing to be illegally imported into African countries like Zimbabwe where import duties are circumvented and cheap used clothes have had widespread negative impacts on local businesses [

30] (Mafundikwa, 2024).

Trade controls on second-hand clothing could contribute to sustainable industrial development as part of a wider economic policy. Continued uncontrolled imports of used clothes from the West present a barrier to modernization. Furthermore, it is concerning that organizations such as Oxfam, Humana and the Salvation Army that champion sustainability and charitable values, are among the major beneficiaries of the international second-hand clothing trade. Despite their knowledge of the harms caused by the trade: ‘Oxfam GB recognises the potential negative impact that the export of donated textiles can have on the countries where they are sent to, which include impacts on human rights, local economies and the environment.’ [

31] (Oxfam, 2021) But they argue Oxfam must ‘extract the most value out of the donations we have been entrusted with’. Any broad positive impacts these NGOs have in pursuing an agenda of advocacy and direct action in their wider policy work on sustainability and poverty reduction, must be measured against their immediate roles in the used clothing trade and the broader effect they play as figureheads for the used clothing trade. NGOs promote the legitimacy of the entire international second-hand clothing sector that holds the poor in a relationship of dependency and furnishes them with garments like use underwear, which undermines their dignity. The trade is both a symptom and a cause of Africa’s persistent impoverishment.

3.4. Environmental Impacts

The international second-hand clothing trade is frequently cited as a socially and environmentally sustainable sector because it is all about commodity reuse. Oxfam for instance argues that: ‘Donating and buying clothes with Oxfam is a powerful choice to support people around the world to tackle the inequality that fuels poverty.’ [

33] (Oxfam, 2024). As discussed this positioning of the trade as anti-poverty initiative is deeply problematic, especially as Oxfam is a major exporter of used clothing, which it does ‘In order to extract the most value out of the donations we have been entrusted with, we sell thousands of tonnes a year of textiles to third-party customers, and often that is with a view to those textiles being exported’. [

32] (Oxfam, 2021). Oxfam subsequently highlighted what they frame as the environmental benefits: ‘When you’re buying second hand clothes, you’re promoting circular fashion by ensuring that existing clothing is worn until the end of its lifespan’ [

33] (Oxfam, 2024) and while it is the case that it is sustainable to reuse wearable clothing goods rather than recycle the materials, suggesting that by donating used clothing you are also contributing to a circular fashion system elides the truth. Most collected used clothing is exported and the trade is an efficient system of transferring garments from places where there is limited market demand to new places where there is a ready market for cheap apparel, but this is just pushing the problems of fast fashion downstream from rich to poor countries, and many collected clothes will never be re-worn but end-up as unrecycled waste. The root cause of the problem is the rampant overconsumption of new fashion. If you want to contribute to sustainability it is simple: don’t buy new fast fashion, and re-wear your useable clothes rather than getting rid of them. When viewed from a systems perspective, rather than addressing the fundamental unsustainability of the fast-fashion sector the used clothing sector serves to provide a seemingly virtuous outlet for old garments (‘tackle the inequality that fuels poverty’ as Oxfam [

33] (2024)) and the act of clearing out the wardrobe paves the way for more, and more, unsustainable new clothing consumption.

In addition to the role the second-hand clothing trade plays within the wider material culture of the fast-fashion sector, the imports have negative environmental impacts in the low-income countries that are acting as a sink for the textile waste of rich societies. The effect of the billions of unsold used clothing items that are shipped to poor countries is difficult to quantify; it is one of the many hidden aspects of the trade. Opponents of the trade have gone as far as to call the trade a form of ‘waste colonialism’ a term used to demonstrate how power relationship are articulated through the dumping of rubbish, pollutants and hazardous materials in impoverished countries [

26] (Stop Waste Colonialism). For instance, it is estimated that nearly half of the 15 million items of clothing imported to Ghana every week are unsellable. Many go to informal dumpsites or are burned in public warehouses, leading to air, soil and water contamination [

9] (The OR, 2025). Greenpeace [

33] (Omondi, 2024) reports dangerously high levels of toxic substances in indoor air at processing facilities, microplastics pollution and the accumulation of textile waste smothering ecosystems, polluting rivers, and creating ‘plastic beaches’ covered in apparel waste along the coast of Ghana. Like many sub-Saharan African countries, in Ghana there is little or no infrastructure for recycling unsold garments and these textiles ultimately become rubbish that is dumped, buried or burnt.

3.4. Peer-to-Peer Retail

The international-second hand clothing trade is all about creating new value from old clothes, and while the sector is as old as the clothing industry itself [

34] (Strasser, 1999) it continues to evolve and find new means to enhance profitability. The new-technology characteristic of industry 4.0 are utilizing digitalization to this effect, this diffuse development is sparking change. A new evolution in the second-hand clothing trade draws on the abundance of decentralized information technologies, namely the way that any smartphone can be used as a shop front for the re-sale of secondhand clothes. Retail platforms that use peer-to-peer technologies including Depop, eBay, and especially Vinted have led a boom in pre-loved and vintage fashion. This Lithuanian company, that started in 2008, has grown to become Europe’s largest online clothing marketplace with over 100 million users across 22 countries. As a smartphone-first platform it makes selling old clothes directly to other peer consumers as frictionless as possible, with no seller fees and integrating the postal process.

What is different about peer-to-peer trade networks is that due to the proportionately high postage costs associated with individual clothing purchases they are centered on domestic markets. What drives profitability is the way in which Vinted specializes in helping vendors to maximize the price of their old garments and uses algorithms to pitch items to browsing online shoppers. Fashionable goods with designer labels are prized and the existence of a frictionless medium for reselling designer fashions, may deprive the charity stores and thrift shops of these commodities. The platform even enables authentication services to build trust between peers. This model of reuse is more sustainable than exporting large volumes of used clothing, especially if it deters the consumer from buying more, new fast fashion. However, this requires further investigating as, rather than being a simple solution, at a wider scale Vinted could be promoting a culture of overconsumption if it is feeding the growth of the overall clothing market in a new way. By encouraging consumers to clear-out their wardrobe, and make some extra income, it could be catalyzing another cycle of new retail fast fashion consumption, rather than facilitating a circular economy. At a global systems-level rather than being a sustainable solution, peer-to-peer selling may be enabling ever-greater, faster-faster consumption of new fashion.

4. Discussion

The international second-hand clothing trade maps the contours of inequality in the world economy. Exports shipped to the top 20 import countries represents 55% of the total value of all global used clothing exports, whereas the top 20 exporters send out 90% of the total value of used clothing exports. In simple terms this means that there is greater variety in the used clothing import destinations than the export origins. This is in keeping with an unequal world: there is a concentration of wealth in the richest economies and far greater levels of consumption, whereas most of the world in lower-income economies have fewer opportunities to consume. In marketplaces flooded with used-clothing imports there is little space for affordable alternatives to wearing discarded garments. As well as being a marker of income inequality the shipment of waste clothing to impoverished countries is a system of exporting rubbish from societies with unsustainable patterns of fast fashion consumption. This waste colonialism has negative impacts on the environments and livelihoods of the world’s poorest people and inhibits their prospects of developing their economies.

Advocates for the international second-hand clothing trade such as [

35] The Textile Think Tank (2025) argue that the sector is ‘a pillar of circularity’ citing three ways in which the trade contributes to sustainability: (i) it reduces textile waste by diverting clothing form landfill, (ii) lowers the carbon and water footprint of clothing consumption as reusing garments requires 70% less emission, and (iii) that it boosts secondhand markets in Africa, Asia and Latin America creating jobs and affordable fashions. As the results demonstrate that each of these three conceptions is flawed.

First, in terms of reducing waste what is really required is to slow cycles of consumption in the global North rather than pushing the problem of clothing rubbish downstream. When old clothes ‘go away’ to charities or textile recyclers people are not confronted by their unsustainable consumption patterns. Conversely by providing a virtuous outlet for consumers to have a wardrobe clear-out both the international used clothing trade and, potentially, peer-to-peer selling, are providing more space for consumption, although more research is required to map the broader life cycle impacts and sustainability of peer-to-peer resale at a global systems level.

Secondly, in terms of water-footprint and emissions, both of these issues would be better addressed by lower consumption of sustainably produced garments – that is treating the root cause rather than trying to ameliorate the consequences of overconsumption. Furthermore, from a social justice perspective, if the world market routed new clothing manufacturing directly to marketplaces in the global South, rather than excess clothing transiting through the wardrobes of the world’s most affluent consumers, than the poor would have access to newer garments and less energy would have been expended in their transport.

This leads on to the third and final issue, while retailing used garments does provide a livelihood for people in low-income countries such as Mozambique, one of the major global importers, my own field research has demonstrated that these livelihoods still leave the traders in poverty [

11] (Ericsson and Brooks, 2014). Moreover, the work is less profitable than the equivalent trading work selling imported new clothing. Beyond retail employment, the impact of clothing imports on deepening trade deficits in low-income countries is a chronic issue. Low-income countries would be boosted by building – or resurrecting - infant industries like clothing manufacturing. That would contribute to their industrialization and further their independent development in place of deepening the relationships of structural dependency.

5. Conclusions

There is a simple oft-repeated maxim in sustainability: ‘reduce-reuse-recycle’. It is better to reuse old clothes than recycle them, less energy and material inputs are required to deliver wearable clothes and making effective use of the current global stock of garments encapsulates the type of approach we should be taking towards consumption. A vibrant trade in used clothing could contribute to making the fashion sector more sustainable, but this is only as something which erodes the fast-fashion industry rather than as a secondary economic system that feeds off the excesses of overconsumption in rich consumer societies. The second-hand clothing trade is pitched as a sustainable solution. However, ultimately it is the reduction of consumption of new clothing in the first place which is the only way to transition to sustainability in the fashion sector. It is easy for advocates of the trade to make the simple, intuitive, surface argument that the international second-hand clothing trade, as well as peer-to-peer retail, are sustainable circular systems that should be celebrated, but as the results presented here illustrate the international trade has detrimental downstream economic, cultural and environmental effects in low-income countries, and arguably both the export of clothing and peer-to-peer sales facilitate wardrobe clear-outs, and fuel more and more fast fashion consumption in rich societies. Potential donors of used clothes to Oxfam and other clothing recyclers should remember that the most sustainable clothes they can wear are those in their own wardrobe. Old clothes don’t go away, they go somewhere to people with less power and choice and the trade can contribute to locking them into relationships of dependency, cultural deprivation, And cause environmental harm.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank all the support, including from field assistants in Malawi, Mozambique and Zambia, that undergirded previous original studies that provided the background for this article.

References

- UN Comtrade. Available online: https://comtradeplus.un.org/TradeFlow?Frequency=A&Flows=X&CommodityCodes=TOTAL&Partners=0&Reporters=all&period=2024&AggregateBy=none&BreakdownMode=plus (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Grüneisl, K. Limits of circularity: Examining ruptures to valuation work in Tunisia's used clothing economy. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K. Sustainable fashion and textiles: Design journeys; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, A. Clothing poverty: The hidden world of fast fashion and second-hand clothes; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, A.; Fletcher, K.; Francis, R.A.; Rigby, E.D.; Roberts, T. ; Fashion, sustainability, and the Anthropocene. Utopian Studies. 2017, 28, 482–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Failory. Vinted's Business Model & How They Make Money in 2024. Available online: https://www.failory.com/blog/vinted-business-model (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Da Costa, M.B.; Dos Santos, L.M.A.L.; Schaefer, J.L.; Baierle, I.C.; Nara, E.O.B. Industry 4.0 technologies basic network identification. Scientometrics 2019, 121, 977–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, E. (Towards the circular economy. Journal of industrial ecology 2017, 2, 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- The, OR. Too Much Clothing, Not enough Justice. Available online: https://theor.org/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Fletcher, K. Slow fashion: An invitation for systems change. Fashion practice. 2010, 2, 259–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, A.; Brooks, A. African second-hand clothes: Mima-te and the development of sustainable fashion. In Routledge handbook of sustainability and fashion; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, A. Stretching global production networks: The international second-hand clothing trade. Geoforum. 2013, 44, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, G. Used-clothing donations and apparel production in Africa. The Economic Journal. 2008, 118, 1764–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, A.; Simon, D. Unravelling the relationships between used-clothing imports and the decline of African clothing industries. Development and Change. 2012, 43, 1265–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cline, E.L. Overdressed: The shockingly high cost of cheap fashion; Penguin: New York, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gregson, N.; Beale, V. Wardrobe matter: the sorting, displacement and circulation of women's clothing. Geoforum. 2004, 35, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggblade, S. The flip side of fashion: Used clothing exports to the third world. The Journal of Development Studies. 1990, 26, 505–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velia, M.; Valodia, I.; Amisi, B. Trade dynamics in used clothing: The case of Durban, South Africa. School of Development Studies, University of Kwazulu/Natal; 2006 Sep 18.

- Baden, S.; Barber, C. 2005. The impact of the second-hand clothing trade on developing countries. Oxfam. Available online at: oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com.

- Hansen, K.T. Salaula: The world of secondhand clothing and Zambia. University of Chicago Press: USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Abimbola, O. The international trade in secondhand clothing: managing information asymmetry between West African and British traders. Textile. 2012, 10, 184–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, L. Recycling Indian clothing: Global contexts of reuse and value; Indiana University Press: 2010.

- Maclean, K. Evo's jumper: identity and the used clothes trade in ‘post-neoliberal’ and ‘pluri-cultural’ Bolivia. Gender, place & culture. 2014, 21, 963–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimi, S.; Buist, D. America as Desire and violence: Americanization in Postwar Japan and Asia during the Cold War. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 2003, 4, 433–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K. Craft of use: Post-growth fashion; Routledge: Abingon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stop Waste Colonialism. Available online: https://stopwastecolonialism.org/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Africanews. Available online: https://www.africanews.com/2018/05/24/rwanda-sticks-to-its-guns-on-used-clothes-ban-despite-us-threats-to-withdraw/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Gamibino, L. 'It's about our dignity': vintage clothing ban in Rwanda sparks US trade dispute. The Guardian, 29 December 2017.

- Textile Recycling Association. Kenyan Government Releases Protocol. Available online: https://www.textilerecyclingassociation.org/press/kenyan-government-releases-protocol/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Mafundikwa, I. How secondhand clothes took Zimbabwe by storm – and hammered retai. Al Jazeera. 30 Sep 2024. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2024/9/30/how-secondhand-clothes-took-zimbabwe-by-storm-and-hammered-retail (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Oxfam. Oxfam GB Textiles Export Policy. Available online: https://www.oxfam.org.uk/documents/690/Textile-Exports-Policy-August_2021.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Oxfam. Buying Second hand clothes: What are the Benefits? Available online: https://www.oxfam.org.uk/oxfam-in-action/oxfam-blog/the-benefits-of-buying-second-hand/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Omondi, F. ast fashion, slow poison: new report exposes toxic impact of global textile waste in Ghana. Green Peace. 11 September 2024. Available online: https://www.greenpeace.org/africa/en/press/56381/fast-fashion-slow-poison-new-report-exposes-toxic-impact-of-global-textile-waste-in-ghana/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Susan Strasser. Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash; Metropolitan Books: New York, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- The Textile Think Tank. Global Worn Clothing Export: A Pillar of Circularity 5 February 2025. Available online: https://thetextilethinktank.org/global-worn-clothing-export-a-pillar-of-circularity/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).