Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

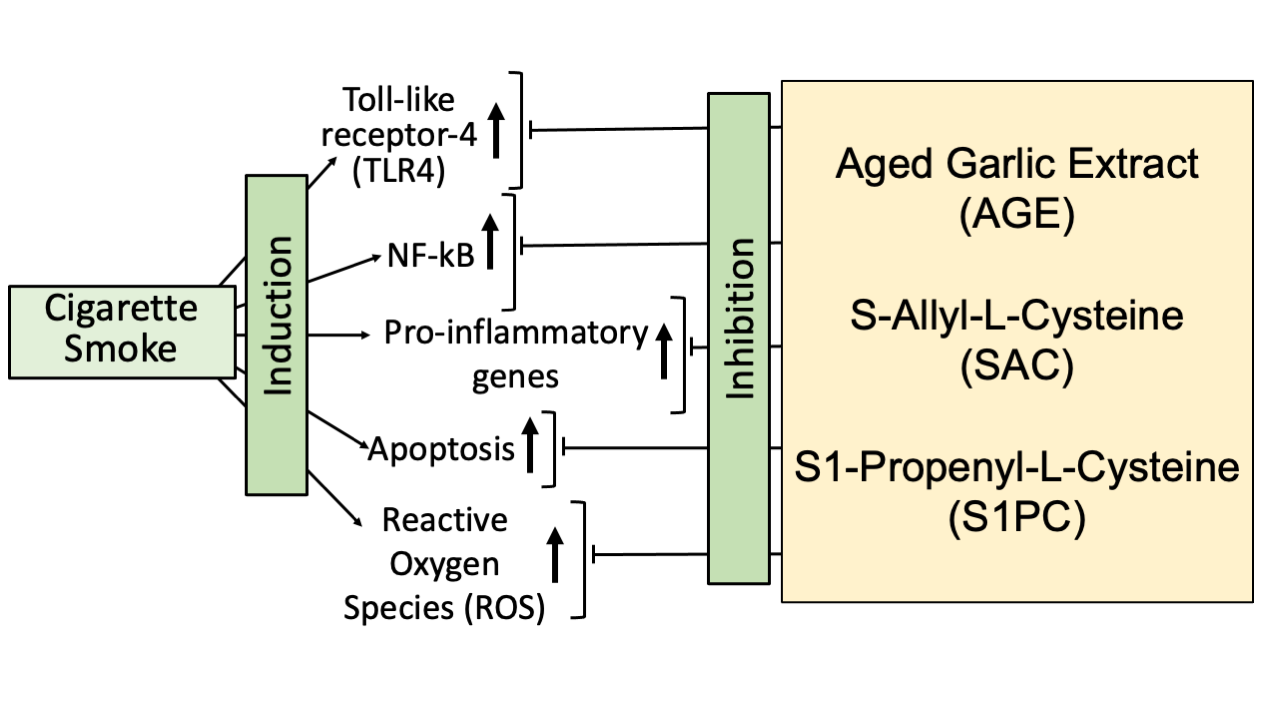

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

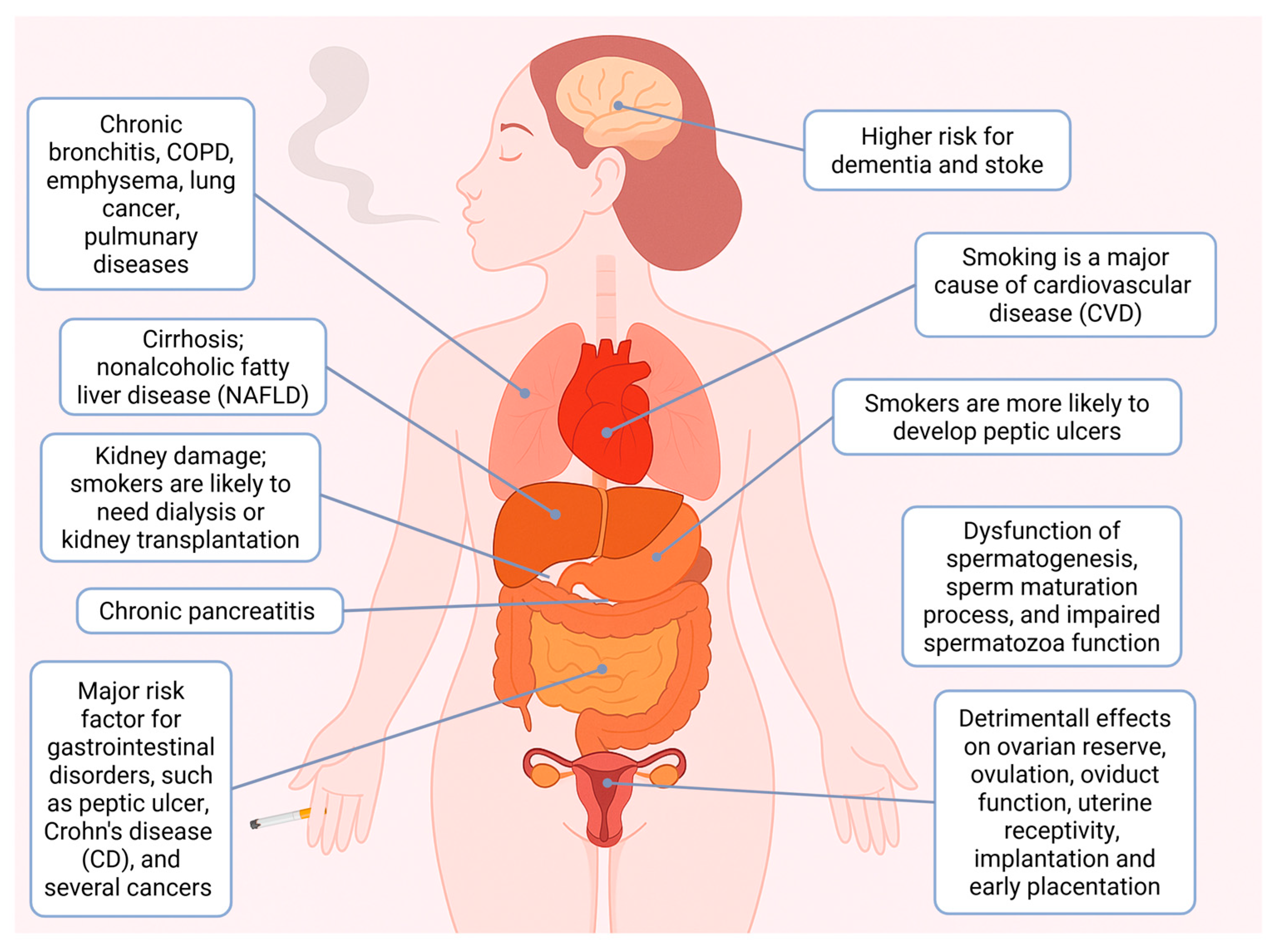

2. Impact of Cigarette Smoke on Human Health

2.1. Smoking and Human Diseases

2.2. Smoking and Cancer

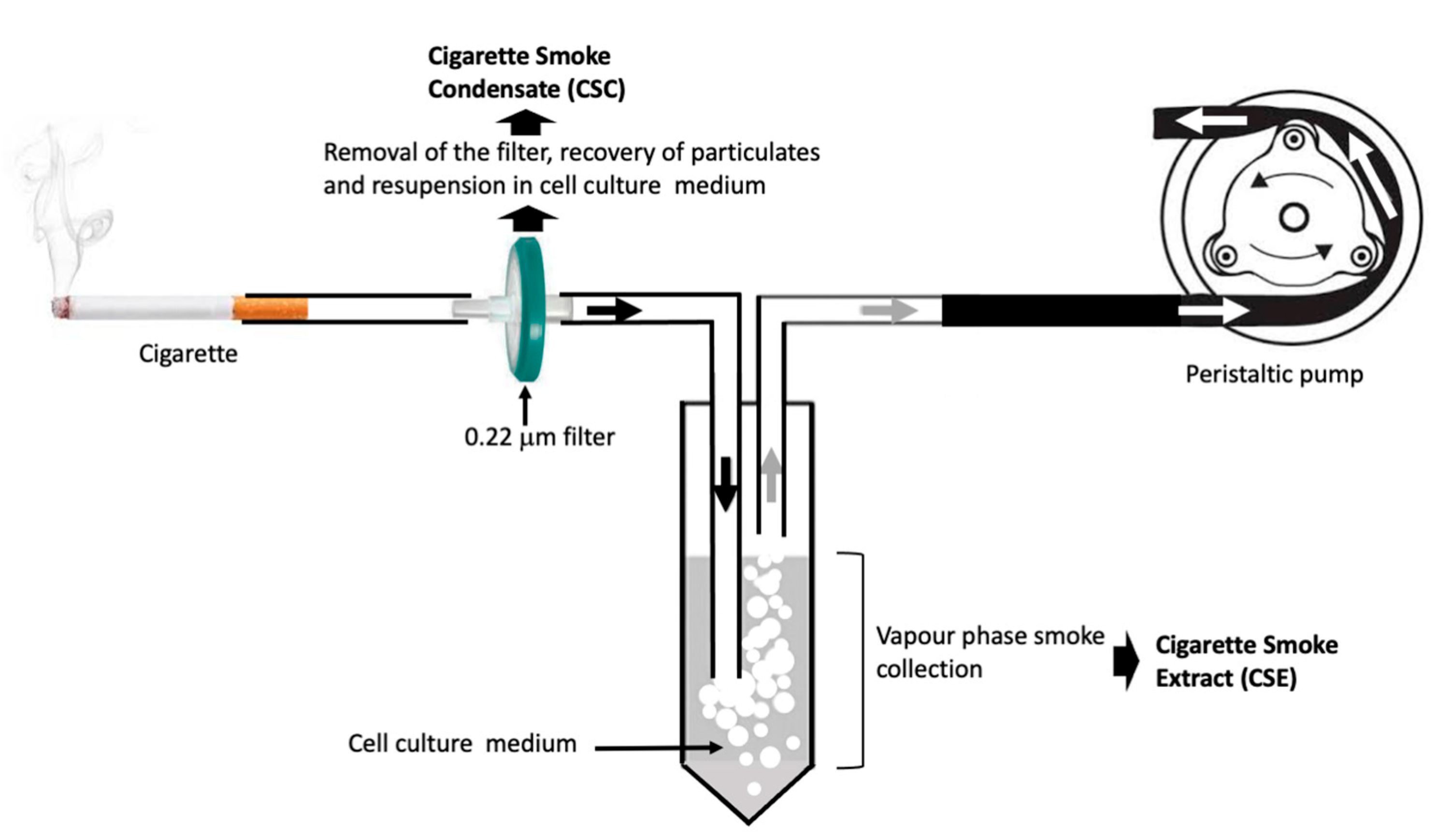

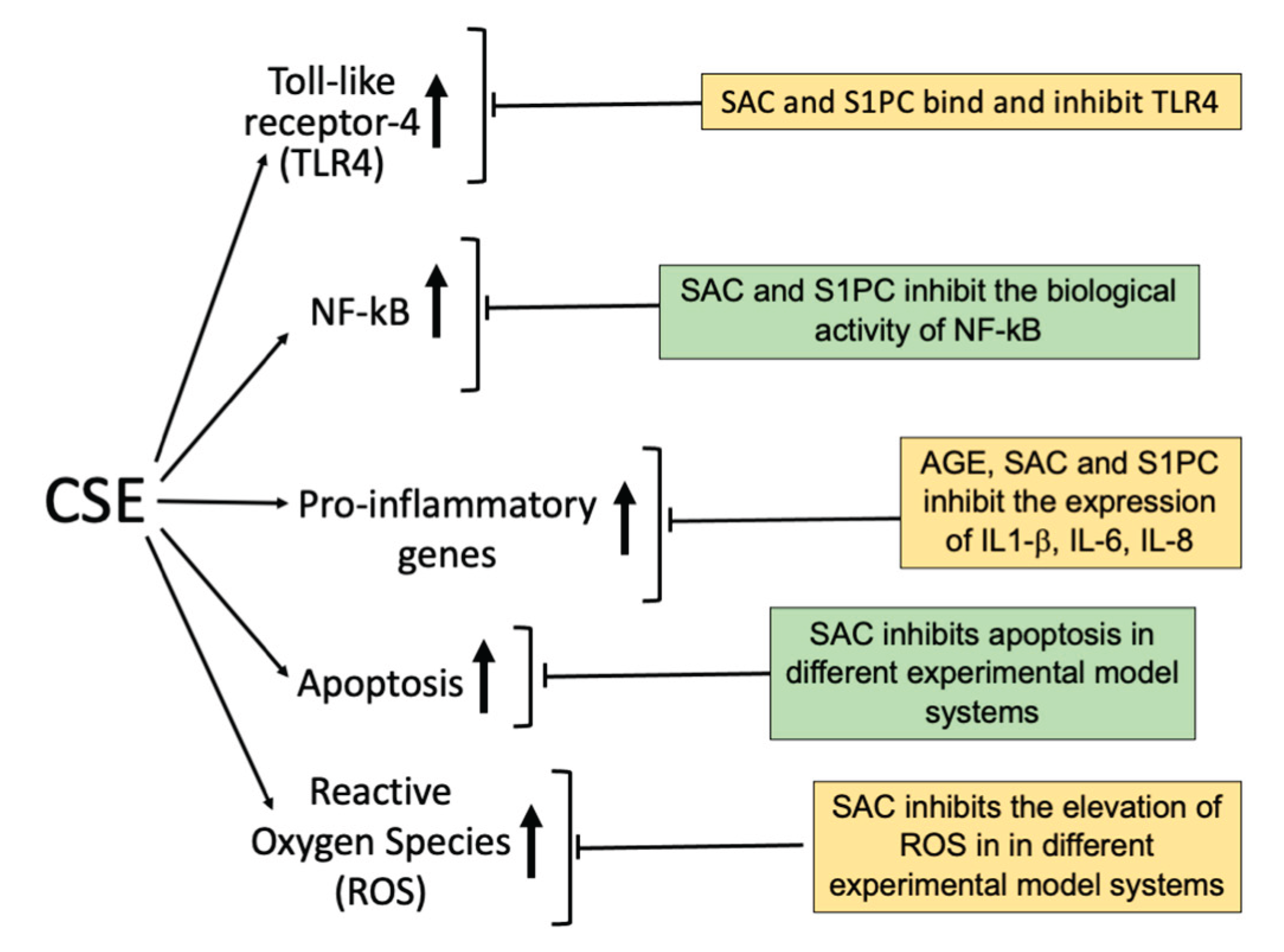

3. Mechanism(s) of Action of Cigarette Smoking: Inflammation

3.1. Cigarette Smoking and Nuclear Factor-kB (NF-kB)

3.2. Cigarette Smoke and Toll-like Receptor-4 (TLR4)

3.3. Cigarette Smoke and Increased Release of Pro-Inflammatory Proteins

3.4. Cigarette Smoke and Apoptosis

3.5. Cigarette Smoke Induced Formation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

4. Natural Products for the Mitigation of Toxic Biological Effects of Cigarette Smoke

4.1. Silymarin

4.2. Eucalyptol

4.3. Curcumin

4.4. Taraxasterol

4.5. Sulforaphane

4.6. Corilagin

4.7. Trans-4,4'-dihydroxystilbene

4.8. Other Example of Natural Products Against CS Effects

5. Aged Garlic Extract and Its Bioactive Components: Candidates for Mitigating the Cigarette Smoking Effects

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CS | Cigarette Smoke |

| CSC | Cigarette Smoke Condensate |

| CSE | Cigarette Smoke Extract |

| VOC | Volatile Organic Compounds |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor-kappa-B |

| TLR4 | Toll-like Recptor-4 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| IL | Interleukin |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| AGE | Aged Garlic Extract |

| SAC | S-allyl-l-cysteine |

| S1PC | S1-propenyl-l-cysteine |

| SFN | DHS |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| CF | Cystic Fibrosis |

| BAL | Bronchoalveolar lavage |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco use 2000–2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Dai X, Gakidou E, Lopez AD. Evolution of the global smoking epidemic over the past half century: strengthening the evidence base for policy action. Tob Control 2022;31(2):129-137. [CrossRef]

- Varghese J, Muntode Gharde P. A Comprehensive Review on the Impacts of Smoking on the Health of an Individual. Cureus 2023; 15(10):e46532. [CrossRef]

- Vassallo, R. Diffuse lung diseases in cigarette smokers. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2012; 33:533–542. [CrossRef]

- Kondo T, Nakano Y, Adachi S, Murohara T. Effects of tobacco smoking on cardiovascular disease. Circ J. 2019; 83:1980-1985. [CrossRef]

- Durazzo TC, Mattsson N, Weiner MW. Smoking and increased Alzheimer's disease risk: a review of potential mechanisms. Alzheimers Dement. 2014; 10:122-145.

- Sloan A, Hussain I, Maqsood M, Eremin O, El-Sheemy M. The effects of smoking on fracture healing. Surgeon 2010; 8:111–116.

- Liu Y, Lu L, Yang H, Wu X, Luo X, Shen J, Xiao Z, Zhao Y, Du F, Chen Y, Deng S, Cho CH, Li Q, Li X, Li W, Wang F, Sun Y, Gu L, Chen M, Li M. Dysregulation of immunity by cigarette smoking promotes inflammation and cancer: A review. Environ Pollut. 2023; 339:122730.

- Walser T, Cui X, Yanagawa J, Lee JM, Heinrich E, Lee G, Sharma S, Dubinett SM. Smoking and lung cancer: the role of inflammation. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008; 5(8):811-5.

- Xu X, Shrestha SS, Trivers KF, Neff L, Armour BS, King BA. U.S. healthcare spending attributable to cigarette smoking in 2014. Prev Med. 2021; 150:106529.

- Gu D, Sung HY, Calfee CS, Wang Y, Yao T, Max W. Smoking-Attributable Health Care Expenditures for US Adults With Chronic Lower Respiratory Disease. JAMA Netw Open 2024; 7(5):e2413869.

- Bancej C, O'Loughlin J, Platt RW, Paradis G, Gervais A. Smoking cessation attempts among adolescent smokers: a systematic review of prevalence studies. Tob Control 2007; 16: e8.

- Torchalla I, Okoli CT, Bottorff JL, Qu A, Poole N, Greaves L. Smoking cessation programs targeted to women: a systematic review. Women Health 2012; 52: 32-54.

- Aveyard P, Begh R, Parsons A. Brief opportunistic smoking cessation interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare advice to quit and offer of assistance. Addiction 2012; 107: 1066-1073.

- Komiyama M, Takahashi Y, Tateno H, Mori M, Nagayoshi N, Yonehara H, Nakasa N, Haruki Y, Hasegawa K. Support for Patients Who Have Difficulty Quitting Smoking: A Review. Intern Med. 2019; 58(3):317-320.

- Saad C, Cheng BH, Takamizawa R, Thakur A, Lee CW, Leung L, Veerman JL, Aminde LN. Effectiveness of tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship bans on smoking prevalence, initiation and cessation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tob Control 2025; tc-2024-058903.

- Siddiqi K, Elsey H, Khokhar MA, Marshall AM, Pokhrel S, Arora M, Crankson S, Mehra R, Morello P, Collin J, Fong GT. Framework Convention on Tobacco Control 2030-A Program to Accelerate the Implementation of World Health Organization Framework Convention for Tobacco Control in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2023; 25(6):1074-1081.

- Lahiri S, Bingenheimer JB, Evans WD, Wang Y, Cislaghi B, Dubey P, Snowden B. Understanding the mechanisms of change in social norms around tobacco use: A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions. Addiction 2025; 120(2):215-235.

- Tabeshpour J, Asadpour A, Norouz S, Hosseinzadeh H. The protective effects of medicinal plants against cigarette smoking: A comprehensive review. Phytomedicine 2024; 135:156199.

- Hsu CL, Wu YL, Tang GJ, Lee TS, Kou YR. Ginkgo biloba extract confers protection from cigarette smoke extract-induced apoptosis in human lung endothelial cells: Role of heme oxygenase-1. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2009; 22(4):286-96.

- Kennedy-Feitosa E, Okuro RT, Pinho Ribeiro V, Lanzetti M, Barroso MV, Zin WA, Porto LC, Brito-Gitirana L, Valenca SS. Eucalyptol attenuates cigarette smoke-induced acute lung inflammation and oxidative stress in the mouse. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2016; 41:11-18.

- Sasco AJ, Secretan MB, Straif K. Tobacco smoking and cancer: a brief review of recent epidemiological evidence. Lung Cancer 2004; 45 Suppl 2:S3-9.

- Sparrow D, Dawber TR. The influence of cigarette smoking on prognosis after a first myocardial infarction: a report from the Framingham Study. J Chronic Dis. 1978; 31:425-432.

- Shinton R, Beevers G. Meta-analysis of relation between cigarette smoking and stroke. BMJ 1989; 298:789-794.

- Ryu JH, Colby TV, Hartman TE, Vassallo R. Smoking-related interstitial lung diseases: a concise review. Eur Respir J. 2001; 17(1):122-32.

- Maddatu J, Anderson-Baucum E, Evans-Molina C. Smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes. Transl Res. 2017; 184:101-107.

- Laniado-Laborín, R. Smoking and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Parallel epidemics of the 21 century. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009; 6(1):209-24.

- Edderkaoui M, Thrower E. Smoking and Pancreatic Disease. J Cancer Ther. 2013; 4(10A):34-40.

- Roser M “Smoking: How large of a global problem is it? And how can we make progress against it?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. 2021.Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/smoking-big-problem-in-brief#' [Accessed on May 28, 2025].

- Phua ZJ, MacInnis RJ, Jayasekara H. Cigarette smoking and risk of second primary cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022; 78:102160.

- Inoue-Choi M, Hartge P, Liao LM, Caporaso N, Freedman ND. Association between long-term low-intensity cigarette smoking and incidence of smoking-related cancer in the national institutes of health-AARP cohort. Int J Cancer. 2018; 142(2):271-280.

- Khani, Y., Pourgholam-Amiji, N., Afshar, M., Otroshi, O., Sharifi-Esfahani, M., Sadeghi-Gandomani, H., Vejdani, M., & Salehiniya, H. Tobacco Smoking and Cancer Types: A Review. Biomedical Research and Therapy 2018; 5(4), 2142-2159.

- Shi H, Shao X, Hong Y. Association between cigarette smoking and the susceptibility of acute myeloid leukemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019; 23(22):10049-10057.

- Qi K, Cheng H, Jiang Y, Zheng Y. Contribution of smoking to the global burden of bladder cancer from 1990 to 2021 and projections to 2046. Tob Induc Dis. 2025; 23:10.18332/tid/202237.

- Wen Q, Wang X, Lv J, Guo Y, Pei P, Yang L, Chen Y, Du H, Burgess S, Hacker A, Liu F, Chen J, Yu C, Chen Z, Li L; China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group. Association between involuntary smoking and risk of cervical cancer in Chinese female never smokers: A prospective cohort study. Environ Res. 2022; 212(Pt C):113371.

- Bener A, Öztürk AE, Dasdelen MF, Barisik CC, Dasdelen ZB, Agan AF, De La Rosette J, Day AS. Colorectal cancer and associated genetic, lifestyle, cigarette, nargileh-hookah use and alcohol consumption risk factors: a comprehensive case-control study. Oncol Rev. 2024; 18:1449709.

- Islam MO, Thangaretnam K, Lu H, Peng D, Soutto M, El-Rifai W, Giordano S, Ban Y, Chen X, Bilbao D, Villarino AV, Schürer S, Hosein PJ, Chen Z. Smoking induces WEE1 expression to promote docetaxel resistance in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Mol Ther Oncolytics 2023; 30:286-300.

- Yang X, Chen H, Zhang J, Zhang S, Wu YS, Pang J. Association of cigarette use with risk of prostate cancer among US males: a cross-sectional study from NHANES 1999-2020. BMC Public Health 2025; 25(1):608.

- Campi R, Rebez G, Klatte T, Roussel E, Ouizad I, Ingels A, Pavan N, Kara O, Erdem S, Bertolo R, Capitanio U, Mir MC. Effect of smoking, hypertension and lifestyle factors on kidney cancer - perspectives for prevention and screening programmes. Nat Rev Urol. 2023; 20(11):669-681.

- Zuo JJ, Tao ZZ, Chen C, Hu ZW, Xu YX, Zheng AY, Guo Y. Characteristics of cigarette smoking without alcohol consumption and laryngeal cancer: overall and time-risk relation. A meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017; 274(3):1617-1631.

- Lee J, Choi JY, Lee SK. Heavy smoking increases early mortality risk in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after curative treatment. J Liver Cancer 2024; 24(2):253-262.

- Tang FH, Wong HYT, Tsang PSW, Yau M, Tam SY, Law L, Yau K, Wong J, Farah FHM, Wong J. Recent advancements in lung cancer research: a narrative review. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2025; 14(3):975-990.

- Pérez-Leal M, El Helou B, Roger I. Electronic Cigarettes Versus Combustible Cigarettes in Oral Squamous Cell Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. J Oral Pathol Med. 2025; 54(4):199-206.

- Subhan M, Saji Parel N, Krishna PV, Gupta A, Uthayaseelan K, Uthayaseelan K, Kadari M. Smoking and Pancreatic Cancer: Smoking Patterns, Tobacco Type, and Dose-Response Relationship. Cureus 2022; 14(6):e26009.

- Li LF, Chan RL, Lu L, Shen J, Zhang L, Wu WK, Wang L, Hu T, Li MX, Cho CH. Cigarette smoking and gastrointestinal diseases: the causal relationship and underlying molecular mechanisms (review). Int J Mol Med. 2014; 34(2):372-80.

- Warren GW, Cartmell KB, Garrett-Mayer E, Salloum RG, Cummings KM. Attributable Failure of First-line Cancer Treatment and Incremental Costs Associated With Smoking by Patients With Cancer. JAMA Netw Open 2019; 2(4):e191703.

- Petrucci CM, Hyland A. Understanding the Financial Consequences of Smoking During Cancer Treatment in the Era of Value-Based Medicine. JAMA Netw Open 2019; 2(4):e191713.

- Warren, GW. Mitigating the adverse health effects and costs associated with smoking after a cancer diagnosis. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2019; 8(Suppl 1):S59-S66.

- Isaranuwatchai W, de Oliveira C, Mittmann N, Evans WKB, Peter A, Truscott R, Chan KK. Impact of smoking on health system costs among cancer patients in a retrospective cohort study in Ontario, Canada. BMJ Open 2019; 9(6):e026022.

- Arrieta O, Quintana-Carrillo 2, Gabriel Ahumada-Curiel RH, Corona-Cruz JF, Correa-Acevedo E, Zinser-Sierra J, de la Mata-Moya D, Mohar-Betancourt A, Morales-Oyarvide V, Myriam Reynales-Shigematsu L. Medical care costs incurred by patients with smoking-related non-small cell lung cancer treated at the National Cancer Institute of Mexico. Tob Induc Dis. 2015; 12(1):25.

- Nguyen TXT, Han M, Oh JK. The economic burden of cancers attributable to smoking in Korea, 2014. Tob Induc Dis. 2019; 17:15.

- Lee J, Taneja V, Vassallo R. Cigarette smoking and inflammation: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Dent Res. 2012; 91:142-9.

- Wang H, Chen H, Fu Y, Liu M, Zhang J, Han S, Tian Y, Hou H, Hu Q. Effects of Smoking on Inflammatory-Related Cytokine Levels in Human Serum. Molecules 2022; 27(12):3715.

- Elisia I, Lam V, Cho B, Hay M, Li MY, Yeung M, Bu L, Jia W, Norton N, Lam S, Krystal G. The effect of smoking on chronic inflammation, immune function and blood cell composition. Sci Rep. 2020; 10(1):19480.

- Lugade AA, Bogner PN, Thatcher TH, Sime PJ, Phipps RP, Thanavala Y. Cigarette smoke exposure exacerbates lung inflammation and compromises immunity to bacterial infection. J Immunol. 2014; 192(11):5226-35.

- Anto RJ, Mukhopadhyay A, Shishodia S, Gairola CG, Aggarwal BB. Cigarette smoke condensate activates nuclear transcription factor-kappaB through phosphorylation and degradation of IkappaB(alpha): correlation with induction of cyclooxygenase-2. Carcinogenesis 2002; 23(9):1511-8.

- Kunnumakkara AB, Shabnam B, Girisa S, Harsha C, Banik K, Devi TB, Choudhury R, Sahu H, Parama D, Sailo BL, Thakur KK, Gupta SC, Aggarwal BB. Inflammation, NF-kappaB, and Chronic Diseases: How are They Linked? Crit Rev Immunol. 2020; 40(1):1-39.

- Doz E, Noulin N, Boichot E, Guénon I, Fick L, Le Bert M, Lagente V, Ryffel B, Schnyder B, Quesniaux VF, Couillin I. Cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary inflammation is TLR4/MyD88 and IL-1R1/MyD88 signaling dependent. J Immunol. 2008;180(2):1169-78.

- Karimi K, Sarir H, Mortaz E, Smit JJ, Hosseini H, De Kimpe SJ, Nijkamp FP, Folkerts G. Toll-like receptor-4 mediates cigarette smoke-induced cytokine production by human macrophages. Respir Res. 2006; 7(1):66.

- Sarir H, Mortaz E, Karimi K, Kraneveld AD, Rahman I, Caldenhoven E, Nijkamp FP, Folkerts G. Cigarette smoke regulates the expression of TLR4 and IL-8 production by human macrophages. J Inflamm (Lond). 2009; 6:12.

- Nadigel J, Préfontaine D, Baglole CJ, Maltais F, Bourbeau J, Eidelman DH, Hamid Q. Cigarette smoke increases TLR4 and TLR9 expression and induces cytokine production from CD8(+) T cells in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2011; 12(1):149.

- Pace E, Ferraro M, Siena L, Melis M, Montalbano AM, Johnson M, Bonsignore MR, Bonsignore G, Gjomarkaj M. Cigarette smoke increases Toll-like receptor 4 and modifies lipopolysaccharide-mediated responses in airway epithelial cells. Immunology 2008; 124(3):401-11.

- Yeh HY, Hung SH, Chen SC, Guo FR, Huang HL, Peng JK, Lee CS, Tsai JS. The Expression of Toll-Like Receptor 4 mRNA in PBMCs Is Upregulated in Smokers and Decreases Upon Smoking Cessation. Front Immunol. 2021; 12:667460.

- Hudlikar RR, Chou PJ, Kuo HD, Sargsyan D, Wu R, Kong AN. Long term exposure of cigarette smoke condensate (CSC) mediates transcriptomic changes in normal human lung epithelial Beas-2b cells and protection by garlic compounds. Food Chem Toxicol. 2023; 174:113656.

- Khan D, Zhou H, You J, Kaiser VA, Khajuria RK, Muhammad S. Tobacco smoke condensate-induced senescence in endothelial cells was ameliorated by colchicine treatment via suppression of NF-κB and MAPKs P38 and ERK pathways activation. Cell Commun Signal. 2024; 22(1):214.

- Thaiparambil J, Amara CS, Sen S, Putluri N, El-Zein R. Cigarette smoke condensate induces centrosome clustering in normal lung epithelial cells. Cancer Med. 2023; 12(7):8499-8509.

- Gellner CA, Reynaga DD, Leslie FM. Cigarette Smoke Extract: A Preclinical Model of Tobacco Dependence. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2016; 77:9.54.1-9.54.10.

- Hirata N, Horinouchi T, Kanda Y. Effects of cigarette smoke extract derived from heated tobacco products on the proliferation of lung cancer stem cells. Toxicol Rep. 2022; 9:1273-1280.

- Amel Al-Hashimi, Shah J, Carpenter R, Morgan W, Meah M, Ruchaya. PJ An In-Vitro Standardized Protocol for Preparing Smoke 1 Extract Media from Cigarette, Electronic Cigarette and 2 Waterpipe. bioRxiv 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kim Y-H, Kim M-S. Development and assessment of a novel standardized method for preparation of whole cigarette smoke condensate (WCSC) for toxicity testing of cigarette smoke. Microchemical Journal 2023; 191, 108914.

- Mathewson, HD. The Direct Preparation of Cigarette Smoke Condensate by High Velocity Impaction. Contributions to Tobacco & Nicotine Research 1966; 3, 430-437.

- Agraval H, Sharma JR, Yadav UCS. Method of Preparation of Cigarette Smoke Extract to Assess Lung Cancer-Associated Changes in Airway Epithelial Cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2022; 2413:121-132.

- Higashi T, Mai Y, Noya Y, Horinouchi T, Terada K, Hoshi A, Nepal P, Harada T, Horiguchi M, Hatate C, Kuge Y, Miwa S. A simple and rapid method for standard preparation of gas phase extract of cigarette smoke. PLoS One 2014; 9(9):e107856.

- Wright, C. Standardized methods for the regulation of cigarette-smoke constituents. Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2015; 66:118–127.

- Li, X. In vitro toxicity testing of cigarette smoke based on the air-liquid interface exposure: A review. Toxicol In Vitro 2016; 36:105-113.

- Singh AV, Maharjan RS, Kromer C, Laux P, Luch A, Vats T, Chandrasekar V, Dakua SP, Park BW. Advances in Smoking Related In Vitro Inhalation Toxicology: A Perspective Case of Challenges and Opportunities from Progresses in Lung-on-Chip Technologies. Chem Res Toxicol. 2021; 34(9):1984-2002.

- Horiyama S, Kunitomo M, Yoshikawa N, Nakamura K. Mass Spectrometric Approaches to the Identification of Potential Ingredients in Cigarette Smoke Causing Cytotoxicity. Biol Pharm Bull. 2016; 39(6):903-8.

- Fresenius RE. Analysis of tobacco smoke condensate. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 1985; 8: 561-575.

- Khattri RB, Thome T, Fitzgerald LF, Wohlgemuth SE, Hepple RT, Ryan TE. NMR Spectroscopy Identifies Chemicals in Cigarette Smoke Condensate That Impair Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Function. Toxics. 2022; 10(3):140.

- Liu G, Wang R, Chen H, Wu P, Fu Y, Li K, Liu M, Shi Z, Zhang Y, Su Y, Song L, Hou H, Hu Q. Non-nicotine constituents in cigarette smoke extract enhance nicotine addiction through monoamine oxidase A inhibition. Front Neurosci. 2022; 16:1058254.

- Park JM, Jeong H, Seo YS, Do VQ, Choi SJ, Lee K, Choi KC, Choi WJ, Lee MY. Cigarette Smoke Extract Produces Superoxide in Aqueous Media by Reacting with Bicarbonate. Toxics 2021; 9(11):316.

- Kim YH, An YJ, Jo S, Lee SH, Lee SJ, Choi SJ, Lee K. Comparison of volatile organic compounds between cigarette smoke condensate (CSC) and extract (CSE) samples. Environ Health Toxicol. 2018; 33(3):e2018012-0.

- Sun SC, Ley SC. New insights into NF-kappaB regulation and function. Trends Immunol. 2008; 29:469–478.

- Hacker H, Karin M. Regulation and function of IKK and IKK-related kinases. Sci STKE 2006;2006:re13.

- Chen FE, Huang DB, Chen YQ, Ghosh G. Crystal structure of p50/p65 heterodimer of transcription factor NF-kappaB bound to DNA. Nature 1998; 391:410–413.

- Hoffmann A, Natoli G, Ghosh G. Transcriptional regulation via the NF-kappaB signaling module. Oncogene. 2006; 25:6706–6716.

- Mathes E, O'Dea EL, Hoffmann A, Ghosh G. NF-kappaB dictates the degradation pathway of IkappaBalpha. EMBO J. 2008; 27(9):1357-67.

- Zhang C, Qin S, Qin L, Liu L, Sun W, Li X, Li N, Wu R, Wang X. Cigarette smoke extract-induced p120-mediated NF-κB activation in human epithelial cells is dependent on the RhoA/ROCK pathway. Sci Rep. 2016; 6:23131.

- Wang V, Heffer A, Roztocil E, Feldon SE, Libby RT, Woeller CF, Kuriyan AE. TNF-α and NF-κB signaling play a critical role in cigarette smoke-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition of retinal pigment epithelial cells in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. PLoS One 2022; 17(9):e0271950.

- Wang H, Yang T, Shen Y, Wan C, Li X, Li D, Liu Y, Wang T, Xu D, Wen F, Ying B. Ghrelin Inhibits Interleukin-6 Production Induced by Cigarette Smoke Extract in the Bronchial Epithelial Cell Via NF-κB Pathway. Inflammation 2016; 39(1):190-198.

- Wang D, Tao K, Xion J, Xu S, Jiang Y, Chen Q, He S. TAK-242 attenuates acute cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary inflammation in mouse via the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016; 472(3):508-15.

- Wang L, Meng J, Wang C, Wang Y, Yang C, Li Y. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates cigarette smoke-induced pyroptosis through the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2022; 49(5):56.

- Muresan XM, Cervellati F, Sticozzi C, Belmonte G, Chui CH, Lampronti I, Borgatti M, Gambari R, Valacchi G. The loss of cellular junctions in epithelial lung cells induced by cigarette smoke is attenuated by corilagin. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015; 2015:631758.

- Geraghty P, Dabo AJ, D'Armiento J. TLR4 protein contributes to cigarette smoke-induced matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) expression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Biol Chem. 2011; 286(34):30211-8.

- Zhang F, Geng Y, Shi X, Duo J. EGR3 deficiency alleviates cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary inflammation in COPD through TLR4/NF-κB/TIMP-1 axis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2025; 763:151741.

- Wang X, Smith C, Yin H. Targeting Toll-like receptors with small molecule agents. Chem Soc Rev. 2013; 42(12):4859-66.

- 97 Takashima K, Matsunaga N, Yoshimatsu M, Hazeki K, Kaisho T, Uekata M, Hazeki O, Akira S, Iizawa Y, Ii M. Analysis of binding site for the novel small-molecule TLR4 signal transduction inhibitor TAK-242 and its therapeutic effect on mouse sepsis model. Br J Pharmacol. 2009; 157(7):1250-62.

- Mio T, Romberger DJ, Thompson AB, Robbins RA, Heires A, Rennard SI. Cigarette smoke induces interleukin-8 release from human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997; 155(5):1770-6.

- Levänen B, Glader P, Dahlén B, Billing B, Qvarfordt I, Palmberg L, Larsson K, Lindén A. Impact of tobacco smoking on cytokine signaling via interleukin-17A in the peripheral airways. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016; 11:2109-2116.

- Guo JH, Thuong LHH, Jiang YJ, Huang CL, Huang YW, Cheng FJ, Liu PI, Liu CL, Huang WC, Tang CH. Cigarette smoke promotes IL-6-dependent lung cancer migration and osteolytic bone metastasis. Int J Biol Sci. 2024; 20(9):3257-3268.

- Reynolds PR, Cosio MG, Hoidal JR. Cigarette smoke-induced Egr-1 upregulates proinflammatory cytokines in pulmonary epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006; 35(3):314-9.

- Lee KH, Lee CH, Woo J, Jeong J, Jang AH, Yoo CG. Cigarette Smoke Extract Enhances IL-17A-Induced IL-8 Production via Up-Regulation of IL-17R in Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Mol Cells 2018; 41(4):282-289.

- Yang SR, Chida AS, Bauter MR, Shafiq N, Seweryniak K, Maggirwar SB, Kilty I, Rahman I. Cigarette smoke induces proinflammatory cytokine release by activation of NF-kappaB and posttranslational modifications of histone deacetylase in macrophages. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006; 291(1):L46-57.

- Oltmanns U, Chung KF, Walters M, John M, Mitchell JA. Cigarette smoke induces IL-8, but inhibits eotaxin and RANTES release from airway smooth muscle. Respir Res. 2005; 6(1):74.

- Ramage L, Jones AC, Whelan CJ. Induction of apoptosis with tobacco smoke and related products in A549 lung epithelial cells in vitro. J Inflamm (Lond). 2006;3:3.

- Jiao ZX, Ao QL, Xiong M. Cigarette smoke extract inhibits the proliferation of alveolar epithelial cells and induces apoptosis. Sheng Li Xue Bao. 2006; 58(3):244-54.

- Wang J, Wilcken DE, Wang XL. Cigarette smoke activates caspase-3 to induce apoptosis of human umbilical venous endothelial cells. Mol Genet Metab. 2001; 72(1):82-8.

- Messner B, Frotschnig S, Steinacher-Nigisch A, Winter B, Eichmair E, Gebetsberger J, Schwaiger S, Ploner C, Laufer G, Bernhard D. Apoptosis and necrosis: two different outcomes of cigarette smoke condensate-induced endothelial cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2012; 3(11):e424.

- Feng H, Li M, Altawil A, Yin Y, Zheng R, Kang J. Cigarette smoke extracts induce apoptosis in Raw264.7 cells via endoplasmic reticulum stress and the intracellular Ca2+/P38/STAT1 pathway. Toxicol In Vitro 2021; 77:105249.

- Banerjee S, Maity P, Mukherjee S, Sil AK, Panda K, Chattopadhyay D, Chatterjee IB. Black tea prevents cigarette smoke-induced apoptosis and lung damage. J Inflamm (Lond) 2007; 4:3.

- Lin X-X, Yang X-F, Jiang J-X, Zhang S-J, Guan Y, Liu Y-N, Sun Y-H, Xie Q-M. Cigarette smoke extract- induced BEAS-2B cell apoptosis and anti-oxidative Nrf-2 up-regulation are mediated by ROS-stimulated p38 activation. Toxicol Mech Methods 2014; 24:575–583.

- Seo YS, Park JM, Kim JH, Lee MY. Cigarette Smoke-Induced Reactive Oxygen Species Formation: A Concise Review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023; 12(9):1732.

- Lyons M.J., Gibson J.F., Ingram D.J. Free-radicals produced in cigarette smoke. Nature 1958; 181:1003–1004.

- Shein, M., Jeschke G. Comparison of free radical levels in the aerosol from conventional cigarettes, electronic cigarettes, and heat-not-burn tobacco products. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2019; 32:1289–1298.

- Bartalis, J., Chan W.G., Wooten J.B. A new look at radicals in cigarette smoke. Anal. Chem. 2007; 79:5103–5106.

- 116, Mitra A., Mandal A.K. Conjugation of para-benzoquinone of cigarette smoke with human hemoglobin leads to unstable tetramer and reduced cooperative oxygen binding. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2018; 29:2048–2058.

- Ghosh, A., Choudhury A., Das A., Chatterjee N.S., Das T., Chowdhury R., Panda K., Banerjee R., Chatterjee I.B. Cigarette smoke induces p-benzoquinone-albumin adduct in blood serum: Implications on structure and ligand binding properties. Toxicology 2012; 292:78–89.

- Chang, K.H., Park J.M., Lee C.H., Kim B., Choi K.C., Choi S.J., Lee K., Lee M.Y. NADPH oxidase (NOX) 1 mediates cigarette smoke-induced superoxide generation in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Toxicol. In Vitro 2017; 38:49–58.

- Yildiz, L., Kayaoglu N., Aksoy H. The changes of superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase activities in erythrocytes of active and passive smokers. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2002; 40:612–615.

- Kondo, T., Tagami S., Yoshioka A., Nishimura M., Kawakami Y. Current smoking of elderly men reduces antioxidants in alveolar macrophages. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1994; 149:178–182.

- Oriola AO, Oyedeji AO. Plant-Derived Natural Products as Lead Agents against Common Respiratory Diseases. Molecules 2022; 27(10):3054.

- Li D, Hu J, Wang T, Zhang X, Liu L, Wang H, Wu Y, Xu D, Wen F. Silymarin attenuates cigarette smoke extract-induced inflammation via simultaneous inhibition of autophagy and ERK/p38 MAPK pathway in human bronchial epithelial cells. Sci Rep. 2016; 6:37751.

- Li D, Xu D, Wang T, Shen Y, Guo S, Zhang X, Guo L, Li X, Liu L, Wen F. Silymarin attenuates airway inflammation induced by cigarette smoke in mice. Inflammation 2015; 38(2):871-8.

- Hoch CC, Petry J, Griesbaum L, Weiser T, Werner K, Ploch M, Verschoor A, Multhoff G, Bashiri Dezfouli A, Wollenberg B. 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol): A versatile phytochemical with therapeutic applications across multiple diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023; 167:115467.

- Seol GH, Kim KY. Eucalyptol and Its Role in Chronic Diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016; 929:389-398.

- Reis R, Orak D, Yilmaz D, Cimen H, Sipahi H. Modulation of cigarette smoke extract-induced human bronchial epithelial damage by eucalyptol and curcumin. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2021; 40(9):1445-1462.

- Yu N, Sun YT, Su XM, He M, Dai B, Kang J. Treatment with eucalyptol mitigates cigarette smoke-induced lung injury through suppressing ICAM-1 gene expression. Biosci Rep 2018; 38(4): BSR20171636.

- Kennedy-Feitosa E, Cattani-Cavalieri I, Barroso MV, et al. Eucalyptol promotes lung repair in mice following cigarette smoke-induced emphysema. Phytomedicine 2019; 55: 70–79.

- Hewlings SJ, Kalman DS. Curcumin: A Review of Its Effects on Human Health. Foods 2017; 6(10):92.

- Nelson KM, Dahlin JL, Bisson J, Graham J, Pauli GF, Walters MA. The Essential Medicinal Chemistry of Curcumin. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2017; 60 (5): 1620–1637.

- Fanoudi S, Alavi MS, Mehri S, Hosseinzadeh H. The protective effects of curcumin against cigarette smoke-induced toxicity: A comprehensive review. Phytother Res. 2024; 38(1):98-116.

- Kokkinis S, De Rubis G, Paudel KR, Patel VK, Yeung S, Jessamine V, MacLoughlin R, Hansbro PM, Oliver B, Dua K. Liposomal curcumin inhibits cigarette smoke induced senescence and inflammation in human bronchial epithelial cells. Pathol Res Pract. 2024; 260:155423.

- Patel VK, Kokkinis S, De Rubis G, Hansbro PM, Paudel KR, Dua K. Curcumin liposomes attenuate the expression of cigarette smoke extract-induced inflammatory markers IL-8 and IL-24 in vitro. EXCLI J. 2024; 23:904-907.

- Li Q, Sun J, Mohammadtursun N, Wu J, Dong J, Li L. Curcumin inhibits cigarette smoke-induced inflammation via modulating the PPARγ-NF-κB signaling pathway. Food Funct. 2019; 10(12):7983-7994.

- Ames T., R., Beton J. L., Bowers A., Halsall T. G., Jones E. (1954). The chemistry of the triterpenes and related compounds Part XXIII the structure of taraxasterol ψ-taraxasterol (heterolupeol) and lupenol-I. J. Chem. Soc. 1954; 25: 307–318.

- Jiao F, Tan Z, Yu Z, Zhou B, Meng L, Shi X. The phytochemical and pharmacological profile of taraxasterol. Front Pharmacol. 2022; 13:927365.

- Xueshibojie L, Duo Y, Tiejun W. Taraxasterol inhibits cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation by inhibiting reactive oxygen species-induced TLR4 trafficking to lipid rafts. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016; 789:301-307.

- Yagishita Y, Fahey JW, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Kensler TW. Broccoli or Sulforaphane: Is It the Source or Dose That Matters? Molecules. 2019; 24:3593.

- Baralić K, Živanović J, Marić Đ, Bozic D, Grahovac L, Antonijević Miljaković E, Ćurčić M, Buha Djordjevic A, Bulat Z, Antonijević B, Đukić-Ćosić D. Sulforaphane-A Compound with Potential Health Benefits for Disease Prevention and Treatment: Insights from Pharmacological and Toxicological Experimental Studies. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024; 13(2):147.

- Song H, Wang YH, Zhou HY, Cui KM. Sulforaphane alleviates LPS-induced inflammatory injury in ARPE-19 cells by repressing the PWRN2/NF-kB pathway. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2022; 44(6):868-876.

- Gasparello J, Marzaro G, Papi C, Gentili V, Rizzo R, Zurlo M, Scapoli C, Finotti A, Gambari R. Effects of Sulforaphane on SARS-CoV-2 infection and NF-kappaB dependent expression of genes involved in the COVID-19 'cytokine storm'. Int J Mol Med. 2023; 52(3):76.

- Starrett W, Blake DJ. Sulforaphane inhibits de novo synthesis of IL-8 and MCP-1 in human epithelial cells generated by cigarette smoke extract. J Immunotoxicol. 2011; 8(2):150-8.

- Jiao Z, Chang J, Li J, Nie D, Cui H, Guo D. Sulforaphane increases Nrf2 expression and protects alveolar epithelial cells against injury caused by cigarette smoke extract. Mol Med Rep. 2017; 16(2):1241-1247.

- Jiao Z, Zhang Q, Chang J, Nie D, Li M, Zhu Y, Wang C, Wang Y, Liu F. A protective role of sulforaphane on alveolar epithelial cells exposed to cigarette smoke extract. Exp Lung Res. 2013; 39(9):379-86.

- Hau DK, Gambari R, Wong RS, Yuen MC, Cheng GY, Tong CS, Zhu GY, Leung AK, Lai PB, Lau FY, Chan AK, Wong WY, Kok SH, Cheng CH, Kan CW, Chan AS, Chui CH, Tang JC, Fong DW. Phyllanthus urinaria extract attenuates acetaminophen induced hepatotoxicity: involvement of cytochrome P450 CYP2E1. Phytomedicine 2009; 16(8):751-60.

- Sudjaroen Y, Hull WE, Erben G, Würtele G, Changbumrung S, Ulrich CM, Owen RW. Isolation and characterization of ellagitannins as the major polyphenolic components of Longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour) seeds. Phytochemistry 2012; 77:226–237.

- Okabe S, Suganuma M, Imayoshi Y, Taniguchi S, Yoshida T, Fujiki H. New TNF-α releasing inhibitors, geraniin and corilagin, in leaves of acer nikoense, megusurino-ki. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2001; 24(10):1145–1148.

- Zhao L, Zhang SL, Tao JY, Pang R, Jin F, Guo YJ, Dong JH, Ye P, Zhao HY, Zheng GH. Preliminary exploration on anti-inflammatory mechanism of Corilagin (beta-1-O-galloyl-3,6-(R)-hexahydroxydiphenoyl-d-glucose) in vitro. International Immunopharmacology 2008; 8(7):1059–1064.

- Kinoshita S, Inoue Y, Nakama S, Ichiba T, Aniya Y. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective actions of medicinal herb, Terminalia catappa L. from Okinawa Island and its tannin corilagin. Phytomedicine 2007; 14(11):755–762.

- Luo T, Zhou X, Qin M, Lin Y, Lin J, Chen G, Liu A, Ouyang D, Chen D, Pan H. Corilagin Restrains NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Pyroptosis through the ROS/TXNIP/NLRP3 Pathway to Prevent Inflammation. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022; 2022:1652244.

- Fan GJ, Liu XD, Qian YP, Shang YJ, Li XZ, Dai F, Fang JG, Jin XL, Zhou B. 4,4'-Dihydroxy-trans-stilbene, a resveratrol analogue, exhibited enhanced antioxidant activity and cytotoxicity. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009; 17(6):2360-5.

- Wang T, Dai F, Li GH, Chen XM, Li YR, Wang SQ, Ren DM, Wang XN, Lou HX, Zhou B, Shen T. Trans-4,4'-dihydroxystilbene ameliorates cigarette smoke-induced progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease via inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammatory response. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020; 152:525-539.

- Fakhria, A. Al-Joufi, Saira Shaukat, Liaqat Hussain, Kashif ur Rehman Khan, Nadia Hussain, Amal H.I. Al Haddad, Ali Alqahtani, Taha Alqahtani, Maha Abdullah Momenah, Salam A. Ibrahim, Musaddique Hussain. Lavandula stoechas significantly alleviates cigarette smoke-induced acute lung injury via modulation of oxidative stress and the NF-κB pathway. Food Bioscience 2024; 59,103834.

- Hussain N, Ikram N, Khan KUR, Hussain L, Alqahtani AM, Alqahtani T, Hussain M, Suliman M, Alshahrani MY, Sitohy B. Cichorium intybus L. significantly alleviates cigarette smoke-induced acute lung injury by lowering NF-κB pathway activation and inflammatory mediators. Heliyon 2023; 9(11):e22055.

- Zeng LH, Fatima M, Syed SK, Shaukat S, Mahdy A, Hussain N, Al Haddad AHI, Said ASA, Alqahtani A, Alqahtani T, Majeed A, Tariq M, Hussain M. Anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties of Ipomoea nil (Linn.) Roth significantly alleviates cigarette smoke (CS)-induced acute lung injury via possibly inhibiting the NF-κB pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022; 155:113267.

- Barroso MV, Cattani-Cavalieri I, de Brito-Gitirana L, Fautrel A, Lagente V, Schmidt M, Porto LC, Romana-Souza B, Valenca SS, Lanzetti M. Propolis reversed cigarette smoke-induced emphysema through macrophage alternative activation independent of Nrf2. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017; 25: 5557-5568.

- Lanzetti M, Lopes AA, Ferreira TS, de Moura RS, Resende AC, Porto LC, Valenca SS. Mate tea ameliorates emphysema in cigarette smoke-exposed mice. Exp. Lung Res. 2011; 37: 246-257.

- Pires KM, Valenca SS, Resende AC, Porto LC, Queiroz EF, Moreira DD, de Moura RS. Grape skin extract reduced pulmonary oxidative response in mice exposed to cigarette smoke. Med. Sci. Monit. 2011; BR187-BR195.

- Imai J, Ide N, Nagae S, Moriguchi T, Matsuura H, Itakura Y. Antioxidant and radical scavenging effects of aged garlic extract and its constituents. Planta Medica 1994; 60:417–420.

- Serrano JCE, Castro-Boqué E, García-Carrasco A, Morán-Valero MI, González-Hedström D, Bermúdez-López M, Valdivielso JM, Espinel AE, Portero-Otín M. Antihypertensive Effects of an Optimized Aged Garlic Extract in Subjects with Grade I Hypertension and Antihypertensive Drug Therapy: A Randomized, Triple-Blind Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2023; 15:3691.

- Ohkubo S, Dalla Via L, Grancara S, Kanamori Y, García-Argáez AN, Canettieri G, Arcari P, Toninello A, Agostinelli E. The antioxidant, aged garlic extract, exerts cytotoxic effects on wild-type and multidrug-resistant human cancer cells by altering mitochondrial permeability. Int. J. Oncol. 2018; 53:1257–1268.

- Liu X, Wang N, He Z, Chen C, Ma J, Liu X, Deng S, Xie L. Diallyl trisulfide inhibits osteosarcoma 143B cell migration, invasion and EMT by inducing autophagy. Heliyon 2024;10:e26681.

- Ferguson DT, Taka E, Messeha S, Flores-Rozas H, Reed SL, Redmond BV, Soliman KFA, Kanga KJW, Darling-Reed SF. The Garlic Compound, Diallyl Trisulfide, Attenuates Benzo[a]Pyrene-Induced Precancerous Effect through Its Antioxidant Effect, AhR Inhibition, and Increased DNA Repair in Human Breast Epithelial Cells. Nutrients 2024; 16:300.

- Bentke-Imiolek A, Szlęzak D, Zarzycka M, Wróbel M, Bronowicka-Adamska P. S-Allyl-L-Cysteine Affects Cell Proliferation and Expression of H2S-Synthetizing Enzymes in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 Adenocarcinoma Cell Lines. Biomolecules 2024; 14:188.

- Kanamori Y, Via LD, Macone A, Canettieri G, Greco A, Toninello A, Agostinelli E. Aged garlic extract and its constituent, S-allyl-L-cysteine, induce the apoptosis of neuroblastoma cancer cells due to mitochondrial membrane depolarization. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020; 19:1511–1521.

- Kodera Y, Kurita M, Nakamoto M, Matsutomo T. Chemistry of aged garlic: Diversity of constituents in aged garlic extract and their production mechanisms via the combination of chemical and enzymatic reactions. Exp Ther Med. 2020 Feb;19(2):1574-1584.

- Borek, C. Antioxidant health effects of aged garlic extract. J Nutr. 2001 Mar;131(3s):1010S-5S. [CrossRef]

- Ryu K, Rosen RT. Unique Chemistry of Aged Garlic Extract. Oriental Foods and Herbs, 2003; 19, 258-270.

- El-Saadony MT, Saad AM, Korma SA, Salem HM, Abd El-Mageed TA, Alkafaas SS, Elsalahaty MI, Elkafas SS, Mosa WFA, Ahmed AE, Mathew BT, Albastaki NA, Alkuwaiti AA, El-Tarabily MK, AbuQamar SF, El-Tarabily KA and Ibrahim SA. Garlic bioactive substances and their therapeutic applications for improving human health: a comprehensive review. Front. Immunol. 2024; 15:1277074. [CrossRef]

- Nagae S, Ushijima M, Hatono S, Imai J, Kasuga S, Matsuura H, Itakura Y, Higashi Y. Pharmacokinetics of the garlic compound S-allylcysteine. Planta Med. 1994; 60(3):214-7.

- Agostinelli E, Marzaro G, Gambari R, Finotti A. Potential applications of components of Aged Garlic Extract (AGE) in mitigating pro-inflammatory gene expression linked to human diseases. Exp Ther Med. 2025; 30(1):134.

- Gasparello J, Papi C, Marzaro G, Macone A, Zurlo M, Finotti A, Agostinelli E, Gambari R. Aged Garlic Extract (AGE) and Its Constituent S-Allyl-Cysteine (SAC) Inhibit the Expression of Pro-Inflammatory Genes Induced in Bronchial Epithelial IB3-1 Cells by Exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and the BNT162b2 Vaccine. Molecules 2024; 29(24):5938.

- Papi C, Gasparello J, Marzaro G, Macone A, Zurlo M, Di Padua F, Fino P, Agostinelli E, Gambari R, Finotti A, Finotti A, et al: Aged garlic extract major constituent S-1-propenyl-l-cysteine inhibits proinflammatory mRNA expression in bronchial epithelial IB3-1 cells exposed to the BNT162b2 vaccine. Exp Ther Med. 2025; 30: 153.

- Elmazoglu Z, Aydın Bek Z, Sarıbaş SG, Özoğul C, Goker B, Bitik B, Aktekin CN, Karasu Ç. S-allylcysteine inhibits chondrocyte inflammation to reduce human osteoarthritis via targeting RAGE, TLR4, JNK, and Nrf2 signaling: comparison with colchicine. Biochem Cell Biol. 2021; 99(5):645-654.

- Geng Z, Rong Y, Lau BH. S-allyl cysteine inhibits activation of nuclear factor kappa B in human T cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997; 23(2):345-50.

- Huang XP, Shi ZH, Ming GF, Xu DM, Cheng SQ.S-Allyl-L-cysteine (SAC) inhibits copper-induced apoptosis and cuproptosis to alleviate cardiomyocyte injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2024; 730:150341.

- Chen P, Hu M, Liu F, Yu H, Chen C. S-allyl-l-cysteine (SAC) protects hepatocytes from alcohol-induced apoptosis. FEBS Open Bio. 2019; 9(7):1327-1336.

- Kalayarasan S, Sriram N, Sureshkumar A, Sudhandiran G. Chromium (VI)-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis is reduced by garlic and its derivative S-allylcysteine through the activation of Nrf2 in the hepatocytes of Wistar rats. J Appl Toxicol. 2008; 28(7):908-19.

- Orozco-Ibarra M, Muñoz-Sánchez J, Zavala-Medina ME, Pineda B, Magaña-Maldonado R, Vázquez-Contreras E, Maldonado PD, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Chánez-Cárdenas ME. Aged garlic extract and S-allylcysteine prevent apoptotic cell death in a chemical hypoxia model. Biol Res. 2016; 49:7.

- Reddy, VP. Oxidative Stress in Health and Disease. Biomedicine 2023; 11(11):2925.

- Liu Z, Ren Z, Zhang J, Chuang CC, Kandaswamy E, Zhou T, Zuo L. Role of ROS and Nutritional Antioxidants in Human Diseases. Front Physiol. 2018; 9:477.

- Gupta P, Dutt V, Kaur N, Kalra P, Gupta S, Dua A, Dabur R, Saini V, Mittal A. S-allyl cysteine: A potential compound against skeletal muscle atrophy. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2020; 1864(10):129676.

- He Y, Xiao L, Zhang J, Zhu Y, Guo Y, Xia Y, Zhao H, Wei Z, Dai Y. Diallyl trisulfide alleviates dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis in mice by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation via ROS/Trx-1 pathway. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2024; 135(5):593-606.

- Wang Y, Wang HL, Xing GD, Qian Y, Zhong JF, Chen KL. S-allyl cysteine ameliorates heat stress-induced oxidative stress by activating Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway in BMECs. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2021; 416:115469.

- Ruiz-Sánchez E, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Medina-Campos ON, Maldonado PD, Rojas P. S-allyl Cysteine, a Garlic Compound, Produces an Antidepressant-Like Effect and Exhibits Antioxidant Properties in Mice. Brain Sci. 2020; 10(9):592.

- Xu C, Mathews AE, Rodrigues C, Eudy BJ, Rowe CA, O'Donoughue A, Percival SS. Aged garlic extract supplementation modifies inflammation and immunity of adults with obesity: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018; 24:148-155.

- Budoff MJ, Ahmadi N, Gul KM, Liu ST, Flores FR, Tiano J, Takasu J, Miller E, Tsimikas S. Aged garlic extract supplemented with B vitamins, folic acid and L-arginine retards the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis: a randomized clinical trial. Prev Med. 2009; 49(2-3):101-7.

- Wlosinska M, Nilsson AC, Hlebowicz J, Fakhro M, Malmsjö M, Lindstedt S. Aged Garlic Extract Reduces IL-6: A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial in Females with a Low Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021; 2021:6636875.

- Gambari R, Papi C, Gasparello J, Agostinelli E, Finotti A. Preliminary results and a theoretical perspective of co-treatment using a miR-93-5p mimic and aged garlic extract to inhibit the expression of the pro-inflammatory interleukin-8 gene. Exp Ther Med. 2025; 29(4):85.

- Onwuzo CN, Olukorode J, Sange W, Orimoloye DA, Udojike C, Omoragbon L, Hassan AE, Falade DM, Omiko R, Odunaike OS, Adams-Momoh PA, Addeh E, Onwuzo S, Joseph-Erameh U. A Review of Smoking Cessation Interventions: Efficacy, Strategies for Implementation, and Future Directions. Cureus 2024; 16(1):e52102.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).